Abstract

Two studies of adult volunteers were performed to determine whether prior enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) infection confers protective immunity against rechallenge. In the first study, a naive control group and volunteers who had previously ingested an O55:H6 strain were fed an O127:H6 strain. In the second study, a control group and volunteers who had previously ingested either the O127:H6 strain or an isogenic eae deletion mutant of that strain were challenged with the homologous wild-type strain. There was no significant effect of prior infection on the incidence of diarrhea in either study. However, in the homologous-rechallenge study, disease was significantly milder in the group previously challenged with the wild-type strain. Disease severity was inversely correlated with the level of prechallenge serum immunoglobulin G against the O127 lipopolysaccharide. These studies indicate that prior EPEC infection can reduce disease severity upon homologous challenge. Further studies may require the development of new model systems.

Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) strains are one of several categories of pathogenic E. coli strains that cause diarrhea. EPEC infections are prevalent on six continents (5, 22–24, 28, 43). In many parts of the world, EPEC strains are the most common bacterial cause of diarrhea in infants (7, 21, 43). Disease due to EPEC can be severe, refractory to oral rehydration, protracted, and lethal (3, 14, 21, 45, 48).

The pathogenesis of EPEC infection involves three distinct stages, initial adherence, signal transduction, and intimate attachment (12). Initial adherence is associated with the production of a type IV fimbria, the bundle-forming pilus (BFP) (20), that is encoded on the large EPEC adherence factor (EAF) plasmid (50). EPEC uses a type III secretion apparatus to export several proteins, including EspA, EspB, and EspD, that are required for tyrosine kinase-mediated signal transduction within the host cell (17, 25, 30, 31). This signaling leads to phosphorylation and activation of a 90-kDa protein that is a putative receptor for the bacterial outer membrane protein intimin (44). Intimin, the product of the eae gene, is required for intimate attachment of bacteria to the host cell membrane and for full virulence in volunteers (13, 26, 27). The interaction between EPEC and host cells results in the loss of microvilli and the formation of adhesion pedestals containing numerous cytoskeletal proteins (16, 33, 34, 39, 46). This interaction between bacteria and host cells is known as the attaching and effacing effect (40).

One of the most striking clinical features of EPEC infections is the remarkable propensity of these strains to cause disease in very young infants. Rare reports of disease in older children and adults usually reflect common-source outbreaks that probably involve large inocula (47, 53). In contrast, in nosocomial outbreaks among neonates, EPEC spreads rapidly by person-to-person contact, apparently involving low inocula (54). The incidence of community-acquired EPEC infection is highest in the first 6 months after birth (4, 7, 21). EPEC infection is also more severe in younger children (8). Infants are more likely to develop diarrhea during the first episode of colonization with EPEC than they are during subsequent encounters (8). Whether the low incidence of EPEC diarrhea in older children and adults is due to acquired immunity or decreased inherent susceptibility is not known.

The immune response to EPEC infection remains poorly characterized. It has previously been demonstrated that volunteers convalescing from experimental EPEC infection develop antibodies to the O antigen component of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of the infecting strain, to intimin, and to type I-like fimbriae (13, 15, 29, 38). Antibodies to common EPEC O antigens are found more often in children of greater than 1 year in age than they are in younger children (42). Breast-feeding is protective against EPEC infection (2, 19, 43, 52). Breast milk contains antibodies against EPEC O antigens and outer membrane proteins and inhibits EPEC adherence to tissue culture cells (6, 9, 49).

In an earlier study, it was reported that volunteers infected with EPEC developed antibodies to a 94-kDa outer membrane protein (38). Subsequently, it was determined that this antigen was intimin (26). Interestingly, the lone volunteer in that earlier study who did not have diarrhea after challenge with a wild-type EPEC strain had prechallenge serum antibodies to intimin. This led to the hypothesis that antibodies to intimin are protective against EPEC infection. To test this hypothesis and to test the more general hypothesis that EPEC infection induces protective immunity, two volunteer studies were performed. The first was a heterologous-challenge study performed in 1986, in which volunteers were infected with an O55:H6 EPEC strain and challenged, along with a naive cohort, with an O127:H6 EPEC strain. The second was a homologous-challenge study performed in 1991, in which veterans of a study comparing the virulence of a wild-type EPEC O127:H6 strain with that of an isogenic eae mutant (13) were rechallenged, along with a naive cohort, with the homologous wild-type strain. The availability of new purified antigens allowed us to analyze data from these studies in the context of humoral immune responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

EPEC serotype O127:H6 strain E2348/69 and its isogenic eae deletion mutant strain CVD206 were described previously (11). E. coli 2362-75 is a serotype O55:H6 EPEC strain isolated from a 4-month-old infant in New Mexico and obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. E. coli 2362-75 is probe positive for the EAF plasmid and the eae gene and induces attaching and effacing lesions in tissue culture (1, 27). In a previous publication, this strain was erroneously reported to be of serotype O55:NM (1). The presence of H6 antigen was confirmed with specific antiserum. Strains were stored at −70°C until used.

Study design.

Two studies were performed. Study 1 (heterologous challenge) was designed to test the hypothesis that antibodies to a 94-kDa protein (now known to be intimin) are associated with protection against subsequent challenge with a heterologous EPEC strain that also expresses intimin. Study 2 (homologous challenge) was designed to test the following two hypotheses: previous EPEC infection confers protective immunity to subsequent homologous challenge, and an attenuated EPEC eae mutant protects against subsequent challenge with the wild-type strain. The following additional hypothesis was developed post hoc prior to performing serologic studies: an inverse association between the severity of disease and serum antibody titers to intimin and/or bundlin (the pilin protein of BFP) from the challenge strain exists. In addition, the hypothesis that an inverse association between the severity of disease and serum antibody titers to O127 LPS exists was generated after LPS titers were known.

The procedures for recruiting, screening, and obtaining informed consent from volunteers, which included passing a written examination to indicate a full understanding of the study design and the risks of the study, were described previously (13). Studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Maryland.

Volunteers were admitted to the research isolation ward of the University of Maryland Center for Vaccine Development. As in previous studies, the predefined primary end point was development of diarrhea, defined as the passage of two or more liquid stools within a 48-h period for a total of at least 200 g or the passage of a single liquid stool of 300 g or more. In addition, oral temperatures were recorded every 8 h and volunteers were questioned daily about the presence and severity of preselected symptoms, as previously described (13). Fever was defined as an oral temperature of ≥37.8°C. All stools were collected, cultured, and (if loose) weighed. Fluid losses were replaced by oral rehydration solution or, when necessary, intravenously. Volunteers in study 1 were treated with neomycin (500 mg orally every 6 h) for 5 days, beginning 96 h after challenge. Volunteers in study 2 were treated with ciprofloxacin (500 mg orally every 12 h) for 5 days, beginning 120 h after challenge.

In study 1, after a 48-h acclimatization period in the inpatient unit and a 90-min fast, volunteers ingested 1.6 g of sodium bicarbonate in 120 ml of water, followed immediately by an inoculum of either 9 × 108 (eight volunteers) or 1 × 1010 (nine volunteers) CFU of E. coli 2362-75 dissolved in 30 ml of water containing 0.4 g of sodium bicarbonate. Food and drink were prohibited for 90 min after ingestion of the inoculum. Twenty seven days after the first challenge, six naive volunteers (group 1) and eight veterans of the first challenge (group 2) ingested 1010 CFU of strain E2348/69 prepared as described above.

In study 2, a naive cohort (group 1; nine volunteers) and veterans from a previous study (13) who had received wild-type EPEC strain E2348/69 (group 2; seven volunteers) or eae mutant strain CVD206 (group 3; six volunteers) were recruited for challenge with the wild-type strain. Seventy days after the first challenge, these volunteers ingested 2.3 × 1010 CFU of E2348/69 prepared as described above.

Microbiology.

All stools were inoculated on eosin-methylene blue agar plates containing 100 μg of nalidixic acid per ml for quantitative culture. Ten colonies typical of E. coli were picked and tested by slide agglutination with serogroup-specific antiserum. Up to five EPEC colonies that had been confirmed by slide agglutination from each stool specimen were tested for the presence of the EAF plasmid with a specific DNA probe (41).

Serology.

Serum specimens were collected before challenge and 7, 14, and 28 days after challenge and stored at −70°C until assayed. All serum specimens were tested for antibodies to O127 LPS within 3 months of each study, and prechallenge and day 28 sera were tested for antibodies to intimin and bundlin after storage for 11 (study 1) or 5 (study 2) years. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgA antibodies in serum specimens were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as previously described (51). Polystyrene plates were coated with purified O127 LPS (50 ng/ml), a purified peptide containing 280 C-terminal amino acids of intimin from strain E2348/69 fused to an N-terminal histidine tag (5 μg/ml) (18), or a purified peptide containing prebundlin from strain E2348/69 fused to an N-terminal histidine tag (5 μg/ml) (55). Dilutions from 1:50 to 1:200 of control sera, obtained from 6-month to 1-year-old infants in another study, were tested to determine starting dilutions and cutoff optical densities for each antigen. Dilutions that yielded optical densities of between 0.1 and 0.3 for the mean plus 2 standard deviations of these control sera were selected. The minimum titer (starting at this dilution) of each volunteer serum sample required to exceed the cutoff value was recorded, and a fourfold increase in this titer was considered to be a significant response. The criterion for a significant rise in LPS titer in use in 1986 was different than that described above. Therefore, the O127 LPS response data from study 1 reflect the earlier method, in which sera were tested at a single dilution, determined from control sera as described above, and increases in optical density that were greater than an experimentally determined value (in this case, 0.1) were considered significant.

Statistical analysis.

Categorical variables, such as the attack rate of diarrhea, were compared by using Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were compared by using analysis of variance or Student’s t test. Correlations were evaluated by linear regression. A P value (two tailed) of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Clinical outcome. (i) Study 1.

After the initial challenge, diarrhea developed in one of eight volunteers who had ingested 9 × 108 CFU of O55:H6 EPEC strain 2362-75 and four of nine volunteers who had ingested 1010 CFU of strain 2362-75 (P = 0.29). Only two volunteers, one from each group, had fever. Eight veterans of the original challenge underwent a second challenge with heterologous O127:H6 EPEC strain E2348/69. Diarrhea developed in five of eight of these veterans and in four of six volunteers that had not been previously challenged (Table 1). There were no significant differences between the groups in the incidence of diarrhea; in the severity of diarrhea, as measured by weight or number of liquid stools; in the incubation period or duration of diarrhea; in the incidence of fever; or in symptoms. Among members of the veteran cohort, there was no difference in the incidence of diarrhea according to whether they had received a high or low inoculum during the first challenge or whether they had experienced diarrhea during the first challenge.

TABLE 1.

Summary of clinical data from volunteers who received O127:H6 strain E2348/69 and had not been previously challenged (group 1) or had previously received heterologous O55:H6 strain 2362-75 (group 2)

| Parameter (unit) | Value for:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | |

| No. of volunteers with diarrhea/no. challenged | 4/6 | 5/8 |

| Mean no. of liquid stools ± SD | 3.0 ± 3.0 | 6.1 ± 7.4 |

| Median wt (g) of liquid stools (range)a | 610 (285–1,326) | 881 (510–2,432) |

| Median duration (h) of diarrhea (range) | 15.2 (9.2–17.9) | 12.7 (9.7–41.1) |

| Mean incubation period (h)a ± SD | 9.1 ± 1.4 | 11.1 ± 6.9 |

| No. of volunteers with fever/no. challenged | 0/6 | 1/8 |

Among volunteers with at least one liquid stool.

(ii) Study 2.

Three volunteers, one from each group and one each because of fever, liquid stools, and the advice of a psychologist, were discharged prior to challenge. Of the volunteers that received the inoculum, diarrhea developed in seven of eight naive individuals (group 1), three of six previous recipients of the homologous wild-type strain (group 2), and four of five previous recipients of the eae mutant strain (group 3) (Table 2). The differences were not significant. There was no difference between the naive cohort and the previous recipients of the eae mutant strain in any clinical end point. However, previous recipients of the wild-type strain appeared to have less severe disease than did members of the naive cohort. In comparison to group 1 volunteers, group 2 volunteers tended to have a lower total stool weight, longer incubation period, shorter duration of diarrhea, lower incidence of fever, and lower maximum temperature. None of these differences were statistically significant. However, group 2 volunteers had significantly fewer liquid stools than did members of group 1 (P = 0.02). While there was no overall difference between groups in maximum temperature or incidence of fever, the mean temperature at 21 h after challenge was significantly different between groups (P = 0.016; one-way analysis of variance), with the naive group having a higher temperature (mean ± standard deviation, 37.5 ± 0.7°C) than that of group 2 (36.5 ± 0.4°C; P = 0.008) at this time point. This single temperature difference is notable, as this is the time point at which volunteers typically get fever after EPEC challenge (unpublished results) and this was the only time point at which temperatures differed among groups.

TABLE 2.

Summary of clinical data from volunteers who received O127:H6 strain E2348/69 and had not been previously challenged (group 1) or had previously received either the same strain (group 2) or eae mutant strain CVD206 (group 3)

| Parameter (unit) | Value for:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | |

| No. of volunteers with diarrhea/no. challenged | 7/8 | 3/6 | 4/5 |

| Mean no. of liquid stools ± SD | 9.0 ± 7.8 | 1.7 ± 1.5a | 2.6 ± 1.8 |

| Median wt (g) of liquid stools (range) | 781 (258–2,297) | 440 (71–958) | 709 (638–1,863) |

| Median duration (h) of diarrhea (range) | 11.6 (0–33.3) | 0 (0–6.7) | 10.5 (1.7–17.4) |

| Mean incubation period (h)b ± SD | 7.4 ± 1.4 | 8.6 ± 1.6 | 6.6 ± 0.7 |

| No. of volunteers with fever/no. challenged | 4/8 | 0/6 | 1/5 |

| Mean maximum temp (°C) ± SD | 37.9 ± 0.5 | 37.5 ± 0.2 | 37.4 ± 0.2 |

P = 0.02 versus the value for group 1.

Among volunteers with at least one liquid stool.

Microbiology.

The challenge organism was recovered from the stools of all volunteers in both studies. There were no differences between groups in either study in the colony counts of the challenge organism or in the proportion of volunteers with positive cultures for the challenge organism on any study day.

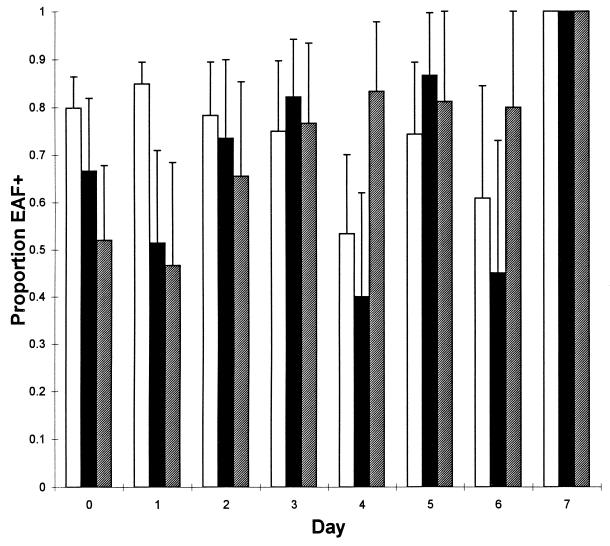

In the heterologous challenge, the percentage of fecal colonies that retained the EAF plasmid was significantly higher for group 1 (pooled percentage, 57.5%; 95% confidence intervals [CI], 50.9 to 64.9%) than for group 2 (pooled percentage, 42.6%; 95% CI, 37.2 to 48.8%). Similarly, in the homologous challenge, the proportion of fecal colonies that retained the EAF plasmid was significantly higher for group 1 (pooled percentage, 79.1%; 95% CI, 76.0 to 82.4%) than for either group 2 (pooled percentage, 66.4%; 95% CI, 60.7 to 72.6%) or group 3 (pooled percentage, 66.5%; 95% CI, 60.3 to 73.4%). This difference was apparent only early after challenge (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Proportion of colonies, obtained from the stools of volunteers in study 2, that retained the EAF plasmid. The proportion of colonies positive by colony blot hybridization for each volunteer was used to obtain a pooled proportion for each group. Error bars show the upper 95% CI for pooled proportions. Shown are data for the control cohort (group 1; open bars), the cohort that had previously ingested the homologous wild-type strain (group 2; solid bars), and the cohort that had previously ingested the eae deletion mutant (group 3; hatched bars).

Serology.

There was no difference between groups in response to O127 LPS, intimin, or bundlin in either study (Tables 3 and 4). Most volunteers in both studies developed significant serum IgG and IgA responses to O127 LPS, whereas few in either study responded to bundlin. Responses to intimin varied. More members of the naive cohort in the heterologous challenge responded to intimin than did previous recipients of either the wild-type or eae mutant strain, but the differences were not significant. As expected, volunteers from the homologous challenge who had previously ingested the wild-type strain had higher prechallenge titers to O127 LPS and bundlin than did members of the naive cohort. However, the titers against intimin were not significantly different.

TABLE 3.

Summary of serum immunoglobulin responses to selected antigens in volunteers who received O127:H6 strain E2348/69 and had not been previously challenged (group 1) or had previously received heterologous O55:H6 strain 2362-75 (group 2)

| Antigen and antibody | Group 1

|

Group 2

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of volunteers with response/no. tested | Antibody levela

|

No. of volunteers with response/no. tested | Antibody levela

|

|||

| Prechallenge | Postchallenge | Prechallenge | Postchallenge | |||

| O127 LPS | ||||||

| IgG | 3/6 | 0.05 | 0.37 | 5/8 | 0.06 | 0.31 |

| IgA | 4/6 | 0.00 | 0.57 | 3/8 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

| Intimin | ||||||

| IgG | 2/5 | 348 | 800 | 1/8 | 673 | 734 |

| IgA | 1/5 | 115 | 174 | 1/8 | 238 | 259 |

| Bundlin | ||||||

| IgG | 0/5 | 800 | 696 | 1/8 | 283 | 436 |

| IgA | 1/5 | 66 | 100 | 0/8 | 59 | 50 |

Data for responses to O127 LPS are expressed in mean optical density units; data for responses to intimin and bundlin are geometric mean titers.

TABLE 4.

Summary of serum immunoglobulin responses to selected antigens in volunteers who received O127:H6 strain E2348/69 and had not previously been challenged (group 1) or had previously received either the same strain (group 2) or eae mutant strain CVD206 (group 3)

| Antigen and antibody | Group 1

|

Group 2

|

Group 3

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of volunteers with response/no. tested | Antibody levela

|

No. of volunteers with response/no. tested | Antibody levela

|

No. of volunteers with response/no. tested | Antibody levela

|

||||

| Prechallenge | Postchallenge | Prechallenge | Postchallenge | Prechallenge | Postchallenge | ||||

| O127 LPS | |||||||||

| IgG | 4/8 | 27 | 183 | 2/6 | 252b | 566 | 3/5 | 33 | 152 |

| IgA | 7/8 | 19 | 673 | 6/6 | 63c | 283 | 5/5 | 33 | 606 |

| Intimin | |||||||||

| IgG | 3/8 | 336 | 734 | 0/6 | 356 | 504 | 1/5 | 230 | 400 |

| IgA | 4/8 | 92 | 200 | 0/6 | 89 | 112 | 1/5 | 152 | 230 |

| Bundlin | |||||||||

| IgG | 0/8 | 400 | 367 | 0/6 | 504 | 400 | 0/5 | 528 | 696 |

| IgA | 0/8 | 55 | 59 | 0/6 | 89d | 45 | 0/5 | 115 | 66 |

Data are geometric mean titers.

P = 0.004 versus result for group 1; P = 0.01 versus result for group 3.

P < 0.001 versus result for group 1.

P = 0.04 versus result for group 1.

When all volunteers from the heterologous challenge were considered together, there was a weak but statistically significant inverse correlation between prechallenge serum IgG titer to LPS and the severity of diarrhea, as measured by the total weight of liquid stools (r2 = 0.22; P < 0.05). A similarly weak relationship between prechallenge serum IgG titer to bundlin and disease severity was not significant (r2 = 0.19; 0.10 > P > 0.05). No such relationship existed between prechallenge titer to intimin and total stool weight.

There were significant inverse correlations between both prechallenge serum IgG to bundlin and prechallenge serum IgA to O127 LPS and the proportion of colonies recovered from stools that retained the EAF plasmid. These factors remained independently associated with EAF positivity by multiple linear regression analysis, accounting for a substantial degree of the variation in probe positivity (r2 = 0.43; P < 0.02).

DISCUSSION

Here we report the results of two studies designed to test the effect of previous EPEC infection on disease during subsequent challenge. To our knowledge, these are the first EPEC rechallenge studies reported. The first study was a heterologous challenge in which volunteers who had ingested an O55:H6 EPEC strain 27 days earlier, along with a naive cohort, were given an inoculum of an O127:H6 strain. The second study, a homologous challenge, had three groups, volunteers who had ingested the O127:H6 strain 70 days earlier, volunteers who had ingested an eae mutant of that strain 70 days earlier, and a naive cohort. There was no significant difference between groups in either study in the predefined primary end point, incidence of diarrhea. Thus, we failed to demonstrate that prior infection with either the same or a heterologous strain of EPEC protects against illness during subsequent infection.

While these studies failed to provide strong evidence of protective immunity against EPEC infection, they did not disprove the existence of such protection. Several factors may have limited our ability to detect an effect. The most obvious of these factors is insufficient sample size. Indeed, attrition and a lower-than-anticipated reenlistment rate of veteran volunteers resulted in very broad CI for the incidence of diarrhea in both studies. For example, in the homologous challenge, the 95% CI for the incidence of diarrhea in the naive group (47.3 to 99.7%) differed considerably from those of the group that had previously ingested the wild-type strain (11.8 to 88.2%). These intervals leave open the possibility of substantial protection. Unfortunately, a study with 80% power to determine whether the attack rates we observed in these groups (87 and 50%, respectively) represent a true difference would require 48 volunteers. Since our ward has only 32 beds, it is unlikely that we will be able to use this model to prove the existence of protective immunity against EPEC infection. Other factors that reflect the differences between experimental infection in adults and natural infection in infants also may have contributed to our inability to document protective immunity. We use a high inoculum in our experimental model because lower doses result in lower attack rates, which would necessitate huge studies to achieve adequate sample size, as demonstrated in the initial phase of the heterologous challenge reported here and in previous studies (15, 36). It is doubtful that natural infection in infants, which is spread from person to person, requires such a high inoculum (54). The results we obtained with EPEC stand in contrast to studies of protective immunity against infection with Shigella flexneri and Vibrio cholerae. Protection against reinfection with these natural pathogens of adults was easily demonstrated in volunteer studies whose sample sizes were comparable to those in the present report (35, 37).

Although we did not find evidence of protective immunity, we did find evidence of an effect of prior infection on disease severity. In the homologous-challenge study, veterans who had previously ingested the wild-type strain had significantly fewer liquid stools and significantly lower temperatures at 21 h after challenge (a time point at which most fevers occur in EPEC challenge studies) than did members of the naive cohort. Trends toward a lower total stool weight, longer incubation period, shorter duration of diarrhea, lower symptom score, and lower incidence of fever were also evident but were not statistically significant. Thus, we have demonstrated for the first time that prior EPEC infection reduces the severity of subsequent illness upon reinfection with the homologous strain. These results are compatible with observations made in longitudinal studies (8). However, we found no evidence of an effect of prior infection with a heterologous EPEC strain on disease severity. An analysis of the relationship between prechallenge antibody titers and stool weight revealed a weak but significant inverse correlation between levels of serum IgG to O127 LPS and disease severity. Since heterologous strains have different O antigens, this correlation is consistent with the lack of any effect of prior infection on disease severity in the first study. Thus, it appears that serum antibodies to the O antigen or an unknown factor that correlates with these antibodies provides protection against EPEC disease severity. This result confirms a long-standing hypothesis that antibodies to EPEC O antigens are associated with resistance to EPEC infection (42).

In a prior study, it was noted that the single individual with prior antibodies to intimin, as demonstrated by immunoblotting, was the only 1 of 12 recipients of the wild-type EPEC strain who did not have diarrhea (38). This observation led to the hypothesis that an immune response to intimin provides protection against subsequent disease. The results of the present studies by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, which is more quantitative than is immunoblotting, do not support this hypothesis. Not only did prior infection fail to prevent reinfection in this model, but there was no correlation between levels of intimin antibodies in serum and disease severity. Furthermore, the absence of any effect of prior infection with the eae mutant on subsequent disease upon challenge with the wild-type strain does not support the use of this attenuated strain that lacks intimin as a vaccine candidate.

As in previous studies (13, 38), we noted the curious propensity of the EAF plasmid, which encodes BFP, to be lost in a high proportion of colonies recovered from the stools of volunteers. In striking contrast, we estimated that the plasmid was lost in vitro under direct selective pressure (for the loss of a lethal marker) at a frequency of approximately 2 × 10−3 (unpublished observations). Although the number of volunteers with positive stool cultures for the challenge organism at later time points in the study was small, there was an interesting trend toward a higher proportion of EAF-positive colonies over time. Thus, it appears that strong selective forces are at work in vivo first against and then for possession of the EAF plasmid. The EAF plasmid may provide a selective advantage for long-term colonization so that bacteria that retain the plasmid and survive the initial selection against it, perhaps because of some sort of adaptation, have an eventual advantage over plasmid-cured organisms. Our results provide evidence for one selective force against the EAF plasmid, an immune response to bundlin, which is encoded on this plasmid. In both studies, the EAF plasmid was retained by a higher proportion of colonies cultured from the stools of volunteers in naive cohorts than from colonies cultured from the stools of groups that had undergone previous challenge. We noted a significant inverse association between prechallenge serum IgG titer to bundlin and the proportion of colonies recovered from stools that were EAF positive. There was also an independent association between serum IgA titer to O127 LPS and loss of the EAF plasmid, which is more difficult to explain, except as a surrogate marker for an immune response to an unknown antigen. Since an EPEC strain cured of the EAF plasmid is markedly attenuated in virulence (38), these observations suggest that an immune response to bundlin provides protection against EPEC disease in the naturally susceptible population.

In summary, we present the results of homologous- and heterologous-rechallenge studies of experimental adult EPEC infection. There was no evidence of protective immunity against heterologous challenge, but we found a significant effect of prior infection on the severity of illness upon reinfection with the homologous strain. Disease severity was weakly correlated with levels of antibody to the homologous O antigen. Future studies to explore the possibility of protective immunity against EPEC infection may require the development of new models. One possibility is the use of culture conditions that induce the expression of EPEC virulence factors, such as intimin, bundlin, and the Esp proteins, which are expressed better in tissue culture medium than in bacterial medium (10, 25, 32). Under such conditions, it may be possible to achieve high attack rates with lower inocula.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kathleen Palmer and Brenda Berger for volunteer recruitment, Mardi Reymann for technical assistance, clinical coordinator Sylvia O’Donnell, and the nursing staff of the research isolation ward. We are especially grateful to the volunteers for participating in these studies.

These studies were supported by Public Health Service awards N01 AI15096 and AI32074 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baldini M M, Nataro J P, Kaper J B. Localization of a determinant for HEp-2 adherence by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1986;52:334–336. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.1.334-336.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blake P A, Ramos S, Macdonald K L, Rassi V, Gomes T A T, Ivey C, Bean N H, Trabulsi L R. Pathogen-specific risk factors and protective factors for acute diarrheal disease in urban Brazilian infants. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:627–632. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.3.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bower J R, Congeni B L, Cleary T G, Stone R T, Wanger A, Murray B E, Mathewson J J, Pickering L K. Escherichia coli O114:nonmotile as a pathogen in an outbreak of severe diarrhea associated with a day care center. J Infect Dis. 1989;160:243–247. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatkaeomorakot A, Echeverria P, Taylor D N, Bettelheim K A, Blacklow N A, Sethabutr O, Seriwatana J, Kaper J. HeLa cell-adherent Escherichia coli in children with diarrhea in Thailand. J Infect Dis. 1987;156:669–672. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.4.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cobeljić M, Mel D, Arsić B, Krstić L, Sokolovski B, Nikolovski B, Sopovski E, Kulauzov M, Kalenić S. The association of enterotoxigenic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli and other enteric pathogens with childhood diarrhoea in Yugoslavia. Epidemiol Infect. 1989;103:53–62. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800030351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costa-Carvalho B T, Bertipaglia A, Solé D, Naspitz C K, Scaletsky I C A. Detection of immunoglobulin (IgG and IgA) anti-outer-membrane proteins of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) in saliva, colostrum, breast milk, serum, cord blood and amniotic fluid. Study of inhibition of localized adherence of EPEC to HeLa cells. Acta Paediatr. 1994;83:870–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cravioto A, Reyes R, Ortega R, Fernández G, Hernández R, López D. Prospective study of diarrhoeal disease in a cohort of rural Mexican children: incidence and isolated pathogens during the first two years of life. Epidemiol Infect. 1988;101:123–134. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800029289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cravioto A, Reyes R E, Trujillo F, Uribe F, Navarro A, De La Roca J M, Hernández J M, Pérez G, Vázquez V. Risk of diarrhea during the first year of life associated with initial and subsequent colonization by specific enteropathogens. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;131:886–904. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cravioto A, Tello A, Villafán H, Ruiz J, Del Vedovo S, Neeser J-R. Inhibition of localized adhesion of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to HEp-2 cells by immunoglobulin and oligosaccharide fractions of human colostrum and breast milk. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:1247–1255. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.6.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donnenberg M S, Girón J A, Nataro J P, Kaper J B. A plasmid-encoded type IV fimbrial gene of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli associated with localized adherence. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:3427–3437. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb02210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. Construction of an eae deletion mutant of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli by using a positive-selection suicide vector. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4310–4317. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4310-4317.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3953–3961. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.3953-3961.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donnenberg M S, Tacket C O, James S P, Losonsky G, Nataro J P, Wasserman S S, Kaper J B, Levine M M. The role of the eaeA gene in experimental enteropathogenic Escherichia coli infection. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:1412–1417. doi: 10.1172/JCI116717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fagundes Neto U, Ferreira V, Patricio F R S, Mostaço V L, Trabulsi L R. Protracted diarrhea: the importance of the enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) strains and Salmonella in its genesis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1989;8:207–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferguson W W, June R C. Experiments of feeding adult volunteers with Escherichia coli 111, B4, a coliform organism associated with infant diarrhea. Am J Hyg. 1952;55:155–169. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a119510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finlay B B, Rosenshine I, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. Cytoskeletal composition of attaching and effacing lesions associated with enteropathogenic Escherichia coli adherence to HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2541–2543. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2541-2543.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foubister V, Rosenshine I, Donnenberg M S, Finlay B B. The eaeB gene of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli is necessary for signal transduction in epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3038–3040. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.3038-3040.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frankel G, Phillips A D, Novakova M, Field H, Candy D C, Schauer D B, Douce G, Dougan G. Intimin from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli restores murine virulence to a Citrobacter rodentium eaeA mutant: induction of an immunoglobulin A response to intimin and EspB. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5315–5325. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5315-5325.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giles C, Sangster G, Smith J. Epidemic gastroenteritis of infants in Aberdeen during 1947. Arch Dis Child. 1949;24:45–53. doi: 10.1136/adc.24.117.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Girón J A, Ho A S Y, Schoolnik G K. An inducible bundle-forming pilus of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Science. 1991;254:710–713. doi: 10.1126/science.1683004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gomes T A T, Rassi V, Macdonald K L, Ramos S R T S, Trabulsi L R, Vieira M A M, Guth B E C, Candeias J A N, Ivey C, Toledo M R F, Blake P A. Enteropathogens associated with acute diarrheal disease in urban infants in Sao Paulo, Brazil. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:331–337. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gomes T A T, Vieira M A M, Wachsmuth I K, Blake P A, Trabulsi L R. Serotype-specific prevalence of Escherichia coli strains with EPEC adherence factor genes in infants with and without diarrhea in Sao Paulo, Brazil. J Infect Dis. 1989;160:131–135. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gunzburg S T, Chang B J, Burke V, Gracey M. Virulence factors of enteric Escherichia coli in young Aboriginal children in north-west Australia. Epidemiol Infect. 1992;109:283–289. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800050238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gurwith M, Hinde D, Gross R, Rowe B. A prospective study of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli in endemic diarrheal disease. J Infect Dis. 1978;137:292–297. doi: 10.1093/infdis/137.3.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jarvis K G, Girón J A, Jerse A E, McDaniel T K, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli contains a putative type III secretion system necessary for the export of proteins involved in attaching and effacing lesion formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7996–8000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jerse A E, Kaper J B. The eae gene of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli encodes a 94-kilodalton membrane protein, the expression of which is influenced by the EAF plasmid. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4302–4309. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4302-4309.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jerse A E, Yu J, Tall B D, Kaper J B. A genetic locus of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli necessary for the production of attaching and effacing lesions on tissue culture cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7839–7843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.7839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kain K C, Barteluk R L, Kelly M T, Xin H, Hua G D, Yuan G, Proctor E M, Byrne S, Stiver H G. Etiology of childhood diarrhea in Beijing, China. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:90–95. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.1.90-95.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karch H, Heesemann J, Laufs R, Kroll H P, Kaper J B, Levine M M. Serological response to type 1-like somatic fimbriae in diarrheal infection due to classical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Microb Pathog. 1987;2:425–434. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kenny B, Finlay B B. Protein secretion by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli is essential for transducing signals to epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7991–7995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kenny B, Lai L-C, Finlay B B, Donnenberg M S. EspA, a protein secreted by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC), is required to induce signals in epithelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:313–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knutton S, Adu-Bobie J, Bain C, Phillips A D, Dougan G, Frankel G. Down regulation of intimin expression during attaching and effacing enteropathogenic Escherichia coli adhesion. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1644–1652. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1644-1652.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knutton S, Baldwin T, Williams P H, McNeish A S. Actin accumulation at sites of bacterial adhesion to tissue culture cells: basis of a new diagnostic test for enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1290–1298. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1290-1298.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knutton S, Lloyd D R, McNeish A S. Adhesion of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to human intestinal enterocytes and cultured human intestinal mucosa. Infect Immun. 1987;55:69–77. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.1.69-77.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kotloff K L, Nataro J P, Losonsky G A, Wasserman S S, Hale T L, Taylor D N, Sadoff J C, Levine M M. A modified Shigella volunteer challenge model in which the inoculum is administered with bicarbonate buffer: clinical experience and implications for Shigella infectivity. Vaccine. 1995;13:1488–1494. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levine M M, Bergquist E J, Nalin D R, Waterman D H, Hornick R B, Young C R, Sotman S, Rowe B. Escherichia coli strains that cause diarrhoea but do not produce heat-labile or heat-stable enterotoxins and are non-invasive. Lancet. 1978;i:1119–1122. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)90299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levine M M, Black R E, Clements M L, Cisneros L, Nalin D R, Young C R. Duration of infection-derived immunity to cholera. J Infect Dis. 1981;143:818–820. doi: 10.1093/infdis/143.6.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levine M M, Nataro J P, Karch H, Baldini M M, Kaper J B, Black R E, Clements M L, O’Brien A D. The diarrheal response of humans to some classic serotypes of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli is dependent on a plasmid encoding an enteroadhesiveness factor. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:550–559. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.3.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manjarrez-Hernandez H A, Baldwin T J, Aitken A, Knutton S, Williams P H. Intestinal epithelial cell protein phosphorylation in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli diarrhoea. Lancet. 1992;339:521–523. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moon H W, Whipp S C, Argenzio R A, Levine M M, Giannella R A. Attaching and effacing activities of rabbit and human enteropathogenic Escherichia coli in pig and rabbit intestines. Infect Immun. 1983;41:1340–1351. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.3.1340-1351.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nataro J P, Baldini M M, Kaper J B, Black R E, Bravo N, Levine M M. Detection of an adherence factor of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli with a DNA probe. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:560–565. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.3.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neter E, Westphal O, Lüderitz O, Gino R M, Gorzynski E A. Demonstration of antibodies against enteropathogenic Escherichia coli in sera of children of various ages. Pediatrics. 1955;16:801–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robins-Browne R, Still C S, Miliotis M D, Richardson N J, Koornhof H J, Frieman I, Schoub B D, Lecatsas G, Hartman E. Summer diarrhoea in African infants and children. Arch Dis Child. 1980;55:923–928. doi: 10.1136/adc.55.12.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenshine I, Ruschkowski S, Stein M, Reinscheid D J, Mills S D, Finlay B B. A pathogenic bacterium triggers epithelial signals to form a functional bacterial receptor that mediates actin pseudopod formation. EMBO J. 1996;15:2613–2624. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rothbaum R, McAdams A J, Giannella R, Partin J C. A clinicopathological study of enterocyte-adherent Escherichia coli: a cause of protracted diarrhea in infants. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:441–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanger J M, Chang R, Ashton F, Kaper J B, Sanger J W. Novel form of actin-based motility transports bacteria on the surface of infected cells. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1996;34:279–287. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1996)34:4<279::AID-CM3>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schtoeder S A, Caldwell J R, Vernon T M, White P S, Granger S I, Bennett J V. A waterborne outbreak of gastroenteritis in adults associated with enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Lancet. 1968;i:737–740. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(68)92181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Senerwa D, Olsvik O, Mutanda L N, Lindqvist K J, Gathuma J M, Fossum K, Wachsmuth K. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli serotype O111:HNT isolated from preterm neonates in Nairobi, Kenya. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1307–1311. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.6.1307-1311.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silva M L M, Giampaglia C M S. Colostrum and human milk inhibit localized adherence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to HeLa cells. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1992;81:266–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1992.tb12219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stone K D, Zhang H-Z, Carlson L K, Donnenberg M S. A cluster of fourteen genes from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli is sufficient for biogenesis of a type IV pilus. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:325–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tacket C O, Moseley S L, Kay B, Losonsky G, Levine M M. Challenge studies in volunteers using Escherichia coli strains with diffuse adherence to HEp-2 cells. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:550–552. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.2.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taylor J, Powell B W, Wright J. Infantile diarrhea and vomiting: a clinical and bacteriological investigation. Br Med J. 1949;2:117–141. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4619.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Viljanen M K, Peltola T, Junnila S Y T, Olkkonen L, Järvinen H, Kuistila M, Huovinen P. Outbreak of diarrhoea due to Escherichia coli O111:B4 in schoolchildren and adults: association of Vi antigen-like reactivity. Lancet. 1990;336:831–834. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92337-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu S-X, Peng R-Q. Studies on an outbreak of neonatal diarrhea caused by EPEC 0127:H6 with plasmid analysis restriction analysis and outer membrane protein determination. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1992;81:217–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1992.tb12207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang H-Z, Donnenberg M S. DsbA is required for stability of the type IV pilin of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:787–797. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.431403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]