Abstract

Oral diseases, such as periodontitis, salivary gland diseases, and oral cancers, significantly challenge health conditions due to their detrimental effects on patient’s digestive functions, pronunciation, and esthetic demands. Delayed diagnosis and non-targeted treatment profoundly influence patients’ prognosis and quality of life. The exploration of innovative approaches for early detection and precise treatment represents a promising frontier in oral medicine. Exosomes, which are characterized as nanometer-sized extracellular vesicles, are secreted by virtually all types of cells. As the research continues, the complex roles of these intracellular-derived extracellular vesicles in biological processes have gradually unfolded. Exosomes have attracted attention as valuable diagnostic and therapeutic tools for their ability to transfer abundant biological cargos and their intricate involvement in multiple cellular functions. In this review, we provide an overview of the recent applications of exosomes within the field of oral diseases, focusing on inflammation-related bone diseases and oral squamous cell carcinomas. We characterize the exosome alterations and demonstrate their potential applications as biomarkers for early diagnosis, highlighting their roles as indicators in multiple oral diseases. We also summarize the promising applications of exosomes in targeted therapy and proposed future directions for the use of exosomes in clinical treatment.

Subject terms: Periodontitis, Oral cancer detection

Introduction

The oral cavity is the initial segment of the digestive system, second source of respiration, and a crucial organ for pronunciation, mastication, and facial esthetics. Poor oral health may have an impact on a person’s overall health, causing pain, discomfort, and disfigurement.1 Oral diseases, such as dental caries, periodontal diseases, and oral cancers, affect nearly 3.5 billion people, which are global burdens that cause patients suffering, especially those with a low socioeconomic status.2 To alleviate these burdens, researchers have come up with innovative methods for early diagnosis and effective treatment.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are derived from cellular membranes and released into the extracellular space; they play critical roles in intercellular communication.3 There are two main categories of EVs, including exosomes and ectosomes.4 Exosomes, which are principal constituents of EVs, are derived from the endosomal system and possess bilayer lipid encapsulation, with diameters ranging from 30 to 150 nm.5 Compared with ectosomes, which assemble cargos on the cytosolic surface and transient release in “outward budding”,6 exosomes exhibit more intricate interactions with cyto-inclusions and have garnered significant attention from biological researchers worldwide for their abundant cargos and various functions associated with physiological or pathological processes.5

The biogenesis of exosomes is tightly regulated through a complex network of processes. Upon endocytosis, the potential cargos are internalized by the cells and give rise to early-sorting endosomes (ESEs). The subsequent interactions with organelles, such as the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi apparatus, lead to the maturation of ESEs into late-sorting endosomes (LSEs). Following this, the cargos accumulate near the limiting membrane of multivesicular bodies (MVBs) and generate intraluminal vesicles (ILVs), which will eventually be released as exosomes via exocytosis.5,7,8 It should be noted that some ILVs may also undergo interactions with lysosomes or autophagosomes.5,7,8 Throughout the entire process, various regulators, such as the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT), tetraspanin CD9/CD63/CD81, and Alix/programmed cell death 6-interacting protein (PDCD6IP), are involved in the intricate mechanisms of sorting and secretion.5,7–9 Accordingly, an extensive body of research has confirmed that the final version of the exosomes contains diversified contents, including amino acids, proteins, nucleic acids, and cellular metabolites. These molecules play distinct roles in intercellular signaling transmission, immune-modulation, stromal adaptation, and multiple biological events.9

Therefore, exosomes exhibit significant potential in managing disease processes. Previous research has elucidated the close correlation between exosomes and oral diseases, including periodontal inflammation, oral squamous cell carcinomas (OSCCs), oral mucosa diseases, etc. The application of exosomes involves monitoring the progression of the diseases, early diagnosis, detection through specific manifestations in fluid, and advanced targeted therapy via precise molecule delivery. This review concludes the recent studies on the applications of exosomes in oral diseases and aims to provide a comprehensive insight into the latest developments in exosome alterations, functions, and applications in oral-related physiological and pathological conditions. The ultimate goal is to identify new opportunities for the effective utilization of exosomes in the prevention and treatment of oral diseases.

Exosomes in the progression of oral diseases

As researchers have demonstrated the intricate roles of exosomes in biological events, their distinct alterations are significant components in the pathological processes of oral diseases. At the initial stage, analyzing the exosomal information helps to improve our early awareness of oral diseases. During the development and prognosis stages, summarizing the exosome-related manifestations can enhance our comprehension of the selection and response of treatments. Therefore, exosomes serve as a crucial indicator in the diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of several oral diseases. In this part, we summarize the roles of exosomes in determining the progression of oral diseases, with a focus on periodontal diseases and oral cancers.

Periodontal and bone-related pathological status

Periodontal inflammation and bone resorption

Following exposure to risk factors (intrinsic and/or acquired), the pathological changes in periodontitis are initiated by immune-inflammatory responses, leading to the release of inflammatory molecules, such as cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). These molecules exert their effects on periodontal tissues, thereby inducing clinical manifestations.10 Osteoclasts are activated in inflammatory microenvironments and lead to the destruction of the surrounding alveolar bone. Subsequently, these irreversible destructions of periodontal structures accelerate the progression of periodontitis and lead to tooth mobility or even tooth loss, severely impacting the patients’ quality of life.11 The previous studies have demonstrated the significance of inflammatory factors in periodontitis.10 It is noteworthy that exosomes play important roles in the modulation and alteration of periodontal inflammation and bone resorption.12

Periodontal ligament stem cell (PDLSC)-derived exosomes significantly improved angiogenesis in inflammatory regions by upregulating the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) via miR-17-5p.13 Salivary exosomal miR-223-3p increased the interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-6 levels by mediating NLRP3 gene expression and pyroptosis.14 Oxidative stress is involved in periodontitis progression with abnormal reactive oxygen species (ROS). Protein arginine methyltransferase 1 (PRMT1) induced by oxidative stress inhibited exosome secretion from periodontal ligament cells (PDLCs), resulting in reduced osteogenic differentiation.15

The interactions between the host inflammatory response and microbe are also closely involved in the progression of periodontitis.10 Similar to exosomal microRNAs (miRNAs) derived from host cells, small RNAs of miRNA size (msRNAs) from pathogens (A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, and T. denticola) were detected in the bacterial outer membrane vesicles.16 P. gingivalis can also assign a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) to dendritic cells (DCs) and T cells by exosomes, and ultimately, this results in alveolar bone loss.17 Moreover, mechanical stimuli are a promoter of periodontal inflammatory and tissue/bone impairment, mainly acting on PDLCs.18 PDLCs secrete exosomal miR-9-5p when facing cyclic stretching and promote the M1 (pro-inflammatory) polarization of macrophages through the miR-9-5p/SIRT1/NF-kB pathway in murine models.19 The M1 macrophage was also induced by periodontal ligament fibroblast-derived exosomes when a compressive force was applied. The underlying mechanism was associated with the Yes-associated protein (YAP),20 which is a crucial component in the Hippo signaling pathway and performs significant roles in cellular mechanotransduction.21 In the immune-modulation of the inflammatory response, the YAP/Hippo pathway acts as a key upstream regulator.22 These studies highlight the complex interactions between exosomes and the clinical manifestations of periodontal diseases, according to which we should take more steps to attenuate the progression of periodontitis.

Orthodontic movement

Orthodontic treatment involves the complex processes of alveolar bone remodeling upon the application of mechanical forces. During movement, the expression of gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) exosomal miR-29 is significantly increased.23 Meanwhile, the PDLSC-derived exosomal miRNAs are largely altered,24,25 and the quantity of exosomal proteins annexin A3 (ANXA3) increases, which induces osteoclast differentiation by the activation of extracellular regulated protein kinase (ERK).26 When orthodontic movement stops and teeth position satisfies our needs, PDLSC-derived exosomes also contribute to teeth stabilization. For instance, Simvastatin, a bone-formation-enhancing drug, has better bioavailability in conjunction with PDLSC-derived exosomes.27

Oral squamous cell carcinomas

With increasing incidence and mortality rates, oral cancers rank as the 13th most common cancer worldwide, with an estimated 377,713 new cases and 177,757 deaths in 2020.28,29 The consumption of tobacco and areca nut significantly increases the risk of oral cancers. Specifically, oral cancers cause larger burdens in developing countries due to delayed diagnosis and limited treatment opportunities.29 Among all the types of oral cancers, OSCCs are the most common, with an estimated 40% higher incidence rate in 2040.30 Summarizing the alterations in the exosomes in OSCCs could enhance our understanding of malignant progression. Here, we discuss exosomal roles in malignization, angiogenesis, and tumor microenvironment (TME) modification in OSCC progression and the post-treatment response (Fig. 1).

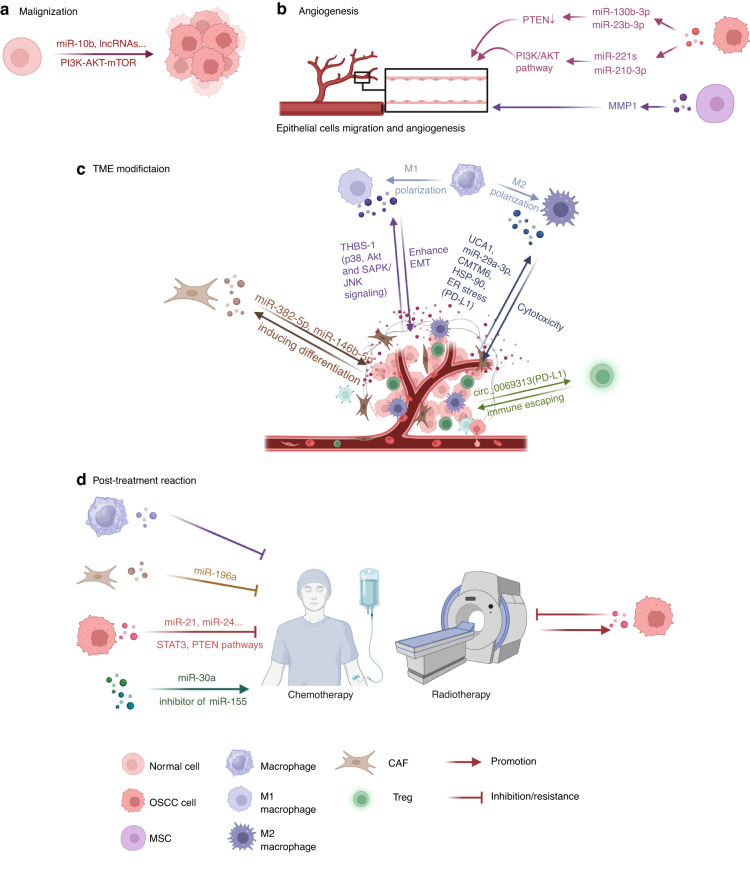

Fig. 1.

Exosomes in OSCCs. Exosomes play crucial roles in several key processes through OSCCs progression. a Addition of exosomal miR-10b and increased level of several exosomal lncRNAs (targeting PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway) lead to initiation of OSCCs. b OSCC cells derived exosomal miR-130b-3p and miR-23b-3p promoted angiogenesis through downregulating PTEN, while miR-221s and miR-210-3p activated through PI3K/AKT pathway. MSCs-derived MMP1 played the same role in angiogenesis. c During the progression of OSCCs, TME exhibits intricate interactions with tumors. Exosomes derived from OSCC cells promoted differentiation of CAFs, while CAFs secreted exosomal miR-382-5p and miR-146b-5p to enhance tumor development. In immune regulations, cancer-derived exosomal THBS-1 induced polarization of TAMs toward M1 type. Exosomal UCA1, miR-29a-3p, CMTM6, HSP-90 and PD-L1 (under ER stress) lead TAMs to M2 type. Both M1 and M2 macrophages contribute to the progression of malignancy. T cells were also modulated by cancer cells through exosomal circ_0069313, targeting PD-L1. In addition, Tregs played a crucial role in facilitating immune evasion in OSCCs. d Exosomes can regulate treatment response of OSCC to chemotherapy and radiotherapy

Malignization

According to transcriptome analysis, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC)-associated exosomes play a significant role in various processes throughout cancer development.31 As the most common malignancy types in HNSCCs, OSCCs exhibit various exosomal alterations. From the outset, the injection of OSCC-tumor-derived exosomes accelerated the malignancy progression of precancerous lesions in murine models,32 and this phenomenon was attributed to exosomal miR-10b through AKT signaling.33 The same initiation of malignancy also occurs in recurrent OSCCs with increased serum exosomal long non-coding RNA (lncRNA)-CCDC144NL-AS1 and MAGI2-AS3 via the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway34 (Fig. 1a). Upon the manifestation of these early malignancy symptoms, the subsequent progression of OSCCs ensues through diverse exosomal alterations.

Angiogenesis

Inducing the vasculature is an important hallmark of cancer,35 and the exosomes accelerate this process through several pathways (Fig. 1b). Phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten (PTEN) is a tumor-suppressing factor, and its expression is downregulated in OSCCs.36 Exosomal miR-130b-3p derived from OSCCs cells and miR-23b-3p from salivary adenoid cystic carcinomas (SACCs) cells negatively regulate PTEN expression, promoting migration and angiogenesis in HUVECs.37,38 miR-221s and miR-210-3p also regulated HUVECs angiogenesis through the PI3K/AKT pathway.39,40 Besides cancer cells, the mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in oral carcinomas can secrete angiogenesis-stimulative exosomes. OSCC–MSC-derived exosomal matrix metalloproteinases 1 (MMP1) significantly enhances the function of HUVECs.41

TME modification

In addition to tumor cells, TME exerts a dominant influence on the development of OSCCs, involving intricate interactions with exosomes (Fig. 1c). The TME is composed of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and relevant cells, including cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), endothelial cells, and immune cells.42 In OSCCs, tumor-derived exosomes induce CAF differentiation.43 In turn, the CAFs have received great attention for their significance in promoting tumor development through intracellular communications, primarily via exosome secretion.44 In OSCCs, the CAF-derived miR-382-5p45 and miR-146b-5p46 exosomes are upregulated, leading to the invasion of cancer cells and metastasis. In addition, the miR-34a-5p-devoid exosomes from CAFs promote malignancy by targeting the AXL (a component of the receptor tyrosine kinase) of cancer cells.47

By analyzing the genes related to EV formation in the HNSCCs samples and their impact on cellular behaviors, other scientists have found a significant correlation between EVs and immune modification (T/B cells, macrophage, and neutrophils) when a malignancy occurs.48 The tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) play a crucial role as immune cells within the TME. Generally, the TAMs mainly polarize into two states—the M1 and M2 subtypes.49 According to the conventional perspective, the M1 macrophages perform anti-tumor functions by direct cytotoxicity or antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC), while the M2 macrophages promote cancer progression and metastasis by secreting cytokines and related molecules, such as ILs, epithelial growth factors (EGFs), and MMPs.50 However, the involvement of M1 macrophages in the process of malignancy invasion has been recently observed, suggesting that their presence may contribute to more aggressive malignization, but not a higher survival rate.51

In OSCCs, the TAMs have complex interactions with the tumor cells. The exosomal transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) derived from HNSCCs cells can promote angiogenesis by both interacting with epithelial cells and modulating TAMs chemotaxis for pro-angiogenic functions.52 OSCC-derived exosomal thrombospondin 1 (THBS-1) activates an M1-like macrophage through p38, Akt, and SAPK/JNK signaling, which promotes cancer progression.53 M1-like TAMs enhance the OSCC epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and cancer stem cell formation through the IL-6/Jak/signal transducer and the activator of transcription 3 (Stat3)/THBS-1 axis.54

Furthermore, oral cancer cells are closely associated with the conventional oncogenic M2 macrophages through multiple pathways.50 OSCC cancer stem cell-derived exosomes polarize TAMs into M2 macrophages by the urothelial carcinoma-associated 1 (UCA1) secretion targeting LAMC2-PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. These exosomes also suppress anti-tumor immunity, including CD4+ T cells activation and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production.55 In addition, OSCC cancer cells secrete exosome-enclosed cargos, inducing M2 macrophages. MiR-29a-3p, a member of the miR-29 family that significantly increases in OSCCs,56 exerts effects on M2 polarization through the suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1)/signal transduction and the transcriptional activator (STAT) pathway.57 The CKLF-like MARVEL transmembrane domain-containing 6 (CMTM6)58 and heat shock protein-90 (HSP-90)59 are important proteinic influencers of M2 macrophage conversion, indicating novel crosstalk between cancer cells and immune-modulation. ER stress, a functional proteinaceous response that reacts to cellular events like oncogenesis, drives OSCC cells to secrete exosomal programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) and activate the M2 polarization of TAMs.60

Besides TAMs, T cells are also important immune regulators in OSCCs. T-effector (Teff) cells and T-regulatory (Treg) cells are the two main classifications of T cells.61 Teff cells primarily execute killing functions toward pathogens or, anomaly, self-antigens. Treg cells modulate over-functioning Teff cells and maintain immune homeostasis. However, in the oncogenesis process, Treg cells may lead to immune evasion.61 In OSCCs, exosomal circular RNA circ_0069313 could increase the PD-L1 expression in cancer cells with miR-325-3p sponging and interact with Treg cells. Thus, the Teff cells are suppressed, while the Treg cells are activated, resulting in the immune escaping of malignancy.62

Post-treatment reaction

The traditional non-surgical treatments for OSCCs include chemotherapy and radiotherapy.63 However, resistance and unwilling treatment responses will impact the prognosis and mortality. Therefore, it is imperative to identify precise markers that can effectively assess the efficacy of these therapies. Chemoresistance occurs in nearly all anti-tumor drugs, and the underlying mechanism can be intrinsic (gene mutations) or acquired (TME, epigenetic alteration).64 According to recent studies, the exosomes play a crucial role in chemoresistance of OSCCs through several pathways65 (Fig. 1d). Exosomal microRNAs (such as miR-21 and miR-24) derived from OSCC cell lines contribute to chemoresistance by targeting multiple signaling molecules, including STAT3 and PTEN.65,66 Macrophage-derived exosomes and CAF-derived exosomal miR-196a can also reduce drug sensitivity.67,68 In addition, the exosomes can influence chemoresistance by modulating the drug efflux, vesicular pH, anti-apoptotic signaling, DNA damage repair (DDR), as well as the EMT.65 In reverse, the delivery of exosomal miR-30a and the inhibitor of exosomal miR-155 showed the ability to enhance the sensitivity of cisplatin-resistant OSCCs,69,70 highlighting their potential role in improving cancer therapy. Cancer cells’ reactions toward radiotherapy are also associated with exosomes (Fig. 1d), mainly through modulating DDR, cell death signals, and the EMT.71 In HNSCC radiation-resistance cases, the functions of tumor-promoting exosomes are strengthened after radiation.72

Besides resistance, the profile of exosomes in OSCCs alters in response to treatment. After surgery and/or chemo-radiotherapies, monitoring immune-related exosomal proteins (such as PD-L1) could accurately indicate the treatment reaction and recurrence possibility.73,74 Melatonin, a hormone secreted by the pineal gland, plays crucial roles in multiple physiological processes.75 The recent research has highlighted its potential function in OSCC therapy as an adjuvant, owing to its ability to inhibit tumor progression by modulating key regulators, such as MMP-9, p53, and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), as well as enhancing immune functions.76,77 The expression of OSCC cell-derived exosomes (miR-21 and miR-155) undergoes alterations following melatonin application, indicating their potential for assessing the treatment response and predicting the prognosis.78

In conclusion, exosomes exhibit various characteristics during the development and prognosis of OSCCs. By improving our comprehension of these alterations, we can approach a better understanding of the enigma surrounding OSCC occurrence and conduct further investigations on therapeutic interventions.

Early diagnostic methods utilizing exosomes in oral diseases

According to the above, it is convincing that exosomes play a crucial role in the progression of oral diseases. Our particular emphasis lies in exosomal application for early diagnosis due to the potential exacerbation of patients’ suffering caused by delayed detection. In contrast to the more apparent biomarkers, such as inflammatory molecules of periodontitis and gene expression changes in OSCCs, exploring the full advantages of exosomes represents a promising avenue. Liquid biopsy is an emerging disease diagnostic method that primarily involves the isolation and evaluation of fluid entities, such as DNAs/RNAs, proteins, and extracellular vesicles in human saliva, blood, and urine.79 Compared with the other patterns of biomarkers, exosomes protect their cargos, remarkably enhancing the accuracy and practicability of detection.80 In the field of oral medicine, exosome-associated liquid biopsy has demonstrated value in the diagnosis of multiple diseases.81 The identification of novel biomarkers and reliable detective techniques are potential research prospects.

Biomarkers for periodontitis

The traditional diagnostic criteria for periodontitis primarily rely on clinical symptoms, such as the periodontal pocket depth and the pathological loss of the alveolar bone. However, the possibilities of “overdiagnosis” or “underdiagnosis” remain unsolved, as these clinical variables may fail to accurately predict the disease progression and treatment response.82 The identification of exosomal biomarkers has the potential to enhance our understanding of the intricate biological mechanisms underlying periodontitis progression and facilitate the development of advanced clinical management strategies for patients. Generally, the concentration of EVs from the GCF of periodontitis patients is evidently higher when compared to that of healthy samples.83

Nucleic acids, as prominent constituents of exosomal cargos, can provide valuable diagnostic insights. In addition to DNA/RNAs that directly encode proteins, non-coding RNAs play important roles in regulating cellular events through diverse pathways, such as gene silencing and post-translational modification.84 MiRNAs are small, non-coding RNAs that modulate mRNA expression by forming RNA-induced silencing complexes (RISCs) or directly binding to mRNAs through base pairing.85

According to Kamal et al.,86 1995 salivary exosomal miRNAs and 333 plasma exosomes were significantly altered in their periodontitis samples. Among these potential biomarkers, serum exosomal miR-let-7d, miR-126-3, miR-199a-3, and salivary exosomal miR-125a-3 were notable for distinguishing the disease status and correlation with the clinical stages.86 In addition, researchers reported that serum exosomal miR-1304-3p, miR-200c-3p, small nucleolar RNA SNORD57, SNODB1771,87 salivary exosomal miR-223-3p,14 Osx mRNA88 and GCF exosomal miR-122689 were downregulated in periodontitis. However, salivary exosomal miR-140-5p, miR-146a-5,miR-628-5p,90 miR-381-3p,91 tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α),88 and PD-1 mRNAs exhibited higher expression levels in the periodontitis samples.92 As for proteins, the levels of the tetraspanins CD9 and CD81 were decreased in the salivary exosomes of periodontitis, which is associated with an inflammatory reaction.93 The levels of immune-related proteins, such as complement components (C6, C8A, and C8B) and chemokines, were increased in the salivary exosomes of young severe periodontitis patients,94 implying that immune changes are responsible for this pathological alteration.

Biomarkers for oral cancers

Scalpel biopsies and histological examinations have long been regarded as the golden standard for malignancy research.95 However, oral cancers, particularly OSCCs, usually develop imperceptibly, with minimal clinical manifestations in the early stages. Therefore, by the time the symptoms have been identified, the malignancy may have already appeared, leading to a poor prognosis.96 In the meantime, the pursuit of non-invasive detection methods has become a prevailing trend in the medical field. These statuses emphasize the necessity for the application of exosomal biomarkers in OSCC diagnosis. Compared with the samples from healthy controls, the exosomes from OSCC patients showed an increased concentration and larger diameter, with higher CD63 and lower CD9/CD81 expression levels, revealing basic evidence for distinguishment.97 However, the most comprehensive and convincible distinctions are the cargos of the exosomes. We have summarized these biomarkers and the relevant research in Table 1.

Table 1.

Exosomal cargos as biomarkers for oral cancer diagnosis

| Tissue | Sample | Exo-biomarker | Alternation | Statistic scale | Mechanism | Other information | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tongue SCCs | Plasma | miR-19a/27b/20a/28-3p/200c/151-3p/223/20b | Upregulated | 5 patients | N/A | N/A | 98 |

| miR-370/139-5p/let-7e/30c | Downregulated | ||||||

| OSCCs | Plasma | miR-130a | Upregulated |

184 patients 196 controls |

N/A |

Associated with poor prognosis (advanced TNM stages/poorly differentiation) |

99 |

| OSCCs | Serum | miR-155/21 | Upregulated |

35 patients 11 controls |

Downregulating tumor suppressors PTEN and Bcl-6 | N/A | 100 |

| miR-126 | Downregulated | Inhibiting oncogene EGFL7 expression | Low miR-126 was associated with poor prognosis | ||||

| HNSCCs | Serum | miR-3168/125a-5p/451a/16-2-3p | Upregulated |

22 patients 10 controls (with benign neoplasm) |

N/A | N/A | 101 |

| OOCs | Saliva | miR-486-5p | Upregulated |

25 patients 25 controls |

N/A | Higher level in stage II | 105,106 |

| miR-10b-5p | Downregulated | N/A | |||||

| OSCCs | Saliva | miR-24-3p | Upregulated |

49 patients 14 controls |

Targeting circadian gene-PER1 | N/A | 102 |

| OSCCs | Saliva | miR-1307-5p | Upregulated |

12 patients 7 controls |

Suppressing onco-related genes THOP1, EHF, RNF4, GET4 and RNF114 | Associated with poor prognosis | 103 |

| OSCCs | Saliva |

miR-134/200a IL-1β and IL-8 |

Upregulated |

14 patients 23 controls |

N/A | N/A | 104 |

| OSCCs | Serum | circ_0000199 | Upregulated |

108 patients 50 controls |

Associated with miR-145-5p and miR29b-3p | Associated with poor prognosis | 110 |

| HNSCCs | Plasma | TGF-β | Upregulated |

36 patients 12 controls |

TME-dependent oncogenic role | Increasing with stages/size of tumors | 111 |

| OSCCs | Serum/saliva | Alix | Upregulated |

Serum 29 patients 21 controls Saliva 23 patients 20 controls |

N/A | Only serum exoAlix associated with stages | 112 |

| OSCCs | Serum | Combined CRP, VWF and LRG | Upregulated |

40 patients 20 controls |

N/A | Combined biomarkers show greater sensitivity and specificity than individual ones. | 113 |

| OSCCs | Serum | PF4V1, CXCL7, F13A1 and ApoA1 |

Downregulated (F13A1 upregulated) |

10 patients (no LNM) 10 patients (with LNM) 10 controls |

N/A |

PF4V-tumor differentiation level PF4V1/F13A1-positive node number ApoA1-smoking and drinking |

114 |

SCC squamous cell carcinoma, OSCC oral squamous cell carcinoma, HNSCC head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, OOC oral and oropharyngeal cancer, miR micro-RNA, IL interleukin, circRNA circular RNA, TGF-β transforming growth factor beta, Alix programmed cell death 6-interacting protein (PDCD6IP), CRP C-reactive protein, VWF von Willebrand factor, LRG leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein, PF4V1 platelet factor 4 variant, CXCL7 C-X-C motif chemokine, F13A1 coagulation factor XIII, A, ApoA1 apolipoprotein A-I, PTEN chromosome ten, PER1 Period1

In OSCCs, the altered secretion of exosomal miRNAs can signal the disease status. Based on the statistical evidence, the levels of serum/plasma exosomal miR-19a/27b/20a/28-3p/200c/151-3p/223/20b,98 miR-130a,99 miR-155, miR-21,100 miR-3168, miR-125a-5p, miR-451a, and miR-16-2-3p,101 and salivary exosomal miR-486-5p, miR-486-3p, miR-24-3p,102 miR-1307-5p,103 miR-200a, and miR-134104 were significantly elevated in the patients with OSCCs, performing potential oncogenic roles. However, the serum exosomal miR-370/139-5p/let-7e/30c,98 miR-126,100 and salivary exosomal miR-10b-5p105,106 expression levels were reduced, as they are tumor suppressors. Through the in vitro culturing of OSCC cell lines, miR-365 and other miRNAs are produced in exosomes aberrently107 and can be used to assess human papilloma virus (HPV) involvement.101 Tissue-derived exosomal circRNA_047733 can be used to indicate the lymph node metastasis (LNM) outcomes of OSCC cases with satisfying specificity and sensitivity.108 The in vivo application of these biomarkers necessitates further research. CirRNAs are back-splicing formed RNAs that influence protein translation through interacting with miRNAs, RNA-binding proteins, and RNA Pol.109 Serum exosomal circ_0000199 showed a higher level in OSCC patients and is associated with the Tumor Node Metastasis (TNM) stage and prognosis.110

Regarding the protein cargos of the exosomes, there are notable differences between the OSCC patients and healthy individuals. TGFβ, a well-known cancer biomarker, provides much more diagnostic and prognostic information for OSCCs in an exosomal form than in a soluble form.111 The level of the sera and salivary exosomal marker Alix increases significantly in OSCC patients, but the sensitivity in early cancer (stage I) detection is not satisfying. Moreover, exoAlix behaves differently in sera and saliva in a stage-dependent manner; only serum exoAlix presents prognosis information.112 In addition to single-exosomal protein biomarker detection, Li et al.113 demonstrated the advantages of combined exosomal C-reactive protein (CRP), von Willebrand factor (VWF), and leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein (LRG) in the determining specificity and sensitivity of early OSCCs diagnosis. The serum exosomal platelet factor 4 variant (PF4V1), C-X-C motif chemokine (CXCL7), coagulation factor XIII, A (F13A1) and Apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA1) not only enable discrimination between the OSCC cases and healthy controls, but also provide information on the lymph node metastasis status. The combination of these four biomarkers could also increase the preciseness.114

Biomarkers for other oral diseases

Exosomal biomarkers have also been discovered in other oral diseases. Viral infectious hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) mostly affects young patients under 5 years old with herpes.115 In the sera of patients with HFMD (both the mild and severe types), there is an elevated level of exosomal miR-16-5p, while the miR-671-5p and miR-150-3p levels were decreased.116 These statistical data demonstrated the satisfying sensitivity and specificity of exosomes as biomarkers in HFMD diagnosis.

Oral lichen planus (OLP) is an immune-related mucosa disease that is well recognized as a potentially malignant disorder.117 Therefore, its early diagnosis would inhibit the progression toward oral cancers and benefit the patients’ prognosis. The exosomal alteration in fluids has provided valuable information regarding OLP detection. Based on the evidence from the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique, the serum exosomal miR-34a-5p118 and salivary exosomal miR-4484119 were significantly upregulated in the OLP samples. Furthermore, the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV)-encoded miR-UL59 manifested a higher level in the OLP samples,120 suggesting the underlying connections between HCMV infection and the unclear etiology of OLP.

As an autoimmune disease related to the salivary glands, Sjögren’s syndrome causes alterations in various contents of patients’ fluids. Since 2010, scientists have reported the potential of exosomal miRNA biomarkers used for diagnosing Sjögren’s syndrome.121 Novel sequencing evidence has revealed that the levels of exosomal circRNAs circ-IQGAP2 and circ-ZC3H6 increased in the serum samples from primary Sjögren’s syndrome patients.122 In addition, in murine models, the levels of serum exosomal miRNA-127-3p, miRNA-409-3p, miRNA-410-3p, miRNA-541-5p, and miRNA-540-5p were upregulated.123 These findings deserve further research on the underlying mechanism via human studies.

Analysis technique for exosomes

Prior to our evaluation of exosomal biomarkers, the primary focus was the development of efficient and precise detection techniques. The separation and quantitative analysis of exosomes serve as crucial steps in clinical applications.124 Centrifugation is the conventional method used for exosome separation. To improve efficiency, differential centrifugation is the most commonly used and practical technique. This approach allows for the isolation of nucleic acid cargos at fractions of 0.3×103 and 2.0×103, while protein cargos appear at different fractions; Alix predominantly appears at the 160.0×103 fraction, and HSP70 exhibits an even distribution across a wide range from 0.3×103 to 160.0×103124,125 (Fig. 2a).

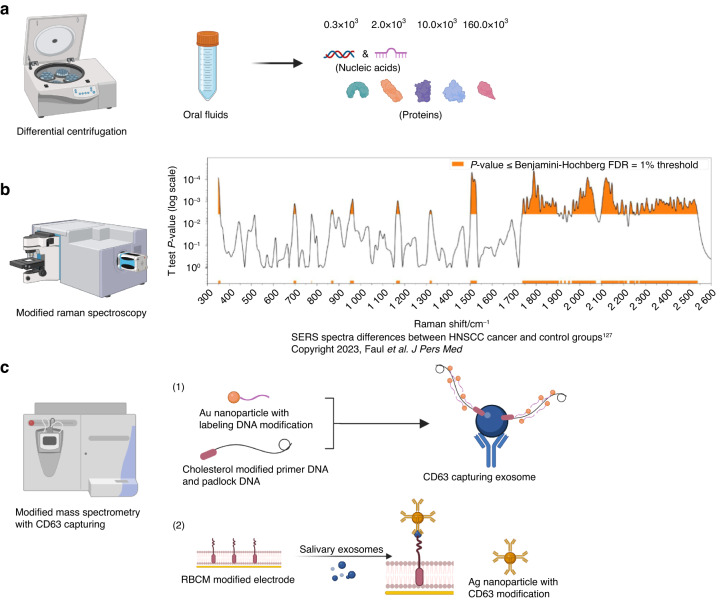

Fig. 2.

Schematic illustration of exosomal detection techniques. a Differential centrifugation can isolate exosome cargos at different fractions. b Surface enhancement Raman spectroscopy (SERS) demonstrates distinct Raman spectra between saliva samples from HNSCC and healthy control groups. c Modified mass spectrometry with CD63 capturing allows for quantitative analysis of exosomes. c-1 Detection of exosomal signal is achieved through cholesterol-based rolling circle amplification and gold-nanoparticle-labeled DNA. c-2 Red blood cell membrane (RBCM)-modified electrode can produce electrochemical signals of exosomes with Au nanoparticles

The requirements for exosomal quantitative analysis vary depending on specific objectives, such as particle enumeration, protein quantification, RNA quantification, etc.124 Consequently, the relevant methodologies include nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) and flow cytometry for particle enumeration, bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assaying and PAGE-SDS staining for protein quantification.124 Aiming at enhanced efficiency, other researchers have come up with more practical and precise methods for oral exosomal quantitative analysis. Surface enhancement Raman spectroscopy (SERS) is a modified form of Raman spectroscopy (the inelastic scattering of light), which shows an amplified vibrational Raman spectrum when the testing sample is in close proximity to a plasmonic nanostructured surface (Fig. 2b). Based on the analysis of saliva exosomes, SERS exhibits exceptional sensitivity and specificity in distinguishing malignant and normal ones, enabling the early diagnosis of head and neck cancers.126 Cheng et al. introduced a new technique for inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry, performing excellently in oral exosomes quantitative analysis.127 They captured exosomes with the CD63 antibody and detected a signal with cholesterol-based rolling circle amplification and gold-nanoparticle-labeled DNA (Fig. 2c-1). Also associated with CD63 capturing, red blood cell membrane (RBCM)-modified electrode could produce electrochemical signals once confronting exosomes, showing great precision in saliva exosomes detection128 (Fig. 2c-2).

Although significant progress has been made in the identification of exosomal biomarkers for diagnosing oral diseases, certain limitations still exist. The majority of studies lack sufficient evidence due to inadequate sample collection and classifications for exosomal biomarkers. These deficiencies pose challenges in standardizing their clinical applications. Furthermore, the techniques used for isolating and analyzing exosomes from human fluids are impractical for most basic medical institutions, and a valid consensus has not yet been reached. To address these issues, it is imperative to further develop technical capabilities and gain deeper insights into the role of exosomes in the progression of oral diseases, which will undoubtedly inspire more reliable diagnostic standards.

Exosomes in targeted therapy for oral diseases

Over recent years, exosomes have been extensively investigated in the treatment of multiple oral diseases. The primary research areas encompass the utilization of engineered exosomes as an innovative drug delivery tool with specific cargos and the clinical application of exosomes derived from orofacial stem cells in tissue regeneration. In this session, we summarize the current research on exosomal therapies toward infections, oral cancers, and the regeneration of pulp and bone.

Engineered exosomes

Anti-infection

Infectious pathogens play a significant role as causative agents and risk factors in various oral diseases. Recent studies have unveiled the potential of the application of exosomes as innovative therapies against microbial infections. An infection with Enterovirus 71 (EV-71) serves as the primary trigger for HFMD, leading to an elevated level of exosomes in the patients’ sera samples.116 Consequently, the utilization of the exosome inhibitor GW4869 could effectively reduce infectious activities.129 Exosomal miR-155 exhibits a comparable antiviral effect by targeting the phosphatidylinositol clathrin assembly protein (PICALM).130 As the first inhabitant microbes in the oral cavity, streptococci prominently influence oral health status, where dysbacteriosis may lead to caries and other oral inflammatory-related diseases. The exosomes separated from honey contain antimicrobial agents that have more potent effects on Streptococcus mutans in comparison to those of the other strains.131

Anti-cancer

Traditional chemo-/immunotherapies for OSCCs are often non-specific to the malignancy and incompatible with the host tissue. However, exosomes, which act as physiological “packages” between cells, may offer a solution to these issues.132 The application of engineered exosomes in OSCC treatment can disrupt various processes involved in oncogenesis and tumor microenvironment modulation, thereby effectively inhibiting cancer progression. According to recent studies, many cargos of exosomes attenuate the oncogenesis of OSCCs through complex signaling pathways133–138 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Exosomal cargos exhibiting anti-tumor effect on OSCCs

| Exo-cargo | Origin | Function | Mechanism | Research model | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-1294 | OSCC tissue | Inhibiting OSCC cells proliferation and migration | Targeting oncogene c-Myc | OSCC cell lines | 134 |

| miR-101-3p | Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) | Inhibiting OSCC occurrence and progression | Targeting collagen type X alpha 1 chain (COL10A1) |

OSCC cell lines Nude mice |

135 |

| miR-6887-5p | Eldecalcitol (ED71)-induced OSCC cells | Inhibiting OSCC cells proliferation | Targeting Heparin-binding protein 17/fibroblast growth factor–binding protein-1 (HBp17/FGFBP-1) |

OSCC cell lines Nude mice |

136 |

| miR-34a | Engineered exosomes from HEK-293T cells with miR-34a loading | Inhibiting OSCC cells proliferation, migration, and invasion | Targeting special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 2 (SATB2) | OSCC cells-HN6 | 137 |

| circRNA GDP dissociation inhibitor 2 (circGDI2) | Engineered exosomes from OSCC cells with circGDI2 loading | Inhibiting OSCC cells proliferation, migration, invasion and glycolysis | Regulating miR-424-5p and suppressor of cancer cell invasion (SCAI) |

OSCC cell lines BALB/c mice |

138 |

| LncRNA LBX1-AS1 | Immunoglobulin kappa J region (RBPJ) overexpressed macrophages | Inhibiting OSCC cells proliferation, and invasion | Regulating miR-182-5p/FOXO3 pathway |

OSCC cell lines Nude mice |

133 |

Engineered exosomes secreted from diverse cell types exert inhibitory effects on OSCC development through administrating different drugs or molecules. Macrophage-derived exosomal miR144/451 (tumor suppressive) connected with chitosan nanoparticles exhibit an anti-tumor effect in OSCCs.139 The exosomes secreted by menstrual stem cells performed anti-angiogenesis in OSCCs.140 In addition to host-derived exosomes, other researchers have also explored alternative sources of therapeutic exosomes for OSCC treatment. Milk exosomes are widely recognized for their exceptional resilience in acidic conditions within the digestive system and their ability to traverse physiological barriers.141 The engineered exosomes of milk combined with doxorubicin and an anthracene endoperoxide derivative demonstrate remarkable efficacy in eradicating OSCCs cells,142 showing great potential in clinical applications.

Novel delivery system based on engineered exosomes

Besides the dental tissue-derived and natural original exosomes mentioned above, engineered exosomes have demonstrated great value as a novel delivery system. The procedure of exosome engineering mainly consists of cargo encapsulation and surface modification, with each step encompassing various methodologies and indications.143 Exosomal cargo packing could be induced in situ by interactions between the cargos and donor cell components or in vitro after exosome purification.132 Generally, the in vitro methods show more flexibility and practicality in applications, including electroporation, incubation, sonication, extrusion, etc.80 In OSCC treatment, Epstein–Barr Virus Induced‑3 (EBI3) transfected fibroblasts were electroporated with anti-tumor small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), the productive engineered exosomes of which significantly targeting OSCCs cells by diminishing their proliferations.144 The incubation of miRNA-34a with HEK-293T cells also acquires effective exosomes against OSCCs.137

Surface modification is another important step in exosome engineering, aiming at enhancing exosomal targeting toward certain receptors. Multiple components can be added to the exosomal membrane, such as proteins, antigens, antibodies, and DNA/RNA aptamers.132 The relevant research has proved that the surface-modified exosomes with peptides can cross blood–brain barrier and treat cerebral ischemia.145,146 Although similar research on oral medicine is underway. However, exosome-mimetic nanoparticles have received great attention in oral cancer treatment for their convenience in surface engineering.147,148 These biomimetic particles could resemble membrane structures of multiple host cells (blood and stem cells) and escape from immune clearance.148

Dental stem cell-derived exosomes in regenerative therapy

Dental stem cells (DSCs) refer to a group of primitive cells derived from dental tissue, with the potential to proliferate and differentiate. DSCs are generally classified into dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs), stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHED), stem cells from apical papilla (SCAPs), PDLSCs, dental follicle cells (DFCs), and oral mesenchymal stem cells (OMSCs), based on their distinct histologic origin.149–151 The application of DSCs in oral regeneration treatment has long been embraced, and stem cell-derived exosomes have recently shown great promise for healing dental defects and orofacial tissues.

Pulp regeneration

Due to infectious or traumatic etiologies, pulpal and/or apical diseases invariably result in the irreversible impairment of blood, neural, and nutrient supplies to the natural teeth.152 Despite the well-established efficacy of root canal treatment (RCT), the quest for achieving biological pulp regeneration with complete physiological functionality remains ceaseless. There are a series of crucial steps in achieving dental pulp regeneration and forming a physiological pulpodentinal complex, for instance, differentiation from MSCs to functional dental pulp cells (DPCs), the promotion of angiogenesis, and the facilitation of neural reconstruction.153 Such as stem cells from pulp tissue, DPSC-derived exosomes positively stimulated the differentiation of stem cells toward DPCs through the P38/MAPK154 and miR‑150‑Tlr4 pathways.155 Meanwhile, Schwann cells are recruited to enhance neurogenesis with the presence of DPSC-derived exosomes, particularly under the condition of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation.156 LPS also promotes angiogenesis via DPSC-derived exosomes,157–159 which simultaneously could be enhanced by hypoxia with higher level of lysyl oxidase-like 2 (LOXL2).160,161 Compared with a normal status, DPSCs under odontogenic differentiation condition secrete more effective exosomes, for instance, the levels of miR-27a-5p are elevated, which induces DPSC differentiation.154,162 Furthermore, the evidence suggested that younger donors of DPSCs gave better performance to exosomal ability in pulp regeneration,163 as exosomal miR-26a secreted by aggregating stem cells from deciduous teeth (SHED) strongly promotes the angiogenesis of HUVECs in pulp tissue through TGF-β/Smad2/3 signaling.164 Moreover, the exosomes derived from dental pulp tissue (DPT) exhibit superior efficacy in modulating SCAPs for pulp regeneration compared to that of the DPSCs, which is attributed the “cell-homing technique“.165 SCAPs can also release exosomes, facilitating an anti-inflammatory effect on pulpitis during Treg conversion and the dentinogenic differentiation of MSCs,166,167 which demonstrate great potential as pulp regenerative therapies.

Besides the DSCs, there are several other stem cells that secrete functional exosomes in pulp regeneration. Embryonic stem cell (ESC)-derived exosomes promote DPCs maturation through CD73 (a type of nucleotidase)-mediated AKT/ERK pathway activation.168 Furthermore, the exosomes from umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (UCMSCs) showed a great effect on inflammatory alleviation after a pulp injury.169 And platelet-sourced exosomes also have the potential for pulp regeneration with thrombin activation.170

Orofacial bone regeneration

The conventional therapeutic sequence for periodontitis encompasses plaque control, re-evaluation, and surgical intervention. Regenerative surgery has emerged as a pioneering approach in clinical practice, aiming to restore periodontal tissue and regain functions.171 Alongside various biofilm and bone graft materials, recent studies have highlighted the potential of exosomal agents for orofacial bone reconstruction.172 Controlling the anomaly inflammatory changes in periodontal cells and the microenvironment is the premise of periodontitis regenerative treatment.11 Exhibiting periodontal anti-inflammatory effect, gingival mesenchymal stem cell (GMSC)-secreted exosomes target NF-κB signaling and Wnt5a in a periodontal microenvironment173,174 and modulate macrophage polarization in high-lipid-level175 or TNF-α pre-condition circumstances.176 A similar macrophage transformation also occurs with chitosan hydrogel-engineered DPSC-derived exosomes via miR-1246.177 In addition, MSC-derived exosomal miR-1246178 and PDLSC-derived exosomal miR-155-5p179/miR-205-5p180 inhibit inflammation by balancing the Th17/Treg ratio.

Alveolar bone loss is a typical manifestation of periodontitis. How to promote bone repair and regeneration is a key issue in periodontitis management. PDLSCs are a group of stem cells residing in the periodontium. The available evidence strongly supports that PDLSCs possess a robust self-renewal capacity and multipotential differentiation abilities. In periodontal regeneration, PDLSCs can differentiate into fibroblasts, osteoblasts, cementoblasts, etc.181 During these processes, various stem cells become the sources for exosomes, facilitating PDLSC proliferation and differentiation. Bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cell (BMSC)-derived exosomes have been applied with hydrogel in vivo,182 and SHED-derived exosomes were tested in vitro,183 both of which showed a promising effect on PDLSCs proliferation, migration, and differentiation. DFC-derived exosomes exhibited a higher efficiency with LPS stimulation through an ROS-mediated antioxidant mechanism in PDLSCs.184,185 UCMSC- and PDLSC-derived exosomes are able to activate PDLSCs’ functions even in high-glucose-level circumstances.186–188 The application of MSCs enhances periodontal ligament (PDL) cell activation after impairment via exosomes through the AKT/ERK pathway.189 In addition, adipose-derived stem/stromal cells (ADSCs) and DFCs exosomes performed a periodontal healing function in murine periodontitis models with newly formed PDL and alveolar bone.190,191 Nevertheless, there is a paucity of data related to the underlying mechanisms and applications in human models.

In addition to enhancing the differentiation of PDLSCs, there are also other methods used to promote orofacial bone regeneration, such as the direct activation of osteoblasts and the induction of BMSC osteogenesis. PDLSC-derived exosomes are capable of inducing osteoblast activation,192 while osteogenic-induced and differentiated PDLSCs can accelerate BMSC differentiation toward osteoblasts via significant exosomal miRNAs alteration, targeting various osteogenic-related signaling pathways, such as the MAPK and AMPK pathways.193 In addition, DPSC-derived exosomes induced jaw bone regeneration in vivo,194 and SHED-derived exosomes are capable of promoting naïve BMSCs’ differentiation into osteoblasts.195–197 While SHED-derived exosomes can promote DPSCs’ osteogenesis by regulating the mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM).198 To strengthen the bone repair effect, BMSCs can be innovatively engineered with overexpressed bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2) or miR-26a cargo. These functional modifications significantly improve bone regeneration through the exosomes, targeting the BMP2-associated signaling cascade/mTOR pathway.199,200 Moreover, immune modifications performed by engineered exosomes also promote bone regeneration. Dendritic cell-derived exosomes loaded with IL-10 and TGF-β can inhibit immune-related bone resorption and suppress bone loss.201 The exosomes secreted by M2 macrophages can be engineered with melatonin, exhibiting anti-inflammatory behavior and rescuing PDLSC potency in differentiation.202

Besides periodontitis, there are also other oral diseases characterized by bone destruction that necessitate exosomal regenerative therapies. Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common bone degenerative disease that mainly occurs in joints with cartilage degradation.203 The temporomandibular joint (TMJ), as the key joint enabling mandible movement, significantly influences chewing and pronouncing functions. Therefore, temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis (TMJOA) causes severe pain and inconvenience among patients.204 Similar to the mechanism of orofacial bone regeneration, the aims of exosomal therapies for TMJOA are reducing the inflammatory response and inducing chondrocyte differentiation.205 The SHED-derived exosomal miR-100-5p downregulates the inflammatory factors (IL-6, IL-8, and MMP1) in TMJOA by targeting mTOR signaling.206 Moreover, MSC-derived exosomes enhanced the overall cartilage regeneration, and this mechanism is associated with the adenosine activation of the AKT, ERK, and AMPK signaling pathways.205

Salivary gland revitalization

Exosomal regenerative therapies have also been developed to treat other oral diseases. The dysfunction of the salivary gland may occur in Sjogren’s syndrome, menopause, diabetes, or after radiotherapy for OSCC patients. In vivo studies of exosomal therapies for salivary gland recovery have been conducted using murine models. The DPSC-derived exosomes rescued salivary gland epithelial cells through the G-protein coupled estrogen receptor (GPER)-mediated cAMP/PKA/CREB pathway in Sjogren’s syndrome.207 And tonsil mesenchymal stem cell (T-MSC) exosomes contribute to the regaining of salivary gland function after an ovariectomy, resembling the menopause period.208 The application of BMSC-derived exosomes could reduce the salivary gland complications in diabetes via the TGF-β/Smad3 pathway,209 while the exosomes from the salivary gland performed a similar effect via an unclear mechanism.210 Urine-derived stem cells (USCs) under hypoxia stimuli secrete exosomes to repair the salivary gland after radiotherapy via the Wnt3a/GSK3β pathway.211

Skin regeneration based on anti-aging effect

Skin senescence is a progressive process, with the declining proliferation of cells, reducing ECM, and decreasing repair ability resulting in skin dysfunction. Both intrinsic and extrinsic factors (smoking/ultraviolet light) could influence the skin senescence procedure.212 This issue has garnered significant public attention, particularly in the orofacial area, due to its profound impact on patients’ esthetic appearance and functional needs. Novel research has proved the potential applications of stem cell-derived exosomes in skin regeneration based on their anti-aging effects.

The dermis, the layer of skin under the epidermis, mainly consists of the ECM, which is regulated by dermal fibroblasts. As a long-lived cell type, dermal fibroblasts can be used to indicate the skin senescent status through accumulated damage and repair.213 Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived exosomes exhibit significant anti-aging effects on dermal fibroblasts, which manifests as the downregulated level of senescence-associated-β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) and MMP1/3 and the restoration of collagen type I.214 In aged murine models with wounds, the exosomes isolated from young donor wound edge fibroblasts can facilitate fibroblasts differentiation through miR-125b, inhibiting sirtuin 7 (Sirt7).215 Similarly, trophoblast-derived exosomes can activate dermal fibroblasts as well.216

Wound healing is an intricate process including an inflammatory response, stem cell differentiation and proliferation, ECM modulation, etc.217 Senescent skin cells can perform SASP, inducing vicinal inflammation and postponing the healing process.218 A pressure ulcer, defined as the localized damage of skin tissue due to a combination of shear and friction,219 commonly appears in the orofacial area. A recent survey has suggested the high incidence of facial pressure ulcers in patients with respiratory destruction (such as COVID-19) due to staying prone.220 ESC-derived exosomes can rejuvenate epithelial cells and promote the angiogenesis process in aged murine models of pressure ulcers. This mechanism is associated with enriched miR-200a cargo and activated nuclear factor-like 2 (Nrf2) signaling.221

Besides the aging factor, the SASP also plays a role in several endocrine diseases, including diabetes.222 Diabetic wounds commonly appear on oral soft and hard tissues, which struggle to heal, leading to great suffering.223 Therefore, diabetic wound healing requires anti-aging therapies as well, and stem cell-derived exosomes can reduce the SASP. ADSC-derived exosomes accelerated diabetic wound healing, and Nrf2 overexpression enhanced this effect.224 A novel biomaterial, oxygen-releasing, antioxidant wound dressing, OxOBand, loaded with ADSC-derived exosomes has been applied in murine diabetic models and shown great performances.225 Fetal mesenchymal stem cells (fMSC) can also promote diabetic wound healing through exosomes.226 Of note, dental stem cells, such as SHED-derived exosomes, have been used for tendon regeneration, with a significant anti-aging effect through NF-κB inhibition,227 which has encouraged us to expand the application of oral original exosomes into other fields.

Scaffolds for exosomes in oral regenerative therapy

In addition to exploring the novel sources of exosomes for oral tissue regeneration, it is crucial to consider appropriate scaffolds that interact synergistically with the exosomes in order to optimize the therapeutic efficacy. According to previous studies on pulp regenerative treatment with stem cells, an injectable hydrogel is convenient as a biomaterial applied to the root canals. Different types of scaffolds (such as natural collagen-based scaffolds and synthetic/hybrid materials) with injectable hydrogel have been investigated.228 In terms of the scaffolds loaded with exosomes, we should widen our scope to meet the new demands for exosomal applications. Generally, DPSC-derived exosomes can bind to collagen type I and fibronectin, thereby connecting with the biomaterials and promoting DPSC differentiation.154 However, these findings were not completed with a certain implementable biomaterial system. Furthermore, the hydrogels engineered with hydroxypropyl chitin (HPCH)/chitin whisker (CW) and the hydrogels with fibrin can both facilitate attraction between the exosomes and MSCs, showing injectable and biocompatible behaviors, ultimately accelerating the exosomes’ effect on pulp regeneration.229,230 The controlled releasement of exosomes is also a promising prospect for bio-scaffolding. Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA)-based biodegradable microspheres have been recently developed to have continuous exosomal effects on pulp regeneration.231

In orofacial bone regeneration, the traditional scaffolds mostly focus on mimicking the extracellular matrix (ECM) of natural bones, aiming at enhancing MSC adhesion and osteogenic differentiation.232 With a further understanding of the role of exosomes in bone regeneration, new demands for bio-scaffolds are emerging in cell-free therapies. Lyophilized BMSC-derived exosomes on hierarchical mesoporous bioactive glass (MBG) can satisfy both bioactive maintenance and the continuous releasement of exosomes.233 In vitro experiments also proved that titanium nanotubes loaded with BMP2-stimulated macrophage-derived exosomes upregulate osteogenic marker (such as alkaline phosphatase) expression.234 As a biodegradable polymer that has been widely accepted in controlled delivery,235 PLGA has a great performance in exosomal bone regeneration.236 Poly-dopamine (pDA)-modified PLGA can ensure the controlled release of exosomes from adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs), significantly enhancing skull bone repair in murine models.237 Combined with metal-organic framework (MOF), the PLGA/Exo-Mg2+-gallic acid (GA) system provides the advantages of ADSC-derived exosomes, Mg2+ and GA in the anti-inflammation, angiogenesis, and osteogenic differentiation of bone regeneration.238 Moreover, adding VEGF and DPSC-derived exosomes to an injectable chitosan nanofibrous microsphere-based PLGA-poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-PLGA hydrogel strongly promotes angiogenesis and osteogenesis.239 In recent decades, the production of three-dimensional (3D) scaffolds has been widely used in exosomal regenerative medicine.240 Three-dimensional-printed silk fibroin/collagen I/nano-hydroxyapatite (SF/COL-I/nHA) scaffolds loaded with UCMSC-derived exosomes could stimulate alveolar bone defect repair in murine models.241 In addition, novel scaffolds can also enhance cartilage regeneration. Lithium-substituted bioglass ceramic (Li-BGC) significantly promoted the BMSC-derived exosomal effect on chondrogenesis.242

Based on the convincing evidence that DSC-derived exosomes contribute to various oral regenerative therapies, more research is underway. The expansion of MSC-derived exosomes from other tissue origins may benefit oral therapies. And the crosstalk between oral and other diseases, such as general OA243 and TMJOA, should be highlighted. Overall, the application of exosomes is one of the key points in oral regenerative treatment. Basic-to-clinic translation is one of the future focuses.

Conclusions and prospects

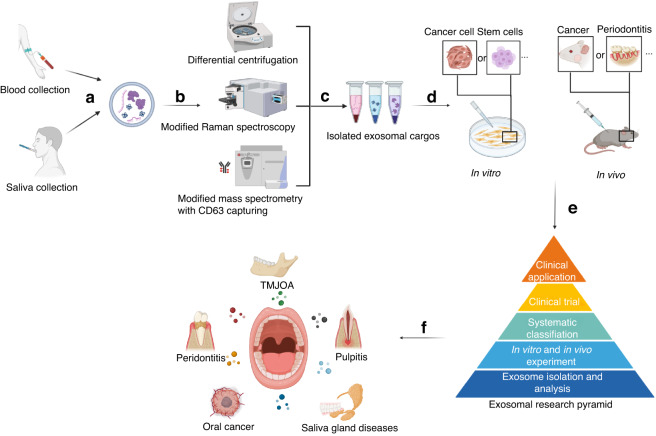

Exosomes have emerged as a novel research frontier, with a significant application potential across diverse fields. In the realm of oral medicine, exosomes hold promise as non-invasive biomarkers for early disease diagnosis by distinguishing between pathological and healthy states, with periodontitis and OSCCs as the most convincing examples. Furthermore, exploring the distinct characteristics and alterations in exosomes during the progression of oral diseases can deepen our understanding of their underlying pathological mechanisms and pave the way for targeted therapeutic interventions and treatment efficacy. Stem cell-related studies and applications are currently at the forefront of medical research, particularly in relation to regenerative treatments for oral diseases. This intersection with exosome biology provides a valuable foundation for the rational utilization of stem cells (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Research flow for exosomes in oral diseases. Exosomes can be obtained from human fluids, such as saliva collected from the oral cavity, providing non-invasive methods for disease detection (a). Subsequently, exosomes are isolated from diverse sources, separated and analyzed by novel techniques (e.g., modified centrifugation) (b, c). The distinct effects of exosomes are then examined through in vitro and/or in vivo experiments (d). These comprehensive research findings contribute to the development of a systematic understanding of exosomes, serving as a foundation for clinical applications (e). Finally, with a well-established experimental basis, exosomes meet practical clinical applications in oral medicine (f)

Despite the existing research and applications of exosomes in oral medicine, there are still several limitations. First, the identification, analysis, and synthesis of oral exosomes are not precise or convenient enough. In accordance with the updated guidelines for exosomal research244 and the specific characterization of the oral cavity (such as the availability of saliva), it is imperative to develop more advanced techniques that will undoubtedly expand the applications of exosomes in oral diseases. Reducing the technique barriers is also important for the promotion of exosomes in real-world medicine, especially in large-scale production and stable storage-to-transportation strategies. Exosomal biomimetic materials might also be promising, combining the inherent advantages of natural exosomes with industrial synthesis techniques. Meeting these diverse demands necessitates collaborative efforts across the biomedical field, while we should raise specific views based on oral diseases properties. Second, there is still lack of clear catalog of the exosomes in oral diseases. Though the current studies involve exosomes in various aspects of oral medicine, they are not yet systematic. While exosomes’ classification primarily relies on their origin, it is worth considering alternative approaches, such as their targeting specific signaling pathways or exploring their distinct effects on cellular functions. With more insights into the abundant exosomal roles throughout oral disease progression and treatment, we ought to find general paths for the future exploration of novel exosomes. These avenues necessitate a deeper understanding of both the exosomes themselves and the underlying mechanisms involved in oral diseases. Third, clinical trials on exosomes in oral diseases are still scarce. According to a relevant analysis, the clinical trials on exosomes have mainly fallen under the respiratory research category, such as biomarkers for lung cancer and therapies for SARSCoV-2 pneumonia.245 The primary challenges in conducting clinical trials on exosomes for oral diseases pertain to establishing standardized production criteria and determining the precise dosages for specific indications. Therefore, future studies should prioritize quality control measures and expand the experimental models to more advanced animals. In addition, investigating the crosstalk between oral diseases and other systemic diseases focusing the exosome’s communications could provide valuable insights for future research.

In summary, while the current research on exosomes in oral medicine has yielded significant achievements, there is a substantial amount of work to be conducted. Future studies should not only focus on the physiological and pathological molecular mechanisms associated with exosomes, but also emphasize the feasibility of relevant clinical translation, enhancing the exploration and application of efficient and effective exosomal therapies.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants (82370945, 82171001, 82222015 and 82370915). Research Funding from West China School/Hospital of Stomatology Sichuan University (RCDWJS2023-1). Figures were created with BioRender.com.

Author contributions

J.W. and Y.F. organized the manuscript. J.W. wrote the draft. J.J., C.Z. and Y.F. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the article

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Le H, et al. Oral health disparities and inequities in Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. Am. J. Public Health. 2017;107:S34–S35. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peres MA, et al. Oral diseases: a global public health challenge. Lancet. 2019;394:249–260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng L, Hill AF. Therapeutically harnessing extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2022;21:379–399. doi: 10.1038/s41573-022-00410-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cocucci E, Meldolesi J. Ectosomes and exosomes: shedding the confusion between extracellular vesicles. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25:364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalluri R, LeBleu VS. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science. 2020;367:eaau6977. doi: 10.1126/science.aau6977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meldolesi J. Exosomes and ectosomes in intercellular communication. Curr. Biol. 2018;28:R435–R444. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathieu M, Martin-Jaular L, Lavieu G, Théry C. Specificities of secretion and uptake of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles for cell-to-cell communication. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019;21:9–17. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0250-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hessvik NP, Llorente A. Current knowledge on exosome biogenesis and release. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018;75:193–208. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2595-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Niel G, D’Angelo G, Raposo G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018;19:213–228. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyle J, Chapple I. Molecular aspects of the pathogenesis of periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 2015;69:7–17. doi: 10.1111/prd.12104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinane DF, Stathopoulou PG, Papapanou PN. Periodontal diseases. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2017;3:17038. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai, R. et al. The role of extracellular vesicles in periodontitis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. Front. Immunol.14, 1151322 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Zhang Z, et al. PDLSCs regulate angiogenesis of periodontal ligaments via VEGF transferred by exosomes in periodontitis. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2020;17:558–567. doi: 10.7150/ijms.40918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xia Y, et al. The miR-223-3p regulates pyroptosis through NLRP3-Caspase 1-GSDMD signal axis in periodontitis. Inflammation. 2021;44:2531–2542. doi: 10.1007/s10753-021-01522-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Z, et al. Oxidative stress state inhibits exosome secretion of hPDLCs through a specific mechanism mediated by PRMT1. J. Periodontal. Res. 2022;57:1101–1115. doi: 10.1111/jre.13040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi J-W, Kim S-C, Hong S-H, Lee H-J. Secretable small RNAs via outer membrane vesicles in periodontal pathogens. J. Dent. Res. 2017;96:458–466. doi: 10.1177/0022034516685071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elsayed R, et al. Microbially-induced exosomes from dendritic cells promote paracrine immune senescence: novel mechanism of bone degenerative disease in mice. Aging Dis. 2023;14:136–151. doi: 10.14336/AD.2022.0623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu, X. et al. Mechanisms of mechanical force aggravating periodontitis: a review. Oral Dis.10.1111/odi.14566 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Wu, Y. et al. Exosomes from cyclic stretched periodontal ligament cells induced periodontal inflammation through miR-9-5p/SIRT1/NF-κB signaling pathway. J. Immunol.10.4049/jimmunol.2300074 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Zhao M, Ma Q, Zhao Z, Guan X, Bai Y. Periodontal ligament fibroblast-derived exosomes induced by compressive force promote macrophage M1 polarization via Yes-associated protein. Arch. Oral. Biol. 2021;132:105263. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2021.105263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piccolo S, Dupont S, Cordenonsi M. The biology of YAP/TAZ: hippo signaling and beyond. Physiol. Rev. 2014;94:1287–1312. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00005.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matthaios D, Tolia M, Mauri D, Kamposioras K, Karamouzis M. YAP/Hippo pathway and cancer immunity: it takes two to tango. Biomedicines. 2021;9:1949. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9121949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atsawasuwan P, et al. Secretory microRNA-29 expression in gingival crevicular fluid during orthodontic tooth movement. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0194238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng, X. et al. Biological characteristics of microRNAs secreted by exosomes of periodontal ligament stem cells due to mechanical force. Eur. J. Orthod.10.1093/ejo/cjad002 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Chang M, Chen Q, Wang B, Zhang Z, Han G. Exosomes from tension force-applied periodontal ligament cells promote mesenchymal stem cell recruitment by altering microRNA profiles. Int. J. Stem Cells. 2023;16:202–214. doi: 10.15283/ijsc21170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang H-M, et al. Mechanical force-promoted osteoclastic differentiation via periodontal ligament stem cell exosomal protein ANXA3. Stem Cell Rep. 2022;17:1842–1858. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2022.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu X, Muhammed FK, Liu Y. Simvastatin encapsulated in exosomes can enhance its inhibition of relapse after orthodontic tooth movement. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2022;162:881–889. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2021.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarode G, et al. Epidemiologic aspects of oral cancer. Dis. Mon. 2020;66:100988. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2020.100988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hernández-Morales A, et al. Lip and oral cavity cancer incidence and mortality rates associated with smoking and chewing tobacco use and the human development index in 172 countries worldwide: an ecological study 2019–2020. Healthcare. 2023;11:1063. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11081063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan Y, et al. Oral squamous cell carcinomas: state of the field and emerging directions. Int. J. Oral. Sci. 2023;15:44. doi: 10.1038/s41368-023-00249-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qadir F, et al. Transcriptome reprogramming by cancer exosomes: identification of novel molecular targets in matrix and immune modulation. Mol. Cancer. 2018;17:97. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0846-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Razzo BM, et al. Tumor-derived exosomes promote carcinogenesis of murine oral squamous cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2020;41:625–633. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgz124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li X, Yang T, Shu C. The oral tumor cell exosome miR-10b stimulates cell invasion and relocation via AKT signaling. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging. 2022;2022:3188992. doi: 10.1155/2022/3188992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 34.Li C, et al. Exosomal long noncoding RNAs MAGI2-AS3 and CCDC144NL-AS1 in oral squamous cell carcinoma development via the PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling pathway. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2022;240:154219. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2022.154219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanahan D. Hallmarks of cancer: new dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022;12:31–46. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Squarize CH, et al. PTEN deficiency contributes to the development and progression of head and neck cancer. Neoplasia. 2013;15:461–471. doi: 10.1593/neo.121024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yan W, et al. Exosomal miR-130b-3p promotes progression and tubular formation through targeting PTEN in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021;9:616306. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.616306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hou C-X, et al. Exosomal microRNA-23b-3p promotes tumor angiogenesis and metastasis by targeting PTEN in salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2022;43:682–692. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgac033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.He S, et al. Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC)-derived exosomal MiR-221 targets and regulates phosphoinositide-3-kinase regulatory subunit 1 (PIK3R1) to promote human umbilical vein endothelial cells migration and tube formation. Bioengineered. 2021;12:2164–2174. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2021.1932222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang H, et al. OSCC exosomes regulate miR-210-3p targeting EFNA3 to promote oral cancer angiogenesis through the PI3K/AKT pathway. BioMed. Res. Int. 2020;2020:e2125656. doi: 10.1155/2020/2125656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li S, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-exosome-mediated matrix metalloproteinase 1 participates in oral leukoplakia and carcinogenesis by inducing angiogenesis. J. Oral. Pathol. Med. 2022;51:638–648. doi: 10.1111/jop.13321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hinshaw DC, Shevde LA. The tumor microenvironment innately modulates cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2019;79:4557–4566. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mito I, et al. Tumor-derived exosomes elicit cancer-associated fibroblasts shaping inflammatory tumor microenvironment in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral. Oncol. 2023;136:106270. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2022.106270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li C, Teixeira AF, Zhu H-J, Ten Dijke P. Cancer associated-fibroblast-derived exosomes in cancer progression. Mol. Cancer. 2021;20:154. doi: 10.1186/s12943-021-01463-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun L-P, et al. Cancer‑associated fibroblast‑derived exosomal miR‑382‑5p promotes the migration and invasion of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2019;42:1319–1328. doi: 10.3892/or.2019.7255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.He L, et al. Exosomal miR-146b-5p derived from cancer-associated fibroblasts promotes progression of oral squamous cell carcinoma by downregulating HIPK3. Cell Signal. 2023;106:110635. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2023.110635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li Y-Y, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts contribute to oral cancer cells proliferation and metastasis via exosome-mediated paracrine miR-34a-5p. EBioMedicine. 2018;36:209–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kallinger, I. et al. Tumor gene signatures that correlate with release of extracellular vesicles shape the immune landscape in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Exp. Immunol.10.1093/cei/uxad019 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Yunna C, Mengru H, Lei W, Weidong C. Macrophage M1/M2 polarization. Eur. J. Pharm. 2020;877:173090. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pan Y, Yu Y, Wang X, Zhang T. Tumor-associated macrophages in tumor immunity. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:583084. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.583084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oshi M, et al. M1 Macrophage and M1/M2 ratio defined by transcriptomic signatures resemble only part of their conventional clinical characteristics in breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:16554. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73624-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ludwig N, et al. TGFβ+ small extracellular vesicles from head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells reprogram macrophages towards a pro-angiogenic phenotype. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2022;11:e12294. doi: 10.1002/jev2.12294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xiao M, Zhang J, Chen W, Chen W. M1-like tumor-associated macrophages activated by exosome-transferred THBS1 promote malignant migration in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018;37:143. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0815-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.You Y, et al. M1-like tumor-associated macrophages cascade a mesenchymal/stem-like phenotype of oral squamous cell carcinoma via the IL6/Stat3/THBS1 feedback loop. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022;41:10. doi: 10.1186/s13046-021-02222-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu L, Ye S, Yao Y, Zhang C, Liu W. Oral cancer stem cell-derived small extracellular vesicles promote M2 macrophage polarization and suppress CD4+ T-cell activity by transferring UCA1 and targeting LAMC2. Stem Cells Int. 2022;2022:5817684. doi: 10.1155/2022/5817684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Manikandan M, et al. Oral squamous cell carcinoma: microRNA expression profiling and integrative analyses for elucidation of tumourigenesis mechanism. Mol. Cancer. 2016;15:28. doi: 10.1186/s12943-016-0512-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cai J, Qiao B, Gao N, Lin N, He W. Oral squamous cell carcinoma-derived exosomes promote M2 subtype macrophage polarization mediated by exosome-enclosed miR-29a-3p. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2019;316:C731–C740. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00366.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]