Abstract

Spermatogenesis is a continual process that occurs in the testes, in which diploid spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs) differentiate and generate haploid spermatozoa. This highly efficient and intricate process is orchestrated at multiple levels. N6-methyladenosine (m6A), an epigenetic modification prevalent in mRNAs, is implicated in the transcriptional regulation during spermatogenesis. However, the dynamics of m6A modification in non-rodent mammalian species remains unclear. Here, we systematically investigated the profile and role of m6A during spermatogenesis in pigs. By analyzing the transcriptomic distribution of m6A in spermatogonia, spermatocytes, and round spermatids, we identified a globally conserved m6A pattern between porcine and murine genes with spermatogenic function. We found that m6A was enriched in a group of genes that specifically encode the metabolic enzymes and regulators. In addition, transcriptomes in porcine male germ cells could be subjected to the m6A modification. Our data show that m6A plays the regulatory roles during spermatogenesis in pigs, which is similar to that in mice. Illustrations of this point are three genes (SETDB1, FOXO1, and FOXO3) that are crucial to the determination of the fate of SSCs. To the best of our knowledge, this study for the first time uncovers the expression profile and role of m6A during spermatogenesis in large animals and provides insights into the intricate transcriptional regulation underlying the lifelong male fertility in non-rodent mammalian species.

Keywords: N6-methyladenosine, Spermatogonial stem cell, Spermatogenesis, SETDB1, Pig

Introduction

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is a ubiquitous epigenetic marker in mammalian mRNAs [1]. As the first reversible RNA modification, m6A is installed by methyltransferase (METTL3, METTL14, and WTAP) [2], and reversed by demethylases FTO and ALKBH5 [3], [4]. m6A is recognized by YTHDF1, YTHDF2, eIF3, and others [5], [6]. Of these m6A-reader proteins, YTHDF2 recognizes m6A in mRNAs and targets the transcripts triggering the rapid degradation of m6A-containing mRNAs, whereas YTHDF1 and eIF3 bind to m6A-containing transcripts and promote the translation [2]. The critical roles of m6A involved in numerous biological processes, such as maternal mRNA clearance, DNA repair, embryonic development, sex determination, and spermatogenesis [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], have been revealed in recent studies using knockout mouse models.

The testis offers lifelong male fertility by producing billions of sperm daily [13]. Sperm are derived from spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs), which undergo self-renewal divisions to maintain the stem cell pool or differentiation to generate progenitors and spermatogonia (SPG). The differentiated SPG further develop into preleptotene spermatocytes, which undergo a last round of DNA replication before entering meiosis. Through meiosis, haploid round spermatids (RS) are generated with dramatic changes in morphology and physiology [14], [15]. This highly organized process, named spermatogenesis, requires timely coordinated gene expression at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels [16]. Spermatogenesis also involves unique characteristics, such as premade transcripts, high levels of alternative splicing, and decreased or ceased transcriptional activity at onset of meiotic prophase I and late spermiogenesis [17]. Note that m6A modification that mediates mRNA splicing, stability, and translation [18], [19], [20] is involved in spermatogenesis, as demonstrated by loss-of-function studies for m6A writers [11], [21], erasers [4], [22], and readers [23] in mice.

Pigs (Sus scrofa), which are responsible for more than one third of meat produced worldwide, are important to global living demands and food security [24]. In addition, pigs are an excellent large animal model in biomedical research, owing to their similarities to humans in anatomy, physiology, and genetics. Although the mechanisms for spermatogenesis have been investigated extensively in mice, they remain poorly understood in pigs, and the roles of m6A in porcine spermatogenesis remain largely elusive. Here, we isolated porcine SPG, pachytene spermatocytes (PS), and RS, and performed the m6A affinity purification followed by m6A sequencing (m6A-seq) and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). By analyzing the abundance of m6A and its roles in porcine spermatogenesis, we highlight for the first time the magnitude of m6A in transcriptional regulation in porcine spermatogenesis, thereby laying the foundation for future endeavors to link m6A to research and therapy for male infertility.

Results

Enrichment and characterization of porcine male germ cells

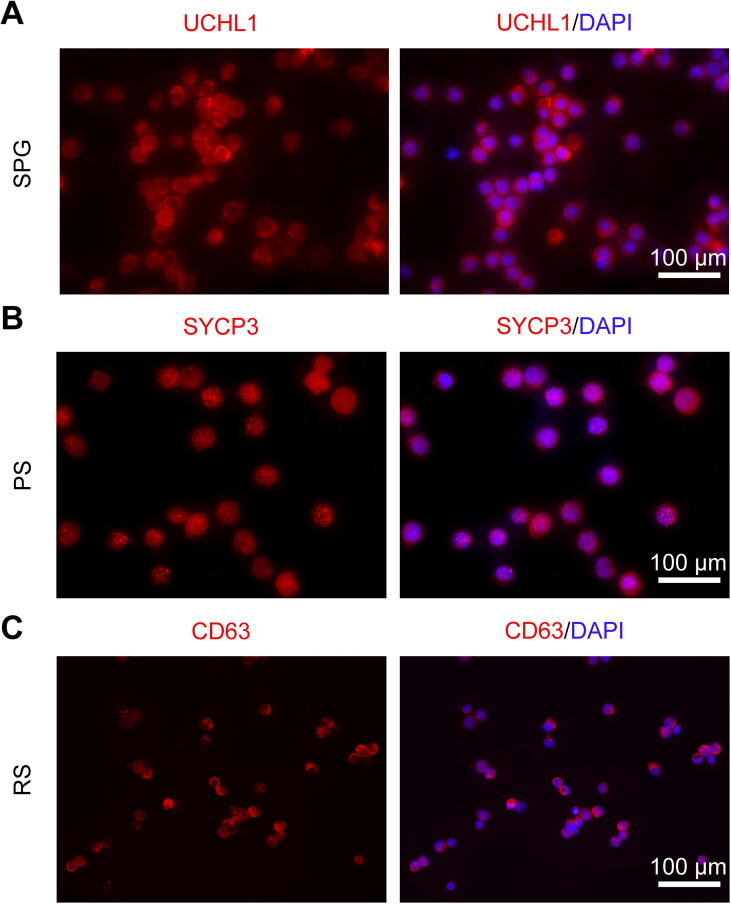

To obtain the transcriptome-wide map of m6A during spermatogenesis, we first isolated SPG, PS, and RS from porcine testes using STA-PUT velocity sedimentation. The purity of the isolated SPG, PS, and RS was determined by several biomarkers. Immunocytochemical analysis showed that the isolated SPG, PS, and RS were positive for ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal esterase L1 (UCHL1), synaptonemal complex protein 3 (SYCP3), CD63 Molecule (CD63), respectively (Figure 1A–C). In addition, the nuclei of the isolated SPG, PS, and RS were around 7–8 µm, 12–13 µm, and 5 µm in diameter, respectively (Figure 1A–C). These results suggest that the freshly isolated germ cells were SPG, PS, and RS with biochemical and nuclear characteristics.

Figure 1.

Identification of porcine male germ cells

A. Immunocytochemistry showing the expression of UCHL1 in the SPG. B. Immunocytochemistry showing the expression of SYCP3 in the freshly isolated PS. C. Immunocytochemistry showing the expression of CD63 in the RS. SPG, spermatogonium; PS, pachytene spermatocyte; RS, round spermatid; UCHL1, ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal esterase L1; SYCP3, synaptonemal complex protein 3; CD63, CD63 Molecule; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Scale bar, 100 µm.

m6A-seq analysis of porcine male germ cells

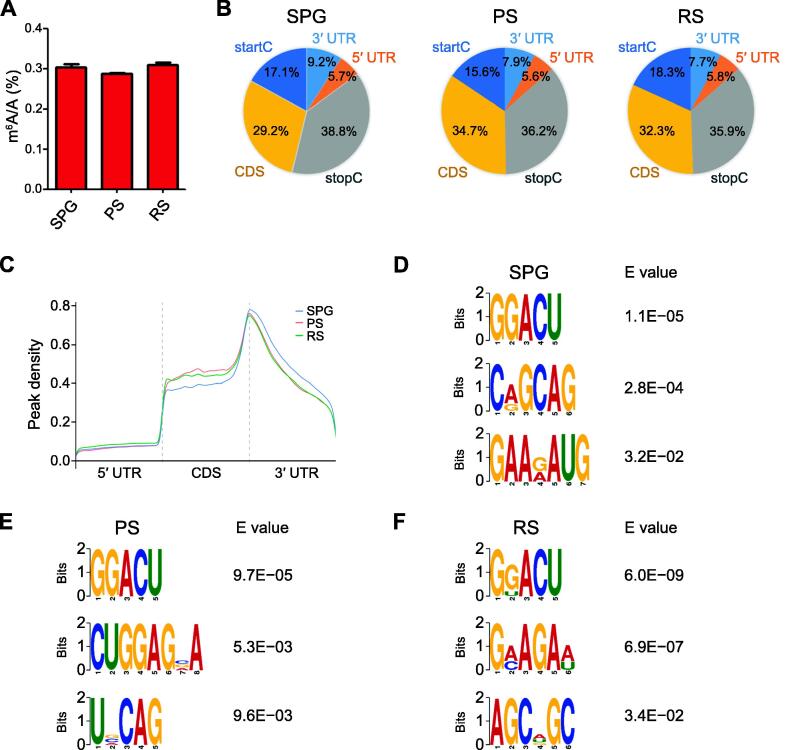

To elucidate the m6A methylome in different stages of spermatogenesis, the liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) was performed to quantify the changes of m6A modification in the isolated germ cells (Figure 2A). The m6A was presented in all mRNAs of the tested male germ cells, and the level of m6A remained relatively stable (∼ 0.3%) during the developmental stages. To further uncover the dynamics of m6A, the m6A-seq was performed and the locations of m6A peaks along the transcripts were determined. We found that m6A peaks were highly enriched near the start codon (startC), coding sequence (CDS), and stop codon (stopC) in the germ cells, but there were some differences among the three stages of germ cells (Figure 2B). The m6A peaks near the startC were 17.1% in SPG, 15.6% in PS, and 18.3% in RS (Figure 2B). m6A peaks near the CDS increased 5.5% from SPG to PS, followed by a 2.4% drop from PS to RS (Figure 2B). Furthermore, the abundance of m6A peaks near the stopC decreased 2.6% in PS (36.2%; Figure 2B) and then stabilized in RS (35.9%; Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Distribution pattern of m6A peaks along transcripts

A. LC-MS/MS analysis of m6A percentage relative to adenosine in SPG, PS, and RS. B. m6A peak distribution within different gene contexts: startC, CDS, stopC, 3′ UTR, and 5′ UTR. C. Accumulation of m6A-IP reads along transcripts in SPG, PS, and RS. Each transcript is divided into three parts: 5′ UTR, CDS, and 3′ UTR. D.–F. The top 3 used motifs among m6A peaks in SPG (D), PS (E), and RS (F). LC-MS/MS, liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry; startC, start codon; CDS, coding sequence; stopC, stop codon; UTR, untranslated region.

The distribution of m6A in the whole transcriptome was validated by the m6A reads along transcripts. Consistent with the distribution of m6A peaks, m6A reads were distributed throughout the mRNA transcripts, in which the reads increased in the CDS and reached the peak at the 3′ UTR (Figure 2C). Specifically, in the CDS, the density of m6A reads in PS was higher than that in RS, followed by in SPG (Figure 2C). In addition, the density of m6A reads in the 3′ UTR of SPG was higher than that in PS and RS (Figure 2C). Together, the results reveal that m6A is dynamic in porcine male germ cells, which suggests its critical roles during spermatogenesis.

To determine whether the RRACH is the m6A consensus sequence in porcine germ cells, we analyzed the 1000 most significant peaks. The GGACU was a top motif in all tested samples (Figure 2D–F), suggesting that the RRACH motif adopted in porcine spermatogenesis is conserved in pigs and mice [11]. It is important to note that as a top motif in SPG (Figure 2D), PS (Figure 2E), and RS (Figure 2F), the GGACU is an m6A-modified sequence prevalent in porcine male germ cells.

m6A-enriched genes are involved in important biological processes

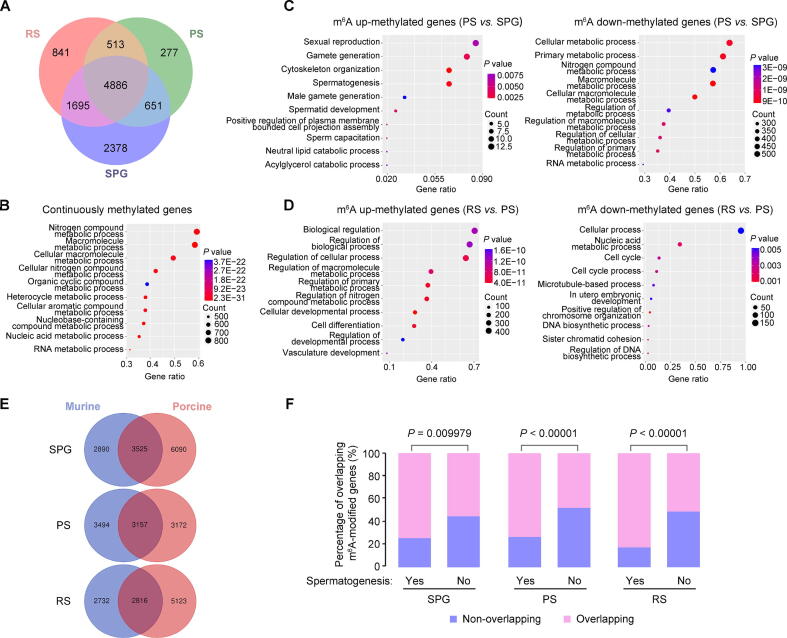

We discovered 11,241 methylated genes in porcine male germ cells. Of these, 2378, 277, and 841 methylated genes were exclusively expressed in SPG, PS, and RS, respectively (Figure 3A). Gene Ontology (GO) biological process analysis revealed that the 4886 continuously methylated genes were mostly involved in metabolic processes (Figure 3B). We then analyzed the genes containing altered m6A peaks (fold change ≥ 2, P ≤ 10E−5) to uncover more insights into m6A in porcine spermatogenesis. Results showed that 692 and 3662 genes were up- and down-methylated in PS, respectively, when compared to SPG; 3058 and 884 genes were up- and down-methylated in RS, respectively, when compared to PS (Table S1). GO biological process analysis revealed that up-methylated genes in PS (vs. SPG) were involved in spermatogenesis, whereas down-methylated genes were mostly involved in metabolic processes (Figure 3C). In addition, the up-methylated genes in RS (vs. PS) participated in developmental and metabolic processes, and down-methylated genes were mostly involved in the regulation of chromosome organization, nucleic acid metabolic, and microtubule-based process (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

m6A modification pattern during porcine spermatogenesis

A. Venn diagram showing the pattern of m6A-modified genes in SPG, PS, and RS. B. The enriched biological processes of continuously methylated genes during spermatogenesis by GO analysis. C. The enriched biological processes of DMGs between PS and SPG by GO analysis. D. The enriched biological processes of DMGs between RS and PS by GO analysis. Each dot plot shows gene ratio values of the top 10 significant enrichment terms. E. Venn diagram showing the overlapping m6A-modified genes between murine and porcine in SPG, PS, and RS. F. Different proportions of the overlapping methylated genes related or unrelated to spermatogenesis in murine and porcine in SPG, PS, and RS. The P value of such difference was calculated with the Chi-square test. GO, Gene Ontology; DMG, differentially methylated gene.

Next, we compared the m6A-modified genes between porcine and mouse germ cells [11]. A total of 6090, 3172, and 5123 m6A-modified genes were uniquely found in porcine SPG, PS, and RS, respectively, whereas 3525, 3157, and 2816 m6A-modified genes were shared by both murine and porcine SPG, PS, and RS, respectively (Figure 3E). Notably, these overlapping m6A-methylated transcripts were preferentially enriched and reported to be essential for mouse spermatogenesis [11] (Figure 3F), indicating that m6A mediates conserved processes in male germ cells.

Gene expression during spermatogenesis

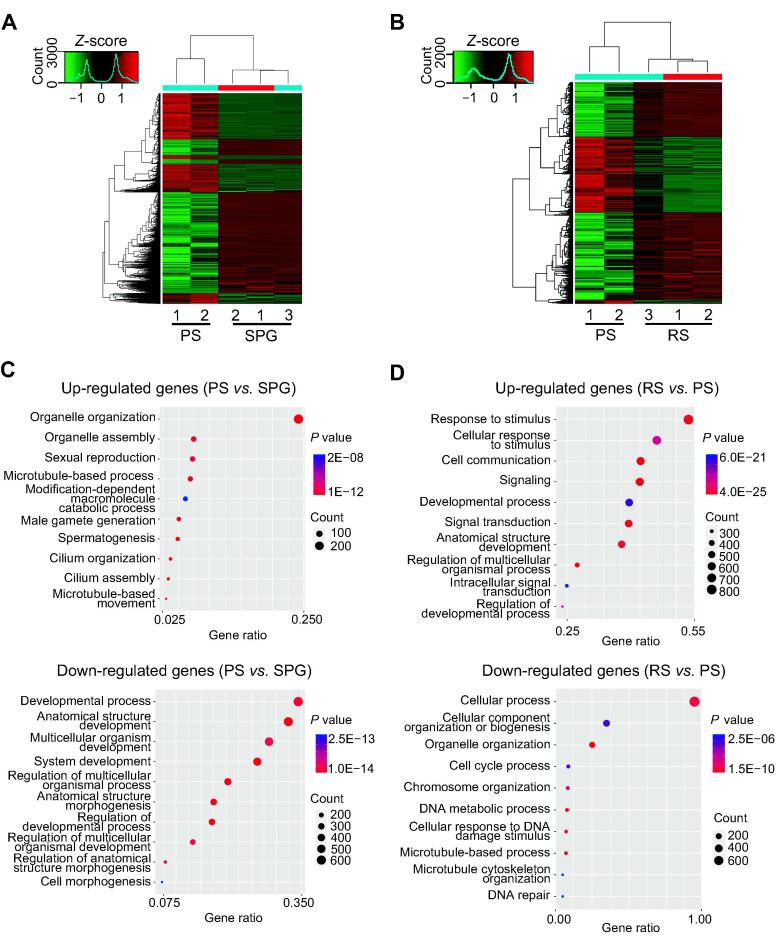

To further probe the regulatory roles of m6A, we performed RNA-seq analysis on these germ cells. We analyzed differentially expressed genes (DEGs; fold change ≥ 2, P < 0.05, FPKM ≥ 0.1) between continually developing germ cells. Results showed that 4393 and 5949 genes were up- and down-regulated in PS, respectively, when compared to SPG (Figure 4A; Table S2); 5119 and 2872 genes were up- and down-regulated in RS, respectively, when compared to PS (Figure 4B; Table S2). GO biological process annotation analysis revealed that in PS, the up-regulated genes (vs. SPG) mainly participated in cilium organization and spermatogenesis, while the down-regulated genes were involved in anatomical structure morphogenesis and regulation of developmental processes (Figure 4C). In RS (vs. PS), the up-regulated genes mainly regulated cell communication and developmental processes, whereas the down-regulated genes regulated chromosome organization and DNA metabolic process (Figure 4D). Given these findings on m6A-mediated processes (Figure 3C and D), we propose that the m6A modification might influence gene expression, thereby regulating spermatogenesis.

Figure 4.

Gene expression pattern during porcine spermatogenesis

A. The heatamap of DEGs between PS and SPG. B. The heatamap of DEGs between RS and PS. C. The enriched biological processes of DEGs between PS and SPG by GO analysis. D. The enriched biological processes of DEGs between RS and PS by GO analysis. Each dot plot shows gene ratio values of the top 10 significant enrichment terms. DEG, differentially expressed gene.

m6A modification is involved in gene expression regulation

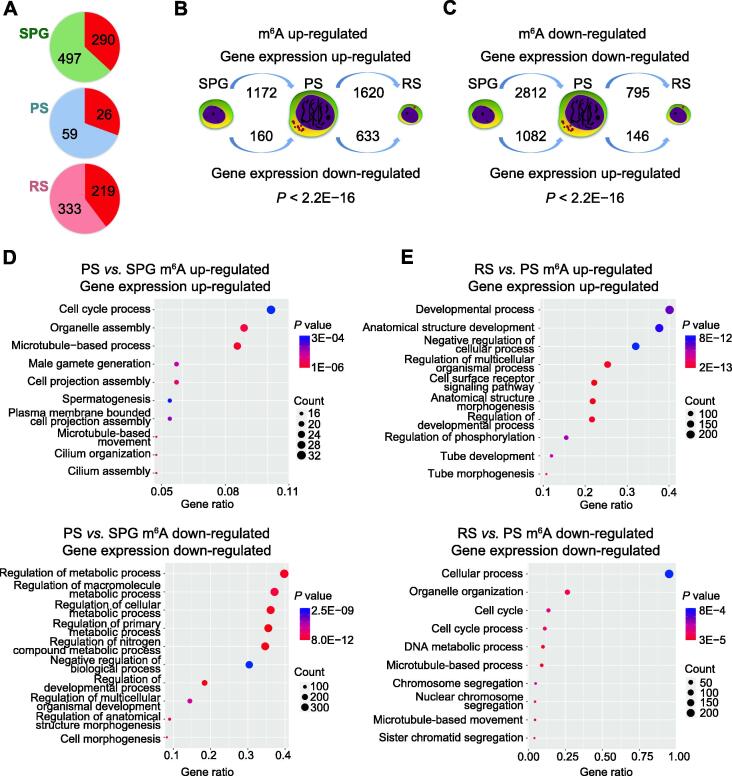

We found that 36.8%, 30.6%, and 39.7% of the stage-specific transcripts, i.e., for SPG, PS, and RS, respectively, were m6A modified (Figure 5A). To explore whether the m6A modification influences gene expression, we conducted a paired analysis of differentially methylated genes (DMGs) and DEGs between each two adjacent stages.

Figure 5.

m6A-regulatedgene expression during porcine spermatogenesis

A. The m6A modification distribution within stage-specific gene contexts. Number in the red part represents the number of genes specifically methylated in SPG, PS, or RS. B. and C. The number of up- or down-regulated genes during porcine spermatogenesis stratified by up-methylated (B) or down-methylated (C) genes. The P value of such difference was calculated with the Chi-square test. D. The enriched biological processes of m6A positively regulated genes between PS and SPG by GO analysis. E. The enriched biological processes of m6A positively regulated genes between RS and PS by GO analysis. Each dot plot shows gene ratio values of the top 10 significant enrichment terms.

Among m6A up-methylated genes, 1172 and 1620 genes showed up-regulated expression during the transition from SPG to PS and from PS to RS, respectively (Figure 5B), while 160 and 633 genes showed down-regulated expression during the transition from SPG to PS and from PS to RS, respectively (Figure 5B). Among the m6A down-methylated genes, the expression levels of 2812 and 795 genes were decreased during the transition from SPG to PS and from PS to RS, respectively (Figure 5C), whereas those of 1082 and 146 genes were increased during the transition from SPG to PS and from PS to RS, respectively (Figure 5C). Hence, m6A exhibits positive correlation with gene expression.

To further uncover the biological significance of the dynamically modified m6A genes, we performed the GO biological process analysis with positive correlations with m6A modification. Compared to SPG, the up-regulated genes in PS mainly participated in the regulation of spermatogenesis and microtubule-based process (Figure 5D), and the down-regulated genes in PS were involved in the regulation of metabolic processes and developmental process (Figure 5E). Compared to PS, the up-regulated genes in RS regulated the developmental process and tube morphogenesis, and the down-regulated genes in RS participated in the sister chromatid segregation, DNA metabolic process, and microtubule-based process. Together, these findings reveal that m6A regulates gene expression and spermatogenesis.

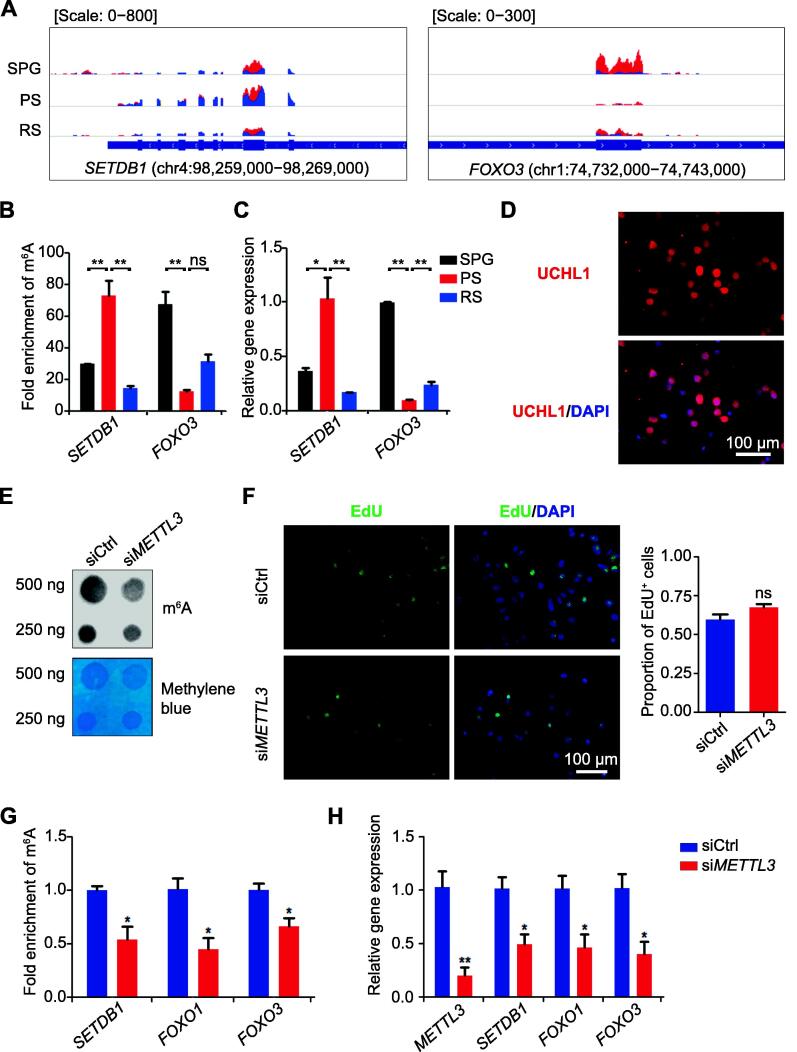

m6A-regulated gene expression is associated with the fate of SSCs

Previous studies have shown that the methyltransferase SET domain bifurcated histone lysine methyltransferase 1 (SETDB1) catalyzes tri-methylation of histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9me3) and plays important roles for SSC survival [25], [26], [27]. Meanwhile, deficiencies in FOXO1, FOXO3, and FOXO4 impair the self-renewal and differentiation of SSCs [28]. To determine whether m6A regulates the expression of these genes, we analyzed m6A modification patterns on SETDB1 and FOXO3 transcripts by m6A-RIP-qPCR. We found that both SETDB1 and FOXO3 transcripts contained at least one m6A peak (Figure 6A). SETDB1 was up-methylated from SPG to PS and down-methylated from PS to RS, whereas FOXO3 was down-methylated from SPG to PS and then up-methylated from PS to RS (Figure 6B). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis revealed that the mRNA levels of SETDB1 and FOXO3 were strongly positively correlated with m6A modifications (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Knockdown of METTL3 in porcineSSCs induced the abnormal gene expression

A. Distribution of m6A on SETDB1 and FOXO3 during porcine spermatogenesis. Blue and red bars indicate the input and IP read coverage, respectively. B. Bar chart showing the m6A levels of SETDB1 and FOXO3 in SPG, PS, and RS validated by m6A-RIP-qPCR. C. Bar chart showing the mRNA levels of SETDB1 and FOXO3 in porcine SPG, PS, and RS validated by qRT-PCR. D. Immunocytochemistry showing the expression of UCHL1 in porcine SSCs. E. m6A dot blot analysis of the METTL3 knockdown (siMETTL3). siCtrl was used as a negative control. Methylene blue staining was used to evaluate RNA amount. F. Representative images of EdU incorporation in the cells transfected with siMETTL3 or siCtrl. The quantification analysis of EdU incorporation in the cells transfected with siMETTL3 or siCtrl was shown on the right. G. Bar chart showing the m6A levels of the targeted genes in the cells transfected with siMETTL3 or siCtrl validated by m6A-RIP-qPCR. H. Bar chart showing the relative expression level of METTL3, SETDB1, FOXO1, and FOXO3 in the cells transfected with siMETTL3 or siCtrl detected by qRT-PCR. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. The P value was calculated with one-way ANOVA analysis followed by Bonferroni multiple-comparison test and unpaired t-test, *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ns, no significance. SSC, spermatogonial stem cell; IP, immunoprecipitation; EdU, 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine; SEM, standard error of mean. Scale bar, 100 µm.

To further validate the regulatory roles of m6A, we knocked down METTL3 in porcine SSCs by a small interfering RNA (siRNA) [29], [30] (Figure 6D). Knockdown of METTL3 (siMETTL3) led to a decrease in m6A level, compared to the scramble control (siCtrl) (Figure 6E). Nevertheless, EdU incorporation showed that cell proliferation was not significantly different between cells transfected with siCtrl and siMETTL3 (Figure 6F). m6A-RIP-qPCR revealed that knockdown of METTL3 significantly reduced the relative level of m6A in SETDB1, FOXO1, and FOXO3 (Figure 6G). In addition, qRT-PCR analysis showed that the expression of these three targeted genes was significantly down-regulated (Figure 6H), consistent with the dynamics in SPG and PS showed by RNA-seq data (Figure 6A and C). Thus, these data suggest that m6A regulates the dynamic gene expression during porcine spermatogenesis.

Discussion

Growing evidence has demonstrated the critical roles of m6A in murine spermatogenesis [11], [21]. The highly dynamic spermatogenesis process requires precise regulation of gene expression. Here, we reported that m6A modification was dynamically present in the transcripts of porcine male germ cells, which influenced gene expression.

In this study, m6A was distributed predominantly on the consensus motif of GGACU, which is consistent with murine male germ cells [23]. The m6A was present throughout mRNA transcripts in porcine germ cells, especially increased the read density in the CDS. The m6A reached its highest value around the stopC and then decreased in the 3′ UTR. This distribution pattern agrees with the previous findings in mouse [11]. Hence, m6A modification exhibits evolutionally conserved features in male germ cells in mouse and pig.

Note that the abundance of m6A in transcripts varied by the developmental stage during spermatogenesis. We found that m6A read density in the CDS was greater in PS and RS, whereas in the 3′ UTR it was greater in SPG. In a previous study, Lin et al. reported that m6A read density in the CDS in PS/diplotene spermatocytes and RS was higher than that in the undifferentiated SPG, type A1 SPG, and preleptotene spermatocytes [11]. The highest density of m6A reads was in the 3′ UTR close to the stopC of PS/diplotene spermatocytes, and the lowest of that was in type A1 SPG [11]. In addition, Tang et al. reported that m6A was enriched in long 3′ UTR transcripts of murine RS and elongating spermatids [22]. In general, m6A in the CDS is correlated with translational products, and m6A in the 3′ UTR is preferentially bound by factors regulating alternative splicing and polyadenylation, subcytoplasmic compartmentalization, and stability [31], [32]. Therefore, dynamically changed m6A around these landmarks could mediate specific transcript outputs in a stage-specific manner during mammalian spermatogenesis.

During spermatogenesis, SPG undergo mitosis to give rise to spermatocytes. Depletion of METTL3 or METTL14 in germ cells induced a 70% reduction of m6A in undifferentiated SPG and a 55%–65% reduction of m6A in PS [11]. METTL3 deficiency induced the abnormal initiation of spermatogonial differentiation and disrupted the ability of spermatocytes to reach the pachytene stage of meiotic prophase [21]. In this study, the down-methylated genes from SPG to PS mainly participated in metabolic processes, and most m6A down-methylated genes that were also mainly involved in metabolic and developmental processes were down-regulated. It is interesting that SPG that are localized in the basal compartment of seminiferous tubules exhibit high glycolytic activity [33]. In contrast, PS and RS, which are distributed in the luminal compartment, satisfy their ATP supply mainly through the aerobic (OXPHOS) pathway. Therefore, m6A might play critical roles in mediating mitochondrial function from SPG to PS.

A report showed that the loss of ALKBH5 markedly increased m6A levels in testes [4]. A delay in spermatocyte development occurred in the ALKBH5-knockout testes, which was due to the dysregulation of genes involved in meiotic progression [4], [22]. The up-methylated genes in PS preferentially participated in spermatogenesis and cell cycle process. These genes were also up-regulated by m6A modification, indicating an important role of m6A at early developmental stages. To generate the haploid spermatids, spermatocytes must undergo two meiotic divisions. The first meiotic division promotes the pairing and exchange of genetic materials, and the second meiotic division is more comparable to mitotic divisions as it contains the segregation of sister chromatids [34]. In addition, m6A in PS was also enriched in genes that functioned in spermatid development and up-regulated the expression of genes involving in microtubule-based process, cilium organization, and cilium assembly. It is reasonable to speculate that m6A-methylated mRNAs may repress translation before spermiogenesis.

During spermiogenesis, RS go through multistep cytological changes, such as the formation of an acrosome and a flagellum, chromatin remodeling, and the removal of the residual body [15], [35]. METTL3-knockout or METTL14-knockout result in a 45% reduction of m6A abundance in RS [11]. The seminiferous tubules contain very few spermatozoa, and sperms exhibit defects in motility, flagella, and head [11]. In the present study, m6A up-methylated genes in RS showed up-regulated expression, and these genes mainly participated in regulating developmental process, including the development of multicellular organisms, anatomical structures, and tube morphogenesis, suggesting the conserved roles of m6A in mediating porcine spermiogenesis. At the beginning of spermiogenesis, nuclear condensation begins and histones are rapidly replaced by protamines [36], [37]. The mRNAs are massively eliminated during spermiogenesis [38]. m6A in PS shows heavy enrichment in genes regulating chromosome organization and nucleic acid metabolic, which are essential for meiosis and down-regulated in RS. Because of the greater m6A retention in the longer pre-mRNA of the ALKBH-knockout testis, the splicing of these transcripts is enhanced and further causes the production of shorter transcripts. m6A modification of the short transcripts further serves as a signal to quickly degrade elongating spermatids [22]. Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) are responsible for degrading large populations of mRNAs in the late stage of spermiogenesis [38]. It is intriguing that piRNA target sites are preferentially located in the 3′ UTR of the target mRNAs [39]. Given the high-level m6A modification on the mRNA 3′ UTR, it is possible that m6A mediates the piRNA-dependent mRNA degradation pathway during spermiogenesis.

Expression of FOXOs in germ cells is intimately associated with cell fate, which are responsible for cell cycle arrest and programmed cell death [40]. Our previous studies revealed that knockdown of SETDB1 to an extremely low level could activate FOXO1 that is the most important FOXOs in spermatogenesis [25], [26], [27]. Here, we provide evidence that m6A regulates the expression of SETDB1, FOXO1, and FOXO3 during porcine spermatogenesis. Unlike the hypo-proliferation in SETDB1-knockdown SSCs or gonocytes [26], [27], METTLE3-knockdown mildly promotes proliferation, suggesting that other methyltransferases, such as SUV39H1 and SUV39H2, may partially compensate for SETDB1 deficiency [41]. Moreover, deleting METTL3 from murine SSCs induces the hyper-proliferation and impaired differentiation [11], [21]. Recent work has showed that m6A on retroviral element RNAs recruit SETDB1 to regulate heterochromatin in mouse embryonic stem cells [42], [43]. It would be worthwhile to study whether and how m6A regulates SETDB1 expression and H3K9 methylation, which further govern the fate of SSCs.

In conclusion, we present here the first m6A transcriptome-wide map of porcine spermatogenesis. Our findings provide a roadmap for uncovering m6A functions that might improve porcine fertility and treat infertility in humans.

Materials and methods

Animals

Testis samples of 5-month-old pigs were acquired from the Besun farm, Yangling, China. After the castration, testes were transported to the pre-cold PBS (4 °C) contained 2% of penicillin and streptomycin (Catalog No. SV30010, HyClone, Logan, UT) and brought to the laboratory within 2 h. Testes were cut into small pieces and subjected to two-step enzyme digestion as previously described [44]. After digestion with collagenase Type IV (0.2% w/v; Catalog No. 17104019, Gibco, Grand Island, NY) at 37 °C for 30 min, the obtained seminiferous tubules were further digested by 0.25% trypsin–EDTA (Catalog No. SV30031.01, HyClone) at 37 °C for 15 min. Then, the germ cells were collected by the differential plating.

The isolation of SPG, PS, and RS was conducted as previously described [45]. In brief, 1 × 107–1 × 108 dispersed germ cells were suspended in 50-ml DMEM plus 0.5% BSA and load onto a 600-ml gradient of 2%–4% BSA for 3 h sediment at 4 °C. Approximately 100 6-ml fractions were collected in tubes and analyzed by the morphology and immunostaining. Fractions with high purity of SPG, PS, and RS were resuspended with TRIzol (Catalog No. 15596026, Invitrogen, Vilnius, Lithuania) and stored at −80 °C until usage.

LC-MS/MS quantification of m6A levels

LC-MS/MS quantification of m6A was performed by Cloudseq Biotech Inc. (Shanghai, China) following the vendors recommended protocol. Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Catalog No. 15596026, Invitrogen) following to the manufacturer’s instruction. In brief, 1 µg of total RNA was digested by 4-µl nuclease P1 (Catalog No. N8630, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in 40-µl buffer solution (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM ZnCl2) at 37 °C for 12 h, followed by incubating with 1-µl alkaline phosphatase (Catalog No. P5931, Sigma) at 37 °C for 2 h. RNA solution was diluted to 100 µl and injected into LC-MS/MS. The nucleosides were separated by reverse phase high-performance liquid chromatography on an Agilent C18 column (Catalog No. 5188–5328, Agilent Technologies, San Diego, CA), coupled with MS detection using AB SCIEX QTRAP 5500 (Catalog No. AB Sciex QTrap 5500, AB Sciex LLC, Framingham, MA). Pure nucleosides were used to generate standard curves, from which the concentrations of adenosine (A) and m6A in the sample were calculated. The level of m6A was then calculated as a percentage of total unmodified A.

Cell culture and RNA-interference-mediated METTL3 knockdown

The porcine SSC line was cultured in the complete medium made up of DMEM (high glucose, pyruvate; Catalog No. 11995065, Gibco), 5% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS; Catalog No. 12664025, Gibco, Mesenchymal Stem Cell FBS Qualified), 5% (v/v) knockout serum replacement (KSR; Catalog No. 10828028, Gibco), 2 mM Glutamax (Catalog No. 35050061, Gibco), 1× MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids Solution (Catalog No. 11140076, Gibco), 1× MEM Vitamin Solution (Catalog No. 11120052, Gibco), 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol (Catalog No. M6250, Sigma), 1× penicillin–streptomycin (Catalog No. SV30010, HyClone), 20 ng/ml recombinant human GDNF (Catalog No. 45010, PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), 40 ng/ml recombinant human GFRA1 (Catalog No. 788104, BioLegend, San Diego, CA), and 10 ng/ml recombinant human bFGF (Catalog No. 10018B, PeproTech). The cells were maintained at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2. For METTL3 knockdown, porcine SSCs were transfected with 50 pM of siRNA duplexes against porcine METTL3 (GenePharma, Shanghai, China; the RNA oligos are listed in Table S3), using Advanced DNA RNA Transfection Reagent (Catalog No. AD600025, ZETA LIFE, Menlo Park, CA) in antibiotic-free medium. Cells were collected for analysis 72 h after transfection. The cells were lysed by TRIzol (Catalog No. 15596026, Invitrogen) and stored at −80 °C until usage.

Immunocytochemistry

The isolated SPG, PS, and RS were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 25 min at 4 °C and washed with PBS for three times. Then, the cells were permeabilized for 10 min using 0.1% Triton-X 100 followed by washing with PBS for three times. The cells were further blocked with 10% donkey serum for 2 h at room temperature, and incubated with primary antibodies, including UCHL1 (Catalog No. ab8189, Abcam, Cambridge, Britain), SYCP3 (Catalog No. ab15093, Abcam), and CD63 (Catalog No. 25682-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China) at a dilution with 1:200 overnight at 4 °C. Next day, the cells were washed with PBS for 4 times and incubated with secondary antibody (Yeasen, Shanghai, China) at a dilution with 1:400 for 1 h at room temperature. For cell proliferation detection, porcine SSCs were detected for the EdU incorporation by Cell-Light EdU Apollo488 in vitro Kit (Catalog No. C10310-3, RiboBio, Guangzhou, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The nucleus was labeled with DAPI (Catalog No. BD5010, Bioworld Technology, St. Louis Park, MN). A fluorescence microscope (Leica, Germany) was used for fluorescence observation and photographing.

m6A-RIP-seq and data analysis

m6A-RIP-seq was performed by Cloudseq Biotech Inc. (Shanghai, China) as previously described [46]. In brief, total RNA was extracted by using TRIzol (Catalog No. 15596026, Invitrogen). Denaturing agarose electrophoresis was used for confirming RNA integrity. Then, mRNA was isolated from total RNA by Seq-Star poly(A) mRNA Isolation Kit (Catalog No. AS-MB-006-01, Arraystar, Rockville, MD). The m6A RNA immunoprecipitation (IP) was conducted by GenSe m6A RNA IP Kit (Catalog No. GS-ET-001, GenSeq, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were constructed from the samples with and without m6A IP by NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit (Catalog No. E7760, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). Library was evaluated by the BioAnalyzer 2100 system (Catalog No. G2939BA, Agilent Technologies) and sequenced on an Illumina Hiseq 4000 (Catalog No. SY-401-4001, Illumina, San Diego, CA) with 150 bp paired-end reads.

After quality controlled by Q30, 3′ adaptor and low-quality reads were removed by cutadapt software (v1.9.3). Clean reads of all libraries (n = 3 for each group) were aligned to the reference genome (susScr11) by Hisat2 software (v2.0.4; −p 10 −q −−rna−strandness RF). Methylated sites were identified by MACS (v1.4) software (P < 0.00001) and visualized by Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV; v2.5.0). Motifs enriched in m6A peaks were identified using DREME [47]. Fifty nucleotides on each side of the top 1000 peaks in each sample were used for motif enrichment. GO analysis was performed by R package topGo (v3.2). The dot plot shows the gene ratio values of the top 10 significant enrichment terms.

Dot-blot

RNA was isolated and loaded on the positively charged nylon transfer membrane. After crosslinking by UV, the membrane was blocked by the 5% non-fat milk for 2 h, and followed by incubation with rabbit anti-m6A antibody (1:1000; Catalog No. 202003, Synaptic Systems, Göttingen, Germany) at 4 °C overnight. Then, the membrane was incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG at room temperature for 2 h followed by ECL imaging system (Catalog No. WBKLS0100, Millipore, Burlington, MA). Finally, the membrane was stained with 0.02% methylene blue to evaluate RNA amount.

RNA-seq and data analysis

The rRNAs were removed from total RNA by NEBNext rRNA Depletion Kit (Catalog No. E6310, New England Biolabs) following the manufacturer’s instruction. NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit (Catalog No. E7760, New England Biolabs) was used to construct RNA libraries. Library quality was confirmed by BioAnalyzer 2100 system (Catalog No. G2939BA, Agilent Technologies). Library sequencing was performed on an Illumina Hiseq 4000 (Catalog No. SY-401-4001, Illumina) with 150 bp paired end reads.

After raw data process (n = 3 for each group), high-quality clean reads were aligned to the reference genome (susScr11) with Hisat2 software (v2.0.4; −p 10 −q −−rna−strandness RF). Then, HTSeq software (v0.9.1) was used to get the raw count, and edgeR was used to perform normalization based on the Ensembl gtf gene annotation file (v11.1.103). The differentially expressed mRNA was identified and used for further analysis. The R package heatmap.2 was used for heat-map drawing.

m6A-RIP-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from porcine SPG, PS, and RS using TRIzol (Catalog No. 15596026, Invitrogen). mRNA was isolated using the PolyATtract mRNA Isolation Systems (Catalog No. Z5310, Promega, Madison, WI) following the manufacturer’s instructions. IP mixture was composed by 6 µg of rabbit anti-m6A antibody (Catalog No. 202003, Synaptic Systems), mRNA, IP buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 750 mM NaCl, and 0.5% NP-40), RNase inhibitor (Catalog No. AM2682, Invitrogen), and RNase-free water up to 500 µl in total volume. After being mixed by rotating for 2 h at 4 °C, the IP mixture was incubated with the Protein A beads (Catalog No. 10002D, Invitrogen) which have been washed for three times and blocked by 0.5 mg/ml BSA, followed by rotating overnight at 4 °C. Precipitated mRNA was eluted using elution buffer (1× IP buffer, 6.7 mM m6A). For the detection of the fold enrichment of m6A level, precipitated mRNA and input RNA were subjected to cDNA synthesis and qRT-PCR, respectively. The primers are listed in Table S3.

qRT-PCR

qRT-PCR analysis was performed with FastStart Essential DNA Green Master (Catalog No. 06402712001, Roche, Mannheim, Germany) using an IQ-5 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The relative expression was normalized to GAPDH and HPRT1, and then calculated using the comparative Ct method (2−ΔΔCt). The primers are listed in Table S3.

Ethical statement

All experimental procedures involving animals were approved by the Northwest A&F University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, China (Approval No. DK-20180375).

Data availability

The datasets generated in the current study have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive [48] at the National Genomics Data Center, Beijing Institute of Gemonics, Chinese Academy of Sciences / China National Center for Bioinformation (GSA: CRA003615), and are publicly accessible at https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zidong Liu: Conceptualization, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Xiaoxu Chen: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Pengfei Zhang: Validation, Investigation. Fuyuan Li: Validation, Investigation. Lingkai Zhang: Formal analysis. Xueliang Li: Writing – review & editing. Tao Huang: Investigation, Writing – original draft. Yi Zheng: Writing – review & editing. Taiyong Yu: Resources. Tao Zhang: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. Wenxian Zeng: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Hongzhao Lu: Writing – review & editing. Yinghua Lv: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Huayan Wang for polishing the language in the revised manuscript. We thank the Besun farm (Yangling, China) for providing the tissue samples. The research was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31572401) to Wen-xian Zeng, the Research Project of Shaanxi Science and Technology Department (Grant No. 2020NY-003) to Tao Zhang, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81703193) to Yinghua Lv.

Handled by Yun-Gui Yang

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences / China National Center for Bioinformation and Genetics Society of China.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gpb.2021.08.006.

Contributor Information

Wenxian Zeng, Email: zengwenxian2015@nwafu.edu.cn.

Hongzhao Lu, Email: lhz780823@snut.edu.cn.

Yinghua Lv, Email: yinghua.lv@nwafu.edu.cn.

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Desrosiers R., Friderici K., Rottman F. Identification of methylated nucleosides in messenger RNA from Novikoff hepatoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1974;71:3971–3975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.10.3971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frye M., Harada B.T., Behm M., He C. RNA modifications modulate gene expression during development. Science. 2018;361:1346–1349. doi: 10.1126/science.aau1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jia G., Fu Y., Zhao X., Dai Q., Zheng G., Yang Y., et al. N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:885–887. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng G., Dahl J., Niu Y., Fedorcsak P., Huang C.M., Li C., et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell. 2013;49:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harper J.E., Miceli S.M., Roberts R.J., Manley J.L. Sequence specificity of the human mRNA N6-adenosine methylase in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:5735–5741. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.19.5735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liao S., Sun H., Xu C. YTH domain: a family of N6 -methyladenosine (m6A) readers. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2018;16:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2018.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang H., Zuo H., Liu J., Wen F., Gao Y., Zhu X., et al. Loss of YTHDF2-mediated m6A-dependent mRNA clearance facilitates hematopoietic stem cell regeneration. Cell Res. 2018;28:1035–1038. doi: 10.1038/s41422-018-0082-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiang Y., Laurent B., Hsu C.H., Nachtergaele S., Lu Z., Sheng W., et al. RNA m6A methylation regulates the ultraviolet-induced DNA damage response. Nature. 2017;543:573–576. doi: 10.1038/nature21671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Batista P., Molinie B., Wang J., Qu K., Zhang J., Li L., et al. m6A RNA modification controls cell fate transition in mammalian embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:707–719. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lence T., Akhtar J., Bayer M., Schmid K., Spindler L., Ho C.H., et al. m6A modulates neuronal functions and sex determination in Drosophila. Nature. 2016;540:242–247. doi: 10.1038/nature20568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin Z., Hsu P.J., Xing X., Fang J., Lu Z., Zou Q., et al. Mettl3-/Mettl14-mediated mRNA N6-methyladenosine modulates murine spermatogenesis. Cell Res. 2017;27:1216–1230. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cui Q., Shi H., Ye P., Li L., Qu Q., Sun G., et al. m6A RNA methylation regulates the self-renewal and tumorigenesis of glioblastoma stem cells. Cell Rep. 2017;18:2622–2634. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.02.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griswold M.D. Spermatogenesis: the commitment to meiosis. Physiol Rev. 2016;96:1–17. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mäkelä J.A., Hobbs R.M. Molecular regulation of spermatogonial stem cell renewal and differentiation. Reproduction. 2019;158:R169–R187. doi: 10.1530/REP-18-0476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toshimori K., Ito C. Formation and organization of the mammalian sperm head. Arch Histol Cytol. 2003;66:383–396. doi: 10.1679/aohc.66.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunter N. Meiotic recombination: the essence of heredity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015;7 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kleene K.C. Connecting cis-elements and trans-factors with mechanisms of developmental regulation of mRNA translation in meiotic and haploid mammalian spermatogenic cells. Reproduction. 2013;146:R1–19. doi: 10.1530/REP-12-0362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X., Lu Z., Gomez A., Hon G.C., Yue Y., Han D., et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature. 2014;505:117–120. doi: 10.1038/nature12730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X., Zhao B.S, Roundtree I., Lu Z., Han D., Ma H., et al. N6-methyladenosine modulates messenger RNA translation efficiency. Cell. 2015;161:1388–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiao W., Adhikari S., Dahal U., Chen Y.S., Hao Y.J., Sun B.F., et al. Nuclear m6A reader YTHDC1 regulates mRNA splicing. Mol Cell. 2016;61:507–519. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu K., Yang Y., Feng G.H., Sun B.F., Chen J.Q., Li Y.F., et al. Mettl3-mediated m6A regulates spermatogonial differentiation and meiosis initiation. Cell Res. 2017;27:1100–1114. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang C., Klukovich R., Peng H., Wang Z., Yu T., Zhang Y., et al. ALKBH5-dependent m6A demethylation controls splicing and stability of long 3′-UTR mRNAs in male germ cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E325–E333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717794115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wojtas M.N., Pandey R.R., Mendel M., Homolka D., Sachidanandam R., Pillai R.S. Regulation of m6A transcripts by the 3′→5′ RNA helicase YTHDC2 is essential for a successful meiotic program in the mammalian germline. Mol Cell. 2017;68:374–387. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dixon L.K., Stahl K., Jori F., Vial L., Pfeiffer D.U. African swine fever epidemiology and control. Annu Rev Anim Biosci. 2020;8:221–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev-animal-021419-083741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu T., Chen X., Li T., Li X., Lyu Y., Fan X., et al. Histone methyltransferase SETDB1 maintains survival of mouse spermatogonial stem/progenitor cells via PTEN/AKT/FOXO1 pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech. 2017;1860:1094–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu T, Zhang P, Li T, Chen X, Zhu Z, Lyu Y, et al. SETDB1 plays an essential role in maintenance of gonocyte survival in pigs. Reproduction 2017;154:23–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.An J, Zhang X, Qin J, Wan Y, Hu Y, Liu T, et al. The histone methyltransferase ESET is required for the survival of spermatogonial stem/progenitor cells in mice. Cell Death Dis 2014;5:e1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Goertz M.J., Wu Z., Gallardo T.D., Hamra F.K., Castrillon D.H. Foxo1 is required in mouse spermatogonial stem cells for their maintenance and the initiation of spermatogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3456–3466. doi: 10.1172/JCI57984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng Y., Feng T., Zhang P., Lei P., Li F., Zeng W. Establishment of cell lines with porcine spermatogonial stem cell properties. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2020;11:33. doi: 10.1186/s40104-020-00439-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu R., Liu Y., Zhao Y., Bi Z., Yao Y., Liu Q., et al. m6A methylation controls pluripotency of porcine induced pluripotent stem cells by targeting SOCS3/JAK2/STAT3 pathway in a YTHDF1/YTHDF2-orchestrated manner. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:171. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1417-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyer K.D, Saletore Y., Zumbo P., Elemento O., Mason C.E, Jaffrey S.R. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3′ UTRs and near stop codons. Cell. 2012;149:1635–1646. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dominissini D., Moshitch-Moshkovitz S., Schwartz S., Salmon-Divon M., Ungar L., Osenberg S., et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature. 2012;485:201–206. doi: 10.1038/nature11112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramalho-Santos J., Varum S., Amaral S., Mota P.C., Sousa A.P., Amaral A. Mitochondrial functionality in reproduction: from gonads and gametes to embryos and embryonic stem cells. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15:553–572. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palmer N., Talib S.Z.A., Kaldis P. Diverse roles for CDK-associated activity during spermatogenesis. FEBS Lett. 2019;593:2925–2949. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hao S.L., Ni F.D., Yang W.X. The dynamics and regulation of chromatin remodeling during spermiogenesis. Gene. 2019;706:201–210. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2019.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steger K. Haploid spermatids exhibit translationally repressed mRNAs. Anat Embryol (Berl) 2001;203:323–334. doi: 10.1007/s004290100176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bettegowda A., Wilkinson M.F. Transcription and post-transcriptional regulation of spermatogenesis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2010;365:1637–1651. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gou L., Dai P., Yang J., Xue Y., Hu Y., Zhou Y., et al. Pachytene piRNAs instruct massive mRNA elimination during late spermiogenesis. Cell Res. 2014;24:680–700. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang P., Kang J., Gou L., Wang J., Xue Y., Skogerboe G., et al. MIWI and piRNA-mediated cleavage of messenger RNAs in mouse testes. Cell Res. 2015;25:193–207. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brunet A., Bonni A., Zigmond M.J., Lin M.Z., Juo P., Hu L.S., et al. Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a Forkhead transcription factor. Cell. 1999;96:857–868. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matoba S., Liu Y., Lu F., Iwabuchi K., Shen L., Inoue A., et al. Embryonic development following somatic cell nuclear transfer impeded by persisting histone methylation. Cell. 2014;159:884–895. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu W., Li J., He C., Wen J., Ma H., Rong B., et al. METTL3 regulates heterochromatin in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2021;591:317–321. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03210-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu J., Gao M., He J., Wu K., Lin S., Jin L., et al. The RNA m6A reader YTHDC1 silences retrotransposons and guards ES cell identity. Nature. 2021;591:322–326. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng Y., He Y., An J., Qin J., Wang Y., Zhang Y., et al. THY1 is a surface marker of porcine gonocytes. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2014;26:533–539. doi: 10.1071/RD13075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen X., Che D., Zhang P., Li X., Yuan Q., Liu T., et al. Profiling of miRNAs in porcine germ cells during spermatogenesis. Reproduction. 2017;154:789–798. doi: 10.1530/REP-17-0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Y., Zeng L., Liang C., Zan R., Ji W., Zhang Z., et al. Integrated analysis of transcriptome-wide m6A methylome of osteosarcoma stem cells enriched by chemotherapy. Epigenomics. 2019;11:1693–1715. doi: 10.2217/epi-2019-0262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bailey TL. DREME: motif discovery in transcription factor ChIP-seq data. Bioinformatics 2011;27:1653–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Chen T., Chen X., Zhang S., Zhu J., Tang B., Wang A., et al. The Genome Sequence Archive Family: toward explosive data growth and diverse data types. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2021;19:578–583. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2021.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated in the current study have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive [48] at the National Genomics Data Center, Beijing Institute of Gemonics, Chinese Academy of Sciences / China National Center for Bioinformation (GSA: CRA003615), and are publicly accessible at https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa.