Abstract

Background

A positive child-caregiver relationship is one of the strongest determinants of child health and development, yet many caregivers report challenges in establishing a positive relationship with their child. For over 20 years, Make the Connection® (MTC), an evidence-based parenting program, has been delivered in-person by child-caring professionals to over 120,000 parents to improve positive parenting behaviours and attitudes. Recently, MTC has been adapted into a ‘direct to caregiver’ online platform to increase scalability and accessibility. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of the online modality of MTC in increasing parenting knowledge, attitudes, and the perceived relationship with their child, and to understand barriers and facilitators to its access.

Methods

Two hundred caregivers with children aged 0-3 years old will be recruited through Public Health agencies in Ontario, Canada. Participants will be randomly placed in the intervention or waitlist control group. Both groups will complete a battery of questionnaires at study enrolment and 8 weeks later. The intervention group will receive the MTC online program during the 8-week period, while the waitlist group will receive the program after an 8-week wait. The study questionnaires will address demographic information, caregivers’ relational attitudes towards their infant, self-competence in their caregiver role, depression, and caregiver stress, as well as caregivers’ and infants’ emotion regulation.

Discussion

Results from this study will add critical knowledge to the development, scaling, and roll out of the MTC online program, thus increasing its capacity to reach a greater number of families.

Trial registration

The study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov on 15 March 2023 (NCT05770414).

Keywords: Parenting, Child-caregiver relationship, Online intervention, Caregiver attitudes, Caregiver mental health

Background

The first three years of a child's life are critical for setting the foundation for positive development across the lifespan. Indeed, research has shown that the underpinnings of emotional and behavioural regulation take place during these early years, 1 making it one of the most cost-effective times to intervene to improve child outcomes. 2 Early child development occurs in the context of the child-caregiver relationship, which has been termed the ‘engine of development’ as it represents an important influence on children's future development. 3 Consequently, the child-caregiver relationship has been identified as one of the most robust targets for improving child outcomes.4–6 A positive child-caregiver relationship starting in infancy, where the caregiver is sensitive and responsive to the child, can lay the foundation for healthy cognitive and socioemotional development into childhood.7–9 Conversely, a poor relationship puts the child at risk for poor emotional, behavioural, and developmental outcomes.10,11

For over 20 years, Strong Minds Strong Kids Psychology Canada (SMSKPC) has been training service providers to deliver a parenting skills program called Make the Connection® (MTC) to parents of the general population as well as parents at-risk for child-caregiver relationship difficulties primarily due to social factors including mental health difficulties, social isolation, poverty, and low education. 12 The program has been offered in a group-based format and delivered by child-caring professionals (e.g. public health nurses, infant mental health, and social workers). Extensive literature has demonstrated that parenting programs delivered in person are effective for improving parental responsiveness and infant regulation (i.e. sleep). 13 Other research has shown that a group-based parenting program was effective in improving parents’ sense of competence. 14 Furthermore, parenting interventions, such as a reflective parenting home visiting program, have demonstrated effectiveness in mitigating depression, anxiety, and stress among first-time mothers. 15

MTC consists of an attachment-focused, evidence-informed, training program designed to support the development of positive child-caregiver relationships by teaching parents to understand their child's cues. The overarching goal of MTC is to enhance caregiver attitudes (e.g. positive feelings towards their infant and role as a caregiver), which have been shown to be broadly associated with sensitive parenting behaviour, and in turn, secure child attachment. 13 Ultimately, by improving parenting skills and attitudes, MTC seeks to promote more optimal child-caregiver relationships. Given the strong connection between emotion and attachment, many attachment-based parenting programs aim to improve parents’ emotion regulation, subsequently influencing their child's emotion regulation. 16 This principle also applies to the MTC program.

Although MTC has been delivered to thousands of caregivers across Canada, in person delivery of the program came to a halt due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, the use of technology to deliver evidence-based parenting interventions has been identified as a critical direction for reducing barriers to access and broadly disseminating parenting interventions. 17 Internet-based parenting interventions are particularly beneficial for increasing caregivers’ access and participation. 18 In contrast to synchronous delivery where a practitioner is present, asynchronous delivery reduces the impact of inadequate bandwidth and connectivity issues, eliminates scheduling challenges, and, overall, holds greater potential for scalability. 19 It is also more accommodating for individuals living in different time zones.

In response, MTC materials were adapted to be delivered online and directly to caregivers, through the makingtheconnectionmatters.com website. Recent research has demonstrated that the online delivery of a parenting program for caregivers of children under the age of 3 years was as effective in demonstrating increases in knowledge, parenting skills, and self-reported supportive responses as an in-person delivery model. 20 A recent meta-analysis of technology-assisted parenting interventions for families experiencing social disadvantage with young children (<6 years) also found improvements in parenting behaviour and child behaviour from pre- to post-intervention. 21 While online adaptations are promising, it is unknown whether the MTC online program will lead to changes in caregiver attitudes, sense of self-competence, and caregiver stress when being delivered virtually similar in magnitude to the in-person delivery method. 12 Additionally, the potential barriers (e.g. lack of internet or device access, reduced social aspect of delivery method) and benefits of the online delivery method (e.g., increased availability in rural or smaller communities, reduced transportation and childcare challenges) to access the MTC online program within the Canadian context are unknown.

Objective

This paper describes the protocol for a randomized waitlist control trial that examines the effectiveness of the online modality of the MTC program in caregivers. The three key research questions are as follows:

Does the MTC online program result in changes in the child-caregiver relationship, caregiver self-competence, caregiver stress, caregiver depression, as well as caregiver and child emotion regulation, as compared to a waitlist control?

Are caregivers who experience psychosocial risks (e.g. elevated depression scores, social isolation) deriving similar benefits in the child-caregiver relationship, caregiver self-competence, caregiver stress, caregiver depression, as well as caregiver and child emotion regulation as caregivers who are not?

What are some of the barriers, facilitators, perceived benefits, and risks to participating in the MTC online program from the perspective of caregivers?

Methods

Design

This intervention study is designed as a randomized, waitlist controlled, superiority trial with two parallel groups: the MTC intervention group and the waitlist control group. Randomization will be performed by a member of the research team through Qualtrics using automated coding with a 1:1 allocation. Allocation concealment will be ensured, as Qualtrics will not release the randomization code until the participant has been recruited into the trial, which will occur after the screening questionnaire has been completed. Both groups will be asked to complete a self-administered, online pre-questionnaire prior to allocation to the intervention or waitlist group. The pre-questionnaire consists of questions pertaining to demographic information, caregivers’ relational attitudes towards their infant, self-competence in their caregiver role, depression, and stress, as well as caregivers’ and infants’ emotion regulation. The intervention group will be invited to complete the 8-week MTC online program immediately after allocation, and both groups will be asked to complete another self-administered, online post-questionnaire 8 weeks later. All of the measures will be administered both pre and post, except for the demographic questions and the questions to assess whether caregivers are at risk for child-caregiver relationship difficulties. Email reminders to complete the questionnaires will be sent bi-weekly to participants. At the end of the 8-week period and after the post-questionnaire is completed, the waitlist control group will have the option to receive the MTC online program if they wish. Caregivers assigned to the intervention group and having completed the MTC online program will answer an additional set of questions created by the researchers about completing the program to help us understand the barriers and facilitators to participation. These consist of five questions answered on a 5-point Likert Scale and three open-ended questions. Participants will receive a gift card to a coffee shop for their participation.

The study has been approved by the University of Ottawa Research Ethics Board (REB # H-02-23-8888) and is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05770414). This protocol paper adheres to the SPIRIT guidelines (see Supplementary material, Additional file 1).

Participants

Participants will consist of primary caregivers (i.e. primarily responsible for the child's care means that they care for the child at least 50% of the time) of children aged 3 years or younger. We aim to recruit a total of 200 caregivers to participate in the study; 100 for the intervention group and 100 for the waitlist control group. Participants’ eligibility will be confirmed by the screening questions located at the beginning of the Qualtrics survey. To be eligible for the study, they must: (1) have a child between the ages of 0-3 years; (2) be primarily responsible for the child; (3) be over 18 years of age; and (4) be able to complete the questionnaires and understand the program content in English. There are no exclusion criteria for participants in this study.

Recruitment

Participants will be recruited from EarlyON Child and Family Centres in Peel and Halton Regions, municipalities in Ontario, Canada. EarlyON Centres offer free, high-quality programs for families and children aged 0-6 years. Other recruitment sites may be added as needed. Flyers about the study will be advertised in the EarlyON Centres on the public walls and on the EarlyON website and social media. The first contact with interested families will be made by public health nurses/workers at the EarlyON centres. They will provide recruitment postcards and study information to all caregivers receiving services at the EarlyON centres with whom they interact with as part of their regular services. Peel region is a highly racially and ethnically diverse community, with 69% of people identifying with a racialized group (namely South Asian). 22 As such, the recruitment materials and strategy will consider the diverse nature of the population.

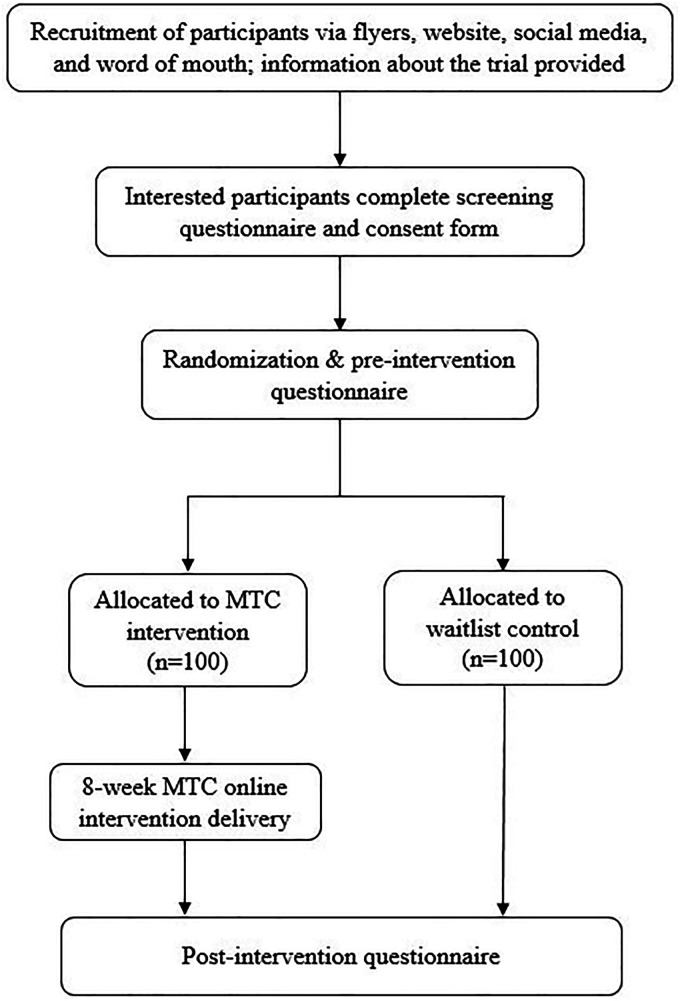

Interested participants will be asked to complete a screening questionnaire and, if eligible, will be directed to the program website for more information and to enrol in the program. The SMSKPC program administrator will provide participants with a code so that they may access the program for free. Participants will be informed of the goals and purposes of the study and that they will either receive the program right away or wait. As the program and questionnaires will be provided online, participants will be asked to indicate their consent to participate by clicking a box acknowledging that they have read the consent form and agree to participate in the study, prior to completing the pre-questionnaire. The questionnaires will be anonymous and no identifying information will be collected. See Figure 1 below for a flowchart of participant recruitment and progression through the MTC online program.

Figure 1.

Recruitment and participant flow through the study.

Several mitigation strategies have been put in place to address potential challenges with recruitment and conducting the study. First, our recruitment strategy is multi-pronged in that we will seek to recruit caregivers using several different modalities. Second, we will conduct trainings and engagement sessions with staff working at the EarlyON centres at the outset of the study to increase uptake and knowledge about the study. Third, ongoing engagement and monitoring of recruitment into the study will be conducted throughout by the study team to ensure adequate recruitment.

Intervention

The online modality of the Make the Connection® (MTC) program offered by Strong Minds Strong Kids, Psychology Canada (SMSKPC) is self-administered by caregivers and consists of 8 weekly, 15-min modules. The MTC online program can be completed via the makingtheconnectionmatters.com website using a computer, tablet, or mobile phone and does not require the involvement of a practitioner. The program comprises video presentations of eight sequenced ‘modules’ containing interactive activities, all of which are compulsory to complete the program. The MTC program also provides a toolbox with printable resources that caregivers can use outside of the training program. In order to accommodate caregivers’ busy schedules, each video contains a progress bar with times listed and participants are able to resume the program where they left-off. Given that the MTC program has been offered in person for over 20 years and presents minimal risks, there are no criteria for discontinuing or modifying the online intervention, except if the participant decides to discontinue. Participants will receive the materials weekly in sequence to avoid being overwhelmed by the material all at once. Participants will receive email reminders to access the program. Whether or not caregivers view the materials will be monitored by program administrators at SMSKPC. The administrators have the capability to track the progress and completion status of the various modules. The eight MTC modules are described in detail in the Table 1 below:

Table 1.

Description of Make the Connection® module content.

| Module | Content | Duration | Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The Secure Attachment Process | - What is secure attachment? | 4:48 | |

| - Why is secure attachment important? | 2:36 | ||

| 2. Creating a Loving Connection | - What it means to create a loving connection? | 1:09 | • Gentle tickle games |

| - Why is a loving connection important? | 5:18 | • Imitating your baby's facial expressions and sounds • Exchanging smiles or funny faces |

|

| - Thinking about the loving connections you formed as a child | 1:42 | ||

| - Amy's story: the challenges she has had while trying to form a loving connection with her baby and how she overcame them | 2:01 | ||

| - Strategies for connecting with your baby | 1:48 | ||

| - Example of a ‘hands-on’ activity that you can do with your child and a song you can sing with your child | 1:13 | ||

| - Some challenges that you may face | 2:27 | ||

| - Different ages and milestones | - | ||

| 3. Being a Secure Base | - What does it mean to be a secure base? | 1:18 | • Exploring at home with very simple items that you can find around the house |

| - Why is being a secure base important? | 0:50 | ||

| - Thinking about the secure base you had as a child | 0:59 | ||

| - Tasha's story: how she shows her baby that she is a secure base | 1:04 | ||

| - Strategies for being a secure base | 3:32 | ||

| - Example of a ‘hands-on’ activity that you can do with your child and a song you can sing with your child | 1:24 | ||

| - Some challenges that you may face | 1:19 | ||

| - Different ages and milestones | - | ||

| 4. Accepting Feelings | - What does it mean to accept feelings? | 1:27 | • Being a ‘mirror’ for your child: give them the word for what they are feeling and ‘mirror’ the feeling back to them |

| - Why is accepting feelings important? | 1:43 | ||

| - Thinking about your childhood and how accepting feelings may have affected your upbringing | 1:40 | ||

| - Nicole's story: how she accepts her son's feelings | 0:55 | ||

| - Strategies for accepting your child's feelings | 2:59 | ||

| - Example of a ‘hands-on’ activity that you can do with your child and a song you can sing with your child | 1:42 | ||

| - Some challenges that you may face | 0:37 | ||

| - Different ages and milestones | - | ||

| 5. Setting Limits with Love (ABCs) | - What does it mean to set limits with love? | 1:52 | • Set aside some time to spend with your child and focus on their good behaviour |

| - Why is setting limits with love important? | 2:00 | ||

| - Thinking about your childhood and how setting limits may have affected your upbringing | 1:17 | ||

| - Robert's story: how he sets limits for his son | 0:56 | ||

| - Strategies for setting limits with love | 1:45 | ||

| - Example of a ‘hands-on’ activity that you can do with your child and a song you can sing with your child | 1:17 | ||

| - Some challenges that you may face | 0:20 | ||

| - Different ages and milestones | - | ||

| 6. Promoting Language | - What does it mean to promote language? | 0:59 | • Sing a song for your child—slow down and pause before important words, to help them learn new words |

| - Why is promoting language important? | 2:26 | ||

| - Thinking about your childhood and how promoting language was a part of your upbringing | 1:04 | ||

| - Daniel's story: how he promotes language to his baby | 1:15 | ||

| - Strategies for promoting language | 2:59 | ||

| - Example of a ‘hands-on’ activity that you can do with your child and a song you can sing with your child | 1:45 | ||

| - Some misconceptions that some parents have about promoting language | - | ||

| - Different ages and milestones | - | ||

| 7. Having ‘Baby Conversations’ | - What does it mean to have baby conversations? | 1:45 | • Play a game of peekaboo with your child—watch how they react, respond, and continue taking turns |

| - Why are baby conversations important? | 0:50 | ||

| - Thinking about your childhood and how baby conversations were a part of your upbringing | 0:53 | ||

| - Rachel's story: how she has baby conversations with her son | 1:10 | ||

| - Strategies to have ‘baby conversations’ | 2:03 | ||

| - Example of a ‘hands-on’ activity that you can do with your child and a song you can sing with your child | 1:27 | ||

| - Some challenges that you may face | - | ||

| - Different ages and milestones | - | ||

| 8. Being a Play Partner | - What does it mean to be a play partner? | 0:53 | • Kool Kitchen: bring out kitchen items and let your baby play with them—let your child guide the play as you play along |

| - Why is being a play partner important? | 3:08 | ||

| - Thinking about your childhood and how play partners were a part of your upbringing | 1:38 | ||

| - Kayla's story: how she is a play partner to her daughter | 0:59 | ||

| - Strategies for being a play partner | 2:21 | ||

| - Example of a ‘hands-on’ activity that you can do with your child and a song you can sing with your child | 1:28 | ||

| - Some challenges that you may face | 0:35 | ||

| - Different ages and milestones | - |

Measures

The following primary outcome measures will be completed as self-report scales by caregivers in both groups at pre-intervention and post-intervention 8 weeks later to evaluate the effectiveness of the MTC online program. The study questionnaires will also contain a series of items to assess whether caregivers are at-risk for child-caregiver relationship difficulties (e.g. <25 years of age, single-parenthood, depressed mood, less than high school education, social isolation) in order to identify if caregivers at-risk experience similar changes in outcomes. The same measures have been used in previous evaluations of MTC 12 and as such, we will be able to examine whether similar changes are occurring for in-person versus online delivery of the program.

Child-caregiver relationship

To assess the caregiver's perception of their relationship with their child, caregivers will complete the Maternal Postnatal Attachment Scale (MPAS 23 ), which is a 19-item questionnaire that assesses caregivers’ relational attitudes towards their infant. Refinements to the original questionnaire have yielded three robust subscales: Quality of Attachment, Pleasure in Interaction, and Absence of Hostility. The MPAS has shown good psychometric properties 23 and has been used in community samples. 24

Parent self-competence

To assess parent self-competence, caregivers will complete the Parent Sense of Competence Scale, 25 which has 17 items and measures a caregiver's experiences in their caregiving role. The PSOC has three subscales including Interest, Efficacy, and Satisfaction.

Parenting stress

Parenting stress will be evaluated using the Parental Stress Scale (PSS). 26 The PSS assesses both positive and negative perceptions and feelings associated with being a parent. The PSS has been widely used and has been found to have strong psychometric properties. 24

Parental depression

Parental depression will be assessed using the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). 27 The CES-D contains 20 items and requires individuals to rate how often they experienced symptoms of depression over the past week. This scale has demonstrated good reliability and validity. 28

Emotion regulation

Caregivers’ emotion regulation will be assessed using three items from the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. 29 Infant emotion regulation will be assessed from two items from the Ages & stages questionnaire: Social-Emotional, Second Edition (ASQ-SE). 30

Barriers and facilitators to participation

Caregivers assigned to the intervention group will answer an additional set of questions to identify barriers and facilitators to participation. These consist of five questions answered on a 5-point Likert Scale on knowledge and outcomes related to the program. Three open-ended questions address what caregivers liked, found challenging, and what they would change about the program.

Statistical analyses

All study data will be automatically collected using Qualtrics and stored within their secure server. Members of the research team will then export the data from the server to proceed with analysis. For the first research question, linear mixed models will be used to model the change in the primary outcomes from baseline to follow-up for the intervention and waitlist control groups, controlling for demographic variables that potentially differ at baseline (e.g. caregiver age, education, marital status, socioeconomic status, and child age). Linear mixed models can accommodate participants with missing observations. 31 For the third research question, participants’ responses will be examined qualitatively and described narratively. All participants will be asked the questions relating to psychosocial risks. During the analyses, we will use their scores to compare outcomes depending on if they were at-risk or not. A data monitoring committee with three individuals with expertise in statistics, psychological interventions, and clinical service delivery will be established to monitor the data collection and decision making throughout the study. Given that participant recruitment is done on an ongoing basis and the estimated project duration is one year, meetings will be held every three months to review data and provide consultation on continuation of the study and data analysis.

Sample size and power calculations

The study is powered to detect a medium between-group effect size of Cohen's d = 0.50 in the primary outcome (change in perceived bond with their child). This estimated effect size maps on to previous research examining the effect of the MTC program. 12 Using G*Power v3.1.9.7, 32 assuming a two-sided two-sample t-test with un-pooled variance, we estimate that N = 176 participants will be required (n = 68 per group). Assuming ∼30% participant attrition, 33 a sample size of N = 100 participants per group will be sufficient to detect a difference in the primary outcome. Participants who complete at least 50% of the modules will be included in the analyses. Post-hoc analyses will be conducted to examine whether individuals who complete less than 50% of the program demonstrate any benefits of the intervention.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has received approval from the University of Ottawa Research Ethics Board (REB # H-02-23-8888). All of the participants enrolled in the trial will be required to read and accept the electronic consent form (see Supplemental material, Additional file 2) provided through Qualtrics (participants will select ‘Yes, I want to participate’). It is important to note that study data will only be collected from participants once they have provided consent. The data collected through the study questionnaires using Qualtrics will be kept in a secure manner. The data will automatically be collected using the secure Qualtrics software and will be stored within the server. Investigators on the research team will have access to the final dataset, as well as research assistants working within the labs of the investigators. The study data will be used to write scientific publications and disseminate findings to the general audience. The authors will consist of members of the research team who have made significant contributions to the study design, data collection and analysis, and manuscript writing. Any protocol modifications will be updated on the clinical trial public register and reported to the REB.

Discussion

Online psychological interventions represent an innovative avenue of care that may reduce barriers to access for parents and caregivers. Important advantages of online delivery for caregivers include greater access to treatment, reduced practical requirements (e.g. booking time off, arranging childcare, etc.), as well as reduced travel and associated costs. These can be particularly beneficial for caregivers experiencing social inequalities due to mental illness, financial precariousness, or social isolation. 21 Online parenting interventions delivered to child-caregiver dyads exposed to social risks have the potential to improve both caregiver and child outcomes. 21 In this context, the present study protocol describes a randomized waitlist control trial aiming to test the effectiveness of the online modality of the MTC program in a sample of caregivers of infants and young children. By comparing the intervention and waitlist control groups, we will establish whether the MTC online program results in improved child-caregiver bond, caregiver self-competence, caregiver stress, caregiver depression, and caregiver and infant emotion regulation.

The most important strength of the study is its randomized controlled design. This study design reduces the risk of bias and allows us to attribute any differences in scores to the MTC program, thus sharing reliable conclusions about its effectiveness. There is currently a lack of evidence on the effectiveness of self-guided parenting programs and this study will provide important information for the dissemination of the MTC program to both caregivers at-risk and not at risk of social difficulties. Lastly, we employ a small number of assessment instruments to reduce the burden on our participants. Naturally, there are a few limitations to the study that should be noted. First, the absence of a subsequent follow-up measure (e.g. a 3-month post-intervention follow-up) prevents us from determining whether the effects of the MTC online program are maintained over time. Second, the sole use of self-report measures presents a risk of bias; however, this choice was justified by the fact that the MTC online program is a self-administered intervention with no practitioner involvement. Moreover, caregivers of young children typically have busy schedules. Conducting face-to-face data collection would likely require them to take time off work, arrange childcare, and plan for travel, among other logistical challenges. These obstacles could minimize the chances of obtaining data. Additionally, certain self-report measures (e.g. the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 scale) are widely regarded as the gold standard for assessing mental health symptoms. Research has shown that providing anonymity tends to elicit more truthful responses, particularly in the context of mental health assessments. 34 Third, caregivers who are at-risk for parent-child relationship difficulties may be harder to reach and more reluctant to participate in research, given the social and emotional challenges that they face.

Identifying whether the online adaptation of the MTC program has positive benefits for caregivers and their infants will provide evidence for large-scale dissemination in the Canadian context. Furthermore, by collecting information from caregivers directly about the barriers, facilitators, perceived benefits, and risks to participating in the online program, the online program can be refined and improved to better suit the needs of caregivers. Results from this partnership project will add critical knowledge to the development, scaling, and roll out of the online MTC program, thus increasing its capacity to reach a greater number of families. From a broader perspective, the online delivery of parenting resources has the potential to transform the access to and availability of resources for parents across Canada.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-doc-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076231221053 for A randomized waitlist control trial of the Make the Connection® online program for caregivers of infants and young children: Study protocol by Sophie Barriault, Audrey-Ann Deneault, Samantha Kempe, Sheri Madigan, Anne Lovegrove, Gina Dimitropoulos, Rebecca Pillai Riddell and Nicole Racine in DIGITAL HEALTH

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-dhj-10.1177_20552076231221053 for A randomized waitlist control trial of the Make the Connection® online program for caregivers of infants and young children: Study protocol by Sophie Barriault, Audrey-Ann Deneault, Samantha Kempe, Sheri Madigan, Anne Lovegrove, Gina Dimitropoulos, Rebecca Pillai Riddell and Nicole Racine in DIGITAL HEALTH

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the staff at Strong Minds Strong Kids, Psychology Foundation of Canada for their support in the project.

Footnotes

Contributorship: AAD, SM, AL, GD, RPR, and NR conceived the study and are co-investigators. SB and SK were involved in obtaining ethical approval and contributed to writing the protocol. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved its final version.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: All participants will provide informed consent prior to participation. Ethics approval was received from the University of Ottawa Research Ethics Board (REB # H-02-23-8888).

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, (grant number 892-2022-1055).

Guarantor: NR

ORCID iDs: Sophie Barriault https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3347-1055

Nicole Racine https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6371-6570

Trial sponsor: University of Ottawa

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Calkins S, Hill A. Caregiver influences on emerging emotion regulation: biological and environmental transactions in early development. In: Gross J. (ed) Handbook of emotion regulation. New York, USA: Guilford Press, 2007, pp. 229–248. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doyle O, Harmon CP, Heckman JJ, et al. Investing in early human development: timing and economic efficiency. Econ Hum Biol 2009; 7: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ainsworth M. Infant-mother attachment. Am Psychol 1979; 34: 932–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barlow J, Bennett C, Midgley N, et al. Parent-infant psychotherapy for improving parental and infant mental health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; 2015: CD010534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaminski JW, Valle LA, Filene JH, et al. A meta-analytic review of components associated with parent training program effectiveness. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2008; 36: 567–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris AS, Robinson LR, Hays-Grudo J, et al. Targeting parenting in early childhood: a public health approach to improve outcomes for children living in poverty. Child Dev 2017; 88: 388–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madigan S, Atkinson L, Laurin K, et al. Attachment and internalizing behavior in early childhood: a meta-analysis. Dev Psychol 2013; 49: 672–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van IJzendoorn M DJ, Bus A. Attachment, intelligence, and language: a meta-analysis. Social Development 1995; 4: 115–128. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deneault AA, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Groh AM, et al. Child-father attachment in early childhood and behavior problems: a meta-analysis. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev 2021; 2021: 43–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bailes LG, Leerkes EM. Maternal personality predicts insensitive parenting: effects through causal attributions about infant distress. J Appl Dev Psychol 2021; 72: 101222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ward KP, Lee SJ. Mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress, responsiveness, and child wellbeing among low-income families. Child Youth Serv Rev 2020; 116: 105218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Neill A, Swigger K, Kuhlmeier V. 'Make the connection' parenting skills programme: a controlled trial of associated improvement in maternal attitudes. J Reprod Infant Psychol 2018; 36: 536–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mihelic M, Morawska A, Filus A. Effects of early parenting interventions on parents and infants: a meta-analytic review. J Child Fam Stud 2017; 26: 1507–1526. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchanan-Pascall S, Melvin GA, Gordon MS, et al. Evaluating the effect of parent-child interactive groups in a school-based parent training program: parenting behavior, parenting stress and sense of competence. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2023; 54: 692–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vismara L, Sechi C, Lucarelli L. Reflective parenting home visiting program: a longitudinal study on the effects upon depression, anxiety and parenting stress in first-time mothers. Heliyon 2020; 6: e04292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hajal NJ, Paley B. Parental emotion and emotion regulation: a critical target of study for research and intervention to promote child emotion socialization. Dev Psychol 2020; 56: 403–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weisenmuller C, Hilton D. Barriers to access, implementation, and utilization of parenting interventions: considerations for research and clinical applications. Am Psychol 2021; 76: 104–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Novianti R, Rusandi MA, Situmorang DD, et al. Internet-based parenting intervention: a systematic review. Heliyon 2023; 9: e14671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yellowlees PM, Parish MB, Gonzalez AD, et al. Clinical outcomes of asynchronous versus synchronous telepsychiatry in primary care: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2021; 23: e24047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brophy-Herb HE, Moyses K, Shrier C, et al. A pilot evaluation of the building early emotional skills (BEES) curriculum in face-to-face and online formats. J Community Psychol 2021; 49: 1505–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris M, Andrews K, Gonzalez A, et al. Technology-Assisted parenting interventions for families experiencing social disadvantage: a meta-analysis. Prev Sci 2020; 21: 714–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Region of Peel. Ethnic Diversity and Religion: Peel's Diver community in 2021, https://census-regionofpeel.hub.arcgis.com/pages/ethnic-diversity-and-religion-2021 (2023, accessed 13 December 2023).

- 23.Condon JT, Corkindale CJ. The assessment of parent-to-infant attachment: development of a self-report questionnaire instrument. J Reprod Infant Psychol 1998; 16: 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rossen L, Hutchinson D, Wilson J, et al. Predictors of postnatal mother-infant bonding: the role of antenatal bonding, maternal substance use and mental health. Arch Womens Ment Health 2016; 19: 609–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilmore L, Cuskelly M. Factor structure of the parenting sense of competence scale using a normative sample. Child Care Health Dev 2009; 35: 48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berry J. JW. The parental stress scale: initial psychometric evidence. J Soc Pers Relat 1995; 12: 463–472. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1977; 1: 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knight RG, Williams S, McGee R, et al. Psychometric properties of the centre for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D) in a sample of women in middle life. Behav Res Ther 1997; 35: 373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2004; 26: 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Squires J, Bricker D, Twombly E. Ages & stages questionnaires®: social-emotional, Second Edition (ASQ®:SE-2): A parent-completed child monitoring system for social-emotional behaviors. Baltimore, USA: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Company, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diggle P, Heagerty P, Lian K, et al. Analysis of Longitudinal Data, 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faul E, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, et al. G*power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007; 39: 175–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lowell DI, Carter AS, Godoy L, et al. A randomized controlled trial of child FIRST: a comprehensive home-based intervention translating research into early childhood practice. Child Dev 2011; 82: 193–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warner CH, Appenzeller GN, Grieger T, et al. Importance of anonymity to encourage honest reporting in mental health screening after combat deployment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011;68:1065–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-doc-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076231221053 for A randomized waitlist control trial of the Make the Connection® online program for caregivers of infants and young children: Study protocol by Sophie Barriault, Audrey-Ann Deneault, Samantha Kempe, Sheri Madigan, Anne Lovegrove, Gina Dimitropoulos, Rebecca Pillai Riddell and Nicole Racine in DIGITAL HEALTH

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-dhj-10.1177_20552076231221053 for A randomized waitlist control trial of the Make the Connection® online program for caregivers of infants and young children: Study protocol by Sophie Barriault, Audrey-Ann Deneault, Samantha Kempe, Sheri Madigan, Anne Lovegrove, Gina Dimitropoulos, Rebecca Pillai Riddell and Nicole Racine in DIGITAL HEALTH