Abstract

Several studies were focused on the genetic ability to taste the bitter compound 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP) to assess the inter-individual taste variability in humans, and its effect on food predilections, nutrition, and health. PROP taste sensitivity and that of other chemical molecules throughout the body are mediated by the bitter receptor TAS2R38, and their variability is significantly associated with TAS2R38 genetic variants. We recently automatically identified PROP phenotypes with high precision using Machine Learning (mL). Here we have used Supervised Learning (SL) algorithms to automatically identify TAS2R38 genotypes by using the biological features of eighty-four participants. The catBoost algorithm was the best-suited model for the automatic discrimination of the genotypes. It allowed us to automatically predict the identification of genotypes and precisely define the effectiveness and impact of each feature. The ratings of perceived intensity for PROP solutions (0.32 and 0.032 mM) and medium taster (MT) category were the most important features in training the model and understanding the difference between genotypes. Our findings suggest that SL may represent a trustworthy and objective tool for identifying TAS2R38 variants which, reducing the costs and times of molecular analysis, can find wide application in taste physiology and medicine studies.

Keywords: TAS2R38, Individual taste variability, Taste intensity Ratings, PROP taster categories, Supervised Learning (SL)

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Supervised Learning finds TAS2R38 genotypes in automatic, scalable and real-time way.

-

•

CatBoost was the best algorithm for the discrimination of the TAS2R38 genotypes.

-

•

PROP (0.32 mM) intensity rating was the most important feature in training the model.

-

•

High and low PROP ratings pushed the model toward PAV/PAV and AVI/AVI predictions.

-

•

Medium taster category had a high impact to make a prediction of PAV/AVI genotype.

1. Introduction

Taste receptors can detect chemical molecules and provide important knowledge on food nature and quality, but also on many health-related concerns [1], [2]. Based on their function in the tongue taste cells, taste receptors can distinguish five primary qualities: salt, sweet, bitter, sour, and umami [3]. However, they can also sense chemical molecules in numerous extra-oral tissues where they take part in numerous physiological processes [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]. Therefore, disorders or changes in the expression or sensitivity of these taste receptors can affect physiological functions [5], [11] and determine inter-individual differences in taste perception which are related to eating behavior, nutritional status, and health [1], [2], [12], [13], [14].

Regarding bitter taste perception, it is mediated by about 25 bitter taste receptors (TAS2Rs). In the oral cavity, they act by preventing the consumption of potentially toxic substances, and across the body, they mediate a variety of non-tasting functions and disorders, which have been associated with their genetic variants [9]. Among TAS2Rs, the most extensively studied is TAS2R38, which controls the detection of the bitter chemical 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP), reported as a stimulus marker for inter-individual differences of taste perception of various stimuli (including other bitter chemicals [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], sweet stimuli [21], sour compounds [22], umami taste [23], etc.) and food preferences, with relationships to nutritional status or other non-tasting physiological mechanisms [1], [2], [9], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32]). The three PROP taster categories (PROP non-taster (NT), medium taster (MT), and super-taster (ST)) can be used to classify humans [1], [28], [29], [30], [31] based on their sensitivity determined by using numerous psychophysical approaches [1], [16], [28], [29], [30], [31], [33], [34].

The allelic diversity in the TAS2R38 gene gives rise to two haplotypes: the AVI form, which has little or no affinity for the stimulus, and the PAV which has a high affinity for PROP. It has been assumed that STs are homozygous for the PAV variant, MTs are heterozygous and NTs almost always are AVI homozygous [35]. However, several studies have shown an extensive genotypic overlap between the STs and MTs [36], [37], and that the presence of two PAV variants (compared to one) confers no further advantage for perceiving more PROP bitterness [32]. Therefore, other factors must be involved to explain the inter-individual differences in the PROP taste ability [1], [32], [38], [39]. Among these are the density and activity of the fungiform papillae [40]. STs exhibit a higher density of fungiform taste papilla [30], [41], [42], [43] and a higher level of functional activity [40], as compared to MTs and NTs and this can explain why they are more sensitive to oral stimuli that are not mediated by the bitter TAS2R38 receptor [15], [17], [19], [21], [22], [23], [28], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51]. These differences have found a mechanistic explanation in a polymorphism of the gene that codes for the salivary protein Gustin described as a taste bud trophic factor [40], [52], [53]. Taste sensitivity has also been linked to various other varying genes [54], [55] or specific salivary amino acids and/or proteins [34], [56], [57]. Gender and age have long been known to influence chemosensory perceptions [58], [59]. In addition, great attention has been given to relationships between PROP genotype or phenotype and longevity [60], age [61], [62], and several health parameters such as antioxidant status [63], body mass index (BMI) [37], [64], [65], [66], [67], metabolic changes [68], [69], smoking status [70], [71], [72], alcohol consumption [45], immune response [73], respiratory infections [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], taste disturbs [81], risk of colonic neoplasm [82], [83], [84], neurodegenerative disorders [85], [86] and microbiota [87], [88].

Ry recognize, with high precision, the PROP phenotype, by using Machine Learning (ML) [89]. Given the implications that the genetic variants of TAS2R38 bitter receptor have in tasting and non-tasting functions and disorders [2], [9], [36], [38], [52], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [83], [84], [85], we addressed the issue of assessing the efficacy of ML classifiers in the automatic and highly accurate distinction between TAS2R38 genotypes, by exploiting biological features of participants which were used as predictive variables in the data set. In addition, the proposed approach was used to know the significance and influence of each biological feature, thus allowing its validation for the TAS2R38 genotype determination.

We used the Supervised Learning (SL) classifiers to learn from a structured set of data and create automatic classification models to evaluate the differences among participants in order to obtain a highly precise prediction on the TAS2R38 genotypes of the participants. The biological (sensory, genetic, morphological, clinical, and demographic) features used as predictive variables (numerical and categorial) are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sensory, genetic, morphological, clinical, and demographic features of participants presented in the data model as predictive variables.

| Features | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | Numerical | Min: 17.09; Max: 33.17 Mean: 21.85; SD: 3.27 |

| BMI status | Categorical | NW: 58 OW: 16 UW: 10 |

| Age | Numerical | Min: 18; Max: 40 Mean: 25.07; SD: 4.22 |

| Gender | Categorical | Women: 49 Men: 35 |

| Smoking Status | Categorical | Smokers: 19 Non-Smokers: 65 |

| PROP (0.032 mM) intensity ratings | Numerical | Min: 0; Max: 50 Mean: 4.65; SD: 7.74 |

| PROP (0.32 mM) intensity ratings | Numerical | Min: 0; Max: 90 Mean: 30.35; SD: 22.24 |

| PROP (3.2 mM) intensity ratings | Numerical | Min: 1; Max: 100 Mean: 59.74; SD: 26.48 |

| NaCl (0.01 M) intensity ratings | Numerical | Min: 0; Max: 30 Mean: 4.26; SD: 6.20 |

| NaCl (0.1 M) intensity ratings | Numerical | Min: 0; Max: 90 Mean: 29.91; SD: 18.13 |

| NaCl (1 M) intensity ratings | Numerical | Min: 18; Max: 100 Mean: 62.20; SD: 22,21 |

| PROP Disk (50 mM) intensity ratings | Numerical | Min: 0; Max: 85 Mean: 24.60; SD: 18.28 |

| NaCl Disk (1 M) intensity ratings | Numerical | Min: 0; Max: 100 Mean: 44.13; SD: 26.47 |

| PROP_taster status | Categorical | ST: 16 MT: 51 NT: 17 |

| Sweet scores | Numerical | Min: 1; Max: 4 Mean: 3.42; SD: 0,66 |

| Sour scores | Numerical | Min: 0; Max: 4 Mean: 2.38; SD: 0.94 |

| Salty scores | Numerical | Min: 1; Max: 4 Mean: 3.57; SD: 0.71 |

| Bitter scores | Numerical | Min: 0; Max: 4 Mean: 3.21; SD: 1.05 |

| Umami scores | Numerical | Min: 0; Max: 4 Mean: 1.32; SD: 1.50 |

| TST scores | Numerical | Min: 7; Max: 19 Mean: 12.79; SD: 2 |

| Overall TST scores | Numerical | Min: 7; Max: 19 Mean: 13.91; SD: 2.86 |

| Taste sensitivity status | Categorical | Normogeusic: 90.5% Hypogeusic: 9.5% |

| TAS2R38 genotypes | Categorical | AVI/AVI: 21 PAV/AVI: 43 PAV/PAV: 20 |

| Fungiform papilla density | Numerical | Min: 3.53; Max: 87.28 Mean: 30.63; SD: 14.47 |

Normal weight, NW; Overweight, OW; Underweight; UW. Non-taster, NT; medium taster, MT; Super-taster ST; Taste Strip Test scores, TST scores; Taste Strip Test and the Umami Test scores, Overall TST scores.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

Eighty-four participants (35 men and 49 women) were enrolled through traditional practices at the University of Cagliari, Italy. They were Caucasian and their age ranged from 18 to 40 years, with a mean of 25.07 ± 0.507. Participants were classified as non-smokers (n = 65) and smokers (n = 19) and as underweight (n = 10, BMI below 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (n = 58, BMI from 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2) and overweight (n = 16, BMI from 25.0 to 29.9 kg/m2). Exclusion criteria: use of medications affecting taste sensitivity (e.g., antihistamines, steroids, and certain antidepressants), major systemic diseases, food allergies, pregnancy and lactation. All participants signed a consent form before being accepted into the study. The study was authorized by the University Hospital of Cagliari's Ethical Committee and carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki's principles (protocol code: 451/09; date of approval: 5/2016).

2.2. Experimental procedure

The following biological data, which have been associated with the PROP phenotype and/or genotype [1], [2], [25], [29], [30], [31], [33], [36], [37], [38], [40], [64], [65], [70], [71], [72], were collected from each participant over the course of two sessions on consecutive days: PROP and NaCl intensity ratings, scores for the five tastes, the density of fungiform papillae, BMI, age, TAS2R38 genotypes, taste sensitivity status, gender and smoking, and BMI status.

Before starting the sensory analysis session, participants were asked to refrain from eating, drinking (excluding water), using dental care products or chewing gum for at least 2 h. They had to adapt to the environmental conditions (23–24 °C; 40–50% relative humidity) of the test room for 15 min. To prevent taste sensitivity alterations caused by the estrogen phase, women were assessed on the sixth or seventh day of menstrual cycle [90].

In the first visit, measurements of height (m) and weight (kg) were taken to determined BMI (kg/m2). 2 mL of whole saliva samples were taken and were kept at − 80 °C until the molecular analyses were finalized. After a recovery period of 1 h, the ratings of the perceived taste intensity for NaCl and PROP were taken by using two approved psychophysical techniques (the Three-solution Test [29] and the Impregnated Paper Screening Test [31]).

On the second day, scores for the five basic taste qualities (salty, sweet, bitter, sour and umami) were assessed by using the Taste Strip Tests (TST and umami test, Burghart Messtechnik, Wedel, Germany) [91], [92], [93]. Fungiform papilla density was also determined.

Before each stimulation, each participant rinsed his/her mouth with spring water. The day before the session, the solutions were prepared, stored in the refrigerator, and then provided to the participant at room temperature.

2.3. Taste assessments

2.3.1. PROP and NaCl intensity ratings and PROP taster status classification

The ratings of the perceived intensity for PROP and NaCl were collected from each participant by two psychophysical methods (Three-Solution Test, [29] and the Impregnated Paper Screening Test [31]) which have been used in many studies [33], [52], [53], [57] and strongly correlate with the activation of peripheral taste system [94], [95], [96]. These two methods allowed to classify participants by their PROP taster status.

According to Tepper et al. [29], the Three-solution test was used as a first step to assess participants. Briefly, the ratings of perceived intensity for three solutions of NaCl (NaCl; 0.01, 0.1, 1.0 mol/L) (Sigma-Aldrich, Milan, Italy) and PROP (0.032, 0.32, and 3.2 mmol/L) (Sigma-Aldrich) at suprathreshold concentration were determined by applying the Labeled Magnitude Scale (LMS) [97]. Concentrations (10 mL samples) were presented in random order with an interstimulus interval of 60 s. Participants who rated PROP lower than NaCl were categorized as NT, those who gave corresponding ratings were categorized as MT and those who gave higher ratings to PROP than to NaCl were categorized as ST. After a 1-h period of recovery, the appropriate belonging of a participant to a certain PROP taster group was confirmed by using the Impregnated paper screening test [31]. Thus, only participants categorized as alike were included in the other tests. In this second test, the perceived intensity ratings were collected using two paper disks impregnated with PROP (50 mmol/L) and NaCl (1.0 mol/L) that were applied on the tip of the tongue for 30 s according to Zhao et al. [31]. Participants who rated the PROP disk higher than 67 mm in LMS were categorized as ST, those who rated the PROP disk lower than 15 mm were categorized as NT, and the others were categorized as MT [31]. To validate the ST classification of participants who could overestimate the oral stimuli [1] by using LMS, the general labeled magnitude scale (gLMS) [98], which broadens the top anchor of the scale to encompass any sensation, was also used to assess ST participants.

Based on their taster group assignments, 17 participants (6 M, 11 F) were NT, 16 were ST (5 M, 11 F) and 51 were MT (24 M, 27 F).

2.3.2. Taste sensitivity for the five basic qualities

Scores for the five taste qualities were collected by The Taste Strip Test and the Umami Test (TST, Burghart Messtechnik, Wedel, Germany) [91], [92], [93], which consist of the identification of taste qualities presented by filter paper strips impregnated with four concentrations of each stimulus (0.016, 0.04, 0.1, or 0.25 g/mL of NaCl; 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, or 0.4 g/mL of sucrose; 0.05, 0.09, 0.165, or 0.3 g/mL of citric acid; 0.0004, 0.0009, 0.0024, or 0.006 g/mL of quinine hydrochloride and 0.25, 0.1, 0.04, 0.016 g/mL of monosodium glutamate). Each correct identification was rated 1, therefore the maximum score for each quality was 4, 16 for the four tastes (TST), and 20 when umami was incorporated (Overall TST). A participant was considered hypogeusic or ageusic if he/she scored< 9, normogeusic if he/she scored ≥ 9 according to Landis et al. [91]. The qualities were presented in a pseudo-randomized sequence and concentrations were tested in ascending order.

2.4. Papilla density

The fungiform papillae were recognized according to Melis et al. [40]. The tip of the tongue dorsal anterior surface was stained by positioning (for 5 s) a disk (6 mm dia) of filter paper impregnated with a blue food dye (E133, Modecor Italiana, Italy). Three to ten photographs of the tongue surface were taken for each participant by using a Canon EOS D400 (10 megapixels) camera with an EFS 55–250 mm lens. In the stained area of the tongue surface, the fungiform papillae were identified by their very light staining and mushroom shape [99]. Their number in each photograph was determined by the consensus of five observers and the density/cm2 was determined for each participant.

2.5. Genetic analysis

Using the QIAamp® DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN S.r.l., Milan, Italy) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions, DNA was extracted from saliva samples. Using an Agilent Cary 60 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer, readings at an optical density of 260 nm were used to determine the content of pure DNA (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA, USA).

Participants were genotyped for three single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), (rs713598, rs1726866, and rs10246939) of the TAS2R38 gene, which caused three amino acid substitutions (Pro49Ala, Ala262Val and Val296Ile). Molecular analyses were performed by using TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assay (C_8876467_10 assay for the rs713598; C_9506827_10 assay for the rs1726866 and C_9506826_10 assay for the rs10246939) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Applied Biosystems by Life Technologies Milan Italy Europe BV). Each reaction included three positive controls, two negative controls and two replicates.

Based on molecular analyses of the TAS2R38 locus, 20 participants were PAV/PAV homozygous, 43 were PAV/AVI heterozygous, and 21 were AVI/AVI homozygous. Participants with rare haplotypes were not included into the study to reduce confounding factors in taste sensitivity [100].

2.6. Supervised learning (SL)

The automatic recognition of the TAS2R38 genotype of participants was carried out with SL algorithms capable of distinguishing the three genotypes (PAV/PAV, PAV/AVI, and AVI/AVI), by using the participants’ features presented in the data model as predictive variables, as already performed by Naciri et al. with the aim of identifying PROP taster categories [89].

The following algorithms were used: Logistic Regression, Decision Tree, Random Forest, K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN), and CatBoost classifier according to Naciri et al. [89]. During training, the algorithms search for the correlation of the features with the TAS2R38 genotype groups, then they take new unknown inputs and assign them to the appropriate category. Specifically, Logistic Regression is an algorithm that classifies data by considering outcome variables at the extremes and tries to make a logarithmic line between them [101]. The decision tree is an acyclic graph [102]: in each branching node of the tree, a specific feature is examined. When the value of the feature is below a certain threshold, the left branch is followed, otherwise, the right branch is followed. When the node of the leaf is reached, the decision is made about the class to which the example belongs. The random forest algorithm builds multiple decision trees on data samples, then makes the prediction from each of them and finally selects the best solution [103]. It is a better method than a single decision tree because it reduces the over-fitting by averaging the result. Contrary to other algorithms that allow to discard training data after the model is built, KNN keeps all training data in memory [104]. When a new sample needs to be classified, the KNN algorithm finds all the closest training samples and returns the majority label. CatBoost, is an algorithm for gradient boosting on decision trees, excels at handling small datasets, and produces the best results when a dataset contains many categorical features. Furthermore, it is well known that CatBoost can be used in a variety of settings and for a wide range of issues [105], [106], [107].

The evaluation of algorithms is performed by metrics, such as precision (1), accuracy (2), recall (3), F1-score (4), Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, and Area Under Curve (AUC) [89].

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

The ROC curve represents a classifier's diagnostic capability and is constructed by plotting the true positive rate (TPR) as a function of the false positive rate (FPR) at diverse threshold settings. The AUC shows which of the used models best predicts a category. AUC is evaluated by the micro-average that combines the contributions of all categories to compute the average metric and the macro-average that computes the metric independently for each group and then makes the average. The first is preferable in the presence of imbalanced categories.

The following data processing operations, which are an essential phase in the running of a SL project, were performed.

-

1.

For each feature the distribution in each genotype group and the correlations between each feature and the target were determined (Figure S1). It is important to note that all numerical features present a normal distribution and that the ratings obtained with the two tests were strongly correlated with each other (r > 0.43; p < 0.001, Pearson’s (r) coefficient analysis), as well as papilla density and rating of PROP paper disk (r = 0.34; p = 0.0016) and the scores of the TST and the overall TST were strictly correlated with the scores of each taster quality (r > 0.43; p < 0.001).

-

2.

After analysis of the dataset, the handling of missing values was performed: the mean values of the column were used to approximate the BMI value in six rows where it was missing.

-

3.

The dataset content was converted into a language that an algorithm can understand. This included: a) One Hot Encoding and Ordinal Encoding which encodes categorical data into numerical data; b) normalization of the numerical data by converting the real range of numerical values into values between 0 and 1; c) the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE)[108] which allows the balancing of the number of observations among classes. This operation was necessary to prevent the algorithm from learning better from the majority class with respect from the minority ones. In the training process, after SMOTE the 31 PAV/AVI, 14 AVI/AVI, and 13 PAV/PAV observations became 31 observations in each genotype class.

In order to solve problems of overfitting or underfitting that may occur in the training of SL algorithms, we removed all features not significantly correlated with the TAS2R38 genotype groups and increased the regularization parameters. In addition, we used 3-fold Cross-Validation [109], that mixes and splits data into two groups: one group of data (67% of data) as the training data and the other (33% of data) as the test data. This process was done for three times with distinct subsets of data.

The overall behavior of our classifiers was evaluated by the automatic optimization of their hyperparameters by Grid Search Algorithm [110], [111]. Subsequently, the models were evaluated by means of the evaluation metrics described above.

In addition, we used the Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) [112], which allows to interpret the SL model outputs by linking feature importance with feature effects. It returns a SHAP summary plot that connects the significance of the features to their impacts. Each point on the chart is a SHAP value that allows to understand the contribution of an input feature to that single prediction. In addition to indicating feature relevance, SHAP values also indicate whether a feature has a favorable or unfavorable influence on predictions.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Fisher’s Exact Test was used to compare differences in the distribution of PROP taster, gender, and smoker groups according to TAS2R38 genotypes. One-way analysis (ANOVA) was used to compare differences in BMI, age, papilla density, intensity ratings for PROP or NaCl, and taste scores according to TAS2R38 genotypes (AVI/AVI, PAV/AVI, and PAV/PAV). Statistical analyses were conducted using STATISTICA for WINDOWS (version 7; StatSoft Inc, Tulsa, OK, USA). P values< 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

Mean values± SE or the participant distribution according to TAS2R38 locus regarding the sensory, genetic, morphological, clinical, and demographic features are shown in Table 2. One-way ANOVA revealed that the fungiform papillae density, as well as the intensity ratings for PROP (0.032, 0.32, 3.2 and 50 mM), varies with TAS2R38 genotypes (F[2], [81] = 6.269; p = 0.003; F[2], [81] = 8.875; p = 0.0003; F[2], [81] = 27.463; p < 0.00001; F[2], [81] = 18.025; p < 0.00001; F[2], [81] = 16.707; p < 0.00001). Specifically, participants with the AVI/AVI genotype showed lower values of papilla density and gave lower intensity ratings for PROP (0.32, 3.2 and 50 mM) than PAV/PAV or PAV/AVI participants (p < 0.008; Fisher LDS test), who showed no difference from each other (p > 0.05). Instead, the intensity ratings for PROP (0.032, mM) were higher for PAV/PAV participants than for PAV/AVI and AVI/AVI participants (p < 0.009; Fisher LDS test). In addition, the PROP taster status of participants was associated with TAS2R38 SNPs based on ST, MT and NT participant distribution in each genotype group (χ2 = 49.979; p < 0.0001; Fisher’s test). Post hoc comparisons distinguished all groups from one another (χ2 > 12.24; p < 0.0022; Fisher's test). NTs were more frequent among participants with genotype AVI/AVI (88.23%), MTs were more frequent among participants with the genotype PAV/AVI (68.63%), while STs were more frequent in PAV/PAV participants (62.5%). No difference related to TAS2R38 locus in age, BMI, gender, smoking status, intensity ratings for NaCl or taste scores was found (p > 0.05).

Table 2.

Sensory, genetic, morphological, clinical and demographic features of participants according to TAS2R38 genotypes.

| Features |

PAV/PAV (n= 20) |

PAV/AVI (n= 43) |

AVI/AVI (n= 21) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 26.00 ± 0.93 | 24.14 ± 0.64 | 26.09 ± 0.91 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.99 ± 0.74 | 21.91 ± 0.51 | 21.49 ± 0.72 |

| Papilla density/cm2 | 36.74 ± 3.05a | 31.94 ± 2.08a | 22.14 ± 2.98b |

| Male/female (n) | 10/10 | 16/27 | 9/12 |

| Smokers/non (n) | 2/18 | 14/29 | 3/18 |

| Intensity ratings | |||

| PROP (0.032 mM) | 10.25 ± 1.59a | 3.64 ± 1.08b | 1.4 ± 1.55b |

| PROP (0.32 mM) | 42.95 ± 3.98a | 36.16 ± 2.65a | 6.47 ± 3.79b |

| PROP (3.2 mM) | 74.75 ± 4.99a | 64.63 ± 3.40a | 35.44 ± 4.87b |

| NaCl (0.01 M) | 3.59 ± 1.40 | 4.12 ± 0.95 | 5.19 ± 1.36 |

| NaCl (0.1 M) | 31.71 ± 4.09 | 29.36 ± 2.79 | 29.33 ± 3.99 |

| NaCl (1 M) | 59.10 ± 5.01 | 63.81 ± 3.41 | 61.86 ± 4.89 |

| PROP disk (50 mM) | 56.60 ± 5.04a | 50.16 ± 3.44a | 19.91 ± 4.92b |

| NaCl disk (1 M) | 21.35 ± 4.12 | 25.24 ± 2.81 | 26.40 ± 4.02 |

| PROP taster status ST/MT/NT (n) |

10/10/0x | 6/35/2 y | 0/6/15z |

| Taste scores | |||

| Sweet | 3.30 ± 0.15 | 3.53 ± 0.10 | 3.33 ± 0.14 |

| Salty | 3.45 ± 0.16 | 3.65 ± 0.11 | 3.52 ± 0.16 |

| Sour | 2.25 ± 0.21 | 2.42 ± 0.14 | 2.43 ± 0.21 |

| Bitter | 3.25 ± 0.24 | 3.23 ± 0.16 | 3.14 ± 0.23 |

| Umami | 0.80 ± 0.33 | 1.58 ± 0.23 | 1.28 ± 0.33 |

| TST | 12.40 ± 0.45 | 13.07 ± 0.31 | 12.62 ± 0.44 |

| Overall TST | 13.05 ± 0.64 | 14.42 ± 0.43 | 13.71 ± 0.62 |

Values are either means± SE or the total number of participants. Significant differences of mean values are shown with a, b and c letters (p ≤ 0.009; LSD test following to one-way ANOVA), while differences in frequency distribution are shown with x, y and z letters (p < 0.0022; Fisher's method).

The best hyperparameters for each model were evaluated by the metrics to estimate the training and performance of the SL algorithms. The high values of precision (88%), recall (83%) and F1-score (82%) revealed that the CatBoost algorithm allowed to achieve the objective discrimination of TAS2R38 genotypes (Table 3). Since our data are unbalanced, the accuracy results are not shown as they are meaningless. The Logistic Regression, Decision Tree, Random Forest, and KNN algorithms also achieved the goal, but with lower values of evaluation metrics than the CatBoost.

Table 3.

Evaluation metrics for each classifier model.

| Classifiers | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| KNN | 55% | 55% | 55% |

| Decision tree | 61% | 59% | 59% |

| Logistic Regression | 73% | 72% | 71% |

| Random Forest | 80% | 79% | 79% |

| CatBoost | 88% | 83% | 82% |

The ROC curve and AUC of the three genotypes of TAS2R38 (PAV/PAV, PAV/AVI and AVI/AVI) obtained by the CatBoost model are shown in Fig. 1. The ROC curve showed that the corrected predictions made by the model were 96%, 78%, and 82%, for the three genotypes (AVI/AVI, PAV/AVI, and PAV/PAV, respectively). Besides, the AUC showed that the micro-average, which represents the average margin of error was 90%. The macro-average, which represents the median percentage value of all genotype groups, was 87%, a value not significant because of the unbalanced data.

Fig. 1.

The ROC curve and the AUC determined with the CatBoost model. The ROC curve represents the percentage of error for each genotype of the TAS2R38 gene. The line in black denotes the correct predictions of the AVI/AVI genotype, the line in light blue denotes the correct predictions of the PAV/AVI genotype and the line in yellow denotes the correct predictions of the PAV/PAV genotype. The dashed lines, in pink and blue, denote the value of the micro and macro-average, respectively.

Fig. 2 shows an alluvial plot which represents the variations in network structure over subject of TAS2R38 groups recognized by different methods (TAS2R38 genotyping and SL discrimination). This diagram graphically shows that 95.45% of subjects who had genotype AVI/AVI (n = 22) were allocated to the same genotype (n = 21) by SL discrimination, while 4.55% were allocated to PAV/AVI genotype (n = 1); 90.91% of subjects who had genotype PAV/AVI (n = 44) were allocated to the same genotype (n = 40) by SL discrimination, while 9.09% were allocated to AVI/AVI genotype (n = 2) or PAV/PAV genotype (n = 2); 76.19% of subjects who had genotype PAV/PAV (n = 21) were allocated to the same genotype (n = 16) by SL discrimination, while 23.81% were allocated to PAV/AVI genotype (n = 5) by SL discrimination.

Fig. 2.

The alluvial plot graphically shows the variations in network structure over subject of TAS2R38 groups recognized by different methods (TAS2R38 genotyping and SL discrimination). The magnitude of the components present in the two blocks connected by a stream is represented by the height of the stream. The (n) number of subjects for each cluster is shown by a number.

The CatBoost classifier established the order of importance of the features in facilitating the learning of the model to detect the three TAS2R38 genotypes (Fig. 3). Specifically, the figure shows the importance of features for training the PAV/PAV genotype, the AVI/AVI genotype and the PAV/AVI genotype. The intensity rating for the PROP solution (0.32 mM) was the most significant feature in the training model. This feature was followed in order of importance by ratings of intensity for PROP solution (0.032 mM) and PROP paper disk (50 mM), and MT category, ratings of intensity for NaCl solution (0.01 M) and NaCl paper disk (1 M), and age. It is intriguing to observe that the score for umami was the more important in facilitating the learning of the model (ninth significant feature) among the scores for other taste qualities. Also, papilla density was a significant feature (eleventh in order of importance).

Fig. 3.

Importance of the features in training the CatBoost classifier. The X-axis denotes the order of importance of the features to discriminate each TAS2R38 genotype, while the average impact on the model output is represented in the Y-axis.

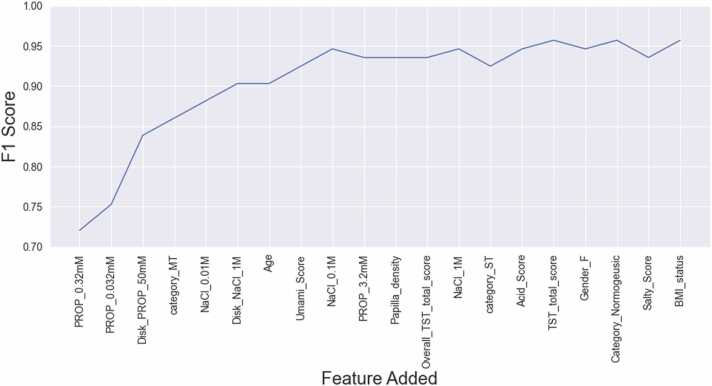

Fig. 4 shows that by including the first three features (the rating of perceived intensity for PROP solutions (0.32 mM), PROP solutions (0.032 mM) and PROP paper disk (50 mM)), the F1-Score rises to a value of 0.84, then reaches 0.90 by including the successive three features (MT category, intensity rating for NaCl solution (0.01 M) and NaCl paper disk (1 M)) and reaches 0.95 after adding age, umami score and intensity rating for NaCl solution (0.1 M).

Fig. 4.

The learning progress curve of the CatBoost model when the features are included one by one based on their importance in learning the model.

The use of the SHAP algorithm provided an overview of the importance of features and how they affect the model prediction. The SHAP summary plot showing the linking between the importance of features and the effects of features for PAV/PAV genotype is shown in Fig. 5. Specifically, the plot highlights that the rating of the perceived intensity for PROP solutions (0.32 mM) was the most important feature for the model and high and medium estimated values (red and violet, respectively) were strongly and positively correlated with PAV/PAV genotype. The rating of perceived intensity for the PROP solutions (0.032 mM) was the second in order importance for the PAV/PAV genotype and high and medium estimated values (red and violet, respectively) had a high impact to make a PAV/PAV genotype prediction. Low values (blue) of these two features mostly pushed the model prediction toward other genotypes. The ratings of perceived intensity for NaCl paper disk (1 M) and NaCl solution (0.01 M) were the third and fourth significant features for PAV/PAV genotype and low estimated values (blue) positively correlated with it, while high and medium estimated values (red and violet) pushed the prediction of the model towards other genotypes. The rating of intensity for paper disk (50 mM) was the fifth significant feature and high estimated values positively correlated with a PAV/PAV genotype prediction. The salty score was the more important (sixth in order of importance) among those given to taste qualities, and low estimated values positively correlated with PAV/PAV genotype, while high values pushed the model towards the other genotypes. The classification as normogeusic or MT were the seventh and eighth important features and correlated negatively and moderately with this genotype, while the ST category was less important, but positively correlated with PAV/PAV genotype.

Fig. 5.

SHAP summary plot of PAV/PAV genotype. The descending order of importance of the features (from the most significant at the top to the less significant at the bottom) is shown on the left of the Y-axis; the impact on the model output (SHAP value) is shown on the X-axis. The color in the line at right of the graph represents the feature value: high value (red color), medium value (violet color) and low value (blue color).

SHAP algorithm provided an overview of the importance of features and how they affect a PAV/AVI genotype prediction (Fig. 6). Also in the case of this genotype, the rating of intensity for PROP solutions (0.32 mM) was the most significant feature for the model. High and medium values (red and violet, respectively) were positively and strongly correlated with this genotype, low values (blue) however, shifted the prediction in favor of the other genotypes. Interestingly, the classification of participants as MT, which was the second significant feature, had a high impact to make a prediction of PAV/AVI genotype, while age (third feature) correlated negatively. The intensity rating for the PROP solutions (0.032 mM) was the fourth feature for PAV/AVI genotype and low estimated values (blue) correlated moderately and negatively with this genotype. The rating of intensity for the PROP paper disk (50 mM) was the successive important feature. Medium estimate values pushed the model to predict PAV/AVI genotype, while low and high values were negatively correlated with it and pushed the model to make another prediction. The score for umami was the most important (sixth in importance order) among those for taste qualities, and high and medium estimated values (red and violet, respectively) were moderately and positively correlated with this genotype. Again, the classification of participants as normogeusic was a significant feature which positively and moderately correlated with this genotype.

Fig. 6.

SHAP summary plot of PAV/AVI genotype. The descending order of importance of the features (from the most significant at the top to the less significant at the bottom) is shown on the left of the Y-axis; the impact on the model output (SHAP value) is shown on the X-axis. The color in the line at right of the graph represents the feature value: high value (red color), medium value (violet color) and low value (blue color).

Fig. 7 shows the SHAP summary plot for the AVI/AVI genotype. Also in this case the rating of perceived intensity for PROP solutions (0.32 mM) was the most important feature for the model and low estimated values (blue) had a high impact to make an AVI/AVI genotype prediction. On the other hand, high and medium estimated values of this feature (red and violet) strongly pushed the prediction of the model towards the other genotypes. The PROP solution (0.032 mM) intensity rating was the second feature for this genotype and low estimated values (blue) were positively and moderately correlated with the AVI/AVI genotype. The intensity ratings for NaCl paper disk (1 M) and NaCl solution (0.01 M) were the third and fifth features in order of importance and high and medium estimated values (red and violet, respectively) moderately pushed the model prediction towards AVI/AVI genotype. The classification of participants as MT, which was the fourth feature in order of importance, negatively impacted to make an AVI/AVI genotype prediction. The intensity rating for PROP solutions (3.2 mM) and PROP paper disk (50 mM) were significant features and low estimated values (blue) positively and moderately correlated with AVI/AVI genotype prediction, while high values pushed toward the other genotypes.

Fig. 7.

SHAP summary plot of AVI/AVI genotype. The descending order of importance of the features (from the most significant at the top to the less significant at the bottom) is shown on the left of the Y-axis; the impact on the model output (SHAP value) is shown on the X-axis. The color in the line at right of the graph represents the feature value: high value (red color), medium value (violet color) and low value (blue color).

4. Discussion

The primary aim of the present work was to develop an SL model capable of identifying automatically and with high precision the genetic variants of the TAS2R38 bitter receptor, given their importance in taste and health [2], [9], [36], [38], [52], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [83], [84], [85], [87]. Our approach, the effectiveness of which was verified, allowed us also to understand the importance and the impact of each feature to make a prediction, which was used as input in the data model.

The processing of the dataset and the analysis of correlations between features used as predictive variables, were critical phases to improve the dataset quality and obtain improved results. We found robust correlations between the intensity ratings for PROP and NaCl, between fungiform papillae density and PROP ratings or taste perception scores. PROP sensitivity greatly varied between TAS2R38 genotype groups: AVI/AVI participants perceived the PROP with little intensity, and PAV/PAV and PAV/AVI participants more intensely. We also found a robust link between TAS2R38 genotype groups and PROP taster status: STs never had AVI/AVI genotype and NTs never had PAV/PAV genotype. Instead, PAV/PAV and PAV/AVI genotypes could be determined in both MTs and STs.

For our purpose, we used five different algorithms (Logistic Regression, Decision Tree, Random Forest, KNN and the CatBoost classifier) and we compared their performance. The higher evaluation metric values obtained with the CatBoost algorithm, as compared to those of other models, indicated that this algorithm was the best model for the automatic identification of the TAS2R38 genotypes, even though the other algorithms did achieve the objective. The CatBoost algorithm allowed us to reach the goal with a high precision level (88%), recall (83%) and F1 score (82%). These results were also confirmed by the best ROC curve that showed a small error for the prediction of each genotype group (18% of error for the PAV/PAV genotype, 4% of error for the AVI/AVI genotype and 22% of error PAV/AVI genotype prediction), the best average margin of error (90%, micro-average) and the large overlap in the network structure over subject of TAS2R38 groups identified by molecular analysis and SL model. The best performance of the CatBoost model was not surprising as it is a method that handles small datasets containing a large number of categorical features better than other types [105], [106], [107].

The sensory, morphological, genetic, clinical and demographic features that we used as predictive variables in facilitating the model learning and understanding of the differences between the three TAS2R38 genotype groups were all parameters previously determined from participants, which have been associated with PROP genotype or phenotype in a large number of studies [1], [2], [25], [29], [30], [31], [33], [36], [37], [38], [40], [64], [65], [70], [71], [72]. Among them, the perceived intensity ratings for different amounts of PROP or NaCl were the most important ones. These measures have been commonly and reliably used for a long time in PROP phenotyping methods [29], [30], [31], [33], can be employed outside of traditional laboratories [29], [31], and can be easily and quickly administered to large groups of participants at a minimal cost and without creating discomfort. Our findings showed that, by using the CatBoost classifier, we were able to identify six of these measures as the most relevant in facilitating the model learning targeted at comprehending the differences between the three genotype groups. In order of importance, they were the intensity ratings for PROP solution (0.32 mM), for PROP solution (0.032 mM), for PROP paper disk (50 mM), MT category, the intensity ratings for NaCl solution (0.01 M) and NaCl paper disk (1 M). All were measures performed by the Impregnated Paper Screening Test [31] and the Three-Solution Test [29] which are the simplest and fastest psychophysical approaches for PROP phenotypic determination. This finding is relevant because it shows that the two tests provide the best features for training a model to make TAS2R38 genotype predictions for novel samples, further validating their use for PROP phenotyping and genotyping of participants. Furthermore, since PROP taste variability is mostly controlled by the genetic variants of the TAS2R38 receptor [36], [38], which mediate the detection of PROP [38], it is worth noting that the best four features in the training of the model to make predictions on TAS2R38 genotype of new samples were ratings of PROP bitterness. The analysis of the evaluation of the performance of the algorithm by including, one by one, the features in order of importance in learning the model seems to suggest that the ratings of PROP solutions (0.32 mM), PROP solutions (0.032 mM) and PROP paper disk (50 mM) may be considered the minimum threshold to predict the TAS2R38 genotype with an F1-score of 0.84 when there is a lack of resources for conducting molecular analysis.

The SHAP algorithm allowed us to correlate, with high precision, the feature relevance with its effect on the model's predictions for each TAS2R38 genotype group. Particularly, the SHAP findings very clearly showed the impact they had on making a prediction the PROP solution (0.32 mM) intensity rating, which was also the most important feature in the training the model, thus understanding the differences between the three genotype groups. Medium and high estimated values strongly pushed the model to make PAV/PAV and PAV/AVI predictions, while low values powerfully pushed toward AVI/AVI predictions. Similarly, high values of the PROP solution (0.32 mM) intensity rating strongly pushed the model to make PAV/PAV predictions, while low values pushed toward AVI/AVI predictions. These results indicate that the two PROP solutions at the lowest concentrations used in the Three-Solution Test [29] are the best predictors to identify the genotype of participants for the specific bitter receptor TAS2R38. Conversely, low values of the intensity ratings for NaCl paper disk (1 M) and NaCl solution (0.01 M), which are used as standard controls in the two tests, pushed the model towards PAV/PAV genotype predictions, while high and medium values pushed it toward the AVI/AVI one.

Our results showed that among the three PROP taster categories (ST, MT and NT), MT was the most critical feature (the fourth in importance order) for the training model to learn to discriminate among genotype groups and was effective in making precise PAV/AVI predictions. SHAP algorithm showed that the MT category had a strong impact to predict PAV/AVI genotype, while did not have a favorable impact to predict AVI/AVI or PAV/PAV genotypes. On the other hand, the SHAP technique showed that the ST category was less important, but positively and moderately pushed the model towards the PAV/PAV predictions. These findings are in line with previous research showing that having two PAV haplotypes, as opposed to one, does not add benefits for PROP bitter detection [32].

Our results also showed that age was a significant feature for the training model to learn to discriminate among the three genotype groups and low SHAP values moderately pushed the model to make PAV/AVI predictions, while high values moderately pushed toward AVI/AVI predictions. These results are consistent with data showing that the penetrance of the TAS2R38 gene (i.e. the degree to which environmental factors impact the phenotypic expression of a trait), varies with age [62]. Furthermore, gender was also a critical feature: females, who have been shown to have a stronger sensitivity to PROP [30], [66], [113], were more relevant in terms of training the model.

Also, the scores that the participants attributed to tastes (that are not specifically mediated by the TAS2R38 receptor) were significant features in facilitating the model learning to discriminate the TAS2R38 genotype groups, according to results showing associations between perception for the five tastes [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [96] and that for PROP. Umami was the most important quality, and its high values significantly impacted the model to make a PAV/AVI prediction. Future research may look at this aspect. On the other hand, the SHAP approach showed that low expected values of salty perception moderately pushed the model toward PAV/PAV predictions, while high values toward AVI/AVI predictions. This is consistent with the fact that in the psychophysical assessments used to classify participants for PROP taster status, NaCl is used as a standard reference, indicating that the perceived intensity rating for this stimulus is unaffected by the PROP phenotype of participants [29].

The fungiform papilla density was also a significant feature for the training model and was effective in making the specific PAV/PAV predictions. Indeed, the SHAP algorithm revealed that high estimated papilla density values are positively associated with PAV/PAV genotype, while low values pushed the model toward an AVI/AVI prediction. These results are in agreement with previous studies that found that STs, who predominantly have a PAV/PAV genotype, possess a larger number of fungiform papillae than PROP NTs, who had the AVI/AVI genotype [30], [33], [40], [41], [43], [114].

5. Conclusions

Our findings indicate that the proposed SL model is a reliable strategy for the identification of TAS2R38 genotypes with high precision by using fully automated processing and biological features of participants, which have been linked to PROP genotype or phenotype [1], [2], [25], [29], [30], [31], [33], [36], [37], [38], [40], [64], [65], [70], [71], [72]. The proposed model allowed us to obtain genotype identifications in an immediate and scalable manner. Furthermore, we were able to determine the feature importance and impact as predictive factors and this allowed us to distinguish precisely among PAV/PAV, PAV/AVI, and AVI/AVI genotypes and find correlations and parametric patterns. The intensity ratings for the two lower PROP concentrations of the Three-Solution Test [29] and the MT category were the features that best discriminated the three genotype groups. The planned SL model may be simply, conveniently, and efficiently applied to large groups of participants in studies ranging from taste physiology to medicine, thus decreasing the cost and time of molecular analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the University of Cagliari: “Fondi 5 per mille (Anno 2017)” and “Fondo Integrativo per la Ricerca (FIR 2019)”.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was authorized by the University Hospital of Cagliari's Ethical Committee and carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki's principles (protocol code is 451/09, data of approval 5/2016). Informed consent was obtained from all participants enrolled in the study.

Author contributions

Lala Chaimae Naciri: Conceptualization, methodology, software and formal analysis; Mariano Mastinu: methodology, formal analysis; Roberto Crnjar: data curation, review and editing; Iole Tomassini Barbarossa: Conceptualization, data curation, supervision, writing original draft preparation, review and editing, project administration, funding acquisition; Melania Melis: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, supervision, writing original draft preparation, review and editing, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Without the contributions of the participants, this study would not have been feasible, thus the authors thank them. We also thank Ilyas Chaoua for their supervising the SL method.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2023.01.029.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material.

.

References

- 1.Tepper B.J. Nutritional implications of genetic taste variation: the role of PROP sensitivity and other taste phenotypes. Annu Rev Nutr. 2008;28:367–388. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.28.061807.155458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tepper B.J., et al. Genetic sensitivity to the bitter taste of 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP) and its association with physiological mechanisms controlling body mass index (BMI) Nutrients. 2014;6:3363–3381. doi: 10.3390/nu6093363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaudhari N., Roper S.D. The cell biology of taste. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:285–296. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201003144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.M. Behrens, W. Meyerhof, Oral and extraoral bitter taste receptors, in: B.U. Meyerhof W., Joost HG. (Ed.), Sensory and Metabolic Control of Energy Balance. Results and Problems in Cell Differentiation, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011, pp. 87–99. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Depoortere I. Taste receptors of the gut: emerging roles in health and disease. Gut. 2014;63:179–190. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark A.A., Liggett S.B., Munger S.D. Extraoral bitter taste receptors as mediators of off-target drug effects. FASEB J. 2012;26:4827–4831. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-215087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laffitte A., Neiers F., Briand L. Functional roles of the sweet taste receptor in oral and extraoral tissues. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2014;17:379–385. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamamoto K., Ishimaru Y. Oral and extra-oral taste perception. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2013;24:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu P., Zhang C.H., Lifshitz L.M., ZhuGe R. Extraoral bitter taste receptors in health and disease. J Gen Physiol. 2017;149:181–197. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201611637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh N., Vrontakis M., Parkinson F., Chelikani P. Functional bitter taste receptors are expressed in brain cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;406:146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melis M., et al. Polymorphism rs1761667 in the CD36 gene is associated to changes in fatty acid metabolism and circulating endocannabinoid levels distinctively in normal weight and obese subjects. Front Physiol. 2017;8:1006. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.01006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melis M., et al. Changes of taste, smell and eating behavior in patients undergoing bariatric surgery: associations with PROP phenotypes and polymorphisms in the odorant-binding protein OBPIIa and CD36 receptor genes. Nutrients. 2021:13. doi: 10.3390/nu13010250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melis M., et al. Taste changes in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: associations with PROP phenotypes and polymorphisms in the salivary protein, gustin and CD36 receptor genes. Nutrients. 2020:12. doi: 10.3390/nu12020409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomassini Barbarossa I. Variant in a common odorant-binding protein gene is associated with bitter sensitivity in people. Behav Brain Res. 2017;329:200–204. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2017.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartoshuk L.M., Rifkin B., Marks L.E., Hooper J.E. Bitterness of KCl and benzoate: related to genetic status for sensitivity to PTC/PROP. Chem Senses. 1988;13:517–528. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartoshuk L.M. The biological basis of food perception and acceptance. Food Qual Prefer. 1993;4:21–32. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gent J., Bartoshuk L. Sweetness of sucrose, neohesperidin dihydrochalcone, and saccharin is related to genetic ability to taste the bitter substance 6-n-propylthiouracil. Chem Senses. 1983;7:265–272. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartoshuk L., et al. PROP supertasters and the perception of sweetness and bitterness. Chem Senses. 1992;17:594. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartoshuk L.M. Bitter taste of saccharin related to the genetic ability to taste the bitter substance 6-n-propylthiouracil. Science. 1979;205:934–935. doi: 10.1126/science.472717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartoshuk L.M., Rifkin B., Marks L.E., Bars P. Taste and aging. J Gerontol. 1986;41:51–57. doi: 10.1093/geronj/41.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeomans M.R., Tepper B.J., Rietzschel J., Prescott J. Human hedonic responses to sweetness: role of taste genetics and anatomy. Physiol Behav. 2007;91:264–273. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prescott J., Soo J., Campbell H., Roberts C. Responses of PROP taster groups to variations in sensory qualities within foods and beverages. Physiol Behav. 2004;82:459–469. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melis M., Tomassini I. Barbarossa, taste perception of sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami and changes due to l-arginine supplementation, as a function of genetic ability to taste 6-n-propylthiouracil. Nutrients. 2017;9:541–558. doi: 10.3390/nu9060541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayes J.E., Duffy V.B. Revisiting sugar-fat mixtures: sweetness and creaminess vary with phenotypic markers of oral sensation. Chem Senses. 2007;32:225–236. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjl050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tepper B.J., et al. Factors influencing the phenotypic characterization of the oral marker, PROP. Nutrients. 2017;9:1275. doi: 10.3390/nu9121275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tepper B.J., et al. Genetic variation in taste sensitivity to 6-n-propylthiouracil and its relationship to taste perception and food selection. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1170:126–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.03916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duffy V.B., Bartoshuk L.M. Food acceptance and genetic variation in taste. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100:647–655. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00191-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tepper B.J., Nurse R.J. PROP taster status is related to fat perception and preference. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;855:802–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tepper B.J., Christensen C.M., Cao J. Development of brief methods to classify individuals by PROP taster status. Physiol Behav. 2001;73:571–577. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(01)00500-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bartoshuk L.M., Duffy V.B., Miller I.J. PTC/PROP tasting: anatomy, psychophysics, and sex effects. Physiol Behav. 1994;56:1165–1171. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90361-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao L., Kirkmeyer S.V., Tepper B.J. A paper screening test to assess genetic taste sensitivity to 6-n-propylthiouracil. Physiol Behav. 2003;78:625–633. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayes J.E., Bartoshuk L.M., Kidd J.R., Duffy V.B. Supertasting and PROP bitterness depends on more than the TAS2R38 gene. Chem Senses. 2008;33:255–265. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjm084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barbarossa I.T., et al. The gustin (CA6) gene polymorphism, rs2274333 (A/G), is associated with fungiform papilla density, whereas PROP bitterness is mostly due to TAS2R38 in an ethnically-mixed population. Physiol Behav. 2015;138:6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melis M., et al. Dose-dependent effects of L-Arginine on PROP bitterness intensity and latency and characteristics of the chemical interaction between PROP and L-Arginine. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wooding S., et al. Natural selection and molecular evolution in PTC, a bitter-taste receptor gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:637–646. doi: 10.1086/383092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bufe B., et al. The molecular basis of individual differences in phenylthiocarbamide and propylthiouracil bitterness perception. Curr Biol. 2005;15:322–327. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tepper B.J., et al. Variation in the bitter-taste receptor gene TAS2R38, and adiposity in a genetically isolated population in Southern Italy. Obesity. 2008;16:2289–2295. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim U.K., et al. Positional cloning of the human quantitative trait locus underlying taste sensitivity to phenylthiocarbamide. Science. 2003;299:1221–1225. doi: 10.1126/science.1080190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prodi D.A., et al. Bitter taste study in a Sardinian genetic isolate supports the association of phenylthiocarbamide sensitivity to the TAS2R38 bitter receptor gene. Chem Senses. 2004;29:697–702. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjh074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melis M., et al. The gustin (CA6) gene polymorphism, rs2274333 (A/G), as a mechanistic link between PROP tasting and fungiform taste papilla density and maintenance. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tepper B.J., Nurse R.J. Fat perception is related to PROP taster status. Physiol Behav. 1997;61:949–954. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(96)00608-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yackinous C., Guinard J.X. Relation between PROP taster status and fat perception, touch, and olfaction. Physiol Behav. 2001;72:427–437. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00430-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Essick G., Chopra A., Guest S., McGlone F. Lingual tactile acuity, taste perception, and the density and diameter of fungiform papillae in female subjects. Physiol Behav. 2003;80:289–302. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prescott J., Swain-Campbell N. Responses to repeated oral irritation by capsaicin, cinnamaldehyde and ethanol in PROP tasters and non-tasters. Chem Senses. 2000;25:239–246. doi: 10.1093/chemse/25.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duffy V.B., Peterson J.M., Bartoshuk L.M. Associations between taste genetics, oral sensation and alcohol intake. Physiol Behav. 2004;82:435–445. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Melis M., et al. Sensory perception of and salivary protein response to astringency as a function of the 6-n-propylthioural (PROP) bitter-taste phenotype. Physiol Behav. 2017;173:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Melis M., et al. Associations between orosensory perception of oleic acid, the common single nucleotide polymorphisms (rs1761667 and rs1527483) in the CD36 gene, and 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP) tasting. Nutrients. 2015;7:2068–2084. doi: 10.3390/nu7032068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kirkmeyer S.V., Tepper B.J. Understanding creaminess perception of dairy products using free-choice profiling and genetic responsivity to 6-n-propylthiouracil. Chem Senses. 2003;28:527–536. doi: 10.1093/chemse/28.6.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keller K.L., Steinmann L., Nurse R.J., Tepper B.J. Genetic taste sensitivity to 6-n-propylthiouracil influences food preference and reported intake in preschool children. Appetite. 2002;38:3–12. doi: 10.1006/appe.2001.0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bell K.I., Tepper B.J. Short-term vegetable intake by young children classified by 6-n-propylthoiuracil bitter-taste phenotype. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:245–251. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dinehart M.E., et al. Bitter taste markers explain variability in vegetable sweetness, bitterness, and intake. Physiol Behav. 2006;87:304–313. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Calò C., et al. Polymorphisms in TAS2R38 and the taste bud trophic factor, gustin gene co-operate in modulating PROP taste phenotype. Physiol Behav. 2011;104:1065–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Padiglia A., et al. Sensitivity to 6-n-propylthiouracil is associated with gustin (carbonic anhydrase VI) gene polymorphism, salivary zinc, and body mass index in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:539–545. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Drayna D., et al. Genetic analysis of a complex trait in the Utah Genetic Reference Project: a major locus for PTC taste ability on chromosome 7q and a secondary locus on chromosome 16p. Hum Genet. 2003;112:567–572. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-0911-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reed D.R., et al. Localization of a gene for bitter-taste perception to human chromosome 5p15. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:1478–1480. doi: 10.1086/302367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cabras T., et al. Responsiveness to 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP) is associated with salivary levels of two specific basic proline-rich proteins in humans. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Melis M., et al. Marked increase in PROP taste responsiveness following oral supplementation with selected salivary proteins or their related free amino acids. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Doty R.L., Kamath V. The influences of age on olfaction: a review. Front Psychol. 2014;5:20. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Methven L., Allen V.J., Withers C.A., Gosney M.A. Ageing and taste. Proc Nutr Soc. 2012;71:556–565. doi: 10.1017/S0029665112000742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Melis M., et al. TAS2R38 bitter taste receptor and attainment of exceptional longevity. Sci Rep. 2019;9:18047. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-54604-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Whissell-Buechy D. Effects of age and sex on taste sensitivity to phenylthiocarbamide (PTC) in the Berkeley Guidance sample. Chem Senses. 1990;15:39–57. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mennella J., Pepino M.Y., Duke F., Reed D. Age modifies the genotype-phenotype relationship for the bitter receptor TAS2R38. BMC Genet. 2010;11:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-11-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tepper B.J., et al. Genetic variation in bitter taste and plasma markers of anti-oxidant status in college women. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2009;60(Suppl 2):35–45. doi: 10.1080/09637480802304499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tepper B.J., et al. Greater energy intake from a buffet meal in lean, young women is associated with the 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP) non-taster phenotype. Appetite. 2011;56:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.11.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tepper B.J., Ullrich N.V. Influence of genetic taste sensitivity to 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP), dietary restraint and disinhibition on body mass index in middle-aged women. Physiol Behav. 2002;75:305–312. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(01)00664-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Goldstein G.L., Daun H., Tepper B.J. Influence of PROP taster status and maternal variables on energy intake and body weight of pre-adolescents. Physiol Behav. 2007;90:809–817. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Melis M., et al. Differences in Salivary Proteins as a Function of PROP Taster Status and Gender in Normal Weight and Obese Subjects. Molecules. 2021:26. doi: 10.3390/molecules26082244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Carta G., et al. Participants with Normal Weight or with Obesity Show Different Relationships of 6-n-Propylthiouracil (PROP) Taster Status with BMI and Plasma Endocannabinoids. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1361. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01562-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tomassini Barbarossa I., et al. Taste sensitivity to 6-n-propylthiouracil is associated with endocannabinoid plasma levels in normal-weight individuals. Nutrition. 2013;29:531–536. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Enoch M.A., Harris C.R., Goldman D. Does a reduced sensitivity to bitter taste increase the risk of becoming nicotine addicted? Addict Behav. 2001;26:399–404. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00117-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mangold J.E., et al. Bitter taste receptor gene polymorphisms are an important factor in the development of nicotine dependence in African Americans. J Med Genet. 2008;45:578–582. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.057844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Risso D.S., et al. Genetic Variation in the TAS2R38 Bitter Taste Receptor and Smoking Behaviors. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee R.J., et al. T2R38 taste receptor polymorphisms underlie susceptibility to upper respiratory infection. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4145–4159. doi: 10.1172/JCI64240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee R.J., Cohen N.A. Role of the bitter taste receptor T2R38 in upper respiratory infection and chronic rhinosinusitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;15:14–20. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Adappa N.D., et al. The bitter taste receptor T2R38 is an independent risk factor for chronic rhinosinusitis requiring sinus surgery. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014;4:3–7. doi: 10.1002/alr.21253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee R.J., Cohen N.A. The emerging role of the bitter taste receptor T2R38 in upper respiratory infection and chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2013;27:283–286. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2013.27.3911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Adappa N.D., et al. TAS2R38 genotype predicts surgical outcome in nonpolypoid chronic rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6:25–33. doi: 10.1002/alr.21666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Adappa N.D., et al. Correlation of T2R38 taste phenotype and in vitro biofilm formation from nonpolypoid chronic rhinosinusitis patients. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6:783–791. doi: 10.1002/alr.21803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Adappa N.D., et al. T2R38 genotype is correlated with sinonasal quality of life in homozygous DeltaF508 cystic fibrosis patients. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6:356–361. doi: 10.1002/alr.21675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Workman A.D., Cohen N.A. Bitter taste receptors in innate immunity: T2R38 and chronic rhinosinusitis. J Rhinol -Otol. 2017;5:12–18. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Melis M., et al. Taste disorders are partly genetically determined: Role of the TAS2R38 gene, a pilot study. Laryngoscope. 2019 doi: 10.1002/lary.27828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Basson M.D., et al. Association between 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP) bitterness and colonic neoplasms. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:483–489. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2462-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Carrai M., et al. Association between TAS2R38 gene polymorphisms and colorectal cancer risk: a case-control study in two independent populations of Caucasian origin. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Choi J.H., et al. Genetic variation in the TAS2R38 bitter taste receptor and gastric cancer risk in Koreans. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26904. doi: 10.1038/srep26904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cossu G., et al. 6-n-propylthiouracil taste disruption and TAS2R38 nontasting form in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2018;33:1331–1339. doi: 10.1002/mds.27391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Oppo V., et al. "Smelling and tasting" Parkinson's disease: using senses to improve the knowledge of the disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020;12:43. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2020.00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vascellari S., et al. Genetic variants of TAS2R38 bitter taste receptor associate with distinct gut microbiota traits in Parkinson's disease: A pilot study. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;165:665–674. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Melis M., et al. Molecular and genetic factors involved in olfactory and gustatory deficits and associations with microbiota in Parkinson's Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2021:22. doi: 10.3390/ijms22084286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Naciri L.C., et al. Automated classification of 6-n-propylthiouracil taster status with machine learning. Nutrients. 2022:14. doi: 10.3390/nu14020252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Glanville E.V., Kaplan A.R. Taste perception and the menstrual cycle. Nature. 1965;205:930–931. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(65)80006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Landis B.N., et al. "Taste Strips" - a rapid, lateralized, gustatory bedside identification test based on impregnated filter papers. J Neurol. 2009;256:242–248. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-0088-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mueller C., et al. Quantitative assessment of gustatory function in a clinical context using impregnated "taste strips". Rhinology. 2003;41:2–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mueller C.A., Pintscher K., Renner B. Clinical test of gustatory function including umami taste. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2011;120:358–362. doi: 10.1177/000348941112000602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sollai G., et al. Human tongue electrophysiological response to oleic acid and its associations with PROP Taster Status and the CD36 Polymorphism (rs1761667) Nutrients. 2019:11. doi: 10.3390/nu11020315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sollai G., et al. First objective evaluation of taste sensitivity to 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP), a paradigm gustatory stimulus in humans. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40353. doi: 10.1038/srep40353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Melis M., et al. Electrophysiological responses from the human tongue to the six taste qualities and their relationships with PROP Taster Status. Nutrients. 2020:12. doi: 10.3390/nu12072017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Green B.G., Shaffer G.S., Gilmore M.M. Derivation and evaluation of a semantic scale of oral sensation magnitude with apparent ratio properties. Chem Senses. 1993;18:683–702. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bartoshuk L.M., et al. Valid across-group comparisons with labeled scales: the gLMS versus magnitude matching. Physiol Behav. 2004;82:109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Miller I.J., Reedy F.E. Variations in human taste bud density and taste intensity perception. Physiol Behav. 1990;47:1213–1219. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(90)90374-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Boxer E.E., Garneau N.L. Rare haplotypes of the gene TAS2R38 confer bitter taste sensitivity in humans. SpringerPlus. 2015;4:505. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1277-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.C.M. Bishop, Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning, Springer-Verlag 2006.

- 102.L. Breiman, J.H. Friedman, R.A. Olshen, C.J. Stone, Classification and Regression Trees, 1983.

- 103.Breiman L. Random Forests. Mach Learn. 2001:1. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Goldberger J., Hinton G.E., Roweis S., Salakhutdinov R.R. Neighbourhood components analysis. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2004:17. [Google Scholar]

- 105.L. Prokhorenkova, et al., CatBoost: unbiased boosting with categorical features, Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Curran Associates Inc., Montréal, Canada, 2018, pp. 6639–6649.

- 106.Jiang J., et al. Boosting tree-assisted multitask deep learning for small scientific datasets. J Chem Inf Model. 2020;60:1235–1244. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.9b01184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Friedman J.H. Stochastic gradient boosting. Comput Stat Data Anal. 2002;38:367–378. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Barua S., Islam M.M., Murase K. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2011. A Novel Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique for Imbalanced Data Set Learning. Neural Information Processing. ICONIP 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Browne M.W. Cross-validation methods. J Math Psychol. 2000;44:108–132. doi: 10.1006/jmps.1999.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wu J., et al. Hyperparameter optimization for machine learning models based on bayesian optimization. J Electron Sci Technol. 2019;17:26–40. [Google Scholar]

- 111.L. Zahedi, et al., Search Algorithms for Automated Hyper-Parameter Tuning. arXiv Prepr. 2021;arXiv:2104.14677.

- 112.Lundberg S.M., Lee S.-I. Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Curran Associates Inc. Long Beach; California, USA: 2017. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions; pp. 4768–4777. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Whissell-Buechy D., Wills C. Male and female correlations for taster (P.T.C.) phenotypes and rate of adolescent development. Ann Hum Biol. 1989;16:131–146. doi: 10.1080/03014468700006982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yackinous C.A., Guinard J.X. Relation between PROP (6-n-propylthiouracil) taster status, taste anatomy and dietary intake measures for young men and women. Appetite. 2002;38:201–209. doi: 10.1006/appe.2001.0481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material.