Abstract

Scholars have long speculated that experiencing awe—an emotional state where people believe they are in the presence of something grand—might be beneficial for well-being. We explore a manifestation of awe that is unique to religion—awe of God. Drawing on a national sample from the United States, being in awe of God was associated with lower depression, higher life satisfaction, and better self-rated health, associations partially mediated by the sense of meaning in life. Awe of God may bolster well-being by allowing people to view their life according to the vastness and complexity of a divine plan.

Keywords: awe of God, depression, health, life satisfaction, meaning in life, mediation

INTRODUCTION

Awe is an emotional state that emerges when people believe they are in the presence of something grand that transcends their current frame of reference (Keltner & Haidt, 2003; Shiota et al., 2007). Awe also encompasses the wonder and amazement experienced when new, complex, and vast stimuli are encountered that cannot be incorporated into existing knowledge structures (Keltner & Haidt, 2003). A wide range of stimuli—including natural wonder to human art to historical artifacts to the virtues and talents of other people—can elicit awe (Bai et al., 2017; Stellar et al., 2018). Another catalyst of awe might be religion/spirituality (Schneider, 2009). As Krause and Hayward (2015) acknowledge, awe can also involve religious or spiritual matters and a particular target. In fact, these authors explicitly defined awe of God as being overwhelmed by the vastness of God’s creation, power, and wisdom.

Philosophers and contemporary psychologists have long speculated that experiencing awe might be beneficial for well-being and is an important component of a fulfilling and meaningful life (Chirico & Yaden, 2018; Stellar et al., 2018). The potential of this emotion has been deemed so vast that it has been linked to a wider process of transformation (Chirico et al., 2018), a self-transcendent experience that enables people to gain a different perspective on their life (Chirico & Yaden, 2018; Stellar et al., 2018). To date, however, only a small body of work has empirically tested the connection between awe and well-being. Two studies, for example, have shown that experiencing awe is associated with increases in life satisfaction (Krause & Hayward, 2015a; Rudd et al., 2012) as well as lower depression (Chirico & Gaggioli, 2021) and higher flourishing (Zhao & Zhang, 2022). Although awe has attracted the interest of many researchers in the past 20 years (Nelson-Coffey et al., 2019), this phenomenon is still “in need of research attention in the realm of well-being” (Barrett-Cheetham et al., 2016, pg.603).

Recently, within the positive psychology literature, interest in the unique pathways linking discrete positive emotions to well-being has emerged (Ryff & Singer, 2000; Barnett-Cheetham et al., 2016). Awe can improve well-being via several different mechanisms, including changes to the self-concept (Skalski, 2009), less self-focused attention and greater feelings of connection (Yaden et al., 2017), and a greater sense of meaning in life (Van Cappellen & Saroglou, 2012; Zhao & Zwang, 2022).

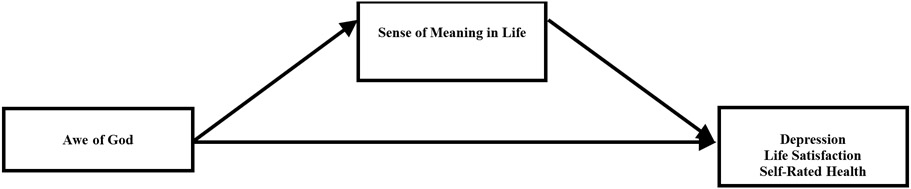

The purpose of the current study is to explore a manifestation of awe that is unique to religion—awe of God. More specifically, we examine the consequences to psychological and physical well-being of middle-aged and older adults of having awe of God, and whether the sense of meaning in life can help explain this relationship. According to our conceptual framework, awe of God is expected to increase a sense of meaning in life, which in turn, should contribute to the well-being of older adults in our national sample.

BACKGROUND

The Relationship Between Awe of God and Well-Being

The contemporary psychological understanding of awe is derived largely from foundational work by Keltner and Haidt (2003). According to the approach presented by these authors, the two cognitive appraisals central to awe are (a) the perception of vastness and (b) the need to mentally accommodate this vastness into existing mental schemas. In his writings over 100 years ago, Georg Simmel (1898/1997) squarely situated religion as a source of awe. Discussing the fundamental nature of religion, Simmel argued, “The individual feels himself bound to a universal, to something higher, from which he came and into which he will return, from which he differs and to which he is nonetheless identical” (pg.115).

Theoretical and theological discussions of awe of God have been present in previous woek (Keltner & Haidt 2003; Wettstein, 1997). In his writings on The Mediation of Christ, Torrance (1992, pg.26) states, “[i]f we are really to know God in accordance with his nature as he discloses himself to us…God may be known only in a godly way, in accordance with His nature of God.” Awe of God may therefore be one of the most fundamental aspects of religious faith because it helps believers to know God. According to Woznicki (2020), awe is the appropriate way to approach God. It is God’s presence that one senses “I am but dust and ashes.” Although an awe of God is a powerful religion emotion, the literature on this concept is vastly underdeveloped. As Emmons (2005) observed, there have been few empirical studies on awe of God specifically.

Why might awe of God be distinct from other catalysts of awe? Many investigators, for example, have explored awe of nature (Van Cappellen & Saroglou, 2012). In laboratory setting, descriptions of nature, in particular those involving panoramic views, were more likely to produce feelings of awe (Shiota et al., 2007; Seaton & Beaumont, 2015). However, awe of nature or art is not the same as awe of God, because people who are not religious nor believe in God may still be awed by nature. And having awe of God does not mean that a person will be awed by nature or human creations. While a complete examination of how awe of God differs from awe outside of the religious context is beyond the scope of the current study, some investigators maintain that any emotion may or may not be imbued with religious significance (Riis & Woodhead, 2010), so an attempt to isolate a purely religious emotion would be ill-advised.

In some limited research to date, a general sense of awe has been linked to greater psychological well-being. One study found that awe-related shifts away from one’s self were associated with a reduction of the stress in daily living, and elevate personal satisfaction (Bai et al., 2021). Another study by Anderson and colleagues (2018) found that an awe-inspiring experience of white-water rafting reduced participants’ stress-related symptoms and boosted both short-term and long-term well-being up to one week after the trip. In addition to the benefits observed for mental well-being, awe has also been found to be associated with better aspects of physical health. A greater sense of awe has been associated with lower levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6), a biomarker of the body’s inflammation response that is often brought about by stress (Stellar et al., 2015).

Awe tends to produce a “small-self”, a diminished sense of self relative to that which is vast (Bai et al., 2017; Stellar et al., 2018). This awe-related diminished sense of self has also been found to be associated with greater humility, prosociality, and connectedness to others (Piff et al., 2015; Rudd et al., 2012; Stellar et al., 2018), all elements that tend to promote greater well-being. Previous empirical work has found that awe exerts unique effects above and beyond other positive emotions such as amusement, joy, and pride—all of which are known to buffer stress and promote well-being (Bai et al., 2021).

As was noted above, experiences of awe hold a general relationship to religion, in that a host of religious experiences likely engender feelings of awe. These could include religious revelations, feelings of transcendence, and a sense of enlightenment (Kearns & Tyler, 2020). Past research has found that feelings of awe relate to several religious outcomes, such as increased church attendance, higher religious satisfaction, and an increased motivation to visit spiritual travel destinations (Krause & Hayward, 2015b; Van Cappellen et al., 2012). We are aware of only one prior study linking awe of God to well-being, as Krause and Hayward (2015a) found that awe of God was linked to higher life satisfaction.

A related concept to awe of God, referred to as “spiritual self-transcendence,” has been empirically linked to greater well-being. Spiritual self-transcendence refers to the capacity of individuals to remove themselves from their immediate sense of time and place, and to view life from a broader perspective (Piedmont et al., 2009). This type of self-transcendence is concerned with large and transcendent realities, such as God (Piedmont & Leach, 2002). A number of studies have shown that spiritual self-transcendence can help people maintain good mental health by increasing the subjective feeling that they are receiving more support (Jibeen et al., 2018), allowing them to retain a positive attitude (Johnstone et al., 2016) and enhance their well-being (Unterrainer et al., 2010). Showing its connection to awe of God, scholars in religious psychology have noted that aww in the context of religion itself invokes a spiritual and mystical experience (Van Cappellen & Saroglou, 2012), which supports the notion that awe may benefit spiritual self-transcendence.

Therefore, we expect similar reasons to underlie the relationship between a sense of awe of God and various aspects of well-being, including depression, life satisfaction, and self-rated health. Scholars across a host of disciplines, including psychology, theology, and sociology have proposed that awe-like events and people’s religious experiences may be uniquely related (Krause & Hayward, 2015a, 2015b; Van Cappellen et al., 2012). Since much of religious life contains reference to the all-powerful nature of God and God’s omnipotence, we would expect believers to report greater well-being the more they hold awe of God.

Sense of Meaning in Life as a Mediator

As we outlined in our conceptual framework, the sense of meaning in life is posited as a mediator in the possible association between awe of God and three dimensions of well-being. Broadly defined, the sense of meaning in life refers to the belief that one’s life or existence is coherent, significant, and scripted with a sense of purpose or mission (Martela & Steger, 2016; Steger, 2009). In the face of challenging life circumstances, a greater sense of meaning in life had been found to provide psychological resources for coping with stress (Floyd et al., 2013; Webster & Deng, 2015). Altogether, meaning in life has been recognized as a fundamental human need that matters for flourishing (Routledge & FioRito, 2021; Steger et al., 2009).

A growing body of research links the feeling and experience of self-transcendence with a greater sense of meaning in life (Howell et al., 2013). Because of its self-transcendental properties, awe has been shown to be associated with higher meaning in life (Zhao et al., 2019). One study found that participants who were induced with awe in a laboratory setting report a higher degree of meaning in life post-experimental manipulation (Hoeldtke, 2016). Awe may thus play a distinct role in meaning-making by broadening people’s thinking, and increasing the avenues through which people may find new positive meanings in life (Bonner & Friedman, 2011; Krause & Hayward, 2015b), in part by encouraging them to transcend mundane concerns (Van Cappellen & Saroglou, 2012). To date, scores of studies have revealed that meaning in life is associated with greater well-being (Aruta, 2021; Krok, 2018; Steger et al., 2009). An individual in a meaningless state is at risk of higher depression (Kleftaras & Psarra, 2012), while a higher sense of meaning in life can serve as a buffer against poor psychological health and risk behaviors (Brassai et al., 2011; Kleftaras & Psarra, 2012).

As it relates to non-religious awe, a recent study by Zhao and Zhang (2022) found that dispositional awe is positively associated with psychological flourishing among emerging adults, which was partially mediated by meaning in life. Positioned as a positive, self-transcendental emotion, awe broadens people’s understanding of life meaning, and prompts them to maintain a positive meaning in life (Zhao et al., 2019). As Fredrickson’s well-cited broaden-and-build theory suggests, the recurrent experience of positive emotions can broaden people’s perspectives and foster enduring personal resources that support human flourishing (Fredrickson et al., 2008; Garland et al., 2010).

In the religious realm, an individual’s perceived relationship with God bears close connection with a sense of meaning in life. Previous research has found that feelings of closeness to God portends an enhanced sense of life meaning and purpose (Culver, 2021; Culver & Denton, 2017; Upenieks, 2022), due in part to a greater sense of self-worth that is derived from a close relationship with God. While awe of God is certainly not reducible to a sense of closeness to God, Kenneth Pargament (1997) discusses the role of being in awe of God to make sense out of life events: “when the sacred is seen as working its will in life’s events, what first seems random, nonsensical, and tragic is changed into something else—an opportunity to appreciate life more fully.” The meaning in life that may derive from a transcendental view of God and His omnipotent power may explain any positive relationship between awe and greater well-being.

Finally, most Christian believers in the United States view God as the all-powerful, all-knowing ruler of the universe (Froese & Bader, 2010), a perfect being that is the architect of creation. A sense of awe of God is derived from these realizations. Although humans cannot attain such a lofty state, they can nevertheless use it as an ideal that is to be strived for, to be more “God-like.” This is also important for our study because having goals to strive for is a key component of a sense of meaning in life (Steger et al., 2009).

Figure 1 shows the conceptual framework that will be tested in the current study, including this mediation pathway.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model Linking Awe of God and Well-Being through Sense of Meaning in Life

The Role of Age in the Relationship between Awe of God and Well-Being

We use data that was provided by a sample of middle-age and older adults to assess the relationship between awe of God and well-being. Consequently, it is important to show why it is especially important to study the awe of God at these points in the life course.

First, a number of studies suggest that people become more deeply involved in religious/spiritual aspects as they get older (Krause, 2008). This suggests that being in awe of God might be more salient among older adults, and that meaning in life may have its origins in religious/spiritual sources later on in the life course. Indeed, a number of researchers suggest that maintaining a deep sense of meaning and purpose takes on additional importance in the final decades of life, as individuals transition out of the formal work force and may experience the death of close family members and friends. According to Erik Erikson’s (1959) theory of life course development, the life span is developed into eight stages. The final stage at the end of the life course is characterized by the crisis of integrity versus despair, a time of deep introspection when the older person tries to reconcile the kind of person they have become with what they intended to accomplish. Should this crisis be resolved successfully, the older adult develops a deep sense of meaning in life, and if not, they slip into despair.

As for middle-age adults, by the time many people reach midlife they have gotten married, had children, and found a vocation. Although all of these roles may provide a source of meaning (Burton, 1998; Sciaraffa, 2011), midlife and beyond may usher in new concerns about searching for meaning in a deeper or ultimate sense (Uecker, Mayrl, & Stroope, 2016). It is at this juncture that awe of God may fill a key age-related need. Thus, our nationwide sample of middle-aged and older adults provides a unique opportunity to examine the interrelationships between awe of God, a sense of meaning in life, and well-being.

DATA AND METHODS

The data for this study come from the Religion, Aging, and Health Survey, which is a nationwide survey of Whites and African Americans. To date, five waves of interviews have been conducted. The study population for the baseline survey was defined as all household residents who self-identify as black or white, and are non-institutionalized, English-speaking, and at least 66 years of age residing in the coterminous United States. Finally, the study population was restricted to currently practicing Christians, individuals who were Christian in the past but no longer practice any religion, and people who were not affiliated with any faith at any point in their lifetime. The sampling frame consisted of all eligible persons contained in the beneficiary list maintained by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

The sampling strategy for the Religion, Aging, and Health Survey is complex. The baseline survey took place in 2001. The data collection for all waves of interviews was conducted by Harris Interactive (New York). A total of 1500 interviews were completed, face-to-face, in the homes of the study participants. African Americans were oversampled so that sufficient statistical power would be available to assess racial cultural differences in religion. The overall response rate for the baseline survey was 62%. The baseline survey was followed up by a Wave 2 survey in 2003 (N = 1024; re-interview rate = 80%), Wave 3 in 2007 (N = 969; re-interview rate = 75%), and Wave 4 in 2008 (N = 718; re-interview rate = 88%).

A fifth wave of interviews was more recently completed in June of 2013. However, the sampling strategy for this round of interviews was complex. By the time Wave 5 interviews were conducted, 229 study participants were re-interviewed successfully. Many experienced significant illness that was associated with their advanced age (M = 83.2 years) and a number had died (N = 611). To retain sufficient statistical power to conduct meaningful analyses, the following two-part sampling strategy was employed. First, the research team interviewed as many of the original study participants as possible (N = 229). The re-interview rate for people who had participated in the study previously was 63%. Second, this group was supplemented with a new sample of individuals who had not participated in the survey previously (N = 1306). The same study population definition that was used at Wave 1 was used again at Wave 5. There was, however, one exception, in that age for eligibility ranged from 66 to 50. The following strategy was used to sample individuals who had not participated previously in the study. Based on the data in the 2010 census, 50 geographic areas (i.e., Census tracts) were selected to proportionately represent the population aged 50 and older and White or African American. All households within each Census tract were enumerated. One eligible person within each household was selected at random to participate in the study. The response rate for the individuals who had not participated in the study previously was 45%. Altogether, a total of 1535 individuals participated in the Wave 5 interviews.

We focus solely on the Wave 5 data in this study because we have argued in the previous section that when people reach midlife, they may begin to strive more actively for the kind of existential meaning that is fostered by religion. We went on to point out that the need for this kind of meaning intensifies in old age. If this reasoning is correct, we need a sample that includes both middle-aged and older people. Wave 5 is the only wave to contain both middle-aged and older adults, so the analyses presented below are based exclusively on the Wave 5 sample.

Dependent Variables

Depression:

Four items that measure a depressed affect were taken from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977). These indicators were as follows: (1) “I felt like I could not shake off the blues, even with the help of my family and friends,” (2) “I felt depressed,” (3) “I had crying spells,” and (4) “I felt sad. Responses were scored where 1 = “Strongly Disagree,” 2 = “Disagree,” 3 = “Agree,” and 4 = “Strongly Agree” and summed across all four items. A higher score on these items denotes a more depressed affect (α = .85).

Life Satisfaction:

Life satisfaction was assessed with three items that come from the scale that was devised by Neugarten et al. (1961) as well as one additional item. The items were: (1) “These are the best years of my life,” (2) “As I look back on my life, I am fairly well satisfied,” and (3) I would not change the past even if I could. These first three items were scored where 1 = “Strongly Disagree,” 2 = “Disagree,” 3 = “Agree,” and 4 = “Strongly Agree.” A final item asked, (4) “Now please think about your life as a whole. How satisfied are you with it?” Responses to this last item were scored in the following manner: 1 = “not very satisfied,” 2 = “not very satisfied,” 3 = “somewhat satisfied,” 4 = “very satisfied,” and 5 = “completely satisfied.” Scores were summed, creating a variable ranging from 4-17 where high scores denote greater life satisfaction (α =.73).

Self-Rated Health:

One item gauged self-rated health: “How would you rate your overall health at the present time?” This item was scored in the following manner: (1) “poor,” (2) “fair,” (3) “good,” (4) = “very good,” and (5) “excellent.”

Key Predictor Variables

Awe of God:

Awe of God was measured by the following six items, which were created by Krause (2002) after conducting qualitative interviews with older adult to learn more about what the phrase ‘awe of God’ means to them. These data were then used to either draft new indicators of awe or modify existing ones. The awe of God scale comprises the following items: (1) “The beauty of the world that God has made leaves me breathless,” (2) “It is mind-boggling to think that I am just a small part of the infinite universe that God has made,” (3) “I am astonished by how little I understand about the universe and all that is in it,” (4) “The unlimited power of God fills me with amazement,” (5) “The ageless and timeless nature of God fills me with awe,” and (6) “I am filled with wonder when I think about the limitless wisdom of God.” Responses were coded where 1 = “Strongly disagree,” 2 = “Disagree,” 3 = “Agree,” and 4 = “Strongly agree” and summed to form an index of awe of God (α = 0.75). Higher scores on these six items represent people who feel greater awe of God.

Meaning in Life:

Meaning was assessed using six items assessed on a 4-point scale (1 = strongly agree to 4 = strongly disagree) designed to assess the three dimensions of meaning: coherence (e.g., “I have a system of value and beliefs that guide my daily activities”), significance (e.g., “I feel like I have found a really significant meaning in my life”), and purpose (e.g., “In my life, I have clear goals and aims”) (see Krause, 2009; Krause & Hayward, 2014). High scores on this brief composite denote a greater sense of meaning in life. (α = 0.84).

Control Measures

Several additional covariates were included in all analyses. We control for the gender (male = 1) and marital status (married = 1; 0 = otherwise) of the respondent. We also adjust for the number of years of education the respondent had attained over their life course.

We also adjust for several religious covariates. First, we included a measure of church attendance as it is a predictor of awe (Krause & Hayward, 2015b), gauged by the question, “How often do you attend religious services?” Responses were initially coded into nine categories, but we ultimately coded attendance into a four-category variable, with (1) Never attends, (2) Attends yearly, (3) Attends monthly, and (4) Attends weekly or more. We also adjust for how often a respondent engaged in frequent prayer. This was coded into a four-category variable where (1) Never prays, (2) Prays monthly, (3) Prays weekly, and (4) Prays daily or more. Finally, we include adjustment for religious denomination at Wave 5. This was coded where (1) Protestant, (2) Catholic, and (3) Other Christian.

PLAN OF ANALYSIS

A series of regression models with robust standard errors were used to test our hypotheses. Depression and life satisfaction were analyzed with Ordinary Least Squares Regression (OLS). For our outcome of self-rated health, an ordered variable, we elected to also use linear regression for these models after verifying that results from ordinal logistic regression were identical. We used the linear model so that we could consistently employ the same mediation technique across all three outcomes. To test the indirect effect (IE) of sense of meaning in life on each of our focal relationships, we employ Sobel- mediation analyses (Hayes, 2013). Finally, listwise deletion was used to handle missing data, yielding a final sample size of 1168.

For each of our three outcomes, we conducted a series of three models. In Model 1, we regress each outcome on awe of God, adjusting for all study covariates. In Model 2, we add in the sense of meaning in life, adjusting for all covariates present in Model 1. We then conduct a Sobel-Goodman mediation test for the indirect effect of awe of God on each outcome variable, adjusting for all study covariates. We report the indirect effect, the corresponding Z-score and probability value, and the percent of the association between awe of God and the outcome that is explained by the meaning in life.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics on all study variables. We would highlight that the average score on the depression index was 6.11 (SD = 2.72) and ranged from 4-16, the mean life satisfaction score was 12.55 (SD = 2.56), ranging from 4-17, and the average self-rated health score was 4.10 (SD = 1.10), which corresponds to “very good” self-rated health. Participants also reported fairly high awe of God scores, with a mean of 21.03 (range = 6 to 24), and a standard deviation of 3.14. Also of note, sample respondents had an average meaning in life score of 21.09 (SD = 3.41), with a range of 6 to 24.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics, 2013 Religion, Aging, and Health Survey (N = 1168)

| Mean/% | S.D. | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | ||||

| Depression | 6.11 | 2.72 | 4 | 16 |

| Life Satisfaction | 12.55 | 2.56 | 4 | 17 |

| Self-Rated Health | 4.10 | 1.10 | 1 | 5 |

| Awe of God | 21.03 | 3.14 | 6 | 24 |

| Sense of Meaning in Life | 21.09 | 3.41 | 6 | 24 |

| Age | 63.28 | 11.65 | 50 | 102 |

| Education (years) | 13.08 | 2.24 | 3 | 20 |

| Married | 41.55 | |||

| Male | 39.35 | |||

| Black | 35.58 | |||

| Religious Affiliation | ||||

| Mainline Protestant | 40.79 | |||

| Catholic | 16.58 | |||

| Other | 42.64 | |||

| Religious Attendance | ||||

| Never Attends | 11.69 | |||

| Attends Yearly | 25.61 | |||

| Attends Monthly | 13.20 | |||

| Attends Weekly or More | 49.51 | |||

| Private Prayer | ||||

| Never Prays | 47.13 | |||

| Monthly Prayer | 39.14 | |||

| Weekly Prayer | 6.53 | |||

| Daily Prayer | 7.19 |

Note. Standard deviations are omitted for categorical variables.

Multivariable Regression Results

Results corresponding to depression (Table 2), life satisfaction (Table 3), and self-rated health (Table 4) are shown below as unstandardized coefficients. Results for mediation analyses for all three outcome variables are displayed in Table 5.

Table 2.

Unstandardized Coefficients for Awe of God and Depression, OLS Regression, 2013 Religion, Health, and Aging Survey (N = 1168)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Awe of God | −0.10** (0.03) |

−0.05 (0.03) |

| Meaning in Life | −0.05* (0.02) |

|

| Age | −0.01 0.01) |

−0.01 (0.01) |

| Education (years) | −0.11* (0.04) |

−0.10* (0.04) |

| Married | −0.62** (0.19) |

−0.60** (0.20) |

| Male | −0.30 (0.19) |

−0.23 (0.20) |

| Black | −0.20 (0.20) |

−0.11 (0.20) |

| Religious Affiliation a | ||

| Catholic | −0.03 (0.04) |

−0.03 (0.04) |

| Other Christian | −0.04 (0.03) |

−0.04 (0.03) |

| Religious Attendance b | ||

| Attends Yearly | −0.99* (0.46) |

−1.13* (0.48) |

| Attends Monthly | −1.51*** (0.38) |

−1.76*** (0.40) |

| Attends Weekly or More | −1.44** (0.45) |

−1.70*** (0.46) |

| Private Prayer | ||

| Monthly Prayer | 1.35* (0.65) |

1.77* (0.69) |

| Weekly Prayer | 1.42* (0.64) |

1.80** (0.68) |

| Daily Prayer | 1.35* (0.64) |

1.71* (0.69) |

| R2 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

Note.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001. Robust standard errors shown in parentheses.

Compared to Protestant

Compared to Never Attends

Compared to Never Prays

Table 3.

Unstandardized Coefficients for Awe of God and Life Satisfaction, OLS Regression, 2013 Religion, Health, and Aging Survey (N = 1168)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Awe of God | 0.08** (0.03) |

0.01 (0.04) |

| Meaning in Life | 0.14*** (0.04) |

|

| Age | 0.02* (0.01) |

0.02* (0.01) |

| Education (years) | 0.06 (0.04) |

0.05 (0.04) |

| Married | 0.75*** (0.17) |

0.75*** (0.18) |

| Male | 0.02 (0.17) |

−0.03 (0.17) |

| Black | 0.59** (0.18) |

0.41* (0.18) |

| Religious Affiliation a | ||

| Catholic | 0.06 (0.05) |

0.07 (0.05) |

| Other Christian | 0.10 (0.09) |

0.11 (0.09) |

| Religious Attendance b | ||

| Attends Yearly | 0.10 (0.41) |

0.19 (0.42) |

| Attends Monthly | 0.18 (0.33) |

0.37 (0.35) |

| Attends Weekly or More | 0.46 (0.39) |

0.62 (0.40) |

| Private Prayer | ||

| Monthly Prayer | −0.39 (0.59) |

−0.87 (0.61) |

| Weekly Prayer | 0.06 (0.58) |

−0.61 (0.60) |

| Daily Prayer | 0.48 (0.58) |

−0.26 (0.61) |

| R2 | 0.14 | 0.14 |

Note.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001. Robust standard errors shown in parentheses.

Compared to Protestant

Compared to Never Attends

Compared to Never Prays

Table 4.

Unstandardized Coefficients for Awe of God and Self-Rated Health, OLS Regression, 2013 Religion, Health, and Aging Survey (N = 1168)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Awe of God | 0.04*** (0.01) |

0.01 (0.01) |

| Meaning in Life | 0.08*** (0.01) |

|

| Age | 0.01 (0.01) |

0.01 (0.01) |

| Education (years) | −0.01 (0.01) |

−0.01 (0.01) |

| Married | −0.09 (0.06) |

−0.06 (0.05) |

| Male | −0.06 (0.06) |

−0.03 (0.05) |

| Black | 0.45*** (0.06) |

0.36**** (0.05) |

| Religious Affiliation a | ||

| Catholic | 0.12 (0.08) |

0.11 (0.09) |

| Other Christian | 0.10 (0.10) |

0.09 (0.10) |

| Religious Attendance b | ||

| Attends Yearly | 0.17 (0.13) |

0.15 (0.13) |

| Attends Monthly | 0.17 (0.11) |

0.12 (0.11) |

| Attends Weekly or More | 0.16 (0.13) |

0.08 (0.13) |

| Private Prayer | ||

| Monthly Prayer | 2.73*** (0.19) |

2.53*** (0.19) |

| Weekly Prayer | 2.95*** (0.19) |

2.68*** (0.19) |

| Daily Prayer | 3.00*** (0.19) |

2.67*** (0.19) |

| R2 | 0.42 | 0.47 |

Note.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001. Odds ratios shown. 95% confidence intervals shown in parentheses.

Compared to Protestant

Compared to Never Attends

Compared to Never Prays

Table 5.

Sobel-Goodman Mediation Analyses, Meaning in Life, 2013 Religion Health, and Aging Survey (N = 1168)

| Outcome | Indirect effect of Awe of God through Meaning in Life b(se) |

Z−score | % of Association Between Awe of God and Outcome Explained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | −0.04* (0.02) |

−2.16 p = 0.03 |

50.11% |

| Life Satisfaction | 0.11*** (0.02) |

6.38 p = .000 |

76.48% |

| Self-Rated Health | 0.08*** (0.01) |

12.70 p = .000 |

75.29% |

Note.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < .001

Beginning with depression, Model 1 of Table 2 shows that awe of God is related to lower depression (b = −0.10, p < .01). In Model 2, once the sense of meaning of life is added, the association between awe of God and depression is reduced to non-significance (b = −0.05, p > .05). On its own, for depression, the sense of meaning in life was significantly associated with depression in the negative direction (b = −0.05, p < .05). Results from a Sobel-Goodman mediation analysis show a significant indirect of awe of God through the sense of meaning in life (b = −0.04, p < .05). As shown in the last column of Table 5, the sense of meaning in life explains 50.11% of the association between awe of God and lower depression.

Moving next to life satisfaction, Model 1 of Table 3 shows that greater awe of God is significantly associated with higher life satisfaction (b = 0.08, p < .01), net of all study covariates. Once the sense of meaning in life is added in Model 2, this association between awe of God and life satisfaction is reduced to non-significance (b = 0.01, p > .05). Unlike with depression, there is a significant main association between the sense of meaning in life and higher life satisfaction (b = 0.14, p < .001). Looking at Table 5, we also see that Sobel-Goodman mediation analyses confirm this significant indirect pathway between awe of God and life satisfaction through sense of meaning in life (indirect effect: b = 0.11, p < .001). Indeed, the sense of meaning in life explains 76.48% of the pathway between awe of God and higher life satisfaction.

On our last outcome variable, self-rated health, we see an identical pattern emerge to life satisfaction. As shown in Model 1 of Table 4, awe of God is associated with better self-rated health (b = 0.04, p < .001), net of all study covariates. When the sense of meaning in life is introduced in Model 2, this association is reduced to non-significance (b = 0.01, p > .05). As with life satisfaction, the sense of meaning in life had a significant positive main association with self-rated health (b = 0.08, p < .001). Sobel-Goodman mediation analyses shown in Table 5 reveal a significant indirect effect of awe of God through meaning in life for self-rated health (b = 0.08. p < .001). A sense of meaning in life explained 75.29% of the association between awe of God and self-rated health.

DISCUSSION

Awe is an especially important element of religious life because it has the potential to jolt believers out of a sense of spiritual complacency—it puts fire into the way they practice their faith and it infuses their lives with a rich sense of meaning. It has long been speculated that awe may be beneficial for well-being, in large part because it is an important and fulfilling component of a meaningful life (Krause & Hayward, 2015b). For thousands of years, scholars have described the close connection between people’s spiritual experiences and awe-like emotions. For instance, the Bible describes witnessing the divine as an experience that can be accompanied by “terrifying wonder” (Acts 9:1-19, NIV). Modern empirical evidence has lent credence to these age-old insights, finding that feelings of awe are associated with religious beliefs and behaviors, including being in awe of the divine (God) (Krause & Hayward, 2015a; Van Cappellen & Saroglou, 2012). Drawing on a national sample of older adults, this study endeavored to examine a religious emotion—awe of God—that has received relatively little attention—and its associations with three indicators of well-being: depression, life satisfaction, and physical health. Recognizing the complexity inherent in how awe of God may predict greater well-being, we considered the sense of meaning in life as a possible mediator of this association. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time these relationships have been examined empirically.

The results from our study yield several important findings. First, we note that awe of God was associated with lower depression, greater life satisfaction and better self-rated health. Building on the seminal work by Keltner and Haidt (2003), the positive associations between awe of God and these two dimensions of well-being would be expected because being in awe of God involves both the perception of vastness and the need to mentally accommodate this vastness into one’s existing moral schemas. In his theological writings, Torrance (1992) suggests that being in awe of God is really the only way to truly know Him and is the appropriate way to approach the divine presence. Though prior research has found that a general sense of awe (e.g., of nature, art) is linked with greater mental and physical well-being (Anderson et al., 2018; Stellar et al., 2015) as well as a higher likelihood of flourishing (Huta & Ryan, 2010; Seaton & Beaumont, 2015), our study suggests that this is also true for being in awe of God. As several observers have noted, awe helps to promote a diminished sense of the self compared to that which seems vast (Bai et al., 2017; Stellar et al., 2018). The state of being in awe of God—which may also promote enhanced feelings of transcendence, and a sense of enlightenment (Kearns & Tyler, 2020), also relate to well-being consistent across all three outcomes. Experiencing this form of spiritual transcendence through awe of God can help people maintain better well-being by perceiving that they are receiving more support from this divine power (Jibeen et al., 2018) and allows them to retain a positive attitude and place stress and hardships in their proper perspective (Johnstone et al., 2016), helping to mitigate the deleterious effects of stress (Bai et al., 2017).

Given the consistent positive relationships between awe of God across several dimensions of well-being, we also sought to explore the pathways that might help explain this overall association. As we have learned from past research on awe, awe is a self-transcendent emotion that occurs when a person encounters a perceptually extraordinary stimuli that transcends one’s current cognitive frame (Keltner & Haidt, 2003; Shiota et al., 2007). We proposed that the sense of meaning in life was a plausible mediator of this association between awe of God and well-being, and indeed, for every outcome, this mediation pathway was supported. Awe of God was associated with lower depression, greater life satisfaction, and better self-rated health in part because it was associated with a greater sense of meaning in life, the belief that one’s life is coherent, significant, and has a sense of purpose (Steger, 2009).

Because of its self-transcendental properties, a general sense of awe has been found to be associated with a greater sense of meaning in life (Howell et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2019). Our study shows that this pathway helps to explain why greater awe of God is associated with higher well-being. Holding a sense of awe of God may help individuals find their purpose in life by allowing them to view their life according to the vastness and complexity of a divine plan. Believers may thus derive a great sense of meaning from holding this transcendental view of God, helping them to discern His will in their lives and to view life through a framework where it can be fully appreciated (Pargament, 1997). The sense of meaning in life was a consistent mediator of the relationship between awe of God and each of the three dimensions of religiosity considered, which aligns with previous research which has linked it with lower depression (Kleftaras & Psarra, 2002) and better physical health (Brassai et al., 2011). Being in awe of God, therefore, can help people to broaden their perspective, view their lives according to a divine narrative, and appreciate the vastness of the world beyond themselves—aspects that appear to be beneficial for the well-being of older adults.

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the novel contributions of the current study, researchers should bear in mind some of the shortcomings of the research presented here. First, the relationships between awe of God and well-being were assessed with data that were collected at one point in time. As a result, it is not possible to establish the causal ordering among the constructs in our analytic model, which were based on theoretical considerations alone. It is possible that people who are less depressed, report greater life satisfaction, and have better self-rated health are able to develop a greater sense of awe of God. Clearly this, as well as other causal assumptions embedded in our model (e.g., awe of God as causally prior to meaning in life) must be more rigorously evaluated with longitudinal data. In addition, longitudinal studies would allow us to detect whether there is a lasting association between awe of God and well-being or whether these benefits may be short-lived. Second, we would note that our data were provided by Christian (or formerly Christian) study participants. As a result, we cannot generalize the findings reported in the current study to individuals from other faith traditions.

Research on awe of God is in its infancy, and more research is clearly needed on its relationship with other measures of health and well-being as well as further mediating pathways. Our study focused on depression, life satisfaction, and self-rated health, which provided one of the most comprehensive lists of well-being indicators to date. Still, much more research is needed to examine if awe of God associates with other measures of physical health status (e.g., physical health burden, mortality) as well as other measures of psychological well-being. Self-esteem may be one promising candidate for future exploration: on the one hand, being in awe of God could be associated with lower self-esteem, because it could make a person feel small and perhaps insignificant. On the other hand, however, being in awe of God, interpreted within a religious framework, could help a person reframe this diminished sense of self by showing them they have an important place in a larger divine order, which could enhance feelings of self-worth. In addition, where we focused on the mediating role of a sense of meaning in life, other plausible mechanisms linking awe of God and well-being could be an enhanced sense of support (Bai et al., 2017) as well as enhanced personal resources (Rudd et al., 2012). Greater awe of God could also promote other emotions such as gratitude to God, which could also promote greater mental and physical well-being (Krause, 2006; Upenieks & Ford-Robertson, 2022).

CONCLUSION

In the presence of something vast that transcends our understanding of the current context, we find ourselves in the state of awe. Scholars have noted that this profound feeling may shift attention away from the self and generate a greater sense of meaning in life (Keltner & Haidt, 2003; Piff et al., 2015). Our results suggest that the religious dimension of awe, being in awe of God, has consistent associations with well-being among a sample of middle-aged and older adults from the United States. On the basis of these findings, people who are religious believers may be advised to foster awe towards God through means such as attending religious services (Krause & Hayward, 2015b) or via private devotional activities. Doing so may further enhance well-being by fostering a greater sense of meaning in life. By focusing on how awe of God may be associated with benefits to well-being, we hope to encourage other investigators to more deeply probe religious-based emotions that emanate from the core of the Christian faith.

Funding:

This research was support by a grants from the John Templeton Foundation and the United States Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging (Grant RO1 AG009221).

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Contributor Information

LAURA UPENIEKS, Department of Sociology, Baylor University.

NEAL M. KRAUSE, School of Public Health, University of Michigan

REFERENCES

- Anderson CL, Monroy M, & Keltner D (2018). Awe in nature heals: Evidence from military veterans, at-risk youth, and college students. Emotion, 18(8), 1195–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruta JJBR (2021). The quest to mental well-being: Nature connectedness, materialism and the mediating role of meaning in life in the Philippine context. Current Psychology, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y, Maruskin LA, Chen S, Gordon AM, Stellar JE, McNeil GD, & Keltner D (2017). Awe, the diminished self, and collective engagement: Universals and cultural variations in the small self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113(2), 185–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y, Ocampo J, Jin G, Chen S, Benet-Martinez V, Monroy M, … & Keltner D (2021). Awe, daily stress, and elevated life satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(4), 837–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett-Cheetham E, Williams LA, & Bednall TC (2016). A differentiated approach to the link between positive emotion, motivation, and eudaimonic well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(6), 595–608. [Google Scholar]

- Bonner ET, & Friedman HL (2011). A conceptual clarification of the experience of awe: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. The Humanistic Psychologist, 39(3), 222–235. [Google Scholar]

- Brassai L, Piko BF, & Steger MF (2011). Meaning in life: Is it a protective factor for adolescents’ psychological health? International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 18(1), 44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton RP (1998). Global integrative meaning as a mediating factor in the relationship between social roles and psychological distress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 39(3),201–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirico A, & Gaggioli A (2021). The potential role of awe for depression: Reassembling the puzzle. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 617715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirico A, & Yaden DB (2018). Awe: a self-transcendent and sometimes transformative emotion. In Lench H (ed.), The function of emotions. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Chirico A, Ferrise F, Cordella L, & Gaggioli A (2018). Designing awe in virtual reality: An experimental study. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culver J, & Lundquist Denton M (2017). Religious attachment and the sense of life purpose among emerging adults. Religions, 8(12), 274. [Google Scholar]

- Emmons RA (2005). Striving for the sacred: Personal goals, life meaning, and religion. Journal of Social Issues, 61(4), 731–745. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E (1959). Identity and the life cycle. New York: International University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Floyd FJ, Mailick Seltzer M, Greenberg JS, & Song J (2013). Parental bereavement during mid-to-later life: pre-to postbereavement functioning and intrapersonal resources for coping. Psychology and Aging, 28(2), 402–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Cohn MA, Coffey KA, Pek J, & Finkel SM (2008). Open hearts build lives: positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(5), 1045–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froese P, & Bader C (2010). America's Four Gods: What We Say about God--and What That Says about Us. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garland EL, Fredrickson B, Kring AM, Johnson DP, Meyer PS, & Penn DL (2010). Upward spirals of positive emotions counter downward spirals of negativity: Insights from the broaden-and-build theory and affective neuroscience on the treatment of emotion dysfunctions and deficits in psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 849–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culver J (2021). How consistency in closeness to God predicts psychological resources and life satisfaction: Findings from the National Study of Youth and Religion. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38(1), 103–123. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A (2013). An introduction to mediation, moderation and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeldtke RT (2016). Awesome implications: Enhancing meaning in life through awe experiences. (Doctoral dissertation), Montana State University-Bozeman, College of Letters & science. [Google Scholar]

- Howell AJ, Passmore HA, & Buro K (2013). Meaning in nature: Meaning in life as a mediator of the relationship between nature connectedness and well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(6), 1681–1696. [Google Scholar]

- Huta V, & Ryan RM (2010). Pursuing pleasure or virtue: The differential and overlapping well-being benefits of hedonic and eudaimonic motives. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11(6), 735–762. [Google Scholar]

- Jibeen T, Mahfooz M, & Fatima S (2018). Spiritual transcendence and psychological adjustment: The moderating role of personality in burn patients. Journal of Religion and Health, 57(5), 1618–1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone B, Cohen D, Konopacki K, & Ghan C (2016). Selflessness as a foundation of spiritual transcendence: Perspectives from the neurosciences and religious studies. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 26(4), 287–303. [Google Scholar]

- Kearns PO and Tyler JM (2020) Examining the relationship between awe, spirituality, and religiosity. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 10.1037/rel0000365 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keltner D, & Haidt J (2003). Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cognition and Emotion, 17(2), 297–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleftaras G, & Psarra E (2012). Meaning in life, psychological well-being and depressive symptomatology: A comparative study. Psychology, 3(04), 337–345. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N (2006). Gratitude toward God, stress, and health in late life. Research on Aging, 28(2), 163–183. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N (2008). Aging in the church: How social relationships affect health. West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Foundation Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, & Hayward RD (2015a). Assessing whether practical wisdom and awe of God are associated with life satisfaction. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 7(1), 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, & Hayward RD (2015b). Awe of God, congregational embeddedness, and religious meaning in life. Review of Religious Research, 57(2), 219–238. [Google Scholar]

- Krok D (2018). When is meaning in life most beneficial to young people? Styles of meaning in life and well-being among late adolescents. Journal of Adult Development, 25(2), 96–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martela F, & Steger MF (2016). The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(5), 531–545. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson-Coffey SK, Ruberton PM, Chancellor J, Cornick JE, Blascovich J, & Lyubomirsky S (2019). The proximal experience of awe. PloS one, 14(5), e0216780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI (1997). The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, research, practice. New-York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Piedmont RL, & Leach MM (2002). Cross-cultural generalizability of the Spiritual Transcendence Scale in India: Spirituality as a universal aspect of human experience. American Behavioral Scientist, 45(12), 1888–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Piedmont RL, Ciarrochi JW, Dy-Liacco GS, & Williams JE (2009). The empirical and conceptual value of the spiritual transcendence and religious involvement scales for personality research. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 1(3), 162–179. [Google Scholar]

- Piff PK, Dietze P, Feinberg M, Stancato DM, & Keltner D (2015). Awe, the small self, and prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(6), 883–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Riis O, & Woodhead L (2010). A sociology of religious emotion. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Routledge C, & FioRito TA (2021). Why meaning in life matters for societal flourishing. Frontiers in Psychology, 3925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd M, Vohs KD, & Aaker J (2012). Awe expands people’s perception of time, alters decision making, and enhances well-being. Psychological Science, 23(10), 1130–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, & Singer B (2000). Interpersonal flourishing: A positive health agenda for the new millennium. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(1), 30–44. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider KJ (2009). Awakening to awe: Personal stories of profound transformation. Plymouth, England: Jason Aronson. [Google Scholar]

- Sciaraffa S (2011). Identification, Meaning, and the normativity of social roles. European Journal of Philosophy, 19(1), 107–128. [Google Scholar]

- Seaton CL, & Beaumont SL (2015). Pursuing the good life: A short-term follow-up study of the role of positive/negative emotions and ego-resilience in personal goal striving and eudaimonic well-being. Motivation and Emotion, 39(5), 813–826. [Google Scholar]

- Shiota MN, Keltner D, & Mossman A (2007). The nature of awe: Elicitors, appraisals, and effects on self-concept. Cognition and Emotion, 21(5), 944–963. [Google Scholar]

- Simmel G (1997). A contribution to the sociology of religion. In Helle HJ (Ed.), Essays on religion: Georg Simmel (pp. 101–120). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. (Original published in 1898). [Google Scholar]

- Skalski JE (2009). The Epistemic Qualities of Quantum Transformation. Utah:Brigham Young University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF (2009). The pursuit of meaningfulness in life. In Lopez SJ (Ed.), Handbook of positive psychology (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stellar JE, John-Henderson N, Anderson CL, Gordon AM, McNeil GD, & Keltner D (2015). Positive affect and markers of inflammation: discrete positive emotions predict lower levels of inflammatory cytokines. Emotion, 15(2), 129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellar JE, Gordon A, Anderson CL, Piff PK, McNeil GD, & Keltner D (2018). Awe and humility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 114(2), 258–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrance TF, 1992, The mediation of Christ. Helmers & Howard, Colorado Springs, CO. [Google Scholar]

- Uecker JE, Mayrl D, & Stroope S (2016). Family formation and returning to institutional religion in young adulthood. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 55(2), 384–406. [Google Scholar]

- Unterrainer HF, Ladenhauf KH, Moazedi ML, Wallner-Liebmann SJ, & Fink A (2010). Dimensions of religious/spiritual well-being and their relation to personality and psychological well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(3), 192–197. [Google Scholar]

- Upenieks L (2022). Searching for meaning: religious transitions as correlates of life meaning and purpose in emerging adulthood. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 24(4), 414–434. [Google Scholar]

- Upenieks L, & Ford-Robertson J (2022). Give thanks in all circumstances? Gratitude toward God and health in later life after major life stressors. Research on Aging, 44(5-6), 392–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Cappellen P, & Saroglou V (2012). Awe activates religious and spiritual feelings and behavioral intentions. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 4(3), 223–236. [Google Scholar]

- Webster JD, & Deng XC (2015). Paths from trauma to intrapersonal strength: Worldview, posttraumatic growth, and wisdom. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 20(3), 253–266. [Google Scholar]

- Wettstein H (1997). Awe and the religious life: A naturalistic perspective. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 21, 257–280. [Google Scholar]

- Woznicki C (2020). The Awe of the Lord is the Beginning of Knowledge: The Significance of Awe for Theological Epistemology. The Expository Times, 131(4), 153–159. [Google Scholar]

- Yaden DB, Haidt J, Hood RW Jr, Vago DR, & Newberg AB (2017). The varieties of self-transcendent experience. Review of General Psychology, 21(2), 143–160. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, & Zhang H (2022). Why dispositional awe promotes psychosocial flourishing? An investigation of intrapersonal and interpersonal pathways among Chinese emerging adults. Current Psychology 10.1007/s12144-021-02593-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Zhang H, Xu Y, He W, & Lu J (2019). Why are people high in dispositional awe happier? The roles of meaning in life and materialism. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]