Abstract

Background and Purpose:

Aerobic exercise can elicit positive effects on neuroplasticity and cognitive executive function but is poorly understood after stroke. We tested the effect of 4 weeks of aerobic exercise training on inhibitory and facilitatory elements of cognitive executive function and electroencephalography (EEG) markers of cortical inhibition and facilitation. We investigated relationships between stimulus-evoked cortical responses, blood lactate levels during training, and aerobic fitness post-intervention.

Methods:

Twelve individuals with chronic (>6mo) stroke completed an aerobic exercise intervention (40-mins, 3x/week). Electroencephalography and motor response times were assessed during congruent (response facilitation) and incongruent (response inhibition) stimuli of a Flanker task. Aerobic fitness capacity was assessed as VO2-peak during a treadmill test pre- and post-intervention. Blood lactate was assessed acutely (<1 min) after exercise each week. Cortical inhibition (N2) and facilitation (frontal P3) were quantified as peak amplitudes and latencies of stimulus evoked EEG activity over the frontal cortical region.

Results:

Following exercise training, the response inhibition speed increased while response facilitation remained unchanged. A relationship between earlier cortical N2 response and faster response inhibition emerged post-intervention. Individuals who produced higher lactate during exercise training achieved faster response inhibition and tended to show earlier cortical N2 responses post-intervention. There were no associations between VO2-peak and metrics of behavioral or neurophysiologic function.

Discussion and Conclusions:

These preliminary findings provide novel evidence for selective benefits of aerobic exercise on inhibitory control during the initial 4-week period after initiation of exercise training, and implicate a potential therapeutic effect of lactate on post-stroke inhibitory control.

Keywords: lactate, response inhibition, vigorous exercise, event-related potential, electroencephalography, executive function

Introduction

Aerobic exercise training has the capacity to elicit positive effects on brain function and behavior, but is poorly understood after stroke. In particular, emerging research on the effects of vigorous intensity aerobic exercise to promote neuroplasticity and neurorecovery processes has generated recent interest in the field of stroke recovery.1–6 Aerobic exercise training can be an effective approach to increase the speed and accuracy of cognitive executive function processes,7,8 one of the most common dysfunctional behavioral manifestations after stroke.9,10 Among several domains of cognitive executive function, aerobic exercise appears to preferentially benefit response inhibitory control that engages inhibitory cortical networks.11–14 For example, young adults demonstrated shorter latencies of EEG markers of cortical inhibitory processing after an aerobic exercise intervention, while markers of cortical facilitatory processing remained unchanged.15 Similarly, Chut et al.12 observed selective improvements in cortical inhibitory processes after aerobic exercise training in young adults, while studies in older adults observed improvements in cognitive tasks requiring inhibitory processes after exercise.16,17 This inhibitory effect of aerobic exercise is of particular interest in people after stroke who demonstrate impaired cortical and behavioral inhibitory function18–21 linked to cognitive and motor dysfunction.18–21 Given the well-established benefits of aerobic exercise for cardiovascular health, the effect of exercise training on persistent behavioral deficits and the dysfunctional cortical neurophysiology underlying these deficits after stroke remains elusive.

Electroencephalographic (EEG) signatures of cortical activity provide a biomarker for post-stroke recovery20–22 and identify neural substrates to target with rehabilitation efforts.23 Well-characterized components of the evoked cortical activity time-locked to behavioral task performance provide insight into distinct features of cortical facilitatory and inhibitory processes.24–30 Improvements in EEG markers of cortical inhibitory processing and behavioral response inhibition performance have been observed with aerobic exercise training in young, neurotypical adults.12,31,32 Such effects are also observed acutely after exercise in chronic stroke.7 Yet, the chronic effect of habitual aerobic exercise training on cortical function and associated cognitive behavior have not been investigated in people post-stroke.

The intensity level of exercise training has generated recent interest across the clinical research community as an approach to optimize neuroplasticity and functional recovery after stroke.3,33,34 High blood lactate levels, achieved with more vigorous exercise training intensities, can cross the blood brain barrier to positively influence neural function35,36 and have been posited as a key mechanism for exercise-induced improvements in cortical function.4,35,37 Sufficiently high blood lactate accumulation with aerobic exercise may also enhance the capacity for neuroplasticity by increasing circulating levels of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF).3,38,39 Vigorous-intensity exercise training that produces higher lactate levels may also show greater effectiveness compared to moderate-intensity exercise for improving physical mobility and fitness after stroke,34,40,41 which is consistently linked to higher cognitive function 42–44 and biomarkers of brain health.45 Yet, the relationships between exercise-induced increases in blood lactate, aerobic fitness, and cortical function are unclear, creating a barrier to clinical translation, where aerobic exercise is not typically used as part of an intervention strategy to promote neuroplasticity for post-stroke recovery.46

In the present study, we provide an initial investigation of the effects of a 4-week aerobic exercise intervention on behavioral and neurophysiologic metrics of cortical function in individuals with chronic stroke. We probe the effects of aerobic fitness and exercise-induced lactate on post-stroke behavioral and neurophysiologic cortical function. We hypothesized that 1) aerobic exercise would elicit greater improvements in post-stroke executive function involving inhibitory compared to facilitatory control, with inhibitory control showing a positive association with efficiency of EEG markers of cortical inhibitory processing post-intervention, and 2) higher lactate produced during exercise and greater aerobic fitness capacity post-intervention would be associated with faster and more robust EEG and behavioral markers of inhibitory control. .

Methods

This study is ancillary to a primary multi-site randomized control trial (RCT) (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03760016).34 A detailed trial protocol has been described in Miller et al. (2021)47 and primary endpoint analyses for the full participant cohort are described in Boyne et al., 2022.34 Briefly, participants (40–80 years old) sustained a single stroke 6mo-5yrs prior to consent, could walk at least 10 meters without the assistance of another person (use of assistive device was permitted), had a walking speed of 1.0m/s or slower, had the ability to walk on a treadmill at a minimum of 0.13m/s (0.3 mph), and were of stable cardiovascular condition.34 Participants were excluded if they were currently participating in physical therapy or another interventional study, or if they had previous exposure to fast treadmill walking in the past year. The experimental protocols for the primary and ancillary study protocols were approved by the University of Kansas Medical Center Institutional Review Board and all participants provided written, informed consent (UC IRB 2017–5325; KUMC IRB MOD00023271; STUDY00143669).

Participants

A subgroup of 16 eligible participants from the University of Kansas Medical Center participated in the present ancillary study. Given the preliminary nature of this work, our sample size included all eligible and interested participants who entered the parent RCT34 at the present site. Based on acute effects of aerobic exercise on EEG markers of cognitive function reported in chronic stroke by Swatridge et al (2017)7 (n=9), we predicted that recruiting a sample size of 16 participants in would be adequately powered to detect changes in EEG and behavioral markers of cortical function with an aerobic exercise intervention. In addition to clinical and aerobic fitness assessments associated with the primary study, these participants were asked to complete cognitive assessments with concurrent EEG at baseline and 2–7 days after the final exercise training session within the 4-week intervention.

Exercise intervention

The exercise intervention methods are thoroughly detailed in the protocol and primary outcomes papers for the present study.34,47 Briefly, following baseline assessments participants were randomized to exercise training consisting of either high-intensity interval or moderate-intensity continuous walking exercise intervention arms. The aim of this ancillary study was to investigate behavioral and neurophysiologic metrics of cortical function with exercise training, thus participants from both intensity groups were pooled together, as performed previously.48 All participants in each arm completed 40-minutes total of mixed over-ground (two 10-minute bouts) and treadmill (one 20-minute bout) walking under the treatment of a licensed physical therapist, which was either continuous and targeting ~45% of the training HR zone in the moderate-intensity aerobic exercise group or bursts of 30s of walking at the individual’s maximum achievable speed separated by ~30–60s of resting in the high-intensity interval group, 3x/week for 12 treatment sessions.34,47 The target training HR zone was determined using the HRR method: (peak HR – resting HR) x percent HRR target + resting HR,49 where peak HR was the highest HR achieved during the baseline GXT and the resting HR was the HR during quiet standing on the current training day. After 4 weeks of training (12 sessions) post-intervention assessments were performed within 2–7 days by the same blinded experimenter.

Cardiovascular fitness and clinical walking assessment

Participants completed a treadmill graded exercise test (GXT) where oxygen consumption (VO2) was continuously measured.34 Aerobic fitness was quantified as the peak VO2 achieved during the treadmill GXT assessment using a metabolic cart (TrueOne 2400, ParvoMedics, Salt Lake City, UT, USA) with a facemask interface. The GXT was performed by an exercise physiologist and physical therapist who were blinded to group assignment. Participants started the test walking at 0.3 mph at 0% grade for the first 3 minutes. The speed was increased by 0.1 mph every 30 seconds until 3.5 mph was reached, after which the incline was increased by 0.5% every 30 seconds. The test stopped when the participant requested to stop, drifted backward without recovery on the treadmill, displayed severe gait instability, or reached a cardiovascular safety limit.34 Participants rested for a minimum of 10 minutes and then attempted a 3-minute verification test without respiratory gas collection to help ensure that the highest possible HR was reached on the GXT. The GXT VO2 data were smoothed with a 20-second rolling average and calculated from 5 second averaged data. Self-selected and maximal walking speed also were assessed using the 10-meter walk. Functional walking capacity, the primary outcome of the parent study,34 was assessed using a 6-minute walk test. Assessments were performed at baseline and post-intervention after 4 weeks of exercise training.

Blood lactate and heart rate measures of exercise intensity

Blood lactate concentration was rapidly assessed (<1 minute) after treadmill exercise cessation using a finger stick method and a point-of-care blood lactate analyzer (Lactate Plus, Nova Biomedical, Waltham, MA, USA) at the mid-week training session each week. The mean blood lactate during exercise training over the 4 weeks for each individual was used for analyses. Heart rate (HR) was continuously recorded using Bluetooth HR monitors and the iPod touch iCardio application during each exercise bouts for each training session. Mean steady-state HR (excluding the first 3 minutes) and peak HR for each training session was determined as % heart rate reserve (HRR) relative to the current session’s standing resting HR and the most current peak HR obtained during the GXT (Table 1).34

Table 1.

Participant clinical and fitness outcomes in response to the intervention as Mean (SD).

| Intervention Arm | VO2-peak (ml/kg/min) | 6MWT (meters) | Fastest 10MWT speed (meters/sec) | Blood Lactate (mmol/L) | Mean steady-state HR (%HRR) | Peak HR (%HRR) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Participant ID | Baseline | Post | Baseline | Post | Baseline | Post | Average | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| S01 | HIIT | 18.6 | 17.4 | 400 | 271.5 | 1.47 | 2.03 | 1.43 | 53.0 | 74.7 |

| S02 | MAT | 14.5 | 13.9 | 350.0 | 399.1 | 1.20 | 1.32 | 2.23 | 45.7 | 71.5 |

| S03 | MAT | 8.8 | 10.1 | 186.9 | 224 | 0.69 | 0.73 | 1.53 | 49.5 | 70.7 |

| S04 | HIIT | 15.7 | 14.5 | 309.5 | 331.0 | 1.08 | 1.14 | 2.35 | 43.0 | 79.2 |

| S05 | HIIT | 19.8 | 20.9 | 450.0 | 556.5 | 1.51 | 2.04 | 5.55 | 51.7 | 68.5 |

| S06 | MAT | 13.3 | 15.0 | 168.8 | 152 | 0.99 | 0.81 | 4.45 | 40.9 | 56.9 |

| S07 | HIIT | 16.7 | 21.1 | 352.0 | 424.5 | 1.40 | 1.85 | 2.00 | 65.3 | 83.8 |

| S08 | MAT | 9.0 | 9.6 | 98.8 | 88.0 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 1.25 | 38.9 | 68.0 |

| S09 | MAT | 17.0 | 17.3 | 250.0 | 288.1 | 0.86 | 0.72 | 2.65 | 51.8 | 66.5 |

| S10 | MAT | 21.6 | 24.1 | 314.1 | 421.5 | 1.16 | 1.37 | 2.95 | 52.9 | 67.6 |

| S11 | HIIT | 16.2 | 15.8 | 259.8 | 400.0 | 0.94 | 1.41 | 1.50 | 72.2 | 104.4 |

| S12 | MAT | 16.6 | 15.0 | 180.2 | 178.4 | 0.65 | 0.66 | 1.20 | 53.1 | 67.7 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | MAT=7 | 15.7 (3.8) | 16.2 (4.3) | 276.7 (104.6) | 311.2 (136.1) | 1.02 (0.36) | 1.20 (0.57) | 2.42 (1.35) | 51.5 (9.6) | 73.3 (11.9) |

Abbreviations: MAT, Moderate-intensity aerobic training; HIIT, High-intensity interval training; VO2-peak, Peak oxygen consumption; 6MWT, Six-Minute Walk Test; 10MWT, Ten-Meter Walk Test; GS, Gait Speed; Mean Steady-state heart rate (HR) as a % of heart rate reserve (HRR) calculated relative to standing HR at rest and most current HR peak.

Eriksen Flanker task

Participants completed a modified arrow Eriksen Flanker task,50 during which cognitive executive function behavior and concurrent EEG recordings of response facilitation and inhibition were measured. Participants were seated comfortably in a chair with both hands resting on a table in front of them and a computer mouse control positioned under the index and middle fingers of the nonparetic hand. Participants were instructed to press the left or right mouse button corresponding to the direction of the central arrowhead on a visual monitor display as quickly and accurately as possible. There were two “congruent” stimuli (“<<<<<” and “>>>>>”) and two “incongruent” stimuli (“<<><<” and “>><>>”) presented for 200ms, jittered randomly between 3000 to 3200ms. Following a 12-trial practice block, 200 stimuli were presented randomly, with 50 trials for each left/right directions and congruent/incongruent conditions (total 200 trials).

Behavioral performance during the Flanker task

Accuracy and response time were assessed separately for congruent and incongruent stimuli. Accuracy was quantified as the percentage of correct responses out of total responses. Response latencies were assessed in the congruent condition, in which participants facilitated a rapid response clearly indicated by the stimulus, and in the incongruent condition, in which participants needed to rapidly inhibit the prepotent, incorrect response that is activated by the conflicting stimulus information. Trials with incorrect responses, indicating failure to inhibit the incorrect prepotent responses, were excluded from measurement of response latencies.7 Response latencies were quantified as the mean time between visual stimulus onset and accurate motor response across all correct trials for each condition. The response time cost of inhibiting the prepotent incorrect response to the incongruent stimulus (response inhibition) was quantified within individuals as the relative increase in response time latency during the incongruent condition as: response time (incongruent)/response time (congruent).

Electroencephalography (EEG) data collection and analyses

During the Flanker task, EEG recordings of cortical activity were acquired using 256-channel HydroCel Geodesic Sensor Net (Electrical Geodesics, Inc.) (1000 Hz). All data analyses were performed using the EEGlab toolbox51 and custom MATLAB software. Time-locked continuous data were filtered with a high-pass cutoff of 0.1Hz and a low-pass cutoff of 30Hz. Next, correct trials were epoched (−1 to 2s) relative to visual stimulus onset at t=0, and re-referenced to the average of bilateral mastoid electrodes. Eye movement and blink artifacts were identified and corrected using the automatic method (Gratton, Coles, and Donchin).52 Trials with other artifacts were automatically detected and rejected if the range or variance of the voltage within a trial was > 2 standard deviations above the average within individual and channel. The data were then averaged across all trials within each condition and the average voltage between 100–400ms before stimulus onset was subtracted. Cortical inhibitory and facilitatory processing were quantified as the latencies and amplitudes of the peak evoked cortical negative N224 (200–300ms, incongruent trials) and positive P37,25 (300–1000ms, congruent trials)19 components at the Fz fronto-central channel location.53 For two participants, the N2 time window was shifted to 250–350ms to capture the slower negative peak, consistent with previous reports post-stroke.7 The mean of the peak amplitudes and latencies of the N2 and P3 components across like conditions were measured at baseline and post-intervention.

Statistical analyses

We tested for normality and heterogeneity of variance of all data used for analyses using Shapiro-Wilk and Levene’s tests, respectively. All dependent variables met assumptions of normality and heterogeneity of variance (p>.084) and parametric tests were used. Hypothesis 1: Repeated one-way analysis-of-variance (ANOVA) tests were used to test for a change in behavioral response accuracy and speed as well as cortical response latencies and amplitudes of the N2 and P3 between baseline and post-intervention timepoints. In exploratory analyses, Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients were used to test for associations between inhibitory behavioral response time cost and the N2 response latencies and amplitudes during the incongruent condition, and between behavioral response times and P3 response latencies and amplitudes during the congruent condition at baseline and at the 4-week post-intervention timepoint. Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients were also used in exploratory analyses to test the relationship between blood lactate during exercise training and peak-VO2 versus behavioral (response time, inhibitory response time cost) and cortical activity components (N2, P3) post-intervention. To further probe whether any detectable effects of blood lactate were dissociable from exercise intensity, we also tested relationships between exercise mean steady-state HR and peak HR on behavioral and cortical metrics that emerged in relation to lactate. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 27 with an a priori level of significance set to 0.05.

Results

Of the total 16 participants who enrolled, two participants withdrew from the primary RCT within the first 4 weeks and did not complete the intervention. (Figure 1). Incomplete datasets were excluded from the present analyses. Two additional participants were unavailable for cognitive/neurophysiologic testing at the 4-week post-intervention assessment. Participants attended 141 (98%) of the planned 144 sessions, initiated 422 (~100%) of 423 planned overground and treadmill bouts, and performed 5,625 (~100%) of 5,640 planned training minutes, including intermittent rest breaks. Complete datasets were available for twelve participants (age 61±11yrs, range 47–77yrs, male =8, post-stroke duration 26.7±17.1 months, ischemic stroke =7, left side lesion = 5) who completed 4 weeks of exercise training and all baseline and post-intervention assessments (Figure 1). No serious study-related adverse events occurred during this ancillary study.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram for the present ancillary study to parent study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03760016). MAT: Moderate-intensity aerobic training; HIIT: high-intensity interval training; AE: adverse event

Aerobic fitness and clinical walking response to exercise intervention

Reporting of primary and secondary clinical outcomes for the full participant cohort are detailed in Boyne et al (2022).34 The subset of participants in the present ancillary study produced a mean blood lactate level of 2.42±1.35 mmol/L [Range: 1.20–5.55 mmol/L], achieved a steady-state HR of 52±10%HRR [Range: 39–72%HRR] and a peak HR of 73±12 %HRR [Range: 57–104%HRR] during the first 4-week block of exercise training. Comfortable and maximal walking speed increased 4 weeks post-intervention (self-selected: baseline0.75±0.26 m/s, post 0.80±0.27 m/s, p=0.037; fastest: baseline 1.02±0.36 m/s, post 1.20±0.57 m/s, p=0.041). Functional walking capacity on the 6-minute walk test (baseline 276.7±104.6 m, post 311.2±136.1 m, p=0.122) and aerobic fitness capacity, measured as VO2-peak during the GXT baseline 15.7±3.9 mL/kg/min, post 16.2±4.3 mL/kg/min, p=0.288), showed no change after 4 weeks post-intervention (Table 1).

Effect of aerobic exercise training on cognitive behavior and cortical processing

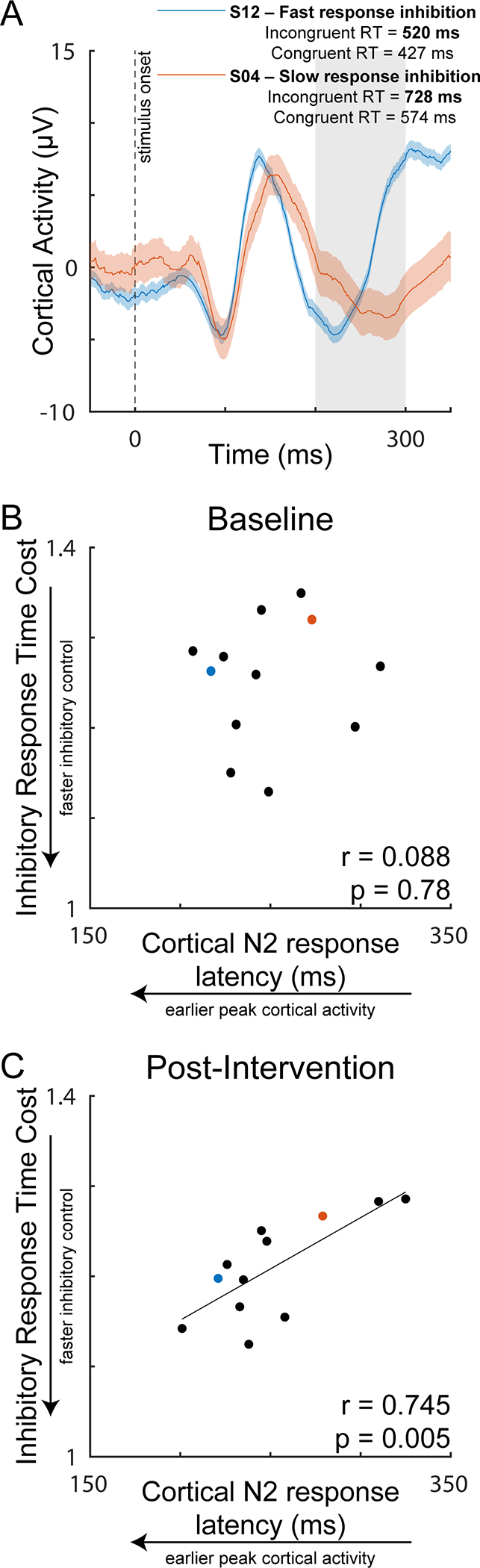

Participants achieved a lower response time cost of inhibiting prepotent responses during incongruent stimuli (response inhibition) post-intervention (Figure 2A, p= 0.037), with no significant change in accuracy (Figure 2B, p= 0.088). Response times and accuracy during congruent stimuli (response facilitation) did not change from baseline to post-intervention (response time, p=0.288; accuracy, p=0.389). Although no group-level changes in cortical N2 or P3 responses were observed from baseline to post-intervention (N2 latency, p=0.193; N2 amplitude, p=0.344 (Figure 2C&D) (P3 latency, p= 0.497; P3 amplitude, p=0.105), a positive association between the N2 latency and inhibitory response time cost emerged post-intervention (Figure 3A&C, r=0.745, p=0.005) that was not present at baseline (Figure 3B, r=0.088, p=0.780). There were no associations between amplitude of the N2 peak during the incongruent condition, or the amplitude or latency of the P3 peak during the congruent condition and concurrent behavioral response times at any time point.

Figure 2.

Behavioral and cortical activity markers of inhibitory control during the incongruent stimuli condition at baseline and post-intervention (POST). . Behavioral inhibitory response time cost decreased (*p=.037) across the group (A) while response accuracy showed no significant change (∞ p=.088) (B) post-intervention. The cortical N2 response peak latency (C) and amplitude (D) showed no group-level change post-intervention.

Figure 3.

Cortical N2 response as a function of inhibitory response time cost during the incongruent stimuli condition post-intervention. Representative individuals with slow and fast response inhibition following 4 weeks of exercise training (A). While no relationship was present at baseline (B), a positive relationship between cortical N2 response latency and inhibitory response time cost (reaction time of incongruent/congruent condition) emerged post-intervention, in which individuals with earlier peak cortical N2 responses had faster inhibitory control (C). The dashed line represents the time of visual stimulus onset (t=0). The shaded region represents the time window used for detection of the peak N2 response. RT = response time.

Relationships between blood lactate, cognitive behavior, and cortical processing

Individuals who produced higher blood lactate levels during exercise training had lower inhibitory response time costs post-intervention (Figure 4A&B, r=−0.685, p=0.014). Similarly, we observed a pattern in which individuals with higher blood lactate had earlier cortical N2 response latencies during the incongruent condition post-intervention, though this association failed to meet our adopted level of significance (Figure 4C, r=−0.480, p=0.110). There were no associations between lactate and congruent response time (r=0.463, p=0.130) or P3 response latency (r=0.022, p=0.945) or amplitude (r=0.357, p=0.255). When investigating whether HR measures of exercise intensity showed similar effect to exercise lactate, we found no associations between steady-state HR mean and inhibitory response time cost (r=0.04, p=0.908) or N2 peak latency (r=0.463, p=0.758) or peak HR mean and inhibitory response time cost (r=0.29, p=0.352) or N2 peak latency (r=0.077, p=0.811) post-intervention.

Figure 4.

Cortical N2 response post-intervention as a function of blood lactate produced during exercise training over the course of the 4-week intervention. Representative cortical responses in individuals with higher and lower exercise blood lactate levels (A). There was a negative relationship between blood lactate and inhibitory response time cost (reaction time of incongruent/congruent condition), in which individuals who produced greater exercise lactate achieved faster inhibitory control performance (B). Individuals who produced greater exercise lactate also showed a pattern of earlier peak cortical N2 activity post-intervention, but this effect failed to meet our adopted level of significance (C).

Relationship between aerobic fitness capacity on cognitive behavior and cortical processing

We observed no associations between VO2-peak and any domain of executive function performance (congruent response time, p=0.788; inhibitory response time cost, p=0.392) or latency or amplitude of the cortical N2 (latency, p=0.245; amplitude, p=0.177) or P3 (latency, p=0.418; amplitude, p=0.745) post-intervention.

Discussion

Findings of the present study provide initial evidence that aerobic exercise training may preferentially benefit post-stroke response inhibition behavior and strengthen neurophysiologic brain-behavior relationships in chronic stroke. Our preliminary results show that individuals who produced higher blood lactate during exercise training had faster response inhibition post-intervention, supporting further mechanistic investigation of lactate as a mediator for inhibitory cortical plasticity in individuals post-stroke. These effects occurred after only 4 weeks of exercise training and were independent of aerobic fitness capacity, suggesting that neuromotor rather than cardiovascular changes with aerobic exercise training drive improvements in post-stroke inhibitory control.

Aerobic exercise training selectively improves response inhibition after stroke

Our results reveal measurable improvements in post-stroke executive function after aerobic exercise training, an effect specific to behavior involving inhibitory control. We found a reduction in the response time cost of inhibiting the prepotent incorrect response to incongruent stimuli post-intervention (Figure 2A), without changes in general response facilitation. Interestingly, this selective effect on inhibition was not reported acutely after a single bout of aerobic exercise in stroke, in which both cortical facilitatory and inhibitory processes were modulated.3,7 Thus, the present findings build upon previous studies of acute, exercise-induced neuroplasticity post-stroke, suggesting a shift from a generalized to a more specific effect on inhibition over time with repeated exposure to aerobic exercise training. Neurotypical young 11,12,15 and older adults16,54,55 also show selective effect of aerobic exercise interventions on cognitive inhibitory control. Notably, exercise effects on behavioral inhibitory control can occur in the absence of a group-level changes in the latency or amplitude of the cortical N2 response in neurologically-intact individuals,12 consistent with the present findings. These findings support the notion that facilitatory and inhibitory elements of cognitive executive function differentially respond to aerobic exercise training.

The relationship between neurophysiologic markers of cortical processing and response inhibition behavior were strengthened after exercise training, illuminating potential mechanisms underpinning improved inhibitory control with exercise after stroke. While no relationship was present at baseline (Figure 3B), we found a positive relationship between cortical and behavioral indices of inhibitory function after 4 weeks of aerobic exercise training (Figure 3B). Specifically, individuals with earlier cortical N2 response latencies post-intervention also achieved lower inhibitory response time costs (Figure 3A), suggesting a strengthened link between cortical processing and resulting behavioral aspects of response inhibition. The emergence of this brain-behavior correlate with aerobic exercise training offers a mechanistic explanation for the improved cost of response inhibition post-intervention (Figure 2A). The strength of neurophysiologic brain-behavior relationships is behaviorally relevant in the context of aging and neuropathology, where there is a weakened association between EEG markers of cortical activity and concurrent behavior.56–58 The association between cortical activity and response inhibition behavior can be improved with intervention, and appears to reflect reallocation or strengthening of cortical resources to inhibitory control processes involving frontal-motor regions to detect and inhibit response conflict.56,59,60 Aerobic exercise training may trigger a similar shift in the neural strategy that individuals post-stroke utilize for inhibitory control, increasing the proficiency of frontal-motor cortical inhibitory processes and improving cortical reactivity mechanisms commonly impaired after stroke.20,21 Given the absence of group-level changes in cortical N2 responses (Figure2C&D), it is possible that other neural signals interfering with the role of cortical inhibition in mediating cognitive control were dampened with aerobic exercise training, for example by improvements in neural dedifferentiation across multiple cortical regions observed in aging populations.61 Higher levels of physical activity have been linked to greater myelination within the post-stroke brain62 and can occur on timescales of 2–6 weeks (for review see Bloom et al (2022),63 consistent with the temporal cortical N2 component (i.e. N2 latency) association with behavior following exercise training in the present study (Figure 3C). Future studies employing multimodal neuroimaging approaches (e.g., functional magnetic resonance imaging– EEG) could provide spatial insight into the neural substrates underpinning behaviorally-salient markers of cortical inhibition and may inform the development of targeted synergistic treatment approaches (e.g. noninvasive brain stimulation)64 with aerobic exercise training.

Lactate may play a role in aerobic exercise effects on post-stroke inhibitory control

Our findings show preliminary evidence that lactate may play a role in exercise-induced improvements in inhibitory control after stroke. In the present study, individuals who produced a higher lactate during exercise training had lower inhibitory response time cost and tended to evoke earlier cortical N2 responses post-intervention (Figure 4). Notably, only two individuals reached a mean exercise lactate level of >4.0 mmol/L, the typical threshold for transition from aerobic to more anaerobic metabolism;65 these individuals strongly influenced the effect on lactate on behavioral and neurophysiologic markers of inhibitory control (Figure 4B&C). Thus, the interpretation of this association is limited by the small sample size of the present study and relatively low exercise lactate levels of the majority of the participant cohort. However, these findings provide preliminary evidence to support a threshold for eliciting therapeutic effects on post-stroke neuroplasticity for inhibitory control. These preliminary findings may motivate future aerobic exercise studies in stroke populations to assess blood lactate and help elucidate its role in exercise-induced changes in neurocognition. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA),which primarily mediates cortical inhibition,5,6 is preferentially activated by the peripheral release of lactate during exercise that crosses the blood brain barrier.5,6 While the causal link in the association between exercise lactate and post-stroke inhibitory control cannot be determined in the present study, there is evidence to support that lactate may be used to synthesize GABA and glutamate, increasing the concentration and bioavailability of these neurotransmitters immediately post-exercise.5,66–68 The ability to augment GABAergic plasticity is of particular interest after stroke, where GABA modulation was associated with improved motor function following rehabilitation.69 Future studies may test whether lactate may facilitate GABAergic neuroplasticity that could be leveraged to target specific neural deficits in post-stroke neurorehabilitation.

In neurotypical individuals, vigorous-intensity exercise specifically primes neuroplasticity involving inhibitory control4,70–72 and heightens GABA neuro-availability.5,6 This targeted GABAergic effect of vigorous intensity exercise may explain the present selective effects of exercise on post-stroke inhibitory control (Figures 2 & 4), and raises the possibility that interventions aimed at producing sufficiently high lactate levels (e.g.,>4.0mmol/L) could magnify this effect. Notably, the two individuals in the present study to reach the highest blood lactate during exercise (S05 and S06, Table 1) each underwent different treatment arms involving moderate-intensity continuous aerobic training (S06) and high-intensity interval training (S05) and exercised at HRs that were similar or lower than the group mean (steady-state group mean 52%HRR, (S05 mean HR = 52%HRR, S06 mean HR = 41% HRR) (peak group mean 73%HRR, (S05 peak HR = 69%HRR, S06 peak HR = 57% HRR) (Table 1). In contrast to the effect observed with exercise blood lactate, there were no associations between steady-state or peak HRs that individuals averaged over the 12 exercise training sessions and behavioral inhibitory response time cost or cortical N2 response latency. These results provide preliminary evidence for a dissociable effect of blood lactate and HR responses as indicators of exercise intensity on inhibitory function in individuals post-stroke, and warrant investigation by future studies. Further, these preliminary data suggest that post-stroke interventions can utilize a range of approaches (e.g. moderate-intensity continuous and high-intensity interval exercise) to achieve lactate levels sufficient to provide therapeutic effects on inhibitory control. While the pattern between higher lactate and earlier cortical N2 response did not reach statistical significance (Figure 4C), future studies investigating more specific indices of GABAergic network activity (e.g., beta power)19 and connectivity (e.g., beta coherence)20 may be better positioned to detect such associations. These preliminary findings provide an exciting first-step for future investigation of effects of exercise dosing and the production of peripheral metabolites on post-stroke cortical plasticity and inhibitory control.

Initial effects of aerobic exercise on response inhibition behavior are not associated with aerobic fitness changes post-stroke

The present findings reveal that improvements in inhibitory control occur after only 4 weeks of habitual aerobic exercise and in the absence of aerobic fitness changes in individuals with chronic stroke (Figure 2). These initial post-stroke behavioral changes and associated markers of cortical inhibition (Figure 3) appear to be independent of exercise-induced changes in aerobic fitness capacity, as there were no relationships between VO2-peak and cortical or behavioral metrics and no detectible group-level increase in VO2-peak post-intervention. This was an unexpected finding given the well-established link between physical fitness and cognitive function.45 While the small sample size and short assessment timeframe may have been underpowered and insufficient to detect changes in VO2-peak, the observed relationships with blood lactate suggest that inhibitory control can improve with exposure to sufficient production of blood lactate during the initial period of exercise training before overall changes in aerobic fitness are achieved. Our findings show that early improvements in executive inhibitory control induced by exercise training occur on a similar timescale to significant increases in short-distance gait speed (Table 1), that appear to be driven by neuromotor rather than cardiopulmonary adaptations.34 Our results imply that individuals across a spectrum of aerobic fitness levels after stroke may achieve early neuromotor benefits from aerobic exercise training for speed-dependent domains of specific aspects of cognitive function and ambulatory capacity.

Limitations

This study leveraged a multisite, RCT involving aerobic exercise training34 to provide novel, mechanistic insight into the effects of aerobic exercise on cortical processing and associated cognitive behavior. The exercise training employed by the present study was more intensive than that of conventional post-stroke rehabilitation and did not include skilled motor practice, which positioned us well to investigate aerobic exercise-induced effects on neurophysiologic and behavioral indices of cortical function. Our analyses utilized a pointed, hypotheses-driven approach that was motivated by our previous work and specific interest in post-stroke cortical inhibitory processing and response inhibition behavior and effects of exercise and training intensity.

The greatest limitations of this study involve the small sample size and a lack of control condition (i.e. non-exercise) or long-term follow-up. Thus, results should be interpreted cautiously and warrant a larger RCT to confirm and expand these findings. Given the preliminary nature of this study, our analyses utilized a pointed, hypotheses-driven approach that was motivated by our previous work and specific interest in post-stroke cortical inhibitory function and effects of exercise and training intensity. Thus, it is possible that we were not adequately powered to detect exercise-induced changes in cortical responses with smaller effect sizes. This small-scale ancillary study lacked a control condition (i.e. non-exercise), limiting interpretation for the causality of the exercise intervention on the results. No long-term follow-up testing occurred to determine whether improved inhibitory response time cost was further enhanced with additional training as part of the primary study RCT (e.g. 8-weeks, 12-weeks of training)34 or whether there were sustained effects after completing the intervention. Thus, results should be interpreted cautiously and a larger RCT with controls, additional assessments, and follow-up retention testing would be needed to confirm and expand these findings. Larger sample sizes would also provide the opportunity to test the effect of habitual aerobic exercise across a more expansive battery of cognitive domains and sophisticated analyses of cortical function (e.g., spectral and component features of EEG activity). There is always a potential that learning effects on cognitive assessments such as the Flanker task that could contribute to improvements in performance over time. In the present study we aimed to minimize learning effects from this cognitive test by 1) the long time duration (>4 weeks between baseline and post-intervention) between assessments, 2) providing a short practice test prior to each assessment at baseline and post-intervention, and 3) normalizing response inhibition performance to response facilitation performance, which would expectedly show a similar magnitude of learning effect. Additionally, the association between exercise lactate and response inhibition performance post-intervention provides preliminary support that the effect of improvements in inhibitory control may be mediated by physiologic mechanisms elicited by the aerobic exercise intervention and are not fully explained by learning effects of the task.

Conclusions

The present study provides preliminary evidence for initial and selective improvements in inhibitory control following 4 weeks of intensive aerobic exercise training in people with chronic stroke. Our results provide a basis for future studies to investigate effects of exercise metabolites such as lactate on post-stroke inhibitory control and associated inhibitory cortical plasticity. Our findings support a multimodal approach that synergizes aerobic exercise and skilled practice targeting complementary cortical inhibitory mechanisms to maximize post-stroke treatment outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development and the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health [NIH K99AG075255 (JP), R01HD093694 (PB, DR, SB), P30 AG072973 (JP, SB), P30AG035982 (JP, SB), UL1TR000001, F32MH129076 (AP), T32HD057850 (AW)], the American Heart Association [898190 (AW)], and the Georgia Holland Endowment Fund. The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or any other funding agency.

We would like to acknowledge Doctor of Physical Therapy students Preston Judd, Katelyn Struckle, and Kailee Carter for their assistance in delivery of the exercise intervention and data analyses.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Crozier J, Roig M, Eng JJ, et al. High-Intensity Interval Training After Stroke: An Opportunity to Promote Functional Recovery, Cardiovascular Health, and Neuroplasticity. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2018;32(6–7):543–556. doi: 10.1177/1545968318766663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hugues N, Pin-Barre C, Pellegrino C, Rivera C, Berton E, Laurin J. Time-Dependent Cortical Plasticity during Moderate-Intensity Continuous Training Versus High-Intensity Interval Training in Rats. Cereb Cortex. Published online January 14, 2022:bhab451. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhab451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyne P, Meyrose C, Westover J, et al. Exercise intensity affects acute neurotrophic and neurophysiological responses poststroke. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2019;126(2):431–443. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00594.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.da Silva WQA, Fontes EB, Forti RM, et al. Affect during incremental exercise: The role of inhibitory cognition, autonomic cardiac function, and cerebral oxygenation. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0186926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maddock RJ, Casazza GA, Fernandez DH, Maddock MI. Acute Modulation of Cortical Glutamate and GABA Content by Physical Activity. J Neurosci. 2016;36(8):2449–2457. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3455-15.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coxon JP, Cash RFH, Hendrikse JJ, et al. GABA concentration in sensorimotor cortex following high-intensity exercise and relationship to lactate levels. J Physiol. 2018;596(4):691–702. doi: 10.1113/JP274660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swatridge K, Regan K, Staines WR, Roy E, Middleton LE. The Acute Effects of Aerobic Exercise on Cognitive Control among People with Chronic Stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;26(12):2742–2748. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2017.06.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang YK, Labban JD, Gapin JI, Etnier JL. The effects of acute exercise on cognitive performance: a meta-analysis. Brain Research. 2012;9(1453):87–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leśniak M, Bak T, Czepiel W, Seniów J, Członkowska A. Frequency and prognostic value of cognitive disorders in stroke patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;26(4):356–363. doi: 10.1159/000162262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Middleton LE, Lam B, Fahmi H, et al. Frequency of domain-specific cognitive impairment in sub-acute and chronic stroke. NeuroRehabilitation. 2014;34(2):305–312. doi: 10.3233/NRE-131030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levin O, Netz Y, Ziv G. Behavioral and Neurophysiological Aspects of Inhibition-The Effects of Acute Cardiovascular Exercise. J Clin Med. 2021;10(2):E282. doi: 10.3390/jcm10020282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chu CH, Alderman BL, Wei GX, Chang YK. Effects of acute aerobic exercise on motor response inhibition: An ERP study using the stop-signal task. Journal of Sport and Health Science. 2015;4(1):73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2014.12.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Netz Y, Abu-Rukun M, Tsuk S, et al. Acute aerobic activity enhances response inhibition for less than 30min. Brain Cogn. 2016;109:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2016.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mooney RA, Coxon JP, Cirillo J, Glenny H, Gant N, Byblow WD. Acute aerobic exercise modulates primary motor cortex inhibition. Exp Brain Res. 2016;234(12):3669–3676. doi: 10.1007/s00221-016-4767-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ozkaya GY, Aydin H, Toraman FN, Kizilay F, Ozdemir O, Cetinkaya V. Effect of strength and endurance training on cognition in older people. J Sports Sci Med. 2005;4(3):300–313. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duchesne C, Lungu O, Nadeau A, et al. Enhancing both motor and cognitive functioning in Parkinson’s disease: Aerobic exercise as a rehabilitative intervention. Brain Cogn. 2015;99:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2015.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lebeau JC, Mason J, Roque N, Tenenbaum G. The Effects of Acute Exercise on Driving and Executive Functions in Healthy Older Adults. Int J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2022;20(1):283–301. doi: 10.1080/1612197x.2020.1849353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gray WA, Palmer JA, Wolf SL, Borich MR. Abnormal EEG Responses to TMS During the Cortical Silent Period Are Associated With Hand Function in Chronic Stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2017;31(7):666–676. doi: 10.1177/1545968317712470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rossiter HE, Boudrias M hélène, Ward NS. Do movement-related beta oscillations change after stroke ? Published online 2014:2053–2058. doi: 10.1152/jn.00345.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmer JA, Wheaton LA, Gray WA, Silva MAS da, Wolf SL, Borich MR. Role of Interhemispheric Cortical Interactions in Poststroke Motor Function: Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair. Published online July 22, 2019. doi: 10.1177/1545968319862552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmer JA, Kesar TM, Wolf SL, Borich MR. Motor Cortical Network Flexibility is Associated With Biomechanical Walking Impairment in Chronic Stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. Published online September 27, 2021:15459683211046272. doi: 10.1177/15459683211046272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cassidy JM, Wodeyar A, Wu J, et al. Low-Frequency Oscillations Are a Biomarker of Injury and Recovery After Stroke. Stroke. 2020;51(5):1442–1450. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.028932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vatinno AA, Simpson A, Ramakrishnan V, Bonilha HS, Bonilha L, Seo NJ. The Prognostic Utility of Electroencephalography in Stroke Recovery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2022;36(4–5):255–268. doi: 10.1177/15459683221078294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pires L, Leitão J, Guerrini C, Simões MR. Event-related brain potentials in the study of inhibition: cognitive control, source localization and age-related modulations. Neuropsychol Rev. 2014;24(4):461–490. doi: 10.1007/s11065-014-9275-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Dinteren R, Arns M, Jongsma MLA, Kessels RPC. P300 development across the lifespan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e87347. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfefferbaum A, Ford JM. ERPs to stimuli requiring response production and inhibition: effects of age, probability and visual noise. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1988;71(1):55–63. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(88)90019-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bertoli S, Probst R. Lack of standard N2 in elderly participants indicates inhibitory processing deficit. Neuroreport. 2005;16(17):1933–1937. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000187630.45633.0a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pavarini SCI, Brigola AG, Luchesi BM, et al. On the use of the P300 as a tool for cognitive processing assessment in healthy aging: A review. Dement Neuropsychol. 2018;12(1):1–11. doi: 10.1590/1980-57642018dn12-010001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng CH, Tsai HY, Cheng HN. The effect of age on N2 and P3 components: A meta-analysis of Go/Nogo tasks. Brain Cogn. 2019;135:103574. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2019.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kok A. Varieties of inhibition: manifestations in cognition, event-related potentials and aging. Acta Psychol (Amst). 1999;101(2–3):129–158. doi: 10.1016/s0001-6918(99)00003-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsieh SS, Huang CJ, Wu CT, Chang YK, Hung TM. Acute Exercise Facilitates the N450 Inhibition Marker and P3 Attention Marker during Stroop Test in Young and Older Adults. J Clin Med. 2018;7(11):E391. doi: 10.3390/jcm7110391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gusatovic J, Gramkow MH, Hasselbalch SG, Frederiksen KS. Effects of aerobic exercise on event-related potentials related to cognitive performance: a systematic review. PeerJ. 2022;10:e13604. doi: 10.7717/peerj.13604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hugues N, Pellegrino C, Rivera C, Berton E, Pin-Barre C, Laurin J. Is High-Intensity Interval Training Suitable to Promote Neuroplasticity and Cognitive Functions after Stroke? Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(6):3003. doi: 10.3390/ijms22063003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boyne P, Billinger SA, Reisman DS, et al. Optimal Intensity and Duration of Walking Rehabilitation in Patients With Chronic Stroke: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. Published online February 23, 2023. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2023.0033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hashimoto T, Tsukamoto H, Ando S, Ogoh S. Effect of Exercise on Brain Health: The Potential Role of Lactate as a Myokine. Metabolites. 2021;11(12):813. doi: 10.3390/metabo11120813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.El Hayek L, Khalifeh M, Zibara V, et al. Lactate Mediates the Effects of Exercise on Learning and Memory through SIRT1-Dependent Activation of Hippocampal Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF). J Neurosci. 2019;39(13):2369–2382. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1661-18.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cai M, Wang H, Song H, et al. Lactate Is Answerable for Brain Function and Treating Brain Diseases: Energy Substrates and Signal Molecule. Front Nutr. 2022;9:800901. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.800901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knaepen K, Goekint M, Heyman EM, Meeusen R. Neuroplasticity — Exercise-Induced Response of Peripheral Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor. Sports Med. 2010;40(9):765–801. doi: 10.2165/11534530-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schiffer T, Schulte S, Sperlich B, Achtzehn S, Fricke H, Strüder HK. Lactate infusion at rest increases BDNF blood concentration in humans. Neuroscience Letters. 2011;488(3):234–237. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.11.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wiener J, McIntyre A, Janssen S, Chow JT, Batey C, Teasell R. Effectiveness of High-Intensity Interval Training for Fitness and Mobility Post Stroke: A Systematic Review. PM R. 2019;11(8):868–878. doi: 10.1002/pmrj.12154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boyne P, Doren S, Scholl V, et al. Preliminary Outcomes of Combined Treadmill and Overground High-Intensity Interval Training in Ambulatory Chronic Stroke. Front Neurol. 2022;13:812875. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.812875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Angevaren M, Aufdemkampe G, Verhaar HJJ, Aleman A, Vanhees L. Physical activity and enhanced fitness to improve cognitive function in older people without known cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(3):CD005381. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005381.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Basso JC, Oberlin DJ, Satyal MK, et al. Examining the Effect of Increased Aerobic Exercise in Moderately Fit Adults on Psychological State and Cognitive Function. Front Hum Neurosci. 2022;16:833149. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2022.833149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kramer AF, Colcombe SJ, McAuley E, Scalf PE, Erickson KI. Fitness, aging and neurocognitive function. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26 Suppl 1:124–127. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang D, Lu Y, Zhao X, Zhang Q, Li L. Aerobic Exercise Attenuates Neurodegeneration and Promotes Functional Recovery – Why It Matters For Neurorehabilitation & Neural Repair. Neurochemistry International. Published online October 6, 2020:104862. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2020.104862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boyne P, Billinger S, MacKay-Lyons M, Barney B, Khoury J, Dunning K. Aerobic Exercise Prescription in Stroke Rehabilitation: A Web-Based Survey of US Physical Therapists. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2017;41(2):119–128. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0000000000000177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller A, Reisman DS, Billinger SA, et al. Moderate-intensity exercise versus high-intensity interval training to recover walking post-stroke: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2021;22(1):457. doi: 10.1186/s13063-021-05419-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Awad LN, Palmer JA, Pohlig RT, Binder-Macleod SA, Reisman DS. Walking Speed and Step Length Asymmetry Modify the Energy Cost of Walking After Stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2015;29(5):416–423. doi: 10.1177/1545968314552528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ferguson B. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription 9th Ed. 2014. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2014;58(3):328. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eriksen BA, Eriksen CW. Effects of noise letters upon the identification of a target letter in a nonsearch task. Perception & Psychophysics. 1974;16(1):143–149. doi: 10.3758/BF03203267 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Delorme A, Makeig S. EEGLAB: an open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;134(1):9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gratton G, Coles MGH, Donchin E. A new method for off-line removal of ocular artifact. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1983;55(4):468–484. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(83)90135-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Olvet DM, Hajcak G. Reliability of error-related brain activity. Brain Res. 2009;1284:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.05.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Predovan D, Fraser SA, Renaud M, Bherer L. The effect of three months of aerobic training on stroop performance in older adults. J Aging Res. 2012;2012:269815. doi: 10.1155/2012/269815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Langlois F, Vu TTM, Chassé K, Dupuis G, Kergoat MJ, Bherer L. Benefits of physical exercise training on cognition and quality of life in frail older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2013;68(3):400–404. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gajewski PD, Ferdinand NK, Kray J, Falkenstein M. Understanding sources of adult age differences in task switching: Evidence from behavioral and ERP studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;92:255–275. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wild-Wall N, Falkenstein M, Hohnsbein J. Flanker interference in young and older participants as reflected in event-related potentials. Brain Research. 2008;1211:72–84. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Willemssen R, Falkenstein M, Schwarz M, Müller T, Beste C. Effects of aging, Parkinson’s disease, and dopaminergic medication on response selection and control. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32(2):327–335. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dierolf AM, Schoofs D, Hessas EM, et al. Good to be stressed? Improved response inhibition and error processing after acute stress in young and older men. Neuropsychologia. 2018;119:434–447. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2018.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dierolf AM, Fechtner J, Böhnke R, Wolf OT, Naumann E. Influence of acute stress on response inhibition in healthy men: An ERP study. Psychophysiology. 2017;54(5):684–695. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cassady K, Ruitenberg MFL, Reuter-Lorenz PA, Tommerdahl M, Seidler RD. Neural Dedifferentiation across the Lifespan in the Motor and Somatosensory Systems. Cerebral Cortex. 2020;30(6):3704–3716. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhz336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Greeley B, Rubino C, Denyer R, et al. Individuals with Higher Levels of Physical Activity after Stroke Show Comparable Patterns of Myelin to Healthy Older Adults. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2022;36(6):381–389. doi: 10.1177/15459683221100497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bloom MS, Orthmann-Murphy J, Grinspan JB. Motor Learning and Physical Exercise in Adaptive Myelination and Remyelination. ASN Neuro. 2022;14:17590914221097510. doi: 10.1177/17590914221097510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hendrikse J, Kandola A, Coxon J, Rogasch N, Yücel M. Combining aerobic exercise and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation to improve brain function in health and disease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;83:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goodwin ML, Harris JE, Hernández A, Gladden LB. Blood Lactate Measurements and Analysis during Exercise: A Guide for Clinicians. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2007;1(4):558–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Maddock RJ, Casazza GA, Buonocore MH, Tanase C. Vigorous exercise increases brain lactate and Glx (glutamate+glutamine): a dynamic 1H-MRS study. Neuroimage. 2011;57(4):1324–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.05.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dalsgaard MK. Fueling cerebral activity in exercising man. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26(6):731–750. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dalsgaard MK, Quistorff B, Danielsen ER, Selmer C, Vogelsang T, Secher NH. A reduced cerebral metabolic ratio in exercise reflects metabolism and not accumulation of lactate within the human brain. J Physiol. 2004;554(Pt 2):571–578. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.055053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Blicher JU, Near J, Næss-Schmidt E, et al. GABA levels are decreased after stroke and GABA changes during rehabilitation correlate with motor improvement. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2015;29(3):278–286. doi: 10.1177/1545968314543652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stavrinos EL, Coxon JP. High-intensity Interval Exercise Promotes Motor Cortex Disinhibition and Early Motor Skill Consolidation. J Cogn Neurosci. 2017;29(4):593–604. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_01078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wanner P, Cheng FH, Steib S. Effects of acute cardiovascular exercise on motor memory encoding and consolidation: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;116:365–381. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dal Maso F, Desormeau B, Boudrias MH, Roig M. Acute cardiovascular exercise promotes functional changes in cortico-motor networks during the early stages of motor memory consolidation. Neuroimage. 2018;174:380–392. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.03.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.