Abstract

Transmission-blocking vaccines based on sexual-stage surface antigens of Plasmodium falciparum may assist in the control of this lethal form of human malaria. Two vaccine candidates, Pfs25 and Pfs28, were produced as single recombinant fusion proteins. The 39-kDa chimeric proteins, having a C-terminal His6 tag, were secreted by Saccharomyces cerevisiae, using the prepro-α-factor leader sequence. Pfs25-28 fusion proteins were significantly more potent than either Pfs25 or Pfs28 alone in eliciting antibodies in mice that blocked oocyst development in Anopheles freeborni mosquitoes: complete inhibition of oocyst development in the mosquito midgut was achieved with fewer vaccinations, at a lower dose, and for a longer duration than with either Pfs25 or Pfs28 alone. Increased antigen-specific immunoglobulin G titers and highly significant lymphoproliferative stimulation by Pfs28-containing antigens suggest the presence of an immunodominant helper T-cell epitope in the Pfs28 portion of the fusion proteins. This epitope may be responsible for the enhanced humoral response to both Pfs25 and Pfs28 antigens. Protein production of the fusion protein was improved 12-fold by converting Pfs28 codons to yeast-preferred codons (TBV28), using a modified ADH2 promoter and incorporating a (Glu-Ala)2 repeat after the Kex2 cleavage site.

The old tools of control, namely, vector control and chemotherapy, have been insufficient to reverse the increase in disease and death from malaria. They have proven to be neither cost-effective to deploy nor easy to sustain. Malaria vaccines hold the hope of an affordable, sustainable intervention that can be added to our armamentarium to fight this ancient scourge. Transmission-blocking vaccines that prevent the spread of vaccine-escape mutants and diminish the infectivity of the parasite to the mosquito are a potentially powerful component of malaria vaccines.

Transmission of Plasmodium falciparum occurs only if parasites in infected blood ingested by a female Anopheles mosquito undergo sexual and sporogonic development within the mosquito midgut. By using an ex vivo membrane-feeding assay and monoclonal antibodies, several sexual-stage surface antigens have been shown to be targets of transmission-blocking immunity (3, 7, 8, 15, 18). By preventing the development of the parasite within the mosquito midgut, antibodies to these target antigens block transmission of P. falciparum to the mosquito vector. Pfs25, a 25-kDa surface antigen of zygotes and ookinetes (10), and Pfs28, a 28-kDa surface antigen of late ookinetes (4), are two of the lead vaccine candidates. Both comprise four tandem epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like domains presumably anchored to the parasite surface by glycosylphosphatidylinositol, and both, produced as recombinant proteins in yeast, have been shown to induce transmission-blocking antibodies in experimental laboratory animals (1, 11, 12).

The mechanisms by which polyclonal sera and monoclonal antibodies to Pfs25 block transmission appear to reside in inhibiting the transformation of zygotes to ookinetes and the ability of ookinetes to infect mosquitoes, respectively (12). Polyclonal sera to Pgs28, the avian malaria parasite (P. gallinaceum) analog of Pfs28, appear to block transmission by inhibiting the transformation of zygotes to ookinetes in vitro and by suppressing the development of ookinetes to oocysts in vivo (5). Because antibodies to these two antigens appear to block infectivity by attacking different proteins on the same developmental stages, the question arose as to whether Pfs25 and Pfs28 will act synergistically to block parasite infectivity to mosquitoes. Indeed, mixing Pfs25 and Pfs28 mouse antibodies demonstrated a more potent transmission-blocking effect (4); however, combining yeast-produced Pfs25 and Pfs28 in a single vaccine did not produce a synergistic transmission-blocking effect in mice (8a). We report here that a fusion of Pfs25 and Pfs28 as a single chimeric recombinant protein is a more potent transmission-blocking vaccine than either antigen alone but perhaps not by antibodies to Pfs25 and Pfs28 acting synergistically.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Constructs. (i) Plasmid pIX154 and TBV25 PCR product.

Various constructs were cloned into the KpnI and SpeI sites of plasmid pIXY154, a derivative of pIXY120 (14). DNA sequence encoding TBV25 (Pfs25 in yeast-preferred codons) (9) from Ala22 to Thr193 was amplified by PCR using oligonucleotides 5′TBV25 (5′GGGGTACCTTTGGATAAAAGAGCTAAGGTCACTGTCGAC3′ [introduced α-factor leader sequence and restriction site are in italics and boldface, respectively]) and 3′TBV25 (5′-CCCCCGGGACCACCACCGGTACAAATGGAAGATTCTTG-3′ [introduced flexible linker and restriction site are in italics and boldface, respectively]) and digested with KpnI and SmaI.

(ii) 25-28D construct.

DNA sequence encoding Pfs28 (4) from Val24 to Cys175 was amplified by PCR using oligonucleotides 5′Pfs28 (5′GGTCCCGGGGGTGGTGTTACTGAAAATACAATATGT3′ [introduced flexible linker and SmaI site are in italics and boldface, respectively]) and 3′Pfs28D (5′-AAACTAGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGGGCCCACATGTATAATAATTTCCTTC-3′ [introduced linker and His6 are italicized, and the new SpeI site is in boldface]) and digested with SmaI and SpeI. A three-way ligation was performed with the digested TBV25, Pfs28D PCR products, and pIXY154.

(iii) 25-28B construct.

DNA sequence encoding Pfs28 from Val24 to Pro179 was amplified by PCR using oligonucleotides 5′Pfs28 and 3′Pfs28B (5′AAACTAGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGAGGATCCTCTTTACATGTATAATA3′ [introduced linker and His6 are italicized, and the new SpeI site is in boldface]) and digested with SmaI and SpeI. A three-way ligation was performed with the digested TBV25, Pfs28B PCR products, and pIXY154.

(iv) 25-28C construct.

DNA sequence encoding Pfs28 from Val24 to Ser196 was amplified by PCR using oligonucleotides 5′Pfs28 and 3′Pfs28C (5′AACTAGTG GTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGGGCCCACTATATGATGTATCAGCCT G-3′ [introduced linker and His6 are italicized, and the new restriction site is in boldface]) and digested with SmaI and SpeI. A three-way ligation was performed with the digested TBV25, Pfs28C PCR products, and pIXY154.

(v) Pfs28C construct.

DNA sequence encoding Pfs28 from Val24 to Ser196 was amplified by the PCR using oligonucleotides 5′Pfs28-2 (5′GGGGTACCTTTGGATAAAAGAGTTACTGAAAATACAATATGT3′ [introduced α-factor leader sequence and KpnI site are in italics and boldface, respectively]) and 3′Pfs28C. Because Pfs28 has an internal KpnI site, the PCR product was first digested with HindIII, then the 167-bp fragment was digested with KpnI, and the 397-bp fragment was digested with SpeI. A three-way ligation was performed with the digested PCR products and pIXY154.

(vi) TBV25-28 construct.

Overlapping 87-mer oligonucleotides were used to construct Pfs28C in yeast-preferred codons (2). Oligonucleotides were phosphorylated, annealed, and ligated together, and the resulting products were used as PCR templates. PCR products were filled in, phosphorylated, cloned into SmaI-digested, bacterial alkaline phosphatase-treated pUC18 (Pharmacia), and subsequently sequenced. Sequential ligations were performed to synthesize a full-length construct with the correct sequence. TBV28 was subsequently amplified by PCR from the full-length recombinant plasmid by using oligonucleotides 5′TBV28 (5′GGTCCCGGGGGTGGTGTTACTGAAAACACTATTTGT3′ [introduced SmaI site is in boldface]) and 3′TBV28 (5′AAACTAGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGGGCCCAGAGTAAGAAGTATCAGCTTG 3 [introduced linker sequence, Gly-Pro, and His6 are italicized, and the new restriction site is in boldface]), digested with SmaI-SpeI, and ligated into SmaI-SpeI-cut dephosphorylated pIXY925 recombinant plasmid which contains the TBV25-Pfs28C construct.

(vii) Host cells.

The resulting recombinant plasmids were used to transform Saccharomyces cerevisiae 2905/6 (diploid, trp1Δ lys2-801 ura3-52 ade2-101), VQ1 (haploid, trp1Δ lys2-801 ura3-52), and VK1 (haploid, trp1Δ lys2-801 pep4−:ura).

Fermentation.

Protein production is essentially as described previously (9). A 1-ml frozen seed lot was thawed and used to inoculate 500 ml of expansion medium (8% glucose, 1% yeast nitrogen base, 2% acid-hydrolyzed Casamino Acids, and if necessary 400 mg of adenine sulfate and 400 mg of uracil per liter) in a Tunair baffled shaker flask. The cells were grown overnight at 30°C with shaking at 250 rpm. The overnight growth in expansion medium was used to inoculate 3 to 3.5 liters of fermentation medium (1% yeast extract, 1% yeast nitrogen base, 2% acid-hydrolyzed Casamino Acids, and if necessary 400 mg of adenine sulfate and 400 mg of uracil per liter). The Bioflo-III fermentor was set to maintain temperature at 25°C and dissolved oxygen at or above 60% by agitation between 360 and 1,000 rpm. A glucose-rich nutrient medium (25% glucose, 1% yeast extract, 1% yeast nitrogen base, 2% acid-hydrolyzed Casamino Acids, 2.5 g of MgSO4 per liter, and if necessary 0.5 g of adenine sulfate and 0.5 g of uracil per liter) was fed continuously at a rate of 5 ml/liter/h for approximately 28 h. The pH was maintained at 5.02 by a base feed of 25% NH4OH and an acid feed of glucose-rich nutrient medium. When the culture reached ≥50 OD600 (optical density at 600 nm) units, the carbon source was switched from glucose to 30% ethanol–20% glycerol at 8.3 ml/liter/h for 10 to 16 h to induce protein secretion.

Protein purification.

The culture supernatant was recovered by tangential microfiltration (0.1-mm-pore-size filter) or by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C and then filter sterilized through a 0.45-μm-pore-size cellulose acetate membrane (Nalgene). The sterile medium was concentrated to ∼350 ml by tangential ultrafiltration with a YD 10 spiral hollow fiber (Amicon) and then continuously dialyzed by tangential diafiltration with 1.5 liters of 2× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4). The retentate was incubated with nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) agarose with shaking at 4°C. After overnight incubation, the suspension was transferred to a column, and the resin was washed sequentially with at least 3 column volumes of 2× PBS (pH 7.4), 2× PBS (pH 6.8), and 1× PBS (pH 6.4). The protein was eluted from the resin by using 0.250 M sodium acetate (pH 4.5) and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Further purification was performed by size exclusion chromatography using a 16/60 Pharmacia Superdex-75 column to which 1× PBS (pH 7.4) was applied at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. One-milliliter fractions were collected and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Fractions containing the protein of interest were pooled, and the protein concentration was determined by a bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce), using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard.

Endotoxin determination.

The endotoxin content of each sample was determined by gel-clot Limulus amoebocyte lysate (Charles River Endosafe) in single-test glass vials (sensitivity of 0.25 endotoxin unit/ml). Serial twofold dilutions of the protein samples were tested until a negative result (endpoint) was reached, and the endotoxin content was calculated as instructed by the manufacturer.

Glycosylation analysis.

Glycosylation was determined by periodate oxidation (digoxigenin glycan detection kit; Boehringer Mannheim Biochemica), a modification of a previous method (13).

Animals and vaccinations.

All animal studies were done in compliance with National Institutes of Health guidelines and under the auspices of an Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocol. Alum (aluminum hydroxide; Superfos Biosector a/s lot no. 2170 and 2179) was used as the delivery system for all vaccinations (800 μg per 0.5-ml dose). Purified fusion proteins diluted in 1× PBS (pH 7.4) were adsorbed to alum by continuous rocking for 30 min at room temperature. In the first study, 39 CAF1 mice were arranged into 13 equal groups, members of which received three doses of either TBV25 (1,250, 250, and 50 pmol), 25-28B (1,250, 250, and 50 pmol), 25-28C (625, 125, and 25 pmol), and 25-28D (1,250, 250, and 50 pmol) or no added protein by the intraperitoneal route on days 0, 21, and 42. Blood samples were collected and processed for serum every week until day 56; thereafter, samples were obtained 42 (day 84) and 126 (day 168) days after the third vaccination. In the second study, 95 CAF1 mice were arranged into 19 groups of five mice each. The mice received three doses each (625, 125, and 25 pmol) of either TBV25, Pfs28C, TBV25H plus Pfs28C, TBV25-28, 25-28B, and 25-28D or no added protein by the intraperitoneal route on days 0, 21, and 42. Blood samples were collected as described above.

Transmission-blocking assay.

Transmission-blocking activity was assayed as described previously (15). Briefly, test sera were mixed with mature in vitro-cultured P. falciparum gametocytes and fed to mosquitoes through an artificial membrane stretched across the base of a water-jacketed glass cylinder. The parasites in the blood meal were allowed to develop in the mosquito to the easily identifiable oocyst stage by maintaining the mosquitoes in a secured insectary for 6 to 8 days. Infectivity was measured by dissecting midguts, staining with mercurochrome, and then counting the number of oocysts per mosquito midgut of at least 20 mosquitoes. The data were analyzed as previously described (11).

T-cell proliferation.

Three CAF1 mice received 25 μg of TBV25-28 in Freund’s complete adjuvant by subcutaneous injection in the footpad. After 10 days, mice were sacrificed, the draining periaortic and inguinal lymph nodes were harvested and pooled, and single-cell suspensions were prepared. Aliquots (200 μl) of the suspension containing 2 × 106 cells were added to individual wells in 96-well flat-bottom plates containing 1 or 10 μg of TBV25H, Pfs28C, 25-28B, TBV25-28, and 25-28D per ml in quadruplicate. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 4 days, and then [3H]thymidine (1 μCi) was added. After 18 h, cells were harvested on an automated harvesting device (Skatron-Micro 96 Harvester; Skatron Instruments, Sterling, Va.), and 3H incorporation was determined by scintillation counting (1205 β Plate; LKB Wallac, Gaithersburg, Md.).

ELISA.

Serum antibodies to Pfs25 and Pfs28 were assayed essentially as described previously (9). Briefly, Immulon 4 96-well microtiter plates (Dynatech) were coated with 0.1 μg of TBV25H or Pfs28C in coating buffer (15 mM Na2CO3, 35 mM NaHCO3 [pH 9.6]) at 4°C overnight. The plates were blocked with 1% BSA in TPBS (0.05% Tween in PBS) for at least 1 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. Mouse sera were serially diluted in 1% BSA–TPBS. One hundred microliters of diluted serum was added to antigen-coated wells in triplicate and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The plates were washed extensively with TPBS. One hundred microliters of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (heavy H and light chains; Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc.) diluted 1:1,000 in TPBS was added to each well and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. After extensive washes with TPBS, 100 μl of p-nitrophenyl disodium phosphate solution (Sigma 104 phosphatase substrate, 1 tablet per 5 ml of coating buffer) was added to each well and incubated for 20 min at room temperature, and the absorbance at 410 nm was read with a Dynatech MR5000 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plate reader. Serum dilutions at an absorbance value of 0.5 were designated as the endpoint of ELISA titers.

Inhibition/competition ELISAs (6) were performed with mouse sera dilutions on the linear portion of the titration curves. The diluted sera were mixed (1:1) with various concentrations of inhibitors (0 to 500 pmol) in 1% BSA-coating buffer and incubated at room temperature with shaking for 2 h. One hundred microliters of the mixture was added to triplicate antigen-coated wells and incubated for at least 1 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. The rest of the assay was performed as described above. The degree of inhibition for each concentration of inhibitor was calculated as OD410 of inhibitor-free sample minus OD410 of test sample divided by OD410 of inhibitor-free sample times 100.

RESULTS

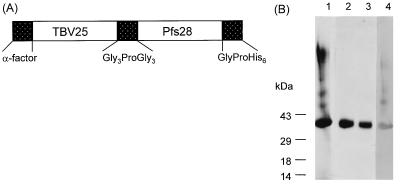

Three truncated forms of Pfs28, varying in length after the fourth EGF-like domain, were fused to the carboxy terminus of TBV25 (Ala22 to Thr193) by a flexible linker, having an amino acid sequence of GGGPGGG (Fig. 1A). A prepro-α-factor leader sequence was encoded at the amino terminus, conferring secretion by S. cerevisiae, and a hexahistidine tag was encoded at the carboxy terminus, allowing purification on Ni-NTA agarose. With all constructs, an approximately 39-kDa chimeric protein was purified by Ni-NTA agarose and analyzed by Western blotting using 4B7, a monoclonal antibody to Pfs25, which recognizes a B-cell epitope in the third EGF-like domain of Pfs25 present in both nonreduced and reduced forms of the protein (1, 17) (Fig. 1B). The purified proteins contained ≤8 endotoxin units per ml (data not shown but provided for review). Glycosylation analysis by periodate oxidation showed that the purified proteins had no detectable N-linked or O-linked glycosylation (data not shown but provided for review).

FIG. 1.

(A) Schematic representation of the fusion constructs 25-28D, 25-28B, and 25-28C. Shown are the prepro-α-factor leader sequence at the N terminus, TBV25 (Ala22 to Thr193); flexible linker, GGGPGGG; Pfs28 (D, Val24 to Cys175, B, Val24 to Pro179; and C, Val24 to Ser196); and the hexahistidine tag at the C terminus. (B) Purification and characterization of S. cerevisiae-produced fusion protein 25-28C by SDS-PAGE. A 39-kDa recombinant protein was purified from yeast culture supernatant by affinity chromatography using Ni-NTA agarose (lane 1) and by size exclusion chromatography using Superdex-75 (lanes 2 and 3). The Ni-NTA agarose-purified recombinant protein was recognized by monoclonal antibody 4B7 to Pfs25, by Western blotting (lane 4).

The recombinant TBV25-Pfs28 fusion proteins were initially expressed in S. cerevisiae at approximately 0.5 mg/liter. To improve the yield, the following modifications were made: (i) the Pfs28 portion of the fusion was modified to yeast-preferred codons (2) by using synthetic oligonucleotides, (ii) the fusion gene was subcloned to a modified yeast shuttle vector which had an ADH2 promoter with a poly(A) tract (16), (iii) a (Glu-Ala)2 repeat was incorporated after the Kex2 cleavage site for more efficient cleavage of the protein product by Kex2 protease (19), and (iv) the pep4-deficient strain S. cerevisiae VK1 was chosen as the host cell. With these changes, the yield increased 12-fold, to 6.2 mg/liter. The new cell line was designated TBV25-28.

The purified proteins adsorbed to alum were used to vaccinate CAF1 mice. Transmission-blocking activities (measured by a standard membrane-feeding infectivity assay) of immune sera were examined 3 weeks after the second vaccination, 6 weeks after the third vaccination, and 4 months after the third vaccination. All three fusion proteins were more potent than TBV25H alone (Table 1). Mice that received the longest construct, 25-28C, developed the most potent transmission-blocking activity: oocyst development was completely blocked earlier (3 weeks after the second vaccination at the 625-pmol dose), at a lower dose (25-pmol 6 weeks after the third vaccination), and for a longer duration (126 days after the third vaccination) than with the other constructs. Mice that received the other two fusion proteins (25-28B and 25-28D) also showed complete transmission-blocking activity 6 weeks after the third vaccination at the 250- and 1,250-pmol doses.

TABLE 1.

Transmission-blocking activity of sera from immunized mice from study I

| Expt | Serum samplea | Immu- nogen | Dose (pmol) | Mean no. of oocysts (range) | Infectivity (% of con- trol)b | No. of mosqui- toes infected/ no. dissected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IID21 | Alum | 5.3 (0–19) | 100 | 22/23 | |

| TBV25H | 1,250 | 2.2 (0–11) | 42 | 18/21 | ||

| 250 | 7.3 (0–18) | 138 | 22/23 | |||

| 25-28B | 1,250 | 0.52 (0–5) | 10 | 11/24 | ||

| 250 | 0.49 (0–4) | 9 | 9/23 | |||

| 25-28C | 625 | 0 | 0 | 0/22 | ||

| 250 | 0.3 (0–2) | 5 | 7/23 | |||

| 25-28D | 1,250 | 2.8 (0–9) | 53 | 19/20 | ||

| 250 | 4.7 (1–13) | 89 | 23/23 | |||

| 2 | IIID42 | Alum | 0.60 (0–5) | 100 | 21/40 | |

| TBV25H | 1,250 | 0 | 0 | 0/26 | ||

| 250 | 0.27 (0–3) | 45 | 5/22 | |||

| 50 | 1.48 (0–8) | 247 | 17/25 | |||

| 25-28B | 1,250 | 0 | 0 | 0/23 | ||

| 250 | 0 | 0 | 0/23 | |||

| 50 | 0.96 (0–5) | 160 | 14/22 | |||

| 25-28C | 625 | 0 | 0 | 0/24 | ||

| 125 | 0 | 0 | 0/40 | |||

| 25 | 0 | 0 | 0/40 | |||

| 25-28D | 1,250 | 0.03 (0–1) | 5 | 1/23 | ||

| 250 | 0 | 0 | 0/25 | |||

| 50 | 2.85 (0–16) | 476 | 21/24 | |||

| 3 | IIID126 | Alum | 1.53 (0–4) | 100 | 21/27 | |

| TBV25H | 1,250 | 0.27 (0–3) | 18 | 6/23 | ||

| 250 | 1.42 (0–7) | 93 | 15/21 | |||

| 50 | 0.49 (0–3) | 32 | 10/22 | |||

| 25-28B | 1,250 | 0.08 (0–1) | 6 | 3/26 | ||

| 250 | 0.56 (0–4) | 37 | 12/24 | |||

| 50 | 1.22 (0–5) | 80 | 16/22 | |||

| 25-28C | 625 | 0 | 0 | 0/35 | ||

| 125 | 0 | 0 | 0/35 | |||

| 25 | 0.07 (0–1) | 0 | 4/39 | |||

| 25-28D | 1,250 | 0.20 (0–1) | 13 | 6/23 | ||

| 250 | 0.26 (0–2) | 17 | 6/20 | |||

| 50 | 1.37 (0–10) | 90 | 18/24 |

Identified by vaccination number (roman numeral) and the number of days (D) postvaccination (arabic numerals); e.g., IID21 denotes 21 days after the second vaccination.

Calculated as the geometric mean oocyst count of the test group divided by the mean oocyst count of the alum group times 100.

To further characterize the nature of the enhanced potency of the longest fusion protein and to determine the reproducibility of the results, a second study was performed to include additional groups of mice receiving Pfs28C alone, TBV25H and Pfs28C mixed together, and TBV25-28 (Pfs28 in yeast-preferred codons) instead of 25-28C. A transmission-blocking assay using sera collected 7 days after the second vaccination revealed that mice that received TBV25-28 were the only ones that elicited antibodies that completely blocked transmission (Table 2). Mixing TBV25H and Pfs28C together as a vaccine cocktail did not block transmission as well as TBV25-28, which has the two antigens linked together in a contiguous fusion protein.

TABLE 2.

Transmission-blocking activity of sera from immunized mice from study II (serum sample taken 7 days after the second vaccination)

| Immunogen | Dose (pmol) | Mean no. of oocysts (range) | Infectivity (% of con- trol)a | No. of mosqui- toes infected/ no. dissected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alum | 2.70 (0–16) | 100 | 30/34 | |

| TBV25H | 625 | 3.69 (0–10) | 137 | 23/25 |

| Pfs28C | 625 | 0.84 (0–5) | 31 | 14/24 |

| 125 | 1.50 (0–6) | 56 | 17/23 | |

| TBV25 + Pfs28C | 625 | 0.43 (0–2) | 16 | 9/22 |

| TBV25 + Pfs28C | 125 | 0.86 (0–9) | 32 | 14/24 |

| TBV25-28 | 625 | 0.28 (0–2) | 10 | 8/26 |

| 125 | 0 | 0 | 0/26 | |

| 25 | 3.57 (0–12) | 132 | 21/24 | |

| 25-28B | 625 | 0.44 (0–2) | 16 | 11/22 |

| 125 | 4.92 (1–21) | 182 | 26/26 | |

| 25-28D | 625 | 3.39 (0–12) | 125 | 21/25 |

Calculated as the geometric mean oocyst count of the test group divided by the mean oocyst count of the alum group times 100.

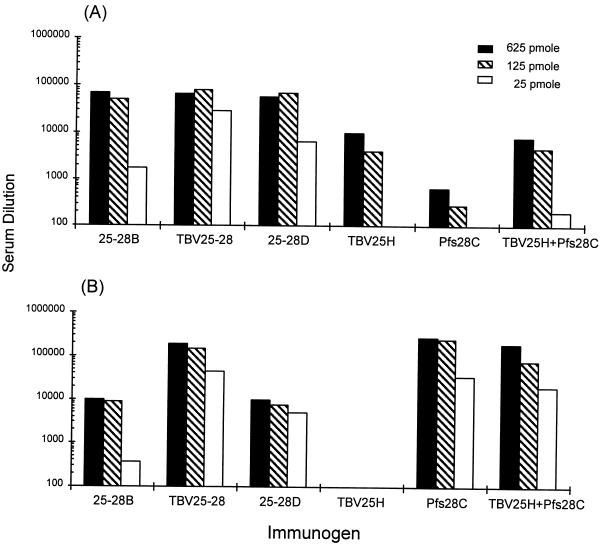

Humoral immune responses to both Pfs25 and Pfs28 were measured by ELISA. All respective groups developed antibody (IgG) responses to both antigens. Transmission-blocking activity, however, did not correlate with ELISA titers to either Pfs25 or Pfs28. ELISA titers 3 weeks after the second vaccination showed marked differences in humoral responses to the different immunogens (Fig. 2). Antisera to the longest Pfs28 construct, alone and as a fusion protein, had anti-Pfs28 ELISA titers of 1:105. This titer is an order of magnitude higher than antisera to the two shorter fusion proteins, indicating the presence of an immunodominant epitope in the longest construct. Antisera to the three fusion proteins, 25-28B, TBV25-28, and 25-28D, had anti-Pfs25 ELISA titers of 1:105, also an order of magnitude greater than the titer of antiserum to Pfs25 alone, suggesting the presence of an immunodominant helper T-cell epitope within the fusion proteins driving the primary antibody response to Pfs25. Antibody responses (titers of ≥1:104) to both Pfs25 and Pfs28 persisted until 4 months after the third vaccination.

FIG. 2.

Total IgG titers to TBV25H (A) and to Pfs28C (B) in groups of CAF1 mice immunized with either 25-28B, TBV25-28, 25-28D, TBV25H, Pfs28C, or TBV25H plus Pfs28C. Mice were vaccinated via the intraperitoneal route with either 625, 125, or 25 pmol of each antigen. Antibody titers 3 weeks after the second vaccination as measured by ELISA are presented.

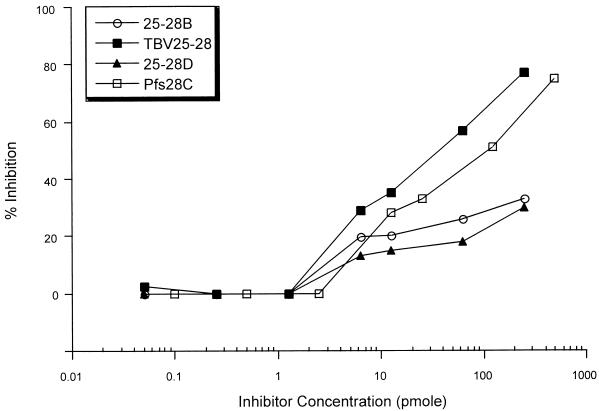

Competition ELISAs were performed to characterize structural differences between the fusion proteins and to address the specificity of the antibodies to the different immunogens. Polyclonal sera from mice vaccinated with TBV25-28 were evaluated in a competitive inhibition ELISA in which binding to either TBV25H or Pfs28C was carried out in the presence of increasing concentrations of TBV25H or Pfs28C, respectively, and various 25-28 antigens. With TBV25H as the capture antigen, all inhibition curves were found to be identical (data not shown but provided for review). With Pfs28C as the capture antigen, however, the two shorter fusion constructs (25-28B and 25-28D) had qualitatively different inhibition curves than the longer Pfs28 constructs (TBV25-28 and Pfs28C), suggesting that the former lacked one or more B-cell epitopes present in the longer constructs (Fig. 3). In addition, the differences in the inhibition curves between TBV25-28 and Pfs28C may reflect structural differences in the Pfs28 portion of the two constructs.

FIG. 3.

ELISA inhibition of mouse anti TBV25-28 antibodies by Pfs28C, 25-28B, TBV25-28, and 25-28D. Polyclonal sera from mice immunized twice with 125 pmol of TBV25-28 were diluted and mixed with various concentrations of the indicated inhibitor proteins. The mixture was incubated for 2 h prior to addition to Pfs28C-coated plates, and the degree of inhibition for each concentration of inhibitor was calculated.

Antigen-specific proliferative responses of T lymphocytes from the periaortic and inguinal lymph nodes are presented in Table 3. At the 1-μg/ml stimulation dose, no significant TBV25H-specific stimulation was observed whereas highly significant stimulation was induced by antigens containing Pfs28, thus confirming the presence of an immunodominant T-cell epitope within Pfs28. At the 10-μg/ml dose, TBV25H-specific stimulation was observed but the mean counts were lower than any of the Pfs28-containing antigens.

TABLE 3.

Lymphoproliferative responses to antigens after 5 days of culturea

| Concn (μg/ml) and antigen | Mean cpm ± SDb | Pc |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||

| Control | 1,063 ± 488 | |

| TBV25H | 1,041 ± 373 | 0.945 |

| Pfs28C | 6,341 ± 1,116 | 0.0001 |

| 25-28B | 8,348 ± 2,575 | 0.001 |

| TBV25-28 | 11,923 ± 6,798 | 0.019 |

| 25-28D | 8,444 ± 1,943 | 0.0001 |

| 10 | ||

| Control | 1,036 ± 38 | |

| TBV25H | 3,500 ± 1,619 | 0.023 |

| Pfs28C | 18,823 ± 8,575 | 0.006 |

| 25-28B | 13,453 ± 8,366 | 0.025 |

| TBV25-28 | 24,517 ± 13,343 | 0.013 |

| 25-28D | 21,990 ± 4,463 | 0.0001 |

T-cell proliferation by pooled periaortic and inguinal lymph node cells from three CAF1 mice immunized with 25 μg of TBV25-28 and stimulated in vitro with 1 or 10 μg of TBV25H, Pfs28C, 25-28B, TBV25-28, or 25-28D per ml.

Of quadruplicate samples.

From pairwise t tests.

DISCUSSION

Yeast recombinant Pfs25 and Pfs28 alone elicited antibodies which conferred complete transmission-blocking immunity in experimental laboratory animals after three vaccinations (1, 4, 11, 12). Mixing antibodies against Pfs25 and Pfs28 enhanced blocking activity relative to sera against Pfs25 or Pfs28 alone (4), providing a basis for linking the two antigens together as a single transmission-blocking vaccine. However, mixing the antigens in a single injection did not enhance the immunogenicity of the vaccine (reference 8a and Table 2). In this study, we examined linking Pfs25 and Pfs28 together to produce contiguous fusion proteins as a cost-effective means of enhancing potency.

The fusion proteins were designed to have Pfs25, which can be expressed at high levels (30 mg/liter), at the amino terminus and Pfs28, which is secreted at relatively low levels (0.3 mg/liter), at the carboxy terminus. A flexible linker with an amino acid sequence of GGGPGGG was incorporated in the middle of the two antigens with the notion that the linker would allow the two polypeptides to fold independently and assume native conformations. Glycine was chosen to allow free rotation of the amide bonds, and proline was incorporated to break α-helices and to act as a “stalk” between the two polypeptides. The fusion proteins were assumed to be folded correctly based on their ability to elicit transmission-blocking activity because as previous studies have shown, recombinant Pfs25 requires both an adjuvant and at least partial native conformation to induce Pfs25-specific transmission-blocking antibodies (12).

The fusion proteins adsorbed to alum were more potent in inducing transmission-blocking antibodies than either Pfs25 or Pfs28 recombinant protein alone or Pfs25 and Pfs28 mixed together in a vaccine cocktail. In one study, the longest fusion protein, 25-28C, showed complete transmission-blocking activity after only two vaccinations, at a dose of 25 pmol after three vaccinations, and for a 4-month duration. The nature of this enhanced potency is presently not clear; however, analysis of the inhibition curves by competition ELISA indicates the presence of an additional Pfs28 B-cell epitope in the longest construct that is not present in the two shorter constructs. This epitope alone cannot account for the enhanced potency because unlike the longest construct, Pfs28 alone did not block transmission after two vaccinations. Structural differences in the Pfs28 part of the fusion protein, suggested by differences in the inhibition curves between Pfs28C and TBV25-28 (Fig. 3), may account for some of the enhanced potency. We also searched for the presence of helper T-cell epitope(s) responsible for the enhanced immunogenicity of the fusion protein. The presence of such an epitope in Pfs28 is suggested from studies of lymphoproliferative responses to Pfs25 and Pfs28 antigens. The increased IgG titers to Pfs25 3 weeks after the second vaccination and the highly significant lymphoproliferative stimulation by Pfs28-containing antigens point to the presence of an immunodominant helper T-cell epitope in the Pfs28 portion of the fusion proteins. This Pfs28-derived epitope may be driving, in part, the enhanced humoral response to the covalently linked Pfs25-derived B-cell epitope(s) in the fusion protein. This notion is consistent with our findings that mixing the separate antigens together does not enhance the immunogenicity.

Identifying and re-creating the B-cell epitopes that are targets of transmission-blocking antibodies may be important in transmission-blocking vaccine development. Incorporating a helper T-cell epitope that will boost the antibody response to these B-cell epitopes may increase the potency of the transmission-blocking vaccine. The recombinant fusion protein, Pfs25-Pfs28, includes all four EGF-like domains from both antigens, thereby incorporating all possible B-cell epitopes that may or may not be targets of transmission-blocking antibodies. The longest fusion protein appears to contain a helper T-cell epitope that boosted the antibody response. Still to be identified are the B-cell epitopes in Pfs25 and Pfs28 that are required to elicit blocking antibodies and the helper T-cell epitope in Pfs28 that boosts the production of these antibodies.

Yeast recombinant Pfs25-Pfs28 fusion protein is a potent transmission-blocking vaccine formulation that has incorporated two lead transmission-blocking vaccine candidates against P. falciparum. Complete inhibition of oocyst development in the mosquito midgut was achieved with fewer vaccinations, at a lower dose, and for a longer duration than with either Pfs25 or Pfs28 alone. If the lower production levels can be overcome and potent clinical-grade material manufactured, then the fusion protein should be considered the new lead transmission-blocking vaccine candidate.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge David B. Keister and Olga Muratova for expert technical assistance in performing membrane feeding assays, Jing-Hui Tian and Dragana Jankovic for assistance with the T-cell proliferation assays, and Janet Murray for help with the fermentations.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barr P J, Green K M, Gibson H L, Bathurst I C, Quakyi I A, Kaslow D C. Recombinant Pfs25 protein of Plasmodium falciparum elicits malaria transmission-blocking immunity in experimental animals. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1203–1208. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.5.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennetzen J L, Hall B D. Codon selection in yeast. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:3026–3031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter R, Graves P M, Keister D B, Quakyi I A. Properties of epitopes of Pfs48/45, a target of transmission blocking monoclonal antibodies, on gametes of different isolates of Plasmodium falciparum. Parasite Immunol. 1990;12:587–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1990.tb00990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duffy P E, Kaslow D C. A novel malaria protein, Pfs28, and Pfs25 are genetically linked and synergistic as falciparum malaria transmission-blocking vaccines. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1109–1113. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.3.1109-1113.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duffy P E, Pimenta P, Kaslow D C. Pgs28 belongs to a family of epidermal growth factor-like antigens that are targets of malaria transmission-blocking antibodies. J Exp Med. 1993;177:505–510. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.2.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hui G S N, Hashimoto A, Chang S P. Roles of conserved and allelic regions of the major merozoite surface protein (gp195) in immunity against Plasmodium falciparum. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1422–1433. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1422-1433.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaslow D C. Transmission-blocking immunity against malaria and other vector-borne diseases. Curr Opin Immunol. 1993;5:557–565. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(93)90037-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaslow D C. Transmission-blocking vaccines: uses and current status of development. Int J Parasitol. 1997;27:183–189. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(96)00148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8a.Kaslow, D.C. Unpublished observations.

- 9.Kaslow D C, Shiloach J. Production, purification and immunogenicity of a malaria transmission-blocking vaccine candidate: TBV25H expressed in yeast and purified using nickel-NTA agarose. Bio/Technology. 1994;12:494–499. doi: 10.1038/nbt0594-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaslow D C, Quakyi I A, Syin C, Raum M G, Keister D B, Coligan J E, McCutchan T F, Miller L H. A vaccine candidate from the sexual stage of human malaria that contains EGF-like domains. Nature. 1988;333:74–76. doi: 10.1038/333074a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaslow D C, Bathurst I C, Keister D B, Campbell G H, Adams S, Morris C L, Sullivan J S, Barr P J, Collins W E. Safety, immunogenicity, and in vitro efficacy of a muramyl tripeptide-based malaria transmission-blocking vaccine in an Aotus nancymai monkey model. Vaccine Res. 1993;2:95–103. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaslow D C, Bathurst I C, Lensen T, Ponnudurai T, Barr P J, Keister D B. Saccharomyces cerevisiae recombinant Pfs25 adsorbed to alum elicits antibodies that block transmission of Plasmodium falciparum. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5576–5580. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5576-5580.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Shannessy D J, Voorstad P J, Quarles R H. Quantitation of glycoproteins on electroblots using the biotin-streptavidin complex. Anal Biochem. 1987;163:204–209. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Price V, Mochizuki D, March C J, Cosman D, Deeley M D, Klinke R, Clevenger W, Gillis S, Baker P, Urdal D. Expression, purification and characterization of recombinant murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and bovine interleukin-2 from yeast. Gene. 1987;55:287–293. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quakyi I A, Carter R, Rener J, Kumar N, Good M F, Miller L H. The 230-kD gamete surface protein of Plasmodium falciparum is also a target for transmission-blocking antibodies. J Immunol. 1987;139:4213–4217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Struhl K. Naturally occurring poly(dA-dT) sequences are upstream promoter elements for constitutive transcription in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:8419–8423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.24.8419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stura E A, Kang A S, Stefanko R S, Calvo J C, Kaslow D C, Satterthwait A C. Crystallization, sequence and preliminary crystallographic data for transmission-blocking anti-malaria Fab 4B7 with cyclic peptides from the Pfs25 protein of P. falciparum. Acta Crystallogr. 1994;D50:535–542. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994001356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williamson K C, Keister D B, Muratova O, Kaslow D C. Recombinant Pfs230, a Plasmodium falciparum gametocyte protein, induces antisera that reduce the infectivity of Plasmodium falciparum to mosquitoes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1995;75:33–42. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)02507-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zsebo K M, Lu H-S, Fieschko J C, Goldstein L, Davis J, Duker K, Suggs S V, Lai P-H, Bitter G A. Protein secretion from Saccharomyces cerevisiae directed by the prepro-α-factor leader region. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:5858–5865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]