Abstract

Serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 7 (SRSF7), a known splicing factor, has been revealed to play oncogenic roles in multiple cancers. However, the mechanisms underlying its oncogenic roles have not been well addressed. Here, based on N6-methyladenosine (m6A) co-methylation network analysis across diverse cell lines, we find that the gene expression of SRSF7 is positively correlated with glioblastoma (GBM) cell-specific m6A methylation. We then indicate that SRSF7 is a novel m6A regulator, which specifically facilitates the m6A methylation near its binding sites on the mRNAs involved in cell proliferation and migration, through recruiting the methyltransferase complex. Moreover, SRSF7 promotes the proliferation and migration of GBM cells largely dependent on the presence of the m6A methyltransferase. The two m6A sites on the mRNA for PDZ-binding kinase (PBK) are regulated by SRSF7 and partially mediate the effects of SRSF7 in GBM cells through recognition by insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 2 (IGF2BP2). Together, our discovery reveals a novel role of SRSF7 in regulating m6A and validates the presence and functional importance of temporal- and spatial-specific regulation of m6A mediated by RNA-binding proteins (RBPs).

Keywords: m6A, Serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 7, Cell-specific regulation, Glioblastoma, PDZ-binding kinase

Introduction

Serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 7 (SRSF7, also known as 9G8) belongs to the serine/arginine (SR) protein family, which contains 7 canonical members (SRSF1–7) [1]. It is previously known as a splicing factor to regulate alternative splicing as well as a regulator of alternative polyadenylation (APA) [2], [3], [4], [5]. SRSF7 is also an adaptor of nuclear RNA export factor (NXF1), which exports mature RNAs out of nucleus, and plays important roles in coupling RNA alternative splicing and APA to mRNA export [5]. It has been reported that hyperphosphorylated SRSF7 binds to pre-mRNA for splicing and SRSF7 becomes hypophosphorylated during splicing, and the later form of SRSF7 can bind to NXF1 for the subsequent export of the spliced RNAs [3].

The oncogenic roles of SRSF7 have been widely reported. It was discovered as a critical gene required for cell growth or viability in multiple cancer cell lines based on a genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 screening [6]. Aberrantly elevated expression of SRSF7 was observed in lung cancer, colon cancer, and gastric cancer [7], [8], [9]. It was also reported to be highly expressed in glioblastoma [GBM, world health organization (WHO) grade IV glioma] and associated with poor patient outcome [10]. However, although SRSF7 has been reported to regulate splicing, APA, and mRNA export, the mechanisms underlying its oncogenic roles have not been well addressed.

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is a reversible RNA modification prevalent in eukaryotic mRNAs and long non-coding RNAs [11], [12], [13], [14]. It plays critical roles in various biological processes, including stem cell differentiation, immune system, learning and memory, and cancer development [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20]. m6A modification is marked by the m6A methyltransferase (also known as “writer”) complex, which consists of methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3), methyltransferase-like 14 (METTL14), Wilms tumor 1-associating protein (WTAP), vir-like m6A methyltransferase associated (VIRMA), zinc finger CCCH-type containing 13 (ZC3H13), RNA-binding motif protein 15/15B (RBM15/15B), and cbl proto-oncogene like 1 (CBLL1, also known as HAKAI) [21], [22], [23]. m6A can also be removed by demethylases (also known as “erasers”) including fat mass and obesity associated gene (FTO) and alkB homolog 5 (ALKBH5) [24], [25]. The m6A-modified RNAs are recognized by a series of readers such as YTH-domain containing proteins (YTHDF1–3 and YTHDC1–2) [26]. For instance, YTHDF2 facilitates the degradation of methylated RNAs and is important for cell fate transitions [27], [28], [29], [30]. Insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 1–3 (IGF2BP1–3) are a different type of readers that can stabilize the methylated RNAs and play oncogenic roles in multiple types of cancers [31]. In addition, m6A can also down-regulate gene expression through degrading chromosome-associated regulatory RNAs (carRNAs) [32] and up-regulate gene expression by demethylating H3K9me2 histone modification [33].

Unlike global regulation of m6A by the methyltransferase complex, selective modification of m6A on specific targets can shape the cell-specific methylome and mediate specific functions in diverse biological systems. There are different mechanisms that confer the specificities of m6A. Although the components of methyltransferase complex VIRMA and ZC3H13 mainly affect the m6A at stop codons and 3′ untranslated regions (3′ UTRs), their substantial effects on m6A suggest fundamental but limited specificities for m6A installation, consistent with that they do not have RNA-binding domain and ZC3H13 works to take the methyltransferase into nucleus [34], [35]. Since m6A occurs co-transcriptionally, m6A could be specifically regulated co-transcriptionally through H3K36me3 and transcription factors. Depletion of H3K36me3 also results in global reduction of m6A, especially the m6A at 3′ UTRs and protein-coding regions, suggesting a fundamental but relatively low specificity in regulation of m6A [36]. On the other hand, transcription factors CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein zeta (CEBPZ) and sma- and mad-related protein (SMAD) family member 2/3 (SMAD2/3) can recruit the methyltransferase to methylate the nascent RNAs being transcribed by them and play important roles in acute myeloid leukemia oncogenesis and stem cell differentiation, respectively [37]. The specificities of transcription factors are conferred by their binding specificities on the promoters. Therefore, they can mediate highly specific methylation other than global regulation of m6A. However, transcription factors usually bind at the 5′ end, and thus cannot precisely direct the m6A modification at specific loci of the RNAs. In contrast to transcription factors, which select RNAs other than sites, RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) have the potential to precisely guide the methylation at specific sites of RNAs in the similar manner as they regulate alternative splicing [38]. Recently, we developed a co-methylation network based computational framework and revealed a large number of RBPs acting as m6A trans-regulators to specifically regulate m6A to form cell-specific m6A methylomes [39]. However, firm experimental validations and profound characterizations are still lacking, and whether these RBPs play important functional roles through regulating the m6A of specific sites is not clear either.

In this study, we find that SRSF7 specifically regulates m6A on the genes involved in cell proliferation and migration, and plays oncogenic roles through recruiting the m6A methyltransferase complex near its binding sites in GBM cells. Our discovery reveals a novel role of SRSF7 in regulating m6A and timely confirms the existence and importance of RBP-mediated temporal- and spatial-specific regulation of m6A.

Results

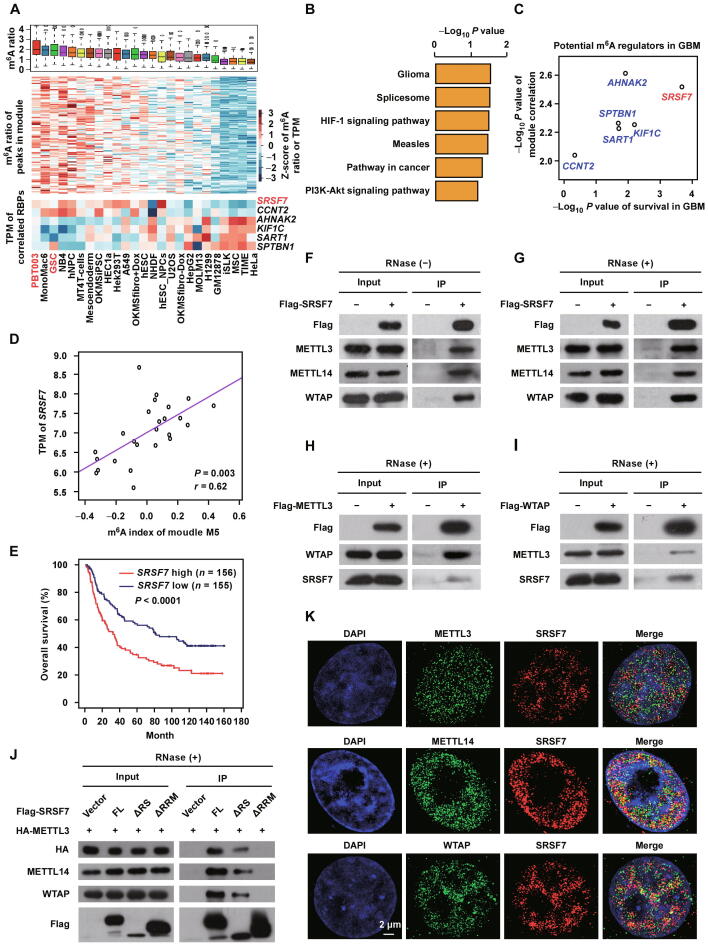

SRSF7 is a potential m6A regulator that interacts with m6A methyltransferase complex

To elucidate how cells establish cell-specific m6A methylomes, we previously developed a co-methylation network based computational framework to systematically identify the cell-specific trans-regulators of m6A [39]. We first identified the RBPs with gene expression correlated with the m6A ratio (level) of specific co-methylation module (a subset of co-methylated m6A peaks) across 25 different cell lines (the detailed information of cell lines can be found in the supplementary table of [39]). By further investigating the enrichment of binding targets of the RBPs within their correlated modules based on cross-linking and immunoprecipitation combined with high throughput sequencing (CLIP-seq) data of 157 RBPs and motifs of 89 RBPs, we revealed widespread cell-specific trans-regulation of m6A and predicted 32 high-confidence m6A regulators [39]. It is of great importance to understand whether these RBP-mediated specific regulations of m6A play critical functional roles. This co-methylation network provides the information about cell specificities of different modules, which gives valuable clues for us to speculate the functions of these modules. We realized that one of the modules (M5) was highly methylated in two GBM cell lines (PBT003 and GSC) (Figure 1A). Coincidently, although not significant enough to bear multiple testing correction, the mostly enriched Gene Ontology (GO) terms for the corresponding genes of this module were glioma- and cancer-related pathways (Figure 1B), suggesting that the specific methylation of this module may play a role in the development of glioma. We then tried to dissect the RBPs that direct the specific m6A methylation of this glioma-related module. As we have previously determined [39] and shown at the bottom of Figure 1A, there were 6 RBPs with gene expression significantly correlated with the m6A index (the first component of principal component analysis) of module M5, including 2 positive and 4 negative correlations. We further analyzed the prognostic relevance of these 6 RBPs in GBM patients from Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA) dataset [40]. We found that the expression of SRSF7 was most significantly correlated with the survival time of GBM patients (Figure 1C). Highly expression of SRSF7 was associated with highly m6A methylation of the m6A sites in this module and poor prognosis of the GBM patients (Figure 1D and E). Although the other 5 RBPs may also regulate m6A of this module in GBM cells, they cannot really affect the prognosis of GBM patients, we therefore focused on SRSF7 to investigate whether and how it plays important roles in GBM through specific regulation of m6A.

Figure 1.

SRSF7 is a potential m6A regulator that interacts with m6A methyltransferase complex

A. The Box plot (upper panel) and heatmap (middle panel) representing the m6A ratios of the m6A peaks within the co-methylation module M5 as well as the heatmap (lower panel) representing the gene expression patterns of the RBPs that significantly correlated with the m6A indexes of M5. The cell lines were sorted according to the m6A indexes of M5, and GBM cell lines were colored red. B. GO enrichment analysis of corresponding genes in module M5. C. The Y-axis represents the log-transformed P values of the correlations between the gene expression of 6 RBPs and the m6A indexes of co-methylation module M5; the X-axis represents the log-transformed P values of the overall survival of these 6 RBPs in GBM patients. D. Scatter plot representing the correlations between the expression of SRSF7 and m6A indexes of module M5 across 25 cell lines. The P value and correlation coefficient are indicated at the bottom right corner. E. Kaplan–Meier analysis of overall survival based on SRSF7 expression of GBM patients from CGGA dataset. F. and G. Western blots showing the interactions of Flag-tagged SRSF7 with endogenous METTL3, METTL14, and WTAP without (F) and with (G) RNase treatment in U87MG cells. H. and I. Western blots showing the interactions of Flag-tagged METTL3 (H) and WTAP (I) with endogenous SRSF7 with RNase treatment in U87MG cells. J. Western blot showing the interactions of Flag-tagged FL and truncated SRSF7 with HA-tagged METTL3, endogenous METTL14, and endogenous WTAP with RNase treatment in U87MG cells. K. 3D-SIM imaging indicating the colocalization of SRSF7 with METTL3, METTL14, and WTAP in the nucleus. Scale bar, 2 μm. M5, module 5; RBP, RNA-binding protein; GBM, glioblastoma; TPM, transcripts per million; GO, Gene Ontology; CGGA, Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas; IP, immunoprecipitation; FL, full-length; ΔRS, truncated SRSF7 with arginine/serine domain deleted; ΔRRM, truncated SRSF7 with RNA recognition motif domain deleted; HA, hemagglutinin; 3D-SIM, 3D structured illumination microscopy; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

To test whether SRSF7 is a genuine m6A regulator that facilitates the installation of m6A at specific m6A sties, we first examined whether SRSF7 can interact with the core m6A methyltransferase complex composed of METTL3, METTL14, and WTAP in a GBM cell line U87MG. Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assays revealed that Flag-tagged SRSF7 could pull down the endogenous METTL3, METTL14, and WTAP independent of RNA (Figure 1F and G). Reciprocally, both Flag-tagged METTL3 and WTAP could also pull down endogenous SRSF7 in an RNA-independent manner, respectively, in U87MG cells (Figure 1H and I). Similar results were observed in 293 T cells (Figure S1A), suggesting that the interaction between SRSF7 and the methyltransferase complex is a universal mechanism. In addition, we performed Co-IP using truncated SRSF7 with RNA recognition motif (RRM) domain or arginine/serine (RS) domain deleted in U87MG cells, and found that deletion of RRM domain other than RS domain could disrupt the interactions with METTL3, METTL14, and WTAP (Figure 1J, Figure S1B), indicating that SRSF7 interacts with the methyltransferase complex through its RRM domain.

We then used 3D structured illumination microscopy (3D-SIM) super-resolution microscopy to test the protein colocalization between SRSF7 and the m6A methyltransferase complex in U87MG cells. We found that a portion of SRSF7 proteins were colocalized with portions of METTL3, METTL14, and WTAP in the nucleus, respectively (Figure 1K), implying that at least a part of SRSF7 proteins can specifically regulate m6A. The aforementioned results suggest that SRSF7 may be able to regulate m6A through recruiting the m6A methyltransferase complex.

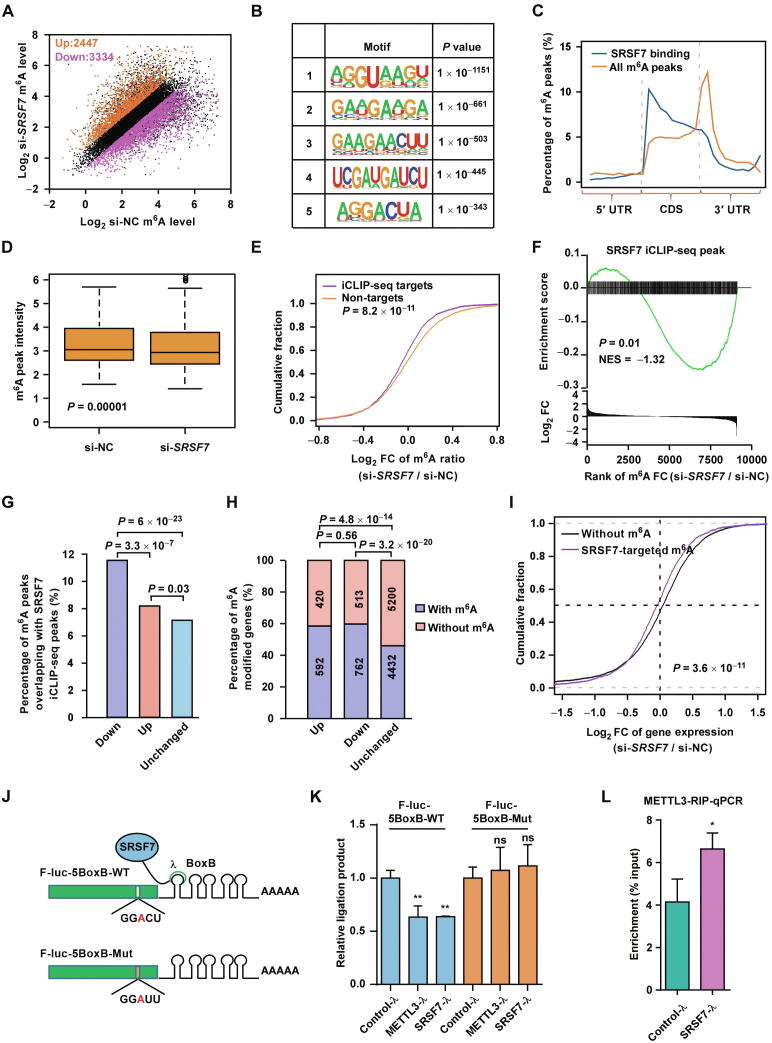

SRSF7 specifically facilitates m6A modification near its binding sites

To further investigate whether SRSF7 regulates m6A modification, we knocked down SRSF7 and performed m6A-seq to examine the m6A alteration due to SRSF7 depletion in U87MG cells. The typical m6A motif was enriched in the m6A peaks of both knockdown and control cells (Figure S2A). As shown in Figure S2B, the m6A peaks were enriched near the stop codons in both knockdown and control cells, which is consistent with previous studies [11], [12]. In contrast to the RBPs in the m6A methyltransferase complex, which usually cause massive loss of m6A upon depletion [22], depletion of SRSF7 did not alter the distribution (Figure S2B) and overall peak intensities of the m6A peaks (Figure S2C), suggesting that SRSF7 may be a different type of m6A regulator that regulates a small number of highly specific m6A sites in U87MG cells.

We then determined the differentially methylated m6A sites between SRSF7 knockdown and control to understand the specific sites regulated by SRSF7. After SRSF7 knockdown, 3334 m6A peaks in 2440 genes were down-regulated; in contrast, only 2447 peaks in 1850 genes were up-regulated (Figure 2A, Figure S2D). GO analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis showed that these differentially methylated genes were enriched in terms including cell division, cell migration, cell proliferation, and pathway in cancer (Figure S2E and F).

Figure 2.

SRSF7 specifically facilitates m6A methylation near its binding sites via recruiting METTL3

A. Scatter plot showing the up-regulated (orange) and down-regulated (purple) m6A peaks in si-SRSF7 as compared with si-NC in U87MG cells. The numbers of the up-regulated and down-regulated peaks are indicated. B. The most significantly enriched motifs in the iCLIP-seq identified SRSF7-binding peaks. C. Normalized distributions of m6A peaks and SRSF7 iCLIP-seq peaks across 5′ UTR, CDS, and 3′ UTR of mRNA. D. Box plot comparing the m6A ratios of the SRSF7-targeted m6A peaks in control and SRSF7-knockdown U87MG cells. E. Plot of cumulative fraction of log2 FC of m6A ratios upon SRSF7 knockdown using si-SRSF7 for the m6A peaks overlapping or non-overlapping with SRSF7 iCLIP-seq peaks. P value is determined by two-tailed Wilcoxon test. F. Plot of GSEA analysis displaying the distribution of SRSF7 iCLIP-seq peaks (upper panel) across the m6A peaks ranked by log2 FC of m6A ratios upon SRSF7 knockdown (si-SRSF7) (lower panel). The m6A peaks overlapping with SRSF7 iCLIP-seq peaks are indicated by vertical lines in the upper panel. The P value and NES of GSEA are indicated. G. Bar plot comparing the percentages of m6A peaks overlapping with SRSF7 iCLIP-seq peaks for down-regulated, up-regulated, and unchanged m6A peaks upon SRSF7 knockdown, respectively. The pairwise P values of two-tailed Chi-square tests are indicated at the top. H. Bar plot comparing the percentages of m6A modified genes for genes with down-regulated, up-regulated, and unchanged gene expression upon SRSF7 knockdown, respectively. The pairwise P values of two-tailed Chi-square tests are indicated at the top. I. Plot of cumulative fraction of log2 FC of gene expression upon SRSF7 knockdown for unmethylated genes and genes with SRSF7-targeted m6A peaks, respectively. P value of two-tailed Wilcoxon test is indicated. J. Schematic diagram displaying the constructs of the SRSF7 tethering assay with GGACU m6A motif (upper) and disruptive GGAUU motif (lower). K. Bar plot comparing the SELECT method measured relative ligation products, which anti-correlated with the m6A levels, for the m6A sites in F-luc-5BoxB without or with mutation in the m6A motif in U87MG cells transfected with control-λ, SRSF7-λ, and METTL3-λ, respectively. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). **, P < 0.01; ns, no significant difference. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test. L. Bar plot comparing the METTL3 RIP-qPCR enrichment of the F-luc mRNA in U87MG cells transfected with SRSF7-λ and control-λ, respectively. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05. Student’s two-tailed t-test. NC, negative control; iCLIP-seq, individual-nucleotide resolution UV crosslinking and immunoprecipitation combined with high throughput sequencing; UTR, untranslated region; CDS, coding sequence; FC, fold change; GSEA, gene set enrichment analysis; NES, normalized enrichment score; SELECT, single-base elongation- and ligation-based quantitative polymerase chain reaction amplification; SEM, standard error of mean; ANOVA, analysis of variance; RIP-qPCR, RNA immunoprecipitation-quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

To further confirm that SRSF7 regulates the m6A sites through binding near the m6A sites, we performed individual-nucleotide resolution UV crosslinking and immunoprecipitation combined with high throughput sequencing (iCLIP-seq) [41] for SRSF7 to identify the transcriptome-wide binding sites of SRSF7 in U87MG cells. We identified 40,476 iCLIP-seq peaks using CLIP Tool Kit (CTK) [42] (Table S1). The enriched motifs were similar as the previously reported motif of SRSF7 (GAYGAY) [43] (Figure 2B), suggesting the high reliability of our iCLIP-seq data. Interestingly, the m6A motif was also enriched in the SRSF7 iCLIP-seq peaks (Figure 2B), suggesting the colocalization of SRSF7 with m6A sites. We found that only 7.9% and 3.1% of the peaks were in introns and non-coding RNAs, respectively; in contrast, 66.8% of the peaks were in protein-coding regions, which are similar as the distribution of m6A (Figure S2G). However, the peaks were more enriched at the 5′ end of the protein-coding regions, which was distinct from m6A peaks; while the peaks colocalized with m6A peaks were enriched at both 5′ end and 3′ end (Figure 2C, Figure S2H), further suggesting that SRSF7 specifically regulates only a portion of m6A peaks other than global regulation.

We were then interested in whether SRSF7 binding were related to the m6A alteration due to SRSF7 depletion. We found that although the overall m6A ratios of all m6A peaks do not change upon SRSF7 knockdown, the m6A ratios of m6A peaks colocalized with SRSF7 iCLIP-seq peaks were significantly down-regulated upon SRSF7 knockdown (Figure 2D), suggesting that SRSF7 can only promote m6A modification near its binding sites. As compared with the m6A peaks unbound by SRSF7, the m6A ratio of SRSF7-bound m6A peaks was significantly down-regulated due to SRSF7 knockdown (Figure 2E), indicating that SRSF7 specifically facilitates the m6A modification near its binding sites. As shown in Figure 2F, we also revealed significant enrichment of SRSF7 iCLIP-seq peaks in (or overlap with) the down-regulated m6A peaks upon SRSF7 knockdown. In addition, the SRSF7-binding sites were significantly enriched in m6A peaks down-regulated upon SRSF7 knockdown as compared with the up-regulated and unchanged m6A peaks (Figure 2G), further supporting that SRSF7 binding results in locally enhanced other than decreased m6A methylation. On the other hand, although the module was constructed from diverse cell lines, the SRSF7-binding sites in U87MG cells were still marginally significantly enriched (P = 0.03) in the orange module, which is a larger module merged by M5 and other 4 correlated modules, as compared with other modules. The m6A peaks in the orange module were also significantly down-regulated upon SRSF7 knockdown as compared with the m6A peaks in other modules (Figure S2I), suggesting that SRSF7 promotes the m6A modification of this module.

SRSF7 significantly regulates gene expression through regulating m6A

We then studied whether SRSF7 affects the gene expression through regulating m6A in U87MG cells. The expression levels of 1012 and 1275 genes were up-regulated and down-regulated, respectively, due to SRSF7 knockdown (Figure S3A). GO enrichment analysis found that the down-regulated genes were enriched in terms such as cell division, cell migration, and cell cycle (Figure S3B), consistent with the GO terms enriched in differentially methylated genes (Figure S2E). However, the up-regulated genes were enriched in terms macroautophagy, vesicle docking, and protein transport (Figure S3C), which were quite different from the GO terms enriched in differentially methylated genes (Figure S2E). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) also supported that the gene expression changes were involved in cell division, cell cytoskeleton, and cell cycle (Figure S3D–F). We found that both the up-regulated genes and down-regulated genes were significantly enriched for m6A modified genes as compared with the genes without expression change (P = 4.8 × 10−14 for up-regulated genes; P = 3.2 × 10−20 for down-regulated genes; two-tailed Chi-square test; Figure 2H). This result suggests that SRSF7 can both up-regulate and down-regulate gene expression through m6A, consistent with the previous reports that m6A has dual effects on gene expression depends on how these m6A sites are recognized by diverse m6A readers [27], [31], [32], [33]. To further clarify the direct effects of SRSF7, we investigated the effects of SRSF7 binding on gene expression though regulating m6A. As shown in Figure 2I, the genes with SRSF7-targeted m6A peaks were overall significantly down-regulated as compared with unmethylated genes upon SRSF7 knockdown (P = 3.6 × 10−11, two-tailed Wilcoxon test; Figure 2I).

Artificially tethering SRSF7 on RNA directs de novo m6A methylation through recruiting METTL3

We then performed a tethering assay to test whether direct tethering of SRSF7 protein was sufficient to dictate the m6A modification nearby in U87MG cells. For this purpose, we respectively fused the full-length coding sequences (CDSs) of SRSF7 and METTL3 with λ peptide, which can specifically recognizes BoxB RNA [44]. We utilized a previously established F-luc-5BoxB luciferase reporter, which has five BoxB sequence in the 3′ UTR and a m6A motif (GGACU) 73 bp upstream of the stop codon (Figure 2J) [34]. We found that tethering SRSF7 and METTL3 could both significantly up-regulate the modification of m6A site on the reporter to the similar degree using single-base elongation- and ligation-based quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) amplification (SELECT) method [45] (Figure 2K), indicating that SRSF7 can similarly dictate the methylation of nearby m6A site as METTL3. A disruptive synonymous point mutation in the m6A motif, which changes the GGACU to GGAUU, completely disrupted the effects on m6A change by tethering SRSF7 and METTL3, respectively (Figure 2K), indicating the high reliability of the tethering assay. In addition, we found that binding of METTL3 on F-luc mRNA was significantly up-regulated when tethering SRSF7 to F-luc-5BoxB, indicating that SRSF7 promotes the installation of m6A through recruiting METTL3 (Figure 2L).

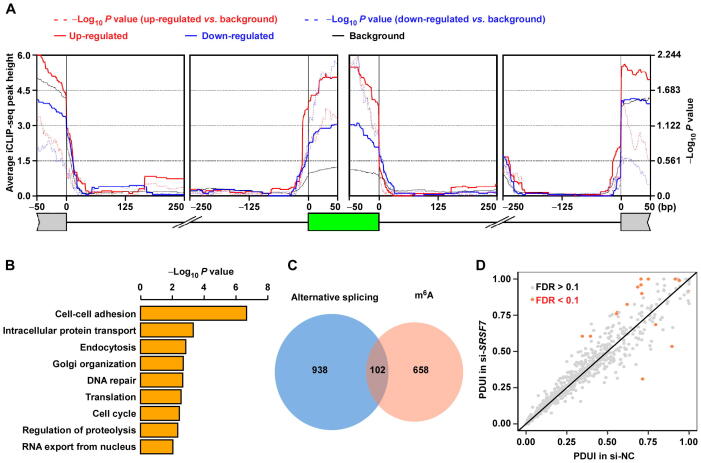

SRSF7 specifically targets and facilitates the methylation of m6A sites on genes involved in cell proliferation and migration

Since SRSF7 iCLIP-seq peaks are significantly enriched in down-regulated m6A peaks upon SRSF7 knockdown (Figure 2G), to further dissect the specific m6A targets that directly regulated by SRSF7 binding, we intersected the 40,476 SRSF7 iCLIP-seq peaks and 3334 down-regulated m6A peaks upon SRSF7 knockdown, and obtained 911 SRSF7 directly regulated m6A peaks in 760 genes (Figure 3A; Table S2). As shown in Figure 3B, the distribution of SRSF7 directly regulated m6A peaks was still similar as the canonical distribution of m6A peaks, suggesting that SRSF7 are not accounting for the formation of the canonical topology of m6A like VIRMA [34]. GO and KEGG enrichment analyses revealed that the genes with SRSF7 directly regulated m6A peaks were mainly involved in cell migration, cell adhesion, cell proliferation, glioma, cell cycle, and pathways in cancer (Figure 3C, Figure S4A). In contrast, the genes with SRSF7 iCLIP-seq peaks not colocalized with m6A peaks were enriched in totally different terms which were not directly related to cell proliferation and migration (Figure S4B). The results suggest that the elevated expression of SRSF7 in GBM patients may involve in migration and proliferation of the cancer cells through regulating the m6A methylation of corresponding genes.

Figure 3.

SRSF7 specifically targets and facilitates the methylation of m6Asiteson genes involved in cell proliferation and migration

A. Venn diagram showing the overlapping of down-regulated m6A peaks upon SRSF7 knockdown and SRSF7 iCLIP-seq peaks. B. Normalized distribution of the overlapping m6A peaks in (A) across 5′ UTR, CDS, and 3′ UTR of mRNA. C. GO enrichment of the corresponding genes with the overlapping m6A peaks in (A). D. and E. Tracks displaying the read coverage of IPs and inputs of m6A-seq as well as the SRSF7 iCLIP-seq on PBK and MCM4. The SRSF7 directly regulated m6A peaks are highlighted in green. The Y-axes of si-NC and si-SRSF7 were differently used to intuitionally indicate the m6A differences other than expression differences. F.–I. Validation of m6A changes of single-nucleotide m6A sites on PBK at 1041 and 1071 (F and G), MCM4 at 1515 (H), and ROBO1 at 672 (I) using the SELECT method in U87MG cells transfected with scramble (si-NC), two siRNAs of SRSF7 (si-SRSF7-1, si-SRSF-2), and two siRNAs of METTL3 (si-METTL3-1, si-METTL3-2), respectively. The tested m6A motifs are indicated on the schematic structures of mRNAs at the top panels. The green boxes represent protein-coding regions, the thin lines flanking the green boxes represent UTRs. Arrows indicate the primers for SELECT. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test. J.–L. Bar plots comparing the RIP-qPCR determined relative enrichment of METTL3 (J), METTL14 (K), and WTAP (L) binding to the mRNAs of PBK, MCM4, and ROBO1 in control and SRSF7-knockdown U87MG cells. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Student’s two-tailed t-test.

To further validate the 911 SRSF7 directly regulated m6A peaks, we then selected 3 m6A peaks in 3 tumorigenic genes involved in migration or proliferation of GBM, respectively. All of the 3 peaks in PDZ-binding kinase (PBK), minichromosome maintenance complex component 4 (MCM4), and roundabout guidance receptor 1 (ROBO1) were successfully validated (Figure 3D and E, Figure S4C). We detected 4 single-nucleotide m6A sites in the 3 m6A peaks according to the public available miCLIP-seq data [46], [47]. The methylation levels of the 4 m6A sites in the 3 m6A peaks (PBK at 1041 and 1071, MCM4 at 1515, and ROBO1 at 672) were significantly decreased upon SRSF7 knockdown and METTL3 knockdown, respectively, based on SELECT method [45] (Figure 3F–I), indicating that SRSF7 has similar effects of promoting m6A modification as METTL3 on these selected m6A sites. We also found that the binding efficiencies of METTL3, METTL14, and WTAP on the RNAs of these 3 genes were significantly reduced upon SRSF7 knockdown based on RNA immunoprecipitation-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RIP-qPCR) (Figure 3J–L). Collectively, these results show that SRSF7 promotes m6A modification on tumorigenic genes through recruiting METTL3.

SRSF7 promotes proliferation and migration of GBM cells partially dependent on METTL3

Since SRSF7 specifically regulates the m6A modification of tumorigenic genes in GBM cells, we therefore wanted to confirm whether it plays important roles in GBM. We found that the expression of SRSF7 was highly elevated in glioma specimens, especially in GBM (grade IV) tissues according to CGGA data (Figure 4A), which was confirmed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) in human glioma tissues (Figure 4B) and consistent with a previous report [10]. To further confirm this finding, we tested the mRNA expression of SRSF7 in 11 GBM cell lines as well as normal human astrocytes (NHAs). We found that the mRNA expression of SRSF7 was significantly elevated in most of the GBM cell lines, while the protein was highly expressed in all GBM cell lines as compared with NHAs (Figure 4C and D).

Figure 4.

SRSF7 promotes proliferation and migration of GBM cells

A. Box plot comparing the expression of SRSF7 during GBM patients of different stages from CGGA dataset. P values of two-tailed Student’s t-test are indicated. B. IHC staining of SRSF7 in normal brain and glioma specimens. Scale bar, 20 μm. C. Bar plot comparing the relative mRNA expression levels of SRSF7 in 11 GBM cell lines as well as NHAs. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 2). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ns, no significant difference. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test. D. Western blot comparing the protein levels of SRSF7 in 11 GBM cell lines as well as NHAs. E. Western blot showing efficient overexpression of SRSF7 in U87MG and LN229 cells. F. Representative images of transwell migration assay in U87MG and LN229 cells overexpressing SRSF7. Scar bar, 50 μm. G. and H. The cell viability of SRSF7-knockdown and control U87MG (G) and LN229 (H) cells measured by MTT assay at indicated time points. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). ***, P < 0.001. Two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test. I. Representative bioluminescence images of mice bearing the intracranial glioma xenograft formed by U87MG cells transduced with shCtrl and shSRSF7, respectively. J. Line graph showing the normalized luminescence of intracranial glioma xenograft tumors formed by U87MG cells transduced with shCtrl and shSRSF7, respectively. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 6). ***, P < 0.001. Student’s two-tailed t-test. K. Representative images of H&E staining of glioma tissue sections from indicated mice. Scale bar, 2 mm. IHC, immunohistochemistry; NHA, normal human astrocyte; WHO, world health organization; MTT, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazole-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide; shCtrl, control shRNA; shSRSF7, SRSF7 shRNA; H&E staining, hematoxylin-eosin staining.

Because the genes with SRSF7 directly regulated m6A peaks were enriched in cell proliferation- and migration-related GO terms (Figure 3C), we separately overexpressed and knocked down SRSF7 in U87MG cells and LN229 cells, and then performed EdU staining, colony formation, and transwell assays to test the effects of SRSF7 on cell proliferation and migration. We found that overexpression of SRSF7 prompted the cell proliferation and migration of these two cell lines (Figure 4E and F, Figure S5A). Consistently, depletion of SRSF7 significantly impaired the proliferation and migration in U87MG and LN229 cell lines (Figure 4G and H, Figure S5B–D), and overexpression of SRSF7 can rescue the inhibition of proliferation and migration caused by SRSF7 knockdown (Figure S5E–G), which are similar as the effects of METTL3 knockdown in the same cell lines [48], [49]. Although METTL3 has been reported to regulate the stemness of GBM cells [48], [49], [50], [51], the genes with SRSF7 directly regulated m6A peaks have no enrichment of stemness-related terms (Figure 3C). Here, we found that neither knockdown or overexpression of SRSF7 could affect the neurosphere formation in U87MG cells (Figure S5H), which suggesting that SRSF7 plays more specific roles in GBM than METTL3 through specific regulation of m6A. To investigate the oncogenic role of SRSF7 in GBM cells in vivo, we utilized an intracranial xenograft tumor model, in which we transplanted SRSF7-knockdown as well as control U87MG stable cell lines into the nude mice. Consistent with the in vitro findings, SRSF7 knockdown significantly inhibited the growth of glioma xenografts (Figure 4I–K). We further confirmed that SRSF7 cannot regulate the gene or protein expression of the core methyltransferase complex (Figure 5A, Figure S6A–E), and METTL3 or WTAP cannot regulate the expression of SRSF7 either in U87MG or LN229 cells (Figure S6F and G). In addition, SRSF7 knockdown did not change the nuclear speckle localization of METTL3, METTL14, or WTAP (Figure S6H–J). The afromentioned results indicate that SRSF7 promotes the proliferation and migration, which are usually related to oncogenic roles, of GBM cells.

Figure 5.

SRSF7 promotes the proliferation and migration of GBM cells partially dependent on METTL3

A. Western blot showing the protein levels of SRSF7 and METTL3 in SRSF7-overexpressed U87MG and LN229 cells transfected without or with si-METTL3-1 as indicated. B. and C. Representative images (B) and bar plot (C) comparing the number of migrated cells in transwell migration assay in SRSF7-overexpressed U87MG and LN229 cells transfected without or with si-METTL3-1 as indicated. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 5). ***, P < 0.001; ns, no significant difference. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Scar bars, 50 μm. D. and E. Representative images of EdU staining in SRSF7-overexpressed U87MG (D) and LN229 (E) cells transfected without or with si-METTL3-1 as indicated. Scar bar, 50 μm. F. Bar plot comparing the EdU positive rate of EdU staining in SRSF7-overexpressed U87MG and LN229 cells transfected without or with si-METTL3-1 as indicated. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 5). *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001; ns, no significant difference. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. EdU, 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine.

It has been reported that METTL3 plays oncogenic roles in GBM [52], [53], [54], [55], we were therefore interested in whether SRSF7 plays oncogenic roles through specifically guiding METTL3 to oncogenic genes. We found that METTL3 knockdown largely, although not completely, disrupted the effects of SRSF7 overexpression on promoting the migration (Figure 5A–C) and proliferation (Figure 5D–F) of U87MG and LN229 cells, indicating that SRSF7 regulates migration and proliferation partially dependent on METTL3. The aforementioned results are consistent with our model that SRSF7 specifically guides METTL3 to the specific oncogenes and METTL3 takes in charge to install the m6A on these RNAs.

SRSF7 promotes the proliferation and migration of GBM cells partially through the m6A on PBK mRNA

We were then interested in the downstream targets of SRSF7 that mediated the proliferation and migration changes of GBM cells via m6A. Out of the 760 genes with SRSF7 directly regulated m6A peaks, PBK is the most significantly down-regulated gene upon SRSF7 knockdown. Meanwhile, as shown in Figure 3D, F, and G, we have confirmed that SRSF7 knockdown significantly reduced the m6A levels of two m6A sites on PBK (A1041 and A1071). PBK is also a serine/threonine protein kinase which is aberrantly overexpressed in various cancers and plays important roles in promoting the proliferation and migration of multiple cancers including glioma [56], [57], [58], [59], [60]. Based on the CGGA dataset, PBK is significantly highly expressed in WHO IV of glioma patients as compared with WHO II and WHO III, and the highly expression of PBK is significantly associated with poor prognosis in GBM (Figure S7A and B). Furthermore, the gene expression of PBK is positively correlated with SRSF7 and METTL3 based on CGGA dataset (Figure 6A, Figure S7C), suggesting a regulatory role between them. We found that overexpression of PBK could partially rescue the SRSF7-knockdown induced inhibition of proliferation and migration of U87MG and LN229 cells (Figure 6B and C, Figure S7D and E), indicating that PBK is an important downstream target of SRSF7 and partially mediates the effects of SRSF7 on promoting the proliferation and migration of GBM cellsFigure S7. We were therefore interested in whether and how the expression of PBK was regulated by SRSF7.

Figure 6.

SRSF7 promotes the proliferation and migration of GBM cells partially through the m6A on PBK mRNA

A. Scatter plot showing the correlation between SRSF7 and PBK gene expression across GBM patients from CGGA dataset. The P value and correlation coefficient are indicated. B. and C. Representative images (B) and bar plot (C) comparing the number of migrated cells in transwell migration assay in U87MG and LN229 cells upon SRSF7 knockdown and rescue by co-transducing FL WT PBK CDS region. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 5). **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Scar bar, 50 μm. D. Bar plot showing the relative mRNA levels of SRSF7 and PBK in U87MG cells transfected with scramble (si-NC) and three different siRNAs of SRSF7 (si-SRSF7-1–3), respectively. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Student’s two-tailed t-test. E. Western bolt comparing the protein levels of SRSF7 and PBK in U87MG cells transfected with scramble (si-NC) and three different siRNAs of SRSF7 (si-SRSF7-1–3), respectively. F. Bar plot showing the relative mRNA levels of PBK in SRSF7-overexpressed U87MG cells transfected without or with si-METTL3-1 as indicated. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). ***, P < 0.001; ns, no significant difference. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. G. Relative mRNA levels of PBK after ActD treatment at indicated time points in U87MG cells transfected with scramble (si-NC) and siRNA of SRSF7 (si-SRSF7-1), respectively. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. H. Schematic diagram showing the mutation of the two m6A sites in the PBK CDS region. I. Relative mRNA levels of PBK in U87MG cells transfected with FL WT or Mut PBK CDS region for 48 h. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). **, P < 0.01. Student’s two-tailed t-test. J. Relative mRNA levels of PBK after ActD treatment at indicated time points in U87MG cells transfected with FL WT and Mut PBK CDS regions, respectively. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. K. Relative mRNA levels of PBK after ActD treatment at indicated time points in U87MG cells transfected with scramble (si-NC) and siRNA of IGF2BP2 (si-IGF2BP2-2), respectively. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. L. Relative mRNA levels of PBK after ActD treatment at indicated time points in WT PBK or Mut PBK overexpressed U87MG cells transfected with scramble (si-NC) and siRNA of IGF2BP2 (si-IGF2BP2-2), respectively. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). ***, P < 0.001. Two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test. ActD, actinomycin D; WT, wild-type; Mut, mutant.

First, we tested whether SRSF7 played a regulator role on PBK through regulating its m6A. We found that SRSF7 knockdown significantly decreased the mRNA and protein expression of PBK in U87MG cells (Figure 6D and E). Overexpression of SRSF7 significantly up-regulated the gene expression of PBK, and METTL3 knockdown largely disrupted the effect of SRSF7 overexpression on the expression of PBK in U87MG cells (Figure 6F, Figure S7F and G), indicating that SRSF7 regulates PBK depends on METTL3.

We then asked how the m6A of PBK affects its expression. We found that SRSF7 knockdown also significantly promoted the degradation of PBK mRNA (Figure 6G), suggesting that SRSF7 increases PBK gene expression through promoting the stability of PBK mRNA. To further confirm that this regulation of mRNA stability depends on the m6A of PBK, we introduced two synonymous A-to-G mutations to disrupt the two m6A sites on PBK (Figure 6H). We found that the overexpressed mutant PBK exhibited significantly lower expression and lower stability of PBK mRNA than the overexpressed wild-type PBK (Figure 6I and J), suggesting that the modification of the two m6A sites on PBK is essential for the stability of PBK mRNA. Because m6A readers IGF2BP1–3 have been reported to promote the stabilities of mRNAs and play oncogenic roles in multiple cancers [31]. We then tested whether IGF2BP2, a gene significantly up-regulated in GBM, could affect the mRNA stability of PBK through binding the m6A sites. We found that knockdown of IGF2BP2 decreased the expression and stability of endogenous PBK mRNA (Figure 6K, Figure S7H), which is consistent with the finding that the gene expression of IGF2BP2 is positively correlated with PBK based on CGGA dataset (Figure S7I). Knockdown of IGF2BP2 could also significantly decrease the stability of the exogenously overexpressed wild-type PBK other than mutant PBK with the two m6A sites disrupted (Figure 6L), suggesting that the regulatory role of IGF2BP2 on the stability of PBK depends on the two m6A sites.

SRSF7 regulates m6A independent of alternative splicing and APA

Since SRSF7 was previously recognized as a splicing factor [2], [3], [4], to test whether SRSF7 can regulate alternative splicing in U87MG cells, we analyzed the differential alternative splicing of input RNAs between SRSF7-knockdown and control using rMATS [61]. We found 1344 differentially spliced events, including 734 skipped exons (SEs), 222 retained introns (RIs), 129 alternative spliced 5′ splice sites (A5SSs), 173 alternative spliced 3′ splice sites (A3SSs), and 86 mutually exclusive exons (MXEs). Of note, none of PBK, MCM4, or ROBO1 has alternative splicing change upon SRSF7 knockdown. We then used rMAPS2 [62] to study the enrichment of SRSF7 iCLIP-seq peaks near the splice sites of differentially spliced SE events, which are the most abundant type for reliable analyses. We found that the iCLIP-seq targets of SRSF7 were significantly enriched in the alternative exons of the differentially spliced evens, suggesting that SRSF7 binding directs the splicing changes (Figure 7A). GO analysis revealed that the genes with significant splicing changes were also enriched in functional terms “cell-cell adhesion” and “cell cycle” (Figure 7B), suggesting that SRSF7 can also regulate cell proliferation and migration through alternative splicing. For the 760 genes with SRSF7 directly regulated m6A peaks, only 102 (13.4%) of them had significant splicing changes upon SRSF7 knockdown (Figure 7C), which represented a non-significant overlap that could easily occur by random chance (P = 0.3, two-tailed Chi-square test). For the 129 m6A peaks in the 102 genes, only 36 peaks in 28 genes were localized within the local regions of differentially splicing events spanning between upstream exons to downstream exons, of which only 7 m6A peaks were located within the alternative exons or regions. The aforementioned results indicate that SRSF7 regulates m6A and alternative splicing independently through distinct binding sites, consistent with our observation that only a part of SRSF7 proteins colocalize with METTL3 and only a part of SRSF7-binding sites can regulate m6A.

Figure 7.

SRSF7 regulates m6A independent of alternative splicing andAPA

A. rMAPS2-generated metagene plot showing the enrichment of SRSF7 iCLIP-seq peaks at the regions around corresponding splice sites of the differentially spliced SE events upon SRSF7 knockdown. The green box represents the SE. B. GO enrichment of differentially spliced genes (all types) upon SRSF7 knockdown. C. Venn diagram showing the overlap between differentially spliced genes (all types) and genes with SRSF7 directly regulated m6A peaks. D. Scatter plot comparing the PDUI between control and SRSF7-knockdown U87MG cells. APA, alternative polyadenylation; SE, skipped exon; PDUI, percentage of distal poly(A) site usage index.

Since SRSF7 was also reported to regulate APA of RNAs [5], we also analyzed the differential APAs of input RNAs between SRSF7-knockdown and control U87MG cells using DaPars [63]. We found that only 14 APA events were significantly changed (Figure 7D), and none of the SRSF7 directly regulated m6A peaks was located within the 14 APA regions regulated by SRSF7, suggesting noninterference between SRSF7 regulated m6A and APA.

Discussion

m6A has been reported to play important roles in diverse systems through different targets. There are widespread m6A sites on most of the genes with diverse functions. It is very important for cells to dynamically coordinate the methylation of different genes to fulfil specific functions. In this study, we found that SRSF7 specifically regulates the m6A on genes involved in cell proliferation and migration, which demonstrates an important role of RBP-mediated specific regulation of m6A in co-regulating and coordinating a batch of related m6A sites in order to modulate the specific functions in cells. These diverse specific m6A regulators provide a versatile toolkit for cells to deal with various inner and outer stimulates. On the other hand, widespread involvement of RBPs in regulating m6A suggests that the m6A signaling pathways are deeply involved in the regulatory network of genes. Therefore, other signaling or regulatory pathways can modulate the m6A through regulating the RBPs in order to fulfil the downstream functions. It is very possible that more and more important functional roles of RBP-mediated specific regulation of m6A will be revealed in the future.

SRSF7 is an adaptor of NXF1, which exports mature RNAs out of nucleus, and plays important roles in coupling RNA alternative splicing and APA to mRNA export [5]. Here, we reveals a novel role for SRSF7 as a regulator of m6A methylation via recruiting METTL3. It is very possible that SRSF7 may also couple m6A methylation to mRNA export, and in this way the specific RNAs must be methylated before export. RBM15, a component of methyltransferase complex, is also an adaptor of NXF1 [64], furthering suggesting that methylation and export could be linked by a series of m6A regulators with RNA-binding specificities.

Interaction of SRSF7 with the nucleic m6A reader YTHDC1 has been reported by different groups [65], [66]. Xiao et al. found that SRSF7 does not mediate the splicing change regulated by YTHDC1 [65]. While Kasowitz et al. proposed that YTHDC1 regulates APA through recruiting SRSF7 [66]. The interactions of SRSF7 with both writers and readers of m6A suggest that SRSF7 may also work to coordinate the feedback between writing and reading of m6A. On the other hand, although the association between m6A and APA has been reported in multiple studies, the mechanism is not clear yet [34], [66], [67], [68]. Our finding that SRSF7 specifically regulates m6A may provide a novel potential mechanism that links m6A and APA by SRSF7.

We found that SRSF7 knockdown did not affect the overall peak intensities of all m6A peaks, but the overall peak intensities of SRSF7-targeted m6A peaks were significantly down-regulated upon SRSF7 knockdown. The indicated fact that SRSF7 only regulates a small portion of m6A sites may be a general feature of all specific regulators of m6A; it represents the advantage of using specific m6A regulators for cells that require precise regulation of a small portion of m6A targets. As we have previously proposed, the specific regulators of m6A may work in a similar way as splicing factors [39], [69], which usually do not affect the global splicing levels but a small portion of cell-specific splicing events [38]. On the other hand, although we have proved that only down-regulated m6A peaks upon SRSF7 knockdown are enriched for SRSF7-binding sites, we cannot rule out that there are also indirect effects of SRSF7 knockdown that up-regulates m6A, which may counteract the direct effects of SRSF7. We found significant (P < 1 × 10−4) enrichment of 8 motifs in the up-regulated m6A peaks using all m6A peaks as background (Figure S8A), suggesting that other specific regulators may recruit methyltransferase locally as indirect effects of SRSF7 knockdown.

To understand why only a small part of SRSF7-binding peaks can affect m6A methylation, we performed motif enrichment analysis for the SRSF7 iCLIP-seq peaks that overlapped with the 911 SRSF7 directly regulated m6A peaks using all SRSF7 iCLIP-seq peaks as background. As shown in Figure S8B, there are 10 motifs significantly (P < 1 × 10−4) enriched in the SRSF7 iCLIP-seq peaks that affect m6A. The most significantly enriched motifs are m6A motifs, suggesting that the existence of m6A motif near SRSF7-binding sites is necessary for SRSF7 to promote the m6A methylation. This is consistent with our finding that tethering SRSF7 promotes the m6A methylation of a nearby m6A motif but not the disruptive m6A motif with mutation right beside the m6A site (Figure 2K). The enrichment of non-m6A motifs suggests that the regulatory role of SRSF7 on m6A may be modulated by other factors colocalized with SRSF7 (Figure S8B). On the other hand, it has been reported that protein modifications of SRSF7 are important for SRSF7 to play different roles on RNA metabolisms. For example, phosphorylated SRSF7 affects RNA splicing, while dephosphorylated SRSF7 promotes nuclear exportation of RNAs [3]. In this study, we found that SRSF7 regulates alternative splicing events and APA events occurring independently with m6A peaks (Figure 7A–D), suggesting that there is also a comparable fraction of SRSF7-binding sites required for proper alternative splicing and APA other than m6A methylation in GBM cells, and probably more sites take charge for nuclear exportation of RNAs. In addition, not all RBP-binding sites reported by CLIP-seq are functional because the binding may not be strong enough. Considering that there are also a small portion of SRSF7-binding sites that can affect alternative splicing, the number of m6A-regulating SRSF7-binding sites looks reasonable for specific regulators that do not affects the nuclear speckle localization of methyltransferases (Figure S6H and I).

m6A has been reported to play important roles in cancer development [52], [53], [54], [55]. Global disruption of m6A by METTL3 depletion has been found to affect tumor growth, invasion, migration, metastasis, chemoresistance, and so on, in a variety of cancers via regulating the m6A of diverse downstream genes [16], [18], [70]. GBM is the most prevalent and malignant primary brain tumor, and characterized by rapid tumor growth, highly diffuse infiltration, and chemoresistance, as well as poor prognosis, with the median survival of GBM patients less than 15 months after diagnosis [71]. Cui et al. reported that METTL3 functions as a tumor suppressor to inhibit the growth and self-renewal of GBM stem cells [51]. Consistently, Zhang et al. reported that demethylase ALKBH5 is essential for GBM stem cell self-renewal and proliferation [50]. Based on different GBM cell lines used by Cui et al. and Zhang et al., another two groups reported that METTL3 is highly expressed in GBM cells and plays oncogenic roles in promoting the growth, migration, invasion, and radiotherapy resistance in GBM cells [48], [49]. These diverse and somewhat conflicting roles of m6A in GBM are mediated by different m6A targets, suggesting that the roles of m6A in GBM depend on the contexts and specific downstream m6A targets. Since different m6A sites may direct different roles of m6A in GBM, targeting more specific m6A sites may be a promising direction in GBM therapy. It is possible that the abnormal expression of m6A trans-regulators, which guide the deposition of METTL3 on highly specific downstream targets, causes dysregulation of more specific m6A sites with converged functions in GBM. On the other hand, the gene expression levels of SRSF7 and METTL3 are positively correlated in majority of cancer types of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (Figure S9), and both SRSF7 and PBK show significantly higher gene expression in multiple cancer types (Figures S10 and S11), suggesting that the regulatory role of SRSF7 on m6A may also contribute the tumorigenicities of other cancers. Elucidating the m6A regulators that underlie this process may provide diverse drug targets with much fewer side effects for a variety of cancers.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and reagents

HEK293T cells, HNAs (ScienCell), and glioma cell lines, including U87MG, LN229, A172, LN18, LN428, LN443, SNB19, T98G, U118MG, U251, and U138MG, were cultured in Gibco dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. All cells used in this study were confirmed mycoplasma-free.

Tissue specimen collection

Both paraffin-embedded normal brain and glioma specimens were collected from glioma patients diagnosed from 2001 to 2006 at the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China.

Construction of plasmids, siRNAs, and stable cell lines

For overexpression, the FL CDS region of SRSF7 was subcloned into the pSin-EF2 lentiviral system. For gene silencing, short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) oligos were constructed into pLKO.1 vector. The pSin-EF2-SRSF7 and pLKO.1-shSRSF7#1/2 plasmids were transfected into HEK293T cells with packing plasmids pMD2.G and psPAX2 to produce lentiviruses. Glioma cell lines were separately infected with these lentiviruses for 48 h, and later treated with puromycin for 7 days at a concentration of 0.5 μg/ml to construct stable cell lines. In addition, for the plasmids used in Co-IP, the Flag-tagged FL CDS regions of SRSF7, METTL3, and WTAP were subcloned into pcDNA3.1 vector, respectively, and then were transfected into U87MG cells with Lipofectamine 3000 (Catalog No. L3000075, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). For rescue assays, the FL CDS region of SRSF7 with synonymous point mutations (by mutating AGAACTGTATGGATTGCGAGA to AGAACCGTGTGGATCGCGCGC) was inserted into pLVX-IRES-neo plasmid to avoid being targeting by shRNAs of SRSF7. The PBK overexpression plasmid was constructed by inserting the FL CDS region of the major isoform of PBK (RefSeq ID: NM_018492) into pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-Puro vector. The two synonymous point mutations, which do not change amino acids, were introduced in to PBK at m6A sites 1041 and 1071 by mutating A to G.

Moreover, three SRSF7 siRNAs, two METTL3 siRNAs, two WTAP siRNAs, and two IGF2BP2 siRNAs were purchased from RiboBio, China. All the sequences of siRNA oligos, PCR primers, and shRNA oligos are listed in Table S3.

Co-IP and Western blot

Cells were lysed with 1× E1A lysis buffer [250 mM NaCl, 50 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N-2-ethane sulfonic acid (HEPES), 0.1% NP-40, 5 mM EDTA, pH 7.5] supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Catalog No. P8340, Sigma, Darmstadt, Germany). The lysate was sonicated on ice and centrifuged at 4 °C for 15 min, and then immunoprecipitated with Anti-Flag beads (Catalog No. M8823, Sigma, Darmstadt, Germany) overnight. The immunoprecipitates were washed five times with 1× E1A lysis buffer and samples were boiled with 2× sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) loading buffer at 100 °C for 10 min and ready for Western blot.

Proteins were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred onto hydrophilic polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes, blocked with 5% nonfat milk, and then probed with the following antibodies: anti-METTL3 (1:1000; Catalog No. 15073-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), anti-METTL14 (1:1000; Catalog No. HPA038002, Sigma), anti-WTAP (1:1000; Catalog No. ab195380, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-SRSF7 (1:1000; Catalog No. 11044-1-AP, Proteintech), anti-PBK (1:1000; Catalog No. 16110-1-AP, Proteintech), anti-α-tubulin (1:1000; Catalog No. 66031, Proteintech), and anti-Flag (1:1000; Catalog No. F3615, Sigma).

3D-SIM

For protein colocalization between SRSF7 and the methyltransferase complex, 1.5 × 103 of SRSF7 (Flag-tagged)-overexpressed U87MG cels were seeded into a chambered cover glass (Lab-Tek; Catalog No. 155411, ThermoFisher Scientific), and the immunofluorescence staining was performed with Immunofluorescence Application Solutions Kit (Catalog No. 12727, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde the next day, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 and blocked with Immunofluorescence Blocking Buffer for 1 h, and then incubated with primary antibodies [anti-METTL3 (1:1000; Catalog No. ab195352, Abcam), anti-METTL14 (1:200; Catalog No. HPA038002, Sigma), anti-WTAP (1:500; Catalog No. ab195380, Abcam), and anti-Flag (1:200; Catalog No. F3165, Sigma)] at 4 °C overnight. The samples were washed three times with 1× Wash Buffer the next day and probed with Alexa 488- and 647- conjugated secondary antibodies (ThermoFisher Scientific). The images were taken by using 100× oil-immersion objective of A1R N-SIM N-STORM microscope (Nikon). All SIM images were cropped and processed with network and information systems (NIS) Elements software.

For nuclear speckle localization of methyltransferases, the U87MG cells were transfected with SRSF7 siRNA and negative control siRNA for 48 h, respectively, and the immunofluorescence staining was performed as described above, and incubated with primary antibodies [anti-METTL3 (1:1000; Catalog No. ab195352, Abcam), anti-METTL14 (1:200; Catalog No. HPA038002, Sigma), anti-WTAP (1:500; Cata-log No. ab195380, Abcam), and anti-SC35 (1:200; Catalog No. ab11826, Abcam)] at 4 °C overnight.

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Catalog No. 15596018, ThermoFisher Scientific). 1 μg RNA was reverse transcribed using GoScript Reverse Transcription Mix (Catalog No. A2790, Promega, Fitchburg, WI) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. qRT-PCR was performed using ChamQ SYBR qPCR master Mix (Catalog No. Q311-02, Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Primers used in the qRT-PCR are listed in Table S3.

m6A-seq

Low input m6A-seq was performed by using a protocol reported by Zeng et al. [72] with some modifications. Briefly, total RNA was isolated from control U87MG cells and U87MG cells transfected with si-SRSF7-1 for 48 h. A total of 8–10 μg total RNA was fragmented using the 10× RNA Fragmentation Buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM ZnCl2). The fragmented RNA was immunoprecipitated with 5 μg anti-m6A antibody (Catalog No. 202003, Synaptic Systems, Goettingen, Germany), 30 μl protein-A/G magnetic beads (Catalog No. 10002D/10004D, ThermoFisher Scientific), 200 U RNase inhibitor (Catalog No. N2611, Promega) in 500 μl IP buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 0.1% IGEPAL CA-630 in nuclease free H2O) at 4 °C for 6 h. The samples were then washed twice using IP buffer and eluted by competition with m6A sodium salt (Catalog No. M2780, Sigma). For high-throughput sequencing, both input and IP samples were used for library construction with the SMARTer Stranded Total RNA-seq Kit v2 (Catalog No. 634413, Takara, Mountain View, CA), and sequenced by Illumina HiSeq X Ten to produce 150-bp paired-end reads.

iCLIP-seq

iCLIP was performed based on a protocol described by Yao et al. [73] with minor modifications. Briefly, U87MG cells were UV-crosslinked with 400 mJ/cm2 at 254 nm and lysed with 500 μl cell lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate), followed by immunoprecipitation with 10 μg anti-SRSF7 antibody (Catalog No. RN079PW, MBL, Tokyo, Japan) and 100 μl protein A beads (Catalog No. 10002D, ThermoFisher Scientific) at 4 °C overnight and washing as described. After dephosphorylation of the 5′ ends of RNAs, linker ligation, RNA 5′ end labeling, SDS-PAGE, and membrane transfer, the RNA was harvested and reverse transcribed by Superscript III (Catalog No. 18080044, ThermoFisher Scientific). The cDNA libraries were generated as protocol described and sequenced by Illumina NovaSeq 6000 to produce 50-bp single-end reads.

Validation of differentially methylated m6A sites

We used SELECT method to validate the differentially methylated m6A sites according to the described protocol [45]. Briefly, total RNA was mixed with 40 nM up/down primer and 5 μM dNTP in 17 μl 1× CutSmart buffer (Catalog No. B7204S, NEB, Ipswich, MA). The mixture was annealed at a temperature gradient: 90 °C, 1 min; 80 °C, 1 min; 70 °C, 1 min; 60 °C, 1 min; 50 °C, 1 min; and 40 °C, 6 min. Then 0.5 U SplintR ligase (Catalog No. M0375S, NEB), 0.01 U Bst 2.0 DNA polymerase (Catalog No. M0537S, NEB), and 10 nM ATP (Catalog No. P0756L, NEB) was added to a final volume of 20 μl and incubated at 40 °C for 20 min, denatured at 80 °C for 20 min, followed by qPCR. The cycle threshold (Ct) values of SELECT samples at indicated m6A sites were normalized to the Ct values of corresponding non-modification control sites. Primers used in the SELECT assay are listed in Table S3.

Tethering assay

The FL CDS regions of SRSF7 and METTL3 fused with a lambda peptide sequence were cloned into pcDNA3.1, the plasmid with only a lambda peptide sequence was used as negative control. The reporter plasmid (pmirGLO-dual luciferase-5BoxB) and the effector plasmids (λ, SRSF7-λ, and METTL3-λ) was transfected in U87MG cells at the ratio 1:9. The transfected cells were harvested at 24 h after transfection, and the total RNA was extracted with Trizol reagent (Catalog No. 15596018, ThermoFisher Scientific) and subjected to SELCET analysis [45]. Primers designed for plasmid construction and SELECT are listed in Table S3.

RIP-qPCR analysis

Cells were harvested and lysed in NP-40 lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 0.5% NP-40), and then cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with 10 μg anti-METTL3 (Catalog No. 15073-1-AP, Proteintech), or anti-METTL14 (Catalog No. 26158-1-AP, Proteintech), or anti-WTAP (Catalog No. ab195380, Abcam), and 100 μl protein G beads (Catalog No. 10004D, ThermoFisher Scientific) at 4 °C overnight, followed by DNase I treatment and proteinase K treatment. The bound RNAs were extracted by Trizol reagent, reverse transcribed into cDNAs, and subjected to qPCR analysis.

Cell proliferation assay, colony formation assay, migration assay, and sphere formation assay

For cell growth curve, 1 × 103 cells were seeded into 96-well plates and stained with MTT (Catalog No. M2003, Sigma-Aldrich) dye, and measured the absorbance at 570 nm. Colony formation assays were performed by seeding cells (1 × 103) into 12-well plates, cultured for 7 days, and then fixed with methanol and stained with crystal violet.

For EdU assays, 2 × 104 cells were seeded into 48-well plates, and EdU assays were performed using the EdU Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (Catalog No. C10310-1, RiboBio, Guangzhou, China). Cell migration assays were performed by seeding 2 × 104 cells into 24-well transwell polycarbonate membrane cell culture inserts and stained with crystal violet.

For sphere formation assays, 3 × 103 cells were seeded into Ultra-Low Attachment Multiple Well Plate, and cultured in the stem cell culture condition for 7 days.

Intracranial xenograft

Five-week-old female BALB/c nude mice were obtained from Beijing Vital River (Beijing, China) and divided into two groups (SRSF7-knockdown and control, n = 6 per group). Each mouse was injected with 5 × 105 U87MG cells which express luciferase in the right cerebrum. Tumor growth was monitored by Bioluminescent imaging every week.

RNA stability assay

Cells were treated with 5 μg/ml actinomycin D (Catalog No. A9415, Sigma) and collected at 0 h, 3 h, 6 h, and 9 h after treatment. The total RNA was isolated, reverse transcribed into cDNA, and subjected to qPCR analysis.

m6A-seq data analysis

The first end of the raw paired-end reads of the m6A-seq was trimmed to 50 bp from the 3′ end for m6A peak calling and downstream analyses. We mapped the reads to hg19 human genome using HISTA2 (v2.1.0) [74]. The m6A peaks were identified according to the methods as described in our previous studies [15], [39], which was modified from the method published by Dominissini and his colleagues [12]. We created 100-bp sliding windows with 50-bp overlap along the longest isoforms of each Ensembl annotated gene and calculated the reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (RPKM) for each window for IP and input, respectively. For each window, the ratio of RPKM + 1 between IP and input was calculated as the intensity. The winscore of each window was then calculated as the ratio of intensities between this window and the median of all windows in the same gene. Windows with RPKM > 10 in the IP and winscore (enrichment score) > 2 were defined as the enriched windows in each sample. The m6A peaks were defined as the enriched windows with winscores greater than neighboring windows. The overlapping or just neighboring peaks of the two biological replicates were merged into larger windows, and the 100-bp regions in the middle of the merged peaks were considered as the common peaks, which were further filtered by requiring winscore > 2 in both replicates. The distributions of m6A peaks along 30 bins of mRNA were calculated as we have previously described [15].

The m6A ratio, which quantifies m6A peaks, of each m6A peak was calculated as the ratio of peak RPKM between IP and input. To calculate the fold change of m6A ratios upon SRSF7 knockdown, we first took the union of the m6A peaks of all samples. The union peaks of two replicates were merged, centralized, and filtered to obtain a set of 100-bp peak regions in the same way as above described for obtaining common peaks. To avoid using the unreliable m6A ratios due to tiny denominators, we filtered out the peaks with input window RPKM < 5 at least one sample or m6A ratio < 0.1 in any control samples. Then the m6A peaks with fold change of m6A ratios upon SRSF7 knockdown > 1.5 or < 2/3 were determined as the up-regulated or down-regulated m6A peaks. The data were visualized using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) tool [75], the biological replicates were merged, and the average read coverages were used for visualization. StringTie (v1.3.4d) [76] was used to calculate the transcripts per million (TPMs) of Ensembl annotated genes using the input libraries. We filtered out the genes with mean TPM < 1 in control samples to avoid using unreliable fold change of TPMs due to tiny denominators. Differentially expressed genes were determined using DESeq2 [77] according to the read counts of genes calculated by HTSeq [78]. The genes with false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 and mean counts per million (CPM) > 100 were determined as the differentially expressed genes. GO analysis was performed using DAVID [79] with all expressed genes (TPM > 1) as background. The GSEA was performed using GSEA (v2.2.2.0) [80] based on the predefined gene sets from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB v5.0) [80].

Analysis of the clinical data of glioma patients

The gene expression, mutation, and clinical data of glioma patients were downloaded from CGGA database (http://www.cgga.org.cn/) [40]. We used the Cox Regression to examine the correlations between gene expression indexes of the cancer module and patient survival in each cancer type. The gene expression data of all cancer types were downloaded from TCGA (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/).

iCLIP-seq data analysis

We used the CTK to call the peaks from the iCLIP-seq data according to the described data processing procedure of iCLIP-seq [42]. HOMER software [81] was used for motif enrichment analysis with randomly permutated sequences as the background. The overlapping peaks between the peaks of m6A-seq and iCLIP-seq were determined as the peaks with distance < 100 bp using BEDTools [82].

Alternative splicing and APA analyses

We used rMATS [61] to perform the differential alternative splicing analysis using the input RNAs of m6A-seq with FDR < 0.05 as the threshold of significance. The binding enrichment of SRSF7 around splicing events was analyzed using rMAPS2. To test whether the genes with alternative splicing and the genes with SRSF7 directly regulated m6A peaks are significantly overlapped, we only considered all m6A modified genes with rMATS-detected alternative splicing in the Chi-square test. Differential APA analysis was performed using DaPars [63] with FDR < 0.1 as the threshold of significance.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons between two groups were performed using Student’s two-tailed t-test. Comparisons during more than two groups are performed using ANOVA. Data represent mean ± SEM; P value or adjusted P value for ANOVA less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Survival curves were plotted by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. The statistics of bioinformatic analyses were all described along with the results or figures.

Ethical statement

Written informed consents and approvals for all tissue specimens were obtained from the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University (Approval No. [2020]322), and all animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou, China (Approval No. L102012018010T).

Data availability

The raw sequencing reads of m6A-seq and iCLIP-seq have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive for Human [83] at the National Genomics Data Center, Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences / China National Center for Bioinformation (GSA-Human: HRA001166), and are publicly accessible at https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yixian Cun: Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Sanqi An: Software, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Haiqing Zheng: Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Jing Lan: Investigation. Wenfang Chen: Formal analysis. Wanjun Luo: Investigation. Chengguo Yao: Investigation. Xincheng Li: Investigation. Xiang Huang: Resources. Xiang Sun: Resources, Funding acquisition. Zehong Wu: Formal analysis. Yameng Hu: Resources. Ziwen Li: Resources. Shuxia Zhang: Resources. Geyan Wu: Resources. Meisongzhu Yang: Resources. Miaoling Tang: Resources. Ruyuan Yu: Resources. Xinyi Liao: Resources. Guicheng Gao: Resources. Wei Zhao: Resources. Jinkai Wang: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Jun Li: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jianzhao Liu for providing the vectors of tethering assay. This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2018YFA0107200) to JW, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81830082, 82030078, and 81621004 to JL; Grant Nos. 31771446 and 31970594 to JW; Grant No. 32100452 to XS).

Handled by Chengqi Yi

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences / China National Center for Bioinformation and Genetics Society of China.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gpb.2021.11.001.

Contributor Information

Jinkai Wang, Email: wangjk@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Jun Li, Email: lijun37@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Supplementary Figure S1.

Interaction between SRSF7 and methyltransferase complex A. Western blots showing Flag-tagged SRSF7 interacts with endogenous METTL3, METTL14, and WTAP with RNase treatment in 293T cells. B. Schematic diagram of the truncated regions of SRSF7. Zn, Zinc knuckle.

Supplementary Figure S2.

SRSF7 specifically facilitates m6A methylation near its binding sites A. Enriched motifs in m6A peaks of control and SRSF7-KD U87MG cells. B. Normalized distributions of m6A peaks across 5' UTR, CDS, and 3' UTR of mRNA in U87MG cells transfected with scramble (si-NC) and siRNAs of SRSF7 (si-SRSF7) respectively. C. Box plot comparing the m6A ratios of the m6A peaks in control and SRSF7-KD U87MG cells. D. Heatmap representing the Z-score transformed m6A ratios in si-NC and si-SRSF7 in U87MG cells respectively. E. and F. GO (E) and KEGG (F) enrichment analyses of genes with down-regulated m6A peaks upon SRSF7 knockdown. G. Pie chart showing the fractions of SRSF7 iCLIP-seq peaks located in different regions of genes. H. Normalized distributions of SRSF7 iCLIP-seq peaks colocalized with m6A peaks across 5' UTR, CDS, and 3' UTR of mRNA in U87MG cells. I. Plot of cumulative fraction of log2 fold change of m6A ratios upon SRSF7 knockdown using si-SRSF7 for the m6A peaks within the orange module and all other modules respectively. P value of two-tailed Wilcoxon test is indicated. KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

Supplementary Figure S3.

SRSF7 regulates gene expression A. Heatmap representing the Z-score transformed gene expression of differentially expressed genes between control and SRSF7-KD U87MG cells. B. and C. GO enrichment analyses of genes with down-regulated (B) and up-regulated (C) gene expression upon SRSF7 knockdown. D.–F. GSEA plots for the gene expression changes due to SRSF7 knockdown in U87MG cells. ES, Enrichment score; FDR, false discovery rate.

Supplementary Figure S4.

SRSF7 directly targets and facilitates the methylation of m6A on genes involved in cell proliferation and migration A. KEGG enrichment of the corresponding genes with the overlapped m6A peaks between down-regulated m6A peaks upon SRSF7 knockdown and SRSF7 iCLIP-seq peaks. B. GO enrichment analysis of genes with SRSF7 iCLIP-seq peaks not colocalize with m6A peaks. C. Tracks displaying the read coverage of IPs and inputs of m6A-seq as well as the SRSF7 iCLIP-seq on ROBO1. The SRSF7 directly regulated m6A peak is highlighted.

Supplementary Figure S5.

SRSF7 promotes the migration and proliferation of GBM cells A. Representative images of colony formation assay in U87MG and LN229 cells overexpressing SRSF7. B. Western blot showing efficiently knockdown of SRSF7 in U87MG and LN229 cells transduced with control shRNA or SRSF7 shRNA respectively. C. Representative images of transwell migration assay in U87MG and LN229 cells transduced with control shRNA or SRSF7 shRNA respectively. Scar bars: 50 μm. D. Representative images of EdU staining assays and bar plot comparing the EdU positive rates in U87MG and LN229 cells transduced with control shRNA or SRSF7 shRNA respectively. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 5. ***, P < 0.001. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test. Scar bars: 50 μm. E. Western blot showing the protein level of SRSF7 in U87MG and LN229 cells transduced with shSRSF7 together with empty vector and SRSF7 with synonymous mutations. F. Representative images of colony formation assay in U87MG and LN229 cells with control, SRSF7 knockdown, and SRSF7 knockdown rescued by SRSF7 overexpression. G. Representative images of EdU staining assays and bar plot comparing the EdU positive rates in U87MG and LN229 cells with control, SRSF7 knockdown, and SRSF7 knockdown rescued by SRSF7 overexpressed. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 5. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Scar bars: 50 μm. H. Sphere formation results in U87MG cells upon SRSF7 depletion and overexpressed. Scar bars: 100 μm. Vec, vector.

Supplementary Figure S6.

SRSF7 promotes the proliferation and migration of GBM cells partially dependent on METTL3 A & B. Gene expression change of METTL3, METTL14, and WTAP in U87MG cells (A) and LN229 cells (B) transfected with scramble (si-NC) and siRNA of SRSF7 (si-SRSF7-1, si-SRSF7-2, and si-SRSF7-3) respectively. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3. ***, P < 0.001; ns, no significant difference. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test. C–E. Western blot showing the protein level of METTL3, METTL14, WTAP, and SRSF7 upon SRSF7 knockdown (C–D) or SRSF7 overexpression (E) in U87MG and LN229 cells. F. Western blot showing the protein level of METTL3 and SRSF7 in U87MG cells transfected with si-NC and si-METTL3. G. Western blot showing the protein level of WTAP and SRSF7 in U87MG cells transfected with si-NC and si-WTAP. H–J. 3D-SIM imaging of colocalization of METTL3 (H), METTL14 (I), and WTAP (J) with the nuclear speckle marker SC35. Scale Bar: 2 μm.

Supplementary Figure S7.