Abstract

Supramolecular chemistry provides an effective strategy for the molecular recognition of diverse molecules. Significant efforts to design synthetic hosts have enabled the successful binding of many types of guests; however, less is known about how host–guest environments influence binding. Herein, we present a comprehensive study in which we measure the host–guest binding of a bis(arylethynyl phenylurea) host with a chloride guest in eight solvents spanning ET(30) values ranging from nonpolar (40.7 kcal mol−1) to polar (47.4 kcal mol−1). Polar solvents show significantly weaker binding in comparison to nonpolar solvents, and the bulk solvent polarity parameter, ET(30), shows a linear free-energy relationship with respect to the free energy of binding in the host–guest complex. These studies provide a better understanding of how host–guest binding in flexible receptors is governed by their environments and highlight the importance of host reorganization contributions in the free energy of binding. In addition, these studies highlight that preorganization may not be as important as previously thought for weak binding in which enthalpic contributions are smaller versus in polar solvents where solvent effects are magnified.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Supramolecular chemistry offers an effective platform for the molecular recognition of diverse molecules, including anions, across disparate areas of chemistry.1,2 As examples of important anionic targets for molecule recognition, nitrate is a problematic environmental contaminant in agriculture,3 chloride plays crucial roles in biological systems,4 and hydrosulfide is an essential biological signaling molecule.5 The landscape of anionic targets for molecular recognition includes monoatomic anions as well as more complex multiatomic inorganic and organic anions with diverse functionalities that aid strategies for their recognition in synthetic host systems. A variety of intermolecular forces, including electrostatic interactions,6 halogen bonding,7 anion-π interactions,8–10 and hydrogen bonding, is commonly used in synthetic platforms to develop efficacious and selective hosts for specific anionic motifs.11–13 Many of the receptor classes that utilize hydrogen bonding interactions maintain high anion binding affinities in nonpolar solvents, in which electrostatic interactions are key to maximizing host–guest interactions. As an example of such systems, our group has studied an arylethynyl urea platform that binds anions through N–H and C–H hydrogen bonds and has demonstrated the importance of both host design and electronic interactions in influencing anion binding.12,14–16 In this system, linear free-energy relationship (LFER) investigations revealed that polarization of C–H hydrogen bonds responds to substituent effects similar to their N–H and O–H counterparts15 and that these interactions result in differential selectivity for hydrosulfide over chloride, bromide, and hydroselenide.16

A key question in anion binding and recognition is how host–guest interactions are influenced by the local environment. This question becomes particularly relevant as solvent polarity increases because host–guest complexation is often hindered by the high free energy of solvation, or preferential solvation, of the host and guest.17 Despite these challenges, effective hosts for anions that function in very polar environments have been developed, and they typically rely on a hydrophobic pocket to discourage solvation at the binding site. The importance of understanding these interactions becomes even more relevant when expanding anion binding studies to biologically relevant anions in water (H2O).18 A notable example of a hydrogen bonding host in aqueous solution comes from Sindelar and co-workers, who used an H2O-soluble bambusuril macrocycle to bind chloride in 20 mM pH 7.1 PBS buffer solution with an association constant for chloride, Ka(Cl−), of ∼103 M−1.19 Much like how proteins can form ion channels by complementary hydrogen bonding networks in hydrophobic pockets, the bambusuril macrocycle contains a nonpolar hydrophobic center that excludes H2O molecules. Conversely, in an alternative approach, Bowman-James and co-workers have synthesized mixed amine/amide covalent organic cages capable of encapsulating pentameric structures of water or water and fluoride inside the cage.20 Remarkably, the shape of the cage allows for the partial solvation of the fluoride ion by water in order to occupy a tetrahedral array of water molecules inside of the cage. Similar to this approach, Gibb and co-workers have reported hosts that bind guests inclusive of (at least part of) their H2O solvation shell, thus reducing desolvation penalties. As an example of this approach, hydrophobic binding pockets large enough to include H2O-solvated anions enabled the binding of a number of anions, and insightful computational work supported that partial solvation of the anion is the key to binding.21

Detailed studies investigating the effect of host–guest solvation environments on anion binding are scarce. A recent comprehensive study by Flood and co-workers using a triazolophane macrocycle in polar and nonpolar solvents demonstrated that the free energy of binding was inversely proportional to the solvent polarity as measured by dielectric constants of pure solvents.22 In a separate bambusuril macrocycle modified with oligo(ethylene glycol) substituents, Sindelar and co-workers performed a solvent study that displayed a linear correlation between the Swain acidity parameter and log Ka, attributed to the anion-solvating tendencies of the solvents measured.23 This study also noted rough linear trends when comparing other solvent parameters such as the Guttmann–Beckett acceptor number and the ET(30) solvent polarity scale to log Ka; however, significant outliers were observed upon fitting the data and thus generalizations were not made. In more flexible aryl triazole hosts, Craig and co-workers investigated chloride binding in different solvents and found that increasing the hydrogen bonding acceptor number of the solvent significantly reduced the chloride binding affinity.24 Relatively weak anion binding was observed across all solvents investigated in this study, which suggested that anion solvation—dominated by electrostatic interactions between the solvents and guests—was competitive with direct host–guest interactions, limiting the ability to investigate solvent effects directly.

Preorganization of a host is an important factor when tuning the binding strength and specificity of the host, as has been demonstrated in numerous examples in the literature in cation host–guest complexation.25 To better understand the role of solvation and host reorganization more broadly in flexible rather than shape-persistent hosts, a more comprehensive investigation of anion binding spanning multiple orders of magnitude in Ka in both polar and nonpolar solvent regimes is needed. Motivated by this need, we present here a comprehensive study interrogating the host–guest interactions with a flexible host across eight solvents ranging from H2O-saturated CHCl3 (least polar) to 1:10 H2O/DMSO (most polar). Importantly, these investigations revealed a linear free-energy relationship between bulk solvent polarity and anion binding, which we anticipate will help inform the development of new hosts that function in more polar solvents and also will help guide fundamental studies of how host–guest interactions are influenced by solvation environments.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

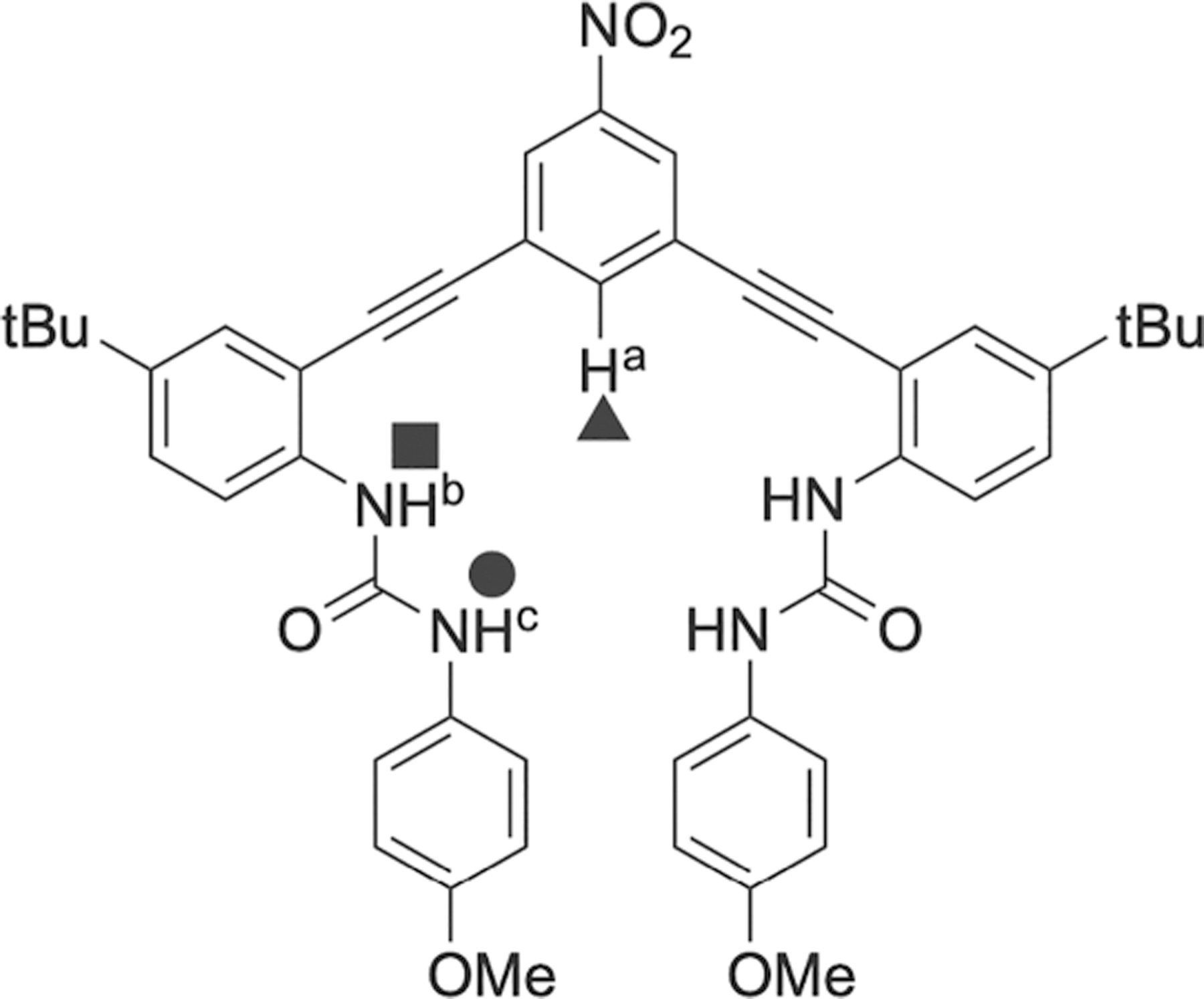

To investigate how solvation environment influences the host–guest interactions across solvents of varying polarity, 1H NMR titration studies were performed to measure the 1:1 binding affinity of a nitro-functionalized bis(arylethynyl) bis(urea) host 1 with a chloride guest (Chart 1). We performed these measurements in mixed solvent systems and used the ET(30) solvent polarity scale rather than dielectric constant as a measure of bulk solvent polarity.26,27 In addition, the ET(30) bulk solvent polarity scale provides information on the microscopic solute–solvent interactions. Solvents spanning ET(30) values ranging from nonpolar (40.7 kcal mol−1) to polar (47.4 kcal mol−1) were tested.28–30

Chart 1. Bis(arylethynyl) Bis(urea) Host 1 Used in This Study and Labeling Scheme Used Throughouta.

aTriangle = aryl C–H (Ha), square = proximal urea N–H (Hb), and circle = distal urea N–H (Hc).

Bis(arylethynyl phenylurea) Flexible Host.

To gain an understanding of how host–guest interactions are influenced by their solvation environment, we used the previously synthesized flexible NO2-functionalized bis(arylethynyl phenylurea) host 1.15 This class of hosts has been studied by our group, and their flexibility is derived from the free rotation about the ethynyl functionality. Through a combination of computation,31 solid-state, and solution-phase data, the general feature of this receptor class has three main conformations: W, S, and U.32,33 Solid-state structural data of host 1 in the absence of guest displays a W conformation;15 however, when the host of the same class of receptor (with an H functionality in place of NO2) is crystallized, the solid-state structure reveals a U structure.34 Additionally, we observe the U conformation in the presence of guest when performing titrations in the solution phase based on the data providing that the Ha (aryl C–H), Hb (proximal urea N–H), and Hc (distal urea N–H) all shift downfield when titrating with a guest (vide infra).

This host is soluble in a wide range of solvents from polar 1:10 H2O/DMSO to nonpolar H2O-saturated CHCl3, making it ideal for this study. For clarity, all solvent mixtures in this study are referred to as volume by volume ratios. To measure the impact of different solvation environments on the host directly in the absence of guest, we acquired the 1H NMR spectra of 1 in various rigorously dried solvents. When 1 was dissolved in a mixture of 1:100 DMSO-d6/CD2Cl2, the Ha, Hb, and Hc protons were observed at 8.06, 7.77, and 8.23 ppm, respectively (Figure 1). As the ratio of DMSO-d6 to CD2Cl2 increased, the Ha, Hb, and Hc resonances consistently shifted downfield. When the spectrum was acquired in neat DMSO-d6, the Ha, Hb, and Hc resonances were observed at 8.19, 8.41, and 9.25 ppm, respectively. In this case, the solvent polarity and concentration of hydrogen bond acceptors in the solution (i.e., DMSO) resulted in a significant downfield shift of the Ha, Hb, and Hc protons, which is consistent with solvent hydrogen bonding with the host.35 As D2O is introduced into the DMSO-d6 solution, the Ha, Hb, and Hc resonances shift slightly upfield. For example, in 1:10 D2O/DMSO-d6, the Ha, Hb, and Hc resonances are observed at 8.32, 8.18, and 9.23 ppm, respectively. This observed upfield shift is consistent with DMSO being a more favorable hydrogen bond acceptor as compared with H2O using the Gutmann donor number (DNDMSO = 29.8 and DNH2O = 18.0).36 As a whole, these initial experiments demonstrate the impact that solvation environments and polarity have on the solution interactions of host 1.

Figure 1.

1H NMR spectra of 1 in different solvent mixtures. All spectra are referenced to DMSO. The NH resonances are significantly diminished in the 1:10 D2O/DMSO solutions due to H/D exchange.

Establishing Bulk Solvent Polarity in Mixed Solvent Systems.

The dielectric constant (ε) of a pure solvent is the most commonly used measurement of macroscopic solvent polarity. Specifically, ε describes the electrostatic properties of a solvent and is a quantitative description of the energetics of two charged particles in a medium. A higher ε value indicates a more polar solvent.37 However, the ε values are generally measured for pure solvents and do not provide information on the microscopic solvation or on solute–solvent interactions, both of which are integral for investigating how host–guest interactions are influenced by local environments. An alternative to using ε for solvent polarity measurements is to use the ET(30) scale developed by Reichardt.26,27 This scale uses a solvatochromatic pyridinium N-phenolate dye (Reichardt’s dye), which has a large permanent dipole moment, a polarizable 42-electron π system, and a phenolate oxygen. Reichardt’s dye exists as a zwitterion in its ground state and a diradical in its excited state. The ET(30) value is proportional to the light energy required to reach its excited state; for example, in polar solvents, the ground-state energy of the zwitterion is stabilized, requiring higher energy light to reach its neutral diradical excited state (which maintains roughly constant in relative energy over varying solvent polarities). Furthermore, ET(30) measurements depend on electronic transitions of molecules and happen on the timescale of femtoseconds, providing a snapshot of the ground-state energy including the solvation shell of the molecule, whereas ε requires a measurement of light between two electrodes and occurs on the timescale of nanoseconds, which is slower than typical hydrogen bond lifetimes.38 The stabilizing effect that solvents of varying polarity have on Reichardt’s dye allow ET(30) to provide a method for the quantitative measurement of how solvent–solute interactions influence solvent polarity, i.e., the solvation capability of a solvent, which includes the following factors: dipole–dipole interactions, hydrogen bonding, electron pair donor/acceptor interactions, and dispersion interactions. These considerations led us to choose the ET(30) solvent polarity scale for solvent polarity measurements of DMSO and DMSO-mixed solvent systems in this study. The normalized UV/Vis spectra of Reichardt’s dye and the corresponding ET(30) values for different solvent mixtures are provided in the Supporting Information (Table S1 and Figure S1).

NMR Titrations.

1H NMR spectroscopy titrations were performed to determine how the host–guest environment influences the binding of Cl− to host 1 (Scheme 1). Consistent with previous studies on hydrogen bonding hosts, titrations were performed in various solvents, keeping the host concentration constant during an experiment (between 1.08 and 1.62 mM) and titrating in a solution containing both tetrabutylammonium chloride (TBACl) and the host. Ka values were determined by fitting the changes in the chemical shifts () of hydrogen bonding protons Ha, Hb, and Hc to a 1:1 host–guest model using Thordarson’s method (see Supporting Information).39,40

Scheme 1.

Representation of Host–Guest Equilibrium between 1 and Cl−

Two representative titrations in a polar and nonpolar medium are shown in Figure 2. In all of the titrations, the addition of TBACl results in a downfield shift of the Ha, Hb, and Hc resonances, which indicates hydrogen bonding of Cl− to the host. In the titration of 1 in the most polar solvent system (1:10 D2O/DMSO-d6), the resonance corresponding to Hc is initially observed at 9.25 ppm. After the addition of 71.0 equiv of TBACl and near the saturation point of the host, a of 0.73 ppm downfield is observed to 9.98 ppm.

Figure 2.

(a) 1H NMR titration spectra of 1 in 1:10 D O/DMSO. The NH resonances are significantly diminished in the 1:10 D2O/DMSO solutions due to H/D exchange. (b) 1H NMR titration spectra of 1 in 1:100 DMSO/CD2Cl2.

In the titration near the least polar solvent system (1:100 DMSO-d6/CD2Cl2), the resonance corresponding to Hc is initially observed at 8.23 ppm, and after the addition of 4.4 equiv of TBACl and near the saturation point, a of 2.22 ppm downfield is observed to 10.43 ppm. To rule out the possibility that ion pairing had a large effect on the binding in the nonpolar 1:100 DMSO-d6/CD2Cl2 titration, we noted that the α-methylene resonance of free TBA+ in DCM is observed at 2.95 ± 0.05 ppm.41 For the titration in 1:100 DMSO-d6/CD2Cl2, the α-methylene TBA+ resonance deviates by only 0.03 ppm from this upper limit range and shows minimal changes up to the saturation point, suggesting that ion pairing has little influence on the host–guest interactions of this system. The shift in Hc of 0.73 and 2.22 ppm for titrations in 10:1 DMSO-d6/D2O and 1:100 DMSO-d6/CH2Cl2, respectively, demonstrates that the polarizing interaction of this hydrogen bond is increased in nonpolar solvents, or environments with fewer competing interactions between solvent and guest molecules.

Stability of Host–Guest Complexation.

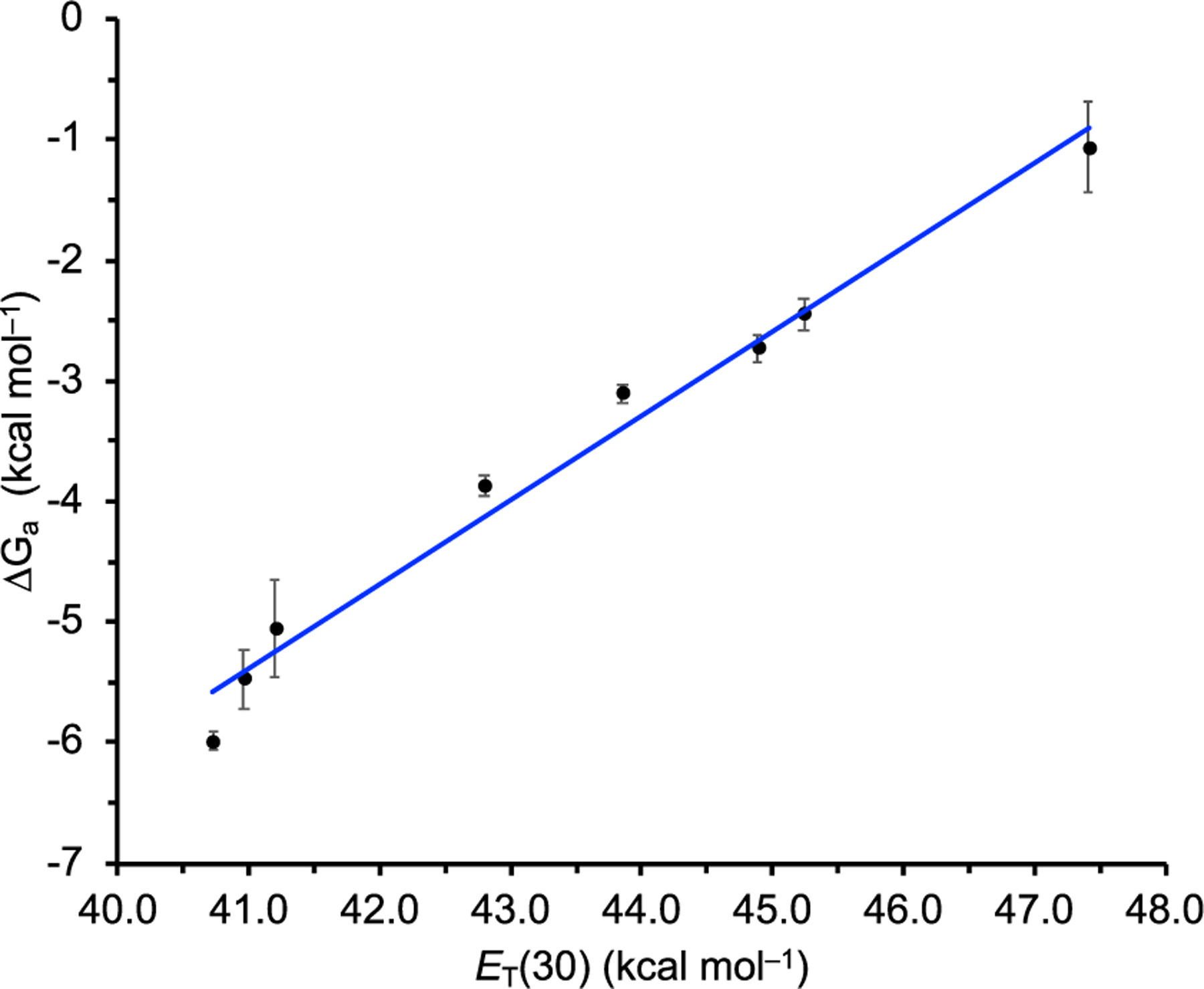

The effect of solvation environment on host–guest complexation was further interrogated using titrations spanning eight solvent systems ranging from the least polar H2O-saturated CHCl3 to most polar 10:1 DMSO/H2O with ET(30) values ranging from 40.7 to 47.4 kcal mol−1, respectively (Table 1). The range of Ka values spans four orders of magnitude across these solvent polarities. Moreover, a consistent trend is observed in which the association constants decrease with increasing bulk solvent polarity, as expected. Furthermore, a linear trend (R2 = 0.98) is observed when (kcal mol−1) of the host–guest complex 1·Cl− is plotted against the empirical solvent polarity parameter ET(30) (kcal mol−1, Figure 3).42 The ET(30) solvent polarity scale measures the energy required to excite Reichardt’s dye to the diradical excited state, and it is influenced by microscopic solvent properties; hence, we are able to derive a LFER between host–guest binding and solvent polarity in 1·Cl−, as influenced by these microscopic solvent–solute interactions (Figure 3). The bulk solvent polarity also has a large impact on . For example, there is a significant ∼5 kcal mol−1 difference in between the most and least polar solvent mixtures, and when taken together, these results demonstrate the large energy penalty generated by microscopic solvation environments in host–guest binding. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first example of a hydrogen bonding host–guest complex displaying an LFER with respect to binding and bulk solvent polarity, although a separate example of a cyclophane–pyrene host–guest complex dependent on London dispersion forces and dipole–dipole interactions displaying an LFER between the free energy of binding and bulk solvent polarity using the ET(30) scale has been observed by Diederich and Smithrud.43 This LFER relates the ET(30) value of the solvent with the binding energy of the host–guest complex. The fact that we see a good fit to a linear line means that the change in ET(30) value is the only factor that dictates the change in binding strength (at least that we can observe with the precision of this overall study). The slope of the line is a measure of how sensitive the binding strength is to the ET(30) value: the closer the slope is to 0, the less sensitive it is to the ET(30) value. Furthermore, these data suggests that solvent effects that are responsible for the differences in the excitation energies of Reichardt’s dye (vide supra) are also connected to the trends in binding constants observed in this system, further reinforcing how ET(30) is apparently different than other solvent scales in assessing solvent effects in this system.

Table 1.

Binding Parameters for 1 with Cl− at 298 K

| solvent A | solvent B | A/B (by volume) | ET(30) (kcal mol−1) | log(Ka) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2O | DMSO | 1:10 | 47.4 | 0.77 ± 0.6 | −1.05 ± 0.4 |

| H2O | DMSO | 1:100 | 45.2 | 1.79 ± 0.2 | −2.44 ± 0.1 |

| DMSO | 44.9 | 2.00 ± 0.2 | −2.73 ± 0.1 | ||

| DMSO | CH2Cl2 | 1:2 | 43.9 | 2.28 ± 0.1 | −3.11 ± 0.1 |

| DMSO | CH2Cl2 | 1:4 | 42.8 | 2.84 ± 0.1 | −3.87 ± 0.1 |

| DMSO | CH2Cl2 | 1:20 | 41.2 | 3.71 ± 0.7 | −5.06 ± 0.4 |

| DMSO | CH2Cl2 | 1:100 | 41.0 | 4.02 ± 0.4 | −5.47 ± 0.2 |

| CHCl3a | H2O | H2O-saturated | 40.7 | 4.39 ± 0.1 | −5.99 ± 0.1 |

Previously reported by UV/Vis titration.15 Values shown are an average of three 1H NMR titrations. See the Supporting Information for representative data and fitting.

Figure 3.

The 1:1 binding affinity () of host 1 with Cl− at 298 K as a function of bulk solvent polarity ET(30).

Comparison with Shape-Persistent Hosts.

The differences in this system compared to others interrogating solvent parameters and the basis for this correlation can be described by defining , as adapted from Flood and co-workers, and is shown by eqs 1 and 222,44

| (1) |

| (2) |

In these equations, describes the binding of the host and guest in the gas phase, is the reorganization energy for the ideal geometry in binding, and is the change in solvation energy of the host, guest, and host–guest complex and described by eq 2. In the macrocyclic host studied by Flood in various solvents, the data suggests that can be ignored because the host is not flexible and always maintains the correct geometry for binding. Because is a constant measurement, is proportional to , which decreases in nonpolar solvents. This approximation worked well for the rigid macrocyclic host in pure solvents, but it did not work for solvent mixtures of DMSO and H2O. Unlike the Flood system, the bis(urea) host used in our study is flexible, and therefore, the contribution of must be considered when taking into account the contributions to is a constant for each host–guest system; therefore, we propose that changes in are proportional to changes in (), and because these factors are solvent-dependent, the LFER is observed. This analysis suggests that in a shape-persistent host, the reorganization energy can generally be ignored, but in flexible hosts, such as the one used in this study, the reorganization energy has a much greater effect on the overall binding. Furthermore, it suggests that changes in entropy associated with reorganization contribute significantly to the free energy of binding. Last, our data for a flexible host show that mixed solvent systems of ranging solvent polarities and with varying intermolecular forces still follow the LFER, while conversely, in the work presented by Flood with a shape-persistent host, a semi-empirical LFER was established, and it is possible that contributions from account for these differences between these two classes of hosts. We anticipate that the next needed step in unifying these models is ascertaining the magnitude of the entropic contributions from host reorganization when compared to the total entropy of a binding event, including guest desolvation.45

CONCLUSIONS

In this work, we have presented a comprehensive study of how solvent polarity influences host–guest interactions in a flexible host. Immediate observations after the acquisition of 1H NMR data of the host 1 in varying solvents portrayed the significance of solvation effects, as seen by significant deshielding of NH and CH hydrogen bonds in solvents with better hydrogen bond acceptors. NMR titration studies verify that the hydrogen bonding host binds Cl− anion in solvent polarities ranging from the least polar (H2O-saturated CHCl3) to most polar (1:10 H2O/DMSO), spanning a broad range of ET(30) values (40.7 to 47.4 kcal mol−1, respectively). The free energy of anion binding between the least polar and most polar solvent spans ∼5 kcal mol−1 and is attributed to preferential solvation or competition of binding with solvent molecules of the host with Cl−. Further analysis of these results established a linear free-energy relationship between bulk solvent polarity and binding affinity with Cl−. To the best of our knowledge, this represents for the first time such a relationship that has been observed in anion binding with a hydrogen bonding host. This work highlights key differences observed between flexible and rigid hydrogen bonding hosts. For flexible systems like ours, host reorganization has a significant contribution to the free energy of binding. Furthermore, these developments guide our understanding of how hosts behave in different solvent environments and aid in the development of future receptors, which we hope to use in more polar solvents while maintaining large binding affinities. One important finding in this work suggests that shape-persistent hosts may have advantages over flexible hosts in binding strengths in nonpolar environments but are more susceptible to solvation penalties in increasingly polar solvents. In addition, penalties for shape-persistent hosts can come from their ground-state destabilization: unbound shape-persistent hosts can be fixed into conformations with destabilizing interactions, which are larger in nonpolar environments and smaller in polar environments. In fact, such a conclusion may signify a manifestation of the lock-and-key principle and enthalpy–entropy compensation: enforcing stronger, more rigid enthalpic binding has entropic consequences, whereas flexibility may diminish solvation penalties despite weaker binding due to a lack of preorganization. Since host rigidity may be less important in polar solvents—when solvation effects and enthalpy of binding are of similar magnitude—flexible supramolecular anion-binding hosts may provide added utility in highly polar solvents.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials and Methods.

All manipulations were performed under an inert atmosphere using an Innovative Atmospheres N2-filled glovebox unless otherwise noted. CD2Cl2 and DMSO-d6 were distilled from CaH2, then degassed with N2, and stored in an inert atmosphere glovebox over 4 Å molecular sieves. Tetrabutylammonium chloride was purchased from TCI Chemical, and NMR solvents were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories. Host 1 was synthesized from an established preparation.15 UV/Vis spectra were acquired on an Agilent Cary 60 UV/Vis spectrophotometer equipped with a Quantum Northwest TC-1 temperature controller set at 25 ± 0.05 °C. NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker Avance-III-HD 600 spectrometer (1H: 600 MHz), a Bruker Avance-III-HD 500 spectrometer (1H: 500 MHz), or a Varian 500 MHz spectrometer (1H: 500 MHz). Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million () and are referenced to residual solvent resonances (CD2Cl2 1H 5.32 ppm, DMSO-d6 1H 2.50 ppm).

NMR Titrations.

General Procedure for NMR Titrations.

A solution of host was prepared (1.7 mL), and was added to a septum-sealed NMR tube. The remaining host solution (0.9–1.0 mL) was used to prepare a host–guest stock solution. Aliquots of the host–guest solution were added to the NMR tube using Hamilton gas-tight syringes, and 1H NMR spectra were recorded at 25 °C after each addition of guest. The values of the various NH and aromatic CH protons were used to follow the progress of the titration, and association constants were determined using the Thordarson method.39

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Murdock Charitable Trust (201811528 to M.D.P./D.W.J.), the National Institutes of Health (R01-GM087398 to D.W.J./M.M.H.), and a University of Oregon VPRI Innovation Fund Grant for support in this research. This work was also supported by the Bradshaw and Holzapfel Research Professorship in Transformational Science and Mathematics to D.W.J.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.joc.0c01616.

Experimental details, UV/Vis spectra, and representative titrations (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Tobias J. Sherbow, Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry, Materials Science Institute, Knight Campus for Accelerating Scientific Impact, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon 97403-1253, United States

Hazel A. Fargher, Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry, Materials Science Institute, Knight Campus for Accelerating Scientific Impact, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon 97403-1253, United States

Michael M. Haley, Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry, Materials Science Institute, Knight Campus for Accelerating Scientific Impact, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon 97403-1253, United States.

Michael D. Pluth, Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry, Materials Science Institute, Knight Campus for Accelerating Scientific Impact, Institute of Molecular Biology, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon 97403-1253, United States.

Darren W. Johnson, Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry, Materials Science Institute, Knight Campus for Accelerating Scientific Impact, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon 97403-1253, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Sessler JL; Gale P; Cho W-S; Stoddart JF; Rowan SJ; Aida T; Rowan AE, Anion Receptor Chemistry; The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2006; p 414. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Gale PA; Howe ENW; Wu X Anion Receptor Chemistry. Chem 2016, 1, 351–422. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Ryden JC; Ball PR; Garwood EA Nitrate leaching from grassland. Nature 1984, 311, 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Russell JM; Boron WF Role of chloride transport in regulation of intracellular pH. Nature 1976, 264, 73–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Levinn CM; Cerda MM; Pluth MD Activatable Small-Molecule Hydrogen Sulfide Donors. Antioxid. Redox Signaling 2019, 32, 96–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Pluth MD; Bergman RG; Raymond KN Acid Catalysis in Basic Solution: A Supramolecular Host Promotes Orthoformate Hydrolysis. Science 2007, 316, 85–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Gilday LC; Robinson SW; Barendt TA; Langton MJ; Mullaney BR; Beer PD Halogen Bonding in Supramolecular Chemistry. Chem. Rev 2015, 115, 7118–7195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Schottel BL; Chifotides HT; Dunbar KR Anion-π interactions. Chem. Soc. Rev 2008, 37, 68–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Giese M; Albrecht M; Rissanen K Anion–π Interactions with Fluoroarenes. Chem. Rev 2015, 115, 8867–8895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Berryman OB; Bryantsev VS; Stay DP; Johnson DW; Hay BP Structural Criteria for the Design of Anion Receptors: The Interaction of Halides with Electron-Deficient Arenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 48–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Berryman OB; Sather AC; Hay BP; Meisner JS; Johnson DW Solution Phase Measurement of Both Weak σ and C–H···X− Hydrogen Bonding Interactions in Synthetic Anion Receptors. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 10895–10897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Carroll CN; Berryman OB; Johnson CA; Zakharov LN; Haley MM; Johnson DW Protonation activates anion binding and alters binding selectivity in new inherently fluorescent 2,6-bis(2-anilinoethynyl)pyridine bisureas. Chem. Commun 2009, 2520–2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Liu Y; Zhao W; Chen C-H; Flood AH Chloride capture using a C–H hydrogen-bonding cage. Science 2019, 365, 159–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Gavette JV; Mills NS; Zakharov LN; Johnson CA II; Johnson DW; Haley MM An Anion-Modulated Three-Way Supramolecular Switch that Selectively Binds Dihydrogen Phosphate, H2PO4−. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2013, 52, 10270–10274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Tresca BW; Hansen RJ; Chau CV; Hay BP; Zakharov LN; Haley MM; Johnson DW Substituent Effects in CH Hydrogen Bond Interactions: Linear Free Energy Relationships and Influence of Anions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 14959–14967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Fargher HA; Lau N; Richardson HC; Cheong PH-Y; Haley MM; Pluth MD; Johnson DW Tuning Supramolecular Selectivity for Hydrosulfide: Linear Free Energy Relationships Reveal Preferential C–H Hydrogen Bond Interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 8243–8251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Cremer PS; Flood AH; Gibb BC; Mobley DL Collaborative routes to clarifying the murky waters of aqueous supramolecular chemistry. Nat. Chem 2018, 10, 8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Chen X; Yang T; Kataoka S; Cremer PS Specific Ion Effects on Interfacial Water Structure near Macromolecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 12272–12279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Yawer MA; Havel V; Sindelar V A Bambusuril Macrocycle that Binds Anions in Water with High Affinity and Selectivity. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2015, 54, 276–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Wang Q-Q; Day VW; Bowman-James K Chemistry and Structure of a Host–Guest Relationship: The Power of NMR and X-ray Diffraction in Tandem. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 392–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Sokkalingam P; Shraberg J; Rick SW; Gibb BC Binding Hydrated Anions with Hydrophobic Pockets. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 48–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Liu Y; Sengupta A; Raghavachari K; Flood AH Anion Binding in Solution: Beyond the Electrostatic Regime. Chem 2017, 3, 411–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Fiala T; Sleziakova K; Marsalek K; Salvadori K; Sindelar V Thermodynamics of Halide Binding to a Neutral Bambusuril in Water and Organic Solvents. J. Org. Chem 2018, 83, 1903–1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Juwarker H; Lenhardt JM; Castillo JC; Zhao E; Krishnamurthy S; Jamiolkowski RM; Kim K-H; Craig SL Anion Binding of Short, Flexible Aryl Triazole Oligomers. J. Org. Chem 2009, 74, 8924–8934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Cram DJ Preorganization—From Solvents to Spherands. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 1986, 25, 1039–1057. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Reichardt C Solvatochromism, thermochromism, piezochromism, halochromism, and chiro-solvatochromism of pyridinium N-phenoxide betaine dyes. Chem. Soc. Rev 1992, 21, 147–153. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Reichardt C Solvatochromic Dyes as Solvent Polarity Indicators. Chem. Rev 1994, 94, 2319–2358. [Google Scholar]

- (28).The polarity range of the solvents used in this study spans dielectric values of ∼4.8 for water-saturated CHCl3 and ∼56 for 1:10 water/DMSO.

- (29).Lide DR CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics; 84th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Lu Z; Manias E; Macdonald DD; Lanagan M Dielectric Relaxation in Dimethyl Sulfoxide/Water Mixtures Studied by Microwave Dielectric Relaxation Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 12207–12214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Carroll CN; Coombs BA; McClintock SP; Johnson Ii CA; Berryman OB; Johnson DW; Haley MM Anion-dependent fluorescence in bis(anilinoethynyl)pyridine derivatives: switchable ON–OFF and OFF–ON responses. Chem. Commun 2011, 47, 5539–5541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Eytel LM; Brueckner AC; Lohrman JA; Haley MM; Cheong PHY; Johnson DW Conformationally flexible arylethynyl bis-urea receptors bind disparate oxoanions with similar, high affinities. Chem. Commun 2018, 54, 13208–13211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Engle JM; Lakshminarayanan PS; Carroll CN; Zakharov LN; Haley MM; Johnson DW Molecular Self-Assembly: Solvent Guests Tune the Conformation of a Series of 2,6-Bis(2-anilinoethynyl)pyridine-Based Ureas. Cryst. Growth Des 2011, 11, 5144–5152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Tresca BW; Zakharov LN; Carroll CN; Johnson DW; Haley MM Aryl C–H···Cl− hydrogen bonding in a fluorescent anion sensor. Chem. Commun 2013, 49, 7240–7242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Arunan E; Desiraju GR; Klein RA; Sadlej J; Scheiner S; Alkorta I; Clary DC; Crabtree RH; Dannenberg JJ; Hobza P; Kjaergaard HG; Legon AC; Mennucci B; Nesbitt DJ Defining the hydrogen bond: An account (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem 2011, 83, 1619–1636. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Gutmann V Solvent effects on the reactivities of organometallic compounds. Coord. Chem. Rev 1976, 18, 225–255. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Archer DG; Wang P The Dielectric Constant of Water and Debye-Hückel Limiting Law Slopes. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1990, 19, 371–411. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Keutsch FN; Saykally RJ Water clusters: Untangling the mysteries of the liquid, one molecule at a time. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2001, 98, 10533–10540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Thordarson P Determining association constants from titration experiments in supramolecular chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev 2011, 40, 1305–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Brynn Hibbert D; Thordarson P The death of the Job plot, transparency, open science and online tools, uncertainty estimation methods and other developments in supramolecular chemistry data analysis. Chem. Commun 2016, 52, 12792–12805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Hua Y; Ramabhadran RO; Uduehi EO; Karty JA; Raghavachari K; Flood AH Aromatic and Aliphatic CH Hydrogen Bonds Fight for Chloride while Competing Alongside Ion Pairing within Triazolophanes. Chem. – Eur. J 2011, 17, 312–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Contributions to the linearity over such a wide range comes from some of values containing water.

- (43).Smithrud DB; Diederich F Strength of molecular complexation of apolar solutes in water and in organic solvents is predictable by linear free energy relationships: a general model for solvation effects on apolar binding. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1990, 112, 339–343. [Google Scholar]

- (44). We do note that eq 1 is an approximation and that there are minor contributions from other factors that influence the free energy of binding.

- (45). It is reasonable to assume that there may be other factors at play forcing us to avoid making a general assumption for all host–guest interactions in varying solvents. For example, the type of H-bond donor (C-H, N-H, and O-H) may be influenced by solvation and further influence the host–guest interactions of that system.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.