Key Points

Question

What is the current evidence base for interventions focused on addressing polypharmacy on process, clinical, and health care use outcomes?

Findings

This systematic overview of 14 systematic reviews noted that interventions to address polypharmacy appeared to reduce potentially inappropriate prescribing omissions and commissions (low to very low evidence quality). However, these interventions did not appear to meaningfully reduce mortality and health care (moderate to very low evidence quality), falls (moderate to very low evidence quality), or quality of life (very low evidence quality).

Meaning

The findings of this study suggest there remains a lack of high-quality evidence to support the broad implementation of polypharmacy-related interventions.

Abstract

Importance

Polypharmacy is associated with mortality, falls, hospitalizations, and functional and cognitive decline. The study of polypharmacy-related interventions has increased substantially, prompting the need for an updated, more focused systematic overview.

Objective

To systematically evaluate and summarize evidence across multiple systematic reviews (SRs) examining interventions addressing polypharmacy.

Evidence Review

A search was conducted of MEDLINE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects for articles published from January 2017-October 2022, as well as those identified in a previous overview (January 2004-February 2017). Systematic reviews were included regardless of study design, setting, or outcome. The evidence was summarized by 4 categories: (1) medication-related process outcomes (eg, potentially inappropriate medication [PIM] and potential prescribing omission reductions), (2) clinical and functional outcomes, (3) health care use and economic outcomes, and (4) acceptability of the intervention.

Findings

Fourteen SRs were identified (3 from the previous overview), 7 of which included meta-analyses, representing 179 unique published studies. Nine SRs examined medication-related process outcomes (low to very low evidence quality). Systematic reviews using pooled analyses found significant reductions in the number of PIMs, potential prescribing omissions, and total number of medications, and improvements in medication appropriateness. Twelve SRs examined clinical and functional outcomes (very low to moderate evidence quality). Five SRs examined mortality; all mortality meta-analyses were null, but studies with longer follow-up periods found greater reductions in mortality. Five SRs examined falls incidence; results were predominantly null save for a meta-analysis in which PIMs were discontinued. Of the 8 SRs examining quality of life, most (7) found predominantly null effects. Ten SRs examined hospitalizations and readmissions (very low to moderate evidence quality) and 4 examined emergency department visits (very low to low evidence quality). One SR found significant reductions in hospitalizations and readmissions among higher-intensity medication reviews with face-to-face patient components. Another meta-analysis found a null effect. Of the 7 SRs without meta-analyses for hospitalizations and readmissions, all had predominantly null results. Two of 4 SRs found reductions in emergency department visits. Two SRs examined acceptability (very low evidence quality), finding wide variation in the adoption of polypharmacy-related interventions.

Conclusions and Relevance

This updated systematic overview noted little evidence of an association between polypharmacy-related interventions and reduced important clinical and health care use outcomes. More evidence is needed regarding which interventions are most useful and which populations would benefit most.

This systematic overview examines meta-analyses and systematic reviews on the use of polypharmacy-related interventions in adults.

Introduction

The increase in the type and number of medications available to treat chronic and acute conditions has improved global longevity and quality of life. Yet this progress has also seen a corresponding increase in medication-related adverse events, often linked to increased polypharmacy,1 commonly defined as the regular use of 5 or more medications. In the US, rates of polypharmacy are estimated to be as high as 65% for adults aged 65 years and older.2 In Europe, estimates of the prevalence of polypharmacy in older adults range from 26% to 40%3; studies in other countries have found similar rates, from 36% in Australia4 to 42% in South Korea5 to 49% in India.6 The number of medications used on a regular basis has been found to independently be associated with mortality, falls, fractures, hospitalizations, and functional and cognitive decline.1,7

In recognition of the pressing issue of potentially harmful polypharmacy, in 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched Medication Without Harms, a challenge focusing on polypharmacy, high-risk situations (eg, medication errors), and transitions of care.8 The goal of the WHO initiative was to reduce severe, avoidable, medication-related harm by 50% over 5 years. The WHO’s initiative mirrors efforts around the world to recognize, prevent, and address potentially harmful polypharmacy. The amount of literature regarding polypharmacy has correspondingly increased substantially. In our literature search, we found that, in 2017, researchers published approximately 5000 publications mentioning polypharmacy and polypharmacy-related interventions—only a slight increase from 2016. By 2021, there were 10 000 publications mentioning polypharmacy. In 2019, Anderson et al9 published a systematic overview of systematic reviews (SRs) of interventions aimed at addressing polypharmacy. The review, spanning from 2004 to 2017, identified 6 high-quality SRs meeting the criteria. It reported that polypharmacy interventions appeared to improve medication appropriateness but lacked consistent evidence for meaningful outcomes in health care use or mortality. Subsequently, we identified that 110 studies and 34 related SRs on polypharmacy have been published and indexed in PubMed since then. Given the increased focus and the need for updated research search, we present a cumulative overview of interventions addressing polypharmacy. We aimed to ascertain whether recent evidence strengthens the case for improved outcomes, such as quality of life, falls, cognitive and physical function, health care costs, and health care use and mortality outcomes.

Methods

Reporting for this study is based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline and other available methodological guidance for systematic overviews.10

Search Methods

MEDLINE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects were searched for articles published from January 2017 to October 2022, as well as those identified in a previous overview (January 2004 to February 2017). eAppendix 1 in Supplement 1 provides the full search strategy.

Selection of SRs

Systematic reviews, with or without meta-analyses, were eligible for review if they evaluated interventions addressing polypharmacy in adults (age ≥18 years). eAppendix 2 in Supplement 1 provides the full selection strategy. Polypharmacy-related interventions could include any or all of the following: administering type I (review of the prescription list), type II (review of prescriptions and assessing for adherence), or type III (include the former 2 and address issues relating to the patient’s use of medications in the context of their diagnoses) medication reviews; deprescribing, which involves the process of systematically stopping or reducing the dose of medications; conducting patient education and counseling; holding case conferences with interdisciplinary teams; identifying potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) or potential prescribing omissions (PPOs); using pharmacogenomics to determine whether individual differences in the expression of a protein or enzyme affect the metabolism of a drug; using health care professional education and clinical decision support; simplifying medication regimens to reduce complexity and improve adherence; using guidelines or tools, such as the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria or Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Potentially Inappropriate Prescriptions (STOPP)/Screening Tool11; and using medication management tools, such as pill organizers or smartphone apps, to assist patients with using their medications correctly.9,12,13

Data Collection

Following our pilot data collection, we gathered titles from search sources. Two independent reviewers (M.S.K. and N.Q.) assessed these titles, resolving disagreements through discussion. We refined our inclusion criteria and proceeded to review abstracts and full texts. Reviewers resolved discrepancies by reaching a consensus during meetings.

Evaluation of SR Quality

We assessed the methodologic quality of each relevant SR using a previously tested tool with demonstrated validity. We used the A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR 2) instrument.14 AMSTAR 2 has 16 requisite items that are rated as present or absent, such that each SR may receive a score ranging from 0 to 16.

Evaluation of the Quality of Evidence

We used the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) framework, which can be applied to a body of evidence across outcomes.15 The framework criteria include study design, study quality, consistency, generalizability, and publication bias.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two researchers (M.S.K. and N.Q.) extracted the data into a standardized abstraction spreadsheet (eAppendix 3 in Supplement 1), which included elements of the AMSTAR 2 and GRADE criteria.14,16,17 We grouped outcomes reported in the SRs into 4 categories: (1) medication-related process outcomes (eg, reduction in PIMs or PPOs, increase in medication appropriateness or medication adherence), (2) clinical and functional outcomes, (3) health care use and economic outcomes, and (4) acceptability of the intervention among patients and clinicians. We did not conduct pooled analyses given the relatively small number of meta-analyses findings reported for each outcome type.

Results

Study Selection

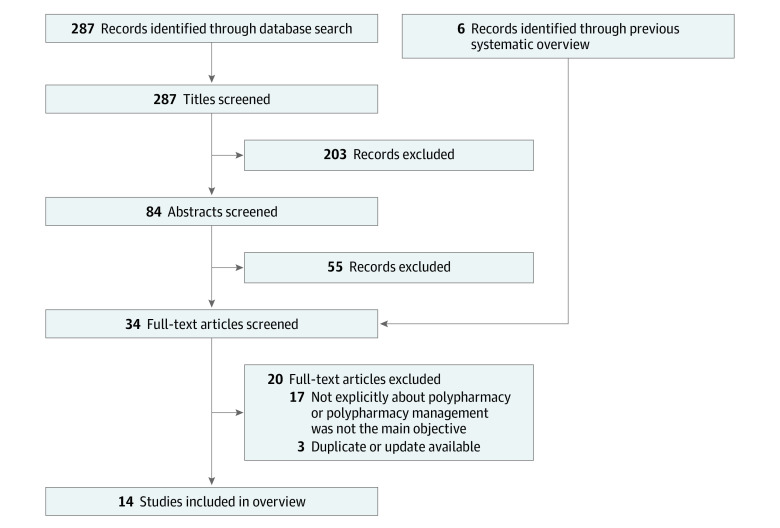

Our search strategy resulted in 287 titles for review, which were narrowed to 84 abstracts. We further narrowed this to 28 full-text articles and 6 SRs from the previous systematic overview. Our final count was 14 SRs, including 11 SRs18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28 from our current search and 3 SRs from the previous systematic overview (Figure, Table 1). An older Cochrane review from the previous overview was excluded because we had an updated review,31 and 2 SRs from the previous overview were excluded because they did not fit our updated, more restrictive inclusion criteria.32,33

Figure. Flowchart of Included Studies.

Table 1. Summary of Included Systematic Reviews Aimed at Addressing Polypharmacy.

| Source | Literature search coverage | No. of articles included and study designs | Population | Setting | Intervention type | Primary outcome measure | Major conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Johansson et al,29 2016 | Database inception-July 2015 | 25 Studies (21 RCTs, 4 non-RCTs) | Adults aged ≥65 y (or 80% of study population aged ≥65 y) receiving ≥4 medications | Community settings/primary care (15), care/nursing homes or assisted living facilities (7), hospital (3) | Pharmacist-led medication review or multicomponent intervention (13), physician-led intervention (4), multidisciplinary team-led intervention (8) | Mortality, hospitalization, changes in No. of medications | The intervention strategies evaluated did not present compelling evidence on reducing mortality, hospitalization rates, or medication use. The interventions in the studies are complex and it is difficult to assess which intervention should be implemented to reduce inappropriate polypharmacy. |

| Page et al,30 2016 | Database inception-February 2015 | 116 Studies (56 RCTs, 22 comparative studies with concurrent control, and 37 comparative studies without concurrent control) (1 article reported on 2 studies) | Older adults (age ≥65 y) receiving ≥1 medication | Community settings (73), residential aged care facilities (29), hospital (14), hospital/community (1), community/residential care (1) | Deprescribing of ≥1 medication, medication class, or therapeutic category; deprescribing polypharmacy; medication reviews; educational programs for health care professionals | Mortality | A notable reduction in mortality was observed in nonrandomized studies and those focusing on patient-specific interventions; however, there was no statistically significant decrease in mortality in randomized studies and studies centered on generalized education programs. |

| Thillainadesan et al,18 2018 | January 1996- April 2017 | 9 RCTs | Older populations with a median age of ≥65 y | Hospital (9) | Deprescribing interventions were either pharmacist- (n = 4), physician- (n = 4), or multidisciplinary team- (n = 1) led | Reduction in PIMs | Based on the available evidence, it appears that deprescribing interventions within a hospital setting are viable and, in most cases, may reduce PIMs while also maintaining safety. |

| Rankin et al,13 2018 | Database inception-February 2018 (18 studies before 2013 were from a prior review) | 18 RCTs, 10 cluster RCTs, 2 non-RCT studies, 2 controlled pre-post studies | Older adults (age ≥65 y, or 80% of study population aged ≥65 y) who had >1 long-term medical condition and were receiving polypharmacy (receiving ≥4 regularly prescribed medications) | Hospital (16), primary care (10), nursing homes (6) | Complex, multifaceted interventions (31), physician-led deprescribing (4), educational interventions to prescribers (10) | Medication appropriateness, PIMs, PPOs, hospital admissions | The outcomes of interventions aimed at enhancing appropriate polypharmacy, such as medication reviews, on clinically significant improvement remain uncertain. Nevertheless, these interventions may offer some slight benefits in terms of reducing PPOs. This conclusion is drawn from just 2 studies, both of which had substantial limitations concerning bias risk. |

| Mizokami et al,19 2019 | January 1972-March 2017 | 9 RCTs | Older adults receiving ≥5 medications | Hospital inpatients (3), community outpatients (6) | CMR of 3 levels: type I (prescription review), type II (medication adherence review), type III (focus on face-to face review of medicines and condition with the patient) | Total number of unplanned hospitalizations or rehospitalizations, and the number of patients experiencing (single or multiple) hospitalizations or rehospitalizations between CMR types | Type III CMRs led to a significant decrease in unplanned admissions among elderly patients during their hospitalization, but had no association with hospital admission rates for outpatient older adults. |

| Ali et al,20 2020 | Database inception-April 2019 | 7 RCTs, 2 observational studies | Older adults aged ≥65 y with chronic conditions who were receiving ≥5 medications/d | Community settings (6), residential care facilities (2), geriatric outpatient clinics (1) | Medication reviews (4), geriatric assessments/ medication screening (2) deprescribing interventions (3) | Falls, physical function | The evidence indicates that interventions addressing polypharmacy have favorable and clinically significant impacts on mobility outcomes, as evidenced by a decrease in the incidence of falls. |

| Lum et al,21 2020 | Database inception-May 2019 | 5 RCTs, 1 retrospective quasi-experimental study | Adults patients (age ≥18 y) with multiple prescription medications and having ≥1 of 3 cardiometabolic diseases: stroke, heart disease, and type 2 diabetes | Cardiac rehabilitation clinic (1), community setting (5) | Pharmacist-led multicomponent intervention (5), clinical-decision support tool–based intervention (1) | Quality of life, drug-related problems, surrogate markers, health care use, and costs | The outcomes of polypharmacy interventions for individuals with cardiometabolic diseases are inconsistent. Interventions involving more frequent and longer direct patient care sessions might yield the most favorable outcomes. |

| Hasan Ibrahim et al,22 2021 | Database inception-April 2020 | 6 RCTs, 1 CBA | Older adults (age ≥65 y) with both multimorbidity (presence of ≥2 long-term conditions) and polypharmacy (concomitant use of ≥4 medications) | Primary care (7) | Practice-based pharmacist-led interventions in primary care (7) | Drug-related problems, medication appropriateness, medication adherence, No. of medications, quality of life, hospital admissions/ readmissions | This systematic review revealed a scarcity of evidence, with only 7 studies exploring the services provided by pharmacists in optimizing medication management for older individuals dealing with both multimorbidity and polypharmacy. |

| Laberge et al,23 2021 | 2004-2020 | 6 cluster RCTs, 3 RCTs, 1 pre-post, 1 cohort with control | Populations at least 80% older adults (age ≥65 y) with multimorbidity (defined as having ≥2 chronic conditions) and having polypharmacy | Primary care clinics (n = 4), nursing homes (n = 1) pharmacies (n = 3), hospital (1), academic medical center (1) | CMRs (10), pharmacogenetic testing with a clinical decision-support tool (1) | PIM use, ADEs, No. of medications, hospital admissions/ readmissions, costs of interventions, cost per PIM avoided, No. of PIMs avoided, No. of ADEs avoided | Because of the diversity in reported outcomes and the suboptimal quality of the economic assessments, the authors acknowledged their inability to reach a definite conclusion regarding the cost-effectiveness of interventions aimed at optimizing medication use. |

| Lee et al,24 2021 | Database inception-August 2020 | 3 RCTs, 2 cluster RCTs | Older adults (age ≥65 y) | Community setting (4), long-term care (1) | Pharmacist-led FRID deprescribing appropriateness (3), physician-led FRID deprescribing appropriateness (2) | Rate of falls, incidence of falls, rate of fall-related injuries | Insufficient strong and high-quality evidence is available to either support or contradict the association between a deprescribing strategy for fall-related injuries in older adults solely based on FRID |

| Tasai et al,25 2021 | Database inception-January 2018 | 4 RCTs (1 study not included in the quantitative analysis due to lack of data) | Older adults (age ≥65 y) receiving ≥4 prescribed medications | Community settings (4) | CMR (4) | Quality of life, hospitalizations, ED visits, medication adherence | Evidence illustrates that comprehensive clinical medication reviews conducted by community pharmacists for older individuals with multiple medications may help in reducing the risk of ED visits. |

| O’Shea et al,262022 | Not reported | 3 RCTs; 6 noncomparative studies, 3 observational studies | Adults with multimorbidity and polypharmacy | Community settings (10), long-term care (2), | Pharmacist-led CMR with pharmacogenetics testing (8), physician-led pharmacogenetics testing (3), pharmacogenetics review (1) | Hospitalizations, ED visits, outpatient visits, health care costs, costs of genetic testing | Owing to the absence of methodologically strong, high-quality research, limited sample sizes, and relatively brief follow-up periods, the authors encountered limited evidence regarding pharmacogenetic interventions in enhancing outcomes for patients with both multimorbidity and prescribed polypharmacy. |

| Reeve et al,27 2022 | 2009-June 2020 | 7 RCTs, 2 non-RCTs, 4 pre-post studies, 2 prospective cohort, 2 retrospective cohort, 2 cross-sectional, 1 exploratory study | Older adults (age ≥50 y) with ≥2 long-term medical conditions and polypharmacy (≥5 long-term medications/d) | Primary care (10), secondary care (7), tertiary care (2), pharmacy call center (1) | Physician-led deprescribing (11), pharmacist-led deprescribing (5), multi-disciplinary team deprescribing (4) | Associations (eg, prescribing-related outcomes), associations (eg, hospitalizations, falls, quality of life), safety (eg, adverse events), acceptability (eg, satisfaction) | The collective reviews acknowledge that deprescribing is a multifaceted intervention and offer endorsement for the safety of well-structured deprescribing approaches. However, the authors also emphasize the necessity of incorporating patient-centered and contextual elements into the best practice models. The authors concluded that the studies provided clear accounts of the objectives of the deprescribing interventions and the target patient populations. Nevertheless, they frequently lacked comprehensive information concerning the individuals responsible for delivering the intervention and the specific methods used. |

| Stötzner et al,28 2022 | Database inception-July 2021 | 15 RCTs, 27 non-comparison pre-post studies, 5 randomized pre-post approach, 9 retrospective studies, 2 study designs not reported | Patients with all psychiatric diagnoses | Nursing homes (39), psychiatric inpatient settings (10), psychiatric outpatient settings (9) | Individual medication review (22); CMR (36); educational programs, guideline reviews, or consulting services (12); automatic alerts (4) | Drug-related problems, medication appropriateness, hospital admissions, ED visits, falls, frailty measures, mortality, cognitive status, health care costs | Interventions targeting polypharmacy can result in enhanced drug-related outcomes among psychiatric populations. Nevertheless, changes in clinical outcomes were frequently minimal and typically less reported. |

Abbreviations: ADE, adverse drug event; CBA, cost-benefit analysis; CMR, comprehensive medication review; ED, emergency department; FRID, fall risk–increasing drugs; PIM, potentially inappropriate medication; PPO, potential prescribing omission; RCT, randomized clinical trial.

Study Characteristics

Included SRs were published between 2016 and 2022; studies from before 2017 were from the previously published systematic overview.9 Seven SRs included meta-analyses,13,19,20,24,25,29,30 10 SRs included both observational studies and randomized clinical trials,13,20,21,22,23,24,26,27,28,29 and 4 SRs included only randomized clinical trials.18,19,25,30 Across all SRs, the mean (SD) AMSTAR 2 score was 10.8 (2.8) (of a possible of 16); across SRs with meta-analyses, the mean AMSTAR 2 score was 12.6 (2.8), and across SRs without meta-analyses, the mean was 9 (1.5) (eTable 1 in Supplement 1).

The SRs included in our review represented a total of 179 unique studies. Of these, 80% (143) were cited by only 1 SR, 12% (20) were cited by 2 SRs, 7% (12) were cited by 3 SRs, and 0.2% (4) were cited by 4 or more SRs (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). The number of studies included ranged from 7 to 58; the mean (SD) was 16 (15).

Of the 14 SRs, 10 focused exclusively on older adults, defined as a population aged 65 years or older. Another inclusion criterion in some SRs was the presence of multimorbidity or having at least 1 chronic disease.21,22,23,26,27 One study focused on patient populations with psychiatric diagnoses,28 while another focused on patient populations with cardiometabolic chronic diseases (ie, stroke, heart disease, or type 2 diabetes).21 Only 1 study included analyses of subpopulations separately: participants aged 80 years and older, participants aged 65 to 79 years, participants living with dementia, and participants who were cognitively intact.30

The SRs also included diverse study settings. Nearly all SRs included studies set in primary care, outpatient care, or community settings13,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30; 1 focused solely on interventions set in the hospitals18; and 8 included studies set in nursing homes or other long-term care facilities.13,20,23,24,28,29,30 Only 1 SR synthesized results by setting, examining studies in nursing home settings, psychiatric inpatient settings, and psychiatric outpatient settings separately.28

In nearly all studies included in the SRs, medication reviews formed the base of the intervention. Studies detailed in the SRs included numerous other elements, including pharmacogenetic testing,26 physician- or patient-focused educational programs, guidelines or criteria (eg, Beers Criteria,34,35 STOPP/START11,36), tools based on guidelines (eg, Tool to Reduce Inappropriate Medication recommendations based on 2012 Beers Criteria and the Assessing Care of the Vulnerable Elderly tool to identify PPOs), consultancy services, multidisciplinary teams, home safety checklists, computerized clinical decision support, and geriatric assessments. Intervention types in each SR are detailed in eTable 2 in Supplement 1. In many studies detailed in the SRs, a pharmacist or multidisciplinary team reviewed the patient’s medications and provided recommendations or educational materials to prescribers.

Medication-Related Process Outcomes

Nine SRs reported medication-related process outcomes (Table 2).13,18,21,22,23,25,28,29,30 These included total number of and changes in number of medications, total number of and changes in the number of PIMs, drug-related problems, medication-related adverse events, drug-gene interactions, drug-drug interactions, medication appropriateness, medication adherence, actionable pharmacogenetic recommendations, total number of PPOs, and recommendations for changes in medications.

Table 2. Medication-Related Process Outcomes From Systematic Reviews of Studies Examining Polypharmacy Interventions.

| Systematic review | Medication-related process outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of medications | No. of PIMs | No. of PPOs | Medication appropriatenessa | Medication-related problemsb | Medication adherence | |

| Johansson et al,29 2016 | No meta-analysis | No meta-analysis | NA | No meta-analysis | No meta-analysis | No meta-analysis |

| DE | ME | NA | IE | ME | ME | |

| Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | NA | Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | |

| Page et al,30 2016 | MD, −0.99 (95% CI, −1.83 to −0.14) | MD, −0.49 (95% CI, −0.70 to −0.28) | NA | NA | No meta-analysis | NA |

| DE | DE | NA | NA | NE | NA | |

| Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: low | NA | NA | Evidence quality: very low | NA | |

| Thillainadesan et al,18 2018 | NA | No meta-analysis | NA | No meta-analysis | No meta-analysis | NA |

| NA | ME | NA | ME | ME | NA | |

| NA | Evidence quality: low | NA | Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | NA | |

| Rankin et al,13 2018 | NA | No. of PIMs: SMD, −0.22 (95% CI, −0.38 to −0.05) | No. of PPOs: SMD, −0.81 (95% CI, −0.98 to −0.64) | MD, −4.76 (95% CI, −9.20 to −0.33) | No meta-analysis | No meta-analysis |

| NA | DE | DE | IE | ME | ME | |

| NA | % of patients with at least 1 PIM: RR, 0.79 (95% CI, 0.61-1.02) | % of patients with a PPO: RR, 0.40 (95% CI, 0.18- 0.85) | NA | NA | NA | |

| NA | NE | DE | NA | NA | NA | |

| NA | Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: low | Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | |

| Lum et al,212020 | NA | NA | NA | No meta-analysisc | No meta-analysis | No meta-analysisc |

| NA | NA | NA | IE | DE | IE | |

| NA | NA | NA | Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | |

| Hasan Ibrahim et al,22 2021 | No meta-analysis | NA | NA | No meta-analysis | No meta-analysis | No meta-analysis |

| ME | NA | NA | IE | ME | ME | |

| Evidence quality: very low | NA | NA | Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | |

| Laberge et al,23 2021 | No meta-analysis | No meta-analysis | NA | NA | No meta-analysis | NA |

| NE | DE | NA | NA | DE | NA | |

| Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | NA | NA | Evidence quality: very low | NA | |

| Tasai et al,25 2021 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | No meta-analysisc |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | IE | |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Evidence quality: very low | |

| Stötzner et al,28 2022 | No meta-analysis | NA | No meta-analysis | No meta-analysis | No meta-analysis | NA |

| ME | NA | DE | ME | DE | NA | |

| Evidence quality: low | NA | Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: low | Evidence quality: very low | NA | |

Abbreviations: DE, decreased effect; IE, increased effect; MD, mean difference; ME, mixed effect; NA, not applicable; NE, null effect; PIM, potentially inappropriate medication; PPO, potential prescribing omission; RR, risk ratio; SMD, standardized mean difference.

An increase in medication appropriateness is the preferred direction.

Adverse drug reaction, drug-drug interaction, and medication errors.

Results are from 1 study only.

Total Number of Medications

We identified 5 SRs that examined the interventions in terms of the total number of medications; only 1 SR conducted a pooled analysis, finding a reduction in the total number of medications (mean difference [MD], −0.99; 95% CI, −1.83 to −0.14).30 Another SR also found an overall reduction,29 2 found mixed effects (ie, some studies in the SRs found reductions, others found null effects),22,28 and 1 found a null effect.23

Potentially Inappropriate Medications

Five studies examined the number of PIMs. Two SRs using pooled analyses found a significant reduction in the number of PIMs (standardized MD [SMD], −0.22; 95% CI, −0.38 to −0.0513; and MD, −0.49; 95% CI, −0.70 to −0.28),30 but 1 found no significant difference in the proportion of patients with at least 1 PIM (risk ratio [RR], 0.79; 95% CI, 0.61-1.02).13 Three SRs without meta-analyses or pooled analyses found mixed effects, with most studies identifying some reduction in PIMs, but others finding null effects.18,23,29

Potential Prescribing Omissions

Only 2 SRs examined PPOs: 1 found both a significant reduction in the number of PPOs (SMD, −0.81; 95% CI, −0.98 to −0.64) and a reduction in the proportion of patients with at least 1 PPO (RR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.18-0.85).13 The other SR, which included only 1 study and no pooled analyses, also found a decrease.28

Medication Appropriateness

Medication appropriateness, often measured via the Medication Appropriateness Index,37 improved in 413,21,22,29 of 6 SRs. The other 2 SRs18,28 found mixed effects.

Medication-Related Problems

Of the 8 SRs that examined medication-related problems, which include adverse drug reactions and drug-drug interactions, 3 SRs found a reduction,21,23,28 4 found mixed effects,13,18,22,29and 1 SR30 found a null effect.

Medication Adherence

Five SRs measured medication adherence. Two of these found an increase in medication adherence,21,25 while the other 3 found mixed effects.13,22,29

Clinical and Functional Outcomes

Twelve SRs reported clinical and functional outcomes (Table 3).13,18,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,28,29,30 These included mortality, frailty, delirium, cardiovascular events, severity of illness, depression, pain, anxiety, physical function, cognitive status, infections, falls, fall-related injuries, fractures, blood pressure, hemoglobin A1c, fasting blood glucose level, cholesterol level, and triglyceride level. Seven SRs reported quality-of-life outcomes.13,18,21,22,25,28,30

Table 3. Clinical and Functional Outcomes From Systematic Reviews of Studies Examining Polypharmacy Interventions.

| Systematic review | Clinical and functional outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | Incidence of falls | Rate of falls | No. of falls | Quality of life | Cognitive or physical function | |

| Johansson et al,29 2016 | All-cause mortality in all studies: OR, 1.02 (95% CI, 0.84-1.23) | NA | NA | NA | No meta-analysis | No meta-analysis |

| NE | NA | NA | NA | NE | ME | |

| All-cause mortality in studies with longer follow-up periods (12-18 mo): OR, 0.93 (95% CI, 0.69-1.24) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| NE | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| All-cause mortality in studies with shorter follow-up periods (2-6 mo): OR, 1.13 (95% CI, 0.86-1.50) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| NE | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| All-cause mortality in RCTs or CRCTs: OR, 1.05 (95% CI, 0.85-1.29) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| NE | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Evidence quality: low | NA | NA | NA | Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | |

| Page et al,30 2016 | Mortality in randomized studies: OR, 0.82 (95% CI, 0.61-1.11) | Risk of experiencing at least 1 fall: OR, 0.65 (95% CI, 0.40-1.05) | NA | No. of falls among patients with at least 1 fall: MD, −0.11 (95% CI, −0.21 to −0.02) | No meta-analysis | No meta-analysis |

| NE | NE | NA | DE | NE | NE | |

| Mortality in nonrandomized studies: OR, 0.32 (95% CI, 0.17-0.60) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| DE | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Mortality in participants aged ≥80 y (randomized studies only): OR, 0.88 (95% CI, 0.58-1.34) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| NE | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Mortality in participants aged 65-79 y (randomized studies only): OR, 0.64 (95% CI, 0.40-1.04) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| NE | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Mortality in participants living with dementia (randomized studies only): OR, 0.89 (95% CI, 0.63-1.27) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| NE | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Mortality in cognitively intact participants (randomized studies only): OR, 0.64 (95% CI, 0.36-1.13) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| NE | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Evidence quality: low | Evidence quality: very low | NA | Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | NA | |

| Thillainadesan et al,18 2018 | No meta-analysis | No meta-analysis | No meta-analysisa | No meta-analysisa | No meta-analysis | No meta-analysis |

| NE | ME | DE | NE | ME | ME | |

| Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | |

| Rankin et al,13 2018 | NA | NA | NA | NA | No meta-analysis | NA |

| ME | ||||||

| Evidence quality: very low | ||||||

| Ali et al,20 2020 | NA | Incidence of falls (clinical trials only): RR, 0.87 (95% CI, 0.57-1.31) | NA | No meta-analysisa | NA | Physical function (clinical trials only): SMD, 0.00 (95% CI, −0.21 to 0.20) |

| NA | NE | NA | NE | NA | NE | |

| NA | Incidence of falls in studies where medications were discontinued: RR, 0.51 (95% CI, 0.36-0.71) | NA | NE | NA | NA | |

| NA | DE | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| NA | Evidence quality: low | NA | Evidence quality: moderate | NA | Evidence quality: low | |

| Lum et al,21 2020 | NA | NA | NA | NA | No meta-analysis | NA |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | ME | NA | |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | Evidence quality: very low | NA | |

| Hasan Ibrahim et al,22 2021 | NA | NA | NA | NA | No meta-analysis | NA |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | NE | NA | |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | Evidence quality: very low | NA | |

| Laberge et al,23 2021 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | No meta-analysisa |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NE | |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Evidence quality: very low | |

| Lee et al,24 2021 | NA | Falls incidence: RR, 1.04 (95% CI, 0.86-1.26) | Falls rate: rate ratio, 0.98 (95% CI, 0.63-1.51) | NA | NA | NA |

| NA | NE | NE | NA | NA | NA | |

| NA | Falls incidence: RD, 0.01 (95% CI, −0.06 to 0.09) | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| NA | NE | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| NA | Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | NA | NA | NA | |

| Tasai et al,25 2021 | NA | NA | NA | NA | No meta-analysis | NA |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | ME | NA | |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | Evidence quality: very low | NA | |

| O’Shea et al,262022 | No meta-analysisa | NA | NA | No meta-analysisa | NA | NA |

| NE | NA | NA | NE | NA | NA | |

| Evidence quality: very low | NA | NA | Evidence quality: very low | NA | NA | |

| Stötzner et al,28 2022 | No meta-analysis; evidence quality: very low | No meta-analysis | NA | No meta-analysis | No meta-analysis | No meta-analysis |

| ME | DE | NA | DE | IE | ME | |

| Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | NA | Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | |

Abbreviations: CRCT, cluster randomized clinical trial; DE, decreased effect; IE, increased effect; MD, mean difference; ME, mixed effect; NA, not applicable; NE, null effect; OR, odds ratio; RD, risk difference; RR, risk ratio; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Results are from 1 study only.

Mortality

Five SRs examined the polypharmacy interventions in terms of mortality, of which 4 found a null effect18,26,29,30 and 1 found mixed effects.28 Two SRs included meta-analyses. One SR using numerous sensitivity analyses reported an odds ratio (OR) of 1.02 in all studies examining all-cause mortality (95% CI, 0.84-1.23),29 an OR of 0.93 (95% CI, 0.69-1.24) among studies with longer follow-up periods (12-18 months), an OR of 1.13 (95% CI, 0.86-1.50) among studies with shorter follow-up periods (2-6 months), and an OR of 1.05 (95% CI, 0.85-1.29) among randomized clinical trials. The other SR reported an OR of 0.82 (95% CI, 0.61-1.11) among randomized studies and an OR of 0.32 (95% CI, 0.17-0.60) among nonrandomized studies.30 The authors also conducted subpopulation analyses, finding a larger reduced effect of mortality associated with the interventions in participants aged 65 to 79 years (OR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.40-1.04) vs participants aged 80 years or older (OR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.58-1.34).30 The authors also found a larger effect size among patients without dementia (OR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.36-1.13) compared with patients living with dementia (OR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.63-1.27).30

Falls

Five SRs examined the incidence of falls: 2 of these found a reduction (1 SR only found a reduction when medications were discontinued),20,28 1 found mixed effects (ie, a mix of null effects and small reductions in fall incidence),18and 2 found a null effect.24,30 Of the SRs that conducted pooled analyses for the incidence of falls, 1 found a nonsignificant RR of 0.87 (95% CI, 0.57-1.31), but a larger, significant outcome when the PIMs were discontinued (RR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.36-0.71), using a fixed-effects meta-analysis.20 The authors found that the pooled effect was not significant when a random effects meta-analysis was used (RR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.27-1.06).20 For the risk of experiencing at least 1 fall, 1 SR found an OR of 0.65 (95% CI, 0.40-1.05).30 Finally, with regard to fall risk incidence, another SR reported null effects, with a fall risk incidence of 1.04 (95% CI, 0.86-1.26) and a risk difference of 0.01 (95% CI, −0.06 to 0.09).24 Two SRs examined the rate of falls. One found a null effect (rate ratio, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.63-1.51),24 while the other did not conduct a pooled analysis, but found a reduction based on 1 study.18 Five SRs examined the number of falls. One SR conducted a pooled analysis of the number of falls among patients with at least 1 fall, finding an MD of −0.11 (95% CI, −0.21 to 0.02).30 Three other SRs relied on 1 study alone each to report findings; all found a null effect.18,20,26 Another SR did not conduct a meta-analysis, but found a reduction in the number of falls among studies examined.28

Quality of Life

Eight SRs examined quality of life; 1 of these found an increase among individuals receiving a polypharmacy intervention,28 4 found mixed effects,13,18,21,25 and 3 found null effects.22,29,30 Six SRs examined cognitive or physical function; 3 of these found mixed effects18,28,29 and 3 found null effects.20,23,30 The only SR conducting a pooled analysis of physical function in clinical trials reported a null result (SMD, 0.00; 95% CI, −0.21 to 0.20).20

Health Care Use and Economic Outcomes

Ten SRs reported health care use outcomes (Table 4).13,18,19,21,22,23,25,26,28,29 These included hospitalizations, readmissions, emergency department (ED) visits, and outpatient visits. Five SRs reported cost-related outcomes.21,23,26,28,29 These included costs of the intervention, total costs, cost-benefit ratios, and cost-effectiveness (eg, cost per quality-adjusted life-year, cost per PIM averted, cost per adverse drug event averted).

Table 4. Health Care Use Outcomes From Systematic Reviews of Studies Examining Polypharmacy Interventions.

| Systematic reviews | Health care use outcomes | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalizations or readmissions | Emergency department visits | Health care costs | |

| Johansson et al,29 2016 | No meta-analysis | NA | No meta-analysis |

| ME | NA | NE | |

| Evidence quality: very low | NA | Evidence quality: very low | |

| Thillainadesan et al,18 2018 | No meta-analysis | NA | NA |

| NE | NA | NA | |

| Evidence quality: very low | NA | NA | |

| Rankin et al,13 2018 | No meta-analysis | NA | NA |

| ME | NA | NA | |

| Evidence quality: very low | NA | NA | |

| Mizokami et al,19 2019 | Type I/II CMRs: RR, 1.22 (95% CI, 1.07-1.38) | NA | NA |

| IE | NA | NA | |

| Type III CMRs: RR, 0.86 (95% CI, 0.79-0.95) | NA | NA | |

| DE | NA | NA | |

| Inpatients only: RR, 0.89 (95% CI, 0.80-0.98) | NA | NA | |

| DE | NA | NA | |

| Outpatients only: RR, 1.11 (95% CI, 0.99-1.24) | NA | NA | |

| NE | NA | NA | |

| Evidence quality: moderate | NA | NA | |

| Lum et al,21 2020 | No meta-analysisa | No meta-analysisa | No meta-analysis |

| DE | NE | DE | |

| Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | |

| Hasan Ibrahim et al,22 2021 | No meta-analysis | ||

| NE | NA | NA | |

| Evidence quality: very low | NA | NA | |

| Laberge et al,23 2021 | No meta-analysis | No meta-analysis | |

| ME | NA | DE | |

| Evidence quality: very low | NA | Evidence quality: very low | |

| Tasai et al,252021 | RR, 0.88 (95% CI, 0.78-1.00) | RR, 0.68 (95% CI, 0.48-0.96) | NA |

| NE | DE | NA | |

| Evidence quality: low | Evidence quality: low | NA | |

| O’Shea et al,26 2022 | No meta-analysis | No meta-analysisa | No meta-analysis |

| ME | DE | DE | |

| Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | |

| Stötzner et al,28 2022 | No meta-analysis Evidence quality: very low |

No meta-analysis | No meta-analysis |

| ME | ME | DE | |

| Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | Evidence quality: very low | |

Abbreviations: CMRs, comprehensive medication reviews; DE, decreased effect; IE, increased effect; ME, mixed effect; NA, not applicable; NE, null effect; RR, risk ratio.

Results are from a single study only.

Hospitalizations and Readmissions

Ten SRs examined hospitalizations and/or readmissions.13,18,19,21,22,23,25,26,28,29 One SR19 categorized the intensity of the intervention as low intensity (type I and type II comprehensive medication reviews [CMRs]) and high intensity (type III CMR), finding that the low-intensity intervention led to a slight increase in hospitalizations (RR, 1.22, 95% CI, 1.07-1.38) while the high-intensity intervention led to a reduction in hospitalizations (RR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.79-0.95). This SR also examined outcomes by medication review intervention setting, finding a larger, significant outcome in inpatients (RR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.80-0.98), compared with a nonsignificant outcome in outpatients (RR, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.99-1.24).19 The other SR25 with a meta-analysis found a null effect with regard to hospitalizations (RR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.78-1.00). In the SRs without meta-analyses, we found mixed13,23,26,28,29 or null effects22,23; one SR without meta-analysis found a decreased effect.21 Four SRs examined ED visits.21,25,26,28 Only 1 SR25 conducted a pooled analysis, finding a reduction in ED visits (0.68; 95% CI, 0.48-0.96). Of the 3 other SRs, 2 relied on only 1 study each (1 found a null effect21 and another found a reduction in ED visits26), and 1 found mixed effects.28

Health Care Costs

Four SRs21,23,26,28 found a reduction in health care costs associated with polypharmacy interventions, and 1 SR29 found no significant change in nearly every study that examined this outcome. In 1 SR, estimates of the cost per quality-adjusted life-year gained ranged from £11 885 to £32 466 ($16 346 to $44 651) in the UK and Ireland.23 The cost per PIM avoided was estimated at €1269 (95% CI, €−1400 to €6302) ($922; 95% CI, $1017-$4582). No other SR specifically looked at quality-adjusted life-years or cost-effectiveness.

Acceptability Among Patients and Physicians

Two SRs reported on outcomes assessing the acceptability of the intervention among patients and clinicians.27,28 These included acceptance or adoption of the medication-related recommendations.

The acceptability of the interventions among patients and physicians was positive among the studies reporting this outcome in one SR,27 while adoption rates of the interventions were found to have wide variation (16%-99%) in another SR.28

Discussion

Review of Findings

Our updated systematic overview, featuring 14 high-quality SRs comprising 179 individual studies, suggests that polypharmacy interventions show some evidence of reducing PIMs and PPOs, enhancing medication adherence, and improving medication appropriateness. However, the overall quality of evidence for these outcomes remains consistently very low. Five SRs examining mortality mostly reported no significant findings. The evidence regarding the association between polypharmacy interventions and hospitalizations or readmissions was mixed, with a tendency toward null effects. Most reviews lacking pooled effects showed either null or mixed outcomes. However, interventions among outpatients and with more intensive medication reviews were associated with reduced hospitalizations in one SR19 and a nonsignificant reduction in hospitalizations in another SR.25 Polypharmacy interventions showed limited evidence in reducing falls, with most SRs reporting no association with fall incidence or number. However, one SR reported a significant reduction in falls when PIMs were discontinued. Evidence for enhancing quality of life was consistently rated very low, with most SRs showing no significant outcomes. Moreover, despite polypharmacy being a significant risk factor for adverse drug reactions, only half of the SRs examined this outcome.

Although many SRs were of high quality according to AMSTAR 2, the evidence for most outcomes was of low to very low quality, primarily due to consistent high risk of bias. This bias often stems from the lack of blinding of participants and personnel in polypharmacy intervention studies, which is challenging unless blind tapers are used. Moreover, the evidence was downgraded in numerous reviews due to result inconsistencies, likely resulting from diverse responses among populations with various comorbidities and medications. Some studies discontinued high-risk medications, while others undertook partial changes or substitutions, potentially reducing risk but not enough to prevent significant clinical outcomes, such as mortality, hospitalizations, falls, and fractures.

An important issue that requires more research is which polypharmacy-related interventions are most effective in improving outcomes. The fact that numerous SRs had mixed findings highlights the suggestion that some interventions may be more effective than others; parsing the intensity or best components of these interventions requires further study. Only 1 SR categorized interventions into their level of intensity, creating 3 categories of CMR.19 A type I CMR involves a prescription review, a type II CMR involves a prescription review plus medication adherence review, and a type III CMR involves the previous categories plus a face-to-face (or video) review of medicines and conditions with the patient. The authors found that only CMR type III interventions were associated with reduced unplanned readmissions.19

Further study is required to understand for whom polypharmacy-related interventions prove most useful. While most SRs in our overview focused on older adult populations (age ≥65 years) with polypharmacy and multimorbidity requirements, a subanalysis by Page et al30suggests potentially differing outcomes within these populations. Page et al found a possibly greater reduction in mortality in patients aged 65 to 79 years compared with those aged 80 years or older, and a reduction in mortality among patients without dementia compared with those with dementia. These findings indicate a need for more studies examining subpopulations, revealing a major gap in evidence regarding the differences among specific groups might benefit more from interventions addressing polypharmacy.

Limitations

We observed a limitation in the reviewed SRs and primary studies: insufficient detail in intervention descriptions. Inadequate information about intervention types and intensity could affect categorization and outcome assessment. To enhance reporting, journals might consider mandating the use of checklists such as the Template for Intervention Description and Replication for better intervention description.38 Our overview had limitations in not including Google Scholar or gray literature, potentially restricting identification of additional SRs. Although we searched 3 databases for relevant articles, our exclusion of SRs involving adults younger than 65 years limited our scope. This decision was made to encompass all adults, acknowledging the risk of polypharmacy-related adverse drug events, not only in those aged 65 years and older but also in younger adults nearing older age. Furthermore, some SRs and their studies had unclear criteria regarding the types of medications considered, whether only scheduled or also as-needed medications, over-the-counter medications, vitamins, and supplements.

Conclusions

While the evidence base for polypharmacy-related interventions has expanded since 2019, gaps in research persist. Understanding the most useful interventions for specific high-risk populations remains a key priority. Our updated systematic overview reveals mixed findings on interventions addressing polypharmacy. They show promise in reducing potentially inappropriate medications and prescribing omissions but limited evidence in reducing mortality, hospitalizations, readmissions, or falls.

eAppendix 1. Full Search Strategy for Updated Systematic Overview of Systematic Reviews Evaluating Interventions Addressing Polypharmacy

eAppendix 2. Selection Strategy

eAppendix 3. Standardized Abstraction Form for Updated Systematic Overview of Systematic Reviews Evaluating Interventions Addressing Polypharmacy

eTable 1. AMSTAR 2 Scores for Systematic Reviews of Studies Examining Polypharmacy Interventions

eTable 2. Intervention Types by Systematic Review

eTable 3. Citation Matrix

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Khezrian M, McNeil CJ, Murray AD, Myint PK. An overview of prevalence, determinants and health outcomes of polypharmacy. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2020;11:2042098620933741. doi: 10.1177/2042098620933741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young EH, Pan S, Yap AG, Reveles KR, Bhakta K. Polypharmacy prevalence in older adults seen in United States physician offices from 2009 to 2016. PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0255642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Midão L, Giardini A, Menditto E, Kardas P, Costa E. Polypharmacy prevalence among older adults based on the survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2018;78:213-220. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2018.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Page AT, Falster MO, Litchfield M, Pearson SA, Etherton-Beer C. Polypharmacy among older Australians, 2006-2017: a population-based study. Med J Aust. 2019;211(2):71-75. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho HJ, Chae J, Yoon SH, Kim DS. Aging and the prevalence of polypharmacy and hyper-polypharmacy among older adults in South Korea: a national retrospective study during 2010-2019. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:866318. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.866318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhagavathula AS, Vidyasagar K, Chhabra M, et al. Prevalence of polypharmacy, hyperpolypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:685518. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.685518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fried TR, O’Leary J, Towle V, Goldstein MK, Trentalange M, Martin DK. Health outcomes associated with polypharmacy in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(12):2261-2272. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . Medication without harm. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.who.int/initiatives/medication-without-harm

- 9.Anderson LJ, Schnipper JL, Nuckols TK, et al. ; Members of the PHARM-DC group . A systematic overview of systematic reviews evaluating interventions addressing polypharmacy. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2019;76(21):1777-1787. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxz196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Mahony D, Cherubini A, Guiteras AR, et al. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 3. Eur Geriatr Med. 2023;14(4):625-632. doi: 10.1007/s41999-023-00777-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bulajeva A, Labberton L, Leikola S, et al. Medication review practices in European countries. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2014;10(5):731-740. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2014.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rankin A, Cadogan CA, Patterson SM, et al. Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy for older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;9(9):CD008165. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008165.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meader N, King K, Llewellyn A, et al. A checklist designed to aid consistency and reproducibility of GRADE assessments: development and pilot validation. Syst Rev. 2014;3(1):82. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-3-82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1, introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):383-394. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thillainadesan J, Gnjidic D, Green S, Hilmer SN. Impact of deprescribing interventions in older hospitalised patients on prescribing and clinical outcomes: a systematic review of randomised trials. Drugs Aging. 2018;35(4):303-319. doi: 10.1007/s40266-018-0536-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mizokami F, Mizuno T, Kanamori K, et al. Clinical medication review type III of polypharmacy reduced unplanned hospitalizations in older adults: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19(12):1275-1281. doi: 10.1111/ggi.13796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ali MU, Sherifali D, Fitzpatrick-Lewis D, et al. Polypharmacy and mobility outcomes. Mech Ageing Dev. 2020;192:111356. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2020.111356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lum MV, Cheung MYS, Harris DR, Sakakibara BM. A scoping review of polypharmacy interventions in patients with stroke, heart disease and diabetes. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020;42(2):378-392. doi: 10.1007/s11096-020-01028-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hasan Ibrahim AS, Barry HE, Hughes CM. A systematic review of general practice-based pharmacists’ services to optimize medicines management in older people with multimorbidity and polypharmacy. Fam Pract. 2021;38(4):509-523. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmaa146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laberge M, Sirois C, Lunghi C, et al. Economic evaluations of interventions to optimize medication use in older adults with polypharmacy and multimorbidity: a systematic review. Clin Interv Aging. 2021;16:767-779. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S304074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee J, Negm A, Peters R, Wong EKC, Holbrook A. Deprescribing fall-risk increasing drugs (FRIDs) for the prevention of falls and fall-related complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2):e035978. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tasai S, Kumpat N, Dilokthornsakul P, Chaiyakunapruk N, Saini B, Dhippayom T. Impact of medication reviews delivered by community pharmacist to elderly patients on polypharmacy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Patient Saf. 2021;17(4):290-298. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Shea J, Ledwidge M, Gallagher J, Keenan C, Ryan C. Pharmacogenetic interventions to improve outcomes in patients with multimorbidity or prescribed polypharmacy: a systematic review. Pharmacogenomics J. 2022;22(2):89-99. doi: 10.1038/s41397-021-00260-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reeve J, Maden M, Hill R, et al. Deprescribing medicines in older people living with multimorbidity and polypharmacy: the TAILOR evidence synthesis. Health Technol Assess. 2022;26(32):1-148. doi: 10.3310/AAFO2475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stötzner P, Ferrebus Abate RE, Henssler J, Seethaler M, Just SA, Brandl EJ. Structured interventions to optimize polypharmacy in psychiatric treatment and nursing homes: a systematic review. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2022;42(2):169-187. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000001521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johansson T, Abuzahra ME, Keller S, et al. Impact of strategies to reduce polypharmacy on clinically relevant endpoints: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82(2):532-548. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Page AT, Clifford RM, Potter K, Schwartz D, Etherton-Beer CD. The feasibility and effect of deprescribing in older adults on mortality and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82(3):583-623. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patterson SM, Cadogan CA, Kerse N, et al. Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy for older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(10):CD008165. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008165.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kröger E, Wilchesky M, Marcotte M, et al. Medication use among nursing home residents with severe dementia: identifying categories of appropriateness and elements of a successful intervention. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(7):629.e1-629.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boghossian TA, Rashid FJ, Thompson W, et al. Deprescribing versus continuation of chronic proton pump inhibitor use in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;3(3):CD011969. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011969.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, Waller JL, Maclean JR, Beers MH. Updating the Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: results of a US consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(22):2716-2724. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.22.2716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.By the 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel . American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674-694. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, O’Connor MN, Ryan C, Gallagher P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44(2):213-218. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Samsa GP, et al. A method for assessing drug therapy appropriateness. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(10):1045-1051. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90144-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Full Search Strategy for Updated Systematic Overview of Systematic Reviews Evaluating Interventions Addressing Polypharmacy

eAppendix 2. Selection Strategy

eAppendix 3. Standardized Abstraction Form for Updated Systematic Overview of Systematic Reviews Evaluating Interventions Addressing Polypharmacy

eTable 1. AMSTAR 2 Scores for Systematic Reviews of Studies Examining Polypharmacy Interventions

eTable 2. Intervention Types by Systematic Review

eTable 3. Citation Matrix

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement