Abstract

Referrals of hospitalized people with opioid use disorder (OUD) to post-acute medical care facilities are commonly rejected. We linked all electronic referrals from a Boston safety-net hospital in 2018 with clinical data and used multivariable logistic regression to examine the association between OUD diagnosis and rejection from post-acute medical care. Compared to those without OUD, people with OUD were referred to more facilities [8.2 vs. 6.6 per hospitalization], were rejected a greater proportion of the time (83.3% vs. 65.5%), and in adjusted analyses, had greater odds of rejection from post-acute care [AOR 2.17, 95%CI 1.71, 2.76]. Additionally, people with OUD were referred disproportionately to a small subset of facilities with higher likelihood of acceptance. Our findings document widespread discrimination against people with OUD in post-acute care admissions. Efforts to ensure equitable access to medically necessary post-acute medical care for people with OUD are needed.

Keywords: Opioid use disorder, medications for opioid use disorder, post-acute medical care, discrimination, skilled nursing facilities

Introduction

Hospitalizations for individuals with opioid use disorder (OUD) in the U.S. rapidly increased from 164 to 296 per 100,000 persons between 2006 and 2016.1 The increase in hospitalizations was the result of complications of opioid use, including systemic infections from drug injection, overdoses, physical and psychological traumas, strokes, or other acute conditions such as pneumonia and chronic obstructive lung disease.2–6 Individuals with OUD commonly require prolonged intravenous antibiotics, wound care, medication titration, and physical or occupational therapy after stabilization from an acute hospitalization. For many individuals these services can only be delivered in post-acute medical care facilities (e.g., medical rehabilitation or skilled nursing settings).

Massachusetts has the second highest rate of opioid-related hospitalizations in the country, making discharge planning and post-acute care access for patients with OUD an especially important issue in the state as these individuals tend to have longer hospitalizations than patients without OUD with the same conditions.7,8 In 2016, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health issued guidance to all Massachusetts licensed facilities that people with OUD should not be excluded from admission to post-acute medical care due to treatment with medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) such as methadone or buprenorphine.9 Despite this, the Massachusetts United States Attorney’s office has reached several settlements with post-acute medical care facilities for violating the Americans with Disability Act (ADA) by screening out individuals with OUD or those treated with MOUD.10,11 Several clinicians have described the challenge of finding post-acute care for people with OUD, but few studies have systematically evaluated post-acute care referral and admissions practices.12,13 Previous work has shown that facilities explicitly reject referrals due to substance use or MOUD, in violation of state and federal policies.14 However, it is not known if people with OUD are more likely to be rejected from post-acute care facilities when compared to those without OUD or if they experience distinct post-acute care referral patterns.

In this study, we used data from Boston Medical Center’s (BMC) electronic post-acute care referral system to examine the association between OUD diagnosis and referrals to and rejection by post-acute medical care facilities. We hypothesized that referrals for individuals with OUD would be more likely to be rejected than referrals for individuals without OUD and that individuals with OUD would be preferentially referred to a subset of post-acute care facilities with higher likelihood of accepting individuals with OUD, masking disparities in observed rejection rates. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a stratified analysis of acceptance rate by likelihood of facility to receive an OUD referral.

Methods

Study design and data source

In this retrospective cohort study of hospitalized patients with and without OUD diagnoses, we examined all electronic referrals to private post-acute care facilities and the outcomes of these referrals (i.e., rejected or accepted) from hospitalizations at BMC, a safety-net hospital in Boston, Massachusetts in 2018. During the study period, referrals to private post-acute care facilities from BMC were placed using the Allscripts electronic referral system. We used medical record numbers to link the Allscripts referral data to the corresponding hospitalizations using the BMC Clinical Data Warehouse (CDW), which provides clinical, demographic, and insurance data from the electronic medical record and has been used in previous studies on BMC addiction services.14,15 Referrals to Massachusetts Department of Public Health-funded post-acute care facilities or to respite facilities for individuals experiencing homelessness were not included, as these referrals occurred outside of the electronic referral system. Though these referrals were unavailable, disposition data included discharge to these facilities.

Cohort selection

We included all individuals 18 or older hospitalized at BMC who received an electronic referral in the Allscripts electronic referral system to one or more included private post-acute medical care facilities in 2018. Patients who were medically appropriate for discharge directly to home and those whose discharges were self-directed prior to discharge planning would not be included in this study. To decrease heterogeneity among referred individuals and facilities in the study cohort, we included referrals to skilled nursing or subacute nursing facilities only. We excluded referrals to other acute care hospitals, acute rehabilitation facilities, long-term acute care facilities, and rest homes as differences in the clinical needs of patients referred to these facilities or in facilities’ admission criteria could confound the relationship between OUD status and admission decisions, this study’s focus. We use the general term post-acute care facilities to refer to the facilities in our cohort. To ensure adequate data to observe variation in admissions decisions, we included only referrals to facilities that received at least five total referrals and at least one referral for an individual with OUD. The Boston University Medical Campus Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Variables of interest

The primary outcome was post-acute care referral rejection as transmitted in the electronic referral system. We used data from the CDW to extract several individual characteristics from the hospitalization associated with the referral. Our primary exposure was OUD status, defined by the presence of International Classification of Disease, 10 Edition (ICD-10) codes for opioid use, abuse or dependence (F11.10, F11.11, F11.21, F11.221, F11.23, F11.90) or receipt of buprenorphine or methadone during the hospitalization or at time of discharge. Methadone was used to designate OUD-status only if it was administered in liquid form to prevent misclassification of individuals receiving methadone in pill form for chronic pain. Naltrexone was not used to designate OUD status as it is more commonly used to treat alcohol use disorder during an acute hospitalization. Other covariates ascertained from the CDW included age, gender, race, ethnicity, language, insurance, homelessness status, receipt of psychiatric or addiction consult, clinical diagnoses including alcohol use disorder, severity of illness as determined by the Charlson Comorbidity Index16, and contact precaution status. To describe the cohort, we categorized the primary admission diagnosis into system-based categories using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical Classifications Software.17

Additionally, we categorized post-acute care facilities based on the proportion of referrals received that were for individuals with OUD, reviewing the distribution of these OUD referral proportions across the facilities to define high, medium, and low OUD referral facility groups. We defined the medium OUD referral facility group by the mean proportion of OUD referrals in the full sample plus or minus 5%. We defined facilities receiving more than the mean plus 5% as high OUD referral facilities and those receiving less than the mean minus 5% as low OUD referral facilities.

For descriptive purposes, we examined facility characteristics by facility OUD referral category. We used data from the Brown University School of Public Health and National Institute on Aging (1P01AG027296) LTCFocus database18 and included the following facility variables from 2017 LTCFocus data, the most recent year available: acuity index (measure of residents’ need for assistance with activities of daily living), resource utilization index (measure of staff time needed to care for residents), average patient age, proportions of residents under age 65, who were female, by race, with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, and with daily pain. We also included number of beds, occupancy rate, whether the facility is part of a multi-facility chain, proportion of residents with Medicaid or Medicare insurance, nurse practitioner or physician assistant on staff, for-profit status, and number of direct care hours per resident per day. We also included 2018 Star ratings from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid which categorizes facilities on a 1 to 5 scale, where 5 is defined as much better than average. The rating system includes data on health inspection, staffing, and quality measures and is designed to help consumers compare nursing homes.19

Statistical analyses

We compared referral characteristics among hospitalizations for individuals with OUD and without OUD using Fisher’s exact or Chi Squared testing based on sample size. We compared facility characteristics between low, medium, and high OUD-referral hospitalizations using the Kruskall-Wallis tests for continuous variables and Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Facilities with missing data from LTCFocus were excluded from OUD referral category comparisons. We used multivariable logistic regression to estimate the association between OUD status and referral rejection. To control for potential confounding variables, we included in our model all descriptive variables for referrals previously noted except for addiction consult status because it was highly correlated with our primary exposure, OUD status. Based on our a priori hypothesis, we further examined the interaction between OUD and facility OUD-referral category (high, medium, low). We adjusted for clustering at the individual level in all models. Analyses were performed in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary NC).

Limitations

Results from this study must be interpreted in the context of its limitations. First, these data are from a safety-net hospital in Massachusetts in 2018 and may not be generalizable to other locations or times (e.g., differences in insurance coverage, access to inpatient or ambulatory OUD care, or scrutiny of OUD post-acute care admissions). Second, though our analytic approach includes facility categories based on proportion of referrals associated with an OUD diagnosis, we cannot fully account for decisions made by case managers or patients about which facilities receive referrals. Though we adjust for clustering at the individual level in our models, some individuals may request facilities in specific geographic areas or have had prior experience with specific facilities that could impact patient or facility referral selection in ways we cannot observe in our data. Third, our study is subject to exposure misclassification, as we determined OUD status at the hospitalization level using diagnosis codes and receipt of medications for OUD rather than through chart review. Given high rates of MOUD receipt in the OUD cohort, we are not able to differentiate between rejections due to OUD or MOUD. Nor are we able to classify the severity or current status of an individual’s OUD. Fourth, we are only able to report referrals to private facilities. Referrals to two state-run facilities and a respite facility for people experiencing homelessness — which in our clinical experience have been more open to accepting patients with OUD — are not processed through the online referral system we used to gather data, resulting in a selected sample of individuals with OUD which may bias our findings toward the null hypothesis. Notably, the data does include ultimate disposition type (i.e., home, facility, “against medical advice” discharge), but facility discharge includes both private and public facilities and the data does not allow us to differentiate between them. Further, some individuals with OUD may receive referrals to these specific facilities only and would not be included in our data and thus we are not able to examine characteristics such as racial and ethnic inequities in referral patterns between private and public facilities.

Results

We identified 2,523 hospitalizations resulting in 18,584 referrals to 686 private post-acute care facilities in the electronic referral system. After excluding facilities that only received referrals for acute care, acute rehabilitation, long-term acute care, or rest home services (42) and those that received fewer than 5 total referrals (286) or 1 OUD referral (114), the final study cohort included 2,463 hospitalizations of patients who were referred 16,403 times to 244 post-acute care facilities (i.e., skilled nursing facilities or subacute care facilities) (Appendix Exhibit A1).20

Of individuals identified with OUD, the majority (144 of 166) received MOUD—86 received methadone, 47 buprenorphine, and 11 both methadone and buprenorphine. Compared to hospitalized individuals without OUD (2297, 93%), those with OUD (166, 6.7%) were significantly (p≤0.005) younger [mean age 51.7 vs 69.1], more likely to be male (69% vs. 49%), White (47% vs. 36%) or Hispanic (17% vs. 11%), English speakers (92% vs 79%), and insured by Medicaid (55.4% vs 20.9%) rather than Medicare (22.8% vs. 53.6%) or private insurance (9.0% vs. 9.5%) (Exhibit 1). Additionally, individuals with OUD-hospitalizations were significantly more likely to experience homelessness (42.2% vs 10.3%), to receive an inpatient psychiatry (27.1% vs 18.2%) or addiction consult (66.3% vs 4.6%), and to require contact precautions during the hospitalization (49.4% vs 24.6%). There were no significant differences in the distribution of the Charlson Co-morbidity Indices, but individuals with OUD were more likely to have an infectious diagnosis (20% vs 10%) (Appendix Exhibit A2).20

Exhibit 1:

Characteristics of hospitalizations among individuals with and without opioid use disorder referred to post-acute care facilities from Boston Medical Center, 2018

| Characteristics, hospitalizations (N) | No OUD (2297) |

OUD (166) |

P-value1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age 2 , mean ± SD | 69.1 ± 13.5 | 51.7 ± 12.3 | <0.001 |

| Male 3 | 49% | 69% | <0.001 |

| Race or ethnic group | <0.001 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 36% | 47% | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 44% | 32% | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 11% | 17% | |

| Other4 | 9.5% | 4.2% | |

| Language spoken | <0.001 | ||

| English | 79% | 92% | |

| Spanish | 7.1% | 7.2% | |

| Other | 14% | 0.60% | |

| Insurance type | <0.001 | ||

| Medicaid | 21% | 55% | |

| Medicare | 54% | 38% | |

| Private | 9% | 15% | |

| Other | 16% | 13% | |

| Homeless | 10% | 42% | <0.001 |

| Psychiatry consult | 18% | 27% | 0.005 |

| Addiction consult | 4.6% | 66% | <0.001 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 1.6% | 2.4% | 0.35 |

| Precaution status | |||

| Airborne | 1.9% | 7.8% | <0.001 |

| Contact | 25% | 49% | <0.001 |

| Contact Plus | 17% | 22% | 0.1 |

| Droplet | 4.4% | 11% | <0.001 |

| Charlson score | 0.26 | ||

| 0 | 18% | 22% | |

| 1–2 | 32% | 30% | |

| 3–4 | 20% | 15% | |

| >=5 | 31% | 34% | |

| Referrals, Mean ± SD | 6.6 ± 12.4 | 8.2 ± 8.2 | <0.001 |

| Proportion of referrals rejected, % | 65.5% | 83.3% | <0.001 |

| Disposition Status | <0.001 | ||

| Against medical advice | 22 (0.96%) | 22 (13%) | |

| Facility5 | 1860 (81%) | 103 (62%) | |

| Deceased | 40 (1.7%) | 3 (1.8%) | |

| Home with services | 242 (11%) | 15 (9.0%) | |

| Home or self care | 129 (5.6%) | 23 (14%) | |

| Other | 4 (0.17%) | 0 (0%) | |

Tests of significance performed using Chi squared or Fisher’s exact tests (age, alcohol use).

Age presented as a categorical variable is available in Appendix Exhibit A2

Gender was missing for 3 individuals.

Other includes American Indian/Native American, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Declined/Not available.

Disposition to any facility including respite, state-funded facilities.

Referrals and Rejections

Compared to hospitalized individuals without OUD, hospitalized individuals with OUD were referred to significantly (p<0.001) more post-acute care facilities (8.2 vs. 6.6). A significantly greater proportion of referrals for those with OUD were rejected than for those without OUD (83.3% vs. 65.5%). Hospitalized individuals with OUD experienced at least five rejections 45% of the time compared to 21.6% among those without OUD. Finally, there were significant differences in discharge location: 62% of individuals with OUD were discharged to any post-acute care facility (including public and respite) compared to 81% among individuals without OUD (Exhibit 1).

Post-acute care facility characteristics

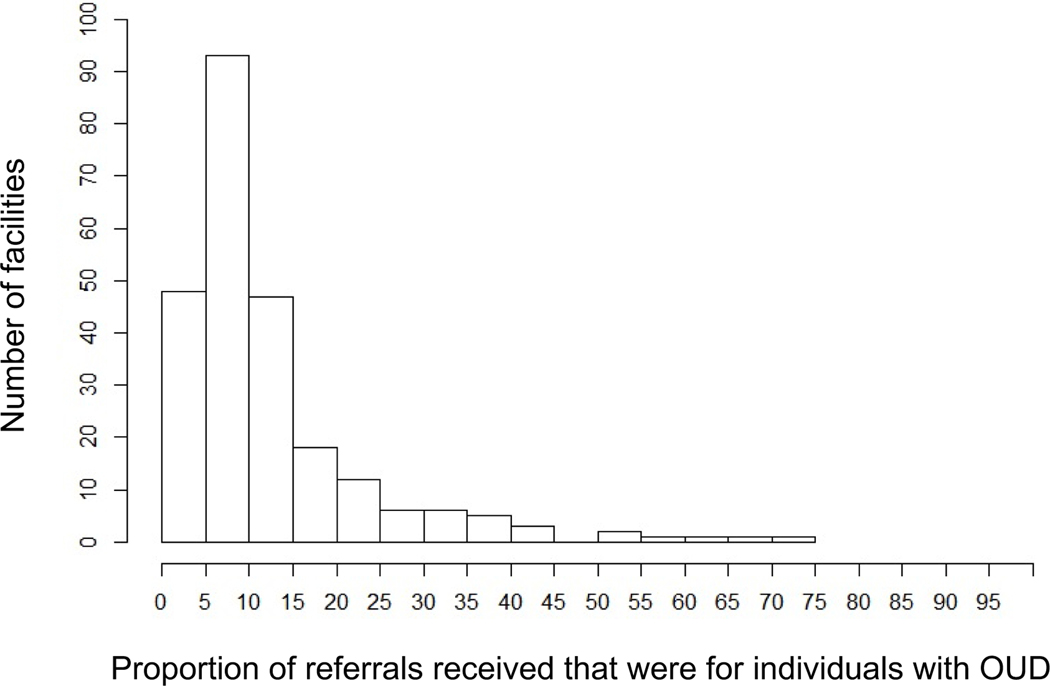

The mean proportion of referrals received by post-acute care facilities that were associated with OUD was 12.6% [Interquartile range (IQR) 5.7%, 14.3%; Min 1.2%, Max 71.4%] (Exhibit 2). We defined low OUD referral facilities as those with a proportion of OUD referrals that was less than 7.6%, medium OUD referral facilities as those that received more than 7.6% and less than 17.6%, and high OUD-referral facilities as those that received OUD referrals for more than 17.6% of all referrals. High OUD referral facilities had significantly (p≤0.004) younger patients, a smaller proportion of Black patients and female patients, more patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, and a higher proportion with daily pain. High OUD referral facilities also had more patients with Medicaid insurance, fewer with Medicare, fewer direct care hours per resident, and were more likely to be for profit. Additionally, high OUD referral facilities were less likely to be ranked as above-average facilities (Star Rating of 4 or 5) (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 2:

Distribution of proportion of referrals received for individuals with opioid use disorder (OUD) among cohort facilities (n=244), Boston Medical Center, 20181.

1The median proportion of referrals received for individuals with OUD was 12.6%. OUD referral facilities were grouped into high, medium, and low OUD referral facilities using the median plus or minus 5% to define the medium OUD referral facilities. Low OUD referral facilities were those which received <7.6% of referrals for individuals with OUD; medium OUD referral were defined as those with ≥7.6% and <17.6% referrals; high OUD referral facilities were those that received ≥17.6%.

Exhibit 3:

Multivariable logistic regression model results for referral rejection from a skilled nursing facility for individuals with opioid use disorder (OUD) compared to those without OUD, 20181

| Characteristics | Categories | Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Odds Ratio | Lower 95% Confidence Interval | Upper 95% Confidence Interval | P-value | ||

| OUD | 2.20 | 1.74 | 2.78 | <0.001 | |

| Facility Groups | Low OUD Referral Facilities | 1.61 | 1.46 | 1.76 | <0.001 |

| Medium OUD Referral Facilities | Ref | ||||

| High OUD Referral Facilities | 0.51 | 0.44 | 0.59 | <0.001 | |

| Age | 35–44 | 0.76 | 0.44 | 1.32 | 0.329 |

| 45–54 | 0.62 | 0.36 | 1.08 | 0.094 | |

| 55–64 | 0.48 | 0.29 | 0.81 | 0.005 | |

| 65–74 | 0.31 | 0.18 | 0.51 | <0.001 | |

| >=75 | 0.26 | 0.15 | 0.44 | <0.001 | |

| 18–34 | Ref | ||||

| Gender | Female | 0.80 | 0.70 | 0.92 | 0.001 |

| Race or ethnic group | Hispanic | 1.10 | 0.83 | 1.47 | 0.491 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.10 | 0.95 | 1.27 | 0.189 | |

| Other | 1.20 | 0.97 | 1.48 | 0.096 | |

| Non-Hispanic white | Ref | ||||

| Language | Spanish | 0.80 | 0.55 | 1.15 | 0.226 |

| Other | 0.84 | 0.71 | 1.00 | 0.057 | |

| English | Ref | ||||

| Insurance Type | Medicaid | 1.14 | 0.91 | 1.42 | 0.268 |

| Medicare | 0.80 | 0.64 | 0.99 | 0.045 | |

| Other | 0.85 | 0.67 | 1.08 | 0.191 | |

| Private | Ref | ||||

| Homelessness | 1.37 | 1.13 | 1.66 | 0.002 | |

| Psychiatry Consult | 1.576 | 1.34 | 1.83 | <0.001 | |

| Precaution Status | Air | 1.26 | 0.86 | 1.84 | 0.242 |

| Contact | 0.89 | 0.77 | 1.04 | 0.162 | |

| Contact Plus | 1.13 | 0.94 | 1.36 | 0.192 | |

| Droplet | 1.00 | 0.77 | 1.31 | 0.965 | |

| Alcohol use disorder (AUD) | 1.87 | 1.39 | 2.52 | <0.001 | |

Analysis is based on cohort of 16,503 referrals.

Model Results

In an adjusted multivariable logistic regression model, referrals for individuals with an OUD diagnosis had significantly higher odds of rejection [Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) 2.2, 95% Confidence Interval (95%CI) 1.7, 2.8]. Other factors associated with increased odds of rejection included having an alcohol use disorder (AOR 1.9, 95%CI 1.4, 2.5), experiencing homelessness (AOR 1.4, 95%CI 1.2–1.7), or receiving a psychiatry consult during the hospitalization (AOR 1.6, 95%CI 1.4, 1.8). Individuals aged 75 or older (AOR 0.25 95%CI 0.15, 0.44), women (AOR 0.81, 95%CI 0.71, 0.92), and those with Medicare insurance (AOR 0.80, 95%CI 0.64, 0.99) had decreased odds of rejection. Race and ethnicity were not significantly associated with facility rejection (Exhibit 3).

Referrals to low OUD referral facilities had greater odds of rejection (AOR 1.61, 95% 1.47, 1.77), while referrals to high OUD referral facilities had lower odds of rejection (AOR 0.51, 95% CI 0.44, 0.59) (Appendix Exhibit A4). Based on these findings and our a priori hypotheses that individuals with OUD would be more likely to be referred to post-acute care facilities with higher likelihood of acceptance, we tested for an interaction between OUD-status and facility category. We found significant interactions between OUD status and the low OUD facility group and no significant interaction with the high OUD referral group (Appendix Exhibit A3).20 In adjusted analyses stratified by facility group, the odds of an OUD-associated referral being rejected were lowest for high OUD referral facilities (AOR 1.8, 95%CI 1.4, 2.4), intermediate for medium OUD referral facilities (AOR 2.6, 95%CI 1.8, 3.6), and highest for low OUD referral facilities (AOR 3.4, 95%CI 1.9, 5.9) (Appendix Exhibit A4).20

Discussion

In this cohort of post-acute medical care referrals for hospitalized individuals, more than 8 in 10 referrals for individuals with OUD were rejected. Referrals associated with OUD had more than double the odds of rejection compared to referrals not associated with an OUD diagnosis when adjusting for clinical and demographic confounders. Previous research demonstrated that post-acute care facilities explicitly discriminate against individuals with OUD, in violation of state and federal policies.14 These results demonstrate that referral, rejection, and acceptance inequities for people with opioid use disorder are widespread and insidious, and not limited to individual cases of explicit discrimination. The post-acute care facilities in this study systematically reject individuals with OUD from medically necessary care despite public health guidelines and legal scrutiny.

We also found that facilities that receive a higher proportion of OUD referrals are less likely to reject a referral for an individual with OUD than facilities that receive a lower proportion of OUD referrals. This suggests that case managers may preferentially refer individuals with OUD to specific facilities where people with OUD are less likely to be rejected. Notably, 32% of facilities receiving at least 5 referrals did not receive a single referral for an individual with a diagnosis of OUD, evidence that post-acute care for individuals with OUD is segregated. This segregation is particularly problematic as facilities in the high-OUD referral group were less likely to be highly rated according to the CMMS Star Rating system. The fact that case managers sort referrals by OUD status to procure post-acute care also has implications for interpreting our study findings: as our study includes a selected cohort of individuals with OUD, our analysis likely underestimates the degree to which a diagnosis of OUD affects post-acute care acceptance. We did not find differences in rejection by race but this may reflect the fact that the majority of Black and Hispanic people in this study did not have OUD. Additional research should further scrutinize racial inequities in referral patterns and admissions among people with OUD.

Only 6 in 10 individuals with OUD referred to post-acute care were ultimately discharged to a nursing facility, which suggests that admissions practices have clinical implications and represent barriers to medically recommended care. It is possible that these barriers to discharge contribute to longer hospital stays, a risk factor for patient-directed or “against medical advice” discharge.8,21–23 Further, those that are successfully discharged to post-acute care may find themselves in lower-quality facilities based on referral locations and rejection probabilities.

These pervasive referral and rejection patterns provide further evidence of discrimination and inequities faced by individuals with OUD, and they specifically violate Massachusetts Department of Public Health guidance and the Americans with Disabilities Act. Though most of the referrals in this study were to facilities in Massachusetts, referrals throughout New England were included, suggesting these practices are not limited to one state or city. We suspect these practices are widespread, but this should be confirmed by additional studies in other locations.

There are several possible explanations for these practices including externalized stigma toward individuals with OUD which may be formally or informally codified in admissions criteria, lack of comfort with or expertise in OUD treatment, and regulations that make provision of buprenorphine or methadone for OUD logistically challenging for post-acute care facilities.24–28 To provide buprenorphine, facilities must either have an X-waivered prescriber or a relationship with an outside prescriber, which may become more widely available given recent regulation changes by the Department of Health and Human Services designed to increase access to buprenorphine.29 To provide methadone, a facility must coordinate with an opioid treatment program (OTP) to transport the patient to the program or transport the methadone to the facility.13 However, facilities frequently coordinate with specialist providers for other medical conditions. Changes to federal regulations that allow nursing facilities to administer methadone as occurs in acute care hospitals would reduce barriers. Additionally, some facilities may be concerned about adhering to regulations around the care received by people with OUD such as ensuring access to behavioral health care or liability for poor outcomes. These barriers may be overcome with increased education, coordination between hospitals and facilities, clinical champions, and additional legal enforcement. Many of these approaches have been successful in addressing barriers to addiction care in primary and inpatient care. The finding that the high OUD referral facilities were more likely to be for-profit facilities despite having less staffing support suggests that some facilities see a market opportunity and could develop expertise in providing this care.

People with OUD had increased odds of rejection even when controlling for other potentially stigmatized factors that facilities might use to make admissions decisions, such as experiencing homelessness, active psychiatric disease, or alcohol use disorder. While these other stigmatized conditions were also independently associated with increased odds of rejection, the independent association of OUD with rejection suggests that it is the presence of OUD and the medications used to treat it that are particularly scrutinized in admissions decisions.

This study’s strengths include its contribution to an improved understanding of admissions practices at post-acute medical care facilities. This study uses data from a unique, real-world electronic referral system, which allows more detailed examination of referral and admissions practices than studies based on administrative billing records of admitted patients. We additionally linked these referrals with relevant clinical data to adjust for confounding factors in our models. We also categorized referrals at the facility level based on the proportion of referrals that included an OUD diagnosis. This approach allowed for an assessment of referral sorting based on likelihood of acceptance. Lastly, linking facilities with clinical, financial, and ratings data from multiple sources of publicly available data allowed us to assess differences across OUD referral categories among a large number of facilities.

The finding that in Massachusetts individuals with OUD are routinely rejected from post-acute medical care and are more likely to be rejected than people without OUD has significance to policy makers, civil rights advocates, health care system leaders, clinicians, and people with OUD across the country. Additional research focused on the experiences of case managers, nursing facility staff, as well as patient outcomes is needed. Amidst the ongoing opioid crisis, it is essential that people with OUD have equitable access to high-quality post-acute medical care.

Conclusion

In an urban safety-net hospital, hospitalized individuals with OUD are routinely rejected by nursing facilities for medically necessary post-acute medical care. Individuals with OUD have more than double the odds of receiving a rejection compared to someone without OUD even after post-acute care referrals are segregated to reduce rejection rates. Efforts are needed to improve access to post-acute medical care for people with OUD.

Supplementary Material

Exhibit 2:

Characteristics of skilled nursing facilities that received low, medium, and high proportion of referrals for patients with opioid use disorder (OUD), 2018 1,2

| Low OUD Referral Facilities3 (N=97) | Medium OUD Referral Facilities (N=83) | High OUD Referral Facilities (N=41) | P-value4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acuity Index, (SD) 5 | 12.0 ± 1.5 | 12.1 ± 0.6 | 11.8 ± 1.2 | 0.19 |

| Resource Utilization index, (SD) 6 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.08 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.003 |

| Average age | 81.6 | 81.3 | 76.6 | 0.002 |

| Under age 65, (%) | 17.4% | 19.7% | 33.2% | <0.001 |

| Female admissions, (%) | 58.7% | 57.4% | 51.4% | 0.004 |

| Black admissions, (%) | 15.7% | 11.3% | 8.3% | 0.07 |

| Hispanic admissions, (%) | 4.2% | 6.0% | 4.6% | 0.91 |

| White admissions, (%) | 78.6% | 84.3% | 82.9% | 0.29 |

| Patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, (%) | 18.3% | 20.4% | 29.1% | 0.004 |

| Number of beds, (n) | 126.1 | 120.6 | 127.4 | 0.44 |

| Occupancy Rate, (%) | 81.9% | 84.1% | 86.6% | 0.28 |

| Medicaid, (%) | 61.1% | 63.7% | 69.9% | 0.02 |

| Medicare, (%) | 15.0% | 12.5% | 8.7% | 0.01 |

| Direct care hours per resident day | 3.9 | 3.7 | 3.3 | <0.001 |

| NP or PA onsite, (%) | 77% | 78% | 71% | 0.62 |

| Long stay residents with daily pain, (%) | 3.5 | 4.2 | 5.6 | 0.08 |

| Chain, (%) | 62% | 66% | 61% | 0.78 |

| For profit, (%) | 70% | 81% | 88% | 0.09 |

| Star Rating4, (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 1 | 4.1% | 4.8% | 27% | |

| 2–3 | 32% | 47% | 46% | |

| 4–5 | 57% | 48% | 24% | |

| Missing | 7.2% | 0% | 2.4% |

Data for 221 of 244 facilities that received referrals in our cohort. Twenty-three facilities had missing data and were excluded from this table.

Facility data from LTCFocus.org. Star Ratings were from Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Overall facility (n=244) mean for proportion of OUD-referrals was 12.6% (Interquartile Range 5.68, 14.29). Facilities with low OUD referrals were defined as those receiving below 7.6% OUD referrals (<12.6% - 5%). Medium OUD referrals were defined as those receiving 12.6% ± 5%. High OUD referrals were defined by receiving greater than 17.6% OUD referrals (>12.6% + 5%).

For tests of significance, we used Kruskall-Wallis for continuous variables, Chi-Squared for categorical variables, and Fisher’s exact test when sample sizes in each cell were small (i.e., For profit, Star Rating).

Acuity index is a measure of measure of residents’ need for assistance with activities of daily living

Resource utilization index is a measure of staff time needed to care for residents

Source of support:

Dr. Kimmel reports support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) (R25DA013582, R25DA03321, 1K23DA054363-01), and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (5T32AI052074) during this study. Ms. Rosenmoss was supported by the Boston University School of Medicine’s Medical Student Summer Research Program. Dr. Bearnot was supported by NIDA (K12DA043490). Dr. Walley reports support from NIDA (R25DA013582). Dr. Larochelle was supported by NIDA (K23 DA042168).

Conflicts of interest:

Dr. Kimmel consulted for Abt Associates on a Massachusetts Department of Public Health project to expand access to medications for opioid use disorder in post-acute medical care facilities. Dr. Larochelle had funds paid to his institution for consulting on research related to opioid use disorder treatment pathways from OptumLabs.

References

- 1.Owens PL, Weiss AJ, Barrett ML. Hospital Burden of Opioid-Related Inpatient Stays: Metropolitan and Rural Hospitals, 2016. [Internet]. Rockville, MA; 2020 May [cited 2021 Feb 25]. Available from: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/sidoverview.jsp [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ronan MV, Herzig SJ. Hospitalizations Related To Opioid Abuse/Dependence And Associated Serious Infections Increased Sharply, 2002–12. Health Aff. 2016. May;35(5):832–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deo SV, Raza S, Kalra A, Deo VS, Altarabsheh SE, Zia A, et al. Admissions for infective endocarditis in intravenous drug users [Internet]. Vol. 71, Journal of the American College of Cardiology. Journal of the American College of Cardiology; 2018. [cited 2019 May 29]. p. 1596–7. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0735109718304492 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Larochelle MR, Bernstein R, Bernson D, Land T, Stopka TJ, Rose AJ, et al. Touchpoints – Opportunities to predict and prevent opioid overdose: A cohort study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019. Nov 1;204:107537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song Z. Mortality Quadrupled Among Opioid-Driven Hospitalizations, Notably Within Lower-Income And Disabled White Populations. [cited 2019 Jun 24]; Available from: https://www-healthaffairs-org.ezproxy.bu.edu/doi/pdf/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Weiss Audrey J., Heslin Kevin C., Stocks Carol, Owens Pamela L. Hospital Inpatient Stays Related to Opioid Use Disorder and Endocarditis, 2016. HCUP Statistical Brief #256 [Internet]. Rockville, MD; 2020 Apr [cited 2021 Mar 26]. Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb256-Opioids-Endocarditis-Inpatient-Stays-2016.jsp [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Commonwealth of Massachusetts. An Assessment of Fatal and Nonfatal Opioid Overdoses in Massachusetts [Internet]. Boston; 2017. [cited 2018 Aug 20]. Available from: www.mass.gov/dph [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim JH, Fine DR, Li L, Kimmel SD, Ngo LH, Suzuki J, et al. Disparities in United States hospitalizations for serious infections in patients with and without opioid use disorder: A nationwide observational study. Wiese AD, editor. PLoS Med [Internet]. 2020. Aug 7 [cited 2020 Aug 25];17(8):e1003247. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheehan E. Circular Letter: DHCQ 16–11-662 [Internet]. Bureau of Health Care Safety and Quality, Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Boston, MA; 2016. [cited 2020 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.mass.gov/circular-letter/circular-letter-dhcq-16-11-662-admission-of-residents-on-medication-assisted#purpose [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Attorney’s Office vs Charlwell Operating LLC Representative, Charlwell Op. Settlement Agreement between the United States and Charlwell Operating, LLC [Internet]. Boston, MA; 2018. [cited 2019 Jul 8]. Available from: https://www.ada.gov/charlwell_sa.html [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Attorney’s Office vs Athena Health Care Systems. Settlement Agreement Between the United States of America and Athena Health Care Systems [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://www.ada.gov/athena_healthcare_sa.html

- 12.Wakeman SE, Rich JD. Barriers to post-acute care for patients on opioid agonist therapy; An example of systematic stigmatization of addiction. J Gen Intern Med [Internet]. 2017. Jan 8 [cited 2018 Apr 14];32(1):17–9. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11606-016-3799-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pytell JD, Sharfstein JM, Olsen Y. Facilitating Methadone Use in Hospitals and Skilled Nursing Facilities. Vol. 180, JAMA Internal Medicine. American Medical Association; 2020. p. 7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kimmel SD, Rosenmoss S, Bearnot B, Larochelle M, Walley AY. Rejection of Patients With Opioid Use Disorder Referred for Post-acute Medical Care Before and After an Anti-discrimination Settlement in Massachusetts. J Addict Med [Internet]. 2021;15(1):20–6. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/journaladdictionmedicine/Fulltext/9000/Rejection_of_Patients_With_Opioid_Use_Disorder.99197.aspx [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinstein ZM, Cheng DM, D’Amico MJ, Forman LS, Regan D, Yurkovic A, et al. Inpatient addiction consultation and post-discharge 30-day acute care utilization. Drug Alcohol Depend [Internet]. 2020;213:108081. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0376871620302465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-10-PCS (beta version) [Internet]. [cited 2021 Apr 22]. Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs10/ccs10.jsp

- 18.Long-Term Care: Facts on Care in the US - LTCFocus.org [Internet]. LTCFocus Public Use Data sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (P01 AG027296) through a cooperative agreement with the Brown University School of Public Health. [cited 2020 May 31]. Available from: http://ltcfocus.org/

- 19.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Five-Star Quality Rating System [Internet]. [cited 2021 Apr 22]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/CertificationandComplianc/FSQRS

- 20.To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online.

- 21.Kimmel SD, Kim J-H, Kalesan B, Samet JH, Walley AY, Larochelle MR. Against medical advice discharges in injection and non-injection drug use-associated infective endocarditis: A nationwide cohort study. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2020. Aug 5 [cited 2020 Aug 17]; Available from: https://academic.oup.com/cid/advance-article/doi/10.1093/cid/ciaa1126/5881411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Simon R, Snow R, Wakeman S. Understanding why patients with substance use disorders leave the hospital against medical advice: A qualitative study. Subst Abus. 2019; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Bearnot B, Mitton JA, Hayden M, Park ER. Experiences of care among individuals with opioid use disorder-associated endocarditis and their healthcare providers: Results from a qualitative study. J Subst Abuse Treat [Internet]. 2019. Apr 23 [cited 2019 Apr 25];102:16–22. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0740547218305956?dgcid=rss_sd_all [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai AC, Kiang MV., Barnett ML, Beletsky L, Keyes KM, McGinty EE, et al. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med [Internet]. 2019. Nov 26 [cited 2019 Dec 2];16(11):e1002969. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haffajee RL, Bohnert ASB, Lagisetty PA. Policy Pathways to Address Provider Workforce Barriers to Buprenorphine Treatment. Am J Prev Med [Internet]. 2018. Jun 1 [cited 2018 Jun 4];54(6):S230–42. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0749379718300746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bagley SM, Hadland SE, Carney BL, Saitz R. Addressing Stigma in Medication Treatment of Adolescents With Opioid Use Disorder. J Addict Med [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2019 Sep 25];11(6):415–6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28767537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olsen Y, Sharfstein JM. Confronting the stigma of opioid use disorder - And its treatment [Internet]. Vol. 311, JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. American Medical Association; 2014. [cited 2017 Nov 7]. p. 1393–4. Available from: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.2014.2147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fiscella K, Wakeman SE, Beletsky L. Buprenorphine Deregulation and Mainstreaming Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder: X the X Waiver. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019. Mar 1;76(3):229–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Becerra X. Practice Guidelines for the Administration of Buprenorphine for Treating Opioid Use Disorder [Internet]. Health and Human Services Department. 2021. Apr [cited 2021 Jun 3]. Available from: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/04/28/2021-08961/practice-guidelines-for-the-administration-of-buprenorphine-for-treating-opioid-use-disorder

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.