Abstract

Purpose:

Every year, nearly 100,000 adolescents and young adults (15–39 years, AYAs) are diagnosed with cancer in the United States and many have unmet physical, psychosocial, and practical needs during and after cancer treatment. In response to demands for improved cancer care delivery for this population, specialized AYA cancer programs have emerged across the country. However, cancer centers face multilevel barriers to developing and implementing AYA cancer programs and would benefit from more robust guidance on how to approach AYA program development.

Methods:

To contribute to this guidance, we describe the development of an AYA cancer program at the University of North Carolina (UNC) Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Results:

We summarize the evolution of UNC's AYA Cancer Program since it was established in 2015, offering pragmatic strategies for developing, implementing, and sustaining AYA cancer programs.

Conclusion:

The development of the UNC AYA Cancer Program since 2015 has generated many lessons learned that we hope may be informative to other cancer centers seeking to build specialized services for AYAs.

Keywords: AYA oncology, AYA program development, AYA cancer care, comprehensive AYA cancer program

Background

Every year, nearly 100,000 adolescents and young adults (AYAs) (15–39 years) are diagnosed with cancer in the United States (prevalence of 700,0001), and many have unmet physical, psychosocial, and practical needs during and after cancer treatment.2–7 This leads to poorer cancer care experiences and, historically, AYAs' survival gains have lagged behind those for children and older adults.8–11 Unique cancer biology, low clinical trial enrollment, suboptimal treatment adherence, and barriers in access to age-appropriate care all likely contribute to the lack of progress. Until recently, AYAs have occupied a “no-man's land” between pediatric oncology and medical oncology,12 often reporting that existing programs and services are misaligned with their needs and preferences.13–15 Indeed, to ensure high-quality care and improved outcomes, AYAs require novel models of care based on their unique developmental stage and needs.

Demands for improvements in cancer care for this population16–18 have ignited an AYA oncology movement.19 Consequently, programs providing specialized care to AYAs have emerged across the United States. These programs help bridge the gap between the unique needs of AYAs and a system not designed for them.20 Early data suggest that the availability of specialized AYA care has been associated with increased clinical trial enrollment,21 reduced unmet needs,22 and the provision of guideline-concordant care.23 However, cancer centers face multilevel barriers to developing and implementing AYA cancer programs and would benefit from more robust guidance on how to approach AYA program development.24

To contribute to this guidance, we describe the development of an AYA cancer program at the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center (UNC Lineberger). The UNC AYA Cancer Program aims to provide developmentally appropriate, transdisciplinary care for patients aged 13–39 years diagnosed with cancer, advance research in the field of AYA oncology, educate providers about the unique needs of young people living with cancer, and improve care for AYAs across North Carolina (NC). In developing a specialized program to achieve these objectives, we have learned several key lessons (Table 4) that we believe are broadly applicable to other cancer care centers seeking to improve care delivery for AYAs.

Table 4.

Recommendations for Adolescent and Young Adult Program Development

| Getting started | |

|---|---|

| Conduct community and institutional needs assessments | Start slow, getting to know institution's needs and constraints. Catalog existing services and resources for AYAs including those in-house as well as those available through community partnerships. Identify institutional strengths that can be leveraged for AYA program development, as well as existing gaps in AYA care delivery. Ask AYA patients and family members about their priorities for AYA care. |

| Establish mission and model of care | Build a bridge between pediatric and adult oncology by involving representation from both. Talk to other AYA programs to get ideas about potential models of care. |

| Take a phased-in approach to program development | Consider starting with an area of particular need, a circumscribed age range, specific disease group, or specific domain of care, and building program capacity over time. This will help establish early wins to build momentum and culture change. |

| Engaging key individuals | |

|---|---|

| Keep the patient voice central |

Establish a patient advisory board. Facilitate communication between patients and providers. Use the patient voice to motivate all program developments. |

| Engage providers |

Interview providers serving AYAs on how to work collaboratively and maximize their impact. Engage providers from both pediatric and adult oncology and from across disciplines and disease group clinics. |

| Build leadership buy-in |

Establish a clear plan before proposing AYA program development to leadership. Present leaders with a strategic plan in which AYA program priorities are aligned with institutional priorities. |

| Identify AYA champions |

Identify formal AYA champions (e.g., program director, medical director). Identify informal AYA champions across disease groups to promote referrals to AYA program. Build community partnerships. |

| Generate culture change | Provide continuous opportunities for education on the unique needs of AYAs. |

| Building the team | |

|---|---|

| Build AYA-specific staff over time |

Start with a program director. Use patient experiences to inform staffing growth with the ultimate goal of building a multidisciplinary or transdisciplinary team. Allow specific institutional needs guide program staff growth |

| Get creative with funding sources | Seek philanthropic and grant funding; demonstrate program's success to garner institutional support over time. |

| Evaluating and adapting | |

|---|---|

| Formalize metrics for program evaluation | Work with researchers, including those with health outcomes research expertise, to identify or develop metrics for program evaluation. While exploring formalized metrics, engage in more informal ongoing process of soliciting feedback and refining program priorities and activities accordingly. |

The Landscape at UNC Lineberger

UNC Lineberger is NC's only public National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center and serves patients from all 100 NC counties, including patients with a wide range of social, demographic, and economic backgrounds. Approximately 400 AYAs are newly diagnosed annually and receive care at either the NC Basnight Cancer Hospital or the NC Children's Hospital, clinical partners of UNC Lineberger (Table 1). About 10% of AYAs seen at UNC Lineberger are teens, 30% are emerging adults (20s), and 60% are young adults (30s). Inpatient oncology units and outpatient clinics for pediatric and adult patients are in adjoining buildings, enabling close interaction between pediatric and adult oncology providers. Twenty percent of AYAs treated at UNC Lineberger have public health insurance and 12% are uninsured. The majority (58%) identify as non-Hispanic White, 22% as non-Hispanic Black, and 14% as Latinx.25 Only ∼36% of AYAs served at UNC Lineberger are local to the greater Triangle area (i.e., the geographic area surrounding UNC Lineberger).

Table 1.

Description of Adolescent and Young Adults Diagnosed and Treated with Cancer at University of North Carolina Medical Center Over a 4-Year Window from 2014 to 2018

| Total, N = 1574 |

||

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Age at diagnosis, years | ||

| 15–19 | 131 | 8 |

| 20–24 | 178 | 11 |

| 25–29 | 270 | 17 |

| 30–34 | 417 | 27 |

| 35–39 | 578 | 37 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 923 | 59 |

| Male | 651 | 41 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 974 | 64 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 313 | 21 |

| Hispanic | 140 | 9 |

| Non-Hispanic other | 93 | 6 |

| Health insurance | ||

| Private | 968 | 62 |

| Public | 303 | 19 |

| Military | 109 | 7 |

| Uninsured/self-pay | 194 | 12 |

| Cancer stage | ||

| In situ | 56 | 4 |

| Local | 705 | 46 |

| Regional | 427 | 28 |

| Distant | 339 | 22 |

| Cancer site | ||

| Breast | 169 | 11 |

| Gynecologic | 220 | 14 |

| Testicular | 86 | 6 |

| CNS | 84 | 5 |

| GI | 131 | 8 |

| Head/neck/lung | 82 | 5 |

| Leukemia | 146 | 9 |

| Lymphoma | 125 | 8 |

| Sarcoma | 85 | 5 |

| Skin | 253 | 16 |

| Thyroid | 124 | 8 |

| Other | 69 | 5 |

CNS, central nervous system; GI, gastrointestinal.

Letting the Patient Voice Lead

In 2013, a high school freshman named Sophie Steiner was diagnosed with an advanced ovarian germ cell cancer and underwent treatment at the NC Children's Hospital. She and her family recognized that, although she received excellent medical care, the system was not designed to deliver high-quality specialized care for people of her age. She witnessed many adolescents without access to robust support and resources that were responsive to their unique needs as teens. Before she died, Sophie expressed a wish to help other young cancer patients maintain their dignity, identity, and independence throughout cancer treatment. In her honor, Sophie's family established the Be Loud! Sophie Foundation that sparked the development of the UNC AYA Cancer Program.

Sophie's family researched how to improve AYA cancer care by speaking with local and national leaders about the unique needs of this age group. Given the heterogeneity of AYAs and their range of needs, the foundation worked with a diverse group of relevant individuals (e.g., patient advocates, administrators, social workers, mental health providers, pediatric and adult oncology providers, nurses, and child life specialists) to establish the AYA program at UNC. Many remain engaged in this work and provide guidance on the Be Loud! Sophie Foundation Board of Directors. This partnership between an academic institution and a local nonprofit philanthropic organization has enabled our program to occupy a cross-cutting, transdisciplinary space, which has been key for our success.

In keeping with Sophie's influence, the patient voice and experience remain central to all UNC AYA Cancer Program activities and development. Much as Sophie's vision inspired the establishment of our program, feedback from individual AYAs we serve has inspired many program developments including the creation of a sarcoma-palliative care-AYA collaborative, the creation of an AYA-specific infusion space, and the decision to develop an AYA survivorship clinic at a site outside of the cancer hospital. To formalize patient engagement, we created an AYA Advisory Board comprised mostly of young adult survivors. We hold monthly virtual meetings with the Advisory Board focused on quality improvement, research, and program growth and development. In addition to this more formal feedback, we also solicit continual feedback from our clinical interactions with AYAs as they navigate an ever-changing health care system and world. The ability to pivot and adjust as a program to meet their needs within the context of a specific health care system is critical.

Starting Small

The Be Loud! board identified a key initial commitment to improve AYA cancer care—hiring a full-time AYA advocate to realize Sophie's vision for age-appropriate cancer care. In 2015, the UNC AYA Cancer Program was established by hiring a Licensed Clinical Social Worker (LCSW)-trained AYA Program Director (L.L.). A clinician with a social work background was well suited to the Director role, given their expertise in both individual- and system-level approaches. This dual expertise—a product of their social work training—allowed L.L. to begin working with patients immediately using their clinical skills while, at the same time, synthesizing their clinical experiences and interactions with staff to begin conceptualizing broader system-level changes that would benefit UNCs AYA Cancer Program and AYA population.

L.L.'s position is housed in UNC Lineberger's Comprehensive Cancer Support Program (CCSP), a cross-disciplinary program with ties to both adult and pediatric oncology. They report to the head of CCSP, a psychiatrist. Initially, L.L. dedicated ∼80% of their time to clinical activities and 20% to program development activities. Clinical efforts focused on providing 1:1 counseling, psychosocial support, and resources to address the burden of cancer treatment on AYAs. This provided early successes for our program in addressing AYAs' psychosocial needs and connecting them to resources and, through these relatively quick wins, demonstrating the program's value to providers. However, to expand the program beyond these initial activities, additional groundwork needed to be laid. In terms of program development activities, limited bandwidth required a tight focus, and L.L.'s early efforts targeted two key tasks: (1) conducting a community and institutional needs assessment and (2) establishing a mission and model of care.

Community and institutional needs assessment

A critical first step in developing an AYA cancer program is to understand the community of AYAs and caregivers served and the structure of the health care system in which the AYA program will operate. Our initial steps included identifying community and institutional needs and constraints, strengths, and weaknesses of existing AYA care, available resources with potential applications to AYA care, and key collaborators to engage in program development. As an AYA program grows and health care systems evolve, undoubtedly more and different needs will be identified requiring iterative reprioritization. In Table 2, we have offered some guidance for conducting this kind of community and institutional needs assessment.

Table 2.

Questions to Consider When Conducting a Community and Institutional Needs Assessment

| Question | Information to gather |

|---|---|

| Who are the AYAs being served? | • Number entering health system each year • Description of AYA population in terms of gender, age, race, ethnicity, cancer type, and socioeconomic status |

| How are AYAs being cared for currently? What existing institutional and/or provider strengths and resources can be leveraged? |

• Where do AYAs receive care? ○ Which disease group clinics? ○ Pediatric vs. adult oncology? ○ Inpatient vs. outpatient oncology? • List of services and resources available to AYAs in-house or through community partnerships including: ○ AYA-specific services and resources ○ Broader services and resources that could be leveraged for AYA population • List of any projects or initiatives specific to AYA population or provider education on the needs of this population |

| What are the major gaps in AYA care? | • Informed by expert consensus and guidelines for essential elements of high-quality AYA cancer care,17,40 what domains of care and resources are limited or unavailable with our health system? (e.g., treatment options, symptom management, fertility, sexual health, psychosocial care, survivorship care, end-of-life care, educational and vocational support) • What are the barriers that AYAs face in accessing existing services and resources? • What are the priorities of patients and caregivers with respect to AYA services and resources? |

| Who are the key individuals to involve? | • Which providers, staff, and other individuals are interfacing with AYA patients? • Which institutional leaders need to buy in to AYA program development? • Are there individuals within the institution who are particularly passionate about AYA care? |

AYA, Adolescent and Young Adult.

To assess the needs of our community and our institution, we performed informal interviews inside and outside our system to assess these criteria. For example, we interviewed providers across disease groups and disciplines (e.g., oncologists, navigators, nurses, physical therapists, social workers, pharmacists) who interface with AYA patients, soliciting feedback about how to improve AYA cancer care. In addition to better defining the institutional landscape, these interviews built a network for collaborative relationships and served to educate providers on AYA care. This supported our goal of building a culture cognizant of the unique needs of AYAs at our institution. Our community and institutional needs assessment yielded important insights on both provider and staff needs (e.g., education on how to provide age-appropriate care particularly for trainees, additional multidisciplinary support to fill gaps in care, AYA research collaborations) as well as patient and family needs (e.g., psychosocial support, support for young caregivers, connection to palliative care, education and vocational support).

Mission and model of care

Our guiding principle has been to improve quality of life and treatment-related outcomes for AYAs at UNC Lineberger. In our program's mission, we sought to reflect the three pillars of UNC Health's broader mission (excellence in clinical care, research, and education/advocacy), adapted to AYAs' unique needs. This alignment of goals increased institutional and leadership buy-in for our program. Ultimately, we chose the following mission statement: The UNC AYA Cancer Program provides age-appropriate psychosocial and medical care for AYA cancer patients and their support communities, advances research in the field of AYA oncology, educates providers about the unique needs of young people living with cancer, and improves care for AYAs across the state of NC.

As we crafted our model of care, based on our mission and the institutional needs we identified, we sought input from colleagues at other institutions and guidance from the existing literature.20,26,27 A pivotal early decision was where to embed our program—most operate from within adult or pediatric oncology departments. We opted to house the UNC AYA Cancer Program in CCSP, because of CCSPs ties to both adult and pediatric oncology. The CCSP is focused on providing supportive care across all phases of the cancer treatment experience. This strategic choice aligned well with our vision for multispecialty, collaborative care for AYAs. We chose a consultation-based model, allowing AYA-focused services to be available across disease groups and settings. Our initial consult service spanned inpatient and outpatient settings, and pediatric and medical oncology. The initial consult team included just L.L. With no formalized referral mechanism in place yet, L.L. scanned inpatient and clinic lists to identify AYA patients and visited them through impromptu encounters in the inpatient unit, outpatient clinic, or outpatient infusion space. Although “AYA” is most commonly defined as ages 15–39 years, we initially offered universal consultation to patients aged 13–30 years, with clear definitions around the scope of our services. The choice to include both adolescents and young adults enabled a broader footprint in the cancer center and aligned with our bridge-building vision. We opted to define our lower cutoff as 13, rather than 15, because Sophie was 13 when she was diagnosed. We defined the upper cutoff as 30 due to staff bandwidth and resource constraints, knowing that we would later expand our age range up to 39. Other centers may choose to focus initially on a particular disease group or age range, but as with our program, these models of care will likely evolve as the needs and constraints of AYA care become clearer within a given institution.

Interested parties may have competing ideas about program priorities given their respective disciplines or perspectives. Harmonizing these viewpoints to create a mission and model of care aligned with findings from the institutional and community needs assessment can be challenging. For example, the fertility preservation group at UNC Lineberger was very interested in L.L.'s entire clinical role being dedicated to fertility preservation. Others had strong opinions that creating support groups should be the immediate focus of the program. Although these aspects of care would eventually be integrated into program activities, the decision was made to for L.L.'s clinical activities to focus initially on direct patient care.

Changing the Culture

Fostering an institutional culture that understands and values the unique approach needed for AYA cancer care is essential for a successful AYA program. Culture change can be difficult but grows from facilitating communication and collaboration internally and externally, educating providers on AYAs' unique needs, demonstrating added value derived from meeting those needs, and identifying AYA champions across departments. The AYA team alone cannot address the needs of all AYAs. Establishing robust referral networks and collaboration among disciplines is critical to meeting the full scope of AYAs' needs. Ideally, all providers in a cancer center would have the knowledge, skills, and resources needed to tailor care for AYAs. AYA programs can be catalysts for such broad and lasting culture change.

Build leadership buy-in

To garner administrative, financial, and structural support, institutional leaders must be engaged in efforts to provide specialized AYA care. Several factors contributed to the relatively high level of initial support from leaders at UNC Lineberger. For example, the Director of UNC Lineberger is highly invested in supportive oncology, understanding that designation as a comprehensive cancer center requires the provision of comprehensive services to patients. Additionally, with a strong Internal Medicine–Pediatrics Program, there was already a culture of collaboration and relationships between the division heads on the pediatric and adult sides.

Even with strong initial support, we have still deployed several strategies to further build leadership buy-in. First, we recommend establishing a clear plan before proposing AYA program development to leadership; presenting leadership with a strategic plan that is aligned with institutional priorities facilitates buy-in. For example, we emphasized a strong focus on increasing clinical trial enrollment because we recognized this as priority to the institution for maintaining designation as a comprehensive cancer center in addition to being a priority for the AYA population. The strategic plan should identify core values, clearly defined areas for improvement, and action items with short-term and long-term objectives, while allowing for flexibility to capitalize on unexpected opportunities.

Second, we recommend obtaining philanthropic funds (e.g., Teen Cancer America grants) and using those funds to quickly address “low-hanging fruit” and make impacts on patient care. As oncology providers witness these immediate enhancements in AYA care and the response from patients, the culture will shift and support for the AYA Program's activities will grow across campus, snowballing into greater support at the leadership level. Finally, we recommend leveraging patient and caregiver advocacy to build leadership support. For example, our AYA team worked in tandem with community supporters such as the Be Loud! Sophie Foundation to continue to amplify patient and family stories, which highlighted the need for and success of this work. Inspired by these stories, additional cancer center and hospital leaders sought ways to support the UNC AYA Program.

Investing time to meet with institutional leaders was critical to educate them on the unique needs of AYAs with cancer, share stories of the impact made by AYA-focused work, and involve them in program successes. At UNC Lineberger, this has established a team of key allies who have a broad vision for the institution's future and who are poised to capitalize on opportunities for growth and advancement as they arise. For example, because of leadership support, we were able to secure space for an AYA infusion center during planned hospital renovations. Leadership buy-in has also allowed us to develop innovative partnerships to support cross-discipline resources such as hiring an AYA Nurse Practitioner with a focus on clinical trial enrollment and securing a portion of effort for a Fertility Preservation Social Worker.

Identify AYA champions

Identifying champions is key to support improvement and implementation efforts across health care.28 Champions can advocate for program resources, promote tailored evidence-based clinical care, educate and motivate staff, and support program expansion. Indeed, the success of our program has relied on fostering and encouraging collaboration with AYA champions, both formal and informal. These individuals can influence AYA cancer care in day-to-day clinical activities (e.g., choice of treatment regimens, support for clinical trial participation, provision of fertility preservation counseling, facilitating early referrals for psychosocial support) and institutional activities (e.g., representing AYA interests on hospital committees and identifying institutional strengths that can be leveraged to enhance AYA care).

Identifying champions across various disease groups and disciplines has helped to grow our program and broaden our reach and impact. For example, our program benefited from strong advocacy from key personnel in pediatric oncology, leukemia and lymphoma, sarcoma, and testicular cancers (common AYA diseases). Establishing these champions in the disease groups where we treated the largest numbers of AYAs was key for promoting referrals to the program. Other AYA champions have also played a critical role. For example, after working closely with the AYA team on several AYA cases, a geriatric palliative care physician saw the value of specialized AYA care. This physician became a huge proponent of specialized palliative care for AYAs and their advocacy led to the addition of an AYA-specific Palliative Care Physician to our AYA team. Our AYA champion in the development office represents another example: this individual has become intimately familiar with the AYA team's work and has been instrumental in sharing our contributions and stories with potential donors. Importantly, informal champions can cultivate culture change to support tailored AYA care, enhancing the efforts of those with official program roles.

Building the Team

In addition to complex physical and medical needs (e.g., treatment-related adverse effects, functional impairments limiting activities of daily living, fertility concerns),4 AYAs' ability to cope with and manage their disease is affected by age-specific issues related to family dynamics,29 peer engagement,30 sexuality,31 body image,32 educational and vocational needs,33 financial issues,34 and extensive information needs.35 Because of the multifaceted nature of AYAs' needs, a transdisciplinary approach is central to our model of cancer care. Transdisciplinary care leverages expertise and knowledge from across various disciplines (e.g., medical, nursing, social work), and decision-making is shared among all team members.36 An effective transdisciplinary team is rooted in collaboration, trust, and ensuring that all voices are elevated.

Many cancer programs may not be able to support a full-time AYA dedicated staff member at the outset, much less an entire transdisciplinary team. Instead, most will build AYA-specific staff over time or leverage existing staff, with effort divided between the AYA program and home departments.37 AYA-focused effort may then increase with growing interest or responsibilities. There is often ambiguity in new AYA-specific roles, so transparency around this uncertainty is important. Key traits of individuals suited to this type of role include flexibility, passion for AYA care, organizational and communication skills, and the ability to juggle various tasks and priorities.

Build AYA team over time

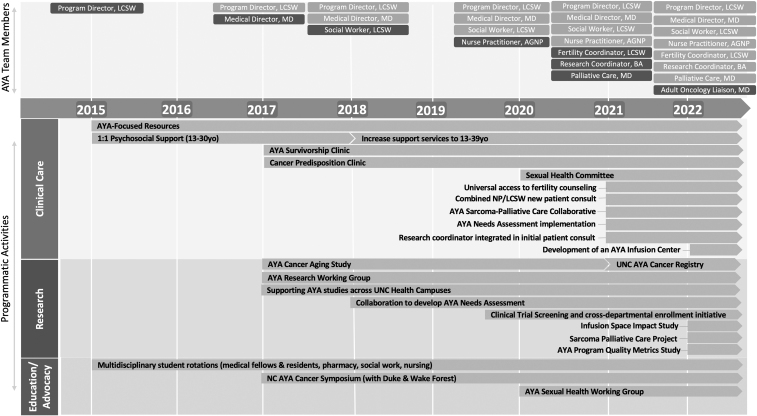

At UNC Lineberger, we have built our transdisciplinary team over several years, allowing us to expand program activities related to clinical care, research, and education/advocacy (Fig. 1). Early on, we recognized that the psychosocial expertise of our LCSW Director would be well complemented by a medical counterpart. Thus, supported by a Teen Cancer America grant, we hired an AYA Medical Director (A.B.S.). We chose a pediatric oncologist with training in general pediatrics and internal medicine, allowing us to leverage existing relationships across pediatric and medical oncology. This enhanced research efforts, including increased attention to AYA clinical trial enrollment and the development of an AYA Research Working Group. This Working Group highlights AYA-focused research at UNC and connects researchers and clinicians across the health campuses. To support broader collaborations across the region and state, we established an annual NC AYA Cancer Symposium with the support of colleagues at Duke and Wake Forest NCI-designated comprehensive cancer centers. The symposium is open to multidisciplinary clinical providers and researchers to enhance our educational mission and increase engagement with learners across the health sciences.

FIG. 1.

Time line for the UNC AYA Cancer Program summarizing team member and programmatic activity growth. Addition of new team members indicated by dark gray boxes. AGNP, Adult Gerontology Nurse Practitioner; AYA, adolescent and young adult; BA, Bachelor of Arts; LCSW, Licensed Clinical Social Worker; MD, Doctor of Medicine; NA-SB, Needs Assessment and Service Bridge; NC, North Carolina; NP, nurse practitioner; UNC, University of North Carolina; yo, years old.

The next phase of team building led to hiring a full-time clinical AYA Social Worker to expand the provision of clinical psychosocial support. This enabled our Program Director to fully focus on program development, facilitating continued growth. Additionally, with more bandwidth, we expanded the population served to include patients up to 39 years old.

Continued needs assessment highlighted gaps in service capacity and subsequent program growth targeted those areas. We hired an AYA Nurse Practitioner who expanded our AYA medical consultation services (e.g., sexual health, symptom management), bolstered relationships with adult oncology, and formalized our efforts to promote clinical trial access. Although the AYA Nurse Practitioner's position is housed in Pediatric Oncology, they serve primarily young adult patients in both inpatient and outpatient settings. We next partnered with Obstetrics and Gynecology to add a Fertility Preservation Social Worker to the team, enhancing our fertility counseling services, a key need. A Young Adult Palliative Care Physician was then added in part-time manner to improve symptom management and end-of-life care.

Next, we added an AYA Clinical Research Associate to support research efforts. He has coordinated several AYA studies, developed an institutional patient registry, and enhanced outreach through the AYA website (https://uncaya.org) and newsletter. Most recently, to formally bolster the relationships across pediatric and adult oncology, a Medical Oncology Liaison who cares for AYAs with sarcoma has joined the team to advocate for AYA interests throughout the Division of Oncology. The Liaison ensures that the AYA Program's perspectives and priorities are considered in broader Medical Oncology meetings or initiatives and disseminates updates and information from Medical Oncology to the AYA team. For example, the Liaison might use monthly medical oncology staff meetings to broach AYA-specific issues or educate providers on the functions and activities of the AYA Program. Finally, we are in the process of adding a Deputy Director of AYA Research position to support a more unified AYA cancer research infrastructure and to increase the program's portfolio of external funding support.

The composition of our team progressed based on our own institutional and program needs. There are many ways to build an AYA team that may include different disciplines or may include members with similar backgrounds but who fill different roles. For example, in our team, AYA navigation services are divided between our AYA Social Worker and AYA Nurse Practitioner, both of whom also perform other clinical roles. However, many growing programs include an AYA Navigator, who may have a background in nursing, social work, child life, or other disciplines. In the end, the team must reflect the needs, resources, and goals for each institution.

Adapt model of care as team grows

Initially, our consult service was less formalized and included a visit from just one team member: the LCSW-trained AYA Program Director (L.L.). As our AYA team has grown, our consultation-based model has expanded and solidified. Our team now receives formal inpatient consults and outpatient referrals. If a patient is inpatient, the AYA Social Worker and AYA Nurse Practitioner conduct a joint visit at diagnosis. The AYA Research Associate often joins these visits to recruit patients for open studies or build rapport to support future study recruitment. The patient is then discussed by the AYA team and stratified based on their level of need or risk. In this discussion, the team considers an AYAs disease and treatment severity, social determinants of health, caregiver status, and mental health history to determine the intensity and frequency of follow-up care needed. If an AYA is outpatient, the AYA Nurse Practitioner meets with them at diagnosis through a scheduled video visit (billed service). This visit is also followed by a risk stratification discussion with the larger team to determine next steps for follow-up. The AYA Fertility Preservation Social Worker is also pulled into the consult team as needed. Once a plan for follow-up is determined, the AYA team meets with AYAs through impromptu (i.e., unscheduled) encounters in both inpatient and outpatient settings.

The AYA Medical Director, LCSW-trained AYA Program Director, and AYA Nurse Practitioner also see AYAs in survivorship through a weekly transition and survivorship clinic held in an offsite location. AYA survivors are seen through a joint visit immediately following their last treatment. They are given a survivorship care plan and connected to various other resources. Through a subsequent risk stratification discussion, the team determines if an AYA needs to be seen more frequently (e.g., every 3 months) versus less frequently (e.g., annually). Regardless, patients are encouraged to continue seeing their primary care physician.

Get creative with funding sources

Building an AYA program often requires creativity and flexibility in identifying and leveraging a variety of funding sources (e.g., hospital system, cancer center, grants, philanthropy). Funding sources for our AYA team are summarized in Table 3. Our program has benefited from the support of the Be Loud! Sophie Foundation from the outset and utilized grant funding from Teen Cancer America to facilitate growth. However, sustainability has demanded institutional culture change and demonstration of the value added to AYA cancer care. One successful approach in our program has been to pilot new positions using funds from philanthropic sources. Once the benefit of the role is demonstrated, institutional leadership may be more inclined to provide ongoing support for these now-proven positions. Additionally, acquiring philanthropic or grant funding encourages the institution to match these funds, enhancing the sustainability of an AYA program. As our program has grown, so has the buy-in from our leadership. Despite leveraging creative funding streams to open several positions, the vast majority of our program is now funded by the health system or school of medicine. It is important to note that, despite institutional and community buy-in, this model of translating philanthropic funding into institutional support for new roles has required significant time and effort on the part of our Program Director. These efforts, including communicating with institutional leaders and acquiring funds, would not have been possible if our Program Director was not able to delegate their clinical care responsibilities and dedicate their time toward program growth.

Table 3.

University of North Carolina Adolescent and Young Adult Team Member Home Departments and Funding Sources

| Position | Home department | Initial funding | Subsequent funding | Bills for services? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AYA Program Director | Psychiatry | Be Loud! Sophie Foundation | No | |

| AYA Medical Director | Pediatric Oncology | Teen Cancer America (25% salary; year 1–3) Pediatric Oncology Research grants |

Pediatric Oncology Research grants |

Yes |

| AYA Social Worker | Psychiatry | Be Loud! Sophie Foundation (year 1) Comprehensive Cancer Support Program philanthropic funds (year 1) Research grants (year 1) |

North Carolina Basnight Cancer Hospital | No |

| AYA Nurse Practitioner | Pediatric Oncology | Pediatric Oncology Medical Oncology |

Yes | |

| Fertility Preservation Social Worker | Obstetrics and Gynecology | Obstetrics and Gynecology Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center |

No | |

| Young Adult Palliative Care Physician | Pediatrics | Be Loud! Sophie Foundation (year 1) | Billable services Be Loud! Sophie Foundation (small research stipend) |

Yes |

| AYA Research Associate | Office of Clinical and Translational Research | Research grants (year 1–2) | Be Loud! Sophie Foundation | No |

| AYA Medical Oncology Liaison | Medical Oncology | Medical Oncology (in-kind effort) | Yes | |

Evaluating and Adapting

Although some metrics have been suggested,38 there is a lack of consensus on how to best evaluate an AYA program's impact.24 Like many programs, the UNC AYA Cancer Program is still grappling with how to measure and demonstrate our success through metrics such as AYA team consults and referrals, documentation of advance care planning or fertility preservation conversations, clinical trial enrollment, and numbers of patients served. To define such metrics, we are working with researchers at UNC Lineberger with expertise in health outcomes research. We are also in the process of implementing a holistic AYA needs assessment;39 this will allow us to track our success in addressing AYAs' unmet needs as they arise. However, as we explore more formalized metrics, we continuously engage in a more informal process of monitoring our impact and adapting accordingly. For example, initially, our AYA Social Worker invested time in creating peer support and activity groups. However, in tracking participation for these events, we noted low AYA engagement. Meanwhile, we saw an increasing need for complex care navigation as our public cancer hospital drew under-resourced AYAs. These factors led us to shift our AYA Social Worker's effort toward more 1:1 psychosocial support and care coordination for AYAs experiencing barriers to optimal care and increase referrals to existing external AYA peer support and activity groups. As another example, the structure and reach of the UNC AYA Survivorship Clinic has adapted to better meet the needs of this population. Initially provided within the cancer hospital and targeting AYAs more than 1 year off-therapy, we began offering visits immediately following the end of treatment, a time consistently cited as stressful and disorienting for AYAs. We also opted to move the survivorship clinic to an offsite community setting in response to reported patient distress with return to the cancer center. Such advances would not have occurred without understanding the evolving needs and preferences of the population served.

Conclusions

The development of the UNC AYA Cancer Program since 2015 has generated many lessons learned that we hope may be informative to other cancer centers seeking to build specialized services for AYAs (Table 4). In developing an AYA program, our experience has highlighted the value of starting small and building a strong foundation, followed by staged expansion of staffing and activities based on specific institutional and patient population areas of need. This phased approach to implementation enables iterative problem-solving alongside growth. The voices of patients and clinicians should be considered at all phases—a lesson underscored by Sophie's vision and enduring influence. Understanding the institution's culture, resources, and priorities is pivotal to positioning an AYA program appropriately within that context. From there, program leadership can chart a course for growth, meeting areas of need while leveraging institutional strengths to better care for AYAs.

Alignment between program and institutional priorities promotes buy-in and engagement from the broader health care system. A collaborative team-based approach is key given the range of AYAs' needs as well as the range of settings in which AYAs receive care. We advise creativity in funding strategies, prioritizing gaps in care, and looking outside traditional budgetary support to create needed positions and later solidify those roles when their benefit to the health system is recognized. We also advise flexibility, adaptability, and a spirit of continuous improvement to enable AYA programs to best meet the needs of this vulnerable and often overlooked patient population. Finally, we note that AYA program development concurrently requires and begets culture change within an institution; engaging a diverse range of individuals and providing continuous opportunities for provider education can help build a culture that is cognizant of the unique needs of the AYA population and the added value of tailored care to meet these needs.

Authors' Contributions

All authors (E.R.H., L.L., J.S., C.S., M.M., D.K., J.C., D.K.M., N.S., L.S., D.R., S.G., A.B.S.) were involved in article conceptualization, drafting, and editing. All authors read and approved the final article.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

The authors have no funding to disclose.

References

- 1. SEER*Explorer. All Cancer Sites Combined People Alive with Cancer (U.S. Prevalence) on January 1, 2019. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/aya.htmlhttps://seer.cancer.gov/statistics-network/explorer/application.html?site=1&data_type=5&graph_type=11&compareBy=sex&chk_sex_1=1&chk_sex_3=3&chk_sex_2=2&series=9&age_range=62&advopt_precision=1&hdn_view=1&advopt_display=2#tableWrap [Last accessed: December 8, 2022].

- 2. Keegan TH, Lichtensztajn DY, Kato I, et al. Unmet adolescent and young adult cancer survivors information and service needs: A population-based cancer registry study. J Cancer Surviv 2012;6(3):239–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dyson GJ, Thompson K, Palmer S, et al. The relationship between unmet needs and distress amongst young people with cancer. Support Care Cancer 2012;20(1):75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sawyer SM, McNeil R, McCarthy M, et al. Unmet need for healthcare services in adolescents and young adults with cancer and their parent carers. Support Care Cancer 2017;25(7):2229–2239; doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3630-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zebrack BJ, Corbett V, Embry L, et al. Psychological distress and unsatisfied need for psychosocial support in adolescent and young adult cancer patients during the first year following diagnosis. Psychooncology 2014;23(11):1267–1275; doi: 10.1002/pon.3533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zebrack BJ, Block R, Hayes-Lattin B, et al. Psychosocial service use and unmet need among recently diagnosed adolescent and young adult cancer patients. Cancer 2013;119(1):201–214; doi: 10.1002/cncr.27713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society Cancer Prevention and Early Detection Facts and Figures, Tables & Figures 2020. American Cancer Society: Atlanta, GA; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Park EM, Rosenstein DL. Depression in adolescents and young adults with cancer. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2015;17(2):171–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Eric T, Natasha B, Julie T, et al. Health status of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer 2012;118(19):4884–4891; doi: 10.1002/cncr.27445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Keegan TH, Ries LA, Barr RD, et al. Comparison of cancer survival trends in the United States of adolescents and young adults with those in children and older adults. Cancer 2016;122(7):1009–1016; doi: 10.1002/cncr.29869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bleyer A, Choi M, Fuller CD, et al. Relative lack of conditional survival improvement in young adults with cancer. Semin Oncol 2009;36(5):460–467; doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pollock BH. Where adolescents and young adults with cancer receive their care: Does it matter? J Clin Oncol 2007;25(29):4522–4523; doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.1715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nass SJ, Beaupin LK, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. Identifying and addressing the needs of adolescents and young adults with cancer: Summary of an Institute of Medicine workshop. Oncologist 2015;20(2):186–195; doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Morgan S, Davies S, Palmer S, et al. Sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll: Caring for adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010;28(32):4825–4830; doi: 10.1200/jco.2009.22.5474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Albritton K, Bleyer WA. The management of cancer in the older adolescent. Eur J Cancer 2003;39(18):2584–2599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wilkinson J. Young people with cancer–how should their care be organized? Eur J Cancer Care 2003;12(1):65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Albritton K, Caligiuri M, Anderson B, et al. Closing the Gap: Research and Care Imperatives for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Health, National Cancer Institute, and the LiveStrong Young Adult Alliance: Bethesda, MD; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ramphal R, Meyer R, Schacter B, et al. Active therapy and models of care for adolescents and young adults with cancer. Cancer 2011;117(Suppl 10):2316–2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Johnson RH. AYA in the USA. International perspectives on AYAO, Part 5. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2013;2(4):167–174; doi: 10.1089/jayao.2012.0027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reed D, Block RG, Johnson R. Creating an adolescent and young adult cancer program: Lessons learned from pediatric and adult oncology practice bases. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 2014;12(10):1409–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shaw PH, Boyiadzis M, Tawbi H, et al. Improved clinical trial enrollment in adolescent and young adult (AYA) oncology patients after the establishment of an AYA oncology program uniting pediatric and medical oncology divisions. Cancer 2012;118(14):3614–3617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mitchell L, Tam S, Lewin J, et al. Measuring the impact of an adolescent and young adult program on addressing patient care needs. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2018;7(5):612–617; doi: 10.1089/jayao.2018.0015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Crosswell HE, Quddus F, Khan SS. Adolescent and young adult leukemia and lymphoma care delivery in the community: Metrics and outcomes of a community-based, immersive AYA program. Blood 2018;132(Suppl 1):4733–4733; doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-99-111526 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haines E, Asad S, Lux L, et al. Guidance to support the implementation of specialized adolescent and young adult cancer care: A qualitative analysis of cancer programs. JCO Oncol Pract 2022;18(9):e1513–e1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sullenger RD, Deal AM, Grilley Olson JE, et al. Health insurance payer type and ethnicity are associated with cancer clinical trial enrollment among adolescents and young adults. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2022;11(1):104–110; doi: 10.1089/jayao.2021.0008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Osborn M, Johnson R, Thompson K, et al. Models of care for adolescent and young adult cancer programs. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2019;66(12):e27991; doi: 10.1002/pbc.27991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reed DR, Oshrine B, Pratt C, et al. Sink or collaborate: How the immersive model has helped address typical adolescent and young adult barriers at a single institution and kept the adolescent and young adult program afloat. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2017;6(4):503–511; doi: 10.1089/jayao.2017.0051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Miech EJ, Rattray NA, Flanagan ME, et al. Inside help: An integrative review of champions in healthcare-related implementation. SAGE Open Med 2018;6:2050312118773261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nightingale CL, Quinn GP, Shenkman EA, et al. Health-related quality of life of young adult survivors of childhood cancer: A review of qualitative studies. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2011;1(3):124–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tsangaris E, Johnson J, Taylor R, et al. Identifying the supportive care needs of adolescent and young adult survivors of cancer: A qualitative analysis and systematic literature review. Support Care Cancer 2014;22(4):947–959; doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2053-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mercadante S, Vitrano V, Catania V. Sexual issues in early and late stage cancer: A review. Support Care Cancer 2010;18(6):659–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fan S-Y, Eiser C. Body image of children and adolescents with cancer: A systematic review. Body Image 2009;6(4):247–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Parsons HM, Harlan LC, Lynch CF, et al. Impact of cancer on work and education among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 2012;30(19):2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smith A, Parsons H, Kent E, et al. Unmet support service needs and health-related quality of life among adolescents and young adults with cancer: The AYA HOPE study. Front Oncol 2013;3:75; doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zebrack B. Information and service needs for young adult cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2008;16(12):1353–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Van Bewer V. Transdisciplinarity in health care: A concept analysis. Nurse Forum 2017;52(4):339–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ferrari A, Thomas D, Franklin AR, et al. Starting an adolescent and young adult program: Some success stories and some obstacles to overcome. J Clin Oncol 2010;28(32):4850–4857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Greenberg M, Klassen A, Gafni A, et al. Outcomes and metrics: Measuring the impact of a comprehensive adolescent and young adult cancer program. Cancer 2011;117(Suppl 10):2342–2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Haines ER, Lux L, Smitherman AB, et al. An actionable needs assessment for adolescents and young adults with cancer: The AYA Needs Assessment & Service Bridge (NA-SB). Support Care Cancer 2021;29(8):4693–4704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Coccia PF, Pappo AS, Beaupin L, et al. Adolescent and young adult oncology, version 2.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 2018;16(1):66–97; doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]