Abstract

Background

Transcriptome-wide association studies have been successful in identifying candidate susceptibility genes for colorectal cancer (CRC). To strengthen susceptibility gene discovery, we conducted a large transcriptome-wide association study and an alternative splicing transcriptome-wide association study in CRC using improved genetic prediction models and performed in-depth functional investigations.

Methods

We analyzed RNA-sequencing data from normal colon tissues and genotype data from 423 European descendants to build genetic prediction models of gene expression and alternative splicing and evaluated model performance using independent RNA-sequencing data from normal colon tissues of the Genotype-Tissue Expression Project. We applied the verified models to genome-wide association studies (GWAS) summary statistics among 58 131 CRC cases and 67 347 controls of European ancestry to evaluate associations of genetically predicted gene expression and alternative splicing with CRC risk. We performed in vitro functional assays for 3 selected genes in multiple CRC cell lines.

Results

We identified 57 putative CRC susceptibility genes, which included the 48 genes from transcriptome-wide association studies and 15 genes from splicing transcriptome-wide association studies, at a Bonferroni-corrected P value less than .05. Of these, 16 genes were not previously implicated in CRC susceptibility, including a gene PDE7B (6q23.3) at locus previously not reported by CRC GWAS. Gene knockdown experiments confirmed the oncogenic roles for 2 unreported genes, TRPS1 and METRNL, and a recently reported gene, C14orf166.

Conclusion

This study discovered new putative susceptibility genes of CRC and provided novel insights into the biological mechanisms underlying CRC development.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common malignancies in the world. Genetic factors play an important role in its etiology. To date, more than 200 common genetic variants have been found to be associated with CRC risk through genome-wide association studies (GWAS) (1-6). However, the target genes and the underlying biological mechanisms for the vast majority of these risk loci remain unclear. Furthermore, all these combined GWAS-identified risk variants still only explain about half of the heritability of CRC (6).

Transcriptome-wide association studies have been performed to comprehensively evaluate putative susceptibility genes for human diseases, including cancers (7-16). Despite the successes, transcriptome-wide association studies can suffer from accuracy of gene expression predictions because of the small sample size of the transcriptome data. In particular, this limitation of transcriptome-wide association studies remains a great challenge in prediction model building for relatively low heritable genes. Recently, we conducted transcriptome-wide association studies in CRC and identified a number of putative susceptibility genes (14,16). However, these studies were limited by a single transcriptome dataset generated in normal colon transverse tissues from the Genotype-Tissue Expression Project (GTEx). Thus, the use of other large transcriptome data in normal tissues together with the data from the GTEx is essential in improving prediction models, especially to independently evaluate prediction models, thus facilitating identification of novel genes for CRC risk while reducing false-positive findings. In addition, transcriptome-wide association studies focus on gene expression, whereas genetically predicted alternative splicing, which accounts for a important proportion of disease heritability, remains largely unexplored in CRC (17-19).

In this study, we performed RNA-sequencing in normal colon tissues and incorporated genotyping data from 423 European descendants to build genetic prediction models of gene expression and alternative splicing. We conducted a transcriptome-wide association study and alternative splicing transcriptome-wide association study by applying the verified prediction models to GWAS summary statistics of CRC among European individuals (58 131 cases and 67 347 controls) to perform a comprehensive search for putative CRC susceptibility genes.

Methods

Building genetically predicted models of gene expression and alternative splicing

We trained expression prediction models for genes based on their cis-genetic variants within a region of ± 1 Megabase (Mb), accounting for potential confounding factors, such as top 5 principal components, gender, potential batch effects, and other factors derived from the probabilistic estimation of expression residuals method (20). To assess the efficacy of our models for each gene, we employed a tenfold cross-validation approach to fine tune the model parameters. The performance of the prediction models was evaluated by calculating the squared correlation (R2) between the predicted gene expression levels and the observed gene expression levels. Similarly, we also investigated the cis-regulation of alternative splicing events by predicting them based on cis-genetic variants flanking the alternative splicing site. The models for each alternative splicing event underwent a tenfold cross-validation process to optimize their parameters. The assessment of model performance for alternative splicing was conducted by measuring the R2 between the predicted alternative splicing events and the observed ones.

Association analyses between predicted gene expression and alterative splicing and CRC risk

On the basis of the weight matrix and the summary statistics data on variants from CRC GWAS datasets from 125 478 individuals of European ancestry (58 131 CRC cases and 67 347 controls), we evaluated the association between gene expression or alternative splicing and CRC risk using the method from the S-PrediXcan tool. The details of the formula used in this method are presented in Supplementary Figure 1 (available online). In brief, the z score was used to estimate the association between predicted gene expression (or predicted alternative splicing) and CRC risk, is the weight of variant for predicting the expression of gene (or alternative splicing) . and are the association regression coefficient and its standard error, respectively, for variant in GWAS, and and are the estimated variances of variant and the predicted expression of gene or alternative splicing respectively.

For a more detailed description of additional data analyses and functional assays, please refer to the Supplementary Methods (available online).

Results

Gene expression predicted by cis-genetic variants

We built gene expression prediction models using deep RNA-sequencing data in normal colon tissue samples and high-density genotyping data in blood samples from 423 participants of European ancestry (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, available online). A total of 11 822 expression models for protein-coding and noncoding genes can be predicted by cis-genetic variants with the coefficient of determination R2 of more than 0.01 (10% correlation, P < .05) using the elastic net approach (Methods, Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Figure 1, available online). We next evaluated these models using data from the GTEx and found 6482 (54.8%) genes with a R2 of more than 0.01 in the GTEx dataset. When assessing the potential enhancement in prediction performance for the same gene predicted in our study and the GTEx, we observed notable improvements in our study (median R2 = 0.13) in comparison with the GTEx (median R2 = 0.08), using a paired t test (correlation coefficient = 0.54 with P < 2.2 × 10−16; Supplementary Figure 2, available online). An additional 2182 genes can be predicted at a performance of a stringent threshold with a R2 of more than 0.0625 (25% correlation, P < 1 × 10−6) in our study but failed to be predicted well (R2 < 0.01 or lack of data) in the GTEx. On the basis of these verified models together with those well-predicted ones, we identified and retained these 8664 genes with reliable prediction models for further downstream association analysis (Supplementary Table 4, available online).

Associations of genetically predicted gene expression with CRC risk

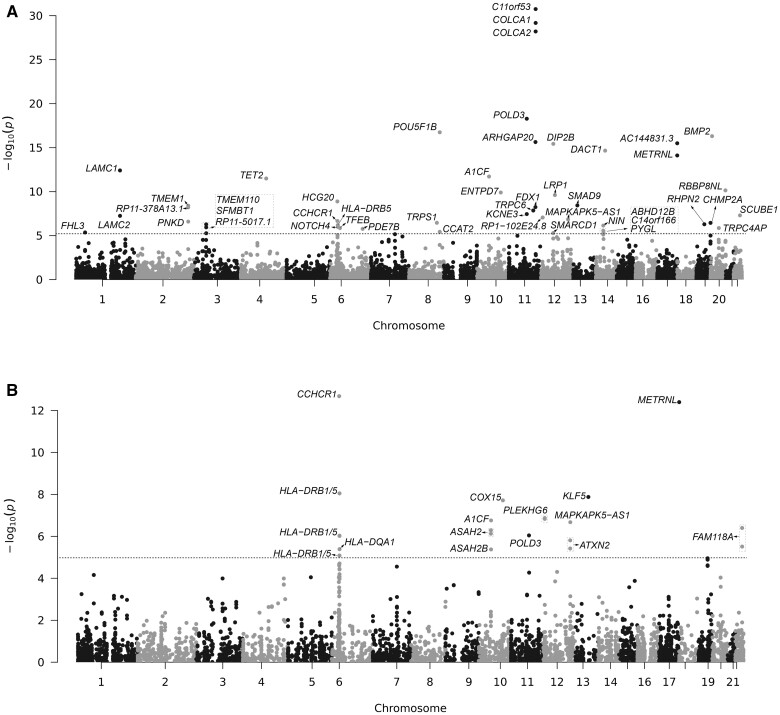

To evaluate associations of predicted gene expression with CRC risk, we used the expression prediction models of the 8664 genes trained on normal colon tissue samples from our study. These models were then applied to summary statistics of GWAS comprised of 58 131 CRC cases and 67 347 controls of European ancestry (Supplementary Table 5, available online). We identified 48 genes genetically predicted expression associated with CRC risk, at a Bonferroni-corrected threshold of P < 5.8 × 10−6 (Figure 1, A). Of these, 13 genes (AC144831.3, ENTPD7, METRNL, NOTCH4, PDE7B, TRPC4AP, CHMP2A, RP11-378A13.1, RP11-5O17.1, CCAT2, RP1-102E24.8, SCUBE1, and TRPS1) were not previously reported to associate with CRC risk in genetic studies (6,14,16,21) (Table 1; Supplementary Methods, available online). To assess whether the genes identified were independent on the established GWAS association signals, we conducted conditional analyses for the associations between CRC risk and these genes, adjusting for the associations with the closest lead variant for each locus (Supplementary Methods, available online). We showed that associations of 3 genes (PDE7B, SCUBE1, and RP1-102E24.8) remained statistically significant at a Bonferroni-corrected threshold of P < 1.04 × 10−3 (adjusting for multiple testing using a Bonferroni correction of 0.05/48 tests). In particular, the putative susceptibility gene, PDE7B (6q23.3) is located at a locus, with more than 2.2 Mb away from the closest GWAS-identified risk variants, suggesting it could be novel loci for CRC risk (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Manhattan plot of the association results from transcriptome-wide association study and splicing transcriptome-wide association study in colorectal cancer. Association results from the transcriptome-wide association study and splicing transcriptome-wide association study among 58 131 cases and 67 347 controls of European ancestry. The dashed lines represent a Bonferroni-corrected significance level of P < 5.8 × 10-6 in transcriptome-wide association study (A) and P < 1.0 × 10-5 in splicing transcriptome-wide association study (B).

Table 1.

Total 13 previously unreported putative susceptibility genes for CRC risk identified by transcriptome-wide association study among 125 478 participants (58 131 cases and 67 347 controls) of European ancestry

| Locus | Genea | z score | P b | R 2 c | Closest risk variant | Distance, Kbd | Conditional P value after adjusting for GWAS signal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2q35 | RP11-378A13.1 | 5.82 | 6.04E-09 | 0.247 | rs3731861 | 69.2 | .530 |

| 3p21.1 | RP11-5O17.1 | 4.55 | 5.40E-06 | 0.092 | rs2581817 | 8.4 | .968 |

| 6p21.32 | NOTCH4 | −4.89 | 1.02E-06 | 0.103 | rs3830041 | 0 | .013 |

| 6q23.3 | PDE7B | −4.78 | 1.71E-06 | 0.075 | rs151127921 | 2178.9 | 5.76E-07 |

| 8q23.3 | TRPS1 | 5.09 | 3.48E-07 | 0.019 | rs16892766 | 808.7 | .501 |

| 8q24.21 | CCAT2 | −4.63 | 3.71E-06 | 0.173 | rs6983267 | 0 | .312 |

| 10q24.2 | ENTPD7 | −6.43 | 1.25E-10 | 0.161 | rs35564340 | 75 | .009 |

| 12p13.31 | RP1-102E24.8 | 5.35 | 8.70E-08 | 0.070 | rs10849434 | 96.0 | 1.96E-05 |

| 17q25.3 | AC144831.3 | 8.17 | 3.19E-16 | 0.077 | rs35204860 | 2.8 | .340 |

| 17q25.3 | METRNL | 7.77 | 7.67E-15 | 0.150 | rs35204860 | 0.47 | .056 |

| 19q13.43 | CHMP2A | 5.09 | 3.56E-07 | 0.065 | rs11670192 | 45.3 | .361 |

| 20q11.22 | TRPC4AP | 4.83 | 1.39E-06 | 0.097 | rs6059938 | 403.1 | .044 |

| 22q13.2 | SCUBE1 | 5.45 | 4.99E-08 | 0.028 | rs5751474 | 0 | 4.59E-04 |

Gene in bold located in the novel risk locus for CRC susceptibility. CRC = colorectal cancer; GWAS = genome-wide association studies.

P value was derived from transcriptome-wide association study analysis among Europeans. Statistically significant based on a Bonferroni-corrected threshold of P < 5.8 × 10−6 from 8664 tests (.05/8664).

Prediction performance (R2) was derived from gene expression model built by using transcriptome data from 423 samples of European descendants in this study.

Distance between a gene with the closest risk variant identified from previous GWAS in CRC.

Of the remaining 35 previously reported genes located in GWAS-identified risk loci, analysis conditioned on the GWAS lead variant showed that 6 genes (TET2, HCG20, CCHCR1, A1CF, DACT1, and BMP2) remained statistically significant at a Bonferroni-corrected threshold of P less than 1.04 × 10−3, and an additional 4 genes showed a nominal P value of less than .05 statistically significance (Table 2). No statistically significant associations were observed for the remaining 25 genes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Total 35 previously reported susceptibility genes for CRC risk identified by transcriptome-wide association study among 125 478 participants (58 131 cases and 67 347 controls) of European ancestry

| Locus | Gene | z score | P a | R 2 b | Closest risk variant | Distance, Kbc | Conditional P value after adjusting for GWAS signal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1p34.3 | FHL3 | 4.59 | 4.39E-06 | 0.134 | rs61776719 | 1.123 | .92 |

| 1q25.3 | LAMC1 | 7.26 | 3.89E-13 | 0.150 | rs8179460 | 0 | .82 |

| 1q25.3 | LAMC2 | 5.43 | 5.65E-08 | 0.161 | rs8179460 | 99.151 | .04 |

| 2q35 | PNKD | −5.15 | 2.56E-07 | 0.188 | rs3731861 | 0 | .56 |

| 2q35 | TMBIM1 | 5.89 | 3.92E-09 | 0.114 | rs3731861 | 33.947 | .60 |

| 3p21.1 | TMEM110 | −5.02 | 5.22E-07 | 0.174 | rs2001732 | 0 | .20 |

| 3p21.1 | SFMBT1 | 4.86 | 1.15E-06 | 0.700 | rs2581817 | 0 | .13 |

| 4q24 | TET2 | −6.97 | 3.20E-12 | 0.202 | rs2007403 | 0 | 3.86E-05 |

| 6p21.33 | HCG20 | −6.07 | 1.30E-09 | 0.013 | rs116353863 | 250.158 | 9.17E-05 |

| 6p21.33 | CCHCR1 | 5.18 | 2.17E-07 | 0.431 | rs2517448 | 47.549 | 6.36E-04 |

| 6p21.32 | HLA-DRB5 | −4.98 | 6.40E-07 | 0.718 | rs9271363 | 88.668 | .33 |

| 6p21.1 | TFEB | 4.83 | 1.40E-06 | 0.087 | rs4711689 | 0 | .51 |

| 8q24.21 | POU5F1B | −8.51 | 1.79E-17 | 0.333 | rs7013278 | 11.643 | .09 |

| 10q11.23 | A1CF | 7.04 | 1.91E-12 | 0.314 | rs10821905 | 0.658 | 8.50E-04 |

| 11q13.4 | KCNE3 | 5.51 | 3.55E-08 | 0.089 | rs11236187 | 185.792 | .01 |

| 11q13.4 | POLD3 | 8.91 | 5.18E-19 | 0.016 | rs11236187 | 0 | .75 |

| 11q22.1 | TRPC6 | 5.67 | 1.40E-08 | 0.319 | rs2155065 | 0 | .06 |

| 11q22.3 | FDX1 | −5.82 | 5.74E-09 | 0.175 | rs3087967 | 821.23 | .97 |

| 11q23.1 | ARHGAP20 | −8.20 | 2.31E-16 | 0.107 | rs3087967 | 572.922 | .14 |

| 11q22.3 | ARHGAP20 | −8.20 | 2.31E-16 | 0.107 | rs3087967 | 572.922 | .14 |

| 11q23.1 | C11orf53 | −11.67 | 1.75E-31 | 0.424 | rs3087967 | 0 | .93 |

| 11q23.1 | COLCA1 | −11.36 | 6.62E-30 | 0.643 | rs3087967 | 4.676 | .89 |

| 11q23.1 | COLCA2 | −11.16 | 6.18E-29 | 0.649 | rs3087967 | 12.444 | .94 |

| 12q13.12 | SMARCD1 | 4.56 | 5.23E-06 | 0.068 | rs11169572 | 722.395 | .92 |

| 12q13.12 | DIP2B | 8.15 | 3.71E-16 | 0.082 | rs11169572 | 74.44 | .71 |

| 12q13.3 | LRP1 | 6.33 | 2.48E-10 | 0.412 | rs7398375 | 0 | 3.17E-03 |

| 12q24.12 | MAPKAPK5-AS1 | 5.26 | 1.42E-07 | 0.115 | rs653178 | 269.812 | .04 |

| 13q13.3 | SMAD9 | −5.90 | 3.70E-09 | 0.445 | rs12427846 | 0 | .83 |

| 14q22.1 | NIN | −4.96 | 7.19E-07 | 0.478 | rs28611105 | 61.819 | .65 |

| 14q22.1 | PYGL | −4.55 | 5.42E-06 | 0.628 | rs28611105 | 0 | .70 |

| 14q22.1 | ABHD12B | −4.69 | 2.79E-06 | 0.361 | rs28611105 | 0 | .77 |

| 14q22.1 | C14orf166 | 4.57 | 4.92E-06 | 0.137 | rs1497077 | 14.246 | .38 |

| 14q23.1 | DACT1 | −7.93 | 2.19E-15 | 0.200 | rs17094983 | 74.322 | 1.34E-06 |

| 19q13.11 | RHPN2 | 5.02 | 5.11E-07 | 0.399 | rs28840750 | 0 | .08 |

| 20p12.3 | BMP2 | −8.39 | 4.90E-17 | 0.309 | rs28488 | 1.294 | 1.80E-15 |

| 20q13.33 | RBBP8NL | −6.52 | 7.22E-11 | 0.121 | rs1741640 | 52.879 | .11 |

P value was derived from transcriptome-wide association study analysis among Europeans. Statistically significant based on a Bonferroni-corrected threshold of P < 5.8 × 10−6 from 8664 tests (.05/8664). CRC = colorectal cancer; GWAS = genome-wide association studies.

Prediction performance (R2) was derived from gene expression model built by using transcriptome data from 423 samples of European descendants in this study.

Distance between a gene with the closest risk variant identified from previous CRC GWAS.

Putative susceptibility gene discovered by splicing transcriptome-wide association study

Similar to the transcriptome-wide association study analysis above, we built alternative splicing prediction models using RNA-sequencing data in normal colon tissue samples and genotyping data from 423 participants of European ancestry (Supplementary Methods, available online). Our result showed that 9771 alternative splicing events in protein-coding and noncoding genes can be predicted by cis-genetic variants with a R2 of more than 0.01 (10% correlation, P < .05) (Supplementary Table 6, available online). We next used data from the GTEx to evaluate these models (Supplementary Table 7, available online). Of these, we found 3893 alternative splicing events with a R2 of more than 0.01 in the GTEx. An additional 1044 alternative splicing events can be predicted at a performance of a stringent threshold with a R2 more than 0.0625 (25% correlation) in our study although failed to be predicted well (R2 < 0.01 or lack of data) in the GTEx (Supplementary Table 8, available online).

At a Bonferroni-corrected threshold of P < 1.01 × 10−5, our splicing transcriptome-wide association study analysis identified 15 genes (from 23 alternative splicing events) associated with CRC risk, including 4 genes (ATXN2, COX15, METRNL, and FAM118A) not previously reported for CRC risk (14,15,21) (Table 3, Figure 1, B). Of these 15 genes, conditional analysis showed that 3 genes (A1CF, PLEKHG6, and CCHCR1) remained statistically significant at a Bonferroni-corrected threshold of P < 2.17 × 10−3, and an additional 2 genes (HLA-DRB1 and HLA-DRB5) showed a nominal P value less than .05 statistically significance (Table 3).

Table 3.

Total 15 putative susceptibility genes for CRC risk identified by splicing transcriptome-wide association study among 125 478 participants (58 131 cases and 67 347 controls) of European ancestry

| Locus | Genea | Alternative splicing | P b | R 2 c | Closest risk variant | Distance, Kbd | Conditional P value after adjusting for GWAS signal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6p21.32 | HLA-DRB5 | chr6:32584378:32589643 | 8.93E-09 | 0.749 | rs9271363 | 29.31 | .03 |

| 6p21.32 | HLA-DRB1 | chr6:32584378:32589643 | 8.90E-09 | 0.749 | rs9271363 | 29.31 | .02 |

| 6p21.32 | HLA-DQA1 | chr6:32642253:32642610 | 4.09E-06 | 0.765 | rs9271363 | 23.30 | .22 |

| 6p21.33 | CCHCR1 | chr6:31144788:31144885 | 2.08E-13 | 0.019 | rs2517448 | 49.90 | 5.14E-08 |

| 10q11.23 | ASAH2 | chr10:50196919:50199051 | 5.15E-07 | 0.146 | rs10821905 | 687.28 | .50 |

| 10q11.23 | ASAH2B | chr10:50745274:50749343 | 4.20E-06 | 0.224 | rs10821905 | 136.99 | .89 |

| 10q11.23 | A1CF | chr10:50882705:50885581 | 1.74E-07 | 0.365 | rs10821905 | 0.75 | .00 |

| 10q24.2 | COX15 | chr10:99714718:99716348 | 1.93E-08 | 0.056 | rs35564340 | 130.21 | .08 |

| 11q13.4 | POLD3 | chr11:74594116:74604692 | 9.03E-07 | 0.131 | rs11236187 | 48.83 | .54 |

| 12p13.31 | PLEKHG6 | chr12:6317696:6317857 | 1.34E-07 | 0.449 | rs10849434 | 19.82 | 1.27E-08 |

| 12q24.12 | ATXN2 | chr12:111516363:111518249 | 1.55E-06 | 0.027 | rs653178 | 51.70 | .10 |

| 12q24.12 | MAPKAPK5-AS1 | chr12:111840477:111841327 | 2.12E-07 | 0.029 | rs653178 | 270.53 | .34 |

| 13q22.1 | KLF5 | chr13:73063883:73075708 | 1.32E-08 | 0.122 | rs45597035 | 0 | .97 |

| 17q25.3 | METRNL | chr17:83085323:83093167 | 3.99E-13 | 0.031 | rs35204860 | 2.42 | .10 |

| 22q13.31 | FAM118A | chr22:45328063:45330603 | 3.99E-07 | 0.469 | rs9614460 | 18.75 | .15 |

Genes in bold are newly identified for CRC susceptibility. CRC = colorectal cancer; GWAS = genome-wide association studies.

P value was derived from splicing transcriptome-wide association study analysis among Europeans. Statistically significant based on a Bonferroni-corrected threshold of P < 1 × 10−5 from 4937 tests (.05/4937).

Prediction performance (R2) was derived from splicing model built by using splicing data from 423 samples of European descendants in this study.

Distance between a gene with the closest risk variant identified from previous GWAS in CRC.

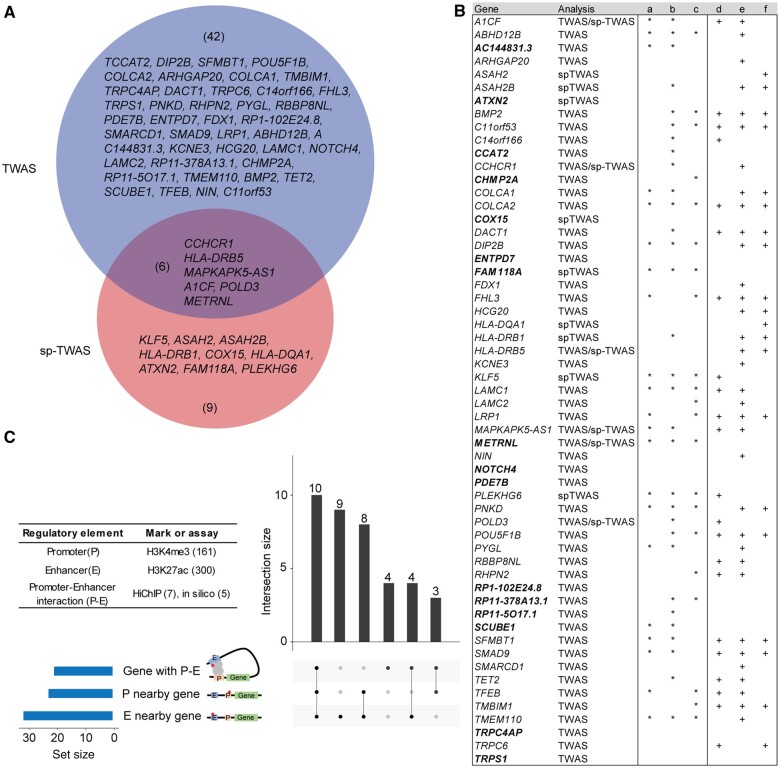

Putative susceptibility genes supported by colocalization analysis

We identified 57 genes associated with CRC risk after combining findings from transcriptome-wide association study and splicing transcriptome-wide association study, including 16 genes not reported in previous GWAS. Of these 57 genes, 6 genes (A1CF, CCHCR1, HLA-DRB5, POLD3, METRNL, and MAPKAPK5-AS1) were identified in both analyses, whereas 42 and 9 genes were only identified by 1 of the analyses (Figure 2, A). To investigate whether expression or splicing of the identified genes might mediate existing GWAS associations, we conducted a colocalization analysis between their expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) or splicing QTL (sp-QTL) and GWAS association signals using summary data–based Mendelian randomization (22) (Supplementary Methods, available online). The results revealed that 40 genes showed statistically significant colocalization at a Bonferroni-corrected P value less than .05, supporting that a high proportion (70.2% of 57) of our identified genes could be susceptibility genes to mediate the established risk signals (Supplementary Table 9, available online). As expected, no statistically significant colocalizations were observed for a majority of our identified genes that are likely independent of the previous GWAS, such as gene PDE7B within novel locus and 3 unreported genes in known GWAS loci (SCUBE1 and RP1-102E24.8 at Bonferroni-corrected P < .05 and NOTCH4 at nominal P < .05, based on conditional analysis).

Figure 2.

A summary of the 57 genes identified through TWAS and sp-TWAS. A) Venn diagram depicting genes identified in TWAS and sp-TWAS. Six genes (A1CF, CCHR1, HLA-DRB5, POLD3, METRNL, and MAPKAPK5-AS1) were identified in both analyses. B) Characterization of the 57 genes identified in our study. Genes in bold refer to previously unreported genes for CRC risk; (a) a gene supported by the closest potential regulatory lead variant (the strongest risk association in the prediction model) located in its promoter via proximal regulation, (b) a gene supported by the potential regulatory lead variant located in its nearby enhancer via distal regulation (indicated by “∗” or “+”), (c) a gene supported by the potential regulatory lead variant gene located in enhancer via distal regulation based on chromatin-chromatin interaction data, (d) a gene reported as an effector gene (15), (e) a gene identified in previous TWAS analysis (14,15), (f) a gene identified in previous and our colocalization analyses (14,21). C) The identified genes were supported by potential functional variants located in regulatory elements: promoter (P), enhancer (E), and interactions between promoter and enhancer (P-E). The histone modifications H3K4me3 (from 161 ChIP-seq peak files) and H3K27ac (from 300 ChIP-seq files) were used to characterize activities of promoter and enhancer, respectively. The chromatin-chromatin interactions from HiChromatin Immunoprecipitation (Hi-ChIP) experiments and computational predictions (ie, FANTOM5 - Functional Annotation of Mammalian Genomes project) were used to identify promoter-enhancer interactions. CRC = colorectal cancer; sp-TWAS = splicing transcriptome-wide association studies; TWAS = transcriptome-wide association studies

Putative susceptibility genes supported by functional genomic analysis

To search for additional evidence for the 57 identified putative susceptibility genes, we evaluated 879 putative regulatory variants in strong linkage disequilibrium (R2 > 0.8 in European populations) with the variants that present the strongest associations with CRC risk in the prediction model (Supplementary Tables 10 and 11, Supplementary Methods, available online). We found that 34 genes were likely regulated by the closest putative regulatory variants with either promoter and/or enhancer activities (Figure 2, B and C; Supplementary Table 12, available online). On further analysis of chromatin-chromatin interaction data, we discovered that an additional 4 genes (LAMC2, CHMP2A, KCNE3, and RHPN2) were regulated distally by putative functional variants through long-term promoter-enhancer interactions (Supplementary Table 13, available online). In summary, our comprehensive analysis revealed that a substantial proportion of genes, specifically 38 (66.7%) genes, are subject to regulation by putative functional variants (Supplementary Tables 12 and 13, available online).

Functional assays for putative susceptibility genes

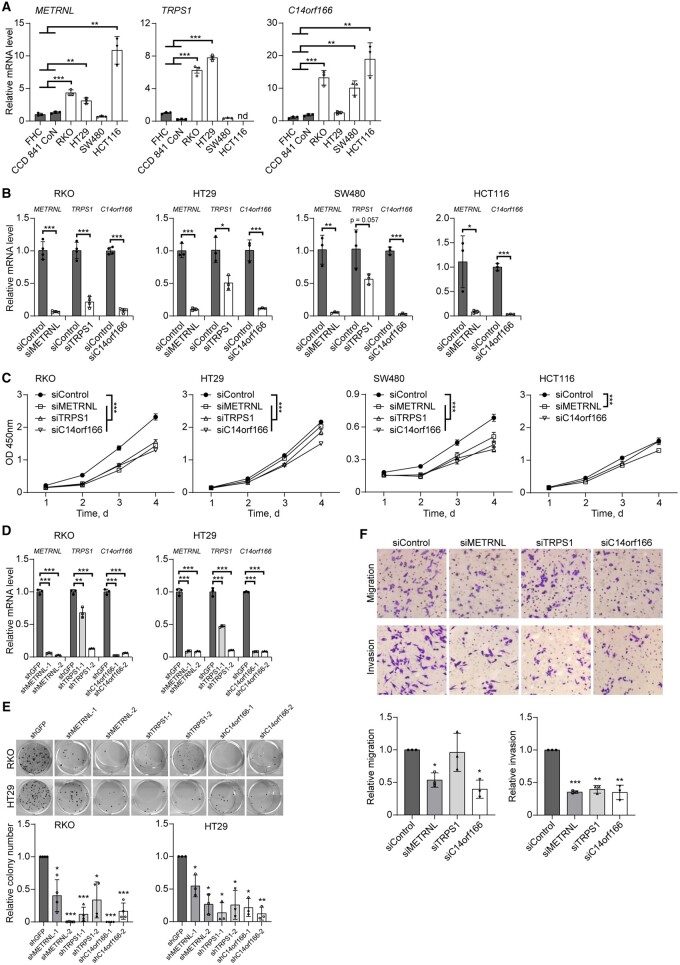

We next investigated the potential function of previously unreported putative susceptibility genes identified in this study through in vitro assays in multiple CRC cell lines. A total of 4 genes, including TRPS1, METRNL, SCUBE1, and C14orf166 [a recently reported gene (6)], were selected for downstream experiments based on the strength of their association signals and their potential oncogenic functions, as their predicted elevated expressions were associated with an increased risk of CRC.

We examined relative expression levels of these 4 selected genes in 4 CRC cell lines (RKO, HT29, HCT116, and SW480) through real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). In line with the transcriptome-wide association study findings, we observed relatively higher expression levels of genes TRPS1, METRNL, and C14orf166, except SCUBE1, in at least 2 CRC cell lines compared with normal colon cell lines (FHC and CCD 841 CoN) (Figure 3, A; Supplementary Figure 3, A, available online). We further investigated the cellular functions of these 3 genes using in vitro assays.

Figure 3.

The effect of 3 putative oncogenes (TRPS1, METRNL, and C14orf166) on CRC cell proliferation, colony formation, migration, and invasion. A) Reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays for METRNL, TRPS1, and C14orf166 mRNA levels in 4 colorectal cancer cell lines (RKO, HT29, SW480, and HCT116) and 2 normal colon epithelial cell lines (FHC and CCD 841 CoN). B) METRNL, TRPS1, and C14orf166 were silenced by target short interfering RNA (siRNA) in RKO, HT29, SW480, and HCT116 cells. Knockdown efficiency was confirmed by RT-PCR assays in these cell lines. C) Cell viabilities were measured using CCK8 assays at different time points (days 1, 2, 3, and 4). Statistical tests were performed using results from day 4. OD = optical density. D) METRNL, TRPS1, and C14orf166 were separately silenced by 2 target short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) in RKO and HT29 cells. Cells transfected with shGFP were used as control. Knockdown efficiency was confirmed by RT-PCR assays. E) After RKO and HT29 cells were transfected with target shRNAs and shRNA targeting green fluorescence protein (shGFP), the cell colonies were imaged (upper) and quantified (lower) using a colony formation assay. F) Migration and invasion were measured using Transwell assays with target siRNAs and control cells. In all RT-PCR assays, β-ACTIN was used as the reference control. All experiments were replicated at least 3 times. Data are presented as mean (SD). * P < .05; ** P < .01; *** P < .001 (2-tailed Student t test in [A], [B], [C], and [D] and Fisher Least Significant Difference (LSD) test in [E] and [F]). nd = not detectable.

We conducted gene knockdown experiments to inhibit expressions of these 3 putative oncogenes (TRPS1, METRNL, and C14orf166) in 4 CRC cell lines using short interfering RNA (Supplementary Table 14, available online). We confirmed high knockdown efficiency by showing a reduction of approximately 50%-95% of their expression in these cell lines (Figure 3, B). Using CCK-8 assays, we observed a statistically significant reduction in cell proliferation among knockdown cells for each gene compared with control cells (P < .05). This trend was consistent across 3 cell lines (RKO, HT29, and SW480) (Figure 3, C). Furthermore, long-term inhibition of CRC cell growth was verified through colony formation assays, where each gene was silenced using short hairpin RNA (shRNA). As the SW480 cell line showed limited colony-forming ability, colony formation assays were exclusively conducted in the RKO and HT29 cell lines (Figure 3, D and E). Furthermore, we observed that knockdown of each gene can lead to a significantly decreased migration and invasion when compared with control cells (RKO cell line), at a P value less than .05 (Figure 3, F). Together, these findings confirmed that TRPS1, METRNL, and C14orf166 play an oncogenic role in regulating CRC cell behavior.

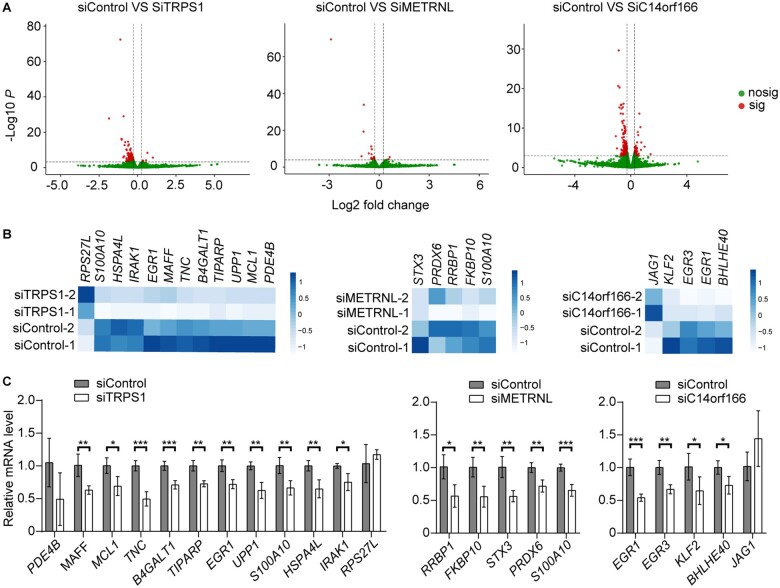

To further explore downstream genes and pathways regulated by these 3 putative oncogenes, we performed RNA-sequencing in gene knockdown and control cells (RKO cell line). We identified 106, 16, and 175 putative downstream regulated genes for TRPS1, METRNL, and C14orf166, respectively, through differential gene expression analysis, at a false-discovery rate (FDR)–adjusted P value less than .05 (Figure 4, A; Supplementary Table 15, Supplementary Methods, available online). Further functional enrichment analysis using Enrichr (23,24) showed that putative downstream regulated genes of TRPS1 and C14orf166 were significantly enriched in cancer-related pathways at a FDR–adjusted P value less than .05 (Supplementary Table 16, available online). Of note, we observed that the enriched tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha signaling via nuclear factor (NF)-kB pathway and the p53 pathway, which play important roles in cancer development and progression (25,26), were commonly identified among putative downstream regulated genes of TRPS1 and C14orf166. For METRNL, we also observed that 10 of its 16 downstream regulated genes were cancer related (Supplementary Table 16, available online).

Figure 4.

Putative downstream genes of 3 putative oncogenes (TRPS1, METRNL, and C14orf166). A) Volcano plot showing differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from RNA-sequencing data analysis. Red dots refer to significant genes at false-discovery rate–adjusted P value less than .05 and absolute fold-change more than 1.2. Otherwise, they are represented by green dots. B) Heatmap plots of selected DEGs, which were related to cancer based on pathway analysis and published literature. C) Reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction verification for target genes in (B) employs RKO cells with target and control short interfering RNA. Experiments were replicated 4 times. Results were presented as mean (SD). * P < .05; ** P < .01; *** P < .001 (2-tailed Student t test).

We performed further experimental verification for 20 selected downstream genes, which were implicated in CRC carcinogenesis using RT-PCR (Figure 4, B and C; Supplementary Table 14, available online). For RT-PCR validation of 20 selected downstream target genes, all of these genes showed consistent directionality of effect between RT-PCR experiments and RNA-sequencing analysis. Of them, 17 genes showed statistically significant expression alterations. However, no staistically significant expression alterations were observed for the remaining 3 genes (PDE4B, RPS27L, and JAG1) in the RT-PCR experiments. For TRPS1, we verified that 5 TNF-alpha signaling via NF-kB pathway–related genes and 4 p53 pathway–related genes showed statistically significant expression changes in the TRPS1 knockdown cell line compared with the control cell line. For C14orf166, we verified that 4 TNF-alpha signaling via NF-kB pathway–related genes showed statistically significant expression changes in the C14orf166 knockdown cell line compared with the control cell line. For METRNL, we verified 5 genes showed statistically significant expression changes in the METRNL knockdown cell line compared with the control cell line. Of these 5 genes, S100A10, PRDX6, and STX3 lie in p53, reactive oxygen species, and DNA repair pathways, respectively, whereas 2 remaining genes, RRBP1 and FKBP10, have been reported to be related to carcinogenesis by in vitro or in vivo functional experimental studies in CRC or other cancer types (27,28).

Discussion

Through conducting large-scale transcriptome-wide association study and splicing transcriptome-wide association study in CRC among European populations based on large, new transcriptome data in normal colon tissues, we identified 57 genes that showed statistically significant associations with CRC risk. Of these, we identified 16 putative susceptibility genes previously unreported for CRC, including a novel risk locus (PDE7B at 6q23.3), and confirmed 41 previously reported putative susceptibility genes. Using in vitro functional assays in gene knockdown experiments, we further showed that 3 putative susceptibility genes—TRPS, METRNL, and C14orf166—play a potential oncogenic role in CRC behavior. Our study provides novel insight to improve understanding of the genetics basis and etiology of CRC.

To our knowledge, this is the first large study to use a transcriptome-wide association study approach to systematically explore associations of genetically predicted alternative splicing with CRC risk. With our new RNA-sequencing data, together with existing alternative splicing data from the GTEx, we identified reliable prediction models for alternative splicing for association analysis. Through this complementary approach to traditional transcriptome-wide association study analysis, we successfully identified additional potential CRC susceptibility genes. Of note, among the 2486 well-predicted genes in splicing transcriptome-wide association study, 875 (35.2%) were not covered by our traditional transcriptome-wide association study analysis. Notably, 9 putative susceptibility genes were identified in the splicing transcriptome-wide association study analysis that were not captured in the transcriptome-wide association study analysis.

For PDE7B, the one located in the novel locus, we observed an association between its higher predicted expression with a decrease in CRC risk in our transcriptome-wide association study analysis, likely implying a potential tumor suppressor role in CRC carcinogenesis. In line with these findings, we observed that PDE7B showed statistically significantly lower expression in CRC cell lines when compared with normal colon cell lines, and the same pattern was found when comparing tumor and normal colon tissues, based on data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (Supplementary Figure 3, B, available online).

It should be noted that there have been recent advancements in transcriptome-wide association study approaches, such as our susceptible transcription factor (sTF)–transcriptome-wide association studies framework (29,30) and other referenced methods (31-33), which aim to improve the discovery of disease susceptibility genes. Conducting future transcriptome-wide association study analyses using these advanced approaches is likely to reveal additional statistically significant genes. Our analysis was limited to individuals of European ancestry, and further investigations are needed to assess the relevance of these genes in non-European populations. Additionally, future refined transcriptome-wide association studies should consider heterogeneity in the genetic architecture of CRC subtypes (34). By utilizing gene expression data from normal tissues, we aimed to minimize bias from reverse causation, while conducting transcriptome-wide association studies on adenoma tissues may also uncover additional susceptibility genes. We confirmed the potential oncogenic functions of TRPS1, METRNL, and C14orf166 in CRC cell lines. Although we explored their downstream target genes, a more comprehensive investigation into their regulatory network is needed. Moreover, our functional studies were limited to in vitro experiments using cell lines. To thoroughly understand the functional roles of transcriptome-wide association study–identified CRC susceptibility genes, future endeavors utilizing in vivo models will be crucial.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all study participants and the research staff of all parent studies for their contributions and commitment to this project. The data analyses were conducted using the Advanced Computing Center for Research and Education (ACCRE) at Vanderbilt University.

We also acknowledged the exceptional resources for consortia of colorectal cancer GWAS in Supplementary Methods (available online). The funder did not play a role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Contributor Information

Zhishan Chen, Division of Epidemiology, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt Epidemiology Center, Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN, USA.

Wenqiang Song, Division of Epidemiology, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt Epidemiology Center, Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN, USA; Department of Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

Xiao-Ou Shu, Division of Epidemiology, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt Epidemiology Center, Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN, USA.

Wanqing Wen, Division of Epidemiology, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt Epidemiology Center, Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN, USA.

Matthew Devall, Department of Public Health Sciences, Center for Public Health Genomics, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA.

Christopher Dampier, Department of Public Health Sciences, Center for Public Health Genomics, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA.

Ferran Moratalla-Navarro, Oncology Data Analytics Program, Catalan Institute of Oncology (ICO), L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain; Colorectal Cancer Group, ONCOBELL Program, Institut de Recerca Biomedica de Bellvitge (IDIBELL), L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain; Department of Clinical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences and Universitat de Barcelona Institute of Complex Systems (UBICS), University of Barcelona (UB), L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain; Consortium for Biomedical Research in Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBERESP), Madrid, Spain.

Qiuyin Cai, Division of Epidemiology, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt Epidemiology Center, Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN, USA.

Jirong Long, Division of Epidemiology, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt Epidemiology Center, Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN, USA.

Luc Van Kaer, Department of Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

Lan Wu, Department of Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

Jeroen R Huyghe, Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA.

Minta Thomas, Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA.

Li Hsu, Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA; Department of Biostatistics, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

Michael O Woods, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Discipline of Genetics, St. John’s, ON, Canada.

Demetrius Albanes, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Daniel D Buchanan, Colorectal Oncogenomics Group, Department of Clinical Pathology, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia; University of Melbourne Centre for Cancer Research, Victorian Comprehensive Cancer Centre, Parkville, VIC, Australia; Genetic Medicine and Family Cancer Clinic, The Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, VIC, Australia.

Andrea Gsur, Center for Cancer Research, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria.

Michael Hoffmeister, Division of Clinical Epidemiology and Aging Research, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Germany.

Pavel Vodicka, Department of Molecular Biology of Cancer, Institute of Experimental Medicine of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Prague, Czech Republic; Institute of Biology and Medical Genetics, First Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic; Faculty of Medicine and Biomedical Center in Pilsen, Charles University, Pilsen, Czech Republic.

Alicja Wolk, Institute of Environmental Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden.

Loic Le Marchand, University of Hawaii Cancer Center, Honolulu, HI, USA.

Anna H Wu, Preventative Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Amanda I Phipps, Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA; Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

Victor Moreno, Oncology Data Analytics Program, Catalan Institute of Oncology (ICO), L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain; Colorectal Cancer Group, ONCOBELL Program, Institut de Recerca Biomedica de Bellvitge (IDIBELL), L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain; Department of Clinical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences and Universitat de Barcelona Institute of Complex Systems (UBICS), University of Barcelona (UB), L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain; Consortium for Biomedical Research in Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBERESP), Madrid, Spain.

Peters Ulrike, Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

Wei Zheng, Division of Epidemiology, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt Epidemiology Center, Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN, USA.

Graham Casey, Department of Public Health Sciences, Center for Public Health Genomics, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA.

Xingyi Guo, Division of Epidemiology, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt Epidemiology Center, Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN, USA; Department of Biomedical Informatics, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN, USA.

Data availability

The data from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx, version 8) project used in this study are publicly available under the National Center for Biotechnology Information database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) accession number phs000424.v8.p2. The CRC-relevant epigenome data were sourced from the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, with accession numbers GSE133928, GSE136888, and GSE156613. To access the CRC GWAS data, researchers can refer to the dbGaP accession numbers phs001415.v1.p1, phs001315.v1.p1, phs001078.v1.p1, and phs001903.v1.p1, and additional UK Biobank resource, which can be accessed at http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk (2,5). The transcriptome and genotype data as well as the sample covariates from the BarcUVa-Seq project can be accessed using the dbGaP accession number phs003338.v1.p1.

Author contributions

Zhishan Chen, PhD (Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Visualization; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing), Wei Zheng, MD, PhD (Data curation; Resources; Writing—review & editing), Peters Ulrike, PhD, MPH (Data curation; Resources; Writing—review & editing), Victor Moreno, PhD (Resources; Writing—review & editing), Amanda Phipps, PhD, MPH (Resources; Writing—review & editing), Anna Wu, PhD (Resources; Writing—review & editing), Loic Le Marchand, MD, PhD (Resources; Writing—review & editing), Alicja Wolk, PhD (Resources; Writing—review & editing), Pavel Vodicka, MD, PhD (Resources; Writing—review & editing), Michael Hoffmeister, PhD (Resources; Writing—review & editing), Andrea Gsur, PhD (Resources; Writing—review & editing), Daniel Buchanan, PhD (Resources; Writing—review & editing), Demetrius Albanes, MD (Resources; Writing—review & editing), Graham Casey, PhD (Conceptualization; Data curation; Resources; Writing—review & editing), Michael Woods, PhD (Resources; Writing—review & editing), Minta Thomas, PhD (Writing—review & editing), Jeroen Huyghe, PhD (Resources; Writing—review & editing), Lan Wu, MD (Writing—review & editing), Luc Van Kaer, PhD (Writing—review & editing), Jirong Long, PhD (Writing—review & editing), Qiuyin Cai, MD, PhD (Writing—review & editing), Ferran Moratalla-Navarro, PhD (Resources; Writing—review & editing), Christopher Dampier, MD (Data curation; Writing—review & editing), Matthew Devall, PhD (Data curation; Writing—review & editing), Wanqing Wen, MD, MPH (Writing—review & editing), Xiao-Ou Shu, MD, PhD (Writing—review & editing), Wenqiang Song, PhD (Investigation; Visualization; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing), Li Hsu, PhD (Writing—review & editing), and Xingyi Guo, PhD (Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Supervision; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing)

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the US National Institutes of Health (R37 CA227130 to X.G). This research was also supported by Agency for Management of University and Research Grants (AGAUR) of the Catalan Government grant 2017SGR723; Instituto de Salud Carlos III, co-funded by FEDER funds –a way to build Europe– grant PI17-00092; Spanish Association Against Cancer (AECC) Scientific Foundation grant GCTRA18022MORE; Consortium for Biomedical Research in Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBERESP), action Genrisk.

Conflicts of interest

L. Van Kaer is a member of the scientific advisory board of Isu Abxis Co, Ltd (South Korea). The other authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1. Lu Y, Kweon SS, Tanikawa C, et al. Large-scale genome-wide association study of East Asians identifies loci associated with risk for colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(5):1455-1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huyghe JR, Bien SA, Harrison TA, et al. Discovery of common and rare genetic risk variants for colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2019;51(1):76-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lu Y, Kweon SS, Cai Q, et al. Identification of novel loci and new risk variant in known loci for colorectal cancer risk in East Asians. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29(2):477-486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Law PJ, Timofeeva M, Fernandez-Rozadilla C, et al. ; PRACTICAL Consortium. Association analyses identify 31 new risk loci for colorectal cancer susceptibility. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huyghe JR, Harrison TA, Bien SA, et al. Genetic architectures of proximal and distal colorectal cancer are partly distinct. Gut. 2021;70(7):1325-1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fernandez-Rozadilla C, Timofeeva M, Chen Z, et al. Deciphering colorectal cancer genetics through multi-omic analysis of 100,204 cases and 154,587 controls of European and east Asian ancestries. Nat Genet. 2023;55(1):89-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gamazon ER, Wheeler HE, Shah KP, et al. ; GTEx Consortium. A gene-based association method for mapping traits using reference transcriptome data. Nat Genet. 2015;47(9):1091-1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gusev A, Ko A, Shi H, et al. Integrative approaches for large-scale transcriptome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2016;48(3):245-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wu L, Shi W, Long J, et al. ; kConFab/AOCS Investigators. A transcriptome-wide association study of 229,000 women identifies new candidate susceptibility genes for breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2018;50(7):968-978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mancuso N, Gayther S, Gusev A, et al. ; PRACTICAL Consortium. Large-scale transcriptome-wide association study identifies new prostate cancer risk regions. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhong J, Jermusyk A, Wu L, et al. A transcriptome-wide association study identifies novel candidate susceptibility genes for pancreatic cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;112(10):1003-1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lu Y, Beeghly-Fadiel A, Wu L, et al. A transcriptome-wide association study among 97,898 women to identify candidate susceptibility genes for epithelial ovarian cancer risk. Cancer Res. 2018;78(18):5419-5430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gusev A, Lawrenson K, Lin X, et al. ; Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium. A transcriptome-wide association study of high-grade serous epithelial ovarian cancer identifies new susceptibility genes and splice variants. Nat Genet. 2019;51(5):815-823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guo X, Lin W, Wen W, et al. Identifying novel susceptibility genes for colorectal cancer risk from a transcriptome-wide association study of 125,478 subjects. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(4):1164-1178.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fernandez-Rozadilla C, Timofeeva MN, Chen Z, Law PJ, Thomas M, Schmit SL.. Deciphering colorectal cancer genetics through multi-omic analysis of 100,204 cases and 154,587 controls of European and Asian descent. Nat Genet. 2023;55(1):89-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bien SA, Su YR, Conti DV, et al. Genetic variant predictors of gene expression provide new insight into risk of colorectal cancer. Hum Genet. 2019;138(4):307-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Garrido-Martín D, Borsari B, Calvo M, Reverter F, Guigó R.. Identification and analysis of splicing quantitative trait loci across multiple tissues in the human genome. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. de Goede OM, Nachun DC, Ferraro NM, et al. ; GTEx Consortium. Population-scale tissue transcriptomics maps long non-coding RNAs to complex disease. Cell. 2021;184(10):2633-2648.e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Qi T, Wu Y, Fang H, et al. Genetic control of RNA splicing and its distinct role in complex trait variation. Nat Genet. 2022;54(9):1355-1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stegle O, Parts L, Durbin R, Winn J.. A Bayesian framework to account for complex non-genetic factors in gene expression levels greatly increases power in eQTL studies. PLoS Comput Biol. 2010;6(5):e1000770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yuan Y, Bao J, Chen Z, et al. Multi-omics analysis to identify susceptibility genes for colorectal cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2021;30(5):321-330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhu Z, Zhang F, Hu H, et al. Integration of summary data from GWAS and eQTL studies predicts complex trait gene targets. Nat Genet. 2016;48(5):481-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen EY, Tan CM, Kou Y, et al. Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14(1):128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kuleshov MV, Jones MR, Rouillard AD, et al. Enrichr: A comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W90-W97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Joerger AC, Fersht AR.. The p53 pathway: origins, inactivation in cancer, and emerging therapeutic approaches. Annu Rev Biochem. 2016;85:375-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wu Y, Zhou BP.. TNF-α/NF-κB/Snail pathway in cancer cell migration and invasion. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(4):639-644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pan Y, Cao F, Guo A, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum ribosome-binding protein 1, RRBP1, promotes progression of colorectal cancer and predicts an unfavourable prognosis. Br J Cancer. 2015;113(5):763-772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ramadori G, Ioris RM, Villanyi Z, et al. FKBP10 regulates protein translation to sustain lung cancer growth. Cell Rep. 2020;30(11):3851-3863.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wen W, Chen Z, Bao J, et al. Genetic variations of DNA bindings of FOXA1 and co-factors in breast cancer susceptibility. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):5318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. He J, Wen W, Beeghly A, et al. Integrating transcription factor occupancy with transcriptome-wide association analysis identifies susceptibility genes in human cancers. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):7118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Khunsriraksakul C, McGuire D, Sauteraud R, et al. Integrating 3D genomic and epigenomic data to enhance target gene discovery and drug repurposing in transcriptome-wide association studies. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dai Q, Zhou G, Zhao H, et al. ; eQTLGen Consortium. OTTERS: a powerful TWAS framework leveraging summary-level reference data. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gao G, Fiorica PN, McClellan J, et al. A joint transcriptome-wide association study across multiple tissues identifies candidate breast cancer susceptibility genes. Am J Hum Genet. 2023;110(6):950-962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Holowatyj AN, Wen W, Gibbs T, et al. Racial/ethnic and sex differences in somatic cancer gene mutations among patients with early-onset colorectal cancer. Cancer Discov. 2023;13(3):570-579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx, version 8) project used in this study are publicly available under the National Center for Biotechnology Information database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) accession number phs000424.v8.p2. The CRC-relevant epigenome data were sourced from the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, with accession numbers GSE133928, GSE136888, and GSE156613. To access the CRC GWAS data, researchers can refer to the dbGaP accession numbers phs001415.v1.p1, phs001315.v1.p1, phs001078.v1.p1, and phs001903.v1.p1, and additional UK Biobank resource, which can be accessed at http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk (2,5). The transcriptome and genotype data as well as the sample covariates from the BarcUVa-Seq project can be accessed using the dbGaP accession number phs003338.v1.p1.