Abstract

Background:

Stigma among mental disorders like anxiety has been identified as an important barrier in help-seeking by national policymakers. Anxiety disorders are quite common among college students, and their severity and prevalence are growing. This study aimed to assess help-seeking behavior (HSB) towards anxiety among undergraduate students of Kathmandu University (KU).

Methodology:

A web-based cross-sectional study was conducted among 422 undergraduate students. General Help-Seeking Questionnaire (GHSQ) tool was used to assess HSB. Frequencies, percentages, mean, and Standard Deviation were calculated to assess the characteristics of the participants. Factors associated with HSB were examined using Chi-Square test. Pearson correlation was determined to find out the association between professional and informal sources for seeking help. All the tests were carried out at the statistically significant level at a P-value of 0.05.

Results:

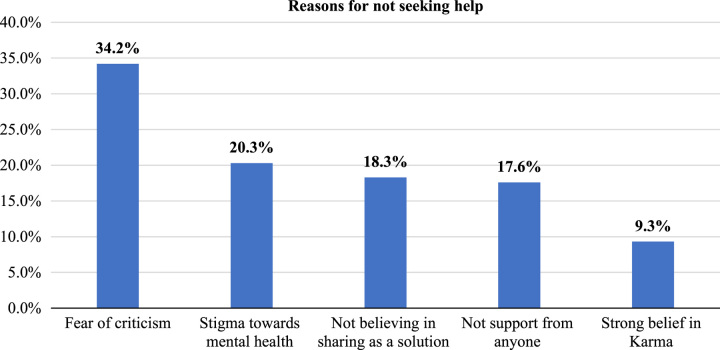

The mean (±SD) age was 20.3±1.1 years in this study. This study demonstrated that 36.5 and 17.5% of the participants were extremely likely to seek help from parents and psychiatrists towards anxiety, respectively. Sex (OR=1.5, 95% CI: 1.0–1.3) was significantly associated with parents, education was significantly associated with parents (OR=0.4, 95% CI: 0.2–0.6), and friends (OR=0.5, 95% CI: 0.3–0.9), meanwhile, ethnicity (OR=0.6, 95% CI: 0.4–0.9), and residence (OR=0.5, 95% CI: 0.3–0.8) were significantly associated with psychiatrists and psychologists for help-seeking behavior, respectively. Fear of criticism (34.1%) and stigma (20.3%) were the main reasons for not seeking help among the participants. The maximum number of participants (41.5%) preferred to seek help immediately if they ever experienced anxiety. This study showed professional and informal sources were positively correlated with anxiety (rpi=0.3) at a P-value <0.05.

Conclusion:

This study showed that students preferred to seek help from informal sources rather than professional sources. In addition, there is still stigma and fear among students regarding mental health. This study suggests that there is a need to have psychosocial intervention at colleges and educational institutions in order to promote professional help-seeking for any mental disorders including anxiety.

Keywords: anxiety, help-seeking behavior, informal sources, Nepal, professional sources, undergraduate students

Introduction

Highlights

This study is among the first studies to determine help-seeking behavior towards anxiety among students in Nepal. Thus, the findings will aid in providing evidence for the prevention and management of mental disorders among adults and students.

Anxiety disorders are common, and their severity and prevalence are growing among students.

This study demonstrated that 36.5 and 17.5% of the participants were extremely likely to seek help from parents and psychiatrists towards anxiety, respectively. Sex was significantly associated with parents. Fear of criticism and stigma were the main reasons for not seeking help.

Many previous studies recommended exploring the relationship between professional and informal sources. This study determined the relationship between professional and informal sources for help-seeking for mental disorders.

Our study concluded still there is prevalence of stigma and fear among students regarding help-seeking for mental health. This study suggests that there is a need to have psychosocial intervention at educational institutions to promote professional help-seeking for mental issues.

American Psychological Association (APA) define ‘anxiety as characterized by feelings of tension, worried thoughts, and physical changes like sweating, trembling, dizziness, or a rapid heartbeat’1. Anxiety has been on the rise among college students, accompanied by an increase in suicidal ideation2.

Globally, anxiety disorders pose a threat to society due to an immense economic burden3. Each adult develops mental illness about 29.2% on average in their lifetime, including anxiety disorders (4.3–8.7%)4. Despite the presence of anxiety signs/symptoms, students are reluctant to seek help from health professionals such as psychologists, counselors, psychiatrists, doctors, and nurses5. Young adults have been facing challenges in seeking help for mental health due to deeply ingrained beliefs and attitudes, especially in countries like Nepal6.

Students are suffering from anxiety due to personal and family problems, school-related stress, health concerns, peer pressure, and relationship dynamics that significantly impact the well-being and academic performance of the students7. Many adults who suffer from mental illnesses, including anxiety, do not seek out professional medical assistance. However, early intervention for anxiety disorders can significantly lower the burden of mental illnesses, save financial costs, prevent relapses in the future, enhance social functioning, and enhance the quality of life for students8. Mentally ill patients are often blamed for bringing their illness in the society and seen as victims of unfortunate fate, religious, and moral transgression or even witchcraft9. This subsequently results in delay in seeking professional treatment9.

In Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) including Nepal, limited access to mental health treatment, high prevailing issues of stigma, and financial hardship pose a significant risk to the mental health of students10. Furthermore, since the COVID-19 pandemic, student’s mental health issues have become more serious11.

Several studies indicated that 5.2% of students across the country are affected by mental health issues and have been increasing in the prevalence of depression (24.3–56.5%), and anxiety (46.9–55.6%)12–19. Notably, a higher prevalence among students who planned suicide were found among those experiencing anxiety and depression15.

Students are the vulnerable group for the study of help-seeking due to their high prevalence of anxiety. Several studies suggested there is a need to focus on reducing the stigma surrounding suicide to influence help-seeking attitudes among the students at risk20,21. In addition, help-seeking behavior (HSB) toward anxiety and its associated factors are pivotal in designing effective community-based mental health interventions9. To reduce the barriers to help-seeking for any mental health problems, it is vital to understand the dynamic relationship of factors predicting HSB among students. To the best of our knowledge, limited studies have been conducted on HSB towards anxiety in Nepal. Our study aimed to assess help-seeking behavior towards anxiety among undergraduate students of Kathmandu University.

Methodology

Study setting

A web cross-sectional study was conducted at Kathmandu University School of Sciences (KUSoS) of Kavrepalanchok district, Nepal. Kathmandu University (KU) is one of the largest autonomous universities in Nepal. It is a self-funding public institution established by the act of parliament in 1991. It is an institution of higher learning dedicated to maintaining the standard of academic excellence in various classical and professional disciplines22. It provides more than 200 academic programs in the undergraduate, graduate, and postgraduate levels. KU comprises seven schools and colleges: School of Arts, School of Management, School of Law, School of Education, School of Medical Science, School of Engineering, and School of Science.

Study population

The students Pursuing an undergraduate degree from various schools and colleges of Kathmandu University were employed in this study. All the undergraduate students above 18 years were eligible for inclusion in this study.

Study design and sample

A cross-sectional study was performed between July and August of 2021. Identification numbers and additional information of undergraduate students were obtained from the Dean’s office and the information office of Kathmandu University. Then, convenience sampling technique was employed to select participants. Those participants who came in contact with the investigator were recruited for data collection in this study. Participants were contacted via email, Facebook, WhatsApp, and phone call.

Single population proportion formula (n=Z2pq/d2) was used to calculate the sample size for this study23. Estimating 50% proportion of help-seeking, 95% CI, and 5% margin error, sample size of N=384 was calculated. After the addition of 10% nonresponse rate, the final sample size was 422 for this study.

Measures

HSB was determined through the General Help-Seeking Questionnaire (GHSQ). It has a seven-point Likert scale response ranging from extremely unlikely to extremely likely responses5,24. The study tool was pretested among the 10% of sample size to check the validity and reliability, and obtained Cronbach’s alpha score of 0.75, which is comparable to the GHSQ of 0.85 Cronbach’s alpha score9.

The questionnaire was divided into three sections. The first section consisted of social and demographical characteristics of the study participants. It includes age (in completed years), sex (male/female), ethnicity (Brahmin/Chhetri, Janajati, Madhesi, and others), religion (Hindu, Buddhist, and others), education (engineering, medical science, business administration, and management), bachelor level (first year, second year, third year, and fourth year), family type (nuclear and joint/extended), and residence (alone, with friend/s, and with parent/s).

The second section consisted of questions about help-seeking sources, that is professional and informal sources. In professional sources, it included psychologists, doctors, nurses, psychiatrists, and traditional healers. Meanwhile, third section comprised reasons for not seeking help, duration for help-seeking, and previous experiences while seeking help towards anxiety.

HSB was determined assigning scoring ‘7’ for extreme likely, ‘6’ for little likely, ‘5’ for likely, ‘4’ for neutral, ‘3’ for unlikely, ‘2’ for little unlikely and ‘1’ for extremely unlikely. Higher score indicating high propensity in choosing sources for help-seeking towards anxiety. Participants’ score ‘5’ and above were categorized into high propensity while score below ‘5’ as low propensity in this study25.

This work has been reported in line with the strengthening the reporting of cohort, cross-sectional and case–control studies in surgery (STROCSS) criteria26.

Data collection

Online Google Form was used to collect the data from the participants. Questionnaire was administered to the participants through social media platforms (Gmail, Facebook, and WhatsApp) to collect the data. A single response from each participant was ensured via Google Forms setting by choosing ‘Limit to 1 response’.

Data management and analysis

Collected data were automatically recorded in Google Sheets. Then, data were systematically compiled, cleaned, filtered, checked, and edited in the Google Sheets before exporting to the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20 (IBM) for analysis. Frequencies, mean, SD, and percentages were calculated to describe the individual characterstics of the participants. Factors associated with the HSB towards anxiety of participants were examined using χ2tests. Pearson correlation was determined to find out the association between professional and informal preferences. All the tests were carried out at the statistically significant level at a P-value of 0.05.

Results

Social and demographical characteristics of the participants

A total of 422 participants were employed in this study. The mean (±SD) age of the participants was 20.3±1.1 years, ranging from 18 to 23 years. Almost equal proportion of males (52.1%) and females (47.9%) participated in this study. Most of the participants were Brahmin/Chhetri (59.5%) and Hindu (90.3%). Majority of the participants were from engineering background (50.5%) and studying in bachelor third year (39.3%). Most participants belonged to nuclear families (77.3%) and residing with their parents (53%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Individual characteristics of the study participants

| Characteristics | Number (n) (Percentage (%)) |

|---|---|

| Age (20.3±1.1 years) | |

| 18–20 years | 237 (56.2) |

| 21–23 years | 185 (43.8) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 202 (47.9) |

| Male | 220 (52.1) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Brahmin/Chhetri | 251 (59.5) |

| Janajati | 136 (32.2) |

| Madhesi | 28 (6.6) |

| Others | 7 (1.7) |

| Religion | |

| Hindu | 381 (90.3) |

| Buddhist | 24 (5.7) |

| Others | 17 (4.0) |

| Education | |

| Engineering | 213 (50.5) |

| Medical science | 129 (30.6) |

| Business administration and management | 66 (15.6) |

| Others | 14 (3.3) |

| Current year | |

| First year | 127 (30.1) |

| Second year | 118 (28.0) |

| Third year | 166 (39.3) |

| Fourth year | 11 (2.6) |

| Family type | |

| Nuclear | 326 (77.3) |

| Joint/Extended | 96 (22.7) |

| Residence | |

| Alone | 69 (16.4) |

| With friend/s | 129 (30.6) |

| With parent/s | 224 (53.0) |

HSB towards anxiety among the participants

This study indicated that participants were extremely likely to seek help from psychiatrists (17.5%) and psychologists (16.6%), and traditional healers (2.8%) as the professional preferences towards anxiety. While most of the participants (61.8%) were extremely unlikely to seek help from traditional healers in this study. This study found one-third of the participants were extremely likely seek help from their parents (36.5%), intimate partner (32.5%), and self-help (32.9%). Most of the participants were unlikely to seek help from friends (36.3%) and family members (24.4%) in this study. However, only few of the participants (1.7%) were likely to seek self-help towards anxiety (Table 2).

Table 2.

HSB towards anxiety among the study participants

| Characteristics | Extremely likely n (%) | Little likely n (%) | Likely n (%) | Neutral n (%) | Unlikely n (%) | Little unlikely n (%) | Extremely unlikely n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professional sources | |||||||

| Psychologist | 70 (16.6) | 22 (5.2) | 75 (17.8) | 36 (8.5) | 89 (21.1) | 34 (8.1) | 96 (22.7) |

| Doctor | 48 (11.4) | 32 (7.6) | 68 (16.1) | 39 (9.2) | 101 (23.9) | 41 (9.7) | 93 (22.1) |

| Psychiatrist | 74 (17.5) | 27 (6.4) | 70 (16.6) | 26 (6.2) | 60 (14.2) | 28 (6.6) | 137 (32.5) |

| Traditional healer | 12 (2.8) | 31 (7.3) | 59 (13.9) | 21 (4.9) | 25 (5.9) | 13 (3.4) | 261 (61.8) |

| Informal sources | |||||||

| Intimate partner | 137 (32.5) | 12 (2.8) | 38 (9.0) | 17 (4.0) | 100 (23.7) | 26 (6.2) | 92 (21.8) |

| Parents | 154 (36.5) | 20 (4.7) | 52 (12.3) | 33 (7.8) | 74 (17.5) | 46 (10.9) | 43 (10.3) |

| Friends | 68 (16.1) | 14 (3.3) | 45 (10.7) | 35 (8.3) | 153 (36.3) | 76 (18.0) | 31 (7.3) |

| Family member | 72 (17.1) | 24 (5.7) | 49 (11.6) | 56 (13.3) | 103 (24.4) | 60 (14.2) | 58 (13.7) |

| Self-help | 139 (32.9) | 8 (1.9) | 7 (1.7) | 10 (2.4) | 97 (22.0) | 59 (13.0) | 102 (24.1) |

Association between participants’ sex, family type, and education with HSB towards anxiety

Table 3 demonstrates sex was significantly associated with parents (OR=1.5, 95% CI: 1.0–1.3) and friends (OR=1.5, 95% CI: 1.0–2.4) for help-seeking in this study. While parents (OR=0.4, 95% CI: 0.2–0.6) and friends (OR=0.5, 95% CI: 0.3–0.9) were significantly associated with the education of the participants. Family type of the participants was only significantly associated with friends (OR=1.8, 95% CI: 1.0–3.1).

Table 3.

Association between participants’ sex, family type, and education with HSB towards anxiety

| Sources | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents | Friends | |||||||

| Characteristics | High propensity n (%) | Low propensity n (%) | P | OR, 95% CI | High propensity n (%) | Low propensity n (%) | P | OR, 95% CI |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 132 (60.0) | 88 (40.0) | 145 (65.9) | 75 (34.1) | ||||

| Female | 142 (70.3) | 60 (29.7) | 0.02 | 1.5 (1.0-1.3) | 152 (75.2) | 50 (24.8) | 0.03 | 1.5 (1.0-2.4) |

| Family type | ||||||||

| Nuclear | 215 (66.0) | 111 (34.0) | 221 (67.8) | 105 (32.2) | ||||

| Joint/extended | 58 (60.4) | 38 (39.6) | 0.41 | 0.8 (0.5-1.3) | 76 (79.2) | 20 (20.8) | 0.03 | 1.8 (1.0-3.1) |

| Education | ||||||||

| Medical | 101 (78.3) | 28 (21.7) | 100 (77.5) | 29 (22.5) | ||||

| Non-medical | 173 (59.0) | 120 (41.0) | 0.00 | 0.4 (0.2-0.6) | 197 (67.2) | 96 (32.8) | 0.03 | 0.5 (0.3-0.9) |

Association between participants’ residence and ethnicity with HSB towards anxiety

Table 4 shows that residence was significantly associated with psychologist (OR=0.5, 95% CI: 0.3–0.8). Meanwhile, ethnicity was significantly associated with psychiatrist (OR=0.6, 95% CI: 0.4–0.9) in this study.

Table 4.

Association between participants’ residence and ethnicity with HSB towards anxiety

| Sources | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychologist | Psychiatrist | |||||||

| Characteristics | High propensity n (%) | Low propensity n (%) | P | OR, 95% CI | High propensity n (%) | Low propensity n (%) | P | OR, 95% CI |

| Residence | ||||||||

| With parents | 117 (52.2) | 107 (47.8) | 95 (42.4) | 129 (57.6) | ||||

| Without parents | 76 (38.4) | 122 (61.6) | 0.004 | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | 67 (33.8) | 131 (66.2) | 0.07 | 0.6 (0.4–1.0) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Brahmin/Chettri | 120 (47.8) | 131 (52.2) | 107 (42.6) | 144 (57.4) | ||||

| Others | 73 (42.7) | 98 (57.3) | 0.3 | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | 55 (32.2) | 116 (67.8) | 0.03 | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) |

P-value statistically significantly at the level of 0.05

Association between participants’ age and religion with HSB towards anxiety

Table 5 illustrates that age (OR=1.9, 95% CI: 1.0–3.4) and religion (OR= 2.3, 95% CI: 1.0–5.2) of the participants were significantly associated with traditional healer.

Table 5.

Association between participants’ age and religion with HSB towards anxiety

| Source | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional healer | ||||

| Characteristics | High propensity n (%) | Low propensity n (%) | P | OR, 95% CI |

| Age | ||||

| 18–20 years | 21 (8.9) | 216 (91.1) | ||

| 21–13 years | 29 (15.7) | 156 (84.3) | 0.03 | 1.9 (1.0–3.4) |

| Religion | ||||

| Hindu | 41 (10.8) | 340 (89.2) | ||

| Others | 9 (22.0) | 32 (78.0) | 0.03 | 2.3 (1.0–5.2) |

All the variables are significantly associated at the level of P-value 0.05.

Duration for help-seeking

The majority of the participants (41.5%) reported that if they experience any signs or symptoms of anxiety in the future, they would prefer to wait at least one month. While 35.5% of the participants would prefer to sought help immediately if they ever experience anxiety in this study. Unfortunately, some of them would never seek help from others, even if they were to experience anxiety (9%) in the future (Table 6).

Table 6.

Duration for seeking help towards anxiety among the study participants

| Characteristics | Response |

|---|---|

| Duration for seeking help | n (%) |

| Immediately | 150 (35.5) |

| Wait for a month | 175 (41.5) |

| After 3 months | 30 (7.1) |

| After 6 months | 29 (6.9) |

| Would never ask for help | 38 (9.0) |

Reasons for not seeking help towards anxiety among the study participants

According to this study, most of the participants, that is 34.2% and 20.3% believed fear of criticism and social stigma were the main barriers to seeking help towards anxiety, respectively (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Reasons for not seeking help towards anxiety.

Previous help-seeking experiences towards anxiety

This study found that only 20.1% of the participants sought help when they had anxiousness. Among them, most sought help from doctors (37.6%), psychiatrists (29.4%) while 5.8% did not know the sources to get help at that time. Majority of them (44.7%) found the services was extremely helpful when they visited health professionals (Table 7).

Table 7.

Previous help-seeking experience towards anxiety among the study participants

| Characteristics | Response | Number (Percentage) |

|---|---|---|

| Did you seek help from anyone when you were anxious? | Yes | 85 (20.1) |

| No | 337 (79.9) | |

| Do you know which type of health professional (s) you have seen? (n=85) | ||

| Doctor | 32 (37.6) | |

| Psychiatrist | 25 (29.4) | |

| Psychologist/Counselor | 12 (14.3) | |

| Nurse | 11 (12.9) | |

| Do not know | 5 (5.8) | |

| How helpful was the visit to the health professionals? (n=85) | ||

| Extremely helpful | 38 (44.7) | |

| Helpful | 15 (17.6) | |

| Neutral | 17 (20.0) | |

| Unhelpful | 11 (12.9) | |

| Extremely unhelpful | 4 (4.8) | |

| Do you need help from psychologist/counselor if you face anxiety? | Yes | 231 (54.7) |

| No | 191 (45.3) | |

Most of the participants (54.7%) revealed that they would prefer help from psychologist or counselor if they ever experience anxiety in the future (Table 7).

Correlation between professional and informal sources for help-seeking towards anxiety among the participants

Table 8 shows that professional and informal preferences were positively correlated towards anxiety (rpi=0.3).

Table 8.

Correlation between professional and informal preferences among the study participants

| Characteristics | Help-seeking preference | Correlation coefficient (r) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Professional | 0.3* | <0.05 |

| Informal |

P-value less than 0.05 level.

Discussion

This study showed that few of the participants were extremely likely to seek help from professionals, that is psychologists (16.6%) and psychiatrists (17.5%). Our findings are consistent with the similar studies conducted in Ethiopia (12.1%) and Canada (13%)9,27. It is due to delay in problem sharing with someone, service cost, lengthy waiting time at service center and inadequate advice from the mental health professionals27. In contrast to our study, older adults of Australia preferred to seek help from general practitioners if they ever experience anxiety28.

This study revealed that most of the participants preferred seeking help from informal sources than professional sources for anxiety. This finding is similar to the relevant studies conducted in Australia, Canada, and Italy5,27,29. Among informal sources, they were extremely likely to seek help from intimate partner (32.5%) and parents (36.5%), which is consistent with the studies conducted in Ethiopia and Canada9,27. It is due to the likelihood that relationship issues, personal issues, and educational issues would be discussed with friends, parents, and teachers, respectively5. Another reason can be, established relationships are also premised on trust, open communication, and familiarity, hence enhancing natural gravitation to these sources. In addition, if the professional help is not easily accessible or is financially burdensome, some individual turns to informal sources for support5. However, a study conducted in China showed friends (78.2%) and family (60.3%) were the most favorable choices for seeking help as informal sources30.

This study demonstrated that males had 1.5 times higher odds to seek help from friends compared to females. It might be due to stigma associated with mental health issues affecting both sexes, but it might manifest differently. Another reason might be men might avoid seeking help due to fears of being perceived as weak, while women might feel concerned about being labeled as unstable. In contrast to our study, study conducted in Italy revealed female students preferred friend to seek help to their counterpart29. However, another study in Saudi Arabia found that there was no difference between sex and help-seeking practices towards mental health problems31.

This study demonstrated non-medical students seek more help from parents and friends than medical students, while, medical students having common mental issues sought more help from informal sources. Our study finding is supported by a study conducted in Ethiopia32. It might be that medical students often face high expectations and pressure to appear competent in their professional setting. Non-medical students, who may not experience the same level of scrutiny, might feel more comfortable seeking help from informal sources. Furthermore, medical students who were aware of mental health issues were likely to seek help from mental healthcare professionals in Saudi Arabia31.

This study showed Hindus had 2.3 times higher odds to seek help from traditional healers compared to other religions. This is justified in a study done in Nepal, where individuals with mental issues choose to approach faith healers first due to local trust in their efficacy, accessibility, and perception that mental issues is brought on by the supernatural33.

This study showed that 9% of students would never seek help that is similar to the study done in Italy (9%)29. However, in older population, the proportion to seek help was slightly more (18.1%) than adults34. Many of the students believed fear of criticism (34.2%), and social stigma (20.3%) were the major barriers for not seeking help while having mental disorders. Our findings are similar to the study conducted in Australia and Ethiopia5,9. Meanwhile, other studies revealed that afraid of hospitalization, financial issues, unavailability of counseling services, emotional incompetence, unfavorable attitudes/beliefs were also the additional barriers in seeking help towards mental disorders among adults5,27,35.

This study reported that students had positive experiences when they sought help from doctors and psychiatrists while struggling with anxiety previously. This finding is coherent with the study conducted in Ethiopia9. This study reported half of the students would prefer to seek help from psychologists and/or counselors if they ever experience anxiety. This finding is consistent with a study conducted among senior citizens in Germany34.

Furthermore, there was a positive correlation between professional and informal help-seeking sources in this study. Many studies showed that people prefer sequential help where individuals often seek informal help first and then turn to professional sources if the informal support does not adequately address their needs5.

This study highlighted that informal sources were the leading component for help-seeking among students. In an another study, young adults were more likely to turn to health professionals for help if they understood what it meant to have faith in people in general, were aware of their sentiments, could manage them, and could express them5,29. Also, this study highlighted to expand of professional care as the real and best source of help to improve counterproductive outcome among the students.

All these findings emphasize to the importance of better coordination with wellness centers, and the recommendations presented here are mainly concerned with expanding students’ access to professional mental health services and resources27. Furthermore, professional help and reliable information should be made accessible in colleges and other educational settings for the young as well as students36. This will aware the students to enhance positive attitude in help-seeking towards anxiety and to avoid the negative beliefs/barriers for seeking help. Interventions targeting mental health literacy are needed to inform the public about the symptoms, treatable nature and types of interventions for any mental problems, to decrease stigma and to generate realistic expectations towards mental health and its treatments6.

Strengths and limitations

This study included the participants from the diverse schools and colleges of the university which is generalizable in different educational institution settings. Relationship between professional and informal help-seeking sources were determined in this study as highlighted by previous studies.

Besides strengths, there were some limitations of this study. Firstly, the study relies on self-report measures, therefore, some participants may not have responded accurately or honestly. Secondly, due to web-based survey, some targeted participants were unable to involve especially who were not access to an internet connection.

Conclusion

This study showed that undergraduate students that preferred to seek help from informal rather than professional sources. There is still stigma among the students regarding mental health. This suggests that there is a need to have psychosocial intervention in their colleges and educational institutions for professional help-seeking. Further research is required to address the substantial public health problems and socio-cultural aspects in order to understand facilitator and barriers associated with student’s anxiety and HSB. As well, providers should engage in active collaboration across service sectors to help students in finding the most suitable professional help-seeking preferences towards any mental disorders.

Ethical approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC) [Ref no: 3368]. In addition,

a letter of support was obtained from Dean office of the Kathmandu University before the start of data collection. Study objectives were explained in the Google Form and e-informed consent was taken from each study participant.

Consent

Since the study is web-based; however, study objectives were explained in the Google Form and e-informed consent was taken from each study participant.

Source of funding

There was no source of funding for this study.

Author contribution

R.A.: conceptualization, methodology, implementation, formal analysis, and writing original draft of the manuscript; M.R.: methodology, formal analysis, writing and reviewing the original draft of the manuscript; S.P.: manuscript review and editing; S.R.: manuscript review and editing; P.M.: manuscript review and editing; S.B.: supervised the study and approved the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest disclosures

All the authors declare no conflicts of interest for this study.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

Researchregistry9512.

Guarantor

Manish Rajbanshi.

Data availability statement

Data will be available at the request to the corresponding author.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Department of Public Health, Om Health Campus, Purbanchal University, Nepal and Kathmandu University School of Science, Nepal for their guidance during the research project. Our gratitude goes to individuals responding to the questionnaire. Additionally, appreciation goes to the individuals for their communication and coordination during the period of study.

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Published online 2 December 2023

Contributor Information

Richa Aryal, Email: richaryal7@gmail.com.

Manish Rajbanshi, Email: manishrajbanshi717@gmail.com.

Sushma Pokhrel, Email: sushma.pokhrel0237@gmail.com.

Sushama Regmi, Email: rgsushama@gmail.com.

Prajita Mali, Email: prajitamali@gmail.com.

Swechhya Baskota, Email: swekshya@gmail.com.

References

- 1.https://www.apa.org [Internet]. Accessd 25 Aug 2023. Anxiety. https://www.apa.org/topics/anxiety.

- 2.Hunt J, Eisenberg D. Mental health problems and help-seeking behavior among college students. J Adolesc Health 2010;46:3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doll CM, Michel C, Rosen M, et al. Predictors of help-seeking behaviour in people with mental health problems: a 3-year prospective community study. BMC Psychiatry 2021;21:432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C, et al. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:476–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rickwood D, Deane FP, Wilson CJ, et al. Young people’s help-seeking for mental health problems. Aust E-J Adv Ment Health 2005;4:218–251. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H, et al. A systematic review of help-seeking interventions for depression, anxiety and general psychological distress. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boldero J, Fallon B. Adolescent help-seeking: what do they get help for and from whom? J Adolesc 1995;18:193–209. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campion J, Bhui K, Bhugra D. European Psychiatric Association (EPA) guidance on prevention of mental disorders. Eur Psychiatry 2012;27:68–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tesfaye Y, Agenagnew L, Tucho GT, et al. Attitude and help-seeking behavior of the community towards mental health problems. PLoS One 2020;15:e0242160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wainberg ML, Scorza P, Shultz JM, et al. Challenges and opportunities in global mental health: a research-to-practice perspective. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2017;19:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwartz KD, Exner-Cortens D, McMorris CA, et al. COVID-19 and student well-being: stress and mental health during return-to-school. Can J Sch Psychol 2021;36:166–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.https://www.who.int/about/accountability/results/who-results-report-2020-mtr/country-story/2020/nepal-mental-health Addressing the mental health needs during COVID-19 pandemic in Nepal [Internet]. Accessd 22 Jun 2023.

- 13.Dhimal M, Dahal S, Adhikari K, et al. A nationwide prevalence of common mental disorders and suicidality in Nepal: evidence from National Mental Health Survey, 2019-2020. J Nepal Health Res Counc 2021;19:740–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gautam K, Adhikari RP, Gupta AS, et al. Self-reported psychological distress during the COVID-19 outbreak in Nepal: findings from an online survey. BMC Psychol 2020;8:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adhikari A, Dutta A, Sapkota S, et al. Prevalence of poor mental health among medical students in Nepal: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ 2017;17:232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhami DB, Singh A, Shah GJ. Prevalence of depression and use of antidepressant in basic medical sciences students of Nepalgunj Medical College, Chisapani, Nepal. J Nepalgunj Med Coll 2018;16:32–36. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paudel S, Gautam H, Adhikari C, et al. Depression, anxiety and stress among the undergraduate students of Pokhara Metropolitan, Nepal. J Nepal Health Res Counc 2020;18:27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karki A, Thapa B, Pradhan PMS, et al. Depression, anxiety and stress among high school students: a cross-sectional study in an urban municipality of Kathmandu , Nepal. PLOS Glob Public Health 2022;2:e0000516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aryal KK. Global school based student health survey Nepal, 2015. Nepal Health Research Council; 2017. https://nhrc.gov.np/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Ghsh-final-with-cover-and-anex.pdf

- 20.Wahab S, Shah NE, Sivachandran S, et al. Attitude towards suicide and help-seeking behavior among medical undergraduates in a Malaysian university. Acad Psychiatry 2021;45:672–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jahan I, Sharif AB, Hasan ABMN. Suicide stigma and suicide literacy among Bangladeshi young adults: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychiatry 2023;14:1160955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kathmandu University [Internet] . Accessd 1 Aug 2023. https://ku.edu.np/about-us https://ku.edu.np/about-us

- 23.Nanjundeswaraswamy D, Divakara S. Determination of sample size and sampling methods in applied research. Proc Eng Sci 2021;3:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson CJ, Deane FP, Ciarrochi JV, et al. Measuring help seeking intentions: Properties of the General Help Seeking Questionnaire. Canadian Journal of Counselling. 2005:39;15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shumet S, Azale T, Angaw DA, et al. Help-seeking preferences to informal and formal source of care for depression: a community-based study in Northwest Ethiopia. Patient Prefer Adher 2021;15:1505–1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mathew G, Agha R, Albrecht J, et al. STROCSS 2021: strengthening the reporting of cohort, cross-sectional and case-control studies in surgery. Int J Surg Lond Engl 2021;96:106165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samuel R, Kamenetsky SB. Help-seeking preferences and factors associated with attitudes toward seeking mental health services among first-year undergraduates. Can J High Educ 2022;52:30–50. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson K, Wickramariyaratne T, Blair A, et al. Help-seeking intentions for anxiety among older adults. Aust J Prim Health 2017;23:489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.D’Avanzo B, Barbato A, Erzegovesi S, et al. Formal and informal help-seeking for mental health problems. A survey of preferences of italian students. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health CP EMH 2012;8:47–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao M, Hu M. A multilevel model of the help-seeking behaviors among adolescents with mental health problems. Front Integr Neurosci 2022;16:946842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Almanasef M. <P>Mental health literacy and help-seeking behaviours among undergraduate pharmacy students in Abha, Saudi Arabia</P>. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2021;14:1281–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gebreegziabher Y, Girma E, Tesfaye M. Help-seeking behavior of Jimma university students with common mental disorders: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2019;14:e0212657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pradhan SN, Sharma SC, Malla DP, et al. A study of help seeking behavior of psychiatric patients. J Kathmandu Med Coll 2013;2:21–24. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hohls JK, König HH, Eisele M, et al. Help-seeking for psychological distress and its association with anxiety in the oldest old – results from the AgeQualiDe cohort study. Aging Ment Health 2021;25:923–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heinig I, Wittchen HU, Knappe S. Help-seeking behavior and treatment barriers in anxiety disorders: results from a representative German community survey. Community Ment Health J 2021;57:1505–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelly CM, Jorm AF, Wright A. Improving mental health literacy as a strategy to facilitate early intervention for mental disorders. Med J Aust 2007;187(S7):S26–S30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available at the request to the corresponding author.