Abstract

The overactivation of the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) promotes pathophysiological processes related to multiple physiological systems, including the heart, vasculature, adipose tissue and kidneys. The inhibition of the MR with classical MR antagonists (MRA) has successfully improved outcomes most evidently in heart failure. However, real and perceived risk of side effects and limited tolerability associated with classical MRA have represented barriers to implementing MRA in settings where they have been already proven efficacious (heart failure with reduced ejection fraction) and studying their potential role in settings where they might be beneficial but where risk of safety events is perceived to be higher (renal disease). Novel non-steroidal MRA have distinct properties that might translate into favourable clinical effects and better safety profiles as compared with MRA currently used in clinical practice. Randomised trials have shown benefits of non-steroidal MRA in a range of clinical contexts, including diabetic kidney disease, hypertension and heart failure. This review provides an overview of the literature on the systemic impact of MR overactivation across organ systems. Moreover, we summarise the evidence from preclinical studies and clinical trials that have set the stage for a potential new paradigm of MR antagonism.

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version of this article contains a slideset of the figures for download available at 10.1007/s00125-023-06031-1.

Keywords: Eplerenone, Finerenone, Mineralocorticoid receptor, Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, Review, Spironolactone

Introduction

The mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) plays a key role in human physiology where it regulates fluid, electrolyte and haemodynamic homeostasis. Overactivation of the MR has been demonstrated in individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus [1], and is associated with increased cardiovascular risk [2–4]. MR overactivation is increasingly recognised to induce inflammation and fibrosis in organ tissues, contributing to CKD and CVD progression, beyond the well-known effects on salt retention and hypertension. The MR has been a pharmacological target for nearly 70 years, although the initial use of MR antagonists (MRA) was primarily for diuretic purposes [5]. In contemporary practice, MRA play important therapeutic roles in resistant hypertension [6], heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF), where several trials have demonstrated benefits on morbidity and mortality [7–11]. However, real or perceived risk of side effects and tolerability issues associated with traditional steroidal MRA, such as worsening renal function and hyperkalaemia, often represents a barrier to their use in clinical practice [12–15]

Novel non-steroidal MRA have emerged as a promising alternative for targeting MR overactivation, with a better safety profile than traditional steroidal MRA, and demonstrated efficacy in patients with CKD and type 2 diabetes [16–18]. The aim of this review is to provide a comprehensive overview of MR overactivation and the status of non-steroidal MRA, their mechanisms of action, safety profile and therapeutic potential to target the systemic impact of MR overactivation.

Pathophysiology of MR overactivation

Historical overview

At the time of its first successful isolation and crystallisation in 1953 [19], aldosterone was primarily recognised as a promotor of renal sodium and fluid retention and potassium excretion [20]. In subsequent years, the compounds that were initially referred to as ‘aldosterone antagonists’ were increasingly understood to block a receptor (the MR) with binding affinity for not only aldosterone but also cortisol [21–24], and were thus more aptly called MRA. In 1987 an important milestone was reached with the cloning of the MR gene [25]. Today, it is accepted that mechanisms independent of aldosterone can contribute to MR activation, and that the role of the MR in disease progression goes beyond its well-known effects on salt and fluid homeostasis, and involves metabolic, proinflammatory and pro-fibrotic pathways [5, 24, 26–28].

Properties of the MR

The MR belongs to the steroid hormone intracellular receptor family [25, 26]. In its inactivated state, the MR is typically located in the cytoplasm. Its activation following the binding with its steroidal ligands (in human physiology these are mainly aldosterone and cortisol) facilitates its translocation into the cellular nucleus, where it forms complexes with a wide range of cofactors to regulate transcription [29, 30]. However, the MR also exhibits additional effects through pathways that are independent of gene transcription [30–34]. The MR is expressed in multiple organs throughout the body [26], including the kidneys [35–37], heart [36, 38–40], vasculature [36, 38, 41, 42], gastrointestinal tract [36], adipose tissue [43, 44] and central nervous system [36, 45]. The MR binds with similar affinity to cortisol and aldosterone in vitro, but its predominant ligands and functions in vivo are context-dependent according to its location in the body [26, 29, 30, 36, 46].

Renal and extra-renal effects of MR activation

Role of the MR in the kidney

In the kidney, the MR is classically characterised as a regulator of salt and fluid homeostasis [47]. This pathway begins with the production and secretion of aldosterone in the adrenal glands, mediated by activation of the renin–angiotensin system (RAS) in response to hyperkalaemia and hyponatraemia [47]. In renal epithelial cells, the enzyme 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (11β-HSD2) converts cortisol into cortisone, which does not bind to the MR, rendering aldosterone its primary ligand [46, 48]. In the distal nephron, MR activation by aldosterone promotes transcription and activity of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC), resulting in increased sodium and fluid retention and potassium excretion [30, 47]. While historically this is the most-attributed function of the renal MR, evidence from animal models implicates MR activation as an inductor of oxidative stress in the kidney [37], and a key mediator of renal inflammation and fibrosis [28, 49–52].

Role of the MR in the heart, immune cells, adipose tissue and vasculature

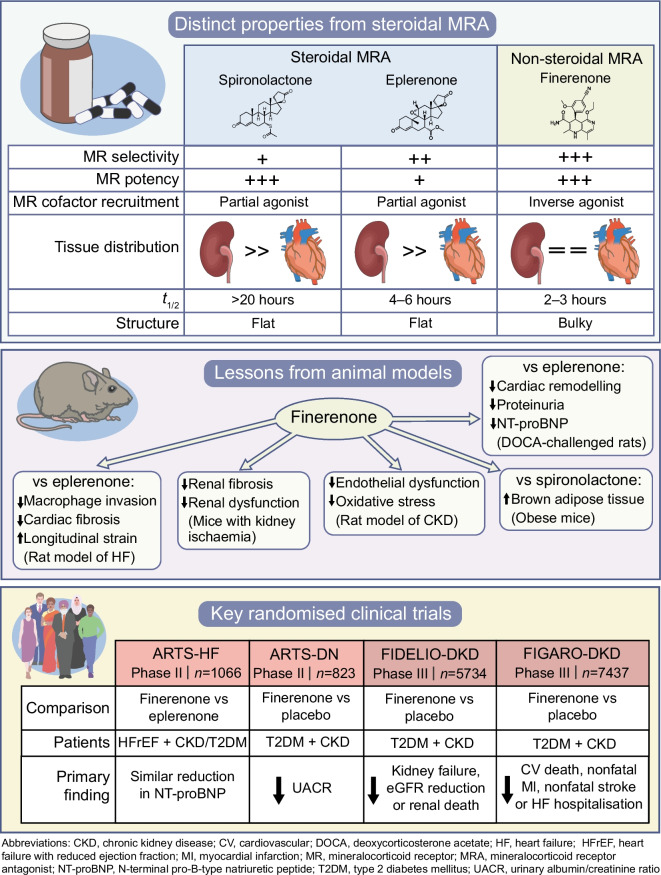

The potential systemic implications of MR overactivation become apparent when considering the diverse roles of the MR in organs other than the kidneys (Fig. 1) [26]. In cardiomyocytes, where the expression of the MR is not accompanied by the cortisol-converting enzyme 11β-HSD2 [46, 48], cortisol may be a more predominant ligand for the MR. The first suggestion of MR activation as a promotor of cardiac fibrosis originated from the work of Selye in 1958 [53], where the administration of a mineralocorticoid agent in dogs resulted in cardiac necrosis and subsequent fibrotic scarring. Similar findings were later reported in studies of rodents [54, 55]. Immune cell MR activity may play a role in this phenomenon; in mice, macrophage-specific deletion of MR protected against deoxycorticosterone/salt-induced cardiac fibrosis [56]. More recently, knockout of MR in cardiomyocytes and T cells has been shown to improve post-myocardial infarction ventricular remodelling [39, 57]. Insulin resistance, inflammation and adipocyte dysfunction improve with MR blockade in mice [58–61]. Human adipocytes express MRs and have the capacity for aldosterone production [62, 63]. The link between MR activation and insulin resistance has been reported in individuals with primary aldosteronism [64, 65], hypertension [66], CKD [67] and heart failure [63, 68]. In the hypothalamus, MR activation may increase sympathetic drive [69]. The activation of MRs in vascular smooth muscle cells may contribute to vascular oxidative stress, ageing and stiffening [70–72].

Fig. 1.

Role of MR overactivation in cardiorenal disease. ROS, reactive oxygen species. This figure is available as part of a downloadable slideset

Mechanisms of MR overactivation

MR overactivation may arise from both aldosterone-mediated and aldosterone-independent pathways, including by cortisol-ligand activation in cells deficient of the cortisol-converting enzyme 11β-HSD2, such as cardiomyocytes [46, 48, 73]. The relationship between falling GFR and increasing aldosterone levels may predispose individuals with CKD to MR overactivation [74]. Treatment with RAS-inhibitors, which is recommended in CKD, hypertension and heart failure, may contribute to long-term elevated aldosterone levels known as ‘aldosterone breakthrough’ or ‘aldosterone escape’ in 30–40% of patients [50, 75–80]. Moreover, adipocyte aldosterone production may contribute to increased MR activation in obese individuals [62, 81], which may be reversed by weight loss [82].

Therapeutic targeting of MR overactivation

Steroidal MRA

Steroidal MRA in heart failure

Following the development of the first steroidal MRA in the 1950s [83, 84], spironolactone became available in 1960 primarily as a diuretic in patients with oedema, primary aldosteronism and essential hypertension [24, 85]. In recent decades, the indications of steroidal MRA have broadened, reflecting the wider implications of MR inhibition, with perhaps their most far-reaching impact to date in heart failure [7]. In 1999, the RALES RCT demonstrated a 30% reduction in mortality and a 35% reduction in risk of hospitalisation due to heart failure with spironolactone vs placebo in 1663 patients with severe HFrEF [9]. Following RALES, several landmark trials have established the efficacy of the steroidal MRA spironolactone and eplerenone in reducing morbidity and mortality in patients with HFrEF or HFmrEF (Table 1) [8–11].

Table 1.

Key RCTs on steroidal and non-steroidal MRA in CV and renal disease

| Trial | Design | Comparison | Key selection criteria | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFrEF | ||||

| Steroidal MRA | ||||

| RALES (n=1663) [9] | RCT, Phase III, double-blinded | Spironolactone vs placebo | HF, NYHA III–IV, EF ≤35%. Serum creatinine ≤221 μmol/l, serum K+ ≤5.0 mmol/l. |

Efficacy: Spironolactone reduced all-cause mortality (RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.60, 0.82). Safety: K+ ≥6.0 mmol/l occurred in 2% (spironolactone) vs 1% (placebo). |

| EMPHASIS-HF (n=2737) [8] | RCT, Phase III, double-blinded | Eplerenone vs placebo | HF, NYHA II, EF ≤30% (or 30–30% if QRS duration >130 ms). eGFR ≥30 ml/min per 1.73 m2, serum K+ ≤5.0 mmol/l. |

Efficacy: Eplerenone reduced the primary composite of CV death or HF hospitalisation (HR 0.63, 95% CI 0.54, 0.74). Safety: K+ ≥5.5 mmol/l occurred in 11.8% (eplerenone) vs 7.2% (placebo). |

| Non-steroidal MRA | ||||

| ARTS-HF (n=1066) [127] | RCT, Phase IIb, double-blinded, dose-finding | Finerenone vs eplerenone | HF, EF ≤40%, within 7 days of worsening HF event and co-existing moderate CKD (eGFR 30–60 ml/min per 1.73 m2) and/or T2DM. Serum K+ ≤5.0 mmol/l. |

Efficacy: There was no difference between finerenone and eplerenone on the primary outcome (percentage of patients with >30% reduction in NT-proBNP at 90 days). The exploratory secondary composite endpoint of all-cause death, CV hospitalisation, or emergency visit for HF was significantly lower (HR 0.56, 95% CI 0.35, 0.90) in the 10–20 mg finerenone group. Safety: K+ ≥5.6 mmol/l occurred in 4.3% overall, with similar incidence across eplerenone and finerenone arms. |

| HFpEF | ||||

| Steroidal MRA | ||||

| Aldo-DHF (n=422) [86] | RCT, Phase II, double-blinded | Spironolactone vs placebo | Ambulatory patients with HF, NYHA II–III, EF ≥50% and evidence of diastolic dysfunction. eGFR ≥30 ml/min per 1.73 m2, serum K+ <5.1 mmol/l. |

Efficacy: Spironolactone improved E/e' (adjusted mean difference vs placebo, −1.5, 95% CI −2.0, −0.9) but did not affect peak VO2 (co-primary endpoints). Safety: K+ >5.5 mmol/l occurred in 2% (spironolactone) vs 1% (placebo). |

| TOPCAT (n=3445) [87] | RCT, Phase III, double-blinded | Spironolactone vs placebo | Symptomatic HF, EF ≥45%. eGFR ≥30 ml/min per 1.73 m2, serum K+ <5.0 mmol/l. |

Efficacy: No difference in the primary composite of CV death, aborted cardiac arrest or HF hospitalisation (HR 0.89, 95% CI 0.77, 1.04). The exploratory secondary outcome of HF hospitalisations were lower in the spironolactone arm (HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.69, 0.99). Safety: K+ ≥5.5 mmol/l occurred in 18.7% (spironolactone) vs 9.1% (placebo). |

| Post-MI | ||||

| Steroidal MRA | ||||

| EPHESUS (n=6642) [10] | RCT, Phase III, double-blinded | Eplerenone vs placebo | Within 3 to 14 days of acute MI (ST-elevation or non-ST-elevation), as well as HF, EF ≤40%. Serum creatinine ≤220 μmol/l, serum K+ ≤5.0 mmol/l. |

Efficacy: Eplerenone reduced all-cause mortality (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.75, 0.96). Safety: K+ ≥6.0 mmol/l occurred in 5.5% (eplerenone) vs 3.9% (placebo). |

| ALBATROSS (n=1603) [143] | RCT, Phase III, open label | Spironolactone open label | Within 72 h of acute MI (ST-elevation or non-ST-elevation) irrespective of EF. eGFR ≥30 ml/min per 1.73 m2, serum K+ ≤5.5 mmol/l. |

Efficacy: No difference in the primary composite of death, resuscitated cardiac arrest, significant ventricular arrhythmia, indication for implantable defibrillator, or new or worsening HF at 6 month follow-up (HR 0.97, 95% CI 0.73, 1.28). Safety: K+ >5.5 mmol/l occurred in 3% (spironolactone) vs 0.5% (standard of care). |

| REMINDER (n=1012) [144] | RCT, double-blinded | Eplerenone vs placebo | Within 24 h of ST-elevation MI without prior history of HF or previously known EF <40%. eGFR >30 ml/min per 1.73m2. |

Efficacy: The primary composite (CV mortality, re-hospitalisation or extended initial hospital stay due to HF, sustained ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation, EF ≤40%, or elevated natriuretic peptides at ≥1 month) was lowered by eplerenone (HR 0.58, 95% CI 0.45, 0.76). Safety: K+ >5.5 mmol/l occurred in 5.6% (eplerenone) vs 3.2% (placebo). |

| Hypertension | ||||

| Steroidal MRA | ||||

| PATHWAY-2 (n=335) [6] | RCT, double-blinded, cross-over design | Spironolactone vs placebo, bisoprolol and doxazosin | Seated clinic systolic BP ≥140 mmHg (or ≥135 mmHg in diabetes) and home systolic BP ≥130 mmHg, despite treatment with maximally tolerated doses of a RAS inhibitor, a CCB and a diuretic. eGFR ≥30 ml/min per 1.73 m2, serum K+ within normal range. |

Efficacy: Spironolactone was superior in lowering BP vs placebo (–8.70 mmHg, 95% CI −9.72, −7.69), bisoprolol (–4.48, 95% CI –5.50, −3.46), and doxazosin (–4.03, 95% CI –5.04, −3.02). Safety: K+ increased 0.43 mmol/l but with no cases of incident hyperkalaemia in the spironolactone arm. |

| Non-steroidal MRA | ||||

| ESAX-HTN (n=1001) [135] | RCT, Phase III, double-blinded, dose-finding | Esaxerenone vs eplerenone | Patients with essential hypertension (systolic/diastolic BP 140–179/90–109). eGFR ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, serum K+ <5.1 mmol/l. |

Efficacy: The primary endpoints (changes in sitting systolic or diastolic BP at 12 weeks) vs eplerenone 50 mg were unchanged by esaxerenone 2.5 mg but improved by esaxerenone 5 mg. Safety: K+ ≥5.5 mmol/l twice consecutively occurred in 0.6% (esaxerenone 2.5 mg) vs 0.3% (esaxerenone 5 mg) vs 0% (eplerenone 50 mg). |

| CKD | ||||

| Non-steroidal MRA | ||||

| ARTS-DN (n=823) [128] | RCT, Phase IIb, double-blinded, dose-finding | Finerenone vs placebo | T2DM, UACR ≥3.39 mg/mmol (30 mg/g) and an eGFR >30 ml/min per 1.73 m2; treated with at least the minimum recommended dosage of an RAS blocker prior to the screening. Serum K+ ≤4.8 mmol/l. |

Efficacy: There was a dose-dependent improvement in the primary outcome (ratio of UACR at day 90 vs baseline) vs placebo at finerenone doses 7.5–20 mg/day, ranging from 21% reduction in the 7.5 mg finerenone group to 38% reduction in the 20 mg finerenone group. Safety: K+ ≥5.6 mmol/l occurred in 0% (placebo), 2.1% (finerenone 1.25 mg), 1.1% (finerenone 2.5 mg), 1.0% (finerenone 5 mg), 2.1% (finerenone 7.5 mg), 3.2% (finerenone 1.5 mg) and 1.7% (finerenone 20 mg). |

| FIDELIO-DKD (n=5734) [16] | RCT, Phase III, double-blinded | Finerenone vs placebo | T2DM, CKD (either: (1) persistent UACR 3.39-33.9 mg/mmol (30–300 mg/g), eGFR 25–60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and history of diabetic retinopathy; or (2) persistent UACR 33.9-565 mg/mmol (300–5000 mg/g) and eGFR 25–75 ml/min per 1.73 m2), RAS blocker therapy, serum potassium ≤4.8 mmol/l, no diagnosis of symptomatic chronic HFrEF. |

Efficacy: Finerenone reduced risk of the primary composite of kidney failure (eGFR <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2, long-term dialysis or kidney transplantation), a sustained >40% reduction in eGFR or death from renal causes (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.73, 0.93). Safety: Treatment discontinuation due to hyperkalaemia occurred in 2.3% (finerenone) vs 0.9% (placebo). |

| FIGARO-DKD (n=7437) [17] | RCT, Phase III, double-blinded | Finerenone vs placebo | T2DM, CKD (either: (1) persistent UACR 3.39-33.9 mg/mmol (30–300 mg/g), eGFR 25–90 ml/min per 1.73 m2; or (2) persistent UACR 33.9-565 mg/mmol (300–5000 mg/g) and eGFR ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2), RAS blocker therapy, serum potassium ≤4.8 mmol/l, no diagnosis of symptomatic chronic HFrEF. |

Efficacy: Finerenone reduced risk of the primary composite of CV death, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke or HF hospitalisation (HR 0.87; 95% CI 0.76, 0.98). Safety: Treatment discontinuation due to hyperkalaemia occurred in 1.2% (finerenone) vs 0.4% (placebo). |

| ESAX-DN [136] | RCT, Phase III, double-blinded | Esaxerenone vs placebo | T2DM, hypertension, RAS blocker therapy, UACR 5.09-33.79 mg/mmol (45–299 mg/g), eGFR ≥30 ml/min per 1.73 m2). Serum K+ ≥3.5 and <5.0 mmol/l. |

Efficacy: The primary outcome (the proportion of patients achieving UACR remission) was lowered by esaxerone (absolute difference 18%; 95% CI 12%, 25%). Safety: K+ ≥6.0 mmol/l or ≥5.5 mmol/l twice consecutively occurred in 9% (esaxerenone) vs 2% (placebo). |

| End-stage renal disease | ||||

| Steroidal MRA | ||||

| DOHAS (n=309) [112] | RCT, open label | Spironolactone open label | 4-h-long HD 3 times/week for 4 years, serum potassium <6.5 mmol/l, 24 h urinary output <500 ml. |

Efficacy: The primary composite of CCV deaths or CCV hospitalisations was lowered by spironolactone (HR 0.404, 95% CI 0.202, 0.809). Safety: Serious hyperkalaemia led to discontinuation in three patients (1.9%) in the spironolactone arm. |

| Spin-D (n=129) [113] | RCT, double-blinded, multiple dosage | Spironolactone vs placebo | Maintenance HD for ≥6 months (or for 3–6 months if there were no changes in target dry weight in past 2 weeks and no hospitalisations in past 6 weeks), serum potassium <6.5 mmol/l. | Safety: The primary safety endpoints of hyperkalaemia (potassium >6.5 mmol/l) and hypotension events were similar with placebo and the overall spironolactone arm, but hyperkalaemia events increased with the spironolactone dose (0.50, 0.32, 0.23 and 0.89 events per patient-year in the placebo, 12.5 mg, 25 mg and 50 mg groups, respectively). |

| MiREnDa (n=97) [114] | RCT, double-blinded | Spironolactone vs placebo | Maintenance HD, no MRA treatment within the last 6 months, no history of hyperkalaemia (potassium ≥6.5 mmol/l). |

Efficacy: There was no difference in the primary efficacy endpoint of change in LVMi. Safety: Moderate hyperkalaemia episodes (6.0–6.5 mmol/l), but not severe (≥6.5 mmol/l), occurred more frequently with spironolactone (155 vs 80 events, p=0.034). |

CCB, calcium channel blocker; CCV, cerebral or cardiovascular; CV, cardiovascular; EF, ejection fraction; HD, haemodialysis; HF, heart failure; LVMi, left ventricular mass index; MI, myocardial infarction; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus

The findings in HFrEF/HFmrEF have not been convincingly translated to patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). The Aldo-DHF trial randomised 422 patients with chronic New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II–III heart failure with ejection fraction ≥50% and diastolic dysfunction to receive spironolactone or placebo. Spironolactone improved diastolic function, but had no effect on exercise capacity, symptoms or quality of life [86]. The subsequent larger TOPCAT trial randomised 3445 patients with symptomatic heart failure and an ejection fraction ≥45% to receive spironolactone or placebo, and barely missed its primary composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, aborted cardiac arrest and heart hospitalisation due to heart failure [87]. The near-miss in TOPCAT was met with debate concerning methodological and conduct issues, leaving many to consider the question of steroidal MRA in HFpEF yet unanswered [88]. Two ongoing RCTs aim to resolve the question of steroidal MRA in HFpEF (SPIRIT-HF: NCT04727073; SPIRRIT-HFpEF: NCT02901184) (Table 2) [89, 90].

Table 2.

Key ongoing and awaited RCTs targeting MR/aldosterone pathways in cardiovascular and renal disease

| RCT, NCT number |

Description (estimated enrolment) | Projected read-out |

|---|---|---|

| Steroidal MRA | ||

| SPIRIT-HF, NCT04727073 | Double-blind RCT comparing spironolactone against placebo in HF and EF ≥40% (n=1300) | 2024 |

| ALCHEMIST, NCT01848639 | Double-blind RCT comparing spironolactone against placebo in patients on chronic HD (n=825) | 2024 |

| ACHIEVE, NCT03020303 | Double-blind RCT comparing spironolactone against placebo in patients on HD or PD (n=2750) | 2025 |

| SPIRRIT, NCT02901184 | Open label registry-based RCT on spironolactone initiation in patients with HF and EF ≥40% (n=2000) | 2026 |

| Non-steroidal MRA | ||

| FINEARTS-HF, NCT04435626 | Double-blind RCT comparing finerenone against placebo in patients with HF and EF ≥40% (n=6016) | 2024 |

| CONFIDENCE, NCT05254002 | Double-blind RCT comparing finerenone and dapagliflozin against finerenone alone and dapagliflozin alone in patients with DKD (n=807) | 2024 |

| CLARION-CKD, NCT04968184 | Double-blind RCT comparing KBP-5074 (a novel non-steroidal MRA) against placebo in patients with uncontrolled hypertension and CKD stages 3b/4 (n=600) | 2025 |

| FIND-CKD, NCT05047263 | Double-blind RCT comparing finerenone against placebo in patients with non-diabetic CKD (n=1574) | 2026 |

| FIONA, NCT05196035 | Double-blind RCT comparing finerenone against placebo in children (age 6 months to 17 years) with CKD (n=219) | 2027 |

| Non-steroidal MR modulators | ||

| MIRACLE, NCT04595370 | Double-blind dose-finding RCT comparing balcinrenone (AZD9977, a novel non-steroidal MR modulator) in different doses together with daplagliflozin against dapagliflozin alone in patients with HF, EF <60% and CKD (eGFR 20–60 ml/min per 1.73m2; n=147) | 2023 |

| Aldosterone synthase inhibitors | ||

| NCT05182840 | Double-blind dose-finding RCT comparing BI 690517 (a novel aldosterone synthase inhibitor) with or without empagliflozin against placebo in patients with CKD (n=714) | 2023 |

CV, cardiovascular; DKD, diabetic kidney disease; EF, ejection fraction; HD, haemodialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis; HF, heart failure; NCT number, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus

Side-effect profile and barriers to implementation of steroidal MRA in heart failure

Spironolactone is structurally similar to progesterone and is a potent but unspecific antagonist of the MR [91]. Accordingly, gynaecomastia and breast pain have been known side effects of spironolactone since the 1960s [92]. Such side effects occurred in 10% vs 1% the spironolactone vs placebo arms of RALES [9]. Compared with spironolactone, eplerenone is a highly specific steroidal MRA, and accordingly has a more favourable anti-androgenic side-effect profile [93]. In the EPHESUS trial, the eplerenone and placebo arms showed similar rates of gynaecomastia and impotence [10]. Another limitation of steroidal MRA is the associated increase in potassium levels and therefore the risk of hyperkalaemic events [94]. The increase in prescriptions of spironolactone following the publication of RALES led to a higher incidence of hyperkalaemia in real-world data [95]. While hyperkalaemia is associated with arrhythmias and mortality [96–98], part of its prognostic impact in heart failure may stem from its link with the discontinuation of treatment with MRA [13, 99]. This hypothesis was behind the rationale for the DIAMOND trial, which demonstrated that the novel potassium-binder patiromer facilitated MRA use in patients with HFrEF with current or previous hyperkalaemia [100]. Despite constituting one of the four pillars of evidence-based pharmacotherapy for HFrEF [7], real and perceived risk of hyperkalaemia-related adverse events associated with steroidal MRA remains a barrier to their widespread implementation in clinical practice. Even mild degrees of CKD, where their efficacy on mortality/morbidity has been proven, are associated with greater underuse [101]. A recently published post hoc analysis of the EMPHASIS-HF and TOPCAT trials reported that MRA use was associated with an approximately 2 ml/min per 1.73 m2 initial decline in eGFR during the initial 4–6 months, but was without apparent long-term effects on renal function [102]. Routine care data from different healthcare systems indicate that only 37–40% of patients with HFrEF receive a steroidal MRA [13, 14], and discontinuation of treatment is common [103].

Steroidal MRA in CKD

Small trials demonstrating renal benefits of MR blockade in animal models of kidney disease [104, 105], and of steroidal MRA on reducing proteinuria in patients with CKD [106, 107], prompted optimism surrounding their potential use in nephrology [108]. A meta-analysis pooling data from 22 RCTs assessing non-selective steroidal MRA (1441 participants) and six studies assessing selective steroidal MRA (925 participants) in the setting of proteinuric CKD stages I–IV showed beneficial effects on proteinuria but increased risk of hyperkalaemia and acute kidney injury, and uncertain effects on GFR [109]. None of the included studies had a follow-up longer than 12 months. These findings are in overall agreement with previous meta-analyses on steroidal MRA in CKD [110, 111]; thus, there has been insufficient data to estimate effects on hard renal or mortality endpoints.

Few studies have assessed safety and efficacy of steroidal MRA in patients on dialysis. The 2014 Dialysis Outcomes Heart Failure Aldactone Study (DOHAS) randomly assigned spironolactone in 309 patients with oligoanuric haemodialysis, and showed a striking 60% reduction in the primary composite outcome of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular mortality and hospitalisations during the 3 year follow-up [112]. However, the study was limited by an open-label design. Two subsequent RCTs, the Spin-D (n=129, 36 week follow-up) and MiREnDa (n=97, 40 week follow-up) trials, found that spironolactone compared with placebo resulted in increases in potassium levels and moderate hyperkalaemia events, but no significant differences in severe hyperkalaemia (potassium ≥6.5 mmol/l) [113, 114]. While these trials suggested spironolactone to be reasonably safe provided there is stringent monitoring, there were no effects on left ventricular mass index or function. A Cochrane meta-analysis summarised the evidence from 16 RCTs including a total of 1446 patients with CKD requiring dialysis, suggesting that spironolactone likely reduces cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in this context (RR 0.37; 95% CI 0.22, 0.64) but somehow with an increase in risk of hyperkalaemia (RR 1.41; 95% CI 0.72, 2.78) [115]. The ongoing ALCHEMIST (NCT01848639) and ACHIEVE (NCT00277693) trials aim to further establish the safety and efficacy of steroidal MRA in patients undergoing haemodialysis.

Non-steroidal MRA

The clearly demonstrated clinical benefits of steroidal MRA, together with their limited use due to their actual or perceived safety profile, stimulated research aiming to inhibit the MR while maintaining a better safety profile. Among non-steroidal compounds, dihydropyridine-based antagonists displayed high MR potency and selectivity. The dihydropyridine-derivative BAY 94–8862 (today known as finerenone) was identified as a novel non-steroidal MRA that at least matched spironolactone in its potency, while displaying unprecedented selectivity to the MR in vitro, and promising efficacy vs eplerenone in preclinical animal models in vivo [116].

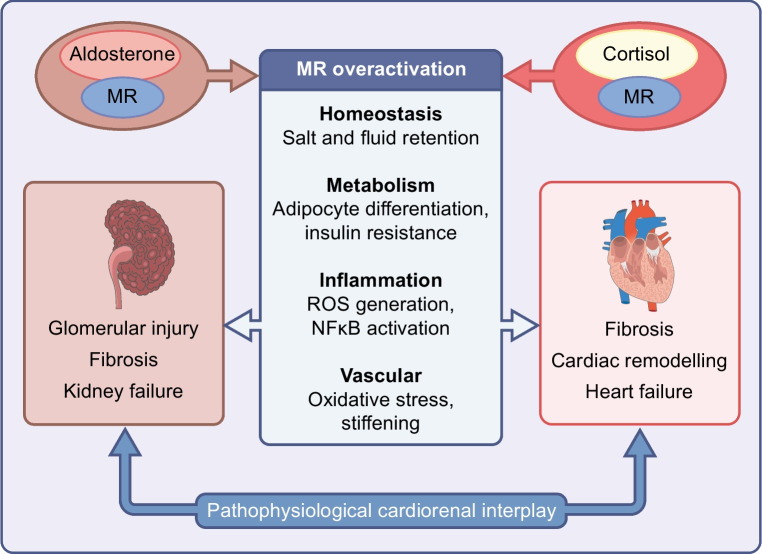

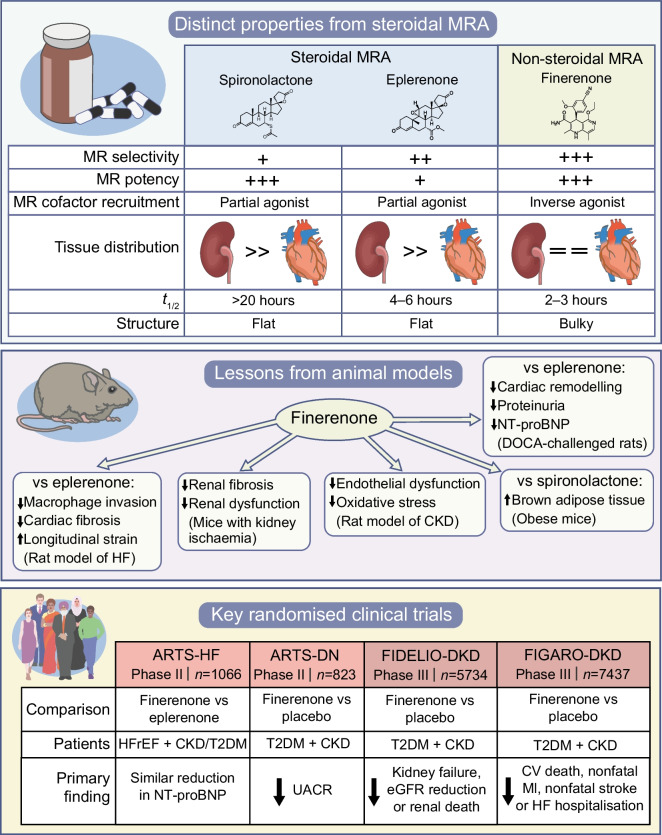

Distinct characteristics of non-steroidal MRA

Beyond its MR-selectivity and potency, finerenone carries several attributes that could lead to different clinical effects as compared with spironolactone and eplerenone (Fig. 2). First, upon binding the MR, steroidal MRA convey partial agonism on the MR cofactor recruitment. Since this partial agonism is less potent than the one exerted by aldosterone, spironolactone and eplerenone exhibit an antagonistic effect that is mainly apparent in the presence of aldosterone. In contrast, finerenone acts as an inverse agonist ligand, i.e. it reduces MR cofactor recruitment even in the absence of aldosterone [5, 117]. Second, while the tissue distribution of steroidal MRA is more concentrated in the kidneys, finerenone displays a balanced distribution in the heart and the kidneys [118], potentially enhancing the inhibition of proinflammatory and pro-fibrotic effects of cardiac MR activation. Third, the shorter plasma t½ of finerenone (2–3 h) compared with eplerenone (4–6 h) and spironolactone (long) might translate into a lower risk for hyperkalaemic events [119].

Fig. 2.

Distinct characteristics and mechanisms of finerenone vs classical steroidal MRA. CV, cardiovascular; DOCA, deoxycorticosterone acetate; HF, heart failure; MI, myocardial infarction; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus. This figure is available as part of a downloadable slideset

Several studies in animal models support the idea that the distinct properties of finerenone might translate into clinical benefits. Finerenone improved cardiac remodelling, natriuretic peptide concentrations and proteinuria to a greater degree than eplerenone in deoxycorticosterone acetate-/salt-challenged rats [118]. Finerenone, but not eplerenone, also improved systolic and diastolic function and reduced natriuretic peptides in rats with heart failure induced by coronary artery ligation [118]. In a mouse model of cardiac fibrosis, finerenone, but not eplerenone, inhibited macrophage invasion and improved cardiac fibrosis. It also improved global longitudinal peak strain more than eplerenone [120]. In mice exposed to kidney ischaemia, finerenone protected against subsequent renal fibrosis and dysfunction [121, 122]. In a model of CKD induced by endothelial dysfunction, reduced oxidative stress appeared to mediate the effect of finerenone on improved endothelial dysfunction [123]. One recent study on obese mice showed that finerenone, but not spironolactone, enhanced the activation of brown adipose tissue [124]. Interestingly, in a model of hypertension-induced end-organ damage, a synergistic effect between the sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT2i) empagliflozin and finerenone was observed in the improvement of proteinuria, serum creatinine levels, histopathological signs of cardiac and renal lesions, and mortality [125].

Randomised evidence on non-steroidal MRA

Phase II trials

Following promising preclinical results, finerenone was investigated in the MR Antagonist Tolerability Study (ARTS) Phase II RCT. ARTS part B enrolled 392 patients with HFrEF (ejection fraction ≤40%), NYHA class II–III and an eGFR 30–60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and randomised the participants to different doses of finerenone or placebo and active treatment with spironolactone. During the 4 week follow-up, hyperkalaemia occurred less frequently in the finerenone (5.3%) than the spironolactone arm (12.7%), as did renal impairment (3.8% vs 28.6%). Finerenone and spironolactone demonstrated similar improvements in natriuretic peptides and albuminuria [126].

ARTS was followed by the larger ARTS-HF multicentre Phase IIb dose-finding study comparing finerenone with eplerenone in patients with worsening HFrEF and concomitant moderate CKD and/or type 2 diabetes (i.e. eGFR >30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 in type 2 diabetes or 30–60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 without type 2 diabetes). In 1066 randomised patients, during 90 days follow-up the eplerenone and finerenone dose groups showed similar frequency of the primary outcome (the percentage of patients with >30% reduction in N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide [NT-proBNP] at 90 days), as well as of the key safety endpoint of hyperkalaemia (4.7% incidence in the eplerenone arm and 3.6–6.3% in the finerenone dose arms). Despite the short 90 day follow-up, the exploratory secondary composite endpoint of all-cause death, cardiovascular hospitalisation or emergency visit for heart failure was significantly lower (HR 0.56; 95% CI 0.35, 0.90) in the group assigned to finerenone 10 mg followed by up-titration to 20 mg at day 30 vs eplerenone [127].

ARTS-Diabetic Nephropathy (ARTS-DN) compared finerenone at different doses with placebo in 823 patients with type 2 diabetes, albuminuria (urinary albumin/creatinine ratio [UACR] ≥3.39 mg/mmol [30 mg/g]), eGFR >30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and with a concomitant RAS blocker prior to screening. The trial demonstrated a dose-dependent reduction in UACR with finerenone at the dosages 7.5–20 mg/day, as compared with placebo, ranging from 21% reduction in the 7.5 mg finerenone group to 38% reduction in the 20 mg finerenone group. In the trial, which excluded patients with serum potassium >4.8 mmol/l at screening, finerenone discontinuation due to hyperkalaemia occurred in only 1.8% of patients at doses 7.5–20 mg/day [128].

Phase III trials

Two double-blind RCTs were launched as part of the Phase III programme to assess the safety and efficacy of finerenone in CKD with type 2 diabetes in terms of renal (FInerenone in reducing kiDnEy faiLure and dIsease prOgression in DKD [FIDELIO-DKD]) and cardiovascular endpoints (FInerenone in reducinG cArdiovascular moRtality and mOrbidity in DKD [FIGARO-DKD]) [16, 17].

FIDELIO-DKD enrolled 5734 patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD who were treated with a RAS blocker [16]. The CKD inclusion criteria was met if either of the following was fulfilled: (1) persistent moderate albuminuria (UACR 3.39–33.9 mg/mmol [30–300 mg/g]), eGFR 25–60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and history of diabetic retinopathy; or (2) persistent severe albuminuria (UACR 33.9–565 mg/mmol [300–5000 mg/g]), and eGFR 25–75 ml/min per 1.73 m2. As in previous trials of the finerenone programme, patients were excluded if serum potassium was >4.8 mmol/l. Another key exclusion criterion was symptomatic chronic HFrEF, which comes with a class 1A recommendation for steroidal MRA [7]. The primary endpoint was the composite of kidney failure (eGFR <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2, long-term dialysis or kidney transplantation), a sustained >40% reduction in eGFR, or death from renal causes. Finerenone was associated with an 18% reduction of the primary outcome vs placebo during 2.6 years median follow-up, with consistent effects across patient subgroups. Finerenone also reduced by 14% the pre-specified secondary endpoint of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke or hospitalisation due to heart failure. Hyperkalaemia leading to treatment discontinuation was 2.3% with finerenone and 0.9% with placebo [16].

The purpose of the FIGARO-DKD (n=7437) trial was to preferentially examine cardiovascular, rather than renal, outcomes. Accordingly, while other inclusion criteria were similar between FIGARO-DKD and FIDELIO-DKD, the CKD criterion in FIGARO-DKD was less stringent in selecting for renal disease. CKD in FIGARO-DKD was considered fulfilled if either of the following were met: (1) persistent moderate albuminuria (UACR 3.39–33.9 mg/mmol [30–300 mg/g]) and eGFR 25–90 ml/min per 1.73 m2; or (2) persistent severe albuminuria (UACR 33.9–565 mg/mmol [300–5000 mg/g]) and eGFR ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. The primary composite outcome (cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke or hospitalisation due to heart failure) was reduced by 13% in the finerenone arm during 3.4 years median follow-up. Despite the exclusion of patients with HFrEF, a 29% reduction in hospitalisations due to heart failure was the main driver. Similarly, as in the previous finerenone trials, incidence of hyperkalaemia-related discontinuation was low (1.2%) and the rates of adverse events were similar across study arms [17].

The finerenone in CKD and type 2 diabetes: combined FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD trial programme analysis (FIDELITY) was a pooled analysis from both trials, including data from 13,026 patients and a median follow-up of 3.0 years. Finerenone reduced risk of the composite cardiovascular outcome (cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke or hospitalisation due to heart failure) by 14% and of the composite renal outcome (kidney failure, a sustained ≥57% decrease in eGFR from baseline over ≥4 weeks or renal death) by 23% [18]. The mean 4 month change in UACR was 32% lower with finerenone vs placebo [18]. Benefits with finerenone on heart failure outcomes (first hospitalisation due to heart failure; cardiovascular death or first hospitalisation due to heart failure; recurrent hospitalisations due to heart failure; and cardiovascular death or recurrent hospitalisations due to heart failure) were consistent across eGFR and/or UACR categories [129]. Post hoc analyses from the finerenone Phase III programme have suggested that finerenone might decrease the incidence of heart failure [130] and atrial fibrillation [131]. A pre-specified FIDELIO-DKD subgroup analysis did not detect any effect modification on the composite cardiovascular outcome according to history of heart failure (heart failure: HR 0.73; no heart failure: HR 0.90; p-interaction: 0.33) [132]. Importantly, since patients with HFrEF were excluded from the trial, the patients in the heart failure group predominantly had HFpEF, where steroidal MRA have not proven efficacious [87]. The ongoing FINEARTS (NCT04435626) trial will compare finerenone with placebo in 6000 patients with HFmrEF or HFpEF, and is expected to be finalised in 2024. Preclinical models suggested a synergistic effect with concomitant SGLT2i and finerenone use [125]. However, a FIDELITY subgroup analysis did not detect significant interaction with SGLT2i use on the cardiovascular composite (SGLT2i: HR 0.67; no SGLT2i: HR 0.87; p-interaction: 0.46) or the renal composite (SGLT2i: HR 0.42; no SGLT2i: HR 0.80; p-interaction: 0.29). However, only 6.7% of patients received an SGLT2i at baseline, and 8.5% initiated during the trial [133]. The ongoing CONFIDENCE (NCT05254002) trial will randomly assign 807 patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD to receive SGLT2i and/or finerenone alone or in combination.

Although to date finerenone has been investigated in the largest study programme on non-steroidal MRA, there are other compounds that have been studied in different settings. Esaxerenone is a non-steroidal MRA that has been approved in Japan for the treatment of hypertension and DKD [134]. In the 12 week double-blind Phase III RCT ESAX-HTN, 2.5 mg esaxerenone was noninferior and 5 mg esaxerenone was superior to 50 mg eplerenone in reducing BP in 1001 Japanese patients with essential hypertension, with similar rates of adverse events across study arms [135]. In ESAX-DN, a 52 week double-blind Phase III RCT enrolling 455 patients with DKD on RAS inhibitor therapy, esaxerenone improved albuminuria vs placebo (HR for time to first remission of albuminuria: 5.13; 95% CI 3.27, 8.04) [136]. A Phase II dose-finding RCT (n=293) in DKD reported that the non-steroidal MRA apararenone yielded a dose-dependent 37–53% reduction in albuminuria, whereas the placebo arm reported a 14% increase [137].

An emerging possibility to target MR activation with a further improved safety profile may involve MR modulators that do not affect renal potassium excretion. Balcinrenone (AZD9977), an MR modulator that showed organ protection capabilities without affecting urinary sodium/potassium ratio in animal models [138], is currently being evaluated vs placebo in the Phase IIb RCT MIRACLE, enrolling 147 patients with heart failure and CKD (NCT04595370).

Aldosterone also has non-MR-mediated actions, which might not be targetable by the blockage of the MR alone [139], and therefore aldosterone synthase inhibitors might represent another therapeutic opportunity. Baxdrostat is a highly selective aldosterone synthase inhibitor that is being evaluated in resistant hypertension [140]. Although Phase II trials BrigHTN (n=248, significant BP lowering effect vs placebo) [141] and HALO (n=249, no difference in BP change vs placebo) [142] reported conflicting results, a Phase III trial is planned to start during 2023. Another aldosterone synthase inhibitor, BI 690517, is being evaluated with or without empagliflozin vs placebo for the treatment of CKD, in a Phase II RCT enrolling 714 patients (NCT05182840).

Conclusion

MR overactivation has deleterious effects on salt and fluid homeostasis, end-organ inflammation, fibrosis and metabolic dysregulation. Classical steroidal MRA have achieved tremendous success in improving outcomes in heart failure, but their adverse effect profile limits their use in clinical practice. Novel non-steroidal MRA have distinct pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties that potentially translates into favourable clinical effects and better safety profile vs steroidal MRA, and might have the potential to further target the systemic impact of MR overactivation in cardiorenal and metabolic syndromes.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- 11β-HSD2

11β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- FIDELIO-DKD

FInerenone in reducing kiDnEy faiLure and dIsease prOgression in DKD

- FIDELITY

The finerenone in CKD and type 2 diabetes: combined FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD trial programme analysis

- FIGARO-DKD

FInerenone in reducinG cArdiovascular moRtality and mOrbidity in DKD

- HFrEF

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

- HFmrEF

Heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction

- HFpEF

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- MR

Mineralocorticoid receptor

- MRA

Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

- RAS

Renin–angiotensin system

- SGLT2i

Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor

- UACR

Urinary albumin/creatinine ratio

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute.

Authors’ relationships and activities

GS reports grants and personal fees from Vifor, grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Servier, grants and personal fees from Novartis, grants and personal fees from Cytokinetics, personal fees from Medtronic, grants from Boston Scientific, grants and personal fees from Pharmacosmos, grants from Merck, grants from Bayer, personal fees from TEVA, personal fees from INTAS, personal fees from Abbott, outside the submitted work. FL declares that there are no relationships or activities that might bias, or be perceived to bias, his work. GF reports lecture fees and/or that he is a committee member of trials and registries sponsored by Amgen, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Medtronic, Novartis, Servier, Impulse Dynamics and Vifor Pharma. He has received research support from the European Union. JB reports personal fees from Abbott, American Regent, Amgen, Applied Therapeutic, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cardiac Dimension, Cardior, CVRx, Cytokinetics, Edwards, Element Science, Innolife, Impulse Dynamics, Imbria, Inventiva, Lexicon, Lilly, LivaNova, Janssen, Medtronics, Merck, Occlutech, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Pharmacosmos, Pharmain, Roche, Sequana, SQ Innovation and Vifor. SDA reports grants and personal fees from Vifor and Abbott Vascular, and personal fees for consultancies, trial committee work and/or lectures from Actimed, Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bioventrix, Brahms, Cardiac Dimensions, Cardior, Cordio, CVRx, Cytokinetics, Edwards, Farraday Pharmaceuticals, GSK, HeartKinetics, Impulse Dynamics, Novartis, Occlutech, Pfizer, Repairon, Sensible Medical, Servier, Vectorious and V-Wave. Named co-inventor of two patent applications regarding MR-proANP (DE 102007010834 & DE 102007022367), but he does not benefit personally from the related issued patents.

Contribution statement

All authors were responsible for drafting the article and reviewing it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the version to be published.

Footnotes

Gianluigi Savarese and Felix Lindberg are joint first authors

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Gianluigi Savarese, Email: gianluigi.savarese@ki.se.

Stefan D. Anker, Email: s.anker@cachexia.de

References

- 1.Shibata S, Nagase M, Yoshida S, et al. Modification of mineralocorticoid receptor function by Rac1 GTPase: implication in proteinuric kidney disease. Nat Med. 2008;14(12):1370–1376. doi: 10.1038/nm.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingelsson E, Pencina MJ, Tofler GH, et al. Multimarker approach to evaluate the incidence of the metabolic syndrome and longitudinal changes in metabolic risk factors: the Framingham Offspring Study. Circulation. 2007;116(9):984–992. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.708537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beygui F, Collet JP, Benoliel JJ, et al. High plasma aldosterone levels on admission are associated with death in patients presenting with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2006;114(24):2604–2610. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.634626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Güder G, Bauersachs J, Frantz S, et al. Complementary and incremental mortality risk prediction by cortisol and aldosterone in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2007;115(13):1754–1761. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.653964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agarwal R, Kolkhof P, Bakris G, et al. Steroidal and non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in cardiorenal medicine. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(2):152–161. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams B, MacDonald TM, Morant S, et al. Spironolactone versus placebo, bisoprolol, and doxazosin to determine the optimal treatment for drug-resistant hypertension (PATHWAY-2): a randomised, double-blind, crossover trial. Lancet. 2015;386(10008):2059–2068. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00257-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(36):3599–3726. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zannad F, McMurray JJ, Krum H, et al. Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(1):11–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, et al. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(10):709–717. doi: 10.1056/nejm199909023411001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pitt B, Remme W, Zannad F, et al. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(14):1309–1321. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solomon SD, Claggett B, Lewis EF, et al. Influence of ejection fraction on outcomes and efficacy of spironolactone in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(5):455–462. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greene SJ, Tan X, Yeh YC, et al. Factors associated with non-use and sub-target dosing of medical therapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Heart Fail Rev. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10741-021-10077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Savarese G, Carrero JJ, Pitt B, et al. Factors associated with underuse of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: an analysis of 11 215 patients from the Swedish Heart Failure Registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20(9):1326–1334. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greene SJ, Butler J, Albert NM, et al. Medical therapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the CHAMP-HF registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(4):351–366. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.04.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Group KDIGOKDW KDIGO 2022 clinical practice guideline for diabetes management in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2022;102(5S):S1–S127. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2022.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bakris GL, Agarwal R, Anker SD, et al. Effect of finerenone on chronic kidney disease outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(23):2219–2229. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2025845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pitt B, Filippatos G, Agarwal R, et al. Cardiovascular events with finerenone in kidney disease and type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(24):2252–2263. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2110956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agarwal R, Filippatos G, Pitt B, et al. Cardiovascular and kidney outcomes with finerenone in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease: the FIDELITY pooled analysis. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(6):474–484. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simpson SA, Tait JF, Wettstein A, Neher R, Von Euw J, Reichstein T. Isolation from the adrenals of a new crystalline hormone with especially high effectiveness on mineral metabolism. Experientia. 1953;9(9):333–335. doi: 10.1007/BF02155834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.August JT, Nelson DH, Thorn GW. Aldosterone. N Engl J Med. 1958;259(19):917–923. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195811062591907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sala G, Luetscher JA. The effect of sodium-retaining corticoid, electrocortin, desoxycorticosterone, and cortisone on renal function and excretion of sodium and water in adrenalectomized rats. Endocrinology. 1954;55(4):516–518. doi: 10.1210/endo-55-4-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feldman D, Funder JW, Edelman IS. Subcellular mechanisms in the action of adrenal steroids. Am J Med. 1972;53(5):545–560. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(72)90152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corvol P, Claire M, Oblin ME, Geering K, Rossier B. Mechanism of the antimineralocorticoid effects of spirolactones. Kidney Int. 1981;20(1):1–6. doi: 10.1038/ki.1981.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolkhof P, Bärfacker L. 30 years of the mineralocorticoid receptor: mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists: 60 years of research and development. J Endocrinol. 2017;234(1):T125–T140. doi: 10.1530/JOE-16-0600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arriza JL, Weinberger C, Cerelli G, et al. Cloning of human mineralocorticoid receptor complementary DNA: structural and functional kinship with the glucocorticoid receptor. Science. 1987;237(4812):268–275. doi: 10.1126/science.3037703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gomez-Sanchez E, Gomez-Sanchez CE. The multifaceted mineralocorticoid receptor. Compr Physiol. 2014;4(3):965–994. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pandey AK, Bhatt DL, Cosentino F, et al. Non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in cardiorenal disease. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(31):2931–2945. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown NJ. Contribution of aldosterone to cardiovascular and renal inflammation and fibrosis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9(8):459–469. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2013.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agarwal MK, Mirshahi M. General overview of mineralocorticoid hormone action. Pharmacol Ther. 1999;84(3):273–326. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(99)00038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fuller PJ, Yang J, Young MJ. Mechanisms of mineralocorticoid receptor signaling. Vitam Horm. 2019;109:37–68. doi: 10.1016/bs.vh.2018.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gomez-Sanchez CE, Gomez-Sanchez EP (2021) The mineralocorticoid receptor and the heart. Endocrinology 162(11). 10.1210/endocr/bqab131 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Wendler A, Baldi E, Harvey BJ, Nadal A, Norman A, Wehling M. Position paper: rapid responses to steroids: current status and future prospects. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162(5):825–830. doi: 10.1530/EJE-09-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feldman RD, Gros R. Unraveling the mechanisms underlying the rapid vascular effects of steroids: sorting out the receptors and the pathways. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163(6):1163–1169. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01366.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grossmann C, Benesic A, Krug AW, et al. Human mineralocorticoid receptor expression renders cells responsive for nongenotropic aldosterone actions. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19(7):1697–1710. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Briet M, Schiffrin EL. Aldosterone: effects on the kidney and cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2010;6(5):261–273. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2010.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Funder JW, Pearce PT, Smith R, Campbell J. Vascular type I aldosterone binding sites are physiological mineralocorticoid receptors. Endocrinology. 1989;125(4):2224–2226. doi: 10.1210/endo-125-4-2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shibata S, Nagase M, Yoshida S, Kawachi H, Fujita T. Podocyte as the target for aldosterone: roles of oxidative stress and Sgk1. Hypertension. 2007;49(2):355–364. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000255636.11931.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lother A, Moser M, Bode C, Feldman RD, Hein L. Mineralocorticoids in the heart and vasculature: new insights for old hormones. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;55:289–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010814-124302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fraccarollo D, Berger S, Galuppo P, et al. Deletion of cardiomyocyte mineralocorticoid receptor ameliorates adverse remodeling after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2011;123(4):400–408. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.983023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lother A, Berger S, Gilsbach R, et al. Ablation of mineralocorticoid receptors in myocytes but not in fibroblasts preserves cardiac function. Hypertension. 2011;57(4):746–754. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.163287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Caprio M, Newfell BG, la Sala A, et al. Functional mineralocorticoid receptors in human vascular endothelial cells regulate intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression and promote leukocyte adhesion. Circ Res. 2008;102(11):1359–1367. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.174235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lombès M, Oblin ME, Gasc JM, Baulieu EE, Farman N, Bonvalet JP. Immunohistochemical and biochemical evidence for a cardiovascular mineralocorticoid receptor. Circ Res. 1992;71(3):503–510. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.3.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Urbanet R, Nguyen Dinh Cat A, Feraco A, et al. Adipocyte mineralocorticoid receptor activation leads to metabolic syndrome and induction of prostaglandin D2 synthase. Hypertension. 2015;66(1):149–157. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marzolla V, Armani A, Feraco A, et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor in adipocytes and macrophages: a promising target to fight metabolic syndrome. Steroids. 2014;91:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gass P, Kretz O, Wolfer DP, et al. Genetic disruption of mineralocorticoid receptor leads to impaired neurogenesis and granule cell degeneration in the hippocampus of adult mice. EMBO Rep. 2000;1(5):447–451. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Odermatt A, Kratschmar DV. Tissue-specific modulation of mineralocorticoid receptor function by 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases: an overview. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;350(2):168–186. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rossier BC, Baker ME, Studer RA. Epithelial sodium transport and its control by aldosterone: the story of our internal environment revisited. Physiol Rev. 2015;95(1):297–340. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gomez-Sanchez EP, Gomez-Sanchez CE. 11β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases: a growing multi-tasking family. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2021;526:111210. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2021.111210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tesch GH, Young MJ. Mineralocorticoid receptor signaling as a therapeutic target for renal and cardiac fibrosis. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:313. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwenk MH, Hirsch JS, Bomback AS. Aldosterone blockade in CKD: emphasis on pharmacology. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2015;22(2):123–132. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blasi ER, Rocha R, Rudolph AE, Blomme EA, Polly ML, McMahon EG. Aldosterone/salt induces renal inflammation and fibrosis in hypertensive rats. Kidney Int. 2003;63(5):1791–1800. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Greene EL, Kren S, Hostetter TH. Role of aldosterone in the remnant kidney model in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1996;98(4):1063–1068. doi: 10.1172/JCI118867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Selye H. Experimental production of endomyocardial fibrosis. Lancet. 1958;1(7035):1351–1353. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(58)92163-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brilla CG, Weber KT. Mineralocorticoid excess, dietary sodium, and myocardial fibrosis. J Lab Clin Med. 1992;120(6):893–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brilla CG, Matsubara LS, Weber KT. Anti-aldosterone treatment and the prevention of myocardial fibrosis in primary and secondary hyperaldosteronism. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1993;25(5):563–575. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1993.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rickard AJ, Morgan J, Tesch G, Funder JW, Fuller PJ, Young MJ. Deletion of mineralocorticoid receptors from macrophages protects against deoxycorticosterone/salt-induced cardiac fibrosis and increased blood pressure. Hypertension. 2009;54(3):537–543. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.131110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang YL, Ma XX, Li RG, et al. T-cell mineralocorticoid receptor deficiency attenuates pathologic ventricular remodelling after myocardial infarction. Can J Cardiol. 2023;39(5):593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2023.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hirata A, Maeda N, Hiuge A, et al. Blockade of mineralocorticoid receptor reverses adipocyte dysfunction and insulin resistance in obese mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;84(1):164–172. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guo C, Ricchiuti V, Lian BQ, et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor blockade reverses obesity-related changes in expression of adiponectin, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma, and proinflammatory adipokines. Circulation. 2008;117(17):2253–2261. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.748640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Luther JM, Luo P, Kreger MT, et al. Aldosterone decreases glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in vivo in mice and in murine islets. Diabetologia. 2011;54(8):2152–2163. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2158-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Luo P, Dematteo A, Wang Z, et al. Aldosterone deficiency prevents high-fat-feeding-induced hyperglycaemia and adipocyte dysfunction in mice. Diabetologia. 2013;56(4):901–910. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2814-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Briones AM, Nguyen Dinh Cat A, Callera GE, et al. Adipocytes produce aldosterone through calcineurin-dependent signaling pathways: implications in diabetes mellitus-associated obesity and vascular dysfunction. Hypertension. 2012;59(5):1069–1078. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.190223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bruder-Nascimento T, da Silva MA, Tostes RC. The involvement of aldosterone on vascular insulin resistance: implications in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2014;6(1):90. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-6-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Catena C, Lapenna R, Baroselli S, et al. Insulin sensitivity in patients with primary aldosteronism: a follow-up study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(9):3457–3463. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Monticone S, D'Ascenzo F, Moretti C, et al. Cardiovascular events and target organ damage in primary aldosteronism compared with essential hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(1):41–50. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30319-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Colussi G, Catena C, Lapenna R, Nadalini E, Chiuch A, Sechi LA. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia are related to plasma aldosterone levels in hypertensive patients. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(9):2349–2354. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hosoya K, Minakuchi H, Wakino S, et al. Insulin resistance in chronic kidney disease is ameliorated by spironolactone in rats and humans. Kidney Int. 2015;87(4):749–760. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Freel EM, Tsorlalis IK, Lewsey JD, et al. Aldosterone status associated with insulin resistance in patients with heart failure–data from the ALOFT study. Heart. 2009;95(23):1920–1924. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.173344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Felder RB, Yu Y, Zhang ZH, Wei SG. Pharmacological treatment for heart failure: a view from the brain. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;86(2):216–220. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Koenig JB, Jaffe IZ. Direct role for smooth muscle cell mineralocorticoid receptors in vascular remodeling: novel mechanisms and clinical implications. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2014;16(5):427. doi: 10.1007/s11906-014-0427-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bioletto F, Bollati M, Lopez C, et al. Primary aldosteronism and resistant hypertension: a pathophysiological insight. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(9):4803. doi: 10.3390/ijms23094803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Harvey AP, Montezano AC, Hood KY, et al. Vascular dysfunction and fibrosis in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats: the aldosterone-mineralocorticoid receptor-Nox1 axis. Life Sci. 2017;179:110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rossier MF. The cardiac mineralocorticoid receptor (MR): a therapeutic target against ventricular arrhythmias. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021;12:694758. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.694758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hené RJ, Boer P, Koomans HA, Mees EJ. Plasma aldosterone concentrations in chronic renal disease. Kidney Int. 1982;21(1):98–101. doi: 10.1038/ki.1982.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McKelvie RS, Yusuf S, Pericak D, et al. Comparison of candesartan, enalapril, and their combination in congestive heart failure: randomized evaluation of strategies for left ventricular dysfunction (RESOLVD) pilot study. The RESOLVD Pilot Study Investigators. Circulation. 1999;100(10):1056–1064. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.10.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schjoedt KJ, Andersen S, Rossing P, Tarnow L, Parving HH. Aldosterone escape during blockade of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in diabetic nephropathy is associated with enhanced decline in glomerular filtration rate. Diabetologia. 2004;47(11):1936–1939. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1542-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cicoira M, Zanolla L, Rossi A, et al. Failure of aldosterone suppression despite angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor administration in chronic heart failure is associated with ACE DD genotype. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(7):1808–1812. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.MacFadyen RJ, Lee AF, Morton JJ, Pringle SD, Struthers AD. How often are angiotensin II and aldosterone concentrations raised during chronic ACE inhibitor treatment in cardiac failure? Heart. 1999;82(1):57–61. doi: 10.1136/hrt.82.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bomback AS, Rekhtman Y, Klemmer PJ, Canetta PA, Radhakrishnan J, Appel GB. Aldosterone breakthrough during aliskiren, valsartan, and combination (aliskiren + valsartan) therapy. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2012;6(5):338–345. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bomback AS, Klemmer PJ. The incidence and implications of aldosterone breakthrough. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2007;3(9):486–492. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bochud M, Nussberger J, Bovet P, et al. Plasma aldosterone is independently associated with the metabolic syndrome. Hypertension. 2006;48(2):239–245. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000231338.41548.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tuck ML, Sowers J, Dornfeld L, Kledzik G, Maxwell M. The effect of weight reduction on blood pressure, plasma renin activity, and plasma aldosterone levels in obese patients. N Engl J Med. 1981;304(16):930–933. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198104163041602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kagawa CM, Cella JA, Van Arman CG. Action of new steroids in blocking effects of aldosterone and desoxycorticosterone on salt. Science. 1957;126(3281):1015–1016. doi: 10.1126/science.126.3281.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liddle GW. Sodium diuresis induced by steroidal antagonists of aldosterone. Science. 1957;126(3281):1016–1018. doi: 10.1126/science.126.3281.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Garthwaite SM, McMahon EG. The evolution of aldosterone antagonists. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;217(1–2):27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Edelmann F, Wachter R, Schmidt AG, et al. Effect of spironolactone on diastolic function and exercise capacity in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the Aldo-DHF randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013;309(8):781–791. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Assmann SF, et al. Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(15):1383–1392. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1313731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rossignol P, Zannad F. Regional differences in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction trials: when nephrology meets cardiology but east does not meet west. Circulation. 2015;131(1):7–10. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.ClinicalTrials.gov (2023) Spironolactone in the treatment of heart failure. Available from https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04727073. Accessed 21 July 2023

- 90.ClinicalTrials.gov (2023) Spironolactone Initiation Registry Randomized Interventional Trial in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Available from https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02901184. Accessed 21 July 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 91.Sica DA. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of mineralocorticoid blocking agents and their effects on potassium homeostasis. Heart Fail Rev. 2005;10(1):23–29. doi: 10.1007/s10741-005-2345-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Clark E. Spironolactone therapy and gynecomastia. JAMA. 1965;193:163–164. doi: 10.1001/jama.1965.03090020077026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Seferovic PM, Pelliccia F, Zivkovic I, et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, a class beyond spironolactone–focus on the special pharmacologic properties of eplerenone. Int J Cardiol. 2015;200:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.02.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Vukadinović D, Lavall D, Vukadinović AN, Pitt B, Wagenpfeil S, Böhm M. True rate of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists-related hyperkalemia in placebo-controlled trials: a meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2017;188:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM, Lee DS, et al. Rates of hyperkalemia after publication of the Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(6):543–551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ferreira JP, Mogensen UM, Jhund PS, et al. Serum potassium in the PARADIGM-HF trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22(11):2056–2064. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Savarese G, Xu H, Trevisan M, et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcome associations of dyskalemia in heart failure with preserved, mid-range, and reduced ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2019;7(1):65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cooper LB, Benson L, Mentz RJ, et al. Association between potassium level and outcomes in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a cohort study from the Swedish Heart Failure Registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22(8):1390–1398. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Trevisan M, Fu EL, Xu Y, et al. Stopping mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists after hyperkalaemia: trial emulation in data from routine care. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23(10):1698–1707. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Butler J, Anker SD, Lund LH, et al. Patiromer for the management of hyperkalemia in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the DIAMOND trial. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(41):4362–4373. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Janse RJ, Fu EL, Dahlström U, et al. Use of guideline-recommended medical therapy in patients with heart failure and chronic kidney disease: from physician's prescriptions to patient's dispensations, medication adherence and persistence. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022;24(11):2185–2195. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Vaduganathan M, Ferreira JP, Rossignol P, et al. Effects of steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists on acute and chronic estimated glomerular filtration rate slopes in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022;24(9):1586–1590. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Savarese G, Kishi T, Vardeny O, et al. Heart failure drug treatment-inertia, titration, and discontinuation: a multinational observational study (EVOLUTION HF) JACC Heart Fail. 2023;11(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2022.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mejía-Vilet JM, Ramírez V, Cruz C, Uribe N, Gamba G, Bobadilla NA. Renal ischemia-reperfusion injury is prevented by the mineralocorticoid receptor blocker spironolactone. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293(1):F78–86. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00077.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Monrad SU, Killen PD, Anderson MR, Bradke A, Kaplan MJ. The role of aldosterone blockade in murine lupus nephritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(1):R5. doi: 10.1186/ar2353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bomback AS, Kshirsagar AV, Amamoo MA, Klemmer PJ. Change in proteinuria after adding aldosterone blockers to ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers in CKD: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51(2):199–211. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chrysostomou A, Becker G. Spironolactone in addition to ACE inhibition to reduce proteinuria in patients with chronic renal disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(12):925–926. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200109203451215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bomback AS, Kshirsagar AV, Klemmer PJ. Renal aspirin: will all patients with chronic kidney disease one day take spironolactone? Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2009;5(2):74–75. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chung EY, Ruospo M, Natale P, et al. Aldosterone antagonists in addition to renin angiotensin system antagonists for preventing the progression of chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;10(10):CD007004. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007004.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Currie G, Taylor AH, Fujita T, et al. Effect of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists on proteinuria and progression of chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2016;17(1):127. doi: 10.1186/s12882-016-0337-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hou J, Xiong W, Cao L, Wen X, Li A. Spironolactone add-on for preventing or slowing the progression of diabetic nephropathy: a meta-analysis. Clin Ther. 2015;37(9):2086–2103.e2010. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.05.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Matsumoto Y, Mori Y, Kageyama S, et al. Spironolactone reduces cardiovascular and cerebrovascular morbidity and mortality in hemodialysis patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(6):528–536. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Charytan DM, Himmelfarb J, Ikizler TA, et al. Safety and cardiovascular efficacy of spironolactone in dialysis-dependent ESRD (SPin-D): a randomized, placebo-controlled, multiple dosage trial. Kidney Int. 2019;95(4):973–982. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hammer F, Malzahn U, Donhauser J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the effect of spironolactone on left ventricular mass in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2019;95(4):983–991. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hasegawa T, Nishiwaki H, Ota E, Levack WM, Noma H. Aldosterone antagonists for people with chronic kidney disease requiring dialysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;2(2):CD013109. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013109.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bärfacker L, Kuhl A, Hillisch A, et al. Discovery of BAY 94–8862: a nonsteroidal antagonist of the mineralocorticoid receptor for the treatment of cardiorenal diseases. ChemMedChem. 2012;7(8):1385–1403. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201200081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Amazit L, Le Billan F, Kolkhof P, et al. Finerenone impedes aldosterone-dependent nuclear import of the mineralocorticoid receptor and prevents genomic recruitment of steroid receptor coactivator-1. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(36):21876–21889. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.657957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kolkhof P, Delbeck M, Kretschmer A, et al. Finerenone, a novel selective nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist protects from rat cardiorenal injury. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2014;64(1):69–78. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Snelder N, Heinig R, Drenth HJ, et al. Population pharmacokinetic and exposure-response analysis of finerenone: insights based on phase IIb data and simulations to support dose selection for pivotal trials in type 2 diabetes with chronic kidney disease. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2020;59(3):359–370. doi: 10.1007/s40262-019-00820-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Grune J, Beyhoff N, Smeir E, et al. Selective mineralocorticoid receptor cofactor modulation as molecular basis for finerenone's antifibrotic activity. Hypertension. 2018;71(4):599–608. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Barrera-Chimal J, Estrela GR, Lechner SM, et al. The myeloid mineralocorticoid receptor controls inflammatory and fibrotic responses after renal injury via macrophage interleukin-4 receptor signaling. Kidney Int. 2018;93(6):1344–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Lattenist L, Lechner SM, Messaoudi S, et al. Nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist finerenone protects against acute kidney injury-mediated chronic kidney disease: role of oxidative stress. Hypertension. 2017;69(5):870–878. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.08526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.González-Blázquez R, Somoza B, Gil-Ortega M, et al. Finerenone attenuates endothelial dysfunction and albuminuria in a chronic kidney disease model by a reduction in oxidative stress. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1131. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Marzolla V, Feraco A, Limana F, Kolkhof P, Armani A, Caprio M. Class-specific responses of brown adipose tissue to steroidal and nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022;45(1):215–220. doi: 10.1007/s40618-021-01635-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kolkhof P, Hartmann E, Freyberger A, et al. Effects of finerenone combined with empagliflozin in a model of hypertension-induced end-organ damage. Am J Nephrol. 2021;52(8):642–652. doi: 10.1159/000516213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Pitt B, Kober L, Ponikowski P, et al. Safety and tolerability of the novel non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist BAY 94–8862 in patients with chronic heart failure and mild or moderate chronic kidney disease: a randomized, double-blind trial. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(31):2453–2463. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Filippatos G, Anker SD, Böhm M, et al. A randomized controlled study of finerenone vs. eplerenone in patients with worsening chronic heart failure and diabetes mellitus and/or chronic kidney disease. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(27):2105–2114. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]