Abstract

Objective

To clarify both the histologic changes in primary viral pneumonia other than COVID-19 and whether patients with severe lung injury (SLI) on biopsy specimens progress to severe respiratory insufficiency.

Methods

Patients with primary viral pneumonia other than COVID-19, who underwent lung tissue biopsy, were retrospectively studied.

Patients

Forty-three patients (41 living patients and 2 autopsied cases) were included in the study.

Results

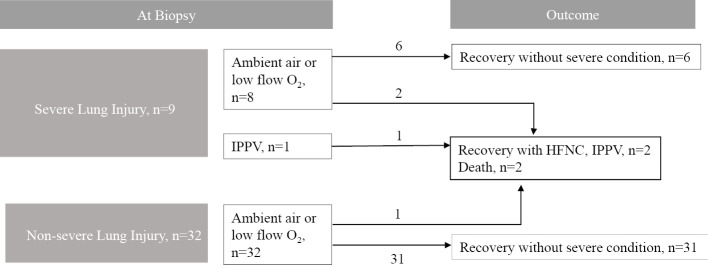

Nine patients had SLI, whereas most of patients who recovered from primary viral pneumonia showed a nonspecific epithelial injury pattern. One patient underwent a biopsy under mechanical ventilation. Two of 8 (25.0%) patients on ambient air or low-flow oxygen therapy progressed to a severe respiratory condition and then to death, while only 1 (3.1%) of 32 patients without SLI progressed to a severe respiratory condition and death (p=0.096). The proportion of patients who required O2 treatment for ≥2 weeks was higher in patients with SLI than in those without SLI (p=0.033). The 2 autopsy cases showed a typical pattern of diffuse alveolar damage, with both showing hyaline membranes. Non-specific histologic findings were present in 32 patients without SLI.

Conclusion

Some patients with SLI progressed to severe respiratory insufficiency, whereas those without SLI rarely progressed to severe respiratory insufficiency or death. The frequency of patients progressing to a severe respiratory condition or death did not differ significantly between those with and without SLI. The proportion of patients who required longer O2 treatment was higher in SLI group than in those without SLI.

Keywords: primary viral pneumonia, pathology, histology, lung injury, diffuse alveolar damage, outcome

Introduction

Findings associated with viral pneumonia in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) have been accumulating. Reports on the histology of viral pneumonia are based on autopsy cases of patients with COVID-19 or influenza; however, the histologic findings of viral pneumonia, samples of which should be obtained from living patients, especially viral pneumonia other than COVID-19 pneumonia, have not been fully reported (1-3). Furthermore, findings obtained from animal models are not always applicable to humans (4,5). Thus, the characteristics of histologic findings of viral pneumonias other than COVID-19 pneumonia and whether patients with severe histologic damage develop clinically severe symptoms should be clarified. We therefore conducted this retrospective study.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective study of patients with primary viral pneumonia who were admitted to Saitama Cardiovascular and Respiratory Center from January 2002 to November 2019. Among them, patients whose lung tissues were biopsied via bronchoscopy or thoracoscopy were included. We then reviewed their laboratory data, chest imaging, clinical courses, treatment, and outcome. Patients suffering from COVID-19 were excluded.

We diagnosed patients as having primary viral pneumonia when viruses were detected from nasopharyngeal swabs or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), significantly increased antibody titers were present in convalescent sera, and pathogens other than viruses were not found. The methods used to identify pathogens were as described elsewhere (6,7). Nasopharyngeal swab specimens, bronchial washing fluid, and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid were stored at -70°C and used for the detection of respiratory pathogens on a Rotor Gene Q instrument (Quiagen, Hilden, Germany) with single or multiplex, real-time PCR using an FTD Resp 21 Kit (Fast Track Diagnostics, Silema, Malta). This kit detects the following pathogens: influenza A and B virus, coronavirus (NL63, 229E, OC43, and HKU1); human parainfluenza virus; human metapneumovirus A/B, rhinovirus; respiratory syncytial virus A/B; adenovirus, enterovirus; human parechovirus; bocavirus; and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. The PCR results were considered to be positive with a threshold cycle value of <33, as indicated in the instruction manual. Paired sera included antibody titers of M. pneumoniae, Legionella spp., Chlamydia psittaci, C. pneumoniae, influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, human parainfluenza virus, and adenovirus. The results are expressed as the mean±standard deviation, median (range), and number (%). Disease onset was defined from anamnesis as day 0, the day on which initial symptoms developed. The disease course was divided into 3 phases: early phase (0-14 days), middle phase (15-28 days), and delayed phase (≥29 days). Severity on admission was defined based on an established guideline (8). Histology was evaluated by a pathologist (Y.S.) for 20 findings (capillary congestion, interstitial, and intra-alveolar edema, alveolar hemorrhage, hyaline membranes, dilated alveolar ducts plus collapsed alveoli, endothelial necrosis, increased megakaryocytes, alveolar granulocytes, desquamation of pneumocytes, platelet-fibrin thrombi, type 2 pneumocyte hyperplasia, squamous metaplasia with atypia, alveolar loose plugs of fibroblastic tissue, capillary proliferation, organized alveoli plus dilated alveolar ducts, interstitial infiltrate, alveolar inflammatory infiltrate [macrophages], alveolar multinucleated giant cells, microscopic honeycombing, and fibrin exudation) based on findings for each item as reported elsewhere (9).

In addition, severe lung injury (SLI) was defined when at least one of the following representative findings was found: prominent type 2 pneumocyte proliferation (atypia with nuclear enlargement, clumped nuclear chromatin, cellular pleomorphism), hyaline membranes, foci of acute inflammation and hemorrhage, excessive fibrin exudation filling alveolar spaces, and organization on the luminal surface of alveolar walls or organization that filled and obliterated whole lumens of alveoli (severe intraluminal organization) (10-12) was found (13,14).

The patients' respiratory condition was classified as breathing ambient air, requiring low-flow oxygen inhalation, high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC), invasive positive pressure ventilation (IPPV), extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and death. Severe respiratory conditions were defined as those that required HFNC, IPPV, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Saitama Cardiovascular and Respiratory Center (approval no.: 2019030).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented using descriptive statistics for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. Frequencies among groups were compared using Fisher's exact test. A random-intercept regression model adjusting for the histologic patterns from lung samples was used to examine the overall trend in the proportions of histologic findings among disease courses. Two-sided p values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant in all tests. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, USA).

Results

During the study period, 363 patients with viral pneumonia (virus-associated pneumonia) were admitted to our institution. Among them, 43 patients with primary viral pneumonia whose lung samples were biopsied were retrospectively analyzed.

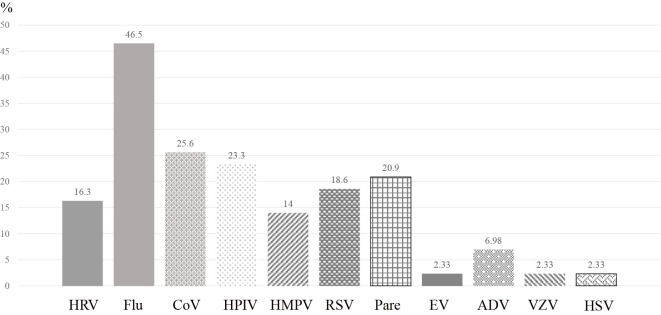

The mean patient age was 66.4±10.8 years, and approximately half of the patients were male (Table 1). Nine patients (20.8%) had underlying pulmonary diseases, and 28 (71.2%) had non-pulmonary diseases. Seven patients (13.5%) were regarded as severe based on the American Thoracic Society/Infectious Disease of Society of America criteria (8). The laboratory data on admission showed a mean white blood cell count of 9,088±3,162 /μL and C-reactive protein value of 8.19±6.31 mg/dL (Table 2). As the most frequently detected virus, influenza virus was detected in 46.5% of the patients, followed by conventional coronavirus, parainfluenza virus, and human parechovirus (Fig. 1). Lung samples were biopsied in the living patients by transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB) in 37 patients, transbronchial cryobiopsy in 1, and video-assisted thoracic surgery in 3 patients (24 patients breathing ambient air, 16 on low-flow oxygen therapy, and 1 on HFNC therapy), and by autopsy in the other 2 patients. In the overall population, the mean time from the onset of disease to biopsy was 13 (1-40) days; it was 1-14 days in 23 patients (including one autopsy case), 15-28 days in 15 patients, and ≥29 days in 5 patients (including one autopsy case).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics.

| n=43 | |

|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 28 (53.8%) |

| Age, mean±SD | 66.4±10.8 |

| Smoking history, n (%) | 23 (44.2%) |

| Pulmonary underlying disease, n (%) | 9 (20.9%) |

| COPD | 1 (1.9) |

| Bronchial asthma | 2 (3.8) |

| Bronchiectasis | 1 (1.9) |

| Old tuberculosis | 1 (1.9) |

| Interstitial lung disease | 3 (5.8) |

| Post operation of lung cancer | 2 (3.8) |

| None | 34 (65.4) |

| Non-pulmonary underlying disease, n (%) | 28 (71.2%) |

| Hypertension | 13 (30.2) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 1 (1.9) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 8 (15.4) |

| Arrythmia | 3 (5.8) |

| Cardiomyopathy | 2 (3.8) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1 (1.9) |

| Chronic liver disease | 4 (7.7) |

| Connective tissue disease | 2 (3.8) |

| Immunosupressive state due to corticosteroid or immunosupressant | 1 (1.9) |

| Psychiatry disorder | 2 (3.8) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1 (1.9) |

| None | 15 (28.8) |

| Mortality, n (%) | 4 (9.3%) |

SD: standard deviation, COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Table 2.

Treatment during Hospitalization.

| n=43 | |

|---|---|

| Guideline-concordant antibiotics | 33 (30.8%) |

| No antibiotics | 6 (14.0%) |

| Corticosteroid | 26 (60.5%) |

| Pulse therapy | 11 (25.6%) |

| Other than pulse therapy | 15 (34.9%) |

| Neuraminidase inhibitors | 17 (39.5%) |

| Administered within 48 h from onset | 3 (17.6%) |

| High-flow nasal canula | 4 (9.3%) |

| Invasive positive pressure ventilation | 4 (9.3%) |

Figure 1.

Causative viruses. Influenza virus was the most frequently detected virus (46.5%), followed by conventional coronavirus, parainfluenza virus, adenovirus, and others. Because several viruses were detected in some cases, the sum of the number of patients and the percentage values exceeded 43 and 100%, respectively. HRV: human rhinovirus, Flu: influenza virus, CoV: coronavirus, HPIV: human parainfluenza virus, HMPV: human metapneumovirus, RSV: respiratory syncytial virus, Pare: parechovirus, EV: enterovirus, ADV: adenovirus, VZV: varicella-zoster virus, HSV: herpes simplex virus

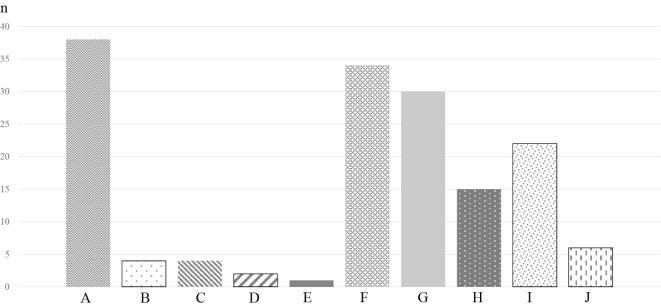

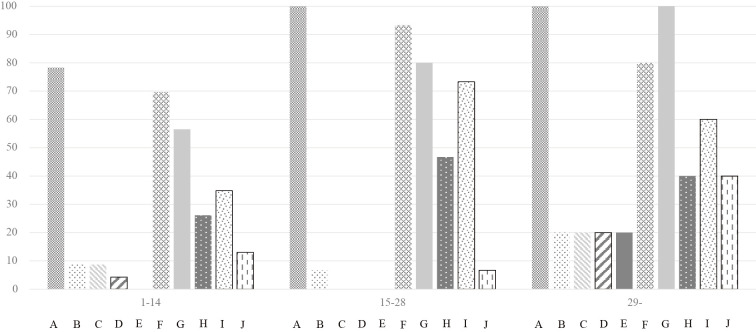

Overall, the most frequent finding was interstitial and intra-alveolar edema (n=38), followed by type 2 pneumocyte hyperplasia with epithelial atypia (n=34) and organized alveoli plus dilated alveolar ducts (n=30) (Fig. 2). Hyaline membranes were found in 3 patients, including the 2 autopsy cases. Interstitial and intra-alveolar edema was most commonly found throughout the disease course (Fig. 3). Overall, the proportion of findings tended to be higher in the later disease course (p=0.013 for 1-14 days versus ≥29 days). The following findings could not be evaluated because of the small sample size and limitations of TBLB: capillary congestion, dilated alveolar ducts plus collapsed alveoli, endothelial necrosis, increased megakaryocytes, platelet-fibrin thrombi, squamous metaplasia with atypia, alveolar loose plugs of fibroblastic tissue, capillary proliferation, microcystic honeycombing, and alveolar multinucleated giant cells. In the delayed phase of the disease, organized alveoli plus dilated alveolar ducts and interstitial and intra-alveolar edema were found in all patients. The proportions of alveolar inflammatory infiltrate (macrophages) differed among the three phases (p=0.030), whereas there was no significant difference in the proportion of other findings.

Figure 2.

Proportion of pathologic findings. Interstitial thickening was the most frequent finding. Hyaline membranes were found in only 3 cases, including the 2 autopsy cases. A: Interstitial and intra-alveolar edema. B: Alveolar hemorrhage. C: Hyaline membranes. D: Alveolar granulocytes. E: Desquamation of pneumocytes. F: Type 2 pneumocyte hyperplasia with epithelial atypia. G: Organized alveoli plus dilated alveolar ducts. H: Interstitial infiltrate. I: Alveolar inflammatory infiltrate (macrophage). J: Fibrin exudation

Figure 3.

Proportion of each pathologic finding and disease day. Interstitial and intra-alveolar edema were frequently found throughout the study period, as was type 2 pneumocyte hyperplasia. The frequency of organized alveoli gradually increased. Fibrin exudation was found in a minority of the population in the early phase and increased after 29 days. A: Interstitial and intra-alveolar edema. B: Alveolar hemorrhage. C: Hyaline membranes. D: Alveolar granulocytes. E: Desquamation of pneumocytes. F: Type 2 pneumocyte hyperplasia. G: Organized alveoli plus dilated alveolar ducts. H: Interstitial infiltrate. I: Alveolar inflammatory infiltrate (macrophage). J: Fibrin exudation.

Thirty-three (30.8%) patients received guideline-concordant antibiotic therapy, whereas 6 (14.0%) did not receive antibiotics (Table 3). Corticosteroids were administered to 26 (60.5%) patients, 11 (25.6%) of whom received pulse therapy. Four patients underwent HFNC, and 4 underwent IPPV.

Table 3.

Laboratory Data on Admission.

| WBC,/μL | 9,088±3,162 |

| Neutrophils, /μL | 6,858±2,743 |

| Lymphocytes, /μL | 1,481±1,058 |

| Eosinophils, /μL | 170±174 |

| Platelet, /μL | 29.1±9.1 |

| D-dimer, μg/mL | 3.31±5.99 |

| AST, IU/L | 42.8±31.1 |

| ALT, IU/L | 35.8±30.6 |

| LDH, IU/L | 297±171 |

| CK, IU/L | 116±234 |

| CRP, mg/dL | 8.19±6.31 |

| KL-6, U/mL | 751±831 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | 499±530 |

| Blood gas analysis | |

| pH | 7.48±0.03 |

| PaCO2, Torr | 33.7±4.16 |

| P/F ratio | 296.7±83.9 |

WBC: white blood cell count, AST: aspartate aminotransferase, ALT: alanine aminotransferase, LDH: lactate dehydrogenase, CK: creatine kinase, CRP: C-reactive protein, P/F: PaO2/FiO2

A summary of the clinical courses of the 41 living patients who underwent lung biopsy is shown in Fig. 4. Nine patients had SLI at the time of the biopsy, and the numbers of patients with each histologic finding of SLI were as follows: prominent type 2 pneumocyte proliferation (atypia with nuclear enlargement, clumped nuclear chromatin, cellular pleomorphism), n=3; hyaline membranes, n=1; foci of acute inflammation and hemorrhage, n=0; excessive fibrin exudation filling alveolar spaces, n=4; and severe intraluminal organization, n=5) (Table 4).

Figure 4.

Schematic illustration of the clinical courses of patients classified based on pathologic pattern. Eight patients were receiving low-flow oxygen therapy when they underwent tissue biopsy, of whom 6 recovered without the need for high-flow nasal cannula or invasive positive pressure ventilation. The other 2 patients developed severe respiratory failure, and one of them died. One patient whose lung tissue was obtained under invasive positive pressure ventilation worsened and died. Among the patients with non-severely lung damage, one patient underwent transbronchial lung biopsy and developed pneumothorax, after which the respiratory condition worsened and the patient died. The remaining 31 patients recovered without the need for a high-flow nasal cannula or invasive positive pressure ventilation.

Table 4.

Patients with Severe Lung Injury Excluding Autopsy Cases, n=9.

| No. | Age, sex | Virus | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Antibiotics | Corticosteroid, per day | Worst respiratory condition | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 81, M | COV 229E, | y | y | LVFX | mPSL 1 g | O2 | Recovery | |||

| HPIV1, RSV | |||||||||||

| 2 | 41, F | ADV | y | y | ABPC/SBT, LVFX | None | O2 | Recovery | |||

| 3 | 77, M | COV 229E | y | PIPC/TAZ | mPSL 1 g | HFNC | Recovery | ||||

| 4 | 60, M | Flu A/H1N1 | y | None | None | O2 | Recovery | ||||

| 5 | 60, F | Flu A | y | CAM | mPSL 1 g | O2 | Recovery | ||||

| 6 | 49, M | Flu A | y | y | ABPC/SBT, MINO | PSL 30 mg | O2 | Recovery | |||

| 7 | 58, M | Flu A | y | LVFX | mPSL 1 g | O2 | Recovery | ||||

| 8 | 70, M | ADV | y | LVFX | PSL 40 mg | IPPV | Death | ||||

| 9 | 72, F | HSV-1 | y | y | AZM | mPSL 1 g | IPPV | Recovery |

COV: coronavirus, ADV: adenovirus, HPIV: human parainfluenza virus, Flu A: influenza virus type A, LVFX: levofloxacin, ABPC/SBT: ampicillin/sulbactam, PIPC/TAZ: piperacillin/tazobactam, MINO: minocyclin, mPSL: methylprednisolone, PSL: prednisolone, HFNC: high-flow nasal canula. Histologic feature of severe lung injury was numbered as 1-5: and existence of each finding indicate `y' (yes). Each number means histologic feature of 1: prominent type 2 pneumocyte proliferation (atypia with nuclear enlargement, clumped nuclear chromatin, cellular pleomorphism), 2: foci of acute inflammation and hemorrhage, 3: organization on the luminal surface of alveolar walls or organization which filled and obliterated whole lumens of alveoli, 4: hyaline membranes, 5: excessive fibrin exudation filling alveolar spaces

A patient who showed hyaline membranes (Table 4, Case 7) suffered from primary influenza virus H1N1 pneumonia and received oseltamivir and corticosteroid therapy, which required inhalation of O2 at 5 L/min, but the patient recovered. One patient (Table 4, Case 3) required HFNC therapy and recovered. However, another (Table 4, Case 8) required HFNC and IPPV, but the airway pressure was elevated, and broad ground-glass opacities with traction bronchiectasis, suggesting diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) were found on computed tomography (CT); this patient ultimately died. A common histologic finding of SLI among patients, which led to severe respiratory conditions was severe intraluminal organization (Table 4). Among the 32 patients without SLI, 1 patient (3.1%) (Table 5, Case 2) developed pneumothorax as a complication of TBLB. A thoracic tube was inserted with continuous suction, but the patient's ground-glass opacities were enlarged, and a pneumothorax developed on the contralateral side. The patient received HFNC, but the respiratory failure worsened, and the patient died. Chest CT showed traction bronchiectasis, which indicated DAD. The other 31 patients recovered with or without low-flow oxygen therapy.

Table 5.

Characteristics of Non-survivors, n=4.

| Case | Age, sex | Virus | Patient’s conditions when tissue was obtained | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Treatment drug | Pulmonary support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 68, F | RV+RSV | Death (autopsy) | y | y | y | Abx plus CS | IPPV | ||

| 2 | 78, M | COV 229, HPIV1 | Alive | Abx plus CS | IPPV | |||||

| 3 | 70, M | ADV | Alive | y | Abx plus CS | IPPV | ||||

| 4 | 65, F | Flu A | Death (autopsy) | y | y | y | y | y | Abx, oseltamivir, CS | IPPV |

RV: rhinovirus, RSV: respiratory syncytial virus, COV: coronavirus, HPIV: human parainfluenza virus, ADV: adenovirus, Flu A: type A influenza virus, Abx: antibiotics, CS: corticosteroid, IPPV: invasive positive pressure ventilation. Histologic feature of severe lung injury was numbered as 1-5: and existence of each finding indicate ‘y’ (yes). Each number means histologic feature of 1: prominent type 2 pneumocyte proliferation (atypia with nuclear enlargement, clumped nuclear chromatin, cellular pleomorphism), 2: foci of acute inflammation and hemorrhage, 3: organization on the luminal surface of alveolar walls or organization which filled and obliterated whole lumens of alveoli, 4: hyaline membranes, 5: excessive fibrin exudation filling alveolar spaces

The frequency of patients progressing to a severe respiratory condition or death did not differ to a statistically significant extent between the patients with (2 of 8, 25.0%) and without (1 of 32, 3.1%) SLI (p=0.096). In patients with SLI, the number of patients who required O2 therapy for <2 weeks (including patients who did not require O2 therapy), those who required O2 therapy for ≥2 weeks, and those who died was 4 (44.4%), 4 (44.4%), and 1 (11.1%), respectively. In patients without SLI, the numbers of patients in the respective groups were 27 (84.4%), 4 (12.5%), and 1 (3.1%). These proportions differed between groups with and without SLI (p=0.033).

The patients who died are listed in Table 5. Case 3 in Table 5 is identical to Case 8 in Table 4. Two living patients whose lung tissue was biopsied were described above. In addition, biopsies were performed at autopsy for 2 patients. Antibiotics, antivirals, and corticosteroid therapy were administered to these 2 patients, but they died of respiratory failure. At autopsy, the lung samples of both patients showed histologic findings compatible with DAD (15).

Discussion

Most of our patients who recovered from primary viral pneumonia showed a nonspecific epithelial injury pattern, and histologic changes other than those of DAD were common, whereas the 2 autopsy cases showed DAD. Two (25.0%) of the 8 patients with SLI progressed to a severe respiratory condition, but only one (3.1%) of the 32 patients without SLI progressed to a severe respiratory condition (p=0.096), although this patient's respiratory condition was not severe at the time of the biopsy.

In the present study, we defined 5 histologic features as representative findings of severe lung injury. Both hyaline membranes and organization on the luminal surface of the alveolar walls or organization that filled and obliterated whole lumens of alveoli were key features of DAD (15). Three other findings [prominent type 2 pneumocyte proliferation (atypia with nuclear enlargement, clumped nuclear chromatin, cellular pleomorphism), foci of acute inflammation and hemorrhage, and excessive fibrin exudation filling alveolar spaces] were not listed as such features (15) but have been reported to be side evidence of severe lung damage. Tissue samples were mainly obtained via transbronchial lung biopsy in our study, and the establishment of a pathological diagnosis of DAD was frequently difficult due to the small sample size. Even if the diagnosis of DAD was not pathologically established, severe lung damage was suggested when at least one of these 3 features was found. Among our 9 patients with SLI, 6 (66.7%) had key features of DAD (1 had hyaline membranes, and the other 5 had severe intraluminal organization).

To date, DAD has been reported as a typical histologic finding of influenza-associated pneumonia and is also reported in COVID-19 (16); however, these histologic findings were obtained in autopsy cases. The 2 autopsy cases in the present study certainly showed DAD, as in other autopsy cases. These findings indicate that DAD is a typical pathological pattern in autopsy cases due to viral pneumonia.

In contrast, histologic findings in patients with viral pneumonia whose lung tissues were obtained while the patients were alive have not been fully reported. Previously, we reviewed a limited number of cases of influenza-associated pneumonia, which showed various histologic patterns, including DAD, organizing pneumonia, and mild inflammatory cell infiltration without SLI (2), which suggests that the histologic patterns of viral pneumonia can vary. Certainly, in the present study, our patients whose lung tissue was obtained when they were alive mainly showed findings other than DAD. Their lung tissue showed various nonspecific findings, including epithelial injury, and these were mixed in various proportions. This indicates that DAD is not a typical finding of viral pneumonia in living patients.

In previous reports, biopsies of 2 patients who underwent lobectomy for lung cancer and accidentally suffered from COVID-19 simultaneously showed SLI but did not show a severe respiratory condition; thereafter, both patients progressed to a severe respiratory condition, and 1 of them died after surgery due to worsening respiratory failure (17,18). These findings indicate that patients with SLI on histology may progress to a severe respiratory condition, even if they do not have respiratory insufficiency at the time of their biopsy. In the present study, we defined 5 histologic features as findings of SLI. Two (25.0%) of our 8 patients with SLI but a non-severe respiratory condition at biopsy progressed to severe respiratory failure or death. Although the frequency of deterioration to severe respiratory conditions did not differ between patients with and without SLI, the proportion of patients who required O2 treatment for ≥2 weeks was higher in patients with SLI than in patients without SLI, which indicates that histologic features correlate with period for O2 recovery. Our study included a small number of patients, and a larger-sized study should investigate histologic findings and clinical outcomes.

Among patients who had severe respiratory conditions, common histologic features were organization on the luminal surface of alveolar walls or organization that filled and obliterated whole lumens of alveoli, which is a key feature of DAD (15), whereas other histologic features of SLI were found in various proportions. One patient (Table 4, Case 9) was under IPPV when tissue samples were obtained, whereas other patients (Table 4, Cases 1, 3, 6, and 8) did not require O2 therapy or required low-flow oxygen therapy at the time of their biopsy, and 2 of the 4 patients with this histologic feature had severe respiratory conditions, which may indicate that an intraluminal organization pattern predicts progression to a severe respiratory condition. Further studies are needed to clarify this.

A previous report classified pulmonary histologic findings of COVID-19 into 3 patterns: epithelial, vascular, and fibrotic patterns (9). The epithelial pattern was found throughout the period, whereas the vascular pattern was found frequently in the early stage of COVID-19. Another report showed that biomarkers of endothelial injury were elevated in acute respiratory distress syndrome due to COVID-19 in comparison to acute respiratory distress syndrome due to other etiologies (19), which indicates that vascular injury was the most common etiology in the early phase of COVID-19 (19,20). A longitudinal study of biomarkers of epithelial and vascular injury showed the importance of vascular injury in COVID-19 (21). In addition, one characteristic of acute respiratory distress syndrome due to COVID-19 is the excessive amount of extravascular water that is present (22,23). Furthermore, a previous study that compared CT findings of COVID-19 with those of viral pneumonia due to other viruses showed differences in various findings, and COVID-19 showed vascular thickening more frequently in comparison to viral pneumonia due to other viruses (24,25). In the present study, vascular lesions themselves could not be easily evaluated due to the small sample size. If we regard fibrin exudation as a marker of vascular injury (9), that feature was found throughout the course of the disease. The proportion of fibrin exudation did not differ among the three disease phases, whereas vascular injury was frequently found in the early phase in COVID-19 (9). However, the number of patients in our study was limited in; thus, whether the frequency of vascular injury differs between COVID-19 and other viral pneumonias remains unknown.

Our 2 autopsy cases showed histologic patterns of DAD. Regarding the 2 other non-survivors whose lung specimens were obtained while they were alive, one patient (Table 4, Case 8) showed severe intraluminal organization which is a key feature of DAD. Another non-survivor (Table 5, Case 2) did not show such findings. Based on the clinical courses and CT findings of these 2 patients, the histologic conditions were speculated to be DAD in the antemortem condition. Two reasons for the gap between histologic findings obtained in living patients and the clinical or CT findings, which were obtained antemortem in these patients and which indicated DAD, can be suggested. One was due to the small size of the TBLB specimen, in which typical histologic changes of DAD could not be detected, and the other was due to the worsening of histologic findings over the clinical course. The former reason indicates that a patient's precise pathophysiological state cannot be determined by tissue biopsy alone, and there are limitations in the ability to predict the patient prognosis and to establish treatment strategies based on histologic findings. Furthermore, in clinical settings, tissue biopsy cannot be performed in all patients, and thus, clinical insight relies upon circumstantial evidence such as laboratory measurements of cytokines and inflammatory markers and radiological evaluation. Therefore, to move toward precision medicine, future research should focus on correlating this clinical information and radiological findings with pathological findings. This approach will require a high level of interaction between clinicians, laboratory personnel, and radiologists to rapidly increase and disseminate knowledge and then apply that knowledge in the clinical setting. Regarding the latter reason, incorrect treatment strategies may cause iatrogenic lung injury. Therefore, physicians are urged to develop adequate treatment strategies.

The present study is associated with some limitations. First, it was a retrospective study that was performed at a single institution. The timing of tissue biopsy differed among patients, and various factors might have influenced the results. Second, most of the lung tissue samples were obtained by TBLB, and the sample size was small; thus, the overall pulmonary conditions may not have been adequately reflected. Third, pulmonary histology was evaluated by a single pathologist, and the consistency of this pathologist's evaluations was not verified. Fourth, patients whose lung tissue samples were not obtained were excluded, which may cause a selection bias.

Conclusion

The present study reported the proportion of each histologic finding in patients with viral pneumonia other than COVID-19 and showed a low proportion of SLI in the survivors. The severity of the pulmonary histology and that of the respiratory condition were not always comparable. Patients with SLI may easily progress to severe respiratory conditions and require a long period of O2 treatment. A small number of our patients without SLI also had poor outcomes, which indicates the limitation of the small size of tissue specimens obtained via TBLB.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

Financial Support

This study was partially supported by grants from Saitama Cardiovascular and Respiratory Center [16ES, 17ES, 18ES, and 19ES].

References

- 1.Yeldandi AV, Colby TV. Pathologic features of lung biopsy specimens from influenza pneumonia cases. Hum Pathol 25: 47-53, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ishiguro T, Takayanagi N, Shimizu Y, Kagiyama N, Yanagisawa T, Sugita Y. A patient who survived primary seasonal influenza viral pneumonia: histologic findings obtained via bronchoscopy. Intern Med 52: 2795-2800, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeon JS, Yi HA, Ki SY, et al. A case of bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia associated with adenovirus. Korean J Intern Med 12: 70-74, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colins P, Crowe J Jr. Respiratory syncytial virus and metapneumovirus. In: Fields Virology. 5th ed. Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DEet al. , Eds. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2007: 368: 73-82. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham B, Rutigliano J, Johnson T. Respiratory syncytial virus immunobiology and pathogenesis. Virology 297: 1-7, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishiguro T, Kobayashi Y, Uozumi R, et al. Viral pneumonia requiring differentiation from acute and progressive diffuse interstitial lung diseases. Intern Med 58: 3509-3519, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishiguro T, Takayanagi N, Yamaguchi S, et al. Etiology and factors contributing to the severity and mortality of community-acquired pneumonia. Intern Med 52: 317-324, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al.; Infectious Diseases Society of America, American Thoracic Society . Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 44: S27-S72, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polak SB, van Gool IC, Cohen D, von der Thusen JH, Paassen J. A systematic review of pathological findings in COVID-19: a pathophysiological timeline and passible mechanisms of disease progression. Mod Pathol 33: 2128-2138, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basset F, Ferrans VJ, Soler P, Takemura T, Fukuda Y, Crystal RG. Intraluminal fibrosis in interstitial lung disorders. Am J Pathol 122: 443-461, 1986. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katzenstein AL. Acute lung injury patterns: diffuse alveolar damage and bronchiolitis obliterans-organizing pneumonia. In: Katzenstein and Askin's Surgical Pathology of Non-neoplastic Lung Diseases. 4th ed. W. B. Saunders, Philadelphia, 2006: 17-49. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basset F, Ferrans VJ, Soler P, Takemura T, Fukada Y, Crystal RG. Intraluminal fibrosis in interstitial lung disorders. Am J Pathol 122: 443-461, 1986. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawabata Y. Pathology of acute interstitial pneumonia. Nihon Kyobu Rinsho (Jpn J Chest Dis) 67: 874-885, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atlas of Nontumor Pathology: Non-neoplastic Disorders of the Lower Respiratory Tract. Travis WD, Colby TV, Koss MN, Eds. American Registry of Pathology and the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington DC, 2002: 83-107. [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society . American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society International Multidisciplinary Consensus Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. This joint statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) was adopted by the ATS board of directors, June 2001 and by the ERS Executive Committee, June 2001. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165: 277-304, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hariri LP, North CM, Shih AR, et al. Lung histopathology in coronavirus disease 2019 as compared with severe acute respiratory sydrome and H1N1 influenza: a systematic review. Chest 159: 73-84, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tian S, Hu W, Niu L, Liu H, Xu H, Xiao SY. Pulmonary pathology of early-phase 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia in two patients with lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 15: 700-704, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeng Z, Xu L, Xie XY, et al. Pulmonary pathology of early-phase COVID-19 pneumonia in a patient with a benign lung lesion. Histopathology 77: 823-831, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spadaro S, Fogagnolo A, Campo G, et al. Markers of endothelial and epithelial pulmonary injury in mechanically ventilated COVID-19 ICU patients. Crit Care 25: 74, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M, et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in COVID-19. N Engl J Med 383: 120-128, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leisman DE, Mehta A, Thompson BT, et al. Alveolar, endothelial, and organ injury marker dynamics in severe COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 205: 507-519, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monnet X, Teboul JL. Transpulmonary thermodilution: advantages and limits. Crit Care 21: 147, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jozwiak M, Teboul JL, Monnet X. Extravascular lung water in critical care: recent advances and clinical applications. Ann Intensive Care 5: 38, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bai HX, Hsieh B, Xiong Z, et al. Performance of radiologists in differentiating COVID-19 from non-COVID-19 viral pneumonia at chest CT. Radiology 296: E46-E54, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang Y, Jiang Y, Li Z, et al. Comparison of initial high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) features of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia and other viral pneumonias. Ann Palliat Med 10: 560-571, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]