Abstract

Abstract

Bacteria belonging to the genus Algoriphagus have been isolated from various sources, such as Antarctic sea ice, seawater, and sediment, and some strains are known to produce orange to red pigments. However, the pigment composition and biosynthetic genes have not been fully elucidated. A new red-pigmented Algoriphagus sp. strain, oki45, was isolated from the surface of seaweed collected from Senaga-Jima Island, Okinawa, Japan. Genome comparison revealed oki45’s average nucleotide identity of less than 95% to its closely related species, Algoriphagus confluentis NBRC 111222 T and Algoriphagus taiwanensis JCM 19755 T. Comprehensive chemical analyses of oki45’s pigments, including 1H and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance and circular dichroism spectroscopy, revealed that the pigments were mixtures of monocyclic carotenoids, (3S)-flexixanthin ((3S)-3,1′-dihydroxy-3′,4′-didehydro-1′,2′-dihydro-β,ψ-caroten-4-one) and (2R,3S)-2-hydroxyflexixanthin ((2R,3S)-2,3,1′-trihydroxy-3′,4′-didehydro-1′,2′-dihydro-β,ψ-caroten-4-one); in particular, the latter compound was new and not previously reported. Both monocyclic carotenoids were also found in A. confluentis NBRC 111222 T and A. taiwanensis JCM 19755 T. Further genome comparisons of carotenoid biosynthetic genes revealed the presence of eight genes (crtE, crtB, crtI, cruF, crtD, crtYcd, crtW, and crtZ) for flexixanthin biosynthesis. In addition, a crtG homolog gene encoding 2,2ʹ-β-hydroxylase was found in the genome of the strains oki45, A. confluentis NBRC 111222 T, and A. taiwanensis JCM 19755 T, suggesting that the gene is involved in 2-hydroxyflexixanthin synthesis via 2-hydroxylation of flexixanthin. These findings expand our knowledge of monocyclic carotenoid biosynthesis in Algoriphagus bacteria.

Key points

• Algoriphagus sp. strain oki45 was isolated from seaweed collected in Okinawa, Japan.

• A novel monocyclic carotenoid 2-hydroxyflexixanthin was identified from strain oki45.

• Nine genes for 2-hydroxyflexixanthin biosynthesis were found in strain oki45 genome.

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00253-023-12995-2.

Keywords: Algoriphagus; Monocyclic carotenoids; Flexixanthin; 2-Hydroxyflexixanthin; Carotenoid biosynthetic genes; 2,2ʹ-β-Hydroxylase

Introduction

Carotenoids are red-to-yellow lipophilic pigments biosynthesized by plants and microorganisms, and > 1000 types have been identified (Yabuzaki 2017). The primary structure of carotenoids is formed by conjugated polyene chains and terminal groups. Cyclization, a terminal-group modification, contributes to the structural diversity of carotenoids. Lycopene, a noncyclic carotenoid, is converted to the dicyclic carotenoid β-carotene via cyclization of both terminal groups, which is abundantly found in various organisms, including plants. Conversely, some marine bacteria generate monocyclic carotenoids, such as myxol, via the cyclization of a single terminal group (Yokoyama and Miki 1995; Takatani et al. 2014, 2015).

Carotenoids exhibit numerous physiological functions, such as improving membrane stability, protecting against oxidative stress, and serving as accessory pigments during photosynthesis (Swapnil et al. 2021). Recent research has focused on the health benefits of carotenoids (Elvira-Torales et al. 2019). Deinoxanthin, a monocyclic carotenoid produced by extremophile microbes, such as Deinococcus radiodurans, exhibits strong scavenging activity against reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as hydrogen peroxide and singlet oxygen (Tian et al. 2007). Compared to the dicyclic carotenoids zeaxanthin and β-carotene, myxol and saproxanthin, other monocyclic carotenoids produced by marine bacteria, exhibit greater antioxidative and neuroprotective effects (Shindo et al. 2007). These findings indicate that the monocyclic structure of carotenoids exhibits various biological activities, including activities that provide health benefits. However, few monocyclic carotenoids have been identified, and thus, their biological activities are poorly understood.

Misawa et al. (1995) demonstrated that desired carotenoids can be obtained by expressing several biosynthetic genes isolated from marine bacteria in heterologous hosts, such as Escherichia coli, which should lead to the stable production of beneficial carotenoids and the generation of naturally rare carotenoids. Several unique genes involved in the biosynthesis of myxol, a representative monocyclic carotenoid, have been elucidated in marine bacteria; these genes include hydroxylase, desaturase, and lycopene cyclase (Rählert et al. 2009; Teramoto et al. 2003; Teramoto et al. 2004). However, only a few monocyclic carotenoid biosynthetic genes have been sequenced and functionally identified, and little is known about the monocyclic carotenoid biosynthesis system. Therefore, obtaining further knowledge about monocyclic carotenoid-producing bacteria and their carotenoid biosynthetic genes is important for future applications of monocyclic carotenoids.

In this study, we searched for marine bacteria that produce monocyclic carotenoids, and Algoriphagus sp. strain oki45 was isolated from the surface of unidentified seaweed collected in Okinawa, Japan. Structural analysis revealed that the strain oki45 produced monocyclic carotenoids flexixanthin and its hydroxylated derivative, which is a new compound. Furthermore, whole genome analysis of the strain oki45 and two related species found that several genes may be involved in the biosynthesis of those monocyclic carotenoids.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains

Unidentified seaweeds collected in 2014 from Senaga-Jima Island (Okinawa, Japan) were soaked in artificial seawater and plated at 25 °C on Marine Agar 2216 (Difco). After several days of incubation, red colonies were selected and plated on fresh Marine Agar 2216. This process was repeated until only a single colony remained. The strain oki45 was deposited at the RIKEN BioResource Center, Japan Collection of Microorganisms (Tsukuba, Japan) under JCM 19877. A. confluentis NBRC 111222 T (Park et al. 2016) and A. taiwanensis JCM 19755 T (Shahina et al. 2014) were used for species identification and genome comparison. These strains were also cultured using Marine Agar 2216 at 25 °C.

Carotenoid preparation

The strain oki45 was incubated for 1 week in 300 mL Marine Broth 2216 (Difco) in 500-mL Sakaguchi flasks at 140 rpm and 25 °C on a rotary shaker. The cell pellet was collected by centrifugation at 8000 rpm, and then the total lipid was extracted via the Folch method (Folch et al. 1957). The total lipid was separated on a preparative thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plate with silica gel 60 (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) and n-hexane/ethyl acetate (40:60, v/v). Flexixanthin and 2-hydroxyflexixanthin, Rf 0.53 and 0.31, were scraped from silica gel and then eluted with acetone. Then, each carotenoid was purified using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with a Develosil ODS column (250 × 4.6 mm; Nomura Chemical Co., Inc., Aichi, Japan), eluting with methanol/acetonitrile/ethyl acetate (50:20:30, v/v/v) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Carotenoids were detected using a UV–Vis detector (Hitachi L-2400) at 470 nm.

Spectroscopy

Absorption spectra were obtained using an HPLC LC-2050C 3D system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a Mightysil Si 60 column (250 × 4.6 mm; Kanto Chemical Co., Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The column temperature and detection wavelength were set to 30 °C and 470 nm, respectively. The mobile phase comprised n-hexane/acetone (70:30, v/v) at a 1.0-mL/min flow rate. 1H and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were acquired in CDCl3 using a UNITY INOVA-500 (Varian, USA) system and tetramethylsilane as an internal standard. The peak assignments of the homo and hetero two-dimensional NMR spectra were determined by comparing the data to those previously reported. The positive ion electrospray ionization (ESI)-mass spectrometry (MS) spectra data were obtained using an Acquity LC Xevo G2-S Q time-of-flight (TOF) MS spectrometer (Waters, USA). The ESI TOF MS spectra were acquired by scanning from m/z 100 to 1500 with a capillary voltage of 3.2 kV, a cone voltage of 40 eV, and a source temperature of 120 °C. Nitrogen was used as a nebulizing gas at a flow rate of 30 L/h. MS/MS spectra were measured using a quadrupole-TOF MS/MS instrument with argon and 30 V collision energy as the collision gas. UV–Vis spectra were recorded using a Hitachi U-2001 spectrometer (Hitachi Filed Navigator). Circular dichroism (CD) spectra data were obtained using a J-500C and J-1500 spectropolarimeter (Jasco, Tokyo, Japan) in ether at room temperature.

Genome sequencing and downstream analyses

Genomic DNAs of strain oki45, A. confluentis NBRC 111222 T, and A. taiwanensis JCM 19755 T were extracted and purified using the NucleoSpin Tissue kit (MACHEREY–NAGEL, Düren, Germany). Genome sequences were obtained using a MiSeq sequencer (Illumina, California, USA), and assembly was performed using Platanus B (Kajitani et al. 2014). The genome was further annotated using Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology (RAST) (Aziz et al. 2008). The genome data were deposited in DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession numbers BTPC01000001 to BTPC01000040, BTPD01000001 to BTPD01000050, and BTPE01000001 to BTPE01000051 for strains oki45, A. confluentis NBRC 111222 T, and A. taiwanensis JCM 19755 T, respectively.

Molecular phylogenic analysis

BLASTn (Mount 2007) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) site (Sayers et al. 2021) was used to search for and retrieve nucleotide sequences similar to the 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequence of strain oki45 from the nr database. The 16S rRNA gene nucleotide sequences of all Algoriphagus-type strains were retrieved from the GenBank/ENA/DDBJ database. The nucleotide sequence of the 16S rRNA gene of the strain oki45 was retrieved from the newly sequenced genome. The molecular phylogenetic tree depicted in Fig. 1 was reconstructed via the neighbor-joining method (Saitou and Nei 1987) after the nucleotide sequences were aligned using the MEGA version 7 program (Kumar et al. 2016). Maximum-likelihood and maximum-parsimony analyses were performed using MEGA7.

Fig. 1.

The molecular phylogenic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences of oki45 and Algoriphagus sp. This figure combines the results of three analyses, i.e., neighbor-joining, maximum-parsimony, and maximum-likelihood. The topology shown was obtained via neighbor-joining, and the percentage values are the results of a bootstrap analysis using 100 replications. Only bootstrap values > 50% are shown at branching points. Filled circles indicate the corresponding nodes, which were also recovered by maximum-likelihood and maximum-parsimony analyses

Genome taxonomy

Average nucleotide identity (ANI) against the strain oki45 genome was calculated using OrthoANI (Lee et al. 2016). The Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC2) (Meier-Kolthoff et al. 2013) was used to calculate the in silico DDH value.

Prediction of carotenoid biosynthetic genes

Sequence homology searches based on amino acid sequences were conducted to identify the carotenoid biosynthesis genes. The genes used for carotenoid biosynthesis were searched with reference to the biosynthetic system estimated by Tao et al. (2006). Genome sequences of known carotenoid biosynthetic genes were obtained from NCBI, and homology searches were performed using known carotenoid biosynthesis-related gene sequences on in silico MolecularCloning (IMC) (In silico Biology, Yokohama, Japan). We also used the Expert Protein Analysis System (ExPASy) (Gasteiger et al. 2003), BLAST, and Pfam (Finn et al. 2016) to estimate gene regions associated with protein classification and gene function. The NCBI Reference Sequence Database (RefSeq) (O’Leary et al. 2016) was used to determine the extent to which Algoriphagus sp. conserved 2-hydroxyflexixanthin biosynthesis genes.

Results

16S rRNA gene phylogeny

The strain oki45 isolated from the surface of an unidentified seaweed formed a red water-insoluble-pigmented colony on Marine Agar 2216. A molecular phylogenetic analysis based on the 16S rRNA gene nucleotide sequence revealed that strain oki45 belonged to the genus Algoriphagus and shared 99.1% sequence similarity with A. confluentis NBRC 111222 T and A. taiwanensis JCM 19755 T (Fig. 1). The similarity to other Algoriphagus species sequences was less than 96.5%. A. confluentis NBRC 111222 T and A. taiwanensis JCM 19755 T produce red water-insoluble pigments, which have never been characterized.

Structure determination of carotenoids produced by Algoriphagus sp. strain oki45

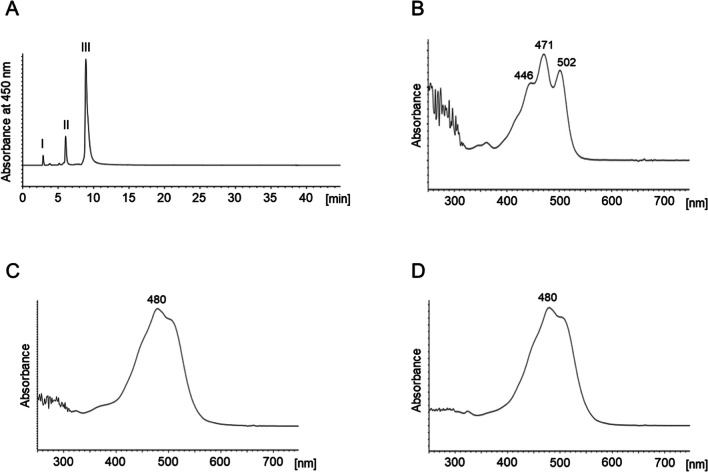

To elucidate the molecular structure of carotenoids produced by strain oki45, total lipids were extracted and then analyzed using HPLC equipped with a silica gel column (Fig. 2). At 450 nm, the total lipids of the strain oki45 exhibited three major peaks (Fig. 2A). The minor peak I (2.92 min) corresponded to the authentic lycopene standard regarding the retention time and absorption spectrum (Figs. 2B and S1). Peaks II (6.08 min) and III (8.92 min) exhibited characteristic absorption spectra (Fig. 2C, D), indicating the presence of conjugated keto groups. To obtain detailed structural information, peaks II and III were purified via TLC and C18-HPLC. Then, high-resolution MS, NMR, and CD spectroscopy data were recorded.

Fig. 2.

High-performance liquid chromatography profiles of the total lipid extracted from the strain oki45. A Chromatogram recorded at 470 nm. (B), (C), and (D) are the absorption spectra of peaks I, II, and III, respectively, depicted in (A)

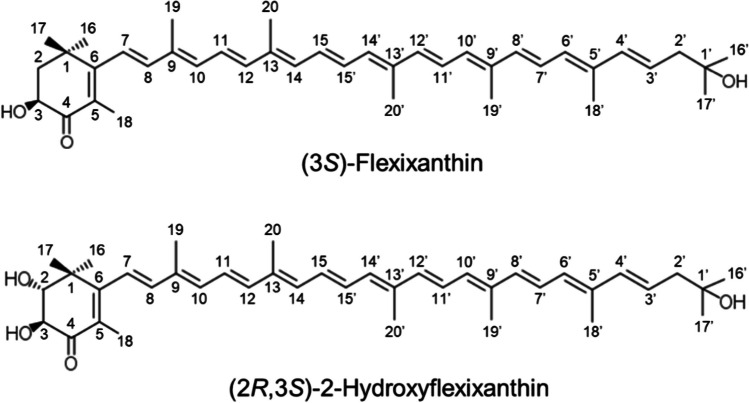

Peak II showed a protonated molecule at m/z 583.4112 (calcd for C40H55O3, 583.4105) in ESI TOF MS. ESI TOF MS/MS showed characteristic product ions of [MH-H2O]+ (m/z 565.4016), [MH-2H2O]+ (m/z 547.3928), and [MH-74]+ (m/z 509.3411), indicating a monocyclic terminal group (Fig. S2). The 1H NMR and CD spectroscopic data (Table 1 and Figs. S3–S6) were identical to those reported for (3S)-flexixanthin ((3S)-3,1′-dihydroxy-3′,4′-didehydro-1′,2′-dihydro-β,ψ-caroten-4-one) (Aasen and Jensen 1966; Coman and Weedon 1975; Andrewes et al. 1984). Therefore, this pigment was identified as (3S)-flexixanthin (Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Nuclear magnetic resonance data of peaks II and III

| Peak II | Peak III | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Position | δH (J in Hz) | δC | δH (J in Hz) |

| 1 | 41.8 | ||

| 2 | 1.81, dd (13.5, 13.5) | 77.5 | 3.53, d (11.5) |

| 2 | 2.15, dd (13.5, 5.5) | ||

| 3 | 4.32, ddd (14.5, 6) | 74.1 | 4.17, dd (11.5, 1.85) |

| 4 | 198.2 | ||

| 5 | 126.9 | ||

| 6 | 162.1 | ||

| 7 | 6.22, d (16) | 122.6 | 6.25, d (16) |

| 8 | 6.43, d (16) | 142.8 | 6.45, d (16) |

| 9 | 135.0 | ||

| 10 | 6.31, d (11) | 135.5 | 6.31, d (11) |

| 11 | 6.66, dd (15, 11) | 124.2 | 6.66, dd (15, 11) |

| 12 | 6.45, d (15) | 140.0 | 6.45, d (15) |

| 13 | 136.3 | ||

| 14 | 6.25, overlapped | 134.1 | 6.31, d (11) |

| 15 | 6.64, overlapped | 130.0 | ~ 6.65, m |

| 16 | 1.33, s | 20.1 | 1.27, s |

| 17 | 1.21, s | 25.7 | 1.30, s |

| 18 | 1.95, s | 14.0 | 1.94, s |

| 19 | 2.01, s | 12.8 | 2.00, s |

| 20 | 1.99, s | 12.8 | 1.99, s |

| 1′ | 72.7 | ||

| 2′ | 2.32, d (7.5) | 56.4 | 2.31, d (8) |

| 3′ | 5.76, dt (15, 7.5) | 124.5 | 5.77, dt (15, 8) |

| 4′ | 6.22, d (15) | 138.8 | 6.22, d (15) |

| 5′ | 137.2 | ||

| 6′ | 6.14, d (11) | 131.2 | 6.14, d (11) |

| 7′ | 6.61, dd (15, 11) | 124.7 | 6.61, dd (16, 11) |

| 8′ | 6.44, d (15) | 137.8/137.9 | 6.36, d (16) |

| 9′ | 136.2 | ||

| 10′ | 6.37, d (11.5) | 132.7 | 6.25, d (11) |

| 11′ | 6.64, overlapped | 125.4 | 6.64, dd (15, 11) |

| 12′ | 6.38, d (15) | 137.8/137.9 | 6.39, d (15) |

| 13′ | 136.3 | ||

| 14′ | 6.25, overlapped | 132.8 | 6.28, d (11) |

| 15′ | 6.64, overlapped | 131.0 | ~ 6.65, m |

| 16′ | 1.24, s | 29.2 | 1.24, s |

| 17′ | 1.24, s | 29.2 | 1.24, s |

| 18′ | 1.94, s | 13.0 | 1.94, s |

| 19′ | 1.99, s | 12.9 | 1.99, s |

| 20′ | 1.99, s | 12.6 | 1.99, s |

| 3-OH | 3.69, s | 3.68, d (2) |

s singlet, d doublet, dd doublet of doublets, ddd a doublet of doublets of doublets, m multiplet, dt doublet of triplets

Fig. 3.

The structures of (3S)-flexixanthin and (2R,3S)-2-hydroxyflexixanthin produced by the strain oki45

Peak III exhibited UV–Vis absorption maxima at 476 nm and a molecular ion at m/z 598.4012 (calcd for C40H54O4, 598.4022). ESI TOF MS/MS showed characteristic product ions of [M-92]+ (m/z 506.3360) and [M-58]+ (m/z 540.3564), indicating a monocyclic terminal group (Fig. S7). The 1H and 13C NMR data for this compound are listed in Table 1 (Figs. S8–S16, S22, and S23). These NMR data were assigned by correlation spectroscopy (COSY), nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (NOESY), heteronuclear single-quantum correlation spectroscopy (HSQC), and heteronuclear multiple-bond correlation spectroscopy (HMBC) and compared to previously published NMR data of carotenoids (Englert 1995; Yokoyama et al. 1996). Based on the UV–Vis and MS spectroscopic data, this carotenoid was assumed to be a hydroxyl derivative of flexixanthin. The COSY spectrum revealed a 11.5-Hz coupling between oxymetin protons at δ 3.53 and 4.17. This indicated that the protons of oxymetin were in the vicinal position and exhibited a trans configuration (Englert 1995; Yokoyama et al. 1996). Furthermore, the 1H and 13C NMR data of C-1 to C-6, including CH3 groups at positions 16, 17, and 18, of this compound were identical to those of 2-hydroxyastaxanthin (Yokoyama et al. 1996). Therefore, the position of the other hydroxyl group at the C-2 position of flexixanthin was determined. The CD spectrum of this compound (Fig. S17) showed [(EPA) nm (Δε) 240 (− 0.5), 245 (0), 270 (+ 2.0), 275 (0), 310 (− 11.8), 329 (0), 360 (+ 1.2)]) wavelengths similar to those described for (3S)-flexixanthin (Andrewes et al. 1984). It was reported that the chirality of the hydroxy group at C-3 primarily contributed to the shape of the CD spectrum of the 2,3-dihydroxy β-end group (Bucheker and Noack 1995). Consequently, it was found that this compound has the same chirality as (3S)-flexixanthin. The chirality of the hydroxyl group at the C-2 position was determined using NMR data pertaining to the relative configuration of the C-3 position. Thus, the compound was identified as ((2R,3S)-2,3,1′-trihydroxy-3′,4′-didehydro-1′,2′-dihydro-β,ψ-caroten-4-one) and designated as (2R,3S)-2-hydroxyflexixanthin (Fig. 3). Furthermore, A. confluentis NBRC 111222 T and A. taiwanensis JCM 19755 T also produced flexixanthin and 2-hydroxyflexixanthin (Fig. S18).

Prediction of carotenoid biosynthetic genes

To search for genes involved in the biosynthesis of flexixanthin and 2-hydroxyflexixanthin, we compared genome sequences of the strains oki45, A. confluentis NBRC 111222 T, and A. taiwanensis JCM 19755 T. The genome sequence of strain oki45 was estimated to be 4,617,600 bp with 40 contigs. The draft genome sequences of A. confluentis NBRC 111222 T and A. taiwanensis JCM 19755 T were 5,014,366 bp with 54 contigs and 4,563,290 bp with 51 contigs, respectively. The GC contents of oki45, A. confluentis NBRC 111222 T and A. taiwanensis JCM 19755 T were 43.8, 44.1, and 43.9%, respectively, and the putative protein coding regions (CDSs) were 4347, 4802, and 4315, respectively. In addition, 1957 CDSs, including carotenoid biosynthesis genes, were shared by oki45, A. confluentis NBRC 111222 T, and A. taiwanensis JCM 19755 T (Fig. S19).

Eight carotenoid biosynthetic genes (crtE, crtB, crtI, cruF, crtD, crtYcd, crtW, and crtZ) were predicted in the strain oki45 genome through a homology search (Table 2), which were presumed to be necessary for flexixanthin biosynthesis (Fig. 4). Interestingly, a gene homologous to crtG encoding 2,2ʹ-β-hydroxylase was found in the genome of strain oki45 (Table 2). These nine carotenoid biosynthetic genes were also present in the genomes of A. confluentis NBRC 111222 T and A. taiwanensis JCM 19755 T (Fig. S20).

Table 2.

Proposed carotenoid biosynthetic genes in Algoriphagus sp. strain oki45

| Name | Amino acid length | Description | Amino acid identity (%) | Organism | GenBank accession number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| crtE | 328 | Geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase | 68.9 | Cecembia lonarensis LW9 | EK47446 |

| crtB | 280 | Phytoene synthase | 77.4 | Algoriphagus sp. strain KK10202C | DQ286432 |

| crtI | 494 | Phytoene dehydrogenase | 83.3 | Algoriphagus sp. strain KK10202C | DQ286432 |

| cruF | 221 | 1,2-Hydratase | 32.1 | Haloarcula japonica TR-1 | LC008544 |

| crtD | 493 | Desaturase | 54.5 | Flavobacterium sp. P99-3 | AB97813 |

| crtYcd | 246 | Lycopene cyclase | 74.4 | Algoriphagus sp. strain KK10202C | DQ286432 |

| crtW | 234 | β-Ionone ring ketolase | 71.6 | Algoriphagus sp. strain KK10202C | DQ286432 |

| crtZ | 148 | β-Ionone ring hydroxylase | 42.9 | Flavobacterium sp. P99-3 | AB97813 |

| crtG | 269 | 2,2ʹ-β-Hydroxylase | 40.4 | Brevundimonas sp. SD212 | AB181388 |

Fig. 4.

Proposed carotenoid biosynthetic pathway in the strain oki45. CrtE, geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase; CrtB, phytoene synthase; CrtI, phytoene dehydrogenase; CruF, 1,2-hydratase; CrtD, desaturase; CrtYcd, lycopene cyclase; CrtW, β-ionone ring ketolase; CrtZ, β-ionone ring hydroxylase; CrtG, 2,2ʹ-β-hydroxylase

Discussion

Recently, carotenoids have attracted attention due to their health benefits (Elvira-Torales et al. 2019). Monocyclic structure of carotenoids can be associated with several biological activities, such as antioxidative and neuroprotective effects (Shindo et al. 2007) and neurogenesis activity (Kim et al. 2016). However, only a small number of monocyclic carotenoids have been identified, and information about their producers is limited. Some marine bacteria produce monocyclic carotenoids, and their biosynthetic genes have been found (Rählert et al. 2009; Teramoto et al. 2003; Teramoto et al. 2004). For future applications of monocyclic carotenoids, such as bioactive components and alternative production in heterologous hosts, it is necessary to accumulate knowledge on monocyclic carotenoid-producing bacteria and their biosynthetic genes.

The genus Algoriphagus in the family Cyclobacteriaceae was first proposed by Bowman et al. (2003). It has been isolated from various sources, such as Antarctic sea ice, seawater, and sediment. Although the bacteria are known to produce an orange-to-red color, their pigment composition has not been completely clarified. Herein, strain oki45 was isolated from the surface of a seaweed collected in Okinawa, and 16S rRNA phylogenetic analysis revealed that the strain belonged to the genus Algoriphagus. The strain oki45 was closely related to A. confluentis NBRC 111222 T and A. taiwanensis JCM 19755 T with 99.1% nucleotide sequence similarity (Fig. 1). Further ANI calculations using newly sequenced genomes of oki45, A. confluentis NBRC 111222 T and A. taiwanensis JCM 19755 T, revealed 85.4% and 88.5% ANI of oki45 against A. confluentis NBRC 111222 T and A. taiwanensis JCM 19755 T, respectively, which is below the species threshold of 95% (Fig. S21). The in silico DDH similarity of strain oki45 against A. confluentis NBRC 111222 T and A. taiwanensis JCM 19755 T was 35.7% and 29.5%, respectively, which is also below the species boundary of 70% (Table S1). Therefore, it was suggested that the strain oki45 may be a new species of the genus Algoriphagus.

Structural analysis revealed that the strain oki45 produced both flexixanthin and its hydroxylated derivative, 2-hydroxyflexixanthin (Figs. 2 and 3). Deinoxanthin, a 2-hydroxyl monocyclic carotenoid, helps the bacteria grow in extreme environments by quenching intracellular ROS in radio-tolerant D. radiodurans (Tian et al. 2007). Interestingly, the C-2 hydroxy group of deinoxanthin was shown to play an essential role in ROS quenching (Zhou et al. 2015). Furthermore, 2-hydroxylation of canthaxanthin, although not a monocyclic carotenoid, enhanced its inhibitory effect on lipid peroxidation (Nishida et al. 2005). Therefore, 2-hydroxyflexixanthin, which possesses a hydroxy group at the C-2 position, may also exhibit antioxidant activity.

Tao et al. (2006) reported that Algoriphagus sp. strain KK10202C produces flexixanthin. Furthermore, they identified four genes involved in flexixanthin biosynthesis in the strain KK10202C, i.e., phytoene synthase (crtB), phytoene dehydrogenase (crtI), lycopene cyclase (crtYcd), and β-ionone ring ketolase (crtW), which were found in a cluster (Tao et al. 2006). However, the presence of other carotenogenic genes, such as geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase (crtE), desaturase (crtD), 1,2-hydratase, and β-ionone ring hydroxylase (crtZ), was not clear. Although crtC might be involved in the conversion of lycopene to rhodopin as a 1,2-hydratase in the strain KK10202C (Tao et al. 2006), a crtC homolog was not found in the genome of strain oki45, A. confluentis NBRC 111222 T or A. taiwanensis JCM 19755 T. A cruF gene, which is an ortholog of crtC, is responsible for the 1,2-hydratase of γ-carotene in the nonphotosynthetic bacteria D. radiodurans R1 and D. geothermalis DSM 11300 (Sun et al. 2009). Gene cruF is known to be evolutionarily distant from crtC. Since the cruF gene was involved in a cluster with crtZ, crtI, crtB, crtYcd, and crtW (Fig. S20), it was speculated that the cruF gene could associate with C-1,2 hydration in carotenoids produced by Algoriphagus bacteria.

Genes encoding 2,2ʹ-β-hydroxylase were found for the first time in the strain oki45, A. confluentis NBRC 111222 T, and A. taiwanensis JCM 19755 T (Fig. S20), and these Algoriphagus strains can biosynthesize 2-hydroxyflexixanthin (Fig. S18). Interestingly, the genes were homologous to crtG in Brevundimonas sp. SD212, which has been confirmed to catalyze C-2(2ʹ)-hydroxylation of the β-ionone ring (Nishida et al. 2005). Furthermore, the crtG gene product of Thermosynechococcus elongatus strain BP-1 catalyzes the 2-hydoxylation of myxol glycosides (Iwai et al. 2008). Therefore, Algoriphagus’s crtG genes may be involved in 2-hydroxyflexixanthin biosynthesis (Fig. 4). To estimate gene function, in vitro assays using isolated enzymes and in vivo assays using gene knockout systems or gene expression systems in heterologous hosts are performed. Most of the carotenoid biosynthetic genes encode membrane-associated enzymes, making it difficult to isolate them while retaining enzymatic activity. Furthermore, according to our knowledge, no knockout system for carotenoid biosynthesis genes in Algoriphagus bacteria has been established. On the other hand, carotenoid production in E. coli is useful in that there is no need to isolate the enzyme. However, in order to produce the desired carotenoid in E. coli, it is necessary to introduce a large number of genes and to stably express all of them. Even the production of the precursor flexixanthin in E. coli has not yet been established. Further studies of these crtG genes, including functional analysis using heterologous hosts, are needed in the future.

In conclusion, we isolated Algoriphagus sp. strain oki45 from the surface of unidentified seaweed collected in Okinawa, Japan. Two red pigments produced by the strain oki45, (3S)-flexixanthin and (2R,3S)-2-hydroxyflexixanthin, were identified as rare and novel monocyclic carotenoids. Two Algoriphagus strains that were related to the strain oki45 also synthesized both monocyclic carotenoids. Furthermore, whole genome analysis found eight genes (crtE, crtB, crtI, cruF, crtD, crtYcd, crtW, and crtZ) for flexixanthin biosynthesis. In addition, a gene with homology to 2,2ʹ-β-hydroxylase-encoding crtG was found in the strains oki45, A. confluentis NBRC 111222 T, and A. taiwanensis JCM 19755 T, suggesting that the gene is involved in 2-hydroxyflexixanthin biosynthesis. These findings expand our knowledge of monocyclic carotenoid biosynthesis in Algoriphagus bacteria.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. Hiroyuki Yasui, Department of Analytical and Bioinorganic Chemistry, Kyoto Pharmaceutical University, for measurement of CD spectra. The authors also thank Yuta Tsuchihashi, Faculty of Fisheries Sciences, Hokkaido University, for technical support.

Author contribution

NT: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, visualization, writing—original draft. TM: investigation, visualization, writing—review and editing. TS: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, visualization, writing—review and editing. FB: conceptualization, writing—review and editing. MH: conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, writing—review and editing.

Funding

This study was funded by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 23K14018 and 23658155 and Strategic Japanese–Brazilian Cooperative Program (JST-CNPq).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information file.

Declarations

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aasen AJ, Jensen SL (1966) Carotenoids of flexibacteria. 3. The structures of flexixanthin and deoxy-flexixanthin. Acta Chem Scand 20:1970–1988. 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.20-1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrewes AG, Foss P, Borch G, Liaaen-Jensen S (1984) Bacterial carotenoids. 50. On the structures of (3S)-flexixanthin and (3S,2ʹS)-2ʹ-hydroxyflexixanthin. Acta Chem Scand B38:337–339. 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.38b-0337 [Google Scholar]

- Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Kubal M, Meyer F, Olsen GJ, Olson R, Osterman AL, Overbeek RA, McNeil LK, Paarmann D, Paczian T, Parrello B, Pusch GD, Reich C, Stevens R, Vassieva O, Vonstein V, Wilke A, Zagnitko O (2008) The RAST Server: Rapid Annotations using Subsystems Technology. BMC Genomics 9:75. 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman JP, Nichols CM, Gibson JAE (2003) Algoriphagus ratkowskyi gen. nov., sp. nov., Brumimicrobium glaciale gen. nov., sp. nov., Cryomorpha ignava gen. nov., sp. nov. and Crocinitomix catalasitica gen. nov., sp. nov., novel flavobacteria isolated from various polar habitats. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 53:1343–1355. 10.1099/ijs.0.02553-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucheker R, Noack K (1995) Circular dichroism. In: Britton G, Liaaen-Jensen S, Pfander H (eds) Carotenoids, vol 1B. spectroscopy. Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel, pp 63–116 [Google Scholar]

- Coman RE, Weedon BC (1975) Carotenoids and related compounds. Part XXXIII. Synthesis of dehydroflexixanthin and deoxyflexixanthin. J Chem Soc Perkin 1:2529–2532. 10.1039/P19750002529 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elvira-Torales LI, García-Alonso J, Periago-Castón MJ (2019) Nutritional importance of carotenoids and their effect on liver health: a review. Antioxidants (basel) 8:229. 10.3390/antiox8070229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englert G (1995) NMR spectroscopy. In: Britton G, Liaaen-Jensen S, Pfander H (eds) Carotenoids, vol 1B. spectroscopy. Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel, pp 147–150 [Google Scholar]

- Finn RD, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, Eddy SR, Mistry J, Mitchell AL, Potter SC, Punta M, Qureshi M, Sangrador-Vegas A, Salazar GA, Tate J, Bateman A (2016) The Pfam protein families database: towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res 44:279–285. 10.1093/nar/gkv1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH (1957) A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem 226:497–509. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)64849-5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasteiger E, Gattiker A, Hoogland C, Ivanyi I, Appel RD, Bairoch A (2003) ExPASy: The proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 31:3784–3788. 10.1093/nar/gkg563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai M, Maoka T, Ikeuchi M, Takaichi S (2008) 2,2’-Beta-hydroxylase (CrtG) is involved in carotenogenesis of both nostoxanthin and 2-hydroxymyxol 2ʹ-fucoside in Thermosynechococcus elongatus strain BP-1. Plant Cell Physiol 49:1678–1687. 10.1093/pcp/pcn142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajitani R, Toshimoto K, Noguchi H, Toyoda A, Ogura Y, Okuno M, Yabana M, Harada M, Nagayasu E, Maruyama H, Kohara Y, Fujiyama A, Hayashi T, Itoh T (2014) Efficient de novo assembly of highly heterozygous genomes from whole-genome shotgun short reads. Genome Res 24:1384–1395. 10.1101/gr.170720.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Kim M, Lee B, Lee P (2016) Generation of structurally novel short carotenoids and study of their biological activity. Sci Rep 6:21987. 10.1038/srep21987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K (2016) MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 33:1870–1874. 10.1093/molbev/msw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Ouk Kim Y, Park SC, Chun J (2016) OrthoANI: an improved algorithm and software for calculating average nucleotide identity. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 66:1100–1103. 10.1099/ijsem.0.000760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier-Kolthoff JP, Auch AF, Klenk HP, Göker M (2013) Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinformatics 14:60. 10.1186/1471-2105-14-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misawa N, Satomi Y, Kondo K, Yokoyama A, Kajiwara S, Saito T, Ohtani T, Miki W (1995) Structure and functional analysis of a marine bacterial carotenoid biosynthesis gene cluster and astaxanthin biosynthetic pathway proposed at the gene level. J Bacteriol 177:6575–6584. 10.1128/jb.177.22.6575-6584.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mount DW (2007) Using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST). CSH Protoc 17 10.1101/pdb.top17 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nishida Y, Adachi K, Kasai H, Shizuri Y, Shindo K, Sawabe A, Komemushi S, Miki W, Misawa N (2005) Elucidation of a carotenoid biosynthesis gene cluster encoding a novel enzyme, 2,2ʹ-beta-hydroxylase, from Brevundimonas sp. strain SD212 and combinatorial biosynthesis of new or rare xanthophylls. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:4286–4296. 10.1128/AEM.71.8.4286-4296.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary NA, Wright MW, Brister JR, Ciufo S, Haddad D, McVeigh R, Rajput B, Robbertse B, Smith-White B, Ako-Adjei D, Astashyn A, Badretdin A, Bao Y, Blinkova O, Brover V, Chetvernin V, Choi J, Cox E, Ermolaeva O, Farrell CM, Goldfarb T, Gupta T, Haft D, Hatcher E, Hlavina W, Joardar VS, Kodali VK, Li W, Maglott D, Masterson P, McGarvey KM, Murphy MR, O’Neill K, Pujar S, Rangwala SH, Rausch D, Riddick LD, Schoch C, Shkeda A, Storz SS, Sun H, Thibaud-Nissen F, Tolstoy I, Tully RE, Vatsan AR, Wallin C, Webb D, Wu W, Landrum MJ, Kimchi A, Tatusova T, DiCuccio M, Kitts P, Murphy TD, Pruitt KD (2016) Reference sequence (RefSeq) database at NCBI: current status, taxonomic expansion, and functional annotation. Nucleic Acids Res 44:733–745. 10.1093/nar/gkv1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Kim S, Jung YT, Yoon JH (2016) Algoriphagus confluentis sp. nov., isolated from the junction between the ocean and a freshwater lake. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 66:118–124. 10.1099/ijsem.0.000686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rählert N, Fraser PD, Sandmann G (2009) A crtA-related gene from Flavobacterium P99–3 encodes a novel carotenoid 2-hydroxylase involved in myxol biosynthesis. FEBS Lett 583:1605–1610. 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M (1987) The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4:406–425. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayers EW, Beck J, Bolton EE, Bourexis D, Brister JR, Canese K, Comeau DC, Funk K, Kim S, Klimke W, Marchler-Bauer A, Landrum M, Lathrop S, Lu Z, Madden TL, O’Leary N, Phan L, Rangwala SH, Schneider VA, Skripchenko Y, Wang J, Ye J, Trawick BW, Pruitt KD, Sherry ST (2021) Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res 49:D10–D17. 10.1093/nar/gkaa892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahina M, Hameed A, Lin SY, Lai WA, Hsu YH, Young CC (2014) Description of Algoriphagus taiwanensis sp. nov., a xylanolytic bacterium isolated from surface seawater, and emended descriptions of Algoriphagus mannitolivorans, Algoriphagus olei, Algoriphagus aquatilis and Algoriphagus ratkowskyi. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 106:1031–1040. 10.1007/s10482-014-0272-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindo K, Kikuta K, Suzuki A, Katsuta A, Kasai H, Yasumoto-Hirose M, Matsuo Y, Misawa N, Takaichi S (2007) Rare carotenoids, (3R)-saproxanthin and (3R,2ʹS)-myxol, isolated from novel marine bacteria (Flavobacteriaceae) and their antioxidative activities. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 74:1350–1357. 10.1007/s00253-006-0774-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z, Shen S, Wang C, Wang H, Hu Y, Jiao J, Ma T, Tian B, Hua Y (2009) A novel carotenoid 1,2-hydratase (CruF) from two species of the non-photosynthetic bacterium Deinococcus. Microbiology 155:2775–2783. 10.1099/mic.0.027623-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swapnil P, Meena M, Singh SK, Dhuldhaj UP, Harish MA (2021) Vital roles of carotenoids in plants and humans to deteriorate stress with its structure, biosynthesis, metabolic engineering and functional aspects. Curr Plant Biol 26:100203. 10.1016/j.cpb.2021.100203 [Google Scholar]

- Teramoto M, Takaichi S, Inomata Y, Ikenaga H, Misawa N (2003) Structural and functional analysis of a lycopene beta-monocyclase gene isolated from a unique marine bacterium that produces myxol. FEBS Lett 545:120–126. 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00513-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teramoto M, Rählert N, Misawa N, Sandmann G (2004) 1-Hydroxy monocyclic carotenoid 3,4-dehydrogenase from a marine bacterium that produces myxol. FEBS Lett 570:184–188. 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.05.085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takatani N, Nishida K, Sawabe T, Maoka T, Miyashita K, Hosokawa M (2014) Identification of a novel carotenoid, 2′-isopentenylsaproxanthin, by Jejuia pallidilutea strain 11shimoA1 and its increased production under alkaline condition. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 98:6633–6640. 10.1007/s00253-014-5702-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takatani N, Sawabe T, Maoka T, Miyashita K, Hosokawa M (2015) Structure of a novel monocyclic carotenoid, 3″-hydroxy-2′-isopentenylsaproxanthin ((3R,2′S)-2′-(3-hydroxy-3-methylbutyl)-3′,4′-didehydro-1′,2′-dihydro-β, ψ-carotene-3,1′-diol), from a flavobacterium Gillisia limnaea strain DSM 15749. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 4:174–179. 10.1016/j.bcab.2015.02.005 [Google Scholar]

- Tao L, Yao H, Kasai H, Misawa N, Cheng Q (2006) A carotenoid synthesis gene cluster from Algoriphagus sp. KK10202C with a novel fusion-type lycopene beta-cyclase gene. Mol Genet Genomics 276:79–86. 10.1007/s00438-006-0121-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian B, Xu Z, Sun Z, Lin J, Hua Y (2007) Evaluation of the antioxidant effects of carotenoids from Deinococcus radiodurans through targeted mutagenesis, chemiluminescence, and DNA damage analyses. Biochim Biophys Acta 1770:902–911. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2007.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabuzaki J (2017) Carotenoids database: structures, chemical fingerprints and distribution among organisms. Database 2017:1–11. 10.1093/database/bax004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama A, Miki W, Izumida H, Shizuri Y (1996) New trihydroxy-keto-carotenoids isolated from an astaxanthin-producing marine bacterium. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 60:200–203. 10.1271/bbb.60.200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama A, Miki W (1995) Isolation of myxol from a marine bacterium Flavobacterium sp. associated with a marine sponge. Fish Sci 61:684–686. 10.2331/fishsci.61.684 [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Zhang W, Su S, Chen M, Lu W, Lin M, Molnár I, Xu Y (2015) CYP287A1 is a carotenoid 2-β-hydroxylase required for deinoxanthin biosynthesis in Deinococcus radiodurans R1. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 99:10539–10546. 10.1007/s00253-015-6910-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information file.