Abstract

Ribonuclease targeting chimeras (RiboTACs) induce degradation of an RNA target by facilitating an interaction between an RNA and a ribonuclease (RNase). We describe the screening of a DNA-encoded library (DEL) to identify binders of monomeric RNase L to provide a compound that induced dimerization of RNase L, activating its ribonuclease activity. This compound was incorporated into the design of a next-generation RiboTAC that targeted the microRNA-21 (miR-21) precursor and alleviated a miR-21-associated cellular phenotype in triple-negative breast cancer cells. The RNA-binding module in the RiboTAC is Dovitinib, a known receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) inhibitor, which was previously identified to bind miR-21 as an off-target. Conversion of Dovitinib into this RiboTAC reprograms the known drug to selectively affect the RNA target. This work demonstrates that DEL can be used to identify compounds that bind and recruit proteins with effector functions in heterobifunctional compounds.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

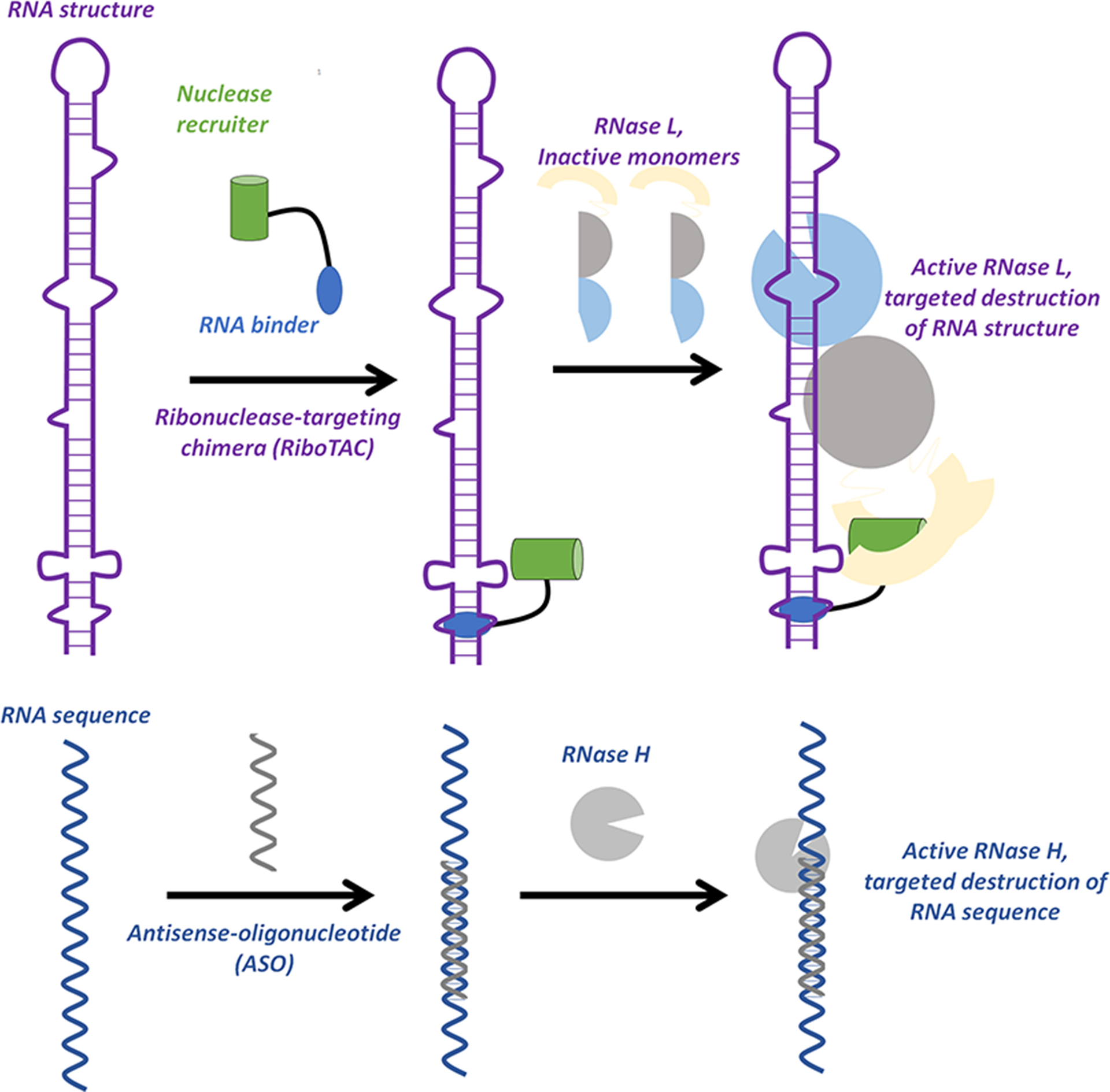

Heterobifunctional molecules can affect various disease processes by facilitating interactions between two biomolecules, where one modulates the function of the other. For example, proteolysis targeting chimeras (ProTACs) comprise a molecule that binds to a target protein and another that binds to E3 ubiquitin ligase to facilitate protein degradation via the proteosome. (1) Likewise, an RNA-binding small molecule and a ribonuclease-recruiting compound comprise ribonuclease targeting chimeras (RiboTACs), eliminating the target RNA by induced proximity (Figure 1). (2) In essence, RiboTACs are the small molecule equivalent of antisense and short interfering (si)RNA-based approaches; however, rather than recognize the RNA sequence, they recognize RNA structure. (2,3) RiboTACs are likely more amenable to medicinal chemistry optimization than oligonucleotide-based modalities and have the potential to eliminate messenger RNAs (mRNAs) that encode difficult to target proteins, thus creating new avenues to target disease.

Figure 1.

Ribonuclease-targeting chimeras (RiboTACs) target RNA structure, rather than the sequence, to catalyze proximity-induced degradation of a target. RiboTACs bind to a target structure and recruit a ribonuclease, RNase L, to degrade the RNA. Antisense-oligonucleotides (ASOs) target the RNA sequence, recruiting RNase H to the RNA–DNA heteroduplex to degrade the RNA target.

RiboTACs are currently designed by first identifying a structure-specific RNA-binding compound. Design can be guided by either the lead identification software, Inforna, (4) which relies on RNA-small molecule binding partners, (5) microarray-based screening, (6) or medicinal chemistry optimization informed by structural modeling experiments, (7–10) among others. The structure-specific compound is then conjugated to a heterocyclic small molecule recruiter of monomeric latent ribonuclease (RNase L), (11) causing the enzyme to dimerize and activating its enzymatic activity. The linker separating the two modules can also be optimized, positioning RNase L near a preferred substrate, for example UNN. (12) The focus of this work is to use a DNA-encoded library (DEL) (13) as a starting point to identify new scaffolds that bind monomeric RNase L. We then determined which compounds dimerize and activate the ribonuclease, as these can be used in the design of a RiboTAC.

To date, DEL screening has been used to identify the small molecule that binds the protein targeted for degradation by ProTACs. (14) The work reported here expands this technology to identify small molecules that bind the effector protein, here RNase L, the other component of these heterobifunctional compounds. Our first generation RiboTACs use a 2-benzylidine-3-thiophenone as an RNase L recruiter (1, Figure 2), optimized from a previously reported small molecule. (15)

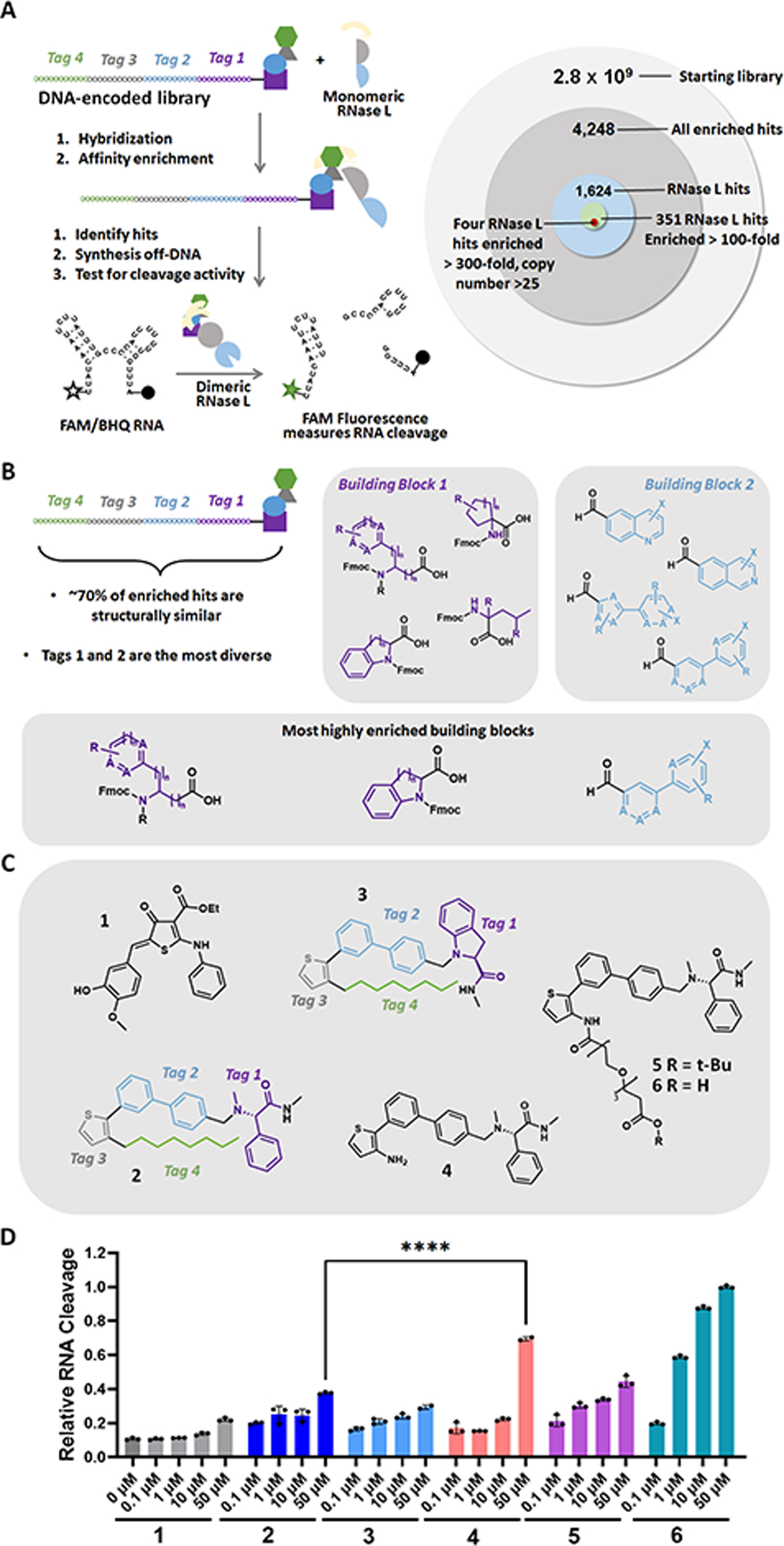

Figure 2.

New RNase L recruiter was identified by screening a DNA-encoded library (DEL). (A) Left: Selection and hit validation scheme for screening the DEL. Right: Schematic depicting refinement of DEL hits to afford the four lead compounds selected for further study (>300-fold enrichment for RNase L binding, >25 copy number). (B) Markush structures of chemical building blocks in the chemical family most highly enriched by RNase L. X and R represent arbitrary substituents, while A represents either C, O, S, or N. (C) Structures of previously reported RNase L recruiter 1, validated RNase L recruiters 2 and 3 from the DEL screening, an analogue of 2 lacking the alkyl chain (4), and analogues of 4 with a polyethylene glycol linker and t-Bu (5) or H (6). (D) Compounds 1–6 induce dose-dependent cleavage of a fluorescently labeled RNA displaying preferential RNase L cleavage sites, indicating that these compounds dimerize and activate RNase L in vitro. Data are reported as “Relative RNA Cleavage”, normalizing fluorescence to the highest level of cleavage observed─upon addition of a 50 μM concentration of 6, which was set to 1. ****, p < 0.0001 as determined by an unpaired t-test. Data are reported as the mean ± SD.

Results and Discussion

Monomeric RNase L was screened against the 2nd generation DELopen (WuXi AppTec) library (16) (2.8 billion compounds) to identify new binders to the ribonuclease (Figure 2A). After affinity enrichment, 4248 unique compounds were identified across three conditions: (i) recombinant GST-RNase L-His6 (n = 1999 compounds); (ii) the GST tag alone (counter screen; n = 380 compounds); and (iii) a no target control (counter screen; n = 2244 compounds). Removing hits present in the two counter screens afforded 1624 compounds specifically enriched for binding to RNase L. Of these, 351 compounds had an enrichment score of at least 100 for RNase L. The enrichment score was calculated from decoding of the DNA tags by next generation sequencing (NGS), considering the corrected copy number, library size, NGS depth, and other normalization factors, as completed by WuXi AppTec (see https://hits.wuxiapptec.com/delopen). A molecule with an enrichment score of 100 is 100 times more abundant in the sequencing data than the average molecule in the library, which has a score of 1. Interestingly, analysis of the DEL identification codes showed that most of the compounds enriched by RNase L belonged to the same compound family (Figure 2B). Additionally, the largest positions of diversity were building blocks 1 and 2 (i.e., tag 1 and tag 2), showing a preference for highly heteroaromatic structures. Building blocks 3 and 4 were unchanged in the most highly enriched compounds, suggesting that the thiophene may contribute to RNase L binding (Figure 2B).

The four compounds with the highest confidence (enrichment scores > 300 and copy number > 25) were selected for further study. The compounds were resynthesized without the encoding DNA tag and were studied for RNase L activation using a fluorescence-based in vitro assay, completed as previously described. (15) In brief, the assay uses an dually labeled RNA [5′ fluorescein (6-FAM) and 3′ black hole quencher (BHQ)] that harbors multiple preferred substates for RNase L (Figure 2A). (15) In the presence of a binder that activates RNase L, the enzyme cleaves the RNA, resulting in an increased fluorescence signal. Here, a previously validated small molecule recruiter, 1, was used as a positive control. (17,18) Two of the four tested compounds, 2 and 3, induced dose-dependent RNA cleavage to a greater extent than 1, indicating RNase L dimerization and activation (Figures 2C,D and S1). Interestingly, 2 and 3 are similar in structure, differing only by the first building block, phenylglycine in 2 and indoline in 3 (Figure 2C). (Note: the structures of the other two compounds were not disclosed by WuXi as they were not chosen for further study. Data for these compounds can be found in Figure S1.) Taken together with the data gleaned from the DEL codes, these data suggest that the aromatic rings and the sulfur atom play critical roles in binding of these small molecules to RNase L.

Prior to incorporating 2 into a next-generation RiboTAC, we verified that 2 indeed induced RNase L dimerization in vitro by Western blotting (Figure S2A) and then sought to determine the position within 2 suitable for conjugation. Previous studies in the ProTAC field have shown that the attachment site for a linker within the recruiting module should be carefully considered such that it does not affect binding. (19) Although the exit vector from the DEL bead could be used as a point of attachment, we hypothesized that the long alkyl chain in 2 was unlikely to affect RNase L binding and would negatively affect solubility. The alkyl chain could, however, orient the molecule for effective binding within the enzyme and thus was modified, rather than eliminated. Therefore, we derivatized this position and assessed RNase L activation. Compound 4, which lacks the alkyl chain, showed enhanced RNA cleavage compared to 2 (p < 0.0001), confirming that the alkyl chain is not required for RNase L binding and dimerization (Figure 2C,D). We then attached a polyethylene glycol linker terminated with a t-butyl ester to yield 5 (Figure 2C). Compound 5 also retained RNase L activation activity, indicating that this compound could be used in the design of a RiboTAC (Figure 2D).

To assess further the ability of this compound to bind to RNase L, we conducted saturation transfer difference (STD) nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (20) and circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopic studies with 6, a compound very similar in structure to 5 and a potential intermediate in the synthesis of a resulting RiboTAC (Figures 2C and S2B,C). STD-NMR spectra showed transfer of magnetization from the compound to RNase L, whereas no transfer was observed between 6 and the control protein lysozyme. Furthermore, CD spectra revealed an increase in signal intensity at 220 nm upon addition of 6, indicative of increased alpha-helical content and consistent with dimerization of RNase L. (21)

Next, we studied this new RNase L recruiter as part of a previously validated RiboTAC that targets the precursor to microRNA-21 (pre-miR-21). (18) MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small noncoding RNAs that are transcribed as primary transcripts that are processed first in the nucleus by Drosha to liberate the precursor miRNA and then in the cytoplasm by Dicer to produce the mature miRNA. The mature miRNA then associates with the Argonaute/RNA-induced silencing complex (AGO/RISC) and binds to the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of complementary mRNAs to translationally repress or cleave them (Figure 3A). (22) In many cancers, miR-21 is highly expressed, including triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), where aberrant expression triggers cancer-associated cellular phenotypes including migration. (23,24)

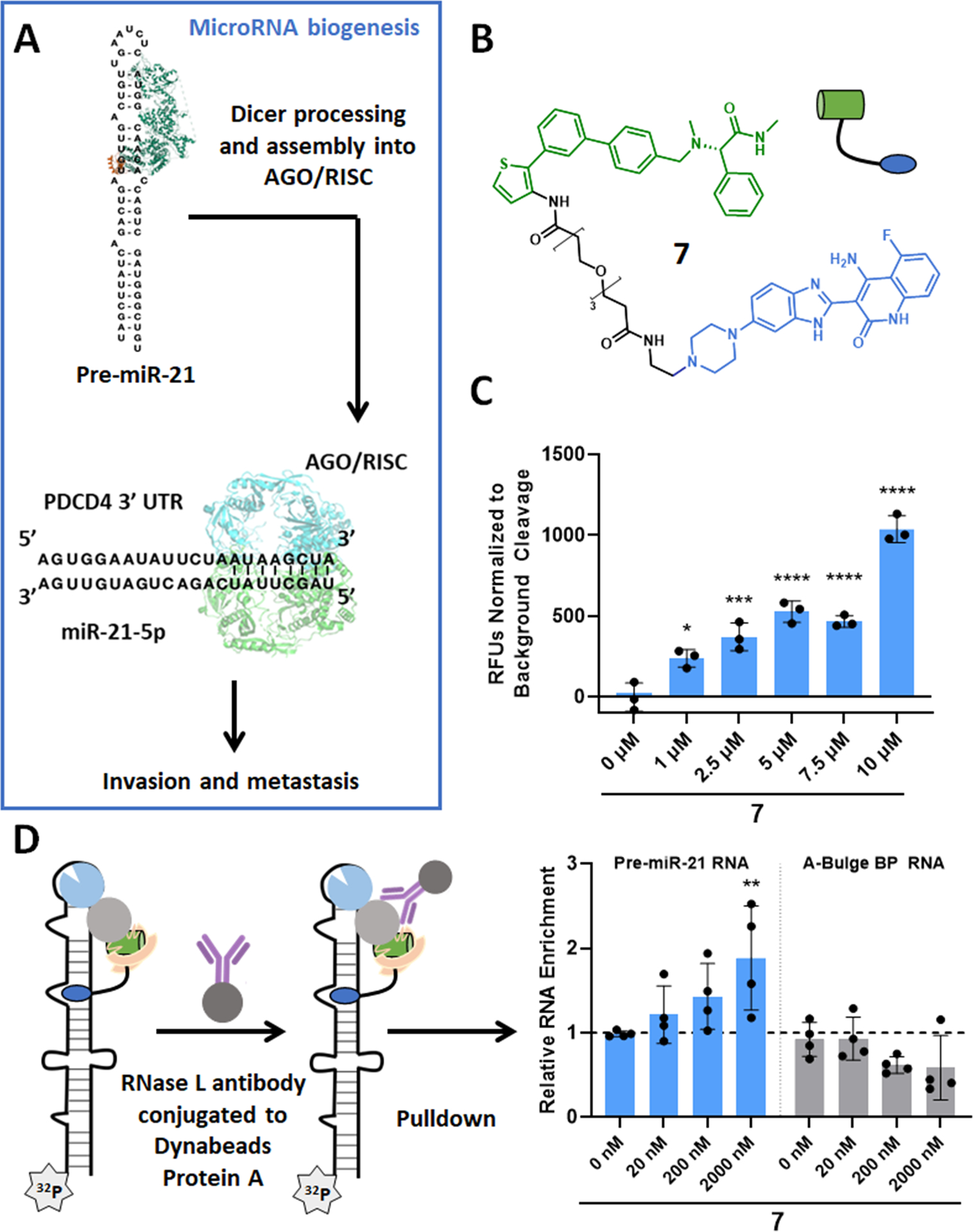

Figure 3.

RiboTAC 7 binds to and cleaves pre-miR-21 in vitro. (A) Schematic representation of mature miR-21 biogenesis and associated downstream pathology. (B) Structure of RiboTAC 7. (C) RiboTAC 7 dose-dependently cleaves a pre-miR-21 construct dually labeled 5′ 6-FAM and 3′ BHQ (n = 3). (D) RiboTAC 7 dose-dependently and selectively induces co-immunoprecipitation of 5′−32P-pre-miR-21 compared to the pre-miR-21 mutant in which the RNA-binding module binding site was mutated from an A-bulge to a base pair (n = 4). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001 as determined by a one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons. Data are reported as the mean ± SD.

To construct a pre-miR-21-targeting RiboTAC, 6 was attached to Dovitinib, a known kinase inhibitor that also binds to the Dicer processing site in pre-miR-21, (18) yielding RiboTAC 7 (Figure 3B). The in vitro interaction between the chimera (7) and pre-miR-21 was characterized using a battery of assays, including direct binding, pre-miR-21 cleavage, occupancy by Competitive Chemical Cross-linking and Isolation by Pull-down (C-Chem-CLIP), and co-immunoprecipitation assays. (25)

RiboTAC 7 bound to pre-miR-21 with a Kd of 4.6 ± 2.1 μM, while no saturable binding (up to 100 μM) was observed to a mutant pre-miR-21 in which the A and U bulge binding sites (18) were mutated to base pairs (Figure S3). These data support that 7 recognizes the structure of pre-miR-21, not its sequence. Additionally, the Kd is similar to a previously reported Dovitinib-derived RiboTAC, indicating that the new RNase L recruiter was not affecting Dovitinib’s affinity for pre-miR-21. (18)

Direct target occupancy was further verified using C-Chem-CLIP. In this assay, the RNA-binding module was conjugated to a diazirine cross-linking module and an alkyne handle for purification, affording Chem-CLIP probe 8 (Figure S4). (18) Radioactively labeled pre-miR-21 was incubated with a constant concentration of 8 and increasing amounts of 7. After cross-linking by irradiation with UV light, the amount of pre-miR-21 pulled down by 8 was measured by its radioactive signal. If the two compounds (7 and 8) share the same binding site, the amount of pre-miR-21 in the pulled down fraction is depleted. Indeed, 7 dose-dependently reduced the amount of pre-miR-21 cross-linked to 8 (Figure S4). No pull-down was observed with a control Chem-CLIP probe that lacked the RNA-binding module (9) (Figure S4). These data further support RiboTAC 7’s specificity for the RNA’s structure.

To confirm ternary complex formation, a pre-miR-21 construct dually labeled with 6-FAM and BHQ was incubated with 7 and RNase L. RiboTAC 7 induced dose-dependent cleavage of pre-miR-21, supporting that the chimera both interacts with pre-miR-21 and functions through an RNase L-mediated mechanism of action (Figure 3C). Further, a co-immunoprecipitation assay using an inactive RNase L protein (mutation in the catalytic site) showed that pre-miR-21, but not its base paired mutant, was pulled down with RNase L in the presence of 7 (Figure 3D). Neither RNA was pulled down in the presence of 6, which lacks the RNA-binding module (Figure S5). These data support that ternary complex formation is essential for the RiboTAC’s mechanism of action.

RiboTAC 7 was next tested in the TNBC cell line MDA-MB-231 to investigate its ability to cleave pre-miR-21 and rescue miR-21-mediated cellular phenotypes. In TNBC cells, miR-21 represses expression of programmed cell death protein 4 (PDCD4). (26) Dysregulation of PDCD4 leads to an increase in the cell’s invasive character and eventually to metastasis. (27)

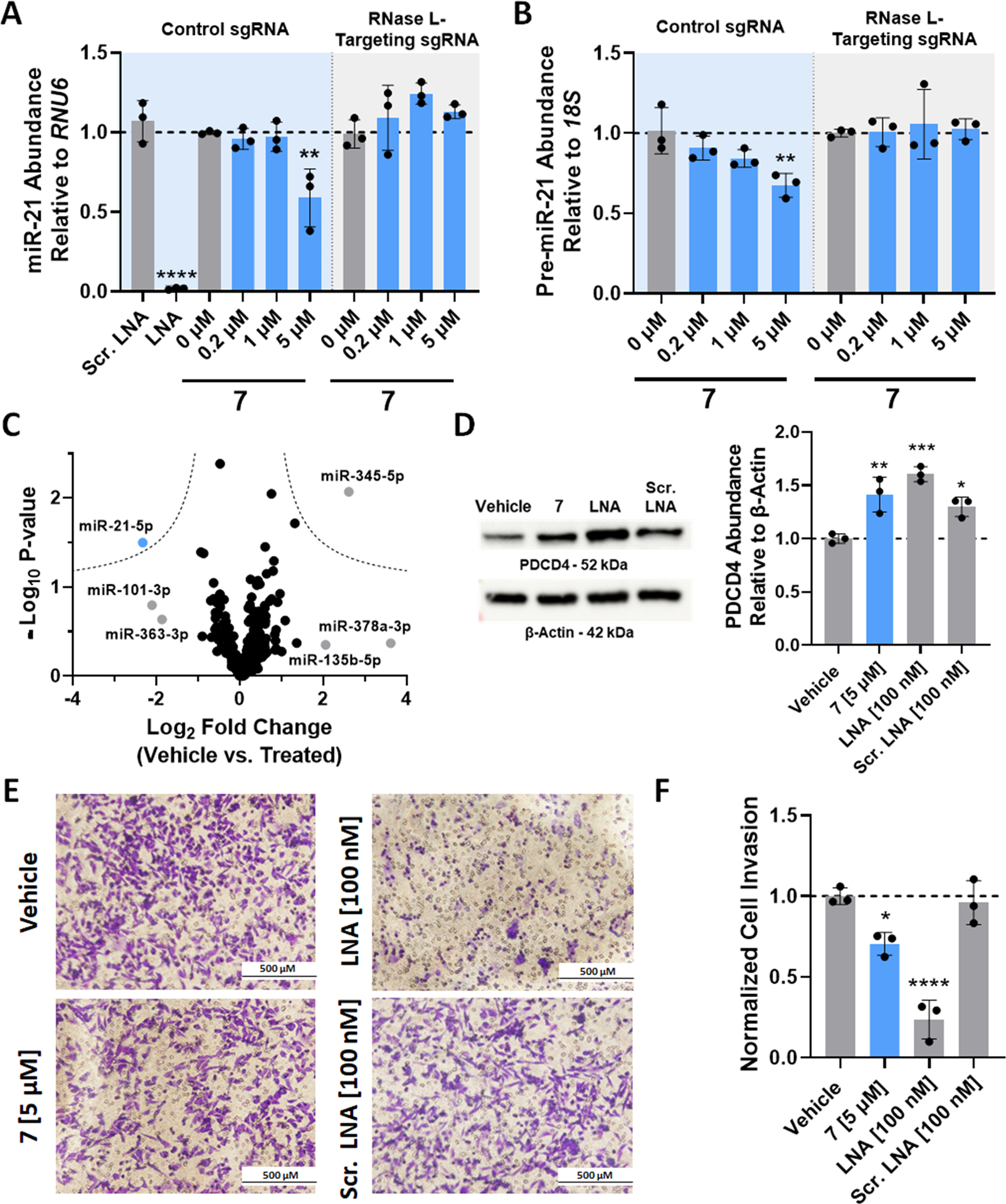

Two CRISPR-modified MDA-MB-231 cell lines with either a scrambled control guide RNA (“Control sgRNA”; RNase L is expressed) or with an RNase L-targeting guide RNA (“RNase L-Targeting sgRNA”; RNase L protein abundance is knocked down) were used to complete these studies. In CRISPR-Control sgRNA cells in which RNase L is expressed, 7 (5 μM) reduced mature and pre-miR-21 abundance by ~40 and ~30%, respectively (p < 0.01; Figure 4A,B; “Control sgRNA”; blue background) after a 48 h treatment, similar to the previously reported Dovitinib-derived RiboTAC that uses 1 as the RNase L recruiter. (18) Knock-down of RNase L by CRISPR (18) rendered 7 inactive (Figure 4A,B; “RNase L-Targeting sgRNA”; gray background), supporting an RNase L-mediated mechanism of action targeted to the miRNA precursor. Importantly, miRNA profiling revealed that 7 selectively down-regulated miR-21 across the transcriptome (p = 0.0317; Figure 4C). The five other miRNAs that were dysregulated by ≥2-fold upon RiboTAC treatment do not harbor the Dovitinib binding site present within miR-21, 5′GAC/3′C_G (gray dots; Figure 4C). Collectively, these data support that 7 selectively cleaves pre-miR-21 in cells.

Figure 4.

RiboTAC 7 alleviates miR-21-associated pathologies in triple-negative breast cancer cells. (A) Effect of RiboTAC 7 on mature miR-21 levels in MDA-MB-231 cells modified by CRISPR with either a control guide RNA (“Control sgRNA”; express RNase L; blue background) or with an RNase L-targeting sgRNA (“RNase L-Targeting sgRNA”; gray background), as determined by RT-qPCR (n = 3 for both cell lines). (B) Effect of RiboTAC 7 on pre-miR-21 levels in MDA-MB-231 cells modified by CRISPR with either a control guide RNA (“Control sgRNA”; expresses RNase L; blue background) or with an RNase L-targeting sgRNA (“RNase L-Targeting sgRNA”; gray background), as determined by RT-qPCR (n = 3 for both cell lines). (C) Results of the miRNA profiling experiment showing that miR-21 is selectively down-regulated by RiboTAC 7 (n = 377 miRNAs; three biological replicates). Dotted lines represent a false discovery rate of 5% and variance of S0(0.1). (D) Left: Representative Western blot image of PDCD4 protein abundance upon treatment of MDA-MB-231 cells modified by CRISPR with the control sgRNA cells (express RNase L) with RiboTAC 7 (n = 3). Right: Quantification of Western blots (n = 3). (E) Representative images of the invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells modified by CRISPR with the control sgRNA cells (express RNase L), a miR-21-associated phenotype, with or without RiboTAC 7-treatment, as determined by a Boyden chamber assay. (F) Quantification of Boyden chamber invasion assays (n = 3, average of four images per biological replicate). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001, as determined by a one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons. Data are reported as the mean ± SD.

We next completed a time-course for RiboTAC degradation of pre-miR-21 and compared it to its cellular permeability. Permeability studies showed that RiboTAC 7 accumulated in cells at a concentration of 3.6 ± 1.2 μM after 48 h, reaching a plateau after about 8 h and corresponding to an uptake half-life of 2.4 h (Figure S6A). A time course of 7’s activity showed that reduction of pre-miR-21 was first observable after 48 h of treatment (no reduction was observed at earlier time points, 4–24 h; Figure S6B).

RiboTAC 7 was then assessed for its ability to affect protein levels by deactivation of a miR-21-mediated cancer circuit, i.e., de-repression of PDCD4. Western blot analysis of PDCD4 showed that protein levels were increased by ~40% (p < 0.01) after treatment with 7 (5 μM) in the CRISPR-Control sgRNA MDA-MB-231 cells (express RNase L; Figure 4D). Proteome-wide analysis was also completed to study the effects of 7 and a locked nucleic acid (LNA) oligonucleotide that targets miR-21–5p on the proteome. The concentrations tested of both provided similar activity (5 μM concentration of 7 and 100 nM concentration of the LNA), as assessed by their effect on PDCD4 levels, ~40% enhancement. Global analysis showed that of the 3176 proteins detected, 0.6 and 3.1% were affected by treatment with 7 and the LNA, respectively (Figure S7A,B). [Note: PDCD4 was not detected in any of the samples analyzed by proteomics.] A cumulative distribution analysis was completed to study the effect on the abundance of proteins that are encoded by mRNAs with a miR-21–5p binding site in their 3′ UTRs, as determined by Human TargetScan v.7.2. (28) This cumulative analysis showed a statistically significant increase in the abundance of these miR-21-repressed proteins upon treatment with 7 (p = 0.0016) or the LNA (p = 0.0041), although the changes in the abundances of these targets are modest. Neither modality affected proteins that are direct targets of miRNA let-7b-5p, further supporting that RiboTAC 7 selectively deactivates a miR-21-mediated cancer circuit in cells (Figure S7C,D).

The effect of the RiboTAC on a miR-21-associated invasive phenotype was next assessed. Treatment with 5 μM 7 reduced the invasiveness of MDA-MB-231 cells by ~30% (p < 0.05) (Figure 4E,F). Notably, forced expression of pre-miR-21 induced an invasive phenotype in MCF-10A cells, a model of healthy breast epithelial cells that do not aberrantly express miR-21. (29) This phenotype was rescued by 7-treatment (Figure S8). While forced expression of a mutant pre-miR-21 in which the Dovitinib-binding site is mutated also produced an invasive phenotype, the cells were insensitive to treatment with 7 (Figure S8).

Although our transcriptome- and proteome-wide studies did not suggest that this alleviation of invasion is due to inhibition of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), we verified RiboTAC mode of action by studying its effect on RTK signaling, namely, the phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) to afford pERK. (30,31) Here, we used an alkylated derivative of Dovitinib (10) that mimics the linker used to create the RiboTAC. Indeed, the derivative dose-dependently inhibited phosphorylation of ERK with an IC50 of ~1 μM (Figure S9) in agreement with previous reports. (30,31) In contrast, RiboTAC 7 had no effect on the levels of ERK or pERK (Figure S9), supporting a miR-21-, not RTK-, mediated mode of action. Collectively, these data, in conjunction with miRNome- and proteome-wide profiling, support 7’s selectivity for the structured Dicer processing site in pre-miR-21 and that rescue of the invasive phenotype is due to reduction of miR-21.

Previous work to define heterocyclic ligands that activate RNase L were identified by using an enzymatic activity screen. (15) In the current approach, we find that a simple, democratized DEL binding screen can identify various binders of RNase L. Although the compounds were identified by a simple binding screen, two of the four top compounds were validated to also activate RNase L. The best activator was then used as a ribonuclease recruiter in a RiboTAC, providing novel chemical matter that can be used to recruit effector domains. Interestingly, 1 and 4 both contain a thiophene-like ring substituted with an amine, suggesting that this chemical motif may contribute to interactions with RNase L. Additionally, both recruiters demonstrate similar activities against miR-21-driven pathologies when incorporated into RiboTACs, leaving further opportunity for optimization of RNase L-recruiting small molecules. Notably, the RNA-binding module used herein is an RTK inhibitor, reprogrammed for activity and selectivity of an RNA off-target. (18) The off-target, pre-miR-21, was identified from a selection platform that studies the RNA-binding capacity of small molecules and known drugs. Those studies, (18) as well as others, (32,33) demonstrated that protein-targeted small molecules indeed bind RNA and modulate RNA function in cells.

While DEL screening has previously been used to identify novel protein binders that have been incorporated into ProTACs, (14) the technology has not been as successful for finding new E3 ligase recruiters. (34–36) Our work demonstrates that DEL technology can be used to identify compounds that can recruit ribonucleases, suggesting that this approach could identify small molecules that recruit other ribonucleases, of particular interest those with different subcellular localizations, tissue distributions, or substrate specificities. Further, this approach could be used broadly in the area of chemically induced proximity, not only for RNA targets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. L. Childs-Disney for assistance with the writing of this manuscript and the DELopen team at WuXi AppTec for assistance with deconvoluting the DEL screening hits.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants (R01 CA249180 and R35 NS116846 to M.D.D. and R01 GM145886 to A.A.) and the Scheller Graduate Student Fellowship (to S.M.M). Purchase of the 600 MHz NMR spectrometer was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (S10OD021550).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.2c07217.

Figures S1–S9, Table S1, in vitro, cellular and synthetic methods and schemes, and compound characterization (PDF)

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): MDD is a founder of Expansion Therapeutics.

References

- 1.Burslem GM; Crews CM Proteolysis-targeting chimeras as therapeutics and tools for biological discovery. Cell 2020, 181, 102–114, DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.11.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costales MG; Matsumoto Y; Velagapudi SP; Disney MD Small molecule targeted recruitment of a nuclease to RNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 6741–6744, DOI: 10.1021/jacs.8b01233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts TC; Langer R; Wood MJA Advances in oligonucleotide drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2020, 19, 673–694, DOI: 10.1038/s41573-020-0075-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Velagapudi SP; Gallo SM; Disney MD Sequence-based design of bioactive small molecules that target precursor microRNAs. Nat. Chem. Biol 2014, 10, 291–297, DOI: 10.1038/nchembio.1452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Disney MD; Labuda LP; Paul DJ; Poplawski SG; Pushechnikov A; Tran T; Velagapudi SP; Wu M; Childs-Disney JL Two-dimensional combinatorial screening identifies specific aminoglycoside-RNA internal loop partners. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 11185–11194, DOI: 10.1021/ja803234t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sztuba-Solinska J; Shenoy SR; Gareiss P; Krumpe LRH; Le Grice SFJ; O’Keefe BR; Schneekloth JS Identification of biologically active, HIV TAR RNA-binding Small molecules using small molecule microarrays. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 8402–8410, DOI: 10.1021/ja502754f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen JL; Zhang P; Abe M; Aikawa H; Zhang L; Frank AJ; Zembryski T; Hubbs C; Park H; Withka J; Steppan C; Rogers L; Cabral S; Pettersson M; Wager TT; Fountain MA; Rumbaugh G; Childs-Disney JL; Disney MD Design, optimization, and study of small molecules that target tau pre-mRNA and affect splicing. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 8706–8727, DOI: 10.1021/jacs.0c00768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andrałojć W; Ravera E; Salmon L; Parigi G; Al-Hashimi HM; Luchinat C Inter-helical conformational preferences of HIV-1 TAR-RNA from maximum occurrence analysis of NMR data and molecular dynamics simulations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2016, 18, 5743–5752, DOI: 10.1039/C5CP03993B [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stelzer AC; Frank AT; Kratz JD; Swanson MD; Gonzalez-Hernandez MJ; Lee J; Andricioaei I; Markovitz DM; Al-Hashimi HM Discovery of selective bioactive small molecules by targeting an RNA dynamic ensemble. Nat. Chem. Biol 2011, 7, 553–559, DOI: 10.1038/nchembio.596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shortridge MD; Walker MJ; Pavelitz T; Chen Y; Yang W; Varani G A macrocyclic peptide ligand binds the oncogenic microRNA-21 precursor and suppresses Dicer processing. ACS Chem. Biol 2017, 12, 1611–1620, DOI: 10.1021/acschembio.7b00180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han Y; Donovan J; Rath S; Whitney G; Chitrakar A; Korennykh A Structure of human RNase L reveals the basis for regulated RNA decay in the IFN response. Science 2014, 343, 1244–1248, DOI: 10.1126/science.1249845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Washenberger CL; Han J-Q; Kechris KJ; Jha BK; Silverman RH; Barton DJ Hepatitis C virus RNA: dinucleotide frequencies and cleavage by RNase L. Virus Res. 2007, 130, 85–95, DOI: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.05.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mannocci L; Leimbacher M; Wichert M; Scheuermann J; Neri D 20 years of DNA-encoded chemical libraries. Chem. Commun 2011, 47, 12747–12753, DOI: 10.1039/c1cc15634a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Disch JS; Duffy JM; Lee ECY; Gikunju D; Chan B; Levin B; Monteiro MI; Talcott SA; Lau AC; Zhou F; Kozhushnyan A; Westlund NE; Mullins PB; Yu Y; von Rechenberg M; Zhang J; Arnautova YA; Liu Y; Zhang Y; McRiner AJ; Keefe AD; Kohlmann A; Clark MA; Cuozzo JW; Huguet C; Arora S Bispecific Estrogen Receptor α Degraders Incorporating Novel Binders Identified Using DNA-Encoded Chemical Library Screening. J. Med. Chem 2021, 64, 5049–5066, DOI: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thakur CS; Jha BK; Dong B; Gupta JD; Silverman KM; Mao H; Sawai H; Nakamura AO; Banerjee AK; Gudkov A; Silverman RH Small-molecule activators of RNase L with broad-spectrum antiviral activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2007, 104, 9585–9590, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0700590104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lerner RA; Brenner S DNA-Encoded compound libraries as open source: a powerful pathway to new drugs. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl 2017, 56, 1164–1165, DOI: 10.1002/anie.201612143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costales MG; Aikawa H; Li Y; Childs-Disney JL; Abegg D; Hoch DG; Velagapudi SP; Nakai Y; Khan T; Wang KW; Yildirim I; Adibekian A; Wang ET; Disney MD Small-molecule targeted recruitment of a nuclease to cleave an oncogenic RNA in a mouse model of metastatic cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2020, 117, 2406–2411, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1914286117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang P; Liu X; Abegg D; Tanaka T; Tong Y; Benhamou RI; Baisden J; Crynen G; Meyer SM; Cameron MD; Chatterjee AK; Adibekian A; Childs-Disney JL; Disney MD Reprogramming of protein-targeted small-molecule medicines to RNA by ribonuclease recruitment. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143, 13044–13055, DOI: 10.1021/jacs.1c02248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Troup RI; Fallan C; Baud MGJ Current strategies for the design of PROTAC linkers: a critical review. Explor. Target Antitumor Ther 2020, 1, 273–312, DOI: 10.37349/etat.2020.00018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daou S; Talukdar M; Tang J; Dong B; Banerjee S; Li Y; Duffy NM; Ogunjimi AA; Gaughan C; Jha BK; Gish G; Tavernier N; Mao D; Weiss SR; Huang H; Silverman RH; Sicheri F A phenolic small molecule inhibitor of RNase L prevents cell death from ADAR1 deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2020, 117, 24802–24812, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2006883117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenfield NJ Using circular dichroism spectra to estimate protein secondary structure. Nat. Protoc 2006, 1, 2876–2890, DOI: 10.1038/nprot.2006.202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bartel DP MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004, 116, 281–297, DOI: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00045-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krichevsky AM; Gabriely G miR-21: a small multi-faceted RNA. J. Cell. Mol. Med 2009, 13, 39–53, DOI: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00556.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng Y-H; Tsao C-J Emerging role of microRNA-21 in cancer. Biomed. Rep 2016, 5, 395–402, DOI: 10.3892/br.2016.747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guan L; Disney MD Covalent small-molecule–RNA complex formation enables cellular profiling of small-molecule–RNA interactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl 2013, 52, 10010–10013, DOI: 10.1002/anie.201301639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frankel LB; Christoffersen NR; Jacobsen A; Lindow M; Krogh A; Lund AH Programmed Cell Death 4 (PDCD4) is an important functional target of the microRNA miR-21 in breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem 2008, 283, 1026–1033, DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M707224200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu S; Wu H; Wu F; Nie D; Sheng S; Mo Y-Y MicroRNA-21 targets tumor suppressor genes in invasion and metastasis. Cell Res. 2008, 18, 350–359, DOI: 10.1038/cr.2008.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agarwal V; Bell GW; Nam J-W; Bartel DP Predicting effective microRNA target sties in mammalian mRNAs. eLife 2015, 4, e05005 DOI: 10.7554/eLife.05005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yan LX; Wu QN; Zhang Y; Li YY; Liao DZ; Hou JH; Fu J; Zeng MS; Yun JP; Wu QL; Zeng YX; Shao JY Knockdown of miR-21 in human breast cancer cell lines inhibits proliferation, in vitro migration and in vivotumor growth. Breast Cancer Res. 2011, 13, R2, DOI: 10.1186/bcr2803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang CW; Jang KW; Sohn J; Kim S-M; Pyo K-H; Kim H; Yun MR; Kang HN; Kim HR; Lim SM; Moon YW; Paik S; Kim DJ; Kim JH; Cho BC Antitumor Activity and Acquired Resistance Mechanism of Dovitinib (TKI258) in RET-Rearranged Lung Adenocarcinoma. Mol. Cancer Ther 2015, 14, 2238–2248, DOI: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaur S; Chen L; Ann V; Lin W-C; Wang Y; Chang VHS; Hsu NY; Shia H-S; Yen Y Dovitinib synergizes with oxaliplatin in suppressing cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells regardless of RAS-RAF mutation status. Mol. Cancer Ther 2014, 13, 21, DOI: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Velagapudi SP; Costales MG; Vummidi BR; Nakai Y; Angelbello AJ; Tran T; Haniff HS; Matsumoto Y; Wang ZF; Chatterjee AK; Childs-Disney JL; Disney MD Approved anti-cancer drugs target oncogenic non-coding RNAs. Cell Chem. Biol 2018, 25, 1086–1094.e7, DOI: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2018.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tong Y; Gibaut QMR; Rouse W; Childs-Disney JL; Suresh BM; Abegg D; Choudhary S; Akahori Y; Adibekian A; Moss WN; Disney MD Transcriptome-Wide Mapping of Small-Molecule RNA-Binding Sites in Cells Informs an Isoform-Specific Degrader of QSOX1 mRNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2022, 144, 11620–11625, DOI: 10.1021/jacs.2c01929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ishida T; Ciulli A E3 ligase ligands for PROTACs: how they were found and how to discover new ones. SLAS Discovery 2021, 26, 484–502, DOI: 10.1177/2472555220965528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spradlin JN; Hu X; Ward CC; Brittain SM; Jones MD; Ou L; To M; Proudfoot A; Ornelas E; Woldegiorgis M; Olzmann JA; Bussiere DE; Thomas JR; Tallarico JA; McKenna JM; Schirle M; Maimone TJ; Nomura DK Harnessing the anti-cancer natural product nimbolide for targeted protein degradation. Nat. Chem. Biol 2019, 15, 747–755, DOI: 10.1038/s41589-019-0304-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang X; Crowley VM; Wucherpfennig TG; Dix MM; Cravatt BF Electrophilic PROTACs that degrade nuclear proteins by engaging DCAF16. Nat. Chem. Biol 2019, 15, 737–746, DOI: 10.1038/s41589-019-0279-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.