Abstract

Hypophosphatasia (HPP) is a rare inborn error of metabolism that presents variably in both age of onset and severity. HPP is caused by pathogenic variants in the ALPL gene, resulting in low activity of tissue nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNSALP). Patients with HPP tend have a similar pattern of elevation of natural substrates that can be used to aid in diagnosis. No formal diagnostic guidelines currently exist for the diagnosis of this condition in children, adolescents, or adults. The International HPP Working Group is a comprised of a multidisciplinary team of experts from Europe and North America who have expertise in the diagnosis and management of patients with HPP. This group reviewed 93 papers through a Medline, Medline In-Process, and Embase search for the terms “HPP” and “hypophosphatasia” between 2005 and 2020 and that explicitly address either the diagnosis of HPP in children, clinical manifestations of HPP in children, or both. Two reviewers independently evaluated each full-text publication for eligibility and studies were included if they were narrative reviews or case series/reports that concerned diagnosis of pediatric HPP or included clinical aspects of patients diagnosed with HPP. This review focused on 15 initial clinical manifestations that were selected by a group of clinical experts.

The highest agreement in included literature was for pathogenic or likely pathogenic ALPL variant, elevation of natural substrates, and early loss of primary teeth. The highest prevalence was similar, including these same three parameters and including decreased bone mineral density. Additional parameters had less agreement and were less prevalent. These were organized into three major and six minor criteria, with diagnosis of HPP being made when two major or one major and two minor criteria are present.

Keywords: Alkaline phosphatase, ALPL, HPP diagnosis in children, hypophosphatasia, osteomalacia, rickets

Introduction

Hypophosphatasia (HPP) is a rare inborn error of metabolism that causes an extremely variable and phenotype that tends to be progressive in nature. The prevalence of the severe forms of HPP has been estimated to be 1/300,000 in Europe, and 1/100,000 in Canada [1, 2], with evidence of higher incidence of less severe forms of HPP. HPP has been classified based on age at first disease manifestation, including: perinatal, infantile, childhood, and adulthood HPP [3–6]. Patients with perinatal and infantile HPP have classically been described with severe rickets, thoracic dystrophy, respiratory failure, hearing loss, and vitamin B6-responsive seizures [7, 8]. Until recently, these patients seldom survived [9]. Although there have been gaps in recognition for patients with perinatal and infantile HPP, the presentation is not subtle or ambiguous, so new guidelines are not required to ensure accurate diagnosis [10].

Childhood HPP has been classically described with rickets, bowing of the long bones, short stature, craniosynostosis, pain, and motor delays [11]. More recent research has strongly suggested increased rates of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, sleep disturbances, and behavioral regulation challenges [12]. HPP is caused by pathogenic variants in the ALPL gene, resulting in decreased activity of tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNSALP) [13]. Decreased ALP activity is easily detected on routine biochemical testing and provides helpful screening for the affected. Patients with childhood HPP may have either autosomal dominant HPP or autosomal recessive HPP, with a trend toward more severe disease in those patients with recessive HPP [14, 15]. Patients with HPP also frequently, but not always, have elevations in the natural substrates of alkaline phosphatase [16]. Most commonly, plasma pyridoxal-5′ phosphate (PLP) and urine phosphoethanolamine (PEA) are quantified [17]. Inorganic pyrophosphate is an additional natural substrate of alkaline phosphatase that is often elevated in plasma and urine in HPP, but it is not frequently measured to lack of widely available testing [18].

Although there is significant agreement regarding the typical biochemical features and clinical presentation of HPP in children and adolescents, formal diagnostic guidelines do not yet exist. This creates challenges for accurate and timely diagnosis of patients, particularly for those patients who may present atypically. Accurate diagnosis is of particular interest given that the enzyme replacement therapy asfotase alfa has been available in the USA, Canada, EU, and other jurisdictions since 2015 [19].

There have been recent efforts to create diagnostic pathways for children and adolescents with HPP. One such pathway integrates known clinical findings (Table 1) for children with HPP along with the presence of low ALP and evaluation for alternate causes of low ALP [20]. This diagnostic pathway represents an important advance for two reasons. First, it integrates low age- and sex-adjusted ALP as the key laboratory finding of concern [21]. Second, that it acknowledges that while typical radiographic features of HPP can be confirmatory, their absence is not uncommon and should prompt additional biochemical or molecular evaluation to confirm the diagnosis.

Table 1.

Clinical manifestations associated with HPP in children

| Bone and mineral metabolism | |

| Impaired mineralization and rickets | |

| Excess of fractures | |

| Fracture healing delay or nonunion | |

| Genu valgum/varum | |

| Short stature | |

| Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) | |

| Ophthalmic calcifications | |

| Hypercalcemia | |

| Hyperphosphatemia | |

| Musculoskeletal/rheumatological-like | |

| Myopathy | |

| Chronic muscle, bone, and joint pain | |

| Altered gait | |

| Impaired mobility | |

| Motor delay | |

| Dental | |

| Premature atraumatic loss of deciduous teeth | |

| Dental abnormalities (abnormal tooth shape and color, enamel thinning/hypoplasia, loss of alveolar bone, enlarged pulp chambers) | |

| Premature loss of permanent teeth | |

| Recurrent and severe caries and periodontal diseases | |

| Renal | |

| Hypercalciuria | |

| Nephrocalcinosis | |

| Nephrolithiasis | |

| Neurological | |

| Vitamin B6-responsive seizures | |

| Craniosynostosis | |

| Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder | |

| Poor Sleep Quality |

The HPP International Working Group is comprised of a multidisciplinary group of HPP experts, who have experience in the diagnosis of this condition. The goal of this group is to understand the current state and variability of hypophosphatasia diagnosis [22] and to create guidelines for the diagnosis of children and adolescents with HPP as a function of this article and to create separate guidelines for the diagnosis of adults with HPP [22]. We therefore conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis with two main questions: (1) to investigate the opinion and agreement of clinical experts from the existing literature on the diagnosis of HPP, and (2) the prevalence of those clinical manifestations present in HPP patients.

Methods

Our reporting follows the Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) [23].

Data sources

We searched Medline, Medline In-Process, and Embase, from January 1, 2005 to September 9th, 2020, using the following keywords: HPP and hypophosphatasia. The search, limited to human participants, used MeSH terms in various combinations to increase search sensitivity. Searching reference lists of publications of included studies, relevant narrative reviews and guidelines provided another strategy for identifying additional references. Since this literature review concerned pediatric and adolescent cases with a diagnosis of childhood HPP, the inclusive age range was 6 months to 18 years per the commonly used HPP nosology.

Study selection

Paired reviewers screened the studies in 2 stages: (1) title and abstract and (2) full text. On retrieval of candidate abstracts, two reviewers independently evaluated each full-text publication for eligibility, resolving conflicts by discussion. Studies were included if they were (1) narrative reviews, or case series/reports explicitly addressed the diagnosis of pediatric HPP, and/or (2) case series and case reports included one or more patients diagnosed with HPP or with suspected HPP and described one or more of the clinical manifestations of interest. Only articles published in English are included in this analysis.

Diagnostic laboratory parameters and manifestations of interest

The review focused on 15 initial clinical manifestations, and laboratory parameters of interest for diagnosing pediatric HPP (Table 2), which were identified through consultation with clinical experts, who had at least 5-year experience in treating patients with HPP.

Table 2.

Initial parameters and manifestations for pediatric HPP

| Biochemical | |

| 1 | Elevation of natural substrates of TNSALP (PLP, PEA, PPi) |

| Clinical | |

| 2 | Early non traumatic loss of primary teeth |

| 3 | Presence of rickets on radiograph |

| 4 | Short stature |

| 5 | Delayed motor milestones |

| 6 | Chronic musculoskeletal pain |

| 7 | Impaired mobility |

| 8 | Genu valgum/varum |

| 9 | Craniosynostosis |

| 10 | Decreased bone mass density/ osteoporosis |

| 11 | Nephrocalcinosis/nephrolithiasis |

| 12 | B-6 responsive seizures |

| 13 | Low muscle tone |

| Familial/Genetic | |

| 14 | Family history on an HPP first degree relative |

| 15 | Pathogenic or likely pathogenic ALPL variant* |

TNSALP, tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase; PLP, pyridoxal phosphate; PEA, phosphoethanolamine; PPi, inorganic pyrophosphate; BMD, bone mineral density; CPPD, calcium pyrophosphate deposition; ALPL, alkaline phosphatase gene

*ALPL VUS variants could be reclassified to pathogenic or likely pathogenic and used as a diagnostic characteristic only in presence of additional supporting information, such as if the variant segregates with HPP phenotype in other family members or functional studies strongly suggest that the variant is damaging

Data abstraction

Paired reviewers, using a standardized form, independently extracted data including author; year; country; patient demographics; and diagnostic laboratory parameters and manifestations of paediatric HPP. For studies reporting diagnostic manifestations, based on the description, two authors independently judged whether this feature is strongly suggested or may or may not be present or was not mentioned and solved the conflicts by asking a third reviewer. When studies reported diagnostic criteria to HPP referring to the same references, we regard the authors having the same views of pediatric HPP diagnosis. For studies that reported paediatric HPP cases, we extracted the prevalence of each clinical manifestations reported.

Data analysis

For each clinical diagnostic manifestation and laboratory parameter of interest, we described the proportion of strongly suggested, may or may not be present. To minimize small study effects, we used the fixed-effect model to pool the proportion of clinical features using meta-proportion model. Considering that most studies were small case studies, we conducted a subgroup analysis by sample size hypothesizing studies with greater than 10 cases that would provide lower but accurate proportion than studies with less than 10 cases. We performed meta regression to explore the subgroup difference and considered P<0.05 as the significant difference. All primary analyses were performed in STATA (version 15.1).

Results

Study characteristics

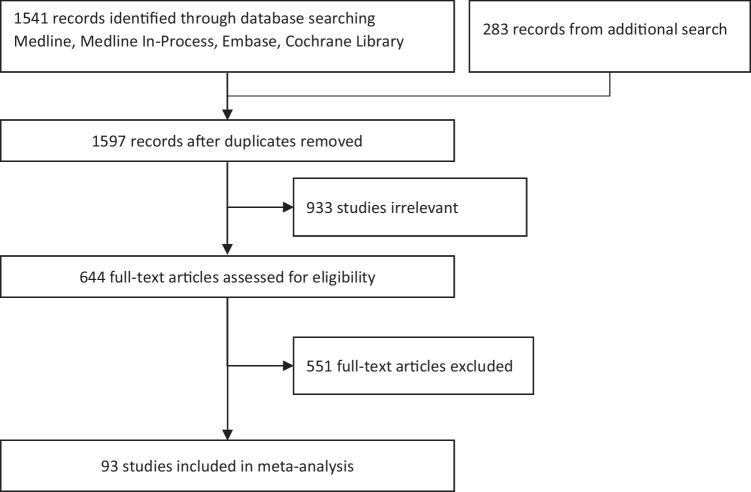

The initial literature review identified a total of 1541 publications, with an additional 56 publications added from a secondary search after duplicates were removed. 644 of these publications were considered potentially eligible for inclusion based on the article title and review of the abstract, and 93 studies were eventually included based on review of the full text and concerned the diagnosis and clinical manifestations of HPP in children. 36 (39%) reported diagnostic principles and criteria specific to pediatric HPP, 41 (44%) addressed manifestations of pediatric HPP, and the rest 16 (17%) reported both aspects. The majority of the articles (61%) were published between 2016 and 2020, reflecting the accelerating interest in this condition. Fig. 1 presents the study selection diagram and Table 3 presents more characteristic information of included studies.

Fig. 1.

Study selection diagram

Table 3.

Demographic/characteristics of included articles (n=93)

| Characteristic (n=93) | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Scope | |

| Diagnosis of HPP | 36 (39) |

| Characteristics of HPP patients | 41 (44) |

| Both | 16 (17) |

| Year | |

| 2005-2010 | 18 (19) |

| 2011-2015 | 19 (20) |

| 2016-2020 | 56 (61) |

| Regions | |

| Asia | 24 (26) |

| Europe | 42 (45) |

| North America | 24 (27) |

| South America | 1 (1) |

| Multi-continents | 2 (2) |

Agreement of the 15 diagnostic characteristics of interest with published data on HPP diagnosis in children

A total of 15 diagnostic characteristics of HPP in children were identified in the 52 relevant articles with varying prevalence. The presence of a pathogenic or likely pathogenic ALPL variant was the most strongly suggested in 41 articles (79%). Similarly, elevation of natural substrates such as PLP, PEA, or PPi was nearly as strongly suggested in 37 articles (71%). Early, nontraumatic tooth loss was the most commonly discussed clinical finding in 32 articles (61%). A minority of the studies showed features such as presence of rickets on radiograph, short stature, delayed motor milestones, chronic musculoskeletal pain, impaired mobility, genu valgum/varum, craniosynostosis, decreased bone mineral density/osteoporosis, family history of HPP, nephrocalcinosis, vitamin B6-responsive seizures, or low muscle tone. In many of these cases, the issue wasn’t that they weren’t strongly suggested, but that they weren’t mentioned at all.

Pooled prevalence of diagnostic characteristics of interest in selected articles in childhood HPP patients

The authors were curious about the tendency for many seemingly important clinical characteristics to fail to be mentioned in the articles, which led us to look at this in a slightly different way using pooled prevalence. Of the 57 studies reporting the prevalence of diagnostic features, 12 included more than 10 cases with a median of 26, ranging from 10 to 269 cases, and 45 included less than 10 cases with a median of 2 cases, ranging from 1 to 7 cases. We observed a significant subgroup difference between studies with greater than 10 cases and less than 10 cases (P<0.01). Table 4 presents the pooled prevalence of diagnostic features of studies with more than 10 patients, which show that 87% if patients would present with a pathogenic or likely pathogenic ALPL variant and 77% present with elevation of natural substrates (PLP, PEA, PPi). Of the remaining thirteen clinical features, only two had pooled prevalence greater than 50%: early nontraumatic loss of primary teeth and decreased bone mineral density/osteoporosis, both with 57%. At least half of the patients would not present with the rest of the laboratory parameters and manifestations.

Table 4.

Prevalence of diagnostic laboratory parameters and manifestations reported by studies ≥ 10 cases

| Diagnostic features | Number of studies | Number of cases | Pooled prevalence, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathogenic or likely pathogenic ALPL variant | 8 | 278 | 87 (82, 90) |

| Elevation of natural substrates (PLP, PEA, PP) | 5 | 118 | 77 (69, 84) |

| Early non traumatic loss of primary teeth | 7 | 253 | 57 (51, 63) |

| Decreased bone mass density/osteoporosis | 4 | 49 | 57 (43, 70) |

| Presence of rickets on radiograph | 4 | 96 | 31 (23, 41) |

| Short stature | 5 | 159 | 40 (33, 48) |

| Delayed motor milestones | 5 | 173 | 44 (37, 51) |

| Chronic musculoskeletal pain | 5 | 216 | 32 (27, 39) |

| Impaired mobility | 4 | 173 | 43 (36, 50) |

| Genu valgum/varum | 3 | 111 | 41 (32, 50) |

| Craniosynostosis | 4 | 199 | 22 (17, 28) |

| Family history on a first degree relative | 3 | 195 | 35 (29, 42) |

| Nephrocalcinosis/nephrolithiasis | 5 | 255 | 12 (8, 16) |

| Low muscle tone | 4 | 241 | 38 (32, 44) |

| B6-responsive seizures | 6 | 282 | 15 (11, 20) |

PLP, pyridoxal phosphate; PEA, phosphoethanolamine; PPi, inorganic pyrophosphate. Diagnostic characteristics presenting a pooled prevalence over 50% are indicated in bold

Based on pooled prevalence in the included studies with greater than 10 cases, diagnostic features were initially classified as major diagnostic criteria (n=4) with a pooled prevalence of greater than 50% and minor diagnostic criteria (n=11). The proposal of the authors is that integration of major and minor criteria could be used to provide a diagnostic framework for childhood HPP. In this instance, a diagnosis of childhood HPP can be made if either two major criteria are present, or one major and two minor criteria are present. A caveat to this framework is that although both the presence of a pathogenic/likely pathogenic ALPL variant and the elevation of natural substrates were considered major criteria, a diagnosis cannot be made on these two criteria alone as it may allow for the inappropriate diagnosis of patients who are asymptomatic patients with heterozygous variants (i.e. carriers) with only biochemical findings. In such an instance, an additional major or minor criterion is required to make a diagnosis of childhood HPP.

The International Working Group convened to refine the major and minor criteria initially identified based on pooled prevalence. All of the major and minor criteria were discussed as a group and consensus was gathered on which major and minor criteria were appropriate, which should be promoted or demoted, and which should be eliminated altogether with the expectation that the resulting guidelines would be useful to diagnosis childhood HPP by clinicians in the field.

In addition to the major and minor criteria that were defined by the expert panel, it was also suggested that an obligate criterion be used — that the ALP activity should be below the lower limit of the normal range for age and sex with appropriate reference ranges being used. It was also strongly suggested that low ALP activity should be demonstrated in two or more measurements separated by time. The expert panel also strongly recommended that the differential diagnosis of low ALP be thoroughly explored to consider alternate diagnoses. Similarly, it was observed that even in patients with documented HPP, ALP can transiently normalize during pregnancy or a recent long bone fracture and so the expert panel cautions clinicians to interpret these studies in the context of patient presentation. One expert suggested that ALP activity should not be considered an obligate criterion, but a major criterion like any other. This suggestion was strongly considered, but unfortunately was not workable to create unambiguous criteria and it remained an obligate criterion.

For major findings, the expert panel decided that pathogenic or likely pathogenic ALPL variant, elevation of natural substrates, and early, premature loss of primary teeth were appropriate to keep as major criteria. Specifically, it was acknowledged that although not every child with a diagnosis of HPP will have early (meaning before age 5) nontraumatic loss of primary teeth, it remains a very common finding. It also remains true that this loss of primary teeth in HPP often occurs without resorption of the root, resulting in the appearance of the exfoliated tooth that is characteristic of HPP. Although the presence of rickets on radiograph was not included the initial criterion for inclusion as a major criterion due to having a pooled prevalence of 31% (95% CI 23–41%), the working group felt that the presence of rickets in a child who is being evaluated for HPP would be extremely helpful, particularly in the context of low ALP activity as this would not be expected in an alternate form of rickets such as nutritional rickets or hereditary forms of hypophosphatemia in which elevation of ALP activity is common. There was robust discussion about the wisdom of including the presence of osteomalacia and low bone mineral density for age into this criterion. It was decided against this inclusion given that although HPP is primarily an osteomalacia/rickets condition, histomorphometry is rarely used and even more rarely is histomorphometry used as a major component of diagnosis. Additionally, the inclusion of low BMD for age as a criterion would offer tacit support for the use of DXA in the diagnosis of HPP, a tool which has already been shown to have limited utility in patients with HPP [24]. It was therefore decided to exclude osteomalacia and low bone mineral density/osteoporosis entirely from these guidelines.

Several minor criteria are also included in these diagnostic guidelines with variable levels of agreement. Minor criteria that gained broad agreement were generally more specific to HPP such as craniosynostosis, nephrocalcinosis, and B6-responsive seizures or were less specific but more commonly seen such as short stature, delayed motor milestones, or impaired mobility. There was less broad agreement for using chronic musculoskeletal pain and low muscle tone as these were both judged to be nonspecific, but ultimately they were still included as minor criteria.

Family history of an affected first-degree relative had a pooled prevalence of 35% (95% CI 29–42%) and was included initially as a minor criterion. Although the group acknowledged the importance of obtaining a three-generation pedigree and considering family history in the evaluation process, it was still felt that the inclusion of family history as a minor criterion would cause the same problems of “biochemical/molecular only” diagnosis in patients who have no meaningful clinical manifestations of HPP. It should be noted that many patients with HPP exhibit autosomal dominant inheritance patterns, but it is also understood that dominant HPP exhibits incomplete penetrance and significant clinical variability, which may reduce the diagnostic value of an affected first-degree relative [25]. The final results of the HPP International Working Group are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Final outcomes after the meeting of the HPP International Working Group

| Obligate diagnostic criterion for HPP in children | |

| Low ALP enzymatic activity for age and sex | |

| Major diagnostic criteria for HPP in children | |

| ALPL gene variant(s) | |

| Elevation of natural substrates of TNSALP | |

| Early non traumatic loss of primary teeth | |

| Presence of rickets on radiograph | |

| Minor diagnostic criteria for HPP in children | |

| Short stature | |

| Delayed motor milestones | |

| Chronic musculoskeletal pain | |

| Impaired mobility | |

| Genu valgum/varum | |

| Craniosynostosis | |

| Nephrocalcinosis/nephrolithiasis | |

| Low muscle tone | |

| B6-responsive seizures |

Diagnosis of HPP requires either two major criteria or one major and two minor criteria. Use of low ALP activity as an obligate criterion requires exclusion of other conditions that can cause low ALP activity and multiple instances of low ALP activity

Strengths and limitations of the study

This review focused on current practice’s view on the diagnosis of pediatric HPP and the prevalence of the features and manifestations among pediatric HPP patients, the findings were based on comprehensive literature searching and meta-analysis. Another strength was the subgroup analysis and prior direction hypothesis which provided more accurate interpretation to the results.

The review also has limitations. First, the use of case report data has inherent limitations, including the fact that clinical data are not routinely collected at regular follow-up visits as they would be in a prospective study, and selecting reporting outcomes, which could lead to underestimating the prevalence. Second, a prior study has suggested that the presentation of some clinical manifestations were associated with age, which means that some manifestations could occur later in an individual’s childhood [26]. This study did not include this in the analysis and therefore may underestimate the prevalence. Additionally, this study provided a view on prevalence of diagnostic manifestations and laboratory parameters to pediatric HPP reported in existing literature but did not provide a specific diagnostic strategy.

Discussion

Diagnosis of HPP in children presents a challenge in many cases, given that there is no gold standard for diagnosis. The findings of this study show several key manifestations and laboratory parameters that were strongly recommended by the existing literature, although none were universal and thus the expertise of the working group was key to create draft guidelines that would have excellent ability to confirm or exclude a diagnosis of HPP and to be useful for all clinicians, not just those clinicians who are already familiar with the diagnosis of HPP. The organization of these guidelines into major and minor criteria prioritizes certain signs or symptoms that were judged by the working group to be either more or less important or specific to establish a diagnosis of HPP.

In the construction of the diagnostic criteria for HPP, the working group preferred to identify the features of HPP which are more specific for HPP as a major criterion. Minor criteria were those which were less commonly seen and were also more specific to HPP. The working group also emphasized the importance of integrating the clinical features with the radiographic and laboratory profile as well as the molecular diagnosis. The group decided that a diagnosis of HPP required two major criteria or one major criteria from the lists provided, but with caveats that will be further discussed.

The current nosology of HPP is based on the age of the patient’s initial presentation with HPP-related signs or symptoms [27]. This has sometimes been assumed to be the same as the age when a patient is diagnosed. This is not necessarily true as, for example, an adult patient may be diagnosed with HPP partly based on key signs and symptoms presence since childhood [28]. Using current nosology, that patient would be appropriately diagnosed with childhood HPP [2]. Having said that, the working group felt that while these distinctions exist as a function of the current nosology, as a practical matter, adults with childhood-onset disease and adults with adult-onset disease may present very similarly [29]. As a result, the working group decided that patients should be evaluated using these criteria or the simultaneously created adult criteria based on their current age, not the age at which they were believed to have started manifesting signs or symptoms of HPP.

The HPP International Working Group also acknowledged that the diagnosis of HPP cannot be completely separated from its treatment, especially given the ability to treat with enzyme replacement therapy. However, it should be noted that the question of how best to manage a patient with HPP remains a different one and it should not be assumed that all patients who meet the criteria for diagnosis will necessarily be candidates for certain treatments such as enzyme replacement therapy. The working group acknowledges that the decision for treatment is a complex one that is outside the scope of these guidelines.

Comparison with prior studies

One prior review addressed frequency and timing of clinical HPP manifestations and events, which included 224 children and 41 adult patients with HPP with ≥1 year of follow-up [26], the prior review extracted the individual patients level data from case reports and small case series and addressed the association of presentation of manifestations related to HPP and the age, which was found over an individual’s lifetime, along with the evolution and progression of the disease, the probability of presentation of manifestations could accumulate. They also calculated the prevalence of manifestations and reported similar results with our study, such as the prevalence of premature loss of teeth reported on 54% in their study and 57% in our review.

There are several differences between the prior study and this review; first, the prior review reported the frequency on the basis of individual patient’s level data, which only focused on case reports and small case series, on the contrary, our review reported the frequency by using meta-analysis method and on the basis of larger case series studies (at least 10 patients); second, the initial manifestations list in the prior review included both children and adults population, while the manifestations list in this review only focused on children; additionally, the prior review did not address how frequently the low laboratory testing results in HPP patients, while our review did.

In conclusion, this review and consensus statement identifies new major and minor criteria for the diagnosis of HPP. Integration of the clinical features, laboratory findings, radiographic features as well as the results of the DNA analysis of the TNSALP gene are helpful in confirming a diagnosis of HPP in children. Further prospective evaluation of these features will be of value in refining the diagnostic algorithm for HPP.

Funding

We acknowledge the unrestricted financial support from Alexion via the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF). They had no input into the planning or design of the project, the conduct of the reviews, evaluation of the data, writing or review of the manuscript, its content, conclusions, or recommendations contained herein.

Data availability

The data that support the findings in this study are openly available in PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane databases.

Declarations

Ethics approval

These papers are retrospective reviews and did not require ethics committee approval.

Conflict of Interest

ETR has consulted for, received honoraria from, and has research supported by Alexion Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca Rare Disease

MLB has received honoraria from Amgen, Bruno Farmaceutici, Calcilytix, Kyowa Kirin, UCB, grants and/or speaker for Abiogen, Alexion, Amgen, Bruno Farmaceutici, Echolight, Eli Lilly, Kyowa Kirin, SPA, Theramex, UCB, Consultant for Aboca, Alexion, Amolyt, Bruno Farmaceutici, Calcilytix, Kyowa Kirin, UCB

AAK has received research grants from Alexion, Amgen, Ascendis, Chugai, Radius, Takeda, Ultragenyx and is on the advisory board for Amgen, Amolyt and Takeda

SB has received advisory board participation from Alexion

KMD has received research grants and honoraria from Alexion

CD serves as an investigator, consultant, and speaker for Amgen; investigator for Radius; speaker for Alexion

SWI has received grant funding, ad hoc advisory board participation from Alexion Pharmaceuticals

MKJ has received honoria and grants from UCB, Amgen, Kyowa Kirin, Sanofi, Besin Healthcare, Abbvie

RK is a speaker and has received research funding from Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease

AL is a consultant for and has received research funding and honoraria from Alexion

MEN serves as a non-paid consultant (fee equivalent donated to 501(c)3 patient advocacy groups) for Alexion

CR has received research grants and honoraria from Alexion, Kyowa Kirin, and Regeneron

CRG is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of the HPP Global Patient Registry sponsored by Alexion Astra-Zeneca Rare Disease. She has had received honoraria for participation on this Board and has also received honoraria for select Alexion-sponsored presentations.

LS has received honoraria and grants from Alexion, Amgen, Chiesi, KyowaKirin, Novartis, Theramex, UCB

JHS serves as an Investigator and consultant for Alexion

SRS has received honoraria from, and has research supported by Alexion Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca Rare Disease

LMW serves as a consultant to Alexion

EML serves as an investigator, consultant, and speaker for Amgen; investigator for Radius; speaker for Alexion

DSA, HA, KA, FA, KD, SLF, FG, GG, EH, SK, IM, FM, LY, RBP declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mornet E (2017) Genetics of hypophosphatasia. Arch Pediat 24(5S2):5S51–5S56. 10.1016/S0929-693X(18)30014-9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Khan AA, Josse R, Kannu P, et al. Hypophosphatasia: Canadian update on diagnosis and management. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30(9):1713–1722. doi: 10.1007/s00198-019-04921-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hofmann C, Girschick HJ, Mentrup B, et al. Clinical aspects of hypophosphatasia: an update. Clin Rev Bone Min Metabol. 2013;11(2):60–70. doi: 10.1007/s12018-013-9139-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rockman-Greenberg C. Hypophosphatasia. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2013;10(Suppl 2):380–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whyte MP. Hypophosphatasia-aetiology, nosology, pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12(4):233–246. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whyte MP, Zhang F, Wenkert D, et al. Hypophosphatasia: validation and expansion of the clinical nosology for children from 25 years experience with 173 pediatric patients. Bone. 2015;75:229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Offiah AC, Vockley J, Munns CF, Murotsuki J. Differential diagnosis of perinatal hypophosphatasia: radiologic perspectives. Pediatr Radiol. 2019;49(1):3–22. doi: 10.1007/s00247-018-4239-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colazo JM, Hu JR, Dahir KM, Simmons JH. Neurological symptoms in hypophosphatasia. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30(2):469–480. doi: 10.1007/s00198-018-4691-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whyte MP, Leung E, Wilcox WR, Liese J, Argente J, Martos-Moreno GÁ, Reeves A, Fujita KP, Moseley S, Hofmann C. Study 011-10 investigators. Natural history of perinatal and infantile hypophosphatasia: a retrospective study. J Pediatr. 2019;209:116–124.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bangura A, Wright L, Shuler T. Hypophosphatasia: current literature for pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. Cureus. 2020;12(6):e8594. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fenn JS, Lorde N, Ward JM, Borovickova I. Hypophosphatasia. J. Clin. Pathol. 2021;74(10):635–640. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2021-207426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pierpont EI, Simmons JH, Spurlock KJ, Shanley R, Sarafoglou KM. Impact of pediatric hypophosphatasia on behavioral health and quality of life. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16(1):80. doi: 10.1186/s13023-021-01722-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Del Angel G, Reynders J, Negron C, Steinbrecher T, Mornet E. Large-scale in vitro functional testing and novel variant scoring via protein modeling provide insights into alkaline phosphatase activity in hypophosphatasia. Hum Mutat. 2020;41(7):1250–1262. doi: 10.1002/humu.24010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whyte MP, Zhang F, Wenkert D, McAlister WH, Mack KE, Benigno MC, Coburn SP, Wagy S, Griffin DM, Ericson KL, Mumm S. Hypophosphatasia: validation and expansion of the clinical nosology for children from 25 years experience with 173 pediatric patients. Bone. 2015;75:229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tenorio J, Álvarez I, Riancho-Zarrabeitia L, Martos-Moreno GÁ, Mandrile G, de la Flor CM, Sukchev M, Sherif M, Kramer I, Darnaude-Ortiz MT, Arias P, Gordo G, Dapía I, Martinez-Villanueva J, Gómez R, Iturzaeta JM, Otaify G, García-Unzueta M, Rubinacci A, Riancho JA, Aglan M, Temtamy S, Hamid MA, Argente J, Ruiz-Pérez VL, Heath KE, Lapunzina P. Molecular and clinical analysis of ALPL in a cohort of patients with suspicion of Hypophosphatasia. Am J Med Genet A. 2017;173(3):601–610. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whyte MP, Zhang F, Wenkert D, Mack KE, Bijanki VN, Ericson KL, Coburn SP. Hypophosphatasia: Vitamin B6 status of affected children and adults. Bone. 2021;20(154):116204. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2021.116204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whyte MP, Coburn SP, Ryan LM, Ericson KL, Zhang F. Hypophosphatasia: biochemical hallmarks validate the expanded pediatric clinical nosology. Bone. 2018;110:96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2018.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villa-Suárez JM, García-Fontana C, Andújar-Vera F, González-Salvatierra S, de Haro-Muñoz T, Contreras-Bolívar V, García-Fontana B, Muñoz-Torres M. Hypophosphatasia: a unique disorder of bone mineralization. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(9):4303. doi: 10.3390/ijms22094303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whyte MP, Madson KL, Phillips D, Reeves AL, McAlister WH, Yakimoski A, Mack KE, Hamilton K, Kagan K, Fujita KP, Thompson DD, Moseley S, Odrljin T, Rockman-Greenberg C. Asfotase alfa therapy for children with hypophosphatasia. JCI Insight. 2016;1(9):e85971. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.85971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bishop N, Munns CF, Ozono K. Transformative therapy in hypophosphatasia. Arch. Dis. Child. 2016;101(6):514–515. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karbasy K, Lin DC, Stoianov A, Chan MK, Bevilacqua V, Chen Y, Adeli K. Pediatric reference value distributions and covariate-stratified reference intervals for 29 endocrine and special chemistry biomarkers on the Beckman Coulter Immunoassay Systems: a CALIPER study of healthy community children. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2016;54(4):643–657. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2015-0558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Placeholder for diagnosis/methods paper

- 23.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simmons JH, Rush ET, Petryk A, Zhou S, Martos-Moreno GÁ. Dual X-ray absorptiometry has limited utility in detecting bone pathology in children with hypophosphatasia: a pooled post hoc analysis of asfotase alfa clinical trial data. Bone. 2020;137:115413. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2020.115413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mornet E, Taillandier A, Domingues C, Dufour A, Benaloun E, Lavaud N, Wallon F, Rousseau N, Charle C, Guberto M, Muti C, Simon-Bouy B. Hypophosphatasia: a genetic-based nosology and new insights in genotype-phenotype correlation. Eur J Hum Genet. 2021;29(2):289–299. doi: 10.1038/s41431-020-00732-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szabo SM, Tomazos IC, Petryk A, et al. Frequency and age at occurrence of clinical manifestations of disease in patients with hypophosphatasia: a systematic literature review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14(1):85. doi: 10.1186/s13023-019-1062-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wenkert D, McAlister WH, Coburn SP, Zerega JA, Ryan LM, Ericson KL, Hersh JH, Mumm S, Whyte MP. Hypophosphatasia: nonlethal disease despite skeletal presentation in utero (17 new cases and literature review) J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:2389–2398. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bangura A, Wright L, Shuler T. Hypophosphatasia: current literature for pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. Cureus. 2020;12(6):e8594. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Genest F, Claußen L, Rak D, Seefried L. Bone mineral density and fracture risk in adult patients with hypophosphatasia. Osteoporos Int. 2021;32(2):377–385. doi: 10.1007/s00198-020-05612-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings in this study are openly available in PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane databases.