Abstract

Objective

We aimed to investigate the association between visit‐to‐visit heart rate variability (VVHRV) and all‐cause mortality in patients diagnosed with atrial fibrillation (AF). Previous studies have shown a positive correlation between VVHRV and several adverse outcomes. However, the relationship between VVHRV and the prognosis of AF remains uncertain.

Methods

In our study, we aimed to examine the relationship between VVHRV and mortality rates among 3983 participants with AF, who were part of the AFFIRM study (Atrial Fibrillation Follow‐Up Investigation of Rhythm Management). We used the standard deviation of heart rate (HRSD) to measure VVHRV and divided the patients into four groups based on quartiles of HRSD (1st, <5.69; 2nd, 5.69–8.00; 3rd, 8.01–11.01; and 4th, ≥11.02). Our primary endpoint was all‐cause death, and we estimated the hazard ratios for mortality using the Cox proportional hazard regressions.

Results

Our analysis included 3983 participants from the AFFIRM study and followed for an average of 3.5 years. During this period, 621 participants died from all causes. In multiple‐adjustment models, we found that the lowest and highest quartiles of HRSD independently predicted an increased risk of all‐cause mortality compared to the other two quartiles, presenting a U‐shaped relationship (1st vs 2nd, hazard ratio = 2.28, 95% CI = 1.63–3.20, p < .01; 1st vs. 3rd, hazard ratio = 2.23, 95% CI = 1.60–3.11, p < .01; 4th vs. 2nd, hazard ratio = 1.82, 95% CI = 1.26–2.61, p < .01; and 4th vs. 3rd, hazard ratio = 1.78, 95% CI = 1.25–2.52, p < .01).

Conclusion

In patients with AF, we found that both lower VVHRV and higher VVHRV increased the risk of all‐cause mortality, indicating a U‐shaped curve relationship.

Keywords: all‐cause mortality, atrial fibrillation, visit‐to‐visit heart rate variability

3983 participants from the AFFIRM study were followed for an average of 3.5 years, and 621 participants died from all causes. The lowest and highest quartiles of HRSD independently predicted an increased risk of all‐cause mortality compared to the other two, presenting a U‐shaped relationship.

1. INTRODUTION

Atrial fibrillation (AF), one of the most common arrhythmias, is a risk factor for several adverse cardiovascular events and carries significant morbidity and mortality, as well as a heavy economic burden. According to a recent study, approximately 37.6 million people worldwide suffered from AF or atrial flutter (Wang et al., 2021). The global prevalence of AF has increased by 33% in the last 20 years and is expected to continue rising in the next 30 years (Lippi et al., 2021). Therefore, it is vital to identify risk factors that affect the prognosis of AF. By doing so, we can implement effective measures to reduce the disability and mortality rate, prolong people's lives, and improve their quality of life.

Several studies have reported that resting heart rate (RHR) is associated with various cardiovascular outcomes (Andrade et al., 2016; Aune et al., 2017; Parikh et al., 2017; Sharashova et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2019). This phenomenon also occurs in patients with AF (Andrade et al., 2016; Iguchi et al., 2020). Additionally, visit‐to‐visit heart rate variability (VVHRV), which represents long‐term heart rate variability, has begun to gain attention as an indicator that affects adverse endpoints. There are evidences supporting VVHRV as a predictor of all‐cause mortality in heart failure (HF) (Böhm et al., 2016) and in the population free of cardiovascular disease (Wang et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2019; Zeng et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2021). However, it remains uncertain whether VVHRV affects all‐cause mortality in AF patients. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the effect of VVHRV on outcomes of patients with AF in the AFFIRM study.

2. METHODS

2.1. Data source and study population

Our data were obtained from the Atrial Fibrillation Follow‐up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) study, which was a prospective randomized trial involving 4060 patients. This is a post‐hoc analysis of the AFFIRM study. The patients were followed for an average of 3.5 years (with a minimum of 2 years) at 200 sites in the United States and Canada. The study protocol and results were previously described in detail (1997; Wyse et al., 2002). In brief, the AFFIRM study enrolled patients with AF who were at high risk for stroke and randomized treatment between heart rate (HR) control and rhythm control. Participants had clinical follow‐up visits at enrollment, 2 months, 4 months, and every 4 months thereafter. The primary endpoint was total mortality, while secondary endpoints included composite endpoints (total mortality, major bleed, stroke, disabling anoxic encephalopathy, and cardiac arrest), cost of therapy, and quality of life. Before participating in the clinical trial, all patients signed an informed consent form that had been approved by both the Clinical Trial Center and the local Institutional Review Board.

The current study has selected patients with available data on RHR at baseline and with more than five measurements during follow‐up. Patients missing baseline RHR were excluded. HR was measured by apical rate for 1 min at enrollment and at every follow‐up visit in the study.

2.2. Assessment of visit‐to‐visit heart rate variability (VVHRV)

The standard deviation of HR (HRSD) was chosen as a measure of variation, which was calculated using the following formula: , where HRi was the HR recorded at each visit and was the mean of all HR records. The VVHRV was divided into four groups based on the quartiles: the 1st quartile (<5.69), the 2nd quartile (5.69–8.00), the 3rd quartile (8.01–11.01), and the 4th quartile (≥11.02).

2.3. Outcomes

The primary outcome of this study was all‐cause death, while the secondary endpoints included other major adverse clinical outcomes: (1) cardiovascular death, (2) arrhythmia, (3) ischemic stroke, and (4) major bleed.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD and compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Categorical variables were described as counts and percentages and compared using the chi‐square (χ 2) test. The Kaplan–Meier curves were created for all‐cause mortality based on HRSD quartiles. Survival distributions were compared using the log‐rank test. A Cox regression analysis was performed to determine whether HRSD was independently associated with an increased risk of all‐cause death, with the 2nd and 3rd quartiles as the references, respectively. The analysis was adjusted for age, gender, minority, body mass index (BMI), smoking, the standard deviation of systolic blood pressure (SBP), hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease (CAD), myocardial infarction, stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA), congestive HF, cardiomyopathy, rhythm, randomized treatment group, calcium channel blockers (CCBs), and digitalis. A two‐sided p value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS v. 24.0.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Baseline characteristics of the participants

Among the 4060 participants enrolled in the original cohort, 3983 (98.1%) were available for the current study. Over an average follow‐up period of 3.5 years, the mean age was 69.5 ± 8.1 years, and 1562 (39.2%) were female. At baseline, the mean SBP was 135.4 ± 14.4 mmHg, while the mean RHR was 70.6 ± 9.2 bpm. The mean BMI was 28.9 ± 6.0 kg/m2.

Table 1 reports the baseline characteristics of the participants by HRSD quartiles. With increasing quartiles, the baseline SBP decreased significantly (p < .01), whereas the mean RHR increased progressively. The prevalence of cardiomyopathy and smoking habit exhibited a gradual increase as the quartiles progressed (both p < .01). The BMI was lower in the 1st and 3rd quartiles, with the lowest in the 1st quartile (p = .03). There is an observed rise in the number of patients with AF or flutter from the 1st quartile to the 4th quartile (p < .01). In terms of medication use, the utilization rate of digitalis increased along with the quartile levels, while the usage rate of CCBs was higher in the 3rd and 4th quartiles and β‐blockers showed no difference among quartiles. Patients in the 1st and 3rd quartiles had more coronary artery disease (p = .045), whereas no significant differences were found in gender, angina, myocardial infarction, congestive HF, congenital heart disease, valvular heart disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, stroke/TIA, peripheral arterial disease, and the use of antiarrhythmic drugs among the different quartiles.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics according to HRSD quartiles.

| Characteristics | Total | Quartiles of HRSD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st quartile (<5.69) | 2nd quartile (5.69–8.00) | 3rd quartile (8.01–11.01) | 4th quartile (≥11.02) | p Value | ||

| Participants (n) | 3983 | 997 | 991 | 1001 | 994 | – |

| Age, mean ± SD, years | 69.5 ± 8.1 | 70.3 ± 7.9 | 69.1 ± 8.3 | 69.6 ± 8.0 | 68.8 ± 8.2 | <.01 |

| Female, n (%) | 1562 (39.2) | 394 (39.5) | 374 (37.7) | 399 (39.9) | 395 (39.7) | .75 |

| Minority, n (%) | 447 (11.2) | 90 (9.0) | 117 (11.8) | 111 (11.1) | 129 (13.0) | .04 |

| Body mass index, mean ± SD, kg/m2 | 28.9 + 6.0 | 28.4 ± 5.6 | 29.2 ± 6.2 | 28.9 ± 6.1 | 29.3 ± 6.2 | .03 |

| Smoking habit, n (%) | 485 (12.2) | 104 (10.4) | 103 (10.4) | 117 (11.7) | 161 (16.2) | <.01 |

| RHR, mean ± SD, bpm | 70.6 ± 9.2 | 67.4 ± 10.1 | 69.3 ± 8.3 | 71.2 ± 8.0 | 74.7 ± 8.8 | <.01 |

| SBP, mean ± SD, mmHg | 135.4 ± 14.4 | 136.8 ± 15.7 | 135.3 ± 13.9 | 134.5 ± 14.0 | 134.9 ± 13.6 | <.01 |

| Angina, n (%) | 1029 (25.8) | 269 (27.0) | 257 (25.9) | 273 (27.3) | 230 (23.1) | .14 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 2829 (71.0) | 700 (70.2) | 709 (71.5) | 724 (72.3) | 696 (70.0) | .62 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 798 (20.0) | 191 (19.2) | 198 (20.0) | 210 (21.0) | 199 (20.0) | .79 |

| CAD, n (%) | 1520 (38.2) | 397 (39.8) | 373 (37.6) | 404 (40.4) | 346 (34.8) | .045 |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 692 (17.4) | 179 (18.0) | 181 (18.3) | 184 (18.4) | 148 (14.9) | .12 |

| Peripheral arterial disease, n (%) | 270 (6.8) | 59 (5.9) | 69 (7.0) | 76 (7.6) | 66 (6.6) | .51 |

| Stroke/TIA, n (%) | 526 (13.2) | 130 (13.0) | 125 (12.6) | 136 (13.6) | 135 (13.6) | .90 |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 912 (22.9) | 213 (21.4) | 211 (21.3) | 241 (24.1) | 247 (24.8) | .13 |

| Valvular heart disease, n (%) | 490 (12.3) | 121 (12.1) | 129 (13.0) | 130 (13.0) | 110 (11.1) | .51 |

| Cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 328 (8.2) | 60 (6.0) | 71 (7.2) | 87 (8.7) | 110 (11.1) | <.01 |

| Congenital heart disease, n (%) | 21 (0.5) | 5 (0.5) | 8 (0.8) | 4 (0.4) | 4 (0.4) | .55 |

| Pulmonary disease, n (%) | 580 (14.6) | 125 (12.5) | 151 (15.2) | 151 (15.1) | 153 (15.4) | .22 |

| Rhythm a | ||||||

| AF or atrial flutter | 1747 (45.9) | 399 (42.0) | 405 (43.2) | 471 (49.4) | 472 (49.2) | <.01 |

| Sinus (normal, bradycardia, tachycardia) | 2055 (54.1) | 552 (58.0) | 533 (56.8) | 482 (50.6) | 488 (50.8) | |

| Randomized treatment group | ||||||

| Rate control | 1989 (49.9) | 440 (44.1) | 496 (50.1) | 527 (52.6) | 526 (52.9) | <.01 |

| Rhythm control | 1994 (50.1) | 557 (55.9) | 495 (49.9) | 474 (47.7) | 468 (47.1) | |

| β‐blockers | 1702 (42.8) | 426 (42.8) | 409 (41.3) | 447 (44.7) | 420 (42.3) | .46 |

| CCBs | 1224 (30.8) | 287 (28.8) | 282 (28.5) | 306 (30.6) | 349 (35.1) | <.01 |

| Digitalis | 2110 (53.0) | 478 (48.0) | 524 (52.9) | 553 (55.3) | 555 (55.8) | <.01 |

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; CAD, coronary artery disease; CCBs, calcium channel blockers; RHR, resting heart rate; SBP, systolic blood pressure at baseline; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Rhythm at time of randomization.

3.2. Survival analysis

During a mean follow‐up of 3.5 years, 621 (15.6%) patients died of all causes, and 272 (6.8%) experienced cardiovascular deaths. The mortality rates for HRSD from the first quartile through the fourth quartile were 21.7%, 12.6%, 12.6%, and 15.5%, respectively. There were 133 (3.3%) strokes, 229 (5.7%) major bleeds, and 37 (0.9%) cases of arrhythmia.

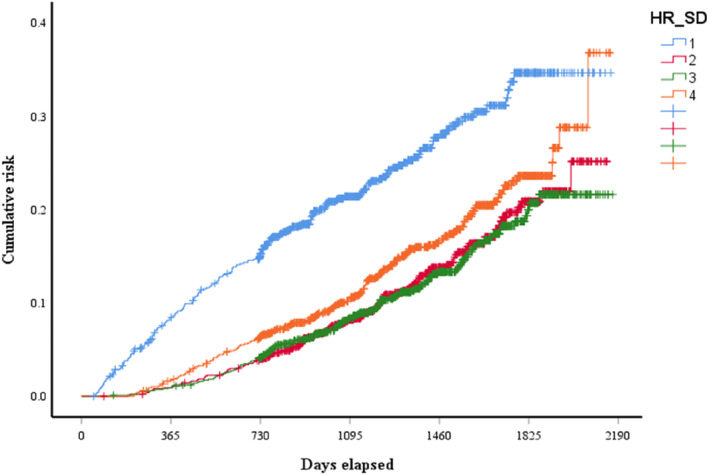

According to Table 2, rates of all‐cause mortality showed a U‐shaped curve from the 1st quartile to the 4th quartile (p < .01), with the highest rate in the 1st quartile and the second‐highest rate in the 4th quartile. As for clinical outcomes other than all‐cause mortality, no significant differences were observed among the four quartiles. Cumulative incidence of all‐cause mortality presents a U‐shaped association across quartiles of HRSD (Figure 1, log‐rank test: χ 2 = 75.51, p < .001). Lower and higher quartiles of HRSD were related to a higher risk of total mortality during follow‐up.

TABLE 2.

Major adverse clinical outcomes according to HRSD quartiles.

| Outcomes | Total | 1st Quartile (<5.69) | 2nd Quartile (5.69–8.00) | 3rd Quartile (8.01–11.01) | 4th Quartile (≥11.02) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants (n) | 3983 | 997 | 991 | 1001 | 994 | – |

| All‐cause death, n (%) | 621 (15.6) | 216 (21.7) | 125 (12.6) | 126 (12.6) | 154 (15.5) | <.01 |

| Cardiovascular death, n (%) | 272 (6.8) | 59 (59.2) | 70 (70.6) | 73 (72.9) | 70 (70.4) | .48 |

| Arrhythmia, n (%) | 37 (0.9) | 8 (0.8) | 10 (1) | 12 (1.2) | 7 (0.7) | .44 |

| Ischemic stroke, n (%) | 133 (3.3) | 29 (2.9) | 27 (2.7) | 41 (4.1) | 36 (3.6) | .42 |

| Major bleed, n (%) | 229 (5.7) | 47 (4.7) | 60 (6.1) | 59 (5.9) | 63 (6.3) | .15 |

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of the overall cumulative risk based on HRSD (log‐rank test, χ 2 = 75.51, p < .001). Blue line: 1st quartile; red line: 2nd quartile; green line: 3rd quartile; and orange line: 4th quartile.

3.3. Multivariate analyses

In the Cox multivariate regression analysis for all‐cause death (Table 3), it was observed that the 1st and 4th quartiles of HRSD were associated with a higher all‐cause mortality rate compared to the other two quartiles. Compared with the 2nd quartile, after adjustment for confounders, the hazard ratios for all‐cause death in the lowest and highest quartiles of HRSD were, respectively, 2.28 (95% CI = 1.63–3.20, p < .01) and 1.82 (95% CI = 1.26–2.61, p < .01. While regarded the 3rd quartile as reference, the hazard ratios in the 1st and 4th quartiles were 2.23 (95% CI = 1.60–3.11, p < .01) and 1.78 (95% CI = 1.25–2.52, p < .01), respectively. Interestingly, the 1st quartile of HRSD predicted a higher mortality rate than the 4th quartile, but this difference was not statistically significant. The analysis was adjusted for age, gender, minority, BMI, smoking, the standard deviation of SBP, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, CAD, myocardial infarction, stroke/TIA, congestive HF, cardiomyopathy, rhythm, randomized treatment group, CCBs, and digitalis.

TABLE 3.

Cox regression analysis for all‐cause death.

| HRSD quartiles | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p Value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted model | ||||

| 1st quartile | 2.15 (1.73–2.68) | <.01 | 2.21 (1.78–2.76) | <.01 |

| 2nd quartile | 1.00 | – | 1.03 (0.80–1.32) | .83 |

| 3rd quartile | 0.97 (0.76–1.25) | .83 | 1.00 | – |

| 4th quartile | 1.24 (0.98–1.57) | .08 | 1.27 (1.00–1.61) | .046 |

| Adjusted model a | ||||

| 1st quartile | 2.28 (1.63–3.20) | <.01 | 2.23 (1.60–3.11) | <.01 |

| 2nd quartile | 1.00 | – | 0.98 (0.66–1.45) | .91 |

| 3rd quartile | 1.02 (0.69–1.52) | .91 | 1.00 | – |

| 4th quartile | 1.82 (1.26–2.61) | <.01 | 1.78 (1.25–2.52) | <.01 |

The analysis was adjusted for age, gender, minority, body mass index, smoking, the standard deviation of systolic blood pressure, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, CAD, myocardial infarction, stroke/TIA, congestive heart failure, cardiomyopathy, rhythm, randomized treatment group, CCBs, and digitalis.

4. DISCUSSION

The present study concluded that both lower variability and higher variability in visit‐to‐visit heart rate increased the risk of all‐cause death, which showed a U‐shaped curve, independent of age, gender, minority, BMI, smoking, the standard deviation of SBP, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, CAD, myocardial infarction, stroke/TIA, congestive HF, cardiomyopathy, rhythm, randomized treatment group, CCBs, and digitalis. The U‐shaped curve relationship suggests that there may be an optimal range of VVHRV associated with better outcomes. Patients in the lowest and highest quartiles of HRSD had higher risk of all‐cause death than the other two quartiles.

It has been widely confirmed that an elevated RHR is associated with various adverse prognoses in the general population or hypertensive patients, including AF, HF, cardiovascular mortality, and all‐cause mortality (Aune et al., 2017; Habibi et al., 2019; Hozawa et al., 2004; Jensen et al., 2013; Sharashova et al., 2016; Sobieraj et al., 2021). However, the impact of HR on the prognosis in patients with AF was inconsistent in existing studies. Some studies showed that the RHR had no effect on outcomes in sustained AF (Andrade et al., 2016; Böhm et al., 2022; Moschovitis et al., 2021). In a multicenter AF cohort study of Japan, a high HR was related to adverse outcomes in persistent AF, but not in paroxysmal AF patients (Iguchi et al., 2020), whereas another sub‐analysis of an observational study in Japan supports the positive association of HR end with adverse events in non‐valvular AF, regardless of paroxysmal or persistent AF (Kodani et al., 2022). Since the previous study solely focused on HR collected from a single visit, such as enrollment or end of follow‐up, this study has included HR at multiple follow‐up visits and analyzed the impact of follow‐up heart rate variability (HRV) on prognosis. The influence of long‐term HRV, which refers to variation over months or years, on the prognosis of patients with AF is rarely reported. Prior investigations have shown that VVHRV is linked to various adverse cardiovascular events (Zeng et al., 2022), including new‐onset AF (Zhang et al., 2021). The analysis (Zhang et al., 2021) based on data from the Kailuan study cohort suggested that both higher and lower VVHRV levels might elevate the risk of new‐onset AF. This conclusion is similar to our study, which found a U‐shaped relationship between VVHRV and all‐cause mortality. Another recent study (Krittayaphong et al., 2023), conducted with data from multiple centers in Thailand, revealed that VVHRV is an independent predictor of poor prognosis in patients with AF. VVHRV exhibits a J‐curve effect on all‐cause mortality in that study. The conclusion of our study is in line with the aforementioned study regarding all‐cause mortality. The reasons for two studies from different countries and different time periods reaching similar conclusions include the following: Both studies utilized data from multicenter prospective studies, with similar sample sizes, follow‐up periods, and frequencies.

Nevertheless, previous studies have consistently confirmed that increased VVHRV is positively related to all‐cause mortality, which differs from the findings of our study (Floyd et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2019; Zeng et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2021). It is important to note that the populations in these studies varied. Floyd et al (2015) indicated that greater variation in RHR over 4 years predicted a higher risk of death among older persons without known cardiovascular diseases. The other three analyses, all derived from the Kailuan study, drew similar conclusions in the general population free of cardiovascular disease (Wang et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2019) and in hypertensive patients (Zhao et al., 2021), respectively.

Conversely, Böhm's findings from the Systolic Heart Failure Treatment with the If Inhibitor Ivabradine Trial (SHIFT) partially support our analysis that low VVHRV predicts an increased risk of death from any cause in patients with systolic HF (Böhm et al., 2016).

We have identified several reasons for the conflicting outcomes of these studies. First, different study populations may be a significant reason for the opposite conclusions drawn in the studies mentioned above. Studies that demonstrate a positive association between VVHRV and outcomes mostly come from the Kailuan study, which included patients with hypertension or the general population without cardiovascular disease. Conversely, the current study and the one that showed a converse effect focused on AF and HF patients, respectively. Second, there are differences in geography and sample size among the studies. The AFFIRM and SHIFT studies are multi‐country studies with relatively small sample sizes, while the Kailuan study is regional, conducted in Tangshan city in Northern China, but with a significantly larger sample size. Third, we collected HR data at enrollment and every four‐month visit, which was much more frequent than other studies. Adequate follow‐up data lead to a more accurate and convincing assessment of VVHRV.

The etiological mechanisms underlying the impact of long‐term HRV on prognosis in patients with AF remain unclear. Khan AA et al. demonstrated that patients with AF had higher HRV (Khan et al., 2021). The autonomic nervous system (ANS) plays a crucial role in the development, maintenance, and progression of AF (Khan et al., 2019). Conventional HRV evaluates beat‐to‐beat variation of the heart and represents a balance between the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) (Shaffer & Ginsberg, 2017). As a noninvasive method and an ideal index to assess ANS activity, HRV can reflect the influence of ANS on HR (1996; Sredniawa et al., 1999; Sztajzel, 2004). Although it is currently unclear whether there is an association between long‐term HRV over several years and short‐term HRV, we hypothesize that abnormally high or low long‐term HRV indicates impaired neurocardiac functions related to imbalance of the ANS, which could ultimately lead to an increased risk of adverse events. Results from one previous research (Zhang et al., 2021) indicated that activation of SNS might contribute to the level of VVHRV, ultimately leading to a higher incidence of AF. The U‐shaped relationship observed in our study may share similar mechanisms.

Overall, these findings suggest that VVHRV may be a useful predictor of all‐cause mortality and that controlling VVHRV within a certain range may improve prognosis in patients with AF. However, further studies are needed to confirm these results and determine the optimal range for VVHRV control.

5. CONCLUSION

In this post‐hoc analysis from the AFFIRM study, it was found that lower VVHRV and higher VVHRV independently increased the risk of all‐cause mortality in patients with AF, demonstrating a U‐curve appearance.

6. LIMITATIONS

There are several limitations in our study. First, we used only one indicator to represent VVHRV, which may lead to less comprehensive results. Second, as the study investigators acknowledge that measurement of the duration of AF is difficult, at times impossible, we failed to account for differences in paroxysmal and permanent AF. Third, it did not mention if HR was measured at the same time of the day during every visit. Moreover, there may still be some unadjusted confounding factors affecting VVHRV. Fourth, data from patients managed decades ago may lead to results that fail to extrapolate to the current population.

7. PERSPECTIVES

To the best of our knowledge, this analysis is one of the few studies that explore the relationship between VVHRV and overall mortality in AF patients, which concluded that VVHRV may be predictive of all‐cause mortality. There are few reports on the factors influencing VVHRV and the mechanism by which it impacts the prognosis of AF patients. Further observations involving a larger sample size, multiple countries, and ethnicities are warranted to ascertain the findings and establish a mechanism theory. Also, it is necessary to explore treatment strategies aimed at improving VVHRV to mitigate the risk of adverse outcomes. These will provide a foundation for seeking new therapeutic interventions to address this issue and improve the prognosis of AF patients.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. All authors state their consent to publish.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all study participants and the members of the survey teams from the AFFIRM study for their contribution. There was no funding support.

Zhou, X. , Yuan, Q. , Yuan, J. , Du, Z.‐M. , Zhuang, X. , & Liao, X. (2024). The impact of visit‐to‐visit heart rate variability on all‐cause mortality in atrial fibrillation. Annals of Noninvasive Electrocardiology, 29, e13094. 10.1111/anec.13094

Xiaoyan Zhou and Qinghua Yuan contributed equally to this work and shared the position of the first author.

Xiaodong Zhuang and Xinxue Liao contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Xiaodong Zhuang, Email: zhuangxd3@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Xinxue Liao, Email: liaoxinx@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- (1997). Atrial fibrillation follow‐up investigation of rhythm management – The AFFIRM study design. The Planning and Steering Committees of the AFFIRM study for the NHLBI AFFIRM investigators. The American Journal of Cardiology, 79(9), 1198–1202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (1996). Heart rate variability: Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. European Heart Journal, 17(3), 354–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, J. G. , Roy, D. , Wyse, D. G. , Tardif, J. C. , Talajic, M. , Leduc, H. , Tourigny, J. C. , Shohoudi, A. , Dubuc, M. , Rivard, L. , Guerra, P. G. , Thibault, B. , Dyrda, K. , Macle, L. , & Khairy, P. (2016). Heart rate and adverse outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation: A combined AFFIRM and AF‐CHF substudy. Heart Rhythm, 13(1), 54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aune, D. , Sen, A. , ó'Hartaigh, B. , Janszky, I. , Romundstad, P. R. , Tonstad, S. , & Vatten, L. J. (2017). Resting heart rate and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer, and all‐cause mortality – A systematic review and dose‐response meta‐analysis of prospective studies. Nutrition, Metabolism, and Cardiovascular Diseases, 27(6), 504–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhm, M. , Butler, J. , Mahfoud, F. , Filippatos, G. , Ferreira, J. P. , Pocock, S. J. , Slawik, J. , Brueckmann, M. , Linetzky, B. , Schüler, E. , Wanner, C. , Zannad, F. , Packer, M. , Anker, S. D. , & EMPEROR‐Preserved Trial Committees and Investigators . (2022). Heart failure outcomes according to heart rate and effects of empagliflozin in patients of the EMPEROR‐Preserved trial. European Journal of Heart Failure, 24(10), 1883–1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhm, M. , Robertson, M. , Borer, J. , Ford, I. , Komajda, M. , Mahfoud, F. , Ewen, S. , Swedberg, K. , & Tavazzi, L. (2016). Effect of visit‐to‐visit variation of heart rate and systolic blood pressure on outcomes in chronic systolic heart failure: Results from the systolic heart failure treatment with the If inhibitor Ivabradine trial (SHIFT) trial. Journal of the American Heart Association, 5(2), e002160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd, J. S. , Sitlani, C. M. , Wiggins, K. L. , Wallace, E. , Suchy‐Dicey, A. , Abbasi, S. A. , Carnethon, M. R. , Siscovick, D. S. , Sotoodehnia, N. , Heckbert, S. R. , McKnight, B. , Rice, K. M. , & Psaty, B. M. (2015). Variation in resting heart rate over 4 years and the risks of myocardial infarction and death among older adults. Heart, 101(2), 132–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habibi, M. , Chahal, H. , Greenland, P. , Guallar, E. , Lima, J. A. C. , Soliman, E. Z. , Alonso, A. , Heckbert, S. R. , & Nazarian, S. (2019). Resting heart rate, short‐term heart rate variability and incident atrial fibrillation (from the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA)). The American Journal of Cardiology, 124(11), 1684–1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hozawa, A. , Ohkubo, T. , Kikuya, M. , Ugajin, T. , Yamaguchi, J. , Asayama, K. , Metoki, H. , Ohmori, K. , Hoshi, H. , Hashimoto, J. , Satoh, H. , Tsuji, I. , & Imai, Y. (2004). Prognostic value of home heart rate for cardiovascular mortality in the general population: The Ohasama study. American Journal of Hypertension, 17(11 Pt 1), 1005–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iguchi, M. , Hamatani, Y. , Sugiyama, H. , Ishigami, K. , Aono, Y. , Ikeda, S. , Doi, K. , Fujino, A. , An, Y. , Ishii, M. , Masunaga, N. , Esato, M. , Tsuji, H. , Wada, H. , Hasegawa, K. , Ogawa, H. , Abe, M. , Akao, M. , & Fushimi AF Registry Investigators . (2020). Different impact of resting heart rate on adverse events in paroxysmal and sustained atrial fibrillation – The Fushimi AF Registry. Circulation Journal, 84(12), 2138–2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, M. T. , Suadicani, P. , Hein, H. O. , & Gyntelberg, F. (2013). Elevated resting heart rate, physical fitness and all‐cause mortality: A 16‐year follow‐up in the Copenhagen male study. Heart, 99(12), 882–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A. A. , Junejo, R. T. , Thomas, G. N. , Fisher, J. P. , & Lip, G. Y. H. (2021). Heart rate variability in patients with atrial fibrillation and hypertension. European Journal of Clinical Investigation, 51(1), e13361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A. A. , Lip, G. Y. H. , & Shantsila, A. (2019). Heart rate variability in atrial fibrillation: The balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system. European Journal of Clinical Investigation, 49(11), e13174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodani, E. , Inoue, H. , Atarashi, H. , Okumura, K. , Yamashita, T. , Origasa, H. , & J‐RHYTHM Registry Investigators . (2022). Impact of heart rate on adverse events in patients with non‐valvular atrial fibrillation: Subanalysis of the J‐RHYTHM Registry. International Journal of Cardiology. Heart & Vasculature, 43, 101148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krittayaphong, R. , Boonyapisit, W. , Sairat, P. , & Lip, G. Y. H. (2023). Visit‐to‐visit heart rate variability in the prediction of clinical outcomes of patients with atrial fibrillation. Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 123(9), 920–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippi, G. , Sanchis‐Gomar, F. , & Cervellin, G. (2021). Global epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: An increasing epidemic and public health challenge. International Journal of Stroke, 16(2), 217–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moschovitis, G. , Johnson, L. S. B. , Blum, S. , Aeschbacher, S. , De Perna, M. L. , Pagnamenta, A. , Mayer Melchiorre, P. A. , Benz, A. P. , Kobza, R. , Di Valentino, M. , Zuern, C. S. , Auricchio, A. , Conte, G. , Rodondi, N. , Blum, M. R. , Beer, J. H. , Kühne, M. , Osswald, S. , Conen, D. , & BEAT‐AF and Swiss‐AF Investigators . (2021). Heart rate and adverse outcomes in patients with prevalent atrial fibrillation. Open Heart, 8(1), e001606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh, K. S. , Greiner, M. A. , Suzuki, T. , DeVore, A. D. , Blackshear, C. , Maher, J. F. , Curtis, L. H. , Hernandez, A. F. , O'Brien, E. C. , & Mentz, R. J. (2017). Resting heart rate and long‐term outcomes among the African American population: Insights from the Jackson Heart Study. JAMA Cardiology, 2(2), 172–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer, F. , & Ginsberg, J. P. (2017). An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Frontiers in Public Health, 5, 258–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharashova, E. , Wilsgaard, T. , Mathiesen, E. B. , Løchen, M. L. , Njølstad, I. , & Brenn, T. (2016). Resting heart rate predicts incident myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, ischaemic stroke and death in the general population: The Tromsø Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 70(9), 902–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobieraj, P. , Siński, M. , & Lewandowski, J. (2021). Resting heart rate and cardiovascular outcomes during intensive and standard blood pressure reduction: An analysis from SPRINT trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(15), 3264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sredniawa, B. , Musialik‐Lydka, A. , Herdyńska‐Was, M. , & Pasyk, S. (1999). Metody oceny i znaczenie kliniczne zmienności rytmu zatokowego [The assessment and clinical significance of heart rate variability]. Polski Merkuriusz Lekarski, 7(42), 283–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sztajzel, J. (2004). Heart rate variability: A noninvasive electrocardiographic method to measure the autonomic nervous system. Swiss Medical Weekly, 134(35–36), 514–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B. , Li, H. , Han, X. , Yang, Y. , Chen, Y. , Li, W. , Yang, X. , Xing, A. , Wang, Y. , Hidru, T. H. , Wu, S. , & Xia, Y. (2017). Elevated long term resting heart rate variation is associated with increased risk of all‐cause mortality in northern China. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 8043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. , Ze, F. , Li, J. , Mi, L. , Han, B. , Niu, H. , & Zhao, N. (2021). Trends of global burden of atrial fibrillation/flutter from Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Heart, 107(11), 881–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. , Fashanu, O. E. , Zhao, D. , Guallar, E. , Gottesman, R. F. , Schneider, A. L. C. , McEvoy, J. W. , Norby, F. L. , Aladin, A. I. , Alonso, A. , & Michos, E. D. (2019). Relation of elevated resting heart rate in mid‐life to cognitive decline over 20 years (from the atherosclerosis risk in communities [ARIC] study). The American Journal of Cardiology, 123(2), 334–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyse, D. G. , Waldo, A. L. , DiMarco, J. P. , Domanski, M. J. , Rosenberg, Y. , Schron, E. B. , Kellen, J. C. , Greene, H. L. , Mickel, M. C. , Dalquist, J. E. , Corley, S. D. , & Atrial Fibrillation Follow‐up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) Investigators . (2002). A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. The New England Journal of Medicine, 347(23), 1825–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X. , Hidru, T. H. , Wang, B. , Han, X. , Li, H. , Wu, S. , & Xia, Y. (2019). The link between elevated long‐term resting heart rate and SBP variability for all‐cause mortality. Journal of Hypertension, 37(1), 84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, R. , Wang, Z. , Cheng, W. , & Yang, K. (2022). Visit‐to‐visit heart rate variability is positively associated with the risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 9, 850223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. , Zhao, M. , Sun, Y. , Hou, Z. , Wang, C. , Yun, C. , Li, Y. , Li, Z. , Wang, M. , Wu, S. , & Xue, H. (2021). Frequency of visit‐to‐visit variability of resting heart rate and the risk of new‐onset atrial fibrillation in the general population. The American Journal of Cardiology, 155, 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M. , Yao, S. , Li, Y. , Wang, M. , Wang, C. , Yun, C. , Zhang, S. , Sun, Y. , Hou, Z. , Wu, S. , & Xue, H. (2021). Combined effect of visit‐to‐visit variations in heart rate and systolic blood pressure on all‐cause mortality in hypertensive patients. Hypertension Research, 44(10), 1291–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.