Abstract

The UDP-3-O-(R-3-hydroxyacyl)-N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase LpxC is an essential enzyme in the biosynthesis of lipid A, the outer membrane anchor of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and lipooligosaccharide (LOS) in Gram-negative bacteria. The development of LpxC-targeting antibiotics towards clinical therapeutics has been hindered by the limited antibiotic profile of reported non-hydroxamate inhibitors and unexpected cardiovascular toxicity observed in certain hydroxamate and non-hydroxamate-based inhibitors. Here, we report the preclinical characterization of a slow, tight-binding LpxC inhibitor, LPC-233, with low pM affinity. The compound is a rapid bactericidal antibiotic, unaffected by established resistance mechanisms to commercial antibiotics, and displays outstanding activity against a wide range of Gram-negative clinical isolates in vitro. It is orally bioavailable and efficiently eliminates infections caused by susceptible and multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial pathogens in murine soft-tissue, sepsis, and urinary tract infection (UTI) models. It displays exceptional in vitro and in vivo safety profiles, with no detectable adverse cardiovascular toxicity in dogs at 100 mg/kg. These results establish the feasibility of developing oral LpxC-targeting antibiotics for clinical applications.

One Sentence Summary:

We evaluated the preclincal efficacy and safety of an IV/IP and orally available LpxC-targeting antibiotic in vitro and in multiple animal models.

INTRODUCTION

Infections caused by multidrug-resistant bacterial pathogens pose serious threats to the public health and are associated with increasing morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs (1). The ESKAPE pathogens (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species) are prone to multidrug-resistant infection outbreaks (2). Recently, multidrug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae has emerged as yet another urgent threat (3). Despite the prevalence of Gram-negative pathogens among these bacterial threats, there has been no new class of antibiotics against Gram-negative pathogens developed in the past five decades. An effective therapeutic with a mode-of-action distinct from commercial antibiotics would provide the much-needed relief for treating multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections.

LpxC (UDP-3-O-(R-3-hydroxyacyl)-N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase) is an essential enzyme in the biosynthesis of lipid A, the hydrophobic anchor of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and lipooligosaccharide (LOS) and the major lipid component of the outer monolayer of the Gram-negative bacterial outer membrane (4, 5). Constitutive lipid A biosynthesis via the Raetz pathway is required for bacterial viability and fitness in the human host but has never been exploited by commercial antibiotics. As a result, LpxC has emerged as an attractive target for developing antibacterial agents against Gram-negative bacterial pathogens (6–10), though major hurdles remain due to the limited antibiotic profile of reported non-hydroxamate inhibitors (11, 12) and unexpected cardiovascular toxicity observed in a subset of hydroxamate and non-hydroxamate-based inhibitors (11, 13). Here we report the development and preclinical characterization of LPC-233, a low pM LpxC inhibitor with outstanding antibiotic activity against a wide range of Gram-negative bacteria in vitro. LPC-233 has clean safety profiles in vitro and in vivo, and it efficiently eliminates bacterial infections in various murine models when administered via intravenous (IV), intraperitoneal (IP) or oral (PO) routes.

RESULTS

Development and in vitro characterization of LPC-233

Following the structural elucidation of LpxC in complex with its substrate analog TU-514 and inhibitor CHIR-090 (14–16), we have conducted extensive structure-activity relationship analysis of LpxC inhibitors (17–19). We found that compounds containing a phenyl-diacetylene-based tail group generally display a broader spectrum of antibiotic activity than those that do not contain this tail group (17). We also developed potent LpxC inhibitors containing a β-difluoromethyl-allo-threonyl hydroxamate head group based on insights from structural and ligand dynamics analysis (19). Through evaluation of over 200 synthetic LpxC inhibitors containing these key features, we discovered a compound with a terminal cyclopropane group attached to the phenyl-diacetylene tail group (LPC-233, Fig. 1A), which displays outstanding antibiotic activities.

Fig. 1. Inhibition of LpxC by LPC-233.

(A) LPC-233 inhibits LpxC in lipid A biosynthesis in Gram-negative bacteria. (B) The crystal structure of the P. aeruginosa LpxC/LPC-233 complex reveals LPC-233 as a competitive inhibitor occupying the active site and substrate binding passage. The zoomed-in views of the interactions between the difluoromethyl-threonyl-hydroxamate group and active site residues as well as between the terminal cyclopropane group and hydrophobic residues at the exit of the substrate binding passage are shown in the lower and upper insets, respectively. (C) Time-dependent inhibition of LpxC by LPC-233. Fitting of time-dependent product accumulation curves of E. coli LpxC yielded KI=0.22 ± 0.06 nM and KI* = 8.9 ± 0.5 pM for the encounter complex EI and stable complex EI*, respectively. The conversion rate from EI* to EI was determined as k6=0.0058 ±0.0006 min−1, corresponding to an EI* half-life of ~2.0 hours.

LPC-233 has a molecular weight of 376 Da and can be manufactured through efficient synthesis to yield the enantiomerically pure product (Fig. S1). The compound is broadly effective against a clinical collection of 285 strains of Gram-negative bacterial pathogens (Tables 1). The MIC90 values of LPC-233 are generally below 1.0 μg/mL. LPC-233 does not display detectable antibiotic activity towards Gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus, at 128 μg/mL, consistent with its specific inhibition of LpxC in Gram-negative bacteria. Importantly, LPC-233 has an MIC50 value of 0.064 μg/mL and an MIC90 value of 0.125 μg/mL against 151 extended spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-negative, carbapenemase-negative Enterobacteriaceae isolates; and it displays identical MIC50 and MIC90 values against 42 ESBL, carbapenemase-producing isolates that are resistance to antibiotics. Similarly, there exists little difference in MIC50 and MIC90 values between susceptible and multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa strains. These observations reinforce the notion that as a compound with a different mode of action from commercial antibiotics, the antibiotic activity of LPC-233 against clinical strains is unaffected by established resistance mechanisms to commercial antibiotics.

Table 1.

MIC of LPC-233 against clinical strains of Gram-negative pathogens

| Organism | MIC (μg/mL) | |

|---|---|---|

| MIC50* | MIC90* | |

| E. coli (n=29); including 5 ESBL and 4 carbapenemase producers | 0.016 | 0.032 |

| Klebsiella (n=29); including 5 ESBL and 5 carbapenemase producers | 0.064 | 0.125 |

| Morganella (n=21); including 1 ESBL producer | 0.125 | 0.125 |

| Proteus (n=20) | 0.125 | 0.125 |

| Yersinia (n=20) | 0.064 | 0.125 |

| Citrobacter freundii (n=18); 2 ESBL and 5 carbapenemase producers | 0.032 | 0.125 |

| Citrobacter koseri (n=12) | 0.032 | 0.125 |

| Enterobacter (n=30); including 5 ESBL and 5 carbapenemase producers | 0.064 | 0.25 |

| Serratia (n=14); including 3 ESBL and 2 carbapenemase producers | 0.064 | 0.064 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n=37); 28 susceptible and 9 MDR/XDR strains | 0.25 | 1.0 |

| Achromobacter xylosoxidans (n=16) | 0.125 | 0.5 |

| Burkholderia cepacia (n=19) | 0.064 | 0.25 |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (n=16) | 0.25 | 1.0 |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae (n=4); 1 susceptible and 3 MDR strains | 0.016 | 0.063 |

| Staphylococcus aureus SA113 | >128† | |

| Enterobacteriaceae (151) ESBL & carbapenemase negative | 0.064 | 0.125 |

| Enterobacteriaceae (42) ESBL & carbapenemase positive | 0.064 | 0.125 |

| P. aeruginosa susceptible (28) | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| P. aeruginosa MDR/XDR (9) | 0.5 | 1.0 |

MIC50 and MIC90 values are defined as MIC values that inhibit 50% and 90% of the tested bacterial strains, respectively.

MIC.

Structural and enzymatic characterization of LPC-233

Structural analysis of LPC-233 in complex with P. aeruginosa LpxC shows that LPC-233 binds LpxC with its β-difluoromethyl-allo-threonyl hydroxamate head group in the active site and the phenyl-diacetylene cyclopropane group occupying the acyl-chain-binding passage (Fig. 1B; structural statistics summarized in Table S1). In the active site, the catalytic zinc ion is chelated by the hydroxamate group, which additionally forms hydrogen bonds with E77 and H264, two catalytically important residues. The two fluorine atoms of the difluoromethyl group form electrostatic interactions with K238, another essential residue of the LpxC catalysis. The threonyl methyl group forms a van der Waals (vdW) interaction with F191 of the hydrophobic cluster in the active site, and the hydroxyl group is solvent exposed. These active site interactions of LPC-233 are overall similar to the previously reported LpxC inhibitors in this series, such as LPC-058 and LPC-069 (19, 20). Importantly, the terminal cyclopropane group creates a kink of the linear tail group and naturally conforms to the L-shaped substrate passage by interacting with conserved hydrophobic residues lining at the exit of the substrate passage (M194, I197, V211 and V216; Fig. 1B). The cyclopropane group additionally contributes to the specificity of LpxC inhibitors by reducing the linearity and planarity of the tail group.

The ability of LPC-233 to inhibit LpxC catalysis was evaluated by enzymatic assays using the E. coli LpxC enzyme. The product accumulation in the presence of LPC-233 was nonlinear over time (Fig. 1C), suggesting that the compound inhibits LpxC in a time-dependent manner. Curve fitting of the time-dependent product accumulation using a competitive, slow-binding model shows that LPC-233 interacts rapidly with LpxC to form an “encounter” complex (EI) with an inhibition constant (KI) of 0.22 ± 0.06 nM. The EI complex then converts into a more stable, high-affinity complex, EI*. Once formed, the high-affinity EI* complex exhibits very tight binding, with an inhibition constant (KI*) of ~8.9 ± 0.5 pM and an EI*-to-EI reversion rate of 0.0058 ± 0.0006 min−1, corresponding to a half-life of ~2.0 hours for the EI* complex. Considering the rapid growth of Gram-negative bacteria, which typically double in less than one hour, the inhibition of LpxC by LPC-233 is essentially irreversible over the lifespan of individual bacterial cells.

Because LPC-233 harbors a metal-chelating hydroxamate group that could potentially inhibit human metalloenzymes, we investigated the inhibitory effect of LPC-233 against the Eurofins matrix metalloproteinase panel. We found that at a concentration of 30 μM, LPC-233 does not substantially inhibit (i.e. >30% inhibition) tested human matrix metallopeptidases (MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-8. MMP-9, MMP-12, MMP-13, and MMP-14) and TACE (Table S2). Considering the KI* value of ~8.9 pM of LPC-233 against LpxC, LPC-233 appears to be highly specific, with a selectivity of >3 × 106 fold towards LpxC over human metalloenzymes, such as MMPs and TACE.

Time-kill kinetics and resistance development

The time-kill kinetics of LPC-233 was evaluated at multiples of the MIC value using E. coli W3110, K. pneumoniae 10031, and P. aeruginosa PAO1 as model organisms (Fig. 2A). Exposure to LPC-233 at 2- to 8-fold MICs resulted in >100,000-fold of bacterial killing within 4 hours, indicating that LPC-233 is a rapidly bactericidal antibiotic for these strains (Fig. 2A). LPC-233 at concentrations of 4x MICs or higher completely suppressed any bacterial re-growth over a 24-hour period, indicating a lack of resistance accumulation. Indeed, measurements at drug concentrations of 8x MICs have revealed exceedingly low rates of spontaneous resistance mutations in these bacteria: 4.3 × 10−10 for E. coli, 1.4 × 10−9 for K. pneumoniae, and <2 × 10−10 for P. aeruginosa (Table 2). Sequencing of the isolated resistance colonies of E. coli invariably revealed spontaneous resistance mutations in the fabZ gene (Table S3). Such an observation is consistent with previous reports that mutation of fabZ is the most frequently isolated resistance mutants to LpxC inhibitors in E. coli and that resistance is achieved through rebalancing fatty acid and lipid A homeostasis by suppressing fatty acid biosynthesis for maintaining the bacterial envelope homeostasis (21, 22).

Fig. 2. Time killing kinetics and resistance accumulation of LPC-233.

(A) Time killing kinetics of LPC-233 against E. coli W3110, K. pneumoniae 10031, and P. aeruginosa PAO1. (B) Serial passage assay of LPC-233 and ciprofloxacin against E. coli W3110 and K. pneumoniae 10031.

Table 2.

Rates of Spontaneous Resistance Mutations to LPC-233 at 8x MIC

| Bacterial Strains | MIC (μg/mL) | Spontaneous resistance rate @ 8x MIC |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli W3110 | 0.01 | 4.3 × 10−10 |

| K. pneumoniae 10031 | 0.0026 | 1.4 × 10−9 |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1 | 0.125 | < 2 × 10−10 |

To evaluate the variation of spontaneous resistant mutation rates against LPC-233 in representative Gram-negative bacterial strains, we further tested seven E. coli isolates and six K. pneumoniae isolates that display varying degrees of resistance profiles to commercial antibiotics, including meropenem, levofloxacin, ceftazidime, and ceftazidime+avibatam (Table S4). The MICs of LPC-233 against these strains vary from 0.03 to 0.25 μg/mL. At 4x MICs, the spontaneous resistance rates varied from 4.2 × 10−8 to < 1.2 × 10−9, and at 8x MICs, the spontaneous rates all fell below 9.8 × 10−9.

The ability for bacteria to accumulate resistance to LPC-233 was evaluated in a serial passage assay using E. coli W3110 and K. pneumoniae 10031 strains (Fig. 2B). In this assay, surviving bacteria in the presence of sub-lethal concentrations (0.5 × MIC) of LPC-233 in the MIC measurements were selected, allowed to grow for 24 hours, and then subject to a new round of MIC measurements to evaluate how repeated exposure to LPC-233 results in resistance development and MIC elevation. This process was repeated 35 times, using the commercial antibiotic ciprofloxacin as the comparator. We found that resistance to LPC-233 developed with a rate similar to or marginally slower than that to ciprofloxacin for E. coli W3110 and K. pneumoniae 10031 strains (Fig. 2B), and the MIC values eventually plateaued at 1–2 μg/mL. A similar result was observed using the clinical isolate E. coli American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) 2522 (Fig. S2). Mass spectrometry analysis of the lipid A structure in E. coli W3110 at the initiation and conclusion of the serial passage assay did not reveal any difference, consistent with isolated resistance mutations in the fabZ gene in fatty acid biosynthesis (Fig. S3), but not in genes encoding lipid A modification enzymes. Taken together, these results suggest that rate of spontaneous resistance development to LPC-233, at a pace comparable to or slightly slower than the widely-used commercial antibiotic ciprofloxacin, should not pose a barrier to the progression of LPC-233 into clinical trials.

LpxC shifts the plasma protein binding equilibrium of LPC-233

We next evaluated whether the presence of plasma proteins could impact the potency of LPC-233. First, we measured the plasma protein-bound fractions of LPC-233 at 1, 3, and 10 μM concentrations using the rapid equilibrium dialysis (RED) method (Table 3). No concentration-dependent effect was observed for LPC-233. In general, LPC-233 existed predominantly in the plasma-bound state, with bound fractions varying from 96.4 ± 0.1% in mice, 98.9 ± 0.1 % in rats, 98.83 ± 0.04 % in dogs, 98.4 ± 0.1 % in monkeys, to 98.8 ± 0.1% in humans. Despite the observation that LPC-233 is highly plasma bound, the presence of plasma only modestly affected the MIC values of LPC-233 (Table 4). In the presence of 50% mouse plasma, the MIC increased from 0.014 μg/mL to 0.125 μg/mL for E. coli W3110, from 0.0025 μg/mL to 0.010 μg/mL for K. pneumoniae 10031, and from 0.122 μg/mL to 0.50 μg/mL for P. aeruginosa PAO1, resulting in a shift of MIC by 4- to 9-fold, which is much lower than the predicted ~30-fold shift if 96.4% of the compound were statically bound to the mouse plasma protein.

Table 3.

Percentage of plasma protein binding (fb%) of LPC-233

| CD-1 Mouse | Sprague-Dawley Rat | Beagle Dog | Cynomolgus Monkey | Human | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPC-233 1 μM | 96.3 ± 0.1% | 98.7 ± 0.1% | 98.8 ± 0.1% | 98.4 ± 0.1% | 98.6 ± 0.1% |

| LPC-233 3 μM | 96.2 ± 0.2% | 99.07 ± 0.01% | 98.89 ± 0.02% | 98.5 ± 0.1% | 98.8 ± 0.1% |

| LPC-233 10 μM | 96.7 ± 0.1% | 99.0 ± 0.1% | 98.76 ± 0.01% | 98.3 ± 0.1% | 98.84 ± 0.04% |

| LPC-233 Overall | 96.4 ± 0.1% | 98.9 ± 0.1% | 98.83 ± 0.04% | 98.4 ± 0.1% | 98.8 ± 0.1% |

| Warfarin 2 μM | ND | ND | ND | ND | 99.1 ± 0.1% |

Error represents S.E.M. (n=3); ND, not determined.

Table 4:

Effects of plasma on antibiotic activity of LPC-233 in vitro.

| CAMHB | CAMHB (50%) + Mouse Plasma (50%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (μg/mL) | MIC (μg/mL) | Fold increase | |

| E. coli W3110 | 0.014 ± 0.002 | 0.125 ± 0.000 | 9 |

| K. pneumoniae 10031 | 0.0025 ± 0.0004 | 0.010 ± 0.003 | 4 |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1 | 0.122 ± 0.008 | 0.500 ± 0.000 | 4 |

Error represents S.E.M. (n=3–14).

To understand the discrepancy between high plasma binding and the modest increase of MIC values in the presence of plasma samples, we repeated the plasma protein binding experiment by including E. coli LpxC in the buffer chamber. LPC-233 at a concentration of 10 μM (3.8 μg/mL) was added to the mouse plasma-containing chamber of the RED device, whereas purified E. coli LpxC at concentrations of 1, 5, and 9 μM (0.034, 0.17, and 0.31 mg/mL) was added to the buffer chamber. We found that even though LPC-233 was added to the plasma chamber, the presence of LpxC markedly enriched LPC-233 in the buffer chamber (Table S5), resulting in a notable increase of the buffer-to-plasma concentration ratio from a baseline level of 0.033 ± 0.001 in the absence of LpxC to 0.10 ± 0.03 and 0.21 ± 0.02 in the presence of 1 μM and 5 μM LpxC respectively. The presence of 9 μM LpxC in the buffer chamber further shifted the inhibitor distribution in such a way that a higher concentration of LPC-233 was observed in the buffer chamber instead of the plasma chamber, generating a buffer-to-plasma concentration ratio of 1.4 ± 0.1. Taken together, these results support the notion that the pM affinity of LpxC towards LPC-233 enables the enzyme to compete efficiently with plasma proteins for inhibitor binding and strip away the inhibitor from its plasma protein-bound form, which may mitigate the consequence of high plasma protein binding.

In vitro safety of LPC-233

Before moving into animal studies, we evaluated the safety of LPC-233 in vitro. Using the Promega® CellTiter-Glo assay, we found that 24-hour treatment of HEK293 cells with LPC-233 had limited effect on cell viability, with the lethal dose (50%) or LD50 value beyond 128 μg/mL (Fig. S4). Considering that the MIC90 values of LPC-233 fall below 1 μg/mL for most Gram-negative pathogens and that LPC-233 causes rapid bacterial killing within four hours of treatment, there is a high safety window (LD50/MIC90 > 100) of LPC-233 in vitro.

Seven-day repeat-dose toxicology in rats

The in vivo safety of LPC-233 was first evaluated through a maximum tolerated single dose (MTD) toxicity study in Sprague Dawley Rats. Four groups with 3 male and 3 female Sprague-Dawley rats per group were administered vehicle [40% (w/v) hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD)] or a single dose of LPC-233 at 0, 25, 80 and the maximum achievable dose of 250 mg/kg. Gross pathological examination of rats administered with vehicle and with LPC-233 did not reveal any abnormality of pathological significance. The safety of LPC-233 was then evaluated in a 7-day exploratory, non-GLP repeat IV dose study in rats. Four groups with 3 male and 3 female Sprague-Dawley rats per group were administered vehicle (40% w/v HPβCD in water), or LPC-233 at doses of 12.5, 40, and 125 mg/kg every 12 hours (Q12H; 25, 80, and 250 mg/kg/day), by IV injection via the tail vein for 7 consecutive days at a dose volume of 5 mL/kg. LPC-233 was generally well tolerated clinically with only a slight decrease in food consumption and slight, transient (days 1–4) loss of body weight observed at 250 mg/kg/day. No LPC-233-related adverse effects on clinical pathology, gross pathology, organ weights or histopathology (brain, spleen, liver, adrenals, kidneys, thymus, heart, lungs, testes, epididymis, and site of injection (tail)) were observed. Vacuolar changes in kidney (multifocal mild to moderate tubular vacuolation in cortex and medulla) and multifocal minimal to mild alveolar foam cells in lung were observed in both the vehicle control and high dose group animals, consistent with the known toxicity associated with cyclodextrins (23), and thus considered vehicle-related. Therefore, LPC-233 can be safely administered at 125 mg/kg/Q12H (250 mg/kg/day), the highest dose tested, for 7 consecutive days.

Pharmacokinetics in mouse, rat, and dog

The pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters of LPC-233 were evaluated in CD-1 mice, Sprague-Dawley rats, and beagle dogs. In general, a complex “multi-compartment” plasma PK profile was observed (the mouse plasma PK profile is shown in Fig. S5). Accordingly, a non-compartmental approach was used for modeling and PK parameter calculations (Table 5).

Table 5.

PK parameters of LPC-233 in mouse, rat, and dog

| Species | Admin. Route | Dose mg/kg |

a Cmax μg/mL |

AUCinf h*μg/mL |

T1/2 (Terminal) h |

bCL mL/min/kg |

Vc L/kg |

Fd (bioavailability) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse e | IV | 40 | 60.6 ± 5.0f | 24.8 ± 1.9 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 26.9 ± 2.0 | 7.7 ± 2.8 | - |

| Mouse g | IP | 40 | 17.9 ± 2.9 | 24.2 ± 3.2 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 27.9 ± 3.5 | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 98% |

| Mouse e | POfasted | 40 | 14.7 ± 2.7 | 18.2 ± 3.7 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 37.7 ± 7.5 | 8.9 ± 3.2 | 73% |

| Mouse e | POnot fasted | 40 | 3.0 ± 2.0 | 5.8± 2.5 | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 138 ± 80 | 32 ± 18 | 23% |

| Rat h | IV | 40 | 38 ± 6 | 24 ± 5 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 29 ± 6 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | - |

| Dog e | IV | 10 | 4.4 ± 0.2 | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 32 ± 1 | 4.0 ± 0.8 | - |

| Dog e | IV | 30 | 15.1 ± 1.9 | 19.4 ± 3.4 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 26 ± 5 | 3.4 ± 0.8 | - |

| Dog e | IV | 100 | 100 ± 10 | 141 ± 17 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 12 ± 2 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | - |

| Dog e | PO | 50 | 7.7 ± 2.5 | 19.4 ± 8.8 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 51 ± 27 | 8.5 ± 5.9 | 45%i (est.) |

For bolus IV: Cmax = C0 (conc. extrapolated to zero time, Tmax = 0)

Clearance, CL = CL/F for IP and PO routes

Volume of distribution, V = Vss for IV, V=Vz/F for IP and PO

Bioavailability, F = AUCORAL (or IP) /AUCIV at the same dose

n=3

single standard deviation

n=4

n=2

AUCIV (50 mg/kg) = 43 h*μg/mL was estimated from polynomial fit interpolation

To help interpret the observed multi-component decay of the plasma PK profile of LPC-233 in mice (Fig. S5), we additionally measured LPC-233 concentrations in representative organs (Fig. S5). We found that LPC-233 was rapidly enriched in kidney and liver, with their concentrations consistently higher (~4-fold higher) than the compound concentration in the plasma. The compound concentration in the muscle was lower than that in the plasma to start with, but it became higher than the plasma concentration after 30 minutes, suggesting that LPC-233 has higher affinities to tissues (kidney, liver, and muscle) than its affinities to plasma proteins. Despite the efficient binding of LPC-233 to plasma proteins, there is a dynamic equilibrium between tissues and plasma at all times. On the other hand, the compound concentration in brain tissues is considerably lower than the plasma concentration, reflecting a low penetration of blood-brain barrier. Considering the large percentage of muscle and other connective tissues in the body, it seems likely to that the initial drop of plasma drug concentration within first 2–3 hours reflects the drug redistribution to tissues, and that the body elimination process dominates at later times (Table 5).

The PK profiles of LPC-233 in rats and dogs are generally similar to these observed in mice (Table 5). The most notable observation is that clearance in dogs is not constant and decreases at high doses (Table 5). The consequence is that the AUC disproportionally increases with the increased dose (Table 5 and Fig. S6), an observation that needs to be considered in designing the dosing regimen.

In vivo efficacy

After determining that LPC-233 is well tolerated in vivo and has satisfactory half-lives in animals, we assessed the in vivo efficacy of LPC-233 in multiple murine infection models.

Efficacy of LPC-233 in a murine soft-tissue infection model against E. coli ATCC 25922

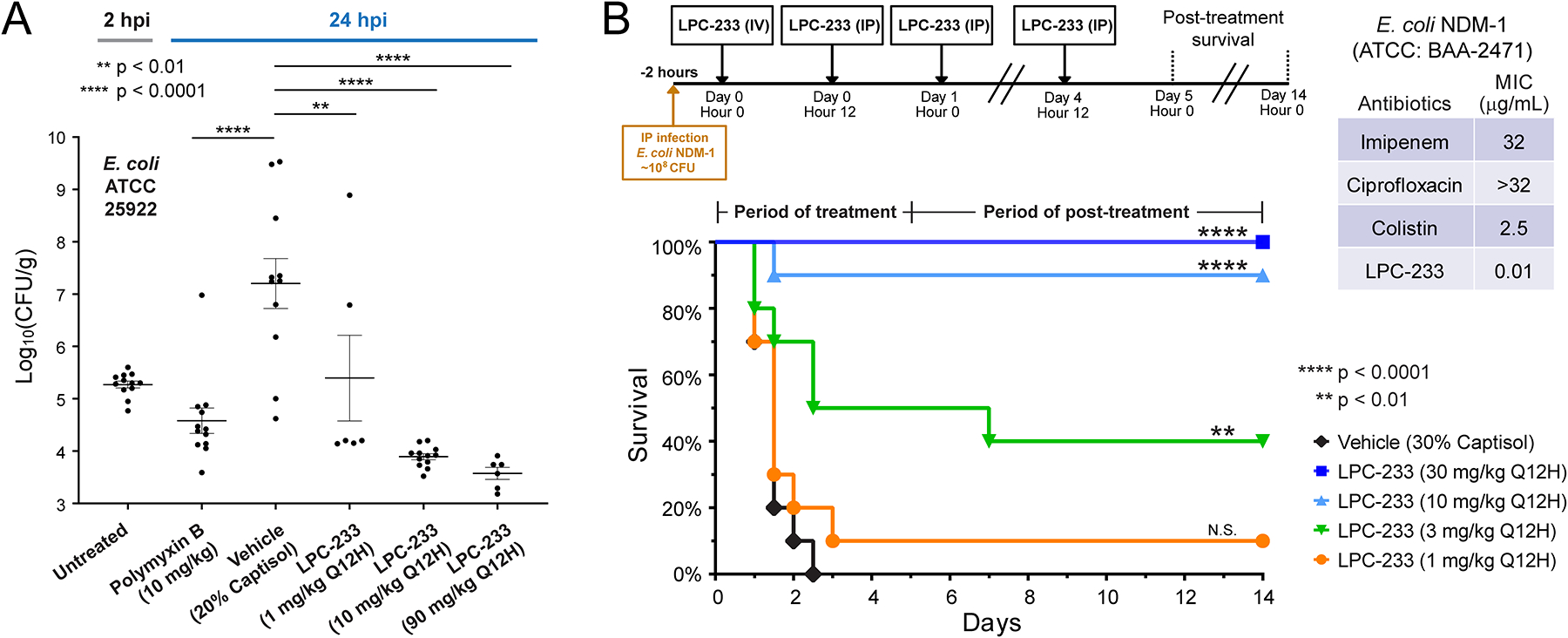

The ability of LPC-233 to clear bacterial infections was first evaluated in a murine thigh infection model. Female ICR mice were rendered neutropenic with cyclophosphamide and infected with 3.2 × 104 colony-forming units (CFU) of E. coli ATCC 25922 via an intramuscular injection. LPC-233 had an MIC of 0.02 μg/mL against this strain. Mice were either untreated or treated with vehicle (20% Captisol, Q12H), polymyxin B (10 mg/kg, Q24H; positive control), or LPC-233 at different doses (1, 10, or 90 mg/kg, Q12H) beginning 2 hours post-infection (hpi) via IV injection. Thigh tissues were harvested following euthanasia at either 2 hours (for the untreated group) or 24 hours (for treated groups including vehicle, polymyxin B, and different doses of LPC-233) post bacterial challenge. We found that LPC-233 dosed at as low as 1 mg/kg Q12H dramatically reduced the bacterial burden from that of the vehicle control group (Fig. 3A). The LPC-233 treatment at doses of ≥10 mg/kg Q12H lowered the bacterial burden below that of the polymyxin B (10 mg/kg, Q24H) positive-control group, demonstrating the outstanding efficacy of LPC-233 in mice.

Fig. 3. Efficacy of LPC-233 in murine thigh infection and sepsis models.

(A) Efficacy of LPC-233 in the murine thigh infection model. Neutropenic ICR female mice were challenged with E. coli ATCC 25922 of 4.5 log10 CFU via intramuscular (IM) injection in the right quadricep muscle. LPC-233 was formulated in the vehicle containing 20% Captisol. Treatments were administered at 2 hours (polymyxin B at 10 mg/kg) or at 2 and 14 hours (vehicle and LPC-233 at 1, 10, and 90 mg/kg) following challenge via IV injection. Untreated and treated thigh tissues were harvested at 2 and 24 hours post infection (hpi) respectively and bacterial burden per gram of tissue were determined. Statistical analysis: one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (n=6–12). **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001. (B) LPC-233 rescued mice infected with lethal doses of multidrug-resistant E. coli NDM-1. CD-1 mice were intraperitoneally inoculated with ~3 × 108 CFU of E. coli NDM-1. Two hours later, mice were given an IV injection of vehicle (30% Captisol) or LPC-233 at doses of 1, 3, 10, or 30 mg/kg. This was followed by a 4.5-day course of IP injections of vehicle or LPC-233 at the selected doses every 12 hours (Q12H). The survival of mice treated with vehicle, LPC-233 at 1 mg/kg, 3 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg and 30 mg/kg was recorded for the 5-day treatment period followed by a 10-day post-treatment period. Statistical analysis: P values were determined by using the Mantel-Cox log rank test (n=10; 5 male and 5 female). **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001; N.S., not significant.

LPC-233 protects mice from lethal infection by multidrug-resistant E. coli NDM-1

We next evaluated the ability of LPC-233 to rescue mice from the lethal infection by the multidrug-resistant E. coli strain NDM-1 (ATCC:BAA-2471) (Fig. 3B). The E. coli NDM-1 strain is resistant to imipenem (MIC=32 μg/mL), ciprofloxacin (MIC>32 μg/mL), and colistin (MIC=2.5 μg/mL), but is highly susceptible to LPC-233, with a MIC value of 0.01 μg/mL. In the murine sepsis model, mice were infected with ~3 × 108 CFU of E. coli NDM-1 via IP injection. Two hours after infection, mice were treated with vehicle (30% Captisol) or LPC-233 at 1, 3, 10 or 30 mg/kg Q12H for five days. As the bacteria were introduced via IP injection, the first drug injection was administrated via tail vein injection in order to mitigate the possibility of bacterial killing in the peritoneal space, whereas the remaining doses were delivered via IP injections. The mice were additionally observed for 10 days to ensure bacterial clearance and post-treatment animal survival. We found that all vehicle-treated mice died within 72 hours, whereas the groups treated with LPC-233 showed dose-dependent survival with a fitted ED50 value of 3.6 mg/kg Q12H (7.2 mg/kg/day). 90% of the mice treated with 10 mg/kg Q12H LPC-233 and all mice treated with 30 mg/kg Q12H of LPC-233 survived during the treatment and post-treatment observation periods, demonstrating that LPC-233 is highly efficacious against the multidrug-resistant E. coli NDM-1 infections in vivo. Considering the maximum feasible dose of 250 mg/kg/day and the ED50 of 7.2 mg/kg/day, LPC-233 has a therapeutic index of ~35 against the multidrug-resistant E. coli strain NDM-1.

Oral efficacy in a murine model of urinary tract infection

After demonstrating the in vivo efficacy of LPC-233 administered via IV and IP routes, we evaluated the oral availability of LPC-233. We compared the pharmacokinetics parameters of LPC-233 at a single dose of 40 mg/kg delivered via oral gavage (PO) with those of LPC-233 delivered via IV injection to CD-1 mice (Fig. 4A). Comparison of AUCPO/AUCIV indicated oral bioavailability of ~73% and ~23% under the fasted or unfasted conditions. LPC-233 is orally bioavailable in dogs as well, reaching ~45% under fasted conditions (Fig. S5 and Table 5). The high level of bioavailability of LPC-233 in multiple animal species suggests that LPC-233 would be well positioned for oral administration to both outpatients and inpatients.

Fig. 4. Oral bioavailability, tissue distribution, and efficacy of LPC-233 in a murine model of UTI.

(A) Oral availability of LPC-233. Comparison of LPC-233, formulated in 20% Captisol, delivered by oral gavage under overnight fasted or unfasted conditions and by IV shows oral bioavailability of 73% and 23% respectively. Error bars represent S.E.M. (n=3). (B) Bacterial load in kidneys (CFU/gram) from the murine model of UTI. Bacterial loads are plotted with the mean ± S.E.M. (n=9–10). Statistical analysis: one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. ****p <0.0001. (C) Detection of LPC-233 in the plasma and urine samples in mice at the end of the three-day treatment shows that LPC-233 is efficiently excreted through the urinary tract. Error bars represent S.E.M. (n=9).

Encouraged by this observation, we tested the oral efficacy of LPC-233 in a murine model of urinary tract infection (UTI) (Fig. 4B). Adult female C57BL/6 mice under inhaled anesthesia were inoculated with the E. coli uropathogenic strain CFT073 via the intra-urethral route. The MIC of LPC-233 against E. coli CFT073 was determined to be 0.02 μg/mL. Animals were divided into six groups, with individual groups receiving no treatment (untreated), vehicle (40% Captisol, administered via IV), ciprofloxacin (20 mg/kg; administered via subcutaneous (SC) injections twice daily (BID)), and LPC-233 administered via IV BID at 3 mg/kg or 30 mg/kg, or administered via oral gavage (PO) BID at 40 mg/kg. The treatment started 6 hours post infection. By the end of the 3-day treatment, the bacterial load in the kidneys of mice treated with LPC-233 at 3 mg/kg BID or higher was reduced > 1,000-fold from the untreated or vehicle groups, a therapeutic outcome comparable to that of the positive control group of 20 mg/kg BID ciprofloxacin. Impressively, treatment of mice with oral dosing of LPC-233 at 40 mg/kg BID completely eradicated the bacterial load, suggesting that oral LPC-233 can be an effective therapeutic solution for UTI. Analysis of murine plasma and urine samples in the 40 mg/kg PO group at the end of the three-day treatment period revealed the presence of LPC-233 at 7.4 ± 1.0 ng/mL in the plasma and 5.3 ± 0.7 ng/mL in the urine (Fig. 4C), suggesting that LPC-233 is efficiently excreted through the urinary tract.

LPC-233 displays no cardiovascular toxicity in vivo

Dose-limiting adverse cardiovascular effects (i.e. acute hypotension) hindered the development of the most advanced LpxC inhibitor ACHN-975 from Achaogen (13). In order to investigate whether LPC-233 could have a similar liability, we conducted the FASTPatch® hERG Assay (Charles River Laboratories, CRL) in vitro. The presence of LPC-233 did not result in substantial hERG ion channel current inhibition (< 5% inhibition) at tested concentrations (0.3, 1, 3, and 10 μM), whereas the positive control compound cisapride inhibited hERG channel (69 ± 4 % inhibition) at 0.05 μM (Table S6).

Encouraged by the lack of hERG inhibition, we evaluated the cardiovascular safety of LPC-233 in conscious beagle dogs. Three dogs with implanted sensors and a telemetry transponder received all three study treatments administered in a randomized crossover design according to the row of a Latin square. The treatments were normal saline, 40% Captisol w/v in normal saline (vehicle), and LPC-233 of 100 mg/kg infused over 60 minutes. Heart rate, blood pressure, and electrocardiograph were collected continuously from the beginning of the treatment infusion. During the entire observation window (Fig. 5), no notable difference was observed in any of the cardiovascular functions, including heart rate (HR), QTc, and mean arterial pressure (MAP), between the LPC-233 treatment group and either of the control groups (saline or vehicle), suggesting the LPC-233 can be safely administered to dogs without any detectable cardiovascular toxicities.

Fig. 5. Cardiovascular safety studies in dogs.

(A) Heart rates (HR), (B) QTc, and (C) mean arterial pressure (MAP) values are recorded from telemetry implanted conscious dogs following IV infusion of 100 mg/kg (human equivalent dose of 54 mg/kg) of LPC-233. The responses from saline, vehicle (40% Captisol), and LPC-233 in 40% Captisol are labeled in green, blue, and orange, respectively. The lower and upper 95% confidence levels of saline treatments are labeled (n=3). CI, confidence interval; UL, upper limit; LL, lower limit.

DISCUSSION

LpxC plays an essential role in lipid A biosynthesis and is an attractive target for developing effective therapeutics against multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Here, we report the preclinical characterization of a potent LpxC inhibitor, LPC-233, which is broadly effective against a wide range of Gram-negative pathogens, including multidrug-resistant strains, and displays outstanding antimicrobial activity in various animal models. Consistent with its target of LpxC in the lipid A biosynthetic pathway, the antibiotic activity is unaffected by target specific resistance mechanisms, and there is less than a 2-fold difference of the MIC50 and MIC90 values between the susceptible and multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas strains (Table 1). Furthermore, we measured the MIC values of LPC-233 against N. gonorrhoeae WT (FA19) and antibiotic-resistant strains (35/02, H041, and F89) that harbor well-characterized outer membrane protein (OMP) mutations in porB1b/penB (encoding the bacterial porin PorB1b) and mtrR (24–26). Mutations in porB1b/penB reduce the membrane permeability of antimicrobial compounds, whereas mutations in the promoter region of mtrR increase the expression of the MtrC-MtrD-MtrE efflux pump (24). These mutations shifted the MIC values of LPC-233 from 0.5- to 4-fold in comparison with the WT FA19 strain (Fig. S7), suggesting that they have a limited effect on the antibiotic activity of LPC-233.

Compared with other reported LpxC inhibitors, LPC-233 is attractive because of its high oral efficacy and efficient excretion in urine. Such properties render LPC-233 a highly effective antibiotic for combating multidrug-resistant UTIs, which are among the most frequent bacterial infections of the human hosts (27). Although the failure of ACHN-975, the most advanced LpxC inhibitor from Achaogen, in Phase I clinical trials has raised safety concerns about hydroxamate-containing LpxC inhibitors and has prompted the development of non-hydroxamate inhibitors (11, 12, 28), recent work from Achaogen demonstrated that replacement of the hydroxamate group with an amide group did not eliminate the cardiovascular toxicity, but substitution of the amino moiety in the head group of ACHN-975 improved the safety of the resulting LpxC inhibitors (13). Conversely, adverse cardiovascular effects have also been reported in non-hydroxamate LpxC inhibitors (11). These results argue that the cardiovascular toxicity is not unique to hydroxamate compounds but rather represents a compound-specific effect. In this regard, it is encouraging that LPC-233 at a concentration of 100 mg/kg in dogs did not show any noticeable difference of the heart rate, mean arterial pressure, or QTc values from the no-treatment group or vehicle control group, highlighting the cardiovascular safety of LPC-233 in vivo.

Several factors may have contributed to the distinct safety profile of LPC-233. LPC-233 contains a hydroxamate group, but no amino group, thus mitigating the amino-group-associated toxicity observed in ACHN-975 (13). Although substitution of the amino group in ACHN-975 reduced cardiovascular toxicity, this change also reduced the antibiotic activity (as reflected by increased MICs) (13). In contrast, LPC-233, despite its complete lack of any amino moiety, displayed outstanding enzymatic inhibition with a KI* value of ~ 8.9 pM and demonstrated potent antibiotic activity in vitro and in vivo. All of these factors contribute to an enhanced safety margin of LPC-233 in vivo.

LPC-233 is highly plasma bound, with the bound fractions (fb) varying from 96.4 ± 0.1% in mice to 98.8 ± 0.1 % in humans. The limited amount of unbound LPC-233 in the plasma may also contribute to the lack of cardiovascular toxicity. In contrast to the conventional wisdom that high-plasma protein binding limits the efficacy of the drug, we found that plasma binding had limited consequence on the antibiotic activity of LPC-233 in vitro and in vivo: the presence of 50% plasma samples from mice only modestly shifted the MIC values of LPC-233 by 4- to 9-fold when tested against E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and P. aeruginosa (Table 4); likewise, LPC-233 displayed outstanding efficacy in vivo, significantly reducing bacterial loads in the thigh infection model at a dosing level of 1 mg/kg. We reason that the lack of the plasma effect may be explained by the exceedingly tight binding affinity of LpxC towards LPC-233 (KI*=~8.9 pM), which, as demonstrated by the plasma protein binding experiment in the presence of LpxC, allows it to compete with plasma proteins for LPC-233 binding, efficiently stripping bound LPC-233 from plasma proteins (Table S5). Thus, the high percentage plasma binding property of LPC-233 may have provided a safety net to mitigate the potential side effect of LPC-233 without negatively affecting its antibiotic efficacy in vivo. Corroborating with our conclusion that high-plasma protein binding of LPC-233 does not disqualify it as a viable clinical candidate, a survey of U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs from 2003–2013 shows that 24% of the approved drugs have plasma-protein binding (PPB) exceeding 99% (29); likewise, a recent survey of 222 commercial drugs reveals that 15% of the drugs are highly plasma bound, with PPB of ≥99% (30).

Taken together, our investigations have established LPC-233 as a safe and effective clinical candidate. It is a slow, tight-binding inhibitor with a half-life for the stable enzyme-inhibitor complex (EI*) of ~2 hours, far exceeding the bacterial doubling time of 30–60 minutes. It has sub-μg/mL MIC90 against susceptible and multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens and is rapidly bactericidal. It has in vitro therapeutic indices exceeding 100:1 for most Gram-negative bacteria. It has low spontaneous resistance mutation rates (~10−8-10−10 for E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and P. aeruginosa). It displays no inhibition of hERG at 10 μM, no inhibition of the tested human metalloenzymes such as TACE and MMPs at 30 μM, and no adverse cardiovascular toxicity as measured by continuous electrocardiogram (ECG), blood pressure, and heart rate monitoring in dogs at 100 mg/kg. It has a favorable half-life of 1.0–1.6 hours for IV administration in mice, rats, and dogs, and 1.8–3.0 hours for oral administration in mice and dogs, respectively. Treatment with LPC-233 at as low as 1 mg/kg Q12H results in a significant reduction of the bacterial load in the murine thigh infection model, and it efficiently rescues mice infected with a lethal dose of NDM-1, a clinical isolate of multidrug-resistance E. coli, with a fitted ED50 value of 3.6 mg/kg Q12H (7.2 mg/kg/day) and a corresponding therapeutic index of ~35. Most excitingly, it has high oral bioavailability (73% under fasted conditions), and an oral dosage of 40 mg/kg Q12H completely clears the bacterial infection in a murine UTI model. These promising properties render LPC-233 an attractive candidate for further development toward clinical trials. As our studies were conducted in rodents and dogs, future studies will be required to determine the compound efficacy, PK, and safety, in particular cardiovascular safety, in human patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The overall objective was to evaluate the in vitro and in vivo efficacy and safety of the LpxC-targeting antibiotic LPC-233. We investigated the antibiotic activity of LPC-233 against clinical strains, determined its crystal structure in the LpxC-bound complex, and characterized its time-dependent inhibition of LpxC, bacterial killing kinetics, resistance development, plasma protein binding and in vitro and in vivo safety, including cardiovascular safety. We demonstrated its outstanding in vivo efficacy in multiple disease models. All in vitro measurements were performed with duplicate, triplicate, or more independent measurements, and all animal studies used six or more animals per dosing group.

All in vivo experiments were performed following the guideline of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Animals were randomized before each experiment, but investigators were not blinded to group allocation. Sample sizes were determined on the basis of prior studies to achieve statistical significance. Unless noted otherwise (i.e., human errors causing clinical signs unrelated to the drug treatment or a lack of bacterial infection) in the source data, all measurements are included for analysis. The health status of animals was monitored daily, and animals met predefined study endpoints were euthanized humanely.

Synthesis of LPC-233

Procedures for synthesizing LpxC inhibitors containing a difluoromethyl-allo-threonyl hydroxamate head group (19, 31) were adapted for the synthesis of LPC-233 (Fig. S1 and Supplementary Materials).

MIC of LPC-233 against clinical strains

MIC values of LPC-233 against 285 non-duplicated Gram-negative clinical isolates and four N. gonorrhoeae strains were determined using agar dilution methods as described by the Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (32) and by Ropp et al. (33). The protocol to determine the MIC value of LPC-233 in the presence of 50% mouse plasma was adapted from the CLSI broth microdilution method (32). Details of the bacterial strains and MIC measurements are described in Supplementary Materials.

Crystallography

P. aeruginosa LpxC (PaLpxC; 1–299, C40S) was prepared as previously reported (18, 19). Diffraction quality crystals were obtained using the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method by mixing 1 μL of the protein-inhibitor solution [0.3 mM protein and 1.2 mM LPC-233, 25 mM HEPES pH 7.1, 50 mM NaCl, and 2 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP)] with 1 μL of the reservoir solution containing 0.17 M sodium acetate, 0.085 M Tris HCl pH 8.5, 25.5% PEG 4000, 15% glycerol, and 0.01 M calcium chloride. Crystals were cryoprotected using 20% ethylene glycol in the mother liquor solution before flash-freezing. Effort to obtain the E. coli LpxC/LPC-233 complex crystals did not yield diffracting crystals. Details of X-ray diffraction data collection, processing, and model building are described in Supplementary Materials.

Enzymatic assays

Enzymatic assays for LpxC inhibition by LPC-233 followed reported procedures (19) with details described in Supplementary Materials.

Time-kill kinetics and resistance development

For time-kill kinetics, individual colonies of each target strain (E. coli W3110, K. pneumoniae 10031, or P. aeruginosa PAO1) were selected and grown to OD600 (optical density at 600 nm) = 1.0 prior to 1,000x dilution into 20 mL of LB medium containing 1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and 0x, 0.5x, 1x, 2x, 4x, 8x, or 16x MIC of LPC-233. The cultures were then grown at 37 °C for 24 hours. Aliquots were taken from each sample at various time points between 0.5 and 24 hours and diluted in LB medium in serial 1:10 dilutions. 5 μL droplets of each sample and its serial dilutions were spotted on LB agar plates and incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours. The CFU/mL was calculated from the lowest dilution that maintained countable, individual colonies. Spontaneous resistance measurements followed published procedures (21) with details in Supplementary Materials.

Serial passage assay

E. coli W3110, ATCC 25922, and K. pneumoniae 10031 strains were grown overnight in LB medium at 37 °C and diluted to OD600 = 0.6 in LB. The MIC determination followed the micro-dilution susceptibility test protocol (32) in the 96-well format, with each well containing 1:100-fold dilution of the bacterial cells, 100 μL Cation-Adjusted Mueller–Hinton Broth (CAMHB) medium, and serial two-fold dilutions of LPC-233. After incubation of 22 hours at 37 °C, 5 μL aliquots from individual wells were transferred to a fresh 96-well plate. 10 μL of 5 mg/mL MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) was added to each well and incubated for 3 hours at 37 °C before addition of 100 μL isopropanol with 0.1 N HCl. The MIC is the lowest drug concentration of the wells with (O.D.570nm – O.D.590nm) below 3 folds of standard deviation of no bacteria controls. The saved aliquot corresponding to the 0.5x MIC well was used to inoculate a tube with fresh LB medium for overnight growth at 37 °C. The same procedure was repeated to determine the MIC of the next passage.

Lipid A extraction and analysis using LC/ESI-MS

To evaluate whether acquired resistance during serial passages could be caused by lipid A modification, lipid A was extracted from E. coli W3110 prior to and after serial passages following established procedures (34) and analyzed by LC/ESI-MS as described in the Supplementary Materials.

In vitro protein binding determination in mouse, rat, dog, monkey, and human plasma

The plasma protein binding study was conducted by QPS, LLC following established protocols in Supplementary Materials.

LPC-233 cell viability assay

HEK-293 cells were added to a 96-well plate (1,000 cells/well) and given 24 hours to adhere. LPC-233 was then added by a serial dilution from 128 μg/mL to 0.5 μg/mL. After 24-hour treatment, cell viability was measured using the CellTiter-Glo® 2.0 cell viability assay kit (Promega).

Inhibition of human MMPs and TACE

In vitro inhibition of human matrix metallproteinases (MMPs) and Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Converting Enzyme (TACE) by LPC-233 at 30 μM was conducted by Eurofins following company protocols.

hERG inhibition assay

The hERG inhibition assay was conducted by CRL following company protocols. The test article, LPC-233, was evaluated at 0.3, 1, 3 and 10 μM. Cisapride was used as the positive control.

Maximum tolerated single and repeat doses

The maximum tolerated IV single dose (25, 80 and 250 mg/kg) and repeat dose (12.5, 40, and 125 mg/kg Q12H for 7 days) toxicology were measured in Sprague-Dawley rats (6 to 8 weeks). Procedures and clinical observations are included in Supplementary Materials and Source Data.

In vivo pharmacokinetics (PK) studies in mouse, rat, and dog

The LPC-233 concentration in plasma and tissue following drug treatment was measured by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS; details of sample collection and LC/MS/MS analysis are described in Supplementary Materials). The concentration/time data were used to estimate PK parameters by utilizing the non-compartmental approach (35) within the WinNonlin software (version 2.1, Pharsight). AUC was calculated by numerical integration, Cmax (IV) estimated by back-extrapolation to time zero, half-life of terminal process calculated from the slope of the last 2–3 time-points.

Efficacy of LPC-233 in a murine thigh infection model

ICR female mice (3 to 4 weeks; Envigo) were rendered neutropenic through cyclophosphamide injections. Mice were challenged with ~3.2 × 104 E. coli (ATCC 25922) via intramuscular (IM) injections in the right quadricep muscle. Treatments (polymyxin B at 10 mg/kg, vehicle containing 20% Captisol, and LPC-233 at 1, 10, and 90 mg/kg) were administered at 2 and 14 hours following bacterial challenge via IV injection. Thigh tissues were harvested at 24 hours after the challenge, and bacterial burden per gram of tissue determined. Polymyxin B, not a stand-of-care antibiotic but often employed as the last-line-of-defense treatment, is used as the positive control.

Efficacy of LPC-233 in an E. coli sepsis model

Each CD-1 mouse (6 to 8 weeks) was injected with 3 × 108 E. coli NDM-1 strain (ATCC BAA-2471) via IP. Each group contained 10 mice (5 male and 5 female). Two hours after infection, 150 μL of vehicle (30% Captisol dissolved in saline) or LPC-233 in 30% Captisol at specified concentrations was injected via IV. Twelve hours later, 200 μL of vehicle or LPC-233 solutions at desired concentrations were administrated via IP injections every 12 hours (Q12H) for a total of nine injections. The mice were monitored for additional 10 days and the percentages of survival recorded.

Efficacy of LPC-233 in a UTI model

Female C57BL/6 mice (7 to 8 weeks) were randomly allocated to experimental groups (n=10 per group). On day 0, mice had their drinking water removed 2 hours pre- and post-infection. Before inoculation of bacteria, bladders were emptied by gentle abdominal massage. Mice were inoculated with E. coli uropathogenic strain CFT073 via the intraurethral route while under inhaled anesthesia. Mice were either untreated or treated with vehicle (40% Captisol, BID), ciprofloxacin (20 mg/kg, sub-cutaneous BID), or LPC-233 at 3 mg/kg (IV BID), 30 mg/kg (IV BID), or 40 mg/kg (PO BID). The treatments started 6 hours after infection and ended by day 3. All animals were sacrificed on day 3. At termination, kidneys were dissected out and processed for CFU determination. Terminal blood and urine samples were collected and stored at −80 °C for LC/MS analysis.

Cardiovascular toxicity in dogs

Three non-naïve conscious beagle dogs (male, 19 to 27 months) outfitted for telemetry measurement were used to evaluate potential cardiovascular toxicity of LPC-233. Each dog received each of 3 treatments in a random sequence determined for the row of a Latin square. The 3 treatments administered as 5 mL/kg over 60 minutes were normal saline, 40% Captisol (w/v) in normal saline, and 20 mg VB-233/mL of 40% Captisol in normal saline. ECGs, hemodynamic measurements, and body temperature were measured from the beginning of the infusion through 24 hours by a specialist trained in electrocardiography and cardiovascular safety pharmacology.

Statistics

Data plotting and statistical tests were performed in GraphPadPrism version 9.4.1. Statistical parameters such as mean ± S.E.M. are indicated in the figure legends. In the graphs, asterisk and letters indicate statistical significance tests by analysis of variance (ANOVA). Numbers of biological replicates are indicated for all data points in figure captions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

X-ray diffraction data were collected at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beamline 24-ID-E, funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (Grant P30 GM124165). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a US Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by the Argonne National Laboratory under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357.

FUNDING

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health R01 GM115355 to P.Z., AI094475 to P.Z. and R.A.N., AI152896 to C.D., AI148366 to Z.G., NCBiotech Grant (2016-TEG-1501), the Duke CTSI Accelerator Fund, and the Duke University School of Medicine Bridge Fund and to P.Z. The Duke PK/PD Core Laboratory, directed by I.S., is supported by the National Cancer Institute Comprehensive Cancer Center Core Grant P30CA014236.

COMPETING INTERESTS

P.Z., E.J.T., and R.A.N. are co-inventors of a patent covering LPC-233, which has been licensed by Valanbio Therapeutics. P.Z, and E.J.T. are co-founders of Valanbio Therapeutics. C.D. and R.G. are CEO and COO of Valanbio Therapeutics. P.Z., E.J.T., and C.D. have stock options from Valanbio Therapeutics. V.G.F. reports personal fees from Novartis, Debiopharm, Genentech, Achaogen, Affinium, Medicines Co., MedImmune, Bayer, Basilea, Affinergy, Janssen, Contrafect, Regeneron, Destiny, Amphliphi Biosciences, Integrated Biotherapeutics, C3J, Armata, Valanbio; Akagera, Aridis, Roche; grants from NIH, MedImmune, Allergan, Pfizer, Advanced Liquid Logics, Theravance, Novartis, Merck; Medical Biosurfaces, Locus; Affinergy; Contrafect; Karius; Genentech, Regeneron, Deep Blue, Basilea, Janssen; Royalties from UpToDate, stock options from Valanbio and ArcBio, Honoraria from IDSA of America for his service as Associate Editor of Clinical Infectious Diseases, and a patent on sepsis diagnostics pending.

Footnotes

List of Supplementary Materials

DATA AND MATERIALS AVAILABILITY

The crystal structure of P. aeruginosa LpxC in complex with LPC-233 has been deposited to the Protein Data Bank (www.pdb.org) with the PDB access code of 8E4A. All data associated with this study are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials. Requests for materials should be sent to the corresponding author, and material transfer agreements are required.

References and Notes

- 1.World Health Organization, Global priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria to guide research, discovery, and development of new antibiotics, 2017, www.who.int/news/item/27-02-2017-who-publishes-list-of-bacteria-for-which-new-antibiotics-are-urgently-needed.

- 2.Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Bradley JS, Edwards JE, Gilbert D, Rice LB, Scheld M, Spellberg B, Bartlett J, Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis 48, 1–12 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States 2019, 2019; www.cdc.gov/DrugResistance/Biggest-Threats.html.

- 4.Raetz CRH, Whitfield C, Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu. Rev. Biochem 71, 635–700 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitfield C, Trent MS, Biosynthesis and export of bacterial lipopolysaccharides. Annu. Rev. Biochem 83, 99–128 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou P, Zhao J, Structure, inhibition, and regulation of essential lipid A enzymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1862, 1424–1438 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou P, Hong J, Structure- and ligand-dynamics-based design of novel antibiotics targeting lipid A enzymes LpxC and LpxH in Gram-negative bacteria. Acc. Chem. Res 54, 1623–1634 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erwin AL, Antibacterial drug discovery targeting the lipopolysaccharide biosynthetic enzyme LpxC. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med 6, a025304 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalinin DV, Holl R, LpxC inhibitors: A patent review (2010–2016). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat 27, 1227–1250 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niu Z, Lei P, Wang Y, Wang J, Yang J, Zhang J, Small molecule LpxC inhibitors against gram-negative bacteria: Advances and future perspectives. Eur. J. Med. Chem 253, 115326 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ushiyama F, Takashima H, Matsuda Y, Ogata Y, Sasamoto N, Kurimoto-Tsuruta R, Ueki K, Tanaka-Yamamoto N, Endo M, Mima M, Fujita K, Takata I, Tsuji S, Yamashita H, Okumura H, Otake K, Sugiyama H, Lead optimization of 2-hydroxymethyl imidazoles as non-hydroxamate LpxC inhibitors: Discovery of TP0586532. Bioorg. Med. Chem 30, 115964 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamada Y, Takashima H, Walmsley DL, Ushiyama F, Matsuda Y, Kanazawa H, Yamaguchi-Sasaki T, Tanaka-Yamamoto N, Yamagishi J, Kurimoto-Tsuruta R, Ogata Y, Ohtake N, Angove H, Baker L, Harris R, Macias A, Robertson A, Surgenor A, Watanabe H, Nakano K, Mima M, Iwamoto K, Okada A, Takata I, Hitaka K, Tanaka A, Fujita K, Sugiyama H, Hubbard RE, Fragment-based discovery of novel non-hydroxamate LpxC inhibitors with antibacterial activity. J. Med. Chem 63, 14805–14820 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen F, Aggen JB, Andrews LD, Assar Z, Boggs J, Choi T, Dozzo P, Easterday AN, Haglund CM, Hildebrandt DJ, Holt MC, Joly K, Jubb A, Kamal Z, Kane TR, Konradi AW, Krause KM, Linsell MS, Machajewski TD, Miroshnikova O, Moser HE, Nieto V, Phan T, Plato C, Serio AW, Seroogy J, Shakhmin A, Stein AJ, Sun AD, Sviridov S, Wang Z, Wlasichuk K, Yang W, Zhou X, Zhu H, Cirz RT, Optimization of LpxC inhibitors for antibacterial activity and cardiovascular safety. ChemMedChem 14, 1560–1572 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coggins BE, Li X, McClerren AL, Hindsgaul O, Raetz CRH, Zhou P, Structure of the LpxC deacetylase with a bound substrate-analog inhibitor. Nat. Struct. Biol 10, 645–651 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coggins BE, McClerren AL, Jiang L, Li X, Rudolph J, Hindsgaul O, Raetz CRH, Zhou P, Refined solution structure of the LpxC-TU-514 complex and pKa analysis of an active site histidine: Insights into the mechanism and inhibitor design. Biochemistry 44, 1114–1126 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barb AW, Jiang L, Raetz CR, Zhou P, Structure of the deacetylase LpxC bound to the antibiotic CHIR-090: Time-dependent inhibition and specificity in ligand binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 104, 18433–18438 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang X, Lee CJ, Chen X, Chung HS, Zeng D, Raetz CR, Li Y, Zhou P, Toone EJ, Syntheses, structures and antibiotic activities of LpxC inhibitors based on the diacetylene scaffold. Bioorg. Med. Chem 19, 852–860 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee CJ, Liang X, Chen X, Zeng D, Joo SH, Chung HS, Barb AW, Swanson SM, Nicholas RA, Li Y, Toone EJ, Raetz CR, Zhou P, Species-specific and inhibitor-dependent conformations of LpxC: Implications for antibiotic design. Chem. Biol 18, 38–47 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee CJ, Liang X, Wu Q, Najeeb J, Zhao J, Gopalaswamy R, Titecat M, Sebbane F, Lemaitre N, Toone EJ, Zhou P, Drug design from the cryptic inhibitor envelope. Nat. Commun 7, 10638 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lemaitre N, Liang X, Najeeb J, Lee CJ, Titecat M, Leteurtre E, Simonet M, Toone EJ, Zhou P, Sebbane F, Curative treatment of severe Gram-negative bacterial infections by a new class of antibiotics targeting LpxC. MBio 8, e00674–00617 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeng D, Zhao J, Chung HS, Guan Z, Raetz CR, Zhou P, Mutants resistant to LpxC inhibitors by rebalancing cellular homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem 288, 5475–5486 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clements JM, Coignard F, Johnson I, Chandler S, Palan S, Waller A, Wijkmans J, Hunter MG, Antibacterial activities and characterization of novel inhibitors of LpxC. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 46, 1793–1799 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luke DR, Tomaszewski K, Damle B, Schlamm HT, Review of the basic and clinical pharmacology of sulfobutylether-beta-cyclodextrin (SBECD). J. Pharm. Sci 99, 3291–3301 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindberg R, Fredlund H, Nicholas R, Unemo M, Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates with reduced susceptibility to cefixime and ceftriaxone: association with genetic polymorphisms in penA, mtrR, porB1b, and ponA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 51, 2117–2122 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohnishi M, Golparian D, Shimuta K, Saika T, Hoshina S, Iwasaku K, Nakayama S, Kitawaki J, Unemo M, Is Neisseria gonorrhoeae initiating a future era of untreatable gonorrhea?: detailed characterization of the first strain with high-level resistance to ceftriaxone. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 55, 3538–3545 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Unemo M, Golparian D, Nicholas R, Ohnishi M, Gallay A, Sednaoui P, High-level cefixime- and ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae in France: novel penA mosaic allele in a successful international clone causes treatment failure. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 56, 1273–1280 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazzariol A, Bazaj A, Cornaglia G, Multi-drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria causing urinary tract infections: a review. J. Chemother 29, 2–9 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forge Therapeutics, Inc., Forging novel, metalloenzyme-targeting anti-infectives to combat antimicrobial resistance, 2021, www.nature.com/articles/d43747-021-00155-2.

- 29.Liu X, Wright M, Hop CE, Rational use of plasma protein and tissue binding data in drug design. J. Med. Chem 57, 8238–8248 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang F, Xue J, Shao J, Jia L, Compilation of 222 drugs’ plasma protein binding data and guidance for study designs. Drug Discov. Today 17, 475–485 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang X, Gopalaswamy R, Navas F 3rd, Toone EJ, Zhou P, A scalable synthesis of the difluoromethyl-allo-threonyl hydroxamate-based LpxC inhibitor LPC-058. J. Org. Chem 81, 4393–4398 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weinstein MP, Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, ed. 31, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ropp PA, Hu M, Olesky M, Nicholas RA, Mutations in ponA, the gene encoding penicillin-binding protein 1, and a novel locus, penC, are required for high-level chromosomally mediated penicillin resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 46, 769–777 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Six DA, Carty SM, Guan Z, Raetz CR, Purification and mutagenesis of LpxL, the lauroyltransferase of Escherichia coli lipid A biosynthesis. Biochemistry 47, 8623–8637 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gabrielsson J, Weiner D, Non-compartmental analysis. Methods Mol. Biol 929, 377–389 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, Harbarth S, Hindler JF, Kahlmeter G, Olsson-Liljequist B, Paterson DL, Rice LB, Stelling J, Struelens MJ, Vatopoulos A, Weber JT, Monnet DL, Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect 18, 268–281 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jackman JE, Raetz CRH, Fierke CA, Site-directed mutagenesis of the bacterial metalloamidase UDP-(3-O- acyl)-N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase (LpxC). Identification of the zinc binding site. Biochemistry 40, 514–523 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kabsch W, XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 66, 125–132 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ, Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr 40, 658–674 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moriarty NW, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, electronic Ligand Builder and Optimization Workbench (eLBOW): a tool for ligand coordinate and restraint generation. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 65, 1074–1080 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emsley P, Cowtan K, Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 60, 2126–2132 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH, PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 66, 213–221 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The crystal structure of P. aeruginosa LpxC in complex with LPC-233 has been deposited to the Protein Data Bank (www.pdb.org) with the PDB access code of 8E4A. All data associated with this study are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials. Requests for materials should be sent to the corresponding author, and material transfer agreements are required.