Abstract

Background

Early detection of complex diseases like hepatocellular carcinoma remains challenging due to their network-driven pathology. Dynamic network biomarkers (DNB) based on monitoring changes in molecular correlations may enable earlier predictions. However, DNB analysis often overlooks disease heterogeneity.

Methods

We integrated DNB analysis with graph convolutional neural networks (GCN) to identify critical transitions during hepatocellular carcinoma development in a mouse model. A DNB-GCN model was constructed using transcriptomic data and gene expression levels as node features.

Results

DNB analysis identified a critical transition point at 7 weeks of age despite histological examinations being unable to detect cancerous changes at that time point. The DNB-GCN model achieved 100% accuracy in classifying healthy and cancerous mice, and was able to accurately predict the health status of newly introduced mice.

Conclusion

The integration of DNB analysis and GCN demonstrates potential for the early detection of complex diseases by capturing network structures and molecular features that conventional biomarker discovery methods overlook. The approach warrants further development and validation.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Latency detection, Dynamic network biomarkers, Early warning of diseases, Graph convolutional neural networks

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Liver cancer ranks as the 6th most common cancer in the world and is the 3rd leading cause of cancer-related death [55]. It is projected that the incidence of liver cancer will increase by 54.5% from 2020 to 2040, with approximately 1.40 million new cases in 2040 (see Data and Resources) [48]. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), a primary malignancy accounting for more than 85% of primary liver cancers [13], is a multi-stage disease caused by multiple risk factors, typically in the context of underlying cirrhosis. Despite therapeutic advances, the five-year relative survival rate remains low at around 20.8% (2012–2018) (see Data and Resources). The low survival rate is mainly because liver cancer is difficult to detect at an early stage, and patients are often diagnosed at advanced stages when treatment options are limited and development of the disease are almost irreversible [16]. In contrast, early stages of liver cancer development, such as fibrosis and even cirrhosis, are reversible [16], underlining the significance of early detection for treatment efficacy, and as demonstrated by animal model studies, which also provided critical insights into the underlying mechanisms of carcinogenesis [21], [20]. Therefore, early detection is crucial for treating complex diseases such as HCC, as it increases the chance of pre-disease reversal. Unfortunately, there is currently a lack of widely recognized quantitative methods for the early detection of complex diseases.

Biomarkers have emerged as powerful tools for enhancing patient stratification and optimizing clinical outcomes through improving diagnosis, prognosis, and prediction of treatment response. The discovery of biomarkers may inform the biological processes (physiologic or pathologic) related to a disease, as well as pharmacological responses to therapeutic interventions[2]. Therefore, many researchers attempt to identify disease biomarkers from a large number of cellular/molecular data, through the monitoring of certain single molecules to find the correlation between body state changes and disease occurrence [15], [39], [62]. However, this approach often falls short for complex diseases whose pathogenesis is not driven by aberrations of individual genes but is due to the malfunction of the network of interactions among many well-expressed genes [53]. Compounding the problem, people with the same disease may exhibit highly variable expression levels of the same responsible gene, rendering it unsuitable as a single-molecule biomarker. Studying the sub-health state, which is a critical point in the transition from health to disease, presents a significant challenge. This is particularly true because the abnormalities in the expression of individual molecules in sub-health states are not readily apparent. Addressing this challenge is the emerging concept of network biomarkers, which focus on intermolecular network interactions. Such markers are more robust, reliable, and accurate in disease classification than individual biomarkers [5], [23]. Dynamic network biomarker (DNB) theory adds a new dimension to biomarker discovery by emphasizing changes in molecular correlation during disease progression rather than singular molecular expression abnormalities.

DNB theory provides a new method of biomarker discovery based on changes in correlations between molecules during disease progression, rather than abnormalities in molecular expression [6], [32]. When the system is in a critical state between two steady states (e.g., the pre-disease state between health and disease), some genes, whose expressions may be quite normal individually, suddenly show strong inter-correlations, and they become less correlated with other genes. The sub-network formed by these genes, called DNB, can identify the pre-disease state and predict (early warn) the subsequent onset of the disease. The DNB method demands a small amount of data samples, which is advantageous because multiple samples are often unavailable in clinical practice; even one sample may be sufficient, as demonstrated by the single-sample DNB (sDNB) method [35]. Recent years have witnessed significant progress in the development of DNB methods and their application to detect pre-disease tipping points [32], [42], [1], [60]. These methods have been successfully used to predict hepatocellular carcinoma by analyzing functional changes in DNB networks, early warning biomarkers were revealed during disease progression from chronic inflammation to hepatocellular carcinoma [31].

Artificial intelligence (AI), with its potential to bridge academic research and clinical practice, promises further advancements. Machine learning algorithms, specifically, can revolutionize medical diagnosis and prediction by accurately analyzing pathology and imaging results [38], [49]. In the case of HCC, diagnosis and prediction models built on machine learning have improved patients survival and prognosis assessment [9], [50], [33], [26]. Through the optimization of machine learning algorithms, the diagnosis and prediction of HCC can be realized [8], [52]. Nevertheless, accurate diagnosis, staging, and identification of biomarkers continue to pose a significant challenge for HCC patients. The use of DNB for calculations can result in filtering out useful information, thereby hindering accurate early warning signal generation. We believe that this weakness can be remedied by taking advantage of the powerful computational capacities of machine learning methods such as graph convolutional neural network (GCN), which has been applied to predict miRNA-disease associations, and the neural induction matrix completion method using GCNs has achieved high accuracy in breast cancer [30]. Thus, the GCN algorithm can cluster key states in the development of liver cancer through its powerful classification capability, and machine learning based on DNB can provide more accurate and detailed predictions. As a result, timely and more effective treatment plans can be designed based on these predictions. In this paper, early detection of HCC is achieved by integrating DNB with GCN, which demonstrates the great potential of using DNB-GCN for the early warning and diagnosis of complex diseases in general.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Experimental animals

The study was approved by the Animal Experiment Ethics Committee of Southern University of Science and Technology (SUSTech). C3H/HeN male mice (Charles River, 212, Beijing, China),weighing between 15 and 20 g, were used in the study. All the experimental animals were housed in the Animal Experiment Management Center of SUSTech, maintained under appropriate temperature and humidity with a 12-hour light/dark cycle, and provided with ad libitum access to food and water. The mice were acclimatized to their new surroundings and conditions for a week before initiating the experimental procedure.

2.2. Animal models of liver cancer

Constructing effective animal models of human HCC is crucial for understanding its pathogenesis and developing clinical treatments. In this study, we induced liver cancer in male C3H/HeN mice using diethylnitrosamine (DEN) (Macklin, 55–18–5, China), which mimics the pathogenesis of human liver cancer. To this end, we randomly assigned 69 five-week-old male C3H/HeN mice into two groups, with 33 and 36 mice in control group and DEN group, respectively. The control group was injected intraperitoneally with 0.9% normal saline twice weekly, and the DEN group was injected intraperitoneally twice weekly with a dose of 50 mg/kg (body weight) DEN to construct a liver cancer induction model. Both control and DEN experiments were performed at the same time and lasted seven weeks (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

(A) Experimental schedule. Mice were injected with DEN twice a week from the age of 5 weeks, and the drug injection lasted for seven weeks. (B) Growth curve of DEN (blue) and control (green) mice. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. **** P < 0.001 DEN group (36 mice) vs control group (33 mice).

2.3. Hemoperfusion

To eliminate blood, which may interfere with subsequent pathological and sequencing analysis, we performed hemoperfusion on the liver tissues of the experimental mice. The mice were first anesthetized and fixed, and the abdominal and chest cavities were opened with surgical scissors to expose the organs. The perfusion needle was inserted into the mouse posthepatic vein, and the perfusion process started. As the perfusion continued, the liver volume increased and changed from dark red to gray-white. The hepatic portal vein was then cut with scissors to allow blood to flow out, and the perfusion continued until almost all of the blood had flowed out. The removal of blood was necessary to avoid interference with the subsequent analysis of the liver tissues, particularly because red blood cells show strong coloration during histopathological staining.

2.4. Histopathological examination

The use of animal models is essential for studying liver diseases, and histopathology is widely regarded as the gold standard for detecting such diseases. In this study, liver tissue samples were first treated with neutral formalin, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. Subsequently, the samples were sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) using a kit (Solarbio, G1120, China). Finally, digital pathology scans were taken using a versatile scanner (Aperio VERSA 8, Leica) to enable further analysis, such as the detection of HCC.

2.5. Transcriptomic sequencing and analysis

Liver tissue samples were collected from the mice at five different time points (ages 5, 7, 8, 9, and 11 weeks since drug injection), and their cDNA libraries were sequenced on the Illumina sequencing platform by Genedenovo Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Guangzhou, China). The raw image data acquired through sequencing is transformed into sequence data via base calling. Subsequently, fastp[7] is employed for quality control. The RMA algorithm carries out background correction, log2 transformation, and normalization processing to generate processed data with low background signal. This processed dataset comprises expression levels of each transcript at various time points and under different conditions during the progression from healthy liver tissue to liver cancer. The gene expression trend analysis was conducted using the OmicShare tools platform (www.omicshare.com/tools) with Short Time-series Expression Miner software (STEM) [14].

2.6. Assessment of gene expression levels

Utilizing the outcomes of the HISAT2 alignment, we reconstructed transcripts with Stringtie [41] and estimated the expression of all genes in each sample using RSEM[29]. The sequencing depth was adjusted, followed by the correction of gene or transcript length. The FPKM value of each gene was then obtained prior to further analysis. Gene expression levels were quantified by FPKM (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads):

| (1) |

where A is the gene under evaluation, C is the number of sequenced fragments compared to gene A, N is the total number of sequenced fragments compared to the reference gene, and L is the number of bases of gene A. The FPKM method can effectively normalize the impact of gene length and sequencing depth differences on the calculation of gene expression, and the result can be directly used to compare the gene expression differences across different samples.

2.7. Group difference analysis

The input data for gene differential expression analysis, derived from the reads count data obtained in the gene expression level analysis, is processed using DESeq2 software [36]. The analysis is primarily divided into three parts:

-

1)

Normalization of read counts;

-

2)

Hypothesis test probability (p-value) calculation is performed based on the model. The computational model employs a negative binomial generalized linear model to estimate gene expression levels and detect differential expression.

-

3)

Lastly, the BH (Benjamini-Hochberg) method is applied to correct the p-values in multiple tests. Based on the results of the difference analysis, genes with FDR < 0.05 and |log2FC| > 1 are selected as significantly different genes.

2.8. Dynamical network biomarker

Based on the processed transcriptomic data, we identified pre-disease states or tipping points by DNB models according to the following three criteria defined in[6], [1].

-

1.

The emergence of a group of genes whose mean Pearson’s correlation coefficients (PCCs) of gene expression levels had a sharp increase in absolute value.

-

2.

The average PCCs between the group and any other molecule (i.e., between molecules of the group and any other molecules outside of the group) decreased sharply.

-

3.

The mean standard deviations (SDs) of molecules in this group increased dramatically.

When all the three criteria are satisfied, the group is called a DNB of the system. The emergence of DNB reflects the transition of the mouse’s health state from normal to diseased. To obtain a strong signal in the pre-disease state, the three criteria are combined by defining a composite index [6], [34]:

| (2) |

where PCCin represents the PCC of the DNB; PCCout represents the PCC between DNB and the other genes; ε is a small positive number, and we use . A sudden increase in to a peak value signifies that the system is in a critical state, whereby the DNB can be identified. Therefore, the dynamical change in and the emergence of DNB would provide early signals warning the imminent development of liver cancer.

2.9. Graph convolutional network

In this paper, GCN is a neural network architecture operating on graphs structured by the transcriptomic data such that the graph nodes iteratively update their representations by exchanging information with their neighbors in a convolutional manner. We used a common supervised computing framework, time-specific transcriptome expression data and DNB network computing methods to characterize the disease progression. We refer to the graph convolutional neural network developed by Thomas Kipf and Max Welling [24] for further computation of the DNB network. The basic formula for the GCN network layer is

| (3) |

where refers to the input feature of the l-th layer, refers to the output feature, refers to the transformation matrix, and refers to the nonlinear activation function, such as ReLU, Sigmoid, etc.

2.10. Statistical analysis

To ensure the reliability of our findings, changes in mouse weight data were statistically analyzed. A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test with multiple comparisons was used to compare mean weight changes. The data were represented as mean ± standard error (SEM), and the statistical analysis was conducted using Prism 9 (GraphPad).

3. Results

3.1. Liver cancer development and histopathological examination

During the DEN/saline administration, six mice out of 36 in the DEN group died, resulting in a mortality rate of 16.7%, which is close to other similar studies (approximately 20%) [11]. Conversely, no mortality was observed in the control group. An examination of Fig. 1B elucidates the weight fluctuations between the control and DEN mice. While the control group experienced consistent weight gain throughout the course of the study, the DEN group exhibited a steady decrease in body weight. This weight loss was a result of the chemically-induced liver carcinogenesis that initiated an irreversible process characterized by structural DNA changes [43]. The DEN injection caused significant liver damage, leading to the impaired normal liver function, particularly in the inactivation of food and nutrient absorption. Chronic liver damage can promote cirrhosis and carcinogenesis, with cancerous tissue potentially undergoing necrosis and releasing toxic substances into the bloodstream. The cancer tissue might undergo necrosis with toxic substances released into the circulation, which further increased the burden on the liver and impaired the body's normal functions such as digestion and absorption. As a result, the DEN mice entered a vicious circle that accelerated the disease deterioration, ultimately leading to malnutrition, emaciation, and even death.

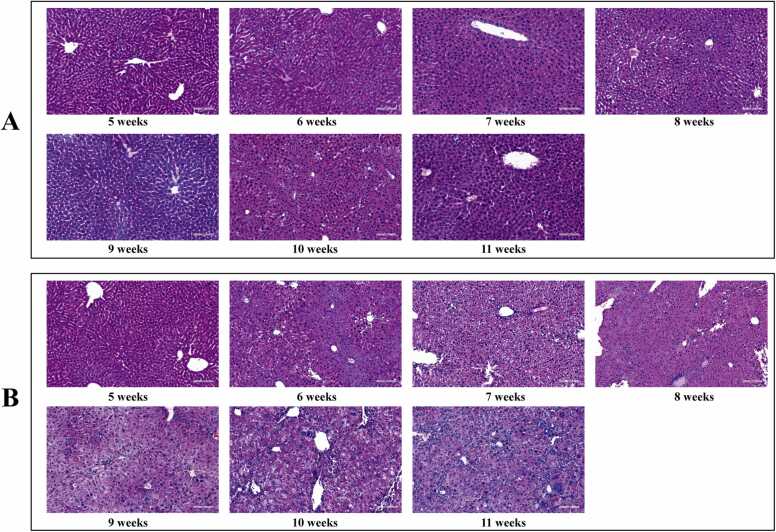

The gradual accumulation of gene mutations in hepatocytes led to malignant transformation, resulting in the development of HCC. Examination of the liver histopathology of mice at various ages revealed that the livers of control mice remained normal throughout the study without any observable histological changes (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the DEN group (Fig. 2B) showed different stages of morphological changes starting from week 7. Although no obvious cancer morphology was observed at week 7, the cells display edema with sparse/loosening cytoplasm and a centrally suspended nucleus, and were slightly to moderately eosinophilic with cytoplasm ranging from finely granular to transparent. By week 8, some cells became smaller than the adjacent hepatocytes, showing cytoplasmic basophilia, mild nuclear atypia and hyperchromatism, with small nuclei showing regional aggregation. From week 9 onwards, there were different shades of nuclear staining, the ratio of nucleus to cytoplasm was close to normal, nucleoli became obvious, few cells were in the division phase, and cancer cell characteristics appeared such as giant size and irregular shape. In HE staining, the nuclear membrane and chromatin agglutination/granules were often basophilic; the nucleoli were generally eosinophilic, but some were dichroic to basophilic due to their chromatin overlay. When pseudo inclusion bodies or inclusion bodies entered the nucleus, the nucleus changed its color. HE staining sections demonstrated that the DEN-induced hepatocellular carcinoma cells deteriorated progressively morphologically. Although cancerous features were observed in mice at age 9 weeks, it was challenging to determine whether the liver had become cancerous at 7–8 weeks based solely on HE staining.

Fig. 2.

HE staining. (A) Liver histology of the control group. (B) Liver histology of the DEN group. Representative photographs of HE at 5–11 weeks (×100).

3.2. Transcriptomic analysis

We performed transcriptomic analysis of liver samples collected from mice at different time points. To minimize potential bias caused by RNA extraction and subsequent analyses, we conducted principal component analysis (PCA) to filter out noise and unimportant information and obtain the major features of the data. Through result analysis (Fig. 3A), the major differences (PCA1) explained 56.2% of the total variance, which was caused by the injection of different reagents (saline versus DEN) in mice. The second principal component (PCA2) contributed 29.9% to sample differences. According to its distribution pattern, we believe this was caused by the increase in injection reagent time and mouse age. In the PCA plot, the proximity of two samples is directly proportional to their similarity. Samples belonging to the same treatment group often form a cluster, indicating that they have similar characteristics. The PCA results were highly consistent, and all control group (DEN group) mice were on the left side of the PCA1 boundary. Mice injected with DEN separated along the PCA2 axis with increasing injection time and mouse age. Interestingly, the three D11 samples (D11W1, D11W2, D11W3) were well separated along the vertical (PCA2) direction, which may be due to differences in individual responses to cancer progression. By using transcriptomic expression data, we performed hierarchical clustering to determine the relationship between all samples. The sample clustering map in Fig. 3B reflects the connection between samples. The results show that the samples exhibited good reproducibility and were consistent with the PCA results, indicating that the clustering had good internal homogeneity and large external heterogeneity. By generating reproducibility scatter plots (Supplementary Fig. S1), we evaluated the reproducibility of samples within groups. The larger the Pearson correlation coefficient, the stronger the correlation between two samples. Biological replicates at each time point showed a high correlation.

Fig. 3.

Analysis of relationships between samples. (A) Principal component analysis. The colored points indicate the individual samples. (B) Sample clustering plot. The vertical axis denotes the Euclidean distance between samples. Each smallest branch of the dendrogram represents a sample, with closer proximity between samples indicating higher similarity. (C) Comparative volcano plot of DEGs in mice of different ages. The horizontal coordinate measures the log2 of the difference between the two groups (in fold), and the vertical coordinate measures the negative Log10 of the FDR of the difference between the two groups. (D) Comparative cluster analysis of DEGs at ages 7, 8, 9, and 11 weeks. In the heatmap, each row (column) corresponds to a gene (sample).

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) analysis helps identify potential cancer biomarkers [17]. Samples from different backgrounds (different species, tissues, and periods) can be used for RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) to identify DEGs, which may reveal the underlying molecular mechanisms of cancer development [40]. In this study, we obtained gene expression statistics from our transcriptome samples, as shown in Supplementary Data 1. Figs. 3C and 3D display the degree of expression difference among the significant DEGs in a volcano plot format. Fig. 3C comprises volcano plots depicting the relationship between FDR and fold change (fc) for the DEGs. The plots use red and blue colors to respectively represent higher and lower levels of gene expression, with deeper shades indicating more significant changes. The positioning of blue (red) dots skewed towards the left (right) indicates a DEN-induced decrease (increase) in gene expression. The degree of skewness indicates the extent of the expression change. The heat maps in Fig. 3D show the hierarchical clustering of DEGs and the comparison between different samples. The expression value of each gene (row) is normalized across all samples (columns) using z-score calculation (i.e., subtracting the mean gene expression in all samples and then dividing by the standard deviation of gene expression values in all samples). Genes with similar expression patterns in the differential gene clustering may share common functions or participation in common metabolic/signaling pathways. Our results revealed dramatic changes in gene expression and transcriptional reprogramming during DEN-induced liver cancer development.

We then conducted functional enrichment analysis on the DEGs, including Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis. To visualize the changes in gene expression during the transition from a healthy to a cancerous state in the mouse liver, we conducted a Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis using the ratio between the number of up-regulated and down-regulated DEGs divided by the total number of DEGs (Fig. 4, AB). The resulting plot provides valuable insights into the dynamics of gene expression in this context. Evidently, the DEN exposure significantly perturbed the body’s physiology and cancer pathogenesis, leading to the upregulation of genes of the immune system and stressed response system. The KEGG analysis mapped a total of 9221 genes to signaling pathways, and the pathways with significant DEGs enrichment varied significantly at different ages (7, 8, 9, and 11 weeks). The KEGG analysis revealed that DEN was activated by cytochrome P450 protein (CYP) (Fig. 4C), leading to the formation of mutagenic DNA adducts, DNA breakage, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, oxidative stress, and ultimately the promotion of liver cancer development [61]. CYP plays a key role in various physiologic and pathologic processes including the pathogenesis of cancer [27]. The p53 signaling pathway was also significantly altered (Fig. 4C). The tumor suppressor gene p53 protects against DNA damage in organisms exposed to different toxic pressures and provides a genetic defense against cancer, and deletion or mutation of p53 is common in advanced liver cancer [28]. Existing studies suggest a possible causal relationship between genetic damage and sustained activation of p53, chronic hepatitis, and HCC development [59]. These data suggest that strong activation of p53 following DEN-induced DNA damage is a possible mechanism through which hepatic pro-tumor inflammation is induced. Although there are some common molecular changes, the cellular and molecular basis of liver cancer development may differ significantly in cancers of different etiologies. These differences may provide mechanistic clues and opportunities for prevention or treatment. Pathological examination using HE staining alone cannot determine whether cancerous changes have occurred in 7-week-old mice, but transcriptome sequencing analysis has shown significant changes in internal macromolecular expression and protein binding. The carcinogenesis of mouse liver involves the transformation of normal cells into precancerous lesions and the development of malignant tumors. After tumor formation, the interaction of different types of cells in the tumor stroma with extracellular matrix (ECM) components directly or indirectly leads to the abnormal phenotype associated with this transformation.

Fig. 4.

RNA-seq DEGs enrichment analysis in C3H mice at different times. (A) GO enrichment circle chart. (B) GO enrichment difference bubble chart. The GO terms are represented by the bubbles whose abscissa is the z-score value, whose ordinate is −log10 (Q value), and whose size corresponds to the number of enriched DEGs. The yellow line represents the threshold of Q value= 0.05. (C) KEGG enrichment bar chart. The percentage of the pathway associated DEGs over the total DEGs are illustrated by the abscissa.

The gene expression changes induced by DEN exposure in mouse livers can provide valuable insights into the biological mechanisms underlying liver cancer development. In this study, we aimed to investigate the trends manifested by the DEGs and perform KEGG enrichment analysis for each trend. To be qualified for the trend analysis, a gene must satisfy the following two conditions: 1) the max/min ratio of expression level must be smaller than a threshold (Q value ≤ 0.05), and 2) the correlation coefficients with all the trends must be smaller than a threshold (Q value ≤ 0.05). We then performed co-expression analysis of the DEN groups at five different time points during liver cancer development and classified the 1073 DEGs into 20 different change modes (Fig. 5A). Detailed statistics are provided in Supplementary Data 2. We identified 68 DEGs in Profile 0 (Fig. 5A, B), showing a downward trend in expression, with high (low) expressions at five (eleven) weeks of age. It is noteworthy that multiple genes involved in sex hormone synthesis show significantly higher transcript abundance at five weeks of age. We also identified 149 DEGs identified in Profile 18 (Fig. 5A, B), showing a trend of first increasing and then decreasing in expression, with low expression at five weeks of age and a plateau at 8 or 9 weeks of age. Moreover, multiple genes related to drug metabolism and cytochrome P450 synthesis have higher transcript abundances at this stage. In contrast, the 650 DEGs in Profile 19 (Fig. 5A, B) show a trend opposite to that seen in Profile 0, with low (high) expression at five (eleven) weeks of age. These genes are predominantly enriched in the p53 signaling pathway and intercellular junctions associated with cell adhesion factor expression (Fig. 5C), possibly due to occurrence of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). During an EMT, epithelial cells lose polarity and cell-to-cell adhesion, significantly increasing cell motility, aggressiveness and their ability to degrade extracellular matrix (ECM) components, thereby increasing their ability to spread throughout the body. Transcription factors that promote the EMT, including Snail, Slug, Twist, and Zeb, are also upregulated during HCC progression[44], [57]. This suggests that the EMT plays a crucial role in HCC progression. The molecular mechanisms underlying the EMT may have diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic implications for HCC. Moreover, a DNB with SMAD7 and S ERPINE1 as the core was discovered, which can be used to detect the EMT critical point induced by TGF-β[22]. Combined with DNB calculation, transcriptomic analysis can deepen our understanding of biological processes such as liver cancer development.

Fig. 5.

Trend analysis of liver transcriptome evolution in C3H mice. (A) The total 20 trend pattern profiles. The gray lines show the trend of individual genes, and the black line shows the overall trend. (B) Bar representation of the profiles, with the color indicating the P value and the number indicating the number of genes. (C) KO enrichment bubble chart of three important profiles. The color, size, and abscissa of a bubble indicate its Q value, number of DEGs, and Rich Factor value, respectively.

3.3. DNB analysis of liver transcriptomics

The study of DNB theory introduces an innovative approach to biomarker discovery, leveraging the principles of nonlinear dynamics during disease progression [6], [32]. This theory distinguishes itself with its capacity to pinpoint the critical transition state between multiple steady states utilizing a relatively small dataset. This critical state is manifested through the abrupt emergence of a sub-network within an extensive biomolecular network, which fulfills the aforementioned three conditions, thereby classifying it as a DNB, a potential biomarker. The DEN-induced evolution of gene expression in mouse livers may provide great insights into the biological mechanisms underlying liver cancer development. To further delve into this possibility, we utilized DNB analysis to identify the DNB sub-network during the development of DEN-induced liver cancer in mice. According to DNB theory, the development of DEN-induced liver cancer in mice can be divided into three stages: a pretransition state (normal), a transitional state (disease incubation), and a post-transitional state (HCC). Throughout the incubation period, some genes, seemingly exhibiting normal expressions when considered individually, abruptly display strong inter-correlations, while their correlations with other genes diminish. The sub-network constituted by these genes embodies the DNB.

To assess the effectiveness of DNB analysis in disease prediction, we analyzed high-throughput experimental data obtained from mouse liver samples of both control and DEN groups. We first pre-processed the raw data, which included 22321 raw probes according to the method described in reference [46]. After preprocessing, we were left with 11251 genetic data which we then standardized according to the transcriptome treatment. We analyzed genes based on their PCC values and divided each time point into 40 classes. Subsequently, we calculated the composites indicator I at each time point (Fig. 6D), highlighting its alterations, and deduced that the critical transition point was approximately at the seven-week mark. This study demonstrates the utility of DNB analysis in identifying critical transitions during disease progression and highlights its potential for developing biomarkers for liver cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Fig. 6.

Detection of disease warning signs using DEN-induced liver cancer experimental data. (A) Average SD in the DNB (Criterion 3 of DNB). (B) Average PCC in the DNB (Criterion 1 of DNB). (C) PCC between DNB and other molecules (Criterion 2 of DNB). (D) Composite index. The black line indicates the critical state period prior to the disease. The black solid line indicates the early warning period of the disease.

To distinguish the dynamics of DNB from those of other molecules, we graphically present the dynamic changes in DNB scores, providing clear evidence of the crucial role of DNB in changes in gene expression during a critical time period, namely around 7 weeks of age. As shown in Fig. 6, the DNB-based composite index during HCC consistently mirrors the observed biological phenotype. The strongly correlated subnetwork formed by DNB serves as crucial warning signals during periods proximate to the critical state, i.e., at 7 weeks of age. Prior to disease onset, DNB genes and other genes did not exhibit significant differences in expression at any of the examined time points. However, at 7 weeks of age, the DNB criteria were met by the DNB members, thereby providing a clear indication of the imminent cancer development and enabling early interventions. In contrast, pathological examination at 7 weeks of age cannot predict the cancer development, despite revealing some abnormalities in the body.

3.4. DNB-GCN model

DNB analysis enables the identification of significant inflection points in disease onset through time series analysis, providing core change networks and signal nodes of high importance. Utilizing DNB calculations, we have identified a critical turning point in liver cancer occurring at seven weeks in mice. Through DNB calculations, we have screened 197 key genes from transcriptome expression data, analyzing their PCC and dynamic changes. However, it is important to note that while DNB data for mice is labeled as "healthy" or "HCC", this approach may overlook certain interactions and fail to identify commonalities in disease occurrence among different individuals. Furthermore, relying solely on DNB testing is insufficient for detecting and accurately identifying the health status of various samples. Therefore, we have integrated DNB with the deep learning method of GCN to characterize critical states and enable early disease diagnosis. This integrated approach allows for a more comprehensive analysis, enhancing the accuracy of disease identification.

To fully utilize the information available, we constructed a graph-based model, as depicted in Fig. 7A, using mice as nodes, different time periods as node features, and the expression levels of mouse DNB molecular network as structural information. In this experiment, we analyzed 27 liver tissue samples from mice, of which 12 were from mice with liver disease (circles with yellow-filled backgrounds in Fig. 7A) and 15 were from healthy mice (circles with blue-filled backgrounds in Fig. 7A). The samples were randomly divided into three groups: a training set (3 diseased and 3 unaffected, red outer circles in Fig. 7A), a validation set (2 diseased and 4 unaffected, black outer circles in Fig. 7A), and a test set (7 diseased and 8 unaffected, green outer circles in Fig. 7A). To confirm the stability of our results, we repeated the random sampling process four additional times, while maintaining the balance between the two types of samples. The consistent training outcomes demonstrated the stability of our DNB-GCN model. Detailed results can be found in Fig. S2 of the supplementary materials. Each sample provided detailed node information for 197 features, a set of genes screened by DNB to identify significant transitions in HCC development based on time-series transcriptomics data (see Supplementary Data 3 for detailed data). Our objective was to use GCN to gain insights into the relationship between disease signatures and health in mice, with a focus on improving our understanding of liver disease. The workflow of the entire model is depicted in Fig. 7B. We trained GCN using DNB data from the six samples in the training set, repeatedly using the output of each layer as the input of the next layer to learn node characteristics and network structure information to establish the relationship between DNB characteristics and health states (i.e., health or HCC) (see "Data and resources"). We then performed a weighted average of each node's information and its neighbors to obtain a result vector that could be passed into the neural network. Finally, we validated and tested the trained GCN on the corresponding datasets. After manual debugging in the GCN model, we set the dropout rate to be 0.18, the number of epochs set to be 40, and the activation function to be the ReLU function .

Fig. 7.

Graph convolutional neural network computation. (A) The diagram depicts the GCN structure for mice. Each small circle represents a mouse, while the dotted rings surrounding them indicate mice of different ages. (B) GCN workflow. (C) The graph displays the change in error rate. (D) The ROC curve.

As illustrated in Fig. 7C, the error rates for the training set, validation set, and test set exhibit fluctuation as the number of learning iterations, and the error rate decreases with increasing learning time. The error rate of the training set eventually stabilizes at 0, indicating a successful training process. The confusion matrix presented in Table 1 indicates that the DNB-GCN model accurately identifies the state of the mouse, further demonstrating the model's proficiency in distinguishing between healthy and disease states, with 100% accuracy for perfect learning. This is also supported by the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve in Fig. 7D, demonstrating the model's proficiency in distinguishing between healthy and disease states. To demonstrate the effectiveness of our DNB-GCN model, we randomly selected 15 mice (8 healthy mice and 7 DEN mice) and utilized their DNB data as input to the GCN to predict their health status. We further assessed the performance of our DNB-GCN model using three-fold cross-validation (see Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Material for details). The multiple outcomes obtained in this manner contribute to a more reliable estimation of the model's performance. These findings provide compelling evidence for the superior predictive power of our DNB-GCN model and further underscore its promising potential.

Table 1.

Confusion matrices.

| Predicted class |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | Non-disease | ||

| Actual class | Disease | 7 | 0 |

| Non-disease | 0 | 8 | |

4. Discussion

HCC poses a global health challenge with regards to prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Experimental models of chronic liver injury and HCC have been developed to simulate various etiologies and disease progression. However, due to the use of animals with different genetic backgrounds and the presence of various environmental factors, these models have varying induction cycles [18], [47], [10], [54], [51], [37], [3], [56], [19]. In the present study, we found that twice-weekly administration of 50 mg/kg body weight DEN to 5-week-old male C3H mice rapidly induced liver cancer. The mortality rate in the DEN group was 16.7%, while there were no deaths in the control group. The use of the DEN-induced HCC mouse model mimics the detailed characteristics of HCC development and can aid in characterizing the progression of liver cancer at the molecular level. The model significantly reduces the time required to induce liver cancer, with lesions appearing in mice 3–4 weeks after DEN induction. However, the model may not be suitable for studying other liver diseases such as hepatitis B and alcoholic fatty liver.

By analyzing relationships between-sample, differences between groups, and expression trends, we found that mice undergo significant changes in gene expression and transcriptional reprogramming during DEN-induced liver cancer development. We assessed the reliability of the animal models employed in our study through transcriptomic analysis; however, relying solely on traditional transcriptomic methods may not provide sufficient information. Recent breakthroughs in machine learning and big data have led to a proliferation of AI applications in biomedical research. These applications range from disease diagnosis [38], [12], [58], [63] and prediction to predicting treatment outcomes [50], [25], [4]. Deep learning techniques have shown promise in advancing these efforts by enabling the discovery of complex patterns and relationships in biological systems. However, because biological systems are complex and involve multiple intrinsic and extrinsic factors, relying solely on model studies such as dynamic network markers computed for large-scale data may overlook critical interactions and prevent the targeted identification of commonalities in disease occurrence across individuals. The combination of machine learning and biomarkers can deeply explore the mysteries of life and provide more reliable clinical help [45].

This study demonstrates the potential of integrating dynamic network biomarker theory and graph convolutional neural networks for the early detection of complex diseases like hepatocellular carcinoma. Traditional methods of identifying biomarkers have focused on detecting abnormalities in the expression of individual molecules. However, for complex diseases driven by network dysregulations, dynamic network biomarkers that monitor changes in correlations between molecules during disease progression may provide more accurate predictions. As shown in the article, DNB analysis was able to identify a critical transition point at 7 weeks of age in the DEN-induced liver cancer mouse model, despite histological examinations being unable to detect cancerous changes at that time point. However, DNB analysis alone may overlook important interactions and fail to distinguish between individuals with different disease courses. Therefore, integrating DNB with machine learning methods like graph convolutional neural networks can provide more precise diagnoses by capturing network structures and molecular features. As demonstrated, the DNB-GCN model achieved 100% accuracy in classifying mice as healthy or having liver cancer, outperforming DNB analysis alone. The model was also able to accurately predict the health status of newly introduced samples.

In summary, the integration of dynamic network biomarkers and deep learning algorithms shows promise for the early detection of complex diseases. This approach helps overcome some of the limitations of conventional biomarker discovery methods. With further development and validation, it may facilitate the timely diagnosis and treatment of diseases like hepatocellular carcinoma.

5. Final consideration

The central aim of this study was to enhance the early detection of HCC and optimize the application of Dynamic Network Biomarkers (DNB). To achieve this, we utilized animal models to refine our understanding of the progression of HCC and leveraged high-throughput sequencing to delve into the molecular mechanisms underpinning hepatocarcinogenesis. Drawing on transcriptomic data, we applied DNB network calculations to identify significant inflection points in the progression of HCC, with the overarching objective of refining disease diagnosis techniques. Our study introduced a composite model (DNB-GCN) that synergizes dynamic network biomarker algorithms with deep learning algorithms, thereby facilitating the mining of hidden patterns within large datasets. This, in turn, leads to improved accuracy in disease diagnosis. Our animal model was highly effective, providing earlier disease diagnosis than traditional pathological testing and paving the way for advancements in personalized precision medicine. Moving forward, our research will focus on deepening our understanding of the intricate relationship between DNA, RNA, and protein at a multi-omics level. This will involve exploring cellular-level networks from a systems biology standpoint. Our goal is to maximize the potential for advanced warning and disease diagnosis during the latent phase of complex diseases. By combining clinical sample data, the model is translated into clinical applications. By doing so, we aim to contribute meaningfully to the field of biomedical research and pave the way for innovative diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in the future.

Data and resources

The five-year relative survival rate of liver cancer patients is from National Cancer Institute (https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/livibd.html). The RNA-seq data mentioned in this paper have been uploaded to the NCBI database (PRJNA931809). The graph convolutional neural network calculator uses GitHub open-source code (https://github.com/rexrex9/recbyhand/tree/main/chapter4).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yukun Han: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Javed Akhtar: Investigation. Guozhen Liu: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Writing - original draft. Chenzhong Li: Investigation, Resources, Writing - original draft. Guanyu Wang: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2019YFA0906002), National Natural Science Foundation of China (61773196, 32070681, 22174121, 22211530067, T2250710180), Shenzhen Peacock Plan (KQTD2016053117035204), Shenzhen-Hong Kong Cooperation Zone for Technology and Innovation (HZQB-KCZYB-2020056), Guangdong Provincial Research Funds (2019B030301001), Guangdong Peral River Talent Program (2021CX02Y066), Shenzhen Bay Laboratory Open Fund 2021, and by 2022 Shenzhen College Stable Support Program.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2023.07.002.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

Supplementary material

.

Supplementary material

.

Supplementary material

.

References

- 1.Aihara K., Liu R., Koizumi K., Liu X., Chen L. Dynamical network biomarkers: theory and applications. Gene. 2022;808 doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2021.145997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biomarkers Definitions Working G. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: preferred definitions and conceptual framework. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;69:89–95. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2001.113989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chappell G., et al. Genetic and epigenetic changes in fibrosis-associated hepatocarcinogenesis in mice. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:2778–2788. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen D., et al. Integrated machine learning and bioinformatic analyses constructed a novel stemness-related classifier to predict prognosis and immunotherapy responses for hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Int J Biol Sci. 2022;18:360–373. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.66913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen L., Wu J. Systems biology for complex diseases. J Mol Cell Biol. 2012;4:125–126. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjs022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen L., Liu R., Liu Z.P., Li M., Aihara K. Detecting early-warning signals for sudden deterioration of complex diseases by dynamical network biomarkers. Sci Rep. 2012;2:342. doi: 10.1038/srep00342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen S., Zhou Y., Chen Y., Gu J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:i884–i890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng B., Zhou P., Chen Y. Machine-learning algorithms based on personalized pathways for a novel predictive model for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Bioinforma. 2022;23:248. doi: 10.1186/s12859-022-04805-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi G.H., et al. Development of machine learning-based clinical decision support system for hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2020;10:14855. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-71796-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dapito D.H., et al. Promotion of hepatocellular carcinoma by the intestinal microbiota and TLR4. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:504–516. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding Y.F., Wu Z.H., Wei Y.J., Shu L., Peng Y.R. Hepatic inflammation-fibrosis-cancer axis in the rat hepatocellular carcinoma induced by diethylnitrosamine. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143:821–834. doi: 10.1007/s00432-017-2364-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elmarakeby H.A., et al. Biologically informed deep neural network for prostate cancer discovery. Nature. 2021;598:348–352. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03922-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Serag H.B., Rudolph K.L. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2557–2576. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ernst J., Bar-Joseph Z. STEM: a tool for the analysis of short time series gene expression data. BMC Bioinforma. 2006;7:191. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ford D., et al. Genetic heterogeneity and penetrance analysis of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in breast cancer families the breast cancer linkage consortium. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:676–689. doi: 10.1086/301749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman S.L. Liver fibrosis - from bench to bedside. J Hepatol. 2003;38(Suppl 1):S38–S53. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Govindarajan M., Wohlmuth C., Waas M., Bernardini M.Q., Kislinger T. High-throughput approaches for precision medicine in high-grade serous ovarian cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:134. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00971-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hacker H.J., Mtiro H., Bannasch P., Vesselinovitch S.D. Histochemical profile of mouse hepatocellular adenomas and carcinomas induced by a single dose of diethylnitrosamine. Cancer Res. 1991;51:1952–1958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iatropoulos M.J., Jeffrey A.M., Schluter G., Enzmann H.G., Williams G.M. Bioassay of mannitol and caprolactam and assessment of response to diethylnitrosamine in heterozygous p53-deficient (+/-) and wild type (+/+) mice. Arch Toxicol. 2001;75:52–58. doi: 10.1007/s002040000211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iredale J.P., et al. Mechanisms of spontaneous resolution of rat liver fibrosis Hepatic stellate cell apoptosis and reduced hepatic expression of metalloproteinase inhibitors. J Clin Investig. 1998;102:538–549. doi: 10.1172/JCI1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iredale J.P. Hepatic stellate cell behavior during resolution of liver injury. Semin Liver Dis. 2001;21:427–436. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-17557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang Z., et al. SMAD7 and SERPINE1 as novel dynamic network biomarkers detect and regulate the tipping point of TGF-beta induced EMT. Sci Bull. 2020;65:842–853. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2020.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin G., et al. The knowledge-integrated network biomarkers discovery for major adverse cardiac events. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:4013–4021. doi: 10.1021/pr8002886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kip F, T.N. & Welling, M. Semi-Supervised Classification with Graph Convolutional Networks. (2016).

- 25.Ksiazek W., Gandor M., Plawiak P. Comparison of various approaches to combine logistic regression with genetic algorithms in survival prediction of hepatocellular carcinoma. Comput Biol Med. 2021;134 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ksiazek W., Turza F., Plawiak P. NCA-GA-SVM: A new two-level feature selection method based on neighborhood component analysis and genetic algorithm in hepatocellular carcinoma fatality prognosis. Int J Numer Method Biomed Eng. 2022;38 doi: 10.1002/cnm.3599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwon Y.J., Shin S., Chun Y.J. Biological roles of cytochrome P450 1A1, 1A2, and 1B1 enzymes. Arch Pharm Res. 2021;44:63–83. doi: 10.1007/s12272-021-01306-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levine A.J., Oren M. The first 30 years of p53: growing ever more complex. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:749–758. doi: 10.1038/nrc2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li B., Dewey C.N. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinforma. 2011;12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li J., et al. Neural inductive matrix completion with graph convolutional networks for miRNA-disease association prediction. Bioinformatics. 2020;36:2538–2546. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li M., et al. Dysfunction of PLA2G6 and CYP2C44-associated network signals imminent carcinogenesis from chronic inflammation to hepatocellular carcinoma. J Mol Cell Biol. 2017;9:489–503. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjx021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li M., Zeng T., Liu R., Chen L. Detecting tissue-specific early warning signals for complex diseases based on dynamical network biomarkers: study of type 2 diabetes by cross-tissue analysis. Brief Bioinform. 2014;15:229–243. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbt027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu K., et al. Construction and validation of a nomogram for predicting cancer-specific survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Sci Rep. 2020;10:21376. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78545-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu R., et al. Identifying critical transitions and their leading biomolecular networks in complex diseases. Sci Rep. 2012;2:813. doi: 10.1038/srep00813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu X., et al. Quantifying critical states of complex diseases using single-sample dynamic network biomarkers. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Love M.I., Huber W., Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGlynn K.A., et al. Susceptibility to aflatoxin B1-related primary hepatocellular carcinoma in mice and humans. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4594–4601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Menegotto A.B., Becker C.D.L., Cazella S.C. Computer-aided diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma fusing imaging and structured health data. Health Inf Sci Syst. 2021;9:20. doi: 10.1007/s13755-021-00151-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nogueira Jorge N.A., Wajnberg G., Ferreira C.G., de Sa Carvalho B., Passetti F. snoRNA and piRNA expression levels modified by tobacco use in women with lung adenocarcinoma. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oshlack A., Robinson M.D., Young M.D. From RNA-seq reads to differential expression results. Genome Biol. 2010;11:220. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-12-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pertea M., et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:290–295. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Picard M., Scott-Boyer M.P., Bodein A., Perin O., Droit A. Integration strategies of multi-omics data for machine learning analysis. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021;19:3735–3746. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2021.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pitot H.C., Dragan Y.P. Facts and theories concerning the mechanisms of carcinogenesis. FASEB J. 1991;5:2280–2286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Puisieux A., Brabletz T., Caramel J. Oncogenic roles of EMT-inducing transcription factors. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:488–494. doi: 10.1038/ncb2976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ponziani F.R., Giannini E.G., Lai Q. Machine learning and biomarkers in hepatocellular carcinoma: the future is now. Liver Cancer Int. 2022 doi: 10.1002/lci2.67. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramskold D., Wang E.T., Burge C.B., Sandberg R. An abundance of ubiquitously expressed genes revealed by tissue transcriptome sequence data. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rignall B., Braeuning A., Buchmann A., Schwarz M. Tumor formation in liver of conditional beta-catenin-deficient mice exposed to a diethylnitrosamine/phenobarbital tumor promotion regimen. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:52–57. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rumgay H., et al. Global burden of primary liver cancer in 2020 and predictions to 2040. J Hepatol. 2022;77:1598–1606. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saito A., et al. Prediction of early recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after resection using digital pathology images assessed by machine learning. Mod Pathol. 2021;34:417–425. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-00671-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Santos M.S., Abreu P.H., Garcia-Laencina P.J., Simao A., Carvalho A. A new cluster-based oversampling method for improving survival prediction of hepatocellular carcinoma patients. J Biomed Inf. 2015;58:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2015.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Santos N.P., et al. Cytokeratin 7/19 expression in N-diethylnitrosamine-induced mouse hepatocellular lesions: implications for histogenesis. Int J Exp Pathol. 2014;95:191–198. doi: 10.1111/iep.12082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sato M., et al. Machine-learning approach for the development of a novel predictive model for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2019;9:7704. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44022-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schadt E.E. Molecular networks as sensors and drivers of common human diseases. Nature. 2009;461:218–223. doi: 10.1038/nature08454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schneider C., et al. Adaptive immunity suppresses formation and progression of diethylnitrosamine-induced liver cancer. Gut. 2012;61:1733–1743. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sung H., et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thuy le T.T., et al. Promotion of liver and lung tumorigenesis in DEN-treated cytoglobin-deficient mice. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:1050–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tiwari N., Gheldof A., Tatari M., Christofori G. EMT as the ultimate survival mechanism of cancer cells. Semin Cancer Biol. 2012;22:194–207. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang W., et al. Artificial intelligence-assisted diagnosis of hematologic diseases based on bone marrow smears using deep neural networks. Comput Methods Prog Biomed. 2023;231 doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2023.107343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yan H.X., et al. DNA damage-induced sustained p53 activation contributes to inflammation-associated hepatocarcinogenesis in rats. Oncogene. 2013;32:4565–4571. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang B., et al. Dynamic network biomarker indicates pulmonary metastasis at the tipping point of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2018;9:678. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03024-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang C.S., Tu Y.Y., Koop D.R., Coon M.J. Metabolism of nitrosamines by purified rabbit liver cytochrome P-450 isozymes. Cancer Res. 1985;45:1140–1145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yao J.T., et al. Over-expression of CircRNA_100876 in non-small cell lung cancer and its prognostic value. Pathol Res Pr. 2017;213:453–456. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2017.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang H., et al. Differential diagnosis of hematologic and solid tumors using targeted transcriptome and artificial intelligence. Am J Pathol. 2023;193:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2022.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material