ABSTRACT

Azithromycin, a 15-membered ring macrolide, is among the recommended antimicrobials for treating invasive salmonellosis in humans. It is not approved for use in veterinary medicine. We analyzed the U.S. National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS) culture collections (~40,700) between 2011 and 2021 from food animals at slaughter and processing and retail meats, and identified 31 azithromycin-resistant Salmonella spp. with the first occurrence in 2015. These isolates belonged to 12 Salmonella serovars and possessed one or more macrolide resistance determinants: erm(42), mef(C), mph(A), mph(E), mph(G), and msr(E) or a point mutation (acrB_R717L), of which mph(A) was dominant (61.3%). Compared with azithromycin-susceptible controls, these determinants accounted for up to 256-fold MIC increases against azithromycin with MIC50 and MIC90 increased by 32- and 8-fold, respectively. We report the first detection of an mph(G)-mef(C)-mph(E)-msr(E)-containing Salmonella Agona isolate with very high-level azithromycin resistance (1,024 µg/mL) and the first detection of acrB_R717L accounting for azithromycin resistance in nontyphoidal Salmonella serovars in the United States. Plasmids of diverse replicon types were identified, with 86.2% carrying multidrug resistance including azithromycin and ceftriaxone, or decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin. This report also highlights an emerging mph(A)-containing (on an IncR plasmid) Salmonella Newport clone of cattle/beef origin with high-level azithromycin resistance (128 µg/mL) and decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin (0.25 µg/mL). Further work is needed to better understand the drivers of emerging azithromycin resistance in nontyphoidal Salmonella associated with food animal sources.

IMPORTANCE

Macrolides of different ring sizes are critically important antimicrobials for human medicine and veterinary medicine, though the widely used 15-membered ring azithromycin in humans is not approved for use in veterinary medicine. We document here the emergence of azithromycin-resistant Salmonella among the NARMS culture collections between 2011 and 2021 in food animals and retail meats, some with co-resistance to ceftriaxone or decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin. We also provide insights into the underlying genetic mechanisms and genomic contexts, including the first report of a novel combination of azithromycin resistance determinants and the characterization of multidrug-resistant plasmids. Further, we highlight the emergence of a multidrug-resistant Salmonella Newport clone in food animals (mainly cattle) with both azithromycin resistance and decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin. These findings contribute to a better understating of azithromycin resistance mechanisms in Salmonella and warrant further investigations on the drivers behind the emergence of resistant clones.

KEYWORDS: azithromycin, genome, multidrug, mutation, PacBio, plasmid, public health, resistance, Salmonella, sequencing

INTRODUCTION

Nontyphoidal Salmonella is a leading cause of foodborne diarrheal diseases worldwide (1). In the United States, an estimated 1.35 million Salmonella infections occur annually, resulting in an estimated 26,500 hospitalizations, 420 deaths, and $400 million in direct medical costs (2). Though usually self-limiting, antimicrobial therapy is necessary for extraintestinal Salmonella infections (1). Antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin (a fluoroquinolone drug), azithromycin (a 15-membered ring macrolide), and ceftriaxone (a third-generation cephalosporin) are sometimes used to manage severe salmonellosis (2). Resistant Salmonella infections can be more severe especially when resistance genes are present on plasmids bearing additional virulence mechanisms, leading to higher hospitalization rates and even deaths (2).

The use of azithromycin in treating salmonellosis is an exception to general macrolide indications, as membrane permeability barriers in Enterobacterales cause intrinsic resistance to most macrolides (3). Azithromycin, the first semisynthetic, 15-membered ring macrolide, is an azalide derived from the best known 14-membered erythromycin (4). Due to its favorable permeability, low toxicity, and broad antimicrobial activity, azithromycin is now one of the most frequently prescribed antibiotics for various Gram-negative infections in humans, including campylobacteriosis, salmonellosis, shigellosis, and traveler’s diarrhea (5 – 7). It is not approved for use in veterinary medicine including food animals. Historically, resistance to azithromycin has been rare in Salmonella (8). Mechanisms of resistance, which primarily include target alteration by mutations (at 23S rRNA position A2058 or A2059) or methylations (encoded by erm genes), drug modification by esterases (encoded by ere genes) or phosphotransferases (encoded by mph genes), and reduced drug concentration by efflux pumps (such as those encoded by mef genes), are not yet fully understood (9).

Established in 1996, the U.S. National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS) collects data on antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in enteric bacteria from humans, animals, and raw retail meats (10). Salmonella is a major pathogen tracked by NARMS, and azithromycin has been incorporated into the NARMS Gram-negative antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) plate since 2011 (10). As there are no Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI)-defined azithromycin breakpoint for nontyphoidal Salmonella, NARMS has established an interpretive standard for azithromycin resistance monitoring in Salmonella based on CLSI’s breakpoint for Salmonella Typhi (3). For routine genotypic AMR prediction in Salmonella, whole-genome sequencing (WGS) has been fully incorporated into the NARMS program (11), and long-read sequencing technologies, such as PacBio, have been used for further in-depth genomic analysis (12, 13). Out of approximately 34,200 and 6,500 Salmonella isolates NARMS recovered from food animals and retail meats between 2011 and 2021, respectively, we selected 31 azithromycin-resistant isolates for this study. We also included 14 azithromycin-susceptible isolates as controls: some possessed potential azithromycin resistance determinants; some had borderline MIC values for azithromycin; others were initially found to be azithromycin resistant but upon retesting were determined to be actually susceptible.

This study aimed to document the emergence of azithromycin resistance in NARMS Salmonella isolates from food animals and retail meats and elucidate the genetic determinants, predominantly on multidrug-resistant (MDR) plasmids, that were responsible for azithromycin resistance. For this work, we conducted AST using agar dilution with expanded azithromycin concentrations, performed short-read and long-read sequencing to identify AMR genes and their genomic contexts (surrounded by class 1 integrons and insertion sequence elements), and analyzed emerging azithromycin-resistant Salmonella clones using data available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

RESULTS

Metadata summary

Table 1 shows key metadata for all 45 Salmonella isolates examined in this study. The 31 azithromycin-resistant Salmonella represented 12 serovars (Agona, n = 2; Anatum, n = 1; Bredeney, n = 1; Derby, n = 1; I 4,[5],12:i:-, n = 8, Mbandaka, n = 1; Meleagridis, n = 1; Newport, n = 11; Ohio, n = 1; Schwarzengrund, n = 2; Senftenberg, n = 1; and Typhimurium, n = 1), of which Newport and I 4,[5],12:i:- were predominant. Each serovar had one unique multilocus sequence typing (MLST) sequence type (ST) except I 4,[5],12:i:-, which had three STs. Of these, two (ST34 and ST3224) differed by a single sucA allele, and the third previously uncharacterized ST differed from ST34 by another single allele purE. Most isolates (n = 28) were recovered from food animals at slaughter [13 cattle (8 products, 4 cecal, and 1 lymph node), 11 swine (9 cecal and 2 products), 2 chicken (products), 1 sheep (cecal), and 1 turkey (product)], and 3 from retail meats (2 pork chops and 1 ground turkey). The isolation years ranged from 2015 to 2021 (no azithromycin resistance was detected from 2011 to 2014) with all Salmonella Newport and most (75%) Salmonella I 4,[5],12:i:- detected from 2018 to 2021. The isolation locations spanned 18 U.S. states, which was led by Texas (n = 6).

TABLE 1.

Salmonella (n = 45) examined in this study from U.S. food animals at slaughter and processing and retail meats

| Serovar | Multilocus sequence type a | Isolate b c | Year | State | Source d | MIC (μg/mL) e | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azithromycin | Ceftriaxone | Ciprofloxacin | ||||||

| Test group (n = 31) | ||||||||

| Agona (n = 2) | 13 | 18IA01PC08-S2 (CVM f N18S0017) | 2018 | IA | Pork chop bone-in | 1024 | 16 | ≤0.015 |

| FSIS21821150 g | 2018 | NC | Comminuted turkey | 64 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.015 | ||

| Anatum (n = 1) | 64 | FSIS1710858 (F18S049) | 2017 | TX | Heifer (cecal) | 128 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.015 |

| Bredeney (n = 1) | 3806 | FSIS1702037 | 2017 | IL | Market swine (cecal) | 64 | ≤0.25 | 4 |

| Derby (n = 1) | 40 | 15MN07GT04-S (CVM N58646) | 2015 | MN | Ground turkey | 32 | ≤0.25 | 0.03 |

| I 4,[5],12:i:- (n = 8) | 34 | 17SC12PC01-S1 (CVM N17S1465) | 2017 | SC | Pork chop | 64 | ≤0.25 | 0.03 |

| FSIS11809860 | 2018 | VA | Market swine (cecal) | 64 | 16 | 1 | ||

| FSIS11920112 | 2019 | VA | Market swine (cecal) | 64 | ≤0.25 | 0.03 | ||

| FSIS11922707 | 2019 | NC | Market swine (cecal) | 128 | ≤0.25 | 0.5 | ||

| FSIS21925668 | 2019 | MI | Raw ground pork | 128 | ≤0.25 | 1 | ||

| 3224 | FSIS31901558 | 2019 | NY | Raw ground pork | 64 | ≤0.25 | 1 | |

| NF | FSIS1609549 (F18S030) | 2016 | IN | Market swine (cecal) | 512 | 8 | ≤0.015 | |

| FSIS12035116 | 2020 | SD | Market swine (cecal) | 128 | ≤0.25 | 0.06 | ||

| Mbandaka (n = 1) | 413 | FSIS11814474 | 2018 | IN | Market swine (cecal) | 128 | 32 | ≤0.015 |

| Meleagridis (n = 1) | 463 | FSIS1607675 | 2016 | KS | Raw intact beef | 64 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.015 |

| Newport (n = 11) | 132 | FSIS11814458 | 2018 | TX | Steer (cecal) | 128 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.015 |

| FSIS11816184 | 2018 | TX | Comminuted beef | 128 | ≤0.25 | 0.25 | ||

| FSIS31903059 | 2019 | UT | Raw intact beef | 128 | ≤0.25 | 0.25 | ||

| FSIS12027867 | 2020 | CA | Comminuted beef | 128 | ≤0.25 | 0.25 | ||

| FSIS12034723 | 2020 | TX | Comminuted beef | 128 | ≤0.25 | 0.25 | ||

| FSIS12105828 | 2021 | TX | Beef cow (cecal) | 128 | ≤0.25 | 0.25 | ||

| FSIS12106020 | 2021 | TN | Comminuted beef | 128 | ≤0.25 | 0.25 | ||

| FSIS12142912 | 2021 | CA | Mature sheep (cecal) | 128 | ≤0.25 | 0.25 | ||

| FSIS22130757 | 2021 | TX | Steer (lymph node) | 128 | ≤0.25 | 0.25 | ||

| FSIS32104969 | 2021 | WI | Comminuted beef | 128 | ≤0.25 | 0.25 | ||

| FSIS32105981 | 2021 | IL | Comminuted beef | 128 | ≤0.25 | 0.25 | ||

| Ohio (n = 1) | 329 | FSIS11808786 | 2018 | CA | Market swine (cecal) | 128 | ≤0.25 | 0.5 |

| Schwarzengrund (n = 2) |

96 | FSIS1608447 | 2016 | AL | Raw intact chicken | 128 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.015 |

| FSIS1609433 | 2016 | GA | Comminuted chicken | 128 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.015 | ||

| Senftenberg (n = 1) | 14 | FSIS11813680 | 2018 | KS | Steer (cecal) | 32 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.015 |

| Typhimurium (n = 1) | 19 | FSIS11704063 (F18S031) | 2017 | MN | Market swine (cecal) | 128 | ≤0.25 | 0.03 |

| Control group (n = 14) | ||||||||

| I 4,[5],12:i:- (n = 2) | 34 | 20MO07PC10-S1 (CVM N20S0154) c | 2020 | MO | Pork chop | 4 | ≤0.25 | 0.25 |

| 20SD07PC06-S1 (CVM N20S0157) | 2020 | ND | Pork chop | 4 | ≤0.25 | 0.25 | ||

| Infantis (n = 1) | NF | FSIS12033262 | 2020 | IA | Market swine (cecal) | 4 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.015 |

| Johannesburg (n = 2) | 471 | FSIS1709981 | 2017 | MO | Market swine (cecal) | 16 | ≤ 0.25 | 0.06 |

| 19MN02PC03 (CVM N19S0223) c | 2019 | MN | Pork chop | 8 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.015 | ||

| Kentucky (n = 2) | 152 | 11MD11CB03-S (CVM N38232) | 2011 | MD | Chicken breast | 4 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.015 |

| FSIS1609498 | 2016 | NY | Chicken carcass | 16 | 8 | 0.03 | ||

| Newport (n = 4) | 132 | FSIS21924576 | 2019 | TX | Raw intact beef | 4 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.015 |

| FSIS12033266 | 2020 | FL | Comminuted beef | 4 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.015 | ||

| FSIS12035959 | 2020 | TX | Steer (cecal) | 4 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.015 | ||

| FSIS22106147 | 2021 | MO | Comminuted beef | 4 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.015 | ||

| Reading (n = 1) | 412 | 21OH06GT03-S1 (CVM N21S0376) | 2021 | OH | Ground turkey | 4 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.015 |

| Typhimurium (n = 2) | 19 | FSIS11815075 | 2018 | KS | Heifer (cecal) | 16 | 8 | 0.5 |

| FSIS12032448 c | 2020 | NC | Bob veal (cecal) | 4 | 64 | ≤0.015 | ||

NF stands for not found, suggesting a new multilocus sequence type.

Alternative IDs are provided for some isolates because historically different IDs were used at NCBI or in the literature for designating these isolates and corresponding plasmids.

Three control isolates possessed nonfunctional azithromycin resistance genes.

For Food Safety and Inspection Service isolates, those without parentheses were from product sample testing at slaughter. Cecal and lymph node samples are not destined for food.

Breakpoints used were ≥32 mg/mL for azithromycin (a 15-membered ring macrolide) and ≥4 mg/mL for ceftriaxone (a third-generation cephalosporin). Decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin at ≥0.12 mg/mL was used as a marker for emerging fluoroquinolone resistance.

CVM, Center for Veterinary Medicine.

FSIS, Food Safety and Inspection Service.

MIC distributions by azithromycin resistance determinants

Table 2 shows MIC distributions of the 31 azithromycin-resistant Salmonella (test group) and 14 susceptible ones (control group), and in subgroups possessing different azithromycin resistance determinant profiles. For isolates in the test group, MICs ranged from 32 to 1,024 μg/mL with MIC50 and MIC90 both at 128 µg/mL. Control group isolates had much lower MICs with MIC50 and MIC90 at 4 and 16 µg/mL, respectively. This translates to up to 256-fold MIC increases between azithromycin-susceptible and resistant ones.

TABLE 2.

Azithromycin MIC distributions among 45 Salmonella isolates from U.S. food animals at slaughter and processing and retail meats

| Group | Azithromycin resistance determinant | Serovar (no. of isolates) | No. of isolates with MIC (μg/mL) of a | MIC50 | MIC90 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | 1,024 | |||||

| Test | All (n = 31) | See below | 2 | 7 | 20 | 1 | 1 | 128 | 128 | ||||

| mph(A) (n = 18) | Newport (11), Schwarzengrund (2), Agona (1), I 4,[5],12:i:- (1), Mbandaka (1), Ohio (1), Typhimurium (1) | 1 | 17 | ||||||||||

| mph(E)-msr(E) (n = 6) | I 4,[5],12:i:- (6) | 4 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| erm(42) (n = 3) | Anatum (1), Meleagridis (1), Senftenberg (1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| acrB_R717L (n = 2) | Bredeney (1), Derby (1) | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| mph(A)-mph(E)-msr(E) (n = 1) | I 4,[5],12:i:- (1) | 1 | |||||||||||

| mph(G)-mef(C)-mph(E)-msr(E) (n = 1) | Agona (1) | 1 | |||||||||||

| Control | All (n = 14) | See below | 10 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 16 | ||||||

| None (n = 11) | Newport (4), Kentucky (2), I 4,[5],12:i:- (1), Infantis (1), Johannesburg (1), Reading (1), Typhimurium (1) | 8 | 3 | ||||||||||

| ere(A) b (n = 1) | I 4,[5],12:i:- (1) | 1 | |||||||||||

| mef(B) (n = 1) | Johannesburg (1) | 1 | |||||||||||

| mph(A) b (n = 1) | Typhimurium (1) | 1 | |||||||||||

None of the isolates had MICs from <0.125 to 2 mg/mL or >1,024 mg/mL. MIC50 and MIC90 values were not calculated for subgroups with different azithromycin resistance determinants due to low numbers of isolates.

These genes were either truncated or lacking the promoter region.

Six azithromycin resistance determinant profiles were identified, namely, mph(A) alone (n = 18), mph(E)-msr(E) (n = 6), erm(42) (n = 3), acrB_R717L (n = 2), mph(A)-mph(E)-msr(E) (n = 1), and mph(G)-mef(C)-mph(E)-msr(E) (n = 1). The mph(A), mph(E), and mph(G) genes code for macrolide 2′-phosphotransferases and erm(42) encodes 23S rRNA methyltransferase, whereas others are efflux pump related: mef(C) in the MFS family, msr(E) in the ABC family, and acrB (R717L mutation) in the RND family (9, 14). The highest azithromycin MIC (1,024 µg/mL) was observed in a Salmonella Agona isolate, 18IA01PC08-S2 [Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM) N18S0017], with the four-gene combination, whereas most mph(A)-containing isolates had a high MIC of 128 µg/mL (Table 2).

Three Salmonella controls harbored ere(A), mef(B), or mph(A) but were susceptible to azithromycin. Genomic analysis showed that the ere(A) gene in S. I 4,[5],12:i:- isolate 20MO07PC10-S1 (CVM N20S0154) was truncated (missing the first 62 amino acids), whereas the promoter region of mph(A) in S. Typhimurium isolate Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS)12032448 was also truncated by 24 bp. Both the mef(B) gene and its promoter in S. Johannesburg isolate 19MN02PC03 (CVM N19S0223) remained intact. Eleven other Salmonella controls were initially selected based on their phenotypic resistance to azithromycin or carrying potential macrolide resistance genes. AST and WGS performed at CVM showed they differed from the original designations. This was due to the loss of plasmids containing mph(A) or ere(A), or AST test variations for borderline isolates (azithromycin MICs around 16 µg/mL). For three isolates in the latter group, no mutations in the 23S rRNA gene were found.

Co-resistance to ceftriaxone and/or with decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin

As shown in Table 1, among the 31 azithromycin-resistant Salmonella isolates, 4 (1 S. Agona, 1 S. Mbandaka, and 2 S. I 4,[5],12:i:-) were co-resistant to ceftriaxone (MIC ≥4 µg/mL) and 16 (1 S. Bredeney, 4 S. I 4,[5],12:i:-, 10 S. Newport, and 1 S. Ohio) with decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin (MIC ≥0.125 µg/mL). One S. I 4,[5],12:i:- isolate FSIS11809860 was resistant to both azithromycin (MIC = 64 µg/mL) and ceftriaxone (MIC = 16 µg/mL) and also with decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin (MIC = 1 µg/mL).

The bla CMY-2 gene (three on IncC plasmids and one on a IncP6 plasmid) accounted for ceftriaxone resistance among the four isolates, whereas various qnr genes (qnrA1, qnrB6, and qnrB19), carried on diverse plasmid replicon types [Col440I/Col(pHAD28), IncC, IncFIB(K), IncHI2/IncHI2A, IncHI1B(R27)/IncHI1A/IncFIA(HI1), IncR, and IncY], were identified among 15 out of 16 isolates with decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin. The single isolate without qnr genes, S. I 4,[5],12:i:- FSIS11922707, possessed a chromosomal mutation (gyrA_D87N). Another isolate, S. Bredeney FSIS1702037, harbored both qnrB [on a Col440I/Col(pHAD28) helper plasmid] and a chromosomal mutation, gyrA_D87G, with the highest ciprofloxacin MIC of 4 µg/mL. This isolate also carried acrB_R717L mutation which accounted for its azithromycin resistance phenotype (64 µg/mL).

Azithromycin-resistant plasmids

All azithromycin resistance determinants were mapped to plasmids except for the acrB_R717L mutation in two isolates. The 29 closed plasmids belonged to various incompatibility groups (IncR, n = 11; IncC, n = 3; IncHI2/IncHI2A, n = 3; IncQ1, n = 3; others, n = 9), with 8 containing 2 or more replicon types (Table 3). The sizes ranged from 10,966 bp for an IncQ1 plasmid to 326,166 bp for an IncHI1B(pNDM-CIT)/IncHI1A(NDM-CIT) plasmid. All were MDR (resistant to ≥3 drug classes) except for three IncQ1 plasmids carrying erm(42) only and one IncP6 plasmid harboring mph(E)-msr(E). All but six plasmids contained the biocide resistance gene qacEdelta1 (one to three copies), and one also carried qacG2. Twelve plasmids contained heavy metal resistance genes, with as many as 18 genes resistant to four heavy metals in one isolate.

TABLE 3.

Azithromycin-resistant Salmonella plasmids (n = 29) from U.S. food animals at slaughter and processing and retail meats

| Azithromycin resistance gene |

Host serovar | Plasmid | Replicon type | Size | Antimicrobial, biocide, and heavy metal resistance genes (order of appearance on plasmid) a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| erm(42) | Anatum | pF18S049 | IncQ1 | 12,060 | erm(42) |

| Meleagridis | pFSIS1607675 | IncQ1 | 10,966 | erm(42) | |

| Senftenberg | pFSIS11813680-1 | IncQ1 | 10,967 | erm(42) | |

| mph(A) | Agona | pFSIS21821150 | IncHI2 | 273,370 | terW, terZ, terD , aph(6)-Id, aph(3'')-Ib, bla TEM-1, aph(3′)-Ia, aph(6)-Id, aph(3″)-Ib, tet(B), mph(A), sul1, qacEdelta1 , aac(3)-VIa, aadA1, silE , silS, silR, silC, silF, silB, silA, silP, pcoA, pcoB, pcoC, pcoD, pcoR, pcoS, pcoE |

| I 4,[5],12:i:- | pFSIS12035116-1 | IncHI2A/IncN/IncHI2 | 244,678 | terW, terZ, terD , aph(3')-Ia, floR, sul3, lnu(F), aadA22, mph(A), arr, dfrA14 | |

| Mbandaka | pFSIS11814474-1 | IncC | 163,603 | dfrA12, aadA2, qacEdelta1 , sul1, mph(A), aph(3')-Ia, qacG2 , merE , merD, merB, merA, merP, merT, merR , floR, tet(A), aph (6)-Id, aph(3'')-Ib, sul2, bla CMY-2 | |

| Newport | pFSIS12034723 | IncR | 53,263 | mph(A), sul1, qacEdelta1 , aadA2, bla CARB-2, qnrA1, sul1, qacEdelta1 , aadA2, bla CARB-2, qnrA1, sul1, qacEdelta1 , dfrA1, tet(A), floR | |

| pFSIS31903059-1 | IncR | 53,263 | mph(A), sul1, qacEdelta1, aadA2, bla CARB-2, qnrA1, sul1, qacEdelta1 , aadA2, bla CARB-2, qnrA1, sul1, qacEdelta1 , dfrA1, tet(A), floR | ||

| pFSIS11816184-1 | IncR | 46,951 | mph(A), sul1, qacEdelta1 , aadA2, bla CARB-2, qnrA1, sul1, qacEdelta1 , dfrA1, tet(A), floR | ||

| pFSIS12027867 | IncR | 46,951 | mph(A), sul1, qacEdelta1 , aadA2, bla CARB-2, qnrA1, sul1, qacEdelta1 , dfrA1, tet(A), floR | ||

| pFSIS32104969 | IncR | 46,951 | mph(A), sul1, qacEdelta1 , aadA2, bla CARB-2, qnrA1, sul1, qacEdelta1 , dfrA1, tet(A), floR | ||

| pFSIS32105981 | IncR | 46,951 | mph(A), sul1, qacEdelta1 , aadA2, bla CARB-2, qnrA1, sul1, qacEdelta1 , dfrA1, tet(A), floR | ||

| pFSIS12105828 | IncR | 46,950 | mph(A), sul1, qacEdelta1 , aadA2, bla CARB-2, qnrA1, sul1, qacEdelta1 , dfrA1, tet(A), floR | ||

| pFSIS12106020 | IncR | 46,950 | mph(A), sul1, qacEdelta1 , aadA2, bla CARB-2, qnrA1, sul1, qacEdelta1 , dfrA1, tet(A), floR | ||

| pFSIS12142912 | IncR | 46,950 | mph(A), sul1, qacEdelta1 , aadA2, bla CARB-2, qnrA1, sul1, qacEdelta1 , dfrA1, tet(A), floR | ||

| pFSIS22130757 | IncR | 46,950 | mph(A), sul1, qacEdelta1 , aadA2, bla CARB-2, qnrA1, sul1, qacEdelta1 , dfrA1, tet(A), floR | ||

| pFSIS11814458 | IncR | 40,637 | floR, tet(A), dfrA1, qacEdelta1 , sul1, mph(A) | ||

| Ohio | pFSIS11808786-1 | IncHI1B(R27)/IncHI1A/IncFIA(HI1) | 210,427 | tet(B), merR, merT, merP, merC , mph(A), sul1, qacEdelta1 , aadA2, dfrA12, aac (3)-IId, bla TEM-1 | |

| Schwarzengrund | pFSIS1609433-1 | IncFIA(HI1)/IncQ1/IncHI1B(R27)/IncHI1A | 222,461 | arsR, arsD , tet(B), merR, merT, merP, merC , dfrA12, aadA2, qacEdelta1 , sul1, mph(A), aac(3)-IId, bla TEM-1, sul2, aph(3'')-Ib, aph(6)-Id | |

| pFSIS1608447-1 | IncHI1B(R27)/IncHI1A/IncQ1 | 183,376 | tet(B), merR, merT, merP, merC , dfrA12, aadA2, qacEdelta1 , sul1, mph(A), aac(3)-IId, bla TEM-1, sul2, aph(3'')-Ib, aph(6)-Id | ||

| Typhimurium | pF18S031-1 | IncHI1B(pNDM-CIT)/IncHI1A(NDM-CIT) | 326,166 | catA1, merR, merT, merP, merC , aac(3)-Iva, aph(3')-Ia, aph(3')-Ia, aph(3')-Ia, aph(3')-Ia, mph(A), sul1, qacEdelta1 , aadA2, dfrA12, arsC , terD, terZ, terW | |

| mph(A)-mph(E)-msr(E) | I 4,[5],12:i:- | pFSIS21925668-1 | IncFIB(K) | 89,414 | sul1, qacEdelta1 , qnrB6, sul1, qacEdelta1 , aadA16, dfrA27, arr-3, aac(6′)-Ib-cr5, mph(A), mph(E), msr(E), bleO, aac(3)-IId, aph(3′)-Ia |

| mph(E)-msr(E) | I 4,[5],12:i:- | pFSIS11920112-1 | IncHI2/IncHI2A | 257,103 | sul1, qacEdelta1 , aph(3')-Ia, mcr-9.1, pcoS, arsC, aac(6′)-Ie/aph(2″)-Ia, terW, terZ, terD, merE, merD, merA, merT, merR, mph(E), msr(E), armA |

| pN17S1465-1 | IncHI2/IncHI2A | 249,408 | arsC, terW, terZ, terD, merE, merD, merA, merT, merR , mph(E), msr(E), armA, sul1, qacEdelta1, aph(3')-Ia, pcoS | ||

| pFSIS11922707-1 | IncHI2/IncHI2A | 247,657 | aac(6')-Ie/aph(2'')-Ia, arsC, pcoS , mcr-9.1, aac(6′)-Ie/aph(2″)-Ia, aph(3')-Ia, dfrA1, aadA5, qacEdelta1, sul1, armA, msr(E), mph(E), terD, terZ, terW | ||

| pFSIS11809860-1 | IncC | 175,970 | bla CMY-2, sul2, aph(3'')-Ib, aph(6)-Id, tet(A), floR, merR, merT, merP, merA, merB, merD, merE , sul1, qacEdelta1 , aadA2, aph(3')-Ia, mph(E), msr(E), armA, sul1, qacEdelta1 , aadA5, dfrA1 | ||

| pFSIS31901558-2 | IncY | 79,718 | bleO, mph(E), msr(E), armA | ||

| pF18S030-2 | IncP6 | 17,931 | mph(E), msr(E) | ||

|

mph(G)-mef(C)- mph(E)-msr(E) |

Agona | pN18S0017 | IncC | 180,114 | merR, merT, merP, merA, merB, merD, merE, bla CMY-2, aadA1, aac(3)-VIa, qacEdelta1 , sul1, sul2, mph(G), mef(C), mph(E), msr(E), tet(D) |

Biocide resistance genes are underlined, whereas heavy metal resistance genes are in bold.

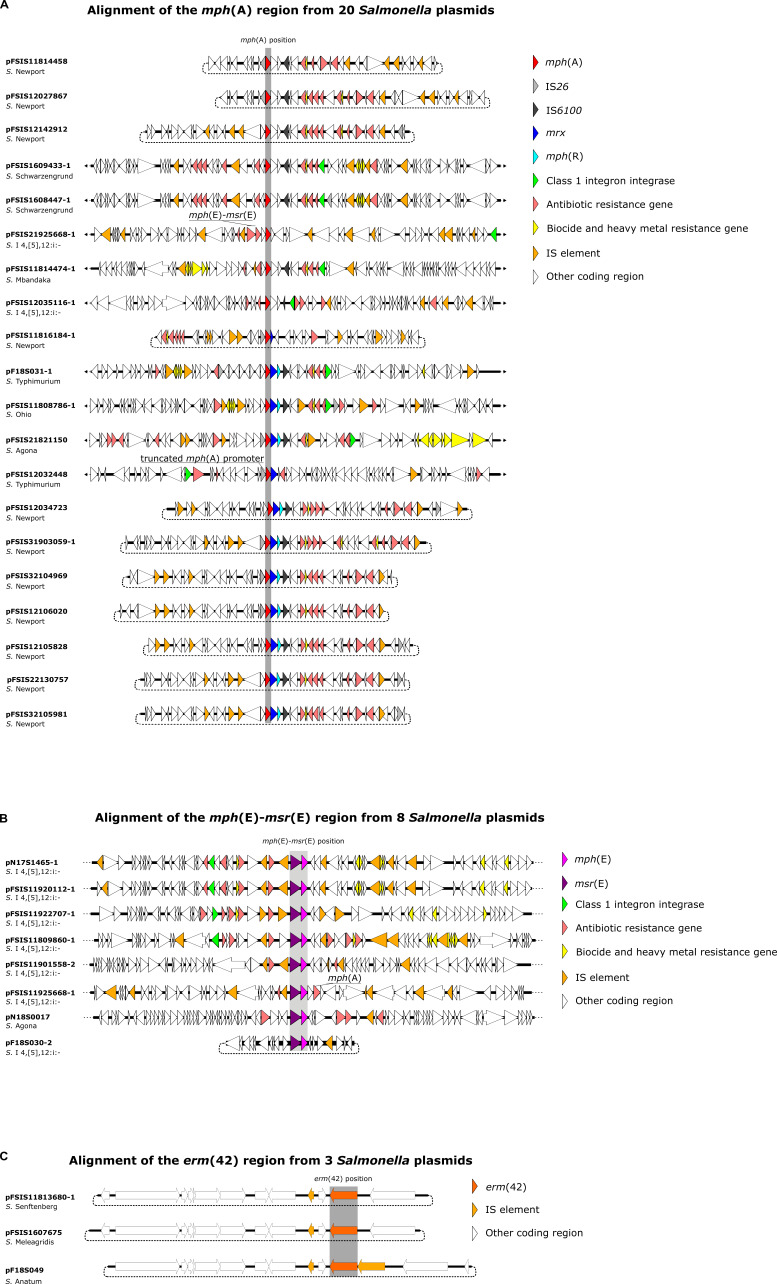

Figure 1A shows the genomic contexts among 20 mph(A)-containing plasmids from food animal sources, 11 of which were S. Newport IncR plasmids. Not surprisingly, mobile genetic elements such as class 1 integrons and insertion sequence (IS) elements were frequently observed. Nine out of the 20 mph(A)-containing plasmids carried the class 1 integron integrase gene intI1, 8 of which had a class 1 integron proximal to mph(A)-containing MDR, biocide, and heavy metal resistance genes, and various IS elements. A BLAST query of pFSIS12106020 (S. Newport, IncR) as a representative mph(A)-containing plasmid revealed multiple matches with Escherichia coli plasmids, including CP104124 and CP043753. Of the 4 plasmids that contained the complete mph(A) cluster [IS26-mph(A)-mrx-mphR-IS6100], 1 was from S. Agona (pFSIS21821150) and 3 others were from S. Newport (pFSIS12106020, pFSIS31903059-1, and pFSIS32104969).

Fig 1.

Genomic environments among 20 mph(A)-containing plasmids (A), 8 mph(E)-msr(E)-containing plasmids (B), and 3 erm(42)-containing plasmids (C).

Figure 1B shows the genetic environments for 8 plasmids harboring mph(E)-msr(E); all except 1 (pN18S0017; Agona) were from Salmonella serovar I 4,[5],12:i:-. Again, IS elements were frequently observed. In 4 plasmids (pN17S1465-1, pFSIS11920112-1, pFSIS11922707-1, and pFSIS11809860-1), mph(E)-msr(E) was located between IS15 and ISce29 elements, downstream from a class 1 integron. On pFSIS31901558-2, mph(E)-msr(E) was also located between IS15 and ISce29 elements but was not proximal to a class 1 integron. On pFSIS21925668-1, mph(A)-mph(E)-msr(E) was downstream of an IS15 element. The gene cassette mph(G)-mef(C)-mph(E)-msr(E) was upstream of ISVsa3 on pN18S0017, while mph(E)-msr(E) alone was upstream of ISVsa3 on pF18S030-2.

Similar genetic backgrounds were found among three erm(42)-containing plasmids from different Salmonella serovars recovered from food animals (Fig. 1C). All were small IncQ1 plasmids with the erm(42) gene upstream from an ISVa3 element. On pF18S049, this gene was immediately downstream of another IS element, ISVch6. The presence of these IS elements again suggests the mobility of this resistance gene.

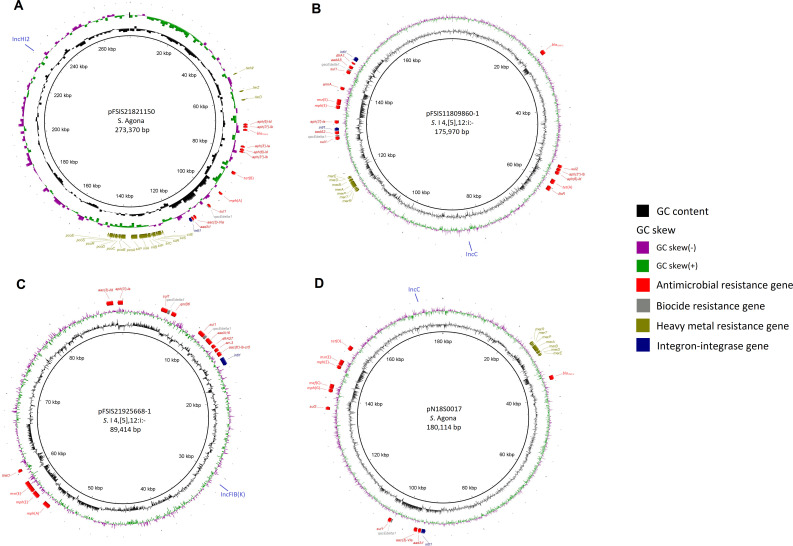

Figure 2A through D depicts circular structures of 4 plasmids harboring mph(A), mph(E)-msr(E), mph(A)-mph(E)-msr(E), and mph(G)-mef(C)-mph(E)-msr(E), respectively. These MDR plasmids carried genes conferring resistance to five to seven drug classes, including beta-lactams or quinolones, as well as biocides and heavy metals. Specifically, the S. Agona IncHI2 plasmid (pFSIS21821150, Fig. 2A) harbored AMR genes to five drug classes, including beta-lactams (bla TEM-1), qacEdelta1, eighteen heavy metal resistance genes, and intI. The S. I 4,[5],12:i:- IncFIB(K) plasmid (pFSIS21925668-1, Fig. 2C) contained AMR genes to seven drug classes, including fluoroquinolones [aac(6′)-Ib-cr5 and qnrB6], two copies of qacEdelta1, and intI. The 2 IncC plasmids, from S. I 4,[5],12:i:- (pFSIS11809860-1; Fig. 2B) and S. Agona (pN18S0017, Fig. 2D), both carried bla CMY-2 conferring resistance to third-generation cephalosporins, seven mercury resistance genes, and intI. Notably, the S. I 4,[5],12:i:- isolate FSIS11809860 also carried qnrB19 on a small plasmid (not shown), conferring decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin.

Fig 2.

Structures of 4 MDR plasmids harboring mph(A) [pFSIS21821150 (A)], mph(E)-msr(E) [pFSIS11809860-1 (B)], mph(A)-mph(E)-msr(E) [pFSIS21925668-1 (C)], and mph(G)-mef(C)-mph(E)-msr(E) [pN18S0017 (D)], respectively.

Emerging MDR S. Newport and S. I 4,[5],12:i:- clones of cattle and swine origins, respectively

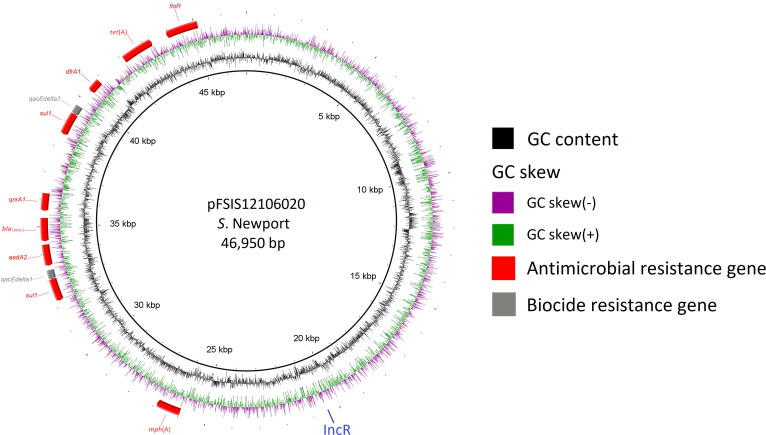

Of the 11 azithromycin-resistant S. Newport isolates, 10 were from cattle and 1 from sheep. Ten harbored MDR IncR plasmids (a representative one pFSIS12106020 shown in Fig. 3) that carried AMR genes for seven drug classes, conferring resistance to aminoglycosides (streptomycin), beta-lactams (ampicillin), folate pathway inhibitors (sulfisoxazole and trimethoprim), macrolides (azithromycin), phenicols (chloramphenicol), quinolones (decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin), and tetracyclines (tetracycline). These S. Newport isolates were found in a large NCBI single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) cluster PDS000007781.898 [n = 3,060; 94% clinical and 86.4% carrying mph(A)]. Clinical isolates were from the United States (n = 2,398), United Kingdom (n = 82), Mexico (n = 72), Canada (n = 15), and Chile (n = 5). Among 160 environmental isolates, 82 were from the United States; 72 were from Mexico; and 5 were from Chile. All but 14 U.S. isolates were from beef sources (82.9%). Isolates from Mexico were mainly from river/canal/pond (68.1%) and beef (27.8%), whereas all five Chilean isolates were from river samples. Except for 75 isolates recovered from 2016 to 2017, the remaining 2,985 isolates in this SNP cluster were from 2018 onward (15).

Fig 3.

The structure of a representative MDR IncR plasmid (pFSIS12106020) from the emerging Salmonella Newport clone of cattle/beef origin.

All 8 azithromycin-resistant S. I 4,[5],12:i:- isolates were of swine origin and carried MDR plasmids of six incompatibility groups [IncC and IncFIB(K) plasmids shown in Fig. 2B and C, respectively]. Five isolates were found in a large NCBI SNP cluster PDS000159488.2 (n = 13,464; 78% clinical and 1.9% carrying various azithromycin resistance genes). The majority (66.3%; 1,465 out of 2,211) of environmental isolates in the cluster were from swine/pork sources. Both clinical and environmental isolates spanned globally and temporally with the earliest isolation in 2001 (15).

DISCUSSION

Both World Health Organization and U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have classified macrolides as critically important antimicrobials for human medicine, along with third-generation cephalosporins and quinolones/fluoroquinolones (16, 17). All three drug classes are also considered critically important for veterinary medicine, though the widely used 15-membered ring macrolide azithromycin in humans is not approved for use in veterinary medicine (18). We report here the detection of Salmonella serovars in food animals and retail meats with co-resistance to ceftriaxone (a third-generation cephalosporin) or decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin (a fluoroquinolone) and provide insights into the underlying genetic mechanisms and genomic contexts on MDR plasmids. Further, the report highlights the emergence of an MDR S. Newport clone in food animals (mainly cattle, also sheep) in the United States with azithromycin resistance and decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin.

Though NARMS food animal and retail meat arms started routine azithromycin AST for Salmonella in 2011, occurrence of resistance was first detected in 2015 in an S. Derby isolate from ground turkey that had the acrB_R717L mutation (Table 1). During 2016, the S. I 4,[5],12:i:- clone with mph(E)-msr(E) was first detected, in addition to one erm(42)-containing Salmonella Meleagridis and two mph(A)-containing Salmonella Schwarzengrund isolates. In 2018, we detected the highly resistant S. Agona isolate harboring mph(G)-mef(C)-mph(E)-msr(E) and additional serovars (Agona, Mbandaka, Newport, and Ohio) containing mph(A). This study clearly documents the sequential detection of azithromycin resistance in Salmonella, including the S. Newport clone of cattle/beef origin in 2018. This trend can also be observed in the real-time display of NARMS monitoring data accessible through the NARMS Now dashboard online (19).

As noted earlier, NARMS monitoring of azithromycin resistance in nontyphoidal Salmonella was based on the CLSI’s breakpoint (≥32 µg/mL) for Salmonella Typhi. Our study (Table 2) and others (unpublished data) provided further evidence that Salmonella MICs to azithromycin do not differ among serovars. This breakpoint also agrees with the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing’s epidemiological cut-off value, which distinguishes Salmonella likely resistant to azithromycin from a wild-type susceptible population (20).

The predominance of mph(A) in our study isolates corroborates with numerous reports on azithromycin resistance mechanisms in Enterobacterales (9, 21 – 23). Four S. Newport isolates (FSIS21924576, FSIS12033266, FSIS12035959, and FSIS22106147) have lost the mph(A)-containing plasmids [searching up these isolates in NCBI pathogen detection isolates browser (15) still shows the presence of this gene as those reflect original testing results], suggesting plasmid instability/mobility. The finding of one mph(A)-harboring Salmonella Typhimurium isolate with a truncated promoter region is interesting, suggesting a new mechanism accounting for the lack of azithromycin resistance phenotype in Salmonella harboring mph(A). A recent in-depth characterization of two Salmonella conjugative plasmids showed the complete genetic makeup of the mph(A) cluster [IS26-mph(A)-mrx-mphR-IS6100], and the deletion of mphR restored azithromycin susceptibility (24). Four study isolates (three S. Newport and one S. Agona) had the complete mph(A) cluster and adjacent class 1 integron, suggesting the transferability of this gene cluster.

The mph(E) gene was co-located with msr(E) among all study isolates, supporting previous reports that they are part of a common operon in Gram-negative bacteria of different origins, including livestock (9, 25, 26). These two genes are often found on plasmids flanked by IS26 sequences associated with Tn1548::armA transposon, which facilitates the spread (25, 26). Agreeably, armA was found in five (out of eight) S. I 4,[5],12:i:- containing mph(E)-msr(E). Further, we detected one S. I 4,[5],12:i:- isolate from swine containing mph(E)-msr(E) with adjacent mph(A) on an IncFIB(K) plasmid and one S. Agona isolate harboring the mph(G)-mef(C)-mph(E)-msr(E) cluster on an IncC plasmid. The MIC to azithromycin in the latter isolate was eightfold higher than those harboring mph(A) alone. A recent study reported the first detection of Shiga toxin-producing E. coli in France carrying plasmid-borne mef(C)-mph(G) (27). Another report showed that mef(C)-mph(G) was carried on various vectors including plasmids and integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs) among marine and wastewater bacteria in Asian countries (28), and yet another study reported the occurrence of mef(C)-mph(G) in bacteria from the aquatic environment (29). The latter study also showed that mef(C) alone did not influence azithromycin susceptibility of E. coli, but mph(G) alone did, with more dramatic increases when both were introduced, suggesting a synergistic effect (29). To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first report on mph(G)-mef(C)-mph(E)-msr(E)-containing Salmonella with high-level azithromycin resistance.

The contribution of erm(42) to azithromycin resistance in Salmonella has been confirmed recently by direct cloning using an IncFIB/IncHI1B plasmid from Klebsiella pneumoniae (30). This gene has been detected earlier on a type 2 IncA/C2 plasmid from two Salmonella serovars (Ohio and Senftenberg) from swine in Australia (31). Two very recent studies in Taiwan reported an erm(42)-carrying ICE in 26.4% of MDR Salmonella Albany from human salmonellosis (32) as well as in Salmonella Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium IS26 composite transposons in the chromosomes (33). To our best knowledge, the genetic context of the three Salmonella serovars containing erm(42) reported in this study (on IncQ plasmids) is novel. Mutation in the RND-type transporter gene (acrB_R717L/Q), which has been reported mostly in S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi A, has been confirmed recently to confer azithromycin resistance in E. coli by cloning (34, 35). The first Arg717 substitution was predicted to have emerged around 2010 with travel-related R717Q mutant found in the United Kingdom (36). To our best knowledge, this is the first report of acrB_R717L in nontyphoidal Salmonella in the United States.

Whether, and to what degree, the wide use of other 15-membered ring macrolides such as gamithromycin and tulathromycin, and 14-membered or 16-membered ring macrolides in veterinary medicine (specifically food animals) selects for resistance or confers cross-resistance to macrolides used in human medicine, such as azithromycin, remains largely unknown. As Salmonella is intrinsically resistant to 14- and 16-membered ring macrolides, further cloning studies are needed to better evaluate the contribution of azithromycin resistance determinants such as those identified in this study to cross-resistance to those macrolides.

In our study, all azithromycin resistance genes were carried on plasmids, with 86.2% being MDR. This is not surprising owing to the significant role plasmids play in the evolution and acquisition of AMR genes in Salmonella (12). The finding of an S. I 4,[5],12:i:- isolate resistant to macrolides, third-generation cephalosporins, and with decreased susceptibility to fluoroquinolones, and an emerging MDR S. Newport clone of cattle origin (also sheep) resistant to macrolides with decreased susceptibility to fluoroquinolones is concerning. This clone has been involved in a 2018–2019 outbreak linked to beef in the United States and soft cheese obtained in Mexico (37). Notably, clinical isolates dominate this NCBI SNP cluster, whereas environmental isolates are mainly from water sources. We acknowledge that this SNP analysis was limited as it was solely based on publicly available data at NCBI. To contain the evolution and spread of azithromycin resistance in Salmonella, a One Health approach focused on monitoring and infection control, and a strong commitment to better understand the drivers of azithromycin resistance in Salmonella associated with food animal sources is warranted.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Azithromycin-resistant Salmonella isolates and controls

We examined NARMS food animal and retail meat culture collections (approximately 34,200 and 6,500 Salmonella isolates, respectively) between 2011 and 2021 for potential azithromycin-resistant Salmonella isolates. For the food animal sources, collected during slaughter and processing, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s FSIS and Agriculture Research Service tested cecal and lymph node samples (not destined for food) and product samples [regulatory/hazard analysis and critical control point (HACCP) program] from chickens, turkeys, cattle, swine, sheep, lamb, and goat. For the retail meat arm, U.S. FDA’s CVM, in partnership with state and local public health and agricultural departments and universities, tested retail raw meat samples from chicken, turkey, beef, and pork collected from grocery stores (10). AST was conducted using broth microdilution with NARMS Gram-negative plates (CMV2AGNF, from 2011 to 2013; CMV3AGNF, 2014–2015; CMV4AGNF, 2016–2019; and CMV5AGNF, 2020–2021) on the Sensititre Complete Automated AST System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), following the manufacturer’s instructions and CLSI guidelines (38). Breakpoints established by CLSI were adopted for MIC interpretation wherever available (3). For azithromycin, a resistant breakpoint of ≥32 µg/mL (CLSI breakpoint for S. Typhi) was used. Thirty-one azithromycin-resistant Salmonella and 14 susceptible controls were selected based on initial phenotypic and genotypic data (Table 1).

Agar dilution

Besides the broth dilution mentioned above, AST against an expanded range of azithromycin concentrations (0.125–1,024 µg/mL) for all 45 Salmonella isolates was performed by agar dilution following CLSI guidelines (38). Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212, Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 were used as quality control organisms, with QC ranges from CLSI where available (3, 39). MIC differences between azithromycin-resistant isolates (n = 31) and susceptible controls (n = 14) were compared, including fold changes, MIC50, and MIC90.

Short-read and long-read WGS

Short-read WGS was performed at NARMS partner labs and CVM following manufacturers’ instructions. The procedure used at CVM has been described previously (40). Briefly, genomic DNA was extracted using the QIAamp 96 DNA QIAcube HT kit in the automated QIAcube HT instrument (QIAGEN, Germantown, MD). Libraries were prepared with the Nextera XT DNA library preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) in the automated Sciclone G3 liquid handling workstation (PerkinElmer, Santa Clara, CA). Sequencing was performed on the MiSeq platform using the MiSeq reagent kit v3 chemistry with the 600-cycle option (Illumina). Raw reads were de novo assembled using the CLC genomics workbench 10 (QIAGEN).

Long-read sequencing was also performed at CVM as described previously (41) with slight modifications. Briefly, genomic DNA libraries with an average insert size of 10 kb or larger were prepared using the SMRTbell template prep kit 1.0 (PacBio, Menlo Park, CA). Sequencing was performed on the Sequel platform with the Sequel sequencing kit 3.0, and reads were assembled using the microbial assembly pipeline in SMRT link v11.0 (PacBio).

Bioinformatic analysis and data visualization

Salmonella serovars were determined by SeqSero2 (42), whereas genetic determinants for AMR, biocide resistance, and heavy metal resistance were identified with AMRFinderPlus v3.10 (14). Plasmid replicon typing was conducted using PlasmidFinder 2.1 (43), and IS elements flanking the resistance genes were located using ISfinder (44). MLST was performed with MLST 2.0 (45).

Alignments of three Salmonella isolates possessing ere(A), mef(B), and mph(A) with reference E. coli genes (GenBank accession no. NG_047765.1, NG_047978.1, and NG_047985.1, respectively) were performed with BLAST (46). Similarly, three Salmonella isolates with 16-µg/mL azithromycin MIC were examined for 23S rRNA gene mutations against a reference E. coli genome (GenBank accession no. NC_004431.1).

For data visualization, alignments of AMR gene-encoding regions were performed using Easyfig v2.2.2 (47). Circular structures of select azithromycin-resistant plasmids were drawn with BLAST ring image generator (48). The clustering of azithromycin-resistant Salmonella isolates to clinical and environmental Salmonella isolates deposited at NCBI was observed using the NCBI pathogen detection isolates browser (15).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Gordon Martin for laboratory assistance with whole-genome sequencing and Amy Merrill for providing National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System isolate data. We are grateful to Glenn Tillman and Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) laboratory staff for contributing FSIS Salmonella to this study.

Contributor Information

Beilei Ge, Email: beilei.ge@fda.hhs.gov.

Jasna Kovac, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania, USA .

DATA AVAILABILITY

MiSeq short-read and PacBio long-read WGS data were deposited to the NCBI short-read archive under BioProject accession no. PRJNA290865 and PRJNA292661, respectively.

REFERENCES

- 1. WHO . 2018. Salmonella (non-Typhoidal) fact sheet. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/salmonella-(non-typhoidal)

- 2. CDC . 2019. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2019. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/threats-report/2019-ar-threats-report-508.pdf

- 3. CLSI . 2023. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. In CLSI supplement M100, 33rd ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mutak S. 2007. Azalides from azithromycin to new azalide derivatives. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 60:85–122. doi: 10.1038/ja.2007.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hicks LA, Taylor TH, Hunkler RJ. 2013. U.S. outpatient antibiotic prescribing. N Engl J Med 368:1461–1462. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1212055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. CDC . 2023. CDC yellow book 2024: Health information for International travel. Available from: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/yellowbook-home

- 7. Committee on Infectious Diseases American Academy of Pediatrics; Kimberlin DW, Barnett ED, Lynfield R, Sawyer MH . 2021. Salmonella infections. Available from: https://publications.aap.org/redbook/book/347/Red-Book-2021-2024-Report-of-the-Committee-on

- 8. Sjölund-Karlsson M, Joyce K, Blickenstaff K, Ball T, Haro J, Medalla FM, Fedorka-Cray P, Zhao S, Crump JA, Whichard JM. 2011. Antimicrobial susceptibility to azithromycin among Salmonella enterica isolates from the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:3985–3989. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00590-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gomes C, Martínez-Puchol S, Palma N, Horna G, Ruiz-Roldán L, Pons MJ, Ruiz J. 2017. Macrolide resistance mechanisms in Enterobacteriaceae: Focus on azithromycin. Crit Rev Microbiol 43:1–30. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2015.1136261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. FDA . 2023. The National antimicrobial resistance monitoring system. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/national-antimicrobial-resistance-monitoring-system/about-narms

- 11. McDermott PF, Tyson GH, Kabera C, Chen Y, Li C, Folster JP, Ayers SL, Lam C, Tate HP, Zhao S. 2016. Whole-genome sequencing for detecting antimicrobial resistance in nontyphoidal Salmonella. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:5515–5520. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01030-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li C, Tyson GH, Hsu CH, Harrison L, Strain E, Tran TT, Tillman GE, Dessai U, McDermott PF, Zhao S. 2021. Long-read sequencing reveals evolution and acquisition of antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes in Salmonella enterica. Front Microbiol 12:777817. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.777817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhao S, Li C, Hsu CH, Tyson GH, Strain E, Tate H, Tran TT, Abbott J, McDermott PF. 2020. Comparative genomic analysis of 450 strains of Salmonella enterica isolated from diseased animals. Genes 11:1025. doi: 10.3390/genes11091025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. NCBI . 2023. Reference gene catalog. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pathogens/refgene

- 15. NCBI . 2023. Pathogen detection isolates Browser. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pathogens

- 16. WHO . 2019. Critically important antimicrobials for human medicine, 6th revision. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1217095/retrieve

- 17. FDA . 2023. GFI #152: Evaluating the safety of antimicrobial new animal drugs with regard to their Microbiological effects on bacteria of human health concern. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/cvm-gfi-152-evaluating-safety-antimicrobial-new-animal-drugs-regard-their-microbiological-effects

- 18. WOAH . 2021. OIE list of antimicrobial agents of veterinary importance. Available from: https://www.oie.int/app/uploads/2021/06/a-oie-list-antimicrobials-june2021.pdf

- 19. FDA . 2023. NARMS now: Integrated data. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/national-antimicrobial-resistance-monitoring-system/narms-now-integrated-data

- 20. EUCAST . 2023. Antimicrobial wild type distributions of microorganisms. Available from: https://mic.eucast.org

- 21. Dinos GP. 2017. The macrolide antibiotic renaissance. Br J Pharmacol 174:2967–2983. doi: 10.1111/bph.13936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gomes C, Ruiz-Roldán L, Mateu J, Ochoa TJ, Ruiz J. 2019. Azithromycin resistance levels and mechanisms in Escherichia coli. Sci Rep 9:6089. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42423-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Faccone D, Lucero C, Albornoz E, Petroni A, Ceriana P, Campos J, Viñas MR, Francis G, AZM-R-Group, Melano RG, Corso A. 2018. Emergence of azithromycin resistance mediated by the mph(A) gene in Salmonella Typhimurium clinical isolates in Latin America. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 13:237–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2018.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xie M, Chen K, Chan E-C, Chen S. 2022. Identification and genetic characterization of two conjugative plasmids that confer azithromycin resistance in Salmonella. Emerg Microbes Infect 11:1049–1057. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2022.2058420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dolejska M, Villa L, Poirel L, Nordmann P, Carattoli A. 2013. Complete sequencing of an IncHI1 plasmid encoding the carbapenemase NDM-1, the ArmA 16S RNA methylase and a resistance-nodulation-cell division/multidrug efflux pump. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:34–39. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Du XD, Li DX, Hu GZ, Wang Y, Shang YH, Wu CM, Liu HB, Li XS. 2012. Tn1548-associated armA is co-located with qnrB2, aac(6')-Ib-Cr and blaCTX-M-3 on an IncFII plasmid in a Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B strain isolated from chickens in China. J Antimicrob Chemother 67:246–248. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bizot E, Cointe A, Bidet P, Mariani-Kurkdjian P, Hobson CA, Courroux C, Liguori S, Bridier-Nahmias A, Magnan M, Merimèche M, Caméléna F, Berçot B, Weill F-X, Lefèvre S, Bonacorsi S, Birgy A. 2022. Azithromycin resistance in Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in France between 2004 and 2020 and detection of mef(C)-mph(G) genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 66:e0194921. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01949-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sugimoto Y, Suzuki S, Nonaka L, Boonla C, Sukpanyatham N, Chou HY, Wu JH. 2017. The novel mef(C)-mph(G) macrolide resistance genes are conveyed in the environment on various vectors. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 10:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2017.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nonaka L, Maruyama F, Suzuki S, Masuda M. 2015. Novel macrolide-resistance genes, mef(C) and mph(G), carried by plasmids from Vibrio and Photobacterium isolated from sediment and seawater of a coastal aquaculture site. Lett Appl Microbiol 61:1–6. doi: 10.1111/lam.12414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu X, Yang X, Ye L, Chan E-C, Chen S. 2022. Genetic characterization of a conjugative plasmid that encodes azithromycin resistance in Enterobacteriaceae. Microbiol Spectr 10:e0078822. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.00788-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Harmer CJ, Holt KE, Hall RM. 2015. A type 2 A/C2 plasmid carrying the aacC4 apramycin resistance gene and the erm(42) erythromycin resistance gene recovered from two Salmonella enterica serovars. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:1021–1025. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hong Y-P, Chen Y-T, Wang Y-W, Chen B-H, Teng R-H, Chen Y-S, Chiou C-S. 2023. Integrative and conjugative element-mediated azithromycin resistance in multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Albany. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 65:e02634-20. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02634-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chiou C-S, Hong Y-P, Wang Y-W, Chen B-H, Teng R-H, Song H-Y, Liao Y-S. 2023. Antimicrobial resistance and mechanisms of azithromycin resistance in nontyphoidal Salmonella isolates in Taiwan, 2017 to 2018. Microbiol Spectr 11:e0336422. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.03364-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hooda Y, Sajib MSI, Rahman H, Luby SP, Bondy-Denomy J, Santosham M, Andrews JR, Saha SK, Saha S. 2019. Molecular mechanism of azithromycin resistance among Typhoidal salmonella strains in Bangladesh identified through passive pediatric surveillance. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 13:e0007868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zwama M, Nishino K. 2022. Proximal binding pocket Arg717 substitutions in Escherichia coli AcrB cause clinically relevant divergencies in resistance profiles. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 66:e0239221. doi: 10.1128/aac.02392-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sajib MSI, Tanmoy AM, Hooda Y, Rahman H, Andrews JR, Garrett DO, Endtz HP, Saha SK, Saha S. 2021. Tracking the emergence of azithromycin resistance in multiple genotypes of typhoidal Salmonella. mBio 12:e03481-20. doi: 10.1128/mBio.03481-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Plumb ID, Schwensohn CA, Gieraltowski L, Tecle S, Schneider ZD, Freiman J, Cote A, Noveroske D, Kolsin J, Brandenburg J, Chen JC, Tagg KA, White PB, Shah HJ, Francois Watkins LK, Wise ME, Friedman CR. 2019. Outbreak of Salmonella Newport infections with decreased susceptibility to azithromycin linked to beef obtained in the United States and soft cheese obtained in Mexico - United States, 2018-2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 68:713–717. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6833a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. CLSI . 2018. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. In CLSI standard M07, 11th ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 39. CLSI . 2018. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk and dilution susceptibility tests for bacteria isolated from animals. In CLSI standard VET08, 4th ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Domesle KJ, Young SR, Ge B. 2021. Rapid screening for Salmonella in raw pet food by loop-mediated isothermal amplification. J Food Prot 84:399–407. doi: 10.4315/JFP-20-365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tate H, Li C, Nyirabahizi E, Tyson GH, Zhao S, Rice-Trujillo C, Jones SB, Ayers S, M’ikanatha NM, Hanna S, Ruesch L, Cavanaugh ME, Laksanalamai P, Mingle L, Matzinger SR, McDermott PF. 2021. A national antimicrobial resistance monitoring system survey of antimicrobial-resistant foodborne bacteria isolated from retail veal in the United States. J Food Prot 84:1749–1759. doi: 10.4315/JFP-21-005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhang S, den Bakker HC, Li S, Chen J, Dinsmore BA, Lane C, Lauer AC, Fields PI, Deng X. 2019. Seqsero2: Rapid and improved salmonella Serotype determination using whole-genome sequencing data. Appl Environ Microbiol 85:e01746-19. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01746-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Carattoli A, Hasman H. 2020. PlasmidFinder and in silico pMLST: Identification and typing of plasmid replicons in whole-genome sequencing (WGS). Methods Mol Biol 2075:285–294. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9877-7_20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Siguier P, Perochon J, Lestrade L, Mahillon J, Chandler M. 2006. ISfinder: The reference centre for bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 34:D32–D36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Larsen MV, Cosentino S, Rasmussen S, Friis C, Hasman H, Marvig RL, Jelsbak L, Sicheritz-Pontén T, Ussery DW, Aarestrup FM, Lund O. 2012. Multilocus sequence typing of total-genome-sequenced bacteria. J Clin Microbiol 50:1355–1361. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06094-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. NCBI . 2023. Basic local alignment search tool. Available from: https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi

- 47. Sullivan MJ, Petty NK, Beatson SA. 2011. Easyfig: A genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics 27:1009–1010. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Alikhan NF, Petty NK, Ben Zakour NL, Beatson SA. 2011. BLAST ring image generator (BRIG): Simple prokaryote genome comparisons. BMC Genomics 12:402. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

MiSeq short-read and PacBio long-read WGS data were deposited to the NCBI short-read archive under BioProject accession no. PRJNA290865 and PRJNA292661, respectively.