Abstract

Despite the fact that the extreme thermophilic bacteria belonging to the genus Thermus are classified as strict aerobes, we have shown that Thermus thermophilus HB8 (ATCC 27634) can grow anaerobically when nitrate is present in the growth medium. This strain-specific property is encoded by a respiratory nitrate reductase gene cluster (nar) whose expression is induced by anoxia and nitrate (S. Ramírez-Arcos, L. A. Fernández-Herrero, and J. Berenguer, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1396:215–1997). We show here that this nar operon can be transferred by conjugation to an aerobic Thermus strain, enabling it to grow under anaerobic conditions. We show that this transfer takes place through a DNase-insensitive mechanism which, as for the Hfr (high frequency of recombination) derivatives of Escherichia coli, can also mobilize other chromosomal markers in a time-dependent way. Three lines of evidence are presented to support a genetic linkage between nar and a conjugative plasmid integrated into the chromosome. First, the nar operon is absent from a plasmid-free derivative and from a closely related strain. Second, we have identified an origin for autonomous replication (oriV) overlapping the last gene of the nar cluster. Finally, the mating time required for the transfer of the nar operon is in good agreement with the time expected if the transfer origin (oriT) were located nearby and downstream of nar.

Most extreme thermophiles that live in geothermal environments are strict anaerobes (3, 11) as a consequence of the adaptation to the low solubility of oxygen at these temperatures. However, members of the genus Thermus constitute an exception to this general rule, being described taxonomically as strictly aerobic chemorganotrophs (2).

However, we recently showed that one of the most thermophilic isolates of this genus, Thermus thermophilus HB8, was able to grow anaerobically when nitrate was present in the medium. Biochemical and genetic evidence demonstrated that this ability was related to the synthesis of a membrane-bound respiratory nitrate reductase complex whose protein components, the α (NarG; 136 kDa), β (NarH; 57 kDa), and γ (NarI; 28 kDa) subunits, were homologous (about 48 to 50% sequence identity) to those from mesophilic facultative anaerobes (e.g., Escherichia coli). The genes encoding these subunits were located within a single operon (nar) that was induced under low oxygen concentrations when nitrate was present (21). In contrast to those described for most nitrate reducers, the product of nitrate respiration was secreted to the growth medium through an unknown transporter.

We also observed that even a closely related strain, such as T. thermophilus HB27, was unable to grow under such anaerobic conditions (21). Since the main difference between strains HB8 and HB27 of T. thermophilus is the absence of plasmids from the latter, the possibility that the nar operon could be encoded by a transferable genetic element, such as a plasmid, was considered.

In this article, we analyze this possibility and demonstrate that the ability to grow by nitrate respiration can be transferred to the aerobic strain T. thermophilus HB27 by conjugation. We also relate this ability to the integration of a nar-carrying conjugative plasmid into the chromosome of T. thermophilus HB8. Moreover, we show that, as for the Hfr strains of E. coli, this integrated plasmid can also mobilize other chromosomal genes in a time-dependent way.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, phages, plasmids, and growth conditions.

T. thermophilus HB8 (ATCC 27634) and a Thermus sp. strain (ATCC 27737) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, Md.). T. thermophilus HB27, Thermus aquaticus YT1 (ATCC 25104), and T. thermophilus BPL7 were generously provided by Y. Koyama, M. Bothe, and J. Fee, respectively. The mutant strains T. thermophilus HB8 slrA::kat (9), T. thermophilus HB8 slpM::kat (9), and T. thermophilus HB8 narGH::kat (21) were used for interrupted-mating experiments. E. coli JM109 [K-12 supE44 Δ(lac-proAB) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 F′ (traD36 proAB+ lacIqZΔM15)] and TG1 [supE Δ(nsdM-mcrB)5 (rK− McrB−) thi Δ(lac-proAB) F′ (traD36 proAB+ lacIqZΔM15)] were used for cloning. Plasmids pUC119 (27) and pKT1 (15), which contains a gene cassette encoding a thermostable kanamycin nucleotidyltransferase (kat), were used for subcloning and for the identification of oriV, respectively. Plasmid pMK18 (6) is a bifunctional E. coli-Thermus shuttle vector used as a control in transformation experiments.

For nar induction assays, static (microaerophilic) or stirred (aerobic) cultures of T. thermophilus HB8 were obtained by use of a rich medium (TB) containing 8 g of Trypticase (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.), 4 g of yeast extract (Oxoid, Hampshire, England), and 3 g of NaCl per liter of water, adjusted to pH 7.5 (8) and supplemented with 20 mM KNO3 when necessary. Anaerobic cultures were obtained by growing cells in the same medium in 10-ml tubes filled to the top with mineral oil (21). Kanamycin (30 μg/ml) or chloramphenicol (20 μg/ml) was added for selection when needed.

DNA isolation and labeling.

Standard methods were used to purify, analyze, and manipulate DNA (22). Uniformly 32P-labeled DNA probes were obtained by use of random hexanucleotide primers, [α-32P]dCTP (3,000 Ci/mmol) (Amersham Ibérica, Madrid, Spain), and the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I. Essentially, 150 to 200 ng of DNA probe was denatured by boiling and added to a 50-μl reaction mixture containing the hexanucleotides (6 units of optical density at 260 nm [OD260]/ml), dATP, dGTP, and dTTP (0.1 mM each), β-mercaptoethanol (6 mM), MgCl2 (20 mM), and bovine serum albumin (0.4 mg/ml) in 50 mM Tris-HCl–200 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7). The Klenow fragment (2 U) and 25 mCi of [α-32P]dCTP (3,000 Ci/mmol) were added to this mixture, and the labeling reaction was developed at 30°C for 10 h. After this period, unincorporated nucleotides were removed by chromatography in a Sephadex G-50 column. The radiactive probes used were as follows: probe A is a 1.2-kbp BamHI fragment containing 3′ and 5′ regions of narG and narH, respectively (21), and probe B is a 3.5-kbp KpnI/SalI fragment from plasmid pNIT9kat (this work).

PFGE.

After T. thermophilus cells were placed in 1% (wt/vol) agarose, intact DNA was obtained by the method described by Marin et al. (17). Plasmids were removed from these agarose plugs by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) for 36 h at 170 V/cm and a pulsing time of 150 s in 1% (wt/vol) agarose (SeaKem LE agarose; FMC) in TBE buffer (100 mM Tris, 100 mM boric acid, 0.2 mM EDTA [pH 8]) by use of a contour-clamped homogeneous electric field system (Pulsaphor apparatus; LKB) (4). Plugs containing only chromosomal DNA were then treated in situ with restriction enzyme NdeI (New England BioLabs) as described previously (17, 24), and the fragments obtained were subsequently separated by PFGE for 36 h at a field strength of 10 V/cm and a pulsing time of 40 s. After ethidium bromide staining, the sizes of the DNA fragments were calculated by comparison to lambda phage concatemers (50 kbp per monomer).

Southern blot analysis.

Essentially we followed the protocol described by Sambrook et al. (22). DNA fragments separated by agarose gel electrophoresis were capillary transferred for 16 h to a nylon membrane (Hybond N; Amersham) in 20× SSC buffer (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 20 mM sodium citrate). After UV cross-linking, hybridization was carried out for 16 h at 42°C with ∼2 × 106 cpm of an appropriate 32P-labeled DNA probe (see above) in 10 ml of hybridization solution (6× SSC, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 100 mg of denatured salmon sperm DNA per ml). Finally, nonspecifically bound probe was removed by washing in 2× SSC–0.1% SDS at 62°C, and the remaining radioactivity was detected by autoradiography at −70°C.

Construction of pNITkat plasmids and transformation.

The kat gene, encoding the thermostable kanamycin nucleotidyltransferase, was isolated from plasmid pKT1 and inserted into the PstI restriction site of the narI gene (21) to obtain plasmid pNIT9kat. From this plasmid, a 3.5-kbp KpnI/HindIII DNA fragment containing regions downstream of nar was cloned into the corresponding restriction sites of pUC119 to obtain plasmid pNIT5. Then, plasmids pNIT5kat1 and pNIT5kat2 were obtained by partial digestions with SmaI, followed by replacement with the kat gene cassette. Later, plasmids pNIT5kat1XSI and pNIT10kat were obtained from pNIT5kat2 by deletion of 0.6-kbp XhoI/SalI and 1.4-kbp EcoRI/HindIII DNA fragments, respectively.

Natural competence in T. thermophilus was induced by growing cells at 70°C with aeration to an OD550 of 0.5 in TB containing 1 mM MgCl2 and 0.5 mM CaCl2. Then, 0.5-ml aliquots of the culture were made, and plasmid DNA (1 μg) was immediately added. After 2 h of incubation, cells were plated on kanamycin (30 μg/ml)-containing plates and further incubated for 24 to 48 h at 70°C to obtain colonies. E. coli cells were made competent and transformed as described previously (5, 19).

DNA sequencing and computer analysis.

Plasmid DNA was sequenced by the dideoxy chain termination method (23). For the manual method, we used 7-deaza-dGTP, modified T7 DNA polymerase (Sequenase 2.0; U.S. Biochemicals), and [α-35S]dATP (1,000 Ci/mmol) (Amersham). For the automated method, sequences were obtained with an Applied Biosystems sequencer. Universal primers for M13mp and pUC vectors and oligonucleotides synthesized from partial sequences (Isogen Bioscience, Maarshen, Holland) were used for priming. Partial sequences were overlapped and analyzed with Wisconsin Genetics Computer Group software (7). Both strands of the template DNA were completely sequenced.

Horizontal transfer of the nar operon.

A chloramphenicol-resistant strain (T. thermophilus HB27Camr) was isolated directly by plating 108 T. thermophilus HB27 cells on plates containing chloramphenicol (20 μg/ml). For mating experiments, the donor (T. thermophilus HB8) and recipient (T. thermophilus HB27Camr) strains were mixed in a 100:1 (receptor/donor) ratio in 100 ml of TB medium containing KNO3 (20 mM) and incubated for 8 h at 70°C with low-speed stirring (100 rpm). A 500-μl sample of the culture was then inoculated into 100 ml of medium containing KNO3 (20 mM) and chloramphenicol (20 μg/ml) and incubated overnight at 70°C without stirring to allow the selection of exconjugants. Finally, cells from this culture were inoculated into capped test tubes containing 10 ml of nitrate medium overlaid with mineral oil up to the screw cap and incubated for 24 h at 70°C. The latter process was repeated five times to guarantee the isolation of an anaerobic culture. Parallel negative controls in which both donor and recipient strains were incubated separately and subjected to the same selective procedure were developed.

For interrupted mating, donors (different T. thermophilus HB8::kat derivatives) and recipients (T. thermophilus HB27Camr) were mixed as described above in a medium containing 6 mM MgCl2 and DNase I (100 μg/ml) to exclude the possibility of natural competence-mediated transfer. Aliquots (300 μl) of the mixtures were incubated at 70°C for different times before being vortexed vigorously. Then, 200 μl from each tube was added to 300 μl of prewarmed medium containing chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml) and incubated for 3 h at 70°C under strong aeration. Finally, 200 μl of this mixture was spread on kanamycin (30 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (20 μg/ml) agar plates and incubated for 48 h at 70°C.

SDS-PAGE and Western immunoblotting.

Protein samples were analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (14). For Western blotting, an antiserum raised against a C-terminal fragment of NarG was used (21). Specifically bound antibodies were detected with the enhanced chemiluminescence Western blotting analysis system from Amersham International.

Nitrate reductase activity.

The nitrate reductase activity of triplicate cell samples corresponding to an OD550 of 0.6 was measured after permeabilization with tetradecyltrimethylammonium (20% [wt/vol]) with methyl viologen as the electron donor (21, 25). One enzyme unit under these conditions was defined as the amount that produced 1 nmol of nitrite per min at 80°C.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

Accession number AJ225043 has been assigned by the EMBL gene bank to the nucleotide sequence of the oriV region that we studied (see Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Sequence of the minimal oriV region. The 837-bp SmaI-XhoI region contains an origin for autonomous replication in nar-carrying Thermus strains. The amino acid sequence shown below the DNA sequence corresponds to the C-terminal part of a protein homologous to the nitrite extrusion protein NarK. Inverted and direct repeats are labeled with arrows. Sites for restriction endonucleases SmaI and XhoI are also shown.

RESULTS

The nar operon is absent from most Thermus strains.

In order to check if the nitrate respiration ability shown by T. thermophilus HB8 was present in other strains of this genus, we inoculated the isolates Thermus sp. strain ATCC 27737, T. aquaticus YT1, T. thermophilus HB27, and T. thermophilus BPL7 and the nar mutant T. thermophilus HB8 narGH::kat (21) into TB medium containing nitrate and incubated them for 48 h at 70°C under anaerobic conditions. The results of such experiments demonstrated that none of these strains was able to grow under these conditions, while the control strain T. thermophilus HB8 grew to an OD550 of 0.8 (data not shown).

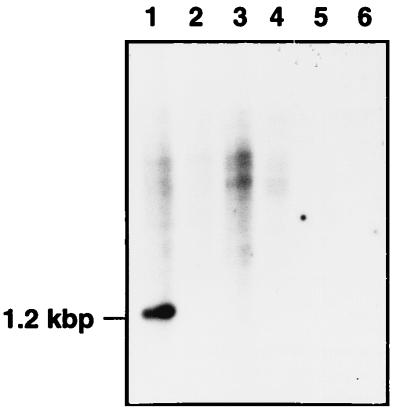

To check whether these results were related to the absence of the nar operon or were due to problems in its expression, we developed a parallel Southern blot of BamHI-digested total DNA from these strains by using 32P-probe A as a marker for the presence of the nar operon. As shown in Fig. 1, a 1.2-kbp labeled fragment detected in T. thermophilus HB8 (lane 1) was absent from all the other strains analyzed. As a negative control, we included the narGH::kat strain (Fig. 1, lane 2), an insertional derivative of T. thermophilus HB8 from which the fragment used as a probe was deleted (21).

FIG. 1.

The nar operon is strain specific. Southern blot of BamHI-digested total DNA of T. thermophilus HB8 (lane 1), T. thermophilus HB8 narGH::kat (lane 2), T. thermophilus BPL7 (lane 3), T. thermophilus HB27 (lane 4), Thermus sp. strain ATCC 27737 (lane 5), and T. aquaticus YT1 (ATCC 25104) (lane 6). The nar operon was detected with 32P-probe A.

The nar operon is horizontally transferred.

The results reported above, especially the absence of the nar operon from T. thermophilus BPL7, a plasmid-free derivative of T. thermophilus HB8 (18), suggested the likely location of the nar operon to be in a plasmid and prompted us to test its putative transfer to other aerobic Thermus strains.

To test this possibility in conjugation experiments, a chloramphenicol-resistant derivative of T. thermophilus HB27 (T. thermophilus HB27Camr) was used as a recipient and T. thermophilus HB8 was used as a donor (see Materials and Methods). After the 8-h mating period, nitrate-respiring and chloramphenicol-resistant strains were isolated by growing the cells consecutively under microaerophilic and completely anaerobic conditions. Parallel controls in the absence of the recipient were developed to check the possible selection of chloramphenicol-resistant derivatives of strain HB8 during this process.

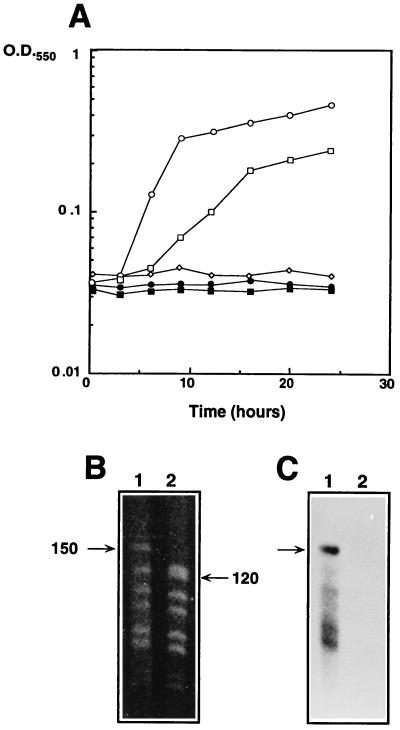

As shown in Fig. 2A, the chloramphenicol-resistant organism selected by this experiment (hereafter referred to as T. thermophilus HB27Camr::nar) was able to grow under anaerobic conditions with nitrate, while the parental recipient organism, T. thermophilus HB27Camr, was not.

FIG. 2.

Horizontal transfer of the nar operon. (A) Growth under anaerobic conditions of T. thermophilus HB8 (circles), T. thermophilus HB27Camr (diamonds), and the exconjugant T. thermophilus HB27Camr::nar (squares) in the presence (open symbols) or absence (closed symbols) of KNO3 (20 mM). (B) PFGE of NdeI-digested chromosomal DNA from T. thermophilus HB27Camr::nar (lane 1) and T. thermophilus HB27Camr (lane 2). (C) Southern blot of the PFGE sample shown in panel B labeled with probe A. Lanes are as in panel B. Numbers beside lanes in panel B are in kilobase pairs.

Aiming to identify the transferable genetic element carrying the nar operon, we analyzed by conventional agarose gel electrophoresis and Southern blotting the plasmid fractions of donor, recipient, and exconjugant strains. Unexpectedly, we did not detect any specific labeling with a nar probe (probe A) for these plasmid fractions (data not shown). Consequently, we tried to locate the nar operon in the chromosomes of these strains. To do this, we used two consecutive PFGE runs. The first one included long pulses to allow the plasmids to enter the agarose gel, while the chromosome remained in the origin (17). A parallel Southern blot showed that the nar operon was actually located in the chromosome of both the donor (T. thermophilus HB8) and the exconjugant (T. thermophilus HB27Camr::nar) strains. For the second run, agarose plugs containing only chromosomal DNA were treated in situ with NdeI and then subjected to PFGE to separate the resulting restriction fragments, followed by Southern blotting with probe A.

The results of this experiment (Fig. 2B) demonstrated that as a consequence of the transfer of the nar operon, a 120-kbp NdeI restriction fragment from recipient strain T. thermophilus HB27Camr (lane 2) changed its mobility up to 150 kbp in the exconjugant strain (lane 1). As this 150-kbp DNA fragment hybridized with the nar probe (Fig. 2C), we concluded that a DNA genetic element of at least 30 kbp containing the nar operon was mobilized from the chromosome of the donor strain to that of the recipient strain. Furthermore, the similarity between the NdeI digestion fragment profiles of the recipient and the exconjugant clearly identified the latter as a derivative of the former.

Expression of the nar operon in the exconjugant T. thermophilus HB27Camr::nar.

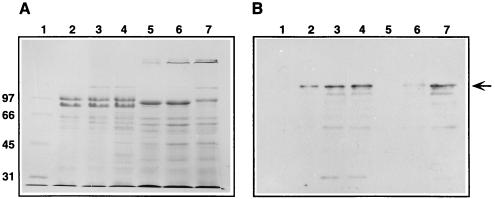

As shown in Fig. 3A, SDS-PAGE protein patterns of T. thermophilus HB8 (donor, lanes 2 to 4) were easily distinguishable from those of T. thermophilus HB27Camr (recipient, lane 5) and T. thermophilus HB27Camr::nar (exconjugant, lanes 6 and 7). In fact, the protein profiles of the recipient (Fig. 3A, lane 5) and the exconjugant (lanes 6 and 7) were almost identical, thus confirming their genetic relationship. However, a 140-kDa protein specifically detected in the exconjugant (Fig. 3A, lanes 6 and 7) was absent from the parental recipient (lane 5) but apparently present in T. thermophilus HB8 cells grown under microaerophilic (lane 3) and anaerobic (lane 4) conditions. A parallel Western blot (Fig. 3B) clearly identified this 140-kDa protein as NarG, the α subunit of the thermophilic nitrate reductase (21).

FIG. 3.

Expression of the nar operon in T. thermophilus HB27Camr::nar. (A) Coomassie blue-stained SDS-PAGE sample showing proteins from the particulate fractions of T. thermophilus HB8 (lanes 2, 3, and 4), T. thermophilus HB27Camr (lane 5), and T. thermophilus HB27Camr::nar (lanes 6 and 7). Cells were grown for 24 h under microaerophilic (lanes 2, 3, 5, and 6) or anaerobic (lanes 4 and 7) conditions with nitrate (lanes 3 to 7). The sample in lane 2 was grown without nitrate. Lane 1 represents markers whose sizes (in thousands) are labeled at the left. (B) Parallel Western blot with antiserum against NarG. A 140-kDa protein which corresponds to NarG is indicated by an arrow. Lanes are as in panel A.

Apart from demonstrating the transfer of the nar operon, these experiments also showed that its expression in T. thermophilus HB27Camr::nar was increased under anaerobiosis (Fig. 3, lane 7) compared to microaerophilic conditions (lane 6). In contrast, there were no differences in the nar induction level between microaerophilic and anaerobic conditions for T. thermophilus HB8 (Fig. 3, compare lanes 3 and 4).

Furthermore, despite the difference in expression observed (Fig. 3, lanes 6 and 7), the nitrate reductase activities were similar under microaerophilic and anaerobic conditions (560 and 510 U, respectively, per identical cell mass) in the exconjugant. Therefore, some of the NarG protein copies synthesized under anaerobiosis were inactive in the exconjugant. In fact, similar levels of NarG (Fig. 3B, compare lanes 4 and 7) yielded activities about threefold higher in T. thermophilus HB8.

Transfer of the nar operon occurs through an Hfr-like mechanism.

The results of the experiments shown in Fig. 2 and 3 suggested that the nar operon was transferred from the donor chromosome to that of the recipient to obtain the exconjugant T. thermophilus HB27Camr::nar. Since we could not detect the presence of DNA in the conjugation media (as would be expected from the use of a bacteriostatic antibiotic as a selective criterion), the mechanism most likely responsible for this transfer was conjugation. However, the natural competence capability described for Thermus spp. (12) still remained a less likely explanation.

To distinguish between these two possibilities, we used a classic interrupted-mating experiment (see Materials and Methods) to check whether there was a time dependence for the transfer of different genes. If the transfer were ordered, a conjugative mechanism could be inferred. In contrast, random transfer would indicate transformation as the most likely mechanism.

For these experiments and to make the selection easier (kanamycin resistance), we used as donors different T. thermophilus HB8::kat mutants, including the narGH::kat derivative (9, 21). As shown in Table 1, transfer of the slpM::kat mutation required less than 10 min, followed shortly afterward by the slrA::kat mutation. Nevertheless, about 50 min of mating was required for transfer when the narGH::kat mutant was used as a donor. Thus, we concluded that there was a time dependence for the transfer of each mutation assayed.

TABLE 1.

Time-dependent horizontal transfera

| Donor strain | Level of Kmr Camr colonies for a transfer time (min) of:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 100 | |

| slrA::kat | − | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| slpM::kat | + | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| narGH::kat | − | − | − | − | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

After the mating experiment (see Materials and Methods), we detected kanamycin- and chloramphenicol-resistant colonies at the following levels: −, none; +, less than 20; ++, 20 to 100; +++, more than 100.

To obtain further arguments supporting conjugation, these experiments were repeated in the presence of DNase I (100 μg/ml) with identical results. Controls for enzyme activity were carried out after the mating period to demonstrate that the remaining enzyme was still able to digest a 1-μg/μl solution of pUC119 in 10 min at 70°C.

We concluded that the transfer of the nar operon occurs through a conjugative mechanism which can also mobilize other chromosomal genes, as for the Hfr (high frequency of recombination) strains of E. coli.

Identification of a replicative origin (oriV) downstream of the nar operon.

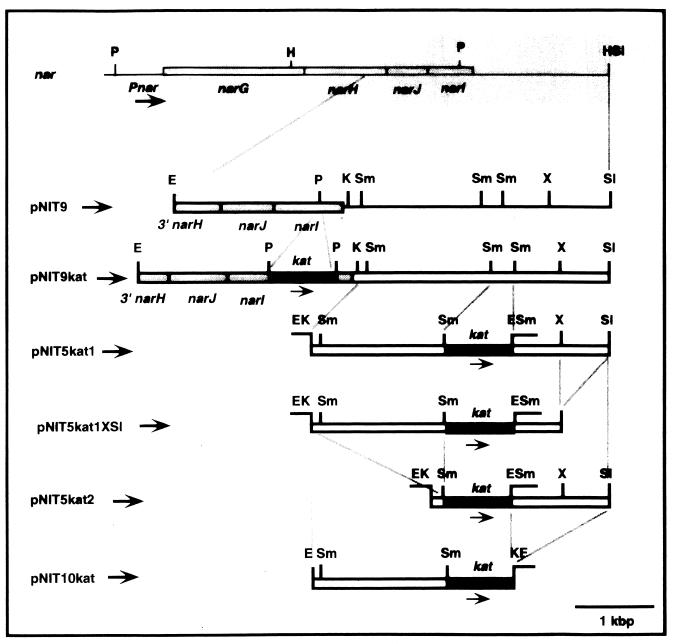

During the construction of narI::kat insertion mutants of T. thermophilus HB8 (unpublished data), we detected a high transformation efficiency with the circular form of plasmid pNIT9kat, which contains part of the nar operon and its downstream region (Fig. 4). In fact, the transformation efficiency observed (Table 2) was similar to that obtained with the bifunctional E. coli-Thermus shuttle vector pMK18 (6). Therefore, this result suggested the possible presence downstream of the nar operon of sequences encoding an origin for autonomous replication (oriV) in Thermus strains.

FIG. 4.

Identification of oriV downstream of the nar operon. Restriction maps of the nar region (shaded bars) and of the plasmids used to localize a replicative oriV. Genes narG, narH, narJ, and narI are labeled. The kat gene used for their selection in Thermus strains is shown by black bars. The approximate position of the nar promoter (Pnar) is shown. Restriction enzyme abbreviations: E, EcoRI; K, KpnI; P, PstI; S, SalI; Sm, SmaI; X, XhoI.

TABLE 2.

Identification of a replicative ori downstream of the nar operona

| Host | Level of Kmr colonies in the presence of plasmid:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pMK18 | pNIT9kat | pNIT5kat1 | pNIT5kat1XS | pNIT5kat2 | pNIT10kat | |

| HB8 | +++ | +++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++ | − |

| HB27Camr::nar | ++++ | +++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++ | − |

| HB27Camr | ++++ | − | − | − | − | − |

| BPL7 | ++ | − | − | − | − | − |

| E. coli TG1 | ++++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | |

Data represent the results of transformation of Thermus strains with plasmids purified from E. coli and the results of transformation of E. coli with the same plasmids isolated from Thermus strains. pMK18 was used as a control for transformation efficiency. Number of colonies: −, none; ++, 50 to 100; +++, 100 to 500; ++++, >500.

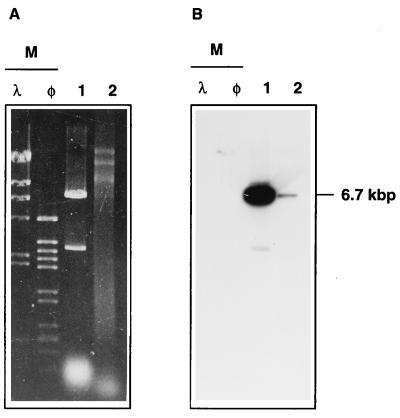

If this hypothesis were true, we should have been able to isolate plasmid pNIT9kat from Thermus transformant colonies. As shown in Fig. 5A, a DNA fragment of the size expected for pNIT9kat (6.7 kbp) was detected in the plasmid fraction of T. thermophilus HB8 (lane 2), and this fragment hybridized with a specific DNA probe (probe B) in a parallel Southern blot (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, when this plasmid fraction was used to transform competent cells of E. coli TG1, a high number of transformants (Table 2) contained pNIT9kat (confirmed by restriction analysis of plasmids from several colonies). These data revealed the ability of pNIT9kat to replicate autonomously in Thermus and, consequently, supported the existence of a replicative oriV downstream of the nar operon.

FIG. 5.

pNIT9kat replicates in Thermus strains. (A) Agarose gel electrophoresis of EcoRI-digested pNIT9kat purified from E. coli (lane 1) and EcoRI-digested plasmid fraction from T. thermophilus HB8 transformed with pNIT9kat (lane 2). (B) Parallel Southern blot labeled with probe B. Lanes are as in panel A. HindIII-digested DNAs from λ and φ29 phages were used as size markers (lane M).

When the exconjugant T. thermophilus HB27Camr::nar was used as the host in parallel experiments, identical results were obtained (Table 2). Furthermore, we could repeat several transformation cycles between Thermus and E. coli, always recovering plasmid pNIT9kat. Surprisingly, when T. thermophilus HB27Camr (the recipient strain in the conjugation experiments) or T. thermophilus BPL7 (a plasmid-free derivative of T. thermophilus HB8) was used, no transformant colonies appeared. This result suggests the requirement for a replication factor present only in nar-carrying strains (Table 2).

To locate more precisely oriV, we developed a group of derivative plasmids which contained different DNA fragments of the nar downstream region (Fig. 4) and used them to transform the four T. thermophilus strains. Except for pNIT10kat, all the derivatives showed results similar to those obtained with pNIT9kat, transforming T. thermophilus HB8 and T. thermophilus HB27Camr::nar but failing to transform T. thermophilus HB27Camr and T. thermophilus BPL7 (Table 2). As for pNIT9kat, we repeated with these plasmids the cycles of transformation between T. thermophilus HB27Camr::nar and E. coli and always recovered them from both organisms.

On the basis of these results, the replicative oriV is located within an 0.8-kbp SmaI/XhoI fragment downstream of the kat gene of pNIT5kat2 (Fig. 4). The sequence of this region (Fig. 6) revealed the existence of an open reading frame encoding the C-terminal part of a protein homologous (29% identity) to the C terminus of the nitrite extrusion protein NarK from E. coli. Immediately downstream of this open reading frame is a region which contains two inverted repeats, of 12 bp (ir1) and 10 bp (ir2), the latter of which is followed by a T-rich sequence. Two groups of A-rich sequences are also located around ir1. Direct repeats of different sizes (dr1) were also found both downstream of and overlapping the narK homolog.

DISCUSSION

Two important conclusions arise from the results presented in this article. First, we describe for the first time for strains of the genus Thermus a conjugative mechanism which is also able to mobilize chromosomal genes in a time-dependent manner. The second conclusion is more general, since we show that the ability to grow under anaerobic conditions may be encoded within a mobilizable element, thus making doubtful the relevance of the “aerobic” character of an organism in formal taxonomy (2).

The transfer of the nar operon from the facultative anaerobe T. thermophilus HB8 (donor) to the aerobe T. thermophilus HB27Camr (recipient) resulted in the isolation of a Camr facultative anaerobe. The nature of this organism as a derivative of the recipient was assessed in several ways. First, parallel controls in the absence of the recipient did not allow the isolation of any Camr mutant from the donor. Second, the total protein pattern of the organism selected after the conjugation was identical to that of the recipient and clearly different from that of the donor (compare lanes 5 and 6 with lanes 2 and 3 of Fig. 3). Finally, the profiles of NdeI digestion fragments of chromosomal DNA from the recipient and the exconjugant were identical except for the insertion of a 30-kbp DNA fragment.

A second point concerns the mechanism of transfer. That the transfer of the nar operon was due to conjugation and not to the natural competence described for Thermus was supported by different arguments. (i) The existence of external DNA during the mating period was unlikely due to the use of a bacteriostatic selective criterion (chloramphenicol) in the expression medium. In fact, we did not detect DNA in the medium after the conjugation. (ii) The transfer also took place in the presence of DNase I, an enzyme which was still active at 70°C even after the mating period. (iii) Different mating times were required to transfer different genes, a situation that would not occur if a transformation phenomenon were implicated.

The time-dependent transfer of chromosomal genes could be explained only on the basis of a mechanism similar to that of the Hfr strains of E. coli. In these strains, a plasmid (F) inserted into the chromosome provides the genes (tra) and an origin (oriT) required to drive the transfer of a single-strand copy of the whole chromosome to a recipient cell (16). As oriT is located within the plasmid sequence, plasmid-encoded genes located upstream of oriT are the last to be transferred, requiring about 100 min of mating in the E. coli system. Keeping in mind that the circular chromosome of T. thermophilus HB8 is about 1.740 kbp long (1) and assuming a rate of transfer similar to that in E. coli (chromosome size about 4.200 kbp), the 45 to 50 min of mating required to transfer the narGH::kat mutation could be expected if oriT were located immediately downstream of the nar operon. Unfortunately, the limited repertoire of gene markers makes impossible at the present time a detailed genetic analysis to check the putative association between the nar operon and oriT.

Additional evidence which supported the association between the nar operon and a conjugative plasmid was the fortuitous identification of a replicative oriV downstream of the nar operon (Fig. 4) which was functional in T. thermophilus HB8 and in T. thermophilus HB27Camr::nar but not in T. thermophilus HB27Camr or T. thermophilus BPL7 (Table 2). This fact suggests the existence of a gene carried by the transferred fragment, whose expression is required for the replication of this oriV. It is possible that the role of this factor is the identification of specific sequences at oriV, allowing the melting of DNA and the subsequent recruiting of a replication complex, as is the situation with the Rep protein(s) from many other plasmids (13).

The sequence of the region containing oriV revealed the presence of inverted and direct repeats downstream of a sequence which encodes the C-terminal part of a protein homologous to the nitrite extrusion protein NarK (Fig. 6). Although the presence of downstream T-rich sequences suggests a role for ir2 as a Rho-independent transcription terminator, the other repeats found may be related to the binding of the putative Rep factor mentioned above. Nevertheless, their role in replication and/or transcription is not known at present, and further deletion analysis is required to determine their role.

The above results support the existence of a conjugative plasmid which has been integrated into the chromosome of T. thermophilus HB8. Two plasmids, pTT8 and pVV8, have been described for T. thermophilus HB8 (26). Of these, only pVV8 is a likely candidate to be conjugative because of its larger size (26), its ability to confer an aggregation phenotype, and its ability to integrate into the chromosome through homologous regions (18). However, Southern blot assays revealed that neither pVV8 nor pTT8 hybridized with a nar probe (data not shown). Consequently, the oriV that we identified downstream of the nar operon belongs to a different plasmid. In this sense, its absence from T. thermophilus BPL7, a derivative of HB8, means that the nar-carrying plasmid was lost during the complex procedure followed for its selection, which included long-term growth under 100% oxygen, nitrosoguanidine mutagenesis, and ampicillin enrichment (18). Such a complex selection could have induced excision from the chromosome and the loss of the nar-carrying integrated plasmid to yield T. thermophilus BPL7.

After its transfer to the recipient, the expression of the nar operon in the exconjugant T. thermophilus HB27Camr::nar was still regulated by nitrate and oxygen. Whether this result was due to the simultaneous transfer of both the oxygen and the nitrate sensors or to their previous presence in the recipient cannot be answered at present. However, the inability of the recipient to use nitrate (21) makes the last possibility most unlikely, at least for the nitrate sensor system.

It is noteworthy that nar expression was even more gradual in the exconjugant than in T. thermophilus HB8; although full induction in HB8 was reached under microaerophilic conditions, completely anoxic conditions were required for full expression in the exconjugant. Furthermore, in spite of the expression of similar amounts of NarG protein (Fig. 3, lanes 4 and 7, for the HB8 and HB27Camr::nar strains, respectively), the enzymatic activity in the exconjugant strain was three times lower than that in strain HB8, suggesting that part of the enzyme synthesized was inactive. Accordingly, the exconjugant strain yielded less growth under anaerobic conditions than did the parental donor strain (Fig. 2A).

All of these data support the fact that the ability of T. thermophilus HB8 to respire nitrate is encoded in a genetic element which can be transferred to aerobic strains of the same genus, changing an obligate character to facultative. In fact, the unexpected presence of nar operons in certain strains of supposedly obligate aerobes such as Pseudomonas fluorescens (20) and Bacillus subtilis (10) could be due to a process of horizontal transfer similar to that described here. If this were the case, the requirement for oxygen, commonly used in formal taxonomy as one of the main characteristics for the classification of microorganisms, could be viewed as meaningless.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The technical assistance of J. de la Rosa is greatly appreciated.

This work was supported by project BIO97-0665 from the Comisión Interministerial de Ciencia y Tecnología (C.I.C.Y.T.) and by an institutional grant from Fundación Ramón Areces. S. Ramírez-Arcos holds a fellowship from Instituto de Cooperación Iberoamericana (I.C.I.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Borges K M, Berquist P L. Genomic restriction map of the extremely thermophilic bacterium Thermus thermophilus HB8. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:103–110. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.1.103-110.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brock T D. Genus Thermus Brock and Freeze 1969, 295AL. In: Krieg N R, Holt J G, editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 1. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1984. p. 333. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burggraf S, Olsen G J, Stetter K O, Woese C R. A phylogenetic analysis of Aquifex pyrophilus. Arch Microbiol. 1992;15:352–356. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(11)80207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu G, Vollrath D, Davis R W. Separation of large DNA molecules by contour-clamped homogeneous electric fields. Science. 1984;234:1582–1585. doi: 10.1126/science.3538420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dagert M, Ehrlich S. Prolonged incubation in calcium chloride improves the competence of Escherichia coli cells. Gene. 1979;6:23–28. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(79)90082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeGrado M. Caracterización de orígenes de replicación autónoma del género Thermus. Ph.D. thesis. Madrid, Spain: Universidad Autónoma de Madrid; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devereaux J, Haeverli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernández-Herrero L A, Olabarría G, Castón J R, Lasa I, Berenguer J. Horizontal transfer of S-layer genes within Thermus thermophilus. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5460–5466. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.19.5460-5466.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernández-Herrero L A, Olabarría G, Berenguer J. Surface proteins and a novel transcription factor regulate the expression of the S-layer gene in Thermus thermophilus HB8. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:61–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3191683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffmann T, Troup B, Szabo A, Hungerer C, Jahn D. The anaerobic life of Bacillus subtilis: cloning of the genes encoding the respiratory nitrate reductase system. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;131:219–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huber R, Langworthy R A, Köning H, Thomm M, Woese C R, Sleyter U B, Stetter K O. Thermotoga maritima sp. nov. represents a new genus of unique extremely thermophilic eubacterium growing up to 90°C. Arch Microbiol. 1986;144:324–333. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koyama Y, Hoshino T, Tomizuka N, Furukawa K. Genetic transformation of the extreme thermophile Thermus thermophilus and of other Thermus spp. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:338–340. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.1.338-340.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kües U, Stahl U. Replication of plasmids in gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:491–516. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.4.491-516.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laemmli U, Favre M. Maturation of the head of bacteriophage T4. I. DNA packaging events. J Mol Biol. 1973;80:575–599. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lasa I, Castón J R, Fernandez-Herrero L A, Pedro M A, Berenguer J. Insertional mutagenesis in the extreme thermophilic eubacteria Thermus thermophilus. Mol Microbiol. 1992;11:1555–1564. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Low K B. Hfr strains of Escherichia coli K-12. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 2402–2405. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marín I, Amils R, Abad J P. Linear extrachromosomal DNA of Thiobacillus cuprinus DSM 5495 in relation to its chemolithotrophic growth. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;134:75–78. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mather M, Fee J. Plasmid-associated aggregation in Thermus thermophilus HB8. Plasmid. 1990;24:45–56. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(90)90024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller J H. A short course in bacterial genetics: a laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Philippot L, Clays-Josserand A, Lensi R, Trinsoutreau I, Normand P, Potier P. Purification of the dissimilative nitrate reductase of Pseudomonas fluorescens and the cloning and sequencing of its corresponding genes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1350:272–276. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(97)00007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramírez-Arcos S, Fernández-Herrero L A, Berenguer J. A thermophilic nitrate reductase is responsible for the strain specific anaerobic growth of Thermus thermophilus HB8. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1396:215–227. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(97)00183-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith C L, Kolco S R, Cantor C R. Pulse field electrophoresis and the technology of large DNA molecules. In: Davies K, editor. Genome analysis: a practical approach. Oxford, England: IRL Press; 1988. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snell F D, Snell C T. Colorimetric methods of analysis. New York, N.Y: Van Nostrand; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vasquez C, Villanueva J, Vicuña R. Plasmid curing in Thermus thermophilus and Thermus flavus. FEBS Lett. 1983;158:339–342. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vieira J, Messing J. Production of single-stranded plasmid DNA. Methods Enzymol. 1987;153:3–11. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)53044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]