Abstract

Introduction:

Interpersonal support can promote positive outcomes among people living with HIV. In order to develop an acceptable psychoeducational couples-based intervention aimed at strengthening the relationship context and improving HIV outcomes before and after pregnancy, we conducted qualitative interviews with pregnant women living with HIV and their male partners.

Methods:

We interviewed a convenience clinic-based sample of pregnant women living with HIV (n = 30) and male partners (n = 18) in Lusaka, Zambia. Interviews included pile sorting relationship topics in order of perceived priority. Interviews also focused on family health concerns. Interviews were audio-recorded, translated, transcribed, and thematically analyzed. Pile sorting data was analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results:

All female participants were living with HIV; 61% of the male partners interviewed were additionally living with HIV. The most prioritized relationship topic among both genders was communication between couples. Honesty and respect were important relationship topics but prioritized differently based on gender. Female participants considered emotional and instrumental support from male partners critical for their physical and mental health; men did not prioritize support. Intimate partner violence was discussed often by both genders. Family health priorities included good nutrition during pregnancy, preventing infant HIV infection, safe infant feeding, sexual health, and men’s alcohol use.

Conclusions:

A major contribution of this study is a better understanding of the dyad-level factors pregnant women living with HIV and their male partners perceive to be the most important for a healthy, well-functioning relationship. This study additionally identified gaps in antenatal health education and the specific family health issues most prioritized by pregnant women living with HIV and their male partners. The findings of this study will inform the development of an acceptable couples-based intervention with greater likelihood of efficacy in strengthening the relationship context and promoting family health during and after pregnancies that are affected by HIV.

Keywords: HIV, Couples, Heterosexual relationships, Social support, Intervention development, Pregnancy, Prevention of mother-to-child transmission, Relationship dynamics, Marriage

1. Introduction

In southern Africa, the region most affected by HIV globally, commendable achievements have been made in the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT). In high HIV prevalence settings, such as Zambia, almost all pregnant women receive HIV mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT). In high HIV prevalence settings, such as Zambia, almost all pregnant women receive HIV testing during antenatal care (ANC) and have access to lifelong antiretroviral therapy (ART) through integrated HIV-ANC programs (Zambia Statistics Agency, 2019). Yet, HIV continues to be associated with significant morbidity and mortality for both women living with HIV (WLWH) and their children – much of which is attributable to poor retention in HIV care and suboptimal adherence to ART (WHO, 2016; amFAR, 2016; UNAIDS, 2019). In Zambia, more than 90% of pregnant women receive HIV testing during ANC (UNICEF, 2017), but after HIV testing, pregnant WLWH drop-off the additional steps in the PMTCT continuum of care at unacceptably high rates (Okawa et al., 2015; Hampanda, 2016).

To promote PMTCT, the World Health Organization (WHO) has called for a renewed emphasis on couples (WHO, 2012). Couple-based approaches to PMTCT may be particularly effective since couple relationship dynamics can influence HIV-related stigma (Abbamonte et al., 2020) and engagement with HIV testing, care, and treatment for both partners as well as infants (Wamoyi et al., 2017; Hampanda, 2016; Hatcher et al., 2014, Hatcher et al., 2016). For instance, couple HIV testing and counseling (CHTC) is a widely utilized approach that improves uptake of HIV testing and mutual status disclosure in heterosexual relationships across various African settings (Turan et al., 2018; Darbes et al., 2014; Becker et al., 2014; Pettifor et al., 2014). Moreover, relationship education through couple-counseling approaches has been shown to improve healthy relationship skills like communication within couples (Schofield et al., 2012), leading to improved sexual and reproductive health outcomes (Bradley et al., 2011; Bodenmann and Shantinath, 2004; Tilahun et al., 2015). In South Africa, improved communication and problem-solving skills in couples resulted in more effective engagement in HIV prevention behaviors (i.e., condom use) (Pettifor et al., 2014). Recently, two trials from sub-Saharan Africa have additionally shown that couple-based interventions targeting HIV health education alongside relationship skills can enhance the uptake of CHTC both outside the context of pregnancy (Darbes et al., 2019) and during pregnancy (Turan et al., 2018).

Although we know that relationship dynamics within heterosexual couples impact successful engagement with PTMCT (Bell and Naugle, 2008; Hatcher et al., 2014, 2015, 2016; Hampanda, 2016; Hampanda et al., 2017), there are few couples-oriented HIV interventions focused on the relationship context around the time of pregnancy in low-resource, high HIV-prevalence settings (Turan et al., 2018; Sifunda et al., 2019; Weiss et al., 2014). Most prior HIV interventions for pregnant couples have focused either on offering health services to couples, such as HIV testing (Ditekemena et al., 2011; Ezeanolue et al., 2015; Krakowiak et al., 2016; Osoti et al., 2014), or using recruitment strategies to get male partners to attend ANC (Byamugisha et al., 2011; Mohlala et al., 2011; Nyondo et al., 2015; Rosenberg et al., 2015; Theuring et al., 2016).

Targeting the relationship context of pregnant couples affected by HIV could be especially important given that pregnancy can exert significant influence on relationship dynamics, improving harmony for some, but increasing tension and conflict among others (Rogers et al., 2016). As formative work to develop an acceptable couple-based relationship strengthening and PMTCT-promoting intervention, we conducted interviews with pregnant WLWH and their male partners in the target community in Zambia. This article presents qualitative themes of both pregnant WLWH and their male partners highlighting their needs and priorities regarding health information and relationship skills.

1.1. Theoretical framework

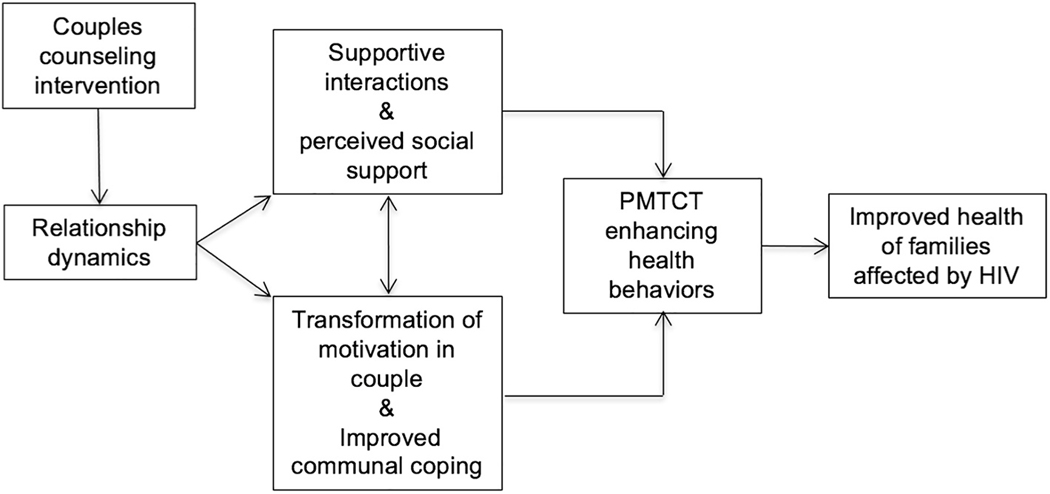

The conceptual framework for this research (see Fig. 1) is based on two complementary theories: (1) The Interdependence Model of Couples Communal Coping (Lewis et al., 2006) and (2) the relationship context of social support (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). The Interdependence Model of Couples Communal Coping indicates that partners within a couple influence one another’s health behaviors and that by influencing the couple as a unit, interventions can make a sustained positive impact on behavior change (Lewis et al., 2006). The model hypothesizes that the initiation and maintenance of health-enhancing behaviors within couples are the end result of positive relationship dynamics, which are essential for a behavioral “transformation of motivation” (Darbes et al., 2014). This transformation occurs when partners shift their perception from being individually centered to being more relationship-oriented. Once this shift occurs, the couple can engage in “communal coping,” a process of joint communication, decision-making, and problem-solving to address a particular health issue (Lewis et al., 2006; Rogers et al., 2016).

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model.

The second informative framework, the relationship process perspective of social support, adds to the interdependence model by highlighting the role of supportive actions of others, such as advice and reassurance, and an individual’s perception of social support, which can improve health behaviors and outcomes (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). Within relationships, several dimensions are particularly influential on the level of perceived social support: partner responsiveness (intimacy, trust, acceptance), couples interdependence (joint decision-making and negotiation), and sentiment (relationship satisfaction and conflict) (Reis and Collins, 2000).

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This qualitative study was the first phase of a two-phase sequential mixed-methods study (K99MH116735/R00MH116735). The findings reported in this article are from the primary analysis of the first phase of the research and included 48 semi-structured interviews with a convenience clinic-based sample of pregnant WLWH (n = 30) and their male partners (n = 18) in Lusaka, Zambia.

2.2. Sampling and participants

Sampling took place at a large district hospital in the capital city of Lusaka, Zambia, which has a high HIV prevalence among pregnant women attending ANC (CSO, 2014). We recruited a convenience sample of pregnant WLWH and their male partners. During ANC, nurses recruited pregnant WLWH to participate in a one-on-one qualitative interview with a gender-matched local researcher at the health facility that day or at a later date/place of the woman’s choosing. Pregnant WLWH were eligible if they reported being married or living with a male partner. At the end of the interviews, female participants were asked for consent to contact the male partner regarding a similar interview on “topics pertaining to family health, including HIV.” Consenting women provided the contact details for their male partners who were later contacted by a local researcher using a standardized recruitment script and invited to participate in an interview at a convenient date/place of his choosing with a gender-matched research assistant. Women’s HIV status was not conveyed during recruitment or in the interview with male partners. All participants were compensated with a small travel reimbursement (52 ZMW/5 USD).

2.3. Ethical considerations

All participants provided written informed consent. The study procedures were approved by relevent institutional review boards in the United States (The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board) and Zambia (The University of Zambia Biomedical Research Ethics Committee). Referrals to local health and social services were offered to any participants reporting abuse or mental health concerns during the interviews based on a standard operating procedure (SOP). All study staff were trained in using the SOP, recognizing distress, and providing referrals.

2.4. Data collection and analysis

The preliminary interview guide was developed by the first author based on existing literature in the field (Rogers et al., 2016; Burton et al., 2010) and the research team’s previous work (Spangler et al., 2018; Hampanda et al., 2019; Hampanda, 2016). The guide was reviewed by an expert panel, including local Zambian research collaborators, and revised. The final interview guide was translated into the local languages (Nyanja and Bemba) and back translated into English to ensure accuracy. Trained gender-matched Zambian researchers conducted the individual interviews with each participant in the local languages using the semi-structured interview guide. The interview guide included broad, open-ended questions related to content acceptability of a couple counseling intervention for pregnant couples, including priority relationship topics and family health concerns (see Table 1). The interviews were conducted in a private room at the health facility or in another private location of the participant’s choosing at a later time. Interviews lasted between 20 and 60 min. The research team meet weekly to discuss observations and experiences from the interviews and identify additional probes or follow-up questions to be included in the next round of interviews, as well as to determine when theoretical saturation had been achieved (Green and Thorogood, 2014).

Table 1.

Interview topics with pregnant women living with HIV and their male partners.

| Theme | Topics |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Relationship priorities | ∘ perceptions of most important relationship skills in a couples counseling intervention ∘ views on the relative importance of communication, support, conflict negotiation, decision-making, honesty, and respect ∘ other relationship priorities |

| Family health priorities | ∘ Most pressing family health concerns ∘ types of health information that should be provided during counseling visits ∘ barriers to optimal family health during and after pregnancy |

Interviews were digitally recorded, with informed consent of the participants, and translated and transcribed verbatim into English. Transcripts were analyzed in Atlas.ti by three of the authors (KH, TFLM, SN) using a thematic constant comparison approach. Ten percent of the transcripts were independently coded by three of the authors and compared to establish inter-coder reliability. Discrepancies in coding were discussed until >95% consensus was achieved. Our approach consisted of both deductive (a priori) codes from the interview guide and research protocol, as well as inductive (emergent) codes. Line-by-line coding identified meanings and assumptions within the transcripts, followed by constant comparison between codes and interviews, and finally, focused coding to compare relationships between categories and themes and to identify theoretical concepts related to relationship and health priorities (Charmaz, 2014; Green and Thorogood, 2014). Direct quotations are used to support themes and to demonstrate confirmability (Drisko, 1997).

As a component of the interviews, each participant also completed a pile sorting activity, a cognitive mapping methodology used across social science disciplines to empirically assess how people cognitively organize information within cultural domains (Pelto, 2013). Participants were asked to physically arrange pieces of paper with six relationship topics listed (communication, support, conflict resolution, honesty, respect, and decision-making) in order of their perceived level of priority and to explain their ordering rationale. If the participant was unable to read, the interviewer verbally assisted with this activity, reading the options to the participant and asking them the order they would prioritize. Relationship topics included in the pile sorting activity were based on the relationship process of social support (Reis and Collins, 2000). Following pile sorting, each participant discussed why they sorted the topics in this manner and other potential relationship skills they would prioritize. Pile sorting data were collected and analyzed in Microsoft Excel using descriptive statistics to support the qualitative themes from the transcripts.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

Table 2 displays the characteristics of the interview participants, including pregnant women (n = 30) and their male partners (n =18). All (100%) of the women we interviewed were living with HIV. Sixty-one percent of the male partners we interviewed were also living with HIV (i.e., sero-concordant) while 39% were HIV-negative (i.e., sero-discordant). The sample was diverse in terms of age, education, and literacy. Men were slightly older, had received more education, and were much more likely to report literacy. Men were also slightly more likely to report HIV status disclosure to their partner than the female participants (100% and 90%, respectively).

Table 2.

Sample characteristics of interview participants.

| Total (n = 48) | Female (n = 30) | Male (n = 18) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Socio-demographics: | |||

| Age: mean (sd) | 34.2 (8.4) | 30.9 (6.0) | 39.8 (8.9) |

| Married (yes): % (n) | 94.0% (45) | 90.0% (27) | 100% (18) |

| Length of relationship | |||

| 2 years or less: % (n) | 27.1% (13) | 30.0% (9) | 22.2% (4) |

| 3–6 years: % (n) | 45.8% (22) | 46.7% (14) | 44.4% (8) |

| >6 years: % (n) | 27.1% (13) | 23.3% (7) | 33.3% (6) |

| Parity: mean (sd) | – | 2.7 (1.8) | – |

| Number of children: mean (sd) | 1.8 (1.4) | 1.8 (1.4) | 1.7 (1.5) |

| Electricity in the home (yes): % (n) | 97.9% (47) | 96.7% (29) | 100% (18) |

| Education and literacy: | |||

| Highest level of education completed | |||

| <Primary | 10.4% (5) | 13.3% (4) | 5.6% (1) |

| Primary: % (n) | 50.0% (24) | 50.0% (15) | 50.0% (9) |

| Secondary: % (n) | 20.8% (10) | 23.3% (7) | 16.7% (3) |

| >Secondary: % (n) | 18.8% (9) | 13.3% (4) | 27.8% (5) |

| Can you read a newspaper? | |||

| Easily: % (n) | 55.3% (26) | 37.9% (11) | 83.3% (15) |

| With difficulty: % (n) | 8.5% (4) | 6.9% (2) | 11.1% (2) |

| Not at all: % (n) | 36.2% (17) | 55.2% (16) | 5.6% (1) |

| HIV status and disclosure: | |||

| HIV-positive status (yes): % (n) | 85.4% (41) | 100% (30) | 61.1% (11) |

| Disclosed status to partner (yes): % (n) | 93.8% (45) | 90.0% (27) | 100% (18) |

3.2. Relationship priorities

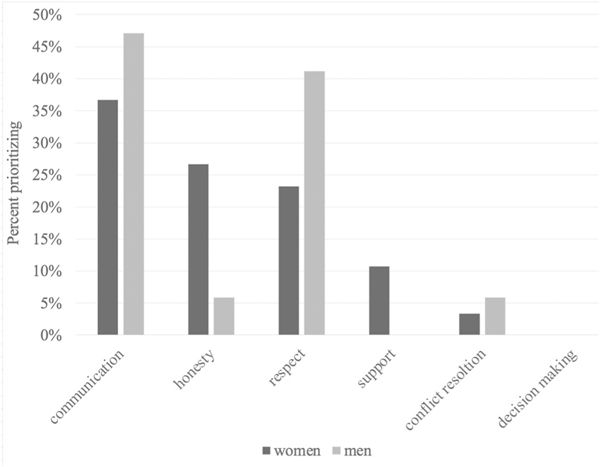

Forty-seven of the 48 participants completed the relationship topic pile sorting activity (see Fig. 2), with one male participant refusing to participate in the activity because he felt that all topics should be prioritized: “Everything here affects our families, communication, respect, honesty, conflict resolution … it is all in our families …. ” (Male, 47 years old). Among those that completed the activity, communication was the most prioritized relationship topic for both women (37%; n = 11) and men (47%; n = 8). For women, honesty was the second most prioritized relationship topic (27%; n = 8), followed by respect (23%; n = 7), support (11%; n = 3), and conflict resolution (3%; n = 1). Whereas for men, respect was the second most prioritized relationship topic (41%; n = 7), followed conflict resolution (6%; n = 1) and honesty (6%; n = 1). No men prioritized support, and neither men nor women prioritized decision-making. In the following paragraphs we discuss key themes that emerged during the interviews regarding participants’ explanations for the pile sorting results. Table 3 presents these themes by gender with illustrative quotations.

Fig. 2.

Pile sorting results on relationship topic priorities.

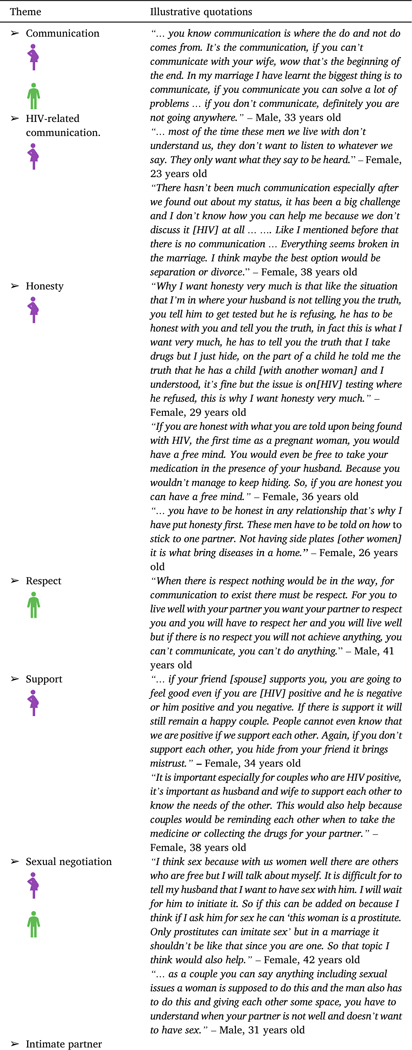

Table 3.

Themes and illustrative quotations from couples affected by HIV regarding relationship priorities.

|

|

3.2.1. Communication

Communication was discussed both within and outside the context of HIV as a critical component in relationships to avoid misunderstandings, make decisions, and be able to resolve problems. Both male and female participants emphasized that communication is the foundation of a healthy relationship. They based this view on the belief that without proper communication, “the marriage has no meaning” (47-year-old male). Both men and women emphasized that a break-down in communication is a break down in the foundation of marriage, making the relationship difficult to sustain. Among women, communication was reported as the most important topic of interest because it is the main way through which all other relationship dynamics are attained. Moreover, information-focused communication was discussed as especially important for couples living with HIV, because during pregnancy, women must be able to communicate important information about their health and PMTCT to their partner. Women additionally emphasized that without good communication skills, it is difficult to get male partners to accept women’s HIV-positive status or to convince men to be involved in the family’s health-related activities. Without proper HIV-related communication in couples, conflict can arise when one or both partners discovers they have HIV.

3.2.2. Respect

In addition to communication, many participants, especially male participants, prioritized respect. Male participants stated that mutual respect was needed for decision-making and conflict resolution. Male participants also explained that without respect, it is difficult for a couple to have a healthy relationship. For female participants, respect was not as prioritized, but some women reported that they felt mutual respect was lacking in their relationship and that men needed education on how to respect their wives, as this would reduce conflict in homes and promote marital harmony.

3.2.3. Honesty

A substantial proportion of female participants believed that honesty within couples should be prioritized. Honesty was not a priority topic for men. Women believed that honesty was critical for the ability of relationships affected by HIV to build trust, enhance love, and promote HIV-related health behaviors. Indeed, several female participants used status disclosure as an example of why honesty is particularly important in couples affected by HIV. Some women additionally prioritized honesty because they had negative experiences with their husbands, for example, having extra-marital affairs and being dishonest. Women often endorsed the belief that “dishonest men” are the ones who bring HIV into marriages, thus the need for honesty to be emphasized in couple-based interventions. Female participants stated that men in particular should be told the importance of honesty, which was often discussed interchangeably with infidelity and HIV risk.

3.2.4. Support

Support was prioritized by female participants as an important relationship topic. Women highlighted that support from male partners during pregnancy is critical for their physical and mental health. Support within couples, namely emotional and instrumental support, was described as being especially critical in couples when one, or both partners are living with HIV in order to promote happiness and well-being. The importance of promoting support within couples was also discussed by women in relation to couple HIV-related health behaviors. Conversely, men did not emphasize support as a priority relationships topic.

3.2.5. Sexual negotiations

In addition to the a priori relationship topics discussed above, the need to help couples with sexual negotiation also emerged as a priority topic. Both women and men reported a strong desire to have better skills in negotiating sex with their partners in order to ensure that their needs are being met. Women especially were interested in how to initiate sex given gender norms that dictate women are expected to be sexually passive.

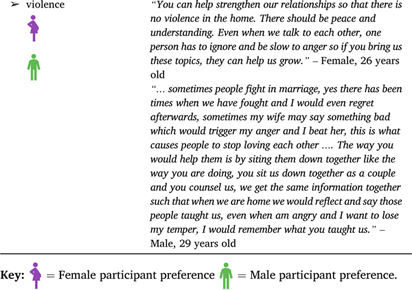

3.2.6. Intimate partner violence

A final relationship theme that emerged was the importance of counseling couples on intimate partner violence (IPV). Experiences of partner violence were not uncommon among our female participants. Both male and female participants additionally acknowledged a high prevalence of IPV in the community. Participants underscored the need for effective communication skills to prevent IPV, which often occurs as a result of women having HIV. Many WLWH suggested that the topic of violence be addressed in couples-based interventions. Some men confirmed that violence against women is common, or even that they themselves had used violence, and expressed a desire for couples to be taught how to reduce conflict and the use of violence.

Women’s safety in regard to IPV was an additional theme in the interviews. Despite numerous participants advocating for violence education in couple-based counseling interventions, some women in abusive relationships believed that participating in a couples-counseling intervention could jeopardize their safety. In the most extreme case, one 24-year-old woman explained that she would like to participate in a couples-based health education program but her violent and controlling husband would not allow it. She told us “… that is the day I will be killed now, me telling things to a counsellor.”

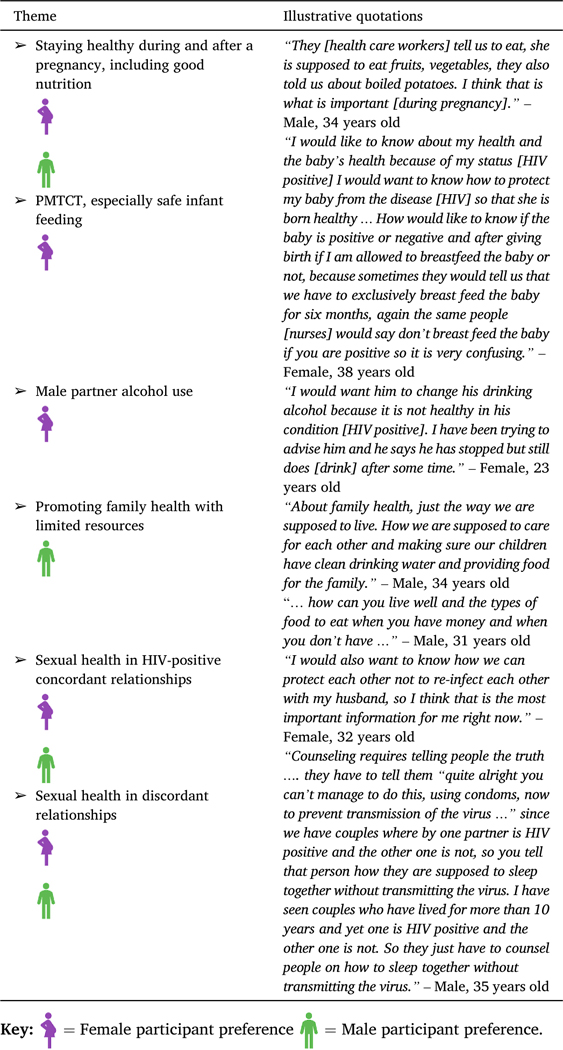

3.3. Family health priorities

3.3.1. Pregnancy-related health

Both genders emphasized the importance of learning how women can stay healthy during and after a pregnancy (see Table 4). Men and women highly endorsed the topic of good nutrition during pregnancy. Male participants also tended to emphasize the importance of women learning good hygiene practices at home in order to maintain good health during the pregnancy. Other men described wanting education on pregnancy-related medical conditions, such as preeclampsia, so that they could better understand pregnancy danger signs and ways to help their pregnant partners stay healthy. Several men also discussed the challenges of promoting their family’s health with limited resources and requested education on how to overcome this economic barrier effectively.

Table 4.

Themes and illustrative quotations from couples affected by HIV regarding health priorities.

|

3.3.2. PMTCT and breastfeeding

Female participants had a desire for more health education around PMTCT. Women revealed that they did not feel as though they had enough information on PMTCT, especially in relation to breastfeeding. Women discussed receiving conflicting instructions during ANC. For example, they reported that some nurses told them to breastfeed, while others told them this would transmit HIV to the infant. This conflicting information led to fear and confusion around transmitting HIV to the child and how to safely feed their newborn.

3.3.3. Men’s use of alcohol

Women also indicated concern about male partners’ alcohol use. Female participants explained that men, especially those who are living with HIV, need education about excessive alcohol consumption in the context of HIV. They discussed concerns for the male partner’s health, as well as how men’s excessive alcohol use negatively affects their lives and their family’s well-being.

3.3.4. Sexual health

A final theme within the interviews, which arose among both women and men, was education on sexual health in couples affected by HIV. Participants in both sero-concordant (HIV-positive) and sero-discordant relationships wanted health education on safe sex – both to avoid “re-infection” and transmission to sero-negative partners. Many participants emphasized that condoms are generally not acceptable within marriages and that it is very difficult to get men to use them. There was a strong desire to learn about other methods of safe sex and HIV prevention aside from condoms within couples where one or both partners are affected by HIV.

4. Discussion

Through qualitative interviews with pregnant WLWH and their male partners in Lusaka, Zambia, we learned the main relationship and health priorities of couples affected by HIV around the time of pregnancy. Some topics, such as communication in couples, pregnancy-related health, sexual health in the context of HIV, and sexual negotiation, were similarly prioritized and discussed among both genders. Other topics, however, were more emphasized by WLWH, such as honesty and support in relationships, PMTCT and breastfeeding education, and addressing male partners’ use of alcohol. Men, in contrast, prioritized respect in relationships and education on how to enhance family health with limited resources.

Qualitative and quantitative studies from other African settings have reported the same health priorities documented in the present study. A key theme among our male participants was their desire to comprehend how they can promote their family’s health with limited financial resources; prior research has found that financial support is often how men believe they are contributing to their family’s health (Rodriguez et al., 2020). Similar to a recent qualitative study from Kenya (Hurley et al., 2020), the WLWH we interviewed emphasized that breastfeeding decisions were often distressing because they received vastly inconsistent information about safe infant feeding in the context of HIV.

Another key health priority among WLWH whom we interviewed was men’s use of alcohol. A qualitative study from Malawi with couples affected by HIV found that women often tried to reduce their male partner’s alcohol intake because it caused men to be violent, have extramarital partnerships, and prevented them from meeting the basic needs of the family (Conroy et al., 2019). The intersection of men’s alcohol use, IPV, and risky sex was also supported in a large quantitative study using data from over 2000 South African men (Hatcher et al., 2019). This prior research helps explain why our female participants believed that reducing men’s alcohol use was a top health priority.

Findings from the present study support and build upon existing dyad-level frameworks that emphasize the importance of the “micro-social context” of heterosexual relationships (e.g., relationship commitment, love, trust, closeness, interdependence, IPV, communication, decision-making) for couple-based HIV interventions (Jiwatram-Negrón and El-Bassel, 2014 ). In particular, our findings highlight the applicability of the Interdependence Model of Couples Communal Coping developed by Lewis et al. (2006) as a theoretical framework to enhance PMTCT in settings such as Zambia. Among both the male and female participants we interviewed, interdependence (i.e., the ways in which interacting partners mutually influence each other’s outcomes) was clearly viewed as a key mechanism related to family health and well-being around the time of pregnancy. Our participants also viewed relationship functioning as a critical predisposing factor for interdependence and health promotion within families affected by HIV, which was also found among participants in a qualitative study with pregnant women and their male partners in Kenya (Rogers et al., 2016). These findings provide support for the argument that couple-based health promotion should target the couple relationship and interactions to have the greatest improvements in health outcomes (Lewis et al., 2006).

Although the Interdependence Model of Couples Communal Coping provides an overview of health behavior change at the dyad-level, it provides little in-depth guidance as to which relationship factors should be targeted as mechanisms for change within specific contexts. Our study indicates that couples-based interventions aimed at promoting family health during and after pregnancy in the context of HIV may be more effective if they focus on enhancing communication, along with honesty, respect, and support, and considering IPV. In this study, both pregnant WLWH and their male partners focused heavily on communication forming the foundation of a strong, healthy relationship. They argued that communication is the only way a couple can successfully have decision-making and conflict resolution skills. Moreover, participants emphasized that among couples affected by HIV, communication is even more critical to be able to express one’s HIV-specific needs and concerns and resolve issues that emerge due to HIV in the relationship. In addition to communication, our qualitative themes highlight other relationship attributes most relevant for couples affected by HIV in settings like Zambia, including honesty, respect, and emotional and instrumental support.

Although many participants expressed an interest in couple-based interventions incorporating counseling on IPV, the safety of women should always be a priority. Indeed, we had female participants in violent relationships express concern about violence, even fatal violence, if they were to participate in a couple-based HIV intervention. The World Health Organization has specific safety and ethical guidelines on interventions with women in violent relationships, which we strongly encourage couple-based interventions to follow (WHO, 2001). Prior research does suggest, however, that couple-based interventions do not result in increased IPV among women (Semrau et al., 2005; Turan et al., 2018). In an effort to prevent IPV against women who are at high risk, prior couple-based HIV intervention studies have often excluded certain women, such as those who report any IPV in the past month (Krakowiak et al., 2016) or report severe IPV in the past 6 months (Turan et al., 2018). Yet, more research is needed into the safety of couple-based HIV interventions for women during pregnancy. There is a need for better scientific consensus regarding how to enable women with IPV to benefit from couples-based interventions that could promote their and their children’s health while preventing them from situations that could increase the risk of IPV.

Our findings have important implications for the development of relationship-focused HIV interventions, particularly during and after pregnancy. In sub-Saharan Africa, prior couples-based interventions for HIV prevention and other sexual and reproductive health outcomes have tended to emphasize, or at least incorporate, communication skills (Darbes et al., 2019; Hartmann et al., 2012; Pettifor et al., 2014), including some trials during and after pregnancy (Turan et al., 2018; Weiss et al., 2014; Sifunda et al., 2019). These studies report positive intervention effects on couple HIV testing (Turan et al., 2018; Darbes et al., 2019) condom use (Pettifor et al., 2014), infant HIV prophylaxis dosing (Weiss et al., 2014), and infant HIV-free survival (Sifunda et al., 2019). These results are in line with a review focused on couple-based HIV approaches in the United States, which found that the core components of interventions to promote HIV treatment adherence often included improving communication (El-Bassel et al., 2010). Unfortunately, the majority these studies do not report on whether relationship skills targeted by their interventions were mediating or moderating factors on study outcomes. There is evidence, however, from one Kenyan study (Hatcher et al., 2020) that a home-based couples counseling and HIV testing intervention resulted in better couple communication, which increased efficacy to act together around HIV and promoted couple HIV testing.

In addition to communication, the pregnant WLWH we interviewed focused heavily on the role of supportive actions of their partners to promote their and their children’s health, which aligns with the relationship process perspective of social support (Reis and Collins, 2000). The relationship process perspective of social support compliments the Interdependence Model of Couples Communal Coping by highlighting the role of supportive actions of others, including intimate partners, such as advice and reassurance, and an individual’s perception of social support, which can improve health behaviors and outcomes (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). Many of our participants further emphasized the interconnectedness of various relationship factors, which is not found in the Interdependence Model of Couples Communal Coping. The relationship process perspective within social support similarly discusses several dimensions that are particularly influential on the level of social support, such as partner responsiveness, couple interdependence, and sentiment, but does not postulate relationships between these dimensions (Reis and Collins, 2000). Moving forward, additional research is needed to determine which relationship factors are the most influential for specific HIV behavioral outcomes, and the interconnection between different, potentially modifiable mechanisms at the relationship-level.

4.1. Limitations

The findings of this study should be interpreted within its limitations. Participants were recruited from a large government health facility in an urban setting. Thus, the findings may not be generalizable outside of this specific context and population. Despite every effort to make participants comfortable disclosing information, there is the potential for social desirability bias where participants may not, in all cases, have been universally honest with the researchers. Given the iterative nature of the interviews, information in the later interviews may have been more comprehensive than in our earlier interviews.

5. Conclusions

A major contribution of this study is a better understanding of the dyad-level mechanisms influencing the health of couples affected by HIV around the time of pregnancy, as well as partners’ specific health priorities. Couple-based interventions for pregnant WLWH and their male partners offer a unique opportunity to promote engagement in HIV care and treatment while reducing relationship distress and increasing relationship satisfaction (El-Bassel and Wechsberg, 2012; Hatcher et al., 2014; Hampanda, 2016). The findings of the present study inform the specific health topics and relationship skills that will have the greatest likelihood of being well-received among pregnant WLWH and their male partners in this Zambian context, and subsequently, lead to efficacy in promoting PMTCT and family health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Support for this project was provided by the U.S. National Institutes of Health under awards K99 MH116735, R00 MH116735 and K24 AI120796.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114029.

References

- Abbamonte JM, Ramlagan S, Lee TK, Cristofari NV, Weiss SM, Peltzer K, Sifunda S, Jones DL, 2020. Stigma interdependence among pregnant HIV-infected couples in a cluster randomized controlled trial from rural South Africa. Soc. Sci. Med. 253, 112940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AMFAR, 2016. Statistics: Women And HIV/AIDS [Online]. The Foundation for AIDS Research. Available: http://www.amfar.org/about-hiv-and-aids/facts-and-stats/statistics–women-and-hiv-aids/. [Google Scholar]

- Becker S, Taulo FO, Hindin MJ, Chipeta EK, Loll D, Tsui A, 2014. Pilot study of home-based delivery of HIV testing and counseling and contraceptive services to couples in Malawi. BMC Publ. Health 14, 1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell KM, Naugle AE, 2008. Intimate partner violence theoretical considerations: moving towards a contextual framework. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 28, 1096–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G, Shantinath SD, 2004. The couples coping enhancement training (CCET): a NewApproach to prevention of marital DistressBased upon stress and coping. Fam. Relat. 53, 477–484. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RPC, Friend DJ, Gottman JM, 2011. Supporting healthy relationships in low-income, violent couples: reducing conflict and strengthening relationship skills and satisfaction. J. Couple & Relatsh. Ther. 10, 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Burton J, Darbes LA, Operario D, 2010. Couples-focused behavioral interventions for prevention of HIV: systematic review of the state of evidence. AIDS Behav. 14, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byamugisha R, Astrom AN, Ndeezi G, Karamagi CA, Tylleskar T, Tumwine JK, 2011. Male partner antenatal attendance and HIV testing in eastern Uganda: a randomized facility-based intervention trial. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 14, 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K, 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. Sage, London; Thousand Oaks, Calif. [Google Scholar]

- Conroy AA, Ruark A, Mckenna SA, Tan JY, Darbes LA, Hahn JA, Mkandawire J, 2019. The unaddressed needs of alcohol-using couples on antiretroviral therapy in Malawi: formative research on multilevel interventions. AIDS Behav. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CSO, 2014. Zambia Demographic and Health Survey 2013–14. Central Statistical Office, Ministry of Health, and ICF International, Rockville, Maryland, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Darbes LA, Mcgrath NM, Hosegood V, Johnson MO, Fritz K, Ngubane T, Van Rooyen H, 2019. Results of a couples-based randomized controlled trial aimed to increase testing for HIV. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 80, 404–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darbes LA, Van Rooyen H, Hosegood V, Ngubane T, Johnson MO, Fritz K, Mcgrath N, 2014. Uthando Lwethu (‘our love’): a protocol for a couples-based intervention to increase testing for HIV: a randomized controlled trial in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Trials 15, 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditekemena J, Matendo R, Koole O, Colebunders R, Kashamuka M, Tshefu A, Kilese N, Nanlele D, Ryder R, 2011. Male partner voluntary counselling and testing associated with the antenatal services in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo: a randomized controlled trial. Int. J. STD AIDS 22, 165–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drisko J, 1997. Strengthening qualitative studies and reports: standards to promote academic integrity. J. Soc. Work. Educ. 33, 185–197. [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Witte S, Wu E, Hunt T, Remien RH, 2010. Couple-based HIV prevention in the United States: advantages, gaps, and future directions. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 55 (Suppl. 2), S98–S101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Wechsberg WM, 2012. Couple-based behavioral HIV interventions: placing HIV risk-reduction responsibility and agency on the female and male dyad. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice 1, 94. [Google Scholar]

- Ezeanolue EE, Obiefune MC, Ezeanolue CO, Ehiri JE, Osuji A, Ogidi AG, Hunt AT, Patel D, Yang W, Pharr J, Ogedegbe G, 2015. Effect of a congregation-based intervention on uptake of HIV testing and linkage to care in pregnant women in Nigeria (Baby Shower): a cluster randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health 3, e692–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J, Thorogood N, 2014. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. SAGE, Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- Hampanda K, 2016. Intimate partner violence and HIV-positive women’s non-adherence to antiretroviral medication for the purpose of prevention of mother-to-child transmission in Lusaka, Zambia. Soc. Sci. Med. 153, 123–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampanda K, Abuogi L, Musoke P, Onono M, Helova A, Bukusi E, Turan J, 2019. Development of a novel scale to measure male partner involvement in the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Kenya. AIDS Behav. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampanda KM, Nimz AM, Abuogi LL, 2017. Barriers to uptake of early infant HIV testing in Zambia: the role of intimate partner violence and HIV status disclosure within couples. AIDS Res. Ther. 14, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann M, Gilles K, Shattuck D, Kerner B, Guest G, 2012. Changes in couples’ communication as a result of a male-involvement family planning intervention. J. Health Commun. 17, 802–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher AM, Darbes L, Kwena Z, Musoke PL, Rogers AJ, Owino G, Helova A, Anderson JL, Oyaro P, Bukusi EA, Turan JM, 2020. Pathways for HIV prevention behaviors following a home-based couples intervention for pregnant women and male partners in Kenya. AIDS Behav. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher AM, Gibbs A, Mcbride RS, Rebombo D, Khumalo M, Christofides NJ, 2019. Gendered syndemic of intimate partner violence, alcohol misuse, and HIV risk among peri-urban, heterosexual men in South Africa. Soc. Sci. Med. 112637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher AM, Smout EM, Turan JM, Christofides N, Stockl H, 2015. Intimate Partner Violence and Engagement in HIV Care and Treatment Among Women: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Aids. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher AM, Stöckl H, Christofides N, Woollett N, Pallitto CC, Garcia-Moreno C, Turan JM, 2016. Mechanisms linking intimate partner violence and prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: a qualitative study in South Africa. Soc. Sci. Med. 168, 130–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher AM, Woollett N, Pallitto CC, Mokoatle K, Stockl H, Macphail C, Delany-Moretlwe S, Garcia-Moreno C, 2014. Bidirectional links between HIV and intimate partner violence in pregnancy: implications for prevention of mother-to-child transmission. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 17, 19233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley EA, Odeny B, Wexler C, Brown M, Mackenzie A, Goggin K, Maloba M, Gautney B, Finocchario-Kessler S, 2020. It was my obligation as mother”: 18-Month completion of Early Infant Diagnosis as identity control for mothers living with HIV in Kenya. Soc. Sci. Med. 250, 112866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiwatram-Negrón T, El-Bassel N, 2014. Systematic review of couple-based HIV intervention and prevention studies: advantages, gaps, and future directions. AIDS Behav. 18, 1864–1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakowiak D, Kinuthia J, Osoti AO, Asila V, Gone MA, Mark J, Betz B, Parikh S, Sharma M, Barnabas R, Farquhar C, 2016. Home-based HIV testing among pregnant couples increases partner testing and identification of serodiscordant partnerships. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 72 (Suppl. 2), S167–S173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S, 1984. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Springer Pub. Co, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Mcbride CM, Pollak KI, Puleo E, Butterfield RM, Emmons KM, 2006. Understanding health behavior change among couples: an interdependence and communal coping approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 62, 1369–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohlala BK, Boily MC, Gregson S, 2011. The forgotten half of the equation: randomized controlled trial of a male invitation to attend couple voluntary counselling and testing. AIDS 25, 1535–1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyondo AL, Choko AT, Chimwaza AF, Muula AS, 2015. Invitation cards during pregnancy enhance male partner involvement in prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in Blantyre, Malawi: a randomized controlled open label trial. PloS One 10, e0119273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okawa S, Chirwa M, Ishikawa N, Kapyata H, Msiska CY, Syakantu G, Miyano S, Komada K, Jimba M, Yasuoka J, 2015. Longitudinal adherence to antiretroviral drugs for preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Zambia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 15, 258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osoti AO, John-Stewart G, Kiarie J, Richardson B, Kinuthia J, Krakowiak D, Farquhar C, 2014. Home visits during pregnancy enhance male partner HIV counselling and testing in Kenya: a randomized clinical trial. AIDS 28, 95–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelto PJ, 2013. Applied Ethnography : Guidelines for Field Research. Left Coast Press, Inc, Walnut Creek, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Pettifor A, Macphail C, Nguyen N, Rosenberg M, Parker L, Sibeko J, 2014. Feasibility and acceptability of Project Connect: a couples-based HIV-risk reduction intervention among young couples in Johannesburg, South Africa. AIDS Care 26, 476–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis HT, Collins N, 2000. Measuring relationship properties and interactions relevant to social support. In: COHEN S, UNDERWOOD LG, GOTTLIEB BH (Eds.), Social Support Measurement and Intervention: A Guide for Health and Social Scientists. Oxford University Press, New York, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez VJ, Parrish MS, Jones DL, Peltzer K, 2020. Factor structure of a male involvement index to increase the effectiveness of prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT) programs: revised male involvement index. AIDS Care 32, 1304–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers AJ, Achiro L, Bukusi EA, Hatcher AM, Kwena Z, Musoke PL, Turan JM, Weke E, Darbes LA, 2016. Couple interdependence impacts HIV-related health behaviours among pregnant couples in southwestern Kenya: a qualitative analysis. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 19, 21224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg NE, Mtande TK, Saidi F, Stanley C, Jere E, Paile L, Kumwenda K, Mofolo I, Ng’Ambi W, Miller WC, Hoffman I, Hosseinipour M, 2015. Recruiting male partners for couple HIV testing and counselling in Malawi’s option B + programme: an unblinded randomised controlled trial. Lancet HIV 2, e483–e491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield MJ, Mumford N, Jurkovic D, Jurkovic I, Bickerdike A, 2012. Short and long-term effectiveness of couple counselling: a study protocol. BMC Publ. Health 12, 735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semrau K, Kuhn L, Vwalika C, Kasonde P, Sinkala M, Kankasa C, Shutes E, Aldrovandi G, Thea DM, 2005. Women in couples antenatal HIV counseling and testing are not more likely to report adverse social events. AIDS (London, England) 19, 603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sifunda S, Peltzer K, Rodriguez VJ, Mandell LN, Lee TK, Ramlagan S, Alcaide ML, Weiss SM, Jones DL, 2019. Impact of male partner involvement on mother-to-child transmission of HIV and HIV-free survival among HIV-exposed infants in rural South Africa: results from a two phase randomised controlled trial. PloS One 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangler SA, Abuogi LL, Akama E, Bukusi EA, Helova A, Musoke P, Nalwa WZ, Odeny TA, Onono M, Wanga I, Turan JM, 2018. From “half-dead’ to being “free’: resistance to HIV stigma, self-disclosure and support for PMTCT/HIV care among couples living with HIV in Kenya. Cult. Health Sex. 20, 489–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theuring S, Jefferys LF, Nchimbi P, Mbezi P, Sewangi J, 2016. Increasing partner attendance in antenatal care and HIV testing services: comparable outcomes using written versus verbal invitations in an urban facility-based controlled intervention trial in mbeya, Tanzania. PloS One 11, e0152734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilahun T, Coene G, Temmerman M, Degomme O, 2015. Couple based family planning education: changes in male involvement and contraceptive use among married couples in Jimma Zone, Ethiopia. BMC Publ. Health 15, 682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turan JM, Darbes LA, Musoke PL, Kwena Z, Rogers AJ, Hatcher AM, Anderson JL, Owino G, Helova A, Weke E, et al. , 2018. Development and piloting of a home-based couples intervention during pregnancy and postpartum in southwestern Kenya. AIDS Patient Care & Stds 32, 92–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unaids, 2019. Start Free Stay Free AIDS Free: 2019 Report. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF, 2017. Zambia - prevention of mother-to-child transmission: key statistics. Online]. Available: https://www.unicef.org/zambia/5109_8456.html.

- Wamoyi J, Renju J, Moshabela M, Mclean E, Nyato D, Mbata D, Bonnington O, Seeley J, Church K, Zaba B, 2017. Understanding the relationship between couple dynamics and engagement with HIV care services: insights from a qualitative study in Eastern and Southern Africa. Sex. Transm. Infect. 93, e052976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss SM, Peltzer K, Villar-Loubet O, Shikwane ME, Cook R, Jones DL, 2014. Improving PMTCT uptake in rural South Africa. J. Int. Assoc. Phys. AIDS Care 13, 269–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO, 2001. Putting Women First: Ethical and Safety Recommendations for Research on Domestic Violence against Women. Department of Gender and Women’s Health: Family and Community Health. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switerland. [Google Scholar]

- WHO, 2012. Male Involvement in Prevention of Mother-To-Child Transmission of HIV. World Health Organization, Geneva. Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- WHO, 2016. Progress Report 2016: Prevent HIV, Test and Treat All: WHO Support for Country Impact. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Zambia Statistics Agency, M.O.H.M.Z., Icf, 2019. Zambia Demographic and Health Survey 2018. Lusaka, Zambia. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.