Abstract

Background:

Older adults with dementia including Alzheimer’s disease may have difficulty communicating their treatment preferences and thus may receive intensive end-of-life (EOL) care that confers limited benefits.

Objective:

This study compared the use of life-sustaining interventions during the last 90 days of life among Medicare beneficiaries with and without dementia.

Methods:

This cohort study utilized population-based national survey data from the 2000-2016 Health and Retirement Study linked with Medicare and Medicaid claims. Our sample included Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries aged 65 years or older deceased between 2000 and 2016. The main outcome was receipt of any life-sustaining interventions during the last 90 days of life, including mechanical ventilation, tracheostomy, tube feeding, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. We used logistic regression, stratified by nursing home use, to examine dementia status (no dementia, non-advanced dementia, advanced dementia) and patient characteristics associated with receiving those interventions.

Results:

Community dwellers with dementia were more likely than those without dementia to receive life-sustaining treatments in their last 90 days of life (advanced dementia: OR = 1.83 [1.42–2.35]; non-advanced dementia: OR = 1.16 [1.01–1.32]). Advance care planning was associated with lower odds of receiving life-sustaining treatments in the community (OR = 0.84 [0.74–0.96]) and in nursing homes (OR = 0.68 [0.53–0.86]). More beneficiaries with advanced dementia received interventions discordant with their EOL treatment preferences.

Conclusions:

Community dwellers with advanced dementia were more likely to receive life-sustaining treatments at the end of life and such treatments may be discordant with their EOL wishes. Enhancing advance care planning and patient-physician communication may improve EOL care quality for persons with dementia.

Keywords: Advance care planning, Alzheimer’s disease, end of life, life-sustaining treatments

INTRODUCTION

Persons living with dementia, particularly those with advanced dementia, may receive end-of-life (EOL) treatments discordant with their preferences, possibly because their cognitive impairments make it difficult for them to express their health care needs [1-5]. Because they may not clearly understand patient needs and preferences, physicians and families might by default opt for intensive, life-sustaining treatments even though many individuals who develop dementia might prefer comfort care [6, 7]. Several studies suggest that advance care planning conveys patient preference and is associated with less use of life-sustaining treatments [5, 8-10].

A second factor contributing to the provision of EOL care inconsistent with preferences is the perception among individuals and their families that dementia, particularly advanced dementia, is not a terminal condition [8, 11]. As a result, families may pursue life-sustaining interventions rather than less burdensome options, as they might in the context of other terminal illnesses.

Interventions such as tube feeding and mechanical ventilation at the end of life can be burdensome and, in some cases, lead to feelings of guilt and stress for families making difficult decisions for their loved ones [12-14]. These interventions can be particularly harmful for persons living with dementia; indeed, these individuals may need less burdensome interventions and more palliative care than those without dementia because persons with dementia may accrue limited benefits and experience more pain, distress, complications, and poorer quality of life from EOL care [8, 15-19]. Dementia clinical practice guidelines recommend avoiding life-prolonging treatments “with no prospect of improving quality of life” [20]. These interventions may also result in high medical expenditures for patients, families, and the health care system [18].

Less intensive care at the end of life is an important treatment goal for many older adults, and delivering preference-concordant care is a key component of high-quality EOL care [14, 21, 22]. Understanding the heterogeneity in EOL wishes and EOL care among persons with dementia can help health care professionals better assess, track, and address unmet health needs of this vulnerable population. Although studies generally recognize that the type and intensity of care older adults receive at the end of life may differ by level of cognitive impairment, results are conflicting [23-27]. For example, some analysis showed that tube feeding rates at the end of life increased with the severity of cognitive impairment [26-28], whereas others found that persons with dementia were less likely than those with normal cognition to receive life-sustaining treatments [24, 25, 29]. Having a written advance directive may reduce aggressive EOL care, but it remains unclear whether individuals with dementia are at a higher risk of receiving life-sustaining interventions that are discordant with their EOL wishes [8, 9, 24, 30,31].

Studies on EOL care in dementia often are restricted to nursing home residents [8, 26, 32-35], but nearly 30% of people with severe dementia remain living in the community until death [24]. Compared to nursing home residents with dementia, community dwellers with cognitive impairment may receive more aggressive EOL care and experience more burdensome and distressing transitions across care settings at the end of life [24, 28, 36]. Therefore, an examination of EOL care of the dementia population should account for the place of residence.

This study compared the likelihood of receiving intensive life-sustaining treatments among Medicare beneficiaries with versus without dementia across the community and nursing home settings. We hypothesized that Medicare beneficiaries with dementia (particularly those with advanced dementia) were more likely to receive life-sustaining treatments at the end of life, compared with beneficiaries without dementia. We hypothesized that life-sustaining treatments were more common among community dwellers with dementia, relative to their nursing home counterparts. We examined whether having advance care planning was associated with lower odds of undergoing life-sustaining treatments. We also investigated whether life-sustaining treatments received at the end of life were discordant with beneficiaries’ recorded EOL wishes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We examined the proportion of Medicare beneficiaries receiving any life-sustaining interventions during the last 90 days of life (defined in “Outcome Measure”), by dementia status and by care setting (defined in “Data and Sample”). We investigated the discordance between receiving these EOL treatments and EOL wishes (defined in “Statistical Analysis”). We utilized logistic regression to assess the association between dementia status and use of life-sustaining treatments, stratified by care setting, and controlled for patient characteristics and advance care planning (defined in “Statistical Analysis”).

Data and sample

This study used survey data from the 2000-2016 Health and Retirement Study (HRS), linked with corresponding Medicare and Medicaid claims. The HRS is a biennial, nationally representative, longitudinal survey of adults over age 50 [37, 38]. The survey includes extensive information on study participants’ demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, cognition, function, and other health-related measures. HRS oversamples Non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics, facilitating the examination of health care utilization among these groups. We used the most recent available HRS-linked fee-for-service Medicare and Medicaid claims data (Medicare, January 1, 2000 through December 31, 2016; Medicaid, January 1, 2000 through December 31, 2012). Medicaid claims information from 2013 to 2016 was not available at the time of our analysis. Claims records include study participants’ enrollment data, clinical diagnoses, and health care utilization. To examine whether life-sustaining treatments received at the end of life were discordant with participants’ EOL wishes, we used survey data from the HRS Exit Interview reported by a proxy respondent within two years after the study participant’s death [39, 40].

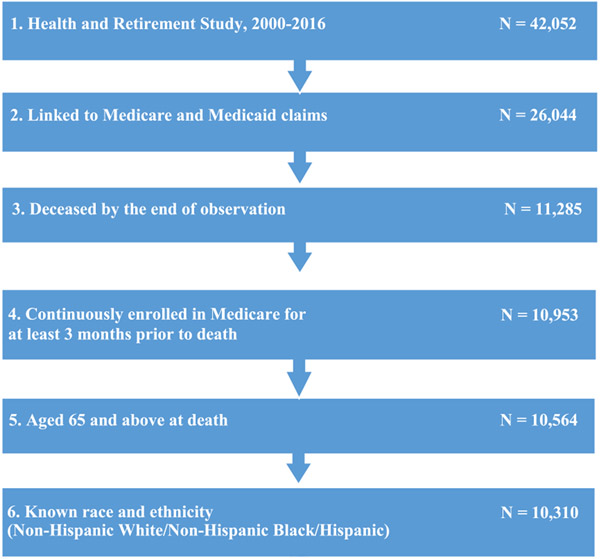

Our sample included HRS respondents aged 65 years and older diagnosed with dementia who died between 2000 and 2016 (Fig. 1). We required all subjects to have continuous enrollment in Medicare fee-for-service for at least 90 days prior to death. We classified respondents as nursing home residents if they: 1) self-reported living in a nursing home according to the HRS survey; 2) died in a nursing home according to the HRS Exit Interview data; or 3) had any nursing home claims in Medicaid files (for dual eligible beneficiaries). We classified all other beneficiaries as “community dwellers.”

Fig. 1.

Sample selection flowchart.

Classifying dementia status

We assigned respondents to one of three categories: advanced dementia, non-advanced dementia, and no dementia. We defined individuals as having dementia based on International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9th or 10th codes in their Medicare claims during the study period (Supplementary Table 1) [41-43]. Of those diagnosed with dementia, we classified beneficiaries as having “advanced dementia” if they had three or more activities of daily living limitations (ADL; difficulty dressing, eating, walking, getting in and out of bed, and using the toilet) from HRS within four years (i.e., two HRS waves) prior to death and any claims-based diagnosis of malnutrition, pressure ulcer, incontinence, or aspiration pneumonia within the last 90 days of life. We classified all other beneficiaries with dementia as having “non-advanced dementia.” This classification is consistent with the approaches used in the literature [15, 22,27,44,45].

Outcome measure

Our outcome measure was the receipt of any life-sustaining interventions during the last 90 days of life, including mechanical ventilation, tracheostomy, tube feeding, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation [22, 24, 26, 27, 29, 46-54]. Previous studies suggest these interventions for older adults with advanced dementia can be burdensome [15, 55, 56]. We used ICD-9 and ICD-10 procedure codes (PCS), Current Procedural Terminology (CPT), and the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes in Medicare claims to identify these interventions (Supplementary Table 2).

Statistical analysis

In unadjusted analysis, we reported the proportion of beneficiaries receiving life-sustaining interventions during the last 90 days of life, by dementia status, across the community and nursing home settings. In adjusted analysis, we conducted a logistic regression, stratified by care setting, to assess whether the receipt of life-sustaining interventions at the end of life differed by dementia status. Because tube feeding is more prevalent among persons with advanced dementia in nursing homes [26], we conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess the use of tube feeding and other life-sustaining treatments separately among community dwellers and nursing home residents. Covariates in the regression analysis included beneficiary age, race and ethnicity, gender, education, Medicare-Medicaid dual eligibility, number of comorbidities, cancer diagnosis, and advance care planning.

The HRS Exit Interview asked whether the study participant had advance care planning, i.e., written instructions specifying the treatment or care they wanted during the final days of life [40]. We identified beneficiaries with written instructions indicating they would prefer to limit care in certain situations, have any treatment withheld, or keep them comfortable and pain free but forego extensive measures to prolong life. Of these beneficiaries, we analyzed the proportion who received mechanical ventilation, tracheostomy, tube feeding, or cardiopulmonary resuscitation during the last 90 days of life. We classified these beneficiaries as receiving life-sustaining treatments that may be discordant with their advance care planning instructions.

Our unadjusted analyses used HRS combined person-level and nursing home resident weights. The Tufts Medical Center/Tufts University Health Sciences Institutional Review Board approved this study via its expedited procedure pursuant to 45 CFR 46.110(b)(4).

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

Compared to decedents without dementia, those with dementia were older and more likely to be female, had lower education levels and more comorbidities, were less likely to have cancer, and were more likely to be dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid (Table 1). Less than half of beneficiaries with dementia had written advance planning specifying EOL treatment preferences (advanced dementia: 41%; non-advanced dementia: 44%). Most beneficiaries with advance care planning indicated they would prefer limited treatment or comfort care at the end of life (97%); this proportion did not differ by dementia status or severity.

Table 1.

Beneficiary characteristics by dementia status

| All (n = 10,310) |

No dementia (n = 5,252) |

Non-advanced dementia (n = 4,109) |

Advanced dementia (n = 949) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group, % | <0.001 | ||||

| 65-74 | 22.2 | 32.5 | 12.1 | 9.6 | |

| 75-84 | 36.1 | 39.1 | 33.5 | 30.7 | |

| 85+ | 41.7 | 28.5 | 54.4 | 59.8 | |

| Female, % | 54.1 | 48.4 | 59.2 | 63.7 | <0.001 |

| Race/Ethnicity, % | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 78.6 | 80.2 | 78.2 | 71.8 | <0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 14.6 | 13.2 | 15.1 | 19.7 | |

| Hispanic | 6.9 | 6.7 | 6.7 | 8.5 | <0.001 |

| Education, % | |||||

| Less than high school | 40.0 | 38.0 | 40.7 | 47.4 | |

| High school | 30.6 | 30.7 | 31.3 | 27.2 | |

| College and above | 29.4 | 31.3 | 28.0 | 25.4 | |

| Nursing home residents, % | 31.5 | 15.9 | 43.5 | 63.7 | <0.001 |

| Medicare-Medicaid Dual eligibility, % | 18.1 | 12.8 | 21.6 | 32.5 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities, mean (SD) | 3.2 (1.5) | 3.1 (1.5) | 3.2 (1.5) | 3.7 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| Cancer diagnosis, % | 29.0 | 37.0 | 22.2 | 13.6 | <0.001 |

| Advance care planning, % | 42.3 | 41.3 | 43.9 | 41.2 | <0.001 |

| Prefer limited or comfort care (n = 4,104), % | 97.4 | 97.4 | 97.2 | 98.2 | 0.54 |

| Limited care (n = 4,054) | 90.7 | 89.9 | 91.3 | 92.7 | 0.11 |

| Any treatment withheld (n = 3,984) | 78.7 | 78.7 | 78.1 | 81.8 | 0.29 |

| Comfortable and pain free but forego extensive measures to prolong life (n = 4,049) | 92.4 | 92.3 | 92.2 | 93.5 | 0.65 |

Results not weighted.

Life-sustaining treatments at the end of life

As detailed in the top panel of Table 2, among community-dwelling beneficiaries, use of any life-sustaining treatments at the end of life was more common among beneficiaries with advanced dementia (28%) than among beneficiaries with non-advanced dementia (21%) and with no dementia (20%). Use of tube feeding was more common among beneficiaries with advanced dementia (16%) than among beneficiaries with non-advanced dementia (9%) or with no dementia (6%). A similar pattern held for ventilation and tracheostomy (dementia, 13–15%; no dementia, 12–14%). But the opposite trend held for resuscitation (Table 2, top panel; dementia, 3–4%; no dementia, 5%).

Table 2.

Proportion of beneficiaries receiving life-sustaining interventions during the last 90 days of life, by dementia status and by care setting1

| Community (n = 22,450,078) |

No dementia (n = 14,226,648) |

Non-advanced dementia (n = 7,142,355) |

Advanced dementia (n = 1,081,075) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any life-sustaining treatments, % | 20.0 | 20.7 | 27.5 | <0.001 |

| Ventilation | 13.5 | 13.9 | 15.0 | <0.001 |

| Tracheostomy | 12.4 | 12.9 | 14.9 | <0.001 |

| Tube feeding2 | 5.7 | 8.8 | 16.0 | <0.001 |

| Resuscitation | 4.7 | 3.6 | 3.0 | <0.001 |

| Nursing home (n = 9,865,433) |

No dementia (n = 2,723,652) |

Non-advanced dementia (n = 5,307,590) |

Advanced dementia (n = 1,834,191) |

p |

| Any life-sustaining treatments, % | 13.2 | 10.9 | 17.9 | <0.001 |

| Ventilation | 7.0 | 4.6 | 6.4 | <0.001 |

| Tracheostomy | 6.6 | 4.3 | 5.3 | <0.001 |

| Tube feeding2 | 7.8 | 6.6 | 13.6 | <0.001 |

| Resuscitation | 2.1 | 1.6 | 1.9 | <0.001 |

Results were weighted by HRS combined personal weights.

Including tube feeding, enteral, and parental nutrition.

As detailed in the bottom panel of Table 2, and like community dwelling beneficiaries, among nursing home beneficiaries, use of any life-sustaining treatments at the end of life was more common among beneficiaries with advanced dementia (18%) than among beneficiaries with non-advanced dementia (11%) and without dementia (13%). Similarly, the use of tube feeding was more prevalent among beneficiaries with advanced dementia (14%) than among the non-dementia group (8%). However, we observed the opposite trend for ventilation and tracheostomy, which were less common among beneficiaries with advanced dementia (5-6%) than among beneficiaries without dementia (7%). Furthermore, unlike community-dwelling residents, use of any life-sustaining treatments at end of life was less common among nursing home residents with non-advanced dementia than among nursing home residents with no dementia. This pattern also held for each of the four individual types of life-sustaining care we analyzed (non-advanced dementia, 2–7%; no dementia, 2–8%).

Community dwellers with dementia were more likely to have any life-sustaining treatments (21–28%) than their nursing home counterparts (11–18%). This difference was statistically significant (p < 0.001).

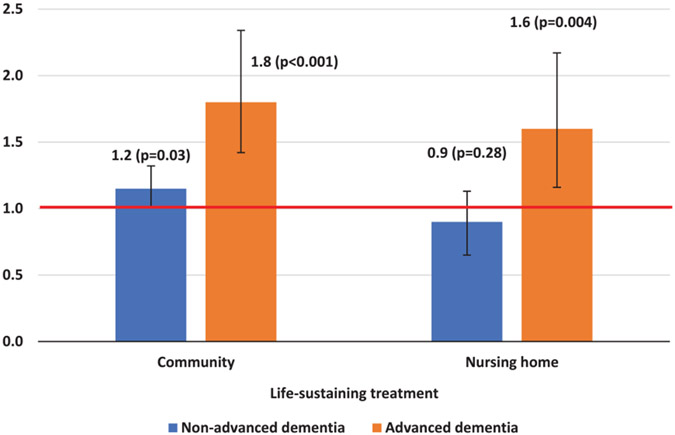

In adjusted analysis, among community-dwelling beneficiaries, those with advanced dementia and those with non-advanced dementia were more likely than those with no dementia to receive life-sustaining interventions at the end of life (advanced dementia: OR= 1.83 [1.42–2.35]; non-advanced dementia: OR= 1.16 [1.01–1.32]) (Fig. 2, left panel). Compared with non-Hispanic White beneficiaries, non-Hispanic Black (OR = 1.49 [1.27–1.76]) and Hispanic beneficiaries (OR = 1.26 [1.01–1.58]) were more likely to receive these interventions at the end of life (Supplementary Table 3). Older age, having cancer, and having advance care planning were associated with lower odds of receiving these life-sustaining interventions. After excluding tube feeding, the association between dementia status and use of life-sustaining treatments remained but was no longer significant (advanced dementia: OR = 1.34 [0.99–1.80]; non-advanced dementia: OR = 1.06 [0.91–1.23]) (Supplementary Table 4). Adjusted analysis showed that for nursing home residents, those with advanced dementia were more likely than those with no dementia to receive life-sustaining treatments at the end of life (OR = 1.59 [1.16–2.17] (Fig. 2, right panel). On the other hand, there was no statistical difference in life-sustaining EOL care between nursing home residents with non-advanced dementia and nursing home residents with no dementia (Fig. 2, right panel; OR = 0.86 [0.65–1.13]). Non-Hispanic Black (OR = 3.41 [2.59–4.48]) and Hispanic (OR = 3.88 [2.64–5.71]) nursing home residents were more likely than non-Hispanic White residents to receive these interventions (Supplementary Table 3). Older age and having advance care planning were associated with lower odds of receiving life-sustaining interventions. For nursing home residents, use of life-sustaining treatments other than tube feeding did not differ for individuals with advanced dementia, compared to those without dementia (OR: 0.95 [0.63–1.44]). Furthermore, those with non-advanced dementia (OR: 0.71 [0.50–1.00]) were less likely to undergo ventilation, tracheostomy, or resuscitation than their counterparts with no dementia (Supplementary Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Adjusted odds ratio of receiving life-sustaining treatments during the last 90 days of life, by dementia status and by care setting. p-values and 95% confidence interval indicated in the figure. Covariates include race and ethnicity, age group, gender, education, number of comorbidities, Medicare-Medicaid dual eligibility, cancer diagnosis, and having advance care planning. Full regression results are shown in Supplementary Table 3.

Discordance with advance care planning instructions

Among community-dwelling participants with advance care planning instructions preferring limited treatment or comfort care at the end of life, more beneficiaries with dementia received life-sustaining treatments (advanced dementia: 19%; non-advanced dementia: 18%; no dementia: 17%; p < 0.001) (Table 3). Although there was less discordance among nursing home residents, a sizable proportion of beneficiaries received life-sustaining treatments even though their advance care planning indicated preferences for limited or comfort care (advanced dementia: 11%; non-advanced dementia: 7%; no dementia: 10%; p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Discordance of life-sustaining interventions and advance care planning instructions, by dementia status and by care setting1

| Community (n = 9,214,015) | Beneficiaries with advance care planning instructions preferring limited treatment or comfort care at the end of life2 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No dementia (n = 5,743,975) |

Non-advanced dementia (n = 3,055,287) |

Advanced dementia (n = 414,753) |

p | |

| Any life-sustaining treatments, % | 17.0 | 18.3 | 19.5 | <0.001 |

| Ventilation | 10.8 | 12.8 | 8.5 | <0.001 |

| Tracheostomy | 10.4 | 11.3 | 7.9 | <0.001 |

| Tube feeding | 5.1 | 7.4 | 13.6 | <0.001 |

| Resuscitation | 3.9 | 3.0 | 1.5 | <0.001 |

| Nursing home (n = 4,846,221) |

No dementia (n = 1,390,230) |

Non-advanced dementia (n = 2,591,443) |

Advanced dementia (n = 864,548) |

p |

| Any life-sustaining treatments, % | 9.6 | 7.0 | 10.8 | <0.001 |

| Ventilation | 5.1 | 2.5 | 3.2 | <0.001 |

| Tracheostomy | 4.5 | 2.1 | 1.9 | <0.001 |

| Tube feeding | 4.5 | 4.1 | 8.5 | <0.001 |

| Resuscitation | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.9 | <0.001 |

Results were weighted by HRS combined personal weights.

Including desire to limit care in certain situations, have any treatment withheld, or keep them comfortable and pain free but forego extensive measures to prolong life.

DISCUSSION

Our findings showed that about one in five community-dwelling beneficiaries with dementia received intensive, life-sustaining treatments during the last 90 days of life. Compared to nursing home residents with dementia, more community dwellers underwent mechanical ventilation, tracheostomy, tube feeding, or cardiopulmonary resuscitation at the end of life. It is possible that community dwellers may not have the information in health care records for medical providers in acute care settings to know their preferences or to be aware of their dementia status; both of these possibilities may lead to unnecessary, life-sustaining treatment [24]. In addition, in response to efforts to enhance the quality of EOL care in such settings, nursing home care providers increasingly regard dementia as a terminal condition. One example is efforts by the Alzheimer’s Association to advocate for more hospice care and less unnecessary aggressive care in its campaign for quality residential care [57, 58]. We also found that beneficiaries with advanced dementia were more likely to receive these treatments in both care settings, an association likely driven by tube feeding. Consistent with previous studies, we found that non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic beneficiaries had higher use of life-sustaining treatments, compared to their non-Hispanic White counterparts [15, 29, 59].

Consistent with prior research [8, 9, 30, 31, 60], our analysis showed that having advance care planning was associated with lower use of life-sustaining treatments. However, over half of beneficiaries with dementia in our sample did not have written instructions specifying EOL treatment preferences. These written instructions matter because they help people have a voice in their EOL care. Although advance care planning is generally underused by Medicare beneficiaries, individuals with dementia may experience poorer quality of care because they do not have these written instructions and become unable to speak for themselves [61]. It is particularly important to have advance care planning to clearly understand patient preferences for EOL care because the prognosis for a patient’s last 6-months of life is highly uncertain, making qualification for Medicare hospice benefits difficult to ascertain. For instance, although 70 percent of newly admitted nursing home residents with dementia in one study died within 6 months, only 1 percent of these residents had a prognosis of death at the time of their admission before dying [62]. Even among individuals with advance care planning documentation indicating that they would prefer limited treatments or comfort care at the end of life, we found that beneficiaries with dementia, especially those with advanced dementia, may be more likely to undergo intensive treatments that are discordant with their EOL wishes. Further, our data suggest more frequent EOL care discordance among community dwellers with dementia than among those residing in nursing homes. These findings highlight the need to improve patient-physician communication about EOL care, advance care planning completion, and compliance with EOL wishes [21, 28], especially among individuals with dementia living in the community.

Our findings confirm earlier work suggesting more frequent use of tube feeding among persons with cognitive impairment [26, 27]. In our population, tube feeding at the end of life was twice as common among beneficiaries with advanced dementia, compared to those without dementia. This finding is consistent with these earlier studies but inconsistent with Nicholas et al. [24], which found less use of life-sustaining treatments among beneficiaries with more severe dementia. Differences in case definitions may explain this inconsistency. Our analysis defined advanced dementia based on the presence of medical complications [22, 27], such as malnutrition and aspiration pneumonia, in addition to ADL limitations (Nicholas et al. characterized severe dementia based on ADL limitations only). Indeed, 91% of beneficiaries in our sample with advanced dementia had a diagnosis of malnutrition or aspiration pneumonia, compared to 35% of beneficiaries without dementia. Because these conditions may make life-sustaining interventions necessary, individuals satisfying our advanced dementia definition may often receive this type of care. Nonetheless, even in these circumstances intensive life-sustaining treatments may confer minimal survival benefits and cause pain and discomfort at the end of life [15, 19].

The health care system must address several challenges to promote preference-concordant EOL care for persons with dementia. Although the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services incentivize physicians to initiate and continue EOL care conversations with patients, the use of advance care planning billing codes remains low [60, 61]. Innovative payment models should require documentation of patient preferences in medical records to measure and improve EOL care quality [63]. Further, persons with dementia and their families may not have a chance to discuss their EOL care preferences before patients lose their ability to make decisions. Miscommunication or a lack of communication can persist among patients, families, and physicians—with each stake-holder expecting someone else to initiate difficult conversations [14, 41, 64]. Persons with dementia from historically underserved communities may be at greatest risk of receiving EOL care uninformed by high-quality conversations regarding preferences [41]. Dementia outreach and education programs should target these populations to improve awareness of and access to EOL care, including advance care planning services [61].

Our study has limitations. First, we had no information about when in the disease process participant advance care planning reached completion. Work in this area would benefit from further qualitative and quantitative research to characterize how EOL treatment preferences may change over time as dementia progresses. Second, this study defined advance care planning based on having written instructions. However, the absence of written instructions does not necessarily imply the complete absence of advance care planning. The definition of advance care planning is rapidly shifting away from “static” documentation and toward a continuous and dynamic communication process for persons living with dementia [65]. Future research should account for the full range of advance care planning activities. Third, we had no HRS-linked Medicare claims data for Medicare Advantage (MA) beneficiaries. MA enrollees account for an increasing share of the Medicare population [66]. Future research should compare EOL care for fee-for-service and MA enrollees with dementia. Fourth, our dataset had too few Asian Americans, Pacific Islander, American Indians, Alaska Natives, or other race/ethnicity participants for us to examine life-sustaining treatments in these populations. Fifth, Medicaid claims for 2013-2016 were not available at the time of this analysis. We expect that the lack of Medicaid claims data for 2013-2016 has a limited impact on our results because we utilized nursing home claims from Medicaid only as supplemental information to classify beneficiary nursing home status. The primary source of information for determining nursing home status came from the HRS, in particular, self-reported nursing home status information and whether the beneficiary died in a nursing home. Sixth, Medicare claims data may fail to identify individuals with non-advanced dementia because of delayed diagnosis and under ascertainment of early-stage dementia [42, 67]. As a result, this study may underestimate the association between use of EOL life-sustaining treatments and non-advanced dementia. On the other hand, this issue likely has a limited impact on assessment of the association between use of life-sustaining treatments and advanced dementia because dementia is more easily detected when the disease has progressed. Finally, our analysis was not designed to track longitudinal trends in life-sustaining treatments.

Our findings highlight potential discordance between life-sustaining treatments for persons with dementia received at the end of life and their advance care planning instructions. Having advance care planning is associated with less intensive EOL care but the completion rate remains low among the population with dementia. Policy interventions should incentivize the completion of advance care planning and encourage compliance with each individual’s EOL preferences. These efforts should prioritize individuals with dementia living in the community and those from historically underserved communities, as they may be more likely to undergo intensive, life-sustaining treatments that confer limited survival benefits.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Rachel Breslau for her assistance with drafting the abstract.

FUNDING

This study is supported by grant No. R01A-G060165 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Pei-Jung Lin reported consulting fees from Eli Lily and Company outside of this work. Dr. Karen Freund reported grants from Tufts Medical Center during the conduct of the study. Dr. Jessica Faul reported participating or consulting several active and recently completed projects funded by NIH. Currently she serves as an associate editor for a journal owned by the Springer Nature publishing company. Drs. Yingying Zhu, Pei-Jung Lin, Natalia Olchanski, Joshua Cohen, and Peter Neumann are affiliated with the Center for the Evaluation of Value and Risk in Health (CEVR), which is funded by multiple parties, including the PhRMA Foundation, Arnold Ventures, and other government, foundation, and pharmaceutical industry sources. CEVR also maintains the Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Registry and SPEC database, which are supported by several dozen organizations, including drug industry and academic and nonprofit foundation sources.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-230692.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

This data has restricted access and is not publicly available.

REFERENCES

- [1].Mitchell SL (2015) Advanced dementia. N Engl J Med 373, 1276–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kumar CS, Kuriakose JR (2013) End-of-life care issues in advanced dementia. Ment Health Fam Med 10, 129–132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Triplett P, Black BS, Phillips H, Richardson Fahrendorf S, Schwartz J, Angelino AF, Anderson D, Rabins PV (2008) Content of advance directives for individuals with advanced dementia. J Aging Health 20, 583–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sachs GA, Shega JW, Cox-Hayley D (2004) Barriers to excellent end-of-life care for patients with dementia. J Gen Intern Med 19, 1057–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sellars M, Chung O, Nolte L, Tong A, Pond D, Fetherstonhaugh D, McInerney F, Sinclair C, Detering KM (2019) Perspectives of people with dementia and carers on advance care planning and end-of-life care: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Palliat Med 33, 274–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, Mack JW, Trice E, Balboni T, Mitchell SL, Jackson VA, Block SD, Maciejewski PK, Prigerson HG (2008) Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 300, 1665–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Poole M, Bamford C, McLellan E, Lee RP, Exley C, Hughes JC, Harrison-Dening K, Robinson L (2018) End-of-life care: A qualitative study comparing the views of people with dementia and family carers. Palliat Med 32, 631–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Roy J, Kabumoto G, Mor V (2003) Clinical and organizational factors associated with feeding tube use among nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. JAMA 290, 73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens J, van der Heide A (2014) The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: A systematic review. Palliat Med 28, 1000–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Livingston G, Lewis-Holmes E, Pitfield C, Manela M, Chan D, Constant E, Jacobs H, Wills G, Carson N, Morris J (2013) Improving the end-of-life for people with dementia living in a care home: An intervention study. Int Psychogeriatr 25, 1849–1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Andrews S, McInerney F, Toye C, Parkinson C-A, Robinson A (2017) Knowledge of dementia: Do family members understand dementia as a terminal condition? Dementia (London) 16, 556–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Fried TR, O’Leary JR (2008) Using the experiences of bereaved caregivers to inform patient- and caregiver-centered advance care planning. J Gen Intern Med 23, 1602–1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Topf L, Robinson CA, Bottorff JL (2013) When a desired home death does not occur: The consequences of broken promises. J Palliat Care 16, 875–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Institute of Medicine (2015) Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. The National Academies Press. 10.17226/18748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sharma RK, Kim H, Gozalo PL, Sullivan DR, Bunker J, Teno JM (2020) The black and white of invasive mechanical ventilation in advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 68, 2106–2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Finucane TE, Christmas C, Travis K (1999) Tube feeding in patients with advanced dementia: A review of the evidence. JAMA 282, 1365–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gillick MR (2000) Rethinking the role of tube feeding in patients with advanced dementia. N Engl J Med 342, 206–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hanchate A, Kronman AC, Young-Xu Y, Ash AS, Emanuel E (2009) Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life costs: Why do minorities cost more than whites? Arch Intern Med 169, 493–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Teno JM, Fisher ES, Hamel MB, Coppola K, Dawson NV (2002) Medical care inconsistent with patients’ treatment goals: Association with 1-year Medicare resource use and survival. J Am Geriatr Soc 50, 496–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gove D, Sparr S, Dos Santos Bernardo AMC, Cosgrave MP, Jansen S, Martensson B, Pointon B, Tudose C, Holmerova I (2010) Recommendations on end-of-life care for people with dementia. J Nutr Health Aging 14, 136–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Glass DP, Wang SE, Minardi PM, Kanter MH (2021) Concordance of end-of-life care with end-of-life wishes in an integrated health care system. JAMA Netw Open 4, e213053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lin P-J, Fillit HM, Cohen JT, Neumann PJ (2013) Potentially avoidable hospitalizations among Medicare beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Alzheimers Dement 9, 30–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Mitchell SL, Black BS, Ersek M, Hanson LC, Miller SC, Sachs GA, Teno JM, Sean Morrison R (2012) Advanced dementia: State of the art and priorities for the next decade. Ann Intern Med 156, 45–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Nicholas LH, Bynum JPW, Iwashyna TJ, Weir DR, Langa KM (2014) Advance directives and nursing home stays associated with less aggressive end-of-life care for patients with severe dementia. Health Affairs 33, 667–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Luth EA, Pan CX, Viola M, Prigerson HG (2021) Dementia and early do-not-resuscitate orders associated with less intensive of end-of-life care: A retrospective cohort study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 38, 1417–1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Teno JM, Mitchell SL, Gozalo PL, Dosa D, Hsu A, Intrator O, Mor V (2010) Hospital characteristics associated with feeding tube placement in nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. JAMA 303, 544–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Braun UK, McCullough LB, Beyth RJ, Wray NP, Kunik ME, Morgan RO (2008) Racial and ethnic differences in the treatment of seriously ill patients: A comparison of African-American, Caucasian and Hispanic Veterans. J Natl Med Assoc 100, 1041–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Perrels AJ, Fleming J, Zhao J, Barclay S, Farquhar M, Buiting HM, Brayne C (2014) Place of death and end-of-life transitions experienced by very old people with differing cognitive status: Retrospective analysis of a prospective population-based cohort aged 85 and over. Palliat Med 28, 220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Luth EA, Manful A, Prigerson HG, Xiang L, Reich A, Semco R, Weissman JS (2022) Associations between dementia diagnosis and end-of-life care utilization. J Am Geriatr Soc 70, 2871–2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Maciejewski PK, Phelps AC, Kacel EL, Balboni TA, Balboni M, Wright AA, Pirl W, Prigerson HG (2012) Religious coping and behavioral disengagement: Opposing influences on advance care planning and receipt of intensive care near death. Psychooncology 21, 714–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Jones T, Luth EA, Lin S-Y, Brody AA (2021) Advance care planning, palliative care, and end-of-life care interventions for racial and ethnic underrepresented groups: A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 62, e248–e260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Gozalo P, Teno JM, Mitchell SL, Skinner J, Bynum J, Tyler D, Mor V (2011) End-of-life transitions among nursing home residents with cognitive issues. N Engl J Med 365, 1212–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kiely DK, Givens JL, Shaffer ML, Teno JM, Mitchell SL (2010) Hospice use and outcomes in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 58, 2284–2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Miller SC, Lima JC, Looze J, Mitchell SL (2012) Dying in U.S. nursing homes with advanced dementia: How does health care use differ for residents with, versus without, end-of-life Medicare skilled nursing facility care? J Palliat Med 15, 43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Temkin-Greener H, Yan D, Wang S, Cai S (2021)Racial disparity in end-of-life hospitalizations among nursing home residents with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 69, 1877–1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Marek KD, Stetzer F, Adams SJ, Popejoy LL, Rantz M (2012) Aging in place versus nursing home care: Comparison of costs to Medicare and Medicaid. Res Gerontol Nurs 5, 123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Sonnega A, Faul JD, Ofstedal MB, Langa KM, Phillips JW, Weir DR (2014) Cohort profile: The Health and Retirement Study (HRS). Int J Epidemiol 43, 576–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Health and Retirement Study, The Health and Retirement Study. https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/about, Accessed on Jan 15, 2023.

- [39].Gotanda H, Walling AM, Reuben DB, Lauzon M, Tsugawa Y (2022) Trends in advance care planning and end-of-life care among persons living with dementia requiring surrogate decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc 70, 1394–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Health and Retirement Study (2018), Health and Retirement Study 2016 Exit: Data Description and Usage. http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/modules/meta/2016/exit/desc/x16dd.pdf. Accessed on June 15, 2023.

- [41].Lin P-J, Zhu Y, Olchanski N, Cohen JT, Neumann PJ, Faul JD, Fillit HM, Freund KM (2022) Racial and ethnic differences in hospice use and hospitalizations at end-of-life among Medicare beneficiaries with dementia. JAMA Netw Open 5, e2216260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Chen Y, Tysinger B, Crimmins E, Zissimopoulos JM (2019) Analysis of dementia in the US population using Medicare claims: Insights from linked survey and administrative claims data. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 5, 197–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Olchanski N, Daly AT, Zhu Y, Breslau R, Cohen JT, Neumann PJ, Faul JD, Fillit HM, Freund KM, Lin PJ (2023) Alzheimer’s disease medication use and adherence patterns by race and ethnicity. Alzheimers Dement 19, 1184–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, Shaffer ML, Jones RN, Prigerson HG, Volicer L, Givens JL, Hamel MB (2009) The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med 361, 1529–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Nicholas LH, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ, Weir DR (2011) Regional variation in the association between advance directives and end-of-life Medicare expenditures. JAMA 306, 1447–1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Barnato AE, Farrell MH, Chang C-CH, Lave JR, Roberts MS, Angus DC (2009) Development and validation of hospital “end-of-life” treatment intensity measures. Med Care 47, 1098–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Wang HE, Peitzman AB, Cassidy LD, Adelson PD, Yealy DM (2004) Out-of-hospital endotracheal intubation and outcome after traumatic brain injury. Ann Emerg Med 44, 439–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Storch B, Bhat A, Zabih R, Eskreis-Winkler J, Fleischut P, Pryor K (2013) 364: A six year analysis of hospital mortality and the interval between intubation and tracheostomy. Crit Care Med 41, A86. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Hsieh M, Auble TE, Yealy DM (2008) Validation of the Acute Heart Failure Index. Ann Emerg Med 51, 37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Mogos MF, Salemi JL, Spooner KK, McFarlin BL, Salihu HM (2016) Differences in mortality between pregnant and nonpregnant women after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Obstet Gynecol 128, 880–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Kuo S, Rhodes RL, Mitchell SL, Mor V, Teno JM (2009) Natural history of feeding-tube use in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 10, 264–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Swetz KM, Peterson SM, Sangaralingham LR, Hurt RT, Dunlay SM, Shah ND, Tilburt JC (2017) Feeding tubes and health care service utilization in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Benefits and limits to a retrospective, multicenter study using big data. Inquiry 54, 46958017732424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Hendrickson E, Corrigan ML (2013) Navigating reimbursement for home parenteral nutrition. Nutr Clin Pract 28, 566–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Beadle BM, Liao K-P, Giordano SH, Garden AS, Hutcheson KA, Lai SY, Guadagnolo BA (2017) Reduced feeding tube duration with intensity-modulated radiation therapy for head and neck cancer: A surveillance, epidemiology, and end results-Medicare analysis: Reduced feeding tube duration with IMRT. Cancer 123, 283–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Schwartz DB, Barrocas A, Wesley JR, Kliger G, Pontes-Arruda A, Márquez HA, James RL, Monturo C, Lysen LK, DiTucci A (2014) Gastrostomy tube placement in patients with advanced dementia or near end of life. Nutr Clin Pract 29, 829–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Volkert D, Chourdakis M, Faxen-Irving G, Frühwald T, Landi F, Suominen MH, Vandewoude M, Wirth R, Schneider SM (2015) ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in dementia. Clin Nutr 34, 1052–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Tilly J, Reed P, Gould E, Fok A (2007) Dementia care practice recommendations for assisted living residences and nursing homes—Phase 3 end-of-life care. Alzheimer’s Association. http://www.alz.org/national/documents/brochure_DCPRphase3.pdf, Accessed on July 10, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- [58].Li Q, Zheng NT, Temkin-Greener H (2013) Quality of end-of-life care of long-term nursing home residents with and without dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 61, 1066–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Connolly A, Sampson EL, Purandare N (2012) End-of-life care for people with dementia from ethnic minority groups: A systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 60, 351–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Gupta A, Jin G, Reich A, Prigerson HG, Ladin K, Kim D, Ashana DC, Cooper Z, Halpern SD, Weissman JS (2020) Association of billed advance care planning with end-of-life care intensity for 2017 Medicare decedents. J Am Geriatr Soc 68, 1947–1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Ladin K, Bronzi OC, Gazarian PK, Perugini JM, Porteny T, Reich AJ, Rodgers PE, Perez S, Weissman JS (2022) Understanding the use of Medicare procedure codes for advance care planning: A national qualitative study: Study examines the use of Medicare procedure codes for advance care planning. Health Affairs 41, 112–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB (2004) Dying with advanced dementia in the nursing home. Arch Intern Med 164,321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Social & Scientific Systems (2016), Examples of Health Care Payment Models Being Used in the Public and Private Sectors. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/private/pdf/208761/ExamplesHealthCarePaymentModels.pdf, Accessed on December 20, 2022.

- [64].Loggers ET, Maciejewski PK, Block S, Prigerson HG, Paulk E, Desanto-Madeya S, Nilsson M, Viswanath K, Wright AA, Balboni TA, Temel J, Stieglitz H (2009) Racial differences in predictors of intensive end-of-life care in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 27, 5559–5564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Piers R, Albers G, Gilissen J, De Lepeleire J, Steyaert J, Van Mechelen W, Steeman E, Dillen L, Vanden Berghe P, Van den Block L (2018) Advance care planning in dementia: Recommendations for healthcare professionals. BMC Palliat Care 17, 88–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Jacobson G, Damico A, Neuman T, Gold M (2017) Medicare Advantage 2017 Spotlight: Enrollment Market Update. MathematicaPolicy Research. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-2017-spotlight-enrollment-market-update/, Last updated on June 06, 2017, Accessed on July 10, 2023.

- [67].Zhu Y, Chen Y, Crimmins EM, Zissimopoulos JM (2020) Sex, race, and age differences in prevalence of dementia in Medicare claims and survey data. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 76, 596–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This data has restricted access and is not publicly available.