Abstract

Under aerobic conditions Bacillus subtilis utilizes a branched electron transport chain comprising various cytochromes and terminal oxidases. At present there is evidence for three types of terminal oxidases in B. subtilis: a caa3-, an aa3-, and a bd-type oxidase. We report here the cloning of the structural genes (cydA and cydB) encoding the cytochrome bd complex. Downstream of the structural genes, cydC and cydD are located. These genes encode proteins showing similarity to bacterial ATP-binding cassette (ABC)-type transporters. Analysis of isolated cell membranes showed that inactivation of cydA or deletion of cydABCD resulted in the loss of spectral features associated with cytochrome bd. Gene disruption experiments and complementation analysis showed that the cydC and cydD gene products are required for the expression of a functional cytochrome bd complex. Disruption of the cyd genes had no apparent effect on the growth of cells in broth or defined media. The expression of the cydABCD operon was investigated by Northern blot analysis and by transcriptional and translational cyd-lacZ fusions. Northern blot analysis confirmed that cydABCD is transcribed as a polycistronic message. The operon was found to be expressed maximally under conditions of low oxygen tension.

The gram-positive soil bacterium Bacillus subtilis is able to grow with various substrates as carbon sources, and it can use oxygen or nitrate as terminal electron acceptors. During aerobic respiration B. subtilis utilizes a branched electron transport chain comprising various cytochromes and terminal oxidases (52). At present there is biochemical and genetic evidence for three types of terminal oxidases in B. subtilis: a caa3-, an aa3-, and a bd-type oxidase (52). The first of these probably functions as a cytochrome c oxidase, whereas the latter two use menaquinol as a substrate (32). Both a-type oxidases are members of the well-characterized heme-copper superfamily of terminal oxidases (11). The cytochrome bd complex is unrelated to this superfamily (25). In addition, some B. subtilis strains seem to express a CO binding b-type cytochrome that may function as a terminal oxidase (50). The composition of the aerobic respiratory chain depends on the growth conditions (52). The flexibility of the energy-generating machinery may be one important factor that enables free-living bacteria such as B. subtilis to cope with the variation in oxygen and nutrient supply that is a common characteristic of their natural environment.

Cytochrome bd is a widely distributed prokaryotic terminal oxidase present in Archaea and Bacteria (25, 29). Most studies on this oxidase have been carried out on the enzymes from Azotobacter vinelandii and Escherichia coli. The E. coli cytochrome bd-type quinol oxidase comprises three spectroscopically distinct cytochromes (b558, b595, and d) and contains two subunits (28, 34). The E. coli cydA and cydB genes form one operon, which encodes the two polypeptide subunits of the cytochrome bd complex (16). Two additional genes, cydC and cydD, encoding a heterodimeric ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter, are required for proper assembly of the E. coli cytochrome bd-type quinol oxidase (12, 39).

Relatively few data are available on cytochrome bd in B. subtilis or in gram-positive bacteria in general. However, cytochrome bd has recently been isolated from the facultative alkaliphile Bacillus firmus OF4 (13) and from the thermophile Bacillus stearothermophilus (41). In these bacteria, cytochrome bd has been detected only in mutant strains lacking the caa3-type terminal oxidase.

To further characterize the terminal segment of the respiratory chain of B. subtilis, we have isolated and analyzed a gene cluster, designated cyd (43), that includes the structural genes, cydA and cydB, for the cytochrome bd terminal oxidase. Downstream of the structural genes, cydC and cydD are located. The latter genes encode proteins showing similarity to bacterial ABC-type transporters. Using gene disruption experiments, we have shown that the cydC and cydD gene products are required for the production of a functional cytochrome bd complex. We also show that the cydABCD genes form an operon transcribed as one polycistronic message and that expression of this operon is influenced by, e.g., oxygen tension.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Plasmids used in this work are shown in Fig. 1 or are described in the text. B. subtilis strains were grown at 37°C in nutrient sporulation medium with phosphate (NSMP) (10), in NSMP supplemented with 0.5% glucose (NSMPG), in DSM (43), in DSM supplemented with 0.5% glucose, or in minimal glucose medium (23, 46). Tryptose blood agar base medium (TBAB) (Difco) was used for growth of bacteria on plates. Either L broth, L agar, or 2× YT (42) was used for growth of E. coli strains. The following antibiotics were used when required: chloramphenicol (5 μg/ml), kanamycin (5 μg/ml), tetracycline (15 μg/ml), and a combination of erythromycin (0.5 μg/ml) and lincomycin (12.5 μg/ml) for B. subtilis strains, and ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (12.5 μg/ml) for E. coli strains.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used

| Strain | Relevant characteristics | Source or referencea |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| MM294 | endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 thi-1 | Laboratory stock |

| XL1-Blue | endA1 gyrA96 thi hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 relA1 lac/F′ proAB lacIqlacZΔM15 Tn10 | Stratagene, Inc. |

| C600 | supE44 hsdR thi-1 leuB6 lacY1 tonA21 | Stratagene, Inc. |

| B. subtilis | ||

| 1A1 | trpC2 | BGSCb |

| 1A771 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::ery | BGSC |

| 168A | trpC2 | Laboratory stockc |

| JO1 | trpC2 ΔctaCD::ble | 49 |

| Δqox | trpC2 galT ΔqoxABCD::kan | 50 |

| CydAd | trpC2 cydA::pCYDAd (cydA′-lacZ) | pCYDAd→1A1 |

| CydBd | trpC2 cydB::pCYDBd (cydAB′-lacZ) | pCYDBd→1A1 |

| CydCd | trpC2 cydC::pCYDCd (cydABC′-lacZ) | pCYDCd→1A1 |

| CydDd | trpC2 cydD::pCYDDd (cydABCD′-lacZ) | pCYDDd→1A1 |

| LUH15 | trpC2 ΔctaCD::ble | JO1→168A |

| LUH17 | trpC2 galT ΔctaCD::ble ΔqoxABCD::kan | Δqox→LUH15 |

| LUW3 | trpC2 cydA::pCYDcat | pCYDcat→168A |

| LUW9 | trpC2 cydD::pCYD12 | pCYD12→168A |

| LUW10 | trpC2 ΔcydABCD::cat | pCYD13→168A |

| LUW20 | trpC2 ΔcydABCD::tet | pCYD14→168A |

| LUW48 | trpC2 amyE::pCydLacZ1 (cydA′-lacZ) | pCydLacZ1→1A1 |

| LUW98 | trpC2 amyE::ery | 1A771→1A1 |

Arrows indicate transformation and point from donor DNA to recipient strain.

BGSC, Bacillus Genetic Stock Center, Department of Biochemistry, Ohio State University, Columbus.

This isolate of strain 168 was found to be oligosporogenic.

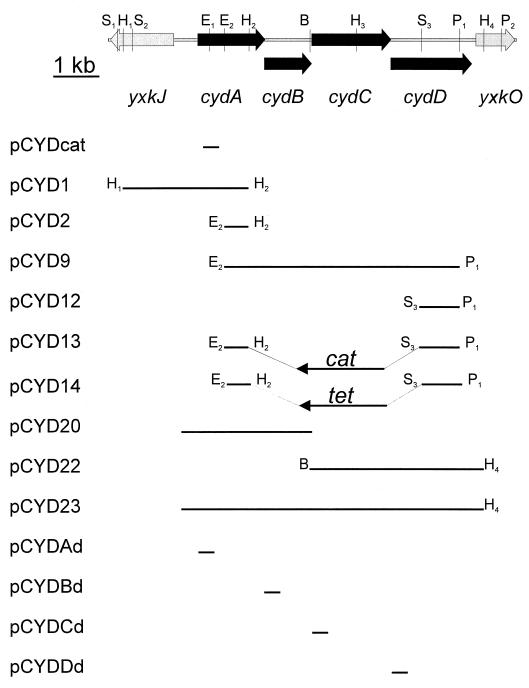

FIG. 1.

Restriction map of the B. subtilis cyd region and plasmids carrying different parts of this region. The sequence of this region was determined previously (54). The cyd genes are oriented in the same direction as replication of the B. subtilis chromosome. The insert carried by each plasmid is shown as a solid line. Restriction sites used for subcloning fragments of the cyd region are abbreviated as follows: B, BspEI; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; P, PstI; S, SphI. Plasmids pCYD1 and pCYD2 are derivatives of pBluescript II KS(−) (Stratagene, Inc.); plasmid pCYDcat is a derivative of pT7Blue(R) (Novagen) that contains the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene of pHV32 (35) on a 2,000-bp HindIII-SalI fragment; plasmid pCYD9 is a derivative of pUC18 (53); plasmids pCYD12 and pCYD13 are derivatives of pHV32; pCYD20, pCYD22, and pCYD23 are derivatives of the E. coli/B. subtilis shuttle vector pHP13 (19); pCYD14 is a derivative of pCYD13 in which the cat gene (HindIII-BamHI) has been replaced with the tet gene of plasmid pDG1515 (carried on a 2,142-bp HindIII-BamHI fragment) (18); pCydAd, pCydBd, pCydCd, and pCydDd are derivatives of pMutin2 (lacZ lacI amp ery) (48).

Batch cultures of B. subtilis LUW48 were grown in a bioreactor fitted with a 3-liter vessel and operated at a 2-liter working volume. The degree of air saturation was varied by manipulating the stirring and the flow of air.

DNA manipulations.

Procedures for plasmid isolation, agarose gel electrophoresis, use of restriction and DNA modification enzymes, DNA ligation, Southern blot analysis, and PCR were performed according to standard protocols (42). B. subtilis chromosomal DNA was isolated by a published procedure (23). Preparation of electroporation-competent E. coli cells and plasmid transformation of E. coli strains with a GenePulser apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories) were performed as described elsewhere (20). Transformation of B. subtilis by chromosomal or plasmid DNA was performed as described by Hoch (23). DNA probes were radiolabeled with [α-32P]dCTP by using the Rediprime DNA labeling system (Amersham) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Kyte-Doolittle (31) profiles were obtained with the software package pSAAM, written by A. R. Crofts (University of Illinois).

RNA techniques.

To isolate RNA, an overnight culture of B. subtilis 1A1 was inoculated into NSMP or NSMPG to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of about 0.05. The cultures were grown at 37°C with shaking. Cells (80 ml) were harvested at 2, 4, and 6 h after inoculation, corresponding to the exponential, deceleration, and stationary phases, respectively. RNA was isolated by using a modification of an established procedure (24). A 0.2-ml portion of a cell suspension in 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.4)–1 mM Na-EDTA–10 mM sodium iodoacetate was mixed with 0.5 ml of glass beads (diameter, 0.5 mm), 0.4 ml phenol, and 0.8 ml of a solution containing 0.6% cetyltrimethylammonium bromide, 50 mM sodium acetate, and 1 mM dithiothreitol. The cells were lysed by shaking with a Mini-Beadbeater apparatus (Biospec Products) for 1.5 min at 65°C. Following reextraction of the aqueous phase with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (125:24:1 by volume), RNA was recovered by precipitation with an equal volume of isopropanol in the presence of 0.3 M sodium acetate at 4°C. The RNA was precipitated a second time and then dissolved in 50 μl of water containing 10 U of RNase inhibitor (GIBCO BRL).

To identify the transcriptional initiation site of the cyd operon, 50 μg of each RNA was annealed to a primer (5′-TAGAACCGAGACTTTGATCAG-3′) that had been labeled at the 5′ end with T4 polynucleotide kinase (Megalabel; Takara Shuzo Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) and [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham). Primer extension reactions were performed as described previously (55).

For Northern blot analysis, RNA was electrophoresed in glyoxal gels and transferred to a Hybond-N membrane (Amersham) (42). The PCR product used in construction of strain CydAd was labeled with [α-32P]dCTP and used as a probe. Hybridization was carried out as described previously (42).

Cloning of the B. subtilis cyd locus.

The following procedure was used to clone the cyd region. From the sequences of subunit I of the cytochrome bd terminal oxidase from A. vinelandii (CydA), E. coli (CydA and AppC [also referred to as CbdA]), and Haemophilus influenzae (CydA), the consensus sequences FWGKLFGINFA and WIL(V/N)ANGWMQ (corresponding to residues 54 to 64 and 143 to 152 of the E. coli CydA subunit [16]) were derived. These sequences were used to design the degenerate oligonucleotides 5′-TGGGG(A/T/G/C)AA(A/G)(T/C)T(A/T/G/C)TT(T/C)GG(A/T/G/C)AT(A/T/C)AA(T/C) TT(T/C)GC-3′, used as the sense primer, and 5′-TGCATCCA(A/T/G/C)CC(A/G)TT(A/T/G/C)GC(A/T/G/C)(A/T)(T/C)(A/T/G/C)A(A/G)(A/G/C)ATCCA-3′, used as the antisense primer, for amplification of a B. subtilis gene fragment by PCR. The obtained PCR product was cloned in plasmid pT7Blue(R) (Novagen). The DNA sequence of the cloned 290-bp fragment was determined. It was found to encode part of a reading frame that showed significant similarity to the product of the E. coli cydA gene, which encodes subunit I of the cytochrome bd quinol oxidase. DNA from this plasmid, called pCYD, was radiolabeled with [α-32P]dCTP. Southern blot analysis showed that the labeled plasmid DNA hybridized to a 2,800-bp fragment of B. subtilis 1A1 DNA digested with HindIII. The labeled pCYD plasmid DNA was used as a probe to screen a library of B. subtilis 1A1 chromosomal DNA in E. coli XL1-Blue. The library contained HindIII chromosomal DNA fragments, of approximately 3,000 bp, inserted in the unique HindIII site of pBluescript II KS(−). Of approximately 1,500 clones, 2 gave positive signals. Plasmid DNA isolated from one positive clone was found to contain a 2,800-bp HindIII insert. The plasmid was designated pCYD1. E. coli XL1-Blue cells harboring this plasmid grew poorly, and only limited amounts of plasmid DNA could be recovered from the cells. By using a similar strategy, an additional region of the cyd locus was cloned in pCYD9 (Fig. 1). DNA sequencing showed that the cloned region corresponds to the previously reported nucleotide sequence of the B. subtilis cyd region (54).

Disruption of the cydA and cydD genes.

The cat gene from pHV32 (35) was isolated as a 2,000-bp HindIII-SalI fragment and cloned in pCYD, resulting in pCYDcat. The plasmids pCYDcat and pCYD12 (Fig. 1), carrying internal fragments of the cydA and cydD genes, respectively, were integrated into the chromosome of strain 168A via a single-crossover event disrupting the open reading frame of cydA or cydD. The insertion of the respective plasmid within the chromosomal cydA or cydD gene was confirmed by Southern blot analysis (data not shown).

Construction of a cydABCD null mutant.

To make a deletion-insertion mutant, a 500-bp EcoRI-HindIII fragment of pCYD2 corresponding to an internal part of cydA was ligated to pCYD12 that had been cut with the same enzymes. The resulting plasmid, pCYD13 (Fig. 1), was used to transform strain 168A to chloramphenicol resistance. The deletion-insertion within the chromosomal cydABCD genes arising from a double-crossover recombination event was confirmed by Southern blot analysis (data not shown). A cydABCD deletion-insertion strain with a tetracycline instead of a chloramphenicol resistance cassette was constructed by the same procedure, by replacing plasmid pCYD13 with pCYD14 (Fig. 1).

Construction of cyd-lacZ translational and transcriptional fusions.

A fragment containing part of cydA, bases −116 to +199 (relative to the cyd operon transcription start site), was amplified by PCR with oligonucleotides 5′-CCGGATCCTAGCAGCGGACATAAATAAG-3′ (BamHI site underlined) and 5′-CCGGATCCCACTCATGCTTTCTCCTCCATTTCC-3′ (BamHI site underlined) and was cloned into pBluescript II KS(−). The identity of the DNA fragment was verified by DNA sequencing. The fragment was then cloned into pMD431 (5), resulting in plasmid pCydLacZ1, which was subsequently integrated by double-crossover recombination at the amyE locus of the B. subtilis 1A1 chromosome by transformation of strain LUW98.

B. subtilis strains CydAd, CydBd, CydCd, and CydDd carrying transcriptional fusions of cydA, cydAB, cydABC, and cydABCD to lacZ, respectively, were constructed as follows. DNA fragments (approximately 350 bp) corresponding to internal parts of each of the cyd genes were amplified by PCR using specific primer pairs and chromosomal DNA of B. subtilis 1A1 as a template. The specific primers used for the constructions were as follows (restriction sites are underlined): for CydAd, 5′-GCCGAAGCTTTTCACTTCTTGTTTGTGCCG-3′ (HindIII) and 5′-GCGCAGATCTTCGTTCCGAATGATACGAGC-3′ (BglII); for CydBd, 5′-GCCGAAGCTTTTGGAAGGCTTTGATTTCGG-3′ (HindIII) and 5′-GCGCAGATCTCACAAACGGAGGAATTAGAC-3′ (BglII); for CydCd, 5′-GCCGAAGCTTGGAATGAAGCGGATTCTCAC-3′ (HindIII) and 5′-GCGCAGATCTACTGGCTGATGCCTTCCATC-3′ (BglII); and for CydDd, 5′-GCCGAAGCTTGCCTGTTCGTTCTGGTTATC-3′ (HindIII) and 5′-GCGCAGATCTCCTGCAAATGCTCAATATCC-3′ (BglII). Each of the PCR products was cleaved with HindIII and BglII and was then ligated with pMutin2 previously digested with HindIII and BamHI. Plasmid pMutin2 (lacZ lacI amp ery) replicates in E. coli but not in B. subtilis and carries an erythromycin resistance gene that is active in B. subtilis (48). In addition, pMutin2 carries a promoterless lacZ gene derived from E. coli that can be used as a reporter gene (48). The ligated DNAs were introduced into E. coli C600 by transformation. The identity of each of the PCR products cloned into pMutin2 was verified by DNA sequencing. The resulting plasmids, pCYDAd, pCYDBd, pCYDCd, and pCYDDd (Fig. 1), were used to transform B. subtilis 1A1 to erythromycin resistance. Correct integration of a single copy of each plasmid into the respective cyd gene through a single-crossover event was confirmed by Southern blot analysis. In these disruptants, the lacZ gene of pMutin2 is placed under the regulation of all upstream sequences, including the cyd promoter.

Overproduction of cytochrome bd in B. subtilis.

Plasmid pCYD20, containing the cydA and cydB genes under the control of their native promoter, was constructed as follows. The region of interest, −116 to +2601 (relative to the cyd operon transcription start site), was amplified by long-range PCR using DNA from B. subtilis 1A1 as a template and oligonucleotides 5′-CCGGATCCTAGCAGCGGACATAAATAAG-3′ (BamHI site underlined) and 5′-CCCCTGCAGTTAATAAGTCATAGGCTCCTTATGG-3′ (PstI site underlined). Long-range PCR was carried out by using the Expand High Fidelity PCR System (Boehringer Mannheim) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The PCR product was digested with BamHI and PstI and was then ligated with the shuttle vector pHP13 (19), which had previously been digested with BamHI and PstI. The ligate was used to transform B. subtilis 168A to chloramphenicol resistance. The plasmid isolated from these cells was called pCYD20. An intact pCYD20 cannot be maintained in E. coli XL1-Blue.

Plasmid pCYD23, containing the cydABCD operon under the control of the native promoter, was constructed as follows. The distal part of the cydD gene was amplified by PCR using chromosomal DNA from B. subtilis 1A1 as a template and oligonucleotides 5′-GAGCGCCAGCGGATCGCACTTGCG-3′ and 5′-CGTCACGCCAATAGGTCGCCTCGG-3′. The sequences of these oligonucleotides were based on the previously determined sequence of the cyd region (54). The PCR product was cleaved with PstI and HindIII and was then ligated with pBluescript II KS(−). The identity of the DNA fragment generated by PCR was verified by DNA sequencing. It was then cloned into pHP13, resulting in plasmid pCYD21. The 3,226-bp BglII-PstI fragment of pCYD9 that carries cydC and part of cydD (Fig. 1) was ligated with pCYD21 cut with BamHI and PstI, resulting in pCYD22. This plasmid was cut with BspEI and NsiI, and the cydCD fragment was isolated and ligated with pCYD20 cut with BspEI and NsiI. The ligate was used to transform B. subtilis 1A1 to chloramphenicol resistance. The resulting plasmid, containing the cydABCD genes, was named pCYD23. As was noted for pCYD20, this plasmid, too, could not be transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue.

Biochemical analyses.

For membrane preparation, B. subtilis strains were grown in NSMP or NSMPG. The bacteria were harvested when they had reached the stationary-growth phase. Membranes were prepared as described previously (21) and resuspended in 20 mM sodium morpholinic propane sulfonic buffer (MOPS), pH 7.4. Protein concentrations were determined by using the bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA; Pierce) with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Difference (reduced minus oxidized) light absorption spectra were recorded as described previously (17). A few grains of sodium dithionite or 10 mM sodium ascorbate was used as the reducing agent, and 1.25 mM potassium ferricyanide was used as the oxidizing agent. When sodium ascorbate was used as the reductant, both cuvettes contained 5 mM potassium cyanide. CO spectra were obtained by bubbling the sample cuvette with carbon monoxide for 2 min.

B. subtilis cytochromes c were radiolabeled by growing cells in NSMP supplemented with 5-[4-14C]aminolevulinic acid (44).

An N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-p-phenyleneamine (TMPD) oxidation assay was performed as described previously (17). β-Galactosidase activity was determined on cell extracts by using 2-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside as a substrate, as described previously (1, 36). Alternatively, β-galactosidase activity was assayed with 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-d-galactoside as a substrate (56). At various intervals during growth, 0.5-ml samples were removed and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Fluorometric readings of β-galactosidase assay samples were performed with a Shimadzu RF-5301PC spectrofluorophotometer.

RESULTS

Identification, organization, and mutagenesis of the cyd gene cluster.

The B. subtilis cydABCD gene cluster (Fig. 1) is located at about 340° on the physical map of the B. subtilis chromosome (30). Analysis of the deduced sequences of B. subtilis cydA and cydB indicated that they are similar to the products of the E. coli cydA and cydB genes, respectively (41 and 36% identity, respectively), which encode the two subunits of the cytochrome bd-type quinol oxidase of E. coli. Studies using site-directed mutagenesis and various spectroscopic methods indicate that in E. coli CydA, His-19, His-186, and Met-393 provide three of the four axial ligands to the iron of the three hemes in the cytochrome bd complex (9, 27, 45, 47). These amino acid residues are preserved in B. subtilis CydA (His-18, His-183, and Met-334). In E. coli CydA, a large periplasmic loop, called the Q-loop, has been proposed to constitute a domain involved in quinol binding (7, 8). Inspection of the B. subtilis CydA amino acid sequence revealed that a large portion of this domain is absent. The cydC and cydD genes have the potential to code for the components of a heterodimeric ABC-type membrane transporter. CydC and CydD show 32 and 29% identity to E. coli CydD and CydC, respectively.

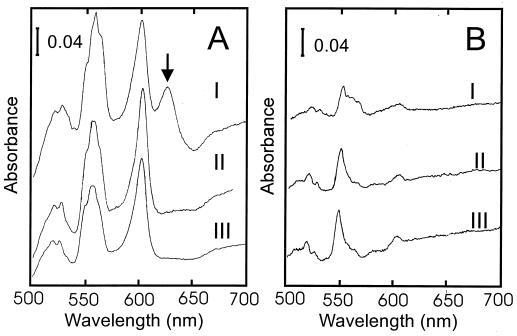

To study the roles of the different B. subtilis cyd genes, plasmid insertion mutagenesis was performed. Disruption of cydA, cydD, or cydABCD (see Materials and Methods) had no apparent effect on the growth of cells in broth or defined media. The total cytochrome contents of cytoplasmic membranes isolated from a wild-type strain and from the CydA and CydD mutants were analyzed by low-temperature (77 K) difference (reduced minus oxidized) spectroscopy (Fig. 2). Spectra of membranes from the wild-type strain demonstrated c-type (peaks in the 550-nm region), b-type (peaks in the 555- to 565-nm region), a-type (peak at 600 nm), and d-type (peak at 622 nm) cytochromes (Fig. 2A). The trough in the difference spectrum at 650 nm most likely originates from a stable oxygenated cytochrome d species (34, 40). The CydA and CydD mutants (Fig. 2A) both lack the peak at 622 nm as well as the trough at 650 nm. This is a diagnostic feature of a strain lacking cytochrome bd. The mutants seem to express less of the b-type cytochromes relative to cytochrome aa3 than does the wild type. By analogy with the E. coli system, it is likely that this is due to the lack of the low-spin cytochrome b component of the cytochrome bd complex in the mutants. The absence of this cytochrome gives a lower absorption in the 558- to 563-nm region.

FIG. 2.

Low-temperature (77 K) light absorption difference spectra of B. subtilis membranes. I, wild-type strain 168A; II, cydD mutant LUW9; III, cydA mutant LUW3. Membranes (10 mg of protein ml−1) were reduced in the sample cuvette with sodium dithionite (A) or sodium ascorbate (B) and oxidized in the reference cuvette with potassium ferricyanide. The arrow indicates the 622-nm maximum of reduced cytochrome d of the cytochrome bd complex. The absorbance scales are indicated by the bars.

With sodium ascorbate as the reducing agent, preferential high-potential c-type cytochromes are seen in the difference spectra. From the reduction with sodium ascorbate, it can be seen that the cytochrome composition in the mutants differs slightly from that in the wild type (Fig. 2B). The spectra indicate a slightly increased expression of a putative cytochrome c in the mutants. The cytochrome composition of membranes from a strain in which cydABCD was deleted (see Fig. 4, spectrum A) was similar to that of the membranes from the CydA mutant strain (Fig. 2A). These data demonstrate that the formation of spectrally detectable cytochrome bd in B. subtilis requires intact cydA and cydD genes. Most probably, cydA codes for a polypeptide of the cytochrome bd complex, whereas the cydD gene is required for assembly of a functional complex.

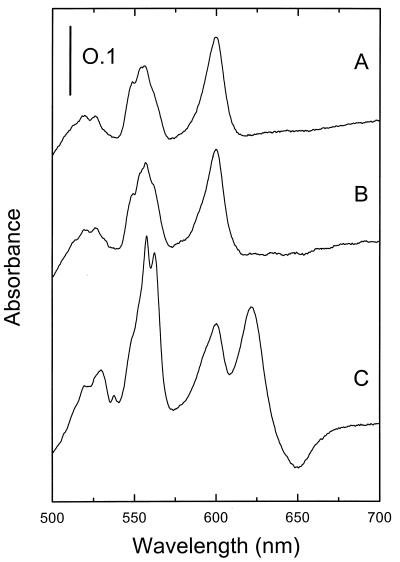

FIG. 4.

Difference spectra of B. subtilis LUW20 membranes isolated from cells harboring plasmid pHP13 (vector alone) (A), pCYD20 (cydAB) (B), or pCYD23 (cydABCD) (C). Strain LUW20 has cydABCD deleted. The spectra were recorded at 77 K on membrane suspensions containing 10 mg of protein ml−1. Membranes were reduced in the sample cuvette with sodium dithionite and oxidized in the reference cuvette with potassium ferricyanide. The vertical bar indicates the absorption scale.

Overproduction of cytochrome bd.

To better resolve the spectral features and provide a convenient source for isolation of cytochrome bd, the complex was overproduced in B. subtilis. Plasmid pCYD20 is a low-copy-number vector containing the cydAB genes and the cyd promoter region. This plasmid was introduced into strain LUH17. This strain lacks the terminal a-type oxidases, cytochrome aa3 and cytochrome caa3. As a consequence, membranes isolated from this strain show no interfering signals in the 600-nm region. Membranes were prepared from cells harboring pCYD20 (cydAB) or pHP13 (vector) and were analyzed for cytochromes by absorbance spectroscopy. At room temperature, the α-absorption maxima of the cytochrome bd oxidase were present at 626, 597, and about 563 nm (Fig. 3). The last absorption maximum was split in two peaks (558 and 563 nm) when the temperature was lowered to 77 K. At this temperature, peaks attributable to cytochrome bd are present at 622, 593, 563, and 558 nm (spectrum not shown). Cytochrome bd was found to be overproduced about fourfold in a strain carrying plasmid pCYD20, as estimated from the intensity of the 626-nm peak (cytochrome d) and to be reduced by NADH via the respiratory chain (data not shown). The CO difference spectrum in the 300- to 400-nm region of membranes of LUH17/pCYD20 revealed absorption troughs at 428 and 440 nm that were about fourfold more pronounced than those of LUH17/pHP13 membranes (data not shown). This indicates that the overproduced enzyme reacts with carbon monoxide like the native enzyme.

FIG. 3.

Light absorption difference spectra of B. subtilis membranes recorded at room temperature. Membrane suspensions (4 mg of protein ml−1) were reduced in the sample cuvette with sodium dithionite and oxidized in the reference cuvette with potassium ferricyanide. (A) LUH17/pHP13; (B) LUH17/pCYD20. Strain LUH17 has cytochromes aa3 and caa3 deleted. The vertical bar indicates the absorption scale.

Overexpression of cydAB from pCYD20 in a strain in which cydABCD had been deleted did not reveal any signals attributable to the cytochrome bd oxidase (Fig. 4, spectrum B). However, when plasmid pCYD23, carrying the complete cydABCD operon, was introduced into strain LUW20 (ΔcydABCD), cytochrome bd was detected, confirming the functionality of the cloned DNA (Fig. 4C). In a wild-type strain transformed with pCYD20 or pCYD23, cytochrome bd was found to be overproduced about fourfold (data not shown). Membranes isolated from strain LUW9 (CydD−) transformed with pCYD20 showed a slight but significant increase in absorbance in the 558-nm region. No cytochrome d signal was seen in these membranes (data not shown).

The cydD gene is not required for the synthesis of c-type cytochromes.

In E. coli the cydCD homologs (cydDC) are required for the assembly of c-type cytochromes (38). To analyze if mutations in cydD or cydABCD influence the synthesis of c-type cytochromes in B. subtilis, heme-specific radioactive labeling was performed. The pattern of c-type cytochromes in membranes isolated from the mutant strains was similar to that of the wild-type strain (data not shown).

B. subtilis strains that lack the structural genes for cytochrome caa3 or are deficient in the synthesis of c-type cytochromes are TMPD oxidase negative (44, 49). Inactivation of cydD or deletion of cydABCD did not affect the ability to oxidize TMPD (data not shown).

We conclude that the cyd genes are not essential for synthesis of B. subtilis cytochromes c.

Expression analysis.

To analyze the expression of the cydABCD genes, we constructed transcriptional and translational fusions with the E. coli lacZ reporter gene (see Materials and Methods). β-Galactosidase activities were measured in intact cells or in extracts of bacteria grown in different media. A transcriptional fusion of cydA to lacZ was constructed. This construct was integrated at the cyd locus to reconstruct the intact chromosomal DNA context upstream of the fusion. The cydA-lacZ fusion was not significantly expressed during growth in NSMP or in DSM (Fig. 5A). However, in NSMPG (broth medium supplemented with glucose), the fusion was activated at the transition between the exponential-growth and the stationary phase (Fig. 5A). Very low activities were detected also when cells were grown in DSM supplemented with glucose. DSM is a nutrient broth-based growth medium that has a composition similar to that of NSMP but lacks the phosphate buffer. In this medium the bacteria grew to a density similar to that in NSMPG (Fig. 5A). To determine whether the levels of cytochrome bd in membranes reflect the patterns of cydA-lacZ expression, we analyzed the cytochrome composition of B. subtilis 1A1 grown in the media described above. In agreement with the cydA-lacZ expression, membranes from cells grown in NSMP or in DSM supplemented with glucose exhibited very small amounts of the cytochrome bd complex (data not shown).

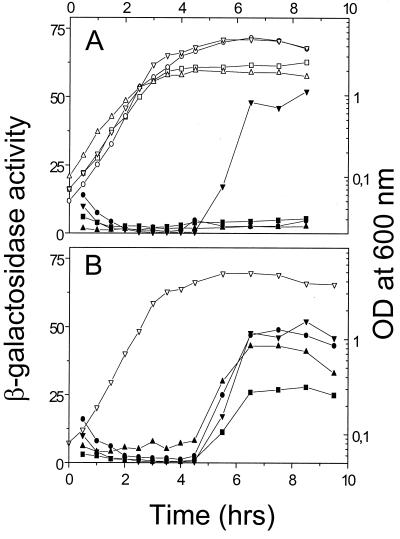

FIG. 5.

β-Galactosidase expression from cyd-lacZ fusions as a function of growth. (A) Activities for the cydA-lacZ fusion are shown for cells grown in DSM (solid squares), NSMP (solid triangles), DSM supplemented with glucose (solid circles), and NSMPG (solid inverted triangles). The optical densities for cells grown in each medium are shown by the corresponding open symbol. (B) β-Galactosidase expression from transcriptional fusions to lacZ integrated by single-crossover recombination at the cydA (solid inverted triangles), cydB (solid circles), cydC (solid triangles), or cydD (solid squares) locus. β-Galactosidase activity is expressed as nanomoles of 2-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside hydrolyzed per minute and milligram of protein. The growth (optical densities) of the cydA-lacZ fusion strain is shown (open inverted triangles). The four strains were grown in NSMPG and showed similar growth properties. Data from a single experiment are presented. Each experiment was repeated at least twice, with similar results.

The timing and amounts of β-galactosidase activity of the transcriptional fusions of cydAB, cydABC, and cydABCD to lacZ showed patterns of expression similar to that seen for the cydA-lacZ fusion (Fig. 5B). This result would be consistent with the promoter upstream of cydA determining the bulk of the expression of the cydABCD genes. The indicated coregulation suggests that the cyd genes are transcribed as an operon. The lack of an apparent transcription terminator in the region covering the cydABCD genes and the finding that the four cyd genes overlap each other further support the operon hypothesis.

A cydA-lacZ translational fusion, containing positions −307 to +6 relative to the initiation codon of CydA, was constructed and inserted by double-crossover recombination at the nonessential amyE locus. Expression in NSMP, NSMPG, DSM alone, and DSM supplemented with glucose followed the pattern described for the cydA-lacZ fusion above (data not shown). This shows that major sites for the regulation of the cydA promoter are located within the 312-bp fragment used for the cydA-lacZ translational fusion.

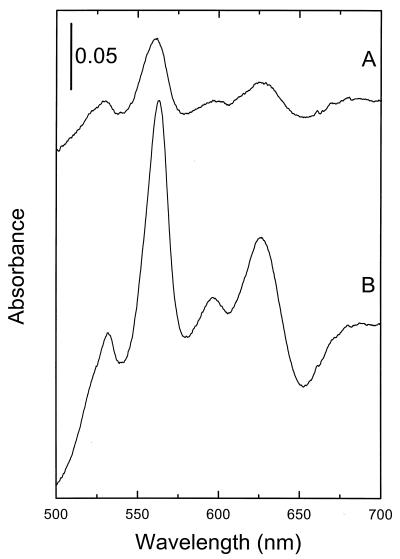

The expression pattern of the cydA-lacZ fusions suggested that the cydA promoter is activated in media that give a high cell density and that this activation may correlate with a decrease in oxygen tension in the culture medium. In support of this idea, we found that when the bacteria were cultivated at high aeration, the expression of the cydA-lacZ fusion was low, whereas the reverse was observed when bacteria were grown under oxygen-limiting conditions (Fig. 6).

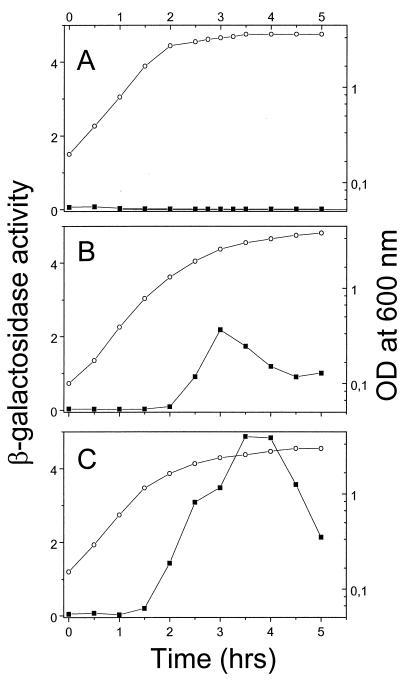

FIG. 6.

Effect of aeration on cydA-lacZ expression. B. subtilis LUW48 was grown in NSMPG in a bioreactor. (A) High aeration, maintained during growth by manually increasing the stirring speed from 250 to 800 rpm. (B) Medium aeration, maintained by constant stirring at 250 rpm. (C) Low aeration, maintained by constant stirring at 250 rpm. The vessel was sparged with sterile air at a flow rate of 1 (A and B) or 0.5 (C) volume of air per volume of liquid per minute. β-Galactosidase activity (solid squares) is expressed as nanomoles of 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-d-galactoside hydrolyzed per minute per OD600 unit. Optical densities are shown as open circles.

Identification of the transcriptional start site for cydA.

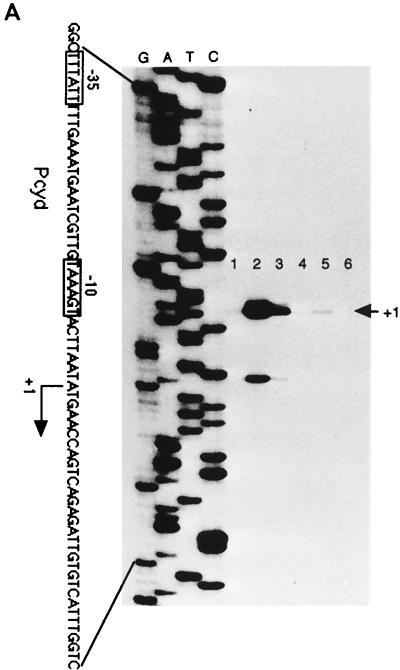

Primer extension analysis was used to identify the cydA promoter. Total RNA was isolated from cells grown in NSMP or NSMPG in the exponential-growth phase, at the time of transition from the exponential-growth to the stationary phase, and approximately 1 h into the stationary phase. Consistent with the results of lacZ fusion studies, cyd mRNA was detected only in late-exponential-phase or stationary-phase cells and preferentially in cells grown in glucose-containing medium (Fig. 7A). The major extension product found indicated that the apparent 5′ end of the cydA mRNA is located 193 bp upstream of the cydA translational start site and is initiated at an adenine nucleotide (Fig. 7A). The size of the major extension product was identical under both growth conditions. The intensity of the signal was highest with RNA isolated from cells grown in NSMPG (Fig. 7A, lanes 2 and 3). Upstream of the transcriptional start point, putative −35 and −10 sigma-A recognition sequences are located (Fig. 7B). The minor extension product seen in Fig. 7A probably originates from an incomplete reverse transcription. However, we cannot rule out the presence of a weaker promoter downstream of that indicated in Fig. 7. Inspection of the promoter region revealed a perfect, 16-bp palindromic sequence (Fig. 7B) 98 bp upstream of the AUG translation initiation sequence for CydA. This sequence may constitute the operator site for a putative regulatory protein.

FIG. 7.

Primer extension mapping of the cydA promoter. (A) Identification of the transcriptional initiation site of the cydA promoter (Pcyd). A known nucleotide sequence ladder was used to estimate the size of the extended product, which is indicated by an arrow. The end-labeled primer was annealed to total RNA isolated from B. subtilis 1A1 cultured in NSMPG (lanes 1 to 3) or in NSMP (lanes 4 to 6). Samples were taken in the exponential-growth phase (lanes 1 and 4), at the time of transition from the exponential-growth to the stationary phase (lanes 2 and 5), and in the stationary phase (lanes 3 and 6). Boxes, −10 and −35 promoter regions of cydA. This promoter is likely to be recognized by RNA polymerase containing the vegetative sigma factor, ςA. (B) Nucleotide sequence of the yxkJ-cydA intergenic region. The apparent transcription start site is indicated as +1. The −10 and −35 promoter regions of the cydA gene are indicated. Also shown is a putative operator sequence, the 16-bp palindrome starting at +80 (underlined). The coordinates are given with respect to the cydA transcription start point. A likely initiation codon (ATG) of cydA is at position +194.

Analysis of RNA transcripts from the cyd region.

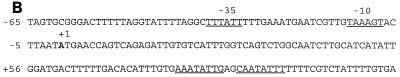

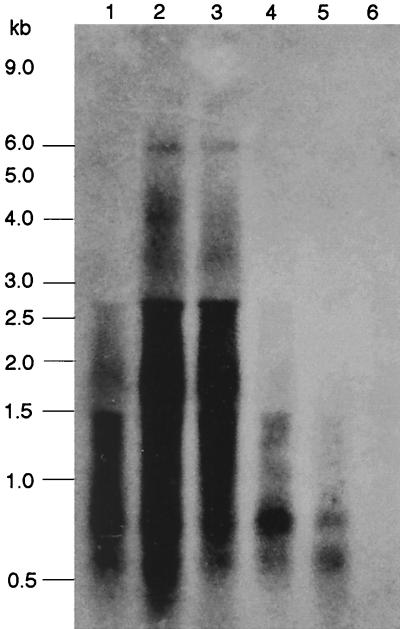

To confirm the organization of the cyd gene cluster, RNA was isolated from wild-type cells grown in NSMP and NSMPG media and was analyzed in Northern blot experiments. When a DNA fragment corresponding to a part of cydA was used as a probe, a transcript of approximately 6,000 nucleotides was detected with RNA extracted from cells grown in NSMPG (Fig. 8, lanes 1 to 3). This transcript has the length expected for a polycistronic cydABCD mRNA. We could not detect any full-length transcript in cells grown in NSMP (Fig. 8, lanes 4 to 6), which is in agreement with the much-lower expression of, e.g., the cydA-lacZ fusion, in NSMP than in NSMPG (Fig. 5A). Analysis of the signal intensities in this experiment are also in good agreement with that found in the primer extension analysis (Fig. 7A). Preliminary Northern blot experiments with RNA isolated from cells grown in NSMPG, using DNA fragments corresponding to cydB, cydC, and cydD as probes, also showed a transcript of approximately 6,000 nucleotides. The cydABCD transcript appears to be highly unstable (Fig. 8). To rule out any general problem with RNA degradation, the blots were reprobed with DNA fragments corresponding to parts of galE and yxjF. These probes detected intact transcripts of the expected sizes and showed no hybridization smears (data not shown).

FIG. 8.

Northern blot analysis of B. subtilis 1A1 total RNA using a cydA probe labeled with 32P. RNA was isolated from cells grown in NSMPG (lanes 1 to 3) or in NSMP (lanes 4 to 6). Samples were taken in the exponential-growth phase (lanes 1 and 4), at the time of transition from the exponential-growth to the stationary phase (lanes 2 and 5), and in the stationary phase (lanes 3 and 6). The positions of RNA size standards are indicated on the left. In addition to cyd-specific transcripts, the probes hybridized nonspecifically to 16S (1,553 bases) and 23S (2,928 bases) rRNA.

DISCUSSION

The respiratory chain of B. subtilis is branched, with at least three terminal oxidases, cytochrome aa3, cytochrome caa3, and cytochrome bd, being synthesized under different growth conditions (52). During vegetative growth, cytochrome aa3 is likely to be the major terminal oxidase contributing to proton motive force generation. In this paper we have characterized four genes, cydA, cydB, cydC, and cydD, that are required for the expression of cytochrome bd in B. subtilis. Based on sequence comparisons, cydA and cydB are likely to code for the two subunits of a cytochrome bd-type quinol oxidase. The cydC and cydD gene products are most likely not part of the functional oxidase but are required for its assembly. The physiological roles of cytochrome bd-type quinol oxidases in bacteria are in general far from being fully understood. In A. vinelandii and Klebsiella pneumoniae, one important role of cytochrome bd is to scavenge oxygen that otherwise could inactivate the oxygen-sensitive nitrogenases of these bacteria (26, 37). In E. coli, cytochrome bd may perform two physiological roles: contributing to energy conservation under microaerobiosis and protecting the cell from oxidative stress (22). The physiological role of cytochrome bd in B. subtilis has not been established. Disruption of the B. subtilis cyd genes had no apparent effect on the growth of cells in broth or defined media. The presence of cytochrome bd-like quinol oxidases appears to be widespread among prokaryotes, indicating that this type of oxidase plays important functional roles. Sequences predicted to encode bd-type oxidases have been reported for Archaea and Bacteria but do not appear to be present among Eukarya (2, 4, 6, 25). Computer analysis of the deduced B. subtilis CydA sequence showed that it is most closely related to the corresponding protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (2).

Analysis of the genome sequence of B. subtilis revealed one cydA paralogue, ythA, which is the first gene of a putative ythABC operon (30). Sequence comparisons show that YthA is distantly related to the known CydA sequences. YthB encodes a protein similar to CydB in size but does not reveal any convincing sequence similarity to the known CydB sequences. Nevertheless, the YthB and CydB sequences show striking similarities in their hydropathy profiles, indicating that YthAB may be part of a cytochrome bd-like enzyme (data not shown). The third gene, ythC, encodes a 55-residue amphiphilic and basic protein which does not show any striking similarity to sequences in databases. Analysis of B. subtilis membranes showed that inactivation of cydA or deletion of cydABCD resulted in the loss of spectral features associated with cytochrome bd, suggesting that YthAB has distinct spectral characteristics or that the yth genes are poorly expressed under the conditions used.

As reported herein, the B. subtilis cydA, cydB, cydC, and cydD genes are transcribed as a polycistronic message. A corresponding gene organization may also be present in M. tuberculosis (2). In E. coli and in other bacteria where cydC and cydD have been clearly identified, these genes are adjacent to each other but separate from cydAB (3). The sequences of CydC and CydD suggest that they comprise an ATP-dependent membrane transporter of the ABC superfamily (33, 39). Mutations in the E. coli cydC or cydD gene affect the assembly of cytochrome bd (12, 39). The apoproteins are made and inserted into the membrane, but the mutant complexes are missing heme d and presumably hemes b595 and b558 (38). However, cytochrome bd can be detected in a cydC mutant if the cydAB genes are overexpressed from a multicopy plasmid (14). In addition, CydC and CydD are required for synthesis of all c-type cytochromes and of cytochrome b562 (15, 38). In B. subtilis, mutations in cydCD or cydD result in the loss of all spectral features attributable to the cytochrome bd complex but do not affect the synthesis of c-type cytochromes or presumably of any other cytochrome complex. This suggests that B. subtilis cydCD genes are required only for the assembly of a functional cytochrome bd, whereas in E. coli these genes have additional roles. In a B. subtilis strain with cydABCD deleted, synthesis of cytochrome bd can be restored when the four genes are supplied on a plasmid. Overexpression of cydAB alone does not allow cytochrome bd to be produced even in a CydD mutant strain. The substrate of the CydCD transporter is not known. It has been suggested that the transporter is involved in the export of heme to the periplasm of E. coli (39). Goldman et al. (15) proposed, based on experiments with periplasmic heme reporters, that the CydCD transporter is not a heme exporter but is required for the control of the reducing environment within the periplasmic space. In B. subtilis, all cytochromes c have their heme domain exposed to the outer face of the cytoplasmic membrane (51). The presence of holocytochromes c in membranes from B. subtilis CydABCD or CydD mutant strains suggests that mutations in cydCD do not affect the transport of heme across the membrane or its subsequent attachment to the apocytochromes c.

The regulation of the amount of cytochrome bd in B. subtilis under various growth conditions appears to be primarily at the level of transcription of the cydABCD operon. When cells are grown with high aeration, the expression of cytochrome bd is repressed. When the oxygen tension of the growth medium is decreased, expression of the cyd operon is induced and reaches its maximum during the transition from the exponential- to the stationary-growth phase. The cydABCD operon appears to be highly regulated in response to oxygen. However, in a nonbuffered, low-phosphate medium (DSM supplemented with glucose), expression of the cydABCD operon was significantly reduced from that in a buffered, high-phosphate medium (NSMPG). Thus, for maximal expression of the cyd genes, specific medium compositions as well as conditions of low oxygen tension are required.

It is likely that B. subtilis makes regulatory proteins that function either to activate cyd expression as oxygen becomes limiting or, alternatively, to repress cyd expression under conditions of high oxygen tension. The lacZ reporter constructs described in this paper should be helpful in identifying such regulatory proteins.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Lars Rutberg for valuable comments on the manuscript. We also thank Lars Hederstedt for helpful advice and for providing strains LUH15 and LUH17.

This work was supported by grants from the Crafoordska Stiftelsen and the Emil och Wera Cornells Stiftelse and by INTAS-RBFR grant 95-1259. Part of this work was also supported by a grant, JSPS-RFTF96L00105, from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atkinson M R, Wray L V, Jr, Fisher S H. Regulation of histidine and proline degradation enzymes by amino acid availability in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4758–4765. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.4758-4765.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cole S T, Brosch R, Parhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon S V, Eiglmeier K, Gas G, Barry III C E, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingwort T, Conner R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, McLean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Osborne J, Quail M A, Rajandream M-A, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Sulston J E, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Barrell B G. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook G M, Membrillo-Hernandez J, Poole R K. Transcriptional regulation of the cydDC operon, encoding a heterodimeric ABC transporter required for assembly of cytochromes c and bd in Escherichia coli K-12: regulation by oxygen and alternative electron acceptors. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6525–6530. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6525-6530.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham L, Pitt M, Williams H D. The cioAB genes from Pseudomonas aeruginosa code for a novel cyanide-insensitive terminal oxidase related to the cytochrome bd quinol oxidases. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:579–591. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3561728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahl M K, Meinhof C-G. A series of integrative plasmids for Bacillus subtilis containing unique cloning sites in all three open reading frames for translational lacZ fusions. Gene. 1994;145:151–152. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deckert G, Warren P V, Gaasterland T, Young W G, Lenox A L, Graham D E, Overbeek R, Snead M A, Keller M, Aujay M, Huber R, Feldman R A, Short J M, Olsen G J, Swanson R V. The complete genome of the hyperthermophilic bacterium Aquifex aeolicus. Nature. 1998;392:353–358. doi: 10.1038/32831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dueweke T J, Gennis R B. Epitopes of monoclonal antibodies which inhibit ubiquinol oxidase activity of Escherichia coli cytochrome d complex localize functional domain. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:4273–4277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dueweke T J, Gennis R B. Proteolysis of the cytochrome d complex with trypsin and chymotrypsin localizes a quinol oxidase domain. Biochemistry. 1991;30:3401–3406. doi: 10.1021/bi00228a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang H, Lin R J, Gennis R B. Location of heme axial ligands in the cytochrome d terminal oxidase complex of Escherichia coli determined by site-directed mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:8026–8032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fortnagel P, Freese E. Analysis of sporulation mutants. II. Mutants blocked in the citric acid cycle. J Bacteriol. 1968;95:1431–1438. doi: 10.1128/jb.95.4.1431-1438.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia-Horsman J A, Barquera B, Rumbley J, Ma J, Gennis R B. The superfamily of heme-copper respiratory oxidases. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5587–5600. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.18.5587-5600.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Georgiou C D, Fang H, Gennis R B. Identification of the cydC locus required for expression of the functional form of the cytochrome d terminal oxidase complex in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2107–2112. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.5.2107-2112.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilmour R, Krulwich T A. Construction and characterization of a mutant of alkaliphilic Bacillus firmus OF4 with a disrupted cta operon and purification of a novel cytochrome bd. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:863–870. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.863-870.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldman B S, Gabbert K K, Kranz R G. The temperature-sensitive growth and survival phenotypes of Escherichia coli cydDC and cydAB strains are due to deficiencies in cytochrome bd and are corrected by exogenous catalase and reducing agents. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6348–6351. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.21.6348-6351.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldman B S, Gabbert K K, Kranz R G. Use of heme reporters for studies of cytochrome biosynthesis and heme transport. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6338–6347. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.21.6338-6347.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green G N, Fang H, Lin R J, Newton G, Mather M, Georgiou C D, Gennis R B. The nucleotide sequence of the cyd locus encoding the two subunits of the cytochrome d terminal oxidase complex of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:13138–13143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green G N, Gennis R B. Isolation and characterization of an Escherichia coli mutant lacking cytochrome d terminal oxidase. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:1269–1275. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.3.1269-1275.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guerout-Fleury A M, Shazand K, Frandsen N, Stragier P. Antibiotic-resistance cassettes for Bacillus subtilis. Gene. 1995;167:335–336. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00652-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haima P, Bron S, Venema G. The effect of restriction on shotgun cloning and plasmid stability in Bacillus subtilis Marburg. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;209:335–342. doi: 10.1007/BF00329663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanahan D, Jessee J, Bloom F R. Plasmid transformation of Escherichia coli and other bacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:63–113. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04006-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hederstedt L. Molecular properties, genetics, and biosynthesis of Bacillus subtilis succinate dehydrogenase complex. Methods Enzymol. 1986;126:399–414. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(86)26040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill S, Viollet S, Smith A T, Anthony C. Roles for enteric d-type cytochrome oxidase in N2 fixation and microaerobiosis. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2071–2078. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.4.2071-2078.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoch J A. Genetic analysis in Bacillus subtilis. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:305–320. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04015-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Igo M M, Losick R. Regulation of a promoter that is utilized by minor forms of RNA polymerase holoenzyme in Bacillus subtilis. J Mol Biol. 1986;191:615–624. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90449-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jünemann S. Cytochrome bd terminal oxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1321:107–127. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(97)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Juty N S, Moshiri F, Merrick M, Anthony C, Hill S. The Klebsiella pneumoniae cytochrome bd′ terminal oxidase complex and its role in microaerobic nitrogen fixation. Microbiology. 1997;143:2673–2683. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-8-2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaysser T M, Ghaim J B, Georgiou C, Gennis R B. Methionine-393 is an axial ligand of the heme b558 component of the cytochrome bd ubiquinol oxidase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1995;34:13491–13501. doi: 10.1021/bi00041a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kita K, Konishi K, Anraku Y. Terminal oxidases of Escherichia coli aerobic respiratory chain. II. Purification and properties of cytochrome b558-d complex from cells grown with limited oxygen and evidence of branched electron-carrying systems. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:3375–3381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kranz R G, Gennis R B. Immunological investigation of the distribution of cytochromes related to the two terminal oxidases of Escherichia coli in other gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:709–713. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.2.709-713.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kunst F, et al. The complete genome sequence of the Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 1997;390:249–256. doi: 10.1038/36786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kyte J, Doolittle R F. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lauraeus M, Haltia T, Saraste M, Wikström M. Bacillus subtilis expresses two kinds of haem-A-containing terminal oxidases. Eur J Biochem. 1991;197:699–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb15961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Linton K, Higgins C F. The Escherichia coli ATP-binding cassette (ABC) proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:5–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller M J, Gennis R B. The purification and characterization of the cytochrome d terminal oxidase complex of the Escherichia coli aerobic respiratory chain. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:9159–9165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niaudet B, Goze A, Ehrlich S D. Insertional mutagenesis in Bacillus subtilis: mechanism and use in gene cloning. Gene. 1982;19:277–284. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nihashi J, Fujita Y. Catabolite repression of inositol dehydrogenase and gluconate kinase syntheses in Bacillus subtilis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;798:88–95. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(84)90014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poole R K, Hill S. Respiratory protection of nitrogenase activity in Azotobacter vinelandii—roles of the terminal oxidases. Biosci Rep. 1997;17:303–317. doi: 10.1023/a:1027336712748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poole R K, Gibson F, Wu G. The cydD gene product, component of a heterodimeric ABC transporter, is required for assembly of periplasmic cytochrome c and of cytochrome bd in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;117:217–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poole R K, Hatch L, Cleeter M W J, Gibson F, Cox G B, Wu G. Cytochrome bd biosynthesis in Escherichia coli: the sequences of the cydC and cydD genes suggest that they encode components of an ABC membrane transporter. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:421–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poole R K, Kumar C, Salmon I, Chance B. The 650 chromophore in Escherichia coli is an ‘oxy-’ or oxygenated compound, not the oxidized form of cytochrome oxidase d: an hypothesis. J Gen Microbiol. 1983;129:1335–1344. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-5-1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sakamoto J, Matsumoto A, Oobuchi K, Sone N. Cytochrome bd-type quinol oxidase in a mutant of Bacillus stearothermophilus deficient in caa3-type cytochrome c oxidase. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;143:151–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schaeffer P, Millet J, Aubert J P. Catabolic repression of bacterial sporulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1965;54:704–711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.54.3.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schiött T, von Wachenfeldt C, Hederstedt L. Identification and characterization of the ccdA gene, required for cytochrome c synthesis in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1962–1673. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.6.1962-1973.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spinner F, Cheesman M R, Thomson A J, Kaysser T, Gennis R B, Peng Q, Peterson J. The haem b558 component of the cytochrome bd quinol oxidase complex from Escherichia coli has histidine-methionine axial ligation. Biochem J. 1995;308:641–644. doi: 10.1042/bj3080641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spizizen J. Transformation of biochemically deficient strains of Bacillus subtilis by deoxyribonucleate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1958;44:1072–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.44.10.1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun J, Kahlow M A, Kaysser T M, Osborne J P, Hill J J, Rohlfs R J, Hille R, Gennis R B, Loehr T M. Resonance Raman spectroscopic identification of a histidine ligand of b595 and the nature of the ligation of chlorin d in the fully reduced Escherichia coli cytochrome bd oxidase. Biochemistry. 1996;35:2403–2412. doi: 10.1021/bi9518252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vagner, V., E. Dervyn, and S. D. Ehrlich. A vector for systematic gene inactivation in Bacillus subtilis. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.van der Oost J, von Wachenfeldt C, Hederstedt L, Saraste M. Bacillus subtilis cytochrome oxidase mutants: biochemical analysis and genetic evidence for two aa3-type oxidases. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2063–2072. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Villani G, Tattoli M, Capitanio N, Glaser P, Papa S, Danchin A. Functional analysis of subunits III and IV of Bacillus subtilis aa3-600 quinol oxidase by in vitro mutagenesis and gene replacement. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1232:67–74. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(95)00112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.von Wachenfeldt, C. Unpublished data.

- 52.von Wachenfeldt C, Hederstedt L. Molecular biology of Bacillus subtilis cytochromes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;100:91–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb14025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yoshida K, Shindo K, Sano H, Seki S, Fujimura M, Yanai N, Miwa Y, Fujita Y. Sequencing of a 65 kb region of the Bacillus subtilis genome containing the lic and cel loci, and creation of a 177 kb contig covering the gnt-sacXY region. Microbiology. 1996;142:3113–3123. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-11-3113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoshida K I, Aoyama D, Ishio I, Shibayama T, Fujita Y. Organization and transcription of the myo-inositol operon, iol, of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4591–4598. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.14.4591-4598.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Youngman P. Use of transposons and integrational vectors for mutagenesis and construction of gene fusions in Bacillus subtilis. In: Harwood C R, Cutting S M, editors. Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1990. pp. 221–266. [Google Scholar]