Abstract

RNA editing in various organisms commonly restores RNA sequences to their ancestral state, but its adaptive advantages are debated. In fungi, restorative editing corrects premature stop codons in pseudogenes specifically during sexual reproduction. We characterized 71 pseudogenes and their restorative editing in Fusarium graminearum, demonstrating that restorative editing of 16 pseudogenes is crucial for germ tissue development in fruiting bodies. Our results also revealed that the emergence of premature stop codons is facilitated by restorative editing and that premature stop codons corrected by restorative editing are selectively favored over ancestral amino acid codons. Furthermore, we found that ancestral versions of pseudogenes have antagonistic effects on reproduction and survival. Restorative editing eliminates the survival costs of reproduction caused by antagonistic pleiotropy and provides a selective advantage in fungi. Our findings highlight the importance of restorative editing in the evolution of fungal complex multicellularity and provide empirical evidence that restorative editing serves as an adaptive mechanism enabling the resolution of genetic trade-offs.

Restorative RNA editing is adaptive in fungi by eliminating survival costs of reproduction caused by antagonistic pleiotropy.

INTRODUCTION

RNA editing challenges the central dogma of molecular biology by altering the genetic information at the transcript level. A variety of RNA editing types, including nucleotide insertions, deletions, or substitutions, have evolved independently multiple times in diverse eukaryotic lineages (1–3). Most of these are documented in organelle-encoded RNAs, such as the cytidine-to-uridine (C-to-U) editing in plant mitochondria and chloroplasts, and the U insertion/deletion editing in kinetoplastid mitochondria. Adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) editing is remarkable among all RNA editing types found to date, as it changes plenty of nucleus-encoded mRNAs across the animal kingdom (3). Since the initial discovery of RNA editing in 1986 (4), why organisms have evolved such seemingly convoluted mechanisms to express their genes has been the subject of great interest and debate. Organellar RNA editing commonly acts to restore the ancestral RNA sequence and, consequently, the ancestral protein function (1, 5). Restorative editing is commonly viewed as a compensatory repair mechanism that corrects pre-existing genomic mutations (6, 7). However, it is worth noting that many of the genomic mutations corrected by RNA editing have serious physiological consequences. It seems unlikely that these mutations could persist without being eliminated by purifying selection long before the emergence of RNA editing to correct them. Therefore, while the compensatory type of restorative editing is considered adaptive because of the advantages of having editing over no editing, it is expected to occur less frequently. On the other hand, the constructive neutral evolution (CNE) theory (8) and the harm-permitting model (9) propose that the repair capacity of pre-existing RNA editing activities can relax functional constraints at the DNA level, allowing otherwise harmful mutations to become fixed in genomes. As a critical number of deleterious mutations accumulate, RNA editing persists and becomes an essential component of the genetic information expression pathway. Harm-permitting restorative editing is therefore crucial for establishing and maintaining RNA editing systems. This type of A-to-I editing is common in animals (9, 10), with a well-known example being the essential Q/R editing site in mammalian GluA2 (11). However, it is important to note that because harmful mutations are fixed through RNA editing, the mutation and editing processes cannot be separated independently during evolution. Therefore, when evaluating the effects of harm-permitting A-to-I editing, it is more appropriate to compare it with the original genomic G rather than the postmutational A without editing (9). In this sense, harm-permitting restorative editing encompasses both the mutation and editing processes, distinguishing it from compensatory restorative editing. Although harm-permitting restorative editing is functionally important, it is considered a nonadaptive and unnecessarily complex process since correcting one’s own “mistakes” does not seem to increase fitness (9, 12). Currently, there is no empirical evidence to support the notion that harm-permitting restorative editing provides an adaptive advantage compared to the original unmutated versions.

Transcriptome-wide A-to-I RNA editing has recently been found in fungi (13). It occurs specifically during sexual reproduction and fruiting body formation in filamentous ascomycetes (Pezizomycotina) (2). A-to-I RNA editing is a common feature in Sordariomycetes (2), one of the largest classes of Ascomycota characterized by perithecia (fruiting bodies). It has also been found in Pyronema confluens (14), a species belonging to Pezizomycetes. Our recent work has identified the A-to-I RNA editing machinery in Sordariomycetes and demonstrated that it originated in the last common ancestor of Sordariomycetes (15). The A-to-I RNA editing in Pezizomycetes has an independent origin. Fruiting bodies are among the most complex structures produced by filamentous ascomycetes, differentiating a range of cell types that are not found in vegetative hyphae, particularly the specialized sexual dikaryotic (germ) tissues including ascogenous hyphae, croziers, and asci (16). Specialization of germ (reproductive) and somatic (vegetative) tissues is known as a hallmark of the evolution of multicellularity (17). More than 40,000 A-to-I RNA editing sites have been identified in perithecia of Fusarium graminearum and Neurospora crassa (18, 19). Notably, restorative A-to-I editing, named premature stop codon correction (PSC) editing (2, 18), was found to correct UAG premature stop codons of pseudogenes during sexual development in F. graminearum and N. crassa (18, 19). The above findings raise several intriguing questions: Do these pseudogenes and their PSC editing have important functions in fungal complex multicellularity? Why did these genes evolve into pseudogenes? Is there an adaptive advantage of using PSC editing to repair pseudogenes compared to encoding normal genes directly in the genome, and if so, what is the adaptive advantage?

While natural selection is a powerful force in evolution, it is not all-powerful. Adaptations to one condition may lead to decreased fitness in other conditions, resulting in evolutionary trade-offs between different traits (20). All organisms face various forms of stress in their life histories and must balance different traits to maximize overall fitness during stressful times. The trade-offs between different life-history traits, particularly those between the two fitness components of survival and reproduction, known as the “survival cost of reproduction,” play a critical role in the evolution of germ-soma specialization and enable the transition toward higher levels of biological complexity (21–24). However, survival-reproduction trade-offs are rarely reported in fungi. To our knowledge, the only reported cases are in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (25) and the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe (26). Antagonistic pleiotropy is thought to be the predominant factor in causing life-history trade-offs (27). Although life-history trade-offs have been well documented in animals, relatively few genes with antagonistic effects on life-history traits have been identified (28, 29). Genomic mutations generate alleles in a binary manner, while RNA editing levels can be regulated specifically in tissues or developmental stages. The ability to induce genomic mutations and flexibly regulate gene expression has led us to hypothesize that PSC editing may have a selective advantage in resolving trade-offs arising from antagonistic pleiotropy.

F. graminearum is a predominant causal agent of Fusarium head blight (FHB), one of the most devastating diseases on cereal crops worldwide. Sexual reproduction plays a critical role in its life cycle because ascospores discharged from the perithecia produced on crop residues are the primary inoculum of FHB (30). F. graminearum serves as an excellent system for genetically studying sexual development as it is homothallic and produces abundant perithecia under laboratory conditions. In this study, we systematically characterized 71 pseudogenes and their PSC editing in F. graminearum. Our findings revealed that most of these genes are genetic innovations that underpin the evolution of fruiting bodies in filamentous ascomycetes. Among these pseudogenes, 18 play crucial roles in germ tissue development, and PSC editing is necessary for the functioning of 16 of them. We showed that the emergence of premature stop codons in pseudogenes occurred during the evolution in Sordariomycetes and was facilitated by restorative editing and that the premature stop codons were selectively favored over ancestral amino acid codons. Moreover, we demonstrated that the ancestral unmutated versions of at least two pseudogenes act as trade-off genes with antagonistic effects on reproduction and survival. Thus, the emergence of premature stop codons (pseudogenization) and sexual stage–specific PSC editing in these genes eliminates the survival costs of reproduction caused by antagonistic pleiotropy and provides a selective advantage in fungi. Overall, our findings challenge the neutral evolutionary view that harm-permitting restorative editing is a nonadaptive process. Our study provides insights for understanding the origin and maintenance of different RNA editing systems.

RESULTS

Identification and characterization of PSC pseudogenes in F. graminearum

In the previous study (13), we identified 70 pseudogenes with PSC-editing sites in their coding regions (described as PSC pseudogenes in this study) in F. graminearum. On the basis of the updated genome sequence and annotation of F. graminearum strain PH-1 (31), seven of them were not PSC pseudogenes when they were correctly annotated. In addition, we identified eight PSC pseudogenes that were not found earlier because of annotation errors. Among the updated list of 71 PSC pseudogenes (Fig. 1A and table S1), 6 of them, PSC03, PSC25, PSC34, PSC51, PSC62, and PSC68, have two PSC-editing sites. The revised sequences of all PSC pseudogenes are available at FgBase (http://fgbase.wheatscab.com/).

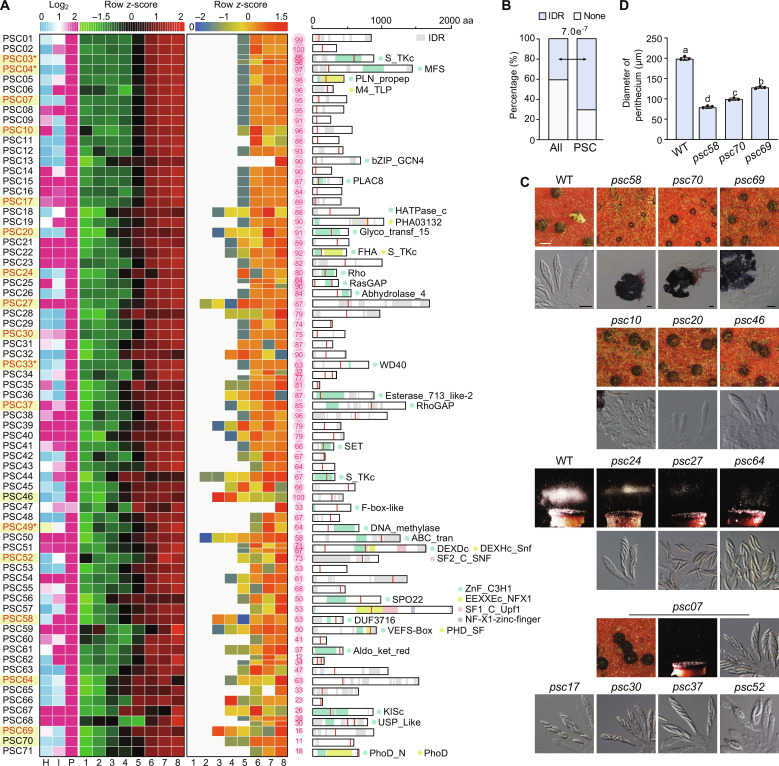

Fig. 1. Expression patterns, editing dynamics, protein domains, and functional importance of PSC pseudogenes in Fusarium graminearum.

(A) Expression patterns, editing dynamics, and protein domains of 71 PSC pseudogenes. Heatmaps show the log2-normalized transcripts per million (TPM) values from RNA-seq data of vegetative hyphae (H), host infection (I), and perithecia (P), or row z-score scaled TPM values (left) and editing levels (right) from RNA-seq data of sexual development from 1 to 8 days postfertilization (dpf). Bubble maps show the maximum editing level (%). The full-length proteins with conserved domains or intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) are shown on the far right. Red bars mark the PSC-editing sites on proteins. Gene names for germ-needed PSC pseudogenes are highlighted in yellow. The red font indicates the PSC pseudogenes that require PSC editing for functions. Asterisk (*) marks the genes characterized previously. aa, amino acids. (B) Stacked bar charts showing percentages of PSC pseudogenes (PSC) or all predicted genes in the genome with or without IDR. The P value from the χ2 test is indicated. (C) The 7-dpf mating cultures of PH-1 [wild type (WT)] and the marked deletion mutants were examined for perithecium formation (scale bar, 0.2 mm), ascus/ascospore morphology (scale bar, 20 μm), and ascospore discharge. (D) The diameter of perithecia produced by the marked strains at 7 dpf. Mean and SD were calculated with data from three independent replicates (n = 3), each with at least 20 perithecia examined. Different letters indicate significant differences based on one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Turkey’s multiple range test (P < 0.05).

On the basis of published RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data (31), the expression of 55 PSC pseudogenes was up-regulated in perithecia compared to vegetative and infectious hyphae (Fig. 1A). Transcripts of the remaining 16 PSC pseudogenes were abundant in all three stages. We then examined their expression and editing levels from RNA-seq data of 1 to 8 days postfertilization (dpf) (32). Almost all these PSC pseudogenes had up-regulated expression and detectable PSC-editing events after 5 dpf (Fig. 1A). With PSC editing, 28 PSC pseudogenes encode proteins with conserved domains, but the remaining 43 encode hypothetical proteins (Fig. 1A and table S1). Notably, 50 of the 71 (71%) PSC pseudogenes encode proteins with intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) (33). Compared to all the predicted genes in the genome, these PSC pseudogenes were significantly enriched for IDR (Fig. 1B).

Eighteen PSC pseudogenes play crucial roles in different stages of germ tissue development

Deletion mutants of eight PSC pseudogenes, PSC01, PSC02, PSC03/PUK1, PSC04/AMD1, PSC24, PSC33/FgAMA1, PSC49/FgRID1, and PSC51, have been generated in previous studies (13, 34–36). For the remaining 63 PSC pseudogenes, we obtained at least two independent deletion mutants for each of them with the gene replacement approach (fig. S1 and table S2). The deletion mutants were examined for defects in vegetative growth, colonial morphology, conidiation, sexual reproduction, and sexual/asexual spore germination (table S3). Whereas all these deletion mutants were normal in asexual stages, the deletion of 14 PSC pseudogenes resulted in defects in different stages of sexual development (Fig. 1C and fig. S2), in addition to the four (PUK1, AMD1, FgAMA1, and FgRID1) known to be important in sexual reproduction previously.

Mutants deleted of three PSC pseudogenes, PSC58, PSC69, and PSC70, formed smaller perithecia that were sterile and lacked germ tissues (Fig. 1, C and D). These three mutants produced morphologically normal asci and ascospores as a female in crossing with the mat1-1-1 deletion mutant (fig. S2), indicating that they are functional in the inner ascogenous hyphae (from both the male and female) rather than the outer envelope (from the female). Accordingly, PSC58, PSC69, and PSC70 are essential for ascogenous hypha formation.

Deletion mutants of PSC10, PSC20, and PSC46 developed normal-sized perithecia without cirrhi formation and spore firing at 7 dpf (Fig. 1C and fig. S2). No typical asci were produced in the psc10 mutant, and only a few asci were observed in the psc20 and psc46 mutants. The psc10 mutant regularly formed short ascogenous hyphae and croziers at 3 dpf. Unexpectedly, its croziers did not produce asci but continued to form ascogenous hyphae, resulting in masses of excessively elongated ascogenous hyphae (Fig. 2A). In the psc20 mutant, ascus and ascospore maturation was normal but ascus formation was delayed about 3 days (Fig. 2B). In the psc46 mutant, ascogenous hyphae and asci were regularly formed but most of them were prematurely degraded in developing perithecia (Fig. 2B). At 10 dpf, only a few germinated ascospores were observed in perithecia. Therefore, PSC10 is critical for the differentiation of asci; PSC20 is important for ascus formation by promoting the development of ascogenous hyphae; PSC46 is important for ascus formation and maturation possibly by inhibiting programmed cell death (PCD) of ascogenous hyphae and asci.

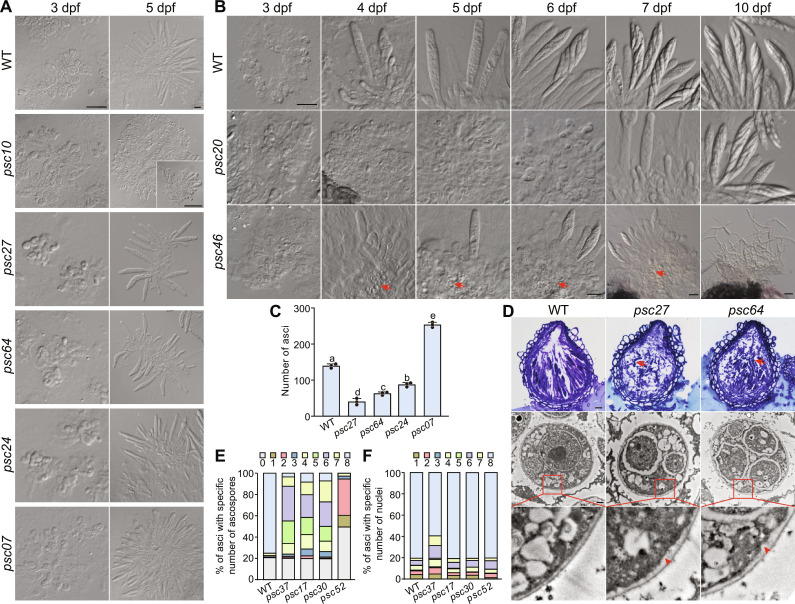

Fig. 2. Defects in different stages of germ tissue development in deletion mutants of PSC pseudogenes.

(A) Ascogenous hyphae and fascicles of asci observed by differential interference contrast microscopy after squeezing the 3- or 5-dpf perithecia of the marked strains. Scale bar, 20 μm. (B) Time-course observations of germ tissue development in perithecia of the marked strains. Scale bar, 20 μm. Red arrows indicate degraded cells. (C) The number of asci per perithecium produced by the marked strains at 5 dpf. Mean and SD were calculated with data from three independent replicates (n = 3), each with at least 17 perithecia examined. Different letters indicate significant differences based on one-way ANOVA followed by Turkey’s multiple range test (P < 0.05). (D) Microscopic observations of the marked strains after semithin (top; scale bar, 20 μm) and ultrathin sectioning (bottom; scale bar, 500 nm). Red arrows indicate the germinated ascospores; red arrowheads indicate the thickened inner face of the ascus walls. (E and F) The percentage of asci containing a specific number of ascospores in the marked strains at 7 dpf (E) or nuclei in the marked strains at 5 dpf (F). The data are presented as the mean calculated from three independent replicates (n = 3), each with at least 80 asci examined.

Deletion mutants of PSC24, PSC27, and PSC64 exhibited decreased spore firing (Fig. 1C). These three mutants showed a reduction in the average number of asci per perithecium by 37 to 71%. (Fig. 2C). Relatively few ascogenous hyphae were formed at 3 dpf (Fig. 2B), indicating that defects in ascogenous hypha development may partially account for the reduced number of asci. Moreover, whereas fascicles of asci were present in mature perithecia of the wild type, scattered ascospores but fewer intact asci were observed in those of the psc27 and psc64 mutants (Figs. 1C and 2D), suggesting the breakdown of ascus walls. The ascospore walls and the inner face of ascus walls increased in thickness irregularly in the psc27 and psc64 mutants (Fig. 2D). Ascospore germination was visible inside the perithecia of both mutants. These results indicate that the structural changes in ascus and ascospore walls may account for improper ascus wall disintegration and ascospore germination. The psc07 mutant showed a 1.8-fold increase in the average number of asci per perithecium compared to the wild type. However, no spore firing was observed in this mutant (Figs. 1C and 2C). There were no obvious changes in the amount of ascogenous hyphae at 3 dpf, but the fascicles of asci at 5 dpf were larger than those of the wild type (Fig. 2A), implying that the rate of ascus-crozier formation is increased in the psc07 mutant. Therefore, PSC07, PSC24, PSC27, and PSC64 are important for ascus formation and the last two are also important for ascus and ascospore maturation.

Deletion mutants of PSC17, PSC30, PSC37, and PSC52 regularly produced asci, but most of their asci had fewer than eight ascospores (Fig. 2E). Particularly, more than 45% of asci in the psc52 mutant contained only one to two ascospores per ascus. In addition, the ascospores formed by the psc30 and psc17 mutants had morphological abnormalities (Fig. 1C). Whereas normal ascospores were four-celled, most ascospores in the psc17 mutant were two-celled. Like in the puk1 mutant (13), some ascospores were deeply constricted at the septum in the psc30 mutant. The fraction of asci with the abnormal number (6 or 7) of nuclei at 5 dpf was slightly increased in the psc37 mutant (Fig. 2F). At 6 dpf, only part of the eight nuclei enclosed by spore membranes were often observed in the psc37 mutant and more than one nucleus enclosed by one spore membrane were occasionally observed in the psc17 mutant (fig. S2). No obvious defects in nuclear division and ascospore delimitation were observed in the psc30 and psc52 mutants, indicating that many ascospores are likely dead during subsequent development possibly due to dysregulation of PCD. Therefore, PSC17, PSC37, PSC30, and PSC52 play important roles in ascosporogenesis.

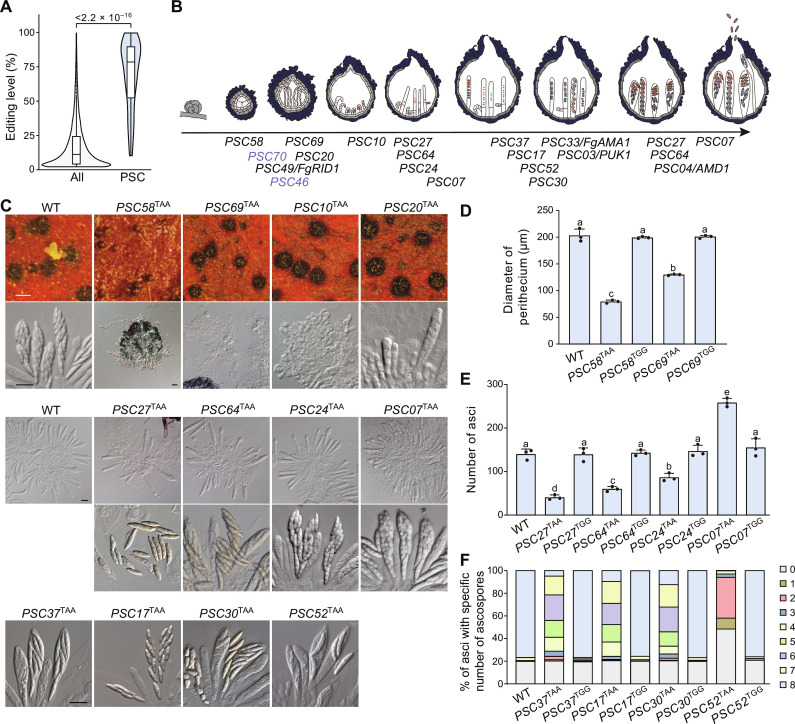

PSC editing is essential for the function of 16 germ-needed PSC pseudogenes

The median editing level of PSC-editing sites was 79% (Fig. 3A), which is over sixfold higher than that of all detected A-to-I editing sites in F. graminearum (19), suggesting the important roles of PSC editing on the functions of PSC pseudogenes during sexual development. Among the 18 germ-needed PSC pseudogenes, four PUK1, AMD1, FgAMA1, and FgRID1 have been shown to require PSC editing for their functions (13, 34, 35, 37). For the remaining 14, we generated uneditable mutant alleles in situ in PH-1 to determine the function of their PSC editing by changing the premature stop codon TAG to TAA. Transformants with the uneditable allele (TAA) for all PSC pseudogenes, except PSC46 and PSC70, exhibited similar defects in germ tissue development as corresponding deletion mutants (Fig. 3). These findings demonstrate the crucial role of PSC editing in the function of these PSC pseudogenes in germ tissues. For PSC46 and PSC70, we observed that transformants with the uneditable allele did not display any defects in sexual development (fig. S3). This suggests that PSC editing is not necessary for their functions. It is worth noting that the PSC-editing sites of PSC46 and PSC70 are located in the predicted C terminus of proteins (Fig. 1A), which is in contrast to the essential PSC-editing sites of other PSC pseudogenes, which are mostly located in the N-terminal of proteins or in or before the conserved domains, except for those in PSC37, PSC52, and PSC58.

Fig. 3. Critical roles of PSC editing in sexual development.

(A) Violin plots comparing editing levels of the PSC-editing sites and all the A-to-I editing sites identified in F. graminearum. The P value from the two-tailed Wilcoxon rank sum test is indicated. (B) Sexual developmental stages involved by PSC pseudogenes and their PSC editing. Gene names are given at the stages where mutant phenotypes occur in the corresponding mutants. PSC-editing sites that are not essential for gene functions are colored blue. (C) Mating cultures of the uneditable (TAA) transformants of germ-needed PSC pseudogenes were examined for perithecium formation (scale bar, 0.2 mm) and/or asci and ascospores morphology (scale bar, 20 μm) at 7 dpf. (D) The diameter of perithecia produced by the marked strains at 7 dpf. (E) The number of asci per perithecium produced by the marked strains at 5 dpf. For (D) and (E), mean and SD were calculated with data from three independent replicates (n = 3), each with at least 17 perithecia examined. Different letters indicate significant differences based on one-way ANOVA followed by Turkey’s multiple range test (P < 0.05). (F) The percentage of asci containing a specific number of ascospores produced by the marked strains at 7 dpf. The data are presented as the mean calculated from three independent replicates (n = 3), each with at least 80 asci examined.

To investigate whether the truncated versions of PSC pseudogenes have any function, we created edited mutant alleles in PH-1 by replacing the premature stop codon TAG with TGG. All transformants with the edited allele (TGG) exhibited normal sexual development, similar to the wild type (fig. S3). These findings confirm the restorative function of PSC editing and suggest that the full-length proteins of PSC pseudogenes alone can exhibit full functionality during sexual development, while the unedited truncated proteins do not appear to have any function.

The emergence of premature stop codons was facilitated by PSC editing

To investigate the origin of PSC pseudogenes in fungi, we searched for their homologs and orthologs across 546 fungal genomes. Our analysis revealed that orthologs of 57 (80%) PSC pseudogenes are present exclusively in Pezizomycotina (fig. S4). Particularly, 49 (69%) PSC pseudogenes had no detectable homologs outside of Pezizomycotina, indicating that most PSC pseudogenes are genetic innovations that underpin the evolution of complex multicellularity in filamentous ascomycetes. Among the 18 germ-needed PSC pseudogenes, 12 (67%) have emerged in Pezizomycotina and therefore play an important role in the evolution of fungal complex multicellularity. Note that PSC17 is a Fusarium-specific innovation important for ascosporogenesis.

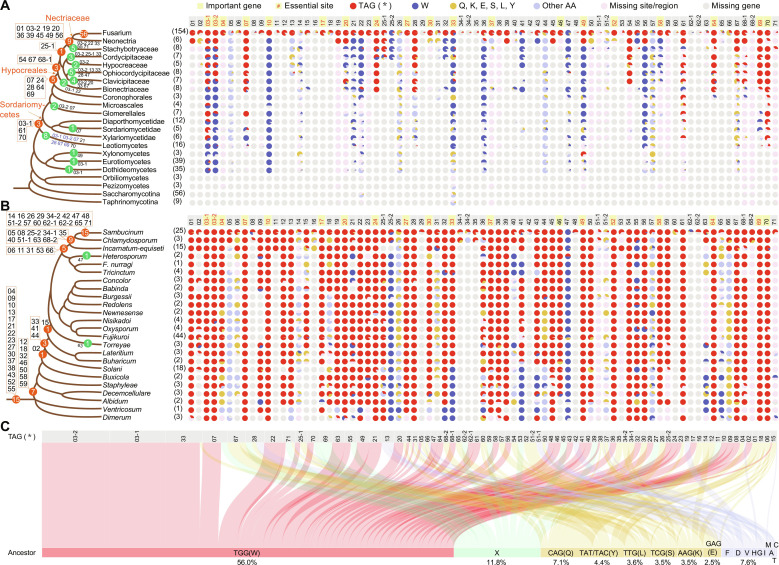

On the basis of the parsimonious principle, we inferred the evolutionary origin of the premature stop codon TAG at each PSC-editing site. All premature stop codons in the PSC pseudogenes in F. graminearum arose at different ancestral nodes in Sordariomycetes (Fig. 4, A and B, and figs. S5 and S6). In addition, we observed multiple independent occurrences of premature stop codons at the same sites in different lineages of Sordariomycetes. For example, six independent events of premature stop codon origin were observed in PSC33/FgAMA1 orthologs at the equivalent PSC-editing site. These observations, combined with the fact that A-to-I RNA editing is a common feature in Sordariomycetes and that the editing system originated in the last common ancestor of Sordariomycetes (15), suggest that the emergence of premature stop codons (pseudogenization) in ancestors of PSC pseudogenes is facilitated by PSC editing itself, as proposed by the CNE and harm-permitting model. Premature stop codons were also observed at several PSC-editing sites in individual species belonging to other classes in Pezizomycotina, where the presence of A-to-I RNA editing is yet to be determined.

Fig. 4. Origin and ancestral states of premature stop codons in PSC pseudogenes.

(A and B) Amino acid states at PSC-editing sites in the orthologous genes of the 71 PSC pseudogenes across different taxa of Ascomycota (A) and different species complexes of Fusarium (B). The number of species in each taxon examined is indicated in the bracket. Each pie chart shows the proportion of fungal species with a premature stop codon TAG (*), a postediting residue (W), a residue (Q, K, E, S, L, or Y) whose codon differs from TAG by only one base, other types of residues (other AA), missing the PSC-editing site/region, or missing the orthologous gene. The names of the 18 germ-needed PSC pseudogenes and the PSC-editing sites essential for their functions are highlighted by a yellow background and red font, respectively. On the phylogenetic tree, orange circles mark the origin of premature stop codons of the PSC pseudogenes in F. graminearum while green circles mark the independent origin of premature stop codons at the equivalent PSC-editing sites. The number in circles indicates the number of PSC-editing sites with the specific names shown in the box or next to the circle. Note that the premature stop codons at six of eight PSC-editing sites in Leotiomycetes were detected only in one single species Erysiphe necator (blue font). (C) Inferred ancestral amino acids/codons for each origin event of premature stop codon TAG (*) at the PSC-editing sites. The percentage of each type of amino acid/codon is shown. X, an undetermined amino acid.

The emergence of premature stop codons TAG in 61 PSC pseudogenes occurred long after the origin of the genes. Among these, 36 PSC pseudogenes originated before the A-to-I RNA editing system in Sordariomycetes. Only 10 PSC pseudogenes had PSC editing fixed immediately following their origin (Fig. 4). Among these, eight emerged in Fusarium, while the other two emerged in the last common ancestor of Fusarium and its closest related genus, Neonectria. These findings suggest that the ancestors of most PSC pseudogenes had already served their function before the fixation of PSC editing.

Ancestral amino acid state reconstruction revealed that TAG premature stop codons were mainly derived from the postedited amino acid codon TGG (W) via G-to-A mutation (Fig. 4C), in line with the CNE and harm-permitting model. It is worth noting that the TAG premature stop codons were often derived from non-TGG (W) codons by a single nucleotide mutation. This suggests that restoration of the function of PSC pseudogenes is not necessary to restore the ancestral amino acid residue.

Premature stop codons corrected by PSC editing are selectively favored over ancestral amino acid codons

If PSC editing is nonadaptive and the emergence of premature stop codons in ancestors of PSC pseudogenes is a result of genetic drift, we would expect the nonsynonymous substitution rate at PSC-editing sites in descendant species to be equal to or higher than the neutral substitution rate. This is because RNA editing is not 100% effective in correcting premature stop codons, whereas back mutations can fully restore the original genes. However, the premature stop codons of most PSC pseudogenes were generally conserved during evolution, particularly those in functionally important PSC pseudogenes with essential editing sites (Fig. 4, A and B). We identified 161 synonymous and 2744 nonsynonymous editing sites shared by F. graminearum (species complex Sambucinum) and F. neocosmosporiellum (species complex Solani) (table S4). Editing at these sites most likely occurred in the common ancestors of these two species complexes. For comparison, we randomly selected 77 synonymous and nonsynonymous shared editing sites each, which were equivalent to the PSC-editing sites. We also selected an equal number of synonymous and nonsynonymous shared editing sites with a TAG triplet (a T at the −1 position and a G at the +1 position), similar to the PSC-editing sites. We then estimated the frequency of nucleotide substitutions at each editing site in descendant species. Our analysis revealed that the nucleotide substitution frequency at PSC-editing sites was significantly lower compared to that at the shared synonymous editing sites with a TAG triplet (Fig. 5A), which are presumed to be neutral. Furthermore, the nucleotide substitution frequency at PSC-editing sites was even lower than that at the nonsynonymous editing sites with a TAG triplet. The nucleotide substitution frequency at the shared synonymous editing sites did not differ significantly from those with a TAG triplet, indicating that our sampling results do not affect the conclusion.

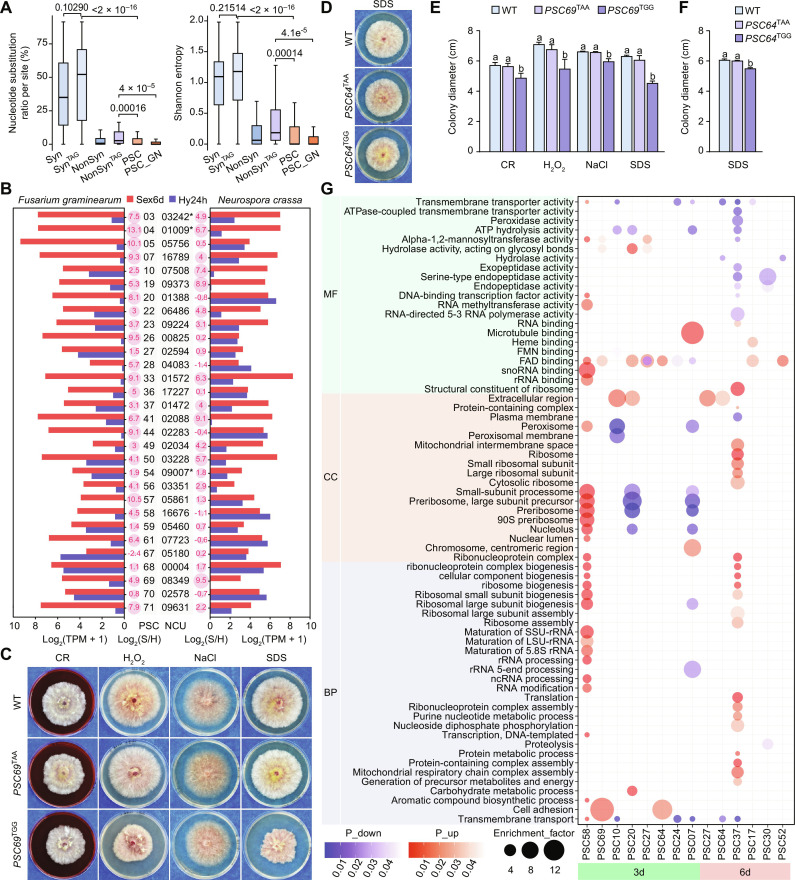

Fig. 5. Adaptive advantages of PSC editing.

(A) Boxplots comparing the nucleotide substitution frequency and Shannon entropy at each site in descendant species of the last common ancestor of F. graminearum and F. neocosmosporiellum among different groups. These groups include 44 shared PSC-editing sites (PSC_GN), 77 shared synonymous (Syn) and nonsynonymous (NonSyn) editing sites each, and 77 shared synonymous (SynTAG) and nonsynonymous (NonSynTAG) editing sites with a TAG triplet each between F. graminearum and F. neocosmosporiellum, as well as all 77 PSC-editing sites (PSC) in F. graminearum. P values from the two-tailed Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction are indicated. (B) Expression levels [Log2(TPM + 1)] of PSC pseudogene orthologs in F. graminearum and N. crassa during sexual reproduction (Sex6d) and vegetative growth (Hyp24h). The expression ratio of Sex6d compared with Hyp24h is shown as bubble maps with Log2(S/H) values. The star (*) indicates that the gene in N. crassa is also a PSC pseudogene. (C and D) Colonies of PH-1 (WT) and the uneditable (TAA) and edited (TGG) transformants of PSC69 and PSC64 formed on potato dextrose agar (PDA) with or without Congo red (150 μg/ml), 0.05% H2O2, 0.7 M NaCl, and 0.01% SDS after incubation for 3 or 5 days. (E and F) Colony diameters of the marked strains. Mean and SD were calculated with data from three biological replicates (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences based on one-way ANOVA followed by Turkey’s multiple range test (P < 0.05). (G) Enriched Gene Ontology (GO) terms in up- or down-regulated DEGs of each sample. MF, molecular function; CC, cell component; BP, biological process.

In addition, we calculated Shannon entropy for each editing site as a measure of nucleotide conservation. The lower the Shannon entropy, the higher the conservation. Our results showed that compared to the synonymous and nonsynonymous editing sites with a TAG triplet, the Shannon entropy was significantly lower for PSC-editing sites (Fig. 5A). Among the 44 PSC-editing sites shared by F. graminearum and F. neocosmosporiellum, the nucleotide substitution frequency and Shannon entropy were even lower. These findings indicate that PSC editing is more likely to be retained during evolution compared to synonymous and nonsynonymous editing. Therefore, natural selection favors the correction of premature stop codons by PSC editing over the direct encoding of ancestral amino acid codons in the genome. However, it is worth noting that premature stop codons in certain PSC pseudogenes have been lost in some lineages during evolution (Fig. 4). In some cases, these lost premature stop codons were later reacquired during subsequent evolution. This suggests that the preference for premature stop codons over amino acid codons is context dependent and may not remain consistent throughout evolution.

Ancestral versions of PSC64 and PSC69 have antagonistic effects on reproduction and survival

Why is PSC editing preferred over encoding the ancestral amino acid codons directly in the genome? According to RNA-seq data, while most PSC pseudogenes were up-regulated during sexual development, they were also expressed in other stages, with transcripts of some PSC pseudogenes being abundant in hyphae (Figs. 1A and 5B). Although not pseudogenes, the orthologs of these PSC pseudogenes in N. crassa were also expressed during growth (Fig. 5B), suggesting that the expression of PSC pseudogenes outside of sexual stages represents the ancestral state. On the basis of this evidence, we speculated that the ancestral unmutated versions of these PSC pseudogenes may have antagonistic pleiotropic effects, meaning that they are necessary for sexual stages but may be harmful to other stages.

We assessed whether the expression of the ancestral unmutated versions (represented by the edited versions) of PSC pseudogenes could be harmful to vegetative growth, especially under stressful conditions. The defects of transformants with the edited (TGG) and uneditable (TAA) alleles of 12 germ-needed PSC pseudogenes with essential PSC-editing sites were examined in response to hyperosmotic (NaCl), oxidative (H2O2), cell membrane (SDS), and cell wall (Congo red) stresses. As expected, the growth rates of all the uneditable transformants had no significant alterations in the assayed stressful conditions compared with the wild type (Fig. 5, C to F, and figs. S7 to S9). However, the edited transformants of PSC69 displayed increased sensitivity to various stresses, particularly to the cell membrane stress (Fig. 5, C and D and fig. S9). Its growth was significantly reduced under stressful conditions in comparison with the wild type and edited transformants. The edited transformant of PSC64 was also hypersensitive to the cell membrane stress. The results demonstrated that expressing the ancestral unmutated versions of either PSC69 or PSC64 causes harmful effects on growth under stressful conditions. Therefore, the ancestors of PSC69 and PSC64 are bona fide life-history trade-off genes with antagonistic effects on reproduction and survival. Pseudogenization and sexual stage–specific PSC editing of these trade-off genes during evolution resolve the trade-offs caused by their antagonistic pleiotropy.

The orthologs of PSC69 are widely distributed in Sordariomycetes and occur also in individual species in Leotiomycetes, the sister class of Sordariomycetes. The orthologs of PSC64 are present in the orders Hypocreales and Coronophorales within Sordariomycetes. However, the emergence of PSC editing in both genes occurred only in the last common ancestor of Hypocreales (Fig. 4). This suggests that the selection pressure for the emergence of PSC editing in PSC69 and PSC64, driven by their antagonistic effects, was strong in the last common ancestor of Hypocreales.

The germ-needed PSC pseudogenes are implicated in regulating stress response

Of all the germ-needed pseudogenes characterized in this study that require PSC editing for their functions, only PSC20, PSC24, and PSC37 encode proteins with known functional domains. PSC24 encodes a Rho (Ras homologous) guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) while PSC37 encodes a Rho GTPase-activator protein (RhoGAP), suggesting their involvement of small GTPase signaling (38). PSC20 encodes a protein homologous to α-1,2-mannosyltransferases that are involved in protein glycosylation, a critical function of the secretory pathway (39). The remaining pseudogenes, such as PSC64 and PSC69, encode hypothetical proteins that contain only IDRs. These IDRs are known to have a broad range of regulatory functions, such as binding other proteins, interacting with nucleic acids, or serving as scaffold proteins (33).

To investigate the potential cellular processes that these genes are involved in during sexual development, we conducted RNA-seq analyses of their deletion mutants. A various number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified in these mutants (fig. S10). On the basis of the Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis, it was found that cell adhesion, which is involved in signal transduction that allows cells to detect and respond to environmental changes (40), was significantly enriched in the up-regulated DEGs of the psc69 and psc64 mutants (Fig. 5G). This suggests that PSC69 and PSC64 act as negative regulators of environmental response. GO terms associated with activities of transmembrane transporters, α-1,2-mannosyltransferases, endo−/exopeptidases, peroxidases, and adenosine triphosphate hydrolysis were overrepresented in down-regulated DEGs in the psc37 mutant (Fig. 5G). DEGs down-regulated in the psc24 mutant were enriched for “transmembrane transporter activity” and “FAD binding.” GO terms “FAD binding,” “hydrolase activity, acting on glycosyl bonds,” and “extracellular region” were enriched in up-regulated DEGs in the psc20 mutant. Related GO terms were also enriched in the up- or down-regulated DEGs in the other 9 mutants. Particularly, the “transmembrane transporter activity,” “FAD binding,” and “extracellular region” were the commonly enriched terms in these mutants. FAD is a redox-active coenzyme associated with various flavoprotein oxidoreductases, and peroxidases are a group of oxidoreductases localized in peroxisomes. Both are involved in redox and oxidative stress. Other enriched functions are likely related to membrane trafficking (secretory, vacuolar transport, and endocytic) pathways that play pivotal roles in environmental response (41). The membrane trafficking system has also been speculated to be involved in spore delimitation and ascus/ascospore-wall synthesis (42), and implicated in PCD (43, 44). Dysregulation of membrane trafficking may partially explain the observed defects in ascus-ascospore formation and maturation in the mutants.

Numerous GO terms associated with ribosome biogenesis in the nucleolus were enriched in up-regulated DEGs in the psc58 mutant (Fig. 5G). PSC58 encodes a protein of unknown function with a DUF3716 domain. It is orthologous to a telomeric sequence-binding protein NCU05718 in N. crassa (45). Dysfunctional telomeres caused by telomere shortening elicit a DNA damage response (46). Ribosome biogenesis must respond rapidly to environmental cues and turn “on” or “off” signal transduction pathways is critical in response to environmental stimuli. Consistent with previous reports that some small GTPases are involved in ribosome assembly (47, 48) and disruption of protein glycosylation results in activation of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress coping response (49), GO terms related to ribosome biogenesis were enriched in up-regulated DEGs in the psc37 mutant and down-regulated DEGs in the psc20 mutants. The down-regulated DEGs of the psc07 mutant at 3 dpf were also enriched for GO terms related to ribosome biogenesis.

Collectively, these germ-needed PSC pseudogenes participate in various cellular processes that may be involved in responding to environmental stress. Given that stress conditions can induce various life-history trade-offs, it is possible that, in addition to PSC69 and PSC64, the ancestral unmutated versions of other PSC pseudogenes may also act as trade-off genes for survival and reproduction under specific untested environmental conditions, although their edited transformants did not show significant alterations in sensitivity to the tested stressful conditions.

DISCUSSION

Uncovering the genetic principles of evolution toward increased biological complexity remains a major challenge for evolutionary and developmental biology. Pezizomycotina is the largest fruiting-body-forming lineage in fungi with an independent origin of complex multicellularity (50, 51), but the genetic underpinnings are limited understanding. In multicellular animals and plants, co-option of existing genes has been proposed to be a major contributor to the evolution of multicellularity and cell differentiation whilst de novo gene evolution plays a minor role (52, 53). Concordantly, recent comparative genomic and transcriptomic analyses of different fungal lineages revealed that both simple hyphae and complex fruiting bodies evolved by limited fungal-specific innovations but dominant co-option of existing genes (24, 51, 54–57). In this study, we showed that 18 genes are important for the differentiation and development of germ tissues inside perithecia (fruiting bodies) in F. graminearum. Among these, six are likely co-opted into germ tissues during the evolution of sexual fruiting bodies in Pezizomycotina. PSC03/PUK1 encodes a protein kinase important for ascosporogenesis in both F. graminearum and N. crassa (13, 18). PSC49/FgRID1 is the ortholog of RID that mediates repeat-induced point mutation, a sexual-specific genome defense mechanism in Pezizomycotina (36). The orthologs of both genes occur also in Basidiomycota but were lost in unicellular yeasts. PSC33/FgAMA1 and PSC37 are the only ones with orthologs in unicellular yeasts. Although orthologous to Ama1, an activator of the meiotic anaphase-promoting complex in budding yeasts, FgAma1 has no meiosis-specific roles but is necessary for ascospore morphogenesis (34). PSC37 encodes a RhoGAP important for ascosporogenesis, but its ortholog Rga6 is involved in the regulation of polarized growth in fission yeasts (58). PSC24 and PSC20 encode a Rho GTPase and an α-1,2-mannosyltransferase, respectively; both are important for ascogenous hypha development and likely derived from gene duplication. Unexpectedly, 12 germ-needed genes are evolutionary innovations for sexual fruiting bodies in Pezizomycotina. Of these, PSC04/AMD1 encodes a major facilitator superfamily protein important for ascus maturation (35). PSC58 encodes a potential telomeric factor essential for ascogenous hypha formation. The rest of the 10 germ-needed genes encode hypothetical proteins without known function domains. Nevertheless, they are important for germ tissue development potentially as regulators of cell adhesion, membrane trafficking, and/or redox. In addition, the deletion of several genes (PSC46, PSC30, PSC52, etc.) caused unprogrammed degradation of germ tissues, indicating that they may participate in regulating PCD. Because previous phylogenetic and genomic studies proposed that cell adhesion, membrane systems, cell signaling, and PCD are pivotal to the evolution of complex multicellularity (51, 52), our results demonstrate that beyond co-option, genetic innovations of regulators of these processes contribute importantly to the evolution and development of sexual fruiting bodies in Pezizomycotina.

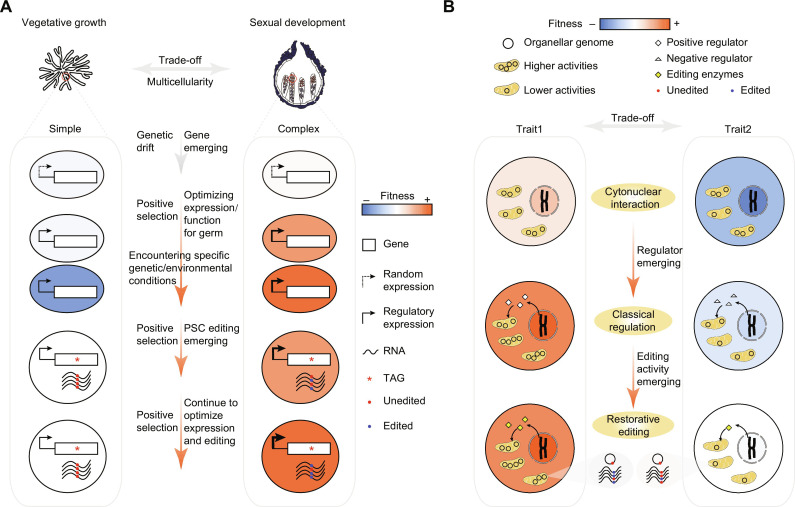

Why and how did these genes evolve into germ-needed regulators? In fungi, stressful conditions commonly trigger sexual reproduction because the sexual fruiting body itself serves as a survival structure and the generation of genotypic diverse offspring can ensure long-term survival (59). Therefore, the ability to trade off vegetative growth (survival) for sexual reproduction in response to stress can be beneficial for fungi. The engaged cellular processes by the germ-needed genes are potentially involved in stress response. In particular, expressing the ancestral versions of PSC69 and PSC64 caused increased sensitivity to stresses during vegetative growth. In addition, PSC68, PSC19, and PSC57 encode a universal stress protein, a DNA mismatch repair protein, and a stress-responsive DEAD-like helicase, respectively, although their mutants had no detectable defects. The incidental acquisition of functions in stress response, either through de novo emergence or modification of existing genes, can be expected to be deleterious to immediate survival, as pre-existing stress response mechanisms have been optimized for adaptation to the current circumstances. However, when these genes have larger beneficial effects on sexual reproduction, despite causing negative effects on growth in stressful environments, they can be favored by natural selection and gradually evolve into regulators of germ tissues in fruiting bodies by changing their expression from an incidental context to a spatiotemporally/developmental context (Fig. 6A). An important role of stress responses in the evolution of biological complexity has been proposed in green algae and humans (60, 61). The discovery of these germ-needed regulators involved in survival-reproduction trade-offs has improved our understanding of the evolution of complex multicellularity and life-history strategies in fungi.

Fig. 6. Proposed models for the adaptive advantages of PSC editing in fungi and organellar restorative editing.

(A) The proposed model illustrates the evolution of PSC pseudogenes and the adaptive advantages of PSC editing. Filamentous ascomycetes grow vegetatively as mycelia (simple multicellularity) but often trade off growth for reproduction to produce fruiting bodies (complex multicellularity) in response to environmental stress. PSC pseudogenes’ ancestors arose through de novo birth or gene duplication. They acquired functions beneficial for sexual development but detrimental for growth under stress, leading to survival-reproduction trade-offs. Natural selection may prioritize sexual development over vegetative growth to maximize overall fitness. Over time, the expression and function of these ancestral trade-off genes gradually optimized for sexual development by transitioning from an incidental context to a developmental context. In specific genetic or environmental conditions, the strength of survival-reproduction trade-offs substantially increased, leading to the emergence of PSC editing when the A-to-I RNA editing system is available. As a result, PSC pseudogenes evolved, no longer negatively affecting growth but retaining advantages for sexual development. Their expression and editing levels can be further optimized. This process ultimately maximizes the overall fitness of fungi through the emergence of survival-reproduction trade-off genes and their PSC editing. (B) The proposed model illustrates how restorative editing in organelles is adaptive. Uncontrolled mitochondrial activity may be advantageous for one trait but detrimental for another. Numerous nucleus-encoded factors have evolved to tightly regulate gene expression in organelles, including the RNA editing enzymes. The mutagenic effects of RNA editing lead to the accumulation of mutations in organellar genomes. These mutations need to be repaired by the RNA editing enzymes encoded by the nucleus. Therefore, restorative editing serves as a convenient mechanism for nuclei to counteract the self-interest of organelles and resolve trade-offs arising from cytonuclear conflict.

Why did these life-history trade-off genes evolve into PSC pseudogenes? It is possible to resolve trade-offs between reproduction and survival through precise germ-specific optimization of gene expression using classical gene regulation mechanisms, such as cis- and trans-regulatory mutations. However, these mechanisms may only be efficient under strong selection pressures (62). These life-history trade-off genes have minor negative effects on growth under specific conditions but play a crucial role in sexual development. Natural selection tends to prioritize the optimization of these genes for sexual development rather than growth, leading to suboptimal expression during growth. This situation is similar to the trade-offs observed in aging). In addition, classical gene regulation mechanisms cannot completely prevent the expression and function of genes outside of sexual development due to inherent gene expression noise in biological systems (63). These life-history trade-off genes are indeed expressed outside of sexual development. In Sordariomycetes, the sexual stage–specific A-to-I RNA editing system originated in their last common ancestor (15). The editing capability promotes the pseudogenization of these ancestral life-history trade-off genes during evolution in Sordariomycetes by the fixation of premature stop codons. The resulting PSC pseudogenes are inactive outside sexual reproduction but become active in germ tissues after editing (Fig. 6A). Therefore, when the editing system is available and the life-history trade-off genes have accessible sites, PSC editing is a cost-effective solution to block gene expression and function outside of sexual development and eliminate trade-offs. Notably, yeast AMA1 contains an intron that is spliced specifically in meiotic cells (64). This suggests that intron splicing likely evolved independently in yeasts that lack the A-to-I RNA editing system to resolve trade-offs between reproduction and survival.

Is PSC editing adaptive in fungi? We propose that the emergence of PSC editing in fungi is driven by genetic trade-offs. PSC editing is adaptive in fungi as it eliminates the survival costs of reproduction. During evolution, PSC editing is generally selectively favored over the original genomic G. This adaptive model assumes that gene maturation in terms of function and expression, as well as the manifestation of trade-offs, occurs before the emergence of PSC editing. Alternatively, a neutral model suggests that PSC editing emerges immediately after gene origin and may be fixed by drift due to low expression and weak trade-offs. After fixation, genes mature during evolution without negatively affecting growth. PSC editing may be neutral at the time of fixation but becomes indispensable later in evolution. While we do not rule out the possibility proposed by the neutral model, it is less likely compared to our adaptive model, as premature stop codons in most PSC pseudogenes occurred long after gene origin. Furthermore, the manifestation of trade-offs can be influenced by various factors, including genetic background and environmental conditions (20), and therefore, trade-offs may not be consistently expressed throughout evolution after gene origin. The strength of trade-offs can vary across different fungal lineages and over different periods of evolution. It is worth noting that PSC editing levels are not 100%, which means that it may be less beneficial than the original genomic G in sexual development, although it may be more beneficial in growth. When the harm to growth is weak, having a genomically encoded G appears to be more advantageous. Conversely, when the harm to growth is strong, having a restorative editing mechanism seems to be more beneficial. Therefore, natural selection may balance between PSC editing and the genomically encoded G to optimize overall fitness based on the strength of trade-offs during evolution. The observation that multiple independent fixations of the same premature stop codons have occurred across different fungal lineages, and that premature stop codons have been lost during evolution and later reacquired in some cases, supports the adaptive model but is incompatible with the neutral model.

Is resolving genetic trade-offs also the adaptive function of organellar restorative editing? Restorative editing is prevalent in endosymbiotic organelles, while the enzymes responsible are encoded in the nucleus. Despite longstanding coadaptation, the presence of independently replicating organellar genomes (e.g., mitochondria and chloroplasts) in eukaryotes creates the opportunity for selfish cytonuclear conflict. This conflict can have a substantial impact on cellular functions and the optimal expression of life-history traits, especially in changing environments (65, 66) (Fig. 6B). To combat selfishness and promote coordinated cytonuclear interactions, nuclear genomes have developed numerous regulatory factors that enter the organelles to regulate their gene expression (67). The spontaneous occurrence of RNA editing activity leads to the accumulation of mutations in organellar genomes, necessitating correction by nuclear-encoded editing enzymes. Restorative editing offers nuclear genomes a convenient means to counteract the self-interest of organellar genomes and optimize cytonuclear interactions, thereby maximizing cellular fitness overall. In conclusion, restorative editing potentially acts as an adaptive mechanism to resolve trade-offs stemming from antagonistic pleiotropy or cytonuclear conflict. Genetic trade-offs may represent the primary driving force behind the origin and maintenance of diverse RNA editing systems.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strain culture conditions

We routinely cultured the F. graminearum wild-type strain PH-1 and its derived mutants/transformants on potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates at 25°C to assay the growth rate and colony morphology for 3 days. To assay the sensitivity to different stresses, we cultured the strains on PDA plates supplemented with Congo red (150 μg/ml), 0.05% H2O2, 0.7 M NaCl, or 0.01% SDS for 5 days, as described in (68). For sexual reproduction, we pressed down aerial hyphae on 6-day-old carrot agar plates (250 g/liter) with 500 μl of sterile 0.1% Tween 20 and subsequently incubated them under black light at 25°C. In outcrosses, we fertilized female strains grown on carrot agar plates with 1 ml of conidial suspension (1 × 106 conidia/ml) derived from male strains. We assayed ascospore discharge as described in (69). We measured conidiation in 5-day-old liquid carboxymethylcellulose cultures and assayed spore germination and germ tube growth in liquid YEPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose) medium for 12 hours using freshly harvested conidia or ascospores. We examined perithecium formation, cirrhi production, and spore firing by an Olympus SZX16 stereoscope. We observed the morphology of conidia, germ tubes, ascogenous hyphae, asci, and ascospores with an Olympus BX-51 microscope.

Gene deletion and site-directed mutagenesis

We performed gene deletion using the split-marker approach (70) as described in (68). We transformed gene deletion constructs into PH-1 protoplasts and screened transformants resistant to hygromycin with hygromycin-B (300 μg/ml; H005, MDbio, China), confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays. For each PSC pseudogene, we identified at least two independent deletion mutants. We performed site-directed mutagenesis in situ as described in (32). We generated uneditable and edited alleles of the PSC pseudogenes by replacing the premature stop codon TAG with TAA and TGG, respectively, using overlapping PCR. We fused the allelic fragment and the downstream fragment of the target gene to the N- and C-terminal regions of the hygromycin-resistance gene (hyg), respectively. We cotransformed the two fused fragments into PH-1 protoplasts and identified hygromycin-resistant transformants by PCR. We confirmed desired mutations by DNA sequencing and identified transformants with no unintended integration of allelic fragments by quantitative PCR. All mutant strains and primers used are listed in tables S2 and S5, respectively.

RNA-seq analysis

We harvested perithecium samples from carrot agar cultures with at least two biological replicates per treatment condition. We extracted total RNA using the RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (Tiangen Biotech) and enriched poly (A)+ mRNA with oligo (dT) magnetic beads. We constructed strand-specific RNA-seq libraries with the NEBNext Ultra Directional RNA Library Prep Kit (New England Biolabs) and sequenced them by Illumina HiSeq 2500 with the 2 × 150-bp paired-end read mode at the Novogene Bioinformatics Institute (Beijing). For each library, we obtained at least 20 Mb of high-quality reads. We downloaded published RNA-seq data from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive database. All the RNA-seq data used in this study are listed in table S6 together with their accession numbers. We obtained the latest genome sequences and gene annotations of PH-1 from FgBase (http://fgbase.wheatscab.com/) and those of F. neocosmosporiellum from the NCBI genome database. We aligned RNA-seq reads to the reference genome using HISAT2 (71) with a two-step model and evaluated the quality of read alignments using Qualimap 2 (72). We identified A-to-I RNA editing sites as described previously (73). We calculated count data of gene expression by featureCounts (74) and performed differential gene expression analysis with edgeRun (75) using Benjamini and Hochberg’s algorithm to control the false discovery rate (FDR). We considered genes with FDR < 0.05 and |log2 (fold change)| ≥ 1 as DEGs. We measured gene expression levels using transcripts per million (TPM). We performed GO enrichment analysis with TBtools (76) using a cutoff for p_adjusted <0.05.

Homology searching and phylogenetic analysis

We identified conserved domains and IDRs in protein sequences using NCBI CD-Search (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) and InterProScan (www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/search/sequence/), respectively. We identified homologs of the PSC pseudogenes in 546 fungal genomes by tBLASTn using the edited protein sequences and detected homologous sequences as queries for iterative searching in the NCBI wgs database. We considered only the best hit with e value <1 × e−5 in each genome as homologs. We determined gene orthologous relationships by reciprocal BLAST searches. We recorded amino acid states at the corresponding PSC-editing site in orthologs based on tBLASTn alignments. We identified synonymous and nonsynonymous editing sites shared by F. graminearum and F. neocosmosporiellum based on the alignments of ortholog pairs.

We downloaded genome sequences of 154 species from the genus Fusarium from the NCBI Genome database. We predicted the 19 housekeeping genes used to infer the Fusarium phylogeny (77) from each genome using genBlastG1.39 (78). We obtained protein sequences of the γ-tubulin gene (79) encoded by species outside of Fusarium by tBLASTn searches of the NCBI wgs database. We performed multiple alignments of protein sequences using the ClustalW algorithm implemented in MEGA11 (80). Phylogenetic trees were constructed using MEGA11 with the neighbor-joining method. We concatenated alignments of the 19 housekeeping genes into one alignment for phylogenetic analysis. Dendrograms illustrating relationships between major groups of fungi were drawn according to the MycoCosm tree (https://mycocosm.jgi.doe.gov/mycocosm/home). The phylogenetic tree of different fungal taxa was drawn on the basis of both the MycoCosm tree and the γ-tubulin tree. We inferred ancestral states at PSC-editing sites using MEGA11 with the maximum parsimony method and the topology of phylogenetic trees. For each ancestral editing site, we calculated the frequency of nucleotide substitutions as the percentage of descendant species containing a non-A nucleotide at that site. Shannon entropy was evaluated as H(X) = −∑ xi log2xi, where X is a series of frequencies of nucleotides at an editing site with four possible values {x1, ⋯, x4} for nucleotide sequences.

Statistical analyses

We performed all statistical analyses using R or GraphPad Prism 8. Details of each statistical test are included in the figure legends. Sample sizes and P values are also included in the figure legends or main figures.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Wang, P. Xiang, and Z. Tang for laboratory assistance.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFD1400100) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 32170200).

Author contributions: Conceptualization: H.L. and Z.Q. Methodology: H.L., Z.Q., P.L., and X.C. Investigation: Z.Q., P.L., X.L., X.C., M.W., K.X., T.X., X.G., Y.H., Q.W., and C.J. Visualization: Z.Q., X.L., M.W., K.X., T.X., and X.G. Supervision: H.L. and J.-R.X. Writing—original draft: H.L. and Z.Q. Writing—review and editing: H.L., Z.Q., and J.-R.X.

Competing interests: The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: RNA-seq data generated in this study are accessible under the accession numbers SRR24757046 to SRR24757051 and SRR24757058 to SRR24757084. All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S10

Legends for tables S1 to S6

References

Other Supplementary Material for this manuscript includes the following:

Tables S1 to S6

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Lukes J., Kaur B., Speijer D., RNA editing in mitochondria and plastids: Weird and widespread. Trends Genet. 37, 99–102 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bian Z., Ni Y., Xu J. R., Liu H., A-to-I mRNA editing in fungi: Occurrence, function, and evolution. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 76, 329–340 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenberg E., Levanon E. Y., A-to-I RNA editing - immune protector and transcriptome diversifier. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19, 473–490 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benne R., Van den Burg J., Brakenhoff J. P., Sloof P., Van Boom J. H., Tromp M. C., Major transcript of the frameshifted coxII gene from trypanosome mitochondria contains four nucleotides that are not encoded in the DNA. Cell 46, 819–826 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chateigner-Boutin A. L., Small I., Organellar RNA editing. Wiley Interdiscip Rev. RNA 2, 493–506 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maier U. G., Bozarth A., Funk H. T., Zauner S., Rensing S. A., Schmitz-Linneweber C., Borner T., Tillich M., Complex chloroplast RNA metabolism: Just debugging the genetic programme? BMC Biol. 6, 36 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castandet B., Araya A., The nucleocytoplasmic conflict, a driving force for the emergence of plant organellar RNA editing. IUBMB Life 64, 120–125 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray M. W., Evolutionary Origin of RNA Editing. Biochemistry 51, 5235–5242 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang D., Zhang J., The preponderance of nonsynonymous A-to-I RNA editing in coleoids is nonadaptive. Nat. Commun. 10, 5411 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tian N., Wu X., Zhang Y., Jin Y., A-to-I editing sites are a genomically encoded G: Implications for the evolutionary significance and identification of novel editing sites. RNA 14, 211–216 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright A., Vissel B., The essential role of AMPA receptor GluR2 subunit RNA editing in the normal and diseased brain. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 5, (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lukes J., Archibald J. M., Keeling P. J., Doolittle W. F., Gray M. W., How a Neutral Evolutionary Ratchet Can Build Cellular Complexity. IUBMB Life 63, 528–537 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu H., Wang Q., He Y., Chen L., Hao C., Jiang C., Li Y., Dai Y., Kang Z., Xu J. R., Genome-wide A-to-I RNA editing in fungi independent of ADAR enzymes. Genome Res. 26, 499–509 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teichert I., Dahlmann T. A., Kuck U., Nowrousian M., RNA Editing During Sexual Development Occurs in Distantly Related Filamentous Ascomycetes. Genome Biol. Evol. 9, 855–868 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.C. Feng, K. Xin, Y. Du, J. Zou, X. Xing, Q. Xiu, Y. Zhang, R. Zhang, W. Huang, Q. Wang, Unveiling the A-to-I mRNA editing machinery and its regulation and evolution in fungi. bioRxiv 2023.10.18.562923. [Preprint]. 19 October 2023. 10.1101/2023.10.18.562923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Peraza-Reyes L., Malagnac F., 16 Sexual Development in Fungi. Growth Differ. Sexual., 407–455 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 17.West S. A., Fisher R. M., Gardner A., Kiers E. T., Major evolutionary transitions in individuality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 10112–10119 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu H., Li Y., Chen D., Qi Z., Wang Q., Wang J., Jiang C., Xu J. R., A-to-I RNA editing is developmentally regulated and generally adaptive for sexual reproduction in Neurospora crassa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E7756–E7765 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng C., Cao X., Du Y., Chen Y., Xin K., Zou J., Jin Q., Xu J. R., Liu H., Uncovering Cis-regulatory elements important for a-to-i rna editing in fusarium graminearum. mBio 13, e0187222 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maklakov A. A., Chapman T., Evolution of ageing as a tangle of trade-offs: Energy versus function. P. Roy. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 286, 20191604 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yanni D., Jacobeen S., Marquez-Zacarias P., Weitz J. S., Ratcliff W. C., Yunker P. J., Topological constraints in early multicellularity favor reproductive division of labor. eLife 9, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michod R. E., The group covariance effect and fitness trade-offs during evolutionary transitions in individuality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 9113–9117 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernardes J. P., John U., Woltermann N., Valiadi M., Hermann R. J., Becks L., The evolution of convex trade-offs enables the transition towards multicellularity. Nat. Commun. 12, 4222 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagy L. G., Varga T., Csernetics A., Viragh M., Fungi took a unique evolutionary route to multicellularity: Seven key challenges for fungal multicellular life. Fungal Biol. Rev. 34, 151–169 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lang G. I., Murray A. W., Botstein D., The cost of gene expression underlies a fitness trade-off in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 5755–5760 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Avelar A. T., Perfeito L., Gordo I., Ferreira M. G., Genome architecture is a selectable trait that can be maintained by antagonistic pleiotropy. Nat. Commun. 4, 2235 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Austad S. N., Hoffman J. M., Is antagonistic pleiotropy ubiquitous in aging biology? Evol. Med. Public Health 2018, 287–294 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flatt T., Life-history evolution and the genetics of fitness components in drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 214, 3–48 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saggere R. M. S., Lee C. W. J., Chan I. C. W., Durnford D. G., Nedelcu A. M., A life-history trade-off gene with antagonistic pleiotropic effects on reproduction and survival in limiting environments. Proc. Biol. Sci. 289, 20212669 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trail F., For blighted waves of grain: Fusarium graminearum in the postgenomics era. Plant Physiol. 149, 103–110 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu P., Chen D., Qi Z., Wang H., Chen Y., Wang Q., Jiang C., Xu J. R., Liu H., Landscape and regulation of alternative splicing and alternative polyadenylation in a plant pathogenic fungus. New Phytol. 235, 674–689 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xin K., Zhang Y., Fan L., Qi Z., Feng C., Wang Q., Jiang C., Xu J. R., Liu H., Experimental evidence for the functional importance and adaptive advantage of A-to-I RNA editing in fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 120, e2219029120 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oldfield C. J., Dunker A. K., Intrinsically disordered proteins and intrinsically disordered protein regions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 83, 553–584 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hao C. F., Yin J. R., Sun M. L., Wang Q. H., Liang J., Bian Z. Y., Liu H. Q., Xu J.-R., The meiosis-specific APC activator FgAMA1 is dispensable for meiosis but important for ascosporogenesis in Fusarium graminearum. Mol. Microbiol. 111, 1245–1262 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cao S. L., He Y., Hao C. F., Xu Y., Zhang H. C., Wang C. F., Liu H. Q., Xu J. R., RNA editing of the AMD1 gene is important for ascus maturation and ascospore discharge in Fusarium graminearum. Sci. Rep. 7, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pomraning K. R., Connolly L. R., Whalen J. P., Smith K. M., Freitag M., Repeat-induced point mutation, DNA methylation and heterochromatin in Gibberella zeae (anamorph: Fusarium graminearum). Fusarium Genomics. Mol. Cell. Biol. 93, 193 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang C., Xu J. R., Liu H., A-to-I RNA editing independent of ADARs in filamentous fungi. RNA Biol. 13, 940–945 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heasman S. J., Ridley A. J., Mammalian Rho GTPases: New insights into their functions from in vivo studies. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 690–701 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lussier M., Sdicu A. M., Bussey H., The KTR and MNN1 mannosyltransferase families of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1426, 323–334 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gumbiner B. M., Cell adhesion: The molecular basis of tissue architecture and morphogenesis. Cell 84, 345–357 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang X., Xu M., Gao C., Zeng Y., Cui Y., Shen W., Jiang L., The roles of endomembrane trafficking in plant abiotic stress responses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 62, 55–69 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Read N. D., Beckett A., Ascus and ascospore morphogenesis. Mycol. Res. 100, 1281–1314 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bento C. F., Puri C., Moreau K., Rubinsztein D. C., The role of membrane-trafficking small GTPases in the regulation of autophagy. J. Cell Sci. 126, 1059–1069 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soreng K., Neufeld T. P., Simonsen A., Membrane trafficking in autophagy. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 336, 1–92 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Casas-Vila N., Scheibe M., Freiwald A., Kappei D., Butter F., Identification of TTAGGG-binding proteins in, a fungus with vertebrate-like telomere repeats. Bmc Genomics 16, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin J., Epel E., Stress and telomere shortening: Insights from cellular mechanisms. Ageing Res. Rev. 73, 101507 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karbstein K., Role of GTPases in ribosome assembly. Biopolymers 87, 1–11 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hauryliuk V. V., GTPases of the prokaryotic translation apparatus. Mol. Biol. 40, 688–701 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Q., Groenendyk J., Michalak M., Glycoprotein quality control and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Molecules 20, 13689–13704 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Naranjo-Ortiz M. A., Gabaldon T., Fungal evolution: Cellular, genomic and metabolic complexity. Biol. Rev. 95, 1198–1232 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nagy L. G., Kovacs G. M., Krizsan K., Complex multicellularity in fungi: Evolutionary convergence, single origin, or both? Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 93, 1778–1794 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Knoll A. H., The Multiple Origins of Complex Multicellularity. Annu. Rev. Earth Pl. Sc. 39, 217–239 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brunet T., King N., The origin of animal multicellularity and cell differentiation. Dev. Cell 43, 124–140 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nguyen T. A., Cisse O. H., Yun Wong J., Zheng P., Hewitt D., Nowrousian M., Stajich J. E., Jedd G., Innovation and constraint leading to complex multicellularity in the Ascomycota. Nat. Commun. 8, 14444 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kiss E., Hegedus B., Viragh M., Varga T., Merenyi Z., Koszo T., Balint B., Prasanna A. N., Krizsan K., Kocsube S., Riquelme M., Takeshita N., Nagy L. G., Comparative genomics reveals the origin of fungal hyphae and multicellularity. Nat. Commun. 10, 4080 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lutkenhaus R., Traeger S., Breuer J., Carrete L., Kuo A., Lipzen A., Pangilinan J., Dilworth D., Sandor L., Poggeler S., Gabaldon T., Barry K., Grigoriev I. V., Nowrousian M., Comparative genomics and transcriptomics to analyze fruiting body development in filamentous ascomycetes. Genetics 213, 1545–1563 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Krizsan K., Almasi E., Merenyi Z., Sahu N., Viragh M., Koszo T., Mondo S., Kiss B., Balint B., Kues U., Barry K., Cseklye J., Hegedus B., Henrissat B., Johnson J., Lipzen A., Ohm R. A., Nagy I., Pangilinan J., Yan J., Xiong Y., Grigoriev I. V., Hibbett D. S., Nagy L. G., Transcriptomic atlas of mushroom development reveals conserved genes behind complex multicellularity in fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 7409–7418 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Revilla-Guarinos M. T., Martin-Garcia R., Villar-Tajadura M. A., Estravis M., Coll P. M., Perez P., Rga6 is a fission yeast rho gap involved in cdc42 regulation of polarized growth. Mol. Biol. Cell 27, 1524–1535 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nieuwenhuis B. P., James T. Y., The frequency of sex in fungi. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 371, 20150540 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nedelcu A. M., Michod R. E., Stress Responses Co-Opted for Specialized Cell Types During the Early Evolution of Multicellularity. Bioessays 42, 2000029 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Love A., Wagner G. P., Co-option of stress mechanisms in the origin of evolutionary novelties. Evolution 76, 394–413 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Qian W., Ma D., Xiao C., Wang Z., Zhang J., The genomic landscape and evolutionary resolution of antagonistic pleiotropy in yeast. Cell Rep. 2, 1399–1410 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang Z., Zhang J., Impact of gene expression noise on organismal fitness and the efficacy of natural selection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, E67–E76 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cooper K. F., Mallory M. J., Egeland D. B., Jarnik M., Strich R., Ama1p is a meiosis-specific regulator of the anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 14548–14553 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Havird J. C., Forsythe E. S., Williams A. M., Werren J. H., Dowling D. K., Sloan D. B., Selfish Mitonuclear Conflict. Curr. Biol. 29, R496–R511 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ghiselli F., Milani L., Linking the mitochondrial genotype to phenotype: A complex endeavour. Philos T R Soc B 375, 20190169 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Small I., Melonek J., Bohne A. V., Nickelsen J., Schmitz-Linneweber C., Plant organellar RNA maturation. Plant Cell 35, 1727–1751 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang C., Zhang S., Hou R., Zhao Z., Zheng Q., Xu Q., Zheng D., Wang G., Liu H., Gao X., Ma J. W., Kistler H. C., Kang Z., Xu J. R., Functional analysis of the kinome of the wheat scab fungus Fusarium graminearum. PLOS Pathog. 7, e1002460 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cavinder B., Sikhakolli U., Fellows K. M., Trail F., Sexual development and ascospore discharge in Fusarium graminearum. J. Vis. Exp., 3895 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Catlett N. L., Lee B.-N., Yoder O., Turgeon B. G., Split-marker recombination for efficient targeted deletion of fungal genes. Fungal Genetics Newsletter 50, 9–11 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pertea M., Kim D., Pertea G. M., Leek J. T., Salzberg S. L., Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat. Protoc. 11, 1650–1667 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Okonechnikov K., Conesa A., Garcia-Alcalde F., Qualimap 2: Advanced multi-sample quality control for high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 32, 292–294 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu H., Xu J. R., Discovering RNA Editing Events in Fungi. Methods Mol. Biol. 2181, 35–50 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liao Y., Smyth G. K., Shi W., featureCounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923–930 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dimont E., Shi J., Kirchner R., Hide W., edgeRun: An R package for sensitive, functionally relevant differential expression discovery using an unconditional exact test. Bioinformatics 31, 2589–2590 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen C., Chen H., Zhang Y., Thomas H. R., Frank M. H., He Y., Xia R., TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 13, 1194–1202 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]