This cross-sectional study investigates the association between the COVID-19 pandemic and trends in medication treatment initiation across various behavioral health conditions.

Key Points

Question

How was the COVID-19 pandemic associated with trends in medication treatment initiation across various behavioral health conditions in the US?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 105 500 490 prescriptions dispensed between April 2018 and March 2022 obtained from a US prescription database, trends in the number of incident prescriptions dispensed nationally for Schedule II (C-II) stimulant and nonstimulant medications for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) significantly increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, exceeding prepandemic rates, notably in young adults and women. Incident prescription trends for antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and buprenorphine for opioid use disorder did not significantly change.

Meaning

The differential changes during the COVID-19 pandemic in incident prescription trends for ADHD, particularly for C-II stimulants, underscore the need for robust policies to address unmet needs while balancing public health concerns.

Abstract

Importance

The COVID-19 pandemic reportedly increased behavioral health needs and impacted treatment access.

Objective

To assess changes in incident prescriptions dispensed for medications commonly used to treat depression, anxiety, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and opioid use disorder (OUD), before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This was a cross-sectional study using comprehensive, population-level, nationally projected data from IQVIA National Prescription Audit on incident prescriptions (prescriptions dispensed to patients with no prior dispensing from the same drug class in the previous 12 months) dispensed for antidepressants, benzodiazepines, Schedule II (C-II) stimulants, nonstimulant medications for ADHD, and buprenorphine-containing medication for OUD (MOUD), from US outpatient pharmacies. Data were analyzed from April 2018 to March 2022.

Exposure

Incident prescriptions by drug class (by prescriber specialty, patient age, and sex) and drug.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Interrupted time-series analysis to compare changes in trends in the monthly incident prescriptions dispensed by drug class and percentage changes in aggregate incident prescriptions dispensed between April 2018 and March 2022.

Results

Incident prescriptions dispensed for the 5 drug classes changed from 51 500 321 before the COVID-19 pandemic to 54 000 169 during the pandemic. The largest unadjusted percentage increase in incident prescriptions by prescriber specialty was among nurse practitioners across all drug classes ranging from 7% (from 1 811 376 to 1 944 852; benzodiazepines) to 78% (from 157 578 to 280 925; buprenorphine MOUD), whereas for patient age and sex, the largest increases were within C-II stimulants and nonstimulant ADHD drugs among patients aged 20 to 39 years (30% [from 1 887 017 to 2 455 706] and 81% [from 255 053 to 461 017], respectively) and female patients (25% [from 2 352 095 to 2 942 604] and 59% [from 395 678 to 630 678], respectively). Trends for C-II stimulants and nonstimulant ADHD drugs (slope change: 4007 prescriptions per month; 95% CI, 1592-6422 and 1120 prescriptions per month; 95% CI, 706-1533, respectively) significantly changed during the pandemic, exceeding prepandemic trends after an initial drop at the onset of the pandemic (level changes: −50 044 prescriptions; 95% CI, −80 202 to −19 886 and −12 876 prescriptions; 95% CI, −17 756 to −7996, respectively). Although buprenorphine MOUD dropped significantly (level change: −2915 prescriptions; 95% CI, −5513 to −318), trends did not significantly change for buprenorphine MOUD, antidepressants, or benzodiazepines.

Conclusions and Relevance

Incident use of many behavioral health medications remained relatively stable during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US, whereas ADHD medications, notably C-II stimulants, sharply increased. Additional research is needed to differentiate increases due to unmet need vs overprescribing, highlighting the need for further ADHD guideline development to define treatment appropriateness.

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, widespread concerns arose regarding increased behavioral health needs1 and unprecedented challenges in health care access. In addition to increased morbidity and mortality from COVID-19 infection, pandemic-related stressors and early mitigation measures such as stay-at-home orders, virtual schooling, and economic stressors contributed to concerns of increased behavioral health needs.2 In 2020, cases of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders increased globally by 28% and 26%, respectively.3 Suicide rates surged by the largest annual increase in recent years from 13.5 deaths per 100 000 population in 2020 to 14.1 deaths in 2021.4 Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms in children and youth were reported to have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.5 Despite ongoing mitigation efforts, opioid-involved overdose deaths increased from 49 860 in 2019 to 80 411 in 2021.6 Concerns of behavioral health treatment disruptions, especially access to medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD), were high during the COVID-19 pandemic.7,8

Pandemic-related drivers including increased behavioral health needs, barriers to health care, and mitigation interventions such as telemedicine prescribing flexibilities, may have impacted the use of medications for behavioral health disorders. To maintain access, use of telemedicine increased early in the COVID-19 pandemic.9 Prescribing flexibilities, including exemptions that allowed for practitioners to prescribe controlled substances, Schedule II (C-II) to Schedule V medications, via telemedicine to patients without in-person evaluation10 and to out-of-state patients,11 were implemented as early interventions to help improve access to medications such as buprenorphine, benzodiazepines, and C-II stimulants. Other studies on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on prescribing have generally focused on relatively smaller populations, often using insurance claims data or surveys limited to specific jurisdictions, insurance plans, or health systems.8,9,12,13,14

To overcome these limitations, we examined US national trends in incident prescriptions dispensed from April 2018 through March 2022 for antidepressants, benzodiazepines, C-II stimulants, nonstimulant drugs for ADHD, and buprenorphine MOUD to examine how the COVID-19 pandemic may have changed treatment patterns across different behavioral health needs. Studying incident prescriptions dispensed, as opposed to total (prevalent) dispensed prescriptions, provides insight into changes in medication treatment initiation before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was exempted from review by the US Food and Drug Administration’s Research Involving Human Subjects Committee. Patient informed consent was waived owing to the use of deidentified patient data. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.

National estimates of incident prescriptions dispensed from US outpatient pharmacies were obtained from a commercial database, the National Prescription Audit (NPA; [IQVIA]).15 The NPA captures more than 94% of US outpatient prescription drug activity from retail, mail-order, and long-term care pharmacies and provides national-level estimates based on projection. Self-payment (cash) prescriptions and those covered by commercial insurance, Medicaid, and Medicare were included. We studied incident prescriptions using the New Therapy Start (IQVIA) prescription measure, defined as a prescription dispensed to a patient with no previous transaction within the same drug class in the prior 12 months.

We analyzed monthly incident prescriptions for 5 drug classes: antidepressants, benzodiazepines, C-II stimulants, nonstimulant ADHD drugs, and buprenorphine MOUD products using the Uniform System of Classification (IQVIA) market definitions. These drug classes were examined to provide a broader overview of prescribing patterns across different behavioral health conditions and to observe both controlled and noncontrolled substances. For MOUD products, only buprenorphine products labeled for MOUD were analyzed; methadone for MOUD is not captured in the NPA. Prescriptions dispensed for drug products labeled for other indications (ie, analgesia, hypertension) were excluded. Only oral formulation products were assessed. Prescriptions written by veterinarians (<0.5% of prescriptions) or with missing patient age or sex (<0.001% of prescriptions) were also excluded.

We first explored descriptive patterns by reporting (1) the total number of and (2) percentage change in incident prescriptions dispensed by drug class, stratified by the 3 highest-volume prescriber specialties and patient age and sex, during the 2-year periods before (April 2018-March 2020) and during (April 2020-March 2022) the COVID-19 pandemic. For each drug class, the 3 highest-volume prescriber specialties were ranked based on the specialties that prescribed the highest number of incident prescriptions dispensed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additional prescription or patient characteristics, such as race or ethnicity, were not available in the data.

Statistical Analysis

Interrupted time-series analyses (ITSAs)16,17,18 were then used to examine whether changes over time were associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, both for initial level (immediate) changes and changes in trend (slope) in incident prescriptions fills before and during the pandemic (details in eMethods in Supplement 1), by drug class and drug. Data at a drug level are shown for the 2 most frequently dispensed drugs measured by total (prevalent) prescriptions dispensed within each drug class during our study period (eTable 1 in Supplement 1); buprenorphine-containing MOUD products were combined in our analyses. We used ordinary least squares regression with the Cochrane-Orcutt transformation and robust SEs to adjust for first-order serial autocorrelation. Sensitivity ITSAs were conducted to examine whether (1) exclusion of a transition period corresponding to the initial pandemic lockdown (March 2020 and April 2020) or (2) population adjustment changed the trend comparison before and after the study period. Outcomes with P values of ≤.05 (2-sided) were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed from March to July 2023 using Stata, version 17.0 (StataCorp).

Results

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics associated with incident prescriptions for the 5 drug classes dispensed during our study period. There were an estimated 51 500 321 incident prescriptions dispensed before the COVID-19 pandemic and 54 000 169 dispensed during the COVID-19 pandemic for the 5 drug classes examined. Comparing the prepandemic period to the pandemic period, incident prescriptions dispensed increased for antidepressants (10%, from 29 225 512 to 32 064 693), C-II stimulants (14%, from 5 214 415 to 5 923 747), and nonstimulant ADHD drugs (32%, from 1 027 215 to 1 354 721), whereas those for benzodiazepines (−9%, from 15 106 220 to 13 748 832) and buprenorphine MOUD (−2%, from 926 959 to 908 176) decreased (Table 1). Between the 2 periods, we focused on the largest changes in distribution by prescriber specialty and patient age or sex among drug classes. The largest increases among prescriber specialty were for incident prescriptions written by nurse practitioners across all drug classes, ranging from 7% (from 1 811 376 to 1 944 852; benzodiazepines) to 78% (from 157 578 to 280 925; buprenorphine MOUD). For patient age and sex, the largest changes in incident prescriptions dispensed within drug classes were for C-II stimulants and nonstimulant ADHD drugs with increases for patients aged 20 to 39 years (30% [from 1 887 017 to 2 455 706] and 81% [from 255 053 to 461 017], respectively) and female patients (25% [from 2 352 095 to 2 942 604] and 59% [from 395 678 to 630 678], respectively).

Table 1. Incident Prescriptionsa by Drug Class Stratified by Prescriber Specialtyb and Patient Age and Sex Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemicc.

| Drug class | No. (%) | Difference in incident Rx (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| April 2018-March 2020 | April 2020-March 2022 | ||

| Antidepressants, No. | 29 225 512 | 32 064 693 | 10 |

| Prescriber specialty | |||

| FP/GP/IM/OM | 12 875 277 (44) | 13 402 462 (42) | 4 |

| Nurse practitioner | 6 383 463 (22) | 8 216 638 (26) | 29 |

| Psychiatry | 3 278 143 (11) | 3 154 622 (10) | −4 |

| All others | 6 688 630 (23) | 7 290 970 (23) | 9 |

| Patient age, y | |||

| <20 | 2 893 817 (10) | 3 275 145 (10) | 13 |

| 20-39 | 9 566 779 (33) | 10 703 692 (33) | 12 |

| 40-59 | 8 990 413 (31) | 9 521 781 (30) | 6 |

| ≥60 | 7 774 497 (27) | 8 564 070 (27) | 10 |

| Patient sex | |||

| Female | 18 063 344 (62) | 20 160 120 (63) | 12 |

| Male | 11 162 169 (38) | 11 904 575 (37) | 7 |

| Benzodiazepines, No. | 15 106 220 | 13 748 832 | −9 |

| Prescriber specialty | |||

| FP/GP/IM/OM | 6 356 417 (42) | 5 668 860 (41) | −11 |

| Nurse practitioner | 1 811 376 (12) | 1 944 852 (14) | 7 |

| Physician assistant | 1 144 816 (8) | 1 074 560 (8) | −6 |

| All others | 5 793 609 (38) | 5 060 559 (37) | −13 |

| Patient age, y | |||

| <20 | 489 427 (3) | 400 553 (3) | −18 |

| 20-39 | 3 590 183 (24) | 3 069 000 (22) | −15 |

| 40-59 | 5 313 474 (35) | 4 699 568 (34) | −12 |

| ≥60 | 5 713 137 (38) | 5 579 710 (41) | −2 |

| Patient sex | |||

| Female | 9 402 596 (62) | 8 577 384 (62) | −9 |

| Male | 5 703 622 (38) | 5 171 451 (38) | −9 |

| C-II stimulants, No. | 5 214 415 | 5 923 747 | 14 |

| Prescriber specialty | |||

| FP/GP/IM/OM | 1 583 334 (30) | 1 738 237 (29) | 10 |

| Nurse practitioner | 854 200 (16) | 1 340 896 (23) | 57 |

| Psychiatry | 1 245 342 (24) | 1 238 244 (21) | −1 |

| All others | 1 531 538 (29) | 1 606 373 (27) | 5 |

| Patient age, y | |||

| <20 | 2 174 743 (42) | 2 142 941 (36) | −1 |

| 20-39 | 1 887 017 (36) | 2 455 706 (41) | 30 |

| 40-59 | 895 979 (17) | 1 048 679 (18) | 17 |

| ≥60 | 256 677 (5) | 276 417 (5) | 8 |

| Patient sex | |||

| Female | 2 352 095 (45) | 2 942 604 (50) | 25 |

| Male | 2 862 323 (55) | 2 981 141 (50) | 4 |

| Nonstimulant ADHD, No. | 1 027 215 | 1 354 721 | 32 |

| Prescriber specialty | |||

| Nurse practitioner | 264 820 (26) | 459 619 (34) | 74 |

| Psychiatry | 289 063 (28) | 323 291 (24) | 12 |

| FP/GP/IM/OM | 187 959 (18) | 237 887 (18) | 27 |

| All others | 285 375 (28) | 333 921 (25) | 17 |

| Patient age, y | |||

| <20 | 613 011 (60) | 658 846 (49) | 7 |

| 20-39 | 255 053 (25) | 461 017 (34) | 81 |

| 40-59 | 126 363 (12) | 189 130 (14) | 50 |

| ≥60 | 32 789 (3) | 45 733 (3) | 39 |

| Patient sex | |||

| Female | 395 678 (39) | 630 678 (47) | 59 |

| Male | 631 538 (61) | 724 040 (53) | 15 |

| Buprenorphine MOUD,d No. | 926 959 | 908 176 | −2 |

| Prescriber specialty | |||

| FP/GP/IM/OM | 402 687 (43) | 313 922 (35) | −22 |

| Nurse practitioner | 157 578 (17) | 280 925 (31) | 78 |

| Psychiatry | 114 028 (12) | 77 415 (9) | −32 |

| All others | 252 666 (27) | 235 912 (26) | −7 |

| Patient age, y | |||

| <20 | 4277 (0) | 5522 (1) | 29 |

| 20-39 | 538 214 (58) | 500 127 (55) | −7 |

| 40-59 | 304 149 (33) | 315 505 (35) | 4 |

| ≥60 | 80 319 (9) | 87 022 (10) | 8 |

| Patient sex | |||

| Female | 374 312 (40) | 359 916 (40) | −4 |

| Male | 552 647 (60) | 548 260 (60) | −1 |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; C-II, Schedule II; ER, extended release; FP, family practice; GP, general practice; IM, internal medicine; OM, osteopathic medicine; MOUD, medications for opioid use disorder; PEDS IM, pediatric/internal medicine specialty; Rx, prescription.

Incident prescription is measured by new therapy start prescriptions, defined as prescriptions for a drug dispensed to patients with no prior prescription dispensed for a drug within the same drug class (eg, USC 64300 Antidepressants) in the previous 12 months.

The 3 highest volume prescriber specialties were ranked based on which specialties wrote the highest number of incident prescriptions dispensed during April 2020 to March 2022. The prescriber specialty category “all others” combines incident prescriptions dispensed written by the remaining prescriber specialties.

Data source: IQVIA National Prescription Audit. April 2018 to March 2022. Extracted March 2023. Limited to oral formulations; other formulations (eg, injection, implants) were not included. Nationally estimated data are provided for drug products labeled for mental health conditions, (eg, guanfacine ER products labeled for ADHD, buprenorphine-containing products labeled for OUD treatment). Prescriptions written by veterinary medicine, and prescriptions dispensed for unspecified patient age or sex were excluded. Except where specified, drugs include long-acting and short-acting formulations. Data are projected so total number of incident prescriptions stratified by category may vary from total unstratified incident prescriptions data. Percentages are rounded to the nearest 1%; percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Buprenorphine and methadone are approved for MOUD; methadone was not included because methadone for OUD is only available from opioid treatment programs, only methadone for analgesia is available through pharmacies. Only buprenorphine MOUD products (buprenorphine and buprenorphine/naloxone) labeled for the treatment of OUD were included in both drug class and drug level for our analyses.

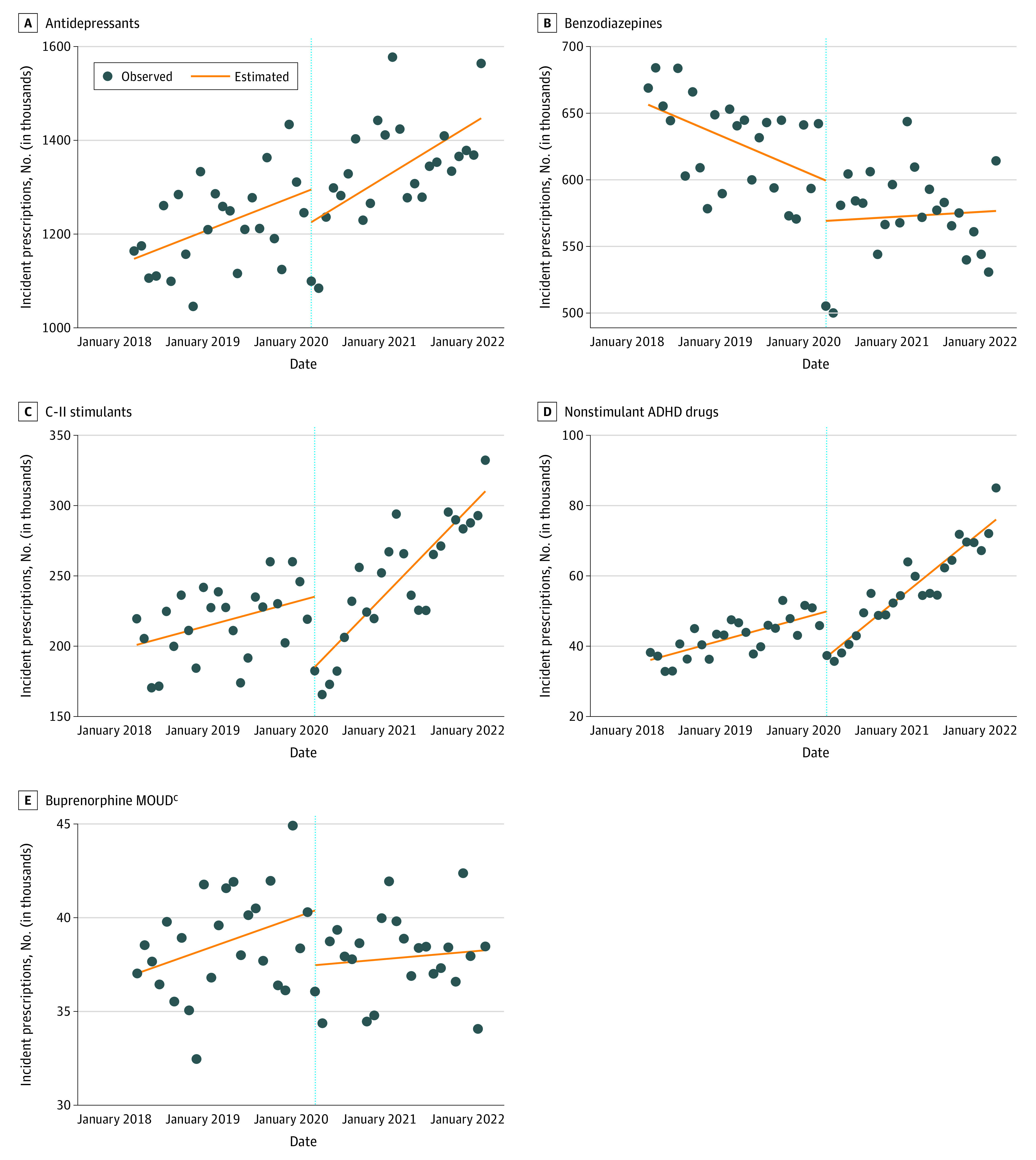

The ITSAs show that 1.1 million incident prescriptions were initially dispensed (intercept) for antidepressants in April 2018 (Figure and Table 2). There was an increasing trend (slope) before the COVID-19 pandemic (6152 prescriptions per month, 95% CI, 782-11 523) that continued during the pandemic (9629 prescriptions per month, 95% CI, 3864-5393). At a drug level, 202 643 and 172 893 incident prescriptions were initially dispensed (intercept) in April 2018 for sertraline and escitalopram, respectively. For sertraline, there was an increasing trend (slope) before the COVID-19 pandemic (1631 prescriptions per month, 95% CI, 686-2575) that continued during the pandemic (1874 prescriptions per month, 95% CI, 704-3044). For escitalopram, there was an increasing trend before the COVID-19 pandemic (1715 prescriptions per month, 95% CI, 873-2558) that continued during the pandemic (2103 prescriptions per month, 95% CI, 887-3319). However, the changes in levels and trends were not significant for antidepressants as a class or for sertraline and escitalopram.

Figure. Interrupted Time-Series Analysis of Incident Prescriptionsa Dispensed for Selected Drug Classes, April 2018 to March 2022b.

ADHD indicates attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; C-II, Schedule II; MOUD, medications for opioid use disorder.

aIncident prescription is measured by new therapy start prescriptions, defined as prescriptions for a drug dispensed to patients with no prior prescription dispensed for a drug within the same drug class (eg, USC 64300 Antidepressants) in the previous 12 months.

bData Source: IQVIA National Prescription Audit. April 2018 to March 2022. Extracted March 2023. Limited to oral formulations; other formulations (eg, injection, implants) were not included. Nationally estimated data are provided for drug products labeled for mental health conditions (eg, guanfacine extended-release products labeled for ADHD, buprenorphine products labeled for MOUD treatment). Prescriptions written by veterinary medicine and prescriptions dispensed for unspecified patient age or sex were excluded.

cBuprenorphine and methadone are approved for MOUD; methadone was not included because methadone for OUD is only available from opioid treatment programs, only methadone for analgesia is available through pharmacies. Only buprenorphine MOUD products (buprenorphine and buprenorphine/naloxone) labeled for the treatment of OUD were included in our analyses.

Table 2. Interrupted Time-Series Regression Analyses of Monthly Incidenta Prescriptions Dispensed (in Thousands) for Selected Drug Classes and Drugs, Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemicb.

| Drug class or drug | Intercept (95% CI) (April 2018) | Pre–COVID-19 pandemic (April 2018-March 2020) | Level change associated with COVID-19 pandemic (April 2020) | During COVID-19 pandemic (April 2020-March 2022) | Slope change associated with COVID-19 pandemic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope (95% CI)c | P value | Level change (95% CI) | P value | Slope (95% CI)c | P value | Slope change (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Antidepressants | 1147.39 (1083.11 to 1211.68) | 6.15 (0.78 to 11.52) | .03d | −69.65 (−190.49 to 51.20) | .25 | 9.63 (3.86 to 5.39) | .002d | 3.48 (−4.41 to 11.36) | .38 |

| Sertraline | 202.64 (191.04 to 214.25) | 1.63 (0.69 to 2.58) | .001d | −13.43 (−36.14 to 9.28) | .24 | 1.87 (0.70 to 3.04) | .002d | 0.24 (−1.26 to 1.75) | .75 |

| Escitalopram | 172.89 (162.86 to 182.93) | 1.72 (0.87 to 2.56) | <.001d | −6.93 (−29.00 to 15.14) | .53 | 2.10 (0.89 to 3.32) | .001d | 0.39 (−1.09 to 1.86) | .60 |

| Benzodiazepines | 656.51 (634.32 to 678.69) | −2.37 (−4.08 to −0.67) | .008d | −30.31 (−72.50 to 11.87) | .16 | 0.33 (−2.06 to 2.71) | .79 | 2.70 (−0.24 to 5.64) | .07 |

| Alprazolam | 246.58 (235.41 to 257.74) | −0.67 (−1.78 to 0.43) | .23 | −11.69 (−32.02 to 8.65) | .25 | −0.38 (−1.10 to 0.35) | .30 | 0.30 (−1.02 to 1.61) | .65 |

| Lorazepam | 200.24 (193.79 to 206.69) | −0.37 (−0.93 to 0.18) | .19 | −4.81 (−16.20 to 6.58) | .40 | 0.07 (−0.48 to 0.61) | .80 | 0.44 (−0.33 to 1.21) | .26 |

| C-II stimulant | 200.88 (175.42 to 226.34) | 1.43 (−0.45 to 3.31) | .13 | −50.04 (−80.20 to −19.89) | .002d | 5.43 (4.16 to 6.71) | <.001d | 4.01 (1.59 to 6.42) | .002d |

| Amphetamine- dextroamphetamine |

100.14 (91.11 to 109.18) | 0.59 (−0.09 to 1.28) | .09 | −17.83 (−29.94 to −5.72) | .005d | 2.88 (2.39 to 3.37) | <.001d | 2.29 (1.42 to 3.15) | <.001d |

| Methylphenidate | 50.75 (41.31 to 60.19) | 0.50 (−0.18 to 1.17) | .14 | −16.62 (−26.06 to −7.18) | .001d | 1.44 (0.95 to 1.93) | <.001d | 0.94 (0.02 to 1.87) | .046d |

| Nonstimulant ADHD drugs | 36.15 (32.81 to 39.49) | 0.58 (0.32 to 0.83) | <.001d | −12.88 (−17.76 to −8.00) | <.001d | 1.70 (1.39 to 2.01) | <.001d | 1.12 (0.71 to 1.53) | <.001d |

| Atomoxetine | 20.57 (19.05 to 22.09) | 0.32 (0.20 to 0.44) | <.001d | −5.87 (−8.47 to −3.26) | <.001d | 1.11 (0.94 to 1.28) | <.001d | 0.79 (0.58 to 1.00) | <.001d |

| Guanfacine ER | 14.67 (12.57 to 16.77) | 0.23 (0.08 to 0.39) | .004d | −5.78 (−8.24 to −3.33) | <.001d | 0.41 (0.26 to 0.55) | <.001d | 0.17 (−0.06 to 0.40) | .14 |

| Buprenorphine MOUDe | 37.01 (35.49 to 38.53) | 0.14 (0.02 to 0.26) | .03d | −2.92 (−5.51 to −0.32) | .03d | 0.04 (−0.09 to 0.16) | .58 | −0.11 (−0.28 to 0.07) | .23 |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; C-II, Schedule II; ER, extended release; MOUD, medications for opioid use disorder.

Incident prescription is measured by new therapy start prescriptions, defined as prescriptions for a drug dispensed to patients with no prior prescription dispensed for a drug within the same drug class (eg, USC 64300 Antidepressants) in the previous 12 months.

Data Source: IQVIA National Prescription Audit. April 2018 to March 2022. Extracted March 2023. Limited to oral formulations; other formulations (eg, injection, implants) were not included. Nationally estimated data are provided for drug products labeled for mental health conditions, (eg, guanfacine ER products labeled for ADHD, buprenorphine-containing products labeled for OUD treatment). Prescriptions written by veterinary medicine, and prescriptions dispensed for unspecified patient age or sex were excluded. Except where specified, drugs include long-acting and short-acting formulations.

Slope coefficient is the estimated number of increases in New Therapy Start (IQVIA) prescription in thousands per month; we used Prais-Winsten regression with the Cochrane-Orcutt transformation and robust SEs to adjust for first-order serial autocorrelation. The COVID-19 outbreak in the US constitutes a national emergency, beginning March 1, 2020.

Indicates the results are significant at 95% level.

Buprenorphine-containing products and methadone are approved for MOUD; methadone was not included as methadone for OUD is only available from opioid treatment programs, and only methadone for analgesia is available through pharmacies. Only buprenorphine MOUD products (buprenorphine and buprenorphine/naloxone) labeled for the treatment of OUD were included in this drug class for our analyses.

For benzodiazepines, 656 506 incident prescriptions were initially dispensed (intercept). There was a decreasing trend before the COVID-19 pandemic (slope: −2373 prescriptions per month, 95% CI, −4079 to −666) that flattened during the pandemic. At a drug level, 246 577 and 200 236 incident prescriptions were initially dispensed (intercept) in April 2018 for alprazolam and lorazepam, respectively. However, there were no other significant trends or changes in level or trends for benzodiazepines as a class or for alprazolam and lorazepam.

For C-II stimulants, 200 879 incident prescriptions were initially dispensed (intercept). Although trends (slope) were flat before the COVID-19 pandemic, dispensing rates changed during the pandemic to an increasing trend of 5434 prescriptions per month (95% CI, 4158-6710). Both changes in level (−50 044 prescriptions; 95% CI, −80 202 to −19 886) and trends (slope change: 4007 prescriptions per month, 95% CI, 1592-6422) were significant. At a drug level, the initial number (intercept) of incident prescriptions dispensed for amphetamine-dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate were 100 140 and 50 748, respectively. For amphetamine-dextroamphetamine, trends (slope) appear flat before the COVID-19 pandemic, then increased to 2878 prescriptions per month (95% CI, 2385-3370) during the pandemic. Both changes in level (−17 828 prescriptions; 95% CI, −29 936 to −5720) and trends (slope change: 2285 prescriptions per month, 95% CI, 1422-3149) were significant. For methylphenidate, trends (slope) appear flat before the COVID-19 pandemic, then increased to 1436 prescriptions per month, (95% CI, 946-1926) during the pandemic. Both changes in level (−16 623 prescriptions, 95% CI, −26 064 to −7181) and trends (slope change: 941 prescriptions per month, 95% CI, 16-1866) were significant.

For nonstimulant ADHD drugs, 36 152 incident prescriptions were initially dispensed (intercept). Before the COVID-19 pandemic, there was an increasing trend (slope) of 576 prescriptions per month (95% CI, 319-833) that further accelerated during the pandemic to 1695 prescriptions per month (95% CI, 1386-2005), significantly exceeding the prepandemic trend (slope change: 1120 prescriptions per month, 95% CI, 706-1533). There was an immediate drop (level change) in dispensing associated with the outbreak of COVID-19 (−12 876 prescriptions; 95% CI, −17 756 to −7996). At a drug level, 20 568 and 14 668 incident prescriptions were initially dispensed (intercept) for atomoxetine and guanfacine extended release, respectively. For atomoxetine, there was an increasing trend of 319 prescriptions per month before the COVID-19 pandemic (95% CI, 197-440) that further accelerated during the pandemic (1106 prescriptions per month, 95% CI, 937-1275), exceeding the prepandemic trend. Both changes in level (−5866 prescriptions; 95% CI, −8469 to −3264) and trends (slope change: 787 prescriptions per month, 95% CI, 576-998) were significant. For guanfacine extended release, there was an increasing trend before the COVID-19 pandemic (233 prescriptions per month, 95% CI, 77-388) that continued during the pandemic (407 prescriptions per month, 95% CI, 262-551). Although the level change was significant (−5781 prescriptions; 95% CI, −8237 to −3326), the change in trends (slopes) was not significant for guanfacine extended release.

For buprenorphine MOUD, 37 012 incident prescriptions were initially dispensed (intercept) in April 2018. There was an increasing trend before the COVID-19 pandemic (140 prescriptions per month; 95% CI, 16-263) that flattened during the pandemic. Although the immediate drop in incident prescriptions was found to be associated with the outbreak of the pandemic (−2915 prescriptions; 95% CI, −5513 to −318), the change in trends (slope change) was not significant.

Sensitivity analyses excluding data from March and April 2020 (eTable 2 in Supplement 1) showed that changes in trend were largely consistent with the primary analyses, with a few exceptions. There were decreasing trends for alprazolam and lorazepam before the COVID-19 pandemic. For alprazolam and methylphenidate, the change in trends of incident prescriptions dispensed between the COVID-19 prepandemic and postpandemic periods were significant and no longer significant, respectively. There were no substantial differences in results during the COVID-19 period. Additional sensitivity analyses that accounted for population changes across years generated similar conclusions and no meaningful differences in trends were found.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, results showed that the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with differential changes in incident prescription trends for medications used across various behavioral health conditions in the US. Although trends in incident prescriptions dispensed for antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and buprenorphine MOUD did not significantly change, dispensing for C-II stimulant and nonstimulant ADHD medications significantly increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, exceeding prepandemic trends, most notably among young adults and women. We also observed an initial drop in dispensing at the onset of the pandemic across all drugs examined, significantly for C-II stimulants, nonstimulant ADHD drugs, and buprenorphine MOUD. This initial drop, particularly for buprenorphine MOUD, reinforces early concerns of pandemic-related disruptions to health care access and supports the need for prescribing flexibilities for controlled substances implemented early in the COVID-19 pandemic.7,8,19

Our results show that before the COVID-19 pandemic, there was an increasing trend in incident antidepressant dispensing and a decreasing trend for benzodiazepines. During the pandemic, incident antidepressant dispensing continued to increase, whereas the decline in incident benzodiazepine dispensing attenuated slightly. However, the slope changes were not significant for either drug class. These findings suggest that pandemic-related factors may not have had significant, long-lasting impacts on new medication treatment for depression and anxiety. This is consistent with studies among adolescents and young adults, which found an initial increase in depression and anxiety symptoms at the onset of the pandemic, followed by a decrease and/or a plateau in symptoms during the pandemic as COVID-19 infection rates declined.20,21 For benzodiazepines, public health concerns over abuse, misuse, and addiction, alone and when coprescribed with opioids, may have contributed to the observed trends.22,23

For buprenorphine MOUD, there was an initial drop in incident prescriptions in March 2020. However, trends did not change, consistent with a prior study.24 One potential explanation for the lack of change in trends is that telemedicine prescribing flexibilities may have allowed clinicians to continue to diagnose and start treatment for OUD. Although we did not directly study the impact of telemedicine in our analyses, other studies have found that telemedicine flexibilities and other interventions to expand access to MOUD during the COVID-19 pandemic were used by Medicare recipients25 and commercially insured patients to initiate OUD-related care and were associated with improved retention in care, reductions in overdose-related outcomes, and improved patient engagement.14 However, in another study26 conducted surveying clinician use of and comfort level using telemedicine, more than half of clinicians surveyed (55.8% of 602 clinicians), reported being somewhat to very uncomfortable initiating care in new patients with OUD via video visits. Potential prescriber discomfort with medication initiation via telemedicine as well as other barriers to treatment may have contributed to the flattened trend during the COVID-19 pandemic.27

The lack of significant changes in the trends of incident prescriptions dispensed for antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and buprenorphine MOUD during the COVID-19 pandemic suggests that a unique set of drivers may have contributed to the differential use of ADHD medications. Media reported concerns of high levels of prescribing for C-II stimulants due to marketing and prescribing practices associated with some telemedicine-only companies.28,29 Media reports also noted that certain telemedicine services used social media to advertise treatments for behavioral health conditions, such as ADHD and eating disorders.30 Consistent with another study based on any prescription use in a commercially insured population,12 our study found that the largest increases in new use of ADHD medications appeared to be in adults aged 20 to 39 years and female patients. Historically, ADHD has predominantly been diagnosed and treated in children and adolescents, particularly young male patients.31 Recently, ADHD has increasingly been diagnosed and treated in both adult and female patients, but there are limited ADHD guidelines developed for adults.12,32,33 We further assessed changes for the top 2 drugs dispensed by drug class and found that amphetamine-dextroamphetamine increased substantially more than methylphenidate, whereas among nonstimulant ADHD medications, trends in incident use of atomoxetine increased but did not change for guanfacine extended release. Current ADHD treatment guidelines include some drug-specific considerations. For example, methylphenidate is recommended when medication treatment is needed for young pediatric patients, whereas atomoxetine has a boxed warning for suicidal ideation for children and adolescents.34 However, the drivers for increased use for amphetamine-dextroamphetamine are not clear. Increased awareness in underdiagnosed populations,31 increased needs due to COVID-19 pandemic-related stressors,5 and reduced barriers to access10 may have helped to uncover preexisting unmet needs as well as potential overprescribing. However, dispensed prescription data alone cannot be used to determine clinical appropriateness; further research to inform ADHD diagnosis and treatment appropriateness for adults including sex-related considerations, as well as exploration of how marketing and prescribing practices evolved under pandemic-related prescribing flexibilities is needed.

Nurse practitioners had the largest increases in prescribing incident prescriptions across the 5 drug classes. This is consistent with a study that found that behavioral health visits among Medicare beneficiaries conducted by psychiatric behavioral health nurse practitioners increased by 162%, whereas those by psychiatrists decreased by 6% from 2011 to 2019.35 Our study, based on incident prescription data, suggests an increasing contribution of nurse practitioners initiating medication treatment of behavioral health conditions compared with other health care practitioners. As the types of practitioners in behavioral health care expand, it is important to engage different types of health care professionals when creating educational programs, prescribing guidelines, or policies aimed to improve the provision of behavioral health care.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study’s main strengths include the use of comprehensive, national-level outpatient incident prescription dispensing data across all payment types (commercial insurance, Medicare/Medicaid, and cash) across 5 drug classes. This study complements other research based on patient-level, often claims-based, studies that are limited to health care activity (eg, prescription claims) covered by a specific payor (eg, Medicaid) or in specific populations.12,19,35,36 Additionally, by focusing on incident prescriptions, we provide insight into care for patients who may be newly diagnosed and treated, as opposed to assessing prevalent use, which includes retention to medications for patients already on treatment, thus revealing changes in prescribing patterns for various conditions before and during the pandemic.

Our study has several limitations. First, because our definition of incident prescriptions was based on the absence of prescription activity for a given drug class during the previous 12 months, patients with prescriptions dispensed from pharmacies outside the data source may be misclassified as incident. However, because the data source we used captures more than 94% of US prescription activity and links unique patient activity across pharmacies and payment methods, it is unlikely that there is substantial overestimation of incident use. Second, no causal relationships between drug utilization patterns and effects of the COVID-19 pandemic could be determined from our analyses. Drivers behind prescribing (eg, increased medical need, the impact of marketing or telemedicine) are challenging to discern; for example, clinical information, such as indication, is not available in prescription transaction data. Telemedicine health care encounters increased during the COVID-19 pandemic,9 but the lack of telemedicine identifiers on dispensed prescription data precludes us from analyzing telemedicine’s impact on prescription use.37 Previous studies have used claims-based data to link dispensed prescription claims with preceding encounter claims to understand telemedicine prescribing trends because some encounters may be billed as telemedicine visits.38 However, self-pay encounters, reported as more common for behavioral health visits than for primary care visits,39,40 may be largely missing in claims-based analyses, leading to missing telemedicine prescribing data linked to dispensed prescription claims. Third, increased demand has been cited to contribute to shortages of sertraline41; shortages of amphetamine-dextroamphetamine were also announced in October 2022.42 Because dispensed prescription data can only reflect dispensing availability, it may not be a sufficient measure of demand or medical need during periods of drug shortage. Lastly, additional information, such as race, was not available in the data.

Conclusions

Results of this cross-sectional study showed that during the COVID-19 pandemic, US national trends in the incident prescriptions dispensed for C-II stimulant and nonstimulant ADHD medications significantly increased, exceeding prepandemic trends, particularly in young adult and female patients, whereas trends for antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and buprenorphine for OUD did not significantly change. The differential changes during the pandemic in incident prescription trends for ADHD medications, particularly for C-II stimulants, underscore the need for robust policies to address unmet needs while balancing public health concerns. Future research should prioritize clinical ADHD guideline development, such as adult-focused guidelines, to define treatment appropriateness.

eMethods. Detailed Methodology

eTable 1. Total (Prevalent) Prescriptions Dispensed by Selected USC Drug Classes and Drugs, April 2018-March 2022

eTable 2. Interrupted Time-Series Regression Sensitivity Analyses of Monthly Incident Prescriptions Dispensed (in Thousands) for Selected Drug Classes and Drugs, Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Data Sharing Statement.

References

- 1.Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):510-512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Penninx BWJH, Benros ME, Klein RS, Vinkers CH. How COVID-19 shaped mental health: from infection to pandemic effects. Nat Med. 2022;28(10):2027-2037. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-02028-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collaborators CMD; COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators . Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;398(10312):1700-1712. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garnett MF, Curtin SC. Suicide mortality in the US, 2001-2021. NCHS Data Brief. 2023;(464):1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rogers MA, MacLean J. ADHD symptoms increased during the COVID-19 pandemic: a meta-analysis. J Atten Disord. 2023;27(8):800-811. doi: 10.1177/10870547231158750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Center for Health Statistics . Mortality multiple cause of death. Accessed November 14, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/mortality_public_use_data.htm

- 7.World Health Organization . The impact of COVID-19 on mental, neurological, and substance use services. Accessed May 22, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/978924012455

- 8.Huskamp HA, Busch AB, Uscher-Pines L, Barnett ML, Riedel L, Mehrotra A. Treatment of opioid use disorder among commercially insured patients in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324(23):2440-2442. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.21512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koonin LM, Hoots B, Tsang CA, et al. Trends in the use of telehealth during the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic—US, January-March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(43):1595-1599. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6943a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDermott WT. DEA registrant letter. Accessed September 21, 2023. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/GDP/(DEA-DC-018)(DEA067)%20DEA%20state%20reciprocity%20(final)(Signed).pdf

- 11.Prevoznik TW. DEA qualifying practitioners. Accessed September 21, 2023. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/GDP/(DEA-DC-022)(DEA068)%20DEA%20SAMHSA%20buprenorphine%20telemedicine%20%20(Final)%20+Esign.pdf

- 12.Danielson ML, Bohm MK, Newsome K, et al. Trends in stimulant prescription fills among commercially insured children and adults—US, 2016-2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(13):327-332. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7213a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burrell TD, Sheu YS, Kim S, et al. COVID-19 and adolescent outpatient mental health service utilization. Acad Pediatr. Published online June 9, 2023. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2023.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen B, Zhao C, Bailly E, Chi W. Telehealth Initiation of buprenorphine for opioid use disorder: patient characteristics and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. Published online September 5, 2023. doi: 10.1007/s11606-023-08383-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.IQVIA. Home page. Accessed June 30, 2023. http://www.iqvia.com.

- 16.Jandoc R, Burden AM, Mamdani M, Lévesque LE, Cadarette SM. Interrupted time series analysis in drug utilization research is increasing: systematic review and recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(8):950-956. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(1):348-355. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ewusie JE, Blondal E, Soobiah C, et al. Methods, applications, interpretations and challenges of interrupted time series (ITS) data: protocol for a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(6):e016018. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whaley CM, Pera MF, Cantor J, et al. Changes in health services use among commercially insured US populations during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2024984-e2024984. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.24984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graupensperger S, Calhoun BH, Fleming C, Rhew IC, Lee CM. Mental health and well-being trends through the first year-and-a-half of the COVID-19 pandemic: results from a longitudinal study of young adults in the USA. Prev Sci. 2022;23(6):853-864. doi: 10.1007/s11121-022-01382-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hawes MT, Szenczy AK, Olino TM, Nelson BD, Klein DN. Trajectories of depression, anxiety and pandemic experiences; a longitudinal study of youth in New York during the spring-summer of 2020. Psychiatry Res. 2021;298:113778. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—US, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624-1645. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.US Food and Drug Administration . FDA requiring boxed warning updated to improve safe use of benzodiazepine drug class. Accessed May 22, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-requiring-boxed-warning-updated-improve-safe-use-benzodiazepine-drug-class

- 24.Chua KP, Nguyen TD, Zhang J, Conti RM, Lagisetty P, Bohnert AS. Trends in buprenorphine initiation and retention in the US, 2016-2022. JAMA. 2023;329(16):1402-1404. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.1207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones CM, Shoff C, Blanco C, Losby JL, Ling SM, Compton WM. Association of receipt of opioid use disorder–related telehealth services and medications for opioid use disorder with fatal drug overdoses among Medicare beneficiaries before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80(5):508-514. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.0310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huskamp HA, Riedel L, Uscher-Pines L, et al. Initiating opioid use disorder medication via telemedicine during COVID-19: implications for proposed reforms to the Ryan Haight Act. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(1):162-167. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07174-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bremer W, Plaisance K, Walker D, et al. Barriers to opioid use disorder treatment: a comparison of self-reported information from social media with barriers found in literature. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1141093. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1141093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Drug Enforcement Administration . DEA serves order to show cause on Truepill Pharmacy for its involvement in the unlawful dispensing of prescription stimulants. Accessed September 21, 2023. https://www.dea.gov/press-releases/2022/12/15/dea-serves-order-show-cause-truepill-pharmacy-its-involvement-unlawful

- 29.Winkler R. ADHD specialists worry stimulant drugs are overprescribed, push for treatment guidelines. Accessed March 4, 2023. https://www.wsj.com/articles/adhd-specialists-plan-new-u-s-guidelines-to-curb-irresponsible-prescriptions-11662033613

- 30.Forbes . Instagram pulls ads by mental health startup Cerebral for violating its rules. Accessed June 30, 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/katiejennings/2022/01/21/instagram-says-mental-health-startup-cerebral-violated-its-rules-with-adhd-ads-showing-disordered-eating/?sh=347b758d7c6c.

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Data and statistics about ADHD. Accessed June 30, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/data.html

- 32.Board AR, Guy G, Jones CM, Hoots B. Trends in stimulant dispensing by age, sex, state of residence, and prescriber specialty—US, 2014-2019. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;217:108297. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolraich ML, Hagan JF Jr, Allan C, et al. ; Subcommittee on Children and Adolescents With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactive Disorder . Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4):e20192528. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Post RE, Kurlansik SL. Diagnosis and management of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85(9):890-896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cai A, Mehrotra A, Germack HD, Busch AB, Huskamp HA, Barnett ML. Trends in mental health care delivery by psychiatrists and nurse practitioners in Medicare, 2011-2019: study examines trends in mental health care delivery by psychiatrists and nurse practitioners in Medicare. Health Aff. 2022;41(9):1222-1230. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson FA, Rampa S, Trout KE, Stimpson JP. Telehealth delivery of mental health services: an analysis of private insurance claims data in the US. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(12):1303-1306. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201700017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Federal Register . Telemedicine prescribing of controlled substances when the practitioner and the patient have not had a prior in-person medical evaluation. Accessed May 22, 2023. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/03/01/2023-04248/telemedicine-prescribing-of-controlled-substances-when-the-practitioner-and-the-patient-have-not-had

- 38.Barsky BA, Busch AB, Patel SY, Mehrotra A, Huskamp HA. Use of telemedicine for buprenorphine inductions in patients with commercial insurance or Medicare advantage. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(1):e2142531-e2142531. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.42531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benjenk I, Chen J. Trends in self-payment for outpatient psychiatrist visits. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(12):1305-1307. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.2072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lagisetty PA, Ross R, Bohnert A, Clay M, Maust DT. Buprenorphine treatment divide by race/ethnicity and payment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(9):979-981. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.US Food and Drug Administration . FDA drug shortages. Accessed May 22, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/drugshortages/default.cfm

- 42.US Food and Drug Administration . FDA announces shortage of Adderall. Accessed May 22, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-announces-shortage-adderall

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Detailed Methodology

eTable 1. Total (Prevalent) Prescriptions Dispensed by Selected USC Drug Classes and Drugs, April 2018-March 2022

eTable 2. Interrupted Time-Series Regression Sensitivity Analyses of Monthly Incident Prescriptions Dispensed (in Thousands) for Selected Drug Classes and Drugs, Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Data Sharing Statement.