Abstract

Objective:

To examine genetic influence on the risk of elevations in liver function tests (AST and ALT) among patients using low-dose methotrexate (LD-MTX).

Methods:

We examined data from the LD-MTX arm of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial conducted among subjects without rheumatic disease. Genome wide association studies (GWAS) were performed in subjects of European ancestry to test the association between single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and the log transformed maximum values of AST, ALT, and dichotomized outcome with AST or ALT > 2 times upper limit of normal (ULN). The association between variants in MTX metabolism candidate genes and the outcomes was also tested. Furthermore, associations between a drug induced liver injury (DILI) weighted genetic risk score (wGRS) and the outcomes were tested, combining 10 SNPs and 11 classical HLA alleles associated with DILI.

Results:

In genome-wide genetic analyses among 1,429 subjects of European ancestry who were randomized to receive LD-MTX, two SNPs reached genome wide significance for association with log transformed maximum ALT. We observed associations between established candidate genes in MTX pharmacogenetics and log transformed maximum AST and ALT, as well as in dichotomized outcome with AST or ALT > 2 x ULN. There was no association between DILI wGRS or candidate variants and AST, ALT, or DILI response.

Conclusions:

Modest evidence was observed that common variants affected AST and ALT levels in subjects of European ancestry on LD-MTX, but this genetic effect is not useful as a clinical predictor of MTX toxicity.

Keywords: Low dose methotrexate, Drug induced liver injury, Genome wide association study, Genetic risk score, Pharmacogenetics

Introduction

Low-dose methotrexate (LD-MTX) is the first-line drug to treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and is commonly used for other autoimmune diseases [1,2]. Although the effectiveness of LD-MTX has been demonstrated in randomized controlled trials, discontinuation of treatment due to adverse events is reported in approximately one third of patients [3]. Drug induced liver injury (DILI) is one of the main reasons for treatment discontinuation [4]. The liver enzymes alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) are the most commonly used laboratory tests as indicators of hepatocellular injury [5], which can occur in the setting of LD-MTX.

The recent 2015 ACR guidelines to monitor low-dose MTX in RA included blood tests of liver function every 2–4 weeks for the first 3 months, every 8–12 weeks for 3–6 months, and every 12 weeks after 6 months [6]. The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) established the Drug-induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN) in 1994 to collect data on DILI as a spectrum ranging from elevated liver tests to cirrhosis, https://dilin.org/. For the present study, we focused on elevated liver tests as the earliest sign of hepatocellular injury.

Identifying patients who are at higher risk to develop DILI prior to treatment could be of clinical and economic benefit to patients. Patient and drug-related factors may play a role in the pathogenesis of DILI, including age, gender, underlying diseases, as well as daily dose of LD-MTX, drug metabolism, and drug interactions [7]. Investigation of genetic variants as predictors of DILI in rheumatic disease patients treated with LD-MTX has focused on the candidate genes that encode enzymes in MTX metabolism pathways [8-10]. More recently, genome wide association studies (GWAS) investigating DILI from drug treatments including LD-MTX have been performed [11-14], leading to the discovery of significant associations with human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles and a PTPN22 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) that associated with all-cause DILI [15]. GWAS has been used to discover loci associated with circulating ALT and AST levels [16]. However, no GWAS of MTX toxicity measured by level of AST has been published to date.

Candidate gene studies have been used to gain insight into MTX’s mechanism of action in rheumatic disease and to discover genetic predictors of liver toxicity. While LD-MTX’s mechanism for immunomodulation remains unclear, it is known to inhibit several folate-dependent enzymes, including ATIC and DHFR [17]. Attention has been focused on genetic polymorphisms within the folate pathway, adenosine pathway, as well as genes involved in MTX metabolism [18]. In the current analyses, we focused on liver test results among a large group of subjects without rheumatic disease starting LD-MTX as part of the Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial (CIRT) [19]. We performed GWAS on ALT and AST levels from the subjects in the LD-MTX treatment arm, as well as a GWAS on a composite outcome of either ALT or AST exceeding 2 x upper limit of normal (ULN) (modified Hy’s law) [5]. We examined the association between a DILI weighted genetic risk score (wGRS), comprised of SNPs from DILI GWAS, candidate genes in folate and adenosine pathways and abnormal liver tests in a study sample randomized to LD-MTX.

Methods

Study population and design

CIRT was a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial for cardiovascular prevention with LD-MTX that was halted prematurely because of a lack of efficacy [19]. The trial enrolled subjects starting in 2013 and study drug terminated in April 2018; final safety visits were conducted in December 2018. Based on pre-specified safety analyses [20], adverse events (AEs) of interest were blindly adjudicated as part of the conduct of the trial. The study sample for this analysis was subjects randomized to receive LD-MTX or placebo. Potentially eligible patients for CIRT had a known history of myocardial infarction or multi-vessel coronary artery disease, diabetes and/or metabolic syndrome, but persons were excluded if they had known systemic rheumatic disease. Other relevant exclusions included chronic infections and history of hepatitis B or C. Subjects were required to complete a 5–8-week active run-in phase using oral LD-MTX 10–15 mg/week with folic acid 1 mg the other six days. Those who tolerated LD-MTX in the active run-in were randomly assigned to LD-MTX or placebo. Safety and/or drug tolerance were defined as no clinically important symptoms, and laboratory values maintained in the normal range, including WBC, hematocrit, AST, ALT, platelet count, albumin and creatinine; more detailed info can be found in the primary CIRT publication [19]. The initial weekly dose of LD-MTX or placebo after randomization was 15 mg/week. After 16 weeks, if the complete blood count, creatinine, AST and ALT were in the normal range, then the dosage was increased to 20 mg per week per details described in a prior manuscript [19]. The CIRT trial was approved by all relevant IRBs including Mass General Brigham IRB, Copernicus Group IRB, and IRB Services of Canada. All patients included in the current analyses gave written informed consent for secondary genetic analyses.

Hepatic outcomes

Laboratory assessments were conducted at study visits every 4–12 weeks. Patients treated with LD-MTX temporarily stopped study drug if AST or ALT > 2 x ULN observed [19]. Study drug was re-started if and when the liver test value decreased to < 1.5 x ULN. Log transformed maximum liver test, AST and ALT levels during follow up were used as the primary outcome; after transformation, the distributions of AST and ALT for LD-MTX and placebo subjects were close to a normal distribution (showed in Supplementary Figure 1), suitable as an outcome in linear regression. The ULN were defined based on the national reference laboratories, with the ULN for AST 35 units/L (men and women) and the ULN for ALT was 29 units/L for women and 46 units/L for men. Any instance of >2 x ULN for either AST or ALT during follow-up was studied as a secondary outcome (liver function test LFT >2 x ULN, “LFT2”). This definition of 2 x ULN was chosen to be consistent with the previous publication regarding adverse events from LD-MTX in CIRT [21]. Safety rules in the trial required LD-MTX to be stopped temporarily if liver tests were elevated higher than 2 x ULN. These guidelines have been the standard of care in monitoring RA patients treated with LD-MTX since the 2015 ACR guidelines were published [6]; the monitoring guidelines used in CIRT were very similar.

Genotyping and imputation

Subjects were genotyped using an Illumina Multi-Ethnic Global BeadChip (MEGA chip). Standard quality control (QC) was done for genotyped data using PLINK software (a toolset for GWAS and population-based linkage analysis) [22], followed by imputation using the 1000 Genomes phase3 reference panel from the Michigan imputation server [23]. Ancestry was determined by K-means clustering of individuals based on principal component analysis that included 1000 Genome phase3 subjects as reference in PLINK. European ancestry (EUR) was defined using the first three principal components referenced from 1000 Genome (Supplementary Figure 2) [24]. For QC of the imputed genotype data, we first excluded low imputation quality variants based on a priori imputation r2 < 0.5, and then we excluded variants with minor allele frequency (MAF) lower than 0.02 [25]. Further, we removed triallelic variants and insertion-deletions. 8769,640 variants were included in the GWAS analysis. HLA alleles, including classical HLA haplotypes, were imputed using SNP2HLA [26] utilized the Type 1 Diabetes Genetics Consortium (T1DGC) data as the reference panel.

Statistical analyses

Genome-wide association analysis.

Using log transformed maximum AST or ALT values during follow up as the primary outcome, we conducted a GWAS in subjects from the LD-MTX arm. The imputed dosage or genotyped data for each SNP was modeled additively by linear regression, using PLINK2 software. We included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), log transformed values of AST or ALT at baseline (based on the outcome), days between maximum liver test values and baseline, diabetic status at baseline, metabolic syndrome at baseline, statin use at baseline, and four genotype principal components as covariates. These covariates were included because each was associated with the liver test measurements in the previous studiese [21,27]. The ALT/ and AST levels were found to not differ among alcohol consumption groups, thus it was not considered as a covariate. We also conducted a GWAS for the dichotomized secondary outcome, defined as elevated liver tests as any instance of > 2 x ULN for either AST or ALT during follow-up. A logistic regression model was used. Each SNP was modeled additively as well, adjusting for age, sex, BMI, diabetic status at baseline, metabolic syndrome at baseline, statin use at baseline, and the first four genotype principal components as covariates. We used the standard 5 × 10−8 as the threshold for genome wide statistical significance, 1 × 10−6 as suggestive significance. Distinct loci were defined as no SNP in LD with the leading SNP as LD R2 > 0.2, 1000 Genome phase 3 EUR LD score was utilized as reference. Quantile-quantile (QQ) and Manhattan plots were generated. Regional association plots were generated using Locus Zoom [28].

DILI weighted genetic risk score analyses

All the genetic variants including classical HLA alleles and SNPs previously reported associated with DILI were identified from NHGRIEBI GWAS catalog (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/). SNPs reported from non-European populations or SNPs derived from studies with fewer than 100 individuals were excluded. For all DILI associated SNPs, genotyped or imputed SNP results were extracted from the imputed dataset using VCFtools [29]. We created a DILI SNP weighted genetic risk score (wGRS) weighted by the log odds ratio (OR) of reported SNP associations with DILI and calculated as: , where ORi is the effect size reported for SNPi and SNPi is the number of copies (0, 1, or 2) of the risk alleles or (0–2) dosage for imputed SNPs. Eleven classical HLA alleles were included in the HLA wGRS. The 10 DILI SNPs and 11 HLA alleles included in our wGRS and the ORs employed for weighting are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. Associations between the DILI wGRS and log maximum AST, ALT, as well as the dichotomous secondary outcome were tested using linear regression and logistic regression, respectively; we controlled for the same set of covariates as in the GWAS analyses. The wGRS analysis were conducted in SAS (Cary NC, version 9.4).

Candidate SNP analysis between SNPs and the outcomes

SNPs that affected circulating AST or ALT levels from a large GWAS [16] from the UK Biobank, SNPs involved in MTX pharmacogenetics [18], or individual DILI risk SNPs were examined for association with primary and secondary outcomes using the same model in the GWAS analysis (detail in GWAS section). Because these SNPs were candidate variants that have previous evidence of association, we set the significance levels using Bonferroni correction.

Interaction analysis between SNP and treatment

We conducted interaction analyses between significant SNPs and treatment arm among the genotyped subjects in the trial, including the subjects from the LD-MTX arm and subjects from the placebo arm. Using PLINK2, we tested gene (SNPs)*environment (treatment arm) interaction for the primary and secondary outcomes. The SNPs tested for interaction include: 1) our top findings from GWAS for the primary outcome or secondary outcome in LD-MTX arm, at 10−6 level; and 2) candidate SNPs that showed significant association with the outcome after Bonferroni correction. We tested for interactions for SNPs associated with either AST, ALT levels or LFT >2 x ULN outcomes, and corrected for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni correction. The models included a SNP, treatment arm, an interaction term of SNP*treatment, and covariates: age, sex, BMI, diabetic status at baseline, metabolic syndrome at baseline, statin use at baseline, and first four principal components of ancestry. We only tested interactions for SNPs with MAF > 0.05.

Results

A sample of 1808 subjects from the LD-MTX arm and 1799 from the placebo arm of CIRT were genotyped. For the GWAS analysis, we included 1429 subjects from LD-MTX arm with genetic data who were of genetic EUR descent. The mean follow-up time in this group was 26 months. We utilized subjects from both arms for SNP drug interaction analyses. Baseline characteristics of both treatment arms are shown in Table 1; the study population had a mean age of 65 years and approximately 80% of subjects were male. Approximately 60% reported no alcohol use, 10% reported current smoking, and BMI was approximately 32.5 kg/m2. Approximately two-thirds of patients had diabetes, two-thirds had metabolic syndrome, and statins were used by nearly 87%. In the subsample for genetic analysis, clinical characteristics did not differ according to randomized allocation to LD-MTX or placebo.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of subjects with European ancestry in CIRT.

| LD-MTX (n = 1429) |

Placebo (n = 1464) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (std) or n (%) unless noted | |||

| Female sex | 263(17.96) | 273(19.1) | 0.43 |

| Age, (age at enrollment date) | 64.95(9) | 64.94(9.13) | 1.00 |

| Diabetes | 955(65.23) | 961(67.25) | 0.25 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 986(67.35) | 967(67.67) | 0.85 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1279(87.36) | 1248(87.33) | 0.98 |

| Hypertension | 1318(90.03) | 1276(89.29) | 0.52 |

| Current cigarette use | 165(11.27) | 173(12.11) | 0.48 |

| Alcohol use | |||

| Rarely or never | 897(61.27) | 869(60.81) | 0.24 |

| ≤ 1 drink/week | 303(20.7) | 327(22.88) | |

| >1 drink/week | 264(18.03) | 233(16.31) | |

| GFR, ml/min/1.73m2 | 81.5(21.5) | 82.08(21.09) | 0.47 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 32.43(6.03) | 32.71(6.06) | 0.21 |

| Weekly study drug dosage (mean, SD)* | 15.25(4.27) | 15.03(4.45) | 0.18 |

| Statin use | 1265(86.41) | 1239(86.7) | 0.81 |

| Insulin use | 330(22.54) | 313(21.9) | 0.68 |

| Aspirin use | 1126(76.91) | 1149(80.41) | 0.02 |

| Oral corticosteroid use | 16(1.09) | 17(1.19) | 0.81 |

| Respiratory medication use** | 180(12.3) | 172(12.04) | 0.83 |

| Non-steroid inhalers | 138(9.43) | 128(8.96) | 0.66 |

| Corticosteroid inhalers | 39(2.66) | 24(1.68) | 0.07 |

| Combination inhaler | 89(6.08) | 88(6.16) | 0.93 |

| Oral medications | 36(2.46) | 31(2.17) | 0.60 |

| SF36 General Health | 58.84(20.83) | 57.65(21.08) | 0.18 |

| CES-D 10 | 5.73(5.12) | 6.13(5.19) | 0.11 |

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; SF36, short-form 36; CES-D 10, Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression Scale, 10-item version.

Mean weekly dosage refers to the post-randomization period.

Respiratory medications include 3 kinds of inhalers & oral iv COPD meds.

For the primary outcomes, the maximum of AST during follow-up had median serum values of 32 units/L (interquartile range (IQR) 25–41) and 28 units/L (IQR 23–35) for LD-MTX and placebo subjects, respectively. For maximum of ALT, the median values were 38 units/L (IQR 28–53) and 31 units/L (IQR 24–42), respectively. For the secondary outcome, there were 129 (9%) in the LD-MTX group and 43 (3%) in the placebo group that met the definition of LFT >2 x ULN (AST >2 x ULN or ALT >2 x ULN) at least once during follow-up Table 2.

Table 2.

Top associated SNPs for GWAS with log maximum AST, ALT and LFT >2X ULN in LD-MTX subjects (n = 1429).

| chr | base pair | ref | alt | rs | Mapped Gene/nearest Gene | MAF | info | genotyped | association in LD-MTX subject | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| beta | se | p value | |||||||||

| log maximum AST outcome | |||||||||||

| 1 | 169,586,946 | T | C | rs2244526 | SELP | 0.1 | 0.92 | Imputed | 0.12 | 0.02 | 3.5E-07 |

| 2 | 28,804,276 | T | C | rs13421347 | PLB1 | 0.04 | 0.98 | Genotype | 0.17 | 0.03 | 4.8E-07 |

| 2 | 156,500,331 | G | A | rs72889976 | 0.04 | 0.77 | Imputed | 0.16 | 0.03 | 5.5E-07 | |

| 2 | 210,593,241 | T | G | rs71420769 | MAP2 | 0.03 | 0.78 | Imputed | 0.37 | 0.07 | 5.6E-07 |

| 4 | 67,601,162 | G | A | rs11937537 | 0.23 | 0.95 | Genotype | 0.09 | 0.02 | 1.4E-07 | |

| 12 | 131,011,393 | T | C | rs6486549 | RIMBP2 | 0.39 | 0.96 | Imputed | 0.07 | 0.01 | 9.8E-08 |

| 15 | 71,810,708 | T | C | rs59374539 | THSD4 | 0.02 | 0.99 | Genotype | 1.35 | 0.26 | 2.2E-07 |

| 17 | 65,706,413 | T | A | rs80320525 | NOL11 | 0.05 | 0.52 | Imputed | 0.81 | 0.16 | 9.4E-07 |

| 20 | 2,580,184 | C | A | rs570089265 | TMC2 | 0.02 | 0.74 | Imputed | 0.31 | 0.06 | 2.6E-07 |

| log maximum ALT outcome | |||||||||||

| 5 | 31,893,186 | TA | T | rs34950471 | PDZD2 | 0.09 | 0.77 | Imputed | 0.14 | 0.03 | 2.2E-07 |

| 9 | 1,279,510 | G | C | rs35602716 | DMRT2 | 0.02 | 0.83 | Imputed | 2.13 | 0.43 | 8.1E-07 |

| 17 | 2,707,990 | C | T | rs76993247 | RAP1GAP2 | 0.02 | 0.51 | Imputed | 0.59 | 0.09 | 5.0E-10 |

| 17 | 19,759,902 | A | C | rs28661593 | ULK2 | 0.03 | 0.70 | Imputed | 1.69 | 0.30 | 3.6E-08 |

| 18 | 8,723,770 | C | T | rs589952 | MTCL1 | 0.02 | 0.89 | Imputed | 1.14 | 0.22 | 2.0E-07 |

| 18 | 9,888,688 | A | G | rs551429 | TXNDC2 | 0.03 | 0.94 | Imputed | 1.59 | 0.30 | 1.9E-07 |

| LFT > 2X ULN outcome | |||||||||||

| 9 | 83,760,434 | A | G | rs11139045 | TLE1 | 0.03 | 0.998 | Genotype | 1.43 | 0.27 | 9.4E-08 |

| 12 | 52,994,955 | G | A | rs61747192 | KRT72 | 0.13 | 0.996 | Imputed | 0.83 | 0.17 | 9.9E-07 |

| 13 | 23,577,442 | T | C | rs77522295 | BASP1P1 | 0.04 | 0.998 | Genotype | 1.24 | 0.25 | 5.0E-07 |

Chr: chromosome; ref: reference allele; alt: alternative allele; MAF: minor allele frequency; info: imputation info score (0–1). All SNP reached suggestive significance level of 10−6. Genome wide significance was marked bold.

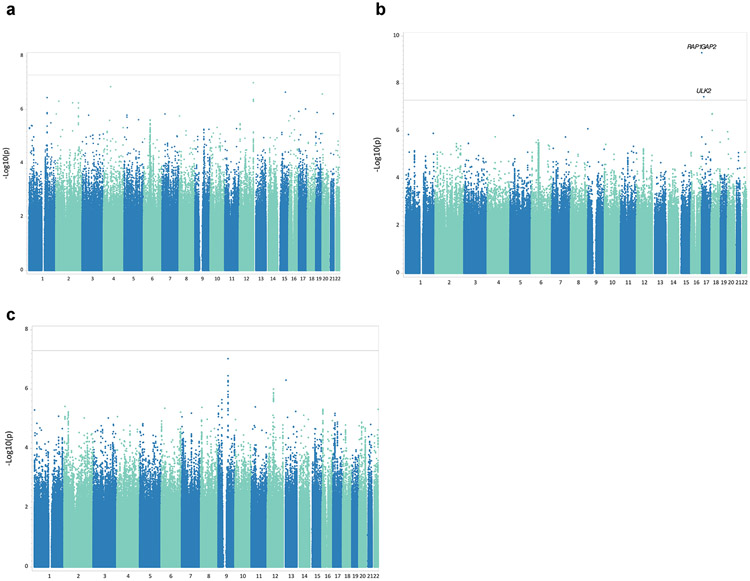

We performed GWAS among treated individuals and evaluated additive effect of 8.8 million genotyped/imputed autosomal SNPs (imputation info score > 0.5) on the primary outcomes (log transformed maximum AST or ALT level) and the secondary outcome (LFT > 2 x ULN). The quantile-quantile plots are shown in Supplementary Figure 3. Well-controlled genomic inflation was observed for all 3 GWASs with lambda-GCs are 1.0, 1.0 and 1.02, respectively. We identified two loci on chromosome 17 that reached genome wide significance (Fig. 1) for ALT association; rs76993247 (MAF=0.021) is an intron for the RAP1GAP2 gene and rs28661593 (MAF=0.031) is an intron for the ULK2 gene. No variants reached genome wide significance in the GWAS for maximal AST or either LFT > 2 ULN. We identified a total of 18 independent loci with suggestive evidence of association at 1 × 10−6 level for AST, ALT and either LFT >2 x ULN. Regional association plots for the two variants with genome wide significant are shown in Supplementary Figure 4.

Fig. 1.

Manhattan plot for primary log transformed maximum AST and ALT level, and secondary outcome of LFT>2X ULN, in LD-MTX subjects with European ancestry. 1a, GWAS MH plot for log transformed maximum AST; 1b, GWAS MH plot for log transformed maximum ALT; 1c, GWAS MH plot for LFT >2X ULN. *Solid line indicate genome wide significant cut off, 5 × 10−8

We calculated the DILI wGRS for each subject, the distribution of the wGRS is shown in Supplementary figure 5. We observed no associations of the DILI wGRS calculated from the 10 candidate SNPs, 11 classical HLA alleles, or all combined with the primary or secondary outcomes (Table 3). We further examined the association between each individual DILI risk alleles as candidate gene and the primary and secondary outcomes. Ten SNPs with minor allele frequency >0.02 and eleven HLA alleles that allele frequency >0.02 are reported in Table 3. One SNP, rs72631567 from RNU6, was observed to be associated with AST levels (beta (SE)=−0.08 (0.04); p = 0.04). Another SNP, rs2025009 from RAD51B, was observed to be associated with a 1.3-fold (95% CI: 1.01–1.71) (p = 0.04) higher risk, and HLA:C:0602 was associated with a lower risk of an elevated LFT > 2 x ULN, but all these association were not significant after multiple testing adjustments.

Table 3.

Association between DILI weighted genetic score and individual alleles with log maximum AST, ALT and LFT>2X ULN.

| chr | base pair | ref | alt | rs | mapped gene | MAF | info | genotyped | log max AST association | log max ALT association | LFT>2x ULN association | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| beta | se | p | beta | se | p | beta | se | p | |||||||||

| DILI SNPs | |||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 114,377,568 | A | G | rs2476601 | PTPN22 | 0.09 | 0.9996 | Genotype | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.30 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.82 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.23 |

| 2 | 5,195,358 | T | C | rs72631546 | 0.03 | 0.93 | Imputed | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.83 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.82 | 0.39 | 0.48 | 0.41 | |

| 2 | 5,232,178 | A | G | rs72631567 | RNU6 | 0.04 | 0.96 | Imputed | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.04* | −0.08 | 0.05 | 0.08 | −0.47 | 0.52 | 0.36 |

| 4 | 151,680,327 | G | A | rs28521457 | LRBA | 0.06 | 0.99 | Imputed | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.12 | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.27 | −0.90 | 0.48 | 0.06 |

| 6 | 29,828,660 | A | G | rs2523822 | TSBP | 0.27 | 1 | Genotype | 0.004 | 0.02 | 0.80 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.70 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.76 |

| 6 | 32,408,917 | T | C | rs3129880 | DRA | 0.19 | 0.9997 | Imputed | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.40 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.57 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.58 |

| 6 | 32,632,832 | A | T | rs9274407 | HLA-DQB1 | 0.16 | 0.93 | Imputed | 0.012 | 0.02 | 0.57 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.39 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.48 |

| 7 | 139,718,147 | C | G | rs2240395 | TBXAS1 | 0.37 | 1 | Genotype | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.26 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.76 | −0.09 | 0.14 | 0.54 |

| 11 | 85,436,868 | G | C | rs597480 | SYTL2 | 0.40 | 1 | Genotype | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.18 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.35 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.45 |

| 14 | 68,843,605 | G | C | rs2025009 | RAD51B | 0.39 | 0.9996 | Genotype | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.35 | 0.27 | 0.14 | 0.04* |

| Weighted DILI SNP GRS | |||||||||||||||||

| SNP wGRS | 0.0005 | 0.007 | 0.94 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.91 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.51 | ||||||||

| DILI HLA alleles | |||||||||||||||||

| 6 | HLA:A:0101 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.45 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.68 | ||||||

| 6 | HLA:B:0702 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.43 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.47 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.28 | ||||||

| 6 | HLA:B:5701 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.48 | 0.004 | 0.04 | 0.93 | −0.48 | 0.44 | 0.28 | ||||||

| 6 | HLA:C:0602 | 0.09 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.34 | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.15 | −0.68 | 0.28 | 0.017* | ||||||

| 6 | HLA:C:0702 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.19 | 0.07 | ||||||

| 6 | HLA:DQA1:0201 | 0.13 | 0.0002 | 0.02 | 0.99 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.41 | −0.36 | 0.23 | 0.12 | ||||||

| 6 | HLA:DQA1:0301 | 0.19 | −0.002 | 0.02 | 0.92 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.61 | −0.17 | 0.18 | 0.34 | ||||||

| 6 | HLA:DQB1:0303 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.59 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.74 | −0.26 | 0.38 | 0.48 | ||||||

| 6 | HLA:DQB1:0602 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.75 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.44 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.39 | ||||||

| 6 | HLA:DRB1:0701 | 0.13 | −0.001 | 0.02 | 0.97 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.38 | −0.36 | 0.23 | 0.12 | ||||||

| 6 | HLA:DRB1:1501 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.63 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.52 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.26 | ||||||

| Weighted DILI HLA GRS | |||||||||||||||||

| HLA-wGRS | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.54 | −0.03 | 0.07 | 0.69 | ||||||||

| Total weighted GRS | |||||||||||||||||

| total wGRS | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.37 | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.63 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.83 | ||||||||

p<0.05 Chr: chromosome; ref: reference allele; alt: alternitive allele; MAF: minor allele frequency; info: imputation info score (0-1). Bonferroni corrrect p-value cut off = 0.002. DILI: drug induced liver injury; GRS: genetic risk score; HLA: human leukocyte antigen.

There are 199 and 172 SNPs reported genome wide associations with AST and ALT levels respectively from a large UK Biobank GWAS [16]. Among these, 32 SNPs and SNPs at an additional 69 genes (same gene but different loci) were associated with both AST and ALT. No association among these SNPs met significance thresholds consistent with multiple testing for either of the primary AST or ALT outcomes, or the secondary outcome LFT>2 x ULN. All association signals did not pass multiple test adjustment, results are shown in Supplementaiy Table 2 and 3.

We also looked at association between 17 SNPs in established candidate genes involved in MTX pharmacogenetics and the primary and secondary outcomes in separate models. Associations for these 17 SNPs are reported in Table 4. The most significant SNP associated with abnormal liver tests (either LFT > 2 x ULN) was A3435G in ABCB1 gene (OR=1.36 for major allele, p = 0.02), encoding an MTX transporter. A SNP from the MTHFR gene, which is part of the folate pathway, and 2 SNPs from gamma glutamyl hydrolase (GGH) gene, which is involved in MTX glutamation, were also associated with either LFT > 2 x ULN. There was one SNP from the MTHFR gene as part of the folate pathway that showed an association with AST, and one SNP from SHMT gene, also part of folate pathway, that showed an association with ALT. None of these associations met significance standards for multiple testing. However, we observed 6 associations with p value <0.05; the probability of observing at least six is significantly higher than by chance (p = 0.01).

Table 4.

Association between candidate genes involved in MTX metabolism and log maximum AST, ALT and LFT > 2X ULN.

| chr | Base pair | ref | alt | rs | Gene | group | MAF | Info | genotyped | log ASTassociation | log ASTassociation | LFT>2X ULNassociation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| beta | se | p | beta | se | p | beta | se | p | ||||||||||

| 20 | 3,193,842 | C | A | rs1127354 | ITPA | adenosine | 0.08 | 1 | Genotype | −0.0014 | 0.03 | 0.96 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.65 | −0.33 | 0.27 | 0.22 |

| 1 | 115,236,057 | G | A | rs17602729 | AMPD1 | adenosine | 0.11 | 1 | Genotype | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.51 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.81 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.35 |

| 2 | 216,190,020 | C | G | rs2372536 | ATIC | adenosine | 0.32 | 1 | Genotype | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.11 | −0.12 | 0.14 | 0.38 |

| 5 | 79,915,020 | G | A | rs1232027 | DHFR | folate | 0.31 | 1 | Genotype | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.40 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.33 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.54 |

| 5 | 79,950,781 | A | G | rs1650697 | DHFR | folate | 0.24 | 1 | Genotype | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03* | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.11 | −0.27 | 0.16 | 0.10 |

| 1 | 11,854,476 | T | G | rs1801131 | MTHFR | folate | 0.30 | 0.997 | Genotype | −0.0045 | 0.01 | 0.76 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.70 | −0.10 | 0.14 | 0.50 |

| 1 | 11,856,378 | G | A | rs1801133 | MTHFR | folate | 0.31 | 0.998 | Genotype | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.47 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.14 | 0.02* |

| 17 | 18,232,096 | G | A | rs1979277 | SHMT | folate | 0.30 | 0.997 | Imputed | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.09 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.05* | −0.22 | 0.15 | 0.14 |

| 14 | 64,908,845 | G | A | rs2236225 | MTHFD1 | folate | 0.45 | 0.998 | Genotype | −0.0029 | 0.01 | 0.83 | −0.005 | 0.02 | 0.77 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.80 |

| 9 | 130,576,075 | T | C | rs10106 | FPGS | glutamation | 0.43 | 0.992 | Imputed | −0.0104 | 0.01 | 0.46 | −0.002 | 0.02 | 0.89 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.79 |

| 9 | 130,565,267 | A | G | rs10760502 | FPGS | glutamation | 0.34 | 0.904 | Imputed | 0.004 | 0.01 | 0.79 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.52 | −0.07 | 0.14 | 0.62 |

| 8 | 63,938,764 | G | A | rs11545078 | GGH | glutamation | 0.09 | 1 | Genotype | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.32 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.61 | −0.01 | 0.22 | 0.97 |

| 8 | 63,951,312 | A | G | rs1800909 | GGH | glutamation | 0.27 | 0.999 | Imputed | 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.93 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.51 | 0.31 | 0.14 | 0.03* |

| 8 | 63,951,728 | G | A | rs3758149 | GGH | glutamation | 0.27 | 0.998 | Imputed | 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.93 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.51 | 0.31 | 0.14 | 0.03* |

| 7 | 87,138,645 | A | G | rs1045642 | ABCB1 | transporter | 0.48 | 0.998 | Imputed | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.08 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.09 | −0.31 | 0.14 | 0.02* |

| 21 | 46,957,794 | T | C | rs1051266 | SLC19A1 | transporter | 0.45 | 0.91 | Imputed | −0.0197 | 0.01 | 0.16 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.26 | −0.17 | 0.14 | 0.23 |

| 10 | 101,563,815 | G | A | rs2273697 | ABCC2 | transporter | 0.20 | 1 | Genotype | 0.002 | 0.02 | 0.91 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.70 | −0.05 | 0.17 | 0.78 |

p<0.05 Chr: chromosome; ref: reference allele; alt: alternitive allele; MAF: minor allele frequency; info: imputation info score (0–1). Bonferroni corrrect p-value cut off = 0.003.

We assessed for an interaction between the five top SNPs from our GWAS and use of LD-MTX, at p value <1 × 10−6, and MAF higher than 0.05 (Table 5). There were 3 SNPs from the AST GWAS, 1 SNP from the ALT GWAS, and 1 SNP from either LFT > 2 x ULN GWAS that met the criteria for testing interaction. The four AST and ALT SNPs showed significant interaction after Bonferroni correction; uncorrected p values are 0.0004 (rs2244526 in SELP gene), 0.0006 (rs11937537 on chromosome 4), 0.01(rs6486549 inRIMBP2 gene) and 0.001 (rs34950471 in PDZD2 gene), respectively. But the SNP from LFT > 2 x ULN GWAS (rs61747192 in KRT72 gene) was not significant after Bonferroni correction. We did not test the interactions for individual DILI SNPs, AST, ALT associated SNPs, or MTX pharmacogenetics SNPs since none was associated with the outcomes in the discovery analysis.

Table 5.

Interaction between top associated SNPs from GWAS with LD-MTX treatment (n = 2893) and maximum AST, ALT and LFT > 2X ULN.

| chr | base pair | ref | alt | Rs | Mapped Gene | MAF | info | genotyped | association in LD-MTX subjects | association in placebo subjects | Interaction treatment*SNP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| beta | se | p value | beta | se | p value | beta | se | p value | |||||||||

| log maximum AST outcome | |||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 169,586,946 | T | C | rs2244526 | SELP | 0.1 | 0.92 | Imputed | 0.12 | 0.02 | 3.5E-07 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.66 | 0.13 | 0.036 | 0.0004 |

| 4 | 67,601,162 | G | A | rs11937537 | 0.23 | 0.95 | Genotype | 0.09 | 0.02 | 1.4E-07 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.54 | 0.088 | 0.025 | 0.0006 | |

| 12 | 131,011,393 | T | C | rs6486549 | RIMBP2 | 0.39 | 0.96 | Imputed | 0.07 | 0.01 | 9.8E-08 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.40 | 0.052 | 0.021 | 0.01 |

| log maximum ALT outcome | |||||||||||||||||

| 5 | 31,893,186 | TA | T | rs34950471 | PDZD2 | 0.09 | 0.77 | Imputed | 0.14 | 0.03 | 2.2E-07 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.23 | 0.15 | 0.045 | 0.001 |

| LFT >2X ULN outcome | |||||||||||||||||

| 12 | 52,994,955 | G | A | rs61747192 | KRT72 | 0.13 | 0.996 | Imputed | 0.83 | 0.17 | 9.9E-07 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.44 | 0.58 | 0.33 | 0.1 |

Chr: chromosome; ref: reference allele; alt: alternative allele; MAF: minor allele frequency; info: imputation info score (0–1). Bonferroni corrrect p-value cut off = 0.01.

Discussion

The current study is the largest GWAS study of AST and ALT levels in the subjects on LD-MTX to date. Liver test elevation is relatively common in patients who use LD-MTX in studies among rheumatic disease patients. In this study using the subjects on LD-MTX from an RCT among patients without rheumatic disease, we performed a GWAS to identify genetic variants that influence AST and ALT levels in patients on LD-MTX, as well as variants that affect either liver test > 2 x ULN.

The one study to determine actual correlations of elevations of transaminase enzymes and actual baseline and annual liver histopathology (including EM) established that repeat elevations anywhere in the abnormal range are indeed associated with hepatic histologic changes [30]. It was suggested that > 6 out of 12 monthly abnormal lab values was strongly associated with hepatic histological changes. This was used as guidelines for monitoring liver toxicity in treating RA using MTX [30]. Because liver biopsy is invasive, and one year follow up is not practical in clinic trial monitoring, the CIRT team utilized LFT > 2 x ULN as a proxy of any potential liver injury, followed American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) clinical guidelines [31]. This definition of LFT > 2 x ULN has been used in prior publications as well [32,33].

Two SNPs reached genome wide significance level with ALT levels: rs76993247 of RAP1GAP2 gene (repressor activator protein 1 (RAP1) GTPase activating protein 2) and rs28661593 of ULK2 gene (unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 2). The two SNP associations were not reported by a recently published GWAS analysis on 198 RA patients starting MTX [14], using log transformed maximum of ALT within the first 6 months as the primary outcome and ALT > 1.5 x ULN as the secondary outcome. One SNP rs72675408 in the RAVER2 gene was reported associated with the maximum of ALT level during 6 months of MTX use [14]. We did not see any signals (all p>0.1) for this SNP with any of our outcomes in the CIRT population. The study found approximately 9% of participants had liver test abnormalities > 1.5 x ULN [14]. This is quite similar to the percentage we observed in a non-RA cohort enrolled in CIRT. However, prior studies in RA have found a relationship between candidate genes and MTX related liver test abnormalities; we found none using a GWAS approach among a larger non-RA cohort.

We explored variant effect prediction for all the SNPs that reached a suggestive significance level of p<1 × 10−6 from all three GWAS’s (AST level, ALT level, AST or ALT > 2 x ULN), using the Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor webtool (VEP, https://useast.ensembl.org/info/docs/tools/vep/index.html). SNP rs61747192 of gene KRT72 (Keratin 72), predicted as a missense variant, was associated with AST or ALT > 2 x ULN. None of these SNPs were reported as a quantitative trait locus (QTL) (gtexportal.org pilot release).

Given our sample size of 1429 for the GWAS, the power to detect an association for AST or ALT levels was limited; we demonstrate the statistical power for different levels of effect size (Cohen’s D, standardized mean difference between groups) in terms of continuous log AST, ALT level in Supplementary Figure 6. We had adequate power to detect clinically relevant single variants of large effect (effect size >0.8, mean difference/pooled standard deviation). The power was limited for detection of low MAF SNP with more modest effect sizes. For example, the power was > 80% for MAFs of 10% to detect a moderate effect size of 0.3, large enough to be important in the clinical setting. By contrast, for a variant with a MAF of 2% we only have ~50% power to detect an association with a relatively large effect size of 0.7 (mean per allele difference/pooled standard deviation). The two SNPs found to have genome wide significance are relatively rare variants with MAFs of 2–3%; they have large effect sizes with beta-coefficients of 0.6 and 1.7 log unit/allele, corresponding to effect size about ~1.2 SD/allele and ~3.4 SD/allele, respectively, as the pooled standard deviation of the log maximum of ALT was about 0.5.

However, despite a sample size with adequate power to detect moderate genetic risk score effects, we did not find that either the DILI wGRS or the HLA wGRS was associated with any of the outcomes. The reason that we failed to see any association might be due to heterogeneity in the outcome definitions between DILI (from elevated liver tests to cirrhosis, https://dilin.org/) and our study. Previous GWAS results for HLA associations for DILI are generally drug specific. For example, HLA-B*57:01 is associated with DILI in response to flucloxacillin; HLA-A*02:01 and HLA-DRB1×15:01 are associated with amoxicillin-clavulanate (AC) [12]; HLA-B*35:02 is associated with minocycline [11]; and HLA-A*33:01 is associated with terbinafine and probably several other drugs as well [13].

Genes in cellular pathways of adsorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) of MTX are natural candidate genes for MTX toxicity. Meta-analysis found the ABCB1 C3435T [8], MTHFR C677T [9, 10] and A1298C [9] polymorphisms to be associate with MTX toxicity in RA patients. MTHFR is 5, 10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, an enzyme in the folic acid pathway influenced by the intracellular MTX, while ABCB1 is a member of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family. MTX is pumped out of cells through the ABC family of transporters [34]. We saw very little evidence of association with AST or ALT levels, even though the candidate variants in these genes are known to be strongly associated with other measures. We observed more suggestive associations for LFT > 2 x ULN including SNP C3435T from ABCB1 (rs1045642), SNP C677T in MTHFR (rs1801133), as well as SNP C-401T (rs1800909) in GGH gene, but the associations did not remain statistically significant after adjustments for multiple testing. However, we observed an enrichment of associations with small p values, suggesting at least some of the association might be true.

Chen et al. reported a meta-GWAS analysis for AST, ALT and alkaline phosphatase levels, combining samples from the United Kingdom Biobank and Japanese Biobank [16]. For the SNPs associated with AST and ALT reported in the publication, we did not see associations with AST or ALT levels in the subjects in CIRT randomized to LD-MTX. One possible reason is that genetic effects influencing the normal variation in liver function in the general population might be attenuated among the people recruited to use LD-MTX in this study sample. Subjects in this analysis all had cardiovascular disease plus many comorbidities; thus, they were likely in worse health compared to those from Biobanks. Moreover, our sample for genetic analysis was more than 100 times smaller.

We were interested in finding genetic variants that affect liver tests during LD-MTX use. We tested interaction between SNPs and treatment assignment in a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Testing for interactions may require a larger sample size, so we focused on candidate genes and SNPs with associations in the GWAS. We also restricted these analyses to SNPs with MAF > 0.05 for interaction analysis. We found four SNPs that had significant interactions with LD-MTX, out of a total of five SNPs tested. Further study is needed to follow up our findings reported here.

In summary, we did not observe common variants with strong effects that are clinical meaningful affecting liver function in EUR subjects using LD-MTX. In the current analyses, two SNPs with low to moderate MAF (~2%) reached genome wide significance level with ALT levels, rs76993247 of RAP1GAP2 gene and rs28661593 of ULK2 gene, but the genes are different than what has been reported in a large GWAS from the UK Biobank [16]; further study is needed to follow up this finding. Our findings may also vary from prior studies because the CIRT study population is different from a typical RA population; they were slightly older with a mean age of 65 years, more men (with 80% male), more diabetes (2/3 versus <10%), mostly not on NSAIDs, and 86% on statins. This difference might limit the generalizability of our findings to the RA population. We observed enrichment of associations between MTX pharmacogenetic candidate genes and AST or ALT in a non-rheumatic disease population. It is likely that the AST and ALT elevations consistent with DILI are complex polygenic traits, one or few single variants are not very informative to predict LD-MTX liver toxicity. With more associated loci identified in the future from studies with bigger sample size, we would be able to calculate a polygenic risk score to predict liver toxicity for population at risk, combined with associated factors such as age, comorbidity, history of abnormal liver tests.

Supplementary Material

Funding/Support

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH R01 HL119718, U01 HL101422, U01 HL101389, P30 AR070253).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None for Cui, Karlson and Xu.

Dr. Raychudhuri receives research grants from BMS/Celgene, Merck and Biogen. He also receives consulting fee from Rheos Medicines, Mestag Inc, Pfizer and Gilead.

Dr. Ridker receives research grants from Novartis, NovoNordisk, Pfizer, Amarin, He also receive consulting fees from Flame, Civi Bio-Pharm, Novartis, Glazo Smith-Kline, Health Outlook, Agepha, Horizon Therapeutics, SOCAR, Alynlam, R-Pharma, IQVIA, Baim Institute, Boehringer, MedScapre.

Dr. Solomon receives salary support for unrelated research from grants from the Amgen, Abbvie, CorEvitas, Janssen, Moderna, and the Rheumatology Research Foundation. He also receives royalties from UpToDate on unrelated work.

Dr. Chasman received research grant support from Pfizer and consulting fees from Takaeda, Inc

Clinical Trial Registration: NCT 01,594,333.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2022.152036.

References

- [1].Farber S, Diamond LK. Temporary remissions in acute leukemia in children produced by folic acid antagonist, 4-aminopteroyl-glutamic acid. N Engl J Med 1948;238(23):787–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Weinblatt ME, Coblyn JS, Fox DA, et al. Efficacy of low-dose methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 1985;312(13):818–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nikiphorou E, Negoescu A, Fitzpatrick JD, et al. Indispensable or intolerable? Methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis: a retrospective review of discontinuation rates from a large UK cohort. Clin Rheumatol 2014;33(5):609–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Visser K, van der Heijde DM. Risk and management of liver toxicity during methotrexate treatment in rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2009;27(6):1017–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lewis JH. Hy’s law,’ the ‘Rezulin Rule,’ and other predictors of severe drug-induced hepatotoxicity: putting risk-benefit into perspective. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2006;15(4):221–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr, et al. 2015. American college of rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & rheumatology (Hoboken, NJ. 2016;68(1):1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Leise MD, Poterucha JJ, Talwalkar JA. Drug-induced liver injury. Mayo Clin Proc 2014;89(1):95–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lee YH, Bae SC, Song GG. Association of the ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism with responsiveness to and toxicity of DMARDs in rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis. Z Rheumatol 2016;75(7):707–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Song GG, Bae SC, Lee YH. Association of the MTHFR C677T and A1298C polymorphisms with methotrexate toxicity in rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol 2014;33(12):1715–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Spyridopoulou KP, Dimou NL, Hamodrakas SJ, Bagos PG. Methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase gene polymorphisms and their association with methotrexate toxicity: a meta-analysis. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2012;22(2):117–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Urban TJ, Nicoletti P, Chalasani N, et al. Minocycline hepatotoxicity: clinical characterization and identification of HLA-B *35:02 as a risk factor. J Hepatol 2017;67(1):137–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lucena MI, Molokhia M, Shen Y, et al. Susceptibility to amoxicillin-clavulanate-induced liver injury is influenced by multiple HLA class I and II alleles. Gastroenterology 2011;141(1):338–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Nicoletti P, Aithal GP, Bjornsson ES, et al. Association of liver injury from specific drugs, or groups of drugs, with polymorphisms in HLA and other genes in a genome-wide association study. Gastroenterology 2017;152(5):1078–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sundbaum JK, Baecklund E, Eriksson N, et al. Genome-wide association study of liver enzyme elevation in rheumatoid arthritis patients starting methotrexate. Pharmacogenomics 2021;22(15):973–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cirulli ET, Nicoletti P, Abramson K, et al. A missense variant in PTPN22 is a risk factor for drug-induced liver injury. Gastroenterology 2019;156(6). 1707–1716 e1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chen VL, Du X, Chen Y, et al. Genome-wide association study of serum liver enzymes implicates diverse metabolic and liver pathology. Nat Commun 2021;12(1): 816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Friedman B, Cronstein B. Methotrexate mechanism in treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Joint, Bone, Spine 2019;86(3):301–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ranganathan P. An update on methotrexate pharmacogenetics in rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmacogenomics 2008;9(4):439–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ridker PM, Everett BM, Pradhan A, et al. Low-dose methotrexate for the prevention of atherosclerotic events. N Engl J Med 2019;380(8):752–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sparks JA, Barbhaiya M, Karlson EW, et al. Investigating methotrexate toxicity within a randomized double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial: rationale and design of the cardiovascular inflammation reduction trial-adverse events (CIRT-AE) Study. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2017;47(1):133–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Solomon DH, Glynn RJ, Karlson EW, et al. Adverse effects of low-dose methotrexate: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2020;172(6):369–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet 2007;81(3):559–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Das S, Forer L, Schonherr S, et al. Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nat Genet 2016;48(10):1284–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Evangelou E, Warren HR, Mosen-Ansorena D, et al. Genetic analysis of over 1 million people identifies 535 new loci associated with blood pressure traits. Nat Genet 2018;50(10):1412–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Charon C, Allodji R, Meyer V, Deleuze JF. Impact of pre- and post-variant filtration strategies on imputation. Sci Rep 2021;11(1):6214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Jia X, Han B, Onengut-Gumuscu S, et al. Imputing amino acid polymorphisms in human leukocyte antigens. PLoS ONE 2013;8(6):e64683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Zhang P, Wang CY, Li YX, Pan Y, Niu JQ, He SM. Determination of the upper cut-off values of serum alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase in Chinese. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21(8):2419–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Pruim RJ, Welch RP, Sanna S, et al. LocusZoom: regional visualization of genomewide association scan results. Bioinformatics 2010;26(18):2336–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Danecek P, Auton A, Abecasis G, et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 2011;27(15):2156–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kremer JM, Alarcon GS, Lightfoot RW Jr, et al. Methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis. Suggested guidelines for monitoring liver toxicity. American college of rheumatology. Arthritis Rheum 1994;37(3):316–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kwo PY, Cohen SM, Lim JK. ACG clinical guideline: evaluation of abnormal liver chemistries. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112(1):18–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Tona Lutete G, Mombo-Ngoma G, Assi SB, et al. Pyronaridine-artesunate real-world safety, tolerability, and effectiveness in malaria patients in 5 African countries: a single-arm, open-label, cohort event monitoring study. PLoS Med. 2021;18(6):e1003669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wong GL, Chan HL, Yuen BW, et al. The safety of stopping nucleos(t)ide analogue treatment in patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. Liver Int 2020;40(3):549–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Nagy ZB, Csanad M, Toth K, et al. Current concepts in the genetic diagnostics of rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2010;10(5):603–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.