Abstract

BACKGROUND

Gastric ectopic pancreas (GEP) is a rare developmental abnormality that refers to the existence of pancreatic tissue in the stomach with no anatomical relationship with the main pancreas. It is usually difficult to diagnose through histological examination, and the choice of treatment method is crucial.

AIM

To describe the endoscopic ultrasound characteristics of GEP and evaluate the value of laparoscopic resection (LR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD).

METHODS

Forty-nine patients with GEP who underwent ESD and LR in the Second Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University from May 2018 to July 2023 were retrospectively included. Data on clinical characteristics, endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), ESD, and LR were collected and analyzed. The characteristics of EUS and the efficacy of the two treatments were analyzed.

RESULTS

The average age of the patients was 43.31 ± 13.50 years, and the average maximum diameter of the lesions was 1.55 ± 0.70 cm. The lesion originated from the mucosa in one patient (2.04%), from the submucosa in 42 patients (85.71%), and from the muscularis propria in 6 patients (12.25%). Twenty-nine patients (59.20%) with GEP showed umbilical depression on endoscopy. The most common initial symptom of GEP was abdominal pain (40.82%). Tumor markers, including carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA-19-9), were generally within the normal range. One patient (2.04%) with GEP had increased CEA and CA-19-9 levels. However, no cancer tissue was found on postoperative pathological examination, and tumor markers returned to normal levels after resecting the lesion. There was no significant difference in surgery duration (72.42 ± 23.84 vs 74.17 ± 12.81 min) or hospital stay (3.70 ± 0.91 vs 3.83 ± 0.75 d) between the two methods. LR was more often used for patients with larger tumors and deeper origins. The amount of bleeding was significantly higher in LR than in ESD (11.28 ± 16.87 vs 16.67 ± 8.76 mL, P < 0.05). Surgery was associated with complete resection of the lesion without any serious complications; there were no cases of recurrence during the follow-up period.

CONCLUSION

GEP has unique characteristics in EUS. LR and ESD seem to be good choices for treating GEP. LR is better for large GEP with a deep origin. However, due to the rarity of GEP, multicenter large-scale studies are needed to describe its characteristics and evaluate the safety of LR and ESD.

Keywords: Ectopic pancreas, Endoscopic ultrasonography, Endoscopic submucosal dissection, Laparoscopic resection

Core Tip: Gastric ectopic pancreas (GEP) is a rare disease. At present, the study on GEP is mostly limited to case reports. Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is the main examination method for the diagnosis of GEP. We summarized the characteristics of GEP under EUS and compared the advantages and disadvantages of laparoscopic resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection in the treatment of GEP. Both methods are safe and feasible. Due to the low incidence of this disease, we look forward to multicenter studies with large sample sizes.

INTRODUCTION

Ectopic pancreas (EP) is a well-differentiated pancreatic tissue without anatomical or vascular contact with the pancreas[1]. The most common site for EP is the stomach, followed by the duodenum and jejunum, often involving the submucosa, muscularis propria, and/or subserosal layer[2,3]. The exact pathogenic mechanism of EP in humans is unknown. Currently, there are three theories: (1) Pancreatic cells abnormally enter the developing gastrointestinal system; (2) pancreatic metaplasia occurs in other endodermal tissues during embryonic development; and (3) there are totipotent cells within the endoderm that differentiate into pancreatic tissue[4]. After the complete development of a gastric EP (GEP), it can be histologically divided into four types: Type 1 that is composed of acini, ducts, and islet cells; type 2 that is only composed of catheters; type 3 that is only composed of acini; and type 4 that is only composed of islet cells[5].

Generally, EP has no clinical manifestations, and most cases are found incidentally during digestive endoscopy or radiological examination. Most symptomatic patients have large lesions causing intussusception or bleeding[6]. The incidence of EP is very low. According to relevant studies, the incidence of EP in abdominal surgery is 0.20-0.25%, and the detection rate in autopsy is 0.55-13%[7]. GEP is often difficult to diagnose. Most asymptomatic patients do not need surgery or endoscopic resection; thus, it is difficult to obtain pathological results. EP may mimic other submucosal tumors, particularly gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) with malignant potential. Due to nonspecific imaging findings, it is difficult to differentiate between EP and other submucosal tumors, such as GISTs[6,8].

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) combines gastrointestinal endoscopy and ultrasound imaging and outperforms computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging in identifying gastrointestinal submucosal lesions or pancreatic cystic disease[9]. Park et al[8] retrospectively analyzed 26 pathologically confirmed patients with EP who underwent EUS and found that EP has unclear borders, lobulated edges, and anechoic duct-like structures. These features have potential value in differentiating between EP and other gastric submucosal tumors (SMTs). Hirai et al[10] applied radiomics and artificial intelligence to predict common types of subcutaneous lesions, such as GISTs and EP, in EUS images and concluded that the diagnostic efficacy of artificial intelligence in classifying subepithelial lesions is superior to that of experts, improving the accuracy of clinical diagnosis.

Laparoscopic resection (LR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) are both recommended methods for SMTs[11]. We have not found any studies comparing LR with ESD for treating GEP. Data on the safety and efficacy of these two approaches are rare. We applied EUS to describe the characteristics of GEP and distinguish it from other gastric mesenchymal tumors. We compared the two surgical methods to provide evidence for treating GEP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

We conducted a retrospective study in the Second Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University. Those who underwent LR and ESD between May 2018 and July 2023 were identified, and data were retrospectively collected from the patient electronic database. The protocol of this study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University.

Ultrasound image analysis and clinical features

Image analysis, including lesion location, size, origin, internal echo characteristics, internal presence of echo or pipeline structure, echo intensity, edge, umbilical or central depression, etc., were collected.

According to the endoscopic findings, the location of the lesion was divided into the gastric body, gastric angle, and gastric antrum. In EUS, the gastric wall is divided into five layers, namely, the mucosal layer, muscularis mucosa, submucosal layer, muscularis propria, and serosal layer from the inside to the outside. Echo intensity was classified into hypoechoic or hyperechoic, internal echo into homogeneous or heterogeneous, and edge into clear or unclear.

The clinical characteristics of the patients, including age, sex, initial symptoms, serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA-199), treatment methods, operation time, intraoperative blood loss, hospital stay, postoperative follow-up, and other data, were collected.

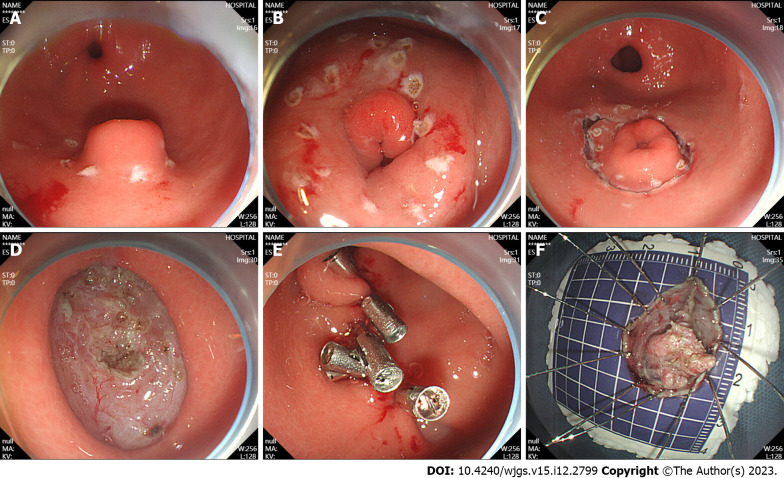

Methods of endoscopic resection

ESD of GEP was performed as follows: (1) Labeling: A high-frequency electric generator was used with the parameters set at 3-2-4. The electric coagulation power was 50 W, and the Dual-knife was used for circumferential electrocoagulation labeling on the periphery of the lesion (Figure 1A); (2) submucosal injection: The glycerin fructose-methylene blue-epinephrine mixture was injected to the submucosal layer, and the lifting sign was positive (Figure 1B); (3) an incision was made along the mark: After satisfactory uplift, a circumferential incision was performed with dual-knife along the lateral edge of the mark to expose the yellow submucosal mass (Figure 1C); (4) tumor resection: The lesions were dissected along the submucosa with a dual-knife, and submucosal injections were repeatedly performed during dissection to maintain adequate elevation of the lesions. Timely electrocoagulation was used to expose blood vessels and bleeding points during the surgery, and the lesions were completely dissected (Figure 1D); (5) wound treatment: If the wound left a small amount of residual yellow organization, a hot biopsy was used for burning in addition to hemostatic treatment and clamp closure of the wound (Figure 1E); and (6) the specimen was removed and sent for pathological examination (Figure 1F).

Figure 1.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection. A: Ectopic pancreas was located in the gastric antrum; B: Marked incision line; C: The surrounding tissues of the tumor along the marker were cut; D: Complete tumor resection; E: Intraoperative precautions. F: Removal of the lesions.

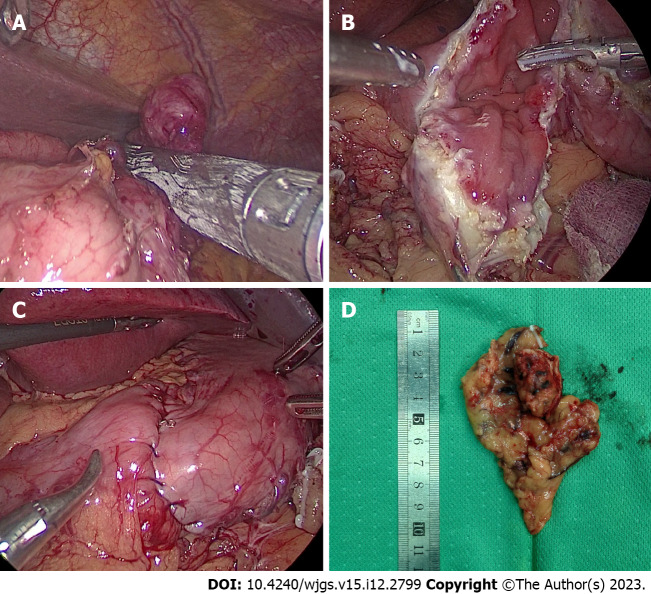

LR

The surgical procedure for the patients who underwent LR in our study was laparoscopic wedge resection. This type of surgery involves resection of the tumor using a suitable laparoscopic linear anastomosis (Figure 2A). If the location of the tumor is peculiar and the use of a laparoscopic linear anastomosis is difficult, we can remove the tumor completely after incising the gastric wall along the edges of the tumor (Figure 2B) and either laparoscopically through a laparoscopic linear obturator or by hand suturing the defective gastric wall (Figure 2C). Finally, the intact tumor specimen was removed from the abdominal cavity through a specimen bag and sent to the pathology department for examination (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Laparoscopic resection. A: Laparoscopic view of tumor resection using laparoscopic linear anastomosis; B: Laparoscopic view of wedge resection after incision of the gastric wall to exsanguinate the tumor; C: Suture and reinforcement of the remnant gastric wall; D: Pathological specimen.

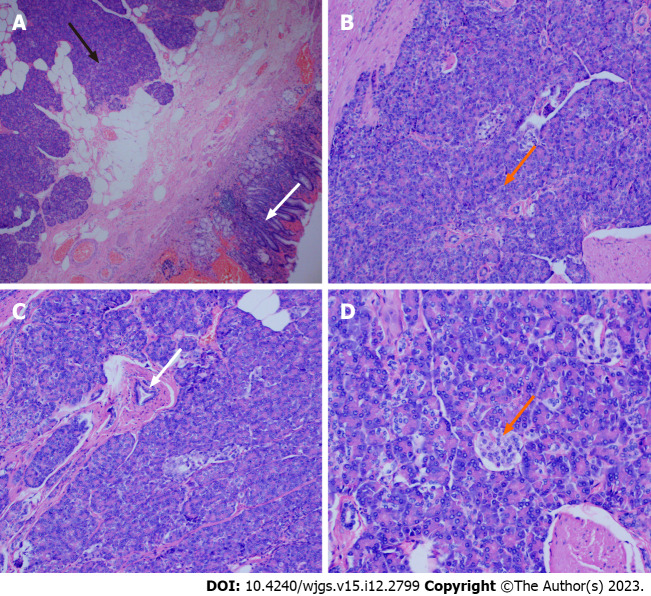

Pathological examination

The specimens were removed and sent to the pathology department for histological examination. The excised tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. The lesions were solid on the cut surface and mainly originated from the submucosa and muscularis propria. The tissues were embedded in paraffin and cut into 3 μm thick slices. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Histological examinations revealed that the lesion in the stomach was an EP (Figure 3A). We found acini (Figure 3B), ducts (Figure 3C), and pancreatic islet cells (Figure 3D) in the submucosa.

Figure 3.

Pathological view of a gastric ectopic pancreas. A: Pancreatic tissue (black arrow) and gastric mucosal tissue (white arrow), (magnification, × 40); B: Numerous acini (orange arrow) were observed in pancreatic tissue (magnification, × 100); C: Ducts were observed in the pancreatic tissue (white arrow) (magnification, × 100); D: Islet cells were observed in the pancreatic tissue (orange arrow) (magnification, × 200).

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS (27.0) was used for statistical analysis. Continuous data are expressed as the mean ± SD, and categorical data are expressed as n (%). Student’s t test was used to compare normally distributed variables, the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare nonnormally distributed variables, and the chi-square test (or Fisher’s exact test) was used to compare categorical variables. In this study, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

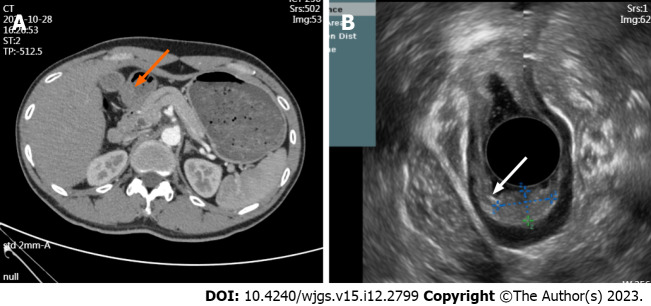

The clinical characteristics of the 49 patients are summarized in Table 1. Among the patients, 26 were male and 23 were female, with an average age of 43.31 ± 13.50 years. A considerable number of patients were asymptomatic (36.73%), and the most common clinical symptom was abdominal pain (40.82%), followed by acid reflux (16.33%), abdominal distension (4.08%), and diarrhea (2.04%). All patients underwent ESD (n = 43) or LR (n = 6). Most of the patients underwent ESD to resect the lesion. CEA and CA-19-9 were within the normal range; however, one patient had elevated CEA (5.29 ng/mL) and CA-19-9 (42.3 μ/mL) levels. Thickening of the gastric antrum and multiple retroperitoneal lymph nodes were observed on CT images (Figure 4A), but EUS indicated a possible EP (Figure 4B). Postoperative pathology confirmed that the tumor was EP, and tumor markers returned to normal after the operation.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients (mean ± SD)

| Variables | N (%) |

| Age (yr) | 43.31 ± 13.50 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 26 (53.06) |

| Female | 23 (46.94) |

| Symptom | |

| Abdominal pain | 20 (40.82) |

| Acid reflux/heartburn | 8 (16.33) |

| Diarrhea | 1 (2.04) |

| Abdominal distension | 2 (4.08) |

| Asymptomatic | 18 (36.73) |

| Treatment methods | |

| ESD | 43 (87.76) |

| LR | 6 (12.24) |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 2.17 ± 1.18 |

| CA-19-9 (μ/mL) | 13.00 ± 7.53 |

ESD: Endoscopic submucosal dissection; LR: Laparoscopic resection; CEA: carcinoembryonic antigen; CA-19-9: carbohydrate antigen 19-9.

Figure 4.

Computed tomography images and endoscopic ultrasound images. A: The arterial phase of enhanced computed tomography showed thickening of the gastric antrum (orange arrow); B: Lesion morphology on endoscopic ultrasound (white arrow).

Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of EP under EUS. The lesion was located in the gastric antrum in 39 cases (39/49, 79.59%), in the gastric body in 7 cases (7/49, 14.29%), and in the gastric angle in 3 cases (3/49, 6.12%). The average size of the lesions was 1.55 ± 0.70 cm. The lesion originated from the submucosa in 42 cases (42/49, 85.71%), from the muscularis propria in six cases (6/49, 12.25%), and from the mucosa in one case (1/49, 2.04%). Thirty-five lesions (35/49, 71.43%) showed hypoechogenicity, 22 lesions (22/49, 44.90%) showed homogeneous, 27 lesions (27/49, 55.10%) showed heterogenous. Twenty-seven lesions (27/49, 55.10%) had clear and regular margins, 29 lesions (29/49, 59.18%) showed an echo-free area or a duct-like structure, and 29 lesions (29/49, 59.18%) showed a central depression or an umbilicus-like depression.

Table 2.

Endoscopic ultrasound features of gastric ectopic pancreas (mean ± SD)

| Patients | N (%) |

| Size (cm) | 1.55 ± 0.70 |

| Origin hierarchy | |

| Mucosal layer | 1 (2.04) |

| Submucosa | 42 (85.71) |

| Muscularis propria | 6 (12.25) |

| Tumor location | |

| Gastric body | 7 (14.29) |

| Gastric angle | 3 (6.12) |

| Gastric antrum | 39 (79.59) |

| Echogenicity | |

| Homogeneous | 22 (44.90) |

| Heterogenous | 27 (55.10) |

| Echogenicity | |

| Hypoechoic | 35 (71.43) |

| Hyperechoic | 14 (28.57) |

| Margin | |

| Indistinct | 22 (44.90) |

| Distinct | 27 (55.10) |

| Anechoic duct-like structure | |

| Absent | 20 (40.82) |

| Present | 29 (59.18) |

| Umbilication/dimpling | |

| Absent | 20 (40.82) |

| Present | 29 (59.18) |

Table 3 summarizes the characteristics of the two treatment modalities. Compared to LR, there were no significant differences in age, sex, tumor location, surgery duration, meal duration, or hospital stay between the ESD and LR group. In the ESD group, the lesions were smaller (1.33 ± 0.41 vs 3.08 ± 2.23 cm, P < 0.001), their origins had lower depths (P = 0.01), and blood loss was lower (11.28 ± 16.87 vs 16.67 ± 8.76 mL, P = 0.034). Laparoscopic surgery incurred a higher cost; however, it was not statistically significant. Neither LR nor ESD caused any major intraoperative or postoperative complications, including any Clavien-Dindo grade ≥ I or more severe complications. There were no significant differences in tumor rupture or the total resection rates between the two groups. During a median follow-up period of 29.7 months, no patients experienced recurrence after surgery.

Table 3.

Comparison of the endoscopic submucosal dissection group and laparoscopic surgery group in the treatment of gastric ectopic pancreas (mean ± SD)

| Patients | ESD (%) | LR (%) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 43.58 ± 13.77 | 41.33 ± 12.34 | 0.819 |

| Size (cm) | 1.33 ± 0.41 | 3.08 ± 2.23 | < 0.001 |

| Sex | 0.688 | ||

| Male | 24 (55.8) | 4 (66.7) | |

| Female | 19 (44.2) | 2 (33.3) | |

| Tumor location | 0.795 | ||

| Gastric body | 6 (14.0) | 1 (16.7) | |

| Gastric horn | 3 (7.0) | 0 (0) | |

| Gastric antrum | 34 (79.1) | 5 (83.3) | |

| Origin hierarchy | 0.01 | ||

| Mucosal layer | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Submucosa | 39 (90.7) | 3 (50.0) | |

| Muscularis propria | 3 (7.0) | 3 (50.0) | |

| Operative time (min) | 72.42 ± 23.84 | 74.17 ± 12.81 | 0.491 |

| Estimated blood loss (mL) | 11.28 ± 16.87 | 16.67 ± 8.76 | 0.034 |

| Recovery eating time (days) | 1.63 ± 0.58 | 1.83 ± 0.75 | 0.501 |

| Postoperative length of stay (days) | 3.70 ± 0.91 | 3.83 ± 0.75 | 0.611 |

| Clavien-Dindo ≥ I grade | 0 | 0 | - |

| Tumor recurrence | 0 | 0 | - |

| Hospitalization expenses | 2854.00 ± 544.05 | 3378.33 ± 1133.62 | 0.180 |

| Follow-up length (months) | 29.79 ± 20.00 | 29.17 ± 16.28 | 1.00 |

ESD: Endoscopic submucosal dissection; LR: Laparoscopic resection.

DISCUSSION

SMTs are detected as incidental findings during routine upper gastrointestinal endoscopy[12]. They can occur in any layer of the intestinal wall and are classified as nonepithelial mesenchymal tumors. SMTs, which grow only in the gastric wall and rarely show lymph node metastasis, and GISTs are the most common type of SMT[11,13]. GEP is a rare disease and is difficult to distinguish from other submucosal tumors[14]. Most of the previous studies are case reports, and there is a lack of studies with large sample sizes. This study summarized the characteristics of GEP in EUS and compared the safety of LR and ESD in the treatment of GEP.

EUS has great advantages in diagnosing SMTs[15]. EUS can provide high-resolution real-time imaging of the gastrointestinal tract and surrounding extramural structures. EUS is an efficient and economical method for evaluating benign and malignant lesions of the gastrointestinal tract. Radial echo endoscopy is often used to evaluate subcutaneous lesions in the gastrointestinal tract[16]. In addition, GEP often shows umbilical depression on endoscopy. Chen et al[17] showed that 90% of cases with GEP show umbilicus-like depression. In a retrospective analysis of 44 patients by Yüksel et al[18], umbilicus-like depression was observed in 81.1% of patients, which was similar to our study. However, Park et al[8] observed umbilical-like depression only in 34.6% of cases, which may be related to their small sample size. With the rapid development of artificial intelligence, radiomics has become a study hotspot to establish predictive models and determine the type of gastric submucosal masses. Zhu et al[19] developed an artificial intelligence system extracting high-throughput features from endoscopic ultrasound images to establish predictive models that can accurately determine the type of submucosal tumors, including GIST, gastric leiomyomas, and GEP.

ESD is a new method of invasive endoscopic resection for superficial gastric cancers, but it is still in its exploratory stage for treating SMTs. Recently, several studies have shown that ESD is a promising minimally invasive technique for upper gastrointestinal submucosal tumors[20]. A prospective multicenter study in Japan with 57 patients who underwent ESD for submucosal gastrointestinal epithelial lesions showed that ESD can effectively treat submucosal gastrointestinal epithelial lesions[21]. Zhou et al[22] retrospectively analyzed 93 patients undergoing ESD of GEP. Among them, no patients experienced severe complications or recurrence, and ESD was a safe and feasible method for treating GEP. With the continuous progress in endoscopic technology and equipment in recent years, ESD has been applied for endoscopic resection of deep layers; however, it was accomplished under the guidance of experienced gastroenterologists[20].

GEP can also be treated using laparoscopic technology, which can be divided into two types: transgastric surgery and intragastric surgery[22]. Complete tumor resection is the preferred treatment method for SMTs, and several studies have confirmed the feasibility and safety of laparoscopic treatment for SMTs[11,23-25]. In our study, laparoscopic surgery also showed excellent performance, with no difference in surgical time, complications, or postoperative recovery time compared to ESD. Additionally, laparoscopic surgery was better for larger and deeper lesions, although it may result in higher costs. Recently, some studies have indicated that the combination of laparoscopy and endoscopy can become the standard treatment for SMTs[26]. The relatively small number of patients treated with laparoscopy in our study may be related to whether the patients were first visited by a surgeon or a gastroenterologist. Endoscopic resection is more likely to be chosen if a patient first visits the gastroenterology department.

Our study has several limitations. This was a single-center retrospective study with a nonrandomized design, which resulted in a small sample size due to the rarity of GEP. Few patients underwent LR in this study. Multicenter prospective studies are needed to compensate for these limitations.

CONCLUSION

Most cases of GEP originate from the submucosa in the gastric antrum and have hypoechoic features, internal pipe-like structures, and umbilicus-like depression. The treatment methods for GEP include ESD and LR, with comparable results. LR is better for large GEP originating from the muscularis propria or deeper layers.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Gastric ectopic pancreas (GEP) is a rare submucosal lesion that is usually difficult to diagnose histologically by biopsy, and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) has been used in the diagnosis of gastric submucosal tumors (SMTs). Surgical resection is the conventional standard strategy for the treatment of SMTs in the past, and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has become an important minimally invasive treatment technique. However, there is still a lack of studies on the two techniques for the treatment of GEP.

Research motivation

At present, most of the studies on GEP are limited to case reports, without large sample size reports, and its treatment has not been widely discussed.

Research objectives

The aim of this study was to describe the EUS features of GEP and to evaluate the value of laparoscopic resection (LR) vs ESD in the treatment of GEP.

Research methods

We retrospectively analyzed 49 patients with GEP who underwent lesion resection. The characteristics of EUS, clinical characteristics and the characteristics of the two treatment methods were analyzed.

Research results

Of the patients, 43 underwent ESD, and 6 underwent LR. GEP mostly originates from the submucosa, accompanied by umbilical depression, and often presents with abdominal pain as the first symptom. There was no significant difference in operative time, hospitalization time, hospitalization cost and time to resume eating between the two groups. LR was more prone to larger and deeper lesions, accompanied by more blood loss.

Research conclusions

GEP has significant characteristics under EUS. Both LR and ESD are good choices for the treatment of GEP.

Research perspectives

EUS can serve as a noninvasive technique for diagnosing GEP, and clinical doctors can choose ESD or LR based on the actual situation of the patient.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of The Second Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University.

Informed consent statement: As the study used anonymous and pre-existing data, the requirement for the informed consent from patients was waived.

Conflict-of-interest statement: We have no financial relationships to disclose.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: September 18, 2023

First decision: November 1, 2023

Article in press: November 26, 2023

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Martín Del Olmo JC, Spain; Popovic DD, Serbia S-Editor: Qu XL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yuan YY

Contributor Information

Hui-Da Zheng, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Quanzhou 362000, Fujian Province, China.

Qiao-Yi Huang, Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Quanzhou 362000, Fujian Province, China.

Yun-Huang Hu, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Quanzhou 362000, Fujian Province, China.

Kai Ye, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Quanzhou 362000, Fujian Province, China.

Jian-Hua Xu, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Quanzhou 362000, Fujian Province, China. xjh630913@126.com.

Data sharing statement

No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Barila Lompe P, Gine C, Laín A, Garcia-Martinez L, Diaz Hervas M, López M. Esophageal Atresia and Gastric Ectopic Pancreas: Is There a Real Association? Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2023 doi: 10.1055/a-2127-5672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu X, Wu X, Tuo B, Wu H. Ectopic pancreas appearing as a giant gastric cyst mimicking gastric lymphangioma: a case report and a brief review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21:151. doi: 10.1186/s12876-021-01686-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nambu N, Yamasaki T, Nakagomi N, Kumamoto T, Nakamura T, Tamura A, Tomita T, Miwa H, Shinohara H, Hirota S. A case of ectopic pancreas of the stomach accompanied by intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm with GNAS mutation. World J Surg Oncol. 2021;19:309. doi: 10.1186/s12957-021-02424-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodríguez-Seguel E, Villamayor L, Arroyo N, De Andrés MP, Real FX, Martín F, Cano DA, Rojas A. Loss of GATA4 causes ectopic pancreas in the stomach. J Pathol. 2020;250:362–373. doi: 10.1002/path.5378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trifan A, Târcoveanu E, Danciu M, Huţanaşu C, Cojocariu C, Stanciu C. Gastric heterotopic pancreas: an unusual case and review of the literature. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2012;21:209–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gottschalk U, Dietrich CF, Jenssen C. Ectopic pancreas in the upper gastrointestinal tract: Is endosonographic diagnosis reliable? Data from the German Endoscopic Ultrasound Registry and review of the literature. Endosc Ultrasound. 2018;7:270–278. doi: 10.4103/eus.eus_18_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka K, Tsunoda T, Eto T, Yamada M, Tajima Y, Shimogama H, Yamaguchi T, Matsuo S, Izawa K. Diagnosis and management of heterotopic pancreas. Int Surg. 1993;78:32–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park SH, Kim GH, Park DY, Shin NR, Cheong JH, Moon JY, Lee BE, Song GA, Seo HI, Jeon TY. Endosonographic findings of gastric ectopic pancreas: a single center experience. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:1441–1446. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Q, Chai N, Linghu E. A rare case of the pancreas with heterotopic gastric mucosa detected by EUS (with video) Endosc Ultrasound. 2020;9:410–412. doi: 10.4103/eus.eus_19_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirai K, Kuwahara T, Furukawa K, Kakushima N, Furune S, Yamamoto H, Marukawa T, Asai H, Matsui K, Sasaki Y, Sakai D, Yamada K, Nishikawa T, Hayashi D, Obayashi T, Komiyama T, Ishikawa E, Sawada T, Maeda K, Yamamura T, Ishikawa T, Ohno E, Nakamura M, Kawashima H, Ishigami M, Fujishiro M. Artificial intelligence-based diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal subepithelial lesions on endoscopic ultrasonography images. Gastric Cancer. 2022;25:382–391. doi: 10.1007/s10120-021-01261-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abe N, Takeuchi H, Ohki A, Hashimoto Y, Mori T, Sugiyama M. Comparison between endoscopic and laparoscopic removal of gastric submucosal tumor. Dig Endosc. 2018;30 Suppl 1:7–16. doi: 10.1111/den.13010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Catalano F, Rodella L, Lombardo F, Silano M, Tomezzoli A, Fuini A, Di Cosmo MA, de Manzoni G, Trecca A. Endoscopic submucosal dissection in the treatment of gastric submucosal tumors: results from a retrospective cohort study. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:563–570. doi: 10.1007/s10120-012-0225-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu S, Zhou X, Yao Y, Shi K, Yu M, Ji F. Resection of the gastric submucosal tumor (G-SMT) originating from the muscularis propria layer: comparison of efficacy, patients’ tolerability, and clinical outcomes between endoscopic full-thickness resection and surgical resection. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:4053–4064. doi: 10.1007/s00464-019-07311-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elwir S, Glessing B, Amin K, Jensen E, Mallery S. Pancreatitis of ectopic pancreatic tissue: a rare cause of gastric outlet obstruction. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2017;5:237–240. doi: 10.1093/gastro/gov037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu J, Wei G, Wang Y, Cai J. Multifeature Fusion Classification Method for Adaptive Endoscopic Ultrasonography Tumor Image. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2023;49:937–945. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2022.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sooklal S, Chahal P. Endoscopic Ultrasound. Surg Clin North Am. 2020;100:1133–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2020.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen SH, Huang WH, Feng CL, Chou JW, Hsu CH, Peng CY, Yang MD. Clinical analysis of ectopic pancreas with endoscopic ultrasonography: an experience in a medical center. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:877–881. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0476-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yüksel M, Kacar S, Akpinar MY, Saygili F, Akdoğan Kayhan M, Dişibeyaz S, Özin Y, Kaplan M, Ateş İ, Kayaçetin E. Endosonogragphic features of lesions suggesting gastricectopic pancreas: experience of a single tertiary center. Turk J Med Sci. 2017;47:313–317. doi: 10.3906/sag-1602-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu C, Hua Y, Zhang M, Wang Y, Li W, Ding Y, She Q, Zhang W, Si X, Kong Z, Liu B, Chen W, Wu J, Dang Y, Zhang G. A Multimodal Multipath Artificial Intelligence System for Diagnosing Gastric Protruded Lesions on Endoscopy and Endoscopic Ultrasonography Images. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2023;14:e00551. doi: 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He G, Wang J, Chen B, Xing X, Chen J, He Y, Cui Y, Chen M. Feasibility of endoscopic submucosal dissection for upper gastrointestinal submucosal tumors treatment and value of endoscopic ultrasonography in pre-operation assess and post-operation follow-up: a prospective study of 224 cases in a single medical center. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:4206–4213. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4729-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kobara H, Miyaoka Y, Ikeda Y, Yamada T, Takata M, Fujihara S, Nishiyama N, Fujita K, Tani J, Kobayashi N, Chiyo T, Yachida T, Okano K, Suzuki Y, Mori H, Masaki T. Outcomes of Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Subepithelial Lesions Localized Within the Submucosa, Including Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Multicenter Prospective Study. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2020;29:41–49. doi: 10.15403/jgld-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou Y, Zhou S, Shi Y, Zheng S, Liu B. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric ectopic pancreas: a single-center experience. World J Surg Oncol. 2019;17:69. doi: 10.1186/s12957-019-1612-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shoji Y, Takeuchi H, Goto O, Tokizawa K, Nakamura R, Takahashi T, Wada N, Kawakubo H, Yahagi N, Kitagawa Y. Optimal minimally invasive surgical procedure for gastric submucosal tumors. Gastric Cancer. 2018;21:508–515. doi: 10.1007/s10120-017-0750-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen SQ, Divino CM, Wang JL, Dikman SH. Laparoscopic management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:713–716. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0435-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang H, Huang X, Qu C, Bian C, Xue H. Comparison between laparoscopic and endoscopic resections for gastric submucosal tumors. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:245–250. doi: 10.4103/sjg.SJG_412_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuda T, Nunobe S, Kosuga T, Kawahira H, Inaki N, Kitashiro S, Abe N, Miyashiro I, Nagao S, Nishizaki M, Hiki N Society for the Study of Laparoscopy and Endoscopy Cooperative Surgery. Laparoscopic and luminal endoscopic cooperative surgery can be a standard treatment for submucosal tumors of the stomach: a retrospective multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2017;49:476–483. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-104526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No additional data are available.