Abstract

Background

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a well-known inflammatory skin disease that is associated with a family history of other atopic diseases. Tobacco smoking has been found to affect AD as well as several other inflammatory skin diseases. In this study, we aimed to investigate this association and to elucidate the link between dose-dependent tobacco exposure and symptom severity.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted on individuals from the general population of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Data were collected using an online questionnaire. All statistical analyses were performed using RStudio, version 1.1.363 (RStudio, PBC, Boston, Massachusetts, United States). Questions about the participants’ age, sex, and occupational status were included. The participants were asked to report their daily handwashing habits and history of atopic diseases. Data on the smoking duration, number of cigarettes smoked per day, and passive exposure were collected.

Results

A total of 510 participants (41.3 %) reported having AD. Smoking was significantly associated with an increased prevalence of AD. The odds of having AD were 1.78 and 2.27 times higher in occasional smokers (odds ratio (OR) = 1.78, p < 0.05) and daily smokers (OR = 2.27, p < 0.001) than in non-smokers. Neither smoking frequency (p = 0.19) nor duration (p = 0.73) was significantly associated with AD prevalence.

Conclusion

Smoking is significantly associated with an increased prevalence of AD. Adults should be discouraged from smoking in order to prevent adult-onset AD. The level of nicotine exposure should be measured objectively in future studies.

Keywords: skin, allergy, dermatitis, cigarettes, eczema

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a well-known inflammatory skin disease that is associated with a family history of other atopic diseases. AD commonly occurs in early childhood, but symptoms often begin in adulthood, resulting in many detrimental consequences, such as work loss [1]. The prevalence of AD in Saudi Arabia has been reported to be 35.9% [2]. Over the past five years, there has been a sudden increase in the number of AD cases in many countries. This number continues to grow [3], reflecting the importance of identifying the risk factors that can lead to AD. One of these risk factors is gene mutations, such as the filaggrin gene mutation [4-6]. Another risk factor is infectious agents, such as Staphylococcus aureus [7,8]. Finally, AD is also associated with exogenous and lifestyle factors, such as wet work, contact with irritant material, and cigarette smoking. All the aforementioned factors have been reported to play a role in AD pathogenesis [8-12].

AD, as well as several other inflammatory skin diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, can be affected by tobacco smoking [13], and the association between the two has been proven by several studies [14-16]. Smoking can not only affect the inflammatory process through cytokine activity and oxidative stress but can also mediate active hand dermatitis and hinder the normal healing process [17,18]. Many studies have reported different AD-related results between active and passive smoking. In the case of active smoking and adult-onset AD, the results are diverse [19]. However, in the case of passive smoking, which is exposure to environmental tobacco smoke during early childhood, it was noted that children were more likely to develop AD later in life [20,21]. With this in mind, the present study aimed to investigate such associations as well as to elucidate the link between dose-dependent tobacco exposure and the severity of AD symptoms.

Materials and methods

Study design

The present cross-sectional study was conducted over a period of four months in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. This study aimed to investigate the association between AD and smoking habits. Data were collected using an online questionnaire. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board Committee of Imam Mohammed Ibn Saud Islamic University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (approval number: HAPO-01-R-001). Consent was obtained from all the participants, and all personal information was kept confidential.

The questionnaire was divided into three sections. The first section collected the respondents' demographic information (age, sex, occupational status, comorbidities, and family history). The second section collected information on smoking habits (tobacco products used, frequency, and duration of smoking). The participants were asked if they were previously diagnosed with AD. The last section collected information regarding AD and its severity, which was assessed using the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) questionnaire. The POEM questionnaire includes seven Likert-scale items. Each item is scored on a scale from 0 (none of the days) to 4 (daily). For each respondent, the total score is calculated by summing the scores of the seven items; the maximum possible score is 28. The following cutoff points were used to grade the severity of AD: 0 to 2, clear or almost clear; 3 to 7, mild AD; 8 to 16, moderate AD; 17 to 24, severe AD; and 25 to 28, very severe AD. The questionnaire was validated through a pilot study that included around 15 participants, which was conducted to identify any question- and language-related issues and the scope for modifying or improving the content.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using RStudio, version 1.1.363 (RStudio, PBC, Boston, Massachusetts, United States). Counts and percentages were used to summarize the distribution of categorical variables. The mean ± standard deviation was used to summarize the distribution of continuous variables. The chi-square test was used to assess the associations between categorical variables. Spearman's correlation coefficient was used to assess the association between continuous or ordinal variables. The Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare POEM scores between the two groups. Cronbach's alpha was used to assess the reliability of the POEM items, with a lower acceptable bound of 0.7. Binary logistic regression was used to assess the association between smoking and the incidence of AD after adjusting for sex, age, marital status, exercise frequency, family history of allergic diseases, and allergic comorbidities (food allergy, allergic rhinitis, and asthma). A p-value lower than 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Results

The study questionnaire was completed by 1235 respondents, of which 690 (55.9%) were male and 545 (44.1%) were female. Respondents aged 18-35 years accounted for the majority of the study sample (n=869, 70.4%), followed by those aged 36-55 years (n=271, 22.9%). More than half of the study participants were non-smokers (n=710, 57.5%), while 345 (27.9%) of them smoked daily. Only 74 (5.99%) and 106 (8.58%) participants were ex-smokers and occasional smokers, respectively. Regarding marital status, 832 (67.4%) respondents were single, and 380 (30.8%) were married. The demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographics of study participants.

| N (%) | |

| Sex: | |

| Female | 545 (44.1%) |

| Male | 690 (55.9%) |

| Age: | |

| < 18 years | 57 (4.62%) |

| 18–35 years | 869 (70.4%) |

| 36–55 years | 271 (22.9%) |

| > 55 years | 38 (3.08%) |

| Smoker: | |

| No | 710 (57.5%) |

| Ex-smoker | 74 (5.99%) |

| Sometimes | 106 (8.58%) |

| Daily | 345 (27.9%) |

| Marital status: | |

| Single | 832 (67.4%) |

| Divorced | 16 (1.30%) |

| Married | 380 (30.8%) |

| Widowed | 7 (0.57%) |

| Employment: | |

| Farmer | 2 (0.16%) |

| Health care provider | 63 (5.10%) |

| Labour job | 10 (0.81%) |

| Office job | 259 (21.0%) |

| Other | 144 (11.7%) |

| Student | 601 (48.7%) |

| Unemployed | 156 (12.6%) |

| Exercise days/week: | |

| Never | 656 (53.1%) |

| 1–2 day | 215 (17.4%) |

| 3–5 days | 286 (23.2%) |

| Daily | 78 (6.32%) |

| Daily frequency of handwashing with soap and water: | |

| < 10 times | 837 (67.8%) |

| 10–20 times | 324 (26.2%) |

| > 20 times | 74 (5.99%) |

| Time taken to wash hands with soap and water: | |

| < 10 s | 480 (38.9%) |

| 10–20 s | 537 (43.5%) |

| 20–40 s | 175 (14.2%) |

| > 40 s | 43 (3.48%) |

| Daily smoking frequency: | |

| < 10 cigarettes | 143 (31.7%) |

| 11–20 cigarettes | 235 (52.1%) |

| 21–40 cigarettes | 64 (14.2%) |

| > 40 cigarettes | 9 (2.0%) |

| Smoking duration: | |

| < 10 years | 231 (51.2%) |

| 10–20 years | 107 (23.7%) |

| > 20 years | 113 (25.1%) |

| Smoked at least 100 cigarettes in a lifetime: | |

| No | 93 (20.6%) |

| Yes | 358 (79.4%) |

Half of the respondents were students (n=601, 48.7%), and a quarter had office jobs (n=259, 21%). Unemployed respondents represented 12.6% (n=156) of the study sample. Half of the respondents did not exercise, while the remaining 17.4% (n=215), 23.2% (n=286), and 6.32% (n=78) exercised one to two times a week, three to five times a week, and daily, respectively. A quarter of the respondents washed their hands 10-20 times/day. Hand washing time varied between respondents, with 38.9% (n=480) and 43.5% (n=537) of the respondents reporting washing their hands for < 10 seconds and 10-20 seconds, respectively. Only 14.2% (n=175) and 3.48% (n=43) reported washing their hands for 20-40 seconds and > 40 seconds, respectively. Half of the respondents smoked 10-20 cigarettes daily, and 31.7% (n=143) smoked < 10 cigarettes. Regarding the smoking duration reported by current smokers (smoked sometimes or daily), half reported that they had smoked for < 10 years and a quarter reported that they had smoked for 10-20 years. More than three-quarters of the respondents (n=358, 79.4%) had smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime.

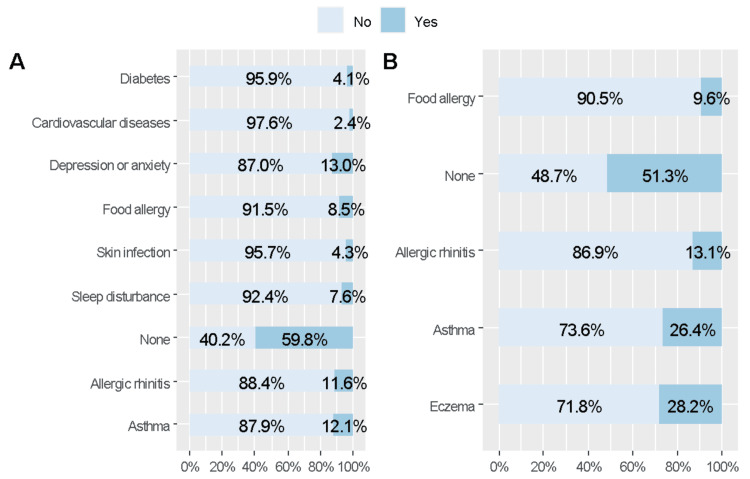

More than half of the respondents did not have comorbidities (59.8%) or did not report any family history of allergic conditions (51.3%). The most commonly reported comorbidities were asthma (12.1%) and allergic rhinitis (11.6%). A quarter of the respondents had a family history of either AD (28.2%) or asthma (26.4%), while 13.1% reported a family history of allergic rhinitis (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Comorbidities and family history of allergic conditions in the included respondents.

(A) Personal comorbidities. (B) Family history

Slightly less than half of the respondents (n=510, 41.3 %) reported being diagnosed with AD. Of the participants diagnosed with AD, 47.6% (n=243) were smokers. Of these, 11.5% (n=28) reported that AD worsened when smoking, 39.5% (n=96) were unsure, and 49.0% (n=119) did not think so. The average POEM score was 9.51 ± 7.46. According to the POEM scores, one-third of the respondents had moderate AD (n=183, 35.9%), 23.9% (n=122) had mild AD, and 21.8% (n=111) had clear AD. The remaining 14.5% (n=74) and 3.92% (n=20) of patients had severe and very severe AD, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2. Prevalence of atopic dermatitis and its severity.

POEM, Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure; AD, Atopic Dermatitis

| N (%) | |

| Been diagnosed with AD: | |

| No | 725 (58.7%) |

| Yes | 510 (41.3%) |

| Smoked before: | |

| No | 267 (52.4%) |

| Yes | 243 (47.6%) |

| AD gets worse when smoking: | |

| Maybe | 96 (39.5%) |

| No | 119 (49.0%) |

| Yes | 28 (11.5%) |

| POEM classification: | |

| Clear | 111 (21.8%) |

| Mild | 122 (23.9%) |

| Moderate | 183 (35.9%) |

| Severe | 74 (14.5%) |

| Very severe | 20 (3.92%) |

| Average POEM score | 9.51 ± 7.46 |

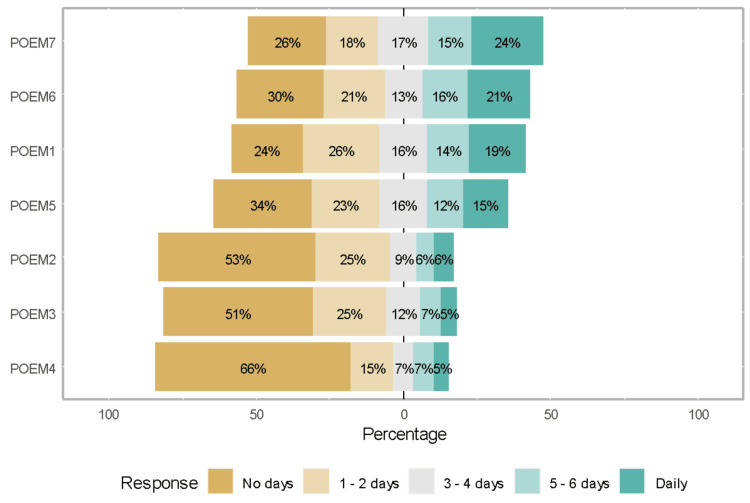

Figure 2 shows the responses to individual POEM questionnaire items. Skin flaking and dryness were the most troublesome items (items 6 and 7), whereas weeping (item 4) and bleeding (item 3) were the least reported. The other items were itching (item 1), sleep disturbance (item 2), and skin cracking (item 5).

Figure 2. Responses to POEM questionnaire items.

POEM, Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure

Table 3 elucidates the association between smoking and AD; the results showed that smoking was significantly associated with the prevalence of AD, with only 37.6% (267) of non-smokers reporting AD compared with 47% (n=162) of daily smokers (p < 0.05). The prevalence of AD among ex-smokers and occasional smokers was similar. Neither smoking frequency (p = 0.19) nor duration (p = 0.73) was significantly associated with AD prevalence. The daily frequency of handwashing was significantly associated with the prevalence of AD (p = 0.002); there was an increasing trend in the prevalence of AD with an increase in the daily frequency of handwashing. The time taken to wash the hands with soap and water was not significantly associated with the prevalence of AD (p = 0.649).

Table 3. Association between smoking and atopic dermatitis.

The data is represented as N (%)

| No, N (%) | Yes, N (%) | Overall p-value | |

| Smoking status: | 0.023 | ||

| No | 443 (62.4%) | 267 (37.6%) | |

| Ex-smoker | 41 (55.4%) | 33 (44.6%) | |

| Sometimes | 58 (54.7%) | 48 (45.3%) | |

| Daily | 183 (53.0%) | 162 (47.0%) | |

| Daily smoking frequency: | 0.190 | ||

| < 10 cigarettes | 73 (51.0%) | 70 (49.0%) | |

| 11–20 Cigarettes | 133 (56.6%) | 102 (43.4%) | |

| 21–40 cigarettes | 33 (51.6%) | 31 (48.4%) | |

| > 40 cigarettes | 2 (22.2%) | 7 (77.8%) | |

| Smoking duration: | 0.730 | ||

| < 10 years | 124 (53.7%) | 107 (46.3%) | |

| 10–20 years | 54 (50.5%) | 53 (49.5%) | |

| > 20 years | 63 (55.8%) | 50 (44.2%) | |

| Daily frequency of handwashing with soap and water: | 0.002 | ||

| < 10 times | 515 (61.5%) | 322 (38.5%) | |

| 10–20 times | 179 (55.2%) | 145 (44.8%) | |

| > 20 times | 31 (41.9%) | 43 (58.1%) | |

| Time taken to wash hands with soap and water: | 0.649 | ||

| < 10 s | 278 (57.9%) | 202 (42.1%) | |

| 10–20 s | 311 (57.9%) | 226 (42.1%) | |

| 20–40 s | 108 (61.7%) | 67 (38.3%) | |

| > 40 s | 28 (65.1%) | 15 (34.9%) | |

The results showed that longer smoking duration was associated with a lower POEM score (r = -0.136, p < 0.005) and lower POEM class (r = -0.145, p < 0.05). None of the remaining variables were significantly associated with the severity of AD (Table 4).

Table 4. Association between atopic dermatitis severity and smoking.

POEM, Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure; AD, Atopic Dermatitis

The data is represented as p-value

*p < 0.05

| Smoker | Smoking duration | Smoking frequency | Hand washing frequency | Hand washing duration | |

| POEM | -0.061 | -0.136* | 0.042 | 0.111 | -0.043 |

| POEM class | -0.059 | -0.145* | 0.029 | 0.095 | -0.071 |

Table 5 presents the results of the binary logistic regression analysis that was used to assess whether smoking was significantly associated with the incidence of AD after adjustments for sociodemographic characteristics. The results showed that the association between smoking and AD remained significant after adjustments for age, sex, and marital status. The odds of having AD were 2.09 times higher in ex-smokers than in non-smokers (odds ratio (OR) = 2.09, p < 0.05). The odds of having AD were 1.78 and 2.27 times higher in occasional smokers (OR = 1.78, p < 0.05) and daily smokers (OR = 2.27, p < 0.001) than in non-smokers. A family history of allergic conditions was associated with higher odds of developing AD (OR = 3.3, p < 0.001). The odds of developing AD were 1.61 times and 3.4 times higher in respondents who suffered from allergic rhinitis (OR = 1.61, p < 0.05) and food allergy (OR = 3.4, p < 0.001) than in respondents who did not. The odds of developing AD were lower in males than in females (OR = 0.56, p < 0.001). None of the remaining factors were significantly associated with the incidence of AD.

Table 5. Binary logistic regression analysis for factors associated with atopic dermatitis.

| Predictors | Odds ratios | Confidence interval | p-value |

| (Intercept) | 1.17 | 0.61–2.24 | 0.633 |

| Sex: Male vs. Female | 0.56 | 0.40–0.77 | < 0.001 |

| Age: < 18 years | Ref | ||

| Age: 18–35 years | 0.96 | 0.52–1.81 | 0.906 |

| Age: 36–55 years | 1.20 | 0.57–2.56 | 0.624 |

| Age: > 55 years | 0.56 | 0.20–1.53 | 0.260 |

| Smoker: Non-smoker | Ref | ||

| Smoker: Ex-smoker | 2.09 | 1.19–3.67 | 0.010 |

| Smoker: Sometimes | 1.78 | 1.11–2.84 | 0.016 |

| Smoker: Daily | 2.27 | 1.59–3.25 | < 0.001 |

| Marital status: Single | Ref | ||

| Marital status: Divorced | 0.59 | 0.17–1.79 | 0.369 |

| Marital status: Married | 1.24 | 0.83–1.83 | 0.288 |

| Marital status: Widowed | 0.44 | 0.06–2.34 | 0.359 |

| Exercise | 0.94 | 0.83–1.07 | 0.330 |

| Family history: Yes vs. No | 3.3 | 2.56–4.35 | < 0.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Asthma: Yes vs. No | 0.82 | 0.55–1.21 | 0.313 |

| Allergic rhinitis: Yes vs. No | 1.61 | 1.08–2.41 | 0.019 |

| Food allergy: Yes vs. No | 3.40 | 2.15–5.50 | < 0.001 |

Discussion

In concordance with previous studies, this study revealed a remarkable association between smoking and AD [17-27]. In previous studies, this relationship appeared to be significant whether it was subjectively reported or objectively measured [27]. In our study, the prevalence of AD among 1235 respondents from the general population was 41.3% (n=510), of whom 47% (n=162) reported smoking daily. A significant association between smoking and AD prevalence was also detected among ex-smokers and occasional smokers. Similarly, a meta-analysis of observational studies revealed a high prevalence of AD and smoking in both adults and children [28]. Furthermore, a systematic review was performed on 20 studies found in the PubMed database, which assessed the relationship between tobacco smoking and AD [29]. Among these studies, eight included population-based surveys and scientific investigations (seven were cross-sectional and one was a cohort study), and four found a positive correlation between smoking and AD. However, no association was found in the remaining four studies. On the other hand, a study published in the British Journal of Dermatology included corresponding controls and three occupational cohorts and concluded that a smaller number of AD cases was reported among smokers, while a larger number of cases was reported among non-smokers (437 and 1294 participants, respectively out of 13 452) [30].

In the present study, higher consumption of tobacco did not affect the prevalence of AD, as neither smoking frequency (p = 0.19) nor duration (p = 0.73) was significantly associated with the prevalence of AD. By contrast, an American study, which included a sample of 25,428 individuals, investigated the dose-dependent relationship between AD and nicotine exposure and reported higher odds of having active AD and, consequently, significantly increased AD prevalence among individuals consuming larger amounts of tobacco [17].

The severity of AD was measured by integrating the POEM score into the questionnaire in order to perform an accurate assessment and to avoid subjective bias; the average score obtained was 9.51 ± 7.4. Additionally, the questionnaire categorized the participants, who reported having AD, into five subgroups: very severe, severe, moderate, mild, and clear AD groups; this revealed that the moderate AD group accounted for one-third of the study population. Besides, the correlation between smoking duration and frequency and AD severity was assessed using the Spearman method with listwise deletion, which showed that a lower POEM score was associated with longer smoking duration (r = -0.136, p < 0.005) and lower POEM class (r = -0.145, p < 0.05). However, a Danish study analyzed data from a private dermatology practice in order to assess the severity of AD in 522 consecutive patients; the results revealed no significant correlation in 224 current smoking patients based on a severity scoring system with scores ranging from 0 to 3 [27]. This earlier study included multiple parameters, such as erythema, vesicles, scaling, pruritus, area, and fissures.

To the best of our knowledge, most of the studies that evaluated the association between tobacco smoking and hand AD were conducted in Europe and the United States. This was the first primary study on this topic conducted in Saudi Arabia. The strength of this study was that a validated method, involving the POEM questionnaire, was used to estimate AD severity based on self-reported surveys. However, this study had a few limitations. First, the data were collected using an online questionnaire. Second, the study sample was from the general population and was not focused on patients with AD, which can narrow the scope of our findings. Third, a self-reported survey is not sufficient for assessing the severity of AD and the effects of nicotine exposure; this can be addressed by including more reliable measured variables for evaluating the relationship between the serum nicotine concentration and the severity of AD symptoms.

Conclusions

The results of the present study reveal that tobacco smoking is significantly associated with the presence of AD; however, this association was not detected in the case of smoking frequency or duration. It is important to consider smoking cessation for the prevention and management of AD, as well as while designing multiple educational programs and community campaigns regarding the various factors that affect AD. Future studies with objective assessments of tobacco exposure and AD are needed to address this dose-dependent association further.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: Faris H. Binyousef, Rahaf Almutairi, Basma A. Alturki, Atheer G. Al-mutairi, Danah Alrajhi, Fajer Alzamil

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Faris H. Binyousef, Rahaf Almutairi, Basma A. Alturki, Atheer G. Al-mutairi, Danah Alrajhi, Fajer Alzamil

Drafting of the manuscript: Faris H. Binyousef, Rahaf Almutairi, Basma A. Alturki, Atheer G. Al-mutairi, Danah Alrajhi, Fajer Alzamil

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Faris H. Binyousef, Rahaf Almutairi, Basma A. Alturki, Atheer G. Al-mutairi, Danah Alrajhi, Fajer Alzamil

Supervision: Fajer Alzamil

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study. Institutional Review Board Committee of Imam Mohammed Ibn Saud Islamic University issued approval HAPO-01-R-001

Animal Ethics

Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

References

- 1.Occupational skin diseases. Diepgen TL, Kanerva L. https://www.jle.com/fr/revues/ejd/e-docs/occupational_skin_diseases_268569/article.phtml. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:324–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pattern of skin diseases in Eastern Saudi Arabia. Alakloby OM. https://smj.org.sa/content/26/10/1607. Saudi Med J. 2005;26:1607–1610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Investigating international time trends in the incidence and prevalence of atopic eczema 1990-2010: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Deckers IA, McLean S, Linssen S, Mommers M, van Schayck CP, Sheikh A. PLoS One. 2012;7:0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loss-of-function polymorphisms in the filaggrin gene are associated with an increased susceptibility to chronic irritant contact dermatitis: a case-control study. de Jongh CM, Khrenova L, Verberk MM, et al. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:621–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Essential oils, part I: introduction. de Groot AC, Schmidt E. Dermatitis. 2016;27:39–42. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nickel sensitization, hand eczema, and loss-of-function mutations in the filaggrin gene. Thyssen JP, Carlsen BC, Menné T. Dermatitis. 2008;19:303–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atopic dermatitis and staphylococcal superantigens. Michie CA, Davis T. Lancet. 1996;347:324. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90498-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atopic dermatitis. Rudikoff D, Lebwohl M. Lancet. 1998;351:1715–1721. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)12082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Predictive factors for hand eczema. Meding B, Swanbeck G. Contact Dermatitis. 1990;23:154–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1990.tb04776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Self-diagnosed dermatitis in adults. Results from a population survey in Stockholm. Meding B, Lidén C, Berglind N. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;45:341–345. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0536.2001.450604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Risk factors influencing the development of hand eczema in a population-based twin sample. Bryld LE, Hindsberger C, Kyvik KO, Agner T, Menné T. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:1214–1220. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2003.05678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hand eczema in Swedish adults - changes in prevalence between 1983 and 1996. Meding B, Järvholm B. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:719–723. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Association between discoid lupus erythematosus and cigarette smoking. Miot HA, Bartoli Miot LD, Haddad GR. Dermatology. 2005;211:118–122. doi: 10.1159/000086440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palmar eczema: a pathogenetic role for acetylsalicylic acid, contraceptives and smoking? Edman B. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2461023/ Acta Derm Venereol. 1988;68:402–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dermatitis among automobile production machine operators exposed to metal-working fluids. Sprince NL, Palmer JA, Popendorf W, Thorne PS, Selim MI, Zwerling C, Miller ER. Am J Ind Med. 1996;30:421–429. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(199610)30:4<421::AID-AJIM7>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prevalence of hand eczema in an adult Swedish population and the relationship to risk occupation and smoking. Montnémery P, Nihlén U, Löfdahl CG, Nyberg P, Svensson A. Acta Derm Venereol. 2005;85:429–432. doi: 10.1080/00015550510036658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tobacco smoking and hand eczema: a population-based study. Meding B, Alderling M, Wrangsjö K. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:752–756. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Life-style factors and hand eczema. Anveden Berglind I, Alderling M, Meding B. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:568–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The effect of tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption on the prevalence of self-reported hand eczema: a cross-sectional population-based study. Thyssen JP, Linneberg A, Menné T, Nielsen NH, Johansen JD. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:619–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Effect of gestational smoke exposure on atopic dermatitis in the offspring. Wang IJ, Hsieh WS, Wu KY, Guo YL, Hwang YH, Jee SH, Chen PC. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008;19:580–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2008.00759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maternal smoking during pregnancy and lactation increases the risk for atopic eczema in the offspring. Schäfer T, Dirschedl P, Kunz B, Ring J, Uberla K. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:550–556. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70242-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The patient-oriented eczema measure: development and initial validation of a new tool for measuring atopic eczema severity from the patients' perspective. Charman CR, Venn AJ, Williams HC. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1513–1519. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.12.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atopic dermatitis is associated with active and passive cigarette smoking in adolescents. Kim SY, Sim S, Choi HG. PLoS One. 2017;12:0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.A short period of breastfeeding in infancy, excessive house cleaning, absence of older sibling, and passive smoking are related to more severe atopic dermatitis in children. Fotopoulou M, Iordanidou M, Vasileiou E, Trypsianis G, Chatzimichael A, Paraskakis E. Eur J Dermatol. 2018;28:56–63. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2017.3165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Association between tobacco smoking and prognosis of occupational hand eczema: a prospective cohort study. Brans R, Skudlik C, Weisshaar E, et al. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:1108–1115. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lifetime exposure to cigarette smoking and the development of adult-onset atopic dermatitis. Lee CH, Chuang HY, Hong CH, Huang SK, Chang YC, Ko YC, Yu HS. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:483–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10116.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smoking and hand dermatitis in the United States adult population. Lai YC, Yew YW. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28:164–171. doi: 10.5021/ad.2016.28.2.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Association of atopic dermatitis with smoking: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kantor R, Kim A, Thyssen JP, Silverberg JI. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1119–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tobacco smoking and hand eczema - is there an association? Sørensen JA, Clemmensen KK, Nixon RL, Diepgen TL, Agner T. Contact Dermatitis. 2015;73:326–335. doi: 10.1111/cod.12429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Does tobacco smoking influence the occurrence of hand eczema? Meding B, Alderling M, Albin M, Brisman J, Wrangsjö K. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:514–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]