Abstract

Mobilizable shuttle plasmids containing the origin-of-transfer (oriT) region of plasmids F (IncFI), ColIb-P9 (IncI1), and RP4/RP1 (IncPα) were constructed to test the ability of the cognate conjugation system to mediate gene transfer from Escherichia coli to Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Only the Pα system caused detectable mobilization to yeast, giving peak values of 5 × 10−5 transconjugants per recipient cell in 30 min. Transfer of the shuttle plasmid required carriage of oriT in cis and the provision in trans of the Pα Tra1 core and Tra2 core regions. Genes outside the Tra1 core did not increase the mobilization efficiency. All 10 Tra2 core genes (trbB, -C, -D, -E, -F, -G, -H, -I, -J, and -L) required for plasmid transfer to E. coli K-12 were needed for transfer to yeast. To assess whether the mating-pair formation (Mpf) system or DNA-processing apparatus of the Pα conjugation system is critical in transkingdom transfer, an assay using an IncQ-based shuttle plasmid specifying its own DNA-processing system was devised. RP1 but not ColIb mobilized the construct to yeast, indicating that the Mpf complex determined by the Tra2 core genes plus traF is primarily responsible for the remarkable fertility of the Pα system in mediating gene transfer from bacteria to eukaryotes.

The plasmid-encoded process of bacterial conjugation is a major source of genetic variation in bacteria, enabling the horizontal transfer of plasmids and their diverse cargoes of adaptive genes of clinical, environmental, and evolutionary importance. Conjugation also causes the dissemination of plasmid-borne transposable elements and potentiates homologous recombination of chromosomal genes (9, 58). The promiscuity of conjugation is illustrated further by the laboratory demonstration of plasmid transfer from Escherichia coli to microbial eukaryotes (24, 25) and by the natural transfer of the T-DNA sector of the Ti plasmid from Agrobacterium tumefaciens to the nuclei of plant cells during tumorigenesis (27, 30, 36). Evidence that transkingdom gene exchange has actually occurred is provided by phylogenetic analyses of protein sequences showing lack of congruence between certain gene trees and the conventional species phylogeny (54).

As shown by enterobacterial systems, conjugation is a highly specific process involving a mating-pair formation (Mpf) system for cell aggregation coupled to a DNA transfer apparatus (12, 44). The conjugative pilus is a key component of Mpf and, in conjunction with the assembly proteins, may provide a transmembrane complex for DNA transport. Plasmid transfer is initiated by strand-specific cleavage of a unique nick site in the oriT region, which is typically <500 bp in size. Specific cleavage is mediated by the plasmid-encoded relaxase in a reaction that covalently links the protein to the 5′ terminus of the transfer intermediate (33). Some naturally occurring plasmids encode only a DNA transfer apparatus and cognate oriT and rely on a conjugative plasmid that is coresident in the bacterium to provide the Mpf functions (33). Such mobilizable plasmids include members of the IncQ group, typified by R300B (8.7 kb) and RSF1010 (10, 18).

Study of enterobacterial conjugation has focused on systems encoded by F-like plasmids and members of the IncPα group (12, 13, 44). The latter includes the very similar if not identical RK2, RP1, and RP4 plasmids and is closely related to the IncPβ group. The Pα transfer genes are organized into two distinct regions, Tra1 and Tra2, which cover almost half of the 60-kb plasmid (44). Tra2 consists of an array of 15 trb genes, of which the promoter-proximal loci trbB, -C, -D, -E, -F, -G, -H, -I, -J, and -L are essential for conjugation of E. coli K-12 and are described as the Tra2 core. The 10 genes are involved in biosynthesis of the conjugative pilus and production of stable mating aggregates (22, 35). The trbK gene, which is located within the Tra2 core region, functions in entry exclusion to prevent DNA transfer between cells that both harbor an IncPα plasmid (21). The Tra1 region contains 13 genes but only a core of five (traF, -G, -I, -J, and -K) is essential for transfer between E. coli K-12 strains. TraF protein acts as a specific protease in the maturation of the putative prepilin, TrbC (20). TraG protein is thought to couple the Mpf system to the DNA transfer-initiation complex which includes TraI, the relaxase, and TraJ and TraK as oriT-binding proteins (2, 33). Inclusion of traM with the Tra1 core significantly increases the transfer efficiency (35). The remaining Tra1 loci may be important for interspecies transfer. Indeed, there is evidence implicating TraC protein, which is a conjugatively transmissible DNA primase, and Upf54.4, previously known as TraN protein, in effective plasmid transfer between different gram-negative bacteria (31, 32, 42).

The transfer range of a plasmid is often wider than its replication maintenance or host range (40, 58). The wide transfer range of enterobacterial plasmids is emphasized by the finding that R751 (IncPβ) and F (IncFI) caused DNA transfer from E. coli to Saccharomyces cerevisiae (25). This observation leads to two general questions. Are all conjugation systems equally competent in causing DNA transfer between different biological kingdoms? If they are not, what are the genetic and molecular factors allowing some plasmids to transfer more promiscuously than others? To address these questions, we have compared the capacities of three paradigms of enterobacterial conjugative plasmid, namely, F, RP1/RP4, and ColIb-P9 (IncI1 [46]), to mediate transfer between E. coli and yeast.

To allow ready detection of transconjugants, we used mobilizable E. coli-yeast shuttle plasmids which contained two replicons, each allowing stable maintenance in one of the host organisms. Such two-replicon plasmids were converted into mobilizable units by the inclusion of the oriT region of F, ColIb-P9, or RP4. The constructs were efficiently mobilized between E. coli strains when the donor strain harbored the cognate conjugative plasmid to provide Mpf functions and the trans-acting components of the DNA transfer apparatus. This approach showed that the RP4 system is unusually promiscuous in mediating transkingdom gene exchange and led us to examine the factors responsible.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial and yeast strains.

The donor host strains were BW103 (leu recA1 rpsL cirA, [46]), HB101 (hsdS20 leuB6 proA2 recA13 rpsL20 supE44 ara-14 galK2 lacY1 mtl-1 xyl-5 thi-1 [6]), and C600 (leuB6 thr-1 supE44 lacY1 thi-1). Nalidixic acid and rifampin-resistant mutants are designated by the suffixes N and R, respectively. BW97 (leu thyA deoB rpsL cirA Δchl-uvrB gyr [46]) and C600R were used as recipients in bacterial conjugation. The yeast recipient was S150-2B (MATa his3-Δ leu2-3 leu2-112 trp1-289 ura3-52 2μm+ [41]).

Genetic selections.

Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg ml−1; chloramphenicol, 25 μg ml−1; kanamycin, 50 μg ml−1; nalidixic acid, 25 μg ml−1; rifampin, 25 μg ml−1; streptomycin, 50 μg ml−1. Synthetic minimal defined (SD) medium for yeast contained 0.67% yeast nitrogen base (Bio 101, Inc.) and 2% glucose. Supplements were histidine, tryptophan, and uracil (all at 20 μg ml−1) for YEp13-based shuttle vectors and leucine (30 μg ml−1), histidine, and tryptophan for YCp50-based vectors. Nalidixic acid was added to SD media to inhibit the conjugative activity of donor bacteria.

Plasmids.

The plasmids are detailed in Table 1. Both shuttle plasmids contained the enterobacterial replicon of pMB1, the parent of pBR322. In addition, YEp13 included part of the 2μm circle, which is a natural nuclear plasmid of S. cerevisiae, while YCp50 contained the yeast chromosomal ARS1 (autonomously replicating sequence) element plus the CEN4 (centromere) sequence to ensure stable partitioning. pAC87 contains the 1.6-kb BamHI/HindIII fragment of pLG253 (28); the fragment includes the 1.6-kb PstI fragment of ColIb-P9 encompassing the oriT region (from nucleotide 733 upstream or 5′ of the nic site to nucleotide 833 downstream). pAC88 carries a 1.3-kb HindIII/SphI fragment of pJF142 (45), containing the RP4 oriT region on a 776-bp XmaIII fragment (RP4 coordinates 50994 to 51770, accession no. L27758 [44]). pSB2 contains F oriT isolated from pXRD606 (55) on a 1.1-kb BglII fragment (F coordinates 1 to 1077, accession no. U01159 [13]) and inserted into the unique BamHI site of YEp13. pSB12 contains the RP4 Tra1 region (traA-upf54.8) on a 15.7-kb BamHI/HindIII fragment of pVWDG23110Δ0.1 (RP4 coordinates 38970 to 54709, accession no. L27758). pSB13 was constructed by inserting the 7.6-kb BamHI fragment of pDB126, which carries the RP4 Tra1 core region (traF-M, RP4 coordinates 45893 to 53462), into the unique BamHI site of YCp50. The orientation of the insert in pSB13 was determined to be the same as that in pSB12 by restriction analysis. Shuttle vector pSB41 was constructed by ligating R300B and YCp50 together at their unique EcoRI restriction sites.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used

| Plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| pAC87 | YEp13 Ω(ColIb-P9 oriT 1.55-kb BamHI/HindIII pLG253) Apr | This work |

| pAC88 | YEp13 Ω(RP4 oriT 1.3-kb HindIII/SphI pJF142) Apr | This work |

| pDB126 | ColD replicon Ω(RP4 traF-M trbB-M) Cmr | 2 |

| pLG221 | IncI1 ColIb-P9 drd-1 cib::Tn5 Kmr | See reference 42 |

| pML123 | ColD replicon Ω(RP4 trbB-M) Cmr | 35 |

| pOX38-Km | IncFI (f1 HindIII fragment of F) Kmr | See reference 47 |

| pSB2 | YEp13 Ω(F oriT 1.1-kb BglII pXRD606) Apr | This work |

| pSB12 | YCp50 Ω(RP4 traA-upf54.8 15.6-kb BamHI/HindIII pVWDG23110Δ0.1) Apr | This work |

| pSB13 | YCp50 Ω(RP4 traF-M 7.6-kb BamHI pDB126) Apr | This work |

| pSB41 | YCp50 Ω(R300B 8.7-kb EcoRI) Apr | This work |

| pUB307 | IncPα RP1Δbla Tcr Kmr | 5 |

| pVWDG23110Δ0.1 | pBR329 Ω(RP4 traA-upf54.8) Kmr | 35 |

| R300B | IncQ Smr Sur | 18 |

| YCp50 | pMB1 replicon Ω(CEN4 ARS1 URA3) Apr Tcr Ura+ | 39 |

| YEp13 | pMB1 replicon Ω(2μm ORI/STB LEU2) Apr Tcr Leu+ | 7 |

Conjugation.

Donor and recipient bacteria were grown in nutrient broth at 37°C for three mass doublings to about 2 × 108 organisms per ml. Volumes (0.5 ml) were mixed and collected on a cellulose-acetate filter (Sartorius; 0.45-μm pore size; 25-mm diameter) which was incubated for 1 h at 37°C on prewarmed nutrient agar. Cells were resuspended by vigorous agitation and plated at appropriate dilutions on media selective for transconjugants. The yeast recipient strain was S150-2B. Cells were grown in YEPD (1% yeast extract [Oxoid Ltd.], 2% bacteriological peptone [Oxoid Ltd.], 2% glucose) medium for three mass doublings at 30°C, harvested in mid-exponential phase, and resuspended at a concentration of 2 × 108 cells ml−1. A 0.5-ml volume was mixed with an equal volume of donor bacteria, grown as described above, and added to a filter which was incubated at 30°C for 1 h on a plate of prewarmed YEPD. Resuspended cells were then plated on SD medium supplemented appropriately to select transconjugants.

Other methods.

Isolation of plasmid DNA from bacteria, bacterial transformation, recombinant DNA techniques, and Southern hybridization tests involved standard methods (49). Plasmid DNA was rescued from yeast by the glass bead-phenol lysis method (26). Yeast transformation was by the lithium acetate-polyethylene glycol method (15).

RESULTS

Plasmid transfer between E. coli and yeast.

E. coli-yeast conjugation was originally observed following cocultivation of donor and recipient cells on the surface of an agar medium selective for yeast transconjugants (25). This method was found to be unreliable for quantifying transfer due to the prolonged opportunity for transfer on the selective medium. The protocol developed here limited conjugation to a defined period on a complete agar medium followed by plating on selective medium containing nalidixic acid. Nalidixic acid is a powerful inhibitor of conjugative DNA transfer from sensitive bacteria (59). The quinolone had no discernible effect on the growth of yeast recipients at the concentration used (25 μg ml−1), but higher concentrations of nalidixic acid are known to cause a transient block in the yeast cell cycle at START (53).

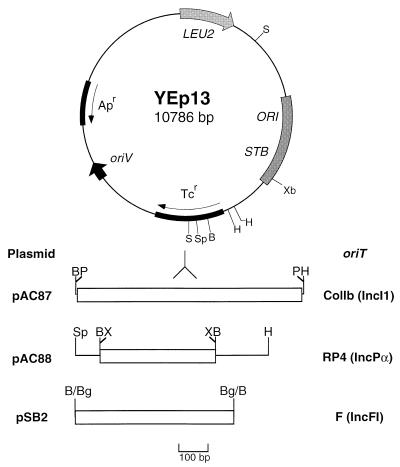

A conjugation protocol supporting rapid production of transconjugants was developed with the Pα system. The shuttle vector was based on YEp13 and contained the RP4 oriT region inserted into the tetracycline resistance gene (Fig. 1). Yeast transconjugants were detectable within 10 min of mixing the parental strains in a 1:1 ratio and reached plateau yields by about 30 min. The mean yield of pAC88 transconjugants at 60 min was 3.0 × 10−5 (n = 60 experiments) per yeast recipient cell. In contrast to previous observations of structural rearrangements (24), plasmids sampled from yeast transconjugants had the expected molecular structure. This was demonstrated by Southern hybridization analysis of DNA samples from 29 transconjugants, which were cleaved with XbaI to linearize pAC88 and probed with the RP4 oriT fragment. In another test, plasmids from 17 yeast transconjugants were rescued into E. coli and found to have the expected HindIII-SalI restriction fragments (4). Use of recA donor bacteria may account for the stability of the constructs by minimizing rearrangements prior to transfer.

FIG. 1.

Construction of mobilizable shuttle vectors. Shuttle vectors were based on YEp13. Replication and selection in E. coli are conferred by the oriV, Tcr, and Apr elements of pBR322. The ORI/STB region of the 2μm yeast plasmid allows stable replication in yeast. Selection in yeast is achieved by leucine prototrophy of a leucine auxotroph. Mobilizable vectors were constructed by inserting the oriT region of ColIb-P9, RP4, and F into the Tcr gene of YEp13. Restriction sites are as follows: B, BamHI; Bg, BglII; H, HindIII; P, PstI; S, SalI; Sp, SphI; X, XmaIII; Xb, XbaI.

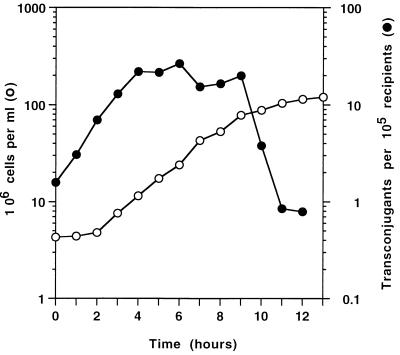

While the Pα system caused transfer to yeast in all growth phases, transfer was 15-fold more efficient when the cells were growing exponentially rather than when they were exiting or entering stationary phase (Fig. 2). Several other laboratory strains of yeast were as competent recipients as S150-2B, although haploid strains were some 80-fold more effective than diploids. There is no obvious explanation, but there are known differences between the surfaces of haploid and diploid yeast cells (37).

FIG. 2.

Capacity of yeast cells to receive plasmids at different stages in the growth cycle. YEPD complete medium was inoculated with a sample of stationary-phase yeast cells of strain S150-2B to give an initial concentration of 4 × 106 cells ml−1. The culture was sampled at 1-h intervals to determine cell titer (○). Samples, concentrated to give 2 × 108 cells ml−1, were mixed with BW103(pUB307 pAC88) donors for 1 h to determine transconjugant production (•).

IncPα plasmids are unusually effective in mediating E. coli-yeast conjugation.

Construction of shuttle vectors containing the oriT region of IncFI, IncI1, and IncPα plasmids (Fig. 1) allowed the three distinct conjugation systems to be compared for their capacities to mediate transfer to yeast. Donor strains of E. coli BW103 were constructed to contain each of the shuttle plasmids plus the cognate conjugative plasmid, and transfer frequencies to E. coli and yeast recipients were compared (Table 2). Only the Pα system gave detectable DNA transfer to yeast; if the FI and I1 systems are capable of causing such transfers, they do so at very low frequencies (<3 × 10−7 transconjugants per recipient). The shuttle plasmids containing the F and I1 oriT regions were mobilized very efficiently between E. coli strains, and both were capable of transforming yeast to leucine prototrophy. Taken together, the results demonstrate inherent differences in the abilities of different conjugation systems to transfer DNA to yeast and confirm the concept that IncPα plasmids are exceptionally promiscuous.

TABLE 2.

Mobilization of shuttle vectors to E. coli and yeast

| Donor strain | System | Transfer frequencya (E. coli) | Mobilization frequencyb

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Yeast | |||

| BW103(pUB307 pAC88) | Pα | 9.8 × 10−1 | 9.8 × 10−1 | 5.7 × 10−5 |

| BW103(pLG221 pAC87) | I1 | 1.0 | 9.5 × 10−1 | <3 × 10−7 |

| BW103(pOX38-Km pSB2) | FI | 5.2 × 10−1 | 5.1 × 10−1 | <3 × 10−7 |

Number of Kmr Nalr BW97 bacterial transconjugants carrying the conjugative plasmid per input recipient cell.

Number of Apr Nalr BW97 bacterial or LEU+ S150-2B yeast transconjugants carrying the mobilizable plasmid per input recipient cell. Values are the means of three experiments.

The Pα Tra1 and Tra2 core regions are sufficient for transfer to yeast.

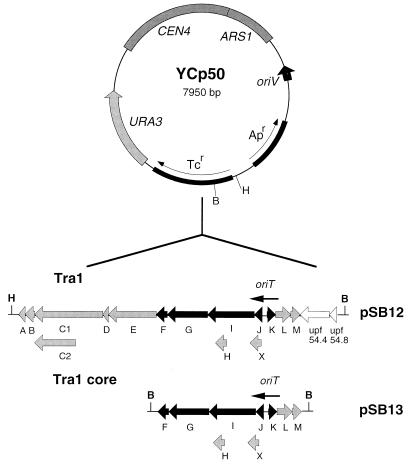

The RP4 Tra1 and Tra2 regions have been physically separated to form a bipartite system in which Tra1 and Tra2 are carried on separate compatible plasmids (34). We adapted this system by constructing two E. coli-yeast shuttle plasmids that were based on YCp50 and contained the Pα oriT region in its normal location within Tra1 (pSB12) or the Tra1 core (pSB13 [Fig. 3]). Neither pSB12 nor pSB13 was capable of transferring to yeast without provision of the Tra2 core region in trans on the compatible plasmid pML123 (Table 3). Similarly, the Tra2 core was incapable of causing transfer without trans-acting Tra1 functions, as shown by the failure of pML123 to mobilize the shuttle (pAC88) carrying Pα oriT alone. Conjugation of organisms other than E. coli K-12 may require additional plasmid-encoded factors (35). This does not apply to E. coli-yeast conjugation since pSB12 and pSB13 transferred to yeast at similar frequencies provided that the donor carried pML123. Thus, only the Tra1 plus Tra2 core regions are required for efficient transfer to yeast; no IncP plasmid locus outside of these core regions is necessary.

FIG. 3.

E. coli-yeast shuttle plasmids containing the Tra1 region (pSB12) and Tra1 core (pSB13) of RP4. The constructs are based on the yeast centromeric plasmid YCp50, allowing detection of transfer to yeast by uracil prototrophy. Horizontal boxes shown in black indicate Tra1 core genes essential for transfer between E. coli K-12 strains when the donor strain also expresses Tra2 functions in trans. Other Tra1 genes are indicated in gray. Addition of traM to the Tra1 core genes increases the transfer efficiency (35). Restriction sites shown are as follows: B, BamHI; H, HindIII.

TABLE 3.

IncPα Tra regions required for transfer to yeast

| Donor strain | Tra region(s) | Transfer efficiencya |

|---|---|---|

| HB101(pSB12) | Tra1 | <1.1 × 10−7 |

| HB101(pSB13) | Tra1 core | <1.1 × 10−7 |

| HB101(pML123 pAC88) | Tra2 | <1.1 × 10−7 |

| HB101(pML123 pSB12) | Tra1 and Tra2 | 1.5 × 10−5 |

| HB101(pML123 pSB13) | Tra1 core and Tra2 | 1.5 × 10−5 |

Expressed as number of URA+ or LEU+ S150-2B transconjugants per recipient cell. Values are the means of three experiments.

RP4 Tra2 genes essential for transfer to yeast.

The Tra2 core genes of IncPα plasmids are required for the production of pilus-like structures and plasmid transfer and may contribute the actual DNA transport apparatus (22). Are the same genes required for transfer to yeast? This question was addressed by using a set of mutant plasmids based on pML123 and containing a 14-bp multiple reading frame insertion (MURFI) linker mutation in each of the core Tra2 genes (22, 35). The linker contains an amber stop codon in all six reading frames. HB101 donors of this set of mutant plasmids were tested for the ability to mobilize pSB12 to both E. coli and yeast. In the positive control where the donor strain carried pML123 with the wild-type trb genes, 8 × 10−1 Apr Nalr [BW97(pSB12)] bacterial transconjugants and 1.4 × 10−5 URA+ [S150-2B(pSB12)] yeast transconjugants were generated. Transconjugant production in bacteria and in yeast was eliminated (<1.1 × 10−7 per recipient) when pML123 carried trbB5, trbC45, trbD45, trbE402, trbF9, trbG145, trbH13, trbI135, trbJ180, or trbL184 as a single mutation. The linker mutations have no detectable polar effects on translation of downstream genes with the exception of trbB5 and trbI135, each of which apparently interferes with expression of the adjacent gene trbC or trbJ, respectively (22). The pML123mtrbB204 plasmid, which encodes a functional TrbB protein of reduced activity, gave nearly normal levels of yeast transconjugants (9.4 × 10−6 per recipient). Mutation trbK9 had no effect on pSB12 mobilization to BW97 and little effect on pSB12 transfer to yeast (8.6 × 10−6 transconjugants per S150-2B recipient). Thus, trbB, -C, -D, -E, -F, -G, -H, -I, -J, and -L are required for transfer to yeast, as they are for transfer to E. coli K-12 recipients. TrbK protein, whose principal role is in surface exclusion, is not required for transfer to E. coli or to yeast.

The Mpf system determines the transfer promiscuity of IncPα plasmids.

To test whether the promiscuity of the Pα core system can be attributed to the Mpf or DNA-processing apparatus, a test was developed based on mobilization of the IncQ plasmid R300B. IncQ plasmids are mobilized efficiently by IncI1 and IncP plasmids (60). Mobilization by an IncPα plasmid requires the products of the Tra2 core—excepting TrbK—plus TraF and TraG of Tra1 (22, 35). In addition to carrying a specific oriT, the IncQ plasmid specifies its own Mob proteins for the DNA-processing reactions, which cannot be replaced by the equivalent proteins of the conjugative plasmid (10). The test used here compared the abilities of the Pα and I1 systems to mobilize a shuttle vector (pSB41) carrying the mob-oriT region of R300B; the prediction was that if the Pα DNA-processing apparatus is responsible for transfer promiscuity, then the Pα and I1 systems should mobilize pSB41 to yeast with similar frequencies since its transfer is mediated by the native R300B apparatus. However, if the Mpf system is responsible for transkingdom promiscuity, only the Pα system should support pSB41 mobilization to yeast.

As observed previously (60), the Pα system was 10-fold more efficient than the I1 system in causing mobilization between E. coli strains (Table 4). The difference is attributed to variation in the activity of TraG-like proteins to couple the DNA-processing system of the IncQ plasmid to the Mpf system of the conjugative plasmid (33). The IncPα plasmid caused significant mobilization of pSB41 to yeast cells, showing that the IncQ Mob system cooperates productively with the Pα Mpf system in transkingdom transfer. In contrast, the IncI1 plasmid effected no detectable mobilization of pSB41 to yeast. These findings point to the conclusion that the Mpf apparatus of IncPα plasmids is responsible for the remarkable effectiveness of these elements in mediating transkingdom gene exchange.

TABLE 4.

Mobilization of an IncQ-derived shuttle vector to yeast

| Donor strain | System | Transfer efficiencya

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli (C600R) | Yeast (S150-2B) | ||

| C600N(pUB30 pSB41) | Pα | 1.0 | 3.2 × 10−6 |

| C600N(pLG221 pSB41) | I1 | 0.11 | <1.7 × 10−8 |

Expressed as number of Apr Rifr C600R and URA+ S150-2B transconjugants per recipient cell. Values are the means of three experiments.

DISCUSSION

While the FI, I1, and Pα transfer systems described here supported very efficient mobilization of the cognate shuttle plasmid between E. coli strains, only the Pα system mediated detectable DNA transfer to yeast. Production of rare F-mediated yeast transconjugants was reported elsewhere (25). However, those studies involved a multicopy recombinant to specify F conjugative functions, which might account for the difference since such constructs are known to provide elevated levels of Tra proteins per cell (29). The RP1-based system used here generated about 3 × 10−5 transconjugants per yeast recipient within 60 min. This productivity compares favorably with that of an extended conjugation system which gave ∼3 × 10−7 Pβ-mediated transconjugants per yeast recipient (25) and with a Pα-based method in which the yield of transconjugants peaked at a value similar to that reported here but only after 12 h of cocultivation of donor and recipient cells (43). The E. coli-to-yeast transfer described here was due to authentic conjugation, as shown by the requirement for the RP4 Tra1 and Tra2 regions. Other confirmatory evidence is that the transfers were insensitive to the addition of DNase I and required contact between the E. coli and yeast cells, as well as carriage of oriT in cis by the shuttle plasmid (4).

The Pα system also appears to be unusually promiscuous in promoting gene exchange between gram-negative bacteria. For example, the Pα and F systems were found to be equally proficient in mediating conjugation of E. coli strains but the Pα system was some 10,000-fold more proficient than F in effecting DNA transport from E. coli to Pseudomonas aeruginosa (19). Likewise, the Pα system was relatively more proficient than the I1 system in mediating DNA transport from E. coli to pseudomonads: specifically, the Pα (RP4) system mobilized an IncQ plasmid (R300B) to Pseudomonas putida (KT2442) and to E. coli recipients with similar frequencies, whereas the I1 (pLG221) system mobilized R300B to P. putida fivefold less effectively than to E. coli (54a).

The possibility that transkingdom transfer requires ancillary genes of the IncPα plasmid is ruled out by the finding that the combination of the Tra1 core and Tra2 core regions was almost as effective as the entire plasmid genome. The requirements for E. coli-yeast conjugation include the same 10 Tra2 genes as are required for efficient transfer between E. coli K-12 strains (22, 35). The same set of Tra2 genes was required for RP4-mediated transfer from E. coli to Streptomyces lividans, although trbF was found to stimulate transfer rather than to be essential (16). Thus, while loci adjacent to the Tra1 core enable productive conjugation of some of the natural hosts of IncP plasmids, as evidenced by the contributions of TraC DNA primase and Upf54.4 to the fertility of some but not all gram-negative bacterial conjugations (31, 32, 42), the loci do not contribute to transfer from bacteria to yeast. Possibly, the products of these genes cannot function in eukaryotic cells.

The capacity of the Pα system—but not the I1 system—to mobilize the IncQ-based shuttle vector to yeast indicates that the Mpf system of IncPα plasmids is primarily responsible for effecting transkingdom gene transfer. One possible explanation is that the molecular interactions between donor and recipient cell surfaces are less stringent in the Pα system than in others. Different mating systems do vary in their requirements: for example, the I1 and F systems are affected adversely by loss of lipopolysaccharide components from E. coli or Salmonella typhimurium recipients, whereas transfer by the Pα system was unaffected by changes in lipopolysaccharide structure and may involve another cell surface moiety (1, 11, 14, 23). In order to understand the cellular interactions further, we have isolated conjugation-deficient yeast mutants. At least one of the mutants displays altered cell surface properties (4).

The Pα Tra2 region is also thought to contribute to the transmembrane DNA transport apparatus (22), but there is no obvious reason why the transport structure per se should influence promiscuity. In the Ti Vir, system the T-DNA is apparently transferred into the plant nucleus in a specific nucleoprotein complex that includes VirD2 relaxase and hundreds of molecules of the VirE2 single-stranded DNA-binding protein (3, 27). These proteins in the T complex are thought to promote entry of the DNA into the cell nucleus. In Pα-mediated bacterial conjugation, the transferring DNA strand is also transmitted in a nucleoprotein complex that includes multiple molecules of the 117-kDa TraC protein (plasmid primase) and possibly the relaxase (33, 47). However, TraC does not facilitate transfer into the yeast nucleus since the basic Pα transfer system defined here operates independently of the primase gene. Possibly, naked single-stranded DNA enters the yeast nucleus during conjugation, as can occur in transformation of yeast spheroplasts (52). Nuclear uptake of DNA lacking a VirE2 analogue may be inefficient; if so, the yield of yeast transconjugants reported here underestimates the efficiency of DNA transfer into the yeast cytosol.

The biological impact of transkingdom conjugation is unclear. If it occurs in nature, the entrant DNA could be integrated into the resident genome by homologous recombination or, if there is insufficient nucleotide sequence identity, by illegitimate recombination. The latter has been observed to occur in yeast (17, 50). The Ti Vir system is the only dedicated system known to mediate transfer from bacteria to eukaryotes, including yeast (8). Interestingly, a number of the Pα Tra2 genes are homologous to components of the VirB operon (30, 36), which is thought to specify cell-contact formation and a transmembrane bridge for transfer of the T complex to plant cells (see reference 3). The homology of the Tra2 and VirB regions may explain the competence of the Pα Mpf system in transkingdom gene exchange.

The relationship between Tra2 and VirB regions extends further to include seven of the genes of the Ptl (pertussis toxin liberation) system of the human pathogen Bordetella pertussis (57), which is viewed as a derivative of a bacterial conjugation system (61). The VirB, Tra2, and Ptl systems are described as type IV secretion systems that transport macromolecules as diverse as protein-DNA complexes on the one hand and an oligomeric protein on the other (38, 48). Some genetic systems may even support transport of more than one substrate, since the dot-icm genes of Legionella pneumophila determine secretion of a putative protein from bacteria to mammalian cells and also a mating process for mobilization of IncQ plasmids to L. pneumophila and E. coli recipients (51, 56). These observations raise the possibility that the Pα Mpf system may be able to cause productive interactions of bacteria and mammalian cells, supporting transfer of a DNA-protein complex, naked DNA, or even DNA-free protein(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Peter Bennett for pUB307 and Richard Deonier for pXRD606. We are indebted to Erich Lanka for useful discussions and the gift of many plasmids constructed by his group to contain parts of the Pα conjugation system.

This work was supported by MRC grant G9321196MB to B.M.W. and W. J. Brammar and by the award of an MRC Research Studentship to S.B.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anthony K G, Sherburne C, Sherburne R, Frost L S. The role of the pilus in recipient cell recognition during bacterial conjugation mediated by F-like plasmids. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:939–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balzer D, Pansegrau W, Lanka E. Essential motifs of relaxase (TraI) and TraG proteins involved in conjugative transfer of plasmid RP4. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4285–4295. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.14.4285-4295.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baron C, Llosa M, Zhou S, Zambryski P C. VirB1, a component of the T-complex transfer machinery of Agrobacterium tumefaciens, is processed to a C-terminal secreted product, VirB1. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1203–1210. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.4.1203-1210.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bates S. Trans-kingdom plasmid transfer from bacteria to yeast. Ph.D. thesis. Leicester, United Kingdom: University of Leicester; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett P M, Grinsted J, Richmond M H. Transposition of TnA does not generate deletions. Mol Gen Genet. 1977;154:205–211. doi: 10.1007/BF00330839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyer H W, Roulland-Dussoix D. A complementation analysis of the restriction and modification of DNA in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1969;41:459–472. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broach J R, Hicks J B. Replication and recombination functions associated with the yeast plasmid, 2μ circle. Cell. 1980;21:501–508. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90487-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bundock P, den Dulk-Ras A, Beijersbergen A, Hooykaas P J J. Trans-kingdom T-DNA transfer from Agrobacterium tumefaciens to Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1995;14:3206–3214. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clewell D B, editor. Bacterial conjugation. New York, N.Y: Plenum Publishing Corp.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Derbyshire K M, Hatfull G, Willetts N. Mobilization of the non-conjugative plasmid RSF1010: a genetic and DNA sequence analysis of the mobilization region. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;206:161–168. doi: 10.1007/BF00326552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duke J, Guiney D G., Jr The role of the lipopolysaccharide structure in the recipient cell during plasmid-mediated bacterial conjugation. Plasmid. 1983;9:222–226. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(83)90024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Firth N, Ippen-Ihler K, Skurray R A. Structure and function of the F factor and mechanism of conjugation. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 2377–2401. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frost L S, Ippen-Ihler K, Skurray R A. Analysis of the sequence and gene products of the transfer region of the F sex factor. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:162–210. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.2.162-210.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frost L S, Simon J. Studies on the pili of the promiscuous plasmid RP4. In: Kado C I, Crosa J H, editors. Molecular mechanisms of bacterial virulence. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1993. pp. 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geitz D, St. Jean A, Woods R A, Schiestl R H. Improved method for high efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:1425. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.6.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giebelhaus L A, Frost L, Lanka E, Gormley E P, Davies J E, Leskiw B. The Tra2 core of the IncPα plasmid RP4 is required for intergeneric mating between Escherichia coli and Streptomyces lividans. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6378–6381. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.21.6378-6381.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gjuračić K, Zgaga Z. Illegitimate integration of single-stranded DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;253:173–181. doi: 10.1007/s004380050310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grinter N J, Barth P T. Characterization of SmSu plasmids by restriction endonuclease cleavage and compatibility testing. J Bacteriol. 1976;128:394–400. doi: 10.1128/jb.128.1.394-400.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guiney D G. Host range of conjugation and replication functions of Escherichia coli sex factor F lac: comparison with the broad host range plasmid RK2. J Mol Biol. 1982;162:699–703. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90397-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haase J, Lanka E. A specific protease encoded by the conjugative DNA transfer systems of IncP and Ti plasmids is essential for pilus synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5728–5735. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.18.5728-5735.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haase J, Kalkum M, Lanka E. TrbK, a small cytoplasmic lipoprotein, functions in entry exclusion of the IncPα plasmid RP4. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6720–6729. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6720-6729.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haase J, Lurz R, Grahn M, Bamford D H, Lanka E. Bacterial conjugation mediated by plasmid RP4: RSF1010 mobilization, donor-specific phage propagation, and pilus production require the same Tra2 core components of a proposed DNA transport complex. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4779–4791. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.16.4779-4791.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Havekes L, Tommassen J, Hoekstra W, Lugtenberg B. Isolation and characterization of Escherichia coli K-12 F− mutants defective in conjugation with an I-type donor. J Bacteriol. 1977;129:1–8. doi: 10.1128/jb.129.1.1-8.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayman G T, Bolen P L. Movement of shuttle plasmids from Escherichia coli into yeasts other than Saccharomyces cerevisiae using trans-kingdom conjugation. Plasmid. 1993;30:251–257. doi: 10.1006/plas.1993.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heinemann J A, Sprague G F., Jr Bacterial conjugative plasmids mobilize DNA transfer between bacteria and yeast. Nature. 1989;340:205–209. doi: 10.1038/340205a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoffman C S, Winston F. A ten-minute DNA preparation from yeast efficiently releases autonomous plasmids for transformation of Escherichia coli. Gene. 1987;57:267–272. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hooykaas P J J, Beijersbergen A G M. The virulence system of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1994;32:157–179. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Howland C J, Wilkins B M. Direction of conjugative transfer of IncI1 plasmid ColIb-P9. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4958–4959. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.10.4958-4959.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson D A, Willetts N S. Construction and characterization of multicopy plasmids containing the entire F transfer region. Plasmid. 1980;4:292–304. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(80)90068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kado C I. Promiscuous DNA transfer system of Agrobacterium tumefaciens: role of the virB operon in sex pilus assembly and synthesis. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:17–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishnapillai V. Molecular genetic analysis of bacterial plasmid promiscuity. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1988;54:223–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1988.tb02744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lanka E, Barth P T. Plasmid RP4 specifies a deoxyribonucleic acid primase involved in its conjugal transfer and maintenance. J Bacteriol. 1981;148:769–781. doi: 10.1128/jb.148.3.769-781.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lanka E, Wilkins B M. DNA processing reactions in bacterial conjugation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:141–169. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lessl M, Balzer D, Lurz R, Waters V L, Guiney D G, Lanka E. Dissection of IncP conjugative plasmid transfer: definition of the transfer region Tra2 by mobilization of the Tra1 region in trans. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2493–2500. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.8.2493-2500.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lessl M, Balzer D, Weyrauch K, Lanka E. The mating pair formation system of plasmid RP4 defined by RSF1010 mobilization and donor-specific phage propagation. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6415–6425. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.20.6415-6425.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lessl M, Lanka E. Common mechanisms in bacterial conjugation and Ti-mediated T-DNA transfer to plant cells. Cell. 1994;77:321–324. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lipke P N, Taylor A, Balbu C E. Morphogenic effects of α-factor on Saccharomyces cerevisiae a cells. J Bacteriol. 1976;127:610–618. doi: 10.1128/jb.127.1.610-618.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lory S. Secretion of proteins and assembly of bacterial surface organelles: shared pathways of extracellular protein targeting. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1998;1:27–35. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(98)80139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma H, Kunes S, Schatz P J, Botstein D. Plasmid construction by homologous recombination in yeast. Gene. 1987;58:201–216. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90376-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mazodier P, Davies J. Gene transfer between distantly related bacteria. Annu Rev Genet. 1991;25:147–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.25.120191.001051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McLeod M, Volkert F, Broach J. Components of the site specific recombination system encoded by the yeast plasmid 2μm circle. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1984;49:779–787. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1984.049.01.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Merryweather A, Barth P T, Wilkins B M. Role and specificity of plasmid RP4-encoded DNA primase in bacterial conjugation. J Bacteriol. 1986;167:12–17. doi: 10.1128/jb.167.1.12-17.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nishikawa M, Suzuki K, Yoshida K. Structural and functional stability of IncP plasmids during stepwise transmission by transkingdom mating: promiscuous conjugation of Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Jpn J Genet. 1990;65:323–334. doi: 10.1266/jjg.65.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pansegrau W, Lanka E, Barth P T, Figurski D H, Guiney D G, Haas D, Helinski D R, Schwab H, Stanisich V A, Thomas C M. Complete nucleotide sequence of Birmingham IncPα plasmids. Compilation and comparative analysis. J Mol Biol. 1994;239:623–663. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pansegrau W, Ziegelin G, Lanka E. The origin of conjugative IncP plasmid transfer: interaction with plasmid-encoded products and the nucleotide sequence of the relaxation site. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;951:365–374. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(88)90108-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rees C E D, Bradley D E, Wilkins B M. Organization and regulation of the conjugation genes of IncI1 plasmid ColIb-P9. Plasmid. 1987;18:223–236. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(87)90065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rees C E D, Wilkins B M. Protein transfer into the recipient cell during bacterial conjugation: studies with F and RP4. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1199–1205. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salmond G P C. Secretion of extracellular virulence factors by plant pathogenic bacteria. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1994;32:181–200. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schiestl R H, Petes T D. Integration of DNA fragments by illegitimate recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7585–7589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Segal G, Purcell M, Shuman H A. Host cell killing and bacterial conjugation require overlapping sets of genes within a 22-kb region of the Legionella pneumophila genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1669–1674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simon J R, Moore P D. Homologous recombination between single-stranded DNA and chromosomal genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:2329–2334. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.7.2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Singer R A, Johnston G C. Nalidixic acid causes a transient G1 arrest in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet. 1979;176:37–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00334293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith M W, Feng D-F, Doolittle R F. Evolution by acquisition: the case for horizontal gene transfers. Trends Biochem Sci. 1992;17:489–493. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54a.Thomas, A. T., and B. M. Wilkins. Unpublished data.

- 55.Thompson T L, Centola M B, Deonier R C. Location of the nick at oriT of the F plasmid. J Mol Biol. 1989;207:505–512. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90460-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vogel J P, Andrews H L, Wong S K, Isberg R R. Conjugative transfer by the virulence system of Legionella pneumophila. Science. 1998;279:873–876. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5352.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weiss A A, Johnson F D, Burns D L. Molecular characterization of an operon required for pertussis toxin secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2970–2974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilkins B M. Gene transfer by bacterial conjugation: diversity of systems and functional specializations. In: Baumberg S, Young J P W, Wellington E M H, Saunders J R, editors. Population genetics of bacteria. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1995. pp. 59–88. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wilkins B M, Lanka E. DNA processing and replication during plasmid transfer between Gram-negative bacteria. In: Clewell D B, editor. Bacterial conjugation. New York, N.Y: Plenum Publishing Corp.; 1993. pp. 105–136. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Willetts N, Crowther C. Mobilization of the non-conjugative IncQ plasmid RSF1010. Genet Res. 1981;37:311–316. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300020310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Winans S C, Burns D L, Christie P J. Adaptation of a conjugal transfer system for the export of pathogenic macromolecules. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:64–68. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(96)81513-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]