Introduction

According to the National Survey of Children’s Health, approximately one in seven young children (i.e., two- to eight-years old) in the U.S. experiences mental health problems (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016). Rates of formal diagnoses are lower, at least in part, because many mental health problems go undiagnosed (Biederman et al., 2002; Tremmery et al., 2007). According to recent estimates, three to seven percent of children have a formal diagnosis of depression, anxiety, and/or conduct disorder (Ghandour et al., 2018); the majority of these children will experience problems into adulthood (Kim-Cohen et al., 2003). Though findings on the mental health status of young Latinx children are mixed (Alegría et al., 2011; Hamilton et al., 2011), Latinos as a whole are disproportionately exposed to risk factors known to undermine mental health, leading to significant racial/ethnic disparities in adolescence and adulthood (Alegría et al., 2008). A robust literature examines these disparities through the lens of structural inequities, which are largely rooted in race (Viruell-Fuentes et al., 2012). Still, past studies of mental health with Latinos (an ethnic categorization), and children in particular, have seldom considered the influence of race despite the racial diversity of the Latinx population. More generally, scholarship on race and ethnicity often unfold in isolation of the other, despite the critical ways in which they work in concert to impact populations of color (Valdez & Golash-Boza, 2017). The overarching goal of the present study is to advance scholarship on the intersection of race, ethnicity, and gender in the study of mental health by examining associations between skin color and internalizing and externalizing problems in a racially diverse sample of young Latinx children.

Race and Ethnicity among Latinos

Race and ethnicity are social constructs rooted in long-standing, complex historical and political contexts (Garcia, 2017; Valdez & Golash-Boza, 2017). Race may best be understood as a multidimensional dynamic and relational construct of phenotypes and the meanings (e.g., racial identity) and implications of phenotypic characteristics for an individual in relation to others (Garcia, 2017). Put simply, race is “a proxy for shared biology and environment” (Kittles et al., 2007, pg. 10). Ethnicity refers to social grouping based on shared country of origin, language, values, and customs, independent of phenotype. Unlike race, ethnicity is self-defined (Valdez & Golash-Boza, 2017).

Latinos are often viewed in terms of race (i.e., ascribed race), even as they themselves disavow racial categorization (Darity et al., 2005). A study of Dominican immigrants found that while only 5% self-identified as racially black, 35% reported that others perceived them as black (Itzigsohn et al., 2005). Similarly, in a study by Darity and Boza (2004), only 2% of Latinos self-identified as black, compared to 17% based on researcher ratings of observed skin shade. Although contemporary theories of racial classification consider an antiquated black-white binary categorization, emphasizing that Latinx populations may fall anywhere within a racial hierarchy (Bonilla-Silva et al., 2003; Kittles et al., 2007). Such gradations in skin color can be captured empirically through skin color ratings that range from white to black. In an early study by Arce and colleagues (1987), skin color among Chicanos (i.e., Mexican Americans) was rated as spanning categories of “light” (26%), “intermediate” (45%), and “dark” (28%). Among Latinx youth in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, half were coded based on rater observations as having brown skin; among brown-skinned youth, 35% were rated as light brown, and 15% were rated as medium or dark brown (Kizer, 2017). Such statistics support the study of skin color on a continuum and underscore the heterogeneity, both across and within racial categories, of Latinx populations.

Skin Color and Mental Health

The extant literature documents clear, albeit often unconscious and implicit, societal preference for light-skinned over dark-skinned people (Duster, 2008; Newheiser & Olson, 2012), and these biases shape the everyday experiences of people of color. Studies of colorism, or the preference for and privilege of light skin over dark skin (Burke, 2008), show that darker-skinned Latinos earn less income, have a lower socioeconomic status, are more likely to live in low-income neighborhoods, perceive more discrimination, and experience higher levels of health problems, such as diabetes and depression (Araujo & Borrell, 2006; Borrell & Crawford, 2006; Hersch, 2008; Montalvo & Codina, 2001). A recent meta-analysis found racism to be a robust predictor of Latinx health (physical and mental), even more so than of African American health (Paradies et al., 2015). This pattern of findings suggests that in the case of Latinos, race trumps ethnicity (Cuevas et al., 2016; Rodriguez, 2000). Still, scholarship on phenotype as a correlate of Latinx mental health remains limited (Golash-Boza & Darity, 2008). In their meta-analysis, Paradies and colleagues (2015) found that less than 19% of participants in published studies of racism as a determinant of health were Latinx.

Skin Color and Mental Health in Latinx Children

Mental health problems, broadly conceptualized as internalizing (anxiety, depression) or externalizing (aggression, hyperactivity, conduct problems), are common in youth, especially in the Latinx population (Ramirez et al., 2017). Among Latinx adolescents, disproportionately high rates of anxiety (Pina & Silverman, 2004; Varela et al., 2008), depression, suicidality (Guzman et al., 2009), and aggression (Kann et al., 2018) have been documented. Scholars agree that pathways to mental health problems in adolescence start in early childhood (Egger & Angold, 2006). Approximately 15% of children under the age of six are thought to have clinically-significant problems, including hyperactivity, depression, and anxiety (CDC, 2016; von Klitzing et al., 2015). Though scant attention has been paid to Latinx mental health in early childhood, recent studies show the presence of significant externalizing and internalizing problems, even at those young ages (Calzada et al., 2015; Calzada et al., 2012).

As with adults, current theory implicates race as a key determinant of child mental health. According to the integrative model of child development (Garcia Coll et al., 1996)—arguably the most widely-applied developmental model for diverse populations—race and ethnicity serve as social position factors that “interact in ways to magnify or diminish the importance of [other developmental] factors” to ultimately “influence or create alternative developmental pathways” (p. 1895). In other words, this model applies the concept of intersectionality to the study of developmental trajectories of health and well-being by suggesting that social position factors collectively determine the context within which child development occurs. Disparities in wealth and health among adults are believed to stem from racialized experiences that begin in the first years of life (Cheng & Goodman, 2015; Priest et al., 2013). Still, virtually no empirical research has examined skin color in relation to the behavioral and mental health of children or adolescents (Breland-Noble, 2013).

Recent studies that examined the link between skin color and criminality found that Latinx youth with darker skin were more likely than those with lighter skin to associate with violent peers, perpetrate violence, be stopped and arrested by police, and come into contact with the criminal justice system (Acalá & Montoya, 2018; Ryabov, 2017; White, 2015). In addition, a study on adolescent depression found that Latinx youth who were phenotypically black reported higher levels of depression than Latinx youth who were phenotypically white (Ramos et al., 2003). Two studies have looked at the association between skin color and self-esteem. One found a negative relation between dark skin color and both body image and self-esteem in a sample of Ecuadorian youth (de Casanova, 2004). Another study found no association between skin color ratings and self-esteem with Puerto Rican school-aged children (Erkut et al., 2000). Yet, skin ratings in the latter study were based on self-report and were skewed, with more than 70% of children selecting one of the two lightest tones presented to them and only 5% rating themselves as dark. Even among children, self-ratings seem to be influenced by colorism. Collectively, these studies suggest that skin color is used as the basis of stratification that disadvantages darkerskinned Latinx populations across the lifespan. Still, to our knowledge, no studies have examined skin color and mental health in early childhood.

Conceptual Framework

Our conceptual framework is guided by two complementary theories: the integrative developmental model and intersectionality (Seaton et al., 2018). Intersectionality theory emerged from Black feminist scholarship to emphasize the interconnected nature of social categories and argues that social position is best understood by considering the intersection of these categories of difference: race, ethnicity, immigrant status, gender, and age (Bauer, 2014; Crenshaw, 1989; Viruell-Fuentes et al., 2012). Ethnic designation alone (e.g., Latinx) is considered overly simplistic, since experiences are determined by the totality of the social groups to which a person belongs or is assigned. Specifically, individual experiences are situated at the crux of various systems of oppression that work in concert to create inequities. The integrative model (García Coll et al., 1996) applies this concept to child development by arguing that a child’s race, ethnicity, and gender determine social position, and that positionality shapes everyday interactions, with implications for mental health. In other words, mental health is believed to reflect the unique social positions of boys versus girls, and of children with light versus dark skin. The present study examines these two key indicators of positionality (i.e., gender and skin color) in relation to child mental health.

For young children, everyday interactions occur primarily at home and at school. In the classroom, teachers react to students based on a number of individual characteristics, including child (mis)behavior (Coplan et al., 2015), gender (Woods et al., 2016), and race/ethnicity (Neal et al., 2003; Okonofua & Eberhardt, 2015). Teachers appear to hold more negative perceptions of Latinx and African American students compared with non-Latinx white students (Tenenbaum & Ruck, 2007), starting in preschool (Gilliam et al., 2016). Dark-skinned boys, in particular, are perceived as aggressive, threatening, and criminal, even at very young ages (Todd et al., 2016), in part because they are seen as older, more responsible for their actions, and less innocent than white boys (Goff et al., 2014).

Among Latinos, “skin color preference…has been a poorly kept secret in families” (Montalvo, 2001), such that very little is known about how skin color influences how parents interact with their children. Some studies suggest that mothers show preferential treatment towards lighter-skinned children, while others suggest that parents give darker-skinned children more attention and support in preparation for experiences of discrimination outside of the home (Adames et al., 2016. In a recent study with African American youth (Landor et al., 2013), ) higher quality parenting (i.e., less harshness, more warmth) was shown towards dark-skinned boys relative to light-skinned boys, whereas the reverse was found for girls. Another study with Mexican-American children found that mothers engaged in more cultural socialization efforts with light-skinned daughters relative to dark-skinned daughters; no association was found for boys (Derlan et al., 2017). In a study with Mexican-American adolescents, cultural socialization by mothers had stronger effects on the ethnic identity of dark-skinned relative to light-skinned youth (Gonzales-Backen & Umaña-Taylor, 2011). In other words, an emerging literature supports the notion that skin color impacts parent-child interactions and child development in ways that may be gender-specific.

To the extent that skin tone shapes parent-child and teacher-student interactions, it is likely to influence children’s mental health functioning. A robust literature documents the link between parenting practices and Latinx child mental health (Halgunseth et al., 2006). Similarly, the use of effective teaching practices, or those that create a structured, positive, and nurturing learning environment, promote children’s behavioral functioning (Barth et al., 2004; Pianta et al., 2002). But students of color are significantly less likely to be praised, more likely to be punished, and more likely to receive suspensions and expulsions (Noltemeyer & Mcloughlin, 2010; Skiba et al., 1997). More generally, teacher-student interactions tend to be more conflictual for darkskinned boys than for other students (MacLin & Herrera, 2006; Maddox & Gray, 2002).

Although daily interactions serve as the most proximal predictors of Latinx child mental health, teacher-student and parent-child interactions play out within the context of broader societal notions of race and color. Structural racism is a pervasive and self-perpetuating system that creates and reifies racial and ethnic inequities (Hicken et al., 2019), and arguably influences populations of color more so than individual-level factors (Gee & Ford, 2011). Since colonization, U.S. social ideologies, policies, and processes have favored whites categorically, with relative advantages also extended to people of color with European features and light skin tones (phenotyping/colorism; Dixon & Telles, 2017; Reece, 2019). Recent work suggests these patterns persist, both in the U.S. and in Latin America (Dixon & Telles, 2017; Monk, 2015), where the mothers in the present study were born.

Zambrana (2011) argues that colorism is a key stratification variable for understanding the racialization—and thus the unequal distribution of power—in the heterogenous Latinx population in the U.S. In other words, the structures that uphold inequities may be understood through an intersectional lens that implicates racialized institutional practices in some Latinx communities/subgroups more than in others. Over historical time in racialized societies, “minority groups used phenotyping standards in family socialization as a survival tool where children were socialized to acknowledge skin color preference as a reality in their lives” (Montalvo, 2001, p. 278). Such examples of internalized racism illustrate how adults—including parents and teachers of Latinx children themselves—must navigate racism and colorism, with direct implications for their own social status, health and well-being (Viruell-Fuentes et al., 2012) and in turn, their relationships with their children and students (Balagna, Young, & Smith, 2013).

The Present Study

Racial phenotype shapes the ways in which others perceive and interact with an individual, with implications for both immediate and long-term well-being. Still, to our knowledge, the empirical link between gradations in skin color (i.e., one of the most salient phenotypic characteristics) and mental health in early childhood has yet to be established. The present study takes an initial step to address this gap by considering whether skin color is indeed associated with mental health functioning in young children. Although we do not test the underlying mechanisms in the present study, our work is guided by the integrative developmental model and intersectionality theory, which highlight structural racism at the macro-level and everyday interactions (e.g., with parents and teachers) at the micro-level as mechanisms that explain the link between race and mental health.

We use a racially diverse sample of Mexican- and Dominican-origin children in prekindergarten and kindergarten. The Mexican-origin population (the largest Latinx group in the U.S.) is generally of white, indigenous, or mixed white and indigenous race, whereas Latinos who are ethnically Dominican are generally white, black or mixed white and black race. Our first aim was to describe child mental health functioning across four behavioral domains (internalizing: anxiety, depression; externalizing: hyperactivity, depression), as rated by both teachers and mothers. As per the integrative model and intersectionality theory, we hypothesized that boys and children with darker skin tones would receive higher ratings of behavior problems, especially in the externalizing domain of functioning and on teacher ratings.

Our second aim was to test a model of child mental health, with skin tone as a moderator in the association between internalizing and externalizing behaviors at baseline and at follow-up. Given that children with mental health problems are at risk for later mental health problems, we expected a significant positive association between mental health functioning at baseline and follow-up for all children. However, we expected that the association between baseline and follow-up behavior problems would be strongest for children with dark skin tones (e.g., skin tone as a moderator) because past studies show more negative teacher-student interactions among children of color, which serve to maintain or exacerbate problems. We tested our model separately for boys and girls because, consistent with intersectionality, boys of color appear to be most susceptible to negative societal perceptions and behavior problems.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from a larger, longitudinal study of the early development of Latinx children conducted in New York City (NYC) with 750 mother-child dyads; the present study included all children with skin color ratings (N=684; 91% of the larger study sample). The sample was recruited from pre-kindergarten and kindergarten classrooms and consisted of Dominican-origin (DA) children and Mexican-origin (MA) children (M age=4.43 years) and their mothers. The majority of children were U.S.-born (92%), whereas the majority of mothers were foreign-born (93%). About half of mothers were high school graduates (55%). Most families (75%) were two-parent households and 70% of families were living below the federal poverty level.

Procedure

Children and their mothers were recruited between 2010 and 2013 from 24 public elementary schools that served DA and MA students in NYC. Partner schools served a student population that was majority Latinx (73%) and who were eligible for free or reduced lunch (94%). Research assistants (RA), fluent in Spanish and English, recruited participants at parent meetings and daily school drop-off and pick-up times. Recruitment took place during the initial three-month period of the school year. All children were entering pre-kindergarten or kindergarten at the time of enrollment into the study (Time 1).

Interested mothers were consented and scheduled for an appointment with a bilingual RA at their child’s school. Most mother assessments (98% of MA and 76% of DA) were conducted in Spanish. Additionally, teachers were asked to complete questionnaires on each participating student in their class. Most teachers (92%) consented to participate, and most (93%) consenting teachers returned their packets. There were no significant differences on sociodemographic characteristics and parent-rated child functioning between children who did and did not have teacher ratings in the study.

We were able to follow-up and reassess 69% of participants (472 of 684) at the end of first grade (Time 2). Bivariate analyses showed that there were no differences on socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., child’s gender and age, mother’s age, marital status education level, and immigrant status, and family income-to-needs ratio) and child socio-emotional functioning between participants who did and did not remain in the study at Time 2. However, children who were not assessed at Time 2 had a darker skin tone rating than those who remained in the study (t = −2.67, p < .01).

Measures

Skin color.

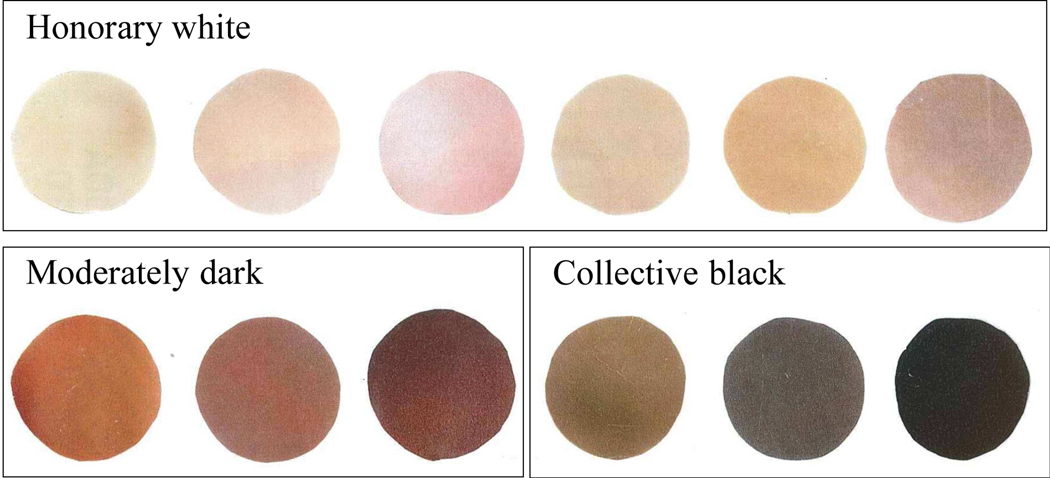

The skin color rating scale used in the present study was developed by our research team (Kim & Calzada, 2018) and included a series of twelve shades used in the cosmetic industry to serve consumers of diverse racial heritages (Massey & Martin, 2003). Using high-quality color copies of skin tone shades, RAs rated children’s skin color during Time 1 assessments. All raters were Latinx, as recommended by scholars of phenotype (Montalvo & Codina, 2001), and diverse in country of origin (e.g., Mexican, Dominican, Puerto Rican, Salvadoran) and immigrant status (e.g., first- or later-generation). Agreement between observers was acceptable (Cohen’s κ = .61).

To create skin color categories, we first examined the distribution of ratings. Our data did not support a “white,” “honorary white” and “collective black” classification system because only about 3% of children were rated at the first three skin tones (categorized as “white”). Thus, we merged “white” skin color with the next three light skin tones to create an “honorary white” category. For the remaining six skin tones, we distinguished between “moderately dark” and “collective black”—each with three skin tones—to avoid recreating a dichotomous, black/white variable. The skin colors are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Skin color shades used in rating scale

Behavior problems.

The Behavior Assessment System for Children-2 (BASC-2; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004) measures multiple dimensions of social-emotional and behavioral functioning with well-established psychometric properties. The BASC-2 has the Parent Rating Scales (PRS) and the Teacher Rating Scales (TRS) available in both English and Spanish. Mothers and teachers rated 139 items about the child’s behaviors within home and school environments during the past four weeks on a 4-point scale (0 = never; 3 = almost always). In the present study, four subscales (anxiety, depression, hyperactivity, and aggression) were used to measure mother-reported and teacher-rated behavior problems at Times 1 and 2. Calculated were T-scores based on child age for each subscale (M = 50, SD = 10), and children who scored > 60 (T-score) were categorized as “at risk.” Internal consistency with the present study sample was adequate (α =.82 to .84 in Spanish and α = .80 to .86 in English).

Sociodemographic characteristics.

Mothers completed a sociodemographic form at Time 1 that included information on immigrant status (child and mother), education level, household composition, and family income (brought in by any person within the home who shared household expenses with the mother). The family income-to-needs ratio was calculated as total family income divided by the poverty thresholds based on household size.

Analytic Plan

To address our research questions, we used two time points: baseline data at the time of enrollment into the study for independent (skin color, behavior problems at baseline) and control (gender, ethnicity, grade) variables and follow-up data collected at the end of first grade for dependent variables (internalizing, externalizing problems). We used data from 684 families that had skin color ratings at baseline. There was some missing data at baseline on mother-rated behavior problems (nine cases), teacher-rated behavior problems (50 to 68 cases), and family income-to-needs ratio (41 cases). At T2, 31% of families were lost to attrition (remaining n = 472). As a result, 225 cases were missing for mother-rated behavior problems, and 317 to 333 cases were missing for teacher-rated behavior problems. Analyses revealed significant differences in child age, grade, ethnicity, and family income-to-needs ratio between missing and non-missing data of each outcome variable. Therefore, we included these four factors as covariates in regression models (Rubin, Stern & Vehovar, 1995). We consider our data to be missing at random (MAR) and thus used multiple imputation methods (van der Heijden, Donders, Stijnen, & Moons, 2006) to account for missing data on all measures with the exception of the skin color measure. The SAS multiple imputation procedure was used with 10 replicated imputations, and SAS PROC MIANALYZE was used to combine the results for all analyses. While multiple imputation gives valid results when data are missing at random and has a number of advantages over complete case analyses (van Ginkel, Linting, Rippe, & van der Voort, 2019), there is still a concern of bias in literature given that our data may not have been missing completely at random (Sterne, White, Carlin, et al., 2009). To address this possibility, we ran the models using listwise deletions and found the same results as those presented in the final models.

For our first aim, we ran descriptive statistics of mental health functioning, by child gender and skin tone. For our second aim (i.e., model testing), we first examined the correlations between behavior problems at baseline and follow-up. Then, we conducted multiple linear regression analyses for each outcome. We regressed child’s and family’s characteristics on each dependent variable; and then included interaction terms based on the “moderately dark” and “collectively black” ratings with each behavior problem subscale at baseline (VanderWeele & Knol, 2014). We computed interaction terms by subtracting the mean from each score in order to reduce multicollinearity between the direct effects and interaction terms (Aiken et al., 1991). When interaction terms were significant, the sample was divided by skin color, and regression coefficients for behavior problem subscale at baseline were assessed in each group. Finally, we conducted multilevel modeling at the school level as a sensitivity analysis although clustering within schools was not extensive (ICC=0.5 to 3.5%, varying by outcome variables; insignificant between-level variances for all outcome variances). According to Lee (2000), multilevel modeling is encouraged in education research when ICC is greater than 10%. Nonetheless, we conducted multilevel modeling given the nature of our research question (i.e., about race, which is undoubtedly shaped across levels of structural racism). Analyses were conducted using the statistical software package SAS 9.4.

Results

On skin color ratings, 54% of children were rated as “moderately dark,” followed by “honorary white” (35%) and “collective black” (11%). The majority (73%) of Mexican-origin children were rated as “moderately dark,” and 27% were rated as “honorary white” on skin color ratings; none were rated as “collective black.” Among Dominican-origin children, 47% were rated “honorary white,” 27% were rated “moderately dark,” and 27% were rated “collective black.” Using these classifications and child gender, we examined mental health functioning. Descriptive statistics and group differences are presented in Table 1. Boys presented with higher levels of teacher- and mother-rated problems than girls on anxiety, hyperactivity and aggression. Children rated as “collective black” presented with higher levels of teacher- and mother-rated behavior problems than children rated as “honorary white” or “moderately dark,” especially on externalizing behaviors. Among children rated as “collective black,” 20% were rated in the atrisk clinical range for hyperactivity, and 15% to 17% were rated in the at-risk clinical range for aggression. In contrast, 10% to 12% of lighter-skinned children were rated as high on hyperactivity, and only 3% to 7% were high on aggression. We also conducted McNemar tests (Adedokun, & Burgess, 2012; Stokes, Davis, & Koch, 2012) to compare rates of risk across group (white, dark, black) and time (from T1 to T2). Findings showed that the rate of children at risk at both timepoints, and the rate of children who became at risk was higher among those whose skin color was rated “collective black” compared to those whose skin color was rated “honorary white” or “moderately dark.” This pattern was true in all domains of functioning. For example, 8% of “black” children, relative to 2% of “white” children, were rated as aggressive by teachers at both timepoints, and 9% (compared to 5% of “white” children) became at risk from Time 1 to Time 2.

Table 1.

Internalizing and Externalizing Behaviors in First Grade, by Skin Color and Gender

| Skin Color | Gender: Boys | Gender: Girls | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| “White” (n=240) | “Dark” (n=367) | “Black” (n=77) | All (n=331) | White (n=105) | Dark (n=182) | Black (n=44) | All (n=353) | White (n=135) | Dark (n=185) | Black (n=33) | |

| ANXIETY | |||||||||||

| T-score, Teacher (M; SD) | 46.95 (10.09) | 47.00 (10.56) | 46.17 (9.73) | 47.56 (10.87) | 48.23 (11.54) | 47.65 (10.83 | 45.60 (9.24) | 46.26 (9.70) | 45.96 (8.73) | 46.36 (10.26) | 46.93 (10.46) |

| % at-risk | 9.17 | 10.71 | 10.65 | 8.90 | 13.05 | 11.65 | 7.27 | 11.51 | 6.15 | 9.78 | 15.15 |

| χ2 value | 0.75 | 2.47 | 5.04 | ||||||||

| T-score, Mother (M; SD) | 55.95 (10.40) | 56.81 (7.23) | 57.21 (7.65) | 56.89 (8.00) | 56.15 (9.83) | 57.21 (7.65) | 57.29 (7.77) | 56.42 (7.00) | 55.79 (6.62) | 56.41 (6.74) | 59.00 (9.40) |

| % at-risk | 33.75 | 36.10 | 42.21 | 33.97 | 39.71 | 36.92 | 39.09 | 38.10 | 29.11 | 35.30 | 46.36 |

| χ2 value | 2.74 | 0.29 | 6.15* | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| DEPRESSION | |||||||||||

| T-score, Teacher (M; SD) | 47.15 (7.62) | 46.58 (9.27) | 47.74 (10.79) | 47.53 (10.29) | 47.98 (9.83) | 47.35 (10.48) | 47.18 (10.63) | 46.34 (8.75) | 46.51 (9.57) | 45.82 (7.26) | 48.49 (11.13) |

| % at-risk | 4.71 | 5.40 | 9.87 | 5.07 | 6.67 | 5.99 | 6.59 | 6.28 | 3.19 | 4.81 | 14.24 |

| χ2 value | 7.38* | .25 | 8.80* | ||||||||

| T-score, Mother (M; SD) | 48.77 (8.89) | 49.25 (8.03) | 49.96 (12.03) | 49.12 (9.81) | 48.24 (9.37) | 49.63 (9.14) | 49.14 (12.96) | 49.14 (7.57) | 49.19 (7.80) | 48.87 (6.54) | 51.07 (10.80) |

| % at-risk | 12.25 | 10.35 | 14.16 | 11.10 | 11.71 | 11.92 | 11.59 | 11.81 | 12.67 | 8.81 | 17.58 |

| χ2 value | 0.38 | 0.31 | 1.54 | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| HYPERACTIVITY | |||||||||||

| T-score, Teacher (M; SD) | 48.07 (9.73) | 47.47 (10.69) | 51.23 (11.49) | 49.86 (11.05) | 49.39 (11.01) | 49.75 (10.87) | 51.44 (12.04) | 46.45 (10.34) | 47.04 (9.94) | 45.22 (10.53) | 50.97 (10.81) |

| % at-risk | 12.46 | 9.59 | 20.26 | 7.51 | 17.24 | 15.16 | 19.32 | 16.37 | 8.74 | 4.11 | 21.52 |

| χ2 value | 7.35* | 1.37 | 13.30** | ||||||||

| T-score, Mother (M; SD) | 48.56 (8.51) | 49.25 (8.30) | 52.54 (8.59) | 50.09 (8.60) | 49.00 (9.03) | 50.38 (8.38) | 51.47 (8.54) | 48.72 (8.48) | 48.23 (8.78) | 48.14 (8.23) | 53.96 (8.67) |

| % at-risk | 10.46 | 10.54 | 19.87 | 8.95 | 14.10 | 14.07 | 16.14 | 14.35 | 7.63 | 7.08 | 24.85 |

| χ2 value | 5.1 | 0.08 | 14.65** | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| AGGRESSION | |||||||||||

| T-score, Teacher (M; SD) | 47.15 (8.54) | 46.66 (7.85) | 49.94 (11.29) | 48.35 (8.59) | 48.04 (8.57) | 47.98 (8.09) | 50.60 (10.42) | 46.12 (8.55) | 46.46 (8.48) | 45.35 (7.45) | 49.07 (12.40) |

| % at-risk | 7.46 | 6.29 | 17.40 | 5.01 | 10.95 | 9.95 | 16.14 | 11.09 | 4.74 | 2.70 | 19.09 |

| χ2 value | 4.27 | 0.37 | 15.85*** | ||||||||

| T-score, Teacher (M; SD) | 45.04 (7.45) | 45.26 (7.84) | 48.44 (10.55) | 46.14 (7.60) | 45.72 (7.14) | 45.90 (7.22) | 48.16 (9.74) | 44.98 (8.55) | 44.52 (7.67) | 44.63 (8.38) | 48.80 (11.68) |

| % at-risk | 3.46 | 3.57 | 14.68 | 5.30 | 2.86 | 3.19 | 11.82 | 4.23 | 3.93 | 3.95 | 18.48 |

| χ2 value | 21.89*** | 3.62 | 12.88** | ||||||||

Note.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Tables 2 and 3 summarize the results of regression models predicting internalizing behavior in first grade among boys (Table 2) and girls (Table 3). As expected, internalizing behavior at baseline predicted internalizing behavior at follow-up, but not in the teacher-rated anxiety model. However, skin color was not significantly associated with teacher- or mother-ratings of anxiety or depression in first grade, and there was no evidence of an interaction effect between mental health at baseline and skin color.

Table 2.

Regression Model Assessing the Association between Skin Color and Internalizing Behaviors among Boys

| Anxiety | Depression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | Beta | b | SE | Beta | |

| Teacher-Rated Internalizing Behaviors | ||||||

| MA children (ref.: DA children) | 2.34 | 1.61 | 0.22 | −0.46 | 1.18 | −0.06 |

| Kindergarten (ref.: pre-kindergarten) | 1.41 | 1.45 | 0.13 | 1.63 | 1.00 | 0.21 |

| Family income-to-needs ratio | 1.33 | 0.92 | 0.10 | −0.43 | 0.65 | −0.05 |

| Skin color (ref.: honorary white) | ||||||

| Moderately dark | −0.46 | 0.80 | −0.09 | −0.27 | 0.56 | −0.07 |

| Collective black | −0.52 | 1.22 | −0.10 | −0.48 | 0.85 | −0.12 |

| Teacher-rated behavior problems at baseline | 0.31 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 0.38 | 0.10 | 0.41** |

| Moderately dark skin color × behavior problems at baseline | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.01 |

| Collective black skin color × behavior problems at baseline | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.02 |

| Mother-Rated Internalizing Behaviors | ||||||

| MA children (ref.: DA children) | 0.55 | 1.31 | 0.05 | 2.52 | 1.13 | 0.29* |

| Kindergarten (ref.: pre-kindergarten) | −1.48 | 1.07 | −0.13 | 0.29 | 0.94 | 0.03 |

| Family income-to-needs ratio | −0.14 | 0.72 | −0.01 | −0.34 | 0.59 | −0.03 |

| Skin color (ref.: honorary white) | ||||||

| Moderately dark | 0.21 | 0.70 | 0.04 | 0.37 | 0.55 | 0.08 |

| Collective black | −0.05 | 0.91 | −0.01 | 0.88 | 0.82 | 0.20 |

| Mother-rated behavior problems at baseline | 0.61 | 0.08 | 0.63*** | 0.40 | 0.07 | 0.52*** |

| Moderately dark × behavior problems at baseline | −0.06 | 0.06 | −0.06 | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.03 |

| Collective black × behavior problems at baseline | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.03 |

Note.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Table 3.

Regression Model Assessing the Association between Skin Color and Internalizing Behaviors among Girls

| Anxiety | Depression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | Beta | b | SE | Beta | |

| Teacher-Rated Internalizing Behaviors | ||||||

| MA children (ref.: DA children) | 2.94 | 1.42 | 0.30 | −0.10 | 0.97 | −0.01 |

| Kindergarten (ref.: pre-kindergarten) | 0.93 | 1.24 | 0.10 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.12 |

| Family income-to-needs ratio | 0.33 | 0.74 | 0.03 | −0.15 | 0.53 | −0.02 |

| Skin color (ref.: honorary white) | ||||||

| Moderately dark | −0.38 | 0.74 | −0.08 | −0.13 | 0.46 | −0.04 |

| Collective black | 0.88 | 1.33 | 0.18 | 0.47 | 0.76 | 0.13 |

| Teacher-rated behavior problems at baseline | 0.23 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.37 | 0.10 | 0.43** |

| Moderately dark skin color × behavior problems at baseline | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| Collective black skin color × behavior problems at baseline | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Mother-Rated Internalizing Behaviors | ||||||

| MA children (ref.: DA children) | −0.11 | 1.21 | −0.01 | 0.50 | 1.11 | 0.06 |

| Kindergarten (ref.: pre-kindergarten) | −1.18 | 0.97 | −0.11 | 1.08 | 0.97 | 0.13 |

| Family income-to-needs ratio | −0.94 | 0.74 | −0.07 | −0.67 | 0.61 | −0.06 |

| Skin color (ref.: honorary white) | ||||||

| Moderately dark | −0.14 | 0.57 | −0.03 | −0.59 | 0.52 | −0.14 |

| Collective black | 0.78 | 0.98 | 0.15 | 0.61 | 0.85 | 0.15 |

| Mother-rated behavior problems at baseline | 0.54 | 0.07 | 0.58*** | 0.35 | 0.07 | 0.47*** |

| Moderately dark skin color × behavior problems at baseline | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.05 |

| Collective black × behavior problems at baseline | −0.04 | 0.08 | −0.05 | −0.06 | 0.07 | −0.08 |

Note.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

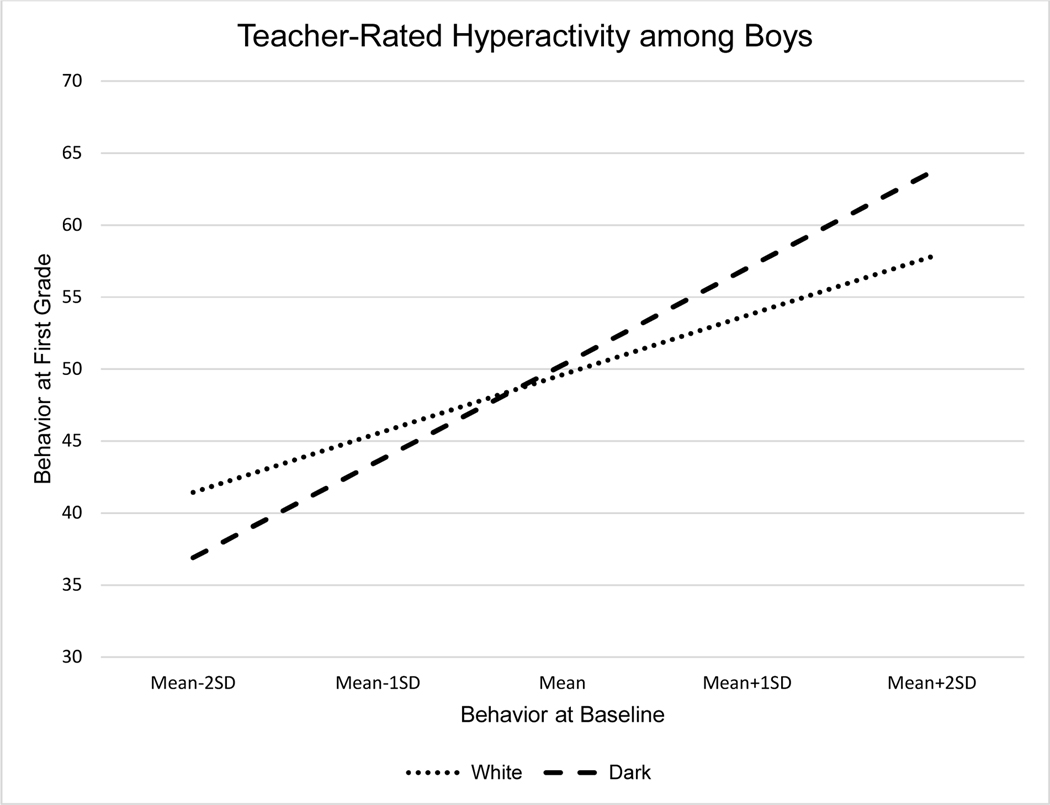

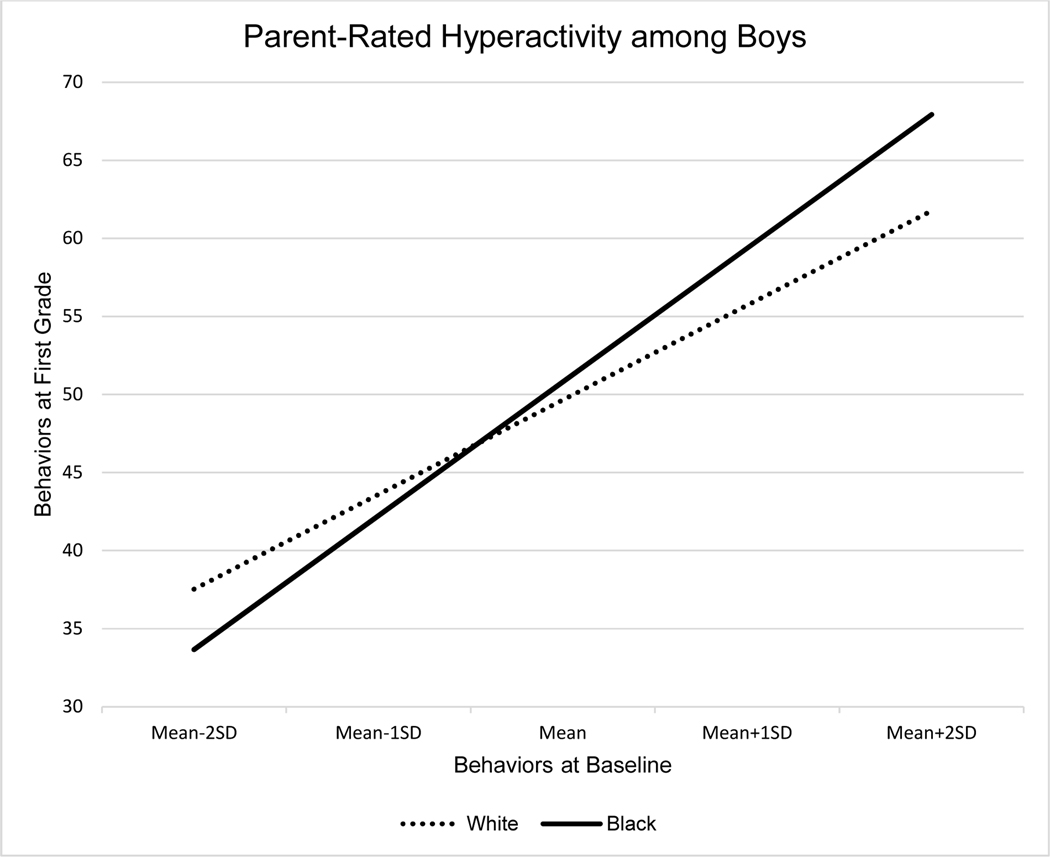

Table 4 summarizes the results of the regression models predicting externalizing behavior in first grade among boys. Externalizing behavior at baseline predicted externalizing behavior at follow-up in both models. In the teacher-rated hyperactivity model, there was no direct effect of skin color on teacher-rated hyperactivity at first grade, but the interaction term between moderately dark skin color and teacher-rated hyperactivity at baseline was significant (β = 0.13, p < .05). In the mother-rated hyperactivity model, skin color did not predict mother-rated hyperactivity at first grade, but the interaction between “collective black” skin color ratings and mother-rated hyperactivity at baseline was significant (β = 0.13, p < .05).

Table 4.

Regression Model Assessing the Association between Skin Color and Externalizing Behaviors among Boys

| Hyperactivity | Aggression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | Beta | b | SE | Beta | |

| Teacher-Rated Externalizing Behaviors | ||||||

| MA children (ref.: DA children) | 0.35 | 1.27 | 0.03 | −1.57 | 1.31 | −0.16 |

| Kindergarten (ref.: pre-kindergarten) | −0.80 | 1.27 | −0.08 | 0.21 | 1.13 | 0.02 |

| Family income-to-needs ratio | −0.76 | 0.74 | −0.06 | −1.32 | 0.74 | −0.11 |

| Skin color (ref.: honorary white) | ||||||

| Moderately dark | 0.14 | 0.62 | 0.03 | 0.19 | 0.68 | 0.04 |

| Collective black | 0.33 | 0.88 | 0.06 | 0.50 | 0.92 | 0.10 |

| Teacher-rated behavior problems at baseline | 0.73 | 0.10 | 0.70*** | 0.60 | 0.10 | 0.55*** |

| Moderately dark skin color × behavior problems at baseline | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.13* | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.05 |

| Collective black skin color × behavior problems at baseline | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.09 |

| Mother-Rated Externalizing Behaviors | ||||||

| MA children (ref.: DA children) | −1.35 | 0.94 | −0.15 | 1.39 | 0.96 | 0.18 |

| Kindergarten (ref.: pre-kindergarten) | 0.44 | 0.87 | 0.05 | 0.63 | 0.82 | 0.08 |

| Family income-to-needs ratio | −0.82 | 0.49 | −0.08 | −0.37 | 0.50 | −0.04 |

| Skin color (ref.: honorary white) | ||||||

| Moderately dark | 0.59 | 0.47 | 0.13 | −0.17 | 0.45 | −0.04 |

| Collective black | 0.37 | 0.69 | 0.08 | 0.87 | 0.68 | 0.22 |

| Mother-rated behavior problems at baseline | 0.63 | 0.05 | 0.78*** | 0.60 | 0.07 | 0.72*** |

| Moderately dark × behavior problems at baseline | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.02 |

| Collective black × behavior problems at baseline | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.13* | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.15 |

Note.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

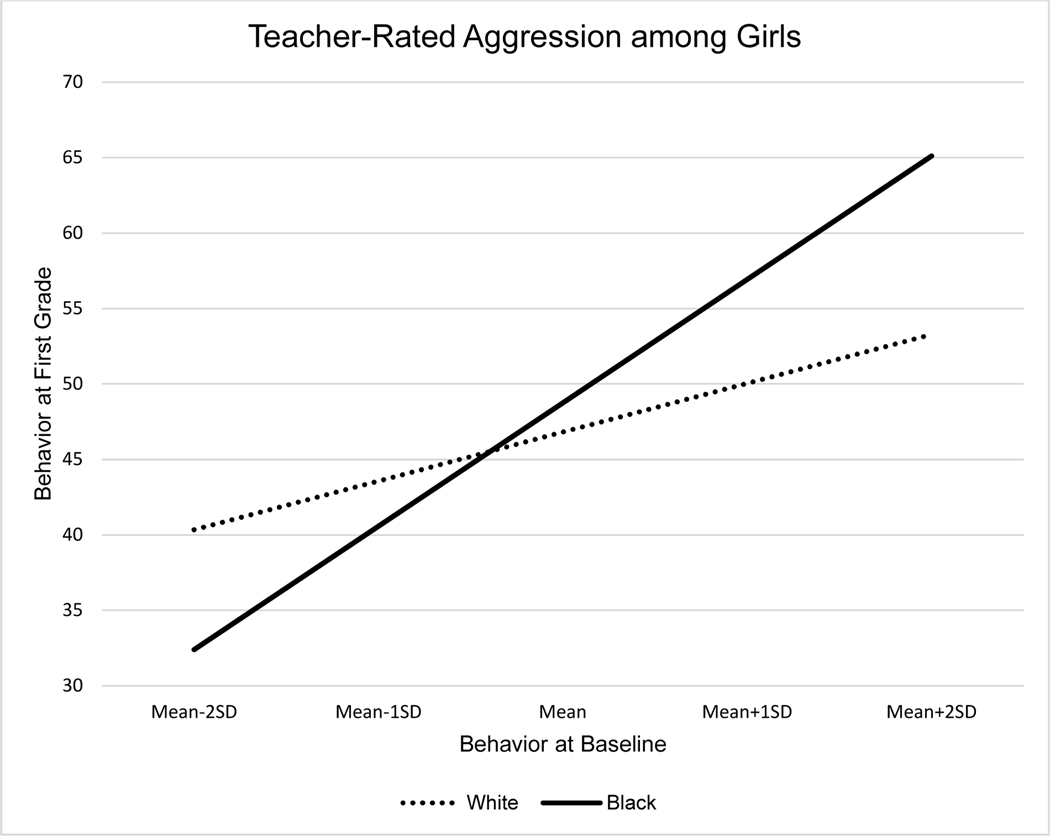

Table 5 presents the results of the regression models predicting externalizing behavior in first grade among girls. Externalizing behavior at baseline predicted externalizing behavior at follow-up in both models. Additionally, in the teacher-rated aggression model, there was no direct effect of skin color on teacher-rated aggression at first grade, but the interaction term between “collective black” skin color ratings and teacher-rated aggression at baseline was significant (β = 0.24, p < .05). Similar results were found for boys and girls in multilevel modeling.

Table 5.

Regression Model Assessing the Association between Skin Color and Externalizing Behaviors among Girls

| Hyperactivity | Aggression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | Beta | b | SE | Beta | |

| Teacher-Rated Externalizing Behaviors | ||||||

| MA children (ref.: DA children) | 0.01 | 1.23 | 0.00 | −0.32 | 1.09 | −0.04 |

| Kindergarten (ref.: pre-kindergarten) | 0.06 | 1.04 | 0.01 | 0.75 | 0.91 | 0.10 |

| Family income-to-needs ratio | −0.59 | 0.63 | −0.05 | −0.45 | 0.54 | −0.05 |

| Skin color (ref.: honorary white) | ||||||

| Moderately dark | −0.35 | 0.50 | −0.08 | −0.37 | 0.47 | −0.10 |

| Collective black | 1.17 | 0.98 | 0.27 | 0.61 | 0.91 | 0.16 |

| Teacher-rated behavior problems at baseline | 0.73 | 0.12 | 0.60*** | 0.68 | 0.10 | 0.63*** |

| Moderately dark skin color × behavior problems at baseline | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.06 | −0.03 |

| Collective black skin color × behavior problems at baseline | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.26 | 0.10 | 0.24* |

| Mother-Rated Externalizing Behaviors | ||||||

| MA children (ref.: DA children) | −1.46 | 1.02 | −0.17 | −1.30 | 0.98 | −0.15 |

| Kindergarten (ref.: pre-kindergarten) | 2.17 | 0.81 | 0.25* | 2.22 | 0.86 | 0.26* |

| Family income-to-needs ratio | −0.80 | 0.51 | −0.08 | 0.20 | 0.57 | 0.02 |

| Skin color (ref.: honorary white) | ||||||

| Moderately dark | −0.03 | 0.42 | −0.01 | 0.46 | 0.44 | 0.11 |

| Collective black | 0.34 | 0.77 | 0.08 | 1.39 | 0.86 | 0.33 |

| Mother-rated behavior problems at baseline | 0.71 | 0.08 | 0.79*** | 0.59 | 0.07 | 0.58*** |

| Moderately dark × behavior problems at baseline | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Collective black × behavior problems at baseline | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.01 |

Note.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Skin Color as a Moderator

We used post-hoc analyses to plot the interaction effects that were significant in our regression models. On boys’ teacher-rated hyperactivity the association between baseline and follow-up scores was stronger among boys with darker skin than those with honorary white skin. For “moderately dark” boys, teacher-rated hyperactivity at first grade increased by 0.71 point for every one-unit increase in hyperactivity (p < .001), compared with 0.44 for boys who were rated as “honorary white” (p < .001; Figure 2). Similarly, the association between mother-rated hyperactivity at baseline and at first grade was stronger for boys whose skin color was rated “collective black” (b = 0.75, p < .001) than for those who were “honorary white” (b = 0.53, p < .001; Figure 3). Finally, for “collective black” girls, teacher-rated aggression at baseline was more strongly associated with teacher-rated aggression at first grade (b = 0.96, p < .001) than for girls who were “honorary white” (b = 0.46, p < .001; Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Teacher-rated hyperactivity in boys over time: Moderation by skin color

Figure 3.

Parent-rated hyperactivity in boys over time: Moderation by skin color

Figure 4.

Teacher-rated aggression in girls over time: Moderation by skin color

Discussion

The development and well-being of Latinx children, as a population of color, is understood to reflect a myriad of social position factors that determine everyday experiences and opportunities (Garcia-Coll et al., 1996). While considerable progress has been made in the study of ethnicity as a key social position variable for Latinx populations, scholarship focused on race and racial phenotype remains limited. A number of recent studies show that among adults, phenotype is linked with an array of outcomes including mental health (Ayers et al., 2013; Cuevas et al., 2016; Montalvo & Codina, 2001; Perriera & Telles, 2014). Building on this literature, the present study examined skin color gradations and mental health in young children using an intersectional lens. Our findings show that dark skin is associated with higher risk for internalizing and externalizing mental health problems, especially among girls.

Skin Color and Mental Health Problems

Our first aim was to describe mental health problems based on skin color and gender using mother and teacher ratings of anxiety, depression, hyperactivity and aggression. Participant children experienced relatively high levels of problems at age 6, both at home and in school (see Table 1). Based on mother report, about 36% of children were at-risk for anxiety; 11% were at-risk for depression; 12% were at-risk for hyperactivity; and 5% were at-risk for aggression. Teacher ratings identified approximately 10% of children as experiencing anxiety; 5% as experiencing depression; 12% as experiencing hyperactivity; and 8% as experiencing aggression.

As expected, our descriptive data was consistent with the integrative model and intersectionality theory in suggesting that within the general Latinx child population, gender and racial phenotype placed children at varying levels of risk for mental health problems. Racial phenotype was operationalized by categorizing children’s skin color as white/honorary white (35%), brown/moderately dark (54%), or black/collective black (11%). Boys and children with the darkest skin tones received higher ratings across domains and raters (see Table 1). For example, teachers rated twice as many boys as hyperactive and aggressive, and approximately twice as many children with black skin tone as hyperactive and depressed. Strikingly, rates of mother-reported aggression were four times higher for children with black, compared with white and brown, skin tones.

Despite the higher risk observed among boys on the whole, skin color effects were most evident among girls. While caution is warranted given the small sample size, a clear picture of disproportionate risk emerged, with darker-skinned girls experiencing the highest level of mental health problems in every domain as reported by both mothers and teachers. Though unexpected, these findings are consistent with the idea of “gendered colorism,” which is rooted in societal notions of beauty that favor lighter skin tones in women of color. In this context, skin color serves as a critical and unique determinant of self-esteem for girls (Thompson & Keith, 2001), placing dark-skinned girls at risk of low self-esteem and concomitant psychological issues. Empirical evidence with Mexican-origin children supports self-esteem as a prospective risk factor for depression, and also suggests that self-esteem in this population is most vulnerable in the domain of physical appearance (e.g., relative to the domains of academic competence or peer relations; Orth et al., 2014). Other research shows that experiences of discrimination, which are most prevalent among dark-skinned girls, undermine self-esteem in Latinx youth (Zeiders et al., 2013). Research is needed to examine the extent to which self-esteem serves as an underlying mechanism in the link between dark skin color and mental health problems earlier in the development of Latinx children and among girls in particular.

It may also be that gendered colorism plays out in family dynamics. A recent study with Mexican-American families showed that mothers engage in more cultural socialization with their lighter-skinned girls, though no skin color effect was found for boys (Derlan et al., 2017). Likewise, a study with African-American families of adolescents (Landor et al., 2013) documented higher quality parenting for lighter-skinned, relative to darker-skinned, girls but not boys. Virtually nothing is known about these processes during early childhood, although issues of race and ethnicity are salient to young children and are commonly discussed in families starting at young ages (Brown et al., 2007). We are currently investigating whether the disproportionate risk observed among girls rated as black in the present study reflects underlying family processes (e.g., racial/ethnic/cultural socialization, harsh parenting practices).

Persistence of Mental Health Problems: Moderation by Skin Color

Our second aim was to test skin color as a moderator of the association between baseline and follow-up levels of mental health problems. As expected, internalizing and externalizing problems at baseline predicted similar problems approximately one year later, and those associations were stronger for children with darker skin, albeit not in all domains (see Tables 2 through 5). Specifically, boys with darker skin tones experienced greater increases in both teacher- and mother-rated hyperactivity, as did dark-skinned girls on teacher-rated aggression (see Figures 2 through 4). While we did not test the mechanisms by which skin color impacted mental health, we posit that darker-skinned children were subject to phenotypicality bias (i.e., colorism) that shaped the ways in which their mothers and teachers, regardless of their own phenotype, perceived them. According to this perspective, phenotypic characteristics, especially highly salient ones such as skin color, trigger (consciously or unconsciously) stereotypes of racial categories, which are then used to process information about the child (Maddox, 2004). Research shows that black children are viewed as more disruptive and aggressive, older, and more responsible for their behavior (Goff et al., 2014; Todd et al., 2016). Moreover, these negative perceptions have been shown to contribute to negative adult-child interactions (i.e., more conflict, less warmth), which exacerbate behavioral difficulties in young children (Madill et al., 2014; Neal et al., 2003; Skiba et al., 2011). These hypothesized mechanisms should be examined in future, longitudinal studies, with attention to parent- as well as teacher-child interactions.

It will also be important to examine the ways in which mothers, teachers and other adults involved in the socialization of Latinx children themselves experience racism. As immigrant Latinx women, the mothers in our study were most likely marginalized based on their immigrant, ethnic and racial status (Valdez & Golash-Boza, 2017; Viruell-Fuentes et al., 2012). The teaching workforce in the U.S. tends to be racially white, but regardless of individual characteristics, exists within an educational system stratified by race. These systemic forces are highlighted in cotemporary theories, but rarely the focus of empirical studies. In a recent call to action, scholars argued for more attention to the structural dimensions that are implicated in Garcia Coll et al.’s (1996) integrative developmental model (Seaton et al., 2018). We echo the need for future research that addresses how social stratification shapes the ways in which parents and teachers interact with children, both directly and indirectly via its impact on adults.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to the present study. First, we had some (n = 66) missing data on skin color, which may have been be non-random and led to biased results. Results may also have been biased by our categorical approach to our independent (i.e., skin color) and dependent (i.e., mental health) variables. Second, we had a relatively small sample of children who were coded as black (i.e., “collective black”), which limited our analytic power and introduced the possibility of type II errors. With better power, it is possible that more interaction effects would have emerged as statistically significant. Moreover, the participants in the black category were all ethnically Dominican. While this is consistent with the racial heritage of Dominican-origin, relative to Mexican-origin, children, it will be important to replicate the present study results with a larger sample of children with black skin color from various Latinx ethnicities (e.g., Puerto Rican, Cuban, Venezuelan). According to intersectionality theory, specific ethnic group membership may serve as an important social grouping variable such that generalizability between Latinxs with the same racial phenotype but from different countries cannot be assumed.

Third, our measure of race was limited to one phenotypic characteristic despite evidence that other features (i.e., nose width, hair texture) also shape how children are perceived and treated by others (Bonilla-Silva et al., 2003). Indeed, even skin color may be perceived differently by research staff than by those interacting with children in everyday contexts. Perceptions are undoubtedly influenced by myriad factors and even the ratings of research staff, all of whom were Latinx themselves, may have been biased in unknown ways. Fourth, we did not examine any of the potential mechanisms by which skin color may impact child functioning, namely phenotypicality bias and teacher-student and mother-child interactions. Future research should examine these underlying processes while acknowledging the potential bias of mother and teacher ratings based on the raters’ own racial identity and views. Thus, it may be beneficial to aggregate across raters to reduce bias and measurement error in future work. Fifth, our study focused narrowly on skin color, but current scholarship emphasizes the dynamic and complex interplay between risk and protective (i.e., individual, familial, cultural) factors across the lifespan. Of particular relevance to Latinx children, risk factors related to poverty (e.g., economic hardship, parental stress, limited access to care) and marginalization (e.g., undocumented status, linguistic and social isolation, discrimination), likely contributed to the high levels of mental health problems observed in the present study sample. More research on mental health in early childhood among Latinx children is needed to gain a more comprehensive understanding of developmental psychopathology in this population.

Conclusions and Future Directions

The present study is unique in examining the construct of race in the study of Latinx child mental health. Our findings have implications for developmental theory, preventive interventions and health disparities research. In the time since the integrative developmental theory called attention to social positionality as a critical determinant of child development (Garcia Coll et al., 1996), scholarship on race and ethnicity has burgeoned. Yet, the Latinx population continues to be treated as an ethnic group with little consideration for racial heterogeneity. Because race is in large part ascribed, Latinx children cannot avoid the implications of their racial phenotype. Our study is consistent with the integrative developmental theory in naming both race and ethnicity as social position variables but pushes the field to consider the nuanced ways in which these categories intersect for the Latinx population.

An intersectional lens may also inform preventive interventions. Scholarship with African American families has long emphasized the protective nature of racial socialization practices, whereby parents and other important adults teach children how to cope effectively with experiences of racial discrimination (Bentley et al., 2008; Jones & Neblett, 2016). Racial socialization promotes positive youth development by enhancing self-esteem, coping skills and a positive racial identity (Jones & Neblett, 2016). Recently, research on racial socialization has been used to inform the development of preventive interventions aimed at offsetting mental health problems among black youth. Preliminary evidence supports the efficacy of the Engaging, Managing and Bonding through Race program for black families of adolescents (Anderson & Stevenson, 2016; Anderson et al., 2018) and the Black Parents Strengths and Strategies program for black families of preschoolers (Coard et al., 2007), both which promote the use of racial problem solving in parents and children. The present study results suggest the need for similar programs for families of dark-skinned Latinx children. Given the markedly high levels of internalizing and externalizing problems described by mothers and teachers of the young children in our sample, such intervention efforts are urgently needed.

Supplementary Material

Research Highlights.

Aim was to understand race and mental health in Latino children.

Latino children, especially girls, with darker skin had more mental health problems.

Mental health problems increased more over time for children with darker skin color.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adames HY, Chavez-Dueñas NY, Organista KC, 2016. Skin color matters in Latino/a communities: identifying, understanding, and addressing Mestizaje racial ideologies in clinical practice. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 47, 46–55. 10.1037/pro0000062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adedokun OA, Burgess WD, 2012. Analysis of paired dichotomous data: a gentle introduction to the McNemar test in SPSS. J. MultiDiscip. Evaluat. 8, 125–131. [Google Scholar]

- Acalá HE, Montoya MF, 2018. Association of skin color and generation on arrests among Mexican-origin Latinos. Race Justice 8, 178–193. 10.1177/2153368716670998. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR, 1991. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Canino G, Shrout P, Woo M, Naihua DM, Vila D, Xiao-Li MM, 2008. Prevalence of mental illness in immigrant and non-immigrant U.S. Latino groups. Am. J. Psychiatry 165, 359–369. https://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07040704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Vallas M, Pumariega A, 2011. Racial and ethnic disparities in pediatric mental health. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 19, 759–774. 10.1016/j.chc.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RE, McKenny M, Mitchell A, Koku L, Stevenson HC, 2018. EMBRacing racial stress and trauma: preliminary feasibility and coping responses of a racial socialization intervention. J. Black Psychol. 44, 25–46. 10.1177/0095798417732930. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RE, Stevenson H, 2016. EMBRace Training Manual. Unpublished training manual prepared for the University of Pennsylvania–Graduate School of Education’s Racial Empowerment Collaborative, Philadelphia. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo B, Borrell L, 2006. Understanding the link between discrimination, life chances and mental health outcomes among Latinos. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 28, 245–266. 10.1177/0739986305285825. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arce CH, Murguia E, Frisbie WP, 1987. Phenotype and life chances among Chicanos. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 9 (1), 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ayers SL, Kulis S, Marsiglia FF, 2013. The impact of ethnoracial appearance on substance use in Mexican heritage adolescents in southwest United States. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 35, 227–240. 10.1177/0739986312467940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balagna RM, Young EL, Smith TB, 2013. School experiences of early adolescent Latinos/as at risk for emotional and behavioral disorders. Sch. Psychol. Q. 28 (2), 101–121. 10.1037/spq0000018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth JM, Dunlap ST, Dane H, Lochman JE, Wells KC, 2004. Classroom environment influences on aggression, peer relations, and academic focus. J. Sch. Psychol. 42, 115–133. 10.1016/j.jsp.2003.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer GR, 2014. Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Soc. Sci. Med. 110, 10–17. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley KL, Adams VN, Stevenson HC, 2008. Racial socialization: roots, processes, and outcomes. In: Neville HA, Tynes BM, Utsey SO (Eds.), Handbook of African American Psychology. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 255–267. [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Mick E, Faraone SV, Braaten E, Doyle A, Spencer T, et al. , 2002. Influence of gender on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children referred to a psychiatric clinic. Am. J. Psychiatry 159, 36–42. 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva E, Forman TA, Lewis AE, Embrick DG, 2003. It wasn’t me: how will race and racism work in 21st century America. Res. Political Sociol. 12, 111–134. 10.1016/S0895-9935(03)12005-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell LN, Crawford ND, 2006. Race, ethnicity, and self-rated health status in the behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 28, 387–403. 10.1177/0739986306290368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breland-Noble AM, 2013. The impact of skin color on mental and behavioral health in African American and Latina adolescent girls: a review of the literature. In: Hall RA. (Ed.), The Melanin Millennium. Springer Science + Business Media, New York, pp. 219–229. [Google Scholar]

- Brown DW, Tanner-Smith EE, Lesane-Brown CL, Ezell ME, 2007. Child, parent, and situational correlates of familial ethnic/race socialization. J. Marriage Fam. 69, 14–25. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00340.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burke M, 2008. Colorism. In: In: Darity W. (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, vol. 2. Thompson Gale, Detroit, MI, pp. 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Barajas-Gonzalez GR, Huang K, Brotman L, 2015. Early childhood internalizing problems in Mexican- and Dominican- origin children: the role of cultural socialization and parenting practices. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 46, 551–562. 10.1080/15374416.2015.1041593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Huang K, Anicama C, Fernandez Y, Brotman LM, 2012. Test of a cultural framework of parenting with Latino families of young children. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 18, 285–296. 10.1037/a0028694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016. National Survey of Children’s Health. Retrieved from. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/slaits/nsch.htm.

- Cheng TL, Goodman E, 2015. Race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status in research on child health. Pediatrics 135, 225–237. http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2014-3109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coard SI, Foy-Watson S, Zimmer C, Wallace A, 2007. Considering culturally relevant parenting practicing in intervention development and adaptation: a randomized controlled trial of the black parenting strengths and strategies (BPSS) program. Counsel. Psychol. 35, 797–820. 10.1177/0011000007304592. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Bullock A, Archbell KA, Bosacki S, 2015. Preschool teachers’ attitudes, beliefs, and emotional reactions to young children’s peer group behaviors. Early Child. Res. Q. 30, 117–127. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K, 1989. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Anti-racist Politics, vol. 14. University of Chicago Legal Forum, pp. 538–554. [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas AG, Dawson BA, Williams DR, 2016. Race and skin color in Latino health: an analytic review. Am. J. Public Health 12, 2131–2136. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darity WA, Boza TG, 2004. Choosing Race: Evidence from the Latino National Political Survey (LNPS, 1989–1990). Population Association of American Annual Meeting, Boston. http://paa2004.princeton.edu/papers/41644. [Google Scholar]

- Darity WA, Dietrich J, Hamilton D, 2005. Bleach in the rainbow: Latin ethnicity and preference for whiteness. Transform. Anthropol. 13, 103–109. 10.1525/tran.2005.13.2.103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Casanova EM, 2004. “No ugly women”: concepts of race and beauty among adolescent women in Ecuador. Gend. Soc. 18, 287–308. 10.1177/0891243204263351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Derlan CL, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Updegraff KA, Jahromi LB, 2017. Longitudinal relations among Mexican-origin mothers’ cultural characteristics, cultural socialization, and 5-year-old children’s ethnic-racial identification. Dev. Psychol. 53, 2078. 10.1037/cdp0000176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon AR, Telles EE, 2017. Skin color and colorism: global Research, concepts, and measurement. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 43, 405–424. 10.1146/annurevsoc-060116-053315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duster T, 2008. Introduction to unconscious racism debate. Soc. Psychol. Q. 71, 6. 10.1177/019027250807100102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Egger HL, Angold A, 2006. Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. JCPP (J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry) 47, 313–337. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkut S, Szalacha LA, García Coll C, Alarcón O, 2000. Puerto Rican early adolescents’ self-esteem patterns. J. Res. Adolesc. 10, 339–364. 10.1207/SJRA1003_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JA, 2017. The race project. Researching race in the social sciences researchers, measures, and scope of studies. J. Race Ethn. Politics 2, 300–346. 10.1017/rep.2017.15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, et al. , 1996. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Dev. 67, 1891–1914. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0009-3920%28199610%2967%3A5%3C1891%3AAIMFTS%3E2.0.CO%3B2-K. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Ford CL, 2011. Structural racism and health inequities: old issues, new directions. Du. Bois Rev. 8, 115–132. 10.1017/S1742058X11000130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghandour RM, Sherman LJ, Vladutiu CJ, Ali MM, Lynch SE, Bitsko RH, Blumberg SJ, 2019. Prevalence and treatment of depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in US children. J. Pediatr. 206, 256–267. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam WS, Maupin AN, Reyes CR, Accavitti M, Schic F, September, 2016. Do early educators’ implicit biases regarding sex and race relate to behavior expectations and recommendations of preschool expulsions and suspensions? (Research Brief). Retrieved from. https://medicine.yale.edu/childstudy/zigler/publications/Preschool%20Implicit%20Bias%20Policy%20Brief_final_9_26_276766_5379_v1.pdf.

- Goff PA, Jackson MC, Di Leone BA, Culotta CM, DiTomasso NA, 2014. The essence of innocence: consequences of dehumanizing black children. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 106, 526–545. 10.1037/a0035663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golash-Boza T, Darity W, 2008. Latino racial choices: the effects of skin colour and discrimination on Latinos’ and Latinas’ racial self-identifications. Ethn. Racial Stud. 31, 899–934. 10.1080/01419870701568858. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales-Backen MA, Umaña-Taylor AJ, 2011. Examining the role of physical appearance in Latino adolescents’ ethnic identity. J. Adolesc. 34, 151–162. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman A, Koons A, Postolache T, 2009. Suicidal behavior in Latinos: focus on the youth. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 21, 431–439 PMID: 20306758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgunseth LC, Ispa JM, Rudy D, 2006. Parental control in Latino families: an integrated review of the literature. Child Dev. 77, 1282–1297. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton E, Berger Cardoso J, Hummer R, Padilla Y, 2011. Assimilation and emerging health disparities among new generations of U.S. children. Demogr. Res. 25, 783–818. 10.4054/DemRes.2011.25.25. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hersch J, 2008. Profiling the new immigrant worker: the effects of skin color and height. J. Labor Econ. 26, 345–386. 10.1086/587428. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hicken MT, Kravitz-Wirtz N, Durkee M, Jackson JS, 2019. Racial inequalities in health: framing future research. Soc. Sci. Med. 199, 11–18. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzigsohn J, Giorguli SE, Vazquez O, 2005. Immigrant incorporation and racial identity: racial self-identification among Dominican immigrants. Ethn. Racial Stud. 28, 50–78. 10.1080/0141984042000280012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CT, Neblett EW, 2016. Racial-ethnic protective factors and mechanisms in psychosocial prevention and intervention programs for black youth. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 19, 134–161. 10.1007/s10567-016-0201-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris W, 2018. Youth risk behavior surveillance — United States, 2017. MMWR Surveillance Summary 67 (8), 1–114 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Calzada EJ, 2018. Skin color and academic achievement in young, Latino children: impacts across gender and ethnic group. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 25, 220–231. 10.1037/cdp0000230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Poulton R, 2003. Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Arch. Gen. Psychiatr. 60, 709–717. 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittles RA, Santos ER, Oji-Njideka NS, Bonilla C, 2007. Race, skin color and genetic ancestry: implications for biomedical research on health disparities. Calif. J. Health Promot. 5, 9–23. http://www.cjhp.org/Volume5_2007/IssueSp/009-023-kittles.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Kizer J, 2017. Skin Color Stratification and the Family: Sibling Differences and the Consequences for Inequality (Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation).(UC Irvine, Irvine, CA). [Google Scholar]

- Landor AM, Simons LG, Simons RL, Brody GH, Bryant CM, Gibbons FX, et al. , 2013. Exploring the impact of skin tone on family dynamics and race-related outcomes. J. Fam. Psychol. 27, 817–826. 10.1037/a0033883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee VE, 2000. Using hierarchical linear modeling to study social contexts: the case of school effects. Educ. Psychol. 35, 125–141. 10.1207/S15326985EP3502_6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacLin MK, Herrera V, 2006. The criminal stereotype. N. Am. J. Psychol. 8, 197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Maddox KB, 2004. Perspectives on racial phenotype bias. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 8, 383–401. https://ase.tufts.edu/psychology/tuscLab/documents/pubsPerspective2004.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddox KB, Gray SA, 2002. Cognitive representations of black Americans: reexploring the role of skin tone. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 28, 250–259. 10.1177/0146167202282010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madill RA, Gest SD, Rodkin PC, 2014. Students’ perceptions of relatedness in the classroom: the roles of emotionally supportive teacher-child interactions, children’s aggressive-disruptive behaviors, and peer social preference. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 43, 86–105. [Google Scholar]

- Massey SD, Martin AJ, 2003. The NIS Skin Color Scale. Retrieved from. http://nis.princeton.edu/downloads/NIS-Skin-Color-Scale.pdf.

- Monk EP, 2015. The cost of color: skin color, discrimination, and health among AfricanAmericans. Am. J. Sociol. 121 (2), 396–444. 10.1086/682162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montalvo FF, Codina GE, 2001. Skin color and Latinos in the United States. Ethnicities 1, 321–341. 10.1177/146879680100100303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neal LI, McCray AD, Webb-Johnson G, Bridgest ST, 2003. The effects of African American movement styles on teachers’ perceptions and reactions. J. Spec. Educ. 37, 49–57. 10.1177/00224669030370010501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newheiser AK, Olson KR, 2012. White and black American children’s implicit intergroup bias. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 48, 264–270. 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noltmeyer AL, McCloughlin CS, 2010. Changes in exclusionary discipline rates and disciplinary disproportionality over time. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 25, 59–70. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ890566. [Google Scholar]

- Okonofua JA, Eberhardt JL, 2015. Two strikes: race and the disciplining of young students. Psychol. Sci. 26, 617–624. 10.1177/0956797615570365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth U, Robins RW, Widaman KF, Conger RD, 2014. Is low self-esteem a risk factor for depression? Findings from a Longitudinal study of Mexican-Origin Youth. Dev. Psychol. 50, 622–633. 10.1037/a0033817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, Elias A, Priest N, Pieterse A, Gee G, 2015. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 10, 1–48. 10.1371/journal.pone.0138511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreira KM, Telles EE, 2014. The color of health: skin color, ethnoracial classification, and discrimination in the health of Latin Americans. Soc. Sci. Med. 0, 241–250. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.05.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, La Paro KM, Payne C, Cox MJ, Bradley R, 2002. The relation of kindergarten classroom environment to teacher, family, and school characteristics and child outcomes. Elem. Sch. J. 102, 225–238. 10.1086/499701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pina AA, Silverman WK, 2004. Clinical phenomenology, somatic symptoms, and distress in Hispanic Latino and European American youths with anxiety disorders. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 33, 227–236. 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priest N, Paradies Y, Trenerry B, Truong M, Karlsen S, Kelly Y, 2013. A systematic review of studies examining the relationship between reported racism and health and wellbeing for children and young. Soc. Sci. Med. 95, 115–127. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez AG, Gallion KJ, Aguilar R, Dembeck ES, 2017. Mental Health and Latinx Kids: A Research Review. Retrieved from Salud America! website. https://saludamerica.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/FINAL-mental-health-research-review-912-17.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos B, Jaccard J, Guilamo-Ramos V, 2003. Dual ethnicity and depressive symptoms: implications of being black and Latino in the United States. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 25, 147–173. 10.1177/0739986303025002002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reece R, 2019. Color crit: critical race theory and the history and future of colorism in the United States. J. Black Stud. 00, 1–23. 10.1177/0021934718803735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Kamphaus RW, 2004. BASC-2: Behavior Assessment System for Children, second ed. AGS Publishing, Circle Pines, MN. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez C, 2000. Changing Race: Latinos, the Census, and the History of Ethnicity in the United States. New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB, Stern HS, Vehovar V, 1995. Handling “don’t know” survey responses: the case of the Slovenian plebiscite. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 90 (431), 822–828. [Google Scholar]

- Ryabov I, 2017. Phenotypic variations in violence involvement: results from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Race Soc. Probl. 9, 272–290. 10.1007/s12552-017-9213-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Gee GC, Neblett E, Spanierman L, 2018. New directions for racial discrimination research as inspired by the integrative model. Am. Psychol. 6 786–780. 10.1037/amp0000315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skiba RJ, Horner RH, Chung C, Rausch MK, May SL, Tobin T, 2011. Race is not neutral: a national investigation of African American and Latino disproportionality in school discipline. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 40, 85–107. [Google Scholar]

- Skiba RJ, Peterson RL, Williams T, 1997. Office referrals and suspension: disciplinary intervention in middle schools. Educ. Treat. Child. 20, 295–316. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42900491. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne JA, White IR, Carlin JB, Spratt M, Royston P, Kenward MG, Carpenter JR, 2009. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. Br. Med. J. 338, b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes M, Davis C, Koch G, 2012. Categorical Data Analysis Using SAS. SAS Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Tenenbaum HR, Ruck MD, 2007. Are teachers’ expectations different for racial minority than for European American students? A meta-analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 99, 253–273. 10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MS, Keith VM, 2001. The blacker the berry: gender, skin tone, self-esteem, and self-efficacy. Gend. Soc. 15, 336–357. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3081888. [Google Scholar]

- Todd AR, Thiem KC, Neel R, 2016. Does seeing faces of young black boys facilitate the identification of threatening stimuli? Psychol. Sci. 27, 384–393. 10.1177/0956797615624492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremmery S, Buitelaar JK, Steyaert J, Molenberghs G, Feron FJM, Kalff AC, et al. , 2007. The use of health care services and psychotropic medication in a community sample of 9-year-old schoolchildren with ADHD. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 16, 327–336. 10.1007/s00787-007-0604-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez Z, Golash-Boza T, 2017. Towards an intersectionality of race and ethnicity. Ethn. Racial Stud. 40, 2256–2261. 10.1080/01419870.2017.1344277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van der Heijden GJ, Donders ART, Stijnen T, Moons KG, 2006. Imputation of missing values is superior to complete case analysis and the missing-indicator method in multivariable diagnostic research: a clinical example. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 59, 1102–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ginkel JR, Linting M, Rippe RC, van der Voort A, 2019. Rebutting existing misconceptions about multiple imputation as a method for handling missing data. J. Personal. Assess. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderWeele TJ, Knol MJ, 2014. A tutorial on interaction. Epidemiol. Methods 3, 33–72. [Google Scholar]

- Varela RE, Sanchez-Sosa JJ, Biggs BK, Luis TM, 2008. Anxiety symptoms and fears in Hispanic and European American children: cross-cultural measurement equivalence. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 30, 132–145. 10.1007/s10862-007-9069-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Viruell-Fuentes EA, Miranda PY, Abdulrahim S, 2012. More than culture: structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Soc. Sci. Med. 75, 2099–2106. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Klitzing K, Dohnert M, Kroll M, Grube M, 2015. Mental disorders in early childhood. Deutches Arztebi Int. 112, 375–386. 10.3238/arztebl.2015.0375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]