Key Points

Question

How did dialysis facilities that serve patients with high social risk perform in the first year of the End-Stage Renal Disease Treatment Choices (ETC) model compared with those serving populations with lower social risk?

Findings

In this observational study of 2191 dialysis facilities, those disproportionately serving marginalized populations as a safety-net facility received lower performance scores and were more likely to be financially penalized, driven primarily by lower use of home dialysis.

Meaning

The ETC model disproportionately penalized dialysis facilities serving patients with higher social risk during the first year of implementation.

Abstract

Importance

The End-Stage Renal Disease Treatment Choices (ETC) model randomly selected 30% of US dialysis facilities to receive financial incentives based on their use of home dialysis, kidney transplant waitlisting, or transplant receipt. Facilities that disproportionately serve populations with high social risk have a lower use of home dialysis and kidney transplant raising concerns that these sites may fare poorly in the payment model.

Objective

To examine first-year ETC model performance scores and financial penalties across dialysis facilities, stratified by their incident patients’ social risk.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A cross-sectional study of 2191 US dialysis facilities that participated in the ETC model from January 1 through December 31, 2021.

Exposure

Composition of incident patient population, characterized by the proportion of patients who were non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, living in a highly disadvantaged neighborhood, uninsured, or covered by Medicaid at dialysis initiation. A facility-level composite social risk score assessed whether each facility was in the highest quintile of having 0, 1, or at least 2 of these characteristics.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Use of home dialysis, waitlisting, or transplant; model performance score; and financial penalization.

Results

Using data from 125 984 incident patients (median age, 65 years [IQR, 54-74]; 41.8% female; 28.6% Black; 11.7% Hispanic), 1071 dialysis facilities (48.9%) had no social risk features, and 491 (22.4%) had 2 or more. In the first year of the ETC model, compared with those with no social risk features, dialysis facilities with 2 or more had lower mean performance scores (3.4 vs 3.6, P = .002) and lower use of home dialysis (14.1% vs 16.0%, P < .001). These facilities had higher receipt of financial penalties (18.5% vs 11.5%, P < .001), more frequently had the highest payment cut of 5% (2.4% vs 0.7%; P = .003), and were less likely to achieve the highest bonus of 4% (0% vs 2.7%; P < .001). Compared with all other facilities, those in the highest quintile of treating uninsured patients or those covered by Medicaid experienced more financial penalties (17.4% vs 12.9%, P = .01) as did those in the highest quintile in the proportion of patients who were Black (18.5% vs 12.6%, P = .001).

Conclusions

In the first year of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ ETC model, dialysis facilities serving higher proportions of patients with social risk features had lower performance scores and experienced markedly higher receipt of financial penalties.

This observational study assesses the first-year of the End-Stage Renal Disease Treatment Choices model performance and the financial penalties sustained by facilities that serve patients with high social risk vs facilities that serve populations with lower social risk.

Introduction

Kidney failure, a life-threatening condition that requires time-intensive dialysis treatments or organ transplants, disproportionately impacts the most socially disadvantaged communities in the US, such as racial and ethnic minority groups and those living in poverty.1 Home dialysis, in which peritoneal or hemodialysis services occur at home rather than during thrice weekly visits to dialysis centers, offers greater independence and flexibility for patients.2 Although dialysis represents a maintenance treatment option, kidney transplant is an optimal treatment for most patients because it offers higher quality of life and improved survival.3

Although as many as 85% of patients with kidney failure may be medically eligible for home dialysis,4 just 13.3% of incident patients in the US initiated treatment with home dialysis in 2020.5 In the same year, the rate of kidney transplants among prevalent patients was 3.8%, and preemptive waitlisting or transplant in incident patients, 8.1%.5 The US ranks below most other high-income nations on these metrics.2,5 Furthermore, decades of evidence have documented pervasive racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in the use of home dialysis4,6,7 and rate of transplant.8 Black patients with kidney failure are 24% less likely to initiate peritoneal dialysis than White patients.4 Racial differences exist at most steps of the process culminating in a transplant including referral, evaluation, waitlisting, and transplant, although the introduction of the 2014 Kidney Allocation System policy produced some downstream progress.9,10

On January 1, 2021, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) implemented the End-Stage Renal Disease Treatment Choices (ETC) model, which randomly assigned approximately 30% of US dialysis facilities and nephrologists to receive financial incentives based on their patients’ use of home dialysis, receipt of kidney transplant, or placement on a transplant waitlist.2 The ETC is among the largest randomized tests of pay-for-performance incentives ever conducted in the US. Two prior evaluations have reported that the ETC model was associated with an increase11 (among all adult incident patients) or no change12 (among incident traditional Medicare beneficiaries ≥66 years) in home dialysis use. No prior study has examined the consequences of the ETC model on equity in kidney failure treatment.

Dialysis facilities that disproportionately serve populations who are non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, uninsured, covered by Medicaid, or living in highly disadvantaged neighborhoods have been shown to have lower use of home dialysis and rates of kidney transplant,13 raising concerns that these sites may fare poorly in the ETC model. Furthermore, dialysis facilities that primarily serve as a social safety net often operate with low margins and with a less robust quality-improvement infrastructure, providing less flexibility to respond to novel payment programs.14,15 However, in the first year of the ETC model, CMS did not consider any measures of social disadvantage in calculating performance. Without additional support or adjusted measurement, dialysis facilities that disproportionately care for marginalized populations may be at risk of increasing financial penalties as the model escalates payment cuts to as much as 10% of Medicare dialysis reimbursement rates by 2026.16

This study assessed first-year ETC model performance and financial penalties among facilities that serve patients with high social risk compared with those serving populations with lower social risk.

Methods

Study Design and Policy Timeline

This study analyzed the CMS-published data on 2021 ETC model performance and payment adjustments, stratified by a facility-level composite social risk score developed using historical data from incident patients.13 Brown University’s institutional review board approved the study. The data reflect performance in calendar year 2021 (January 1-December 31) and payment adjustments implemented in the second half of 2022. (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1)

The ETC model was proposed in July 2019, finalized in September 2020, and implemented on January 1, 2021. The model will run until 2027, during which time CMS will make payment adjustments to all Medicare payments under the End Stage Renal Disease Prospective Payment System based on prior-year model performance.17 In the first 2 years, adjustments range from bonuses of 4% to penalties of 5%16 (eTable 1 in Supplement 1).

Sample

CMS randomly selected 95 of 306 hospital referral regions and required all dialysis facilities and nephrologists located within those regions to participate in the ETC model.17 The agency assesses all model outcomes at the “aggregation group” level, which represents all ETC-assigned facilities with common ownership within the same hospital referral region.18

We linked CMS’ aggregation-level performance data to attributed dialysis facilities using its certification numbers. We excluded any facilities with fewer than 11 incident patients between 2017-2020, to align with inclusion criteria. The final study sample contained 2191 dialysis facilities across 322 aggregation groups. (eFigure 2 in Supplement 1)

Patient Characteristics and Exposure

We quantified social risk among dialysis facilities’ patients using data on the demographic composition of facilities’ incident patients from January 1, 2017, to June 30, 2020.13 Data from incident patients with kidney failure were gathered from the CMS Medical Evidence Form 2728, which collects sociodemographic and clinical information for nearly all patients initiating dialysis treatment. We included all noninstitutionalized incident patients, including those with Medicaid, Medicare Advantage, commercial insurance, and no insurance, to provide a more comprehensive measure of facility case-mix. By contrast, ETC measures of facility performance and subsequent financial adjustment are based only on traditional Medicare patients. Published estimates suggest 58% of prevalent patients have traditional Medicare.5,19 However, inclusion of patients who initiate dialysis with Medicaid or without insurance coverage conveys important sociodemographic information about facilities’ patient populations, finances, and resource capacity.20,21

We then identified facilities in the highest quintile of the proportion of incident patients who were non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, living in a highly disadvantaged neighborhood, or were either uninsured or covered by Medicaid at dialysis initiation. A facility-level composite social risk score was assigned representing those in the highest quintile of 0, 1, or at least 2 of these characteristics.13 To derive neighborhood disadvantage, we geocoded patients’ addresses to census block groups and linked this to publicly available data on the Area Deprivation Index.22,23 Non-Hispanic Black race and Hispanic ethnicity were included as identifiers of socially disadvantaged groups in the US and were proxies for exposure to systemic racism.

Outcome Measures

CMS calculated all outcome measures at the aggregation-group level during the first year of the ETC model. Aside from transplant waitlisting, which is adjusted for age, no other measures were risk-adjusted for clinical or sociodemographic characteristics. In some cases, outcomes were compared with a benchmark year, herein July 1, 2019, through June 30, 2020, to evaluate change in performance over time. (eMethods in Supplement 1)

Modality performance scores are the single, composite performance score (0-6) produced from the home dialysis and transplant proportions measured during the model year. Observed measures are compared with CMS’ established thresholds, and allotted points are based on performance. These are summed together, with a higher weight for home dialysis than for transplant16 (eFigure 3 in Supplement).

Performance payment adjustment is the financial bonus or penalty awarded to aggregation groups based on their modality performance scores, ranges from a 4% bonus to a 5% penalty, and is applied to all Medicare-based reimbursement for dialysis services.

Measurements That Inform the Modality Performance Score

Home dialysis is calculated as the proportion of total attributed beneficiary months using home dialysis plus one-half times the total number of months using in-center self-dialysis.16

Transplant rate is the sum of (1) the transplant waitlist proportion, calculated as observed over expected, adjusted by beneficiary age and benchmark year measures; and (2) living donor transplants, calculated as the proportion of living donor transplant beneficiary months.16

Achieved vs improved refers to the 2 dimensions by which CMS assessed aggregation group performance in home dialysis and transplant. Achieved measures assess performance against thresholds constructed from the benchmark year and observed in nonparticipating dialysis facilities in common geographic areas. Improved measures assess performance against historical self-performance from the benchmark year. For modality performance score calculation, the higher of achievement or improvement is taken forward.16

The study’s unit of analysis was the facility to align with the level at which we assessed social risk. Consistent with the CMS approach in the ETC model, all aggregation-level outcome measures were allocated to each of the groups’ member facilities, such that all facilities in the same aggregation group received the same values (eTable 2 in Supplement 1).

Statistical Analysis

One-year proportions of achieved home dialysis, achieved and improved transplant, performance payment adjustments, and modality performance scores were compared across facilities with a social risk score of 1 or 2 or more compared with those with a social risk score of 0. Furthermore, facilities in the highest-risk quintile were compared with those in other quintiles for each category. Analyses used 2-tailed independent t tests in Stata version 17 (StataCorp) with a significance threshold of P < .05.

In 2022, CMS applied a health equity adjustment to the modality performance score to account for the proportion of Medicare beneficiaries who are dually enrolled in Medicaid or receive low-income subsidies (hereafter referred to as dually insured or low income).16 Specifically, CMS stratifies aggregation groups into those with less than 50% or 50% or more of traditional Medicare beneficiaries who are dually insured or low income. Each stratum will receive separate thresholds against which they are scored to account for sociodemographic case mix.16 Performance in 2021 did not incorporate this adjustment; however, to evaluate its potential influence, we identified aggregation groups in our sample with 50% or more incident patients who were uninsured or covered by Medicaid upon dialysis initiation as a proxy for dually insured or low-income beneficiaries. We then calculated the percentage of facilities that would be eligible for this scoring adjustment, stratified by our composite measure of social risk.

Results

The study population included 2191 dialysis facilities across 322 aggregation groups, representing 787 183 patient-months (eMethods in Supplement 1). Of these, 2061 (94.1%) were for-profit, 2071 (94.5%) were part of a chain organization, 1071 (48.9%) had a social risk score of 0, and 57 (2.6%) were part of an aggregation group that may be eligible for CMS’ health equity adjustment in future model years (Table). Compared with for-profit facilities, not-for-profit facilities have lower average modality performance scores (3.1 vs 3.5, P < .001), had lower achievement home dialysis (12.9% vs 15.3%, P < .001), and were more likely to be penalized (33.4% vs 13.5%, P < .001), including receiving the largest payment cut of 5% (6.2% vs 0.9%, P = .01; eTable 4 in Supplement 1) Transplant use in for-profit facilities were lower than in the quintile with the highest proportion of patients who were Hispanic (achieved: 19.0% vs 20.6%, P = .04; improved: 16.0% vs 17.3%, P = .05).

Table. Measures of Performance and Financial Adjustment for Facilities, by Composite Social Risk Score, for End-Stage Renal Disease Treatment Choices Model Year 1.

| Composite social risk scorea | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | ≥2 | |

| Types of facilities, No. (%) | |||

| Facility count | 1071 (48.9) | 629 (28.7) | 491 (22.4) |

| For-profit | 999 (93.3) | 599 (95.2) | 463 (94.3) |

| Chain | 1009 (94.2) | 599 (95.2) | 463 (94.3) |

| Sole facility in aggregation group | 43 (4.0) | 25 (4.0) | 26 (5.3) |

| Existing home dialysis program | 1032 (96.4) | 609 (96.8) | 469 (95.5) |

| Baseline proportion of home dialysis (2017-2020), mean (95% CI)b | 13.2 (11.7-14.6) | 10.8 (9.1-12.6) | 6.0 (4.6-7.3) |

| P value | .04 | <.001 | |

| Performance summary, mean (95% CI) [P value]c | |||

| Modality performance scored | 3.6 (3.5-3.6) | 3.5 (3.4-3.5) [.04] | 3.4 (3.3-3.5) [.002] |

| Home dialysis achieved, % | 16.0 (15.5-16.4) | 14.7 (14.1-15.3) [<.001] | 14.1 (13.6-14.6) [<.001] |

| Transplant achieved, % | 19.1 (18.6-19.6) | 19.5 (18.8-20.2) | 18.9 (18.1-19.6) |

| Transplant improved, % | 16.0 (15.6-16.4) | 16.4 (15.8-16.9) | 15.8 (15.2-16.4) |

| Financial adjustments to facilities, No. (%) [95% CI] {P value}c | |||

| Penalty | 123 (11.5) [9.6-13.4] | 88 (14.0) [11.3-16.7] {.13} | 91 (18.5) [15.1-22.0] {<.001} |

| Penalty and in an aggregation group with ≥50% uninsured or Medicaid | 0 | 3 (3.4) [0.0-7.3] {.04} | 16 (17.6) [9.6-25.6] {<.001} |

| Bonus | 440 (41.1) [38.1-44.0] | 253 (40.2) [36.4-44.1] | 214 (43.6) [39.2-48.0] |

| 4% Bonus | 29 (2.7) [1.7-3.7] | 10 (1.6) [0.6-2.6] {.14} | 0 {<.001} |

| 5% Cut | 7 (0.7) [0.2-1.1] | 8 (1.3) [0.4-2.1] {.19} | 12 (2.4) [1.1-3.8] {.003} |

| Social risk status among facilities, No. (%)e | |||

| Highest quintile | |||

| Uninsured or Medicaid | 0 | 67 (10.7) | 369 (75.2) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0 | 184 (29.3) | 254 (51.7) |

| Hispanic | 0 | 241 (38.3) | 197 (40.1) |

| Living in a resource-poor neighborhood | 0 | 137 (21.8) | 301 (61.3) |

| Aggregation group in which ≥50% uninsured or Medicaid at initiation | 2 (0.2) | 6 (1.0) | 49 (10.0) |

Composite social risk score represents the number of measures of social risk per facility, for which a facility receives 1 point for being in the highest quintile of social risk for 4 categories identifying patient characteristics; all analyses in this table were conducted on the facility level.

Identified from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Medical Evidence Form 2728, which reflects data from patients with incident kidney failure as they initiate home dialysis, and thus may not capture the entirety of home dialysis utilization data for the facilities measured.

Performance measures were reported at the level of the aggregation group and then assigned to all facilities within the same aggregation group. Two-tailed independent t tests were used to develop P values that reflect comparison to those facilities with a social risk score of 0.

For modality performance scoring, the highest score a facility could receive was 6 and the lowest was 0. Thus, a higher score reflects better model performance.

Measures of social risk were assigned at the facility level based on the characteristics of incident patients at that facility between 2017 and 2020. Social risk characteristics were obtained from CMS Form 2728.

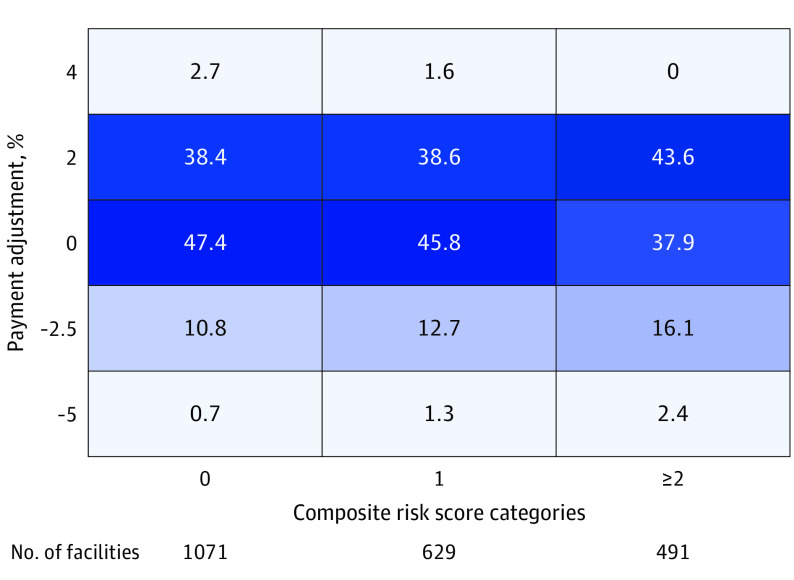

Of the 629 facilities with a social risk score of 1, 288 facilities (45.8%) received no payment adjustment, followed by 243 (38.6%) that received a 2% bonus (Figure 1). Six of these facilities (1.0%) were in aggregation groups that may be eligible for CMS’ health equity adjustment in future model years.

Figure 1. Heat Plot of Column Percentage of Dialysis Facilities, by Financial Adjustment Awarded in ETC Model-Year 1 (2021) and Composite Social Risk Scorea.

Colored cells represent the column percentage of facilities that fall within the cross-section of the categories on each axis, considering both payment adjustment awarded for model-year 1 performance, as well as the composite social risk score. The colors illustrate the range from the highest proportion of facilities presented in the darkest colors and the lowest proportion of facilities in the lightest colors. For instance, 38.4% of the 1071 facilities with a 0 composite social risk score received a 2% payment adjustment.

The characteristics of adult incident dialysis patients from January 2017 through June 2020 were used to stratify aggregation groups into quintiles based on the proportion of those who were non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, uninsured or insured by Medicaid at dialysis initiation (including patients who were eligible for both Medicaid and Medicare), and residents of the most socially disadvantaged neighborhoods, which went on to inform the composite social risk score.

ETC indicates End-Stage Renal Disease Treatment Choices.

aAll analyses conducted at the facility level, with outcome measure (payment adjustment) calculated at the aggregation-group level and applied to all member facilities in the aggregation group, while exposure (composite social risk score) was calculated at the facility level.

Of the 491 facilities with a social risk score of at least 2, a total of 214 facilities (43.6%) received a 2% bonus, followed by 186 (37.9%) that received a neutral adjustment. Forty-nine of these facilities (10%) were in aggregation groups that may be eligible for CMS’ health equity adjustment in future model years.

Compared with the 1071 facilities with a social risk score of 0, facilities with a social risk score of at least 2 had a lower average modality performance scores (3.4 vs 3.6, P = .002) and lower achievement of home dialysis (14.1% vs 16.0%, P < .001). Furthermore, these facilities were more likely to be financially penalized (18.5% vs 11.5%, P < .001), more likely to receive the highest payment cut of 5% (2.4% vs 0.7%; P = .003), and less likely to achieve the highest bonus of 4% (0% vs 2.7%; P < .001). Differences in transplant achievement and improvement were not statistically significant.

Facilities with a social risk score of 1, compared with those with a social risk score of 0, had a lower average modality performance score (3.5 vs 3.6, P = .04) and lower achievement of home dialysis (14.7% vs 16.0%, P < .001). However, differences in financial adjustments between these 2 cohorts were not statistically significant. Furthermore, differences in transplant achievement and improvement were not statistically significant. Aggregation-level results can be found in eTable 3 in Supplement 1 and were broadly consistent with facility-level results.

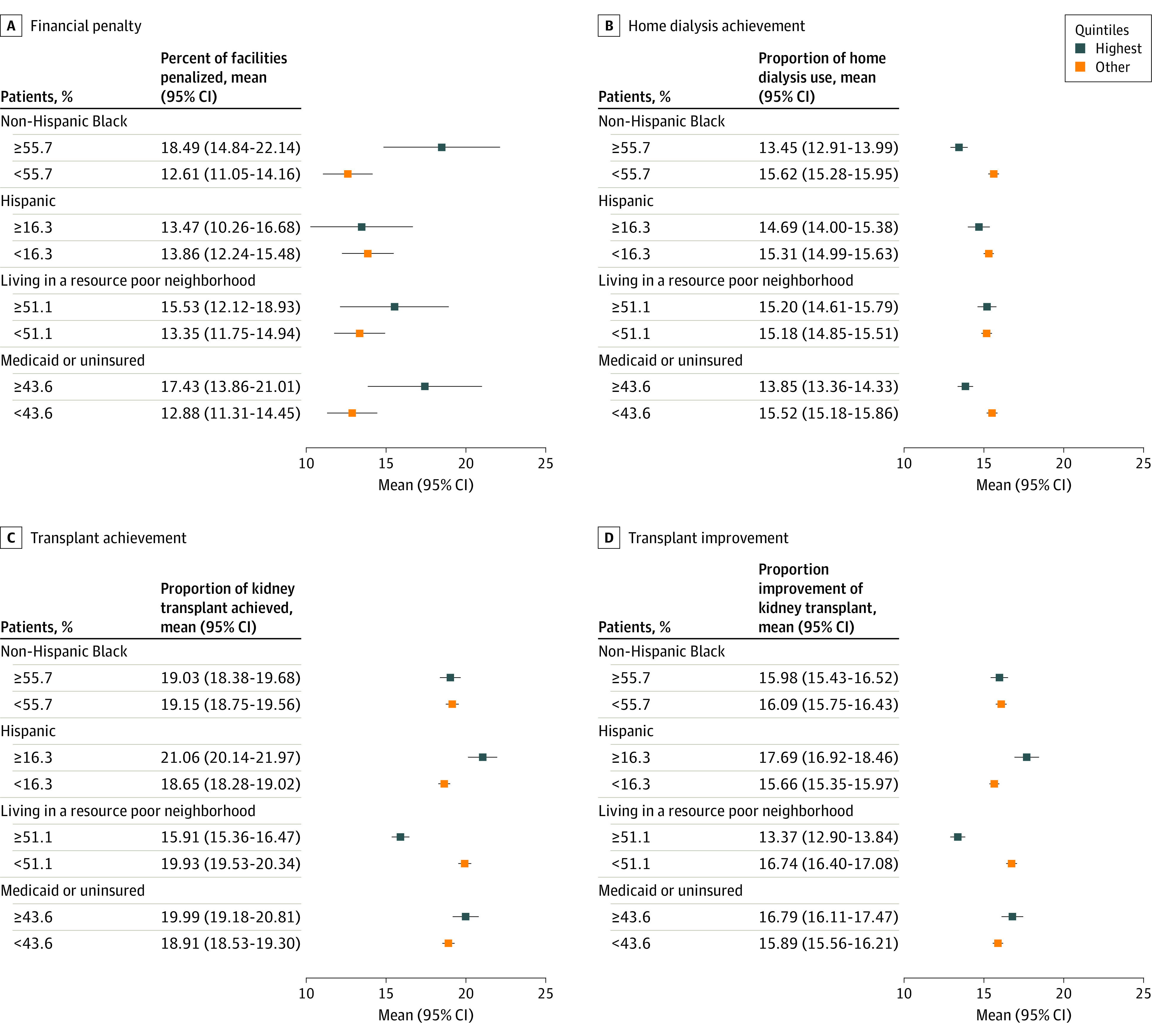

Compared with all other facilities, those in the highest quintile of patients who were uninsured or were covered by Medicaid received more financial penalties (17.4% vs 12.9%, P = .01; Figure 2A) than did those in the highest quintile of the treating of non-Hispanic Black patients (18.5% vs 12.6%, P = .001; Figure 2A). Facilities in the highest quintile of patients who were uninsured or covered by Medicaid had significantly lower achievement of home dialysis (13.9% vs 15.2%, P < .001; Figure 2B) than did those in the highest quintile of non-Hispanic Black patients (13.5% vs 15.6%, P < .001; Figure 2B). Facilities in the highest quintile of patients from disadvantaged neighborhoods demonstrated lower transplant achievement (15.9% vs 19.9%, P < .001; Figure 2C) and improvement (13.4% vs 16.7%, P < .001; Figure 2D), whereas facilities in the highest quintile of treating Hispanic patients demonstrated higher transplant achievement (21.1% vs 18.7%, P < .001; Figure 2C) and improvement (17.7% vs 15.7%, P < .001; Figure 2D).

Figure 2. Comparison of Dialysis Facilities by Social Risk for the End-Stage Renal Disease Treatment Choices Model-Year 1 (2021)a.

Dot and whisker plots compare facilities’ penalty and performance for those in the highest quintile of incident patients with a given dimension of social risk with facilities in the other 4 quintiles. A, Shows the mean proportion of dialysis facilities that received a financial penalty. B, Mean proportions of patients who received home dialysis. C, Mean proportion of patients who received a living-donor kidney transplant or were placed on a transplant waitlist. D, Mean percentage of improvement in transplant or waitlisting in the first model year compared with the benchmark year (July 1, 2019-June 30, 2020). Error bars (whiskers) represent the 95% confidence interval for each estimated value.

See the legend in Figure 1 for quintile stratification calculations.

aAll analyses were conducted at the facility level, with outcome measures (financial penalty, home dialysis, and transplant proportions) calculated at the aggregation-group level and applied to all member facilities in the aggregation group, whereas social risk exposures were calculated at the facility level.

Impact of CMS’ Health Equity Adjustment

We modeled the impact of CMS’ Health Equity Adjustment using the proportion of penalized facilities in an aggregation group with at least 50% of patients who were uninsured or covered by Medicaid at initiation and found that this represented 10% or less of facilities across all levels of social risk (Table and Figure 1). Among the cohort with a social risk score of 1, these facilities make up 3.4% of those penalized; within those that had a social risk score of at least 2, that increases to 17.6%.

Discussion

In the first year of CMS’ ETC model, dialysis facilities serving more patients in the highest quintile of social risk had lower performance scores and received markedly higher financial penalties. The performance differences were driven by lower home dialysis achievement, rather than transplant and transplant waitlisting, and occurred despite CMS’ incentives of rewarding improvement for the use of home dialysis and receipt of kidney transplants in addition to overall achievement. The higher financial penalization was most pronounced for facilities serving patient populations with the highest social risk. Social risk characteristics that were most highly associated with financial penalties and lower home dialysis use were the share of those who were uninsured or covered by Medicaid and were non-Hispanic Black patients. The share of patients from disadvantaged neighborhoods was most associated with lower transplant achievement and improvement. Finally, compared with for-profit facilities, not-for-profit facilities had lower use of home dialysis and were more likely to be financially penalized.

Other studies have demonstrated that pay-for-performance models can have the unintended consequence of disproportionately penalizing and transferring money away from safety-net facilities or clinicians in favor of those that serve populations with lower social risk.4,6,7,14,15,24,25,26,27,28 When payments are assigned without accounting for social risk, program performance may in part reflect socioeconomic case mix rather than the intended measures of quality.15 In kidney failure care, an evaluation of the 2012 ESRD Quality Incentive Program29 demonstrated that dialysis facilities that served high proportions of patients with dual Medicaid-Medicare coverage, living in low-income areas, or who were Black or Hispanic had poorer performance and were more frequently penalized than their counterparts serving lower proportions of such patients. In an effort to address these issues, CMS designed the ETC model to reward both overall achievement as well as improvement in use of home dialysis and kidney waitlisting and receipt of transplants. Our analysis of the first year of the ETC model finds that despite this approach, dialysis facilities serving patients with higher social risk experienced markedly higher receipt of financial penalties.

Extensive research has demonstrated significant disparities in access to optimal kidney failure care across the US.1,4,30,31,32 Structural barriers such as institutional and interpersonal racism, residential segregation, and neighborhood poverty are influential in driving these care gaps.1,33 Furthermore, non-Hispanic Black, uninsured, Medicaid-covered, and socioeconomically disadvantaged patients are highly concentrated within dialysis facilities that have lower use of home dialysis and receipt of transplants. Although the financial margins on Medicare dialysis payments are highly variable (approximately <0.5% on average),29,34 facilities that serve high proportions of patients who are uninsured or are covered by Medicaid likely operate on particularly narrow margins. The magnitude of the ETC model’s 5% to 10% penalty on all Medicare reimbursements, larger than previous quality kidney failure programs,29 may threaten the solvency of these safety-net centers. Their closures would likely have harmful consequences, including extended travel and missed sessions.

Beginning in 2022, CMS applied a new health equity adjustment to the modality performance score, which accounts for the proportion of Medicare beneficiaries per aggregation group who are dually insured or low income.16 Our analysis demonstrates social risk factors like race, ethnicity, and neighborhood disadvantage are associated with model performance yet will not be directly addressed in the new scoring system. Furthermore, this study found that only 57 facilities (2.6%) in the sample may be eligible for the future health equity adjustment, when approximated using a proxy for the stratum cutoff proposed by CMS (>50% dually insured or low income). Only about 10% of the cohort with the highest social risk score (≥2) and 17.6% of those currently penalized met this threshold. These findings suggest that relatively few facilities serving patients with substantial social disadvantage may benefit from this adjustment, given that the 50% or higher threshold is substantially greater than the national proportion of patients with kidney failure who are eligible for both Medicaid and Medicare.5 CMS could consider defining a broader construct of social risk, rather than exclusively focusing on eligibility for Medicaid or low-income subsidies or revising the proposed stratum cutoff to be the median proportion of patients who are dually insured or low income. In 2021, the first year after the 21st Century Cures Act expanded Medicare Advantage enrollment to persons with kidney failure, nearly 1 in 4 dual beneficiaries with kidney failure switched to Medicare Advantage coverage.35 Given this disproportionate shift ,36 smaller proportions of dialysis facilities may qualify for CMS’ health equity scoring adjustment going forward.

Limitations

This study has 4 limitations. First, the use of historical (2017-2020) data on incident patients to characterize facilities’ 2021 social risk may lead to misclassification. However, it is likely that the sociodemographic characteristics of a facility’s population in 2021 are strongly associated with the composition of patients who initiated dialysis in that facility over the prior 3 years. Second, the approach to identifying facilities eligible for the health equity scoring adjustment used the proportion of patients who were uninsured or were covered by Medicaid at initiation, but CMS uses the proportion of prevalent traditional Medicare patients with dual coverage or who are eligible for a low-income subsidy. Third, CMS assesses outcomes and provides data at the aggregation-group level and then attributes performance and applies payment adjustments to all member facilities. Therefore, although the analyses in this study align with CMS’ approach, it was not possible to assess facility-level variations in home dialysis and transplant waitlisting or transplant rates. Fourth, although not-for-profit facilities had received substantially higher financial penalization driven by lower use of home dialysis, the small number of such facilities (n = 130) precludes more extensive analyses. The experience of not-for-profit facilities under the ETC model should be closely monitored in future work.

Conclusions

In this observational study of 2191 dialysis facilities, those serving higher proportions of patients who were non-Hispanic Black or Hispanic, living in a highly disadvantaged neighborhood, or were uninsured or covered by Medicaid at dialysis initiation received lower performance scores and had experienced more financial penalization, driven primarily by lower use of home dialysis. These findings, coupled with the escalation of penalties to as much as 10% in future years, support monitoring the ETC model’s continued impact on dialysis facilities that disproportionately serve patients with social risk factors, as well as its influence on outcomes and disparities in care among patients treated in these sites.

eMethods. Model Timeline

eFigure 1. Visual Representation of the Timeline for CMS’ ETC Model (2019 – 2027)

eFigure 2. Flow Chart of the Study Cohort Construction and Sample Size Limitations

eFigure 3. Rate Calculations Utilized by CMS for ETC Model Scoring

eTable 1. CMS’ Proposed Performance Payment Adjustments by MPS Score Across Model Years

eTable 2. Data Level Across Study Metrics

eTable 3. Measures of Performance and Financial Adjustment for Aggregation Groups, by Composite Social Risk Score, for ETC Model Year 1

eTable 4. Measures of Performance and Financial Adjustment for Facilities, by Composite Social Risk Score and For-Profit Status, for ETC Model Year 1

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Mehrotra R, Soohoo M, Rivara MB, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in use of and outcomes with home dialysis in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(7):2123-2134. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015050472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ESRD treatment choices (ETC) model. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Accessed October 12, 2023. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/esrd-treatment-choices-model

- 3.Patzer RE, Di M, Zhang R, et al. ; Southeastern Kidney Transplant Coalition . Referral and evaluation for kidney transplantation following implementation of the 2014 National Kidney Allocation System. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022;80(6):707-717. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2022.01.423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crews DC, Novick TK. Achieving equity in dialysis care and outcomes: the role of policies. Semin Dial. 2020;33(1):43-51. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Renal Data System 2022. annual data report. Published online 2022. Accessed October 12, 2023. https://usrds-adr.niddk.nih.gov/2022

- 6.Hefele JG, Wang XJ, Lim E. Fewer bonuses, more penalties at skilled nursing facilities serving vulnerable populations. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(7):1127-1131. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheingold SH, Zuckerman R, Shartzer A. Understanding Medicare hospital readmission rates and differing penalties between safety-net and other hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(1):124-131. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohan S, Mutell R, Patzer RE, Holt J, Cohen D, McClellan W. Kidney transplantation and the intensity of poverty in the contiguous United States. Transplantation. 2014;98(6):640-645. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patzer RE, Perryman JP, Schrager JD, et al. The role of race and poverty on steps to kidney transplantation in the southeastern United States. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(2):358-368. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03927.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patzer RE, Amaral S, Wasse H, Volkova N, Kleinbaum D, McClellan WM. Neighborhood poverty and racial disparities in kidney transplant waitlisting. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(6):1333-1340. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008030335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johansen KL, Li S, Liu J, et al. Association of the end-stage renal disease treatment choices payment model with home dialysis use at kidney failure onset from 2016 to 2022. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(2):e230806. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.0806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ji Y, Einav L, Mahoney N, Finkelstein A. Financial incentives to facilities and clinicians treating patients with end-stage kidney disease and use of home dialysis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(10):e223503. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.3503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thorsness R, Wang V, Patzer RE, et al. Association of social risk factors with home dialysis and kidney transplant rates in dialysis facilities. JAMA. 2021;326(22):2323-2325. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.18372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reddy YNV, Tummalapalli SL, Mendu ML. Ensuring the equitable advancement of American kidney health—the need to account for socioeconomic disparities in the ESRD treatment choices model. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32(2):265-267. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020101466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shakir M, Armstrong K, Wasfy JH. Could pay-for-performance worsen health disparities? J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(4):567-569. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4243-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . End-stage renal disease treatment choices (ETC) model, performance payment adjustment report user guide (measurement years 1-2). Published June 2022. Accessed October 12, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/media/document/etc-4i-ppa-report-user-guide-my1-2

- 17.Medicare program; end-stage renal disease prospective payment system, payment for renal dialysis services furnished to individuals with acute kidney injury, end-stage renal disease quality incentive program, and end-stage renal disease treatment choices model. Federal Register. Published 2021. Accessed October 12, 2023. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/11/07/2022-23778/medicare-program-end-stage-renal-disease-prospective-payment-system-payment-for-renal-dialysis [PubMed]

- 18.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Modality performance scores (MPS) and performance payment adjustment (PPA) with performance rate information for aggregation groups, ESRD facilities and managing clinicians. Published 2023. Accessed October 12, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/media/document/etc-my1-detailed-results

- 19.Lin E, Erickson KF. Payer mix among patients receiving dialysis. JAMA. 2020;324(9):900-901. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erickson KF, Shen JI, Zhao B, et al. Safety-net care for maintenance dialysis in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(2):424-433. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2019040417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thorsness R, Trivedi AN. The dialysis safety net: who cares for those without Medicare? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(2):238-240. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2019121276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kind AJH, Buckingham WR. Making neighborhood-disadvantage metrics accessible—the Neighborhood Atlas. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(26):2456-2458. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1802313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.2018. Area Deprivation Index version 3.0. University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health . Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.neighborhoodatlas.medicine.wisc.edu/

- 24.Gilman M, Adams EK, Hockenberry JM, Wilson IB, Milstein AS, Becker ER. California safety-net hospitals likely to be penalized by ACA value, readmission, and meaningful-use programs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(8):1314-1322. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colla CH, Ajayi T, Bitton A. Potential adverse financial implications of the Merit-based Incentive Payment System for Independent and safety net practices. JAMA. 2020;324(10):948-950. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.13093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khullar D, Schpero WL, Bond AM, Qian Y, Casalino LP. Association between patient social risk and physician performance scores in the first year of the Merit-based Incentive Payment System. JAMA. 2020;324(10):975-983. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.13129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnston KJ, Hockenberry JM, Wadhera RK, Joynt Maddox KE. Clinicians with high socially at-risk caseloads received reduced Merit-based Incentive Payment System scores. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(9):1504-1512. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilman M, Hockenberry JM, Adams EK, Milstein AS, Wilson IB, Becker ER. The financial effect of value-based purchasing and the hospital readmissions reduction program on safety-net hospitals in 2014: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6):427-436. doi: 10.7326/M14-2813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qi AC, Butler AM, Joynt Maddox KE. The role of social risk factors in dialysis facility ratings and penalties under a Medicare Quality Incentive Program. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(7):1101-1109. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prakash S, Rodriguez RA, Austin PC, et al. Racial composition of residential areas associates with access to pre-ESRD nephrology care. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(7):1192-1199. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009101008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen JI, Chen L, Vangala S, et al. Socioeconomic factors and racial and ethnic differences in the initiation of home dialysis. Kidney Med. 2020;2(2):105-115. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2019.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arya S, Melanson TA, George EL, et al. Racial and sex disparities in catheter use and dialysis access in the United States Medicare population. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(3):625-636. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2019030274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamoda RE, McPherson LJ, Lipford K, et al. Association of sociocultural factors with initiation of the kidney transplant evaluation process. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(1):190-203. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirth RA, Shahinian VB. Variations in payment for dialysis-implications for policy and practice. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(10):e2239139. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.39139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nguyen KH, Oh EG, Meyers DJ, Kim D, Mehrotra R, Trivedi AN. Medicare Advantage enrollment among beneficiaries with end-stage renal disease in the first year of the 21st Century Cures Act. JAMA. 2023;329(10):810-818. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.1426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meyers DJ, Mor V, Rahman M, Trivedi AN. Growth in Medicare advantage greatest among Black and Hispanic enrollees. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(6):945-950. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Model Timeline

eFigure 1. Visual Representation of the Timeline for CMS’ ETC Model (2019 – 2027)

eFigure 2. Flow Chart of the Study Cohort Construction and Sample Size Limitations

eFigure 3. Rate Calculations Utilized by CMS for ETC Model Scoring

eTable 1. CMS’ Proposed Performance Payment Adjustments by MPS Score Across Model Years

eTable 2. Data Level Across Study Metrics

eTable 3. Measures of Performance and Financial Adjustment for Aggregation Groups, by Composite Social Risk Score, for ETC Model Year 1

eTable 4. Measures of Performance and Financial Adjustment for Facilities, by Composite Social Risk Score and For-Profit Status, for ETC Model Year 1

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement