Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, unique challenges for vulnerable and underserved minority communities in the United States emerged, including greater risk of severe COVID-19 illness,1 disproportionate hospitalizations and deaths,2 limited access to care,3 lack of reliable sources of information regarding risk and preventive behaviors,4 and mistrust of medical providers and COVID-19 messaging.4 The impact of COVID-19 and comorbidity disparities on African Americans in the South was particularly evident, with this region having the greatest prevalence of COVID-19 and the highest prevalence of chronic disease.5

Compounding these issues was ever-evolving information from government officials regarding safety measures, leading to miscommunication and decreased trust in government messaging.6 Social media disinformation piggybacked on the confusing information to further sow seeds of distrust in public health recommendations, such as masking, social distancing, and testing.7

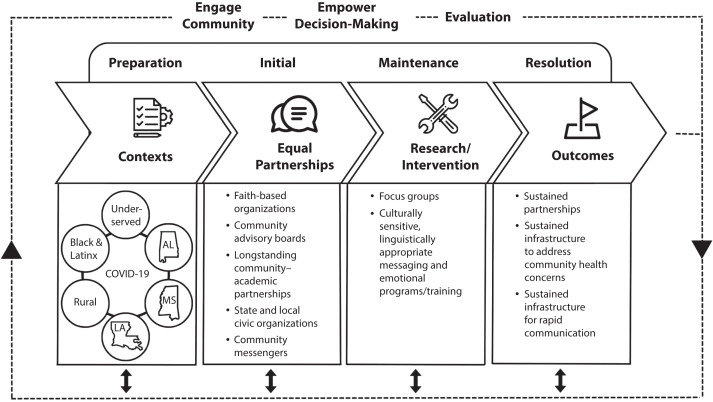

To address the crisis of inequities in COVID-19, it became clear that models embracing both engagement and action were needed to guide the development of timely, trustworthy messaging to vulnerable communities. A Bidirectional Collaborative Community Engagement Alliance (CEAL) Response Model (BCRM) emerged from the collaboration of teams in Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana that can be used to create culturally sensitive messaging and strategies to address health crises rapidly and effectively in vulnerable communities. Inherent in this model are sustained community‒academic partnerships.

CEAL TEAMS IN ALABAMA, MISSISSIPPI, AND LOUISIANA

The National Institutes of Health CEAL against COVID-19 Disparities was established early in the pandemic with a mission to “provide trustworthy, science-based information through active community engagement and outreach to the people hardest-hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, with the goal of building long-lasting partnerships as well as improving diversity and inclusion in our research …” Eleven state teams were initially funded to work with the communities hit hardest by COVID-19 with an additional 15 teams included in 2021 for a total of 26 CEAL teams nationwide. CEAL alliances in Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana were included in the first round of funding, and, because of our decades-long history of working together to eliminate health disparities in these southern states, we maintained close communication with each other regarding our common goals and methodologies.

Because of longstanding collaborations across three states based on mutual trust with vast networks of community partners, work could begin immediately to reduce the harm of COVID-19 in vulnerable communities. The overall goal of the southern CEAL teams was to incorporate community perspectives into the creation of COVID-19 mitigation strategies, integrating appropriate, culturally responsive messaging. To accomplish this, each of the CEAL teams employed a variety of community-engaged methodologies, including engaging community coalitions, community advisory boards, community scientific advisory boards, and community research teams; building teams collaboratively; holding town halls; and collecting data on community perspectives.

To understand community members’ perspectives, CEAL teams conducted focus-group discussions (FGDs) with participants recruited through a network of CEAL community partners and research teams in Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi. In each state, participants took part in online FGDs with trained, culturally concordant facilitators, utilizing semistructured discussion guides, with a goal to explore issues such as trusted sources of information; COVID-19 perceptions, knowledge, and behaviors; locale-specific social determinants of health; and perceived barriers and facilitators to vaccine uptake and clinical trial participation.

Between October 2020 and August 2022, a total of 56 FGDs were held. Participants across all three states (n = 498) were 73% female, 80% Black, 13% Latinx, and 10% White. Despite differences in geographic location and methodologies used, consistent themes emerged from FGDs including mistrust, fear, stigma, misinformation, and discrimination regarding COVID-19, all of which impacted willingness to practice prevention measures, to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, and to participate in a clinical trial. These themes informed the development, adaptation, and dissemination of interventions incorporating culturally sensitive, targeted messaging.

THE BIDIRECTIONAL CEAL RESPONSE MODEL

Given the rapidly changing landscape of COVID-19, our FGDs indicated that communities required almost instantaneous responses. Although each CEAL team applied the CBPR model8 for the basis of their partnerships, we realized that integrating principles of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Crisis Emergency Risk Communication (CERC) model9 (Figure 1) would enhance effectiveness. Emerging from this work was a newly developed model, the BCRM, which takes advantage of both models to create culturally sensitive messaging and strategies to address COVID-19 effectively and rapidly in vulnerable communities, and the model can be translated to other health crises.

FIGURE 1—

Bidirectional CEAL Response Model as Developed by the Southern CEAL Teams in Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana

Note. CEAL = Community Engagement Alliance.

CBPR includes structured mechanisms to ensure a fully participatory approach so community members and academic researchers can work collaboratively in ongoing partnerships.10,11 According to Wallerstein and Duran,8 the CBPR model consists of four components: (1) contexts, (2) group dynamics and equitable partnerships, (3) intervention or research, and (4) outcomes. Contexts are shaped by individual-, community-, and structural-level social determinants of health; community capacity; trust; and an overall understanding of the severity of health issues. Group dynamics are shaped by the intersection of individual and structural dynamics, which drive the negotiation of power between the partners working together. The intervention or research should be cocreated to incorporate the cultural norms, beliefs, and practices of the community for which the intervention is intended. Finally, outcomes should improve health by decreasing disparities while simultaneously increasing community empowerment. Perspectives gained from community collaboration using CBPR are ideal for engaging residents in power-sharing and capacity efforts in developing health interventions.11

CERC is the application of evidence-based principles to effectively communicate vital information to communities quickly; it is applicable in public health responses to health emergencies, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, to encourage public participation in disease prevention and containment. Its six principles are be first, be correct, be credible, express empathy, show respect, and promote action. CERC allows partners to rapidly refine messaging according to changing facts and community concerns and provide timely answers to those community questions. By leveraging resources to meet the needs of and advising regional decision-makers regarding vulnerable community members, messaging can have a powerful impact. However, without actively engaging communities in every step of the process, particularly health-disparate populations, CERC can have significant limitations. In fact, many COVID-19 CERC responses have not adequately included community voices in the creation and dissemination of risk communications, which perpetuated health disparities through a lack of inclusion and agency.12 By using the CERC model for the public health response with CBPR input, messaging is relevant to the communities’ risks and delivered in a way that is culturally sensitive and appropriately focused.

Overall, teams were able to utilize the BCRM approach to (1) identify culturally specific barriers to COVID-19 protective behaviors through FGDs, (2) harness community‒public health‒academic partnerships to create culturally specific messaging to mitigate the impact of COVID-19, and (3) utilize trusted leaders and other community stakeholders to educate and disseminate COVID-19 health communication. Foundational to this model is continuous engagement, based on CBPR principles, between established partners, so that when a crisis occurs, contextual factors can be quickly assessed, and culturally sensitive messaging can be deployed in a timely fashion.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Communication efforts and events, developed through integration of continuous community-engaged research, as illustrated in the newly created BCRM model, empowered communities, promoted trust, and combated misinformation while promoting vaccine confidence and clinical trial participation. Additional research can examine how this culturally based, sustainable model can be adapted to future health crises that disproportionately impact underrepresented populations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was, in part, funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) agreement OT2HL158287.

The authors would like to thank the many community, academic, and public health partners that make up the Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana CEAL teams. Without their help, this work would not be possible.

Note. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the NIH.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html

- 2.Mahajan UV, Larkins-Pettigrew M. Racial demographics and COVID-19 confirmed cases and deaths: a correlational analysis of 2886 US counties. J Public Health (Oxf). 2020;42(3):445–447. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blumenthal D, Fowler EJ, Abrams M, Collins SR. Covid-19—implications for the health care system. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1483–1488. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2021088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bateman LB, Schoenberger Y-MM, Hansen B, et al. Confronting COVID-19 in under-resourced, African American neighborhoods: a qualitative study examining community member and stakeholders’ perceptions. Ethn Health. 2021;26(1):49–67. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2021.1873250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parcha V, Malla G, Suri SS, et al. Geographic variation in racial disparities in health and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) mortality. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2020;4(6):703–716. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2020.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noar SM, Austin L. (Mis)communicating about COVID-19: insights from health and crisis communication. Health Communication. 2020;35(14):1735–1739. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2020.1838093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prasad A. Anti-science misinformation and conspiracies: COVID–19, post-truth, and science & technology studies (STS) Sci Technol Soc. 2021;27(1):88–112. doi: 10.1177/09717218211003413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(suppl 1):S40–S46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Center for Preparedness and Response. 2018. https://emergency.cdc.gov/cerc

- 10.Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel JG, Minkler M. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallerstein N, Oetzel JG, Sanchez-Youngman S, et al. Engage for equity: a long-term study of community-based participatory research and community-engaged research practices and outcomes. Health Educ Behav. 2020;47(3):380–390. doi: 10.1177/1090198119897075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gollust SE, Nagler RH, Fowler EF. The emergence of COVID-19 in the US: a public health and political communication crisis. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2020;45(6):967–981. doi: 10.1215/03616878-8641506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]