Abstract

Background

There is a lack of evidence-based app guidance for parents of children with crying, sleeping, and feeding problems who are often highly burdened and not likely to seek professional help. A new psychoeducational app for parents providing scientifically sound information via text and videos, a diary function, selfcare strategies, a chat forum and a regional directory of specialized counseling centers may serve as a low-threshold intervention for this target group.

Objective

We investigated how parents perceived the app in terms of the following: (1) overall impression and usability, (2) feedback on specific app functions regarding usefulness and (3) possible future improvements.

Methods

Our clinical sample of N = 137 parents of children aged from 0 to 24 months was recruited from a cry baby outpatient clinic in Southern Germany between 2019 and 2022. A convergent parallel mixed methods design was used to collect and analyse cross-sectional data on app evaluation. After app use within the framework of a clinical trial, parents filled in an app evaluation questionnaire.

Results

Most participants used the app at least once a week (86, 62.8 %) over an average period of 19.06 days (SD = 15.00). Participants rated overall impression and usability as good, and the informational texts, expert videos and regional register of counseling centers as appealing and useful. The diary function and chat forum were found to be helpful in theory, but improvements in implementation were requested, such as a timer function for the diary entry. Regarding future functionality, parents posed several suggestions such as the option to contact counseling centers directly via app, and the inclusion of the profile of their partners.

Conclusions

Positive ratings of overall impression, usability, and specific app functions are important prerequisites for the app to be effective. App-based guidance for this target group should include easy-to-use information. The app is intended to serve as a secondary preventive low-threshold offer and to complement professional counseling.

Keywords: Crying problems, Sleeping problems, Feeding problems, Regulatory problems, Mhealth, Psychoeducation, Mobile Health Care, health app, mobile app, patient education, pobile health, eHealth, parenting, baby, babies, sleep, crying, feeding, newborn, mobile phone

Highlights

-

•

Families with child crying/sleeping/ feeding problems face barriers to seek support.

-

•

There is a lack of evidence-based app interventions for this target group.

-

•

A new psychoeducational app intends to close existing gaps in supply.

-

•

Regular use and positive feedbacks are important prerequisites for app acceptance.

-

•

Parents posed several suggestions to optimize the app offer for affected families.

1. Introduction

Digital mental health intervention programs have grown increasingly popular in recent years, reaching a peak during the COVID-19 pandemic (Felix Burda Stiftung, 2020), when access to health care was partially restricted due to physical distancing and stay-at-home policies. Digital sources have become a commonly used way for parents to obtain health-related information: For example, in a study by Bryan et al. (2020), about 94 % of parents of children age 0–5 reported that they used online health information, with a quarter even using it daily.

One particularly vulnerable group that has been neglected in the field of digital mental health care are families with children with crying, sleeping, and feeding problems. Prevalence rates of these problems in the first years of life range from 5 to 43 % depending on the exact definition and diagnostical procedures (Bilgin and Wolke, 2016; Petzoldt et al., 2016; Cook et al., 2019). In the context of excessive crying, sleeping, and feeding problems, parents frequently feel highly stressed and ineffective in their parenting role (Stifter and Bono, 1998; Papoušek, 2004; Vik et al., 2009). Extreme distress may increase the risk of shaking the child, which can cause severe and irreversible brain damage (Barlow and Minns, 2000; Barr et al., 2006). Longitudinal studies suggest that early crying, sleeping and feeding problems can persist into preschool and elementary school years (Wolke et al., 1998; Ammaniti et al., 2012) and are linked to infant-mother attachment disorganisation (Bilgin and Wolke, 2020) as well as psychopathology in later childhood until adulthood (Hemmi et al., 2011; Bäuml et al., 2019; Wolke et al., 2023). Hence, early prevention and intervention is specifically important to potentially mitigate these risks and reduce parenting stress.

However, in terms of professional support, affected families often hesitate to seek professional help as they might fear to be judged negatively by their social environment and professional care workers (Garratt et al., 2019). Moreover, the internet offers a vast amount of health related information, making it difficult to distinguish reliable and unreliable information (Haschke et al., 2018; Bryan et al., 2020).

A concise evidence-based app could provide a low-threshold approach to provide reliable information and motivate parents to overcome barriers to seek professional advice. Psychoeducational apps developed for parents of infants are scarce and the vast majority of the existing apps in this field lack empirical evidence (Sardi et al., 2020; Simon et al., 2022). A few studies investigated effects of psychoeducational app interventions in the postpartum period on parental outcomes such as self-efficacy, perceived social support, parenting satisfaction or postpartum depression (Shorey et al., 2017; Chan et al., 2019; Larkin et al., 2019; Linardon et al., 2019). Further, some studies investigated the effects of app interventions on child outcomes such as infant sleeping problems (Leichman et al., 2020; Hiscock et al., 2021). However, there are three limitations of the existing studies. First, many existing apps have focused on the overall postpartum period but not specifically on child crying, sleeping, and feeding symptoms. Second, some studies address one problem behavior such as sleeping (Leichman et al., 2020; Hiscock et al., 2021), while not taking into account that other symptoms such as crying/feeding problems often co-occur (Papoušek, 2004; Bilgin et al., 2020). Third, many apps primarily have relied on a few functions such as only tracking the behaviors (e.g. feeding patterns), or focus on either parent or child outcomes which does not include the benefits of using a combination of psychoeducational input and interactive elements (Sardi et al., 2020).

For this reason, we have developed a scientifically sound integrative app targeting crying, sleeping, and feeding problems between the age of 0 to 24 months (Augustin et al., 2023). Psychoeducational information was included since psychoeducation on specific mental health problems are known to help to reduce stigma, build coping skills, increase empowerment, reduce symptoms, and promote treatment adherence (Hatfield, 1988; Daley et al., 1992; Bäuml and Pitschel-Walz, 2003; Lang and Simhandl, 2009; Bäuml and Pitschel-Walz, 2012). Multimodal information presentation, such as texts, videos and audios were used to enhance learning since the usage of mixed cues can increase comprehension and might also address patients with literacy difficulties (Murphy et al., 2000; Mayer, 2003). As tracking functions might support a better understanding of infant behavior patterns (Dienelt et al., 2020), a diary function was also implemented in the current app. Relaxation strategies were integrated because parents of children with crying, sleeping, and feeding problems often experience high levels of parenting stress (Papoušek, 2004) and relaxation tools have been reported to be helpful in this regard (Schlarb and Brandhorst, 2012; Roberts et al., 2020). As research has shown that social support and sharing experiences can reduce levels of postnatal distress and improve mental health (Jacobson, 1986; Heh, 2003), a chat forum was also part of the app. In order to facilitate access to professional advice, a clearly arranged register of counseling centers in Bavaria (Southern Germany) was included.

To our knowledge, this is the first scientifically based and evaluated psychoeducational app targeting parents of children with crying, sleeping, and feeding problems as commonly co-occuring symptom patterns. In an RCT, the app has shown to reduce parenting stress and increase knowledge about child crying, sleeping, and feeding (Augustin et al., 2023).

In the present study, we aimed to complement these findings about the effectiveness by considering quantitative and qualitative parental feedbacks about the app and thus taking into account usability and usefulness as important prerequisites for user acceptance (Venkatesh et al., 2003). We investigated (1) how parents perceived the app in terms of overall impression and usability (2) which app functions were considered particularly useful and (3) which future improvements were requested.

2. Methods

2.1. Overview

Data for app evaluation was retrieved within the framework of a monocentric, prospective, randomized controlled clinical study (register number: DRKS00019001, German Register of Clinical Studies [DRKS], approval by the Ethics Committee of the Technical University of Munich, vote number: 56/18 S) during 2019 to 2022. Cross-sectional data on overall impression and usability, feedback on the usefulness of specific app functions and suggestions for future improvements by the target group were collected using a questionnaire after parents had used the app. A convergent parallel mixed methods design was used for analyses (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2011).

2.2. App development

The app was developed in line with the Medical Research Council (MRC) guidelines (Craig et al., 2008), see Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

App development in line with MRC guidelines (Craig et al., 2008).

2.3. App content and functions

2.3.1. Information on crying, sleeping, feeding

For each of the three topics, a short version in simple language and a more detailed version for in-depth information were provided (see Fig. 2 for app design). The information was organized into main themes and short topics. Each section included three components: (1) Information on the variability of child behavior (ranging from normal to noticeable problems) as well as reasons/stimuli for and meaning of a certain behavior were provided in order to understand the child's cues better. (2) Advice on how to deal (do's and don'ts) with their child's behaviors in daily life (e.g., implementation of bedtime rituals) were given. (3) Parents were encouraged to seek professional support, e.g. if the situation was perceived as very stressful. An emergency plan provided initial guidance on how to de-escalate extreme psychological distress and emergency telephone numbers. Furthermore, information on what to generally expect during professional counseling was provided.

Fig. 2.

Screenshot examples.

Note. A) Home screen including easy-accessible buttons to find information about crying, sleeping, and feeding and an emergency plan. B) Menu including several additional functions. C) Example for psychoeducational information, divided into a short, easy comprehensible version, a long version for in-depth information and links to expert videos. D) Integrated youtube videos including short interviews with experts answering frequent questions. E) Diary function including a PDF export option. F) Example for information about counseling centers including contact numbers, opening hours, treatment focus etc. at a glance.

2.3.2. Expert videos

The app included short video-taped interviews with clinical psychologists and pediatricians answering frequent questions on child crying, sleeping, and feeding (e.g., “How can I support my child settling into sleep?”).

2.3.3. Diary function

To get to know the child's individual rhythm better, app users could document their child's crying, sleeping, and feeding times in a behavior diary. Diary entries could be downloaded as a PDF file or sent as an e-mail to facilitate exchange with other caregivers or therapists.

2.3.4. “Caring for yourself” (selfcare strategies for parents)

In the selfcare section, psychoeducational texts emphasized that the parents' own needs must be acknowledged and should be given space in everyday family life to support healthy parenting behaviors. Coping strategies for stressful situations as well as “tips and tricks” for activities and small time-outs in everyday life were provided in text format for single parenting (e.g., short breathing exercises) and joint parenting situations.

2.3.5. Chat forum

A chat forum set up in cooperation with “netmoms.de” served as a platform for sharing experiences with other affected families. After registering on the platform and creating a free profile, app users had access to a secured parent group.

2.3.6. Find support in your area

In this section, families could find relevant contact data for counseling centers, including contacts for emergency such as crisis telephones and online counseling. A total of 95 relevant addresses were listed including information about costs, registration procedure and focus of treatment, with a filter function for relevant contacts in the home city.

2.3.7. Other features (not specifically evaluated)

Additionally, parents of an child with crying problems shared their individual experiences in an audio-taped interview of about 20 min.

2.4. Recruitment and procedure

The study sample was recruited within the framework of a clinical RCT (Augustin et al., 2023), performed within a cry baby outpatient clinic in Southern Germany (Bavaria). In the clinical study, the effects of the use of the new developed app on parent and child outcomes were evaluated with a clinical sample, randomly allocated to an intervention and a waitlist control group. Therefore, parents were screened for their eligibility for study participation. The target group were German-speaking parents of children aged 0–24 months contacting the clinic for a first consultation due to child crying, sleeping and/or feeding problems. Interested parents were forwarded to the study team, who provided more detailed information about the study. Subsequently, after a verbal consent, study information, a declaration of consent and questionnaires were sent postally to the participants. After they returned the written consent and study documents (RCT t1), participants in the intervention group (n = 73) received access to the app immediately, using the app during their average waiting time until the first clinic appointment. Participants in the waitlist control group gained access to the app after the first clinic appointment (n = 63). Furthermore, 111 interested parents who were not included in the RCT, but were willing to evaluate the app, received app access besides the RCT participation. Following the RCT study design, participants in the intervention group evaluated the app use after their waiting time until their first appointment in the clinic (average 3 weeks), when they were asked to fill in an app evaluation questionnaire together with the RCT t2 outcome measurement. Accordingly, participants in the waitlist control group and other participants not included in the RCT were asked to fill in the app evaluation questionnaire 3 weeks after giving access to the app. Participants were allowed to use the app for as long as they wanted. Study participation was not associated with advantages or disadvantages in the regular clinic care.

2.5. Measures

2.5.1. Sociodemographic questionnaire

Parental age, participant's relation to the child, nationality, first language, educational qualifications, current employment situation, partnership status, child age and gender, siblings and information about the child's problems were assessed.

2.5.2. App evaluation questionnaire

The app was evaluated by a self-developed questionnaire using 28 items (Supplement Table S1), provided either paper-pencil or online-based via Sosci Survey (Leiner, 2019). App use duration was assessed via amount of days. App use frequency was assessed via categorial answers (daily, several times per week, once a week, less than once a week, app not used). Overall impression, usability, as well as impression about informational texts, expert videos, diary function, selfcare strategies, regional register of counseling centers, and the chat forum were quantitatively assessed by 5-point-Likert scale items “How did you like…” (from 1 = very much to 5 = not at all). Additionally, all of these items were followed by a qualitative open question “Please explain your answer/ suggestion for improvement”. Furthermore, reasons for not using the chat forum were assessed by categorial answer options: (a) not interested in exchange with other parents, b) too short usage time of the app, c) concerns about data protection, d) other reasons. Future functions were assessed by the item “how helpful would you find the following features for yourself and other parents” followed by multiple options, namely the possibility to a) search for contact points by radius search, b) share the app with their partner (partner profile), c) contact counseling centers by phone via direct call from the app, d) contact counseling centers directly from the app via email, e) store their data on a server to prevent data loss in case of device change or app deletion (login required), f) manage multiple child profiles in the app, and g) automatically filter counseling centers via GPS location. Also, the qualitative open-question item “Please tell us more suggestions for improving the app” assessed more general feedback and future functions.

2.6. Data analysis

Sample size was derived from recruitment for the RCT study (for details see Augustin et al., 2023). Quantitative data analyses were based on descriptive and inferential statistical methods using SPSS statistical software version: 28.0 (IBM Corp., 2021). Open-answer items were analysed using a qualitive inductive – deductive approach (Mayring, 2015; Kuckartz, 2018). First, a framework was built, and parents' answers were sorted by three research assistants into three categories for every specific app function (positive and negative feedback and suggestions for improvement), divided into feedback related to content vs. technical implementation (Supplement Table S2). Second, statements in each category were summarized into thematic subcategories by three research assistants. Third, statements occurring at least five times were recorded by an independent research assistant into the subcategories.

3. Results

3.1. Participant enrollment and characteristics

After a first screening by the outpatient clinic (N = 669) a total of n = 359 participants were assessed for eligibility by the study team. Of the 247 included participants, 137 returned the study questionnaires (see Fig. 3 for CONSORT participant flow chart). Demographics are reported in Table 1.

Fig. 3.

Participant Flow Chart.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (N = 137).

| Characteristics | n (%) | M(SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Parental age (years) | 33.41 (4.0) | |

| Participant's relation to child | ||

| Mother | 132 (96.4) | |

| Father | 5 (3.6) | |

| Academic qualification | ||

| Qualified for university entrance | 108 (78.8) | |

| Other/missing | 29 (21.2) | |

| Nationality | ||

| German | 122 (89.1) | |

| Other | 15 (10.9) | |

| First language | ||

| German | 121 (88.3) | |

| Other | 16 (11.7) | |

| Employment | ||

| Parental leave/currently not employed | 105 (76.6) | |

| Currently employed/apprenticeship | 28 (20.4) | |

| Other/missing | 4 (2.9) | |

| Single parent | 2 (1.5) | |

| Child age (months) | 9.42 (4.6) | |

| Child gender | ||

| Girl | 63 (46) | |

| Boy | 74 (54) | |

| Siblings | ||

| Yes | 36 (26.3) | |

| No | 101 (73.7) | |

| Child's symptom duration (months) | 6.80 (4.54) | |

| Reason for consultation | ||

| Sleeping problems | 64 (46.7) | |

| Feeding problems | 12 (8.8) | |

| Crying, whining | 6 (4.4) | |

| Combined problems | 46 (33.6) | |

| Other/missing | 9 (6.6) |

3.2. Evaluation outcomes

3.2.1. Frequency of app use

Participants had the app at their disposal for an average of 19.06 days (SD = 15.00, Mdn = 15, range = 1–90, percentiles: 25 % = 7, 50 % = 15, 75 % = 27). Most parents used the app at least once a week (once a week: n = 40, 29.20 %; several times a week: n = 37, 27.01 %; daily: n = 9, 6.57 %), whereas 43 participants (31.40 %) used the app less than once a week, seven participants (5.11 %) did not use the app and one person (0.73 %) did not state how often he/she had used the app. As reasons for not using the app, three participants stated technical problems with the app installation, one person stated to be too burdened and four participants did not use the app for unknown reasons (Fig. 2).

3.2.2. Overall usability and impression

Quantitatively, most participants rated overall impression and usability as good (Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptives of app-evaluation.

| Content | Evaluated by n (%a) | Mdn | M(SD) | Rangeb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall impression | 128 (98.5) | 2 | 2.54 (0.78) | 1–4 |

| Usability | 129 (99.2) | 2 | 2.33 (0.97) | 1–5 |

| Informational texts | 128 (98.5) | 2 | 2.04 (0.85) | 1–5 |

| Expert videos | 88 (67.7) | 2 | 1.81 (0.87) | 1–5 |

| Diary function | 85 (65.4) | 3 | 3.03 (1.27) | 1–5 |

| Selfcare strategies | 89 (68.5) | 2 | 2.46 (1.02) | 1–5 |

| Find support in your area | 84 (64.6) | 2 | 1.79 (0.70) | 1–4 |

| Chat forum | 38 (29.2) | 2 | 2.68 (1.28) | 1–5 |

Percentages refer to N = 130 participants who had used the app.

Items (“How did you like …”) were based on 5-point-Likert scales from 1 = very much to 5 = not at all.

Qualitatively, participants overall assessed the app as informative and appealing in terms of content, its conciseness and structure.

“A very good topic structure, everything is very easy to find.”

(Participant 102)

Yet, some app users criticized the lack of added value regarding the app's level of detail compared to other sources.

“Much of this can also be researched on the internet.”

(Participant 125)

Feedback on technical implementation varied. While some app users experienced the app as easy to handle and well structured, others reported bugs regarding a navigation tool or described difficulties related to graphical design or structure.

“User friendly, easy to handle.”

(Participant 22)

“Back button of the phone was not usable.”

(Participant 2)

3.2.3. Specific app functions

3.2.3.1. Informational texts

Quantitatively, informational texts were rated as good (Table 2). Qualitatively, the contents were described as informative and interesting, while concise with a good level of detail and text volume and a clear arrangement.

“Very useful and informative and well written. No suggestion for improvement.”

(Participant 38)

“The subdivision into short and long texts is useful.”

(Participant 48)

Other users rated the text extent as too long and criticized a lack of added value since contents were already well-known.

“Due to the text extent a little stodgy.”

(Participant 198)

“I already knew the content from books.”

(Participant 43)

3.2.3.2. Expert videos

Expert videos were quantitatively rated as good (Table 2). Qualitatively, app users liked the integration of expert videos as an additional way to present information:

“[…] the information transmission appears even more competent and personal. It is great to have united the different sources of information in a single app, using this, there is no need to use google permanently.”

(Participant 108)

The content was labelled to be informative and interesting, as well as helpful, concise and appealing.

“Informative, easy to understand, good length to watch in between.”

(Participant 22)

3.2.3.3. Diary function

The diary function was quantitatively rated as mediocre (Table 2). Qualitatively, participants liked the idea of a diary function and rated it as helpful.

“I like the fact that the app generally gives you the option of a diary and also the option to convert it into a PDF.”

(Participant 169)

However, the implementation was described as not precise enough and uninformative.

“To enable an analysis by experts, more extras would need to be added.”

(Participant 19)

The design, arrangement, and functionality such as the navigation tool were reported to need usability improvements.

“Start and stop button instead of time and duration which is inconvenient.”

(Participant 196)

3.2.3.4. Selfcare strategies

Quantitatively, the selfcare strategies were rated as good (Table 2). Qualitatively, the feedbacks regarding the selfcare strategies diverged widely. App users evaluated the function to be useful and supportive.

“Good propositions, it reminds you to take care of oneself.”

(Participant 204)

Others rated the strategies as unfeasible, not helpful, or well-known and therefore, declared a lack of added value.

“Often difficult to realise as the child does not leave one alone.”

(Participant 63)

3.2.3.5. Find support in your area

The regional register of counseling centers was quantitatively rated as good (Table 2). Users qualitatively described this function as helpful, convenient, concise as well as informative and interesting.

“Good for emergency situations to have all numbers at hand.”

(Participant 36)

“Helpful. Information can be found on Google, but here everything is at a glance.”

(Participant 114)

3.2.3.6. Chat forum

The chat forum was quantitatively rated as good (Table 2). In qualitative feedbacks, the idea of a platform was perceived as useful, but a lack of interaction within the chat forum was criticized.

“It is a very good idea and could be helpful for many parents but there are no posts in the forum yet.”

(Participant 102)

Some users disliked the need to register at an external platform and hence suggested the integration into the app itself.

“It would be nicer to use an internal chat forum without registration into other online portals.”

(Participant 192)

One hundred and seven participants gave reasons why they did not use the chat forum. Most parents stated that usage time of the app was too short (32/107) whereas 13 parents stated that they were not interested in exchanging with other parents, and three participants had concerns about data protection. Moreover, 35 participants stated other reasons and 24 parents stated a combination of reasons.

3.2.4. Future functionality and suggested improvements

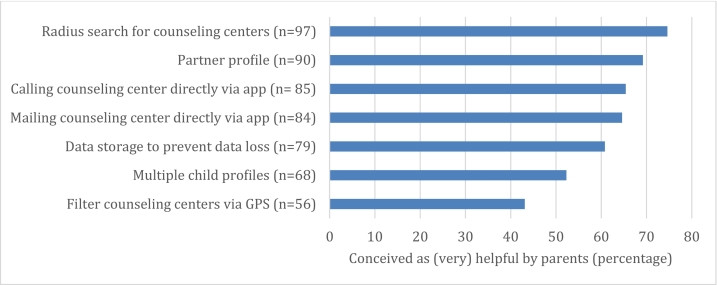

We proposed several functionalities, not yet implemented in the app, to parents, to rate them for desirability (see Fig. 4). The most highly rated functionality was a radius search for counseling centers, followed by the option to share the app via a partner profile.

Fig. 4.

Percentage of parents rating possible future functions as very helpful/ helpful (N = 130).

In open feedback questions, participants suggested technical improvements in terms of bug fixes, an improvement of the navigation tools and graphical design, e.g., a clearer arrangement.

“Compatibility with the dark mode of Iphone.”

(Participant 129)

While some users suggested shorter text passages, others asked for more detailed information with specific advice. Moreover, users proposed a higher level of interactive use.

“I would prefer more experience reports from parents, more interaction.”

(Participant 169)

With regard to the diary function, participants wished for the possibility to enter more details into the diary, which should then be displayed in graphs, such as daily and progress charts. Additionally, users proposed a link on the start page or home screen to guarantee a fast usage as well as a start-stop-function for data entry.

“A visualization of the day or over several days would be great to identify patterns or to be able to compare them easily.”

(Participant 198)

“As I use the diary function several times a day, I would like this to be the start page when I open the app.”

(Participant 38)

“Diary function would be better with a timer similar to a stopwatch.”

(Participant 83)

Regarding the chat forum, participants suggested the implementation of the forum within the app.

“Make registration and access possible directly within the app.”

(Participant 234)

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal findings

This study aimed to evaluate a new psychoeducational app for parents of children with crying, sleeping, and feeding problems in regards to overall impression and usability, usefulness of specific functions and suggestions for future improvements. The majority of the parents used the app regularly and their overall impression and usability ratings were good. Of the specific app functions, participants rated the informational texts, expert videos and regional register of counseling centers most positively, whereas the diary function and chat forum required improvements. In terms of future functions, families suggested improving the handling to enhance usability and wished for an option to share the app via a partner profile.

In detail, our results showed that most participants rated usability as good and the majority used the app at least once a week which is comparable to usage rates of other parenting apps (e.g., Dienelt et al., 2020). Usability is one of the most important factors in developing efficient apps (Sardi et al., 2020). As usability, including effort expectancy and facilitation conditions (Venkatesh et al., 2003) has a high impact on app usage behavior, an easy app-handling has the potential to reinforce adherence to the app itself and to the system of professional support as a whole (Sardi et al., 2020).

Regarding psychoeducational content, it is crucial to provide basic information on topics such as infant feeding or routine practices and tips to new parents, however, many postnatal care apps lack informative content (Sardi et al., 2020). Our app has shown to increase parental knowledge about child crying, sleeping, and feeding (Augustin et al., 2023), which is consistent with the positive feedbacks about informational texts and expert videos reported in this study. Parents liked that the information was presented in a varied way which is in line with findings addressing advantages of mixed cues/ video presentation in the psychoeducational context (McConkey, 1993; Wilson et al., 2012; Nussey et al., 2013).

The diary function was considered to be useful in theory, but app users criticized shortcomings in the implementation (such as an inconvenient data entry). Allowing parents to create a sleep diary has been a neglected feature in postnatal apps up to now (Sardi et al., 2020). Using trackers can help parents to better understand child behavior patterns in order to react adequately and to implement routines, which in turn gives parents a measure of control (Dienelt et al., 2020). However, they also bear the risk of being perceived as time-consuming and overwhelming (Demirci and Bogen, 2017). It is conceivable that this function was too inconvenient and time-consuming for the parents in our study, which might be one possible explanation why about 35 % of parents did not evaluate this function. To improve the handling of this function, we aim to improve the navigation tool and input options, e.g. by implementing a start-stop button.

The selfcare strategies were rated as being supportive, but some participants stated that they were unfeasible or not helpful. This function was not rated by 32 % of the sample, which might indicate that several parents did not read and/or use these proposed strategies. As parents of children with crying, sleeping, or feeding problems often experience high levels of stress, self-care strategies can be helpful components of interventions for this target group (Schlarb and Brandhorst, 2012; St. James-Roberts et al., 2019). However, there are inconsistent findings about which interventions are most effective for reducing parental stress in the first two years (Matvienko-Sikar et al., 2021). Further research will be needed to determine which exercises are perceived as most helpful for parents of children with crying, sleeping, or feeding problems.

The regional register of counseling centers was rated throughout as useful. Missing evaluation data rates of about 35 % in our study could be explained by the fact that participants were recruited from a setting where participants had already been connected to a face-to-face support (in the clinic), thus the need to search for another counseling center might have been low for this clientele. However, parents stated that they liked to have all important information at hand. Not only our clientele, but many parents prefer to combine face-to-face support with app use (Bailey et al., 2022). On the other hand, in a study by Garratt et al., 2019, some parents of excessively crying children reported that the support offered did not fully meet their needs, which might be frustrating for parents. Providing a register of counseling centers including information about the treatment focus might help parents to find a suitable service for them. The handling could be improved by e.g. providing a radius search.

Regarding the parent chat forum, many participants liked the idea of social exchange which is in line with earlier research (Baker and Yang, 2018) that demonstrated that 89 % of new mothers used social media to communicate with other mothers. However, in our study, the chat forum was rarely used (107 participants stated reasons why they had not used the chat forum), mainly due to a short app usage time within the study framework. Also, as not all participants took part in the study at the same time, only a small number of participants used the chat forum simultaneously and a lack of interaction in the forum was noticeable. Furthermore, as the need to register on an external platform was criticized, an in-app chat forum might motivate parents more to use it. In addition, as reported by some users, face-to face contact might be preferred to online exchange.

Besides suggestions for improving the handling of the app, many participants liked the idea of implementing a partner profile as a possible future function. Including both partners in psychoeducational interventions might be a promising prevention factor for parental mental health (Midmer et al., 1995; Rowe and Fisher, 2010).

4.2. Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first app targeting child crying, sleeping, and feeding problems as commonly co-occuring symptom patterns. The app brings various benefits as it entails evidence-based content, takes into account the complexity of co-occuring symptoms, combines the benefits of psychoeducational and interactive input, and addresses both child and parental outcomes. It is a new and promising low-threshold approach which can contribute to a better understanding of the symptoms and to reducing parenting stress (Augustin et al., 2023) and therefore has the potential to serve as a secondary preventive tool. A parallel mixed methods approach entails the possibility to answer complex research questions including exploratory questions, to provide more valid inferences and to produce a more complete picture of the investigated subject (Lund, 2012). Consequently, relevant implications for a rework and adaptation of the app can be derived from the study results.

However, our results must be interpreted against the background of some limitations: First, our sample was retrieved from one specific clinical setting with a limited number of participants, including predominantly highly educated participants of German nationality with a partner. Caution should be exercised regarding the generalization of our results. However, these sample characteristics are quite comparable with the clinical clientele in this cry baby outpatient clinic (Papoušek, 2004) and several other studies on child crying, sleeping, and feeding problems in which high rates of higher-educated families in stable partnerships were reported (Richter and Reck, 2013; Winsper and Wolke, 2014). Additionally, as only 5 fathers compared to 132 mothers had participated in the study, it is important to note that the study results may not generalize to the needs of new fathers. Future research could address this by recruiting equal numbers of fathers and mothers to understand whether there are any differences between mothers and fathers in terms of their app usage, preferences and needs. Moreover, the average duration of disposal until evaluation was 19 days and there were large differences between the parents in terms of the usage periods because the recruitment was linked to the clinic appointments. Thus, it is reasonable that some participants might not have had enough time to try every app function in-depth, which might also explain a number of missing values in some of the app functions. It is important to conduct a further study where parents are instructed to use the app for a longer duration to obtain elaborated feedback also regarding (motivation for) long-term use. Furthermore, the app is still limited to German-speaking parents. In order to address all families' needs, it is necessary to provide solutions to offer mhealth apps in different languages (Ouhbi et al., 2017; Sardi et al., 2020).

It is important to highlight that part of the study took place during the Covid-19 pandemic. During this period, there was a sharp increase in the use of digital applications given the convenience and lack of access to health care. Although we can not draw on studies comparing the need for app-based interventions for parents of children with crying, sleeping, and feeding problems before and after the pandemic, it is conceivable that our app may have provided a good outlet for affected parents due to the limited access to face-to-face support during that stressful period.

5. Conclusions

The regular use and positive ratings of overall impression and usability, and usefulness of specific functions of the psychoeducational app on child crying, sleeping, and feeding problems, are important prerequisites for the newly developed offer's acceptance and effective use as psychoeducational guidance. When developing eHealth guidance for this target group, information should be presented as clearly as possible, preferably using diverse technological functionalities, in an easy-to-use format.

Our app is intended to be made available free of charge as a low-threshold secondary preventive service to reduce parenting stress, to support preventing from crisis situations, to reduce barriers to seeking professional help and to complement professional counseling. Pediatricians will play an important role in disseminating the app offer, but at the current stage, we want to refrain from a prescription requirement in order to provide low-threshold access for all families.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: AF, MLD, MA, DW, LDB, AB, VM and MZ developed the app used in the trial. Beyond that, the authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants in the study for their time and effort. Thanks go out to the outpatient clinic, with special thanks to Dominika Hess, for their recruitment support. The authors give thanks to the project staff Katharina Richter, Sinja Schwarzwälder, Catherine Buechel, Lena Wagner, Kristina Scherer, Tina Benzinger and Selina Onoh for their contribution to the study.

MA, AF, MLD, DW and VM conceptualized and designed the study. MA and AF coordinated the data collection. MA, AF, ASW and LDB contributed to the analyses and interpretation of the data. MA, AF and ASW wrote the manuscript. MLD, VM, DW, LDB, AB and MZ reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. AF, MLD, MA, DW, LDB, AB, VM and MZ developed the app used in the trial. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. The study was funded by the initiative “Gesund.Leben.Bayern” of the Bavarian Ministry of Health (grant number: LP00261).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2023.100700.

Contributor Information

Michaela Augustin, Email: michaela.augustin@tum.de.

Anne Sophie Wenzel, Email: annesophie.wenzel@tum.de.

Maria Licata-Dandel, Email: maria.licata-dandel@tum.de.

Linda D. Breeman, Email: l.d.breeman@fsw.leidenuniv.nl.

Ayten Bilgin, Email: a.bilgin@essex.ac.uk.

Dieter Wolke, Email: d.wolke@warwick.ac.uk.

Margret Ziegler, Email: margret.ziegler@kbo.de.

Volker Mall, Email: volker.mall@tum.de.

Anna Friedmann, Email: anna.friedmann@tum.de.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary tables

References

- Ammaniti M., Lucarelli L., Cimino S., D’Olimpio F., Chatoor I. Feeding disorders of infancy: a longitudinal study to middle childhood. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2012;45:272–280. doi: 10.1002/eat.20925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustin M., Licata-Dandel M., Breeman L.D., Harrer M., Bilgin A., Wolke D., Mall V., Ziegler M., Ebert D.D., Friedmann A. Effects of a mobile-based intervention for parents of children with crying, sleeping, and feeding problems: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2023;11 doi: 10.2196/41804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey E., Nightingale S., Thomas N., Coleby D., Deave T., Goodenough T., Ginja S., Lingam R., Kendall S., Day C., Coad J. First-time mothers’ understanding and use of a pregnancy and parenting mobile app (the baby buddy app): qualitative study using appreciative inquiry. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2022;10 doi: 10.2196/32757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker B., Yang I. Social media as social support in pregnancy and the postpartum. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. Off. J. Swed. Assoc. Midwives. 2018;17:31–34. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow K.M., Minns R.A. Annual incidence of shaken impact syndrome in young children. Lancet. 2000;356:1571–1572. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03130-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr R.G., Trent R.B., Cross J. Age-related incidence curve of hospitalized shaken baby syndrome cases: convergent evidence for crying as a trigger to shaking. Child Abuse Negl. 2006;30:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäuml J.G., Pitschel-Walz G. In: Psychoedukation bei schizophrenen Erkrankungen. Konsensuspapier der Arbeitsgruppe “Psychoedukation bei schizophrenen Erkrankungen”. Schattauer, Stuttgart. Bäuml J.G., Pitschel-Walz G., editors. 2003. Psychoedukative Informationsvermittlung: Pflicht und Kür; pp. 101–123. [Google Scholar]

- Bäuml J.G., Pitschel-Walz G. Psychoedukation, quo vadis? Psychotherapeut. 2012;57:289–290. [Google Scholar]

- Bäuml J.G., Baumann N., Avram M., Mulej Bratec S., Breeman L.D., Berndt M., Bilgin A., Jaekel J., Wolke D., Sorg C. The default mode network mediates the impact of infant regulatory problems on adult avoidant personality traits. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging. 2019;4:333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilgin A., Wolke D. Regulatory problems in very preterm and full-term infants over the first 18 months. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2016;37:298–305. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilgin A., Wolke D. Infant crying problems and symptoms of sleeping problems predict attachment disorganization at 18 months. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2020;22:367–391. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2019.1618882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilgin A., Baumann N., Jaekel J., Breeman L.D., Bartmann P., Bäuml J.G., Avram M., Sorg C., Wolke D. Early crying, sleeping, and feeding problems and trajectories of attention problems from childhood to adulthood. Child Dev. 2020;91:e77–e91. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan M.A., Evans Y., Morishita C., Midamba N., Moreno M. Parental perceptions of the internet and social media as a source of pediatric health information. Acad. Pediatr. 2020;20:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2019.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K.L., Leung W.C., Tiwari A., Or K.L., Ip P. Using smartphone-based psychoeducation to reduce postnatal depression among first-time mothers: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7 doi: 10.2196/12794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook F., Mensah F.K., Bayer J.K., Hiscock H. Prevalence, comorbidity and factors associated with sleeping, crying and feeding problems at 1 month of age: a community-based survey. J. Paediatr. Child Health. 2019;55:644–651. doi: 10.1111/jpc.14262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig P., Dieppe P., Macintyre S., Michie S., Nazareth I., Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2008;337 doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J.W., Plano Clark V.L. 2nd ed. SAGE; Los Angeles: 2011. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. 457 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Daley D.C., Bowler K., Cahalane H. Approaches to patient and family education with affective disorders. Patient Educ. Couns. 1992;19:163–174. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(92)90195-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirci J.R., Bogen D.L. An ecological momentary assessment of primiparous women’s breastfeeding behavior and problems from birth to 8 weeks. J. Hum. Lact. Off. J. Int. Lact. Consult. Assoc. 2017;33:285–295. doi: 10.1177/0890334417695206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienelt K., Moores C.J., Miller J., Mehta K. An investigation into the use of infant feeding tracker apps by breastfeeding mothers. Health Informatics J. 2020;26:1672–1683. doi: 10.1177/1460458219888402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix Burda Stiftung . 2020. Gesundheits-Apps so beliebt wie nie. [Google Scholar]

- Garratt R., Bamber D., Powell C., Long J., Brown J., Turney N., Chessman J., Dyson S., James-Roberts I.S. Parents’ experiences of having an excessively crying baby and implications for support services. J. Health Visiting. 2019;7:132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Haschke C., Grote-Westrick M., Schwenk U. 2018. Gesundheitsinfos. Wer suchet, der findet – Patienten mit Dr. Google zufrieden. Spotlight Gesundheit. [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield A.B. Issues in psychoeducation for families of the mentally ill. Int. J. Ment. Health. 1988;17:48–64. [Google Scholar]

- Heh S.-S. Relationship between social support and postnatal depression. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2003;19:491–496. doi: 10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70496-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmi M.H., Wolke D., Schneider S. Associations between problems with crying, sleeping and/or feeding in infancy and long-term behavioural outcomes in childhood: a meta-analysis. Arch. Dis. Child. 2011;96:622–629. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.191312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiscock H., Ng O., Crossley L., Chow J., Rausa V., Hearps S. Sleep well be well: pilot of a digital intervention to improve child behavioural sleep problems. J. Paediatr. Child Health. 2021;57:33–40. doi: 10.1111/jpc.15106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp . IBM Corp; Armonk, NY: 2021. IBM SPSS Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson D.E. Types and timing of social support. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1986;27:250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuckartz U. 4th ed. Beltz Juventa; Weinheim, Basel: 2018. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Methoden, Praxis, Comupterunterstützung. [Google Scholar]

- Lang A.V., Simhandl C. Psychoedukation – zusammen weniger allein. Psychopraxis. 2009;12:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Larkin F., Oostenbroek J., Lee Y., Hayward E., Meins E. Proof of concept of a smartphone app to support delivery of an intervention to facilitate mothers’ mind-mindedness. PloS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leichman E.S., Gould R.A., Williamson A.A., Walters R.M., Mindell J.A. Effectiveness of an mHealth intervention for infant sleep disturbances. Behav. Ther. 2020;51:548–558. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2019.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiner D.J. 2019. SoSci Survey (Version 3.1.06) [Google Scholar]

- Linardon J., Cuijpers P., Carlbring P., Messer M., Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M. The efficacy of app-supported smartphone interventions for mental health problems: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry Off. J. World Psychiatric Association. 2019;18:325–336. doi: 10.1002/wps.20673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund T. Combining qualitative and quantitative approaches: some arguments for mixed methods research. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2012;56:155–165. [Google Scholar]

- Matvienko-Sikar K., Flannery C., Redsell S., Hayes C., Kearney P.M., Huizink A. Effects of interventions for women and their partners to reduce or prevent stress and anxiety: a systematic review. Women Birth J. Aust. Coll. Midwives. 2021;34:e97–e117. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer R.E. The promise of multimedia learning: using the same instructional design methods across different media. Learn. Instr. 2003;13:125–139. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring P. 12th ed. Beltz; Weinheim: 2015. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Grundlagen und Techniken. [Google Scholar]

- McConkey R. Video training packages for parent education. Viewfinder. 1993;2:34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Midmer D., Wilson L., Cummings S. A randomized, controlled trial of the influence of prenatal parenting education on postpartum anxiety and marital adjustment. Fam. Med. 1995;27:200–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy P.W., Chesson A.L., Walker L., Arnold C.L., Chesson L.M. Comparing the effectiveness of video and written material for improving knowledge among sleep disorders clinic patients with limited literacy skills*. South. Med. J. 2000;93:297–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussey C., Pistrang N., Murphy T. How does psychoeducation help? A review of the effects of providing information about Tourette syndrome and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Child Care Health Dev. 2013;39:617–627. doi: 10.1111/cch.12039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouhbi S., Fernández-Alemán J.L., Carrillo-de-Gea J.M., Toval A., Idri A. E-health internationalization requirements for audit purposes. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2017;144:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2017.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papoušek M. In: Regulationsstörungen der frühen Kindheit. Papoušek M., Schieche M., Wurmser H., editors. Frühe Risiken und Hilfen im Entwicklungskontext der Eltern-Kind-Beziehungen; Huber, Bern: 2004. Regulationsstörungen der frühen Kindheit: Klinische Evidenz für ein neues diagnostisches Konzept; pp. 77–110. [Google Scholar]

- Petzoldt J., Wittchen H.-U., Einsle F., Martini J. Maternal anxiety versus depressive disorders: specific relations to infants’ crying, feeding and sleeping problems. Child Care Health Dev. 2016;42:231–245. doi: 10.1111/cch.12292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter N., Reck C. Positive maternal interaction behavior moderates the relation between maternal anxiety and infant regulatory problems. Infant Behav. Dev. 2013;36:498–506. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts L.R., Boostrom G.G., Dehom S.O., Neece C.L. Self-reported parenting stress and cortisol awakening response following mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention for parents of children with developmental delays: a pilot study. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2020;22:217–225. doi: 10.1177/1099800419890125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe H.J., Fisher J.R.W. Development of a universal psycho-educational intervention to prevent common postpartum mental disorders in primiparous women: a multiple method approach. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:499. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardi L., Idri A., Redman L.M., Alami H., Bezad R., Fernández-Alemán J.L. Mobile health applications for postnatal care: review and analysis of functionalities and technical features. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2020;184 doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2019.105114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlarb A.A., Brandhorst I. Mini-KiSS online: an internet-based intervention program for parents of young children with sleep problems – influence on parental behavior and children’s sleep. Nat. Sci. Sleep. 2012;4:41–52. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S28337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey S., Lau Y., Dennis C.-L., Chan Y.S., Tam W.W.S., Chan Y.H. A randomized-controlled trial to examine the effectiveness of the ‘Home-but not Alone’ mobile-health application educational programme on parental outcomes. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017;73:2103–2117. doi: 10.1111/jan.13293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon S.L., Kaar J.L., Talker I., Reich J. Evidence-based behavioral strategies in smartphone apps for children’s sleep: content analysis. JMIR Pediatr. Parenting. 2022;5 doi: 10.2196/32129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. James-Roberts I., Garratt R., Powell C., Bamber D., Long J., Brown J., Morris S., Dyson S., Morris T., Bhupendra Jaicim N. A support package for parents of excessively crying infants: development and feasibility study. Health Technol. Assess. (Winchester, England) 2019;23:1–144. doi: 10.3310/hta23560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stifter C.A., Bono M.A. The effect of infant colic on maternal self-perceptions and mother-infant attachment. Child Care Health Dev. 1998;24:339–351. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2002.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh V., Morris M.G., Davis G.B., Davis F.D. User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003;27:425–478. [Google Scholar]

- Vik T., Grote V., Escribano J., Socha J., Verduci E., Fritsch M., Carlier C., von Kries R., Koletzko B., European Childhood Obesity Trial Study Group Infantile colic, prolonged crying and maternal postnatal depression. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98:1344–1348. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson E.A., Makoul G., Bojarski E.A., Bailey S.C., Waite K.R., Rapp D.N., Baker D.W., Wolf M.S. Comparative analysis of print and multimedia health materials: a review of the literature. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012;89:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winsper C., Wolke D. Infant and toddler crying, sleeping and feeding problems and trajectories of dysregulated behavior across childhood. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2014;42:831–843. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9813-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolke D., Söhne B., Riegel K., Ohrt B., Osterlund K. An epidemiologic longitudinal study of sleeping problems and feeding experience of preterm and term children in southern Finland: comparison with a southern German population sample. J. Pediatr. 1998;133:224–231. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolke D., Baumann N., Jaekel J., Pyhälä R., Heinonen K., Räikkönen K., Sorg C., Bilgin A. The association of early regulatory problems with behavioral problems and cognitive functioning in adulthood: two cohorts in two countries. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2023;64(6):876–885. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary tables