Abstract

Background and aims

This study sought to determine the value of patient-derived organoids (PDOs) from esophago-gastric adenocarcinoma (EGC) for response prediction to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (neoCTx).

Methods

Endoscopic biopsies of patients with locally advanced EGC (n = 120) were taken into culture and PDOs expanded. PDOs' response towards the single substances of the FLOT regimen and the combination treatment were correlated to patients' pathological response using tumor regression grading. A classifier based on FLOT response of PDOs was established in an exploratory cohort (n = 13) and subsequently confirmed in an independent validation cohort (n = 13).

Results

EGC PDOs reflected patients' diverse responses to single chemotherapeutics and the combination regimen FLOT. In the exploratory cohort, PDOs response to single 5-FU and FLOT combination treatment correlated with the patients' pathological response (5-FU: Kendall's τ = 0.411, P = 0.001; FLOT: Kendall's τ = 0.694, P = 2.541e-08). For FLOT testing, a high diagnostic precision in receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was reached with an AUCROC of 0.994 (CI 0.980 to 1.000). The discriminative ability of PDO-based FLOT testing allowed the definition of a threshold, which classified in an independent validation cohort FLOT responders from non-responders with high sensitivity (90%), specificity (100%) and accuracy (92%).

Conclusion

In vitro drug testing of EGC PDOs has a high predictive accuracy in classifying patients' histological response to neoadjuvant FLOT treatment. Taking into account the high rate of successful PDO expansion from biopsies, the definition of a threshold that allows treatment stratification paves the way for an interventional trial exploring PDO-guided treatment of EGC patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12943-023-01919-3.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Personalized medicine, Patient-derived organoids, Response prediction

Introduction

Gastric and esophageal cancers are among the most common and deadliest malignancies worldwide, ranking fifth and seventh in cancer incidence as well as fourth and sixth in cancer related death, respectively [1]. Perioperative chemotherapy has substantially improved the median survival in locally advanced gastric adenocarcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the esophago-gastric junction (combined in the following as esophago-gastric adenocarcinoma; EGC) patients to 50 months and a projected 5-year survival of 45% with the FLOT regimen (5-fluorouracil (5-FU), leucovorin, oxaliplatin and docetaxel) [2]. However, 63% of patients have no major pathological response (defined as < 10% vital tumor cells remaining in the resected primary tumor) or do not proceed to surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (neoCTx) [3]. Pathological response to neoCTx has been shown to be a prognostic factor and correlate with survival in gastric cancer [4]. Individualization of neoCTx regimens to improve pathological response has the potential to improve patients' outcome.

Organoids are 3D cell culture models that allow in vitro tissue growth recapitulating many aspects of the original tissue [5]. This method has subsequently been optimized for human cancer tissue resulting in patient-derived organoid (PDO) biobanks from various tissues including EGC [6, 7]. PDOs demonstrated high phenotypic and molecular similarity to their respective tumor of origin, and in vitro treatment resulted in differential responses. These properties place PDOs in the spotlight of personalized treatment approaches [8]. A correlation between PDO and patient response could already be established for EGCs in selected cases [9]. Furthermore, for locally advanced rectal, pancreatic and metastatic colorectal cancer a predictive value of PDOs for therapy response could be demonstrated in prospective co-clinical trials [10].

In order to successfully individualize neoCTx for locally advanced EGC, it is critical to establish biomarkers that predict therapy response. Within the "Outcome prediction of systemic treatment in esophago-gastric carcinoma" (Opposite) study (ClinicalTrials.gov #NCT03429816) aiming at the identification of biomarkers correlating with treatment response, we prospectively established treatment naïve EGC-derived PDOs and investigated their ability to predict the pathological response to neoadjuvant FLOT therapy.

Results

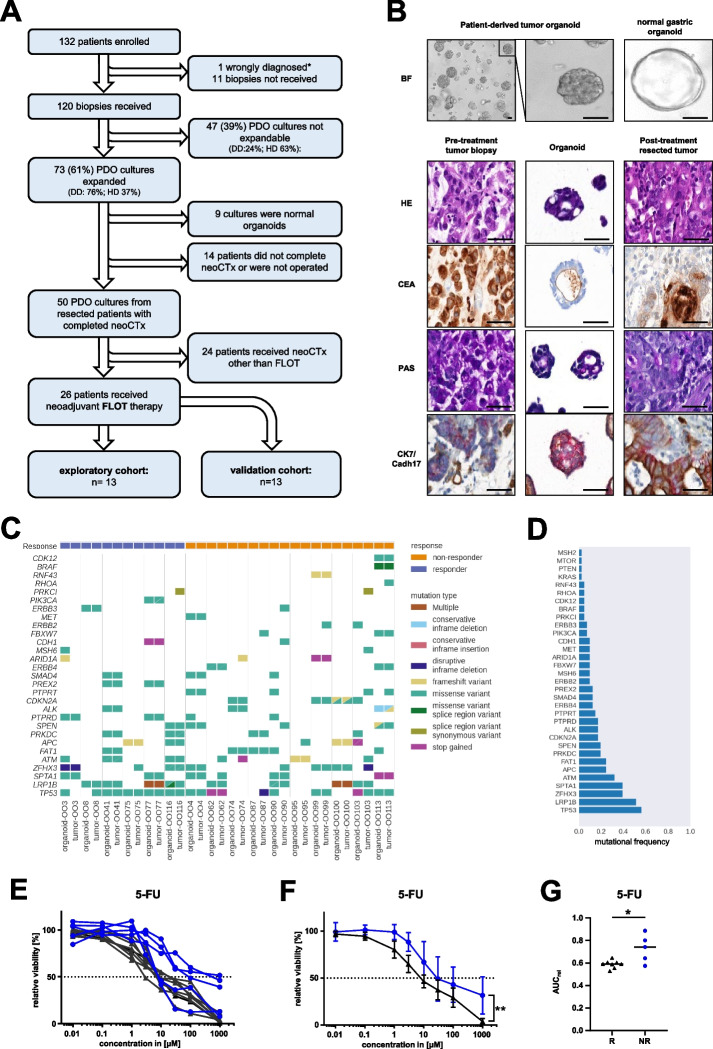

EGC PDOs were generated according to a previously established protocol [7]. Overall, biopsies of 120 patients obtained from two different study sites Dresden (DD), and Heidelberg (HD) were taken into culture and 73 (61%) could be successfully expanded (Fig. 1A). From the successfully expanded PDOs, nine were found to be normal gastric organoids based on morphology, histopathological stainings, or long-term passaging capability. For further 14 PDOs, the corresponding patients did not complete neoCTx or undergo surgery. The pathological response to neoCTx was evaluated according to Becker et al. for the remaining patients (n = 50) [4]. PDOs from 26 patients received neoCTx according to the FLOT regimen and were further analyzed, while the remaining 24 patients split into small cohorts receiving a heterogeneous spectrum of other neoCTx regimens. The chronologically first 13 PDOs constituted the exploratory cohort, whereas the following 13 PDOs were used for independent validation. The analyzed cohort of 26 patients contained tumors from the esophago-gastric junction and the stomach, representing the whole spectrum of patients undergoing neoadjuvant treatment according to current clinical guidelines (Suppl. Table 1 and 2).

Fig. 1.

Trial flow chart and phenotypic, molecular as well as functional characterization of PDO cohort. A Flow chart of the study population. DD/HD: University hospital of Dresden (DD) and Heidelberg (HD). B Brightfield images of a representative EGC organoids line (OO4) and a normal gastric PDO line as a comparison (scale bar: 50 µm). Representative images of the histopathological characterization of primary tumor and corresponding PDO (OO4). The treatment naïve tumor biopsy, thereof derived organoid culture and the post-treatment resection specimen were characterized by hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) staining, periodic acid-Schiff reaction (PAS) as well as cytokeratin7 and cadherin17 (CK7/CADH17) double-staining (scale bar: 50 μm). C Oncoplot depicting prevalent genetic alterations in primary tumors and derived PDO lines. D Bar graph of mutational frequencies of this study. E Dose response curves from cell viability assay of 5-FU treated PDOs 144 h post treatment (average of n = 3 replicates per PDO). F Combined dose response curves from PDOs according to the patients' pathological response of 5-FU with standard deviations (repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) of grouped PDOs, P = 0.001 for 5-FU). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. G Comparison of the relative area under the curve (AUCrel) of PDOs grouped by the patients' pathological response (R: responder; NR: non-responder) for 5-FU (unpaired two-tailed student's t-test, P = 0.010 for 5-FU, *P < 0.05). Blue lines represent pathological non-responders, black lines are pathological responders

The overall successful culture rate for all 120 patients was 61% (Suppl. Figure 1A), with a rate of 76% at the study site with experience in EGC PDO generation (DD) and an improvement for the second study site (HD) over time after an initial implementation phase and subsequently continued optimization of workflows (Suppl. Figure 1A). Of note, the histological subtype according to Lauren influenced the success rate of the PDO generation (Suppl. Table 3). PDOs grew better from the mixed or diffuse subtype than from the intestinal subtype. The first major objective of the study was to secure established PDO lines by cryopreservation. Thus, the median time from receipt of the biopsy to the first FLOT test result can only be assessed retrospectively. The first results from two independent FLOT tests could have been available 20 days after direct processing and 62 days after delivery from the second study site after biopsy collection (Suppl. Figure 1B).

Established PDOs exhibited distinct morphologies differentiating them from the normal single-layered gastric organoids: several PDOs showed a cystic structure with a large lumen, some are characterized by a compact structure and no or small lumina, while others present with a diffuse morphology with poorly cohesive cell growth (Fig. 1B, Suppl. Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry confirmed the preservation of typical gastric cancer markers in PDOs such as cytokeratin 7 (CK7), cadherin 17 (CDH17), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and periodic acid Schiff reaction (PAS) (Fig. 1B). Molecular characterization revealed a high mutational concordance between PDO and primary tumor (Fig. 1C). Additionally, the presence of typical mutations and copy number alterations of EGC in comparable frequency to published data sets indicates the representativeness of the analyzed cohort (Fig. 1D, Suppl. Figure 3, Suppl. Figure 4) [11].

First, PDOs of the exploratory cohort were analyzed with regard to their response to the single FLOT components 5-FU, oxaliplatin and docetaxel using cell viability assays (Fig. 1E-G, Suppl. Figure 5A-F). PDOs showed differential responses to the three chemotherapeutics in dose–response curves (DRCs) (Fig. 1E, Suppl. Figure 5A + D). While some PDOs showed a reduced viability already at low drug concentrations, others only responded at higher concentrations. Furthermore, some PDOs maintained a certain viability plateau at higher doses, e.g. three lines treated with 5-FU still displayed approximately 50% viability at the highest concentration, potentially indicating the presence of a resistant subpopulation. When PDOs were grouped by the patients' pathological regression grade of the resection specimen into responders (Becker 1a/b; n = 8) or non-responders (Becker 2/3; n = 5) [4], no difference in the grouped DRCs could be detected for oxaliplatin and docetaxel (Suppl. Figure 5B + E). In contrast, a significant difference between the two groups was revealed for 5-FU (repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), P = 0.001) (Fig. 1F). In an independent analysis, relative area under the curve (AUCrel) values of the DRCs were calculated and PDOs of pathological responders and non-responders compared using a parametric analysis of non-maximal responses. While AUCrel values of oxaliplatin or docetaxel did not differ between the two groups (Suppl. Figure 5C + F), AUCrel values of 5-FU were again significantly distinct (unpaired two-tailed student's t-test, P = 0.010) (Fig. 1G).

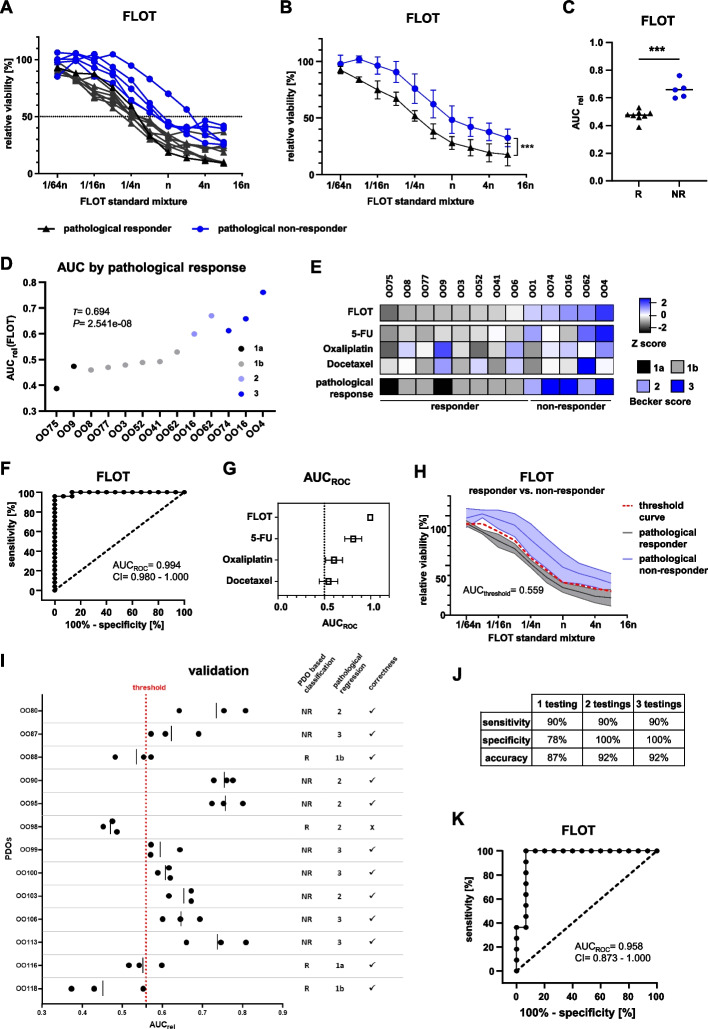

Based on the single drug assays, a combination drug assay for all three drugs plus calcium folinate (FLOT) was established (see Supplementary Material, Material and Methods). PDO treatment with FLOT resulted in diverging DRCs, indicating a varying sensitivity (Fig. 2A). Notably, the PDOs with the lowest sensitivity to FLOT were derived from pathologically non-responding patients.

Fig. 2.

Establishment and validation of an in vitro threshold value to predict in vivo FLOT response. A Dose response curves (DRC) from cell viability assay of PDOs treated with the standard FLOT mixture (n) in varying dilutions analyzed 144 h post treatment (average of n = 3 replicates per PDO). B Combined FLOT-DRC from PDOs according to the patients' pathological response after FLOT neoCTx with standard deviations (repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) of grouped PDOs, P = 4.55e-06). ***P < 0.001 C, Comparison of the relative area under the curve (AUCrel) of PDOs grouped by the patients' pathological response (R: responder; NR: non-responder) (two-tailed student's t-test, P = 3.94e-05). ***P < 0.001 D Dot plot of AUCrel(FLOT) ordered by the patients’ pathological response. Correlation analysis was performed using Kendall ordinal correlation. P < 0.005 was considered statistically significant. E Heatmap of the patients' pathological response and AUCrel derived Z scores from single drug and FLOT combination treatment. Color scale indicates Z score (± 2.5; -2.5: black, 0: white, + 2.5: blue) and scored patients' pathological response according to Becker et al. F ROC curve of the AUCrel(FLOT) generated from single FLOT treatments of PDOs (n = 39, 3 replicates of 13 PDOs). G Summary graph of the AUCrel(ROC) and confidence interval (CI) 95% for FLOT, 5-FU, oxaliplatin and docetaxel. H Dose response curve with CI of FLOT combination treatment grouped according to the patients' pathological response with calculated threshold curve and calculated AUCthreshold(FLOT). Blue lines represent pathological non-responders, black lines are pathological responders. I FLOT combination test results with subsequent classification according to the determined threshold value (AUCthreshold = 0.559) into responding (R) and non-responding (NR) patients. Correctness of classification was later assessed by comparison to patients' pathological response. Red dotted line indicates the threshold established in the exploratory cohort. J Achieved sensitivity, specificity and accuracy depending on the number of performed FLOT testings considered for classification. K ROC curve of the AUCrel(FLOT) generated from the mean of three independent replicates for each PDO of the whole cohort (n = 26)

As already seen in the single drug treatments, the viability of several PDOs continuously dropped only to a certain level of maximum response, with no further decrease at higher FLOT concentrations. Of note, most PDOs that showed this phenomenon were derived from patients with a substantial amount of residual tumor in the resection specimen (Becker 2/3). The comparison of grouped curves showed a significantly higher mean viability of the PDOs from non-responding compared to responding patients (repeated measures ANOVA, P = 4.55e-06) (Fig. 2B). In line with this, the AUCrel of PDOs from responders was significantly lower than the AUCrel of PDOs from non-responders (unpaired student's t-test, P = 3.94e-05, average difference 0.18 AUCrel) (Fig. 2C). Accordingly, there was a strong positive association in ordinal correlation analysis between treatment response of PDOs and patients' pathological regression grade (Kendall's τ = 0.694, P = 2.541e-08) (Fig. 2D). A less strong association was found for single 5-FU (Kendall's τ = 0.411, P = 0.001), while no significant correlation was observed for oxaliplatin and docetaxel (Suppl. Figure 6A-C). A heatmap of Z scores revealed similar patterns between patients' pathological response and the PDOs response to FLOT (Fig. 2E).

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated to determine the diagnostic ability of PDOs to classify patients into pathological responders and non-responders (Fig. 2F, Suppl. Figure 6D-F). For FLOT an AUCROC of 0.994 (CI 0.980 to 1.000) was calculated from individual treatments (3 replicates of 13 PDOs = 39 measurements), demonstrating the high discriminatory ability of the PDO cultures to predict the patients' response to neoadjuvant FLOT treatment. The AUCROC of FLOT thereby outperformed the AUCROC of single substances (Fig. 2G). In order to determine a threshold for in vitro discrimination of responders vs. non-responders, a threshold curve was calculated in-between the confidence interval (CI) of grouped curves of responders and non-responders (Fig. 2H). From this threshold curve the AUCthreshold was calculated to be 0.559. Applying this threshold, all patients from the exploratory cohort were correctly classified (Fig. 2C).

The validity of the established threshold was then evaluated using an independent validation cohort (Fig. 2I). The threshold correctly classified 12 out of 13 patients and achieved a sensitivity of 90%, a specificity of 100% and an accuracy of 92% when PDOs were tested at least twice (Fig. 2J). Three replicates per PDO did not further improve the classification. In addition, the overall good discriminatory ability of the PDO test system could be demonstrated by a ROC analysis of the whole cohort resulting in a high AUCROC of 0.958 (CI: 0.873–1.000) (Fig. 2K). Notably, no other patient or tumor characteristic showed any discriminating value (Suppl. Table 4). Furthermore, no specific mutation could be correlated with the drug response to FLOT (Suppl. Table 5).

An issue frequently observed by several labs during EGC PDO generation that negatively impacts their use is the contamination by normal gastric organoids [12]. In the validation cohort, only one patient (OO98) was incorrectly classified. Detailed histological analysis over time revealed heterogeneity within the PDO culture (Suppl. Figure 7A). In low passages, the dominant PDO phenotype was cystic with a large lumen, resembling normal gastric organoids. Opposed to this, the phenotype in higher passages switched to a diffuse growing morphology, which is in line with primary tumor characteristics (Suppl. Table 2). When subjected to FLOT testing, the higher passage of OO98 was classified as a non-responder, which is the correct classification according to the pathological regression grade (Suppl. Figure 7B). This passage-dependent behavior, only observed in case of OO98, was most likely the result of a contamination of the initially tested early passage with normal gastric organoids.

Discussion

In this prospective co-clinical trial, a strong association of the in vitro PDO response to FLOT and the patient's pathological regression grade after neoadjuvant FLOT could be documented. The limitation of the presented study is the relatively small sample size. Nevertheless, PDO response curves allowed the establishment of an AUC-based threshold, which was subsequently validated in an independent cohort to discriminate with high sensitivity, specificity and accuracy responders from non-responders. Interestingly, 5-FU, as a single drug, associated already well with the patients' pathological response, which is in line with clinical reports [13]. However, the inclusion of all FLOT components is required to achieve the highest predictive value. In case of FLOT non-response, in vivo studies, for example in orthotopic human PDO xenograft models, could serve as a validation platform for novel therapeutic strategies derived from PDO drug screening, which cannot be correlated to the patients’ in vivo response.

Prerequisites for implementing PDO drug testing into clinical decision-making are firstly a high rate of successful culture establishment and secondly a quick expansion of biopsy material to allow drug testing within a few weeks. Within this trial, the overall successful culture rate was 76% at the study site with experience in EGC PDO generation. This demonstrates that generation of PDOs from endoscopic biopsies followed by drug testing is feasible in more than two-thirds of patients in the clinical setting. In addition, the outgrowth rate for biopsies that were shipped increased over time and reached 50% at the end of the recruitment phase. With further improvements of delivery times (> 24 h is detrimental for culture establishment in our hands), multi-centric studies using EGC PDOs seem possible.

For clinical application, the required time to obtain in vitro test results has been a discussion point in PDO-guided therapy [10, 14]. In the current study, the primary focus during the initial expansion of the PDOs was to generate enough material for cryopreservation of the organoid line. Since the material necessary for one FLOT testing corresponds to one-third of what is needed for cryopreservation, it can be assumed that the test results would have been be available within three weeks for biopsies processed on the same campus. The treatment start for most patients in this study was two to three weeks after endoscopy. We expect that the time-to-result could decrease significantly by optimizing the protocol, i.e., miniaturizing the plate format, focusing on immediate testing of the PDOs and optimized sample transport times for external biopsies [15]. Therefore, it can be assumed that the result of FLOT testing could be available at a time that does not delay the start of neoCTx in a clinically relevant way. In addition, systemic therapy could be started with a standard chemotherapy regime and adjusted once the results of the PDO testing are available.

Conclusion

The current study is the first to define and validate a PDO-derived threshold value to classify the patients' pathological response with high accuracy. The defined threshold for FLOT, in combination with future PDO-based alternative drug screens in the case of FLOT non-response allow now the design of interventional organoid-guided clinical trials for EGC patients. These trials will need to clarify the impact of organoids on oncological outcome parameters as well as on patient-reported outcome measures.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The investigative team thanks the patients and their caregivers who participated in this study. We thank the endoscopic and surgical units at each site for biopsy accrual. Furthermore, we thank the Surgical Study Center in Dresden for their support. We also thank the Core Unit for Molecular Tumor Diagnostics (CMTD) of the National Center for Tumor Diseases (NCT) of the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), for providing excellent sequencing and bioinformatics services.

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- AUC

Area under the curve

- AUCrel

Relative area under the curve

- CI

Confidence interval

- DRC

Dose–response curve

- EGC

Esophago-gastric adenocarcinoma

- FLOT

5-Fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin and docetaxel

- neoCTX

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

- PDO

Patient-derived organoid

- ROC

Receiver operator characteristics

- 5-FU

5-Fluorouracil

Author contributions

Conception and design: H.G., J.W., G.M.H., D.E.S. Administrative support: F.H., C.R.B., C.P. Provision of study materials or patients: Ti.Sc., J.F., K.L., A.A., C.W., Th.Sc., B.R., R.K., S.Z., T.W., G.M.H. Collection and assembly of data: Ti.Sc., J.F., K.L., S.D., F.M., F.H., A.A., T.G., C.R.B., C.P., T.S., B.R., R.K., A.S., D.A., G.M.H. Data analysis and interpretation: Ti.Sc., A.K., S.D., F.M., A.H., Th.Se., F.B., T.G., C.W., I.R., D.J., S.Z., T.W., D.A., G.F., G.M.H., D.E.S. Manuscript writing: Ti.Sc., D.E.S. Final approval of manuscript: All authors Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

Funding

This work was funded by a grant from the National Center for Tumor Diseases (NCT) within the Proof-of-Concept program to Daniel E. Stange, Georg M. Haag and Hanno Glimm. DES was funded by the German Cancer Aid (#70113745). Karin Laaber was supported by a stipend from the PhD program of the Helmholtz International Graduate School for Cancer Research (DKFZ Heidelberg). Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Availability of data and materials

Data and analytical methods are available to other researchers upon request to the corresponding author. Patient derived organoid models can be made available upon approval of the local ethics committee.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Human material was collected after providing informed consent within the OPPOSITE trial (ClinicalTrials.gov #NCT03429816) approved by the ethics committee of the TU Dresden (EK 169052018) and University Heidelberg (S-686/2017).

Competing interests

Albrecht Stenzinger

Consulting or Advisory role: Aignostics, Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, BMS, Eli Lilly, Illumina, Incyte, Janssen, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Qlucore, Roche, Seattle Genetics, Takeda, Thermo Fisher.

Research Funding: Bayer, BMS, Chugai, Incyte.

Dirk Jaeger

Consulting or Advisory role: Amgen, BMS, Cure Vac, Definierens, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Genmab A-S, Life Science Inkubator and Vaxxim, Zelluna, OncoOne Research Development.

Gunnar Folprecht

Research Funding: Merck.

Honoraria, Consulting or Advisory Role: Merck, Roche, Amgen, Lilly, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, Bayer, BMS and MSD.

Georg M. Haag

Consulting or Advisory role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, MSD Sharp & Dohme, Lilly, Novartis; Daiichi Sankyo; Servier; MSD Sharp & Dohme.

Research Funding: Nordic Pharma, Taiho Pharmaceutical, MSD Sharp & Dohme.

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Lilly, Servier and MSD Sharp & Dohme.

Karin Laaber

Current Employment: Merck KGaA.

Ronald Koschny

Honorary Lectures: Abbvie, Sanofi-Aventis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Bayer Vital, Norgine.

Daniel E. Stange

Research Funding: Ardeypharm.

No disclosures were reported by the other authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jürgen Weitz, Georg M Haag and Daniel E Stange contributed equally to this work.

Change history

5/13/2024

This article has been returned to typesetting for post-publication update so that its category label can be updated to Research and the sentence “Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.” can be added to the Funding section.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Batran S-E, Homann N, Pauligk C, Goetze TO, Meiler J, Kasper S, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel versus fluorouracil or capecitabine plus cisplatin and epirubicin for locally advanced, resectable gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FLOT4): a ra. Lancet. 2019;393(10184):1948–1957. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32557-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Batran SE, Hofheinz RD, Pauligk C, Kopp HG, Haag GM, Luley KB, et al. Histopathological regression after neoadjuvant docetaxel, oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin versus epirubicin, cisplatin, and fluorouracil or capecitabine in patients with resectable gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FLOT4-AIO. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(12):1697–1708. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30531-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becker K, Mueller JD, Schulmacher C, Ott K, Fink U, Busch R, et al. Histomorphology and grading of regression in gastric carcinoma treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer. 2003;98(7):1521–1530. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sato T, Stange DE, Ferrante M, Vries RGJ, Van Es JH, Van Den Brink S, et al. Long-term expansion of epithelial organoids from human colon, adenoma, adenocarcinoma, and Barrett’s epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(5):1762–72. Available from: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.050 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Bartfeld S, Bayram T, Van De Wetering M, Huch M, Begthel H, Kujala P, et al. In vitro expansion of human gastric epithelial stem cells and their responses to bacterial infection. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(1):126–136.e6. Available from: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.09.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Seidlitz T, Merker SR, Rothe A, Zakrzewski F, Von Neubeck C, Grützmann K, et al. Human gastric cancer modelling using organoids. Gut. 2019;68(2):207–217. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van De Wetering M, Francies HE, Francis JM, Bounova G, Iorio F, Pronk A, et al. Prospective derivation of a living organoid biobank of colorectal cancer patients. Cell. 2015;161(4):933–45. Available from: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Vlachogiannis G, Hedayat S, Vatsiou A, Jamin Y, Fernández-Mateos J, Khan K, et al. Patient-derived organoids model treatment response of metastatic gastrointestinal cancers. Science. 2018;359(6378):920 LP – 926. Available from: http://science.sciencemag.org/content/359/6378/920.abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Wensink GE, Elias SG, Mullenders J, Koopman M, Boj SF, Kranenburg OW, et al. Patient-derived organoids as a predictive biomarker for treatment response in cancer patients. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2021;5(1). Available from: 10.1038/s41698-021-00168-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Bass AJ, Thorsson V, Shmulevich I, Reynolds SM, Miller M, Bernard B, et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513(7517):202–9. Available from: 10.1038/nature13480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Nanki K, Toshimitsu K, Takano A, Fujii M, Shimokawa M, Ohta Y, et al. Divergent routes toward Wnt and R-spondin Niche independency during human gastric carcinogenesis. Cell. 2018;174(4):856–869.e17. Available from: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Culy CR, Clemett D, Wiseman LR. Oxaliplatin: A review of its pharmacological properties and clinical efficacy in metastatic colorectal cancer and its potential in other malignancies. Drugs. 2000;60(4):895–924. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200060040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bose S, Clevers H, Shen X. Promises and challenges of organoid-guided precision medicine. Med. 2021;2(9):1011–26. Available from: 10.1016/j.medj.2021.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Gao M, Harper MM, Lin M, Qasem SA, Patel RA, Mardini SH, et al. Development of a single-cell technique to increase yield and use of gastrointestinal cancer organoids for personalized medicine application. J Am Coll Surg. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data and analytical methods are available to other researchers upon request to the corresponding author. Patient derived organoid models can be made available upon approval of the local ethics committee.