Abstract

A robust literature documents the impact of poverty on child development and lifelong health, well-being and productivity. Racial and ethnic minority children continue to bear the burden of poverty disproportionately. Evidence-based parenting interventions in early childhood have the potential to attenuate risk attributable to poverty and stress. To reduce racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in the USA, parenting interventions must be accessible, engaging, and effective for low-income families of color living in large urban centers. This paper describes the initial development of ParentCorps and ongoing improvements to realize that vision. Initial development focused on creating a parenting intervention that places culture at the center and effectively embedding it in schools. ParentCorps includes core components found in nearly all effective parenting interventions with a culturally informed approach to engaging families and supporting behavior change. As the intervention is implemented at scale in increasingly diverse communities, improvement efforts include augmenting professional development to increase racial consciousness among all staff (evaluators, coaches, and school-based facilitators) and applying an implementation science framework to study and more fully support schools’ use of a package of engagement strategies.

Keywords: Prevention, Early childhood, Parent engagement, Poverty, Racial/ethnic minority, Cultural diversity

A robust literature documents the impact of poverty on child development and lifelong health, well-being, and productivity (see Blair and Raver 2016). Recent research documents associations between socioeconomic status and brain development (Brito and Noble 2014). Racial/ethnic minority children continue to bear the burden of poverty disproportionately, with Black and Latino children being especially likely to live in concentrated poverty. Children living in low-income urban neighborhoods are exposed to a host of stressors related to poverty and discrimination. Scholars argue compellingly for investing to mitigate stress early in children’s lives (Shonkoff et al. 2011).

Evidence-based parenting interventions early in life have the potential to attenuate risk attributable to poverty and stress. However, meta-analysis of 63 trials found that poverty is associated with lower participation in parenting interventions and smaller impact (Lundahl et al. 2006). A growing body of work documents the efficacy of interventions with low-income, racially, and ethnically diverse families of young children (e.g., studies of the Incredible Years [IY] Parent Series and Triple P; Reid et al. 2001; Zubrick et al. 2005). Yet little is known about the reach of these widely implemented interventions for this population or impact at scale. A population-level trial of Triple P in the southeastern US indicated that only 1% of parents participated in the group-based intervention (level 4; Prinz et al. 2009). Similarly, about 5% of parents participated in a parenting intervention in the Communities That Care trial (e.g., Strengthening Families; Fagan et al. 2009). A study of an evidence-based parenting intervention delivered at scale through family courts found that although more than half of parents expressed their intent to participate or interest in learning more, only about 10% actually attended one or more sessions (Wolchik et al. 2009). Reviews indicate that engagement tends to be modest in efficacy trials as well, with ~1/3 of invited families attending one or more sessions of preventive interventions (e.g., Baker et al. 2011; Garvey et al. 2006; Heinrichs et al. 2005). The literature on engagement in child mental health treatment is more extensive and indicates that ~2/3 of parents engage initially but the majority drop out prematurely (Gopalan et al. 2010; Haine-Schlagel and Walsh 2015; Ingoldsby 2010).

Innovative engagement strategies, grounded in theory (e.g., social influence principles, Transtheoretical Model, Health Behavior Model), are emerging as prevention scientists work to effectively transport university-tested interventions to the real world. Winslow and colleagues are testing very brief, low-cost strategies such as a self-assessment of need and potential benefits and DVD testimonials from peers and legitimate authority figures (Wolchik et al. 2009). To our knowledge, there are two experimental tests of strategies to enhance motivation to participate in preventive parenting interventions to date. Winslow et al. (2016) conducted a randomized test of a package of motivational strategies to engage parents of young children into group-based Triple P (level 4) delivered in an urban school serving primarily low-income, Mexican-American families. The school mailed all families (in kindergarten and 3rd grade) a brochure and a sign-up form; additionally, the engagement package for randomly selected families included a testimonial flyer with photos and quotes from parents, personalized teacher endorsement, engagement call, and weekly reminder calls from the group leader. The 20-min engagement call aimed to elicit goals, explain how goals would be addressed, and develop an action plan to overcome barriers to attendance. Overall, significantly more families attended at least one session in the experimental condition (48%) relative to controls (25%); effects were moderated by baseline risk, such that the package was effective with parents of at-risk children (i.e., high concentration or conduct problems). Interestingly, the engagement package was also uniquely effective for highly acculturated parents, who were less likely overall to attend and whose children were at higher risk for problems. Shepard et al. (2012) have developed and tested strategies to optimize engagement of low-income parents in the IY Parenting Series in Head Start centers. Specifically, to attend to variation in parents’ readiness for change, prior to the invitation to IY, parents received two home visits during which they participated in a modified version of the Family Check-Up, a brief intervention to increase parents’ motivation to take action (Dishion et al. 2008). Preliminary data from a randomized pilot showed that 53% of parents participated in IY after the Family Check-Up vs. 33% of controls (i.e., 1 home visit to build rapport and share information about IY). Head Start staff also utilized the standard IY engagement strategies, including offering the program at no-cost, providing child care, transportation, and family meals (Webster-Stratton 2011). Importantly, we do not assume that all parents should prioritize participating in preventive interventions, though in order to reduce racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities, interventions must be accessible, engaging, and effective for low-income families of color.

To highlight key challenges and promising solutions, this paper describes the initial development and vision for ParentCorps and ongoing efforts as the intervention is implemented at scale in increasingly diverse communities. Initial phases of development focused on creating a parenting intervention that places culture at the center and effectively embedding it in schools. We emphasize two aspects of improvement work to optimize parent engagement: (1) augmenting professional development to increase racial consciousness among all staff and (2) applying an implementation science framework to study and more fully support schools’ use of engagement strategies.

Summary of ParentCorps Evidence: Impact and Engagement

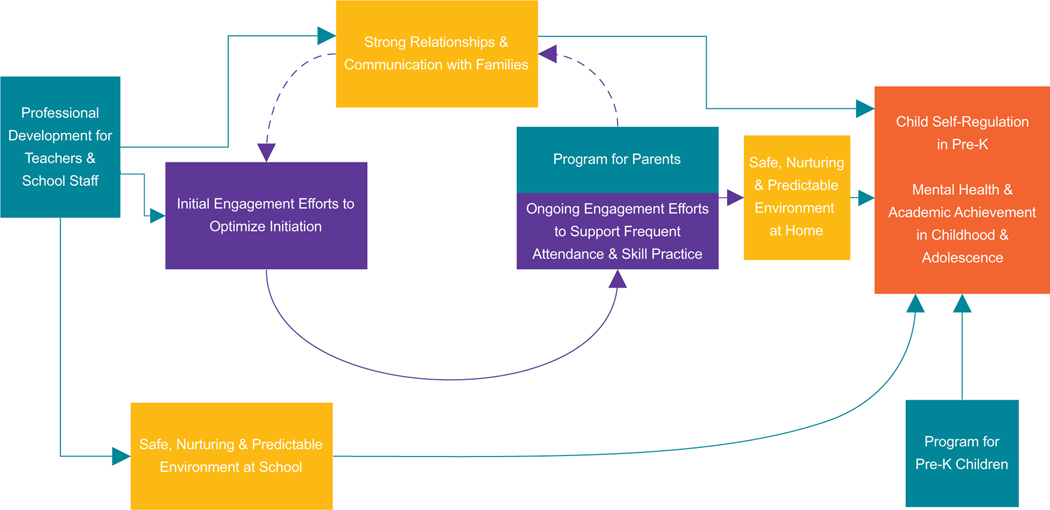

We briefly describe the theory of change and evidence of impact to date from two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in low-income, ethnic minority neighborhoods. ParentCorps includes a group-based parenting intervention, as well as components for teachers and children. Intervention aims to strengthen relationships and communication between parents and teachers and to promote safe, nurturing, and predictable environments (see Fig. 1). These changes scaffold children’s acquisition of self-regulation skills, and together, sustained changes in the environment and self-regulatory capacity contribute to mental health and achievement in childhood and adolescence.

Fig. 1.

ParentCorps theory of change. Note that intervention components are shown in blue, engagement efforts in purple, targeted mediators in yellow, and outcome in orange. Color figure online

Both RCTs were conducted in New York City (NYC) elementary schools with pre-k programs. The first trial demonstrated impact on the targeted mediators and child behavior problems in pre-k (8 schools; participants were 39% non-Latino Black, 24% Latino; 50% children of immigrants; Brotman et al. 2011). The second trial replicated impact on each of those outcomes in pre-k (10 schools; participants were 85% non-Latino Black, 10% Latino; 68% children of immigrants; Brotman et al. 2013; Dawson-McClure et al. 2015). Follow-up studies through the end of 2nd grade documented impact on children’s mental health and academic performance (Brotman et al. 2016) and, among high-risk children, on obesity (Brotman et al. 2012). To our knowledge, no other early intervention has shown impact on these three key domains of development.

We describe parent engagement in the context of the second RCT which enrolled 1050 pre-k children. This sample included nearly the full pre-k population (88% of eligible students). The only eligibility criterion was that at least one parent/caregiver spoke English (7% were ineligible); thus, while the sample is diverse in some respects (e.g., nationality, acculturation), findings cannot be generalized to non-English-speaking families. The 561 families who enrolled in the RCT in intervention schools served as the base for engagement into the parenting program. The majority (58%) of families initiated (i.e., attended once), ranging across schools (44–75%) and increasing over 4 years in the same schools (50–65%). Among families who initiated, average attendance was ~7 sessions (of 13). Dose-response analyses showed that the number of sessions attended was linearly related to changes in parenting; for heuristic purposes we set a threshold for “high dose” at five or more sessions (the “high dose” subgroup evidenced better parent and child outcomes vs. controls). Nearly 40% of children fell into this “high dose” subgroup and their families attended an average of 10 sessions. Importantly, neither initiation status nor attendance was predicted by family ethnicity, neighborhood poverty, baseline parenting, or child behavior (Dawson-McClure et al. 2015), indicating that a wide spectrum of families in high-poverty schools was engaged. We interpret these engagement rates as somewhat higher than those typically observed for preventive parenting interventions (~1/3 of families initiate; summarized above).

Below, we describe our approach to engagement and ongoing efforts to improve.

We built in elements to address known barriers and optimize engagement, conceiving broadly of initiating, attending frequently, and practicing skills at home. This sequence recognizes the multiple steps that underlie the targeted behavior change of parents consistently using evidence-based strategies at home. These aspects of engagement are empirically linked to intervention impact and are emphasized as salient mediators in Berkel et al.’s (2011) implementation framework (as “responsiveness”).

Initial Development of ParentCorps

From ParentCorps’ inception in 1998, the goal was to reduce racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities by creating a parenting intervention that would be accessible, engaging, and effective for low-income, culturally diverse families living in large urban centers. ParentCorps includes a core set of strategies (e.g., nurturing: positive attention during parent-child play, positive reinforcement; predictable: rules, commands, consequences) that are found in nearly all effective parenting interventions for young children, and a culturally informed approach to engaging families and supporting behavior change that is unique. We believe these features are key to achieve the following goals:

Embedded in schools or early education centers—and facilitated by school staff—to create a sustainable mechanism to reach the majority of children early in life.

Timed with the transition to school when parents may be especially open and motivated to change and when children are at risk for behavior problems.

Universal for all children as they enter pre-k to maximize acceptability, with the expectation that it would engage and benefit the highest risk families.

Includes multiple components—for parents, teachers, and children—in an effort to strengthen both home and classroom environments as buffers against poverty.

Group-based to create space for parents to come together, share ideas, and support each other in parenting effectively (“corps”).

Considering the Context for Parent Engagement

Embedding a parenting interventionin schools iskey for reach and accessibility. As with churches and community centers, schools are familiar places, often in close proximity to home, and do not invoke the stigma of treatment facilities or social service agencies. Yet, we are mindful of the challenges inherent in creating a safe, nurturing, and predictable environment for parents of color in schools. To this point, recent work in a Midwestern urban area found that Latino immigrant parents consistently identified church as a trusted and preferred setting, whereas schools were the opposite (Parra-Cardona et al. 2017). Fewer than 20% of teachers in the USA are racial/ethnic minorities, serving a student population that has recently become majority minority. As a result, most teachers are unfamiliar with the community norms of their students (Delpit 2006), misunderstand cultural norms (Tinkler 2002), and hold negative stereotypes (Suárez-Orozco et al. 2008). Recent experimental studies document implicit racial bias in teachers’ responses to young children (e.g., Gilliam et al. 2016). For example, teachers endorsed harsher punishments for the same misbehavior in hypothetical scenarios when the student was presumed to be Black vs. White (e.g., “Deshawn” vs. “Jake”); moreover, Black students’ misbehavior was significantly more likely than White students’ misbehavior to be perceived as indicative of a persistent pattern (Okonofua and Eberhardt 2015). For families of color, cultural gaps contribute to poor communication and lack of respect between parents and teachers (Cairney 2000). Parents who do not feel respected or valued are less likely to engage in school activities, which may serve to further reinforce negative stereotypes that parents are uncaring or incapable (Iruka et al. 2014) and undermine teachers’ commitment and effectiveness in engaging parents.

While the ParentCorps theory of change specifies strong relationships and communication with families as important mediators in their own right, we believe that helping teachers connect with families is essential to optimizing parent engagement in interventions delivered in school settings (Fig. 1, dotted arrows). For example, parents who feel welcome in the school building may be more likely to come to ParentCorps in the first place, and parents who have positive experiences with ParentCorps may be more likely to speak up and engage in children’s schooling in a variety of other ways (e.g., express concerns to teachers, share when circumstances at home may affect child’s performance at school, respond openly to suggestions from teachers). Accordingly, professional development aims to enhance commitment, confidence, and skill in building relationships with families from the start of the school year; fostering ongoing, frequent two-way communication; and effectively partnering if concerns about children arise. Professional development (PD) includes scenarios to elicit discussion about cultural misunderstanding and opportunities for teachers to practice these skills. As described below, our ongoing efforts to improve PD include a more explicit focus on building racial consciousness and addressing implicit bias.

Creating a Culturally Informed Parenting Intervention

The vision for ParentCorps was influenced by cultural adaptation efforts in the 1990s that sought to address the pervasive and persistent patterns of mental health service underutilization by minorities. Cultural adaptations aim to enhance engagement and effectiveness through a process of “systematic modification of an evidence-based intervention to consider culture and context in such a way that it is compatible with the client’s cultural patterns, meanings and values” (Bernal et al. 2009, p. 362). When true to form, cultural adaptation follows a series of planned steps that are guided by an in-depth familiarity with the literature, commitment to preserving core components of efficacious interventions, partnership with community members, extensive pilot work, and tests of efficacy (Castro et al. 2004; Parra Cardona et al. 2012).

Meta-analyses generally support the promise of cultural adaptations for meeting the needs of ethnic minority populations (e.g., Benish et al. 2011; Huey and Polo 2008; Smith et al. 2011). Specifically, cultural adaptations appear to be at least as efficacious as the original interventions on which they were based, and they may be more appealing to families. For example, Familias Unidas, which is specifically for Latino immigrant parents, considers how culture influences all aspects of adolescent development to support parents in learning how to best raise their Latino teens in a multicultural context (e.g., BConsistent with Hispanic cultural expectations, Familias Unidas places parents in positions of leadership and expertise and builds on pan-Hispanic values, such as primacy of family, sanctity of parental authority, and roles of parents as the family’s leaders and educatorŝ; Pantin et al. 2009). Engagement rates are encouraging; of 143 families who enrolled in the intervention, 80% attended at least 1 session and 34% were considered Bconsistent high attenderŝ (Coatsworth et al. 2006). The Strong African American Families program for parents of adolescents in the rural Southeastern USA has high engagement, with 65% attending 5 or more sessions (n = 332; Brody et al. 2004). Most of the evidence for cultural adaptations is based on interventions for parents of adolescents; a recent review of parenting interventions in early childhood settings noted the lack of rigorous evaluation of programs developed specifically for minority families (National Center for Parent, Family and Community Engagement 2015). The Chicago Parent Program is an important exception, which aimed to be culturally and contextually relevant for ethnic minority and low-income parents of young children in urban communities (e.g., “during the session on managing stress, Latino parents may talk about being immigrants and concerns about maintaining traditions in a non-Latino world while African American parents may talk about the stress of racism and how that affects their parenting behaviour”; Gross et al. 2009). Of 267 families in Head Start centers randomized to intervention (about 1/4 of those eligible), 76% attended at least 1 session and those parents attended an average of half the sessions (Breitenstein et al. 2012).

Still, some scholars question the need, feasibility, and methodological rigor of cultural adaptations (see Bernal and Domenech-Rodriguez 2012 for this debate). Specifically, critics argue that existing interventions are effective with minority groups; that adaptations can be timely and costly; and that adapting programs for specific groups could lead to never-ending iterations. Moreover, the process of adapting an intervention can be idiosyncratic, as most efforts are not guided by cultural adaptation frameworks, and thus have the potential to compromisethe fidelity of a rigorously developed, manualized, and tested intervention (Baumann et al. 2015).

Within this landscape, Brotman, Calzada, and Dawson-McClure developed ParentCorps as a preventive intervention for culturally diverse (e.g., with respect to race, ethnicity, immigrant status, nationality, religion) families living in urban areas with limited socioeconomic resources. In the spirit of cultural adaptation, we (1) systematically reviewed the literature on parenting interventions to identify core components—the set of behavioral parenting strategies and efficacious adult behavior change strategies (e.g., role play, home practice); (2) partnered with community stakeholders and cultural informants, including Black and Latino US-born and immigrant parents, educators, and mental health professionals; and (3) conducted several pilot studies of the intervention to ensure fidelity and fit for the population (e.g., Caldwell et al. 2005). We considered the diversity within and between urban communities. As with many urban areas, NYC is highly segregated, and its school district has been labeled the most segregated in the country, with 10% or fewer White students in 19 of 32 community districts (Civil Rights Project 2014). Yet, there is tremendous variation throughout non-White parts of the city, ranging from racial/ethnic enclaves to multicultural communities. We also considered the ways in which the characteristics of urban populations shift over time due to changing patterns of marriage, fertility, and immigration (e.g., from 2000 to 2010, 6% of NYC’s approximate 29,000 census blocks shifted from predominately White to predominately Latino or Asian). Other neighborhoods saw a decline in the presence of some minority groups; traditional enclaves for Black populations lost up to 18% of Black residents, replaced by representation from Latino and non-Latino White populations. Looking ahead to implementation at scale, we saw the need for a program that was designed with the complexities of urban communities in mind (Baumann et al. 2015).

We also noted that within these ever-changing communities, individual experiences of culture are expected to change as well. Consistent with a view of culture as “a dynamic system that is constantly in the process of reconstruction and renegotiation in the context of individual lives” (Super and Harkness 2002), we were mindful of ever-shifting values and behaviors reflective of parents’ acculturation (i.e., participation in US mainstream culture) and enculturation (i.e., maintenance of one’s culture of origin). Theories of acculturation recognize it as a complex micro- and macro-level process of sustained contact between two distinct groups that follows a dynamic course, leading to shifts across time and situation (Calzada et al. 2015). As parents acculturate, behavioral and cognitive adjustments occur that influence the values they want to instill in their children, expectationsfor children’s behavior, and choices about how to parent (Calzada et al. 2012). In families with two parents or extended kin networks, the acculturation/enculturation of each adult follows a unique, individualized path, further adding complexity to the cultural characteristics of the family.

To serve changing, multicultural communities and families, we set out to develop a program that places culture at the center, while also being easily translatable within a larger, pluralistic society. ParentCorps is not for a particular cultural group but instead embraces a broad definition of culture, one in which the values and beliefs that are incorporated into the program are identified by each parent based on his or her own cultural identity (e.g., Puerto Rican with strong familistic values; African-American with strong racial identity; latergeneration, English-speaking Dominican; Jamaican who immigrated as an adult). We place culture at the center of each parenting program session by honoring every family’s culture as important and adaptive (Garcia Coll et al. 1996) through discussions and activities to elicit salient cultural and contextual issues as they relate to parenting. In the initial sessions, parents reflect on what influences their parenting and their child’s development, and share about their cultural values and beliefs. Parents then set goals for their children, grounded in a “whole child” view of development (i.e., social, emotional, behavioral, physical, and academic) that creates space to consider a range of values and hopes for their children. For example, a mother who places a high value on respect and obedience may also express wanting to help her son feel confident and try hard in school even when he’s frustrated. These culturally informed goals are a focal point in subsequent sessions as parents assess fit and relevance of each parenting strategy. The process is collaborative, allowing for the mutual transfer of expertise in which parents reflect on their cultural values and beliefs in reaction to the strategies introduced by facilitators. Driven by the unique characteristics of their child, family, and context, and informed by “the science of parenting” (i.e., strategies linked to positive child outcomes, cross culturally robust), parents make their own decisions about whether and how to use the strategies. Facilitators expect and accept this and actively support parents’ autonomy to do so. Each strategy is introduced through a consistent session structure, including evocative questions (e.g., What might your grandmother say about praising children for good behavior? Did your parents or other important adults play with you when you were a child? What would they think if they saw you down on the floor playing now?). Facilitators invite parents to express skepticism and also encourage parents to consider whether each new strategy may be helpful in meeting any of their goals or in certain situations, potentially creating openness to a strategy initially perceived as at odds with a prominent value. Returning to the example above, the mother who values respect may also tend not to engage in nurturing strategies, but decides to try praise or parent-child play in order to reach her goal of boosting her son’s confidence and persistence.

By including evidence-based parenting strategies from the extant literature, we were mindful that some are viewed as aligning with White, middle-class values, and as incongruous with traditional values of other cultures (see Parra-Cardona et al. 2017). Indeed, in a qualitative study of Latina mothers’ perceptions of evidence-based strategies (Calzada, Basil, & Fernandez, 2013), many mothers objected to the use of material rewards. Interestingly, there was total consensus on the use of praise, and thus not a sense that positive reinforcement in general was incompatible with the value of respeto. This is consistent with our approach—to empower parents to choose which strategies they find acceptable within both broad domains (nurturing and predictable).

We expect that placing culture at the center in these ways enhances engagement both in terms of supporting attendance at subsequent sessions and skill practice at home, by increasing the extent to which parents experience the sessions as relevant and respectful, and perceive the strategies as helpful in reaching salient goals.

Engagement Strategies to Optimize Initiation

As with many evidence-based parenting programs, ParentCorps aims to minimize logistical barriers experienced by many families in low-income communities by providing meals, childcare, and a venue in close proximity to home. We encourage schools to schedule the program flexibly based on parents’ availability and preferences, including offering both daytime and evening options. When parents have limited resources, time, and lack of control over schedules, participating in a multi-session program may be a competing demand that simply cannot be met. We view meals and childcare as a necessary acknowledgement of this reality and a way of helping parents “get in the door.” We also consider sharing meals to provide an important time for relationship-building among parents and with facilitators. We work with schools to order meals from local businesses that include familiar, culturally relevant foods and honor preferences and traditional diets (e.g., Halal).

Engagement messaging expresses value for parents, frames the goal of the intervention as “helping children succeed” and explicitly links children’s experiences at home with school success (bolstering parents’ perceived benefits and influence; Ajzen 1991). Every pre-k family is invited—while it is not assumed that all families can or should prioritize a preventive intervention—and parents are always welcome to join regardless of the parameters (e.g., arriving late from work, unable to attend every session). The invitation extends to all adults who are important in the child’s life (e.g., grandparents, aunts). Core engagement strategies include ParentCorps brochures and sign-up sheets sent home, posters hung visibly in the school, endorsement of the program by school leaders, and individual communication by phone or in person in the course of daily interaction at school. This brief personal communication, typically done by teachers or parent support staff, ensures that parents are aware of the program and invites them to come “check it out.” This framing respects parents’ autonomy to choose and is supported by research showing that once people agree to a small request, they are more likely to agree to a larger request (e.g., attending weekly sessions; McDonald et al. 2012). Optional strategies include hosting events, during which teachers or parent ambassadors (past participants in ParentCorps) share their experiences with new parents. Thus, the strategies, messaging, and reduction of logistical barriers are considered the initial engagement package.

Engagement Strategies to Support Frequent Attendance and Skill Practice

In addition to the culturally informed approach to behavior change described above, we built activities into the sessions to support frequent attendance and scaffold skill practice (including reinforcement ofattending, arriving ontime, and practicing skills via “tickets” that are entered into drawings for gift cards). The first session includes activities to solidify commitment (reading quotes from parent ambassadors and sharing your reason to attend) and to help parents anticipate barriers and identify solutions (modeled on an effective strategy to increase engagement in children’s mental health treatment; Nock and Kazdin 2005). In each session, the facilitator highlights the goals for which the strategy is especially relevant. Increasing the salience of goals heightens the likelihood that parents will take action (Abraham and Sheeran 2003). Each session ends with planning for home practice and begins with problem-solving any barriers encountered. Parents receive a photograph-based(i.e.,not text dense)guide “for Parents from Parents,” which includes take-aways for each strategy and BBring it Homê pages with step-by-step instructions to try it at home and simple charts to monitor how it went. Parents also receive “tools” to put strategies into practice (e.g., routine chart, praise magnet).

The value of these kinds of organizational tools and scaffolding of parents’ executive functioning skills (EF; goal-setting, planning, problem-solving) is magnified through a two-generation lens. A recent report from the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University (2016) applies advances in scientific understanding of the impact of stress to disrupt EF early in life and in adulthood to highlight the challenges that parents living in poverty face, and accordingly, specific ways that programs for families can be more successful. The authors note, “The best examples not only ensure that the services improve their uptake, use, and retention but also introduce common tools that augment core capabilities at the same time that they scaffold practicing the underlying skills.” Although ParentCorps does not aim to promote adult capabilities, it does scaffold parents in practicing EF skills and management of stress and emotions in the context of trying new parenting strategies, which may increase their capacity to consistently and flexibly use these new strategies as well as generalize to other aspects of their lives.

Efforts to Improve Engagement at Scale

Based on evidence of short- and longer-term benefits for children, we have taken steps to support implementation at scale. We emphasize two aspects of this improvement work to optimize parent engagement.

Augmenting Professional Development Through a Racial Equity Lens

Informed by implementation efforts outside of RCTs in 24 schools and early education centers, we have been innovating to accelerate and optimize behavior change through PD. As described above, one of the aims of PD is to help schools create safe, nurturing, predictable environments in which parents are inclined to engage. Our current 2-day sequence for school leaders and 4-day sequence for teachers, assistants, school-based mental health professionals, and parent support staff provides opportunities to consider the unique barriers faced by families in segregated, high-poverty schools and reflect on assumptions about parents that may interfere with their efforts to connect with parents (e.g., parents are uncaring or incapable). Discussions aim to create a space in which participants share honestly their frustration with parents; facilitators give participants permission to feel and create safety by normalizing negative emotions (a distinct departure from typical directives to “Keep trying. Be nicer.”) Experiential activities are designed to create shifts in how participants think, feel, and act. For example, mousetraps is an interactive game that becomes increasingly challenging as new rules and restrictions are added. Facilitators debrief the game to help participants make connections to the challenges that parents face when they enter a school building, including parents’ own experiences in school and past and current experiences of racism. Participants often have insights (e.g., “I am just realizing… I was a mousetrap for that parent.”) that strengthen their commitment to act on their values instead of their biases.

We draw on counter-narratives from parents of color that showcase the values and commitment of marginalized parents to their children’s education (e.g., “Don’t assume that low income means low intelligence or low caring. I raise my children to the best of my ability…I am a hard-working, Black female. I don’t sell drugs or walk the streets. Please don’t put me in a box. I am well educated.” McKenna and Millen 2013). We are partnering with principals and teachers to find ways to explicitly honor parents’ commitment and listen to parent voices; for example, we are working to make space for parents to share and teachers to listen during orientation and other school events. Given the systemic challenges described above, and the intensity surrounding race and racism in the USA, we are exploring additional augmentation of PD through deeper work on racial consciousness and equity (e.g., Watson and Bogotch 2015). We join others in advocating for all staff (e.g., evaluators, coaches, and school staff) to reflect on and address implicit biases that shape assumptions of parent (un)involvement, expectations of child (under)performance (e.g., Iruka et al. 2014), and harsh reactions to child misbehavior. Furthermore, this kind of transformational work could create a context in which parents trust school staff to serve as advocates to access resources and services, such as job training or English classes, to improve their own well-being and that of their children.

Studying and Supporting Engagement Efforts

As we move toward scaling ParentCorps, we utilize implementation science frameworks (e.g., Metz et al. 2015) and draw on the science of improvement, an emerging approach to improve health care and education (e.g., Bryk et al. 2015). This process involves iterative cycles to turn promising ideas into workable processes and tools, with the goal of building practice-based evidence or the “know how” to effectively engage families and yield positive child outcomes consistently across diverse school settings. In our current efforts to support and study implementation of ParentCorps in 24 schools in NYC—with school staff fully responsible for engaging parents in the parenting program—we observe much greater variability than in the RCTs. We are taking the following steps to improve our understanding of engagement in increasingly diverse communities and our coaching of engagement efforts by school staff:

Assess engagement at the population level, via multiple indicators, including initiation, attendance, and skill practice at home. Focusing on interventions implemented at scale in early childhood settings, Wasik et al. (2013) note that the “collection and use of dosage data for program improvement is in its infancy.”

Name engagement strategies as part of the package to be implemented with an evidence-based intervention and assess fidelity to the package. As detailed above, we have defined the package to optimize initiation (including specific messaging and personal communication) and are coaching schools to make a plan for when and how they will carry it out, adapting or incorporating optional strategies as desired for fit. We are tracking execution of these plans that can be linked to engagement data, as well as gathering qualitative data from school staff and parents about the feasibility and appeal of the strategies.

Assess characteristics of the target population, including child risk factors at baseline (e.g., low self-regulation skills), family poverty, and culture. Isolate race, ethnicity, immigrant status, and other salient aspects of culture in the community being served to determine whether some groups are not being reached. This information is critical for school/district leaders and for evaluating whether a wide spectrum of families is being served as in the RCTs (Dawson-McClure et al. 2015). Similarly, assess characteristics of the implementing organization and staff responsible for engagement to understand influences on (a) fidelity to the engagement package and (b) engagement rates.

Innovate and test a range of engagement strategies, capitalizing on new technologies as relevant to implementing sites and populations. For example, we are testing the feasibility of supplementing engagement with text messages infused with behavioral economic principles to help overcome the “intention-behavior gap” (Baker et al. 2011; Winslow et al. 2016).

Build organizational capacity to support implementation in languages other than English. We have completed translation of manuals and materials into Spanish and Chinese (simplified characters) and have piloted the parenting intervention in both languages in several sites. We are examining the feasibility of helping school leaders make a plan to deliver the intervention multiple times throughout the year in the languages (and at times) needed to serve the majority of families.

We aim to put these five recommendations into practice in our work and are utilizing the Stage-Based Framework for Implementation of Early Childhood Programs and Systems (Metz et al. 2015) to do this systematically. The framework focuses on three core elements: (1) building and using teams to actively lead implementation, (2) developing an implementation infrastructure, and (3) using data and feedback loops to drive decision-making and promote continuous improvement to be considered from exploration to full implementation. The authors cite evidence that “implementing a well-constructed, well-defined, well-researched program to the point of successful functioning and sustainability can be expected to take two to four years” (page 4). The Supplemental Table 1 applies this framework to parent engagement and identifies key tasks to support and study engagement at each stage of implementation.

Conclusions

Evidence-based parenting interventions in early childhood hold great promise for reducing racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in learning, behavior, and health. This promise can only be realized if interventions successfully engage families, especially those in greatest need. Embedding evidence-based interventions in schools makes population-level reach possible, yet it requires a major investment of resources (monetary, personnel, and otherwise), and low parent engagement may undermine the public’s will to sustain such an investment. Careful study of engagement through racial equity and two-generation lenses, and thoughtful use of data for continuous improvement, are essential to ensure success. Reductions in disparities will only occur if researchers, practitioners, and policymakers work together to advance innovations to improve access to evidence-based parenting interventions and effectively engage low-income, culturally diverse families of color. As we make progress in partnering with child-serving institutions to implement interventions that create safe, nurturing, and predictable environments for children and families, intervention impacts and the success of their engagement efforts are likely to be mutually reinforcing, gradually supplanting the disengaging and disempowering experiences that low-income parents and parents of color so often have in public institutions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful for the families, teachers, assistants, social workers, school leaders, and other staff who have partnered with us in this work. We honor the wisdom and skill of ParentCorps Academy co-directors, Dana Rhule and Katherine Rosenblatt, and the team of trainers and coaches. We thank Tony Hudson of Pacific Educational Group for sharing his insights and guiding us toward racial equity transformation.

Funding

This work was funded by the Institute of Education Sciences (R305F050245, R305A100596), National Institute of Mental Health (1R01MH077331-01), and the New York State Office of Mental Health (C007885).

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11121-017-0763-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Abraham C, & Sheeran P. (2003). Implications of goal theories for the theories of reasoned action and planned behaviour. Current Psychology, 22(3), 264–280. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker CN, Arnold DH, & Meagher S. (2011). Enrollment and attendance in a parent training prevention program for conduct problems. Prevention Science, 12, 126–139. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0187-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann AA, Powell BJ, Kohl PL, Tabak RG, Penalba V, Proctor EK, et al. (2015). Cultural adaptation and implementation of evidence-based parent training: A systematic review and critique of guiding evidence. Children and Youth Services Review, 53, 113–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benish SG, Quintana S, & Wampold BE (2011). Culturally adapted psychotherapy and the legitimacy of myth: a direct-comparison meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(3), 279–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Mauricio AM, Schoenfelder E, & Sandler IN (2011). Putting the pieces together: An integrated model of program implementation. Prevention Science, 12, 23–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal GE, & Domenech Rodríguez MM (2012). Cultural adaptations: Tools for evidence-base practice with diverse populations. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Jiménez-Chafey MI, & Domenech Rodríguez MM (2009). Cultural adaptation of treatments: a resource for considering culture in evidence-based practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(4), 361–368. [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, & Cybele Raver C. (2016). Poverty, stress, and brain development: new directions for prevention and intervention. Academic Pediatrics, 16(3), S30–S36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitenstein SM, Gross D,Fogg L, Ridge A, Garvey C, Julion W, & Tucker S. (2012). The Chicago Parent Program: Comparing 1-year outcomes for African American and Latino parents of young children. Research in Nursing & Health, 35, 475–489. doi: 10.1002/nur.21489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito NH, & Noble KG (2014). Socioeconomic status and structural brain development. Front Neuroscience, 8, 276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Molgaard V, McNair L, …Neubaum-Carlan, E. (2004). The Strong African American Families Program: Translating research into prevention programming. Child Development, 75, 900–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman L, Calzada EJ, Huang K, Kingston S, Dawson-McClure S, Kamboukos D, …Petkova, E. (2011). Promoting effective parenting practices and preventing child behavior problems in school among ethnically diverse families from underserved, urban communities. Child Development, 82, 258–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman L, Dawson-McClure S, Calzada E, Huang K, Kamboukos D, Palamar J, & Petkova E. (2013). Cluster (school) RCT of ParentCorps: Impact on kindergarten academic achievement. Pediatrics, 131, e1521–e1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman L, Dawson-McClure S, Huang K, Theise R, Kamboukos D, Wang J, …Ogedegbe G. (2012). Early childhood family intervention and long-term obesity prevention among high-risk minority youth. Pediatrics, 129, e621–e628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman LM, Dawson-McClure S, Kamboukos D, Huang KY, Calzada EJ, Goldfeld K, & Petkova E. (2016). Effects of ParentCorps in prekindergarten on child mental health and academic performance: Follow-up of a randomized clinical trial through 8 years of age. JAMA Pediatrics, 170, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Gomez LM, Grunow A. & LeMahieu PG (2015). Learning to improve: How America’s schools can get better at getting better. Cambridge: Harvard Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cairney TH (2000). Beyond the classroom walls: The rediscovery of the family and community as partners in education. Educational Review, 52, 163–174. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell M, Brotman LM, Coard SI, Wallace S, Stellabotte D, & Calzada E. (2005). Community involvement in adapting and testing a prevention program for preschoolers living in urban communities: ParentCorps. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 14, 373–386. [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Ramirez D, Covas M, Huang KY, & Brotman LM (2015). A longitudinal study of cultural adaptation among Dominican and Mexican immigrant mothers. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 35, 469–485. doi: 10.1177/0739986313499005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Basil S, & Fernandez Y. (2013). What Latina mothers think of evidence-based parenting practices: a qualitative study of treatment acceptability. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 20(3), 362–374. [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Huang K-Y, Anicama C, Fernandez Y, & Brotman LM (2012). Test of a cultural framework of parenting with Latino families of young children. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18(3), 285–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera M, & Martinez CR (2004). The cultural adaptation of prevention interventions: resolving tensions between fidelity and fit. Prevention Science, 5, 41–45. doi: 10.1023/B:PREV.0000013980.12412.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University (2016). Building core capabilities for life: The science behind the skills adults need to succeed in parenting and in the workplace. http://www.developingchild.harvard.edu. Accessed 5 June 2016.

- Civil Rights Project (2014) New York State’s Extreme School Segregation. https://www.civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/ny-norflet-reportplaceholder. Accessed December 2015.

- Coatsworth JD, Duncan LG, Pantin H, & Szapocznik J. (2006). Patterns of retention in a preventive intervention with ethnic minority families. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 27, 171–193. doi: 10.1007/s10935-005-0028-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson-McClure S, Calzada E, Huang KY, Kamboukos D, Rhule D, Kolawole B, …Brotman LM (2015). A population-level approach to promoting healthy child development and school success in low-income, urban neighborhoods: Impact on parenting and child conduct problems. Prevention Science, 16, 279–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpit LD (2006). Other people’s children: Cultural conflict in the classroom. New York: The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Shaw D, Connell A, Gardner F, Weaver C, & Wilson M. (2008). The Family Check-Up with high risk indigent families: preventing problem behavior by increasing parents’ positive behavior support in early childhood. Child Development, 79, 1395–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan AA, Koren H, David Hawkins J, & Arthur MW (2009). Translational research in action: implementation of the communities that care prevention system in 12 communities. Journal of Community Psychology, 37(7), 809–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, Pipes McAdoo H, Crnic K, Wasik BH, & Vazquez Garcia H. (1996). Child Development, 67, 1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvey C, Julion W, Fogg L, Kratovil A, & Gross D. (2006). Measuring participation in a prevention trial with parents of young children. Research in Nursing & Health, 29, 212–222. doi: 10.1002/nur.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam WS, Maupin AN, Reyes CR, Accavitti M, & Shin F. (2016). Do early educators’ implicit biases regarding sex and race relate to behavior expectations and recommendations of preschool expulsions and suspensions?. New Haven: Yale Child Study Center. [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan G, Goldstein L, Klingenstein K, Sicher C, Blake C, & McKay MM (2010). Engaging families into child mental health treatment: updates and special considerations. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 19, 182–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross D, Garvey C, Julion W, Fogg L, Tucker S, & Mokros H. (2009). Efficacy of the Chicago Parent Program with low-income African American and Latino parents of young children. Prevention Science, 10, 54–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haine-Schlagel R, & Walsh N. (2015). A review of parent participation engagement in child and family mental health treatment. Clinical Child Family Psychology Review, 18, 133–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs N, Bertram H, Kuschel A, & Hahlweg K. (2005). Parent recruitmentand retention ina universal prevention program for child behavior and emotional problems: Barriers to research and program participation. Prevention Science, 6, 275–286. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-0006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huey SJ, & Polo AJ (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for ethnic minority youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37(1), 262–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingoldsby EM (2010). Review of interventions to improve family engagement and retention in parent and child mental health programs. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19, 629–645. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9350-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iruka IU, Curenton SM, & Eke WA (2014). The CRAF-E 4 Family Engagement Model: Building practitioners’ competence to work with diverse families. [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl B, Risser HJ, & Lovejoy MC (2006). A meta-analysis of parent training: moderators and follow-up effects. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 86–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald L, FitzRoy S, Fuchs I, Fooken I, & Klasen H. (2012). Strategies for high retention rates of low-income families in FAST (Families and Schools Together): an evidence-based parenting programme in the USA, UK, Holland and Germany. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9(1), 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna MK, & Millen J. (2013). Look! Listen! Learn! Parent narratives and grounded theory models of parent voice, presence, and engagement in K-12 education. School Community Journal, 23, 9–48. [Google Scholar]

- Metz A, Naoom SF, Halle T, & Bartley L. (2015). An integrated stage-based framework for implementation of early childhood programs and systems (OPRE 201548). Washington, DC: US DHHS. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Parent, & Family and Community Engagement. (2015). Compendium of parenting interventions. Washington, DC: Office of Head Start, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, & Kazdin AE (2005). Randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for increasing participation in parent management training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 872–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okonofua JA & Eberhardt JL (2015). Two strikes: Race and the disciplining of young students. Psychological Science, 1–8. doi: 10.1177/0956797615570365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantin H, Prado G, Lopez B, Huang S, Tapia MI, Schwartz S, et al. (2009). A randomized controlled trial of Familias Unidas for Hispanic adolescents with behavior problems. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71, 987–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra-Cardona JR, López-Zerón G, Villa M, Zamudio E, EscobarChew AR, & Domenech Rodríguez MM (2017). Enhancing parenting practices with Latino/a immigrants: integrating evidencebased knowledge and culture according to the voices of Latino/a parents. Clinical Social Work Journal, 45(1), 88–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra Cardona JR, Domenech-Rodriguez M, Forgatch M, Sullivan C, Bybee D, Holtrop K, …Bernal G. (2012). Culturally adapting an evidence-based parenting intervention for Latino immigrants: The need to integrate fidelity and cultural relevance. Family Process, 51, 56–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz RJ, Sanders MR, Shapiro CJ, Whitaker DJ, & Lutzker JR (2009). Population-based prevention of child maltreatment: the u.s. triple p system population trial. Prevention Science, 10(1), 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid MJ, Webster-Stratton C, & Beauchaine TP (2001). Parent training in Head Start: a comparison of program response among African American, Asian American, Caucasian, and Hispanic mothers. Prevention Science, 2, 209–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard S, Armstrong LM, Silver RB, Berger R, & Seifer R. (2012). Embedding the Family Check Up and evidence-based parenting programs in Head Start to increase parent engagement and reduce conduct problems in young children. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 5, 194–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, Siegel BS, Dobbins MI, Earls MF, Garner AS, McGuinn L, Pascoe J, & Wood DL (2011). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232–e246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TB, Rodríguez MD, & Bernal G. (2011). Culture. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(2), 166–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco C, Suárez-Orozco MM, & Todorova I. (2008). Learning a new land: Immigrant students in American society. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Super CM, & Harkness S. (2002). Culture structures the environment for development. Human Development, 45, 270–274. [Google Scholar]

- Tinkler B. (2002). A review of literature on Hispanic/Latino parent involvement in K-12 education. Colorado: Assets for Colorado Youth Expect Success Project. [Google Scholar]

- Wasik BA, Mattera SK, Lloyd CM, & Boller K. (2013). Intervention dosage in early childhood care and education (OPRE 2013–15). Washington, DC: US DHHS. [Google Scholar]

- Watson TN, & Bogotch I. (2015). Reframing parent involvement: What should urban school leaders do differently? Leadership and Policy in Schools, 14, 257–278. [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C. (2011). The incredible years parents, teachers, and children training series: Program content, methods, research and dissemination, 1980–2011. Seattle: Incredible Years, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Winslow EB, Poloskov E,Begay R, Tein J. Sandler, I., & Wolchik, S. (2016). A randomizedtrial of methodstoengage Mexican American parents into a school-based parenting intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(12), 1094–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolchik SA, Sandler IN, Jones S, Gonzales N, Doyle K, Winslow E, Zhou Q, & Braver SL (2009). The New Beginnings Program for divorcing and separating families: Moving from efficacy to effectiveness. Family Court Review, 47, 416–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubrick SR, Ward KA, Silburn SR, Lawrence D, Williams AA, Blair E, & Sanders MR (2005). Prevention of child behavior problems through universal implementation of a group behavioral family intervention. Prevention Science, 6, 287–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.