Abstract

Canine synovial membrane explants were exposed to high- or low-passage Borrelia burgdorferi for 3, 6, 12, and 24 h. Spirochetes received no treatment, were UV light irradiated for 16 h, or were sonicated prior to addition to synovial explant cultures. In explant tissues, mRNA levels for the proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1α (IL-1α), IL-1β, and IL-8 were surveyed semiquantitatively by reverse transcription-PCR. Culture supernatants were examined for numbers of total and motile (i.e., viable) spirochetes, TNF-like and IL-1-like activities, polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) chemotaxis-inducing activities, and IL-8. During exposure to synovial explant tissues, the total number of spirochetes in the supernatants decreased gradually by ∼30%, and the viability also declined. mRNAs for TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-8 were up-regulated in synovial explant tissues within 3 h after infection with untreated or UV light-irradiated B. burgdorferi, and mRNA levels corresponded to the results obtained with bioassays. During 24 h of coincubation, cultures challenged with untreated or UV light-irradiated spirochetes produced similar levels of TNF-like and IL-1-like activities. In contrast, explant tissues exposed to untreated B. burgdorferi generated significantly higher levels of chemotactic factors after 24 h of incubation than did explant tissues exposed to UV light-treated spirochetes. In identical samples, a specific signal for IL-8 was identified by Western blot analysis. High- and low-passage borreliae did not differ in their abilities to induce proinflammatory cytokines. No difference in cytokine induction between untreated and sonicated high-passage spirochetes was observed, suggesting that fractions of the organism can trigger the production and release of inflammatory mediators. The titration of spirochetes revealed a dose-independent cytokine response, where 103 to 107 B. burgdorferi organisms induced similar TNF-like activities but only 107 spirochetes induced measurable IL-1-like activities. The release of chemotactic factors was dose dependent and was initiated when tissues were infected with at least 105 organisms. We conclude that intact B. burgdorferi or fractions of the bacterium can induce the local up-regulation of TNF-α, IL-1α, and IL-1β in the synovium but that the interaction of viable spirochetes with synovial cells leads to the release of IL-8, which probably is a prime initiator of PMN migration during acute Lyme arthritis.

Lyme disease or Lyme borreliosis is a tick-borne disease of humans (41) and animals (1, 25, 33) caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Disease-associated changes manifest themselves in one or several organs, particularly the skin, joints, nervous system, and heart, and the clinical outcome seems to depend on the genospecies of B. burgdorferi (50). The skin and musculoskeletal system are the predominantly affected organ systems in North America, where B. burgdorferi sensu stricto is the prevalent borrelia species (41, 50).

Despite numerous studies, limited information is available on many aspects of the pathogenesis of Lyme disease. For example, a detailed description of the interplay between spirochete and host is lacking, and so it is still unknown how spirochetes induce inflammation in tissue. The accumulation of leukocytes in the joint capsules and joint cavity during the acute phase of Lyme arthritis has been studied in humans, mice, and dogs (4, 41, 45). In dogs this leukocyte population is up to 97% polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs), indicating an important role for PMNs during the early stage of acute Lyme arthritis. PMNs egress from blood vessels, and migration and accumulation in tissue require the up-regulation of endothelial adhesion factors and a source of chemotactic factors. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), gamma interferon, interleukin-1α (IL-1α), IL-1β, IL-1 receptor antagonist, IL-6, and leukotriene B4 are factors that have been reported to be involved in Lyme arthritis (5, 8, 13, 26, 27, 53). In contrast, surprisingly little information is available on the involvement of IL-8, which is a potent initiator of migration of PMNs and other leukocytes from blood vessels into tissue (2).

During B. burgdorferi infection in humans and dogs, spirochetes were found in inflamed tissues and frequently in arthritic joints (7, 12, 42). Additionally, B. burgdorferi was shown to be a potent cytokine-stimulating factor in vitro. Cells tested in different systems consisted of blood monocytes, macrophages, lymphocytes, and fibroblasts, and the production of TNF-α, gamma interferon, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, and IL-8 was studied (8, 16–18, 24, 34, 36, 40). In some studies, live organisms exhibited stronger stimulatory effects than heat-inactivated spirochetes (17, 18), pointing to an active interaction between viable spirochetes and host cells. However, outer surface proteins of B. burgdorferi, such as OspA and OspB, possess mitogenic and cytokine-stimulating properties (19, 24, 46). IL-1β was reported to be induced by the activation of the nuclear translocation factor NF-κB (32).

In studies of infectious diseases, most in vitro systems employ single cell populations to evaluate the response to specific stimuli. Obviously, interactions between different cell types cannot occur in these systems, and positive and negative feedback mechanisms may not develop. Explant cultures, on the other hand, contain a variety of different cell types, which allow the study of a complex and more natural response of a tissue to extrinsic factors. Recently, we have demonstrated in vivo that IL-8 is produced and released in synovial membranes during acute experimental Lyme arthritis in dogs (45). The in vivo study did not entirely rule out the possibility of immune complex involvement in the pathogenesis of this disease. One product generated by immune complexes is the complement factor C5a, which, like IL-8, is also a potent chemotactic factor for PMNs.

In this study we investigated the effect of B. burgdorferi on canine synovial explant cultures in the absence of borrelia-specific antibodies and complement factors. This model provides an opportunity to investigate the synovial cytokine response at the level of mRNA expression and cytokine release following B. burgdorferi challenge under controlled conditions. As Lyme arthritis in dogs shares clinical and pathological features with the disease in human beings (1), these studies should be of considerable comparative interest.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

B. burgdorferi.

High-passage (passage 45 [P45] and P46) and low-passage (P2 and P3) B. burgdorferi organisms, originally isolated from skin biopsies of experimentally infected dogs, were used for these experiments. The dogs had been exposed to infected ticks collected in North Salem, Westchester County, N.Y. (1). Cultures were propagated and passaged in BSK II medium with 8 μg of kanamycin (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) per ml and 50 μg of rifampin (Sigma) per ml at 34°C. One-milliliter aliquots of spirochete suspensions (P43 or original reisolate) containing 15% glycerin (Sigma) were frozen at −80°C. For explant experiments, aliquots were thawed and inoculated into 6 ml of BSK II medium with kanamycin and rifampin. Cultures were incubated at 34°C. During the following two passages, spirochetes were cultured at 34°C for 2 days (P45 and P46) or 3 days (P2 and P3) before they were added to explant cultures. Spirochetes were sedimented at 10,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, and the pellet was resuspended in serum-free Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) without phenol red (Sigma) and with 8 μg of kanamycin per ml (HBSS + K). Bacterial cell counts and viability of the spirochetes were determined with a Petroff-Hausser counting chamber (Krackeler, Albany, N.Y.), and the concentration of the bacteria was adjusted to 1.4 × 108 to 2.6 × 108 borreliae/ml. This concentration was estimated to yield a cell/bacterium ratio of at least 1:10. Motile spirochetes were considered viable. In four experiments, 50% of the cultures were transferred into 10-cm-diameter petri dishes and irradiated with UV light at a distance of 30 cm for 16 h to obtain bacterial suspensions with whole nonmotile organisms. In a fifth experiment, 50% of the spirochete suspension was subjected to sonication. In a final experiment, the number of spirochetes added to synovial explant tissues was varied (107, 105, 103 per tissue) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

B. burgdorferi and canine tissues used in synovial explant cultures

| Expt |

B. burgdorferi

|

Dogs

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passage | Treatment | Inoculum (107 per well) | Age (mo) | Sex | |

| 1 | 45 | None or UV light | 1.6–2.1 | 8 | Male |

| 2 | 46 | None or UV light | 1.4–1.8 | 8 | Male |

| 3 | 2 | None or UV light | 2.3–2.6 | 14 | Female |

| 4 | 3 | None or UV light | 1.6–1.8 | 8 | Male |

| 5 | 46 | None or sonication | 2.0 | 10 | Male |

| 6 | 45 | None | 0.0001–1.0 (titration) | 8 | Female |

Synovial explant cultures.

Synovial membranes were collected from the knee joints of six normal Labrador retrievers from the James A. Baker Institute colony. The dogs were 8 to 14 months old and were kept in conformance with the Animal Welfare Act and the New York State Department of Health regulations.

All synovial explant cultures were maintained in 24-well plates (Corning, Corning, N.Y.) in HBSS + K. After euthanasia of the dogs, synovial membranes from the knees were removed under sterile conditions and immersed in HBSS + K. Membranes were cut into pieces (approximately 5 by 5 mm) and transferred into 24-well plates, which contained 0.9 ml of HBSS + K without serum in each well. In 13 preliminary experiments, different media (BSK II, RPMI 1640, and HBSS, all with and without phenol red or with and without fetal bovine serum [FBS]) were evaluated for spirochete and tissue survival in vitro. In addition, conditions for reliable cytokine detection in tissues and culture supernatants were established. As a consequence, BSK II-free HBSS was chosen for its ability to support short-term survival of borreliae in culture. FBS was eliminated because it could have contained factors (chemokines or complement) which would have interfered with the chemotaxis assay and with Western blots. Plates were incubated at 37°C in humidified air with 5% CO2 for 30 min before the addition of the spirochetes.

Cocultivation of synovial explant tissues with B. burgdorferi was performed in quadruplicate. Explant cultures received 100 μl of either medium only, medium with borreliae, or medium with irradiated or sonicated borreliae. As further controls, plates without synovial membranes were prepared with identical contents. Cultures were held at 37°C in humidified air with 5% CO2.

After 3, 6, 12, and 24 h of cocultivation, tissues and culture supernatants were harvested. At these time intervals, the number and viability of the spirochetes in the culture medium were determined with a counting chamber. Tissues were removed from the culture plates, transferred into siliconized 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes (Laboratory Product Sales, Rochester, N.Y.), snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until used. Supernatants were transferred into 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 min in a microcentrifuge (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Aliquots of the cell-free supernatants were stored at −80°C until used.

Detection of mRNAs of TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-8 by RT-PCR.

Extraction of RNA, transcription into cDNA and subsequent DNA amplification, and separation and visualization of DNA were done in different rooms with different sets of instruments to avoid any contamination with previously amplified DNA fragments.

(i) Extraction of total RNA.

Total RNA was extracted from explant culture tissues with an RNA extraction kit from Qiagen (Chatsworth, Calif.). Glassware and metal grinders were held at 280°C for 8 h prior to any experiment. RNase-free plastic supplies were kept under contamination-free conditions. Experiments were performed in siliconized plastic tubes. Tissues were homogenized in 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes with the supplied lysis buffer, and tissue particles were removed by centrifugation (18,000 × g, 3 min). mRNA-containing supernatant was removed, mixed with the same volume of 70% ethanol, and applied to RNA-absorbent spin columns. Washing steps were carried out according to the manufacturer’s protocol to remove protein and DNA, and remaining mRNA was recovered with diethyl pyrocarbonate (Sigma)-treated water. The amount and the purity of extracted total RNA were measured with a spectrophotometer (λ1 = 260 nm and λ2 = 280 nm) (Beckman, Fullerton, Calif.).

(ii) RT.

Reactions were carried out in a GeneAmp 9600 PCR system (Perkin-Elmer). One-tenth microgram of total RNA in 50 μl of reverse transcription (RT) buffer containing 1× PCR Buffer II (Perkin-Elmer), 5.0 mM MgCl2 (Perkin-Elmer), 1.0 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Perkin-Elmer), 18 U of RNase inhibitor (Promega, Madison, Wis.), 200 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.), and 2.5 mM oligo(dT)18 (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) was transcribed into cDNA at 24°C for 10 min followed by 42°C for 30 min. The cDNA then was held at 98°C for 5 min. Five-microliter aliquots of each sample were transferred into new 96-well microtiter plates, sealed with adhesive sealer tape, and stored at −80°C until used.

(iii) PCR.

PCR primers for canine TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8 were designed based on the published sequences for canine TNF-α (55), canine IL-1β (11), and canine IL-8 (14). The primer set for canine IL-1α was designed to bind to highly conserved regions of IL-1α mRNA from human (30), rhesus monkey (51), guinea pig (54), rat (31), and cattle (20). The sequences of the primers (F, forward; R, reverse) are as follows: TNF-α-F, 5′-CTCTTCTGCCTGCTGCAC-3′; TNF-α-R, 5′-GCCCTTGAAGAGGACCTG-3′; IL-1α-F, 5′-TTTGAAGACCTGAAGAACTGTTAC-3′; IL-1α-R, 5′-GTTTTTGAGATTCTTAGA(G/A)TCAC-3′; IL-1β-F, 5′-CACAGTTCTCTGGTAGATGAGG-3′; IL-1β-R, 5′-TGGCTTATGTCCTGTAACTTGC-3′; IL-8-F, 5′-AGGGATCCTGTGTAAACATGACTTCC-3′; and IL-8-R, 5′-GGAATTCACGGATCTTGTTTCTC-3′. These primers were predicted to amplify a 288-bp fragment for TNF-α, a 545-bp fragment for IL-1α, a 262-bp fragment for IL-1β, and a 330-bp fragment for IL-8 with cDNA as a template. Primers originally designed to amplify a fragment from the published bovine β-actin sequence (BAC-1, 5′-ATGTTCAGGGACTTTGGACG-3′; BAC-2, 5′-ACCAGCCATCCAGACAAAAC-3′ [47]) were found to amplify a homologous segment of the canine β-actin. They were used to monitor the amount of mRNA in the reaction. PCR was performed with a GeneAmp 9600 PCR system (Perkin-Elmer) in a 25-μl total reaction volume, which was prepared with 5 μl of the cDNA solution, 1× PCR Buffer II (Perkin-Elmer), 1.0 μM each primer, and 0.6 U of Taq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer). The MgCl2 concentration was adjusted to 1.5 mM. The DNA amplification reactions included 94°C for 2 min, followed by amplification cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min for TNF-α, IL-1α, and IL-8, and β-actin. The annealing temperature for IL-1β was adjusted to 60°C. The reactions ended with an extension at 72°C for 6 min. TNF-α mRNA was amplified during 33 cycles, IL-1α mRNA was amplified during 26 cycles, IL-1β mRNA was amplified during 21 cycles, IL-8 mRNA was amplified during 18 cycles, and β-actin mRNA was amplified during 30 cycles. PCR fragments were separated in 1.5% agarose gels and visualized with ethidium bromide (37).

(iv) Sequence analysis.

Visualized DNA fragments were cut out from agarose gels and served as templates for a subsequent PCR amplification. Reamplified DNA fragments were purified and concentrated with the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Automated sequencing was performed (Applied Biosystems 373 DNA sequencer; Cornell Biotechnology), and readouts were compared to published canine sequences or, in the case of IL-1α, to published sequences from other species by using Lasergene Software (DNAStar, Madison, Wis.).

Bioassays for canine TNF and IL-1.

Canine cytokine activities were measured by cytotoxicity assays with cytokine-sensitive cell lines as described by Yamashita et al. (52) and Judd and MacLeod (15).

(i) TNF.

TNF-sensitive murine sarcoma cells (WEHI 164.S13) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, Md.) (ATCC CRL 1751). Cells were propagated in RPMI 1640 with 25 mM HEPES and l-glutamine (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.), 50 μg of gentamicin (Gibco BRL) per ml, and 10% FBS (Gibco BRL). Cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 72 h, and then they were scraped off for further propagation or tests. TNF was assayed in 96-well flat-bottomed plates, and all samples (diluted 1:10 in medium without phenol red) were tested in triplicate. A threefold dilution series of recombinant human TNF-α (rhTNF-α) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.), ranging in final concentration from 0.1 pg/ml to 25 ng/ml, served as a positive control. To achieve comparable conditions in the test samples and positive control, rhTNF-α was diluted in medium containing 80% RPMI 1640 without phenol red and 20% HBSS. Each test well contained 200 μl of medium (RPMI 1640 without phenol red and with 5% FBS), rhTNF-α or 1:10 diluted sample, and 10,000 cells. After 24 h, TNF activity was assessed by measuring cell viability with XTT (2,3-bis-[2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfo-phenyl]-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide inner salt) as described by Stevens and Olsen (43). Eighteen hours after the addition of XTT, the optical density of the culture supernatant was measured with a reader at λ1 = 490 nm and λ2 = 630 nm. TNF activities were calculated and expressed as rhTNF-α-like activities.

To demonstrate the specificity of this assay for TNF-α, samples with confirmed rhTNF-α-like activities were incubated with the same volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing a 10-μg/ml concentration of polyclonal antibodies raised against rhTNF-α (R&D Systems). Samples were incubated for 2 h on a shaker (200 rpm). Identical samples were incubated with the same volume of PBS. Subsequently, these samples were tested in the TNF bioassay.

(ii) IL-1.

An IL-1-sensitive human melanoma cell line, A275.S2, was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC CRL 1619). Cells were cultured in minimal essential medium with 50 μg of gentamicin (Gibco BRL) per ml and with 8% FBS. Confluent cell monolayers were obtained after 72 h when flasks were incubated at 37°C in humidified air with 5% CO2. For propagation and testing, cells were detached from the flask with trypsin (0.05%) and EDTA (0.025%) in a 0.9% sodium chloride solution. IL-1 testing was done in 96-well flat-bottomed plates as described for TNF testing. rhIL-1α (R&D Systems) was used as a positive control. The biologically active concentration ranged between 0.01 pg/ml and 2.5 ng/ml. Samples and positive controls were tested in minimal essential medium with gentamicin and with 5% FBS. Plates were incubated for 72 h before the medium was taken off, plates were washed twice with RPMI 1640 without phenol red, wells were filled with 200 μl of RPMI 1640 without phenol red and with 5% FBS, and XTT was added. Results were calculated as rhIL-1α-like activity.

To demonstrate the specificity of this assay for IL-1α, samples with confirmed rhIL-1α-like activities were incubated with the same volume of PBS containing a 10-μg/ml concentration of polyclonal antibodies raised against rhIL-1α (R&D Systems). Samples were incubated for 2 h on a shaker (200 rpm). Identical samples were incubated with the same volume of PBS. Subsequently, these samples were tested in the IL-1-bioassay.

Chemotactic activity of explant culture supernatants. (i) Chemotaxis assay.

PMNs were isolated from heparinized venous blood from healthy specific-pathogen-free beagles (James A. Baker Institute). Cells were isolated by Hypaque-Ficoll density gradient centrifugation as described previously (45). Migration of PMNs through polycarbonate filters (2-μm pore diameter) was measured in a 96-blind-well chamber system (Neuro Probe, Cabin John, Md.). Two chemotaxis systems were used: in initial studies we employed a regular 96-well chemotaxis system (100 μl of diluted test sample), but more recently we used the ChemoTX system (30 μl of diluted test sample). The two systems gave similar results. Samples were diluted 1:10 in HBSS and tested in duplicate. Recombinant canine IL-8 (rcIL-8) was used as a positive control. The number of migrated PMNs was determined indirectly by measuring the amount of liberated peroxidase colorimetrically as described elsewhere (45).

(ii) Effect of polyclonal antibodies to rcIL-8 on chemotaxis.

Explant supernatants with known chemotactic activity were incubated for 2 h at 37°C on a shaker at 200 rpm with polyclonal rabbit antiserum raised against rcIL-8 (45). Preimmune serum from the same rabbit served as a negative control. Previous experiments with rcIL-8 revealed an optimal blocking concentration of the serum at a dilution factor of 1:400. After the incubation period, samples were transferred into the wells of the chemotaxis unit, and the migration of PMNs was determined.

(iii) Checkerboard analysis.

In further experiments conducted to differentiate between directed chemotaxis and random chemokinesis of PMNs, both the lower wells and the upper compartments were filled with various concentrations of PMN migration-inducing supernatants. Wells in the lower compartment were filled with solutions containing 10, 4, 1.6, and 0% of a PMN migration-inducing supernatant. Similarly, wells in the upper compartment were filled with PMN suspensions also containing 10, 4, 1.6, and 0% of the same supernatant, but the setup of the upper plate was then rotated 90° relative to the lower plate to achieve the checkerboard effect. In total, migration responses to 16 different combinations were evaluated.

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting for canine IL-8.

Cell-free synovial explant culture supernatants were concentrated fivefold by lyophilization, and proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) in 15% polyacrylamide gels in an SE 600 gel apparatus (Hoefer Scientific Instruments, San Francisco, Calif.). Proteins were then transferred onto nylon membranes (Immobilon-P; Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) with a Hoefer TE 52× Transphor Unit at 25 V for 16 h. Membranes were blocked with bovine serum albumin (BSA) (3% in PBS) for 2 h at room temperature. After the incubation with a rabbit antiserum raised against rcIL-8 (diluted to 1:2,000 in PBS supplemented with 0.1% BSA) for 2 h at room temperature, membranes were exposed to biotin-labeled goat anti-rabbit antibodies (Cappel, Durham, N.C.) for 1 h at room temperature. Following the incubation with peroxidase-labeled avidin (Cappel) (1:2,000 in PBS-BSA) for 1 h at room temperature, the reaction was visualized by the use of the peroxidase substrate 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma). The molecular weights of the protein bands were estimated by use of prestained low-molecular-weight markers (Sigma) on the same gel. For direct identification of immunoreactive bands, a standard of purified rcIL-8 was also included on blots.

Histology.

At the time of harvest after 3, 6, 12, or 24 h of cocultivation, uninfected synovial tissues and tissues infected with untreated or UV light-treated B. burgdorferi were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, trimmed, embedded, cut, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) according to standard procedures.

Statistics.

Data from experiments 1 and 2 (explant tissues infected with high-passage untreated or UV light-irradiated B. burgdorferi) or from experiments 3 and 4 (explant tissues infected with low-passage untreated or UV light-irradiated B. burgdorferi) were combined. To eliminate outliers, Dixon’s criterion with a 5% error level was applied. Means and pooled standard deviations (SD) (SD = [(SS1 + SS2)/(n1 − n2 − 2)]1/2, where SS is sums of squares, n is the number of samples, and the index is the experiment number [38]) were calculated for each value. Standard errors (SE) were derived from SD. Single values were considered significantly different when they differed based on their approximate 95% confidence intervals (based on 2 × SE). Effects of neutralizing antibodies were investigated with paired samples. Differences were calculated and tested in one-sample t tests with a 95% confidence interval.

RESULTS

Synovial explant cultures.

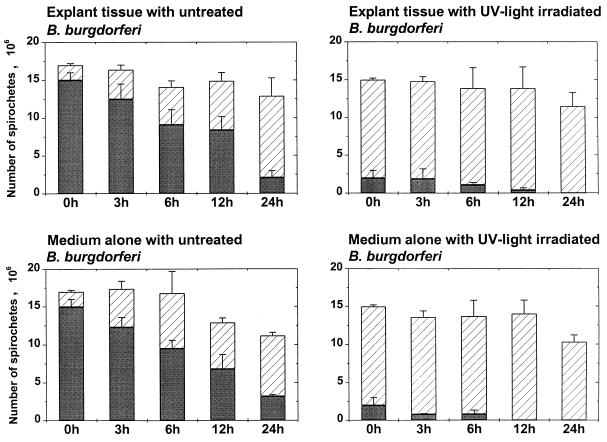

Synovial explant tissues from healthy dogs were cocultured with untreated, UV light-inactivated, or sonicated B. burgdorferi in HBSS for 3, 6, 12, and 24 h. A total of 1.4 × 107 to 2.6 × 107 spirochetes were added to each culture well containing medium with or without synovial explant tissues. Bacterial counts and viability were monitored in four experiments, where untreated and UV light-inactivated high-passage and low-passage borreliae were used. During the following 24-h observation period, the total number of spirochetes (sum of motile and nonmotile spirochetes) in the supernatants decreased gradually to 1.0 × 107 to 1.3 × 107 borreliae per well, a reduction of 24 to 34% (Fig. 1). During the same time period, the proportion of viable organisms decreased from initially 88% to 16 to 29% in cultures containing untreated spirochetes and from initially 13 to 0% in cultures containing UV light-inactivated spirochetes (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

B. burgdorferi in synovial explant tissue supernatants. Total numbers of spirochetes (motile plus nonmotile) in explant culture supernatants over 24 h, after an inoculation of 1.7 × 107 high-passage untreated or UV light-treated organisms (experiments 1 and 2), are shown. Solid bars, motile spirochetes; hatched bars, nonmotile spirochetes. Means and pooled SE from experiments 1 and 2 are shown.

Detection of mRNAs of TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-8 by RT-PCR.

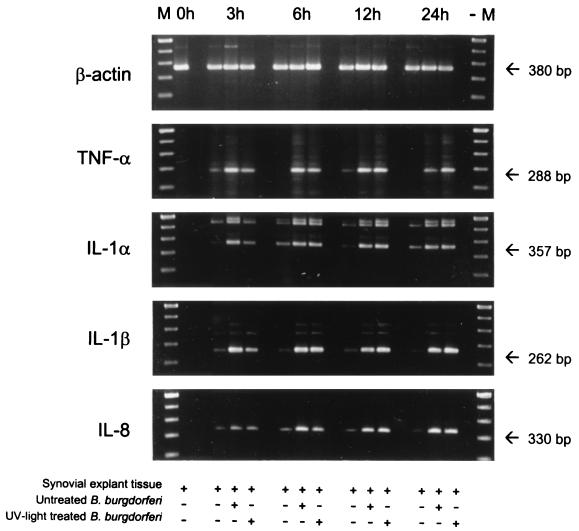

mRNAs for canine proinflammatory cytokines were detected by a semiquantitative RT-PCR. Equal amounts of total RNA were transcribed into cDNA, the resulting cDNA was amplified by PCR, and amplified fragments were visualized by gel electrophoresis. Sequence analysis showed that signals for β-actin, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8 were identical to published sequences. An IL-1α fragment, which was amplified with primers annealing to consensus sequences derived from different species and which was shorter than the expected fragment, showed 81.9% homology to bovine IL-1α. Canine β-actin served as an internal control to monitor the amount of RNA present in each experiment and was detected in similar amounts in all samples tested. Figure 2 shows a typical cytokine pattern for one experiment (experiment 2) with high-passage untreated and high-passage UV light-treated B. burgdorferi. When experiments were initiated (t = 0 h), no mRNA for any cytokine was detected. After 3 h of cultivation, a slight up-regulation of mRNAs of all cytokines was detected in uninfected explant tissues, which was observed throughout the 24-h cultivation period. Explant tissues infected with untreated, motile borreliae responded by 3 h with a pronounced up-regulation of TNF-α, IL-1α, and IL-1β. Tissues challenged with UV light-irradiated B. burgdorferi mounted a weaker response at 3 h. After 6, 12, and 24 h of incubation, bands with similar intensities were observed in samples from both systems. IL-8 mRNA up-regulation increased over time in tissues exposed to untreated borreliae, reaching its maximum after 6 h and staying elevated thereafter. Again, explant tissues cocultivated with UV light-treated B. burgdorferi responded slower, reaching maximal IL-8 mRNA levels after 12 h of cocultivation. No difference between high-passage and low-passage borreliae was noticed (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

mRNA levels in synovial explant tissues. A semiquantitative assessment of canine cytokine mRNAs in synovial explant tissues which were exposed to high-passage untreated or UV light-treated B. burgdorferi (experiment 2) is shown. RT-PCR-amplified mRNAs were separated on agarose gels, and signals of cytokine-specific mRNAs were compared to signals of β-actin mRNA. Lanes M, molecular size markers. In synovial explant tissues, mRNAs of all tested cytokines were up-regulated after 3 h of coincubation with untreated or UV light-treated B. burgdorferi. Note that IL-8 mRNA was up-regulated more slowly and reached maximal levels after 6 h. Tissues exposed to UV light-irradiated spirochetes responded more slowly and reached maximal cytokine mRNA levels with a 3-h delay compared to tissues infected with untreated B. burgdorferi.

Synovial explant tissues cultured with sonicated B. burgdorferi showed a response in mRNA up-regulation that was similar to that of explant tissues with UV light-treated borreliae (data not shown). However, their response appeared to be more delayed. Maximal levels of TNF-α and IL-1α mRNAs were detected after 6 h of cocultivation, whereas IL-1β mRNA increased steadily during the first 12 h to reach maximum levels at 12 and 24 h. IL-8 mRNA was detectable at low levels in 6-h samples. Afterwards, the level of up-regulation increased, and it was maximal at 24 h of cocultivation with sonicated spirochetes.

Bioassays for TNF and IL-1.

TNF and IL-1 activities in culture supernatants were measured with a cytotoxicity assay using cytokine-sensitive WEHI 164.S13 and A275.S2 cells, respectively. Activities were expressed as rhTNF-α-like and rhIL-1α-like activities, since rhTNF-α and rhIL-1α were used as the positive controls and specific neutralizing antibodies against canine TNF and IL-1 were not available.

(i) TNF.

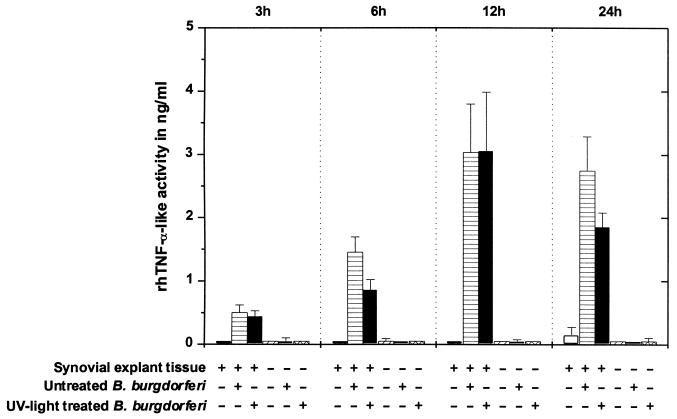

In experiments 1 and 2, synovial explant tissues were infected with high-passage untreated or UV light-treated B. burgdorferi (Fig. 3). Synovial explant tissues alone released no substances with TNF activities during the first 12 h of cultivation, while at 24 h, minimal rhTNF-α-like activities were detected. In contrast, synovial explant tissues exposed to untreated or UV light-treated B. burgdorferi released increasing amounts of rhTNF-α-like factors into supernatants over a 12-h incubation period. TNF activities dropped after 24 h but did not differ statistically from the 12-h data. Medium alone or with spirochetes had no effect on TNF-sensitive cells (P > 0.05). No difference between the effects induced by high-passage and low-passage B. burgdorferi was noticed (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

rhTNF-α-like activity in supernatants of synovial explant cultures exposed to high-passage untreated or UV light-treated B. burgdorferi (experiments 1 and 2). In each test plate, the effects of culture supernatants on a TNF-sensitive cell line (WEHI 164.S13) were compared to a standard curve obtained with a serial dilution of rhTNF-α. Means and pooled SE from experiments 1 and 2 are shown.

Sonicated B. burgdorferi also induced the release of TNF-like substances in synovial explant tissues. rhTNF-α-like activity values were in general lower, but the same pattern of TNF activity over time as in previous experiments was seen. Supernatants from cultures with explant tissues and untreated spirochetes contained the following TNF activities: 0.15 ± 0.15 ng/ml at 3 h, 0.57 ± 0.21 ng/ml at 6 h, 1.02 ± 0.09 ng/ml at 12 h, and 0.85 ± 0.36 ng/ml at 24 h. Supernatants with sonicated organisms showed the following activities: 0.30 ± 0.20 ng/ml at 3 h, 0.26 ± 0.10 ng/ml at 6 h, 0.46 ± 0.20 ng/ml at 12 h, and 0.43 ± 0.25 ng/ml at 24 h.

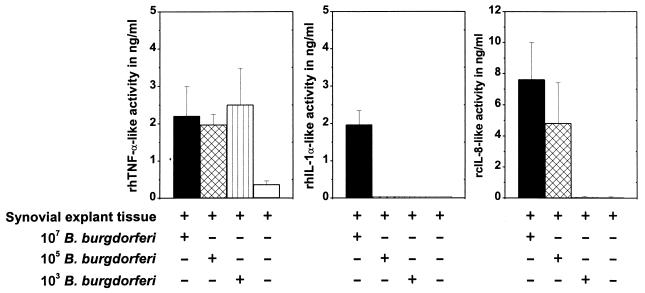

TNF activities in 6-, 12-, and 24-h supernatants from explant cultures receiving 103, 105, or 107 spirochetes did not differ significantly (Fig. 4) (P > 0.05). TNF activity was up-regulated as in previous experiments and reached maximum values after 12 and 24 h of cocultivation (between 1.98 ± 0.27 and 2.51 ± 0.98 ng of rhTNF-α-like activity per ml). Only after 3 h was a dose-dependent rhTNF-α-like response noticed (0.19 ± 0.06 ng/ml with 107 borreliae, 0.11 ± 0.06 ng/ml with 105 borreliae, and 0.07 ± 0.02 ng/ml with 103 borreliae per explant).

FIG. 4.

Effects of various numbers of B. burgdorferi. rhTNF-α-like, rhIL-1-like, and rcIL-8-like activities (chemotactic activities) in supernatants of synovial explant cultures challenged with 107, 105, and 103 untreated spirochetes for 24 h (experiment 6) are shown. Note the dose-independent up-regulation of TNF activity, the unresponsiveness of synovial tissues to low numbers of B. burgdorferi in the case of IL-1, and the dose-dependent induction of chemotactic activities.

Antibodies raised against rhTNF-α were used to demonstrate the specificity of the putative TNF-like activities in explant supernatants. A 5-μg/ml antibody solution reduced the effect of rhTNF-α by 100% when rhTNF-α was used at a concentration of below 0.01 ng/ml. When rhTNF-α was used at concentrations of between 0.01 and 1.0 ng/ml, the efficacy in inhibiting TNF-α-like activity with antibodies dropped gradually to 10%. The same antibody solution reduced the TNF-like activity in 1:10-diluted explant supernatants on average by 32% (P < 0.0001; maximal inhibition, 85%).

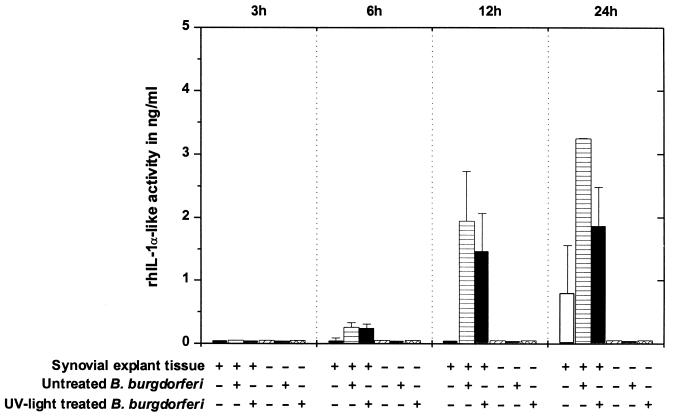

(ii) IL-1.

Aliquots of the same supernatants that were tested for TNF activity were screened for IL-1 activity. The combined results of two experiments (experiments 1 and 2) with high-passage untreated and high-passage UV light-treated B. burgdorferi are shown in Fig. 5. The IL-1 assay did not distinguish between IL-1α and IL-1β. After 3 h of cultivation, no rhIL-1α-like activity was detected in any synovial explant tissues. At 6 h, supernatants from synovial explant tissues exposed to untreated or irradiated spirochetes showed little rhIL-1α-like activity when uninfected tissues did not. During the following 18 h of co-cultivation, the rhIL-1α-like activity increased significantly over background values in cultures with explant tissues exposed to untreated borreliae and to a lesser concentration in cultures with explant tissues exposed to UV light-treated borreliae. At 24 h, supernatants of explant tissues alone produced an rhIL-1α-like activity of 0.80 ± 0.76 ng/ml, which because of a high SD did not differ significantly from that of cultures with explant tissue exposed to UV light-treated borreliae (P > 0.05). Medium alone or with spirochetes did not exhibit any rhIL-1α-like activity. Supernatants of explant cultures with high-passage and low-passage borreliae did not differ in their patterns and magnitudes of rhIL-1α-like activity (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

rhIL-1α-like activities in supernatants of synovial explant cultures where tissues were exposed to high-passage untreated or UV light-treated B. burgdorferi (experiments 1 and 2). In each test plate, the effects of culture supernatants on an IL-1-sensitive cell line (A375.S2) were compared to a standard curve obtained with a serial dilution of rhIL-1α. Means and pooled SE from experiments 1 and 2 are shown.

Sonicated borrelia cultures caused an IL-1-like response similar to that with untreated borrelia cultures. In detail, rhIL-1α-like activity was detected in 12-h samples (0.47 ± 0.20 ng/ml) and in 24-h samples (4.51 ± 1.36 ng/ml). In the same experiment, untreated borreliae induced rhIL-1α-like activity of 0.81 ± 0.06 and 3.81 ± 0.94 ng/ml after 12 and 24 h of cocultivation with synovial explant tissues, respectively.

Synovial explant tissues were very unresponsive in terms of IL-1 release to low numbers of spirochetes added to the culture medium. In the titration experiment, only an inoculum of 107 untreated spirochetes per tissue induced the release of IL-1-like substances (0.54 ± 0.13 ng/ml at 12 h and 1.97 ± 0.37 ng/ml at 24 h). No rhIL-1α-like activity was detected in cultures with 105 and 103 B. burgdorferi organisms per synovial explant tissue (Fig. 4).

Since neutralizing antibodies against canine IL-1α and IL-1β were not available, explant culture supernatants were incubated with polyclonal antibodies against rhIL-1α. A 5-μg/ml antibody solution reduced the effect of rhIL-1α by more than 95% when rhIL-1α was used at a concentration of below 0.5 ng/ml. When supernatants from explant cultures were tested, IL-1-like activity was minimally reduced, and only a few samples (1:10 dilutions) showed reductions of up to 35% (P = 0.25).

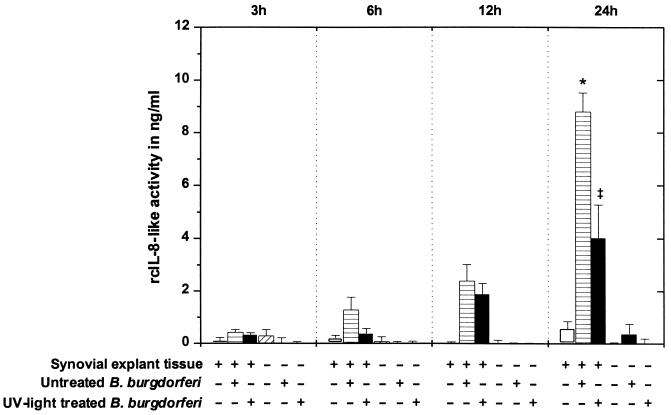

Chemotactic activity of explant culture supernatants.

Synovial explant culture supernatants were tested for their ability to induce the migration of PMNs from normal beagles through polycarbonate filters in vitro. No difference in migration behavior was seen when a regular 96-well chemotaxis system with a large sample volume was used or when the Chemo TX system, which needs only a third of the sample volume, was used. Combined results from experiments 1 and 2 with high-passage untreated and high-passage UV light-treated B. burgdorferi are shown in Fig. 6. No chemotactic activity was detected in supernatants from 3-h cultures. After 6 h of cultivation, only cultures with untreated spirochetes showed slight chemotaxis which differed significantly from background levels (P < 0.05). Chemotactic activity increased gradually in supernatants of synovial explant tissues with untreated and UV light-treated borreliae during the following 18 h of cultivation. After 24 h, maximal concentrations were reached in cultures with untreated and UV light-treated B. burgdorferi, which differed significantly (P < 0.05). Similar results were obtained from explant experiments utilizing low-passage B. burgdorferi (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

PMN migration induced by explant culture supernatants. Chemotaxis of PMNs toward supernatants of synovial explant cultures where tissues were exposed to high-passage B. burgdorferi (experiments 1 and 2) is shown. In each test plate, the chemotactic effects of culture supernatants on canine PMNs were compared to a standard curve obtained with a serial dilution of rcIL-8. Means and pooled SE from experiments 1 and 2 are shown. After 24 h, activities in cultures where synovial explant tissues were exposed to untreated B. burgdorferi (∗) differed significantly from those in cultures where explant tissues were challenged with UV light-irradiated spirochetes (‡) (P < 0.05).

When sonicated borreliae were used, no differences were noted between untreated and sonicated borreliae (P > 0.05). The two spirochete preparations produced comparable levels of rcIL-8-like activity, which increased in a time-dependent pattern. Measurable concentrations appeared in 12-h samples, with 3.79 ± 0.38 and 3.89 ± 0.48 ng/ml, and in 24-h samples, with 5.84 ± 0.68 and 6.53 ± 0.21 ng/ml, in explant cultures with untreated and sonicated borreliae, respectively.

Titration of B. burgdorferi revealed a dose-dependent chemotaxis response. An inoculum of 107 induced maximal chemotactic activities, while explant tissues were unresponsive to 103 spirochetes (Fig. 4).

Supernatants from explant cultures with proven PMN migration-inducing activities were incubated with polyclonal antibodies against rcIL-8. A 1:400 dilution of the hyperimmune serum against rcIL-8 reduced the original chemotactic activity of a 1:20-diluted sample by up to 65%. The same antibody solution reduced the chemotactic effect of rcIL-8 by more than 80% when the chemokine was used in concentrations of below 5.0 ng/ml. Antibody solutions alone had no effect on the migration behavior of PMNs.

To demonstrate that PMNs migrated actively along a gradient of a chemoattractant substance (chemotaxis) rather than randomly in an undirected fashion (chemokinesis), a checkerboard analysis with various concentrations of PMN migration-inducing supernatants present in the upper and lower compartments was performed (Table 2). A combination of 10% explant supernatant in the lower compartment and 0% in the upper compartment represented the standard protocol of the chemotaxis assay. Equal amounts (10%) of supernatants in the upper and lower compartments induced PMN migration, but because a chemotactic gradient was missing, the migration toward the lower compartment was reduced by 26% when values were compared to values generated with the standard protocol. However, 1.6 and 4.0% explant supernatant added to the upper compartment activated PMNs more efficiently and increased the PMN migration toward the lower compartment by 51 and 47%, respectively. Reduced concentrations of explant supernatants in the lower wells (4.0, 1.6, and 0%) induced a weaker response of PMNs, which ranged between 0 and 28% of the values generated with the standard protocol.

TABLE 2.

Checkerboard analysisa

| Concn (%) of migration-inducing supernatant in lower wells | Relative PMN migration with the following concn (%) of migration-inducing supernatant in upper wells:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.6 | 4.0 | 10.0 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.16 |

| 1.6 | 0 | 0 | 0.06 | 0.10 |

| 4.0 | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.28 | 0.13 |

| 10.0 | 1 | 1.51 | 1.47 | 0.74 |

PMN migration induced with various concentrations of migration-inducing supernatants in the upper and lower compartments of the chemotaxis chamber was compared to PMN migration obtained with the standard protocol, which was assigned a value of 1.

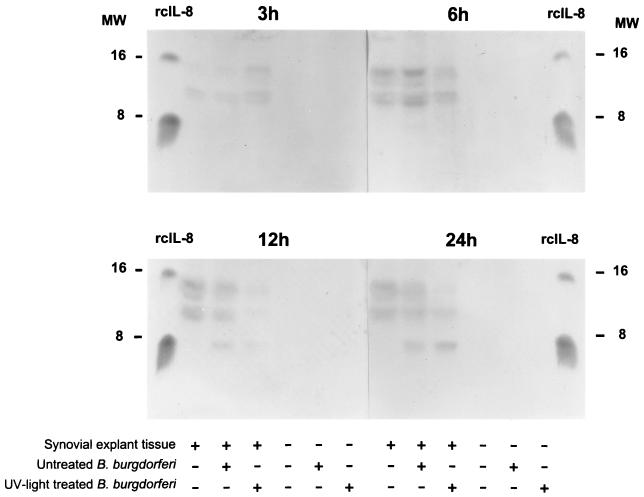

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting for canine IL-8.

Concentrated supernatants from two synovial explant experiments (high and low passage) were subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis, and membrane-bound proteins were incubated with polyclonal antibodies raised against rcIL-8. One blot (from experiment 1 with high-passage borreliae) is shown in Fig. 7. After 3 and 6 h of cocultivation, no detectable concentrations of canine IL-8 were present in any samples. After an additional 6 h, samples of synovial explant tissues with untreated borreliae showed a band in the range of 8 kDa, which was identical in size to rcIL-8. A less prominent band was visible in the lane which contained the sample of explant tissue in combination with UV light-treated borreliae. The 24-h samples revealed stronger bands for IL-8 in both samples where synovial explant tissues were challenged with untreated or UV light-treated B. burgdorferi. Additional bands were visible between 10 and 15 kDa, which appeared in all test samples containing synovial explant tissues regardless of the spirochete challenge. Since hyperimmune serum was used, these bands can be interpreted as nonspecific signals of unknown origin.

FIG. 7.

Western blot for canine IL-8. Supernatants of synovial explant cultures exposed to high-passage untreated or UV light-treated B. burgdorferi (experiment 1) were separated on a gel, blotted, and then probed with polyclonal antibodies raised in rabbits against rcIL-8. A weak specific signal for IL-8 (8-kDa region) is visible in 12-h cultures where synovial tissues were exposed to untreated spirochetes and in 24-h cultures where synovial tissues were exposed to untreated or UV light-irradiated spirochetes. MW, molecular weight in thousands.

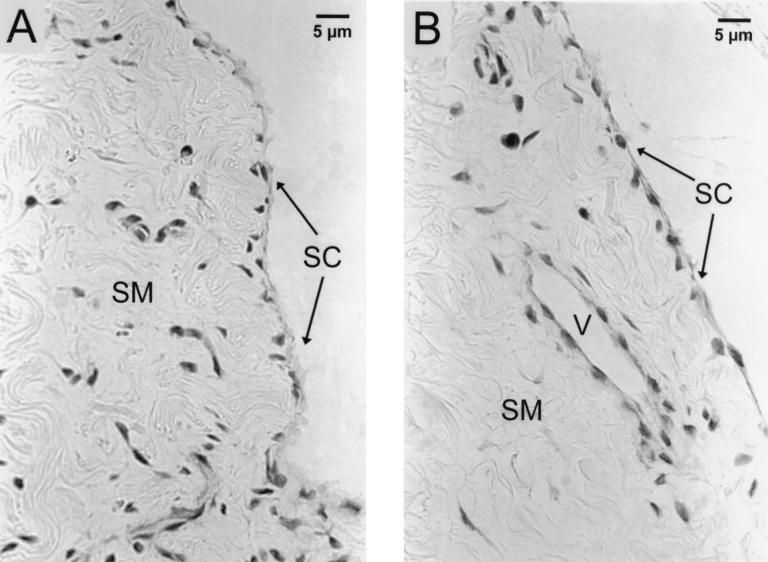

Histology.

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded, and H&E-stained tissues were examined by light microscopy (Fig. 8). During a 24-h period of incubation in HBSS, explant tissues retained remarkable integrity and expressed only minor signs of deterioration. Explant surfaces were covered with one or two layers of synoviocytes. The stroma of the explant tissues contained collagenous connective tissue with fibrocytes, blood vessels, and islands of adipose tissue. The blood vessels were mostly capillaries, with infrequent small arterioles. Surprisingly, some vessels contained intact erythrocytes. Below the synoviocyte layer, a few degenerating cells with pyknotic nuclei were found in all examined tissues. No histological differences between control tissues and tissues cocultured with B. burgdorferi were noted. Spirochetes are not visible in H&E-stained tissues.

FIG. 8.

Histology of 24-h samples. H&E-stained sections of synovial explant tissues cocultured without (A) or with (B) spirochetes for 24 h are shown. One or two layers of synoviocytes (SC) cover the surface of synovial membrane tissue (SM). The stroma contains collagenous connective tissue with fibrocytes and blood vessels (V). Note that B. burgdorferi organisms are not visible in H&E-stained sections.

DISCUSSION

The clinical onset of Lyme arthritis in humans and dogs is typically abrupt. When histological and cytological examinations of synovial membranes and synovial fluids from affected joints are made, a massive influx of PMNs into the joint cavity is evident (1, 10). PMNs and other cells do not invade tissues randomly but do so in response to distinct signals which ultimately will induce their migration from blood vessels through tissue and into the joint cavity. Our in vivo studies with dogs (45) have shown that B. burgdorferi is present in inflamed joints and that IL-8, a strong chemoattractant for PMNs, is involved in the pathogenesis of the disease. This prompted us to investigate the interaction of B. burgdorferi with synovial membranes in vitro. We have chosen to use canine synovial explant tissue cultures rather than isolated cell populations or specific cell lines, which represent only single cell populations and, further, would not allow any feedback mechanisms between different cell types. In addition, explant cultures provide a natural three-dimensional structure, which remained histologically intact throughout the 24-h incubation period. This system allowed cell-to-cell communication but excluded the effects of blood-borne factors such as antibodies, complement, and leukocytes. The kinetics of proinflammatory cytokines, e.g., TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-8, were investigated, because the predominance of PMNs in inflamed tissues during acute phases of the natural occurring disease points to the involvement of those factors.

In five experiments, each synovial explant tissue culture was infected with 107 or more spirochetes. This number of spirochetes exceeds by far the number of spirochetes naturally found in infected tissues. B. burgdorferi is difficult to demonstrate by either culture or PCR in clinical specimens (3, 35), suggesting that the number of organisms is low in vivo. We intended to simulate extreme conditions in vitro, and our titration experiment demonstrated that a high number of spirochetes resulted in the maximal production and release of all the cytokines that we investigated. Under the assumption that a 5- by 5-mm synovial explant membrane contains 106 to 107 cells (a cell volume of 103 to 104 μm3 is assumed), a cell/spirochete ratio of more than 1.0 was achieved. This is in accordance with results from Defosse and Johnson (8), Kenefick et al. (18), and Burns et al. (6), who demonstrated that a cell/spirochete ratio of 1:1 or greater induced a TNF-α or IL-1 response in mononuclear cells or umbilical endothelial cells in vitro.

Since B. burgdorferi moves actively in culture media and apparently migrates in tissues as well (45), we investigated the effects of motile borreliae compared to those of UV light-irradiated or sonicated borreliae on synovial explant tissues. During the 24-h incubation period, the number of spirochetes in culture supernatants dropped by a maximum of 34%, which may be the result of sedimentation, because controls without explant tissues showed a similar reduction in number. During the same time, the viability of the organisms declined also. This is not surprising, since HBSS is not a complete medium in which to propagate B. burgdorferi organisms. When UV light-irradiated B. burgdorferi organisms were examined by dark-field microscopy, they appeared to have extremely reduced or no motility but retained their cellular integrity, preventing the release of large intracellular components into the medium.

TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-8 activities in culture supernatants were preceded by the up-regulation of their specific mRNAs in tissues. Synovial explant tissues responded quickly to the challenge with motile B. burgdorferi. Within 3 h of coincubation, tissues exposed to untreated spirochetes had maximal TNF-α, IL-1α, and IL-1β mRNA levels. However, maximal IL-8 mRNA levels appeared after 6 h of coincubation. Tissues exposed to UV light-irradiated spirochetes showed a delayed up-regulation of their cytokine mRNAs, with maximal mRNA levels found only after 6 h of exposure. Considering that within any single experiment all explant tissues received the same number of spirochetes, it appears likely that the lack of motility and therefore a lack of invasiveness accounts for the delayed cytokine up-regulation, which paralleled very well the biological activity of all cytokines investigated.

The levels of biologically active TNF-like and IL-1-like factors did not reveal any statistically significant differences between untreated, UV light-irradiated, and sonicated borreliae at all time periods of the explant cultures. However, migration of PMNs toward culture supernatants was the highest for cultures containing synovial explant tissues exposed to untreated or sonicated spirochetes. UV light-irradiated B. burgdorferi, on the other hand, induced a significantly smaller chemotactic response. Since the same number of spirochetes was added to all cultures and no differences between TNF- and IL-1-like activity levels were observed, titration effects can be excluded. The only difference between the untreated and UV light-irradiated borreliae that we were aware of was the lack of motility, while the lack of cell integrity distinguished between untreated and sonicated borreliae. Surprisingly, sonicated borreliae induced the same chemotactic response as untreated spirochetes. The chemotactic factor(s) generated from the explant cultures is thought to be a chemokine such as IL-8, and presumably it can be induced by B. burgdorferi proteins as well as by intact, motile organisms. Why the addition of sonicated spirochetes to synovial explant tissues generated more chemotaxis than UV-light irradiated spirochetes is unknown, but it is possible that the sonication of spirochetes causes the release of additional chemotaxis-inducing factors.

In addition to contrasting the cytokine-inducing properties of untreated, irradiated, and sonicated borreliae, we compared the activities of high- and low-passage organisms. High- and low-passage B. burgdorferi induced cytokine responses of the same magnitude in our in vitro system. Kenefick et al. did not see passage-dependent effects on the production of IL-1 when B. burgdorferi was coincubated with peritoneal exudate cells or bovine peripheral blood monocytes (17, 18). It is interesting that both studies show that high-passage borreliae retain cytokine-inducing activities. It is possible, however, that those differences between high- and low-passage organisms will not be evident in in vitro systems which test activities over a 24-h period.

When the number of spirochetes added to the synovial explant cultures was varied, an effect was noted with some cytokines but not with others. A wide range of spirochete numbers induced similar TNF-like activities in synovial tissue cells. One thousand bacteria per tissue and a 104-fold higher bacterial load induced comparable TNF responses. In contrast, only the maximal number of borreliae (107) produced a substantial IL-1-like effect after 12 and 24 h of coincubation with synovial tissues. IL-8-like activities were directly related to the dose of organisms added. An inoculum of 1,000 organisms induced no measurable IL-8-like activities. Considering the development of arthritis, these observations would favor an early release of TNF, which seems to be easily and quickly triggered by small numbers of spirochetes. In contrast, IL-8 appeared with a delay of at least 3 h, possibly triggered indirectly by TNF-α and/or directly by an interaction between synovial membrane cells and spirochetes. Other groups have shown that either pathway can lead to the up-regulation of IL-8. Eckmann et al. (9) have demonstrated that epithelial cells and fibroblasts respond with the production and release of IL-8 upon penetration by bacteria. In addition, in a recent publication by Burns et al. (6), it was shown that IL-8 is produced by umbilical endothelial cells in response to B. burgdorferi but independently of the secretion of IL-1 and TNF-α. Data published by Schröder et al. (39) show clearly that TNF-α can induce the production and release of IL-8 from fibrocytes. With regard to IL-1 production, synovial explant tissues responded only to an inoculum of 107 or more spirochetes, suggesting that IL-1 is released at times when synovial membranes might harbor large numbers of spirochetes, such as during advanced, untreated infection.

We observed significant IL-1-like activity, but we were not able to discriminate further whether canine IL-1α and/or IL-1β accounted for these activities, due to the lack of specific neutralizing antibodies. Antibodies against IL-1 were directed against the human cytokine, and it is possible that this preparation lacked sufficient cross-reactivity to block the effect of canine IL-1α. However, we could demonstrate that IL-1α and IL-1β mRNA levels were up-regulated when synovial tissues were exposed to B. burgdorferi. TNF-α and IL-8 were confirmed to be present in culture supernatants by the reduction of their biological activities by neutralizing antibodies, by Western blotting (only IL-8), and by the up-regulation of their specific mRNAs. Biological activities of TNF-α and IL-8 were abrogated incompletely when supernatants were treated with antibodies to these cytokines. The failure of the neutralizing antibodies to totally abrogate cytokine activity can have several reasons. In the case of TNF-α, an insufficient interspecies cross-reactivity may have prevented complete blocking. In the case of IL-8, where we used species-specific hyperimmune serum, additional factors, released from the explant tissues by the infection (28), may have contributed to the residual cytokine activities. Leukotriene B4 can induce the chemotaxis of PMNs and was also found in synovial fluids from patients with Lyme disease (26). In a complex system like an explant culture, the release of multiple mediators must be expected, and it is likely that in patients with Lyme arthritis, these factors may also contribute to the initiation, maintenance, or termination of joint inflammation. There is still uncertainty which factor(s) actually induces PMN chemotaxis in vivo. Contradictory experimental results were obtained for TNF-α and IL-1α: there are reports which indicate some chemotactic activity for IL-1α (48, 49), while others deny any chemotactic activity for IL-1α or TNF-α (29). In our experiments, chemotactic activities were not related to TNF-like activities or IL-1-like activities. While elevated TNF-like activities were observed within 3 and 6 h after cocultivation of explant tissues with borreliae, no significant chemotactic activities were noted at that time. Similarly, 24-h culture supernatants of explant tissues which received untreated or UV light-irradiated spirochetes expressed levels of IL-1-like activities that were not significantly different, but their chemotaxis indices differed significantly, by more than two SE units. Similarly, we observed chemotactic activities in cultures which had received 105 spirochetes, but identical samples showed no IL-1-like activity. Thus, chemotactic activity in explant culture supernatants is ascribed to IL-8; whether IL-8 production was triggered by the spirochete alone or by an earlier-up-regulated cytokine will require further study.

Our hypothesis of the pathogenesis of acute Lyme arthritis emphasizes the involvement of local inflammatory factors and PMNs. However, studies by Schell and colleagues have concentrated on the involvement of borreliacidal antibodies and T lymphocytes (CD4+ and CD8+) in the pathogenesis of Lyme disease (21–23). In our opinion, T-lymphocyte-mediated Lyme arthritis differs from the initial arthritis that we see in tick-induced experimental canine infection. In our dogs, an accumulation of lymphocytes and plasma cells in the synovial membrane occurs after several months of infection (1). Only very small amounts of borreliacidal antibodies are present at this time, and the nonsuppurative arthritis is subclinical (44).

Diverse and sometimes contradictory information exists regarding the development of Lyme arthritis; a detailed characterization of the pathogenesis will be essential for successful treatment and the development of safe vaccines. Data describing the regulation and kinetics of cytokines and specific immune factors are difficult to obtain in vivo. Our explant tissue culture system allows the study of complex mechanisms without scarifying the structure of the synovial tissue. Feedback mechanisms can develop and can be studied in detail, which makes this system a valuable tool for the further study of Lyme arthritis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (contract N01-AI-45254) and by the Gottlieb Daimler- und Karl Benz-Stiftung, Ladenburg, Germany.

We thank Mary Beth Matychak for her excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Appel M J G, Allen S, Jacobson R H, Lauderdale T-L, Chang Y-F, Shin S J, Thomford J W, Todhunter R J, Summers B A. Experimental Lyme disease in dogs produces arthritis and persistent infection. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:651–664. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.3.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baggiolini M, Dewald B, Moser B. Interleukin-8 and related chemotactic cytokines—CXC and CC chemokines. Adv Immunol. 1994;55:97–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbour A G. Laboratory aspects of Lyme borreliosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1988;1:399–414. doi: 10.1128/cmr.1.4.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barthold S W, DeSouza M S, Janotka J L, Smith A L, Persing D H. Chronic Lyme borreliosis in the laboratory mouse. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:959–971. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beck G, Benach J L, Habicht G S. Isolation of interleukin 1 from joint fluids of patients with Lyme disease. J Rheumatol. 1989;16:800–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burns M J, Sellati T, Teng J, E I, Furie M B. Production of interleukin-8 (IL-8) by cultured endothelial cells in response to Borrelia burgdorferi occurs independently of secretion IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor alpha and is required for subsequent transendothelial migration of neutrophils. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1217–1222. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1217-1222.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang Y-F, Straubinger R K, Jacobson R H, Kim J B, Kim T J, Kim D, Shin S J, Appel M J G. Dissemination of Borrelia burgdorferi after experimental infection in dogs. J Spirochetal Tick-Borne Dis. 1996;3:80–86. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Defosse D L, Johnson R C. In vitro and in vivo induction of tumor necrosis factor alpha by Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1109–1113. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.1109-1113.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eckmann L, Kagnoff M F, Fierer J. Epithelial cells secrete the chemokine interleukin-8 in response to bacterial entry. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4569–4574. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.11.4569-4574.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Georgilis K, Noring R, Steere A C, Klempner M S. Neutrophil chemotactic factors in synovial fluids of patients with Lyme disease. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:770–775. doi: 10.1002/art.1780340620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilmore, W. H., S. D. Carter, M. Bennett, A. Barnes, and D. F. Kelly. 1996. Expression of canine TNF, IL-1 and IL-6 mRNAs in peripheral blood monocytes and cell lines. GenBank accession no. Z70047.

- 12.Hulinska D, Jirous J, Valesova M, Herzogova J. Ultrastructure of Borrelia burgdorferi in tissues of patients with Lyme disease. J Basic Microbiol. 1989;29:73–83. doi: 10.1002/jobm.3620290203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hurtenbach U, Museteanu C, Gasser J, Schaible U E, Simon M M. Studies on early events of Borrelia burgdorferi-induced cytokine production in immunodeficient SCID mice by using a tissue chamber model for acute inflammation. Int J Exp Pathol. 1995;76:111–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishikawa J, Suzuki S, Hotta K, Hirota Y, Mizuno S, Suzuki K. Cloning of a canine gene homologous to the human interleukin-8-encoding gene. Gene. 1993;131:305–306. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90313-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Judd A M, MacLeod R M. The regulation of interleukin 6 and tumor necrosis factor release from primary cultures of ovarian cells. Prog Neuroendocrinoimmunol. 1992;5:245–255. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keane-Myers A, Nickell S P. Role of IL-4 and IFN-gamma in modulation of immunity to Borrelia burgdorferi in mice. J Immunol. 1995;155:2020–2028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kenefick K B, Lederer J A, Schell R F, Czuprynski C J. Borrelia burgdorferi stimulates release of interleukin-1 activity from bovine peripheral blood monocytes. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3630–3634. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.9.3630-3634.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kenefick K B, Lim L C L, Alder J D, Schmitz J L, Czuprynski C J, Schell R F. Induction of interleukin-1 release by high- and low-passage isolates of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1086–1092. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.5.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knigge H, Simon M M, Meuer S C, Kramer M D, Wallich R. The outer surface lipoprotein OspA of Borrelia burgdorferi provides co-stimulatory signals to normal human peripheral CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2299–2303. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leong S R, Flaggs G M, Lawman M, Gray P W. The nucleotide sequence for the cDNA of bovine interleukin-1α. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:9053. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.18.9053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim L C L, England D M, DuChateau B K, Glowacki N J, Creson J R, Lovrich S D, Callister S M, Jobe D A, Schell R F. Development of destructive arthritis in vaccinated hamsters challenged with Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2825–2833. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.2825-2833.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim L C L, England D M, DuChateau B K, Glowacki N J, Schell R F. Borrelia burgdorferi-specific T lymphocytes induce severe destructive Lyme arthritis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1400–1408. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1400-1408.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim L C L, England D M, Glowacki N J, DuChateau B K, Schell R F. Involvement of CD4+ T lymphocytes in induction of severe destructive Lyme arthritis in inbred LSH hamsters. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4818–4825. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4818-4825.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma Y, Weis J J. Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface lipoproteins OspA and OspB possess B-cell mitogenic and cytokine-stimulatory properties. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3843–3853. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.9.3843-3853.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.May C, Carter S D, Barnes A, McLean C, Bennett D, Coutts A, Grant C K. Borrelia burgdorferi infection in cats in the UK. J Small Anim Pract. 1994;35:517–520. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayatepek E, Hassler D, Maiwald M. Enhanced levels of leukotriene B4 in synovial fluid in Lyme disease. Mediators Inflamm. 1993;2:225–228. doi: 10.1155/S0962935193000304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller L C, Lynch E A, Isa S, Logan J W, Dinarello C A, Steere A C. Balance of synovial fluid IL-1β and IL-1 receptor antagonist and recovery from Lyme arthritis. Lancet. 1993;341:146–148. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller M D, Krangel M S. Biology and biochemistry of the chemokines: a family of chemotactic and inflammatory cytokines. Crit Rev Immunol. 1992;12:17–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mulder K, Colditz I G. Migratory responses of ovine neutrophils to inflammatory mediators in vitro and in vivo. J Leukocyte Biol. 1993;53:273–278. doi: 10.1002/jlb.53.3.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishida T, Nishino N, Takano M, Kawai K, Bando K, Masui Y, Nakai S, Hirai Y. cDNA cloning of IL-1α and IL-1β from mRNA of U937 cell line. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;143:345–352. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90671-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nishida T, Nishino N, Takano M, Sekiguchi Y, Kawai K, Mizuno K U, Nakai S, Masui Y, Hirai Y. Molecular cloning and expression of rat interleukin-1α cDNA. J Biochem. 1989;105:351–357. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Norgard M V, Arndt L L, Akins D R, Curetty L L, Harrich D A, Radolf J D. Activation of human monocytic cells by Treponema pallidum and Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins and synthetic lipopeptides proceeds via a pathway distinct from that of lipopolysaccharide but involves the transcriptional activator NF-κB. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3845–3852. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3845-3852.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parker J L, White K K. Lyme borreliosis in cattle and horses: a review of the literature. Cornell Vet. 1992;82:253–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Porat R, Poutsiaka D D, Miller L C, Granowitz E V, Dinarello C A. Interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor blockade reduces endotoxin and Borrelia burgdorferi-stimulated IL-8 synthesis in human mononuclear cells. FASEB J. 1993;6:2482–2486. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.7.1532945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Preac-Mursic V, Patsouris E, Wilske B, Reinhardt S, Gross B, Mehraein P. Persistence of Borrelia burgdorferi and histopathological alterations in experimentally infected animals. A comparison with histopathological findings in human disease. Infection. 1990;18:332–341. doi: 10.1007/BF01646399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Radolf J D, Norgard M V, Brandt M E, Isaacs R D, Thompson P A, Beutler B. Lipoproteins of Borrelia burgdorferi and Treponema pallidum activate cachectin/tumor necrosis factor synthesis. J Immunol. 1991;147:1968–1974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schefler W C. Statistics for health professionals. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley Publication Company, Inc.; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schröder J M, Sticherling M, Henneicke H H, Preissiner W C, Christophers E. IL-1α or tumor necrosis factor-α stimulate release of three NAP-1/IL-8-related neutrophil chemotactic proteins in human dermal fibroblasts. J Immunol. 1990;144:2223–2232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schulze J, Breitner-Ruddock S, Von Briesen H, Brade V. High and low level cytokine induction in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by different Borrelia burgdorferi strains. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1996;185:31–37. doi: 10.1007/s004300050012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steere A C. Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:586–596. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198908313210906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steere A C, Duray P H, Butcher E C. Spirochetal antigens and lymphoid cell surface markers in Lyme synovitis: comparison with rheumatoid synovium and tonsillar lymphoid tissue. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:487–495. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stevens M G, Olsen S C. Comparative analysis of using MTT and XTT in colorimetric assay for quantitating bovine neutrophil bactericidal activity. J Immunol Methods. 1993;157:225–231. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(93)90091-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Straubinger R K, Chang Y-F, Jacobson R H, Appel M J G. Sera from OspA-vaccinated dogs, but not those from tick-infected dogs, inhibit in vitro growth of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2745–2751. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.10.2745-2751.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Straubinger R K, Straubinger A F, Härter L, Jacobson R H, Chang Y-F, Summers B A, Erb H N, Appel M J G. Borrelia burgdorferi migrates into joint capsules and causes an up-regulation of interleukin-8 in synovial membranes of dogs experimentally infected with ticks. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1273–1285. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1273-1285.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tai K-F, Ma Y, Weis J J. Normal human B lymphocytes and mononuclear cells respond to the mitogenic and cytokine-stimulatory activities of Borrelia burgdorferi and its lipoprotein OspA. Infect Immun. 1994;62:520–528. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.520-528.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tanaka T, Shibasaki F, Ishikawa M, Hirano N, Sakai R, Nishida J, Takenawa T, Hirai H. Molecular cloning of bovine actin-like protein actin 2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;187:1022–1028. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91299-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomsen M K. Is interleukin-1α a direct activator of neutrophil migration and phagocytosis in the dog? Agent Actions. 1990;29:35–36. doi: 10.1007/BF01964713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomsen M K, Thomsen H K. Effects of interleukin-1α on migration of canine neutrophils in vitro and in vivo. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1990;26:385–393. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(90)90121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van Dam A P, Kuiper H, Vos K, Widjojokusumo A, De Jongh B M, Spanjaard L, Ramselaar A C P, Kramer M D, Dankert J. Different genospecies of Borrelia burgdorferi are associated with distinct clinical manifestations of Lyme borreliosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:708–717. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.4.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Villinger F, Brar S S, Mayne A, Chikkala N, Ansari A A. Comparative sequence analysis of cytokine genes from human and nonhuman primates. J Immunol. 1995;155:3946–3954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamashita K, Fujinaga T, Hagio M, Miyamoto T, Izumisawa Y, Kotani T. Bioassay for interleukin-1, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-like activities in canine sera. J Vet Med Sci. 1994;56:103–107. doi: 10.1292/jvms.56.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yssel H, Nakamoto T, Schneider P, Freitas V, Collins C, Webb D, Mensi N, Soderberg C, Peltz G. Analysis of T lymphocytes cloned from the synovial fluid and blood of a patient with Lyme arthritis. Int Immunol. 1990;2:1081–1090. doi: 10.1093/intimm/2.11.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yuan, H. T., F. J. Kelly, and C. D. Bingle. 1996. Cloning and characterization of guinea pig TNF-α, IL-1β, and GM-CSF cDNA sequences. GenBank accession no. U46778.

- 55.Zucker K, Lu P, Fuller L, Asthana D, Esquenazi V, Miller J. Cloning and expression of the cDNA for canine TNF-alpha in E. coli. Lymphokine Cytokine Res. 1994;13:191–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]