Abstract

Background

Molecular abnormalities in the Wnt/β‐catenin pathway confer malignant phenotypes in lung cancer. Previously, we identified the association of leucine‐rich repeat‐containing G protein‐coupled receptor 6 (LGR6) with oncogenic Wnt signaling, and its downregulation upon β‐catenin knockdown in non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells carrying CTNNB1 mutations. The aim of this study was to explore the mechanisms underlying this association and the accompanying phenotypes.

Methods

LGR6 expression in lung cancer cell lines and surgical specimens was analyzed using quantitative RT‐PCR and immunohistochemistry. Cell growth was assessed using colony formation assay. Additionally, mRNA sequencing was performed to compare the expression profiles of cells subjected to different treatments.

Results

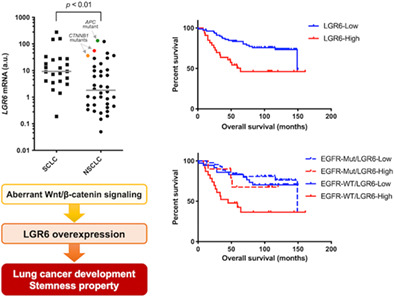

LGR6 was overexpressed in small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and NSCLC cell lines, including the CTNNB1‐mutated NSCLC cell lines HCC15 and A427. In both cell lines, LGR6 knockdown inhibited cell growth. LGR6 expression was upregulated in spheroids compared to adherent cultures of A427 cells, suggesting that LGR6 participates in the acquisition of cancer stem cell properties. Immunohistochemical analysis of lung cancer specimens revealed that the LGR6 protein was predominantly overexpressed in SCLCs, large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas, and lung adenocarcinomas, wherein LGR6 overexpression was associated with vascular invasion, the wild‐type EGFR genotype, and an unfavorable prognosis. Integrated mRNA sequencing analysis of HCC15 and A427 cells with or without LGR6 knockdown revealed LGR6‐related pathways and genes associated with cancer development and stemness properties.

Conclusions

Our findings highlight the oncogenic roles of LGR6 overexpression induced by aberrant Wnt/β‐catenin signaling in lung cancer.

Keywords: non‐small cell lung cancer, oncogene, small cell lung cancer, Wnt pathway, β‐catenin

LGR6 overexpression was observed in lung cancers, including CTNNB1‐mutated cell lines, and was associated with vascular invasion, a wild‐type EGFR genotype, and an unfavorable prognosis in lung adenocarcinomas. mRNA sequencing analysis of CTNNB1‐mutated cells with or without LGR6 knockdown revealed LGR6‐related pathways and genes associated with cancer development and stemness properties. These results highlight the oncogenic roles of LGR6 overexpression induced by aberrant Wnt/β‐catenin signaling in lung cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer‐associated mortality worldwide. 1 Non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) constitutes around 85% of all lung cancers, and its major subtypes are lung adenocarcinoma (most common) and squamous cell lung carcinoma. Patients with NSCLC are usually diagnosed with metastatic diseases, and the survival rate of stage IV patients with NSCLC is extremely low. 2 Molecular targeted therapies have prolonged the survival of patients with NSCLC 3 ; however, the majority of patients become refractory to treatment through various mechanisms, including epithelial to mesenchymal transitions (EMT). 4 Recent progress in immuno‐oncology has led to the exploitation of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) against lung cancer, 5 whereas the prognosis of patients with advanced lung cancer remains unsatisfactory. Hence, the development of new treatment strategies and biomarkers for lung cancer are urgently required.

The Wnt/β‐catenin pathway plays a pivotal role in regulating embryogenesis and multiple cellular functions. 6 In this pathway, β‐catenin is engaged by a complex comprising glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK‐3β), adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), and Axin. β‐catenin phosphorylation by GSK‐3β at Ser/Thr residues, encoded by its exon 3, results in the proteasomal degradation of β‐catenin. 6 The constitutive activation of Wnt/β‐catenin signaling caused by the altered components of its pathway affects tumor growth, angiogenesis, cancer cell stemness, EMT, immunomodulation of the tumor microenvironment, and therapeutic resistance, mainly through the T cell factor (TCF)‐mediated transcriptional activation of Wnt target genes. 7 Mutations in exon 3 of the CTNNB1 gene (encoding β‐catenin) at Ser33, Ser37, Thr41, and Ser45 stabilize β‐catenin and lead to TCF‐induced transcriptional activation, thus driving tumorigenesis and metastasis in various human cancers. 8 Alterations in the Wnt pathway subvert tumor immunosurveillance and promote tumor immune evasion, conferring resistance against ICIs. 9 In NSCLC, CTNNB1 exon 3 mutations are associated with an unfavorable prognosis. 10 , 11 Additionally, these mutations have been found in patients with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)‐mutated NSCLC refractory to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. 4 , 12 Although the frequency of CTNNB1 mutations in exon 3 accounts for 2% of all NSCLCs, 13 Wnt pathway abnormalities have been found in approximately half of all NSCLCs. 14 Therefore, the oncogenic significance of the Wnt/β‐catenin signaling pathway is worth investigating to advance treatment strategies and biomarkers to predict therapeutic efficiency and prognosis in NSCLC.

Previously, we found CTNNB1 exon 3 mutations in a subset of NSCLC tumor specimens and that NSCLC cell lines exhibit constitutive activation of the Wnt/β‐catenin signaling. 15 , 16 To explore the key genes that control NSCLC accompanied by an aberrant Wnt/β‐catenin signaling, we previously performed microarray analysis comparing the gene expression profiles of CTNNB1‐silenced HCC15 NSCLC cells carrying a CTNNB1 exon 3 mutation with CTNNB1‐retained HCC15 cells (Gene Expression Omnibus [GEO] under the accession number GSE183178). We identified the leucine‐rich repeat‐containing G protein‐coupled receptor 6 (LGR6) gene, whose expression was significantly downregulated (−2.78‐fold‐change) by β‐catenin knockdown (Table S1). 17 LGR6 is a member of the leucine‐rich repeat‐containing subgroup of the G protein‐coupled seven‐transmembrane protein superfamily, which also includes LGR5, 18 and is a receptor for R‐spondin proteins that function as adult stem cell growth factors by potentiating Wnt signaling. 19 Previous studies have suggested that LGR6 is involved in the development of various human cancers. Elevated LGR6 expression is correlated with poor prognosis of esophageal cancer, 20 , 21 breast cancer, 22 cervical cancer, 23 and ovarian cancer. 24 It also confers malignant phenotypes by promoting tumor proliferation and invasion in gastric cancer, 25 , 26 breast cancer, 22 and glioblastoma. 27 Furthermore, a recent study demonstrated that LGR6 is transcriptionally upregulated by overexpressed β‐catenin in cervical cancer. 23 However, the involvement of LGR6 in the Wnt/β‐catenin pathway and the associated malignant phenotypes of lung cancer remain largely unknown. Therefore, we conducted the current study to elucidate the oncogenic roles of LGR6 in lung cancer. Herein, we found overexpression of LGR6 in small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and NSCLC cell lines and tumor specimens. Elevated LGR6 expression was associated with vascular invasion, the wild‐type EGFR genotype, and unfavorable prognosis of lung adenocarcinomas. Additionally, mRNA sequencing analysis of CTNNB1‐mutated NSCLC cells with or without LGR6 knockdown uncovered LGR6‐related pathways and genes associated with cancer development and stemness properties. Overall, our findings clarify the therapeutic and prognostic significance of LGR6 overexpression induced by aberrant Wnt signaling in lung cancer.

METHODS

Cell lines

The lung cancer cell lines and human bronchial epithelial cell line used in the current study are shown in Table S2. The NCI‐H1373, NCI‐H2030, SW1573, and A427 cell lines were purchased from ATCC, and the other cell lines were provided by the Hamon Center of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas. The HCC15 NSCLC cell line harbors a homozygous CTNNB1 S45F mutation, 16 and the A427 NSCLC cell line harbors a homozygous CTNNB1 T41A mutation. 15 Detailed information on these cell lines is available in previous studies, 28 in the COSMIC database from the Sanger Institute (http://www.sanger.ac.uk), and on the DepMap portal (https://depmap.org). RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma‐Aldrich) containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) was used for culturing cancer cell lines. The HBEC3 cell line was maintained in keratinocyte‐SFM medium (Invitrogen) containing bovine pituitary extract (50 μg/mL) and epidermal growth factor (EGF; 5 ng/mL). We confirmed all cell lines to be mycoplasma‐free using the e‐Myco kit (Boca Scientific). We also confirmed that all cell lines had the same DNA fingerprint as that in the libraries hosted by Minna laboratories or ATCC using the PowerPlex 1.2 kit (Promega).

Reverse transcription‐quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT‐qPCR) analysis

RT‐qPCR analysis was performed to determine the expression levels of LGR6, CTNNB1, and GAPDH using the commercially available sets of TaqMan probes and primers (assay ID for LGR6: Hs00663887_m1; assay ID for CTNNB1: Hs00355049_m1; and assay ID for GAPDH: Hs99999905_m1) purchased from Applied Biosystems and a LightCycler 480 system (Roche Diagnostics) as described previously. 29 Briefly, following total RNA extraction using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen), 2 μg of total RNA was used to synthesize cDNA using the SuperScript VILO Master Mix (Invitrogen) under the following reaction conditions: 25°C for 10 min, 42°C for 60 min, and 85°C for 5 min. PCR amplification was then conducted using 20 μL of reaction mixture containing 2 μL cDNA, 1 μL of the TaqMan probe and primer mixture for each target gene, 10 μL of the LightCycler 480 Probe Master (Roche Diagnostics), and 7 μL water with the PCR conditions as follows: 95°C for 5 min for initial denaturation, followed by 50 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C. Gene expression data were normalized to the reference gene GAPDH. The gene expression levels were determined using the 2−ΔΔCq method. 30

Target gene silencing by siRNA

All siRNA nucleotides were purchased from Dharmacon. An siRNA targeting the CTNNB1 gene (CTNNB1‐1) was designed as described previously. 31 siRNAs against LGR6 (siLGR6‐1; #D‐005648‐03 and siLGR6‐2; #D‐005648‐18) and CTNNB1 (siCTNNB1‐2; #D‐003482‐02) were obtained from the siGENOME library (Dharmacon). An siRNA targeting Tax was used as a nontargeting control. 31 Cells were transfected with siRNAs (10 nM) using the Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's protocol and were collected to verify target gene silencing at 48 h post‐transfection.

Colony formation assay

This assay was executed as described previously. 29 Briefly, cells were transfected with siRNAs and collected after 24 h. The cells were seeded in a six‐well multi‐dish (1000 cells/well for HCC15; 2000 cells/well for A427). Two weeks after the initial treatment, the colonies were stained with methylene blue and counted.

TCGA database analysis

LGR6 mRNA expression data in lung adenocarcinoma samples were obtained from the TCGA database (http://cancergenome.nih.gov/) as previously described. 32 The cutoff value of the LGR6 mRNA level was 222.8 based on the mean + 2 standard deviations of its expression in normal tissue and dichotomized into “high” and “low”.

Immunohistochemical analysis and EGFR mutational testing of tumor specimens

Immunohistochemical staining was conducted to evaluate LGR6 and Ki‐67 expression in surgical specimens from 244 consecutive patients diagnosed with lung cancer who received surgery between July 2002 and December 2012 at Gunma University Hospital, Gunma, Japan. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Gunma University Hospital, and informed consent was obtained from each patient. The tumor samples comprised 112 lung adenocarcinomas, 98 squamous cell lung carcinomas, 19 SCLCs, and 15 large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas (LCNECs). Vascular invasion was defined as positive microscopic or macroscopic vascular invasion in the tumors. Sections stained by Elastica van Gieson were examined for the presence of vascular invasion; this was determined by identifying conspicuous clusters of intravascular cancer surrounded by an elastic layer. The surgical specimens were promptly frozen after sampling and stored at −80°C until genomic DNA extraction. EGFR mutation testing was achieved using the SmartAmp2 kit (DNAFORM) as previously described, 33 and mutations were confirmed by direct sequencing using the ABI PRISM 3100 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). LGR6 and Ki‐67 protein expression was evaluated by immunohistochemistry as described previously 33 using rabbit monoclonal anti‐human LGR6 antibodies (#ab126747; 1:50 dilution; Abcam, Tokyo, Japan) and mouse monoclonal anti‐human Ki‐67 antibodies (#M7240; 1:40 dilution; Dako, Agilent Technologies), respectively. Tumor cells with nuclear or cytoplasmic staining were defined as positive. Definitions of the LGR6 staining scores were as follows: 1, <10%; 2, 10%–25%; 3, 26%–50%; and 4, >50% of the stained cells. Tumors with a score ≥3 were considered to have high expression levels. The Ki‐67 labeling index was calculated as the percentage of stained cells in each sample. 34

Transcriptome analyses

mRNA sequencing comparing the expression profiles of LGR6‐silenced and LGR6‐retained CTNNB1‐mutated NSCLC cell lines (HCC15 and A427), or comparing those of sphere‐forming and adherent A427 cells were performed as described previously. 35 Purified RNA quality was evaluated by the RNA integrity number (RIN) using the Agilent RNA6000 Pico kit and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). High‐quality RNA samples (RIN >8.0) were used for RNA‐seq analysis. Sequence libraries were prepared using 1 μg of total RNA with a KAPA mRNA HyperPrep Kit (Kapa Biosystems Inc.), following the manufacturer's instructions. The generated libraries and 1% PhiX spike‐in were then subjected to paired‐end sequencing of 38‐bp reads using a NextSeq500 System (Illumina Inc.) with a NextSeq500 high output version 2.5 kit (Illumina). The reads were aligned to the UCSC human reference genome 19 (hg19) for calculation of expression values (read counting and transcripts per million [TPM] normalized value) using the STAR (version 2.5.3a)‐RSEM (version 1.3.3) pipeline with the following options: ‐paired‐end, ‐star, ‐strandedness reverse, and ‐estimate‐rspd. The number of input reads was more than 33.3 million. Using the TCC (version 1.30.0) and edgeR (version 3.32.1) packages, the TCC‐iDEGES‐edgeR pipeline in R (https://www.R-project.org/, version 4.0.3) detected differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the two conditions. 36 Pathway analysis was conducted using ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA version 68752261, Qiagen). Genes with a p‐value <0.05 were considered significant DEGs. Sequence data are available through GEO under the accession number GSE218163 for LGR6 knockdown in HCC15 and A427 cells and GSE218164 for floating versus adherent A427 cell components.

Statistical analysis

Two independent groups were compared by the Mann–Whitney U test, whereas two paired groups were compared with a paired t‐test. Three or more independent groups were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn's multiple comparisons, or one‐way analysis of variance with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons. Two nominal variables were compared using Fisher's exact test, whereas three or more nominal variables were compared using a Chi‐square test for the trend. Survival curves were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method. Differences in the survival rate between the two groups were analyzed using the log‐rank test, and those between three or more groups were analyzed using the log‐rank test for the trend. The above statistical analyses were conducted using Prism 9 for Mac OS (GraphPad Software) and multivariate analyses were carried out using SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM) with a stepwise Cox proportional hazards model to identify independent prognostic factors. p‐values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

LGR6 overexpression confers tumor growth and cancer stem cell (CSC) properties

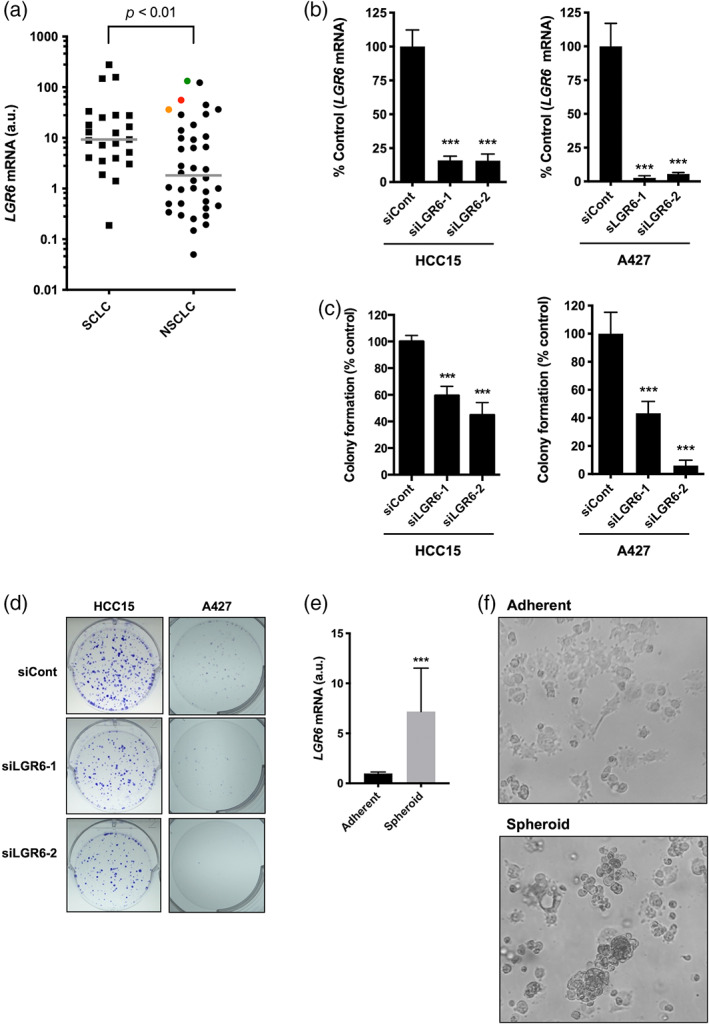

We first evaluated LGR6 mRNA expression in a panel of lung cancer cell lines, consisting of 23 SCLCs and 40 NSCLCs. When overexpression was defined as ≥10‐fold gene expression compared to the LGR6 level in the HBEC3 noncancerous bronchial epithelial cell line, LGR6 was overexpressed in 47.8% of SCLCs and 27.5% of NSCLCs, including the CTNNB1‐mutated HCC15 and A427 cell lines and the HCC2935 cell line harboring a homozygous APC Q1367* mutation (Figure 1a). siRNA‐mediated β‐catenin knockdown decreased LGR6 expression in A427 and HCC15 cells (Figure S1). In both HCC15 and A427 cells, siRNA‐mediated LGR6 knockdown resulted in in vitro growth inhibition (Figure 1b–d), suggesting that LGR6 overexpression promotes tumor growth of CTNNB1‐mutated NSCLC cells.

FIGURE 1.

LGR6 overexpression confers the in vitro tumor growth and spheroid formation abilities in lung cancer cell lines. (a) LGR6 mRNA expression in 23 SCLC and 40 NSCLC cell lines, including the CTNNB1‐mutated cell lines HCC15 (red dot) and A427 (orange dot), and the APC‐mutated cell line HCC2935 (green dot). LGR6 expression levels were significantly higher in SCLCs than in NSCLCs. Data are presented relative to the LGR6 expression level in the noncancerous human bronchial epithelial cell line HBEC3, which was set to 1. (b) Treatment with LGR6‐targeting siRNAs reduced LGR6 expression in HCC15 and A427 cells. (c) siRNA‐mediated LGR6 knockdown inhibited colony formation in HCC15 and A427 cells. (d) Representative images of stained colonies are shown. (e) Elevated LGR6 expression in sphere‐forming A427 cells compared to that in adherent A427 cells. (f) Representative images of adherent and spheroid cell cultures are shown. ***p < 0.001. Columns: mean ± standard deviation. LGR6, leucine‐rich repeat‐containing G protein‐coupled receptor 6; NSCLC, non‐small cell lung cancer; SCLC, small cell lung cancer.

Expression analysis showed that LGR6 levels were significantly higher in SCLC cell lines than in NSCLC cell lines (Figure 1a). Morphologically, lung cancer cell lines are classified into sphere‐forming and adherent cells, with most SCLC cell lines cultivating as spheroid cultures. 31 SCLC tumors can be enriched in cancer stem cells, 37 and spheroid formation in cell culture is a CSC‐related characteristic of tumors in vitro. 38 Notably, LGR6 was found to be a skin and lung stem cell marker. 39 , 40 Accordingly, we hypothesized that the LGR6 expression level might be higher in sphere‐forming A427 cells than in adherent A427 cells, which grow as both spheroid and adherent cultures. Indeed, we found that LGR6 expression levels were significantly higher in spheroid cultures than in adherent cultures (Figure 1e,f). Furthermore, mRNA sequencing analysis disclosed DEGs between sphere‐forming and adherent A427 cells, including several stem cell‐associated genes such as MMP1 (m‐value: 10.684), CPA4 (m‐value: 10.297), and SRPX2 (m‐value: 4.567), all of which were upregulated in sphere‐forming A427 cells (Table S3). Ingenuity pathway analysis showed that “HIF1α signaling” (z‐score: 2.840), “Ephrin receptor signaling” (z‐score: 2.828), and “IL‐17 signaling” (z‐score: 2.828) were the three most significantly upregulated pathways in spheroid cultures (Table S4), all of which are involved in the regulation of cancer stem cell properties. 41 , 42 , 43

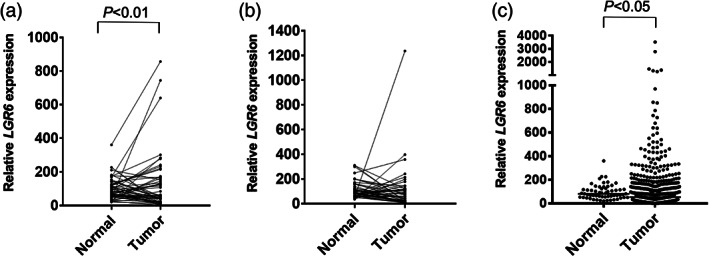

Elevated LGR6 expression involved in aggressive phenotypes in patients with NSCLC

LGR6 expression levels were evaluated in NSCLC tumors using the TCGA dataset. Upon comparing matched NSCLC tumors and normal tissues, LGR6 expression was found to be significantly higher in lung adenocarcinoma tumors than in paired normal tissues (Figure 2a), whereas there was no significant difference in LGR6 expression levels between squamous cell lung carcinoma tumors and paired normal tissues (Figure 2b). Consistently, LGR6 had higher expression levels in lung adenocarcinoma tumors than in independent normal lung tissues (Figure 2c).

FIGURE 2.

LGR6 expression analysis in NSCLC tumors using the TCGA dataset. LGR6 expression in (a) 57 paired lung adenocarcinoma tumors versus that in adjacent normal tissues and (b) in 50 paired lung squamous cell carcinoma tumors versus that in adjacent normal tissues. (c) LGR6 expression in lung adenocarcinoma tumors (N = 512) versus that in normal lung tissues (N = 58). LGR6, leucine‐rich repeat‐containing G protein‐coupled receptor 6; NSCLC, non‐small cell lung cancer.

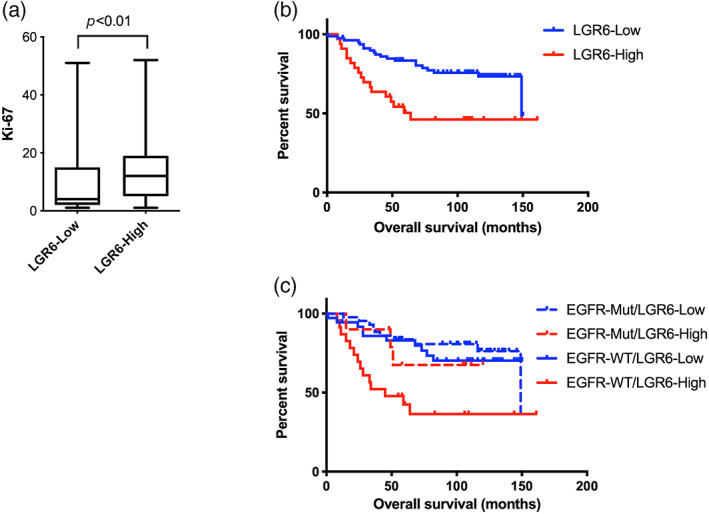

Next, immunohistochemical analysis was performed to evaluate LGR6 protein expression in surgical specimens from 244 patients with lung cancer, comprising 112 lung adenocarcinomas, 98 squamous cell lung carcinomas, 19 SCLCs, and 15 LCNECs (Figure S2). Significant differences were found in the proportion of LGR6‐overexpressing samples among the histological subtypes; LGR6 expression was elevated in 30% of lung adenocarcinomas, 53% of SCLCs, and 73% of LCNECs, whereas only 5% of lung squamous cell carcinomas exhibited increased levels of LGR6 expression (Table 1). In the lung adenocarcinoma subgroup, LGR6 overexpression was significantly associated with vascular invasion and the wild‐type EGFR genotype, and tended to be associated with male sex, smoking, and lymphatic permeation (Table 2). Additionally, LGR6 expression positively correlated with the Ki‐67 labeling index in lung adenocarcinomas (Figure 3a). Meanwhile, there was no relationship between LGR6 expression and any of the clinicopathological parameters in pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors (Table S5).

TABLE 1.

LGR6 expression and clinicopathological parameters in patients with lung cancer.

| LGR6 expression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Category | No. | High | Low | p‐value |

| Sex | Male | 153 | 35 | 118 | 0.540 |

| Female | 91 | 24 | 67 | ||

| Age | <70 | 106 | 24 | 82 | 0.654 |

| ≥70 | 138 | 35 | 103 | ||

| Smoking status | Smoker | 172 | 42 | 130 | 0.745 |

| Nonsmoker | 72 | 16 | 56 | ||

| Histology | Adenocarcinoma | 112 | 33 | 79 | 0.012 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 98 | 5 | 93 | ||

| Small cell carcinoma | 19 | 10 | 9 | ||

| Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma | 15 | 11 | 4 | ||

| Stage | I | 182 | 41 | 141 | 0.509 |

| II | 35 | 8 | 27 | ||

| III | 20 | 6 | 14 | ||

| IV | 7 | 2 | 5 | ||

Abbreviation: LGR6, leucine‐rich repeat‐containing G protein‐coupled receptor 6.

TABLE 2.

LGR6 expression and clinicopathological factors in patients with lung adenocarcinomas.

| LGR6 expression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | No. | High | Low | p value | |

| Sex | Male | 37 | 15 | 22 | 0.082 |

| Female | 75 | 18 | 57 | ||

| Age | <70 years | 55 | 14 | 41 | 0.411 |

| ≥70 years | 57 | 19 | 38 | ||

| Smoking status | Smoker | 43 | 17 | 26 | 0.088 |

| Nonsmoker | 69 | 16 | 53 | ||

| Stage | I | 91 | 25 | 66 | 0.391 |

| II | 8 | 3 | 5 | ||

| III | 10 | 4 | 6 | ||

| IV | 3 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Lymphatic permeation | + | 42 | 17 | 25 | 0.056 |

| − | 70 | 16 | 54 | ||

| Vascular invasion | + | 32 | 15 | 18 | 0.023 |

| − | 80 | 18 | 61 | ||

| Pleural involvement | + | 61 | 15 | 46 | 0.298 |

| − | 51 | 18 | 33 | ||

| EGFR mutation status | EGFR mutation | 53 | 10 | 43 | 0.023 |

| Wild‐type EGFR | 59 | 23 | 36 | ||

Abbreviation: LGR6, leucine‐rich repeat‐containing G protein‐coupled receptor 6.

FIGURE 3.

Elevated LGR6 expression is associated with unfavorable prognosis in patients with lung adenocarcinoma, especially in those with wild‐type EGFR. (a) The Ki‐67 labeling index was higher in lung adenocarcinomas with low LGR6 expression (N = 72) compared to that in those with high LGR6 expression (N = 29). (b) Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for comparisons between patients with lung adenocarcinoma showing high (LGR6‐High, N = 33) or low (LGR6‐Low, N = 79) LGR6 protein expression (p < 0.01). (c) Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for comparisons among the four groups: EGFR‐Mut/LGR6‐Low (N = 43), EGFR‐Mut/LGR6‐High (N = 10), EGFR‐Wt/LGR6‐Low (N = 36), EGFR‐WT/LGR6‐High (N = 23). Significant differences in overall survival between the EGFR‐Mut/LGR6‐Low and EGFR‐WT/LGR6‐High groups (p < 0.001) and between the EGFR‐WT/LGR6‐Low versus EGFR‐WT/LGR6‐High groups (p < 0.01). EGFR‐WT, EGFR wild‐type; EGFR‐Mut, EGFR mutant; LGR6‐Low, staining score <3; LGR6‐High, staining score ≥3; LGR6, leucine‐rich repeat‐containing G protein‐coupled receptor 6.

We also assessed the prognostic significance of LGR6 overexpression in lung adenocarcinoma. Patients with lung adenocarcinoma showing high LGR6 expression had significantly shorter overall survival times than those with low LGR6 expression (Figure 3b). When patients with lung adenocarcinoma were classified into subgroups according to LGR6 expression levels and EGFR mutation status, patients with tumors carrying wild‐type EGFR and high LGR6 expression showed the shortest overall survival (Figure 3c). Multivariate analysis showed that LGR6 overexpression was an independent prognostic factor in lung adenocarcinoma patients (Table 3). These results demonstrated that LGR6 overexpression confers aggressive phenotypes and unfavorable prognosis in patients with lung adenocarcinoma, especially in those with wild‐type EGFR.

TABLE 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of overall survival in patients with lung adenocarcinoma.

| Prognostic marker | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | |||

| Age (in years) | 1.022 | 0.985–1.059 | 0.243 |

| Sex (male vs. female) | 1.955 | 1.012–3.778 | 0.046 |

| Smoking status (smoker vs. nonsmoker) | 1.907 | 0.999–3.641 | 0.050 |

| Stage | 1.412 | 1.197–1.667 | <0.001 |

| LGR6 expression (high vs. low) | 2.719 | 1.415–5.224 | 0.003 |

| Multivariate analysis | |||

| Stage | 1.454 | 1.222–1.730 | <0.001 |

| LGR6 expression (high vs. low) | 2.570 | 1.320–5.003 | 0.005 |

Note: Age was analyzed as a continuous variable and stage was categorized as the variables categorized by IA, IB, IIA, IIB, IIIA, IIIB, and IV.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; LGR6, leucine‐rich repeat‐containing G protein‐coupled receptor 6.

Identification of genes and pathways conferring LGR6‐induced malignant phenotypes

To explore the molecular mechanisms underlying LGR6‐induced malignant phenotypes, mRNA sequencing analysis was performed to compare the expression profiles of siRNA‐mediated LGR6‐silenced cells with those of control siRNA‐treated cells using the CTNNB1‐mutated NSCLC cell lines HCC15 and A427. A total of 309 DEGs were identified in HCC15 cells, and the 10 most significant DEGs (the genes ranked by p‐values) were RPL36A‐HNRNPH2, ANKRD20A1, UHMK1, CKAP4, ELL2, CPEB3, ZNF213, SMIM13, DDAH1, and SUZ12 (Table S6). In A427 cells, 637 DEGs were identified, with the 10 most significant DEGs being DYX1C1‐CCPG1, GATSL1, LOC730091, CKAP4, DDAH1, TGIF2‐C20orf24, GPR89C, SEPP1, CPEB3, and ELL2 (Table S7). Integrated analysis of mRNA sequencing in HCC15 and A427 cells identified 18 DEGs, including 11 downregulated and seven upregulated genes (Table 4). Pathway analysis was also conducted based on the mRNA sequencing data for both HCC15 and A427 cell lines (Tables S8 and S9), and “G‐protein coupled receptor signaling” (z‐score: −2.840 in HCC15; z‐score: −2.502 in A427), “Cardiac hypertrophy signaling (enhanced)” (z‐score: −2.111 in HCC15; z‐score: −2.065 in A427), and “Pulmonary fibrosis idiopathic signaling pathway” (z‐score: −2.309 in HCC15; z‐score: −2.065 in A427) were the commonly regulated pathways (Table 5) which are potentially associated with the progression of lung cancer exhibiting LGR6 overexpression through the Wnt/β‐catenin pathway activation.

TABLE 4.

Genes commonly regulated by siRNA‐mediated LGR6 knockdown in CTNNB1‐mutated NSCLC cells.

| A427 | HCC15 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | m‐value: log2 | p‐value | Rank | siControl | siLGR6‐1 | siLGR6‐2 | siControl | siLGR6‐1 | siLGR6‐2 |

| CKAP4 | 2.318 | 0.002 | 1 | 828.7 | 3503.2 | 2998.0 | 903.9 | 5900.2 | 4876.8 |

| SMIM13 | −2.121 | 0.003 | 2 | 2296.0 | 413.3 | 1306.0 | 5225.0 | 419.9 | 1317.5 |

| ELL2 | −1.917 | 0.007 | 3 | 1321.8 | 381.6 | 491.2 | 1809.9 | 427.6 | 357.5 |

| HIPK3 | −1.505 | 0.010 | 4 | 4300.9 | 1628.8 | 1730.0 | 4833.7 | 1530.4 | 1547.2 |

| FKBP4 | 1.787 | 0.010 | 5 | 5403.0 | 18345.7 | 14961.9 | 3553.3 | 12591.1 | 15932.9 |

| CORO7‐PAM16 | 10.426 | 0.010 | 6 | 0.0 | 17.9 | 13.8 | 0.0 | 10.6 | 8.7 |

| DDAH1 | −1.785 | 0.012 | 7 | 3343.4 | 1021.1 | 1077.0 | 10743.2 | 3424.9 | 2654.2 |

| UHMK1 | −1.636 | 0.013 | 8 | 16303.5 | 9348.3 | 3866.5 | 13403.2 | 3469.2 | 2435.2 |

| CPEB3 | −2.227 | 0.018 | 9 | 501.5 | 159.6 | 111.1 | 744.6 | 153.1 | 108.4 |

| SNX30 | 2.083 | 0.021 | 10 | 230.8 | 810.3 | 720.3 | 372.3 | 2222.9 | 1356.1 |

| ANKRD20A2 | 4.492 | 0.022 | 11 | 3.5 | 58.4 | 31.6 | 0.0 | 49.6 | 17.7 |

| OSTM1 | −1.594 | 0.023 | 12 | 1963.2 | 426.6 | 784.6 | 2096.8 | 387.2 | 1092.0 |

| RHEB | 1.629 | 0.024 | 13 | 1006.6 | 2830.0 | 2594.5 | 1467.1 | 4861.9 | 5013.2 |

| LINC00202‐1 | −9.444 | 0.026 | 14 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| GNB4 | −1.446 | 0.032 | 15 | 6557.0 | 2621.3 | 2617.9 | 3538.5 | 1461.1 | 710.8 |

| KATNAL1 | −1.362 | 0.038 | 16 | 1463.6 | 755.1 | 696.9 | 2755.9 | 1046.0 | 786.0 |

| FBXW5 | 1.483 | 0.039 | 17 | 770.3 | 1739.3 | 1831.4 | 856.4 | 2596.6 | 2927.0 |

| C1orf151‐NBL1 | −2.721 | 0.047 | 18 | 40.8 | 6.1 | 5.4 | 49.8 | 15.9 | 0.0 |

Abbreviations: LGR6, leucine‐rich repeat‐containing G protein‐coupled receptor 6; NSCLC, non‐small cell lung cancer.

TABLE 5.

Common canonical pathways affected by LGR6 knockdown in CTNNB1‐mutated NSCLC cells.

| A427 | HCC15 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canonical pathway | Z‐score | −log (p‐value) | Ratio | Z‐score | −log (p‐value) | Ratio |

| G‐protein coupled receptor signaling | −2.502 | 1.970 | 0.039 | −2.840 | 1.690 | 0.021 |

| Pulmonary fibrosis idiopathic signaling pathway | −2.065 | 3.460 | 0.058 | −2.309 | 3.260 | 0.037 |

| Cardiac hypertrophy signaling (enhanced) | −2.065 | 2.530 | 0.044 | −2.111 | 2.260 | 0.026 |

| Role of NFAT in cardiac hypertrophy | −1.667 | 3.020 | 0.063 | −1.342 | 2.290 | 0.036 |

| PPARα/RXRα activation | −1.414 | 1.350 | 0.046 | 0.447 | 1.540 | 0.031 |

| Wound healing signaling pathway | −1.155 | 1.730 | 0.048 | −2.121 | 1.970 | 0.032 |

| Regulation of the epithelial mesenchymal transition by growth factors pathway | −1.000 | 2.180 | 0.057 | −1.134 | 3.300 | 0.047 |

| Glioma signaling | −1.000 | 2.010 | 0.065 | N/A | 2.440 | 0.048 |

| Epithelial adherens junction signaling | −0.832 | 3.980 | 0.083 | 0.447 | 1.400 | 0.032 |

| PTEN signaling | −0.816 | 1.560 | 0.053 | 1.000 | 1.480 | 0.033 |

| STAT3 pathway | −0.378 | 1.800 | 0.059 | −1.000 | 1.650 | 0.037 |

| Ferroptosis signaling pathway | −0.333 | 2.350 | 0.068 | −2.449 | 2.310 | 0.046 |

| RAC signaling | 0.000 | 1.750 | 0.058 | −2.000 | 1.610 | 0.036 |

| TGF‐β signaling | 0.378 | 2.090 | 0.073 | N/A | 1.560 | 0.042 |

Abbreviations: LGR6, leucine‐rich repeat‐containing G protein‐coupled receptor 6; N/A, not available; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T cells; NSCLC, non‐small cell lung cancer.

DISCUSSION

LGR5 is a well‐known Wnt target gene and is involved in the progression of several human cancers 44 , 45 , 46 ; however, the oncogenic role of LGR6 and its relationship with the Wnt/β‐catenin pathway in lung cancer remains unclear. We found that β‐catenin knockdown downregulated LGR6 expression in NSCLC cells carrying CTNNB1 exon 3 mutations, suggesting that LGR6 is a Wnt target gene. Our results align with a previous report showing that β‐catenin is an upstream regulator of LGR6 in cervical cancer. 23 Both LGR5 and LGR6 are receptors for R‐spondins that control cell stemness in several organs by enhancing Wnt signaling. 47 , 48 LGR6 is also a marker of bronchioalveolar stem cells. 40 , 49 Moreover, LGR6 contributes to CSC properties in ovarian, breast, and cervical cancers. 22 , 23 , 24 In our study, when comparing LGR6 expression between spheroid and adherent components of A427 cells harboring a CTNNB1 exon 3 mutation, LGR6 was predominantly expressed in the component of spheroids, which is a CSC‐related characteristic, 38 accompanied by upregulation of several stem cell‐associated pathways and genes, including MMP1, 50 CPA4, 51 and SRPX2. 52 These findings support the idea that Wnt/β‐catenin pathway activation, mediated by CTNNB1 exon 3 mutations, induces LGR6 overexpression, which in turn confers cancer stemness properties via Wnt pathway activation.

Previous studies have demonstrated the relevance of elevated LGR5 expression in the advancement in stage and unfavorable prognosis in lung adenocarcinomas. 53 , 54 However, the clinicopathological and prognostic roles of LGR6 expression in lung cancer are unclear. Guinot et al. analyzed 53 lung cancers for LGR6 expression and found that elevated LGR6 expression was preferentially observed in lung adenocarcinomas at advanced stages, in which the number of Ki‐67‐positive cells was increased. 55 Consistent with their observation, we found that LGR6 expression was elevated in lung adenocarcinomas and associated with an increased Ki‐67 labeling index. In addition, we found that LGR6 overexpression was associated with vascular invasion and the wild‐type EGFR genotype in lung adenocarcinomas, and that LGR6 overexpression was a poor prognostic factor in patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Similarly, recent studies have reported a correlation between high LGR6 expression and an unfavorable prognosis in breast, colon, ovarian, and esophageal cancers. 20 , 21 , 22 , 24 , 56 Considering our results along with these findings, it is possible that LGR6 overexpression confers malignant phenotypes by enhancing tumor progression and metastasis, resulting in unfavorable outcomes in patients with lung adenocarcinomas. It is also possible that LGR6 expression is a prognostic marker for lung adenocarcinomas without EGFR mutations.

mRNA sequencing analyses that compared expression profiles between LGR6‐silenced and LGR6‐retained NSCLC cell lines that harbor CTNNB1 exon 3 mutations revealed several LGR6‐related genes that are involved in tumorigenesis. For instance, among the common DEGs putatively upregulated by LGR6, ELL2, DDAH1, UHMK1, and guanine nucleotide binding protein subunit‐4 (GNB4) have been indicated as oncogenes in previous studies. Elongation factor for RNA polymerase II 2 (ELL2) appears to be an oncogenic protein required for survival and proliferation in androgen receptor‐negative neuroendocrine prostate cancers, 57 whereas its oncogenic role in lung cancer is largely unknown. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase‐1, encoded by DDAH1, is overexpressed in various human cancers and is involved in tumor angiogenesis. 58 UHMK1, which encodes the protein U2 auxiliary factor homology motif kinase 1, 59 is overexpressed in lung adenocarcinomas and functions as an oncogene via activation of the PI3K/AKT mTOR pathway. 60 GNB4 is highly expressed in urothelial carcinoma, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, gastric cancer, and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, and is a stemness‐related gene. 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 In terms of common DEGs putatively downregulated by LGR6, CKAP4 encodes a Dickkopf (DKK1)‐binding protein in the plasma membrane and participates in the regulation of Wnt/β‐catenin signaling. 65 CKAP4 appears to play both tumor suppressor and oncogenic roles depending on the tumor types. 65 , 66 , 67 SNX30 encodes sorted nexin‐30 protein, a member of the sorted nexin, and is a hypoxia and ferroptosis‐related gene, which were downregulated in lung adenocarcinomas. 68 Further studies on these genes would help to elucidate the regulatory mechanisms of LGR6 that promote malignant behavior in lung cancer.

The limitations of the present study are that only two NSCLC cell lines (HCC15 and A427) harboring CTNNB1 exon 3 mutations were examined, and no gain‐of‐function experiments using bronchial epithelial cells were performed. Moreover, the low number of SCLC tumor specimens analyzed prevented us from reaching a more substantial conclusion. Lastly, the mRNA sequencing data obtained from the siRNA experiments are preliminary; thus, further analysis with gain‐of‐function experiments using LGR6 low‐expressing or undetectable cell lines are required to verify the relationship between LGR6 and the DEGs identified in this study. Nevertheless, the current findings provide important information for future research on the preclinical and clinical implications of LGR6 in lung cancer.

In summary, the current study highlights the oncogenic significance of LGR6 overexpression induced by Wnt/β‐catenin pathway activation in lung cancer, especially in lung adenocarcinoma with wild‐type EGFR. Given that the Wnt/β‐catenin pathway plays multiple roles in malignant phenotypes, including immunomodulation of the tumor microenvironment and cancer stemness related to therapeutic resistance, 7 , 14 further studies on the therapeutic and prognostic value of LGR6 may help to improve the survival of patients with lung cancer.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors had full access to the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Conceptualization, Noriaki Sunaga; Investigation, Noriaki Sunaga, Kyoichi Kaira, Ichidai Tanaka, Yosuke Miura, Seshiru Nakazawa, Yoichi Ohtaki, Reika Kawabata‐Iwakawa and Luc Girard; Validation, Noriaki Sunaga, Kyoichi Kaira, Kimihiro Shimizu and Mitsuo Sato; Formal analysis, Noriaki Sunaga, Ichidai Tanaka, Reika Kawabata‐Iwakawa and Luc Girard; Writing—Original draft, Noriaki Sunaga; Writing—Review & Editing, Noriaki Sunaga, Kyoichi Kaira, Kimihiro Shimizu, Ichidai Tanaka, Yosuke Miura, Seshiru Nakazawa, Yoichi Ohtaki, Reika Kawabata‐Iwakawa, Mitsuo Sato, Luc Girard, John D Minna and Takeshi Hisada; Supervision, Noriaki Sunaga, Kimihiro Shimizu, John D Minna and Takeshi Hisada; Funding acquisition, Noriaki Sunaga and John D Minna.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supporting information

Figure S1. CTNNB1 silencing with CTNNB1 siRNAs (siCTNNB1‐1 and siCTNNB1‐2) reduced LGR6 expressions in HCC15 and A427 cells. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Columns: Mean ± standard deviation. siCont: non‐targeting control siRNA. LGR6, leucine‐rich repeat‐containing G protein‐coupled receptor 6.

Figure S2. Representative images of LGR6 protein staining in lung adenocarcinomas with scores as follows: (a) score = 0, (b) score = 1, (c) score = 2, (d) score = 3, and (e) score = 4. LGR6, leucine‐rich repeat‐containing G protein‐coupled receptor 6.

Table S1. Gene expression profile compared with CTNNB1‐disrupted versus CTNNB1‐retained HCC15 cells.

Table S2. Cell lines used in the present study.

Table S3. Differentially expressed genes between floating versus adherent component A427 cells.

Table S4. Canonical pathways associated with sphere‐forming properties of A427 cells.

Table S5. LGR6 expression and clinicopathological factors in patients with pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors.

Table S6. Differentially expressed genes between LGR6‐silenced versus control siRNA‐treated HCC15 cells.

Table S7. Differentially expressed genes between LGR6‐silenced versus control siRNA‐treated A427 cells.

Table S8. Canonical pathways affected by LGR6 knockdown in HCC15 cells.

Table S9. Canonical pathways affected by LGR6 knockdown in A427 cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mr Yohei Morishita, Ms Yoko Yokoyama, Ms Hiroko Matsuda, and Ms Saori Umezawa for their technical support. We also thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing. The present study was conducted with financial support by Grants‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research (C) of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (17K09644 and 20K08533) and Lung Cancer SPORE (P50CA070907). Additionally, this work was conducted using research equipment shared with the MEXT Project for promoting public utilization of advanced research infrastructure (grant no. JPMXS0420600121), the Laboratory for Analytical Instruments, Education and Research Support Center, Gunma University Graduate School of Medicine. JDM receives royalties from the National Institutes of Health and University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas for the distribution of human tumor cell lines.

Sunaga N, Kaira K, Shimizu K, Tanaka I, Miura Y, Nakazawa S, et al. The oncogenic role of LGR6 overexpression induced by aberrant Wnt/β‐catenin signaling in lung cancer. Thorac Cancer. 2024;15(2):131–141. 10.1111/1759-7714.15169

REFERENCES

- 1. Torre LA, Siegel RL, Ward EM, Jemal A. Global cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends—an update. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:16–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: proposals for revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (eighth) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:39–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kris MG, Johnson BE, Berry LD, et al. Using multiplexed assays of oncogenic drivers in lung cancers to select targeted drugs. Jama. 2014;311:1998–2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sequist LV, Waltman BA, Dias‐Santagata D, et al. Genotypic and histological evolution of lung cancers acquiring resistance to EGFR inhibitors. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:75ra26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Onoi K, Chihara Y, Uchino J, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for lung cancer treatment: a review. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clevers H. Wnt/β‐catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127:469–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhong Z, Yu J, Virshup DM, Madan B. Wnts and the hallmarks of cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2020;39:625–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gao C, Wang Y, Broaddus R, Sun L, Xue F, Zhang W. Exon 3 mutations of CTNNB1 drive tumorigenesis: a review. Oncotarget. 2018;9:5492–5508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Galluzzi L, Spranger S, Fuchs E, López‐Soto A. WNT signaling in cancer immunosurveillance. Trends Cell Biol. 2019;29:44–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang H, Ou Q, Li D, et al. Genes associated with increased brain metastasis risk in non‐small cell lung cancer: comprehensive genomic profiling of 61 resected brain metastases versus primary non‐small cell lung cancer (Guangdong association study of thoracic oncology 1036). Cancer. 2019;125:3535–3544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhou C, Li W, Shao J, Zhao J, Chen C. Analysis of the clinicopathologic characteristics of lung adenocarcinoma with CTNNB1 mutation. Front Genet. 2019;10:1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhao J, Lin G, Zhuo M, et al. Next‐generation sequencing based mutation profiling reveals heterogeneity of clinical response and resistance to osimertinib. Lung Cancer. 2020;141:114–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sequist LV, Heist RS, Shaw AT, et al. Implementing multiplexed genotyping of non‐small‐cell lung cancers into routine clinical practice. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:2616–2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang J, Chen J, He J, et al. Wnt signaling as potential therapeutic target in lung cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2016;20:999–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sunaga N, Kohno T, Kolligs FT, Fearon ER, Saito R, Yokota J. Constitutive activation of the Wnt signaling pathway by CTNNB1 (β‐catenin) mutations in a subset of human lung adenocarcinoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2001;30:316–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shigemitsu K, Sekido Y, Usami N, et al. Genetic alteration of the β‐catenin gene (CTNNB1) in human lung cancer and malignant mesothelioma and identification of a new 3p21.3 homozygous deletion. Oncogene. 2001;20:4249–4257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sunaga N, Miura Y, Kaira K, Tsukagoshi Y, Sakurai R, Hisada T. LGR6 overexpression induced by constitutive activation of the Wnt signaling pathway in NSCLC cells. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:895–915. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hsu SY, Kudo M, Chen T, et al. The three subfamilies of leucine‐rich repeat‐containing G protein‐coupled receptors (LGR): identification of LGR6 and LGR7 and the signaling mechanism for LGR7. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:1257–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Warner ML, Bell T, Pioszak AA. Engineering high‐potency R‐spondin adult stem cell growth factors. Mol Pharmacol. 2015;87:410–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chai T, Shen Z, Zhang Z, et al. LGR6 is a potential diagnostic and prognostic marker for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Lab Anal. 2020;34:e23121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ehara T, Uehara T, Yoshizawa T, et al. High expression of LGR6 is a poor prognostic factor in esophageal carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract. 2023;242:154312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kong Y, Ou X, Li X, et al. LGR6 promotes tumor proliferation and metastasis through Wnt/β‐catenin signaling in triple‐negative breast cancer. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2020;18:351–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Feng Q, Li S, Ma HM, Yang WT, Zheng PS. LGR6 activates the Wnt/beta‐catenin signaling pathway and forms a β‐catenin/TCF7L2/LGR6 feedback loop in LGR6(high) cervical cancer stem cells. Oncogene. 2021;40:6103–6114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ruan X, Liu A, Zhong M, et al. Silencing LGR6 attenuates stemness and chemoresistance via inhibiting Wnt/β‐catenin signaling in ovarian cancer. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2019;14:94–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fan M, Liu S, Zhang L, et al. LGR6 acts as an oncogene and induces proliferation and migration of gastric cancer cells. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2022;32:11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ke J, Ma P, Chen J, Qin J, Qian H. LGR6 promotes the progression of gastric cancer through PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:3025–3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cheng YY, Yang X, Gao X, Song SX, Yang MF, Xie FM. LGR6 promotes glioblastoma malignancy and chemoresistance by activating the Akt signaling pathway. Exp Ther Med. 2021;22:1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McMillan EA, Ryu MJ, Diep CH, et al. Chemistry‐first approach for nomination of personalized treatment in lung cancer. Cell. 2018;173:864–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sunaga N, Miura Y, Tsukagoshi Y, et al. Dual inhibition of MEK and p38 impairs tumor growth in KRAS‐mutated non‐small cell lung cancer. Oncol Lett. 2019;17:3569–3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real‐time quantitative PCR and the 2(‐Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sunaga N, Miyajima K, Suzuki M, et al. Different roles for caveolin‐1 in the development of non‐small cell lung cancer versus small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4277–4285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tanaka I, Sato M, Kato T, et al. eIF2beta, a subunit of translation‐initiation factor EIF2, is a potential therapeutic target for non‐small cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:1843–1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sunaga N, Kaira K, Imai H, et al. Oncogenic KRAS‐induced epiregulin overexpression contributes to aggressive phenotype and is a promising therapeutic target in non‐small‐cell lung cancer. Oncogene. 2013;32:4034–4042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Miura Y, Kaira K, Sakurai R, et al. Prognostic effect of class III beta‐tubulin and topoisomerase‐II in patients with advanced thymic carcinoma who received combination chemotherapy, including taxanes or topoisomerase‐II inhibitors. Oncol Lett. 2017;14:2369–2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ohtaki Y, Kawabata‐Iwakawa R, Nobusawa S, et al. Molecular and expressional characterization of tumor heterogeneity in pulmonary carcinosarcoma. Mol Carcinog. 2022;61:924–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sun J, Nishiyama T, Shimizu K, Kadota K. TCC: an R package for comparing tag count data with robust normalization strategies. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Codony‐Servat J, Verlicchi A, Rosell R. Cancer stem cells in small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2016;5:16–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ishiguro T, Ohata H, Sato A, Yamawaki K, Enomoto T, Okamoto K. Tumor‐derived spheroids: relevance to cancer stem cells and clinical applications. Cancer Sci. 2017;108:283–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Leushacke M, Barker N. Lgr5 and Lgr6 as markers to study adult stem cell roles in self‐renewal and cancer. Oncogene. 2012;31:3009–3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Oeztuerk‐Winder F, Guinot A, Ochalek A, Ventura JJ. Regulation of human lung alveolar multipotent cells by a novel p38alpha MAPK/miR‐17‐92 axis. Embo J. 2012;31:3431–3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang Q, Han Z, Zhu Y, Chen J, Li W. Role of hypoxia inducible factor‐1 in cancer stem cells (review). Mol Med Rep. 2021;23:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chen J, Song W, Amato K. Eph receptor tyrosine kinases in cancer stem cells. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2015;26:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhao J, Chen X, Herjan T, Li X. The role of interleukin‐17 in tumor development and progression. J Exp Med. 2020;217:e20190297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yamamoto Y, Sakamoto M, Fujii G, et al. Overexpression of orphan G‐protein‐coupled receptor, Gpr49, in human hepatocellular carcinomas with beta‐catenin mutations. Hepatology. 2003;37:528–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Van der Flier LG, Sabates‐Bellver J, Oving I, et al. The intestinal Wnt/TCF signature. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:628–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Xu L, Lin W, Wen L, Li G. Lgr5 in cancer biology: functional identification of Lgr5 in cancer progression and potential opportunities for novel therapy. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. de Lau W, Peng WC, Gros P, Clevers H. The R‐spondin/Lgr5/Rnf43 module: regulator of Wnt signal strength. Genes Dev. 2014;28:305–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cortesi E, Ventura JJ. Lgr6: from stemness to cancer progression. J Lung Health Dis. 2019;3:12–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lee JH, Tammela T, Hofree M, et al. Anatomically and functionally distinct lung mesenchymal populations marked by Lgr5 and Lgr6. Cell. 2017;170:1149–1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhu S, Yang N, Niu C, et al. The miR‐145‐MMP1 axis is a critical regulator for imiquimod‐induced cancer stemness and chemoresistance. Pharmacol Res. 2022;179:106196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhang H, Hao C, Wang H, Shang H, Li Z. Carboxypeptidase A4 promotes proliferation and stem cell characteristics of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Exp Pathol. 2019;100:133–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhang M, Li X, Fan Z, et al. High SRPX2 protein expression predicts unfavorable clinical outcome in patients with prostate cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:3149–3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ryuge S, Sato Y, Jiang SX, et al. The clinicopathological significance of Lgr5 expression in lung adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2013;82:143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gao F, Zhou B, Xu JC, et al. The role of LGR5 and ALDH1A1 in non‐small cell lung cancer: cancer progression and prognosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;462:91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Guinot A, Oeztuerk‐Winder F, Ventura JJ. miR‐17‐92/p38alpha dysregulation enhances Wnt signaling and selects Lgr6+ cancer stem‐like cells during lung adenocarcinoma progression. Cancer Res. 2016;76:4012–4022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wang W, Ding S, Zhang H, Li J, Zhan J, Zhang H. G protein‐coupled receptor LGR6 is an independent risk factor for colon adenocarcinoma. Front Med. 2019;13:482–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wang Z, Pascal LE, Chandran UR, et al. ELL2 is required for the growth and survival of AR‐negative prostate cancer cells. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:4411–4427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Parveen SMA, Natani S, Sruthi KK, Khilar P, Ummanni R. HIF‐1alpha and Nrf2 regulates hypoxia induced overexpression of DDAH1 through promoter activation in prostate cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2022;147:106232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Barbutti I, Machado‐Neto JA, Arfelli VC, et al. The U2AF homology motif kinase 1 (UHMK1) is upregulated upon hematopoietic cell differentiation. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2018;1864:959–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Li Y, Wang S, Jin K, et al. UHMK1 promotes lung adenocarcinoma oncogenesis by regulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Thorac Cancer. 2023;14:1077–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chen TJ, Dehghanian SZ, Chan TC, et al. High G protein subunit beta 4 protein level is correlated to poor prognosis of urothelial carcinoma. Med Mol Morphol. 2021;54:356–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Xie F, Zhang D, Qian X, et al. Analysis of cancer‐promoting genes related to chemotherapy resistance in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Transl Med. 2022;10:92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Liu B, Chen L, Huang H, Huang H, Jin H, Fu C. Prognostic and immunological value of GNB4 in gastric cancer by analyzing TCGA database. Dis Markers. 2022;2022:7803642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wu ZH, Li C, Zhang YJ, Zhou W. Identification of a cancer stem cells signature of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Front Genet. 2022;13:814777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kikuchi A, Matsumoto S, Sada R. Dickkopf signaling, beyond Wnt‐mediated biology. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2022;125:55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Li MH, Dong LW, Li SX, et al. Expression of cytoskeleton‐associated protein 4 is related to lymphatic metastasis and indicates prognosis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma patients after surgery resection. Cancer Lett. 2013;337:248–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Li SX, Tang GS, Zhou DX, et al. Prognostic significance of cytoskeleton‐associated membrane protein 4 and its palmitoyl acyltransferase DHHC2 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2014;120:1520–1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Liu C, Ruan YQ, Qu LH, et al. Prognostic modeling of lung adenocarcinoma based on hypoxia and ferroptosis‐related genes. J Oncol. 2022;2022:1022580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. CTNNB1 silencing with CTNNB1 siRNAs (siCTNNB1‐1 and siCTNNB1‐2) reduced LGR6 expressions in HCC15 and A427 cells. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Columns: Mean ± standard deviation. siCont: non‐targeting control siRNA. LGR6, leucine‐rich repeat‐containing G protein‐coupled receptor 6.

Figure S2. Representative images of LGR6 protein staining in lung adenocarcinomas with scores as follows: (a) score = 0, (b) score = 1, (c) score = 2, (d) score = 3, and (e) score = 4. LGR6, leucine‐rich repeat‐containing G protein‐coupled receptor 6.

Table S1. Gene expression profile compared with CTNNB1‐disrupted versus CTNNB1‐retained HCC15 cells.

Table S2. Cell lines used in the present study.

Table S3. Differentially expressed genes between floating versus adherent component A427 cells.

Table S4. Canonical pathways associated with sphere‐forming properties of A427 cells.

Table S5. LGR6 expression and clinicopathological factors in patients with pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors.

Table S6. Differentially expressed genes between LGR6‐silenced versus control siRNA‐treated HCC15 cells.

Table S7. Differentially expressed genes between LGR6‐silenced versus control siRNA‐treated A427 cells.

Table S8. Canonical pathways affected by LGR6 knockdown in HCC15 cells.

Table S9. Canonical pathways affected by LGR6 knockdown in A427 cells.