Abstract

Introduction:

This research evaluated existing health equity frameworks as they relate to social determinants of health (SDOHs) and individual factors that may impact injury outcomes and identify gaps in coverage using the Healthy People (HP) 2030 key domains.

Methods:

The study used a list of health equity frameworks sourced from previous literature. SDOHs and individual factors from each framework were identified and categorized into the Healthy People 2030 domains. Five injury topic areas were used as examples for how SDOHs and individual factors can be compared to injury topic-specific health disparities to identify health equity frameworks to apply to injury research.

Results:

The study identified 59 SDOHs and individual factors from the list of 33 health equity frameworks. The number of SDOHs and individual factors identified varied by Healthy People 2030 domain: Neighborhood and Built Environment contained 16 (27.1%) SDOHs and individual actors, Social and Community Context contained 22 (37.3%), Economic Stability contained 10 (16.9%), Healthcare Access and Quality contained 10 (16.9%), and Education Access and Quality contained one (1.7%). Twenty-three (39.0%) SDOHs/individual factors related to traumatic brain injury, thirteen (22.0%) related to motor vehicle crashes and suicide, 11 (18.6%) related to drowning and older adult falls. Eight frameworks (24.2%) covered all HP 2030 key domains and may be applicable to injury topics.

Conclusions:

Incorporating health equity into research is critical. Health equity frameworks can provide a way to systematically incorporate health equity into research. The findings from this study may be useful to health equity research by providing a resource to injury and other public health fields.

Practical Applications:

Health equity frameworks are a practical tool to guide injury research, translation, evaluation, and program implementation. The findings from this study can be used to guide the application of health equity frameworks in injury research for specific topic areas.

Keywords: Injury, Framework, Health equity, Social determinants of health, Healthy People 2030

1. Introduction

The prevention of injuries, both intentional and unintentional, is a significant public health challenge. In 2021, unintentional injury, suicide, and homicide were the first, second, and fourth leading causes of death, respectively, among all decedents aged 1–44 (CDC NCIPC, 2021). The burden of intentional and unintentional injuries varies across the lifespan and recent publications have illustrated the disproportionate distribution of injuries among people from racial and ethnic minority groups, and by geography, urbanicity, and other social determinants of health (SDOHs) such as economic stability and health care access, and individual factors such as age (Kegler et al., 2022; Miller et al., 2021; Moreland et al., 2022; Shaw et al., 2022; Stone et al., 2022; Wulz et al., 2022). SDOHs are defined as “the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks”(Department of Health and Human Services, 2022). SDOHs are factors that impact health equity, which is defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as the fair and just opportunity for all persons to attain their highest level of health (CDC NCCDPHP, 2022). SDOHs along with individual factors, or a person’s behaviors or individual characteristics (e.g., biology, age), (WHO, 2017) can impact health inequities (Pirkis et al., 2023; CDC OMHHE, 2022) and may affect outcomes differently in various injury topic areas—for example, suicide, traumatic brain injury (TBI), older adult falls, drowning, and motor vehicle crashes. These individual factors and SDOHs can influence health outcomes. For example, although race/ethnicity is not considered an SDOH according to the HHS definition, the way society uses race or ethnicity in systems, policies, actions, and attitudes can influence health outcomes.

Achieving health equity across populations requires making the connection between identified health disparities and their root causes. Underlying these health disparities may be inequities in economic, social, or environmental factors that serve as barriers or opportunities for people to achieve their highest level of health (CDC OMHHE, 2022). Addressing these underlying inequities may help inform the public health field regarding resource allocation, particularly for culturally sensitive, tailored interventions, and advancing health equity. Health equity frameworks may inform metrics for measuring changes in the key determinants of and barriers to achieving better health. These metrics may provide measures for the reductions in health disparities between populations to help gauge progress towards health equity (Braveman et al., 2017).

The use of health equity frameworks in disparities-focused research may be one potential avenue for assessing how disease, injury, and violence prevent some populations from achieving optimal health. Healthy People 2030 (HP 2030) framework uses data-driven objectives to measure health equity progress on a national level by addressing the upstream factors that impact health disparities (Department of Health and Human Services, 2022). The HP 2030 framework consists of measurable objectives grouped into five key domains which emphasize the importance of addressing upstream factors to improve health and eliminate health disparities. The five key domains include:

Economic Stability (e.g., affordable housing and homes)

Education Access and Quality (e.g., education among people with disabilities)

Health Care Access and Quality (e.g., availability of health insurance)

Neighborhood and Built Environment (e.g., transportation safety), and

Social and Community Context (e.g., positive relationships at home) (Department of Health and Human Services, 2022).

The SDOHs and individual factors that apply to the five key domains of the HP 2030 framework may have differing levels of relevancy depending on the injury topic area. Reporting health disparities between groups is common in injury literature and is an essential part of surveilling and monitoring injury within populations. A recent literature review of injury-related meta-analyses and systematic reviews highlighted a variety of health equity frameworks and indices that have been used in research to measure and characterize health equity within populations (Lennon et al., 2022). However, only three of the meta-analyses and reviews identified in the literature search applied health equity frameworks to injury topics. While some of these tools for measuring health equity may not be universally applicable to all injury topic areas, relatively few studies to date have explored the utility of well-referenced health equity frameworks for injury research (Lennon et al., 2022).

Health equity frameworks have been used in the literature to conceptualize health equity. There remain areas of opportunity for exploring the applicability of health equity frameworks to injury topic areas to aid in conceptualizing health equity in injury and understand what factors may be most at play in causing inequities in injury outcomes. Conceptualizing health equity in a framework can help researchers understand relationships between different SDOHs and individual factors and help instill a health equity lens during research, translation, evaluation, and program implementation. Health equity frameworks are also a practical tool that can be used to translate research into public health action by informing the development of equitable interventions that address the complex, interrelated factors that influence health equity (Peterson et al., 2021; Woodward et al., 2021). The CDC National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC) commonly utilizes the Social-Ecological Model—which is a four-level model to understand the interplay of risk and protective factors between the individual, relationship, community, and societal levels—to conceptualize SDOHs and health equity (CDC NCIPC, 2022a). Other recent research has created a blended injury equity framework using the Social-Ecological Model, Three Levels of Racism, and the Haddon matrix (Kendi & Macy, 2023). The purpose of this research is to evaluate existing health equity frameworks as they relate to SDOHs and individual factors that may impact injury outcomes, to characterize frameworks that may be considered to apply to injury topic areas, and to identify gaps in coverage of frameworks by using the HP 2030 key domains.

2. Methods

For the purposes of this research, a health equity guiding framework was defined as a theoretical construct that assesses key domains and concepts associated with health equity. This study assessed 33 health equity frameworks from a previous literature review (Table 1) (Lennon et al., 2022). Additional information regarding these frameworks are noted elsewhere. Due to the effect of both SDOHs and individual factors on injury health outcomes, both were included in this study.

Table 1.

Health equity frameworks included in analysis of social determinants of health and individual factors.

| Framework | Description | Citation(s) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| A Public Health Framework for Reducing Health Inequities | Depicts the relationship between social inequalities and health, with a specific focus on inequities related to social, institutional, and living conditions. | National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016 |

| Community Stress Theory | Stressors, such as issues related to inequality, can weaken the body’s ability to respond to external challenges. | Gee & Payne-Sturges, 2004 |

| Dahlgren and Whitehead Model | Maps the influence of individual (e.g., lifestyle factors) and environmental factors (e.g., community influences, living and working conditions, etc.) on health. | de Lima Silva et al., 2014; Driscoll et al., 2013 |

| Dimensions of Food Security (Food and Agricultural Organization) | Measures the availability of food and an individual’s ability to access it through the following four dimensions: (1) availability, (2) access, (3) utilization, and (4) stability. | Bowers et al., 2020 |

| Environmental Determinants of Health | Environmental determinants include the physical, chemical, and biological factors external to a person and their impact on health (e.g., sanitation, exposure to toxins, climate change, pollution, etc.). | Salgado et al., 2020 |

| Equity-Effectiveness Model |

The effectiveness of community-level interventions decreases along a set of parameters which measures access to, and quality of, care. | Nooh et al., 2019 |

| Expansive Gender Equity Continuum | Expands upon previous gender equity models that define equity on a continuum from gender unequal to gender transformative, by including a broader definition of gender identity ranging from exclusive (i.e., only considers cisgender identities) to gender inclusive (i.e., considers people of all gender identities, including trans people and nonbinary individuals). | Restar et al., 2021 |

| Framework for Understanding Racial/ethnic Disparities in Environmental Health | Health disparities are partially caused by differential access to resources and exposures to hazards and can be grouped into four categories: (1) social processes, (2) environmental contaminants/exposures, (3) body burdens of environmental contaminants, and (4) health outcomes. | Payne-Sturges & Gee, 2006 |

| Fundamental Cause Model | Examines the relationship between socioeconomic inequalities and health; the ability to control disease/death is influenced by access to fundamental resources (e.g., knowledge, money, power, prestige, and beneficial social connections). | Tulier et al., 2019; Diez Roux, 2012 |

| Health Equity Framework | Outlines how health outcomes are influenced by complex interactions between people and their environments and centers around three foundational concepts: (1) equity at the core of health outcomes; (2) multiple, interacting spheres of influence; and a (3) historical and life-course perspective. | Peterson et al., 2021 |

| Health Equity Measurement Framework | Comprehensive model that describes the social determinants of health in a causal context and can be used to measure and monitor health equity; includes an expansive list of social determinants of health, such as the socioeconomic, cultural, and political context, health policy context, social stratification, social location, material and social circumstances, environment, quality of care, etc. | Dover & Belon, 2019 |

| Health in All Policies | Health in All Policies HiAP) is a collaborative approach that integrates and articulates health considerations into policymaking across sectors to improve the health of all communities and people. HiAP recognizes that health is created by a multitude of factors beyond healthcare and, in many cases, beyond the scope of traditional public health activities. | Lorenc et al., 2014 |

| Healthy People (2020 and 2030) | Provides science-based, national objectives each decade dedicated to improving the health of all Americans. Healthy People 2020 developed a framework that organized the social determinants of health into five key domains: (1) Economic Stability, (2) Education, (3) Health and Health Care, (4) Neighborhood and Built Environment, and (5) Social and Community Context. Healthy People 2030 established a framework to describe the initiative’s rationale and approach, including its vision, mission, foundational principles, plan of action, and overarching goals (new objectives are underway). | Welch et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2020; Mohan and Chattopadhyay, 2020; Sokol et al., 2019; Min et al., 2022; Yelton et al., 2022, Maness & Buhi, 2016; Abbott and Williams, 2015 |

| Interaction Model | Emphasizes the interaction between genes and their environment, such that individuals with different genotypes experience differential effects of environmental exposures and disease risk. | Diez Roux, 2012 |

| Life Course Approach | Applies a temporal and social perspective to analyze people’s lives within social, economic, and cultural contexts across different generations to understand current patterns of health and disease. | Taggart et al., 2020 |

| Multi-level Systems Approach | Focuses on individuals within broader contexts, such as within neighborhoods or communities, who may share similar characteristics and therefore may experience similar health outcomes. | Payne-Sturges et al., 2006a |

| Pathways Model | This model aims to reduce health and social disparities in communities by connecting high-risk individuals to care and tracking the associated outcomes. | Diez Roux, 2012 |

| Policy-oriented Approach | Analysis of patterns and trends of social inequalities in health over time and their determinants, with a specific focus on inequalities that are commonly viewed as unjust and avoidable. | Braveman, 1998 |

| PROGRESS/PROGRESS Plus | Acronym used to identify dimensions across which health inequities may occur, specifically, place of residence; race/ethnicity /culture/language; occupation; gender/sex; religion; education; socioeconomic status; and social capital. | Turnbull et al., 2020; Chhibber et al., 2021; Schröders et al., 2015; Lehne & Bolte, 2017; Schüz et al., 2021; Campos-Matos et al., 2016; Aves et al., 2017; Welch et al., 2022; Morton et al., 2016; Buttazzoni et al., 2020; Brown et al., 2017a; Brown et al., 2017b; Ahmed et al., 2022; Cohn & Harrison; 2022 |

| Psychosocial Stress Model | Health disparities arise from the stresses associated with institutional and interpersonal racism. | Dressler et al., 2005 |

| Rural Community Health & Well-Being Framework | Identifies key drivers (i.e., social, economic, and environmental factors) that influence health in rural communities and includes additional categories of important factors highlighted by rural residents. | National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016 |

| Social and Cultural Determinants of Mental Disorders | Conceptual framework to understand how social determinants interact with key genetic determinants to influence mental disorders. | Lund et al., 2018 |

| Social and Demographic Determinants of Health-related Quality of Life (QoL) | An individual’s overall sense of wellbeing including aspects of happiness, satisfaction of life, and physical, mental, psychological, and social perceptions. | Ghiasvand et al., 2020 |

| Social Determinants of Child Health (SDCH) | Examines how social determinants impact child health across time and generations through distal social factors such as poverty, material deprivation, and social inequalities. | Rajmil et al., 2020 |

| Social-Ecological Model | Theory-based framework for understanding how social and structural determinants influence health and wellbeing. | Habbab & Bhutta, 2020, Yiga et al., 2020, Pereira et al., 2019, Reno & Hyder, 2018, Greenbaum et al., 2018, Christidis et al., 2021, Allen et al., 2020, Karger et al., 2022, Taylor & Lamaro Haintz, 2018 |

| Socioeconomic Status Model | Emphasizes that race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status (SES) are related, such that certain race/ethnicity groups are disproportionately represented in lower SES groups. | Dressler et al., 2005 |

| Stress-Exposure Disease Framework | Conceptual framework that outlines the relationships between race, environmental conditions, and health. | Gee & Payne-Sturges, 2004; Payne-Sturges et al., 2006b |

| Structural-Constructivist Model | Integrates a dual perspective focused on (1) socially constructed cognitive representations within a society and (2) external factors that restrict individuals, specifically social relationships, and expectations of others (e.g., race, as a concept, is socially or culturally constructed). | Dressler et al., 2005 |

| The Frieden Framework | Five-tier pyramid for improving public health; the base of the pyramid includes (1) interventions that impact social determinants of health (e. g., poverty, education), followed by (2) interventions that benefit the general population (e. g., fluoridated water), (3) interventions that help large segments of the population (e.g., immunizations), (4) clinical interventions for the prevention of certain conditions (e.g., cardiovascular disease), and (5) health education interventions (i.e., most labor-intensive and potentially lowest impact). | National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016 |

| Three Levels of Racism Framework | Theoretical framework for understanding racial health inequities and developing effective interventions to reduce inequities on three distinct levels: (1) institutionalized, (2) personally mediated, and (3) internalized. | Chandler et al., 2022 |

| Warnecke’s Model for Analysis of Population Health and Disparities | Defines factors impacting health disparities as proximal, intermediate, or distal and focuses on individual-level outcomes as they relate to specific determinants (i.e., social conditions and policies, institutional context, social context, and physical context). | Zahnd & McLafferty, 2017 |

| Weathering Hypothesis | Proposes that cumulative exposure to social, economic, and political disadvantage leads to rapid decline in physical health. | Forde et al., 2019 |

| World Health Organization (WHO) Conceptual Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) Framework | Outlines how social, economic, and political factors (e.g., income, education, occupation, gender, race, and ethnicity) impact an individual’s socioeconomic position, which, in turn, influences their vulnerability and exposure to health conditions. | Chen et al., 2020, Bhojani et al., 2019; Dover & Belon, 2019; Wang et al., 2020; Allen et al., 2020; Armstead et al., 2021; Batista et al., 2018; Owusu-Addo et al., 2016; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016; Min et al., 2022 |

| WHO International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model | In-depth classification of holistic components of functioning, disability, and health-related domains. | Malele-Kolisa et al., 2019 |

| WHO Social, Political, Economic and Cultural (SPEC) conceptual model | Explains social exclusions as a process rather than a state operating along different dimensions and individual, regional, and global levels. | van Hees et al., 2019 |

This study used the HP 2030 Framework to categorize SDOHs and individual factors into five key domains: Economic Stability, Education Access and Quality, Health Care Access and Quality, Neighborhood and Built Environment, and Social and Community Context (Department of Health and Human Services, 2022). Each health equity framework was analyzed by two independent reviewers to assess which SDOHs and individual factors the frameworks addressed. Then, the SDOHs and individual factors were categorized by the key domains of the HP 2030 Framework using a best fit model, based on alignment with the objectives outlined in the HP 2030 Framework, to identify and understand gaps in coverage in the five key domains (Department of Health and Human Services, 2022). The authors identified SDOHs and individual factors from the full list that most related to injury, including drowning, older adult falls, motor vehicle crashes, suicide, and traumatic brain injury (CDC NCIPC, 2022b; CDC NCIPC, 2023a; CDC NCIPC, 2023b; CDC NCIPC 2023c; CDC NCIPC 2023d). The authors used the list of health disparities from the referenced CDC NCIPC webpages to compare to the SDOHs and individual factors from the frameworks. If the two reviewers did not agree on key domain categorization, all authors were engaged in a discussion to reach consensus. The HP 2030 Framework domains which encompassed the SDOHs and individual factors specifically related to injury topic areas were compared with the health equity frameworks to understand potential alignment of health equity frameworks with injury topic areas.

3. Results

There were 33 health equity frameworks included in this study (Table 2). Of the 33 health equity frameworks, eight frameworks were found to cover all five of the HP 2030 key domains: Dahlgren and Whitehead Model; Environmental determinants of health; Life Course Approach; Policy-Oriented Approach; Social and Cultural Determinants of Mental Disorders; Social-Ecological Model; the Frieden Framework; and the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Conceptual SDOH Framework. Most of the health equity frameworks contained SDOHs and individual factors that addressed at least one domain (n =29; 87.9%). The most common domain was Social and Community Context (n =30; 90.9%), followed by Neighborhood and Built Environment (n =26; 78.8%), Economic Stability (n =26; 78.8%), Healthcare Access and Quality (n =23; 69.7%), and lastly Education Access and Quality (n =10; 30.3%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

| Healthy People 2030 Key Domains | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Health Equity Framework (N = 33) | Economic Stability | Education Access and Quality | Health Care Access and Quality | Social and Community Context | Neighborhood and Built Environment |

|

| |||||

| Dahlgren and Whitehead Model | X | X | X | X | X |

| Environmental determinants of health | X | X | X | X | X |

| Life Course Approach | X | X | X | X | X |

| Policy-oriented approach | X | X | X | X | X |

| Social and cultural determinants of mental disorders | X | X | X | X | X |

| Social-Ecological Model | X | X | X | X | X |

| The Frieden Framework | X | X | X | X | X |

| WHO Conceptual SDOH Framework | X | X | X | X | X |

| A Public Health Framework for Reducing Health Inequities | X | X | X | X | |

| Health equity measurement framework | X | X | X | X | |

| Health in All Policies | X | X | X | X | |

| World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model |

X | X | X | X | |

| Multi-Level Systems Approach | X | X | X | X | |

| Pathways Model | X | X | X | X | |

| PROGRESS/PROGRESS Plus | X | X | X | X | |

| Psychosocial stress model | X | X | X | X | |

| Rural Community Health & Well-Being Framework | X | X | X | X | |

| Social determinants of child health (SDCH) | X | X | X | X | |

| WHO Social, Political, Economic and Cultural (SPEC) conceptual model | X | X | X | X | |

| Warnecke’s Model for Analysis of Population Health and Disparities | X | X | X | X | |

| Weathering Hypothesis | X | X | X | X | |

| Interaction Model | X | X | X | ||

| Social and demographic determinants of health-related quality of life (QoL) | X | X | X | ||

| Stress-Exposure Disease Framework | X | X | X | ||

| Community Stress Theory | X | X | |||

| Expansive gender equity continuum | X | X | |||

| Framework for understanding racial/ethnic disparities in environmental health | X | X | |||

| Socioeconomic Status Model | X | X | |||

| Structural-Constructivist Model | X | X | |||

| Dimensions of food security (Food and Agricultural Organization) | X | ||||

| Equity-Effectiveness Model | X | ||||

| Fundamental Cause Model | X | ||||

| Three Levels of Racism Framework | X | ||||

| TOTAL (%) | 26 (78.8) | 10 (30.3) | 23 (69.7) | 30 (90.9) | 26 (78.8) |

Includes health equity frameworks found in Table 1.

Healthy People (HP) 2030 prioritizes focus on social determinants of health (SDOHs) and individual factors that contribute to health outcomes. Five key domains are used in the HP 2030 framework: Economic Stability, Education Access and Quality, Health Care Access and Quality, Neighborhood and Built Environment, and Social and Community Context.

A total of 59 SDOHs/individual factors (Table 3) were identified from the 33 health equity frameworks included in this study (Lennon et al., 2022). The SDOHs and individual factors identified by the health equity frameworks varied by HP 2030 domain: 22 (37.3%) SDOHs/individual factors fit under Social and Community Context, 16 (27.1%) under the Neighborhood and Built Environment domain, 10 (16.9%) under Economic Stability, 10 (16.9%) under Healthcare Access and Quality, and one (1.7%) under Education Access and Quality (Table 3).

Table 3.

Social determinants of health and individual factors identified in health equity frameworksa categorized by the healthy people 2030 key domains.

| Healthy People 2030 Key Domains | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Social Determinants of Health (SDOHs) and Individual Factorsb Identified (N = 59) | Economic Stability | Education Access and Quality | Health Care Access and Quality | Social and Community Context | Neighborhood and Built Environment |

|

| |||||

| Active living/Activities and participation | X | ||||

| Age | X | ||||

| Agriculture/food production and accessc | X | ||||

| Biology | X | ||||

| Childcare | X | ||||

| Community resiliencec | X | ||||

| Crime | X | ||||

| Culture | X | ||||

| Disability status | |||||

| Drug/Alcohol misuse | X | ||||

| Economic security | X | ||||

| Education | X | ||||

| Employment class | X | ||||

| Employment status | X | ||||

| English proficiency | X | ||||

| Environmental Conditions/Exposure/Factors, including climate change | X | ||||

| Gender | X | ||||

| Genetic predictorsc | X | ||||

| Health beliefs | X | ||||

| Health insurance status | X | ||||

| Health literacy | X | ||||

| Health status/conditions | X | ||||

| Healthcare availabilityc | X | ||||

| Healthcare services | X | ||||

| Healthcare system accountabilityc | X | ||||

| Healthcare system capacity buildingc | X | ||||

| Healthcare system factors/characteristicsc | X | ||||

| Healthcare utilization | X | ||||

| Healthy aging | X | ||||

| Household structure/type | X | ||||

| Housing | X | ||||

| Immigration/refugee status | X | ||||

| Income | X | ||||

| Income inequality | X | ||||

| Minority status | X | ||||

| Mobility | X | ||||

| Nativity/Country of origin | X | ||||

| Noise | X | ||||

| Occupation/Employment | X | ||||

| Oral care | X | ||||

| Physical activity | X | ||||

| Pollution | X | ||||

| Population density | X | ||||

| Racism and discrimination | X | ||||

| Religion | X | ||||

| Residential location/neighborhood | X | ||||

| Resource access | X | ||||

| Sanitation | X | ||||

| Segregation | X | ||||

| Sex | X | ||||

| Sexual orientation | X | ||||

| Social context/environmentc | X | ||||

| Social support/relationshipsc | X | ||||

| Socioeconomic status | X | ||||

| Soil | X | ||||

| Stigma | X | ||||

| Tobacco use | X | ||||

| Transportation (including traffic) | X | ||||

| Veteran status | X | ||||

| Violence | X | ||||

| Work environment | X | ||||

| TOTAL (%) | 10 (16.9) | 1 (1.7) | 10 (16.9) | 22 (37.3) | 16 (27.1) |

Note: SDOHs and individual factors were categorized in the key domains using a best fit approach based on the HP 2030 objectives specified for each key domain.

Includes health equity frameworks found in Table 1.

Individual factors (e.g., biology, age) can also impact health inequities. For example, although race and ethnicity are not considered SDOHs according to the HHS definition, the way society perceives those of different races and ethnicities can influence social opportunities and disadvantages.

Definitions for select terms:

Agriculture/food production and access addresses “supply side” of food security at the national or international level and is determined by economic and physical access factors such as the level of food production, stock levels, and net trade (this includes food access, which refers to household level food security and whether individuals can obtain food, food stability, food availability, food deserts, rurality, agriculture and food production).

Community resilience refers to the ability of individuals, households, and communities to use available resources and adapt to changing conditions to recover from the health, social, and economic impacts of an adverse event such as a hurricane or pandemic.

Genetic predictors refer to genetic predispositions which may influence the development of certain health conditions or diseases.

Healthcare availability refers to healthcare infrastructure and provision, specifically the presence of health professionals, services, and supplies; existence and physical location of healthcare facilities and other infrastructure (e.g., ambulances); and the organizational characteristics of a health system (e.g., wait times and hours of operation).

Healthcare system factors/characteristics refers to access to quality, affordable, and timely preventive and curative health care that recognizes individual patient needs, including their health history and personal preferences.

Healthcare system accountability is the responsibility of the healthcare system to provide equitable and quality care that is responsive to individual health needs, personal situations, and broader socioeconomic contexts.

Healthcare system capacity building is defined as the development and strengthening of knowledge, skills, systems, and leadership in healthcare settings which focus on reducing health disparities and connecting high-risk individuals to care.

Power/prestige refers to an imbalance in status and opportunities between populations based on factors such as race and ethnicity, gender, income, or sexual orientation.

Safety includes injury deaths, juvenile arrests, and the general state of feeling “safe”.

Social support/relationships includes family and social support.

Social context/environment are factors and circumstances in the broader social setting (such as exposure to community stressors or personal/life experiences) that shape behaviors, beliefs, and/or perceptions of individuals and groups of people.

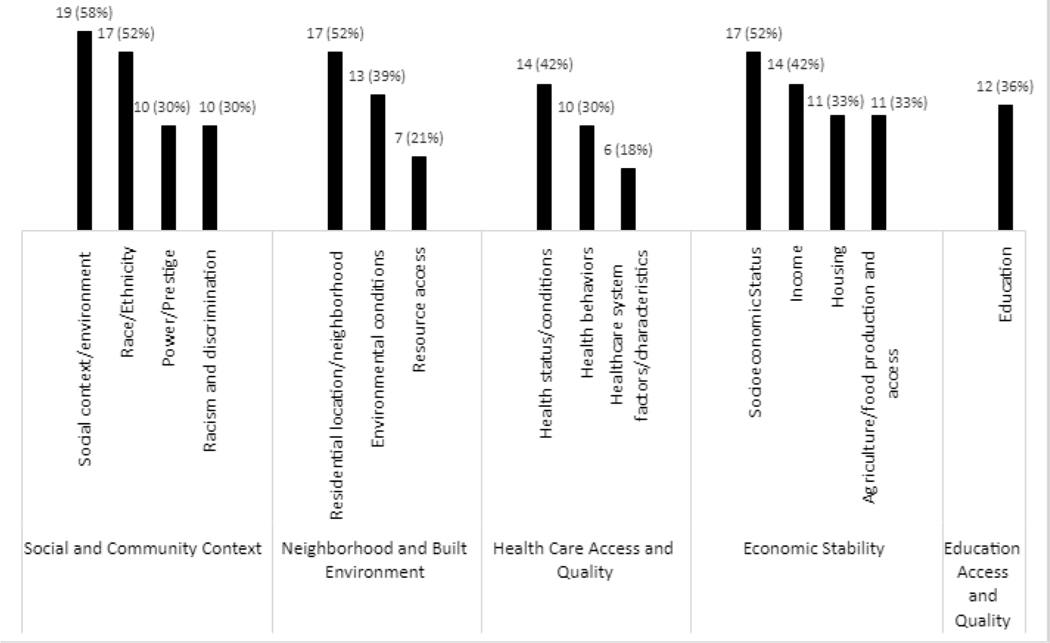

The most frequently identified SDOHs and individual factors in the list of health equity frameworks (N =33) within each respective domain were social context/environment (n = 19; Social and Community Context HP 2030 key domain), socioeconomic status (n = 17; Economic Stability), residential location/neighborhood (n = 17; Neighborhood and Built Environment), education (n = 12; Education Access and Quality), and health status/conditions (n = 14; Healthcare Access and Quality) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Top Three Social Determinants of Healtha and Individual Factors Most Frequently Identified in Health Equity Guiding Frameworks Categorized by Healthy People 2030 Key Domainsb-d (N =33).

a Social determinants of health (SDOHs) are broader in scope and include the social, economic, and environmental factors that influence the health and well-being of communities. SDOHs and individual factors can be categorized in the five different domains in the Healthy People 2030 model: Economic Stability, Education Access and Quality, Health Care Access and Quality, Neighborhood and Built Environment, and Social and Community Context.

b Includes health equity frameworks found in Table 1.

c Only one SDOH was categorized in the Education Access and Quality domain, therefore only one is shown.

d Definitions for select terms:

Agriculture/food production and access addresses “supply side” of food security at the national or international level and is determined by economic and physical access factors such as the level of food production, stock levels, and net trade (this includes food access, which refers to household level food security and whether individuals can obtain food, food stability, food availability, food deserts, rurality, agriculture and food production).

Healthcare system factors/characteristics refers to access to quality, affordable, and timely preventive and curative health care that recognizes individual patient needs, including their health history and personal preferences.

Power/Prestige refers to an imbalance in status and opportunities between populations based on factors such as race and ethnicity, gender, income, or sexual orientation.

Social context/environment are factors and circumstances in the broader social setting (such as exposure to community stressors or personal/life experiences) that shape behaviors, beliefs, and/or perceptions of individuals and groups of people.

When comparing to injury topic areas, 23 (39.0%) SDOHs/individual factors related to TBI, thirteen (22.0%) were related to motor vehicle crashes and suicide, and 11 (18.6%) were related to drowning and older adult falls (Table 4) (CDC NCIPC, 2021). Four domains were most relevant to suicide and TBI (Economic Stability, Health Care Access and Quality, Social and Community Context, and Neighborhood and Built Environment), three for falls (Economic Stability, Social and Community Context, and Neighborhood and Built Environment) and two were found most relevant for both motor vehicle and drowning (Social and Community Context and Neighborhood and Built Environment).

Table 4.

Social determinants of health and individual factors identified in health equity frameworksa Cateogorized by the healthy people 2030 key domains limited to injury topic areas.b,c

| HP 2030 Key Domain | Social Determinants of Health (SDOHs) and Individual Factorsd (n =29) | Drowning | Motor vehicle crashes | Older adult falls | Suicide | Traumatic brain injury |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Economic Stability | Occupation/employment | X | ||||

| Economic security | X | |||||

| Employment status | X | |||||

| Employment class | X | |||||

| Housing | X | |||||

| Income | X | |||||

| Income inequality | X | |||||

| Socioeconomic status | X | |||||

| Health Care Access and Quality | Disability status | X | ||||

| Health insurance status | X | |||||

| Neighborhood and Built Environment | Geography | X | X | X | X | X |

| Residential location/neighborhood | X | X | X | X | ||

| Drug/alcohol misuse | X | X | ||||

| Safetye | X | |||||

| Transportation (including traffic) | X | |||||

| Violence | X | |||||

| Social and Community Context | Age | X | X | X | X | X |

| Minority status | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Nativity/country of origin | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Power/prestigee | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Race/ethnicity | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Racism/ discrimination | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Segregation | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Immigration/refugee status | X | X | X | X | ||

| Sex | X | X | X | |||

| Veteran status | X | X | ||||

| Sexual orientation | X | |||||

| Crime | X | |||||

| Social context/environmente | X | |||||

| TOTAL (%) (N = 59) | 11 (18.6) | 13 (22.0) | 11 (18.6) | 13 (22.0) | 23 (39.0) | |

Includes health equity frameworks found in Table 1.

SDOHs and individual factors included in the table above contribute to health disparities in the following injury topic areas: drowning, motor vehicle crashes, older adult falls, suicide, and traumatic brain injury (TBI). This does not mean that other SDOHs and individual risk factors do not contribute to health disparities in these injury topic areas; however, the SDOHs and individual factors above are the factors highlighted as influencing injury outcomes in the United States, according to CDC webpages:

Motor vehicle crashes: https://www.cdc.gov/transportationsafety/.

Older adult falls: https://www.cdc.gov/falls/facts.html.

None of the factors listed in the CDC websites for the injury topics fit under the Education Access and Quality domain; therefore, this domain is not included in the table.

Social determinants of health (SDOHs) and individual factors include the individual, social, economic, and environmental factors that influence the health and well-being of individuals and communities.

Definitions for select terms:

Power/prestige refers to an imbalance in status and opportunities between populations based on factors such as race and ethnicity, gender, income, or sexual orientation.

Safety includes injury deaths, juvenile arrests, and the general state of feeling “safe”.

Social context/environment are factors and circumstances in the broader social setting (such as exposure to community stressors or personal/life experiences) that shape behaviors, beliefs, and/or perceptions of individuals and groups of people.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind to assess SDOH and individual factor coverage within existing health equity frameworks and assess applicability of these frameworks to injury topic areas. SDOHs and individual factors by injury topic area were analyzed to demonstrate how health equity frameworks that incorporate these factors may align with injury outcomes through comparison with topic-specific health disparities. To understand commonalities between SDOHs and individual factors abstracted from the health equity frameworks, this study used the HP 2030 key domains. The HP 2030 key domains have ties to injury-related outcomes. For example, one of the HP 2030 Neighborhood and Built Environment objectives is to reduce the rate of minors and young adults committing violent crimes (Department of Health and Human Services, 2022). Frameworks reviewed in this study addressed different types of SDOHs and individual factors, which may make them more or less suitable for application to injury topic areas (Department of Health and Human Services, 2022).

The SDOHs and individual factors identified in the health equity frameworks varied across the HP 2030 key domains. As shown in Fig. 1, the Social and Community Context and Neighborhood and Built Environment key domains had more coverage compared to the Economic Stability, Health Care Access and Quality, and Education Access and Quality key domains. One potential reason for this may be because this study used a best fit model, meaning that each SDOH and individual factor was categorized into one of the five HP 2030 key domains and overlap between domains was not assessed. Another potential reason may be that some SDOHs and individual factors such as age, genetic predictors, and environmental factors, which are part of the Neighborhood and Built Environment and Social and Community Context key domains, are more commonly included in health equity frameworks compared to SDOHs and individual factors found in other domains. Eight frameworks in the study covered all five of the HP 2030 key domains. These frameworks appear to be most universally applicable for conceptualizing health equity broadly based on alignment with the HP 2030 key domains. However, the SDOHs and individual factors found to be relevant to the suicide and TBI topic areas appeared in all but the Education Access and Quality domain, so additional frameworks that did not cover the Education Access and Quality key domain could be considered, such as A Public Health Framework for Reducing Health Inequities, the health equity measurement framework, World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model, the Multi-level Systems Approach, Pathways Model, PROGRESS/PROGRESS Plus, Rural Community Health and Well-Being Framework, social determinants of child health, and the WHO Social Political, Economic and Cultural Conceptual Model. For falls, the Weathering Hypothesis and social and demographic determinants of health-related quality of life could be considered as well, since these frameworks cover the three key domains identified for falls. Additionally, the Community Stress Theory and the framework for understanding racial/ethnic disparities in environmental health could be considered for motor vehicle and drowning.

The health equity field is constantly evolving and expanding, making relationships between terms difficult to comprehend and apply to research. However, incorporating health equity frameworks into research is important for understanding and contextualizing the underlying drivers of health disparities. The application of health equity frameworks in research may be an effective strategy to help researchers evaluate and conceptualize why health outcomes may differ between populations, which can lead to more tailored upstream prevention strategies and progress towards health equity (Braveman et al., 2017). The findings from this study may serve as a useful tool for researchers in injury and other public health fields to reference and utilize when considering health equity frameworks to include in their disparities-focused research.

5. Limitations

There are a few limitations to this study. This study utilized a compilation of health equity frameworks that were identified from a limited number of sources (e.g., PubMed, CINAHL) (Lennon et al., 2022). Therefore, additional health equity frameworks found in other citation databases or resources may have been excluded. The authors added the SDOHs and individual factors into the five key domains recommended by HP 2030 using a best fit model; therefore, some SDOHs and individual factors may have overlapped into other key domains, and instances of potential overlap were not reported in the study. Given that the health equity frameworks used in this study were developed and used at different points in time in the past decades, terminology for describing the same SDOHs and individual factors may have varied over time, which could have caused an increase in number of SDOHs and individual factors reported. Additionally, the CDC webpages that were used to determine health disparities for injury topic areas to compare to underlying SDOHs and individual factors did not necessarily mention all health disparities that are present within the topic areas, which could have led to the exclusion of other SDOHS and individual factors when determining applicability of health equity frameworks to injury topic areas.

6. Conclusions

The importance of incorporating health equity into the public health field, including injury, is critical. Health equity frameworks can provide a way for those in the fields of research, implementation, translation, and program development to incorporate health equity into their research. During this process, it is important to note which SDOHs and individual factors are covered by the frameworks and how these apply to specific fields of research. This study adds to the existing literature by identifying SDOHs and individual factors addressed by 33 health equity frameworks used in the literature and providing a tool for researchers to begin identifying health equity frameworks that can be applied to their work. The findings from this study could be used to develop a health equity framework for specific injury topic areas or other public health areas. Further research may observe how frameworks can be applied to new and existing injury research, using SDOHs and individual factors as a guide to select the most fitting framework based on the populations most disproportionately affected by injury outcomes.

7. Practical Applications

Health equity frameworks are a practical tool to guide injury research, translation, evaluation, and program implementation. The findings from this study can be used to guide the application of health equity frameworks in injury research for specific topic areas. Moving forward, researchers may use these findings to develop and apply health equity frameworks that address the specific SDOHs and individual factors most relevant to framing and understanding health equity in injury prevention.

Acknowledgments

The Journal of Safety Research has partnered with the Office of the Associate Director for Science, Division of Injury Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control at the CDC in Atlanta, Georgia, USA, to briefly report on some of the latest findings in the research community. This report is the 75th in a series of “Special Report from the CDC” articles on injury prevention.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Biography

Andrea Carmichael, MPH graduated from George Mason University in 2018 with her MPH in Epidemiology and completed her practicum at the EPA’s Office of Children’s Health protection. She is currently a Health Scientist for the Division of Injury Prevention in the CDC’s Injury Center, where she has presented and published on various injury topics including health equity, suicide prevention, drug overdose, and nonfatal injury data. She completed two COVID-19 response deployments, which involved monitoring and reporting cases among the general population and among people experiencing homelessness.

Natalie Lennon, MPH graduated from Emory University in 2021 with her MPH in Behavioral, Social, and Health Education Sciences. She currently works on the Suicide Prevention Team in the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In her current role, Natalie serves as a suicide subject matter expert for CDC’s Comprehensive Suicide Prevention Program and conducts research focused on suicide and suicidal behaviors among disproportionally affected groups.

Judy Qualters, PhD, MPH is the director of the Division of Injury Prevention (DIP) in the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC) at CDC. In this role, Dr. Qualters provides leadership to bridge science and practice in an effort to move the field of violence and injury prevention forward. She also leads a diverse portfolio of work that includes surveillance, data and economic analysis, information technology, policy research, evaluation, and technical assistance to state health departments.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Abbott LS, & Williams CL (2015). Influences of social determinants of health on African Americans living with HIV in the rural southeast: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 26(4), 340–356. 10.1016/j.jana.2015.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S, Chase LE, Wagnild J, Akhter N, Sturridge S, Clarke A, Chowdhary P, Mukami D, Kasim A, & Hampshire K. (2022). Community health workers and health equity in low- and middle-income countries: Systematic review and recommendations for policy and practice. International Journal for Equity in Health, 21(1), 49. 10.1186/s12939-021-01615-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen LN, Smith RW, Simmons-Jones F, Roberts N, Honney R, & Currie J. (2020). Addressing social determinants of noncommunicable diseases in primary care: A systematic review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 98(11), 754–765B. 10.2471/BLT.19.248278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstead TL, Wilkins N, & Nation M. (2021). Structural and social determinants of inequities in violence risk: A review of indicators. Journal of Community Psychology, 49(4), 878–906. 10.1002/jcop.22232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aves T, Kredo T, Welch V, Mursleen S, Ross S, Zani B, Motaze NV, Quinlan L, & Mbuagbaw L. (2017). Equity issues were not fully addressed in Cochrane human immunodeficiency virus systematic reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 81, 96–100. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista R, Pottie K, Bouchard L, Ng E, Tanuseputro P, & Tugwell P. (2018). Primary health care models addressing health equity for immigrants: A systematic scoping review. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 20(1), 214–230. 10.1007/s10903-016-0531-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhojani U, Madegowda C, Prashanth NS, Hebbar P, Mirzoev T, Karlsen S, & Mir G. (2019). Affirmative action, minorities, and public services in India: Charting a future research and practice agenda. Indian Journal of Medical Ethics, 4(4), 265–273. 10.20529/ijme.2019.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers R, Turner G, Graham ID, Furgal C, & Dubois L. (2020). Piecing together the Labrador Inuit food security policy puzzle in Nunatsiavut, Labrador (Canada): A scoping review. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 79(1), 1799676. 10.1080/22423982.2020.1799676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P. (1998). Monitoring equity in health: A policy-oriented approach in low- and middle-income countries. Geneva: Department of Health Systems, World Health Organization. [Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/65228]. [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P, Arkin E, Orleans T, Proctor D, & Plough A. (2017). What is Health Equity? And What Difference Does a Definition Make? [Available from: https://resources.equityinitiative.org/handle/ei/418]. [Google Scholar]

- Brown CR, Hambleton IR, Sobers-Grannum N, Hercules SM, Unwin N, Nigel Harris E, Wilks R, MacLeish M, Sullivan L, Murphy MM, & Caribbean US Alliance for Health Disparities Research Group (USCAHDR). (2017a). Social determinants of depression and suicidal behaviour in the Caribbean: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 577. 10.1186/s12889-017-4371-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CR, Hambleton IR, Hercules SM, Alvarado M, Unwin N, Murphy MM, Harris EN, Wilks R, MacLeish M, Sullivan L, & Sobers-Grannum N. (2017b). Social determinants of breast cancer in the Caribbean: A systematic review. International Journal of Equity in Health, 16(1), 60. 10.1186/s12939-017-0540-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttazzoni A, Veenhof M, & Minaker L. (2020). Smart city and high-tech urban interventions targeting human health: An equity-focused systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health, 17(7). 10.3390/ijerph17072325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Matos I, Russo G, & Perelman J. (2016). Connecting the dots on health inequalities–a systematic review on the social determinants of health in Portugal. International Journal of Equity in Health, 15, 26. 10.1186/s12939-016-0314-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER) [online]. (2021). Accessed May 15, 2023. [Available from: https://wonder.cdc.gov/].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (2022). Health Equity. Accessed May 16, 2023. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/healthequity/index.htm].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (2022a). The Social-Ecological Model: A Framework for Prevention. Accessed May 16, 2023. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/social-ecologicalmodel.html]. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention Control (2022b). Drowning Facts. Accessed May 16, 2023. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/drowning/facts/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office of Minority Health & Health Equity (2022). What is Health Equity? Accessed May 16, 2023. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/healthequity/whatis/index.html]. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (2023a). Disparities in Suicide. Accessed May 16, 2023. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/disparities-in-suicide.html].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (2023b). Facts About Falls. Accessed May 16, 2023. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/falls/facts.html].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (2023c). Health Disparities and TBI. Accessed May 16, 2023. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/health-disparities-tbi.html].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (2023d). Transportation Safety. Accessed May 16, 2023. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/transportationsafety/].

- Chandler CE, Williams CR, Turner MW, & Shanahan ME (2022). Training public health students in racial justice and health equity: A systematic review. Public Health Report, 137, 375–385. 10.1177/00333549211015665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Tan X, & Padman R. (2020). Social determinants of health in electronic health records and their impact on analysis and risk prediction: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 27(11), 1764–1773. 10.1093/jamia/ocaa143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhibber A, Kharat A, Kneale D, Welch V, Bangpan M, & Chaiyakunapruk N. (2021). Assessment of health equity consideration in masking/PPE policies to contain COVID-19 using PROGRESS-plus framework: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1682. 10.1186/s12889-021-11688-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christidis R, Lock M, Walker T, Egan M, & Browne J. (2021). Concerns and priorities of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples regarding food and nutrition: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. International Journal of Equity in Health, 20(1), 220. 10.1186/s12939-021-01551-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn T, & Harrison CV (2022). A systematic review exploring racial disparities, social determinants of health, and sexually transmitted infections in Black women. Nursing for Women’s Health, 26, 128–142. 10.1016/j.nwh.2022.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lima Silva V, Cesse E, & de Albuquerque MF (2014). Social determinants of death among the elderly: A systematic literature review. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia, 17(Suppl 2), 178–193. 10.1590/1809-4503201400060015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services (2022). Healthy People 2030. Accessed March 14, 2023. [Available from: https://wwwhttps://health.gov/healthypeople].

- Diez Roux AV (2012). Conceptual approaches to the study of health disparities. Annual Review of Public Health, 33, 41–58. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dover DC, & Belon AP (2019). Correction to: The health equity measurement framework: A comprehensive model to measure social inequities in health. International Journal of Equity in Health, 18(1), 58. 10.1186/s12939-019-0949-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressler W, Oths K, & Gravlee C. (2005). Race and ethnicity in public health research: Models to explain health disparities. Annual Reviews, 34, 231–252. 10.1146/annurev.anthro.34.081804.120505 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll DL, Dotterrer B, & Brown RA, 2nd (2013). Assessing the social and physical determinants of circumpolar population health. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 72. 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forde AT, Crookes DM, Suglia SF, & Demmer RT (2019). The weathering hypothesis as an explanation for racial disparities in health: A systematic review. Annals of Epidemiology, 33, 1–18.e3. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, & Payne-Sturges DC (2004). Environmental health disparities: A framework integrating psychosocial and environmental concepts. Environmental Health Perspectives, 112(17), 1645–1653. 10.1289/ehp.7074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiasvand H, Higgs P, Noroozi M, Ghaedamini Harouni G, Hemmat M, Ahounbar E, Haroni J, Naghdi S, Nazeri Astaneh A, & Armoon B. (2020). Social and demographical determinants of quality of life in people who live with HIV/AIDS infection: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Biodemography and Social Biology, 65(1), 57–72. 10.1080/19485565.2019.1587287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum VJ, Titchen K, Walker-Descartes I, Feifer A, Rood CJ, & Fong HF (2018). Multi-level prevention of human trafficking: The role of health care professionals. Prevention Medicine, 114, 164–217. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habbab RM, & Bhutta ZA (2020). Prevalence and social determinants of overweight and obesity in adolescents in Saudi Arabia: A systematic review. Clinical Obesity, 10 (6), e12400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karger S, Bull C, Enticott J, & Callander EJ (2022). Options for improving low birthweight and prematurity birth outcomes of indigenous and culturally and linguistically diverse infants: A systematic review of the literature using the social-ecological model. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 22(1), 3. 10.1186/s12884-021-04307-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegler SR, Stone DM, Mercy JA, & Dahlberg LL (2022). Firearm homicides and suicides in major metropolitan areas - United States, 2015–2016 and 2018–2019. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 71(1), 14–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendi S, & Macy ML (2023). The injury equity framework - establishing a unified approach for addressing inequities. New England Journal of Medicine, 388(9), 774–776. 10.1056/NEJMp2212378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehne G, & Bolte G. (2017). Impact of universal interventions on social inequalities in physical activity among older adults: An equity-focused systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral and Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1), 20. 10.1186/s12966-017-0472-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon NH, Carmichael AE, & Qualters JR (2022). Health equity guiding frameworks and indices in injury: A review of the literature. Journal of Safety Research, 82, 469–481. 10.1016/j.jsr.2022.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenc T, Tyner EF, Petticrew M, Duffy S, Martineau FP, Phillips G, & Lock K. (2014). Cultures of evidence across policy sectors: Systematic review of qualitative evidence. European Journal of Public Health, 24(6), 1041–1047. 10.1093/eurpub/cku038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund C, Brooke-Sumner C, Baingana F, Baron EC, Breuer E, Chandra P, Haushofer J, Herrman H, Jordans M, Kieling C, Medina-Mora ME, Morgan E, Omigbodun O, Tol W, Patel V, & Saxena S. (2018). Social determinants of mental disorders and the Sustainable Development Goals: A systematic review of reviews. Lancet Psychiatry, 5(4), 357–369. 10.1016/s2215-0366(18)30060-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malele-Kolisa Y, Yengopal V, Igumbor J, Nqcobo CB, & Ralephenya TRD (2019). Systematic review of factors influencing oral health-related quality of life in children in Africa. African Journal of Primary Health Care and Family Medicine, 11(1), e1–e12. 10.4102/phcfm.v11i1.1943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maness SB, & Buhi ER (2016). Associations between social determinants of health and pregnancy among young people: A systematic review of research published during the past 25 years. Public Health Report, 131(1), 86–99. 10.1177/003335491613100115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GF, Daugherty J, Waltzman D, & Sarmiento K. (2021). Predictors of traumatic brain injury morbidity and mortality: Examination of data from the national trauma data bank: Predictors of TBI morbidity & mortality. Injury, 52(5), 1138–1144. 10.1016/j.injury.2021.01.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min LY, Islam RB, Gandrakota N, & Shah MK (2022). The social determinants of health associated with cardiometabolic diseases among Asian American subgroups: A systematic review. BMC Health Service Research, 22(1), 257. 10.1186/s12913-022-07646-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan G, & Chattopadhyay S. (2020). Cost-effectiveness of leveraging social determinants of health to improve breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical AssociationOncolology, 6(9), 1434–1444. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.1460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton RL, Schlackow I, Mihaylova B, Staplin ND, Gray A, & Cass A. (2016). The impact of social disadvantage in moderate-to-severe chronic kidney disease: An equity-focused systematic review. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, 31(1), 46–56. 10.1093/ndt/gfu394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreland B, Ortmann N, & Clemens T. (2022). Increased unintentional drowning deaths in 2020 by age, race/ethnicity, sex, and location, United States. Journal of Safety Research, 82, 463–468. 10.1016/j.jsr.2022.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2016). A Framework for Educating Health Professionals to Address the Social Determinants of Health. National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nooh F, Crump L, Hashi A, Tschopp R, Schelling E, Reither K, Hattendorf J, Ali SM, Obrist B, Utzinger J, & Zinsstag J. (2019). The impact of pastoralist mobility on tuberculosis control in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Infectious Diseases of Poverty, 8(1), 73. 10.1186/s40249-019-0583-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owusu-Addo E, Renzaho AM, Mahal AS, & Smith BJ (2016). The impact of cash transfers on social determinants of health and health inequalities in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review protocol. Systematic Reviews, 5(114). 10.1186/s13643-016-0295-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne-Sturges D, & Gee GC (2006). National environmental health measures for minority and low-income populations: Tracking social disparities in environmental health. Environmental Research, 102(2), 154–171. 10.1016/j.envres.2006.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne-Sturges D, Zenick H, Wells C, & Sanders W. (2006a). We cannot do it alone: Building a multi-systems approach for assessing and eliminating environmental health disparities. Environmental Research, 102(2), 141–145. 10.1016/j.envres.2006.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne-Sturges D, Gee GC, Crowder K, Hurley BJ, Lee C, Morello-Frosch R, Rosenbaum A, Schulz A, Wells C, Woodruff T, & Zenick H. (2006b). Workshop summary: Connecting social and environmental factors to measure and track environmental health disparities. Environmental Research, 102(2), 146–153. 10.1016/j.envres.2005.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira M, Padez CMP, & Nogueira H. (2019). Describing studies on childhood obesity determinants by Socio-Ecological Model level: A scoping review to identify gaps and provide guidance for future research. International Journal of Obesity (London), 43(10), 1883–1890. 10.1038/s41366-019-0411-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson A, Charles V, Yeung D, & Coyle K. (2021). The health equity framework: A science- and justice-based model for public health researchers and practitioners. Health Promotion Practice, 22(6), 741–746. 10.1177/1524839920950730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirkis J, Gunnell D, Hawton K, Hetrick S, Niederkrotenthaler T, Sinyor M, Yip P, & Robinson J. (2023). A public health, whole-of-government approach to national suicide prevention strategies. Crisis, 44(2), 85–92. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajmil L, Hjern A, Spencer N, Taylor-Robinson D, Gunnlaugsson G, & Raat H. (2020). Austerity policy and child health in European countries: A systematic literature review. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 564. 10.1186/s12889-020-08732-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reno R, & Hyder A. (2018). The evidence base for social determinants of health as risk factors for infant mortality: A systematic scoping review. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 29(4), 1188–1208. 10.1353/hpu.2018.0091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restar AJ, Sherwood J, Edeza A, Collins C, & Operario D. (2021). Expanding gender-based health equity framework for transgender populations. Transgender Health, 6(1), 1–4. 10.1089/trgh.2020.0026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgado M, Madureira J, Mendes AS, Torres A, Teixeira JP, & Oliveira MD (2020). Environmental determinants of population health in urban settings. A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 853. 10.1186/s12889-020-08905-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröders J, Wall S, Kusnanto H, & Ng N. (2015). Millennium development goal four and child health inequities in Indonesia: A systematic review of the literature. PLoS One, 10(5), e0123629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schüz B, Meyerhof H, Hilz LK, & Mata J. (2021). Equity effects of dietary nudging field experiments: Systematic review. Frontier Public Health, 9, 668998. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.668998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw KM, West B, Kendi S, Zonfrillo MR, & Sauber-Schatz E. (2022). Urban and Rural Child Deaths from Motor Vehicle Crashes: United States, 2015–2019. The Journal of Pediatrics, 250, 93–99. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol R, Austin A, Chandler C, Byrum E, Bousquette J, Lancaster C, Doss G, Dotson A, Urbaeva V, Singichetti B, Brevard K, Wright ST, Lanier P, & Shanahan M. (2019). Screening children for social determinants of health: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 144(4), e20191622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone D, Trinh E, Zhou H, Welder L, End of Horn P, Fowler K, & Ivey-Stephenson A. (2022). Suicides among American Indian or Alaska Native persons — National Violent Death Reporting System, United States, 2015–2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 71(37), 1161–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taggart T, Milburn NG, Nyhan K, & Ritchwood TD (2020). Utilizing a life course approach to examine HIV risk for Black adolescent girls and young adult women in the United States: A systematic review of recent literature. Ethnic Disparities, 30(2), 277–286. 10.18865/ed.30.2.277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J, & Lamaro Haintz G. (2018). Influence of the social determinants of health on access to healthcare services among refugees in Australia. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 24(1), 14–28. 10.1071/PY16147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulier ME, Reid C, Mujahid MS, & Allen AM (2019). “Clear action requires clear thinking“: A systematic review of gentrification and health research in the United States. Health & Place, 59, 102173. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull S, Cabral C, Hay A, & Lucas PJ (2020). Health equity in the effectiveness of web-based health interventions for the self-care of people with chronic health conditions: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(6), e17849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hees SGM, O’Fallon T, Hofker M, Dekker M, Polack S, Banks LM, & Spaan E. (2019). Leaving no one behind? Social inclusion of health insurance in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. International Journal of Equity in Health, 18(1), 134. 10.1186/s12939-019-1040-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang E, Glazer KB, Howell EA, & Janevic TM (2020). Social determinants of pregnancy-related mortality and morbidity in the United States: A systematic review. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 135(4), 896–915. 10.1097/aog.0000000000003762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch V, Tugwell P, Petticrew M, de Montigny J, Ueffing E, Kristjansson B, McGowan J, Benkhalti Jandu M, Wells GA, Brand K, & Smylie J. (2010). How effects on health equity are assessed in systematic reviews of interventions. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1(1), R000028. 10.1002/14651858.MR000028.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward E, Singh R, Ndebele-Ngwenya P, Melgar Castillo A, Dickson K, & Kirchner J. (2021). A more practical guide to incorporating health equity domains in implementation determinant frameworks. Implementation Science Communications, 2(1), 61. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-32704/v2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2017). Determinants of health. Accessed August 30, 2023. [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/determinants-of-health].

- Wulz AR, Miller GF, Kegler SR, Yard EE, & Wolkin AF (2022). Assessing female suicide From a health equity viewpoint, U.S. 2004–2018. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 63(4), 486–495. 10.1016/j.amepre.2022.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yelton B, Friedman DB, Noblet S, Lohman MC, Arent MA, Macauda MM, Sakhuja M, & Leith KH (2022). Social determinants of health and depression among African American adults: A scoping review of current research. International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health, 19(3). 10.3390/ijerph19031498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yiga P, Seghers J, Ogwok P, & Matthys C. (2020). Determinants of dietary and physical activity behaviours among women of reproductive age in urban sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. British Journal of Nutrition, 124(8), 761–772. 10.1017/s0007114520001828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahnd WE, & McLafferty SL (2017). Contextual effects and cancer outcomes in the United States: A systematic review of characteristics in multilevel analyses. Annals of Epidemiology, 27(11), 739–748.e3. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2017.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]