Abstract

Decades of inquiry on intimate partner violence show consistent results: violence is woefully common and psychologically and economically costly. Policy to prevent and effectively intervene upon such violence hinges upon comprehensive understanding of this phenomenon at a population level. The current study prospectively estimates the cumulative incidence of sexual and physical dating violence (DV) victimization/perpetration over a 12-year timeframe (2010–2021) using diverse participants assessed annually from age 15 to 26. Data are from Waves 1–13 of an ongoing longitudinal study. Since 2010 (except for 2018 and 2019), participants were assessed on past-year physical and sexual DV victimization and perpetration. Participants (n = 1,042; 56% female; Mage baseline = 15) were originally recruited from seven public high schools in southeast Texas. The sample consisted of Black/African American (30%), White (31%), Hispanic (31%), and Mixed/Other (8%) participants. Across 12 years of data collection, 27.3% experienced sexual DV victimization and 46.1% had experienced physical DV victimization by age 26. Further, 14.8% had perpetrated at least one act of sexual DV and 39.0% had perpetrated at least one act of physical DV against a partner by this age. A 12-year cumulative assessment of physical and sexual DV rendered prevalence estimates of both victimization and perpetration that exceeded commonly and consistently reported rates in the field, especially on studies that relied on lifetime or one-time specified retrospective reporting periods. These data suggest community youth are at continued and sustained risk for DV onset across the transition into emerging adulthood, necessitating early adolescent prevention and intervention efforts that endure through late adolescence, emerging adulthood, and beyond. From a research perspective, our findings point to the need for assessing DV on a repeated basis over multiple timepoints to better guage the full extent of this continued public health crisis.

Keywords: partner violence, incidence, emerging adulthood, teen dating violence, prevention

Physical and sexual dating violence (DV) is a pressing public health and safety concern among adolescents and emerging adults (Smith et al., 2018). DV encompasses a host of abusive interpersonal behaviors and is often defined by physically and sexually violent behaviors such as hitting, shoving, and sexually assaulting a partner. Estimates from the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey indicate that 36% and 34% of adult women and men, respectively, are victims of intimate partner sexual violence, physical violence, and/or stalking in their lifetime (Smith et al., 2018). Beyond potential physical harm and injury, physical, psychological, and sexual DV victimization and perpetration are consistently associated with an array of adverse physical and mental health outcomes, including psychopathology, substance misuse, risk for future victimization, and chronic health consequences across the lifespan (Exner-Cortens et al., 2013; Jouriles et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2018). Moreover, partner violence is costly to Americans, with one estimate putting the population economic burden at $3.6 trillion over victims’ lifetimes (Peterson et al., 2018).

Rates of DV Perpetration and Victimization

Given its impact, DV prevention among adolescents and emerging adults has become a national public health and policy priority (e.g., American Psychological Association Resolution, 2019; ongressional Research Services, 2023; Williams et al., 2020). In efforts to better define and monitor DV, the public health model of violence prevention (Mercy et al., 1993) attempts to accurately estimate the prevalence and incidence of DV to understand the development of such violent behaviors, including risk and protective factors. Adolescents and emerging adults are at the highest risk for first incidents of DV victimization. Over 71% of victimized women and 55% of victimized men first experienced sexual or physical IPV before age 25 (Smith et al., 2018). Meta-analytic results of racially and ethnically diverse samples suggest that approximately 20% of teens experience physical DV and 9% experience sexual DV (Wincentak et al., 2017). This rate is consistent with US trends over a 12-year timeframe from 1999 to 2011, in which approximately 9% of adolescents reported experiencing past-year physical DV at each timepoint (Rothman & Xuan, 2014). DV perpetration and victimization peak during the transition from adolescence to emerging adulthood (Johnson et al., 2015; Shorey et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2018) clustering with other risk behaviors across adolescence (McNaughton Reyes et al., 2020; Orpinas et al., 2017). While the risk for DV victimization and perpetration in both adolescence and emerging adulthood has been well studied, the research has primarily been siloed, looking only at adolescents or emerging adults, which limits our understanding of the continumum of development in these critical periods. With respect to the link between dating violence and race and ethnicity, research has been largely inconsistent; however, accumululating studies show hightened rates of victimization for Black and Hispanic youth (Boothe et al., 2014). To be clear, being Black or Hispanic is not a risk factor for DV. Instead, it is the systemic and everyday racism and discrimination that people of color experience that may increase the likelihood of DV victimization and perpetration (Caldwell et al., 2004; Clark et al., 2004).

Assessing DV Prevalence

It is essential that we establish accurate and comprehensive estimates of DV during the critical development transition from adolescence into adulthood. Over the last several decades, researchers have sought to refine the measurement of DV, addressing concerns about context, intent, and gender parity (Follingstad & Bush, 2014; Hamby, 2016a, 2016b; Rothman, Cuevas, Mumford et al., 2022). Despite this work, few innovations have occurred in understanding population-level incidence of these data, especially as it relates to approaches to robustly establishing prevalence and onset. Extant literature on DV prevalence and incidence largely relies on estimates of DV victimization and perpetration assessed using lifetime or one-time specified retrospective reporting periods (e.g., within current relationship; within past 1–12 months) (Bonomi et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2018; Vagi et al., 2015; Ybarra et al., 2016). These approaches risk underreporting of DV due to respondents forgetting or misremembering events (i.e., when asking about lifetime) or limiting their recall to short spans of time or limited partners. Alternatively, cumulative assessment approaches aggregate repeated measurements across (often shorter) reference periods rather than rely on a single-point retrospective report (Caiozzo et al., 2016; Jouriles et al., 2005; Krauss et al., 2020). Since it is likely that reference period influences prevalence rates, a cumulative approach can mitigate some measurement error by capturing violence “missed” by lifetime lookbacks. Past use of cumulative assessment strategies resulted in higher prevalence rates of DV among adolescents and, importantly, improved criterion validity with psychological correlates (Jouriles et al., 2005; Krauss et al., 2020). Thus, cumulative assessment functions as a valid and potentially more accurate assessment of DV involvement than previously documented, making the onset of certain behaviors more identifiable and thus refining prevention approaches

Current Study

Cumulative violence estimates have yet to be applied across the developmental transition from adolescence into emerging adulthood, or beyond aggregated periods of 3 months. The objective of this study is to prospectively estimate the cumulative incidence of sexual and physical DV victimization and perpetration over a 12-year timeframe using community participants from diverse ethnic/racial and socioeconomic backgrounds assessed annually from age 15 to age 26 (2010–2021), spanning the transition from adolescence to emerging adulthood.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Participants (N = 1,042) were drawn from on ongoing longitudinal study, Dating it Safe (Blinded for Review). Participants were initially recruited from ninth and tenth grade high school classes across seven campuses in five school districts of southeast Texas. The sample (56% female) is 30% Black, 31% White, 31% Hispanic, and 8% Other. Average age at baseline assessment was 15. Recruitment concluded in Spring 2010, with the aim of enrolling students from urban, rural, and suburban schools (62% response rate). Schools were recruited based on their representative make-up of ethnically diverse and low-income students. Every school district/high school approached agreed to participate in the study. Recruitment occurred during school hours in courses with mandated attendance to ensure a representative sample of adolescents at each school. All students were eligible to participate. Active and written parental consent was obtained at baseline. Participant assent was obtained at each wave and consent obtained when participants reached the age of majority.

The cohort has been assessed annually (except for 2018 and 2019, in which the authors lacked funding) and is ongoing. All procedures were approved by the first author’s Institutional Review Board. At the most recent completed data collection wave (2021), 21% of the sample were married, 35% had children, and 18% identified as a sexual minority. All original cohort participants, provided they have not already declined to participate (n = 67) or passed away (n = 3), are eligible to participate at every wave and attempts are made to collect data regardless of prior pattern of missing data. Data were collected via paper/pencil while participants were in high school and via a web-based service through email and text contact after graduating or dropping out of high school. Attrition analyses comparing Wave 1 to Wave 10 revealed little to no differences in demographic and main study variables, including all forms of DV perpetration and victimization.

Measures

Physical and sexual DV perpetration and DV victimization were assessed using physical (8 items) and sexual (6 items) abuse subscales of the Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory (CADRI) (see Table 1; Wolfe et al., 2001). As we have previously shown with this sample, the CADRI is a suitable behaviorally specific approach for measuring multiple types of DV over time across sex and race/ethnicity (Shorey et al., 2019). Participants indicated whether each act occurred (yes/no) during a conflict or argument with a current or former dating/marital partner during the past 12 months. Questions are asked twice—first in relation to perpetration, and then in relation to victimization. At each wave, a participant was coded as “yes” to victimization/perpetration for each subscale (sexual, physical) if they endorsed any of the items. At the initial assessment (Mage = 15) students were asked to recall lifetime experiences. All subsequent assessments were based on a 12-month timeframe. Baseline prevalence was estimated using the initial participant assessment.

Table 1.

Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory (Wolfe et al., 2001).

| Construct | Items |

|---|---|

| Sexual DV victimization | He/She touched me sexually when I didn’t want him/her to. |

| He/She forced me to have sex when I didn’t want to. | |

| He/She threatened me in an attempt to have sex with me. | |

| Sexual DV perpetration | I touched him/her sexually when he/she didn’t want me to. |

| I forced him/her to have sex when he/she didn’t want to. | |

| I threatened him/her in an attempt to have sex with him/her. | |

| Physical DV victimization | He/she threw something at me. |

| He/she kicked, hit, or punched me. | |

| He/she slapped me or pulled my hair. | |

| He/she pushed, shoved, or shook me. | |

| Physical DV perpetration | I threw something at him/her. |

| I kicked, hit, or punched him/her. | |

| I slapped him/her or pulled his/her hair. | |

| I pushed, shoved, or shook him/her. |

Note. Recall period for measure is last 12 months. Response options for each item were Yes/No. DV = Dating Violence.

Data Analysis

A cumulative estimate of DV victimization/perpetration across subsequent follow-ups was estimated by selecting a subsample of participants for each of the four outcomes selected on those reporting no behavior at baseline. Each subsample was then followed prospectively to assess subsequent experiences with DV. Starting with the first 12-month incidence estimate, for each follow-up, if a participant indicated victimization/perpetration their value was recoded to “yes.” This was done for each subsequent wave, which provided a cumulative estimate of victimization/perpetration across the follow-up period. If a participant was missing a follow-up observation, we conservatively assumed no victimization/perpetration during that 12-month interval. Rates were estimated both overall and stratified by sex.

Results

As shown in Table 2, subsamples of DV were similar across sex and race/ethnicity; however, the physical DV perpetration subgroup was composed of fewer females and slightly more White participants than the other subgroups.

Table 2.

Sample Demographics.

| Variable | Overall Sample | Sexual DV Victimization | Sexual DV Perpetration | Physical DV Victimization | Physical DV Perpetration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1,042 | n = 832 | n = 890 | n = 711 | n = 713 | |

| Female No (%) | 583 (56.0) | 447 (53.7) | 500 (56.2) | 409 (57.5) | 360 (50.5) |

| Race/Ethnicity No (%) | |||||

| Hispanic | 327 (31.4) | 267 (32.1) | 283 (31.8) | 227 (31.9) | 232 (32.5) |

| White | 306 (29.2) | 250 (30.0) | 268 (30.1) | 219 (30.8) | 236 (33.1) |

| Black | 291 (27.9) | 231 (27.8) | 249 (28.0) | 191 (26.9) | 171 (24.1) |

| Multi/Other | 118 (11.3) | 84 (10.1) | 90 (10.1) | 74 (10.4) | 74 (10.4) |

Note. DV = Dating Violence.

The baseline lifetime prevalence and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for DV victimization and perpetration are presented in Table 3. For sexual DV victimization, the prevalence was 9.1% with females having significantly higher sexual DV victimization than males (12.5% vs. 4.7%, p < .001). The prevalence of sexual DV perpetration was 3.1% of the sample and did not significantly differ by sex. Baseline prevalence of physical DV victimization was 21.8% with males reporting higher levels of victimization than females (24.3% vs. 19.8%, p = .05). Physical DV perpetration at baseline was 21.7% and was significantly higher for females than males (29.4% vs. 12.0%, p < .001, respectively).

Table 3.

Baseline Prevalence of Dating Violence Victimization and Perpetration (Age 15).

| Dating Violence (DV) | n | n (%) | 95% CI | Sex T-Test p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual DV victimization Victimization | 915 | 83 (9.1) | (7.3, 11.1) | <.001 |

| Males | 404 | 19 (4.7) | (3.0, 7.1) | |

| Females | 511 | 64 (12.5) | (9.9, 15.6) | |

| Sexual DV perpetration | 918 | 28 (3.1) | (2.1, 4.3) | .32 |

| Males | 405 | 15 (3.7) | (2.2, 5.9) | |

| Females | 513 | 13 (2.5) | (1.4, 4.2) | |

| Physical DV victimization | 909 | 198 (21.8) | (19.2, 24.6) | .05 |

| Males | 399 | 97 (24.3) | (20.3, 28.7) | |

| Females | 510 | 101 (19.8) | (16.5, 23.4) | |

| Physical DV perpetration | 911 | 198 (21.7) | (19.1, 24.5) | <.001 |

| Males | 401 | 48 (12.0) | (9.1, 15.4) | |

| Females | 510 | 150 (29.4) | (25.6, 33.5) |

Note. Sample size denotes those with valid response to all scale items. Bold = Sample level.

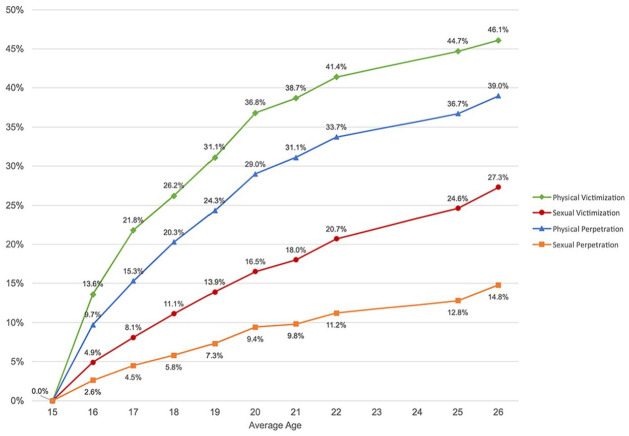

The cumulative incidence rates of sexual and physical DV perpetration and victimization post-baseline are presented in Table 4 for each of the four subgroups, including sexual DV victimization (n = 832), sexual DV perpetration (n = 890), physical DV perpetration (n = 711) and physical DV victimization (n = 713). New incidence of sexual DV victimization over the first consecutively assessed 7 years of follow-up was 20.7% (Mage = 22) and increased to 27.3% at the most recent follow-up (Mage = 26). Incidence of sexual DV perpetration over that same period was 11.2% (Mage = 22) and 14.8% (Mage = 26), respectively. The 7-year cumulative incidence of physical DV victimization was 41.1% (Mage = 22) increasing to 46.1% at the most recent follow-up (Mage = 26). Physical DV victimization had a 7 year cumulative incidence of 33.7% (Mage = 22), which increased to 39.0% at the most recent follow-up (Mage = 26). As shown in Figure 1, new incidences of DV victimization and perpetration appear to peak at around age 20.

Table 4.

Cumulative Incidence of Dating Violence Victimization and Perpetration.

| Year | Age | Sex | Sexual DV Victimization (M = 385, F = 447) | Sexual DV Perpetration (M = 390, F = 500) | Physical DV Victimization (M = 302, F = 409) | Physical DV Perpetration (M = 353, F = 360) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | [95% CI] | n (%) | [95% CI] | n (%) | [95% CI] | n (%) | 95% CI | |||

| 2010 | 15 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||||

| 2011 | 16 | Male | 11 (2.9) | [1.5, 3.1] | 9 (2.3) | [1.1, 4.2] | 38 (12.6) | [9.2, 16.7] | 18 (5.1) | (3.2, 7.8) |

| Female | 30 (6.7) | [4.7, 9.3] | 14 (2.8) | [1.6, 4.5] | 59 (14.4) | [11.3, 18.1] | 51 (14.2) | (10.9, 18.1) | ||

| Total | 41 (4.9) | [3.6, 6.6] | 23 (2.6) | [1.7, 3.8] | 97 (13.6) | [11.3, 16.3] | 69 (9.7) | (7.7, 12.0) | ||

| 2012 | 17 | Male | 19 (4.9) | [3.1, 7.4] | 16 (4.1) | [2.5, 6.4] | 61(20.2) | [16.0, 25.0] | 27 (7.6) | (5.2, 10.8) |

| Female | 48 (10.7) | [8.1, 13.9] | 24 (4.8) | [3.2, 6.9] | 94 (23.0) | [19.1, 27.1] | 82 (22.8) | (18.7, 27.3) | ||

| Total | 67 (8.1) | [6.3, 10.0] | 40 (4.5) | [3.3, 6.0] | 155 (21.8) | [18.9, 24.9] | 109 (15.3) | (12.8, 18.1) | ||

| 2013 | 18 | Male | 27 (7.0) | [4.8, 9.9] | 21 (5.4) | [3.5, 8.0] | 77 (25.5) | [20.8, 30.6] | 39 (11.0) | (8.1, 14.6) |

| Female | 65 (14.5) | [11.5, 18.0] | 31 (6.2) | [4.3, 8.6] | 109 (26.7) | [22.5, 31.1] | 106 (29.4) | (24.9, 34.3) | ||

| Total | 92 (11.1) | [9.1, 13.3] | 52 (5.8) | [4.4, 7.5] | 186 (26.2) | [23.0, 29.5] | 145 (20.3) | (17.5, 23.4) | ||

| 2014 | 19 | Male | 35 (9.1) | [6.5, 12.3] | 28 (7.2) | [4.9, 10.1] | 94 (31.1) | [26.1, 36.5] | 46 (13.0) | (9.8, 16.8) |

| Female | 81 (18.1) | [14.8, 21.9] | 37 (7.4) | [5.3, 9.9] | 127 (31.1) | [26.7, 35.7] | 127 (35.3) | (30.5, 40.3) | ||

| Total | 116 (13.9) | [11.7, 16.4] | 65 (7.3) | [5.7, 9.2] | 221 (31.1) | [27.8, 34.6] | 173 (24.3) | (12.2, 27.5) | ||

| 2015 | 20 | Male | 45 (11.7) | [8.8, 15.2] | 41 (10.5) | [7.8, 13.8] | 112 (37.1) | [31.8, 42.6] | 61(17.3) | (13.6, 21.5) |

| Female | 92 (20.6) | [17.0, 24.5] | 43 (8.6) | [6.4, 11.3] | 150 (36.7) | [32.1, 41.4] | 146 (40.6) | (35.6, 45.7) | ||

| Total | 137 (16.5) | [14.1, 19.1] | 84 (9.4) | [7.6, 11.5] | 262 (36.8) | [33.4, 40.4] | 207 (29.0) | (25.8, 32.4) | ||

| 2016 | 21 | Male | 51 (13.2) | [10.1, 16.9] | 43 (11.0) | [8.2, 14.4] | 114 (37.7) | [32.4, 43.3] | 66 (18.7) | (14.9, 23.0) |

| Female | 99 (22.1) | [18.5, 26.2] | 44 (8.8) | [6.6, 11.5] | 161 (39.4) | [34.7, 44.2] | 156 (43.3) | (38.3, 48.5) | ||

| Total | 150 (18.0) | [15.6, 20.1] | 87 (9.8) | [8.0, 11.9] | 275 (38.7) | [35.2, 42.3] | 222 (31.1) | (27.8, 34.6) | ||

| 2017 | 22 | Male | 58 (15.1) | [11.8, 18.9] | 49 (12.6) | [9.6, 16.1] | 118 (39.1) | [33.7, 44.7] | 71 (20.0) | (16.2, 24.5) |

| Female | 114 (25.5) | [21.6, 29.7] | 51 (10.2) | [7.8, 13.1] | 176 (43.0) | [38.3, 47.9] | 169 (46.9) | (41.8, 52.1) | ||

| Total | 172 (20.7) | [18.0, 23.5] | 100 (11.2) | [9.3, 13.4] | 294 (41.4) | [37.8, 45.0] | 240 (33.7) | (30.3, 37.2) | ||

| 2018 | 23 | |||||||||

| 2019 | 24 | |||||||||

| 2020 | 25 | Male | 68 (17.7) | [14.1, 21.7] | 53 (13.6) | [10.5, 17.3] | 127 (42.1) | [36.6, 47.7] | 78 (22.1) | (18.0, 26.6) |

| Female | 137 (30.6) | [26.5, 35.0] | 61 (12.2) | [9.6, 15.3] | 191 (46.7) | [41.9, 51.5] | 184 (51.1) | (46.0, 56.2) | ||

| Total | 205 (24.6) | [21.8, 27.7] | 114 (12.8) | [10.7, 15.1] | 318 (44.7) | [41.1, 48.4] | 262 (36.7) | (33.3, 40.3) | ||

| 2021 | 26 | Male | 76 (19.7) | [16.0, 23.9] | 64 (16.4) | [13.0, 20.3] | 131 (43.4) | [37.9, 49.0] | 86 (24.2) | (20.1, 29.0) |

| Female | 151 (33.8) | [29.5, 38.3] | 68 (13.6) | [10.8, 16.8] | 197 (48.2) | [43.3, 53.0] | 192 (53.3) | (48.2, 58.4) | ||

| Total | 227 (27.3) | [24.3, 30.4] | 132 (14.8) | [12.6, 17.3] | 328 (46.1) | [42.5, 49.8] | 278 (39.0) | (35.5, 42.6) | ||

Note. M = male, F = female; Study paused in 2018 and 2019 due to lack of funding. DV = Dating Violence

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of DV age 15 to 26 among those with no prior experience.

Note. DV = Dating Violence.

Cumulative incidence rates by sex are also provided in Table 4 and indicate that at the most recent year of data collection (2021), just under half of males (43.4%) and females (48.2%) have been a victim of physical DV by the time they were, on average, 26 years old. Further, 24.2% of males and 53.3% of females have perpetrated at least one act of physical DV against a partner by this age. With respect to sexual DV, 19.7% of males and 33.8% of females have been victims by age 26, while 16.4% of males and 13.9% of females reported perpetration. Notably, participants endorsed items within these scales equally; in other words, a single item was not driving these cumulative rates.

Discussion

Using data from one of the longest longitudinal studies to annually assess the cumulative incidence of physical and sexual DV victimization and perpetration, results reveal alarmingly high rates: by age 26, over a quarter of participants had been victims of sexual DV and nearly half had been victims of physical DV. Similarly, 15% and 39% had reported perpetrating sexual and physical DV against a dating partner, respectively. Notably, these numbers are underestimates as we did not capture revictimization rates. Given the plethora of research detailing the negative mental, physical, and social consequences of experiencing DV (Exner-Cortens et al., 2013; Haynie et al., 2013; Jouriles et al., 2017; Orpinas et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2018), including risk for future partner violence, these numbers are concerning. That the rates are higher than estimates gleaned from cross-sectional (Haynie et al., 2013; Jouriles et al., 2022; Vagi et al., 2015), retrospective (Bonomi et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2018), and longitudinal studies that only consider one (Ybarra et al., 2016) or a few time-points suggest that partner violence may be even more prevalent than previously reported. Further, in using a cumulative incidence approach, we found higher rates of DV than even outlier (cross-sectional) studies using high-risk samples (Alleyne-Green et al., 2012; Martin-Storey, 2015) and comprehensive measures (Niolon et al., 2015). This pattern of results align with estimates derived from similar cumulative assessments over shorter timespans (Jouriles et al., 2005; Krauss et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2003). Importantly, rates exceeded the field’s consensus on the prevalence for both sexual and physical DV in just three aggregated follow-ups, suggesting that future longitudinal research need not expend extensive resources to capture these numbers. The current study contributes to our understanding of assessing DV among adolescents and emerging adults, supporting the use of repeated assessments to accurately obtain prevalence of DV, in part by mitigating the risk of participants forgetting or misremembering events that happened in the distant past.

Our findings also indicate that DV impacts diverse populations and both sexes. While we found no significant impacts by race or ethnicity, there were some differences by sex. By age 26, women report slightly higher levels of physical dating violence victimization and significantly higher rates of physical DV perpetration, as well as sexual DV victimization. That women reported perpetrating more physical DV across adolescence and emerging adulthood is consistent with other research (Niolon et al., 2015; Ontiveros et al., 2020; Straus et al., 1996; Ybarra et al., 2016). This may partly be a result of measurement approaches that are overly simplistic or lack contextualization about self-defense and “horseplay” (Hamby, 2016a, 2016b). Further, as articulated first by Johnson (2006), couples use violence in different ways, not all of which involve power and control. Measurement approaches used for DV among adolescents and emerging adults may differ in their attention to criterion validity, including the ability to predict future DV and past behaviors. Previous research has indicated that males tend to underreport and females over report their behaviors (Ackerman, 2018). Established research also indicates that women sustain more severe and injurious forms of violence than men (Archer, 2000), including sexual assault (Hamby, 2017; Hamby & Turner, 2013; Vagi et al., 2015) and homicide (Messing et al., 2021) from an intimate partner. Sex-related measurement differences for DV merit further examination and testing approaches, especially periods of developmental transition. Nevertheless, these findings emphasize the importance of DV prevention programs addressing all individuals.

Practice and Policy Implications

DV prevention should continue to be a national priority. These results underscore the scope of DV as it impacts adolescents and emerging adults. Thus, governmental funding mechanisms must increase and continue to support research and practice efforts in DV prevention, detection, and intervention. Earmarking funds for clinical science trainees, program delivery grants, and well-designed intervention trials is a worthy funding priority to produce and sustain mental health providers and researchers working with DV. Prevention work is needed across developmental spans, with adaptations made for the unique context of adolescents, including an emphasis on social networks, as well as sexual and relationship development. Primary prevention efforts should start early. At baseline, 4.9% and 13.9% of participants had already experienced sexual and physical DV, respectively. These data, coupled with other studies (Johnson et al., 2015; Shorey et al., 2017), indicate the importance of implementing effective prevention efforts early (e.g., middle school). In a cluster randomized controlled trial, we found that students in 7th grade who received a healthy relationships curriculum were less likely to perpetrate DV a year later, relative to their peers who received a standard health curriculum (Temple et al., 2021). Similarly, middle school students participating in Dating Matters exhibited significantly less physical DV perpetration and victimization over time, relative to standard of care students (Niolon et al., 2019), and a coach-delivered intervention for middle school males reduced physical and sexual DV perpetration among dating youth over a 1-year follow-up, compared to a no-treatment control group (Miller et al., 2020). Further, 6th grade students who received a classroom-computer hybrid DV program reported less DV perpetration and some specific types of DV victimization at the 1-year follow-up (Peskin et al., 2019). Thus, guided by dissemination and implementation science, these and other efficacious programs should be standard middle school curricula nationwide.

Findings also indicate the need for routine DV screening, universal education, and referral for support during adolescence and emerging adulthood. Youth and emerging adults should be regularly screened and provided universal education for potential DV involvement across healthcare, employment, extracurricular, and academic settings. This recommendation is widely supported in the literature, yet practical barriers to implementing wide-spread, universal screening present challenges (Rothman, Cuevas, Mumford et al., 2022; Rothman, Campbell & Hoch, 2022). Notably, presence of an internalizing or externalizing disorder is associated with subsequent involvement in physical DV victimization and perpetration before the age of 21 (McCauley et al., 2015). Thus, screening for DV among youth seeking psychological treatment and youth with childhood exposure to DV is especially encouraged. Given the risk for DV in emerging adulthood, college campuses, along with campus climate assessments, should routinely assess for DV in campus health care and provide supportive services (Krause et al., 2019).

Finally, primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention must be ongoing. These data also demonstrate that prevention efforts must extend throughout adolescence and into emerging adulthood. Indeed, one contribution of our study is that we observed steady development of risk for DV victimization and perpetration into emerging adulthood, with many participants’ first violent relationship not materializing until they were 21 or older (n = 66 new cases of physical DV victimization and n = 71 new cases of physical DV perpetration). Still, and consistent with the limited longitudinal research (Johnson et al., 2015), rates of violence, including new incidences of DV, appeared to peak at age 20. Risk windows for physical and sexual DV appear during adolescence (as teenagers begin dating and experimenting with risky behaviors) and the transition to emerging adulthood (as individuals enter college or the workforce and their intimate relationships intensify). Current results suggest the importance of providing all forms of DV prevention throughout this timeframe. Further, given the rate of new instances of DV, comprehensive primary prevention should not be limited to middle or high school—our findings indicate new incidences of victimization and perpetration peaking at age 20, indicating prevention should extend post-high school and engage emerging adults. We must address the impact of victimization and perpetration to prevent revictimization of DV. Secondary and tertiary prevention approaches, including advocacy, counseling, and economic support, are critical to preventing DV from reoccurring and mitigating negative health impacts (Ogbe et al., 2020).

Limitations

While our study had several strengths, including annual assessments over many years, solid retention, comprehensive DV measures, and a large contemporary and ethnically diverse sample, there were also limitations. Our DV measure is intended for adolescents and emerging adults and did not include more severe forms of DV typically assessed on other DV measures such as the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS; Smith et al., 2018), Measure of Adolescent Relationship Harassment and Abuse (MARSHA; Rothman, Cuevas, Mumford et al., 2022), and the revised Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus et al., 1996) (e.g., strangulation, coercive control, use of weapons, burning) nor does it attend to context like the Partner Violence Scale or the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Hamby, 2016a, 2016b). By not including these latter items, we missed an opportunity to determine if severity of violence (as opposed to relying on acts of violence) differs by sex, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Future research examining DV into emerging adulthood should capture a broader range of physical DV tactics, as well as coercive control, economic, and emotional violence, and the impact of DV tactics. Another limitation, inherent in much of the DV literature, is how participants defined “romantic partner” over the years. It is likely that some participants characterized this as someone they dated once or twice while others considered romantic partners to be a boyfriend, girlfriend, or spouse (Collins et al., 2009).

As can be expected, there was not follow-up data for every participant at every point in time. The cumulative incidence coding scheme started with the first follow-up observation and only updated that response to change from a “no victimization/perpetration” to a “yes” at subsequent measures when data was available. For any wave that a subject was missing follow-up observation their cumulative value was carried forward to the next timepoint. Therefore, a missing observation would be a missed opportunity to convert from “no victimization/perpetration” to “yes,” which likely resulted in a slight downward bias of cumulative incidence and an underestimate of the actual value.

Due to funding constraints, we did not have data for two successive years, which likely resulted in lower rates of DV. The use of self-reports may have introduced reporting biases such as social desirability, especially in the assessment of DV perpetration (Sugarman & Hotaling, 1997). However, previous studies examining problem behaviors in this age group, including DV, support the validity of self-report measures (Wolfe & Mash, 2006). Further, stringent efforts were made to encourage honest reporting with assurances of confidentiality, including a federal certificate of confidentiality, use of participant identification numbers, and a message that information participants provide is kept private.

Conclusions

Despite peaking in the early 20s, risk of victimization and perpetration onset does not appear to completely wane with age, as might be expected. Emerging adults do not developmentally “grow out” of risk with improving executive functioning or as they become more experienced with relationships and more risk averse. Given the sheer volume of potential victims and perpetrators across any given population (e.g., student, patient, employee), we must screen for DV early, often, and in multiple settings. These findings underscore the urgent need for comprehensive and accessible services to help address the impacts of DV among victims, and the crucial need to build a more robust network of approaches to interrupt DV perpetration behaviors. Further, we must do a better job of disseminating effective and universal primary, secondary, and tertiary interventions to prevent the onset and revictimization (and perpetration) of DV. Structural, economic, and practice-oriented changes are needed to address high rates of DV and associated impacts. From a research perspective, our findings point to the need for assessing DV on a repeated basis over multiple timepoints to better gauge the full extent of this continued public health crisis.

Author Biographies

Jeff R Temple, PhD, is the John Sealy Distinguished Chair in Community Health at the University of Texas Medical Branch, as well as a Licensed Psychologist and the Founding Director of the Center for Violence Prevention. His research focuses on the prevention of interpersonal, community, and structural violence, and has been funded through the National Institute of Justice, National Institutes of Health, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Elizabeth Baumler, PhD, is Professor in the School of Nursing and Director of Biostatistics for the Center for Violence Prevention at the University of Texas Medical Branch. Her research areas include youth risk behaviors and intimate partner violence with a focus on the evaluation of intervention effectiveness in school, clinic, and community-based studies as well as the integration of qualitative research to refine and inform complimentary quantitative analyses.

Leila Wood, PhD, MSSW (she/her) is Professor at the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) School of Nursing and Director of Evaluation at the Center for Violence Prevention at UTMB. Dr. Wood’s scholarship focuses on community-based intimate partner violence, dating violence, stalking, and sexual assault prevention and intervention approaches. Dr. Wood is a mixed methods researcher and social work practitioner.

Kelli Franco, PhD, is a pediatric psychologist at The Children’s Hospital of San Antonio and an Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine. She has extensive experience working with vulnerable Texas youth and families. Dr. Franco has collaborated with other mental health professionals to publish research and analysis addressing pediatric trauma, violence prevention, and risky adolescent behavior.

Melissa Peskin, PhD, is Professor of Health Promotion, Behavioral Sciences, and Epidemiology at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health. Her research focuses on the development, implementation, evaluation, and dissemination of adolescent health interventions particularly those related to promoting healthy relationships and reducing violence.

Christie Shumate, MS, is a Research Project Manager in the Center for Violence Prevention and School of Nursing at the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB). She has 20 years of research project management experience ranging from Molecular Biology to Behavioral Health and has helped to collect both quantitative and qualitative data for several projects.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interests with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: All phases of this study were supported by Award Numbers K23HD059916 and R01HD099199 (PI: Temple) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), as well as Award Number 2012-WG-BX-0005 from the National Institute of Justice (NIJ). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NICHD or NIJ.

ORCID iDs: Jeff R. Temple  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3193-0510

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3193-0510

Leila Wood  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5095-2577

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5095-2577

Kelli Sargent Franco  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9316-3797

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9316-3797

References

- Ackerman J. (2018). Assessing conflict tactics scale validity by examining intimate partner violence overreporting. Psychology of Violence, 8(2), 207–217. [Google Scholar]

- Alleyne-Green B., Coleman-Cowger V. H., Henry D. B. (2012). Dating violence perpetration and/or victimization and associated sexual risk behaviors among a sample of inner-city African American and Hispanic adolescent females. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(8), 1457–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association (2019). APA resolution on Campus Sexual Assault. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/about/policy/resolution-campus-sexual-assault.pdf

- Archer J. (2000). Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 126(5), 651–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi A. E., Anderson M. L., Nemeth J., Rivara F. P., Buettner C. (2013). History of dating violence and the association with late adolescent health. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothe M. A. S., Wilson R. M., Lassiter T. E., Holland B. (2014). Differences in sexual behaviors and teen dating violence among Black, Hispanic, and white female adolescents. Journal of Aggression Maltreatment & Trauma, 23, 1072–1089. [Google Scholar]

- Caiozzo C. N., Houston J., Grych J. (2016). Predicting aggression in late adolescent romantic relationships: A short-term longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescence, 53, 237–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell C. H., Kohn-Wood L. P., Schmeelk-Cone K. H., et al. (2004). Racial discrimination and racial identity as risk or protective factors for violent behaviors in African American young adults. American Journal of Community Psychology, 33, 91–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R., Coleman A. P., Novak J. D. (2004). Brief report: Initial psychometric properties of the everyday discrimination scale in black adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 27, 363–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins W. A., Welsh D. P., Furman W. (2009). Adolescent romantic relationships. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 631–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Research Services (CRS) (2023). The 2022 Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) Reauthorization. Retrieved from https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47570/2#:~:text=The%20act%20authorized%20grants%20to,federal%20sex%20offenders%20and%20mandating

- Exner-Cortens D., Eckenrode J., Rothman E. (2013). Longitudinal associations between teen dating violence victimization and adverse health outcomes. Pediatrics, 131(1), 71–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follingstad D. R., Bush H. M. (2014). Measurement of intimate partner violence: A model for developing the gold standard. Psychology of Violence, 4(4), 369. [Google Scholar]

- Hamby S. (2016. a). Advancing survey science for intimate partner violence: The Partner Victimization Scale and other innovations. Psychology of Violence, 6, 352–359. [Google Scholar]

- Hamby S. (2016. b). Self-report measures that do not produce gender parity in intimate partner violence: A multi-study investigation. Psychology of Violence, 6(2), 323–335. 10.1037/a0038207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamby S. (2017). A scientific answer to a scientific question: The gender debate on intimate partner violence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 18(2), 145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamby S., Turner H. (2013). Measuring teen dating violence in males and females: Insights from the national survey of children’s exposure to violence. Psychology of Violence, 3(4), 323. [Google Scholar]

- Haynie D. L., Farhat T., Brooks-Russell A., Wang J., Barbieri B., Iannotti R. J. (2013). Dating violence perpetration and victimization among US adolescents: Prevalence, patterns, and associations with health complaints and substance use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(2), 194–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. P. (2006). Conflict and control: Gender symmetry and asymmetry in domestic violence. Violence Against Women, 12, 1003–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson W. L., Giordano P. C., Manning W. D., Longmore M. A. (2015). The age–IPV curve: Changes in the perpetration of intimate partner violence during adolescence and emerging adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(3), 708–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles E. N., Choi H. J., Rancher C., Temple J. R. (2017). Teen dating violence victimization, trauma symptoms, and revictimization in early adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(1), 115–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles E. N., McDonald R., Garrido E., Rosenfield D., Brown A. S. (2005). Assessing aggression in adolescent romantic relationships: Can we do it better?. Psychological Assessment, 17(4), 469–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles E. N., Nguyen J., Krauss A., Stokes S. L., McDonald R. (2022). Prevalence of sexual victimization among female and male college students: A methodological note with data. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(11–12), NP8767–NP8792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauss A., Jouriles E. N., McDonald R., Rosenfield D. (2020). Measuring teen dating violence perpetration: A comparison of cumulative and single assessment procedures. Psychology of Violence, 10(4), 452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause K. H., Woofter R., Haardörfer R., Windle M., Sales J. M., Yount K. M. (2019). Measuring campus sexual assault and culture: A systematic review of campus climate surveys. Psychology of Violence, 9(6), 611–622. 10.1037/vio0000209 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Storey A. (2015). Prevalence of dating violence among sexual minority youth: Variation across gender, sexual minority identity and gender of sexual partners. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(1), 211–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley H. L., Breslau J. A., Saito N., Miller E. (2015). Psychiatric disorders prior to dating initiation and physical dating violence before age 21: Findings from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(9), 1357–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton Reyes H. L., Foshee V. A., Gottfredson N. C., Ennett S. T., Chen M. S. (2020). Codevelopment of delinquency, alcohol use, and aggression toward peers and dates: Multitrajectory patterns and predictors. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 30(4), 1025–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercy J. A., Rosenberg M. L., Powell K. E., Broome C. V., Roper W. L. (1993). Public health policy for preventing violence. Health Affairs, 12(4), 7–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messing J. T., AbiNader M. A., Pizarro J. M., Campbell J. C., Brown M. L., Pelletier K. R. (2021). The Arizona intimate partner homicide (AzIPH) study: A step toward updating and expanding risk factors for intimate partner homicide. Journal of Family Violence, 36(5), 563–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E., Jones K. A., Ripper L., Paglisotti T., Mulbah P., Abebe K. Z. (2020). An athletic coach–delivered middle school gender violence prevention program: A cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(3), 241–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niolon P. H., Vivolo-Kantor A. M., Latzman N. E., Valle L. A., Kuoh H., Burton T., Taylor B. G., Tharp A. T. (2015). Prevalence of teen dating violence and co-occurring risk factors among middle school youth in high-risk urban communities. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(2), S5–S13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niolon P. H., Vivolo-Kantor A. M., Tracy A. J., Latzman N. E., Little T. D., DeGue S., Lang K. M., Estefan L. F., Ghazarian S. R., McIntosh W. L. K., Taylor B. (2019). An RCT of dating matters: Effects on teen dating violence and relationship behaviors. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 57(1), 13–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogbe E., Harmon S., Van den Bergh R., Degomme O. (2020). A systematic review of intimate partner violence interventions focused on improving social support and/mental health outcomes of survivors. PLoS One, 15(6), e0235177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ontiveros G., Cantos A., Chen P. Y., Charak R., O’Leary K. D. (2020). Is all dating violence equal? Gender and severity differences in predictors of perpetration. Behavioral Sciences, 10(7), 118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orpinas P., Nahapetyan L., Truszczynski N. (2017). Low and increasing trajectories of perpetration of physical dating violence: 7-year associations with suicidal ideation, weapons, and substance use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(5), 970–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peskin M. F., Markham C. M., Shegog R., Baumler E. R., Addy R. C., Temple J. R., Hernandez B., Cuccaro P. M., Thiel M. A., Gabay E. K., Tortolero Emery S. R. (2019). Adolescent dating violence prevention program for early adolescents: The Me & You randomized controlled trial, 2014–2015. American Journal of Public Health, 109(10), 1419–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C., Kearns M. C., McIntosh W. L., Estefan L. F., Nicolaidis C., McCollister K. E., Gordon A., Florence C. (2018). Lifetime economic burden of intimate partner violence among US adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 55(4), 433–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman E. F., Campbell J. K., Hoch A. M., Bair-Merritt M., Cuevas C. A., Taylor B., Mumford E. A. (2022). Validity of a three-item dating abuse victimization screening tool in a 11–21 year old sample. BMC Pediatrics, 22, 337. 10.1186/s12887-022-03397-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman E. F., Cuevas C. A., Mumford E. A., Bahrami E., Taylor B. G. (2022). The psychometric properties of the Measure of Adolescent Relationship Harassment and Abuse (MARSHA) with a nationally representative sample of U.S. youth. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 37(11–12), 17–33. 10.1509/jppm.13.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman E. F., Xuan Z. (2014). Trends in physical dating violence victimization among US high school students, 1999–2011. Journal of School Violence, 13(3), 277–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey R. C., Allan N. P., Cohen J. R., Fite P. J., Stuart G. L., Temple J. R. (2019). Testing the factor structure and measurement invariance of the conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationship Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 31(3), 410–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey R. C., Cohen J. R., Lu Y., Fite P. J., Stuart G. L., Temple J. R. (2017). Age of onset for physical and sexual teen dating violence perpetration: A longitudinal investigation. Preventive Medicine, 105, 275–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P. H., White J. W., Holland L. J. (2003). A longitudinal perspective on dating violence among adolescent and college-age women. American Journal of Public Health, 93(7), 1104–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. G., Zhang X., Basile K. C., Merrick M. T., Wang J., Kresnow M. J., Chen J. (2018). The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey: 2015 data brief–updated release. U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Straus M. A., Hamby S. L., Boney-McCoy S. U. E., Sugarman D. B. (1996). The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2) development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues, 17(3), 283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Sugarman D. B., Hotaling G. T. (1997). Intimate violence and social desirability: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 12(2), 275–290. [Google Scholar]

- Temple J. R., Baumler E., Wood L., Thiel M., Peskin M., Torres E. (2021). A dating violence prevention program for middle school youth: A cluster randomized trial. Pediatrics, 148(5), e2021052880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagi K. J., Olsen E. O. M., Basile K. C., Vivolo-Kantor A. M. (2015). Teen dating violence (physical and sexual) among US high school students: Findings from the 2013 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(5), 474–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams L. M., Pattavina A., Cares A. C., Stein N. D. (2020). Responding to Sexual Assault on Campus: A national assessment and systematic classification of the scope and challenges of investigation and adjudication. Office of Justice Programs. Retrieved from https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/254671.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wincentak K., Connolly J., Card N. (2017). Teen dating violence: A meta-analytic review of prevalence rates. Psychology of Violence, 7(2), 224–241. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe D. A., Mash E. J. (Eds.). (2006). Behavioral and emotional disorders in adolescents: Nature, assessment, and treatment. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe D. A., Scott K., Reitzel-Jaffe D., Wekerle C., Grasley C., Straatman A. L. (2001). Development and validation of the conflict in adolescent dating relationships inventory. Psychological Assessment, 13(2), 277–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ybarra M. L., Espelage D. L., Langhinrichsen-Rohling J., Korchmaros J. D. (2016). Lifetime prevalence rates and overlap of physical, psychological, and sexual dating abuse perpetration and victimization in a national sample of youth. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(5), 1083–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]