Summary

Background

Diagnosing Cushing’s syndrome (CS) is highly complex. As the diagnostic potential of urinary steroid metabolome analysis by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) in combination with systems biology has not yet been fully exploited, we studied a large cohort of patients with CS.

Methods

We quantified daily urinary excretion rates of 36 steroid hormone metabolites. Applying cluster analysis, we investigated a control group and 168 patients: 44 with Cushing’s disease (CD) (70% female), 18 with unilateral cortisol-producing adrenal adenoma (83% female), 13 with primary bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia (PBMAH) (77% female), and 93 ruled-out CS (73% female).

Findings

Cluster-Analysis delineated five urinary steroid metabotypes in CS. Metabotypes 1, 2 and 3 revealing average levels of cortisol and adrenal androgen metabolites included patients with exclusion of CS or and healthy controls. Metabotype 4 reflecting moderately elevated cortisol metabolites but decreased DHEA metabolites characterized the patients with unilateral adrenal CS and PBMAH. Metabotype 5 showing strong increases both in cortisol and DHEA metabolites, as well as overloaded enzymes of cortisol inactivation, was characteristic of CD patients. 11-oxygenated androgens were elevated in all patients with CS. The biomarkers THS, F, THF/THE, and (An + Et)/(11β-OH-An + 11β-OH-Et) correctly classified 97% of patients with CS and 95% of those without CS. An inverse relationship between 11-deoxygenated and 11-oxygenated androgens was typical for the ACTH independent (adrenal) forms of CS with an accuracy of 95%.

Interpretation

GC-MS based urinary steroid metabotyping allows excellent identification of patients with endogenous CS and differentiation of its subtypes.

Funding

The study was funded by the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung and the Eva-Luise-und-Horst-Köhler-Stiftung.

Keywords: Cushing’s disease, Steroid profiling, Hypercortisolism, GC-MS analysis

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

The differential diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome belongs to the most complex fields in medicine. In clinical routine, a complex panel of various diagnostic tests such as the 1 mg-low-dose dexamethasone suppression test, the urinary free cortisol in a 24 h collection, the late-night salivary cortisol and the measurement of ACTH is usually required for diagnosis and subtyping of Cushing’s syndrome. To capture the past role of urinary steroid analysis in the diagnosis and subtyping of Cushing’s syndrome we searched PubMed using the key words “Cushing’s syndrome”, “urinary steroid metabolome”, “GC-MS analysis” with papers published up to 6/2023. The number of studies found was limited. Comprehensive data on patients with different subtypes of Cushing’s syndrome were missing. Sample sizes of patients were mostly small.

Added value of this study

The novelty of our data is twofold: 1. By combining state of the art multisteroid analytics by the platform technique gas chromatography-mass spectrometry with systems biology statistical approaches, we succeeded in discerning affected from unaffected individuals as well as in further delineating the various subtypes of Cushing’s syndrome by metabolic pattern analysis. This concept of metabotyping is typical for the multiomics field of precision healthcare. The hitherto largest sample of patients was recruited from the German Cushing Registry; 2. Metabotyping was based on typical constellations of precursors and metabolites of cortisol, DHEA, and the recently rediscovered group of 11-oxygenated androgens and allowed for insights into steroid metabolism in CS. Four biomarkers correctly classified patients with CS by 97%. 11-oxygenated androgens were primarily responsible for androgenization and discriminative for ACTH-independent forms of CS.

Implications of all the available evidence

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of CS were ranked as one of the most important research topics in a recent consensus (Fleseriu et al., 2021). In addition to previous studies, the use of hormonal production rates as with GC-MS urinary steroid metabotyping allows for a dynamic approach to characterize steroid metabolism in CS implying the potential for a high diagnostic accuracy. It can be expected that hitherto unmet clinical needs will be addressed by shortened diagnosis times and reduced diagnostic complexity. In future, highly specialized superregional laboratories could implement and offer GC-MS urinary steroid metabotyping. The metabolomics approach that allows to capture as many steroid metabolites as possible will, together with pattern analysis by algorithms, open new avenues in better delineating the various forms of CS.

Introduction

Of all chromatographic techniques, gas chromatography (GC) has the highest separation power for saturated and unsaturated steroid hormone metabolites.1 In combination with mass spectrometry (MS) applying hard ionization, it allows for the most comprehensive and specific characterization of steroid metabolomes.1,2 GC-MS urinary steroid hormone metabolome analysis has developed into a translational analytical technique3,4 that has proven its value in characterizing physiological processes of adrenal steroid hormone secretion,5,6 or in delineating inborn disorders of steroidogenesis as well as steroid excess syndromes caused by adrenal tumours.7, 8, 9, 10 The 24-h urinary steroid metabolome gives a detailed insight into alterations of the steroid flow in different diseases.11,12 GC-MS urinary steroid metabotyping has gained further importance since it has proven highly valuable in monitoring treatment of children with congenital adrenal hyperplasia13 or primary adrenal insufficiency.14,15 It has also been successfully used to identify specific metabolic signatures in children with obesity, insulin resistance, or liver diseases.16,17 Another advantage of urinary steroid profiling in the context of adrenal incidentalomas is the early identification of patients with adrenocortical carcinoma.18

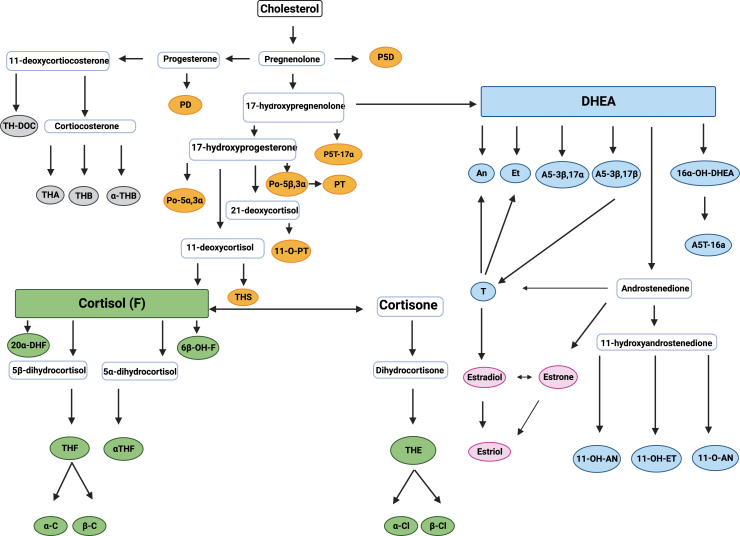

The pathways of human steroid biosynthesis and catabolism are complex (Fig. 1). Basically, three different groups of metabolites can be discerned according to their basic carbon structures: estrogens are C18-steroids; androgens are C19-steroids mainly deriving from DHEA, 11-hydroxyandrostenedione, or testosterone. The group of C21-steroids can be sub-differentiated into metabolites of progesterone or 17-hydroxyprogesterone (progestogens), cortisol (glucocorticoids), and corticosterone. Steroid hormones and their metabolites are primarily excreted into urine making GC-MS urinary steroid analysis a perfect method of assessing the overall human steroid metabolome in a holistic approach.1

Fig. 1.

Steroid pathway and urinary steroid metabolites. Colored metabolites = urinary steroid metabolites. Grey = Aldosterone precursors. Yellow = Intermediate and progesterone metabolites. Blue = Androgen metabolites. Green = glucocorticoid metabolites. Pink = estrogens. E1 = estrone. E2 = estradiol. E3 = estriol. T = testosterone. An = androsterone. Et = etiocholanolone. DHEA = dehydroepiandrosterone. 16α-OH-DHEA = 5-Androstene-3β,16α-diol-17-one. A5-3β,17α = 5-Androstene-3β,17α-diol. A5-3β,17β = androstenediol-17β. A5T-16a = androstenetriol-16α. 11-OH-AN = 11-hydroxy-androsterone. 11-O-AN = 11-oxo-androsterone. 11-OH-ET = 11-hydroxy-etiocholanolone. PD = pregnanediol. PT = pregnanetriol. P5D = 5-pregnenediol. P5T-17α = 5-pregnenetriol-17α. Po-5β,3α = 17a-OH-pregnanolone. Po-5α,3α = 5α-Pregnane-3α,17α-diol-20-one. 11-O-PT = 11-oxo-pregnanetriol. THS = tetrahydro-11-deoxycortisol. THE = 5β-Pregnane-3α,17 α,21-triol-11,20-dione. THF = 5β-Pregnane-3α,11β,17α,21-tetrol-20-one. αTHF = 5α-Pregnane-3α,11β,17α,21-tetrol-20-one. α-Cl = α-Cortolone. β-Cl = β-Cortolone. α-C = a-Cortol. β-C = β-Cortol. 6β-OH-F = 6β-hydroxycortisol. 20α-DHF = 20α-dihydrocortisol. THA = tetrahydro-11-dehydro-corticosterone. THB = 5β-Pregnane-3α,11β,21-triol-20-one tetrahydro-corticosterone. α-THB = allo-tetrahydro-corticosterone. TH-DOC = tetrahydro-11-deoxycorticosterone.

Figure created with Biorender.com.

Cushing’s syndrome (CS) is a rare disease19 with a variety of signs and symptoms. Early diagnosis presents a major diagnostic challenge: a dominant leading symptom is missing, atypical presentation is common, and symptoms overlap with those of metabolic syndrome or polycystic ovarian syndrome. Furthermore, prevalence and severity of symptoms may vary considerably between patients within a particular subtype of CS. According to diagnostic guidelines and a current consensus,20,21 at least two of the following three tests have to show abnormal results in order to diagnose CS: the 1 mg-low-dose-dexamethasone-suppression-test, the late-night salivary cortisol concentration and the urinary excretion of free cortisol in a 24-h collection.21 As no single test offers excellent sensitivity or specificity,22 there remain a number of reasons for false negative and false positive test results, which is the reason why all three tests should be performed in every single patient. This is reflected by a relevant number of patients with clinical and biochemical inconclusive results. Both patients with CS but also patients who do not suffer from CS, can be affected.

Urinary and plasma steroid analysis have been used to characterize patients with CS in comparison to healthy controls. Using GC-MS urinary steroid analysis, Stewart et al. showed in a study with 22 patients with CS that they have a significant increase in urinary cortisol and all its metabolites and that global 11β-hydroxysteroid-dehydrogenase (11-βHSD) activity is defective.23 Likewise, increased excretion of cortisol and its metabolites and decreased ratios of THE/THF seemed to be a typical feature of CS according to the study of Homoki et al. with 18 patients applying GC.24 In a GC-MS based study by Kotlowska et al.,25 patients with autonomous adrenal cortisol secretion and 16 patients with CS could be differentiated from healthy controls by two different approaches, in which 6 urinary steroid metabolites were diagnostically indicative.25 To distinguish patients with CS from healthy controls, the following metabolites were used: tetrahydrocortisol, etiocholanolone, α–cortol, tetrahydrocortisone, tetrahydro−11−dehydrocorticosterone, and tetrahydrocorticosterone.

Further studies showed that plasma DHEA was often elevated in ACTH-dependent CS but not in adrenal CS.26, 27, 28 Additionally, different adrenal tumours, such as pheochromocytomas and adrenocortical carcinomas can be distinguished by a panel of plasma steroids and metanephrines; however, it seems to be difficult to distinguish patients with autonomous cortisol secretion from patients with nonfunctioning adrenal adenomas.29

Based on these pathophysiological reflections and the available data, it is reasonable to expect relevant changes among different urinary steroid metabolites in patients with CS. As studies with larger sample sizes analysing the full spectrum of steroid metabolites in Cushing’s disease (CD) and adrenal CS using GC-MS are missing, we intended to carry out an explorative study making use of the German Cushing Registry. We analysed the 24-h urinary steroid metabolome by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry of patients with CD, with different forms of adrenal CS (unilateral and bilateral), as well as of patients in whom CS was clinically suspected but finally excluded. Using a systems biology metabolomics approach, we aimed at identifying suitable metabolite patterns and biomarkers allowing to distinguish patients with CS from healthy individuals and enabling further subtyping of the individual forms of CS.

Methods

Subjects

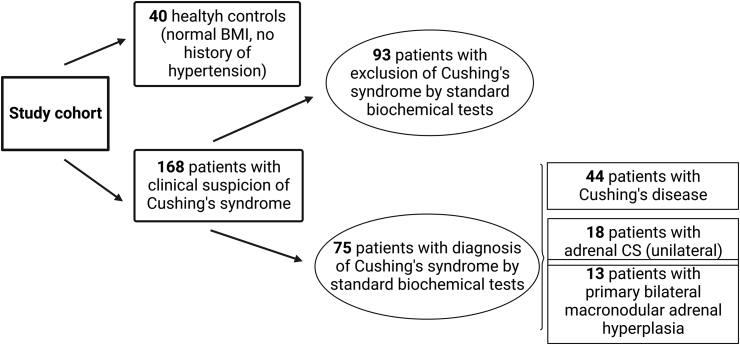

We investigated the steroid metabolomes in 24-h urinary specimens obtained from 208 adults aged 45 (34–54) years. These individuals were divided into the following clinical subgroups: 44 patients were diagnosed with surgically confirmed CD, 18 with unilateral adrenal CS (cortisol-producing adenoma), 13 with primary bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia (PBMAH), and 93 patients were evaluated for CS, which was excluded by biochemical testing and clinical follow-up for 6–12 months. 40 healthy controls were included as well. Table 1 shows the basic characteristics of these subgroups. Data on sex were self-reported by study participants. The study cohort is shown in Fig. 2.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with Cushing’s syndrome and control groups.

| Healthy controls N = 40 |

Rule-out CS N = 93 |

Cushing’s disease N = 44 |

Unilateral adrenal CS N = 18 |

PBMAH N = 13 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (female) | 50% (20/40) | 73% (68/93) | 70% (31/44) | 83% (15/18) | 77% (10/13) | 0.046a |

| Age (years) | 50 (44–55) | 36 (24–49) | 46 (37–55) | 48 (41–59) | 57 (52–69) | <0.001b |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24 (23–26) | 32 (27–38) | 29 (24–33) | 29 (26–35) | 38 (27–48) | <0.001b |

| Hypertension | 0% | 68% (63/93) | 91% (40/44) | 89% (16/18) | 92% (12/13) | <0.001a |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0% | 15% (14/93) | 30% (13/44) | 28% (5/18) | 39% (5/13) | <0.001a |

| Late-night salivary cortisol (<1.5 ng/mL) | n.a. | 1.0 (0.6–1.6) | 9.3 (4.8–15.0) | 6.0 (3.2–12.0) | 4.5 (3.6–8.0) | <0.001b |

| Urinary free cortisol (<150 μg/24 h) | n.a. | 188 (122–258) | 690 (346–827) | 253 (113–534) | 225 (130–374) | <0.001b |

| 1 mg-low-dose-dexamethasone-suppression test (<2.0 μg/dL) | n.a. | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 14.5 (8.5–28.4) | 16.6 (14.0–23.5) | 8.0 (3.8–16.8) | <0.001b |

| ACTH (normal: 4–50 pg/mL) | n.a. | 13 (10–20) | 57 (37–81) | 5 (2–5) | 4 (3–10) | <0.001b |

CS = Cushing’s syndrome. PBMAH = primary bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia. ACTH = adrenocorticotropin. BMI = body mass index.

N is the number of non-missing values. Median and ranges are shown. Tests used: aPearson chi-square test; bKruskal–Wallis test.

Fig. 2.

Study cohort. CS = Cushing’s syndrome.

Figure created with Biorender.com.

This multicentre-study was performed as part of the prospective German Cushing Registry and of the prospective cohort of Berlin-Brandenburg for patients with PBMAH. All patients were referred to the respective centres (Munich, Berlin, Würzburg) because of clinical suspicion of CS and underwent standard clinical and biochemical screening, including the low dose dexamethasone suppression test (LDDST), late-night salivary cortisol sampling (LNSC), and 24-h urine collection for urinary free cortisol (UFC) as initial steps of the diagnostic work-up. Depending on test results, further biochemical characterization was performed according to current guidelines.20 Patients with ectopic or mild autonomous cortisol secretion were not included in the study. All subjects collected 24-h urines at the time of diagnosis. As a validation and to control full collection, creatinine levels were measured in the urinary samples. Additionally, we included a control group of healthy subjects without clinical features suggestive for CS. All of these subjects had a body mass index (BMI) within the reference range and no history of hypertension (20 men, 20 women; all samples from the University of Dresden).

Ethics

Permission of the Ethic Committees of all involved centres was obtained (vote number: 152-10, EK 189062010 and EA1/188/16); patients provided written informed consent. The study was conducted in compliance with ethical approval.

Targeted urinary steroid metabolome analysis by GC–MS

GC-MS analysis (carried out at the University Hospital Giessen) was used to quantify steroids in 24 h-urinary specimens.5,30 Solid phase extraction (Sep-Pak C18 cartridges, WAT020515, Waters, Milford, MA, USA) was used to extract free and conjugated steroids from 5 mL aliquots of 24 h-urine-samples. Conjugates were enzymatically hydrolyzed (type H-1 sulfatase from helix pomatia, S9626-100KU, Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Taufkirchen, Germany) followed by recovery of the hydrolyzed steroids by a second solid phase extraction step.31 5α-androstane-3α,17α-diol (28-115-A 1150, Paesel + Lorei, Frankfurt, Germany) and stigmasterol (S2424-5G, Sigma-Aldrich Chemie, Steinheim, Germany) were added as internal standards in known amounts before formation of methyloxime-trimethylsilyl ethers (Methoxyamine hydrochloride, 226904-5G, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany; TSIM, 701310.201, Macherey-Nagel, Dueren, Germany). GC was carried out on an Optima-1 MS fused silica column (length 25 m, film thickness 0.1 μm, inner diameter 0.2 mm; 726204.25, Macherey-Nagel, Dueren, Germany) housed in an Agilent Technologies 6890 series GC equipped with an Agilent 7683 series injector that was directly interfaced to an Agilent Technologies 5975 inert XL mass selective detector (Agilent Technologies GmbH, Boeblingen, Germany). Carrier gas was helium (650702 F50 P200, Nippon Gases, Germany). GC oven was heated to 80 °C for 2 min to conduct injections and temperature was increased up to 190 °C (1 min) (20 °C/min). Finally, steroids were separated increasing the temperature by 2.5 °C/min up to 272 °C.31 The MS was run in the targeted, i.e., selected ion monitoring mode. After calibration, values for the excretion of individual steroids were determined by measuring the selected ion peak areas against the internal standard areas. Quantitation took place in the linear range of the calibration plots. For all urinary steroids measured, intraassay precision varied between 1.7% (for 17b-Adiol) and 9.5% (for 20α-DHF) and inter-assay precision ranged between 1.1% (for α-cortol) and 9.5% (for 11-OH-An).32

Statistics

Due to the explorative design of the study, a sample size calculation was omitted. For statistical analysis, R was used (R Core Team (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/).

Baseline characteristics of patients of clinical subtypes were summarized as frequencies or median and upper and lower quartiles.

In order to describe the distribution of the steroid metabolomes, location and spread were summarized by median and upper and lower quartiles. Group comparisons were performed by Pearson's chi-squared test or Kruskal–Wallis test. For all further analyses urinary steroids were log2-transformed to obtain normal distribution. In order to describe the expression patterns by heatmap (R-library: pheatmap), log2-transformed values were normalized by quantile normalization (R-library: preprocessCore33). For multivariate analyses log2-transformed values were normalized by z-scores on the base of groups without Cushing’s syndrome (NON CS). PAM (partition around medoids) clustering (R-library: cluster) were used to map the data matrix into five cluster and predicted cluster membership were compared to disease subgroups. Informative steroid metabolomes were selected as biomarker by univariate logistic regression with the binary (CS, NON CS) dependent variable followed by multivariate logistic regression analysis. Using multiple steroids from the same group (e.g., multiple cortisol metabolites) was avoided, as there was a strong correlation between them. Multiple analysis with different combinations of steroids were run to finally identify the presented steroids as the best combination to predict the subtypes. Selected biomarkers were examined by exploratory receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis and a cut-off was estimated by Youden Index. In addition, a common cut-point was estimated from the predicted probabilities to describe the correct group assignment. Subgroup analysis with CS groups only were performed by multinominal logistic regression with the three CS subtypes as dependent variable. p-values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Role of the funding source

The funding sources had not involvement in the study or in the decision to submit the manuscript.

Results

Baseline characteristics of clinical subtypes

The baseline characteristics of the clinical subtypes are shown in Table 1. There are considerable clinical differences regarding hypertension, diabetes mellitus and body weight between patients with CS and rule-out/healthy controls. As expected, cortisol levels are significantly higher in patients with CS in all three standard tests.

Metabolic characterization of clinical subtypes

The metabolic characteristics of the clinical subtypes are presented in Table 2 (raw data) and Fig. 3 (normalized data). These data are also shown separately for women and men in the supplement. Cortisol and all its tetra- and hexahydrated metabolites were markedly increased in patients with CD at the time of diagnosis. Their 24-h urinary cortisol excretion rates were on average 3.2 times higher than those of the control group. Similarly, excretion rates of corticosterone metabolites (aldosterone precursors) were 1.5 times elevated in patients with CD. Finally, all of the adrenal androgen metabolite excretion rates were strikingly increased in patients with CD: The 11-deoxygenated adrenal androgens were 1.5 times as high as in the control group, while the 11-oxygenated androgens were even higher (2.7 times as high), resulting in an increased ratio between the 11-oxygenated androgens and the 11-deoxygenated adrenal androgen.

Table 2.

Most important sums and ratios of steroid excretion rates (medians, ranges; μg/24 h) in Cushing patients and control groups.

| Healthy controls N = 40 |

Rule-out CS N = 93 |

Cushing’s disease N = 44 |

Unilat. Adren. CS N = 18 |

PBMAH N = 13 |

p-values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24-h urinary excretion (in mL) | 2060 (1485–2600) | 2100 (1500–2780) | 2425 (1710–2750) | 2265 (1650–3363) | 2650 (1450–2810) | 0.47 |

| C18-steroids (estrogens) | ||||||

| Sum of major estrogens (E1 + E2 + E3) | 6 (6–41) | 21 (6–52) | 27 (8–58) | 6 (6–22) | 19 (6–62) | 0.023 |

| C19-steroids | ||||||

| Sum of DHEA and its major metabolites (DHEA + 16α-OH-DHEA + A5T-16α) | 582 (260–1287) | 667 (266–1329) | 1369 (653–2615) | 85 (67–172) | 209 (142–400) | <0.001 |

| C19-steroids | ||||||

| Sum of 11-deoxygenated adrenal androgens (An + Et + A5-3β,17α + A5-3β,17β + DHEA + 16α-OH-DHEA + A5 T-16α) | 3415 (2000–5116) | 3504 (2076–5210) | 5246 (3299–8594) | 730 (540–1343) | 1548 (833–2212) | <0.001 |

| C19-steroids | ||||||

| Sum of 11-oxygenated androgens (11-OH-An, 11-O-An, 11-OH-Et) | 863 (554–1102) | 600 (431–968) | 2297 (1376–3726) | 1383 (817–2796) | 1970 (1253–2421) | <0.001 |

| C19-steroids | ||||||

| Ratio: 11-oxygenated androgens/11-deoxygenated adrenal androgens | 0.23 (0.18–0.34) | 0.17 (0.10–0.31) | 0.45 (0.23–0.67) | 1.42 (0.92–4.09) | 1.27 (0.63–2.29) | <0.001 |

| C19-steroids | ||||||

| Ratio: 11-OH-Et/DHEA and its major metabolites | 0.66 (0.16–1.08) | 0.22 (0.08–0.69) | 0.67 (0.29–1.87) | 4.98 (3.65–22.57) | 2.56 (0.80–11.65) | <0.001 |

| C21-steroids | ||||||

| Ratio: Po5b3a/Po5a3a | 5.37 (3.47–7.76) | 4.78 (3.59–7.28) | 8.27 (6.48–13.74) | 19.17 (7.94–38.45) | 7.85 (4.53–11.72) | <0.001 |

| C21-steroids | ||||||

| Sum of major cortisol metabolites (5α-THF + THF + THE) | 4649 (3493–5862) | 5440 (3591–7639) | 14,111 (9929–20,815) | 9301 (6245–13,070) | 6601 (3872–9334) | <0.001 |

| C21-steroids | ||||||

| Overall cortisol metabolite excretion (5α-THF + THF + THE + a-C + b-C + a-Cl + b-Cl) | 6552 (4846–7996) | 7699 (5674–11,057) | 20,687 (14,734–29,907) | 14,140 (9965–19,916) | 11,723 (6135–14,507) | <0.001 |

| C21-steroids | ||||||

| Sum of corticosterone metabolites (THA, THB, aTHB) | 459 (346–642) | 393 (248–568) | 667 (468–1059) | 411 (341–513) | 370 (238–589) | <0.001 |

CS = Cushing’s syndrome. PBMAH = primary bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia.

Test used: Kruskal–Wallis test.

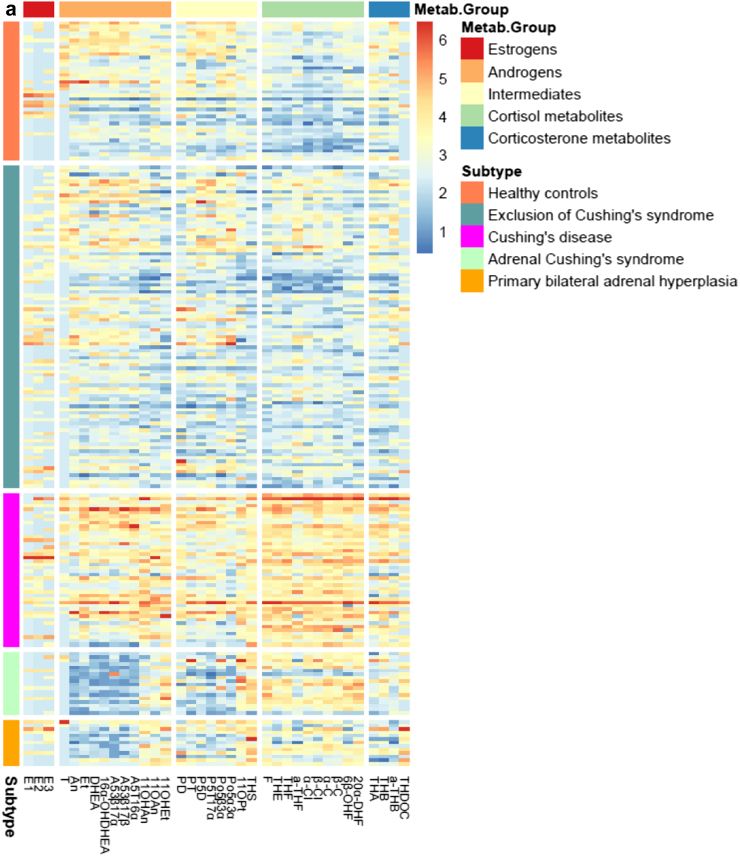

Fig. 3.

Heatmap of the different subtypes. Heatmap of the expression pattern of each patient (rows) of (a) metabolites, grouped into Metab.Groups and (b) enzyme ratios, grouped into Ratio.Groups signed by the respective colors. Patients were grouped into subtypes signed by the respective colors. Log2-transformed expression values of metabolites were normalized by quantile normalization. Red implies a high amount of a metabolite, blue a very low amount. Explanations for the abbreviations of the metabolites are shown in the supplement. It is obvious that there is a clear association between the five metabotypes and the five different clinical subtypes.

In patients with unilateral adrenal CS, cortisol and its metabolites were also elevated (2.2 times), although to a lesser degree than in patients with CD. Some of the androgens, e.g., androsterone and testosterone, were rather low in patients with adrenal CS, but especially the classical adrenal androgens such as DHEA and its major metabolites 16αOH-DHEA und A5T-16α were decreased (0.15 times compared to the control group). However, the recently rediscovered 11-oxygenated androgens, 11-OH-androsterone, 11-O-androsterone as well as 11-OH-etiocholanone, were elevated (1.6 times) resulting in an inverse relation and concomitantly strongly elevated ratio between the 11-oxygenated androgens and the 11-deoxygenated adrenal androgens.

In patients with PBMAH, cortisol metabolites were found to be mildly elevated (1.8 times) compared to healthy controls. The majority of the classical androgen metabolites were also significantly decreased in this patient group (0.5 times in comparison to healthy controls) but not as distinctive as in unilateral adrenal CS. The 11-oxygenated androgens were elevated (2.3 times), even above the extent of the ones in unilateral adrenal CS.

Despite the considerable clinical differences regarding hypertension and body weight between control group and patients with exclusion of CS, their urinary steroid metabotypes were not distinguishable.

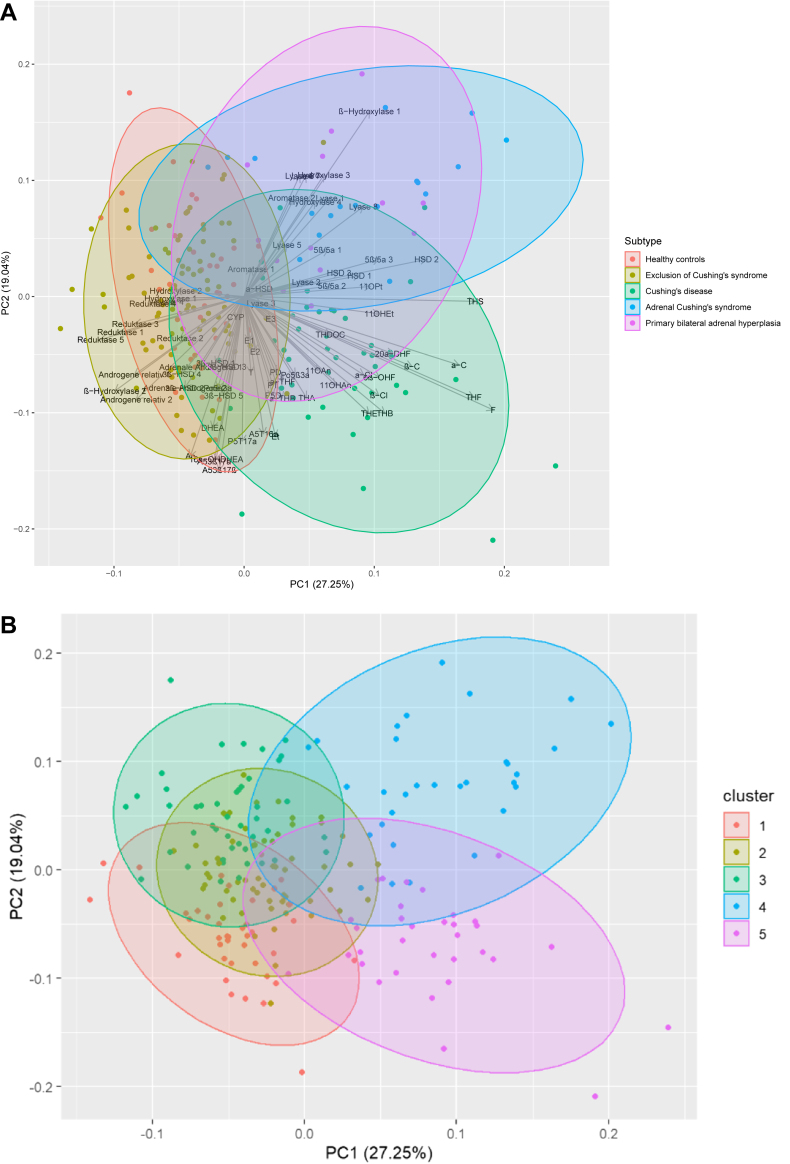

Urinary steroid metabotypes

One of the study goals was to explore whether unsupervised clustering on the base of the 36 urinary metabolites will correctly assign patients to the clinical subgroups. Therefore, PAM-clustering has been performed to predict–corresponding to the five clinical subtypes–five clusters (Fig. 4b). As can be seen in Fig. 4a, the first principal component (PC1) clearly divides the non CS groups (Healthy and Exclusion of CS) from CS groups (Cushing’s disease, unilateral adrenal CS and PBMAH), negative values define most of the individuals in the NON CS group and positive values of the CS patients. Metabolites with long arrows, mostly parallel to PC1, e.g., THS, THF or F seem to have a high discrimination power, whereas short arrows in any direction do not contribute to discrimination of the groups. The second component (PC2) seems to have discrimination power to divide between the groups with any form of CS; most noticable is e.g., (An + Et)/(11β-OH-An + 11β-OH-Et) or Lyase. These metabolites might have a potential to discriminate between the CS groups. Metabolites placed closely together are suspected to have a high correlation, therefore it is possible that they cancel each other. The predicted cluster memberships (Metabotypes) were then compared to the clinical subtypes (Table 3). Overall, the five metabotypes corresponded with the five different clinical subtypes, therefore, the steroid patterns were identical to the ones described above. Metabotype 1 presented an overlap of patients with exclusion of CS and some healthy controls. Metabotype 2 was formed by patients with exclusion of CS and healthy controls. The third group, Metabotype 3, mostly consisted of patients with exclusion of CS and strongly overlapped with Metabotype 1. Metabotype 4 included almost exclusively patients with unilateral adrenal CS and PBMAH. Metabotype 5 consisted almost solely of patients with CD. 16 of 18 PBMAH and 9 of 13 adrenal CS patients are in the same cluster (4). 32 of 44 with CD are in cluster 5. 118 of 133 who are healthy or rule out CS are in cluster 1, 2 and 3.

Fig. 4.

Metabotypes in Cushing’s syndrome: delineation of five metabotypes by GC-MS urinary steroid metabolome analysis. Principal component analysis (PCA) on the log2-transformed values of the 36 urinary metabolites and their ratios normalized by z-scores. Each dot represents 1 of the 74 samples projected to the first and second principal components (PC) explaining together 46.3% (PC1: 27.5%, PC2: 19.04%) of the overall variability. Arrows represent the single metabolites, dots represent the subjects, colored by the respective subtype. The semitransparent coloring shows the result of unsupervised clustering by PAM (partition around medoids) cluster analysis according to the subject’s classification group. Five clusters were previously defined corresponding to the five clinical subtypes in order to predict cluster membership. Overall the five metabotypes correspond clearly with the five different clinical subtypes (see Table 3). Each circle (cluster) represents a metabotype. Dots are individual samples/patients. All urinary metabolites influence the clustering. Red = Cluster 1. Green = Cluster 2. Dark Green = Cluster 3. Blue = Cluster 4. Pink = Cluster 5.

Table 3.

Urinary steroid metabotyping in Cushing patients: cluster formation and association with patient subgroups.

| Clinical Subtype | Metabotype |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | Cluster 5 | |

| N | 40 | 59 | 45 | 31 | 33 |

| Cushing’s disease (N = 44) | 1 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 32 |

| Rule-out CS (N = 93) | 32 | 26 | 34 | 1 | 0 |

| Healthy controls (N = 40) | 7 | 26 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Unilat. Adren. CS (N = 18) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 16 | 0 |

| PBMAH (N = 13) | 0 | 3 | 0 | 9 | 1 |

CS = Cushing’s syndrome. PBMAH = primary bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia.

Predicted cluster membership (Metabotypes) by PAM (partition around medoids) with 36 urinary metabolites in comparison to the observed clinical subtypes.

Bold numbers indicate the most frequent subtype.

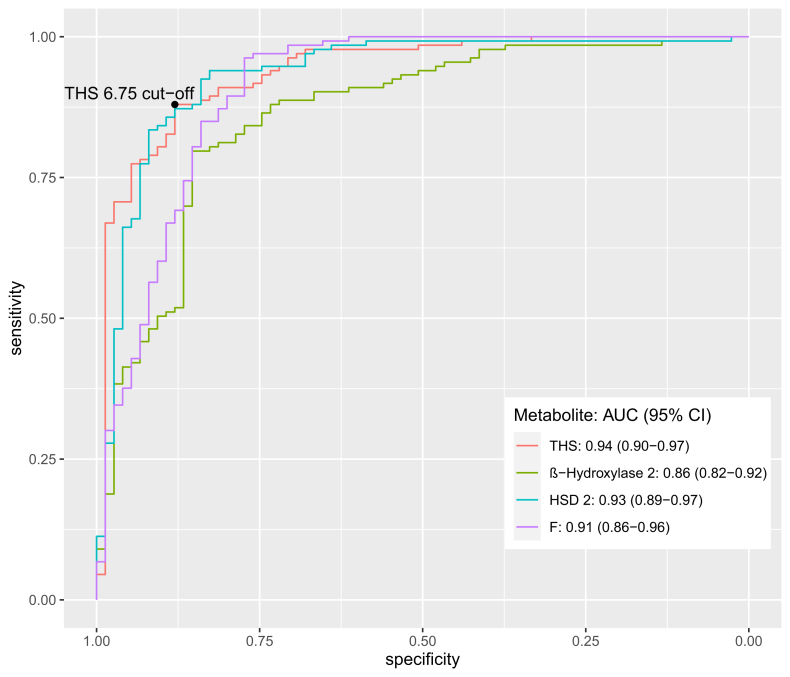

Multivariate and ROC-analysis

Univariate logistic regression analysis showed a couple of significant Odd’s Ratios between patients with and without CS (Table 4). From the CS and NO CS group mean of the respective metabolite it can be concluded that higher values of THS, HSD_2 F increase the chance to have CS. In contrast, higher values of (An + Et)/(11β-OH-An + 11β-OH-Et) decrease the chance to have CS. After multivariate analysis, however, four variables remained significant. Firstly, THS, which is the tetrahydrated metabolite of the immediate cortisol precursor 11-deoxycortisol (Reichstein’s substance S) serving as a marker of 11β-hydroxylase activity. Secondly, the ratio between the main androgen metabolites androsterone and etiocholanolone related to their 11-oxygenated analogues ((An + Et)/(11β-OH-An + 11β-OH-Et)). Thirdly, the ratio between the tetrahydrated metabolites of cortisol and cortisone, which presents a marker of global 11β-hydroxysteroiddehydrogenase activity (THF/THE) (Table 4) and finally, cortisol itself.

Table 4.

Odd’s Ratio of selected metabolites and enzyme ratios: delineation of patients with Cushing’s syndrome.

| Metabolite and ratios Mean (SD) |

CS | NO CS | OR (univariable) | OR (multivariable) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| THS | 7.8 (1.2) | 6.0 (0.7) | 17.21 (8.30–42.09, p < 0.001) | 4.55 (1.42–18.30, p = 0.018) |

| (An + Et)/(11β-OH-An + 11β-OH-Et) | 0.3 (1.2) | 1.9 (1.0) | 0.25 (0.16–0.35, p < 0.001) | 0.23 (0.06–0.66, p = 0.012) |

| (5α-THF + THF + THE)/(An + Et) | 2.5 (1.1) | 1.2 (0.9) | 3.64 (2.53–5.52, p < 0.001) | 1.27 (0.38–4.02, p = 0.681) |

| THF/THE | 0.1 (0.5) | −0.7 (0.3) | 321.34 (75.89–1893.38, p < 0.001) | 28.92 (3.43–365.67, p = 0.004) |

| DHEA | 6.9 (2.6) | 7.6 (2.2) | 0.88 (0.78–1.00, p = 0.057) | 1.36 (0.88–2.16, p = 0.167) |

| F (cortisol) | 8.0 (1.3) | 6.3 (0.6) | 18.95 (8.60–51.77, p < 0.001) | 9.24 (1.85–68.78, p = 0.014) |

CS = Cushing’s syndrome. OR = odd’s ratio. An = androsterone. Et = eticholanolone. DHEA = dehydroepiandrosterone. THS = tetrahydro-11-deoxycortisol. 11β-OH-An = 11-hydroxy-androsterone. 11β-OH-Et = 11-hydroxy-etiocholanolone. THE, THF and 5α-THF = glucocorticoid metabolites.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis with metabolites on CS and no CS patients with odds ratios (OR) p ≤ 0.1.

From the CS and NO CS group mean of the respective log2 transformed metabolite it can be concluded that if doubling the values of THS, THF/THE or F (cortisol) the chance to have CS in comparison to NO CS will increase about the estimated OR. In contrast, higher values of (An + Et)/(11β-OH-An + 11β-OH-Et) decrease the chance to have CS.

Bold numbers indicate significant p-values.

Analysis by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves demonstrated that these four variables optimally discriminated between patients with and without CS (Fig. 5). The AUC with 95% confidence intervals of the four different parameters were as follows: THS: 0.94 (0.90–0.97), (An + Et)/(11β-OH-An + 11β-OH-Et): 0.86 (0.82–0.92), THF/THE: 0.93 (0.89–0.97) and F: 0.91 (0.86–0.96). At the best cut-off of 6.75 using THS, sensitivity was 88% with a specificity of 88%. The predicted probabilities from multiple logistic regression, representing the combination of all four parameters were used to estimate a cut-off through ROC-analysis and Youden Index. Thereby, 97% (CI: 0.91, 1.00) of patients with CS and 95% (CI: 0.90, 0.98) of patients without CS were correctly classified (Table 5).

Fig. 5.

ROC-analysis to differentiate between patients with and without Cushing’s syndrome with the most discriminative urinary steroid metabolites. ROC-analysis to differentiate between patients with and without Cushing’s syndrome with the most discriminative urinary steroid metabolites. The AUCs with 95% confidence intervals of the four different parameters were included. THS, (An + Et)/(11β-OH-An + 11β-OH-Et), HSD 2 and F: Cortisol. At the best cut-off (Youden Index) by of 6.75 using THS, sensitivity was 88% with a specificity of 88%. Red line = THS = tetrahydro-11-depxycortisol. AUC (95% CI): 0.94 (0.90–0.97). Green line = bHydrox_2 = (An + Et)/(11β-OH-An + 11β-OH-Et). An = androsterone. Et = eticholanolone. 11β-OH-An = 11-hydroxy-androsterone. 11β-OH-Et = 11-hydroxy-etiocholanolone. AUC (95% CI): 0.86 (0.82–0.92). Blue line = HSD_2 = THF/THE. THE and THF = glucocorticoid metabolites AUC (95% CI): 0.93 (0.89–0.97). Pink line = F = Cortisol AUC (95% CI): 0.91 (0.86–0.96).

Table 5.

Distinguishing patients with Cushing’s syndrome from those without Cushing’s syndrome by urinary steroid panel (THS, ((An + Et)/(11β-OH-An + 11β-OH-Et)), (THF/THE), cortisol).

| Observed | Predicted |

|

|---|---|---|

| CS (N = 79) | No CS (N = 129) | |

| CS (N = 75) | 73 | 2 |

| No CS (N = 133) | 6 | 127 |

CS = Cushing’s syndrome. An = androsterone. Et = eticholanolone. THS = tetrahydro-11-depxycortisol. 11β-OH-An = 11-hydroxy-androsterone. 11β-OH-Et = 11-hydroxy-etiocholanolone. THE, THF and 5α-THF = glucocorticoid metabolites.

Observed clinical groups (CS/non CS) and predicted classification of multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 4) on selected metabolites: THS, (An + Et)/(11β-OH-An + 11β-OH-Et), THF/THE, F (cortisol). Cut-off of predicted probabilities was calculated by Youden Index through ROC-analysis.

Sensitivity, specificity and positive and negative rates with 95% confidence interval for predicted CS:

Sensitivity (95% CI) 0.97 (0.91, 1.00).

Specificity (95% CI) 0.95 (0.90, 0.98).

False positive rate: 0.05 (0.02, 0.10).

False negative rate: 0.03 (0.00, 0.09).

Differentiation of the subtypes

To discriminate between patients with different subtypes, multinominal logistic regression with only CS-patients was performed. A combination of the metabolites THS, THF and the ratio (An + Et)/(11β-OH-An + 11β-OH-Et) led to the correct identification of the subtypes as follows: 95% of patients with CD, 67% of patients with unilateral adrenal CS and 62% of patients with PBMAH were correctly diagnosed. All in all, 95% were correctly classified as ACTH-dependent CS and 86% as ACTH-independent CS (Tables 6 and 7).

Table 6.

Distinguishing different subtypes of Cushing’s syndrome by urinary steroid panel (THS, THF and (An + Et)/(11β-OH-An + 11β-OH-Et)): a) Results from multinomial logistic regression analysis with the selected metabolites with only CS-patients.

| Metabolites and enzyme ratios | Odds Ratios | CI | p | Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| THS | 17.33 | 1.61–186.61 | 0.019 | Unilateral adrenal CS |

| (An + Et)/(11β-OH-An + 11β-OH-Et) | 0.09 | 0.02–0.44 | 0.004 | Unilateral adrenal CS |

| THF | 0.00 | 0.00–0.19 | 0.009 | Unilateral adrenal CS |

| F | 1.98 | 0.32–12.07 | 0.46 | Unilateral adrenal CS |

| THS | 99.28 | 6.55–1503.69 | 0.001 | PBMAH |

| (An + Et)/(11β-OH-An + 11β-OH-Et) | 0.11 | 0.02–0.67 | 0.017 | PBMAH |

| THF | 0.00 | 0.00–0.005 | 0.002 | PBMAH |

| F | 0.63 | 0.08–5.06 | 0.662 | PBMAH |

Odds Ratios were calculated with the CD group as reference. Odds Ratios represent the fold-change of the adrenal CS and the PBMAH group in comparison to the reference group. As the non CS groups were excluded from the analysis, F (cortisol) has no predictive value.

Bold numbers indicate significant p-values.

Table 7.

Distinguishing different subtypes of Cushing’s syndrome by urinary steroid panel (THS, THF and (An + Et)/(11β-OH-An + 11β-OH-Et)): b) Observed clinical CS-groups and predicted classification of multinominal regression analysis on selected metabolites: THS (An + Et)/(11β-OH-An + 11β-OH-Et), THF/THE.

| Observed | Predicted |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| ACTH-dependent |

ACTH-independent |

||

| CD | Adrenal CS | PBMAH | |

| CD | 42 | 2 | 0 |

| Adrenal CS | 3 | 12 | 3 |

| PBMAH | 1 | 4 | 8 |

CS = Cushing’s syndrome. PBMAH = primary bilateral adrenal hyperplasia. CD = Cushing’s disease. An = androsterone. Et = eticholanolone. THS = tetrahydro-11-depxycortisol. 11β-OH-An = 11-hydroxy-androsterone. 11β-OH-Et = 11-hydroxy-etiocholanolone. THF = glucocorticoid metabolite. F = cortisol.

Discussion

Diagnosing und subtyping of patients with CS can be very challenging in clinical practice. Our study showed that GC-MS urinary steroid metabolome analysis is a helpful diagnostic tool both to establish the diagnosis and also to further differentiate between patients with different subtypes of CS. Furthermore, our metabotyping approach provides insights into the human pathophysiology of steroid metabolism. In addition to the characterization of the various constellations of steroid metabolites in the various forms of Cushing’s syndrome, our findings assign the recently rediscovered group of 11-oxygenated androgens a crucial role in androgenization as well as in the differentiation of patients with the various forms of Cushing’s syndrome.

GC-MS analysis discriminates patients with and without Cushing’s syndrome

As seen by cluster analysis, the different subtypes of CS could be differentiated from healthy controls and patients with exclusion of CS. The clusters matched the subtypes very well, and we did not identify differences in the metabotype within a single subtype. Interestingly, although patients with exclusion of CS suffered from hypertension and were obese, their steroid signature was not different from healthy controls.

With regard to diagnostic accuracy, our data indicate that a single targeted urinary steroid metabolome analysis by GC-MS obtained from a 24-h urine collection—which is independent of hormonal circadian rhythm—is at least equivalent to a panel of screening tests hitherto usually employed in routine clinical care: The accuracy of the UFC (urinary free cortisol), the LNSC (late-night salivary cortisol) and the LDDST seem to be similar according to a meta-analysis (Likelihood ratio of positive test result (LR+) of UFC: 10.6 (CI 5.5.–20.5), LR+ of LNSC: 8.8 (CI 3.5–21.8), LR+ of LDDST: 16.4 (CI 9.3–28.8)).3, 34

In our approach, we correctly classified 96% of CS patients using four different urinary steroid parameters as biomarkers. Focusing on the studies using GC-MS, Kotlowska identified 94% of patients correctly, similar to our study. A slightly lower diagnostic accuracy was reported in a study using plasma steroid analysis by LC-MS with 90.5% correctly classified patients.27

The urinary steroid biomarker panel for diagnosing Cushing’s syndrome

Using the panel of urinary steroid biomarkers, which consists of four different parameters, we were able to correctly classify the majority of patients. The biomarker, which was most discriminative in delineating patients with CS, was the immediate cortisol precursor metabolite THS. We speculate that increased activities of adrenal enzymes of steroid biosynthesis, either due to increased ACTH stimulation or via autonomous mechanisms, lead to increased production of 11-deoxycortisol and its metabolite THS. The effect of ACTH on the levels of 11-deoxycortisol is well-known; ACTH stimulation increases 11-deoxycortisol but also corticosterone,35 an effect that we also observed in our group of patients with CD. Furthermore, we found that THS measured in urine has an even better AUC than its plasma precursor 11-deoxycortisol (0.94 vs. 0.87), when used as diagnostic marker in the steroid panel previously described in a plasma steroid metabolome study in patients with CS.27

The second parameter is the ratio between the main androgen metabolites An and Et related to their 11-oxygenated analogues. This ratio seems to be important, as in all patients with CS—i.e., CD, PBMAH and unilateral adrenal CS—the 11-oxygenated androgens were significantly elevated compared to healthy controls, while the classical androgens were either suppressed (unilateral adrenal CS and PBMAH) or moderately elevated (CD).

The ratio between THF/THE, which is basically a ratio between cortisol and cortisone metabolites, is higher in patients with CS, which indicates the overloaded global 11β-hydroxysteroiddehydrogenase activity due to the high levels of cortisol.

Finally, cortisol itself is part of the panel. Although the traditional free cortisol measured by immunoassay in a 24 h-urine sample has not the best sensitivity and specificity, total urinary cortisol as measured by GC-MS after enzymatic hydrolysis, reflects hypercortisolism much better.

Differentiation of subtypes of Cushing’s syndrome by urinary steroid profiling

Cortisol and its metabolites were significantly increased in all subgroups of patients with CS. Though patients with CD had much more pronounced excretion rates than those with adrenal forms of CS, cortisol metabolites alone did not allow for reliable differentiation between these subgroups. However, adrenal androgen metabolites proved beneficial in further differentiating the subgroups of patients with CS.

The typical adrenal androgen DHEA and its classical downstream metabolites such as 16αOH-DHEA, A5T (androstenetriol-16α), 5-androstene-3β,17α-diol, 5-androstene-3β,17β-diol (androstenediol), 5α-androstane-3α-ol-17-one (androsterone), and 5β-androstane-3α-ol-17-one (etiocholanolone) were all elevated in patients with CD, a finding due to the stimulating effect of ACTH-excess. However, in patients with ACTH-independent adrenal forms of CS, DHEA and its classical metabolites were found to be considerably decreased. It is well known that apart from cortisol, other metabolites such as deoxycorticosterone and the C19 adrenal androgens are responsive to changes in ACTH-levels.36 The high levels of cortisol as seen in patients with adrenal CS, lead to suppression of ACTH and consecutively to a reduced production of adrenal androgens.

Recently, Ahn et al. have shown that plasma DHEA is an as nearly good parameter as ACTH to differentiate between patients with adrenal and pituitary CS.37 Furthermore, DHEA and ACTH-levels show a linear correlation.37 The same effect was shown in other studies using serum concentrations of DHEA-S: DHEA-S is decreased in patients with adrenal CS and elevated in patients with CD.38 DHEA-S can also be used to identify patients with autonomous cortisol secretion early on.39 We now can confirm these findings by urinary steroid metabolome analysis: DHEA and its downstream metabolites reliably delineate patients with adrenal CS from those with CD.

The 11-oxygenated androgens

In our GC-MS study, we have investigated the so far largest cohort of patients with CS. Our findings confirm hitherto published results in plasma or urine on the diagnostic role of cortisol, and several of its precursors or metabolites. However, our results regarding the patterns and ratio between 11-deoxygenated and particularly the 11-oxygenated C19 androgens are of value. These 11-oxygenated androgens have been known for a long time, but just recently they were rediscovered becoming focus of research again.40 They are associated with androgen excess disorders, for example PCOS41 or congenital adrenal hyperplasia.42,43 Our finding that these androgens dominated in all forms of CS might be a reason, why symptoms of androgen excess such as menstrual disorders, acne and hirsutism are both prominent in patients with ACTH-dependent and ACTH-independent CS—although the classical androgens are suppressed in patients with ACTH-independent CS. It is known, that the 11-oxygenated androgens are nearly as potent as the classical androgens.44 To our knowledge, the role of the 11-oxygenated androgens in CS has only been mentioned in patients with CD so far.45

Furthermore, we showed, that the ratio between classical adrenal androgens and the 11-oxygenated androgens was altered in patients with CS. The ratio between the 11-oxygenated and the 11-deoxygenated androgens was higher in patients with CD compared to healthy controls and even higher in patients with adrenal forms of CS (Table 2). The augmentation of the latter ratio is due to the fact that in addition to the elevated 11-oxygenated androgens the 11-deoxygenated ones are decreased. This decrease of the 11-deoxygenated androgens can be explained by a lacking ACTH-stimulation. Additionally, the 11-oxygenated androgens are high, as about 10% of cortisol is metabolized to these androgens (particularly to 11OH-Et) as already described in 1954 by Dorfman.46 Excess cortisol as is the case in CS will fuel this process. It is interesting to note that patients with CD maintain a similar balanced ratio between DHEA and cortisol production as healthy controls as is reflected by the ratio 11-OH-Et/DHEA. However, this equilibrium changes drastically in the adrenal forms of CS favouring 11OH-Et. In the latter subtypes of CS, it seems that the cortisol-catabolism is more directed towards 11OH-Et and concomitantly 5β-reduction is favoured as also evidenced by the ratio Po5b3a/Po5a3a.

Strengths and limitations

Regarding the strengths of our study, first of all, our patient allocation was multicentric. We analysed a complete, large data set from the German Cushing’s registry and made use of a prospective collection of urine samples. Additionally, we investigated patients with PBMAH from different centres. Second, by combining state of the art multisteroid analytics by the platform technique gas chromatography-mass spectrometry with systems biology statistical approaches, we succeeded in discerning affected from unaffected individuals as well as in further delineating the various subtypes of Cushing’s syndrome by metabolic cluster analysis. Thus, we were able to reach the main aim of our study: to gain insights into the pathophysiology of steroid metabolism and the specific metabotypes of patients with different subtypes of CS.

Of course, we will continue evaluation of our biomarkers in following studies. Due to the fact that ectopic CS is a very rare condition, patients to be included in this study had not been available.

In regard to statistical limitations, we would like to stress that interpreting results of PCA and the PCs can be difficult. It is often questionable what each PC represents in terms of the original variables. In addition, in this analysis we describe only the first two dimensions explaining about 47% of the total variation, because 3-dimensional plots are difficult to interpret. It is possible that we are losing some details in the remaining dimensions. Metabolites, which are correlated, are placed closely together. Therefore, labels are often overlapping and not easy to read. Overall, PCA in combination with PAM-clustering should only give an overview on the observed variability of the metabolites and the subtypes.

Conclusion and outlook

Using a targeted urinary steroid metabolome analysis by GC-MS offers excellent sensitivity to diagnose CS. It is also capable of differentiating between ACTH-dependent and ACTH-independent CS.

GC-MS based urinary steroid metabotyping presents a valuable powerful diagnostic tool, which opens up avenues in the delineation of this highly complex disorder. It can be used as a complementary test.

Legends and abbreviations

Abbreviation: urine steroid metabolite

- Estrogens

- E1: Estrone

- E2: Estradiol

- E3: Estriol

- Androgen metabolites

- T: Testosterone

- An: 5α-Androstane-3α-ol-17-on (androsterone)

- Et: 5β-Androstane-3α-ol-17-on (etiocholanolone)

- DHEA: 5-Androstene-3β-ol-17-on (dehydroepiandrosterone)

- 16α-OH-DHEA: 5-Androstene-3β,16α-diol-17-one

- A5-3β,17α: 5-Androstene-3β,17α-diol

- A5-3β,17β: 5-Androstene-3β,17β-diol (androstenediol-17β)

- A5T-16a: 5-androstene-3β,16α,17β-triol (androstenetriol-16α)

- 11-OH-AN: 5α-Androstane-3α,11β-diol-17-one (11-hydroxy-androsterone)

- 11-O-AN: 5α-androstane-3α-ol-11,17-dione (11-oxo-androsterone)

- 11-OH-ET: 5β-androstane-3α,11β-diol-17-one (11-hydroxy-etiocholanolone)

- Intermediate and progesterone metabolites

- PD: 5β-Pregnane-3α,20α-diol (pregnanediol)

- PT: 5β-Pregnane-3α,17α,20α-triol (pregnanetriol)

- P5D: 5-Pregnene-3β,20α-diol (pregnenediol)

- P5T-17α: 5-Pregnene-3β,17α,20α-triol (pregnenetriol-17α)

- Po-5β,3α: 5β-Pregnane-3α,17α-diol-20-one (17a-OH-pregnanolone)

- Po-5α,3α: 5α-Pregnane-3α,17α-diol-20-one

- 11-O-PT: 5β-Pregnane-3α,17α,20α-triol-11-one (11-oxo-pregnanetriol)

- THS: 5β-Pregnane-3α,17α,21-triol-20-one (tetrahydro-11-deoxycortisol)

- Glucocorticoid metabolites

- F (cortisol): 4-Pregnene-11β,17α,21-triol-3,20-dione (cortisol)

- THE: 5β-Pregnane-3α,17α,21-triol-11,20-dione

- THF: 5β-Pregnane-3α,11β,17α,21-tetrol-20-one

- allo-THF: 5α-Pregnane-3α,11β,17α,21-tetrol-20-one

- α-Cl: 5β-Pregnane-3α,17α,20α,21-tetrol-11-one (α-Cortolone)

- β-Cl: 5β-Pregnane-3α,17α,20β,21-tetrol-11-one (β-Cortolone)

- α-C: 5β-Pregnane-3α,11β,17α,20α,21-pentol (a-Cortol)

- β-C: 5β-Pregnane-3a,11b,17a,20β,21-pentol (β-Cortol)

- 6β-OH-F: 4-Pregnene-6β,11β,17α,21-tetrol-3,20-dione (6β-hydroxycortisol)

- 20α-DHF: 4-Pregnene-11β,17α,20α,21-tetrol-3-one (20α-dihydrocortisol)

- Aldosterone precursors

- THA: 5β-Pregnane-3α,21-diol-11,20-dione (tetrahydro-11-dehydro-corticosterone)

- THB: 5β-Pregnane-3α,11β,21-triol-20-one (tetrahydro-corticosterone)

- allo-THB: 5α-Pregnane-3α,11β,21-triol-20-one (allo-tetrahydro-corticosterone)

- TH-DOC: 5β-Pregnan-3α,21-diol-20-one (tetrahydro-11-deoxycorticosterone)

Selection of indicators of enzyme defects and enzyme activity ratios (precursor/product)

Relative overall androgen production

Androgene_relativ_1: (An + Et)/(5α-THF + THF + THE)

Androgene_relativ_2: (An + Et + A5-3β,17α + A5-3β,17β + DHEA + 16α-OH-DHEA + A5T-16α)/(5α-THF + THF + THE)

Global 11β-hydroxy-steroiddehydrogenase

HSD_1: (11β-HSD) activity (5α-THF + THF)/THE

HSD_2: THF/THE

HSD_3: cortols/cortolones

11β-hydroxylase activity

bHydroxylase_1: THS/(5α-THF + THF + THE)

bHydroxylase_2: (An + Et)/(11β-OH-An + 11β-OH-Et)

Contributors

Leah T Braun: literature search, figures, study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing–original draft. Andrea Osswald: data collection, writing–review and editing. Stephanie Zopp: data collection, writing–review and editing. German Rubinstein: data collection, writing–review and editing. Frederick Vogel: data collection, writing–review and editing. Anna Riester: data collection, writing–review and editing. Jürgen Honegger: data collection, writing–review and editing. Graeme Eisenhofer: data collection, writing–review and editing, funding acquisition. Georgiana Constantinescu: data collection, writing–review and editing. Timo Deutschbein: data collection, writing–review and editing. Marcus Quinkler: data collection, writing–review and editing. Ulf Elbelt: data collection, writing–review and editing. Heike Künzel: data collection, writing–review and editing. Hanna Nowotny: funding acquisition, writing–review and editing. Nicole Reisch: funding acquisition, writing–review and editing. Michaela Hartmann: data analysis, steroid analysis, resources, methodology, writing–review and editing. Felix Beuschlein: funding acquisition, writing–review and editing. Jörn Pons-Kühnemann: figures, data analysis, methodology, software, supervision, writing–review and editing. Martin Reincke: data collection, study design, data interpretation, funding acquisition, project administration, resources, supervision, writing–review and editing. Stefan Wudy: study design, steroid analysis, data interpretation, data analysis, resources, methodology, supervision, writing–review and editing, literature search. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Leah T Braun and Jörn Pons-Kühnemann verified the underlying data.

Data sharing statement

All urinary steroid data reported in the manuscript will be made available with publication in the following database: Open Data LMU. Data will be shared after approval of a proposal.

Declaration of interests

Several authors received funding as mentioned below. FB has received travel support by Novo Nordisk. Furthermore, he has a patent (PCT/EP2022/053142) for biomarkers for the diagnosis and treatment of endocrine hypertension, and methods of identification thereof. He also participated on an advisory board for Bayer (indication outside of the topic of the manuscript). All the other authors have no conflict of interest to report.

Acknowledgements

This work is part of the German Cushing’s Registry CUSTODES and has been supported by a grant from the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung to M.R. (2012_A103 and 2015_A228). A.R., A.O., G.E., F.B., N.R. and M.R. are supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation, Projektnummer: 314061271-TRR 205) and N.R. also by DFG 325768017 and F.B. by the Clinical Research Priority Program of the University of Zurich for the CRPP HYRENE. L.T.B. and H.F.N. are supported by the Clinician Scientist program RISE, founded by the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung and the Eva-Luise-und-Horst-Köhler-Stiftung (2019_KollegSE.03). The funding sources had no involvement in this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104907.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Wudy S.A., Schuler G., Sanchez-Guijo A., Hartmann M.F. The art of measuring steroids: principles and practice of current hormonal steroid analysis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2018;179:88–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krone N., Hughes B.A., Lavery G.G., Stewart P.M., Arlt W., Shackleton C.H. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) remains a pre-eminent discovery tool in clinical steroid investigations even in the era of fast liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;121(3–5):496–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shackleton C.H. Mass spectrometry in the diagnosis of steroid-related disorders and in hypertension research. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1993;45(1–3):127–140. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(93)90132-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor N.F. Urinary steroid profiling. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1065:259–276. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-616-0_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wudy S.A., Hartmann M.F., Remer T. Sexual dimorphism in cortisol secretion starts after age 10 in healthy children: urinary cortisol metabolite excretion rates during growth. Am J PhysiolEndocrinol Metab. 2007;293(4):E970–E976. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00495.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Remer T., Boye K.R., Hartmann M.F., Wudy S.A. Urinary markers of adrenarche: reference values in healthy subjects, aged 3-18 years. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(4):2015–2021. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Velikanova L.I., Shafigullina Z.R., Vorokhobina N.V., Malevanaya E.V. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis of urinary steroid metabolomics for detection of early signs of adrenal neoplasm malignancy in patients with Cushing's syndrome. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2019;167(5):676–680. doi: 10.1007/s10517-019-04597-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tiosano D., Knopf C., Koren I., et al. Metabolic evidence for impaired 17alpha-hydroxylase activity in a kindred bearing the E305G mutation for isolate 17,20-lyase activity. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;158(3):385–392. doi: 10.1530/EJE-07-0712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kikuchi E., Yanaihara H., Nakashima J., et al. Urinary steroid profile in adrenocortical tumors. Biomed Pharmacother. 2000;54(Suppl 1):194s–197s. doi: 10.1016/s0753-3322(00)80043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arlt W., Biehl M., Taylor A.E., et al. Urine steroid metabolomics as a biomarker tool for detecting malignancy in adrenal tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(12):3775–3784. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Storbeck K.H., Schiffer L., Baranowski E.S., et al. Steroid metabolome analysis in disorders of adrenal steroid biosynthesis and metabolism. Endocr Rev. 2019;40(6):1605–1625. doi: 10.1210/er.2018-00262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vitkin E., Ben-Dor A., Shmoish M., et al. Peer group normalization and urine to blood context in steroid metabolomics: the case of CAH and obesity. Steroids. 2014;88:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamrath C., Hartmann M.F., Pons-Kühnemann J., Wudy S.A. Urinary GC-MS steroid metabotyping in treated children with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Metabolism. 2020;112 doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamrath C., Hartmann M.F., Wudy S.A. Quantitative targeted GC-MS-based urinary steroid metabolome analysis for treatment monitoring of adolescents and young adults with autoimmune primary adrenal insufficiency. Steroids. 2019;150 doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2019.108426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Espiard S., McQueen J., Sherlock M., et al. Improved urinary cortisol metabolome in addison disease: a prospective trial of dual-release hydrocortisone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(3):814–825. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gawlik A., Shmoish M., Hartmann M.F., et al. Steroid metabolomic signature of liver disease in nonsyndromic childhood obesity. Endocr Connect. 2019;8(6):764–771. doi: 10.1530/EC-18-0536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gawlik A.M., Shmoish M., Hartmann M.F., Wudy S.A., Hochberg Z. Steroid metabolomic signature of insulin resistance in childhood obesity. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(2):405–410. doi: 10.2337/dc19-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bancos I., Taylor A.E., Chortis V., et al. Urine steroid metabolomics for the differential diagnosis of adrenal incidentalomas in the EURINE-ACT study: a prospective test validation study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(9):773–781. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30218-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steffensen C., Bak A.M., Rubeck K.Z., Jorgensen J.O. Epidemiology of Cushing's syndrome. Neuroendocrinology. 2010;92(Suppl 1):1–5. doi: 10.1159/000314297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nieman L.K., Biller B.M., Findling J.W., et al. The diagnosis of Cushing's syndrome: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(5):1526–1540. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleseriu M., Auchus R., Bancos I., et al. Consensus on diagnosis and management of Cushing's disease: a guideline update. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9(12):847–875. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00235-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newell-Price J., Bertagna X., Grossman A.B., Nieman L.K. Cushing's syndrome. Lancet. 2006;367(9522):1605–1617. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68699-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stewart P.M., Walker B.R., Holder G., O'Halloran D., Shackleton C.H. 11 beta-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activity in Cushing's syndrome: explaining the mineralocorticoid excess state of the ectopic adrenocorticotropin syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80(12):3617–3620. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.12.8530609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Homoki J., Holl R., Teller W.M. [Urinary steroid profile in Cushing syndrome and in tumors of the adrenal cortex] Klin Wochenschr. 1987;65(15):719–726. doi: 10.1007/BF01736807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kotlowska A., Puzyn T., Sworczak K., Stepnowski P., Szefer P. Metabolomic biomarkers in urine of Cushing's syndrome patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(2) doi: 10.3390/ijms18020294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schoneshofer M., Weber B., Oelkers W., Nahoul K., Mantero F. Urinary excretion rates of 15 free steroids: potential utility in differential diagnosis of Cushing's syndrome. Clin Chem. 1986;32(1 Pt 1):93–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eisenhofer G., Masjkur J., Peitzsch M., et al. Plasma steroid metabolome profiling for diagnosis and subtyping patients with Cushing syndrome. Clin Chem. 2018;64(3):586–596. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2017.282582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masjkur J., Gruber M., Peitzsch M., et al. Plasma steroid profiles in subclinical compared with overt adrenal Cushing syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(10):4331–4340. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-02349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berke K., Constantinescu G., Masjkur J., et al. Plasma steroid profiling in patients with adrenal incidentaloma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(3):e1181–e1192. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heckmann M., Hartmann M.F., Kampschulte B., et al. Assessing cortisol production in preterm infants: do not dispose of the nappies. Pediatr Res. 2005;57(3):412–418. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000153947.51642.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang R., Hartmann M.F., Tiosano D., Wudy S.A. Characterizing the steroidal milieu in amniotic fluid of mid-gestation: a GC-MS study. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2019;193 doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2019.105412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gawlik A., Shmoish M., Hartmann M.F., Malecka-Tendera E., Wudy S.A., Hochberg Z. Steroid metabolomic disease signature of nonsyndromic childhood obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(11):4329–4337. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bolstad B.M., Irizarry R.A., Åstrand M., Speed T.P. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(2):185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elamin M.B., Murad M.H., Mullan R., et al. Accuracy of diagnostic tests for Cushing's syndrome: a systematic review and metaanalyses. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(5):1553–1562. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tezuka Y., Ishii K., Zhao L., et al. ACTH stimulation maximizes the accuracy of peripheral steroid profiling in primary aldosteronism subtyping. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(10):e3969–e3978. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gower D., Makin H. In: Biochemistry of steroid hormones. Markin H.L.J., editor. Blackwell Scientific Publications; Oxford: 1984. pp. 230–292. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahn C.H., Lee C., Shim J., et al. Metabolic changes in serum steroids for diagnosing and subtyping Cushing's syndrome. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2021;210 doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2021.105856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamaji T., Ishibashi M., Sekihara H., Itabashi A., Yanaihara T. Serum dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate in Cushing's syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1984;59(6):1164–1168. doi: 10.1210/jcem-59-6-1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu M.S., Lou Y., Chen H., et al. Performance of DHEAS as a screening test for autonomous cortisol secretion in adrenal incidentalomas: a prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(5):e1789–e1796. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgac072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naamneh Elzenaty R., du Toit T., Flück C.E. Basics of androgen synthesis and action. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2022;36 doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2022.101665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tosi F., Villani M., Garofalo S., et al. Clinical value of serum levels of 11-oxygenated metabolites of testosterone in women with polycystic Ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(5):e2047–e2055. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Auer M.K., Paizoni L., Neuner M., et al. 11-oxygenated androgens and their relation to hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal-axis disturbances in adults with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2021;212 doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2021.105921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Turcu A.F., Nanba A.T., Chomic R., et al. Adrenal-derived 11-oxygenated 19-carbon steroids are the dominant androgens in classic 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016;174(5):601–609. doi: 10.1530/EJE-15-1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pretorius E., Arlt W., Storbeck K.H. A new dawn for androgens: novel lessons from 11-oxygenated C19 steroids. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2017;441:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nowotny H.F., Braun L., Vogel F., et al. 11-oxygenated C19 steroids are the predominant androgens responsible for hyperandrogenemia in Cushing's disease. Eur J Endocrinol. 2022;187(5):663–673. doi: 10.1530/EJE-22-0320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dorfman R.I. In vivo metabolism of neutral steroid hormones. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1954;14(3):318–325. doi: 10.1210/jcem-14-3-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.