Abstract

Caulobacter crescentus is a gram-negative bacterium that produces a two-dimensional crystalline array on its surface composed of a single 98-kDa protein, RsaA. Secretion of RsaA to the cell surface relies on an uncleaved C-terminal secretion signal. In this report, we identify two genes encoding components of the RsaA secretion apparatus. These components are part of a type I secretion system involving an ABC transporter protein. These genes, lying immediately 3′ of rsaA, were found by screening a Tn5 transposon library for the loss of RsaA transport and characterizing the transposon-interrupted genes. The two proteins presumably encoded by these genes were found to have significant sequence similarity to ABC transporter and membrane fusion proteins of other type I secretion systems. The greatest sequence similarity was found to the alkaline protease (AprA) transport system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the metalloprotease (PrtB) transport system of Erwinia chrysanthemi. The prtB and aprA genes were introduced into C. crescentus, and their products were secreted by the RsaA transport system. Further, defects in the S-layer protein transport system led to the loss of this heterologous secretion. This is the first report of an S-layer protein secreted by a type I secretion apparatus. Unlike other type I secretion systems, the RsaA transport system secretes large amounts of its substrate protein (it is estimated that RsaA accounts for 10 to 12% of the total cell protein). Such levels are expected for bacterial S-layer proteins but are higher than for any other known type I secretion system.

The gram-negative bacterium Caulobacter crescentus is covered with a crystalline protein surface layer (S-layer) (40) composed of the 98-kDa protein RsaA (20). Six copies of RsaA form a ringlike subunit that interconnects with other subunits to form a two-dimensional hexagonal array (39). The gene for RsaA has been cloned (38) and sequenced (20). Protein sequencing of the mature RsaA polypeptide has shown that only the initial N-formyl methionine is cleaved, leaving a mature polypeptide of 1,025 residues (18, 20). The S-layer is anchored to the cell surface via a noncovalent interaction between the N terminus of the protein and a specific smooth lipopolysaccharide (S-LPS) in the outer membrane (44). Ca2+ is required for the proper crystallization of RsaA into the S-layer, and its removal by using EGTA disrupts the S-layer structure (32, 45). It is presumed that a key function of the C. crescentus S-layer is to act as a physical barrier to parasites and lytic enzymes. It has been demonstrated to offer protection from a Bdellovibrio-like organism (26).

Because RsaA must pass through both the inner and outer membranes to form the S-layer on the outer surface of the bacterium, it is a true secreted protein. Further, an efficient secretion system is required for RsaA transport because the quantity of protein produced is significant (we have estimated that RsaA makes up 10 to 12% of the cell protein). Deletion and hybrid protein analyses have indicated that secretion of RsaA relies on an uncleaved C-terminal secretion signal located within the last 242 C-terminal amino acids of the RsaA protein (5, 7, 8). The presence of an uncleaved C-terminal secretion signal is generally diagnostic for proteins secreted by type I systems (4, 35) rather than the general secretory pathway (GSP, type II system) of the cell (33). The GSP employs a cleaved N-terminal signal sequence, and in gram-negative bacteria, secretion involves a periplasmic intermediate, unlike what is found with RsaA. The GSP is the mechanism used to secrete most S-layer proteins (9).

The best-described type I secretion systems are those required for the secretion of Escherichia coli hemolysin (HlyA), Erwinia chrysanthemi metalloproteases (PrtB), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa alkaline protease (AprA) (4, 35). A type I secretion apparatus consists of three components. One component, the ABC transporter, is embedded in the inner membrane and contains an ATP-binding region. It recognizes the C-terminal signal sequence of the substrate protein and hydrolyzes ATP during the transport process. Another component, a membrane fusion protein (MFP), is anchored in the inner membrane and appears to span the periplasm (13). The remaining component is an outer membrane protein (OMP) that is thought to interact with the MFP to form a channel that extends from the cytoplasm through the two membranes to the outside of the cell. Thus, in contrast to type II secretion, the type I variety does not involve the transient appearance of the secreted protein in the periplasm.

In addition to the secretion signal, the C-terminal portion of RsaA also contains five repeats of a glycine- and aspartic acid-rich region which is thought to bind calcium ions (20); such Ca2+-binding motifs are found in most proteins secreted by type I systems (4). It has been suggested that these motifs are important for proper secretion signal presentation to the ABC transporter. Further, once the secreted protein has reached the external milieu, Ca2+ binding may trigger a conformational change in the polypeptide, helping to maintain the directional nature of the secretion process (14, 29). In the case of RsaA, then, the glycine- and aspartate-rich repeats may function (along with Ca2+) both in maintaining the crystalline structure of the S-layer and in the secretion of the S-layer protein itself. The foregoing presumes that, in fact, RsaA was secreted by a type I system, but proof of this hypothesis requires identification of the transport complex, since there is not a high degree of homology in the secretion signals of type I proteins (19). This report details the development of direct evidence for this hypothesis, identifying two of the three genes needed for the process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

All of the strains, libraries, and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli DH5α (Life Technologies) was used for all E. coli cloning manipulations. E. coli was grown at 37°C in Luria broth (1% tryptone, 0.5% NaCl, 0.5% yeast extract) with 1.2% agar for plates. C. crescentus strains were grown at 30°C in PYE medium (0.2% peptone, 0.1% yeast extract, 0.01% CaCl2, 0.02% MgSO4) with 1.2% agar for plates. Ampicillin was used at 100 μg/ml, streptomycin was used at 50 μg/ml, kanamycin was used at 50 μg/ml, and tetracycline was used at 0.5 μg/ml for C. crescentus and at 10 μg/ml for E. coli when appropriate.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or cosmids | Relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli DH5α | recA endA | Life Technologies |

| C. crescentus | ||

| JS1001 | S-LPS mutant of NA1000, sheds S-layer into medium | 16 |

| NA1000 | Aprsyn-1000; variant of wild-type strain CB15 that synchronizes well | ATCC 19089 |

| JS1003 | NA1000 with rsaA interrupted by KSAC Kmr cassette | 16 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBBR5 | Tcr; broad host range | This study |

| pBSKS+ | ColE1 cloning vector; lacZ Apr | Stratagene |

| pJUEK72 | aprD+aprE+aprF+aprA+aprI+ | 22 |

| pRAT1 | rsaA+rsaD+rsaE+ Apr | This study |

| pRAT4ΔH | rsaA+rsaD+rsaE+ Apr; rsaA is under control of lacZ promoter | This study |

| pRAT4ΔH:pBBR5 | rsaA+rsaD+rsaE+ Apr Tcr; pBBR5 was fused with pRAT4ΔH at the SstI site | This study |

| pRAT5:pRK415 | rsaD+rsaE+ Apr Tcr; pRK415 was fused with pRAT5 at the SstI site | This study |

| pRK415 | lacZ+ Tcr; broad host range | 24 |

| pRK415rsaAΔPK | rsaA under control of lacZ promoter in pRK415 | This study |

| pRUW500 | prtB+ Apr | 12 |

| pRUW500:pRK415 | prtB+ Tcr pRK415 was fused with pRUW500 at the PstI site | This study |

| pSUP2021 | Carries Tn5, unable to replicate in C. crescentus | 37 |

| pTZ18UB:rsaAΔP | The wild type promoter of rsaA has been replaced with a lacZ promoter | 7 |

| pTZ18R | Apr ColE1 cloning vector, a phagemid version of pUC18 | 30 |

| pTZ18RaprA | aprA+ apr; the EcoRI-BglII fragment from pJUEK72 containing aprA was inserted into the EcoRI-BamHI sites of pTZ18R | This study |

| pUC8 | ColE1 cloning vector; lacZ Apr | 42 |

| pUC9rsaAΔNΔC | rsaA missing the extreme N terminus and C terminus | 5, 8 |

| pUC8neoR | HindIII-BamHI fragment from Tn5 containing neomycin resistance gene inserted into the corresponding sites in pUC8 | This study |

| pTZ18RaprA:pRK415 | aprA+ Tcr; pRK415 was fused with pTZ18R at the BamHI site | This study |

| NA1000 cosmid library | 1,000 cosmids containing 20–25 kb of NA1000 DNA | 1 |

Recombinant DNA manipulations.

Standard methods of DNA manipulation and isolation were used (36). Electroporation of C. crescentus was performed as previously described (21). Southern blot hybridizations were done in accordance with the membrane manufacturer’s manual (Amersham Hybond-N). Radiolabelled probes were made by nick translation using standard procedures (36).

A PCR product containing rsaD and rsaE was generated by using primers 5′-CGGAATCGCGCTACGCGCTGG-3′ and 5′-GGGAGCTCGAAGGGTCCTGA-3′. The product was generated by using Taq polymerase (Bethesda Research Laboratories) and following the manufacturer’s suggested protocols. The template was pRAT1. Following a 5-min denaturation at 95°C, two cycles of 1 min at 42°C, 2 min at 65°C, and 30 s at 95°C were followed by 25 cycles of 1 min at 55°C, 2 min at 65°C, and 30 s at 95°C. The vector pBSKS+ was cut at the EcoRV site and T tailed (23), and the PCR product was ligated into this vector so that rsaD and rsaE would be in the same orientation as the lacZ promoter of pBSKS+. This construct was called pRAT5.

Plasmid pBBR5 was constructed from plasmids pBBR1MCS (25) and pHP45Ω-Tc (17). The Ω-Tc fragment from pHP45Ω-Tc was removed by using HindIII, and the ends were blunted by using T4 polymerase. A 0.3-kbp portion of the Cmr-encoding gene was removed from pBBR1MCS by cutting with DraI and replaced with the blunted Ω-Tc fragment, producing a Tcr broad-host-range vector that replicates in C. crescentus.

Plasmid pRAT4ΔH was made by removing the ClaI-HindIII fragment from pTZ18UB:rsaΔP and replacing it with the ClaI-HindIII fragment from pRAT1 containing the C terminus of rsaA and the complete rsaD and rsaE genes.

Tn5 mutagenesis.

Tn5 mutagenesis was accomplished by using narrow-host-range (ColE1 replicon) plasmid pSUP2021 (37), which is not maintained in C. crescentus. The plasmid was introduced by electroporation, 20,000 colonies that were streptomycin and kanamycin resistant were pooled and frozen at −70°C, and aliquots were used for subsequent screening.

Southern blot analysis of chromosomal DNA isolated from the Tn5 library was used to assess the randomness of insertions. Hybridization with a Tn5 probe indicated that while there were some hot spots of Tn5 integration, Tn5 distribution was reasonably random throughout the chromosome (data not shown).

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and Western immunoblot analysis were done as previously described (45). After transfer of proteins to nitrocellulose, the blots were probed with a polyclonal antibody and antibody binding was visualized by using goat anti-rabbit serum coupled to horseradish peroxidase and color-forming reagents (38).

To detect those C. crescentus whole cells synthesizing an S-layer, a Western colony blot assay was used (6). Briefly, cell material was transferred to nitrocellulose by pressing the membrane onto the surface of an agar plate. The membrane was air dried for 10 to 15 min, washed in a blocking solution (38) with vigorous agitation on a rotary shaker, and then processed in the standard fashion (38).

Surface protein from C. crescentus cells was extracted by using pH 2.0 HEPES buffer as described by Walker et al. (45). To compare the amounts of surface protein extracted from different mutants, equal amounts of cells growing at log phase were harvested and equal amounts of the protein extract were loaded onto the protein gel.

Isolation of DNA 3′ of rsaA.

The NA1000 cosmid library was probed with radiolabelled rsaA; 11 cosmid clones hybridizing to the probe were isolated. Southern blot analysis was used to determine which cosmids contained DNA 3′ of rsaA. An 11.7-kb SstI-EcoRI fragment containing rsaA plus 7.3 kb of 3′ DNA was isolated from one of the cosmids and cloned into the SstI-EcoRI site of pBSKS+; the resulting plasmid was named pRAT1. The 3′ end of the cloned fragment consisted of 15 bp of pLAFR5 DNA containing Sau3AI, SmaI; and EcoRI sites.

Nucleotide sequencing and sequence analysis.

BamHI fragments from pRAT1 were subcloned into the BamHI site of vector pTZ18R for sequencing. The 3′-end fragment was subcloned into pTZ18R by using BamHI and EcoRI. The 5′-end fragment was subcloned into pTZ18R by using SstI and HindIII. Sequencing was performed on a DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems model 373). After use of universal primers, additional sequence was obtained by “walking along” the DNA using 15-bp primers based on the acquired sequence. Nucleotide and amino acid sequence data were analyzed by using Geneworks and MacVector software (Oxford Molecular Group) and the National Center for Biotechnology Information BLAST e-mail server using the BLAST algorithm (2). Protein alignments were generated by using the ClustalW algorithm as implemented by the MacVector software and using the default settings.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequences for rsaD and rsaE have been submitted to GenBank and assigned accession no. AF062345.

RESULTS

Identification of Tn5 mutants lacking an S-layer.

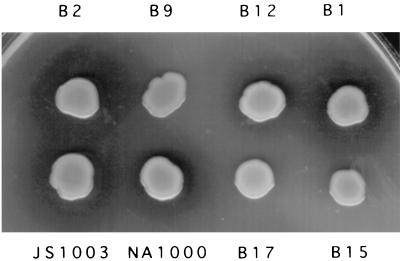

A pooled Tn5 library was screened for S-layer-negative mutants by using a Western colony immunoblot assay (see Materials and Methods). The polyclonal primary antibodies used were α-RsaA (45) and α-S-LPS (44). α-RsaA reacts to RsaA, and α-S-LPS reacts to the S-LPS required for anchoring of the S-layer to the surface of the bacterium (44). When α-RsaA was used, colonies with an S-layer reacted with the antibody and appeared as a spot on the blot (Fig. 1). It was also found that a halo could be detected around colonies when the S-layer could not anchor to the cells (e.g., cells with a defective S-LPS). It appears that the shed S-layer diffused away from the colony and was detected in the Western colony blot as a ring around the colony (Fig. 1). These are not further described in this report. When α-S-LPS was used, the antibody only reacted to exposed S-LPS when the cells of a colony lacked an S-layer; the S-layer blocks the binding of α-S-LPS. RsaA appears to be completely degraded when it is not secreted (5, 8); therefore, cell lysis during this procedure and release of unsecreted RsaA were not a concern. In sum, by using this method, it was possible to differentiate among cells secreting RsaA, cells secreting and shedding an S-layer, and cells without an S-layer.

FIG. 1.

Sample colony immunoblot using anti-S antibody. NA1000 has an S-layer, JS1003 does not, and JS1001 sheds the S-layer, forming a halo around the colony. B1, B2, and B5 represent samples of the S-layer-negative Tn5 mutants that were found.

In total, 9,000 colonies from the pooled Tn5 mutant library were screened by using the α-S-LPS antibody and 22,000 colonies were screened by using α-RsaA. Seventeen Tn5 S-layer-negative mutants were found. SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates and culture supernatants confirmed that no S-layer was found in or on the cells or in the culture supernatant of these mutants (data not shown).

Identification of Tn5 mutants defective in RsaA secretion.

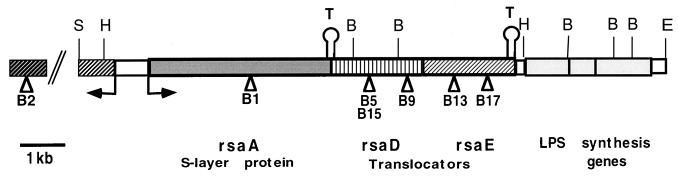

Several possible Tn5 insertion events in addition to those in the secretion genes could result in an S-layer-negative phenotype. To screen out Tn5 insertions in the rsaA gene, Southern blot analysis was performed on the S-layer-negative mutants. Eleven of the mutants were caused by insertions in rsaA and were not further characterized. One mutant, B12, was originally picked as having no S-layer but, on further examination, was found to have an S-layer and was kept for use as a random Tn5 mutant. Five mutants, B5, B9, B13, B15, and B17, were caused by insertions in the DNA immediately 3′ of rsaA, and one mutant, B2, was located elsewhere on the chromosome (Fig. 2). These last six mutants were possible RsaA translocator mutants.

FIG. 2.

Graphic representation of the DNA examined in this study. A triangle represents the approximate location of a Tn5 insertion, a T indicates a terminator, and an arrow indicates a promoter. Restriction enzyme sites: B, BamHI; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; S, SstI. Boxes containing patterns are ORFs or genes, as indicated below the diagram.

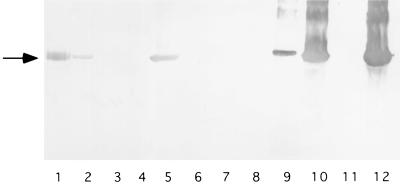

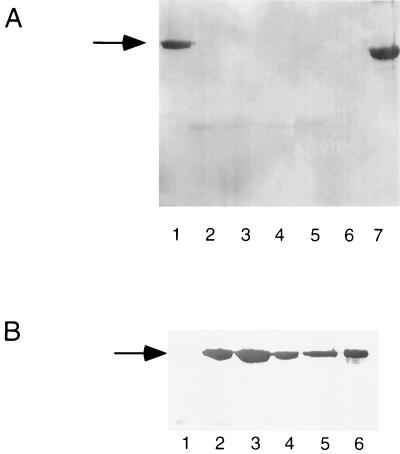

To determine that loss of the S-layer was not caused by a mutation affecting the regulation of RsaA, such as a transcription regulator, rsaA, was expressed in the mutants under the control of a lacZ promoter by using plasmid pRK415rsaAΔPK. This construct restored RsaA production in JS1003, a mutant with an interrupted rsaA gene, although wild-type RsaA expression levels were not reached. An S-layer was produced in mutants that had a Tn5 insertion in rsaA and none of the five mutants with a Tn5 insertion in the DNA immediately 3′ of rsaA secreted RsaA when rsaA was present in trans in this manner (Fig. 3). Secretion was not restored to full wild-type levels in either JS1003 or B1 with plasmid pRK415rsaAΔPK.

FIG. 3.

Complementation of Tn5 mutants with rsaA. Protein was extracted from the surfaces of the Tn5 mutants and JS1003 carrying plasmid pRK415rsaAΔPK, which expresses rsaA under the control of the lac promoter. Protein was also extracted from the surfaces of the wild type and rsaA knockout mutants that did not contain any plasmid to demonstrate differences in expression. Equal amounts of surface extracts were loaded onto the gel, and a Western blot was performed by using a polyclonal antibody against RsaA. Lanes: 2 through 10, surface extracts from cells containing plasmid pRK415rsaAΔPK (PK); 1, purified RsaA; 2, JS1003 (PK); 3, B9 (PK); 4, B13 (PK); 5, B1 (PK) (a Tn5 insertion in rsaA); 6, B5 (PK); 7, B15 (PK); 8, B17 (PK); 9, B2 (PK); 10, B12 (PK) (a random Tn5 insertion); 11, JS1003 (rsaA); 12, NA1000 (wild type). The arrow indicates full-length RsaA.

In addition, the one mutant, B2, in which the Tn5 insertion was not adjacent to the rsaA gene also produced an S-layer. This indicates that the B2 insertion was not in a gene involved in RsaA secretion. B2 may have an interruption in a gene responsible for the regulation of RsaA production or, more likely, the Tn5 insertion mutation is irrelevant and there was a secondary point mutation in rsaA.

Isolation and sequencing of DNA near rsaA.

By using the locations of Tn5 insertions disrupting RsaA secretion and a previously constructed cosmid library (see Materials and Methods), a DNA fragment containing rsaA plus 7.3 kb of 3′ DNA was isolated; cloned into pBSKS+, forming pRAT1; and sequenced to search for translocator genes. An open reading frame (ORF) was found 5′ of rsaA, confirming earlier results (18), and five ORFs were found 3′ of rsaA (Fig. 2).

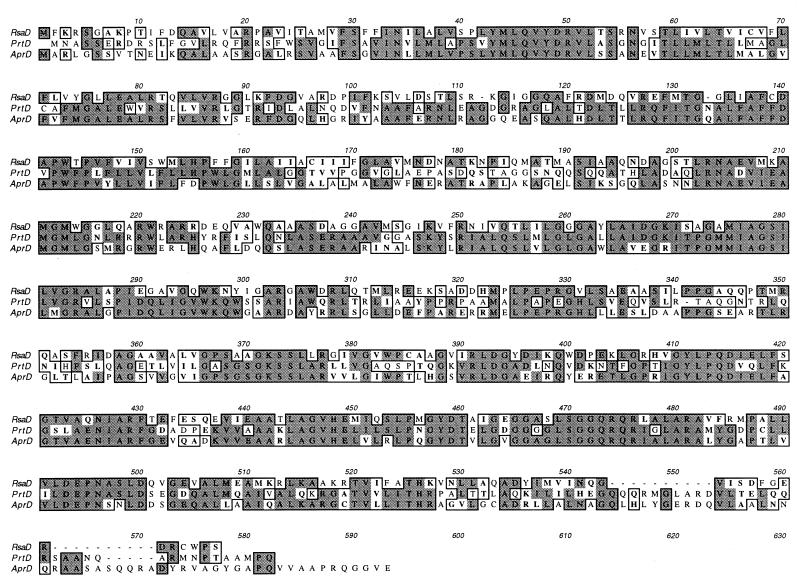

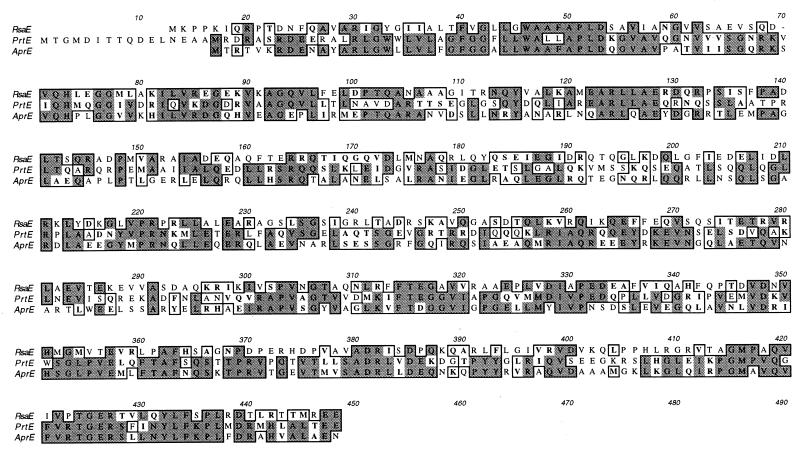

A search of gene and protein databases showed that there were two ORFs immediately 3′ of rsaA that encoded proteins with significant similarity to the ABC transporter and MFPs of two type I secretion systems: the alkaline protease transport system of P. aeruginosa (22) and the metalloprotease transport system of E. chrysanthemi (28) (Fig. 4 and 5).

FIG. 4.

Alignment of RsaD with AprD and PrtD using the ClustalW algorithm implemented by the program MacVector 6.0. Identical and similar amino acids are boxed. Identical amino acids are shaded. Similar amino acids are in boldface. The ABC transporter protein is represented by PrtD for metalloprotease transport in E. chrysanthemi and AprD for alkaline protease transport in P. aeruginosa.

FIG. 5.

Alignment of RsaE with AprE and PrtE by using the ClustalW algorithm implemented by the program MacVector 6.0. Identical and similar amino acids are boxed. Identical amino acids are shaded. Similar amino acids are in boldface. The MFP is represented by PrtE in E. chrysanthemi and by AprE in P. aeruginosa.

The first ORF was 1,656 bp long and started 242 bp after the termination codon of rsaA. This ORF was predicted to code for a 555-amino-acid protein with a predicted molecular mass of 59.8 kDa. The predicted protein is 46% identical and 69% similar to AprD from P. aeruginosa and 33% identical and 62% similar to PrtD from E. chrysanthemi. The gene was designated rsaD because of its similarity to these genes (Fig. 4). RsaD does not appear to have an N-terminal signal sequence but does exhibit several N-terminal hydrophobic domains that may be transmembrane regions and a possible ATP binding site in the C-terminal half of the protein.

The second ORF started 146 bp after rsaD, contained 1,305 bp, and encoded a protein of 435 residues with a predicted molecular mass of 48 kDa. The predicted protein is 28% identical and 50% similar to AprE from P. aeruginosa and 29% identical and 52% similar to PrtE from E. chrysanthemi. The gene was designated rsaE because of its similarity to these genes (Fig. 5). In contrast to RsaD, RsaE was predicted to have a typical N-terminal signal sequence.

With respect to transcription-translation initiation-termination signals, (i) there was no indication of a promoter immediately 5′ of either rsaD or rsaE, suggesting that they may be part of a polycistron which includes rsaA; (ii) there were possible ribosome binding sites 7 bp upstream of the rsaD ATG initiation codon and 8 bp upstream of the rsaE ATG initiation codon; and (iii) there was a putative rho-independent terminator immediately after the stop codon of rsaE.

Three more ORFs were found 3′ of rsaE. None of these ORFs encoded proteins similar to the third component of type I secretion systems. Instead, these ORFs encoded proteins similar to those involved in the synthesis of perosamine, a dideoxyaminohexose. The first ORF encoded a protein with similarity to GDP–d-mannose dehydratase (11, 41), the second ORF encoded a protein with similarity to UDP–N-acetylglucosamine acyltransferase (10, 43), and the third protein had similarity to perosamine synthetase (3, 41).

Complementation of secretion-defective Tn5 mutants.

To demonstrate that the Tn5 insertions were definitively responsible for the secretion defect, we attempted to complement the Tn5 mutants in trans. We first used cosmid 17A7, which contained the entire RSA operon, to attempt to complement the mutants. All attempts at complementation using this cosmid were unsuccessful, including an attempt to restore RsaA production in JS1003 (which contains an inactivated rsaA gene). Since RsaA production in JS1003 can be restored with other plasmids containing rsaA, we believe that something pertaining to the nature of the cosmid prevented complementation (see Discussion).

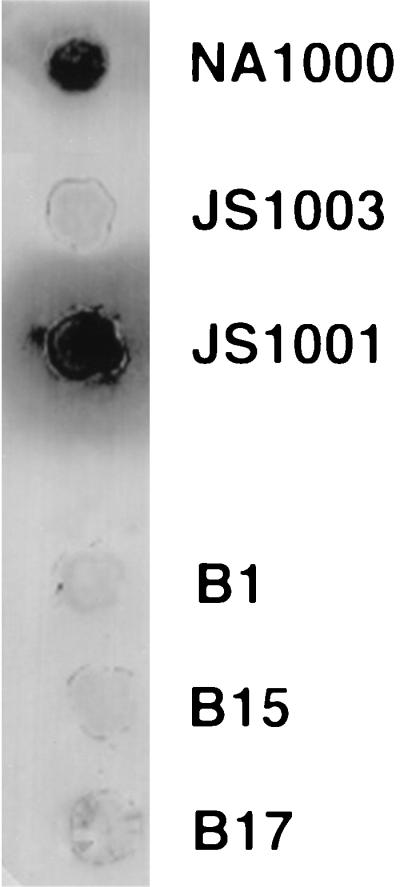

A PCR product containing genes rsaD and rsaE was generated and cloned into a suitable expression vector; the result was named pRAT5:PRK415 (see Materials and Methods). This plasmid was introduced into Tn5 mutants B15 and B17. With this plasmid, mutant B17 produced RsaA while, inexplicably, the B15 mutant did not (Fig. 6A).

FIG. 6.

Complementation of transport-deficient mutants using rsaD and rsaE. Western blots of surface-extracted protein using anti-S antibody. (A) Lanes: 1, B17 (DE); 2, B15 (DE); 3, B1 (DE); 4, B17 (17A7); 5, B15 (17A7); 6, JS1003; 7, NA1000. DE indicates that the cells carried plasmid pRAT5:pRK415 containing the genes rsaD and rsaE. 17A7 indicates that the cells carry cosmid 17A7 containing the entire RSA operon. Equal amounts of surface extract were loaded in all lanes. (B) Lanes: 1, B1 (DE); 2, B5 (DE); 3, B9 (DE); 4, B15 (DE); 5, B17 (DE); 6; NA1000. DE indicates that the cells carry plasmid pRAT5:pBBR5 expressing the genes rsaD and rsaE. Equal amounts of surface extract were loaded in all lanes except 6, where there was only one-quarter of the amount loaded in the other lanes. The arrow indicates full-length RsaA.

To address the problems with B15 complementation, a new Tcr broad-host-range vector, pBBR5, was constructed. It was hoped that this vector would have a different copy number and expression level that would alleviate the problems encountered when using pRK415 or pLAFR5. Two plasmids were constructed by using this vector (see Materials and Methods). pRAT5:PBBR5 transcribed the rsaD and rsaE genes by using the lacZ promoter. pRAT4ΔH:PBBR5 transcribed the rsaA, rsaD, and rsaE genes by using the lacZ promoter. When pRAT5:PBBR5 was introduced into mutants B1, B5, B9, B15, and B17, Western blot analysis showed that the mutants with defective rsaD and rsaE genes expressed RsaA on the surface while rsaA mutant B1 did not (Fig. 6B). When pRAT4ΔH:PBBR5 was expressed in the same mutants, RsaA was only found on the surfaces of mutants B1 and B17 (data not shown).

Secretion of the P. aeruginosa and E. chrysanthemi proteases by the RsaA secretion machinery.

Due to the close similarity of the RsaD and RsaE proteins to those of cognate type I secretion proteins of P. aeruginosa and E. chrysanthemi, it seemed possible that the proteases transported by these systems would be transported by the C. crescentus secretion machinery. To test this idea, metalloprotease gene prtB and alkaline protease gene aprA were expressed in C. crescentus by introducing these genes on plasmids pRUW500:pRK415 and pTZ18RaprA:pRK415 into strains NA1000 and JS1003, as well as the NA1000 Tn5 mutants. The secreted proteases formed a halo around a colony on a skim milk plate. Normally, C. crescentus does not form halos, even when allowed to grow for over a week, a time when significant cell lysis is expected to occur (data not shown). The proteases were not secreted in the mutants in which the rsaD and rsaE sequences were interrupted with Tn5 but were secreted in active form when the Tn5 interruption was in the rsaA gene (Fig. 7). The proteases were secreted at lower levels in wild-type strain NA1000 and S-layer-producing mutant B12, compared to mutant JS1003 or B1, in which the rsaA gene has been interrupted, suggesting that there was competition between RsaA and PrtB for the secretion machinery, further supporting the supposition that RsaD and RsaE are parts of a type I secretion mechanism. Identical results were found when aprA was expressed in the Tn5 mutants (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Expression of prtB in C. crescentus. PrtB was expressed in all of the colonies shown by using plasmid pRK415:pRUW500. The cells were spotted onto PYE plates containing 1% skim milk. Halos around colonies indicate that active PrtB is being secreted. Note that NA1000 and B12 cells are producing RsaA, as well as PrtB, and that the halos surrounding these colonies are smaller.

DISCUSSION

Analysis of the region 3′ of rsaA revealed the presence of two genes (rsaD and rsaE) encoding proteins with significant similarity to components of the type I secretion systems used by P. aeruginosa and E. chrysanthemi to secrete two different extracellular proteases (22, 28). Because interruption of rsaD and rsaE eliminated secretion of RsaA and the defects could be restored by complementation, it was apparent that their gene products make up part of the RsaA translocator machinery.

This appears to be the first reported example of an S-layer that is secreted by a type I secretion system, although we recently learned that the S-layer of Campylobacter fetus may also be transported in this manner (8a). If this is so, it is notable that the C. fetus S-layer protein has several features in common with that of C. crescentus. It is produced by a free-living, gram-negative bacterium, is hexagonally packed, anchors to the cell surface via its N terminus to a particular species of LPS (7, 15, 44), and so far has the greatest similarity of any S-layer protein to RsaA (20).

The genes for the ABC transporter and the MFP components of type I secretion systems are generally found in an operon that includes the transported protein (4, 35); in this respect, then, the organization of the rsaA, rsaD, and rsaE genes was not surprising. In contrast, the gene encoding the OMP component of type I secretion systems may or may not be closely linked to the other secretion genes. Since sequencing immediately 3′ of rsaD and rsaE has revealed ORFs that are most likely involved in S-LPS O-antigen biosynthesis and are not candidates for the third component, it is apparent that the third component is located at least many kilobases away from the region described here. We are currently exploring methods of identifying the OMP component and heterologous complementation with other type I secretion components. RsaA, RsaD, and RsaE have been expressed in E. coli strains carrying TolC, the E. coli OMP involved in hemolysin secretion, without successful secretion of RsaA (unpublished data).

The ORFs identified 3′ of rsaE all have significant identity to genes in Vibrio cholerae that encode proteins of the perosamine biosynthetic pathway (41). The structure of C. crescentus S-LPS has been studied in this laboratory and found to contain a dideoxyamino hexose (34). These sequencing results and the proximity to the RSA operon suggest that this sugar may be perosamine, which is a dideoxyamino hexose.

While it was possible to complement a secretion defect by using genes rsaD and rsaE, complementation did not restore secretion to wild-type levels and it was not possible to restore secretion in some instances. One reason may be due to the necessity of using tetracycline to maintain the cosmid. Tn5 confers resistance to kanamycin and streptomycin, so it was necessary to use another antibiotic; tetracycline was the only practical alternative. C. crescentus cells carrying a Tcr-encoding gene appear to be anomalous by microscopy. The cells are often severely elongated, and there are few motile cells. It was difficult to grow cultures carrying Tcr plasmids with the RSA genes to densities high enough for extraction of sufficient protein to be seen on the Western blot. Furthermore, the fact that cosmid 17A7, carrying the entire RSA operon, could not complement the JS1003 mutant, even though other constructs can be used to complement the rsaA defect, suggested that some factor related to the cosmid is responsible for the inability to complement.

It was puzzling that the B15 mutant was not complemented by pRAT5:pRK415, while B17 was complemented. One possibility might be that the B15 mutant makes a partial product that interacts with the other transporter components but cannot make a fully functional transporter complex and not enough protein is expressed from the plasmid to dilute out this effect (i.e., that a dominant effect is caused by a truncated gene product). Transcription of rsaD and rsaE was driven by the lac promoter on plasmid pRAT5:PRK415 and by the native promoter on the cosmid. This may have resulted in a larger amount of protein being produced from the plasmid than from the cosmid. Plasmid pRAT5:pBBR5 complemented B15 and a number of other mutants. Vector pBBR5 is considerably smaller than pRK415 and, in preliminary experiments, appeared to have a higher copy number (data not shown), which may result in larger amounts of RsaD and RsaE in the cell, diluting out the effects of truncated proteins more effectively than pRAT5:pRK415. Further, plasmid pRAT4ΔH:pBBR5 did not complement any of the rsaD and rsaE mutants except B17. In this plasmid, rsaD and rsaE either are transcribed by their wild-type promoter or are likely transcribed as part of the rsaA transcript as described below. In either case, a lesser transcript amount would be produced than from the lacZ promoter of pRAT5:pBBR5, making the construct less effective in diluting the effect of a truncated gene product.

rsaA contains a potential rho-independent terminator sequence at the end of the coding region (21). This predicted terminator results in a predicted transcript that matched closely the size of a transcript found by Northern blot analysis (18). In this study, we found no obvious indications of a promoter immediately 5′ of either the rsaD or rsaE gene. It may be that transcription of rsaD and rsaE is similar to transcription of the hlyA, hlyB, and hlyD genes, where a similar rho-independent terminator is found after the hlyA gene, and most transcripts terminate at this point. An antiterminator, RfaH, prevents termination, and when it does, a larger transcript including the hlyB and hlyD genes is made (27). Transcription of the E. chrysanthemi protease secretion genes appears to be accomplished by a similar method (28), and we postulate that the same is true for the RSA operon. A transcription pattern like this may account for the reduced expression found in the JS1003 and B1 mutants when they are complemented with rsaA. The kanamycin fragment interrupting rsaA in JS1003 does not have a transcription terminator and may transcribe through to the end of rsaE, resulting in a transcript 1.5 kb longer than that of the wild type, which would likely be more unstable and result in fewer transport complexes. In B1, it is likely that rsaD and rsaE are transcribed off one of the Tn5 promoters, resulting in decreased transcript amounts and, in turn, transport complexes.

Type I secretion systems can be grouped into families. The RTX toxins, such as α-hemolysin (E. coli) and leukotoxin (Pasteurella haemolytica), make up one family, while extracellular proteases (e.g., AprA and PrtB), lipases, and some other proteins constitute another (4). Within the families, there is high sequence similarity and the components can be interchanged without a dramatic drop in protein transport, but when they are interchanged between families, protein transport drops significantly. Because we have demonstrated that proteins AprA and PrtB can be secreted from C. crescentus in active form, there is competition for the secretion apparatus between the proteases and RsaA and there is higher sequence similarity between these proteins than with RTX toxins, presumably, RsaA can likely be grouped with the protease family. It is of continuing interest to us to determine the features common to these metalloproteases and RsaA that allow transport to occur.

RsaA accounts for a large portion (10 to 12%) of the cellular protein. As far as we can determine, the RsaA secretion machinery secretes a larger fraction of the total cell protein than any other known type I secretion mechanism. This high level of protein production is apparently necessary to keep the cell completely covered with S-layer at all times and is similar to the levels noted for other bacterial S-layer proteins (31). This means that the RsaA secretion machinery is either more efficient than that of other type I secretion systems or a larger number of transport complexes exist in the membranes or a combination of both factors. This question is an important one to answer because we are currently engaged in evaluating the potential of the S-layer protein secretion system for the secretion of heterologous proteins and peptides in a biotechnological context (6, 7).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Lucy Shapiro, Stanford University, for providing the NA1000 cosmid library and Stephen G. Walker for creating the NA1000 Tn5 library. We thank Phillippe Delepelaire for providing plasmid pRUW500. We thank Maryse Murgier for providing plasmid pJUEK72. We thank Wade Bingle for plasmid pUC9NC. We thank John F. Nomellini for making plasmid pBBR5 and for numerous useful discussions during this project. We thank Jerry Awram, Teri Babcock, Wade Bingle, and John F. Nomellini for reviewing the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alley M R, Gomes S L, Alexander W, Shapiro L. Genetic analysis of a temporally transcribed chemotaxis gene cluster in Caulobacter crescentus. Genetics. 1991;129:333–341. doi: 10.1093/genetics/129.2.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bik E M, Bunschoten A E, Willems R J, Chang A C, Mooi F R. Genetic organization and functional analysis of the otn DNA essential for cell-wall polysaccharide synthesis in Vibrio cholerae O139. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:799–811. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binet R, Letoffe S, Ghigo J M, Delepelaire P, Wandersman C. Protein secretion by Gram-negative bacterial ABC exporters—a review. Gene. 1997;192:7–11. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00829-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bingle W H, Le K D, Smit J. The extreme N-terminus of the Caulobacter crescentus surface-layer protein directs export of passenger proteins from the cytoplasm but is not required for secretion of the native protein. Can J Microbiol. 1996;42:672–684. doi: 10.1139/m96-092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bingle W H, Nomellini J F, Smit J. Cell-surface display of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain K pilin peptide within the paracrystalline S-layer of Caulobacter crescentus. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:277–288. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5711932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bingle W H, Nomellini J F, Smit J. Linker mutagenesis of the Caulobacter crescentus S-layer protein: toward a definition of an N-terminal anchoring region and a C-terminal secretion signal and the potential for heterologous protein secretion. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:601–611. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.601-611.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bingle W H, Smit J. Alkaline phosphatase and a cellulase reporter protein are not exported from the cytoplasm when fused to large N-terminal portions of the Caulobacter crescentus surface (S)-layer protein. Can J Microbiol. 1994;40:777–782. doi: 10.1139/m94-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8a.Blaser, M. Personal communication.

- 9.Boot H J, Pouwels P H. Expression, secretion and antigenic variation of bacterial S-layer proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:1117–1123. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.711442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canter Cremers H, Spaink H P, Wijfjes A H, Pees E, Wijffelman C A, Okker R J, Lugtenberg B J. Additional nodulation genes on the Sym plasmid of Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viciae. Plant Mol Biol. 1989;13:163–174. doi: 10.1007/BF00016135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Currie H L, Lightfoot J, Lam J S. Prevalence of gca, a gene involved in synthesis of A-band common antigen polysaccharide in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin Diag Lab Immunol. 1995;2:554–562. doi: 10.1128/cdli.2.5.554-562.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delepelaire P, Wandersman C. Protein secretion in gram-negative bacteria. The extracellular metalloprotease B from Erwinia chrysanthemi contains a C-terminal secretion signal analogous to that of Escherichia coli alpha-hemolysin. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:17118–17125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dinh T, Paulsen I T, Saier M H., Jr A family of extracytoplasmic proteins that allow transport of large molecules across the outer membranes of gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3825–3831. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.13.3825-3831.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duong F, Lazdunski A, Murgier M. Protein secretion by heterologous bacterial ABC-transporters: the C-terminus secretion signal of the secreted protein confers high recognition specificity. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:459–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dworkin J, Tummuru M K R, Blaser M J. A lipopolysaccharide-binding domain of the Campylobacter fetus S-layer protein resides within the conserved N terminus of a family of silent and divergent homologs. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1734–1741. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.7.1734-1741.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards P, Smit J. A transducing bacteriophage for Caulobacter crescentus uses the paracrystalline surface layer protein as a receptor. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5568–5572. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.17.5568-5572.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fellay R, Frey J, Krisch H. Interposon mutagenesis of soil and water bacteria: a family of DNA fragments designed for in vitro insertional mutagenesis of gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1987;52:147–154. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fisher J A, Smit J, Agabian N. Transcriptional analysis of the major surface array gene of Caulobacter crescentus. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4706–4713. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.10.4706-4713.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghigo J M, Wandersman C. Cloning, nucleotide sequence and characterization of the gene encoding the Erwinia chrysanthemi B374 PrtA metalloprotease: a third metalloprotease secreted via a C-terminal secretion signal. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;236:135–144. doi: 10.1007/BF00279652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilchrist A, Fisher J A, Smit J. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the gene encoding the Caulobacter crescentus paracrystalline surface layer protein. C J Microbiol. 1992;38:193–202. doi: 10.1139/m92-033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilchrist A, Smit J. Transformation of freshwater and marine caulobacters by electroporation. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:921–925. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.921-925.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guzzo J, Murgier M, Filloux A, Lazdunski A. Cloning of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa alkaline protease gene and secretion of the protease into the medium by Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:942–948. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.942-948.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holton T A, Graham M W. A simple and efficient method for direct cloning of PCR products using ddT-tailed vectors. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:1156. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.5.1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keen N T, Tamaki S, Kobayashi D, Trollinger D. Improved broad-host-range plasmids for DNA cloning in gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1988;70:191–197. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kovach M E, Phillips R W, Elzer P H, Roop R M, Peterson K M. pBBR1MCS: a broad-host-range cloning vector. BioTechniques. 1994;16:800–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koval S F, Hynes S H. Effect of paracrystalline protein surface layers on predation by Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2244–2249. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.7.2244-2249.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leeds J A, Welch R A. RfaH enhances elongation of Escherichia coli hlyCABD mRNA. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1850–1857. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.1850-1857.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Letoffe S, Delepelaire P, Wandersman C. Protease secretion by Erwinia chrysanthemi: the specific secretion functions are analogous to those of Escherichia coli alpha-haemolysin. EMBO J. 1990;9:1375–1382. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08252.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Letoffe S, Wandersman C. Secretion of CyaA-PrtB and HlyA-PrtB fusion proteins in Escherichia coli: involvement of the glycine-rich repeat domain of Erwinia chrysanthemi protease B. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4920–4927. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.15.4920-4927.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mead D A, Szczesna-Skorupa E, Kemper B. Single-stranded DNA ’blue’ T7 promoter plasmids: a versatile tandem promoter system for cloning and protein engineering. Protein Eng. 1986;1:67–74. doi: 10.1093/protein/1.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Messner P, Sleytr U B. Crystalline bacterial cell-surface layers. Adv Microb Physiol. 1992;33:213–275. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nomellini J F, Kupcu S, Sleytr U B, Smit J. Factors controlling in vitro recrystallization of the Caulobacter crescentus paracrystalline S-layer. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6349–6354. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6349-6354.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pugsley A P. The complete general secretory pathway in gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:50–108. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.1.50-108.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ravenscroft N, Walker S G, Dutton G S, Smit J K. Identification, isolation, and structural studies of the outer membrane lipopolysaccharide of Caulobacter crescentus. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7595–7605. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.23.7595-7605.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salmond G P, Reeves P J. Membrane traffic wardens and protein secretion in gram-negative bacteria. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:7–12. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simon R, Priefer U, Puhler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:784–790. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smit J, Agabian N. Cloning of the major protein of the Caulobacter crescentus periodic surface layer: detection and characterization of the cloned peptide by protein expression assays. J Bacteriol. 1984;160:1137–1145. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.3.1137-1145.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smit J, Engelhardt H, Volker S, Smith S H, Baumeister W. The S-layer of Caulobacter crescentus: three-dimensional image reconstruction and structure analysis by electron microscopy. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6527–6538. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.20.6527-6538.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smit J, Grano D A, Glaeser R M, Agabian N. Periodic surface array in Caulobacter crescentus: fine structure and chemical analysis. J Bacteriol. 1981;146:1135–1150. doi: 10.1128/jb.146.3.1135-1150.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stroeher U H, Karageorgos L E, Brown M H, Morona R, Manning P A. A putative pathway for perosamine biosynthesis is the first function encoded within the rfb region of Vibrio cholerae O1. Gene. 1995;166:33–42. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00589-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vieira J, Messing J. The pUC plasmids, an M13mp7-derived system for insertion mutagenesis and sequencing with synthetic universal primers. Gene. 1982;19:259–268. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vuorio R, Harkonen T, Tolvanen M, Vaara M. The novel hexapeptide motif found in the acyltransferases LpxA and LpxD of lipid A biosynthesis is conserved in various bacteria. FEBS Lett. 1994;337:289–292. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80211-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walker S G, Karunaratne D N, Ravenscroft N, Smit J. Characterization of mutants of Caulobacter crescentus defective in surface attachment of the paracrystalline surface layer. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6312–6323. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.20.6312-6323.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walker S G, Smith S H, Smit J. Isolation and comparison of the paracrystalline surface layer proteins of freshwater caulobacters. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1783–1792. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.6.1783-1792.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]