Abstract

Purpose:

Screening with low dose computed tomography (CT) can reduce lung cancer related death at the expense of unavoidable false positive results. The purpose of this study is to measure the rate of surgery for benign nodules, and evaluate characteristics of those nodules.

Materials and Methods:

In this study, we evaluated patients in the Lung Cancer Screening (LCS) program across a large tertiary healthcare network from 5/2015 through 10/2021 who underwent surgical resection for a lung nodule. We reviewed the pathology reports and subsequent follow-up to establish whether the nodule was benign or malignant, and only benign nodules were included for this study. Imaging characteristics of the nodules were evaluated by a radiology fellow, and we recorded Lung-RADS category, nodule status (baseline, stable, new, growing), FDG uptake on PET/CT, and calculated the risk from the Brock model.

Results:

During this time period, a total of 21366 LCS CT was performed in 9050 patients, and 260 patients underwent a following surgical resection. Review of the pathology results revealed: 220 lung cancer (85%), 2 other malignancies (1%), and 38 benign findings (15%). Pathology of the benign nodules was as follows: 12 with scarring/fibrosis, 5 with benign neoplasms, 14 with infection/inflammation, and 7 with other diagnoses. Lung-RADS category was as follows: 4 (11%) Lung-RADS 2, 2 (5%) Lung-Rad 3, 11 (29%) Lung-RADS 4A, 13 (34%) Lung-RADS 4B, and 8 (21%) Lung-RADS 4X. The size of the nodules ranged from 4 to 41 mm with a median of 13 mm. 2 (5%) were ground glass, 10 (26%) were part-solid, and 26 (68%) were solid. FDG-PET/CT was performed in 19 out of 38 cases, of which:2 (11%) had no uptake, 10 (53%) had mild uptake, 3 (16%) had moderate uptake, and 4 (21%) had intense uptake. Risk assessment by Brock calculator revealed that 9 (24) had <5% (very low) risk; 27 (71%) had 5–65% (low-intermediate) risk, and 2 (5%) had >65% (high) risk.

Conclusion:

Surgical resection of benign nodules is unavoidable despite application of Lung-RADS guidelines in a modern screening program, with approximately 15% of surgeries being done for benign lesions.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in both men and women in the United States(1). Large multicenter trials reported that screening with low dose computed tomography (LDCT) reduces lung cancer mortality. For example, in the United States, the National Lung Cancer Screening Trial (NLST), demonstrated a 20% relative reduction in lung cancer deaths in individuals aged 55 to 74 years with a smoking history of 30 pack-years or greater(2,3). However, this comes at the expense of unavoidable false positive results leading to unnecessary follow-ups, procedures, and surgeries for benign lung nodules(4).

The rate of surgery for benign nodules dropped from approximately 50% in the mid 1990s to 20% in a recently published study(5). Data from the NLST showed a rate of 28% for benign surgeries(6), and data from the Dutch-Belgian NELSON study revealed a rate of 23%(7). In order to standardize the reporting and management of screened lung nodules, the American College of Radiology introduced the Lung CT Screening Reporting and Data System (Lung-RADS) in 2014 (8). However, the effect of Lung-RADS on benign surgeries is unclear, and the benign surgery rate in a modern, real-world lung cancer screening program remains to be determined.

In this study, we evaluated patients in the Lung Cancer Screening (LCS) program across a large tertiary healthcare network who underwent surgical resection for a lung nodule. The purpose of this study was to measure the rate of surgery for benign nodules and evaluate characteristics of those nodules.

Materials and Methods

Patient selection.

This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board with waiver of informed consent. All patients in the Lung Cancer Screening program across our healthcare network from 5/2015 through 10/2021 who underwent surgery for a lung nodule were included. Of note, this healthcare network includes two large, tertiary academic medical centers and two community hospitals. Patient data and pathology reports were extracted from the electronic medical record, and data was collected using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)(9).

The pathology reports from each nodule resection were reviewed, and the final diagnosis was confirmed by manual chart review. Nodules that were discovered on non-lung cancer screening CTs were excluded. For comparison of benign and malignant nodules, all patients with benign nodules were included, and a random sample of 100 patients with malignant lung nodules was included. Only one nodule was considered for each patient, that with the most suspicious features.

Image review.

An oncologic radiology fellow with 6 years of experience in diagnostic imaging reviewed the last screening CT before the surgery. For each CT, the presence of emphysema was recorded as well as nodule characteristics: size (based on its maximal axial diameter), nodule type (ground glass, part-solid, or solid), nodule status (baseline, stable, new, or growing), upper lobe location, presence of spiculation, and total number of nodules. Lung-RADS category and FDG-uptake on PET/CT (none, mild, moderate, intense), if performed, were also recorded. Risk of lung cancer was then calculated using the Brock risk calculator(10). Brock risk scores were divided into the ACCP categories: <5% (very low risk), 5–65% (low-moderate risk), and >65% (high risk)(11).

Statistical analysis.

Data was analyzed in JMP Pro v17 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Comparisons between benign and malignant nodules based on surgical pathology results were made using χ2 test or the Fisher exact test. Frequencies and percentages and the corresponding P values were calculated. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

During the study period, a total of 21366 LCS CT was performed in 9050 patients, and 260 patients underwent surgical resection for lung nodules. Review of the pathology results revealed: 220 lung cancers (85%), 2 other malignancies (1%), and 38 benign findings (15%). Pathology of the benign nodules was as follows: 12 with scarring/fibrosis, 6 with benign neoplasms (4 hamartomas, 1 sclerosing pneumocytoma, and 1 inflammatory pseudotumor), 13 with infection/inflammation (including granulomatous inflammation, cryptococcosis, organizing pneumonia, and abscess), and 7 with other diagnoses (1 vascular anomaly, 1 intrapulmonary lymph node, 2 bronchial metaplasia, 1 alveolar congestion, 2 Langerhans cell histiocytosis). Illustrative examples of benign nodules that were resected include fungal infection (Figs 1 and 2), benign neoplasm (sclerosing pneumocytoma) (Fig 3), and scarring (Fig 4).

Figure 1.

68-year-old female presenting for screening LDCT with new spiculated part solid left upper lobe nodule, on a background of severe emphysema (Lung-RADS category 4X). Pathology reveals abscess with fungal hyphae.

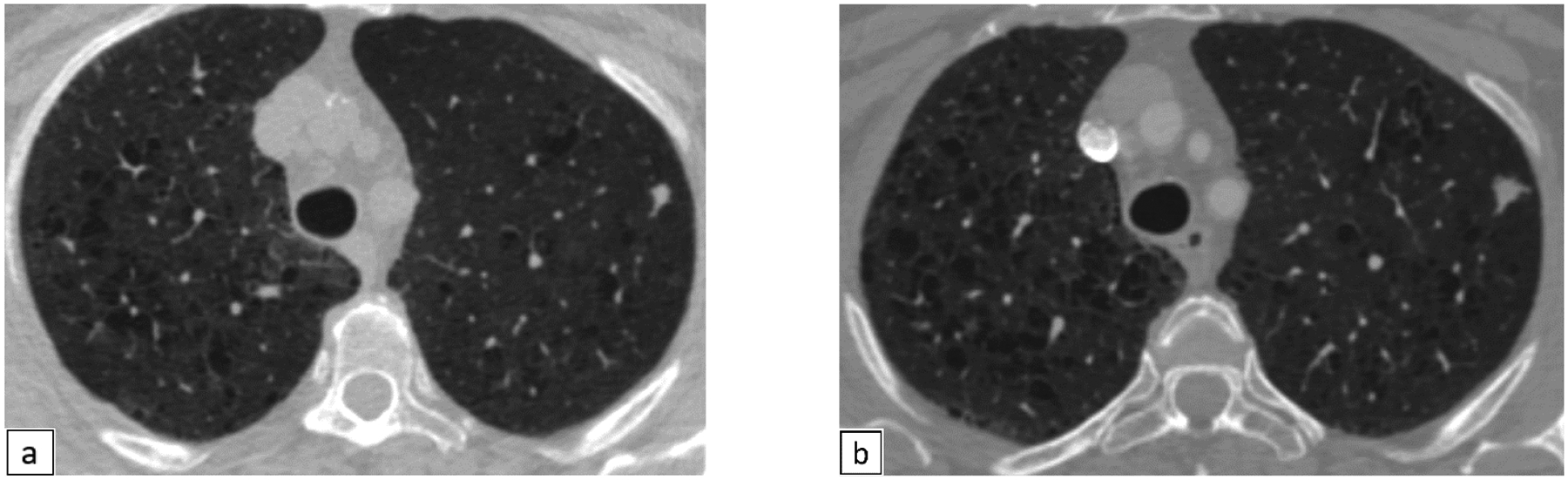

Figure 2.

65 year old female with new left upper lobe nodules (Fig 2a) (Lung-RADS category 4X). These were mildly FDG-avid on PET/CT (Fig 2b). Pathology reveals necrotizing granulomas containing numerous hyphae of uniform width, with septations and acute angle branching, consistent with aspergillus or another hyaline mold.

Figure 3.

67-year-old female presenting with a 7 mm left upper lobe nodule, Lung-RADS category 4X (Fig 3a). Follow up scan after 6 months reveals increase in the size and spiculation, now measuring 10 mm (Lung-RADS category 4X) (Fig 3b). Pathology reveals sclerosing pneumocytoma.

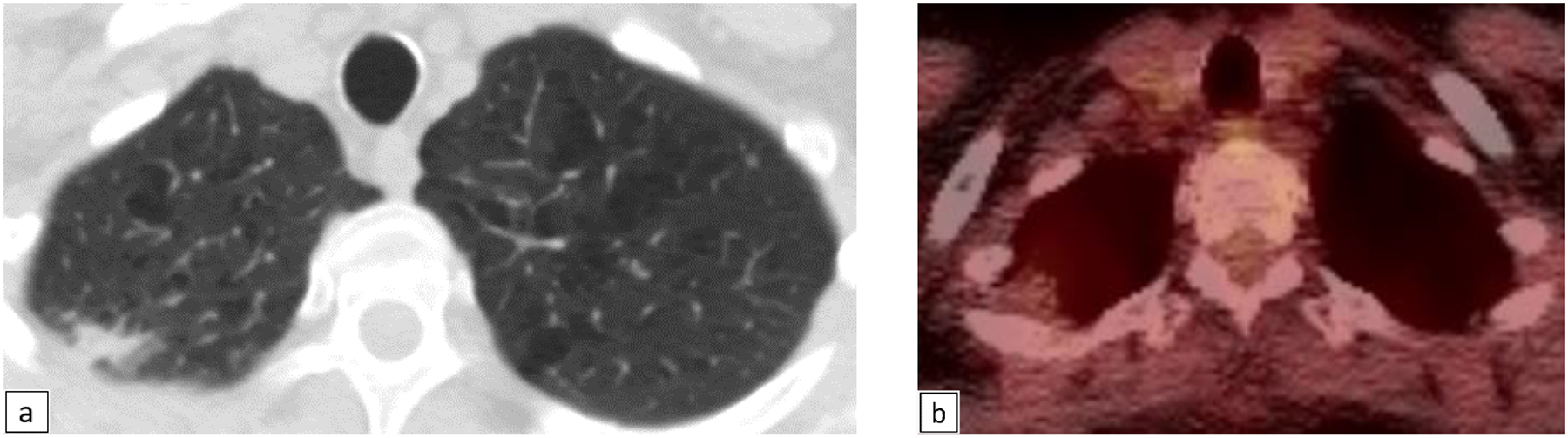

Figure 4.

68-year-old female with right upper lobe subpleural irregular nodular opacity (Fig 4a), Lung-RADS category 4X. This was minimally FDG-avid on PET/CT (Fig 4b). Pathology revealed fibroelastic scar.

Patient and nodule characteristics are shown in Table 1. 32 (84%) of cases with benign resection were Lung-RADS 4A, 4B, or 4X, whereas 94 (94%) of cases with malignant resection were Lung-RADS 4A, 4B, or 4X (p=0.02). The size of benign and malignant resected nodules did not differ significantly (median of 13 versus 14 mm, p=0.4). FDG-PET/CT was performed in 19 benign cases, of which: 2 (11%) had no uptake, 10 (53%) had mild uptake, 3 (16%) had moderate uptake, and 4 (21%) had intense uptake; this distribution was not significantly different compared to malignant nodules. Of the patients with benign nodules, 4 (11%) underwent pre-operative non-invasive biopsy, and 19 (19%) patients with malignant nodules underwent pre-operative biopsy (p=0.18).

Table 1.

showing the difference in characteristics between benign and malignant lung nodules.

| Benign resections (n=38) | Malignant resections (n=100) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Sex | Male | 20 (53%) | 44 (44%) | 0.2 |

| Female | 18 (47%) | 56 (56%) | ||

| Patient Age | Median | 65 | 66 | 0.3 |

| Range | 58–80 | 55–78 | ||

| Nodule Size | Median | 13 | 14 | 0.4 |

| Range | 4–41 | 5–66 | ||

| Nodule Type | Ground glass | 2 (5%) | 11 (11%) | 0.3 |

| Part Solid | 10 (26%) | 34 (34%) | ||

| Solid | 26 (68%) | 55 (55%) | ||

| Spiculated Nodule | Yes | 15 (39%) | 39 (39%) | 0.6 |

| No | 23 (61%) | 61 (61%) | ||

| Lung-RADS | 2 | 4 (11%) | 1 (1%) | 0.02 |

| 3 | 2 (5%) | 5 (5%) | ||

| 4A | 11 (29%) | 23 (23%) | ||

| 4B | 13 (34%) | 26 (26%) | ||

| 4X | 8 (21%) | 45 (45%) | ||

| Nodule status: | Baseline | 7 (18%) | 27 (27%) | 0.3 |

| Stable | 3 (8%) | 12 (12%) | ||

| New | 9 (24%) | 12 (12%) | ||

| Growing | 19 (50%) | 49 (49%) | ||

| FDG-uptake if PET/CT done: | None | 2 (11%) | 7 (9%) | 0.12 |

| Mild | 10 (53%) | 19 (25%) | ||

| Moderate | 3 (16%) | 20 (26%) | ||

| Intense | 4 (21%) | 30 (39%) | ||

| Pre-operative Biopsy | Yes | 4 (11%) | 19 (19%) | 0.18 |

| No | 34 (89%) | 81 (81%) | ||

| Brock calculator category: | Very low (<5% risk) | 9 (24%) | 8 (8%) | 0.03 |

| Low-Moderate (5–65% risk) | 27 (71%) | 88 (88%) | ||

| High (>65% risk) | 2 (5%) | 4 (4%) | ||

Wilcoxon test was used for the p-values of patients age and nodule size.

Risk assessment by Brock calculator revealed that for benign nodules, 9 (24%) had <5% (very low) risk; 27 (71%) had 5–65% (low-moderate) risk, and 2 (5%) had >65% (high) risk. This differed from malignant nodules in which 8 (8%) had very low risk, 88 (88%) had low-moderate risk, and 4 (4%) had high risk, p=0.03. Of note, of the resected benign nodules, 19 (50%) were growing , 9 (24%) were new, 15 (39%) were spiculated , and 32 (84%) were characterized as Lung-RADS 4 [11 (29%) Lung-RADS 4A, 13 (34%) Lung-RADS 4B, 8 (21%) Lung-RADS 4X] (Table 1).

Discussion

In our lung screening program performed in a large healthcare network, we found a benign surgical resection rate of 15%. Characteristics of the benign and malignant nodules had substantial overlap in terms of size, FDG uptake, and Brock risk score. 28 out of the 39 (74%) resected benign lung nodules were either growing or new and 7 out of 9 (78%) of the very low risk nodules were growing.

Our rate of benign surgeries compares favorably to the rate in the NLST and NELSON trials (which reported 23–28%) (3). One difference between our study and NLST is the implementation of Lung-RADS, which was designed to reduce the false positive rate. Our rate of benign resection is similar to the International-Early Lung Cancer Action Program (I-ELCAP) which reported an 11% surgical rate for benign pathologies(2).

In our study, the benign resected lung nodules shared overlapping features with malignant nodules, making differentiation between these categories difficult, even in retrospect. Machine learning and deep learning artificial intelligence techniques are promising for nodules characterization (12) . Other new techniques such as non-invasive breath tests (12). However validation of these models is yet to be finalized (12). Some prior studies favor volumetric growth rate assessment as used in the NELSON trial. However, direct comparisons have shown no substantial difference in nodule characterization(13). Our study showed that eliminating benign lung surgeries may not be feasible with currently available conventional imaging techniques and guidelines.

Our study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study. Second, even though Lung-RADS was used for nodules classification, the decision for short term follow up versus surgery was taken by individual physician opinion rather than a standardized protocol. In addition, while our healthcare network includes two community hospitals, it is dominated by large academic centers, and results may not generalize to networks that only contain community hospitals.

In conclusion, surgical resection of benign nodules is unavoidable despite application of Lung-RADS guidelines in a modern screening program, with approximately 15% of surgeries being done performed for benign lesions.

More conservative approaches for equivocal cases, such as a multidisciplinary team approach, lung nodule biopsy, or short-term follow-up, should be considered before direct referral to surgery, which may help prevent unnecessary operations on benign pathologies. Future work in artificial intelligence may help triage nodules better and avoid unnecessary surgeries.

Highlights.

Benign lung nodules can share imaging features with malignant nodules, including high Lung-RADS category, growth, and increased FDG activity.

Surgical resection of benign nodules is unavoidable in a screening program despite application of Lung-RADS guidelines.

In our lung cancer screening cohort, the rate of resection of benign lung nodules was 15 %.

The authors report relevant financial disclosures.

MMH supported by the National Cancer Institute (R01CA260889).

Declaration of interests

Mark Hammer reports financial support was provided by NIH R01CA260889. Mark Hammer reports a relationship with NIH R01CA260889 that includes: funding grants.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(1):17–48. doi: 10.3322/caac.21763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flores R, Bauer T, Aye R, et al. Balancing curability and unnecessary surgery in the context of computed tomography screening for lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147(5):1619–1626. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Low-Dose Computed Tomographic Screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rzyman W, Jelitto-Gorska M, Dziedzic R, et al. Diagnostic work-up and surgery in participants of the Gdansk lung cancer screening programme: the incidence of surgery for non-malignant conditions. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2013;17(6):969–973. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivt388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies B. Solitary pulmonary nodules: pathological outcome of 150 consecutively resected lesions. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2005;4(1):18–20. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2004.091843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Results of Initial Low-Dose Computed Tomographic Screening for Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(21):1980–1991. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van’t Westeinde SC, Horeweg N, De Leyn P, et al. Complications following lung surgery in the Dutch-Belgian randomized lung cancer screening trial. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;42(3):420–429. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin MD, Kanne JP, Broderick LS, Kazerooni EA, Meyer CA. Lung-RADS: Pushing the Limits. RadioGraphics. 2017;37(7):1975–1993. doi: 10.1148/rg.2017170051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McWilliams A, Tammemagi MC, Mayo JR, et al. Probability of Cancer in Pulmonary Nodules Detected on First Screening CT. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(10):910–919. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gould MK, Donington J, Lynch WR, et al. Evaluation of individuals with pulmonary nodules: When is it lung cancer?: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: american college of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(5_suppl):e93S–e120S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joy Mathew C, David AM, Joy Mathew CM. Artificial intelligence and its future potential in lung cancer screening. EXCLI J 19Doc1552 ISSN 1611–2156. IfADo - Leibniz Research Centre for Working Environment and Human Factors, Dortmund; 2020; doi: 10.17179/EXCLI2020-3095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammer MM, Byrne SC. Cancer Risk in Nodules Detected at Follow-Up Lung Cancer Screening CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2022;218(4):634–641. doi: 10.2214/AJR.21.26927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]