Abstract

The modified nucleoside 2-methylthio-N-6-isopentenyl adenosine (ms2i6A) is present in position 37 (adjacent to and 3′ of the anticodon) of tRNAs that read codons beginning with U except tRNA I,VSer in Escherichia coli. In Salmonella typhimurium, 2-methylthio-N-6-(cis-hydroxy)isopentenyl adenosine (ms2io6A; also referred to as 2-methylthio cis-ribozeatin) is found in tRNA, most likely in the species that have ms2i6A in E. coli. Mutants (miaE) of S. typhimurium in which ms2i6A hydroxylation is blocked are unable to grow aerobically on the dicarboxylic acids of the citric acid cycle. Such mutants have normal uptake of dicarboxylic acids and functional enzymes of the citric acid cycle and the aerobic respiratory chain. The ability of S. typhimurium to grow on succinate, fumarate, and malate is dependent on the state of modification in position 37 of those tRNAs normally having ms2io6A37 and is not due to a second cellular function of tRNA (ms2io6A37)hydroxylase, the miaE gene product. We suggest that S. typhimurium senses the hydroxylation status of the isopentenyl group of the tRNA and will grow on succinate, fumarate, or malate only if the isopentenyl group is hydroxylated.

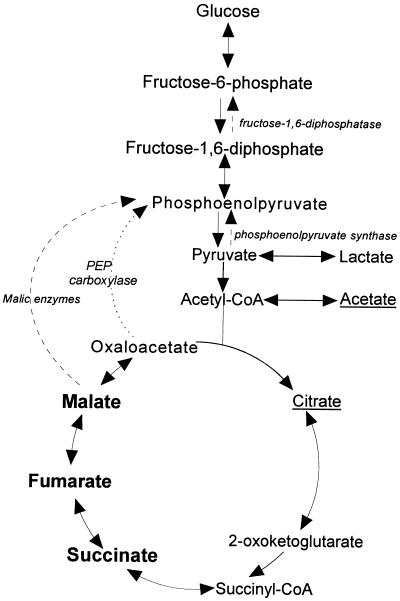

The central aerobic metabolic pathways of Salmonella typhimurium, the citric acid cycle (CAC), which oxidizes acetyl units to CO2, and the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas (EMP) pathway (glycolysis), which converts glucose-6-phosphate to pyruvate in conjunction with the pentose phosphate cycle, which oxidizes glucose-6-phosphate to CO2, are responsible for generating energy and for supplying precursors for biosynthesis (Fig. 1). The choice of different central pathways is regulated in response to several environmental factors. When S. typhimurium cells grow on glucose (Fig. 1), most energy is generated by the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway, whereas the CAC mainly provides precursor metabolites such as oxaloacetate, 2-oxoglutarate, and succinyl coenzyme A (succinyl-CoA). During growth on acetate (Fig. 1), the CAC generates both energy and precursor metabolites. Under certain growth conditions specific anaplerotic pathways are induced to direct the synthesis of necessary precursors. The genes for enzymes needed for growth on “poor” substrates such as CAC intermediates and acetate are regulated by the phosphotransferase:sugar transport system (PTS) through activation by the cyclic AMP-cyclic AMP receptor protein (cAMP-CRP) complex (reviewed in references 45, 49, and 50). Among the inducible anaplerotic enzymes are phosphoenolpyruvate synthase (PPS), phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK), and the enzymes of the glyoxylate shunt. These enzymes are also regulated by the product of the cra gene (previously designated fruR) of the so-called fructose regulon (50). Special regulatory molecules such as acetyl phosphate are also involved in regulation of central metabolic pathways when cells are grown on acetate (reviewed in references 24 and 34). Thus, the central aerobic metabolic pathways are affected by several regulons, which adjust their activity in a strict dependence on the environment of the cell.

FIG. 1.

Biosynthetic pathways with some of the anaplerotic pathways, including the enzymes in those steps, depicted as dashed arrows with the enzyme names in italics. Some of the arrows depicting the pathways represent more than one biosynthetic step. Underlined carbon sources are those on which miaE mutants have a longer lag time than wild-type S. typhimurium, while the miaE mutants do not grow at all on carbon sources marked in boldface.

tRNA from all organisms contains modified nucleosides, which are derivatives of the four canonical nucleosides. About 90 different modified nucleosides have been characterized so far (32). The synthesis of all these occurs after the primary transcript of the tRNA has been made (for reviews on modified nucleosides in tRNA, see references 3 and 4). Modification of tRNA is influenced by the cellular metabolism; e.g., starvation for methionine leads to methyl-deficient tRNA (33), and iron starvation in S. typhimurium results in lack of the 2-methylthio group in those tRNAs that normally have 2-methylthio-N-6-(cis-hydroxy)isopentenyl adenosine (ms2io6A) (8, 47, 60). The modification level of tRNA can also affect the expression of biosynthetic enzymes (reviewed in references 3, 4, and 40). The effects, so far found, of tRNA modification on metabolism have all concerned metabolic pathways such as amino acid biosynthesis and iron uptake. In this paper we show that the ms2io6A modification of tRNA influences central metabolic pathways.

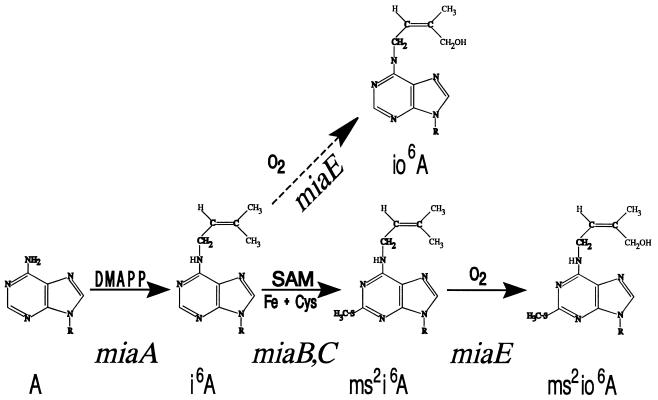

The synthesis of ms2io6A in S. typhimurium occurs as shown in Fig. 2. Judged from the chemical reactions involved, at least four enzyme activities are required for the synthesis of ms2io6A. The corresponding genetic loci are designated miaA, miaB, miaC, and miaE. The last step, hydroxylation, is dependent on the presence of molecular oxygen (O2). The tRNA (ms2io6A37)hydroxylase is present under anaerobic conditions, but the hydroxylation reaction does not occur under these conditions (6), and it has been suggested that ms2io6A may function as a regulator of aerobiosis.

FIG. 2.

Suggested biosynthetic pathway for ms2io6A in S. typhimurium. Known cofactors and substrates are indicated. The gene designations correspond either to identified genetic loci or postulated, but not yet identified, functions. DMAPP, dimethylallyl diphosphate (Δ2-isopentenylpyrophosphate); SAM, S-adenosyl methionine.

To further study the synthesis and function of the hydroxyl group of ms2io6A, we have previously isolated miaE::MudJ mutants of S. typhimurium LT2, which are unable to hydroxylate 2-methylthio-N-6-isopentenyl adenosine (ms2i6A). Such mutants can not grow on the CAC intermediates succinate, fumarate, or malate (41). Here, we show that the ability of S. typhimurium to grow on these dicarboxylic acids is strictly correlated with the presence of the hydroxyl group on the isopentenyl moiety of ms2io6A in position 37 (ms2io6A37).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

Strains used are listed in Table 1. Cultures were grown either in Luria broth (LB) according to the work of Bertani (2) or in Difco nutrient broth (0.8%; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) NaCl, adenine, tryptophan, tyrosine, phenylalanine, p-hydroxybenzoate, dihydroxybenzoate, and p-aminobenzoate (concentrations as stated in the work of Davis et al. [13]). As rich solid medium, TYS-agar (10 g of Trypticase Peptone, 5 g of yeast extract, 5 g of NaCl, and 15 g of agar per liter) was used. As defined liquid medium, morpholine propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) medium (37) supplemented with 0.2% of the relevant carbon source was used. Solid minimal medium was medium E (57) with no citrate added (NCE plates), supplemented with agar (1.5%) and 0.2 to 0.4% (wt/vol) of the relevant carbon source. Antibiotics were used in concentrations of 50 μg/ml for both kanamycin and carbenicillin. Anaerobic growth on agar plates was achieved by incubation in a Generbox (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France).

TABLE 1.

Strains of S. typhimurium

| Strain | Genotype | Construction | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| LT2 | Wild type | J. Roth, University of Utah | |

| GT523 | miaA1 | 15 | |

| GT2176 | miaB2508::Tn10dCm phs | 16 | |

| GT2734 | miaB2508::Tn10dCm | B. Esberg, Umeå, Sweden | |

| GT2944 | miaE2506::MudJ | Original isolate | 41 |

| GT2947 | miaE2507::MudJ | Original isolate | 41 |

| GT3034 | miaE2506::MudP | Replacement of MudJ of GT2944 with MudP | This work |

| GT3035 | miaE2507::MudP | Replacement of MudJ of GT2947 with MudP | This work |

| GT3098 | miaE2506::MudJ ses-1 | Transduction using GT2944 as the donor and LT2 as the recipient; spontaneous suppressor mutation | 41 |

| GT3099 | miaE2507::MudJ | Transduction using GT2947 as the donor and LT2 as the recipient | 41 |

| GT3283 | miaE2506::MudP pps-1::MudJ | Transduction using LJ2490 as the donor and GT3034 as the recipient | This work |

| GT3284 | miaE2507::MudP pps-1::MudJ | Transduction using LJ2490 as the donor and GT3035 as the recipient | This work |

| GT3285 | miaE2507::MudJ crr-307::Tn10 | Transduction using PP994 as the donor and GT3099 as the recipient | This work |

| GT3286 | miaE2507::MudJ ptsI421::Tn10 | Transduction using PP1228 as the donor and GT3099 as the recipient | This work |

| GT3287 | pps-1::MudJ | Transduction using LJ2490 as the donor and LT2 as the recipient | This work |

| GT3403 | miaE2507::MudJ crp*-661 zhe-3729::Tn10dCm | Transduction using TT17456 as the donor and GT3099 as the recipient | This work |

| GT3405 | cya-961 | Transduction using TT17457 as the donor and LT2 as the recipient | This work |

| GT3420 | miaE2507::MudJ miaA1 | Transduction using GT3099 as the donor and GT523 as the recipient | This work |

| GT3638 | miaB2508::Tn10dCm miaE2507::MudJ | Transduction using GT2176 as the donor and GT3099 as the recipient | This work |

| GT3640 | miaA1 miaB2508::Tn10dCm miaE2507::MudJ | Transduction using GT2176 as the donor and GT3420 as the recipient | This work |

| TT17456 | metE205 ara-9 cya-961::Tn10 zhe-3729::Tn10dCm crp*-661 | J. Roth | |

| TT17457 | metE205 ara-9 cya-961::Tn10 zhe-3729::Tn10dCm crp*-662 | J. Roth | |

| LJ2443 | fruR51::Tn10 | 11 | |

| LJ2490 | pps-1::MudJ | 11 | |

| PP994 | crr-307::Tn10 | 52 | |

| PP1139 | ptsG4152::Tn10 | 44 | |

| PP1228 | ptsI421::Tn10 | P. W. Postma, Amsterdam, The Netherlands |

HPLC analysis of tRNA nucleosides.

tRNA was prepared as described by Buck et al. (7). RNA samples were digested to nucleosides by the method of Gehrke et al. (20) by using nuclease P1 (Boehringer Mannheim) and bacterial alkaline phosphatase (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). After centrifugation, appropriate amounts (usually 100 μg for stable RNA and 50 μg for tRNA preparations) were applied on a Supelcosil LC-18S column on a Waters high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system. The gradient profile developed by Gehrke and Kuo was used (19).

HPLC analysis of ubiquinone.

Ubiquinone was extracted from cells grown to mid-logarithmic phase according to the method of DiSpirito et al. (14) with the modification suggested for Escherichia coli. Before the extraction procedure, the wet weight was determined and ubiquinone-10 (Sigma) was added as an internal standard for the efficiency of extraction. The ubiquinone content was analyzed by HPLC as described by Sherman et al. (54). The number of isoprene units of the S. typhimurium ubiquinone was determined by comparison to known markers ranging from ubiquinone-7 to ubiquinone-10 (Sigma).

Uptake of [14C]malate.

Cells were grown to a density of 2 × 108 in MOPS-lactate medium at 37°C, harvested, washed, and resuspended in MOPS buffer without a carbon source and containing 100 μg of chloramphenicol/ml. To 6 × 108 cells, 44.4 nmol of nonradioactive malate and 1.26 nmol of [14C]malate (48 μCi/μmol) were added, bringing the final malate concentration to 7.6 μM. Samples were taken at 0, 5, 10, and 15 min after the addition of [14C]malate and were immediately filtrated. The filters were washed twice with 10 ml of MOPS medium without a carbon source and containing chloramphenicol; then they were dried, and the radioactivity was determined in an LKB Wallac 1214 Rack- Beta Excel scintillation counter. For measurement of malate uptake in the presence of competitive inhibitors, either succinate or citrate was added to the cell suspension to achieve a concentration of 0.8 mM before addition of the labeling mix.

Preparation of extracts for enzyme assays.

For extracts of soluble proteins, cells were grown in 200 ml of LB medium and harvested in late-logarithmic phase. The cells were washed in MOPS-HCl (pH 7.4), pelleted, resuspended in 2 ml of MOPS-HCl (pH 7.4), and lysed by sonication (6 times, 20 s each time, on a Vibra Cell [Sonic and Materials, Inc., Danbury, Conn.] at a setting of 2.5). The sonicated extract was centrifuged in a Beckman SW50:1 rotor at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C. The upper two-thirds of the supernatant was collected and used for assays of soluble enzymes. Membrane preparations for assays of succinate dehydrogenase, succinate oxidase, glycerol-3-phosphate oxidase, and NADH oxidase activities were made from bacteria grown in LB plus 0.2% (wt/vol) glycerol to a density of 4 × 108 cells per ml. The membranes were prepared according to the method of Fridén et al. (18). Protein concentration determinations were made with the BCA (bicinchoninic acid) Protein Assay Reagent kit (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) as recommended by the manufacturer.

Enzyme assays.

All enzymes were assayed at 30°C. 2-Oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex activity was measured according to the method of Carlsson and Hederstedt (10). Succinyl-CoA synthetase was assayed by the method of Bridger et al. (5). Succinate dehydrogenase was assayed with artificial electron acceptors according to the method of Hägerhäll et al. (23). The fumarase assay was performed by the method of Racker (46), and malate dehydrogenase was assayed according to the work of Ochoa (38). Succinate and glycerol-3-phosphate oxidase activities were measured as oxygen consumption by using a Clark oxygen electrode as described elsewhere (28). The assay buffer was 20 mM MOPS (pH 7.4) plus 10 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.4). The oxygen concentration of the buffer at 30°C was taken to be 0.237 μmol/ml (28). Substrates were added to a final concentration of 10 mM. The enzymatic origin of the oxidase activities was confirmed by inhibition with 1 mM KCN. β-Galactosidase activity was determined according to the method of Miller (35), except that cells were lysed by the addition of 20 μl of chloroform and 50 μl of 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate per 500-μl sample.

RESULTS

Growth characterization of the miaE::MudJ mutants.

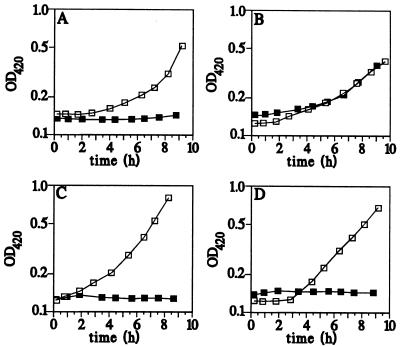

The miaE::MudJ mutants were tested for aerobic growth on various carbon sources on minimal-medium plates (Table 2). The mutants appeared to grow slower than the wild type, LT2, on citrate and acetate, and they did not grow at all on the CAC intermediates malate, fumarate, and succinate (41). However, no difference was observed for growth on glucose, glycerol, or lactate. Determination of the kinetics of growth of cells shifted into a medium containing a particular CAC intermediate gave clearer insight into the growth behavior of the miaE::MudJ strains. Figure 3 shows the results of shifts from MOPS-glucose medium to MOPS-acetate, -citrate, -malate, and -succinate media. Wild-type cells resumed growth after a short lag period. In contrast, mutant cells immediately stopped growing when they were shifted to a medium containing either malate or succinate and did not resume growth at all. When shifted to citrate or acetate minimal medium, the miaE mutant resumed growth after a longer lag period compared to wild-type cells but then grew at the same growth rate as the wild type at steady state (Fig. 3; Table 3). If glucose was added to the mutant cells 4 h after they were shifted to MOPS-malate or MOPS-succinate medium, the cells immediately resumed growth at a rate typical for growth in MOPS-glucose medium (data not shown). We used the amino acid and base pool plates of Davis et al. (13) and aspartic acid and glutamic acid together to see if the inability of the miaE mutant to grow on succinate was due to starvation for any amino acid. The growth deficiency of the miaE mutant could not be relieved by the addition of any amino acids (data not shown). Thus, not only is the miaE::MudJ mutant unable to grow on some CAC intermediates, but upon a shift from glucose to any of these compounds, growth stops immediately and is never resumed.

TABLE 2.

Growth of wild-type and mutant S. typhimurium on various carbon sourcesa

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Growthb on:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malate, fumarate, succinate | Malate + cAMPc | Lactate | Citrate | Acetate | ||

| LT2 | Wild type | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| GT3098 | miaE2506::MudJ ses-1 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| GT3099 | miaE2507::MudJ | − | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| PP1228 | ptsI::Tn10 | − | ++ | ++ | − | − |

| GT3286 | ptsI::Tn10 miaE2507::MudJ | − | − | ++ | − | − |

| PP994 | crr::Tn10 | − | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| GT3285 | crr::Tn10 miaE2507::MudJ | − | + | − | − | − |

| GT3403 | miaE2507::MudJ crp* zhe-::Tn10dCm | − | + | + | (−) | − |

| GT3405 | cya-961::Tn10 | − | ++ | − | − | − |

| LJ2443 | cra::Tn10 | − | (−) | − | − | − |

Results from replica plating experiment.

++, wild-type growth, strong growth overnight; +, weak growth overnight; (−), weak growth after 36 h; −, no growth.

The cAMP concentration was 10 mM.

FIG. 3.

Growth of S. typhimurium LT2 (□) and the miaE::MudJ mutant GT3099 (▪). At time zero, exponentially growing cells were shifted from MOPS-glucose to MOPS-citrate (A), MOPS-acetate (B), MOPS-malate (C), or MOPS-succinate (D).

TABLE 3.

Growth rates of LT2 (wild type) and GT3099 (miaE2507::MudJ)

| Medium | Growth rate (k)a of:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| LT2 | GT3099 | |

| Rich MOPS | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| MOPS-glucose | 0.83 | 0.83 |

| MOPS-glycerol | 0.73 | 0.72 |

| MOPS-citrate | 0.41 | 0.39 |

| MOPS-acetate | 0.35 | 0.35 |

| MOPS-succinate | 0.77 | NG |

k = ln2/generation time (in hours). NG, no growth.

The hydroxyl group of ms2io6A is synthesized only under aerobic conditions. Therefore, it was of interest to see if the miaE::MudJ mutants demonstrated impaired growth on CAC compounds under anaerobic conditions also. This was tested by incubating wild-type and mutant cells on NCE-malate and NCE-fumarate agar plates in an anaerobiosis chamber under an H2–CO2–N2 atmosphere. The miaE::MudJ mutants grew as well as wild-type LT2 cells under these conditions (data not shown).

The growth phenotype of miaE::MudJ mutants can be complemented by the wild-type miaE gene.

We have previously demonstrated that the growth phenotype is 100% linked to the miaE::MudJ insertion (41), which shows that this phenotype is not caused by a nearby mutation. However, it was important to establish that the growth defect is due to a defective miaE gene and not to some polar effects induced by the MudJ insertion. The expression of the downstream open reading frame 17.8 (ORF17.8) gene may be altered by the MudJ insertion if a strong promoter is created at the insertion point, although ORF17.8 is transcribed in the opposite direction from the miaE operon. Also, a gene product encoded by the short intercistronic region between the miaE gene and ORF17.8 could cause the growth deficiency. Therefore, several plasmids covering either the whole miaE operon or parts of it were used to complement the growth deficiency of the miaE mutant. Only plasmids carrying the entire miaE gene could restore growth on malate, fumarate, and succinate (data not shown). Plasmid pUST120, which carries the miaE gene, has an inactive ORF15.6 gene, and includes only 43 nucleotides downstream of the miaE gene (41), complemented the growth deficiency. These results show that the observed growth deficiency on CAC intermediates is caused by the inactivated miaE gene.

The inability of miaE strains to grow on succinate, malate, and fumarate is correlated with the presence of the cis-hydroxypentenyl modification in position 37 of the tRNA.

The growth deficiency of the miaE::MudJ mutant may be independent of the deficiency in ms2io6A modification. Another tRNA modification enzyme, the trmA gene product (42), has been shown to have two functions in E. coli, and this could also be the case for the MiaE enzyme. Therefore, we constructed strains carrying both the miaE::MudJ insertion mutation and either, or both, of the miaA and miaB mutations, which affect earlier steps in the ms2io6A synthetic pathway. If the miaE mutation causes the growth deficiency on CAC intermediates through a second function rather than through the hydroxylation deficiency of the tRNA, we would expect that the miaE mutants would retain their growth phenotype in the presence of the miaA or miaB mutation. If, however, the growth deficiency is caused by the lack of the hydroxyl group of ms2io6A, we would expect the miaA and the miaB mutations to be epistatic to the phenotype of the miaE mutant, since miaA and miaB single mutants can grow well on malate. The strains were tested for growth on malate, and the modification states of their tRNAs were confirmed by HPLC analysis. Note that the miaB mutant has a small amount of io6A, since apparently the MiaE hydroxylase is able, albeit poorly, to use as a substrate a tRNA lacking the ms2 group, provided that the i6 group is present (Table 4). As can be seen in Table 4, only miaA is epistatic to miaE. The miaA mutation suppresses the growth deficiency of the miaE mutant, whereas the miaB mutation does not. Thus, when the A in position 37 is lacking the isopentenyl side chain (as in the miaA mutant), the miaE gene product is not necessary for growth on succinate, fumarate, and malate, but when the isopentenyl side chain is present (as in wild-type cells and in the miaB mutant), growth occurs only if this side chain is hydroxylated. Since the miaA miaE double mutant grows on malate (Table 4), the MiaE enzyme does not appear to have an alternative function (besides modifying tRNA) the lack of which causes the inability of the miaE mutant to grow on malate. Thus, it seems as if S. typhimurium in some way senses the hydroxylation status of the isopentenyl side chain of the nucleoside in position 37 of tRNA.

TABLE 4.

Correlation between modification status and growth on malate

| Strain | Modification ability | Growth on malate |

|---|---|---|

| LT2 (wild type) | ms2io6A | + |

| GT523 miaA | A | + |

| GT2734 miaB | i6A (85%), io6A (15%) | + |

| GT3099 miaE | ms2i6A | − |

| GT3420 miaA miaE | A | + |

| GT3638 miaB miaE | i6A | − |

| GT3640 miaA miaB miaE | A | + |

Dicarboxylic acid uptake is normal in the mutant.

It was possible that the inability of the miaE mutants to grow on succinate, fumarate, and malate was due to a deficient dicarboxylic acid transport system (dct) (39). We measured [14C]malate uptake in cells grown in MOPS-lactate but found no difference between the wild type, LT2, and the miaE mutant GT3099 (data not shown). As expected, the uptake of malate was competitively inhibited by the addition of succinate or fumarate but not by the addition of citrate, which is taken up by the tricarboxylic acid transport system (27). Also, the miaE mutant is able to grow on malate in the presence of small amounts of lactate. We conclude that the inability of the miaE mutants to grow on dicarboxylic acids is not due to a deficient uptake of these carbon sources.

Activity of CAC enzymes.

The inability of the miaE mutants to grow on malate, fumarate, and succinate might be due to lack of, or reduced levels of, enzymes metabolizing dicarboxylic acids. We measured the activities of the CAC enzymes malate dehydrogenase, fumarase, succinate dehydrogenase, succinate thiokinase, and the 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex in cells grown in LB. Extracts from wild-type and mutant cells showed no significant difference (data not shown).

Activity of the respiratory chain.

A characteristic of E. coli mutants defective in the synthesis of ubiquinone is their ability to grow on glucose but not on succinate or malate (21). Thus, the phenotype of ubi mutants is reminiscent of that of miaE mutants. Therefore, we analyzed S. typhimurium wild-type and miaE::MudJ mutant cells for ubiquinone. Both strains contained ubiquinone-8, in accordance with what has been found earlier for S. typhimurium (12). The amount of ubiquinone in the cells (wet weight) was the same for the wild type and the mutant (data not shown). To exclude a malfunction of the respiratory chain in the miaE mutant, succinate oxidase and glycerol-3-phosphate oxidase activities of isolated membranes from cells grown in LB supplemented with 0.2% glycerol were measured. No differences in activity between wild-type and miaE::MudJ mutant cells could be detected.

The miaE growth phenotype can be suppressed by the addition of cAMP.

The growth phenotype of miaE::MudJ mutants was compared to those of other mutants known to be affected in growth on CAC intermediates. Mutants (crr) defective in the IIAGlc protein of the PTS sugar transport system are unable to grow on malate, fumarate, and succinate. In these mutants adenylate cyclase cannot be activated, and the cAMP necessary to relieve catabolite repression of genes needed for gluconeogenesis cannot be synthesized (reviewed in references 43, 45, and 48). miaE::MudJ mutants, as well as crr mutants, can grow on malate, fumarate, and succinate in the presence of 10 mM cAMP (Table 2). However, much higher concentrations of cAMP are needed to supplement the growth of the miaE mutant (Table 5). The inability of mutants (ptsI) defective in enzyme I of the PTS system to grow on glycerol can be suppressed by a mutation in the crr gene (51); the miaE mutation, however, cannot suppress the ptsI phenotype (Table 2). Furthermore, the growth abilities of an miaE::MudJ crr::Tn10 double mutant are different from those of either of the single mutants (Table 2).

TABLE 5.

cAMP dependence of crr, cya, and miaE mutants

| Medium | Growtha of strain:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| PP994 (crr::Tn10) | GT3405 (cya::Tn10) | GT3099 (miaE2507::MudJ) | |

| Malate | 24 | 12 | 12 |

| Fumarate | 22 | 9 | 9 |

| Succinate | 24 | 12 | 13 |

Values are diameters (in millimeters) of the zones of growth around 6-mm-diameter filter discs containing 2 μmol of cAMP.

Another gene essential for growth on succinate, fumarate, and malate is the cya gene, encoding adenylate cyclase. The cAMP concentration needed to support the growth of a cya mutant on malate was the same as that needed for the growth of the miaE mutant, but the cya mutant is not able to grow on a variety of carbon sources on which the miaE mutant can grow well (Table 2). Also, a crp* mutation, which allows CRP to activate transcription in the absence of cAMP, could not suppress the phenotype of the miaE mutant (Table 2). The large amount of cAMP needed to support the growth of the miaE mutant might be due to small amount of ribose contamination in the cAMP preparation. We tested this by growing the miaE mutant in a MOPS-succinate medium supplemented with small amounts of ribose or other compounds directly or indirectly provided by gluconeogenetic pathways (Table 6). The miaE mutant was able to grow with these supplementations, as well as with small amounts of lactate (data not shown), which can support the growth of the miaE mutant on malate. The likely explanation for this result is that gluconeogenesis is blocked in the miaE mutant. Although the mutant can cover most of its need for building blocks and energy by using malate, it apparently needs some compound(s) upstream of phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) for carbohydrate synthesis and for providing acetyl units for the CAC.

TABLE 6.

Supplementation of growth on MOPS-succinatea

| Carbon source | Growth of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| LT2 (wild type) | GT3098 (miaE::MudJ ses-1) | GT3099 (miaE::MudJ) | |

| Succinate | + | + | − |

| Ribose | − | − | − |

| Succinate + ribose | + | + | + |

| PEP | − | − | − |

| Succinate + PEP | + | + | + |

| Acetate | − | − | − |

| Succinate + acetate | + | + | + |

| Pyruvate | − | − | − |

| Succinate + pyruvate | + | + | + |

| G-6-P | − | − | − |

| Succinate + G-6-P | + | + | + |

The experiments were performed in liquid MOPS medium supplemented with the carbon sources indicated. All carbon sources were added to 0.13 mM, except succinate, which was 0.4% when added. G-6-P, glucose-6-phosphate.

Isolation and genetic mapping of mutations causing suppression of miaE::MudJ.

Strains that were able to grow on succinate, although they still retained the miaE::MudJ insertion and were deficient in ms2io6A hydroxylation, could be isolated at a frequency of 10−6. We designate these suppressor mutations ses (for suppressors of miaE-mediated inability to grow on succinate). All ses mutations also allowed for growth of the miaE mutants on malate. Tn10dTc transposon (59) insertions cotransducible with ses-1 were isolated. Preliminary mapping using the MudP and MudQ bank (Mud-P22 recombinant phage inserted at specific positions in the S. typhimurium chromosome [61]) as described by Benson and Goldman (1) indicated that the ses-1 mutation is located between 38 and 42 min on the S. typhimurium chromosome (data not shown). None of the other suppressors were cotransducible with the transposons next to ses-1. Thus, mutations at more than one locus can suppress the inability of miaE::MudJ mutants to grow on malate and succinate.

DISCUSSION

S. typhimurium miaE-defective mutants cannot grow aerobically on succinate, fumarate, or malate (reference 41 and this work). This growth defect is correlated with the absence of the hydroxyl group of the isopentenyl moiety of those tRNAs that normally have ms2io6A37. In this work we have searched for an explanation to this unusual connection between central carbon metabolism and tRNA modification.

Mutants defective in the miaE gene were found to take up dicarboxylic acid from the growth medium, to contain functional CAC enzymes, and to respire like a wild-type strain. Growth on CAC intermediates is principally different from growth on glucose in that it requires gluconeogenesis. In cells grown in the presence of glucose, sufficient energy is obtained from the glycolysis pathway and the enzymes of the CAC are present in small amounts (Fig. 1). The finding that small amounts of compounds normally synthesized through gluconeogenesis, e.g., ribose, can support the growth of the miaE mutants indicates that gluconeogenesis is affected in these strains. Among the enzymes induced by growth on CAC intermediates are fructose-1,6-phosphatase, PPS, the malic enzymes (MAEs), and PEPCK (Fig. 1). Since either MAEs together with PPS or PEPCK can synthesize PEP from CAC intermediates, the defect in the miaE mutants must be in at least two enzymes, either in PEPCK and PPS or in PEPCK and MAEs. Since the miaE mutants grow well on lactate and pyruvate, the PPS appears functional. When E. coli cells grow aerobically on acetate, the flux from oxaloacetate (OAA) to PEP is about 3.6 mmol · g−1 · h−1 (24). In a cell growing on citrate, this flux is increased due to the increased growth rate and, more importantly, because the acetyl-CoA needed for fatty acid biosynthesis and other acetyl-CoA-requiring reactions must be generated from carbon coming through the CAC. During growth on succinate, fumarate, and malate, the strain on the enzymes catalyzing the flow from OAA to PEP is even higher, since the acetyl-CoA needed for biosynthesis in the first half of the CAC (to 2-oxoglutarate) is also synthesized through this pathway. The flux from OAA to PEP in cells growing on malate thus has to be severalfold higher than when the cells grow on acetate (calculated from reference 24). These differences in the requirements of gluconeogenesis during growth on acetate, citrate, or malate may explain the differences in phenotype seen for these carbon sources.

MiaE is most likely an enzyme that catalyzes the hydroxylation of the isopentenyl moiety of ms2i6A of tRNA (Fig. 2) (41). We found that if A37 is unmodified, as in an miaA-defective mutant, S. typhimurium can grow on malate independently of whether the miaE gene is functional or not. In contrast, MiaE is required for growth on malate if the isopentenyl part is present, in the form of i6A37 or ms2i6A37. Thus, it seems as if S. typhimurium has a mechanism to recognize the isopentenyl chain of i6A and sense whether it is hydroxylated. The presence of the hydroxyl group will then stimulate the activity or synthesis of some enzyme(s) needed for growth on succinate, fumarate, and malate. This suggestion is based on the assumption that the MiaA enzyme does not add an isopentenyl group to some other substrate in addition to tRNA. We find this unlikely, since the MiaA enzyme requires both the sequence A36-A37-A38 in the anticodon loop of the tRNA and a 5-bp anticodon stem for activity (22, 31, 36, 55). The structural requirements of the substrate for the MiaE enzyme are not known, but hydroxylation of i6A is more efficient when the ms2 group is present (16, 41).

An miaA null mutation suppresses the phenotype of an miaE mutant. We interpret this as a result of the absence of the signaling molecule, the isopentenyl side chain of ms2i6A. There is, however, a possibility that the suppression is caused by a derepression of some key enzyme, which in turn metabolically suppresses the growth defect induced by the miaE mutation. Tsui et al. (56) have shown that a strain containing the miaA::Ω insertion has an increased oxidation rate of some amino acids and CAC intermediates and that it has a changed utilization of some primary carbon sources. Jones et al. (26) have shown that a mutation in the miaA gene derepresses phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, which is encoded by the gnd gene and is part of the pentose phosphate cycle. This derepression is specific, since the miaA1 mutation does not derepress the synthesis of glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase, which is encoded by the zwf gene and is upstream of the gnd gene product in the synthesis of ribose phosphate. Although derepressed synthesis of an enzyme in a complex metabolic pathway does not necessarily result in an increased pool of a downstream metabolite, we tested whether the miaA1-induced suppression required an intact gnd gene product. We found that this is not the case; i.e., the miaA1-mediated suppression of the miaE-induced growth defect did not require a gnd+ allele (data not shown). Thus, although we cannot completely rule out a mechanism in which the miaA1 mutation changes a pool of any of the glycolytic intermediates, we have so far no indications that this is the case.

The most apparent way the cell may sense the presence of the hydroxyl group of ms2io6A37 would be through translation. However, we have not been able to demonstrate any defect in translation in an miaE mutant (40). Also, E. coli lacks the miaE gene; consequently, it lacks ms2io6A in its tRNA and has ms2i6A instead (9, 41). Still, E. coli grows well on CAC intermediates (E. coli cannot grow on citrate due to the absence of a functional uptake system [29, 30]). In this respect, i.e., in lacking the hydroxylation group and still being able to grow on succinate, E. coli resembles the Salmonella miaE mutant strain carrying extragenic suppressor mutations (see below). Thus, we do not believe that the cis-hydroxyl group of ms2io6A exerts its effect in translation. However, the possibility that ms2io6A is essential for proper function of a certain tRNA species at certain sites in the translation of gene products necessary for growth on succinate, fumarate, or malate cannot be ruled out.

Screenings for extragenic suppressors have shown that there are several cellular components that can be genetically altered to compensate for the absence of the miaE gene, i.e., to allow growth on dicarboxylic acids. The suppressor-containing strains retain the ms2i6A hydroxylation deficiency. Preliminary results suggest that one of the suppressor mutations is not in the gene for any gluconeogenetic enzyme, but in a gene that might encode an uncharacterized transcription factor (data not shown). One way this suppressor mutation might act is by causing derepression of the synthesis of a gluconeogenic enzyme or by increasing the availability of a cofactor required for the activity of a key enzyme.

If the cis-hydroxyl group of ms2io6A37 does not exert its effect through translation, then our finding that the presence of the hydroxyl group on the tRNA regulates the ability of S. typhimurium to grow on succinate, fumarate, and malate represents a completely new mode of metabolic regulation. Few examples are known where tRNA participates in metabolism in ways other than through translation. A tRNAGlu is required for δ-aminolevulinic acid synthesis in plants, algae, and many bacteria (25, 53, 58). Cross-linking by near-UV light of 4-thiouridine in position 8 (s4U8) and C13 in tRNA is believed to act as a photosensor that triggers a protective response in E. coli (17). Perhaps the hydroxylation of the i6A residue is required for some gluconeogenetic enzyme reactions or as part of a regulatory complex influencing gluconeogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Dan Anderson, Diana Downs, Pieter Postma, John Roth, and Milton Saier for providing us with strains. We thank Kristina Nilsson, Kerstin Jacobsson, and Anna Gunnarsson for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society (project 680 [to G.R.B.]) and the Swedish Natural Science Research Council (projects B-BU 2930 [to G.R.B.] and S-FO 1637 [to L.H.]).

REFERENCES

- 1.Benson N R, Goldman B S. Rapid mapping in Salmonella typhimurium with Mud-P22 prophages. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1673–1681. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.5.1673-1681.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertani G. Studies on lysogenesis. J Bacteriol. 1951;62:293–300. doi: 10.1128/jb.62.3.293-300.1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Björk G R. Genetic dissection of synthesis and function of modified nucleosides in bacterial transfer RNA. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1995;50:263–338. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60817-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Björk G R. Stable RNA modifications. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 861–886. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bridger W A, Ramalay R F, Boyer P D. Succinyl coenzyme A from Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 1969;13:70–75. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buck M, Ames B N. A modified nucleotide in tRNA as a possible regulator of aerobiosis: synthesis of cis-2-methyl-thioribosylzeatin in the tRNA of Salmonella. Cell. 1984;36:523–531. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buck M, Connick M, Ames B N. Complete analysis of tRNA-modified nucleosides by high-performance liquid chromatography: the 29 modified nucleosides of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli tRNA. Anal Biochem. 1983;129:1–13. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buck M, Griffiths E. Regulation of aromatic amino acid transport by tRNA: role of 2-methylthio-N6-(Δ2-isopentenyl)-adenosine. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:401–414. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.2.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buck M, McCloskey J A, Basile B, Ames B N. cis 2-Methylthio-ribosylzeatin (ms2io6A) is present in the transfer RNA of Salmonella typhimurium, but not Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:5649–5662. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.18.5649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlsson P, Hederstedt L. In vitro complementation of Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex mutants and genetic mapping of B. subtilis citK and citM mutations. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1986;37:373–378. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chin A M, Feldheim D A, Saier M H., Jr Altered transcriptional patterns affecting several metabolic pathways in strains of Salmonella typhimurium which overexpress the fructose regulon. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:2424–2434. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.5.2424-2434.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dabrikowska A K. Electron transport system of Salmonella typhimurium cells. Acta Biochim Pol. 1970;17:89–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis W, Botstein D, Roth J R. A manual for genetic engineering: advanced bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 14.DiSpirito A A, Loh W H T, Touvinen O H. A novel method for the isolation of bacterial quinones and application to appraise the ubiquinone composition of Thiobacillus ferroxidans. Arch Microbiol. 1983;135:77–80. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ericson J U, Björk G R. Pleiotropic effects induced by modification deficiency next to the anticodon of tRNA from Salmonella typhimurium LT2. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:1013–1021. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.3.1013-1021.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Esberg B, Björk G R. The methylthio group (ms2) of N6-(4-hydroxyisopentenyl)-2-methylthioadenosine (ms2io6A) present next to the anticodon contributes to the decoding efficiency of the tRNA. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1967–1975. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.1967-1975.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Favre A, Hajnsdorf E, Thiam K, Caldeira de Araujo A. Mutagenesis and growth delay induced in Escherichia coli by near-ultraviolet radiations. Biochimie. 1985;67:335–342. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(85)80076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fridén H, Cheesman M R, Hederstedt L, Andersson K K, Thomson A J. Low temperature EPR and MCD studies on cytochrome b-558 of the Bacillus subtilis succinate: quinone oxidoreductase indicate bis-histidine coordination of the heme iron. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1041:207–215. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(90)90067-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gehrke C W, Kuo K C. Chromatography and modification of nucleosides. Part A. Analytical methods for major and modified nucleosides. 1990. pp. A3–A71. . Journal of Chromatography Library no. 45A. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gehrke C W, Kuo K C, McCune R A, Gerhardt K O, Agris P F. Quantitative enzymatic hydrolysis of tRNAs: reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography of tRNA nucleosides. J Chromatogr. 1982;230:297–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibson F. Chemical and genetical studies in the biosynthesis of ubiquinone by Escherichia coli. Biochem Soc Trans. 1973;I:317–326. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grosjean H, Nicoghosian K, Haumont E, Söll D, Cedergren R. Nucleotide sequences of two serine tRNAs with a GGA anticodon: the structure-function relationships in the serine family of E. coli tRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:5697–5706. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.15.5697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hägerhäll C, Aasa R, von Wachenfeldt C, Hederstedt L. Two hemes in Bacillus subtilis succinate:menaquinone oxidoreductase (complex II) Biochemistry. 1992;31:7411–7421. doi: 10.1021/bi00147a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holms W H. Control of flux through the citric acid cycle and the glyoxylate bypass in Escherichia coli. Biochem Soc Symp. 1987;54:17–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang D D, Wang W Y, Gough S P, Kannangara C G. δ-Aminolevulinic acid-synthesizing enzymes need an RNA moiety for activity. Science. 1984;225:1482–1484. doi: 10.1126/science.6206568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones W R, Barcak G J, Wolf R E., Jr Altered growth-rate-dependent regulation of 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase level in hisT mutants of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1197–1205. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.3.1197-1205.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kay W W, Cameron M. Citrate transport in Salmonella typhimurium. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1978;190:270–280. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(78)90276-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kielley W W. Preparation and assay of phosphorylating submitochondrial particles: sonicated mitochondria. Methods Enzymol. 1963;6:272–277. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koser S A. Correlation of citrate utilization by members of the colon-aerogenes group with other differential characteristics and with habitat. J Bacteriol. 1924;9:59–77. doi: 10.1128/jb.9.1.59-77.1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lara F J S, Stokes J L. Oxidation of citrate by Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1952;63:415–420. doi: 10.1128/jb.63.3.415-420.1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leung H C, Chen Y, Winkler M E. Regulation of substrate recognition by the MiaA tRNA prenyltransferase modification enzyme of Escherichia coli K-12. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13073–13083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.13073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Limbach P A, Crain P F, McCloskey J A. Summary: the modified nucleosides of RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2183–2196. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.12.2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mandel L R, Borek E. Variability in the structure of ribonucleic acid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1961;4:14–18. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(61)90246-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCleary W R, Stock J B, Ninfa A J. Is acetyl phosphate a global signal in Escherichia coli? J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2793–2798. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.2793-2798.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Motorin Y, Bec G, Tewari R, Grosjean H. Transfer RNA recognition by the Escherichia coli Δ2-isopentenyl-pyrophosphate:tRNA delta2-isopentenyl transferase: dependence on the anticodon arm structure. RNA. 1997;3:721–733. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neidhardt F C, Bloch P L, Smith D F. Culture medium for enterobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1974;119:736–747. doi: 10.1128/jb.119.3.736-747.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ochoa S. Malic dehydrogenase from pig heart. Methods Enzymol. 1955;1:735–736. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parada J L, Ortega M V, Carrillo-Castaneda G. Biochemical and genetic characteristics of the C4-dicarboxylic acids transport system of Salmonella typhimurium. Arch Mikrobiol. 1973;94:65–76. doi: 10.1007/BF00414078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Persson B C. Modification of tRNA as a regulatory device. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:1011–1016. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Persson B C, Björk G R. Isolation of the gene (miaE) encoding the hydroxylase involved in the synthesis of 2-methylthio-cis-ribozeatin in tRNA of Salmonella typhimurium and characterization of mutants. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7776–7785. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.7776-7785.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Persson B C, Gustafsson C, Berg D E, Björk G R. The gene for a tRNA modifying enzyme, m5U54-methyltransferase, is essential for viability in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:3995–3998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.3995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peterkofsky A, Reizer A, Reizer J, Gollop N, Zhu P-P, Amin N. Bacterial adenylyl cyclase. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1993;44:32–65. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60216-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Postma P W. Defective enzyme II-BGlc of the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotranferase system leading to uncoupling of transport and phosphorylation in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1981;147:382–389. doi: 10.1128/jb.147.2.382-389.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Postma P W, Lengeler J W, Jacobsson G R. Phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase systems. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 1149–1174. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Racker E. Spectrophotometric measurements of the enzymatic formation of fumaric and cis-aconitic acids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1950;4:211–214. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(50)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosenberg A H, Gefter M L. An iron-dependent modification of several transfer RNA species in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1969;46:581–584. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90197-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saier M H., Jr Protein phosphorylation and allosteric control of inducer exclusion and catabolite repression by the bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:109–120. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.1.109-120.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saier M H., Jr A multiplicity of potential carbon catabolite repression mechanisms in prokaryotic and eukaryotic microorganisms. New Biol. 1991;3:1137–1147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saier M H., Jr Regulatory interactions involving the proteins of the phosphotransferase system in enteric bacteria. J Cell Biochem. 1993;51:62–68. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240510112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saier M H, Jr, Roseman S. Sugar transport. The crr mutation: its effect on repression of enzyme synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:6598–6605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scholte B J, Schuitema A R J, Postma P W. Characterization of factor IIIGlc in catabolite repression-resistant (crr) mutants of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1982;149:576–586. doi: 10.1128/jb.149.2.576-586.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schön A, Krupp G, Gough S, Berry-Lowe S, Kannangara C G, Söll D. The RNA required in the first step of chlorophyll biosynthesis is a chloroplast glutamate tRNA. Nature. 1986;322:281–284. doi: 10.1038/322281a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sherman M M, Petersen L A, Poulter C D. Isolation and characterization of isoprene mutants of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3619–3628. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.7.3619-3628.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tsang T H, Buck M, Ames B N. Sequence specificity of tRNA-modifying enzymes. An analysis of 258 tRNA sequences. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983;741:180–196. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(83)90058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tsui H C T, Leung H C E, Winkler M E. Characterization of broadly pleiotropic phenotypes caused by an hfq insertion mutation in Escherichia coli K-12. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:35–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vogel H J, Bonner D M. Acetylornithinase of Escherichia coli: partial purification and some properties. J Biol Chem. 1956;218:97–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang W W, Huang D D, Stachon D, Gough S P, Kannangara C G. Purification, characterization and fractionation of the δ-aminolevulinic acid synthesizing enzyme from light grown Chlamydomonas reinhardtii cells. Plant Physiol (Rockville) 1984;74:569–575. doi: 10.1104/pp.74.3.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Way J C, Davis M A, Morisato D, Roberts D E, Kleckner N. New Tn10 derivatives for transposon mutagenesis and for construction of lacZ operon fusions by transposition. Gene. 1984;32:369–379. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wettstein F O, Stent G S. Physiologically induced changes in the property of phenylalanine tRNA in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1968;38:25–40. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Youderian P, Sugiono P, Brewer K L, Higgins N P, Elliott T. Packaging specific segments of the Salmonella typhimurium chromosome with locked-in Mud-P22 prophages. Genetics. 1988;118:581–592. doi: 10.1093/genetics/118.4.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]