Abstract

Background

The HEARTS technical package was developed by the World Health Organization to address the implementation gap in cardiovascular disease prevention in low- and middle-income countries. Guatemala is a middle-income country that is currently implementing HEARTS. National authorities in Guatemala are interested in exploring how hypertension and diabetes management can be integrated in HEARTS implementation. The objective of this study is to conduct a feasibility and acceptability pilot trial of integrated hypertension and diabetes management based on HEARTS in the publicly funded primary care system in Guatemala.

Methods

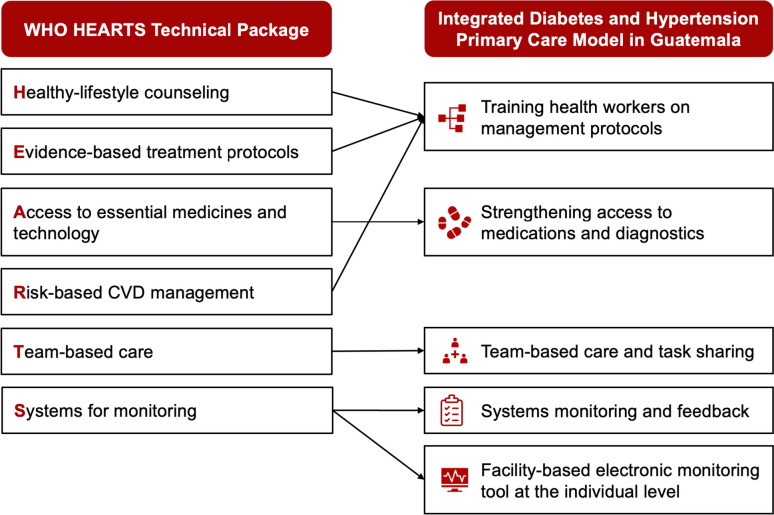

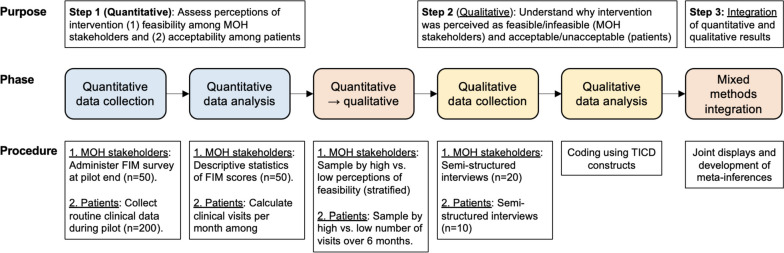

A single-arm pilot trial for 6 months will be carried out in 11 Ministry of Health primary care facilities starting in September 2023. A planned sample of 100 adult patients diagnosed with diabetes (n = 45), hypertension (n = 45), or both (n = 10) will be enrolled. The intervention will consist of HEARTS-aligned components: Training health workers on healthy-lifestyle counseling and evidence-based treatment protocols, strengthening access to medications and diagnostics, training on risk-based cardiovascular disease management, team-based care and task sharing, and systems monitoring and feedback, including implementation of a facility-based electronic monitoring tool at the individual level. Co-primary outcomes of feasibility and acceptability will be assessed using an explanatory sequential mixed-methods design. Secondary outcomes include clinical effectiveness (treatment with medication, glycemic control, and blood pressure control), key implementation outcomes (adoption, fidelity, usability, and sustainability), and patient-reported outcome measures (diabetes distress, disability, and treatment burden). Using an implementation mapping approach, a Technical Advisory Committee will develop implementation strategies for subsequent scale-up planning.

Discussion

This trial will produce evidence on implementing HEARTS-aligned hypertension and diabetes care in the MOH primary care system in Guatemala. Results also will inform future HEARTS projects in Guatemala and other low- and middle-income countries.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT06080451. The trial was prospectively registered on October 12, 2023.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s43058-023-00539-8.

Keywords: Implementation research, Health policy and systems research, Global health, Hypertension, Diabetes, Guatemala, WHO HEARTS technical package

Contributions to the literature.

The World Health Organization developed the HEARTS technical package to improve implementation of evidence-based interventions to prevent cardiovascular disease in primary care facilities in low- and middle-income countries. Most HEARTS implementation projects to date have focused on a single risk factor, hypertension.

This pilot study will investigate how integrated hypertension and diabetes management based on HEARTS can be implemented in the Guatemalan national primary care system.

Implementation strategies will be developed and selected using an implementation mapping approach. These implementation strategies will inform future HEARTS scale-up projects in Guatemala and other low- and middle-income countries.

Background

Approximately, 80% of the global burden of hypertension and diabetes occurs in low- and middle-income countries [1]. Widespread adoption of evidence-based treatment of these conditions in high-income countries contributes to markedly better cardiovascular disease (CVD) outcomes than in low- and middle-income countries, where adoption is often limited [2–4]. To address this implementation gap, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed the HEARTS technical package for CVD Management in Primary Health Care (henceforth, “HEARTS”) [5]. HEARTS is a package of evidence-based interventions that align with the US Kaiser Permanente hypertension program [6] and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) Standardized Hypertension Treatment Project [7, 8]. The package has six multilevel intervention components forming the acronym “HEARTS”: healthy lifestyle counseling, evidence-based protocols, access to medicines, risk-based management, team care and task sharing, and systems monitoring.

HEARTS is intended to improve CVD prevention within national primary care systems by addressing multiple CVD risk factors. To date, however, HEARTS implementation projects have focused on hypertension as it is the highest-burden risk factor [9, 10]. To further its impact, HEARTS can be expanded to integrate management of other CVD risk factors such as diabetes [11]. As the diabetes-specific HEARTS module (HEARTS-D) primarily focuses on clinical diabetes care, there is a need for generalizable evidence on implementing integrated hypertension and diabetes with the HEARTS framework [11].

Guatemala is a middle-income country with the highest burden of cardiometabolic diseases in Central America [12]. An estimated 32.2% [3] and 13.1% [13] of Guatemalan adults have hypertension and diabetes, respectively, and the two conditions account for one-quarter of national deaths [12]. This project builds on prior hypertension control projects in Guatemala by study investigators, local collaborating organizations, and stakeholders in the Ministry of Health (MOH) and PAHO. From 2017 to 2022, study team members implemented a HEARTS-aligned multicomponent, multilevel hypertension project across MOH primary care facilities in 5 of the country’s 22 departments [14]. In 2021, study team members initiated a HEARTS pilot in 6 MOH primary care facilities. Finally, in November 2022, the Guatemalan MOH officially launched HEARTS. While HEARTS in Guatemala initially focuses on hypertension, national authorities are interested to exploring how diabetes can be integrated into ongoing implementation efforts.

The primary objective of this pilot study is to test the feasibility and acceptability of an integrated model of hypertension and diabetes management based on HEARTS in the publicly funded primary care system in Guatemala. Secondary objectives of this study are to rehearse study procedures and to engage with key stakeholders to develop implementation strategies for a subsequent scale-up project.

Methods/design

This protocol follows the SPIRIT guidelines for clinical trial protocols (Additional file 1) [15]. Additional files 2 and 3 include the CONSORT [16] and TIDieR [17] checklists. We also applied, as appropriate, guidance on reporting non-randomized pilot studies, conducting pilot implementation studies, and applying mixed-methods to pilot studies [18–20]. Table 1 defines important concepts as used in this study protocol.

Table 1.

Definitions of important concepts as used in this study protocol

| • The term pilot study is used in this protocol because the study objective is not only to investigate whether HEARTS can be implemented in Guatemala but also to evaluate a smaller-scale version of a future planned scale-up study [21] |

| • The term feasibility can mean different things in pilot studies [22] and in global cardiovascular disease research [23]. In this protocol, we use feasibility to refer to implementation outcomes |

| • The evidence-based intervention (“the thing” [24]) in this study is the HEARTS package of evidence-based interventions. In this protocol, we use the name “Integrated Hypertension and Diabetes Primary Care Model” to refer to this evidence-based intervention as implemented in Guatemala |

| • This study will not evaluate implementation strategies (“the stuff we do to try to help people and places to do ‘the thing’” [24]). However, a key secondary objective of this study is to develop implementation strategies for each intervention component, thus informing a subsequent scale-up study of HEARTS implementation in Guatemala |

Study design

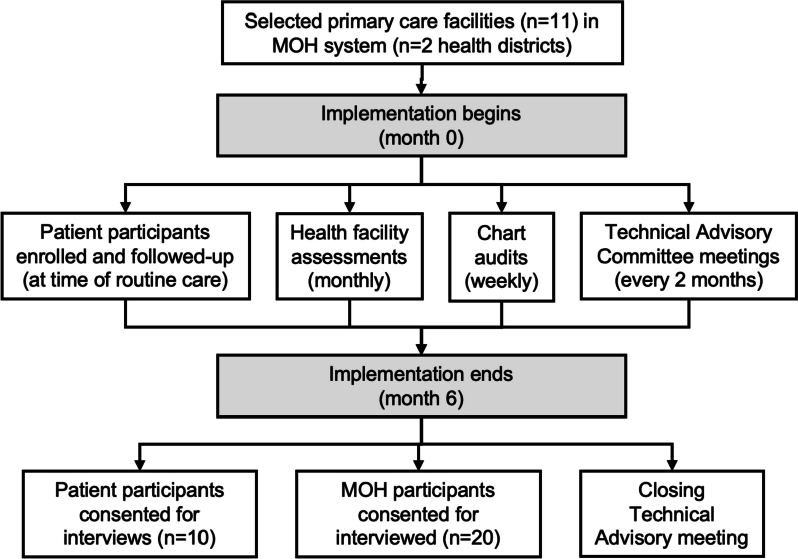

A single-arm pilot trial over 6-month duration will be carried out in starting in September 2023. A single-arm design was chosen as most appropriate to evaluate feasibility and acceptability and to align with recommendations for pilot projects in the HEARTS implementation guide [25].

Study setting

Participating health facilities

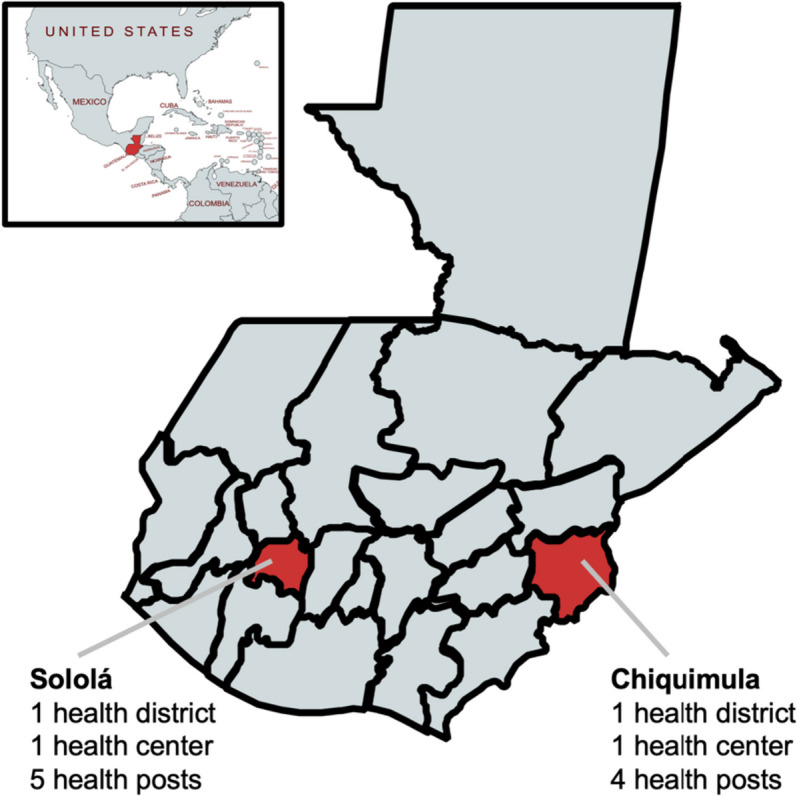

This study will be carried out in 11 MOH primary care facilities in 2 health districts (Fig. 1). The two health districts were selected in consultation with the MOH and PAHO. Each health district includes one second-level primary health facility (health center) and referring first-level primary health facilities (health posts). Both health districts were sites where the study team previously implemented HEARTS-aligned hypertension control projects. The health districts were purposefully selected to represent important areas of diversity in Guatemala across location and ethnicity. Neither health district was part of the initial wave of HEARTS implementation in the MOH. It was also important that each site had motivated MOH leadership [25]. The selected health district in Sololá is in the Central Highlands and has a primarily indigenous Maya population. The selected health district in Chiquimula is in eastern Guatemala and has a primarily non-Indigenous population. Both health districts have poverty rates of 60–70% with large rural populations [26, 27].

Fig. 1.

Map of study setting. The pilot study will be carried out in 11 primary care facilities (either health posts or health centers) in two health districts in the Ministry of Health primary care system in Guatemala. Map inset depicts the location of Guatemala relative to neighboring countries

Study context

Health system structure

Approximately, 75% of the population in Guatemala is uninsured [28]. The majority of uninsured patients with hypertension and diabetes in Guatemala depend on the MOH-led system for health care. The MOH system is a national, publicly funded system consisting of multiple levels [28]. The first two levels are the primary care levels where this project will be conducted (health posts and health centers). Health posts are in rural villages, are typically open during business hours on weekdays, and are staffed by 1–2 auxiliary nurses. Auxiliary nurses are full-time MOH employees and have similar training to nursing assistants in the US healthcare system. Their scope of practice includes a wide range of basic preventative and curative primary care services, but auxiliary nurses typically do not provide pharmacological management of noncommunicable diseases such as diabetes or hypertension. Health centers are in urban or semi-urban areas in midsized towns, are open 24/7 for emergencies, and are staffed by professional nurses, general physicians, physicians in training, or a combination thereof. Health centers manage uncomplicated diabetes or hypertension cases. Available resources typically include oral medications and tools for measuring blood glucose and blood pressure. Patients needing insulin therapy, acute inpatient care, or specialist management of diabetes or hypertension complications are referred from health centers to regional or national hospitals.

Clinical guidelines

The National Program for the Prevention of Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases and Cancer coordinates hypertension and diabetes policies and guidelines in the MOH [29]. The MOH regularly releases clinical guidelines for primary care clinicians in Guatemala. The most recent hypertension and diabetes guidelines, released in 2018, were updated in 2023 [30] and are generally consistent with international guidelines [31]. The main challenge relating to clinical guidelines in Guatemala is the need for investments to support guideline implementation, including staffing, training and supervision, and equipping primary care facilities with clinical resources.

Clinical data systems

At present, there is no standardized paper or electronic patient medical record in the MOH-led health system. As a result, there is difficulty tracking individual patients over time or between health system levels. There is also no official diabetes or hypertension registry. The MOH has an electronic tool, the Health Management Information System, which primarily serves to monitor resource utilization, especially medications dispensed (Sistema de Información Gerencial de Salud [SIGSA]). The SIGSA system is not designed to capture longitudinal patient data, and thus, in practice, clinicians cannot use the system to provide clinical care with information stored during prior clinical visits.

Availability and cost of medications and diagnostics

Guatemalan laws guarantee that health care including medications is free of charge at MOH health facilities [28]. The MOH thus is responsible for ensuring the availability of quality medications and supplies relating to hypertension and diabetes. At the primary care level, the most commonly available medications for hypertension are hydrochlorothiazide, enalapril, and losartan; the most commonly available medications for diabetes are metformin and glimepiride. Tests such as hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), creatinine, or cholesterol are not available at MOH-led primary care facilities, though patients sometimes solicit testing at private laboratory facilities. Stockouts of medications and diagnostics occur [32].

Context of HEARTS implementation in Guatemala

In November 2022, with support from PAHO, the Guatemalan MOH committed to participate in the “Hearts in the Americas” initiative [33]. The MOH plans a stepped implementation of HEARTS across the country. The first 36 health districts across 6 of 22 departments in the country were enrolled in late 2022 and 2023. (“Departments” are first-level political subdivisions analogous to US states.) Neither of the sites in this pilot was included in the initial wave of HEARTS implementation in Guatemala. The MOH has committed resources to HEARTS, including provision of medications and supplies. To date, HEARTS implementation in Guatemala has focused only on hypertension management at MOH health centers. Diabetes management is not currently part of the MOH’s HEARTS implementation plans.

Eligibility criteria

Patient participants

Inclusion criteria

All nonpregnant adults aged ≥ 18 years with diagnoses of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, or both conditions who present for routine care at participating MOH primary health facilities over 6 months will be included (“patient participants”).

Both previously diagnosed and newly diagnosed patients will be eligible. Previously diagnosed patients will be identified by MOH primary care clinicians who take medical histories as part of routine care. Newly diagnosed patients will be identified by MOH primary care clinicians who apply hypertension and diabetes diagnostic criteria from national guidelines [30, 31]. Diabetes diagnostic criteria for newly diagnosed patients will be fasting glucose ≥ 126 md/dl, 2-h postprandial glucose ≥ 200 md/dl, or HbA1c ≥ 6.5%. Hypertension diagnostic criteria for newly diagnosed patients will include systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 80 mmHg; a new hypertension diagnosis must be based on the average of at least two measurements performed on two separate occasions.

Exclusion criteria

Participants with confirmed or suspected type 1 diabetes or who are pregnant will be excluded, as these patients are not managed at MOH health centers or health posts. Participants with a prior history of CVD will not be excluded.

Other participants

All MOH staff (i.e., physicians, nurses, and auxiliary nurses) and stakeholders on the Technical Advisory Committee will be eligible for participation in the implementation assessment of the pilot (“MOH participants”).

Intervention

The intervention piloted in this study (“Integrated Hypertension and Diabetes Primary Care Model” [Modelo Integral de Hipertensión y Diabetes en la Atención Primaria]) consists of five HEARTS-aligned components that together comprise the package of evidence-based interventions that we seek to implement (Table 1 and Fig. 2). These components were selected, adapted, and evaluated in our prior hypertension projects in Guatemala [14, 34–37], but the focus on integrated diabetes and hypertension management is novel in this study (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Intervention components. The intervention piloted in this study (“Integrated Hypertension and Diabetes Primary Care Model” [Modelo Integral de Hipertensión y Diabetes en la Atención Primaria]) consists of five HEARTS-aligned components that together comprise the package of evidence-based interventions implemented in this pilot study

Training health workers on hypertension and diabetes management

This component includes training on healthy-lifestyle counseling, evidence-based treatment protocols, and risk-based CVD management. Training workshops will be conducted for first- and second-level health workers, including auxiliary nurses, professional nurses, and physicians. The goal is to provide instruction in standardized screening, diagnostic, and treatment protocols for hypertension and diabetes in MOH guidelines [30, 31]. Initial workshops will be divided into two blocks, each lasting 2 days, in the first month of the project. Pre- and post-training assessments will be conducted to assess changes in knowledge. A refresher training session will be provided in the fourth month of the project. Training will be delivered in each health district’s office headquarters. The training will adapt a curriculum previously used in the study team’s HEARTS-aligned projects and will be approved by the Department of Health Training and Education (Departamento de Promoción y Educación en Salud [PROEDUSA]), which is the unit in the MOH charged with continuing medical education. Workshop content will include the following topics: an introduction to hypertension and diabetes, diagnostic criteria, use of stepped treatment protocols, treatment goals, medication side effects, counseling to promote lifestyle changes, motivational interviewing, team-based care, capture and use of electronic patient data, and other topics. Participants will have knowledge assessments before and after training workshops. Of note, MOH treatment goals for diabetes are fasting glucose 70–115 mg/dL, postprandial glucose 70–160 mg/dl, or HbA1c < 7.0; MOH treatment goals for hypertension are < 130/80 mm/Hg [31, 38, 39].

Team-based care and task sharing

To implement hypertension and diabetes care in health posts, we will implement a team-based, task-sharing care model between auxiliary nurses staffing health posts and prescribing clinicians (i.e., physicians or professional nurses) at health centers. This intervention component was implemented in the study team’s prior hypertension project and has been approved by the MOH [14]. Physicians or professional nurses will make initial patient treatment plans. Auxiliary nurses working in health posts will implement treatment plans by dispensing medications, monitoring glycemic or blood pressure control, and titrating medications under physician supervision. Care coordination meetings will be held in person or remotely at least once per month to review patient registries and make recommendations for patients whose hypertension or diabetes is not adequately controlled according to MOH guidelines [30, 31]. In our prior projects, monthly meetings have been difficult to operationalise [40]. Therefore, we may suggest an alternative approach in which auxiliary nurses at health posts communicate with physicians at health centers in real time via text messages or phone calls to make treatment changes for uncontrolled patients.

Strengthening access to medications and diagnostics

We have extensive experience collaborating with the MOH to improve medication procurement and logistics at MOH health centers and health posts. In the study team’s hypertension project in five departments, nearly 100% availability of key medications was achieved in MOH facilities over 3 years. In the current project, we will expand the scope to improve access to diagnostics and medications for diabetes at participating MOH primary care facilities. We will coordinate with and train MOH staff on topics that include forecasting demand, seasonal budgeting, storage, shipping, and other topics. Feedback will be provided to MOH staff based on monthly, in-person health facility assessments of medication availability. The focus will be on a small set of MOH-priority medications and diagnostics. Drugs include antihypertensive medications (i.e., hydrochlorothiazide, enalapril, losartan) and oral hypoglycemic agents (i.e., metformin and glimepiride). Of note, single-pill combination medications recommended in HEARTS are not yet available in the MOH system [41]. Diagnostics include blood pressure cuffs and monitors, glucometers, lancets, and glucose strips. As noted in “Study context,” all medications and diagnostics are provided freely to patients in the MOH. The implementation of a facility-based electronic monitoring tool, described below, also functions to improve the availability of medications and diagnostics by providing enhanced data to monitor supply and demand at primary care facilities.

Facility-based electronic monitoring tool at the individual level

The study team previously has collaborated with the MOH to pilot the District Health Information System 2 (DHIS2) in health centers and health posts. DHIS2 is an open-source, facility-based electronic monitoring tool that can monitor key indicators at the individual and aggregate levels [42]. We will implement the DHIS2 system including both hypertension and diabetes modules in MOH primary care facilities. Registries of patients with hypertension and diabetes will be constructed at each MOH facility. The project will provide hardware (e.g., tablets or desktop computers), Internet connectivity, technical support, and training and supervision of MOH staff. The DHIS2 system will be hosted on a centralized server, allowing trained health workers to enter data and monitor patient data in real time. In the WHO classification system for digital health interventions, this intervention component is a healthcare provider intervention focusing on client health records [43].

Systems monitoring and feedback of key indicators

The HEARTS component of “Systems for Monitoring” requires the use of routine administrative clinical data to monitor key indicators and to iteratively improve the quality of hypertension and diabetes care (Fig. 2) [44]. Each month, we will present aggregate reports of key indicators using data drawn from DHIS2 to MOH stakeholders at the health district (i.e., municipal) and health area (i.e., departmental) levels. The key indicators will be the same as the HEARTS-aligned secondary outcomes described below. We will use a suite of DHIS2 visualization tools built by PAHO, including maps, graphs, and dashboards. In the WHO classification system for digital health interventions, this intervention component is a health system manager intervention focusing on facility management [43]. Facility-level monitoring using DHIS2 will be complemented by ongoing health worker training and site supervision visits.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

Primary outcomes will be feasibility and acceptability as defined in the implementation outcomes framework [45]. Table 2 summarizes these outcomes with minimum benchmarks. Feasibility and acceptability will be assessed using integrated quantitative and qualitative data (mixed methods). Given the study team’s prior experience with HEARTS-aligned projects, the focus of the feasibility and acceptability assessments will be on integrating diabetes into the HEARTS model. Feasibility is the extent to which a new intervention can be successfully carried out in an organization [45]. Among MOH participants, feasibility will be assessed through the four-item feasibility of intervention measure (FIM) questionnaire [46] and semi-structured interviews. Among patient participants, feasibility will be assessed using enrollment data. Acceptability is the stakeholders’ perception that a new intervention is agreeable or satisfactory [45]. Among MOH participants, acceptability will be assessed using the acceptability of intervention measure (AIM) questionnaire [46] and semi-structured interviews. Among patient participants, acceptability will be assessed using follow-up visit data and semi-structured interviews.

Table 2.

Measures of feasibility and acceptability and their benchmarks

| Measure | Minimum benchmark |

|---|---|

| Feasibility | |

| Feasibility questionnaire (FIM) among MOH participants | Median ≥ 3.5a |

| Reasons for perceptions of feasibility/infeasibility | N/A |

| Number of patient participants with diabetes enrolled per health districtb | 25 |

| Number of patient participants with hypertension enrolled per health districtb | 25 |

| Acceptability | |

| Acceptability questionnaire (AIM) among MOH participants | Median ≥ 3.5a |

| Proportion of patient participants with subsequent follow-up visit within 3 months (among those enrolled with ≥ 3 months remaining in pilot) | 75% |

| Reasons for perceptions of acceptability/infeasibility among patient and MOH participants | N/A |

| Reasons for dropouts among patient participants | N/A |

Abbreviations: AIM, Acceptability of Intervention Measure, FIM, Feasibility of Intervention Measure, MOH Ministry of Health

Primary outcomes in this pilot study are feasibility and acceptability as defined in the Implementation Outcomes Framework

aThe FIM and AIM scales range from 1 to 5 with higher values implying greater feasibility or acceptability, respectively; the participant’s mean score across the four questions will be used

bEnrollment is defined by a patient having at least one clinic visit entered in the DHIS2 or equivalent longitudinal medical record system; a given patient may have both diabetes and hypertension and thus count toward each benchmark

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes include clinical outcomes, implementation outcomes, and patient-related outcome measures (Table 3). Clinical effectiveness outcomes are based on recommended HEARTS monitoring indicators [44, 47]. Clinical outcomes are assessed to provide pilot data to key MOH stakeholders and to rehearse study procedures rather than to evaluate effectiveness. Implementation outcomes [45] will assess facility-level adoption and the fidelity of implementation of each intervention component. Patient-related outcome measures relating to diabetes will be conducted to explore and refine the study team’s use of these instruments in Guatemalan Spanish and local Mayan languages (Kaqchikel or Tz’utujil). Measures include diabetes distress, quality of life, and self-care assessments.

Table 3.

Outcomes and data sources

| Outcome | Description and data sources |

|---|---|

| Primary outcomes | |

| Feasibility | FIM questionnaires and MOH data from DHIS2 (quantitative); semi-structured interviews with MOH participants (qualitative) |

| Acceptability | AIM questionnaires and MOH data from DHIS2 (quantitative); semi-structured interviews with patient and MOH participants (qualitative) |

| Secondary outcomes | |

| Clinical outcomes | |

| Number of patients receiving hypertension medication treatment per month (“hypertension treatment rate”) | MOH data from SIGSA (quantitative) |

| Number of patients receiving diabetes medication treatment per month (“diabetes treatment rate”) | MOH data from SIGSA (quantitative) |

| Proportion achieving glycemic control (FBG < 115 mg/dl or RBG < 160 mg/dl) among patients with diabetes | MOH data from DHIS2 (quantitative) |

| Proportion achieving control of blood pressure (< 130/80 mmHg) among patients with hypertension | MOH data from DHIS2 (quantitative) |

| Number of patients receiving hypertension medication treatment per month (“hypertension treatment rate”) | MOH data from SIGSA (quantitative) |

| Implementation outcomes | |

| Adoption | Number of participating health facilities, defined as having enrolled at least one patient with hypertension or diabetes (quantitative); reasons for variation (qualitative) |

| Fidelity (health worker training on hypertension and diabetes treatment protocols) | Proportion of health workers in each district attending all training sessions, chart audit of prescriptions to assess guideline concordance (quantitative); reasons for variation (qualitative) |

| Fidelity (team-based care and task sharing) | Proportion of primary health districts conducting at least one care coordination meeting; reasons for variation (qualitative) |

| Fidelity (access to medicines and diagnostics) | Monthly availability of MOH medications and diagnostics (quantitative) and reasons for variation (qualitative) |

| Fidelity (facility-based electronic monitoring tool) | Proportion of patient visits captured in DHIS2 each month compared to comprehensive records in SIGSA (quantitative) and reasons for variation (qualitative) |

| Fidelity (systems monitoring and feedback) | Proportion of quarterly reports viewed by health district administrators (quantitative) and reasons for variation (qualitative) |

| Usability (facility-based electronic monitoring tool) | System Usability Scale [48, 49] (quantitative) and reasons for variation (qualitative) |

| Sustainability | Program Sustainability Assessment Tool [50, 51] and Clinical Sustainability Assessment Tool [52, 53] (select questions) |

| Patient-related outcomes measures | |

| Diabetes distress | Diabetes Distress Scale [54, 55], 2-item screening and physician distress subscale |

| Disability | WHO Disability Assessment Schedule [56] |

| Multimorbidity treatment burden | Multimorbidity Illness Perceptions Scale [57, 58], treatment burden subscale |

Abbreviations: CSAT Clinical Sustainability Assessment Tool, DBP Diastolic blood pressure, DHIS2 District Health Information System, FBG Fasting blood glucose, MOH Ministry of Health, PSAT Program Sustainability Assessment Tool, RBG Random blood glucose, SBP Systolic blood pressure, SIGSA Health Management Information System, WHO World Health Organization

Study procedures

A summary of study procedures is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Summary of study procedures. Abbreviations: MOH, Ministry of Health

Recruitment

All new or existing patients with diabetes, hypertension, or both receiving care at the participating MOH primary care facilities will be enrolled in the DHIS2 system. (See “ Eligibility criteria” above.) Recruitment activities will be carried out that align with routine outreach of each MOH health facility. These activities may include meetings with local leaders, public posters, and brief announcements on social media platforms or the radio.

A subset of patient participants will be recruited for questionnaire assessments and interviews. (See “ Sampling and sample size considerations.”) Study fieldworkers who are not MOH employees will make initial contact via home visits, phone calls, or encounters at MOH health facilities. Participants who express interest in this part of the study will then receive a visit by study fieldworkers to complete informed consent and interview assessments.

All MOH participants and members of the Technical Advisory Committee will be asked to complete a structured questionnaire. The study team will use lists of personnel participating in training sessions and contacts at each health district to identify MOH participants. Members of the Technical Advisory Committee will be recruited using INCAP’s local contacts and connections.

Baseline visits at primary health care facilities

At baseline, study staff will visit all participating health centers and health posts to complete a baseline needs and readiness assessment based on HEARTS monitoring guidelines and the WHO Service Availability and Readiness Assessment tool [25, 44, 59]. Topics covered include population served, clinical services offered, available resources, staffing, and other topics relating to HEARTS.

Monthly follow-up visits at primary healthcare facilities

Study staff will conduct monthly follow-up visits at each primary healthcare facility to monitor the availability of medications and supplies, review patient registration in the DHIS2 system, assess implementation of collaborative care meetings, and provide support for any implementation issues relating to HEARTS. Study fieldworkers will also maintain a field log with notes from primary health facility visits.

Closing interviews with diabetes patient participants

Interviews consisting of structured and semi-structured questions lasting approximately 45 min will be carried out at the project’s termination. The focus will be on diabetes, as the study team has conducted extensive interviews with hypertension patients in prior HEARTS-aligned projects. The structured portion will cover patient-reported outcome measures, and the semi-structured portion will cover acceptability and implementation determinants (i.e., barriers and facilitators). The Tailored Implementation in Chronic Diseases (TICD) checklist will guide semi-structured interviews [60]. Visits will be carried out in the patient’s home or another convenient location. Interviews will be in Spanish or a local Mayan language, as preferred by the patient.

Closing interviews with MOH health workers and administrators

All MOH participants participating in the pilot will be invited to complete a structured questionnaire, focusing on feasibility (FIM instrument), sustainability (Program Sustainability Assessment Tool [50, 51] and Clinical Sustainability Assessment Tool [52, 53]), and usability of the facility-based electronic monitoring tool (System Usability Scale [48, 49]). Additionally, a subsample will participate in semi-structured interviews lasting approximately 45 min. (See “ Sampling and sample size considerations.”) The TICD checklist will guide the semi-structured interviews [60]. Interviews may be conducted in person or virtually.

Technical advisory committee meetings

We will establish a Technical Advisory Committee to provide high-level coordination among national and subnational authorities, as recommended in the HEARTS Implementation Guide [25]. The Technical Advisory Committee will play a critical role to provide guidance during the pilot and to plan for future scale-up. Members will likely include MOH administrators at the national, departmental, and health district levels, physicians and professional nurses working in each health district, representatives of the Guatemalan PAHO office, and other stakeholders (10–15 total members). Study staff at INCAP will organize meetings every 2 months during the trial and a posttrial closing meeting. Meetings will be conducted virtually and will be recorded for members who cannot attend a given session. Written meeting notes also will be shared after each session.

During the meetings, study staff will present project updates for open discussion. Using an implementation mapping approach [61], members then will discuss the implementation determinants (i.e., barriers and facilitators) that emerge during the trial for each intervention component, select implementation strategies to address component-specific determinants, clarify the causal mechanisms through which implementation strategies operate, and provide feedback on a consolidated implementation package. Study staff will guide discussions of implementation strategies using different structured tools. The Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) compilation and prior mappings of ERIC to lower-middle-income countries will be used as a foundation for proposed implementation strategies [62, 63]. Guidance from Proctor et al. will be used to specify implementation strategies [64]. The APEASE (acceptability, feasibility, effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, side effects or unintended consequences, safety, and equity) tool will be used to prioritize implementation strategies [65]. Finally, causal pathway models will be presented to link implementation strategies, mechanisms, and key implementation outcomes [66, 67].

Chart audits

Each week, a data manager will review new data entered into the DHIS2 system for missingness and errors. Physicians on the study team also will perform a clinical audit of at least 25% of patient visits. The physicians will use a structured checklist to rate the guideline concordance of clinical care and quality of data entry.

Data collection and management

Data will be collected using different collection methods. Clinical data from patient participants will be entered into DHIS2 by MOH health workers who provide standard clinical care during routine visits. DHIS2 data are stored on INCAP’s server, as approved by the MOH. Data from structured assessments will be collected electronically using a cloud-based version of REDCap hosted at INCAP. Structured assessments include health facility monitoring, chart audits, and questionnaire data from closing interviews with patients and MOH staff. Data entry and quality control checks will be performed by study staff on all structured data entered into REDCap. Qualitative data from semi-structured interviews will be collected in the field by a trained qualitative researcher on the study team. Other qualitative data will include field notes, meeting notes, and study team reflections on implementation progress and challenges [68]. Qualitative data will be securely stored on the University of Michigan’s institutional Dropbox account with routine backups to an encrypted hard drive.

Sampling and sample size considerations

The sample of health facilities will include 9 health posts and 2 health centers for a total of 11 primary health facilities. No formal sample size calculation was performed [69, 70]. This sample of health facilities and their catchment area population are consistent with recommendations in the HEARTS Implementation Guide [25].

The planned sample of patient participants will be approximately 100 individuals or 50 participants per health district. Based on the study team’s prior experience, the anticipated total breakdown is n = 45 patients with hypertension only, n = 45 with diabetes only, and n = 10 patients with both hypertension and diabetes. However, the improved clinical services may attract a greater number of patients to MOH care than anticipated for the pilot. Of these, a subsample of 10 participants with low versus high retention levels (defined by number of clinical visits within the study period; 5 participants per group) will be purposively selected among groups of individuals who had enrolled in the first two months of the study. To improve understanding of how diabetes can be integrated into the HEARTS hypertension primary care model, we will purposely sample patient participants with diabetes.

The anticipated sample of MOH participants working to implement HEARTS will be approximately 50 participants. Of these, a subsample of 20 will be purposively selected for semi-structured interviews based on high versus low perceptions of intervention feasibility and MOH role (i.e., physicians or physicians-in-training, professional nurses, auxiliary nurses, and administrators).

Including patient and MOH participants, a total of 30 semi-structured interviews are planned to achieve thematic saturation [71, 72]. Interviews will be analyzed as they are conducted, and more may be added if thematic saturation is not achieved.

Analysis plan

Quantitative analysis plan

Clinical data will be analyzed using descriptive statistics and multilevel regression models of individual-level data adjusting for clustering of participants within primary health facilities. Sociodemographic variables such as age, sex, education level, and other characteristics may be explored in regression models if sample sizes permit. Stata will be used for quantitative analyses.

Qualitative analysis plan

Semi-structured interviews will be recorded and analyzed in Spanish using qualitative directed-content analysis [73]. We will only transcribe recordings for interviews undertaken in a local Mayan language. In these cases, professional linguists will translate and transcribe into Spanish for analysis. Constructs from the Tailored Implementation in Chronic Diseases checklist will guide qualitative coding [60]. Two members of the research team proficient in Spanish will independently code transcripts, and the principal investigator will reconcile differences. Dedoose will be used for qualitative analyses [74].

Mixed-methods analysis plan

The mixed-method analysis will be based on the explanatory sequential design, as depicted in Fig. 4. Quantitative and qualitative findings of primary outcomes will be integrated using joint displays, which are a mixed methods visual technique [75]. Joint displays will show quantitative data next to illuminating participant quotes. Analysis of integrated quantitative and qualitative data will permit the study team to draw meta-inferences regarding the projects’ feasibility and to facilitate future implementation planning.

Fig. 4.

Explanatory sequential mixed-methods procedural diagram. Abbreviations: FIM, Feasibility of Intervention Measure; MOH, Ministry of Health; TICD, Tailored Implementation in Chronic Diseases

Data and safety monitoring plan

Adverse event reporting

The intervention in this study is focused on improving standard-of-care treatment of diabetes or hypertension delivered by the MOH health workers in MOH facilities. Therefore, MOH staff will be responsible for providing care for patient participants who experience an adverse event such as hypotension, hypoglycemia, or other known adverse drug effects. In our reporting role, the study team will review MOH records for adverse events (including those related to common medications), unanticipated problems, and other reportable information.

Monitoring the study

The study team will conduct monthly scheduled assessments of study recruitment, data integrity and quality, adverse events, withdrawals, and compliance with protocol. No interim analyses are planned. The trial will not employ stopping rules nor a Data Safety Monitoring Board because the study carries no more than minimal risk to participants. If the study investigators and Technical Advisory Committee think there would be potential benefit in extending the pilot trial, and funding is available, then an extension may be considered (e.g., from 6 to 12 months in duration).

Posttrial care

This trial is embedded in standard MOH primary care. All patient participants will be able to continue receiving diabetes or hypertension care according to national standards after the study closes. Depending on patient volume and logistics in the MOH, some health posts participating in the trial may refer patients to health centers for continuation of care.

Dissemination of results

Project results will be shared through a structured dissemination strategy that includes timely registration and reporting on ClinicalTrials.gov, meetings in each MOH health district at the end of the project, presentations to the Technical Advisory Committee, nontechnical reports in Spanish and English disseminated through established noncommunicable disease research and policy networks in which INCAP participates, and academic research conference presentations and peer-reviewed journal publications. Open-access journals will be prioritized for publication, and eligibility for authorship on academic products will be guided by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors guidelines.

Discussion

This pilot study will address the critical need for generalizable knowledge on how to close the “implementation gap” for CVD prevention in primary care in low- and middle-income countries. To our knowledge, the study will be among the first to investigate how integrated hypertension and diabetes management based on HEARTS can be implemented in a national primary care health system [10]. The investigators and local stakeholders in Guatemala will use results to plan a subsequent hybrid type 2 or type 3 effectiveness-implementation trial throughout Guatemala.

A key objective of the study pilot also is to explore HEARTS-aligned implementation strategies using the structured implementation mapping approach with high-level stakeholders in Guatemala. Causal pathway models also will be developed to connect implementation strategies, mechanisms, and key implementation outcomes. The implementation strategies developed in this study can inform future HEARTS projects in Guatemala and other low- and middle-income countries.

There are a few limitations and potential problems in this pilot study. First, while not designed nor powered to make causal estimates of clinical or implementation changes, the study’s sample size of health facilities and participants will be adequate for assessing the primary outcomes of feasibility and acceptability. Second, this study is embedded in the MOH primary care system. Potential problems include political crises, health worker strikes, changes in MOH leadership, and other unexpected events. To address these challenges, we will engage the Technical Advisory Committee, including high-level national authorities, and leverage INCAP’s unique position as a public institution with longstanding government connections and buy-in. Third, implementing the DHIS2 electronic monitoring tool will be ambitious given that many MOH health facilities are in isolated rural areas with unreliable Internet connectivity. If it is not possible to implement the DHIS2, we will try to leverage the existing workflows of the Health Management Information System (SIGSA) for the study.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. SPIRIT 2013 Checklist: Recommended items to address in a clinical trial protocol and related documents*.

Additional file 2. CONSORT 2010 checklist of information to include when reporting a pilot or feasibility trial*

Additional file 3. The TIDieR (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) Checklist.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the efforts of Ministry of Health administrators and clinicians who work to implement the World Health Organization’s HEARTS model in Guatemala.

Abbreviations

- AIM

Acceptability of Intervention Measure

- APEASE

Acceptability, feasibility, effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, side effects or unintended consequences, safety, and equity

- DBP

Diastolic blood pressure

- DHIS2

District Health Information System 2

- FBG

Fasting blood glucose

- FIM

Feasibility of intervention measure

- HbA1c

Hemoglobin A1c

- HEARTS

Healthy lifestyle counseling, evidence-based protocols, access to medicines, risk-based management, team care and task sharing, and systems monitoring

- INCAP

Institute of Nutrition of Central America and Panama

- MOH

Ministry of Health

- PAHO

Pan American Health Organization

- PROEDUSA

Department of Health Training and Education

- PSAT

Program Sustainability Assessment Tool

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- SIGSA

Health management information system

- TICD

Tailored Implementation in Chronic Diseases

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

DF conceived the idea for this study. DF, MH, and MRZ obtained funding. MRZ provided institutional resources to conduct the study. DF and IAW wrote the first draft of the manuscript with substantial revisions from JJR, LFA, TCG, VI, EP, MDH, and PR. IAW, JJR, and LFA led the project administration, including coordinating with the Ministry of Health. All authors provided input on multiple iterations of the protocol and approved this submission.

Funding

Funding support for this study is provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (K23HL161271) and the University of Michigan Caswell Diabetes Institute. The funders were not involved in the role in the conceptualization, design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

Availability of data and materials

This project will produce multiple types of data, including patients’ clinical information, health facility assessments, and structured and semi-structured interviews. Deidentified data, analytic code, and data dictionaries will be made available on the NHLBI BioLINCC data repository (https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/) after the study concludes. Semi-structured interview transcripts and structured questionnaire data will not be shared due to privacy concerns and risk of re-identification.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research has been approved by the Ethics Committees of the Ministry of Health of Guatemala (07–2023), INCAP (CIE-REV 124/2023), and the University of Michigan (HUM00234613). Protocol revisions will be submitted for approval at each institution’s ethics committee. Informed consent will not be obtained from patient participants receiving routine care at MOH primary care facilities as the research meets all five required criteria in the revised Common Rule. Verbal consent will be obtained by study staff from participants interviewed at the study conclusion and from stakeholders participating in the Technical Advisory Committee.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

D. F. and I. A. W. have served as consultants for the World Health Organization. M. D. H. has pending patents for heart failure polypills. George Health Enterprises Pty Ltd. (GH) and its subsidiary, George Medicines Pty Ltd., have received investment funds to develop fixed‐dose combination products, including combinations of blood pressure‐lowering drugs. GH is the social enterprise arm of The George Institute for Global Health. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Thomas H, Diamond J, Vieco A, et al. Global atlas of cardiovascular disease 2000–2016: the path to prevention and control. Glob Heart. 2018;13(3):143–163. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2018.09.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yusuf S, Rangarajan S, Teo K, et al. Cardiovascular risk and events in 17 low-, middle-, and high-income countries. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(9):818–827. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou B, Carrillo-Larco RM, Danaei G, et al. Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet. 2021;398:957. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01330-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flood D, Seiglie JA, Dunn M, et al. The state of diabetes treatment coverage in 55 low-income and middle-income countries: a cross-sectional study of nationally representative, individual-level data in 680 102 adults. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021;2(6):e340–e351. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(21)00089-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO . Hearts: technical package for cardiovascular disease management in primary health care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaffe MG, Lee GA, Young JD, Sidney S, Go AS. Improved blood pressure control associated with a large-scale hypertension program. JAMA. 2013;310(7):699–705. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.108769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel P, Ordunez P, DiPette D, et al. Improved blood pressure control to reduce cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality: the standardized hypertension treatment and prevention project. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2016;18(12):1284–1294. doi: 10.1111/jch.12861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ordunez P, Campbell NR, Giraldo Arcila GP, et al. HEARTS in the Americas: innovations for improving hypertension and cardiovascular disease risk management in primary care. Rev Panam Salud Publica. Special Issue HEARTS. 2022;46:e96. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35855441/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Yusuf S, Joseph P, Rangarajan S, et al. Modifiable risk factors, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in 155 722 individuals from 21 high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (PURE): a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10226):795–808. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32008-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO . Improving hypertension control in 3 million people: country experiences of programme development and implementation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flood D, Edwards EW, Giovannini D, et al. Integrating hypertension and diabetes management in primary health care settings: HEARTS as a tool. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2022;46:e150. doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2022.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. GBD Compare | Viz Hub. 2023. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/ (accessed April 10, 2023).

- 13.International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th edition: International Diabetes Federation, 2021.

- 14.Paniagua-Avila A, Fort MP, Glasgow RE, et al. Evaluating a multicomponent program to improve hypertension control in Guatemala: study protocol for an effectiveness-implementation cluster randomized trial. Trials. 2020;21(1):509. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04345-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Gotzsche PC, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ. 2013;346:e7586. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ. 2016;355:i5239. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lancaster GA, Thabane L. Guidelines for reporting non-randomised pilot and feasibility studies. Pilot Feasibil Stud. 2019;5:114. doi: 10.1186/s40814-019-0499-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aschbrenner KA, Kruse G, Gallo JJ, Plano Clark VL. Applying mixed methods to pilot feasibility studies to inform intervention trials. Pilot Feasibil Stud. 2022;8(1):217. doi: 10.1186/s40814-022-01178-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearson N, Naylor PJ, Ashe MC, Fernandez M, Yoong SL, Wolfenden L. Guidance for conducting feasibility and pilot studies for implementation trials. Pilot Feasibil Stud. 2020;6(1):167. doi: 10.1186/s40814-020-00634-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eldridge SM, Lancaster GA, Campbell MJ, et al. Defining feasibility and pilot studies in preparation for randomised controlled trials: development of a conceptual framework. PLos One. 2016;11(3):e0150205. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.NCCIH. Pilot studies: common uses and misuses. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/grants/pilot-studies-common-uses-and-misuses (accessed June 14, 2023).

- 23.Ojo T, Lester L, Iwelunmor J, et al. Feasibility of integrated, multilevel care for cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and HIV in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs): a scoping review. PLos One. 2019;14(2):e0212296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curran GM. Implementation science made too simple: a teaching tool. Implement Sci Commun. 2020;1(1):27. doi: 10.1186/s43058-020-00001-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO . HEARTS technical package for cardiovascular disease management in primary health care: implementation guide. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Instituto Nacional de Estadística . Encuesta Nacional de Condiciones de Vida 2014 (ENCOVI): Principales resultados. Guatemala, Central America: Instituto Nacional de Estadística; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Instituto Nacional de Estadística Guatemala. Resultados del XII Censo Nacional de Población y VII de Vivienda: Principales Resultados Censo 2018. 2019. https://www.censopoblacion.gt/archivos/Principales_resultados_Censo2018.pdf (accessed May 29, 2023).

- 28.Avila C, Bright R, Gutierrez J, et al. Guatemala Health System Assessment, August 2015. Bethesda, MD: Health Finance & Governance Project, Abt Associates Inc.; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ministerio de Salud Pública y Asistencia Social . Plan estratégico nacional para la prevención de enfermedades no transmisibles 2015–2020. Guatemala City: Comisión Nacional para la Prevención de Enfermedades Crónicas no Transmisibles y Cáncer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ministerio de Salud Pública y Asistencia Social/Guatemala . Lineamientos para implementar intervenciones v seleccionar medicamentos para atender las morbilidades de enfermedades cronicas no transmisibles. Guatemala City: MSPAS; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ministerio de Salud Pública Asistencia Social . Normas de Atención Salud Integral Para Primero y Segundo Nivel 2018. Guatemala City: MSPAS; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anson A, Ramay B, Esparza AR, Bero L. Availability, prices and affordability of the World Health Organization’s essential medicines for children in Guatemala. Global Health 2012;8:22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22747646/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Pan American Health Organization. Implementarán iniciativa Hearts para la prevención y el control de las enfermedades cardiovasculares (ECV) en Guatemala. 2022. https://www.paho.org/es/noticias/11-11-2022-implementaran-iniciativa-hearts-para-prevencion-control-enfermedades (accessed May 15, 2023).

- 34.Chary A, Greiner M, Bowers C, Rohloff P. Determining adult type 2 diabetes-related health care needs in an indigenous population from rural Guatemala: a mixed-methods preliminary study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):476. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flood D, Mux S, Martinez B, et al. Implementation and outcomes of a comprehensive type 2 diabetes program in rural Guatemala. PLos One. 2016;11(9):e0161152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fort MP, Paniagua-Avila A, Beratarrechea A, et al. Stakeholder engagement in the translation of a hypertension control program to Guatemala’s public primary health care system: lessons learned, challenges, and opportunities. Glob Heart. 2019;14(2):155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2019.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fort MP, Mundo W, Paniagua-Avila A, et al. Hypertension in Guatemala’s public primary care system: a needs assessment using the health system building blocks framework. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):908. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06889-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ministerio de Salud Pública y Asistencia Social/Guatemala. Algoritmo para el manejo de los enfermos con diabetes mellitus, 2021.

- 39.Ministerio de Salud Pública y Asistencia Social/Guatemala. Algoritmo para el manejo de los enfermos con hipertensión arterial, 2021.

- 40.Paniagua-Avila A, Shelton RC, Guzman AL, et al. Assessing the implementation of a multi-component hypertension program in a Guatemalan under-resourced dynamic context: an application of the RE-AIM/PRISM extension for sustainability and health equity. Res Sq 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.DiPette DJ, Skeete J, Ridley E, et al. Fixed-dose combination pharmacologic therapy to improve hypertension control worldwide: clinical perspective and policy implications. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2019;21(1):4–15. doi: 10.1111/jch.13426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nigeria Ministry of Health, University of Oslo, WHO Nigeria, Resolve to Save Lives. DHIS2 Package for Hypertension Control Programs. https://s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/content.dhis2.org/Publications/DHIS2+for+Hypertension+Control+Programs.pdf (accessed February 4, 2023).

- 43.World Health Organization. Classification of digital health interventions v1. 0: a shared language to describe the uses of digital technology for health: World Health Organization, 2018.

- 44.WHO . HEARTS technical package for cardiovascular disease management in primary health care: systems for monitoring. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weiner BJ, Lewis CC, Stanick C, et al. Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):108. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0635-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.WHO . HEARTS-D: diagnosis and management of type 2 diabetes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brooke J. SUS-a quick and dirty usability scale. Usabil Eval Industry. 1996;189(194):4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sevilla-Gonzalez MDR, Moreno Loaeza L, Lazaro-Carrera LS, et al. Spanish version of the system usability scale for the assessment of electronic tools: development and validation. JMIR Hum Factors. 2020;7(4):e21161. doi: 10.2196/21161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Program Sustainability Assessment Tool v2. 2013. https://sustaintool.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Sustainability-ToolV2_w-scoring_12.11.13.pdf (accessed April 25, 2023).

- 51.Luke DA, Calhoun A, Robichaux CB, Elliott MB, Moreland-Russell S. The program sustainability assessment tool: a new instrument for public health programs. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:130184. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clinical Sustainability Assessment Tool. 2019. https://sustaintool.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/CSAT-tool-and-scoring_1.14.20.pdf (accessed April 26, 2023).

- 53.Malone S, Prewitt K, Hackett R, et al. The clinical sustainability assessment tool: measuring organizational capacity to promote sustainability in healthcare. Implement Sci Commun. 2021;2(1):77. doi: 10.1186/s43058-021-00181-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Earles J, et al. Assessing psychosocial distress in diabetes: development of the diabetes distress scale. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(3):626–631. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.3.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fisher L, Glasgow RE, Mullan JT, Skaff MM, Polonsky WH. Development of a brief diabetes distress screening instrument. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(3):246–252. doi: 10.1370/afm.842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.WHO . WHO Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0) Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gibbons CJ, Kenning C, Coventry PA, et al. Development of a multimorbidity illness perceptions scale (MULTIPleS) PLos One. 2013;8(12):e81852. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mejías-Trueba M, Fernández-Rubio B, López-Hermoso C, Fernández-Rubio G, Jiménez-De Juan C, Rodríguez-Perez A. Cross-cultural adaptation into Spanish of the MULTIPleS scale in elderly patients with multimorbidity. Med Clín (English Edition) 2022;159(7):327–329. doi: 10.1016/j.medcle.2022.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.WHO . Service Availability and Readiness Assessment (SARA): an annual monitoring system for service delivery: reference manual. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Flottorp SA, Oxman AD, Krause J, et al. A checklist for identifying determinants of practice: a systematic review and synthesis of frameworks and taxonomies of factors that prevent or enable improvements in healthcare professional practice. Implement Sci. 2013;8:35. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fernandez ME, Ten Hoor GA, van Lieshout S, et al. Implementation mapping: using intervention mapping to develop implementation strategies. Front Public Health. 2019;7:158. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gyamfi J, Iwelunmor J, Patel S, et al. Implementation outcomes and strategies for delivering evidence-based hypertension interventions in lower-middle-income countries: evidence from a multi-country consortium for hypertension control. PLos One. 2023;18(5):e0286204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0286204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. 2013;8:139. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a guide to designing interventions. Great Britain: Silverback Publishing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lewis CC, Klasnja P, Powell BJ, et al. From classification to causality: advancing understanding of mechanisms of change in implementation science. Front Public Health. 2018;6:136. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sales AE, Barnaby DP, Rentes VC. Letter to the editor on “the implementation research logic model: a method for planning, executing, reporting, and synthesizing implementation projects” (Smith JD, Li DH, Rafferty MR. The implementation research logic model: a method for planning, executing, reporting, and synthesizing implementation projects. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):84. doi: 10.1186/s13012-020-01041-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Finley EP, Huynh AK, Farmer MM, et al. Periodic reflections: a method of guided discussions for documenting implementation phenomena. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):153. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0610-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hertzog MA. Considerations in determining sample size for pilot studies. Res Nurs Health. 2008;31(2):180–191. doi: 10.1002/nur.20247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Billingham SA, Whitehead AL, Julious SA. An audit of sample sizes for pilot and feasibility trials being undertaken in the United Kingdom registered in the United Kingdom clinical research network database. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(5):104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Francis JJ, Johnston M, Robertson C, et al. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol Health. 2010;25(10):1229–1245. doi: 10.1080/08870440903194015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guest G. How many interviews are enough?: An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dedoose. 2023. www.dedoose.com (accessed August 26, 2023).

- 75.Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6 Pt 2):2134–2156. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. SPIRIT 2013 Checklist: Recommended items to address in a clinical trial protocol and related documents*.

Additional file 2. CONSORT 2010 checklist of information to include when reporting a pilot or feasibility trial*

Additional file 3. The TIDieR (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) Checklist.

Data Availability Statement

This project will produce multiple types of data, including patients’ clinical information, health facility assessments, and structured and semi-structured interviews. Deidentified data, analytic code, and data dictionaries will be made available on the NHLBI BioLINCC data repository (https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/) after the study concludes. Semi-structured interview transcripts and structured questionnaire data will not be shared due to privacy concerns and risk of re-identification.