Abstract

Background:

Latino families are disproportionately affected by type 2 diabetes (T2D) and lifestyle intervention is the first-line approach for preventing T2D. The purpose of this study is to test the efficacy of a culturally-grounded lifestyle intervention that prioritizes health promotion and diabetes prevention for Latino families. The intervention is guided by a novel Family Diabetes Prevention Model, leveraging the family processes of engagement, empowerment, resilience, and cohesion to orient the family system towards health.

Method:

Latino families (N = 132) will be recruited and assessed for glucose tolerance as measured by an Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT) and General and Weight-Specific Quality of Life (QoL) at baseline, four months, and 12 months. All members of the household age 10 and over will be invited to participate. Families will be randomized to the intervention group or a control group (2:1). The 16-week intervention includes weekly nutrition and wellness classes delivered by bilingual, bicultural Registered Dietitians and community health educators at a local YMCA along with two days/week of supervised physical activity classes and a third day of unsupervised physical activity. Control families will meet with a physician and a Registered Dietitian to discuss the results of their metabolic testing and recommend lifestyle changes. We will test the efficacy of a family-focused diabetes prevention intervention for improving glucose tolerance and increasing QoL and test for mediators and moderators of long-term changes.

Conclusion:

This study will provide much needed data on the efficacy of a family-focused Diabetes Prevention Program among high-risk Latino families.

Keywords: Latino Type 2 diabetes, Obesity, Diabetes Prevention, Health Disparity

Introduction

Latino communities are disproportionately impacted by obesity and type 2 diabetes (T2D).1 Latino youth exhibit the highest rates of overweight and obesity (26.2%) among all racial and ethnic groups2 and have a greater prevalence of prediabetes compared to their non-Hispanic white counterparts (22.9% vs 15.1%).3 Similarly, Latino adults have the highest rates of prediabetes (41.6%) and T2D (22.1%).4 Latinos represent the largest minority subgroup in the U.S., at >60 million (18.3%); yet, they have remained underserved by the healthcare sector.5 While T2D is a highly heritable disease,6 the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) established that it can be prevented or delayed in high-risk individuals through intensive lifestyle intervention.7,8 Although the DPP has been translated to various populations and settings,9 it has not been adapted to meet the specific needs of Latino families at high risk for diabetes. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to describe the study protocol of a diabetes prevention intervention for high-risk Latino families.

Framework

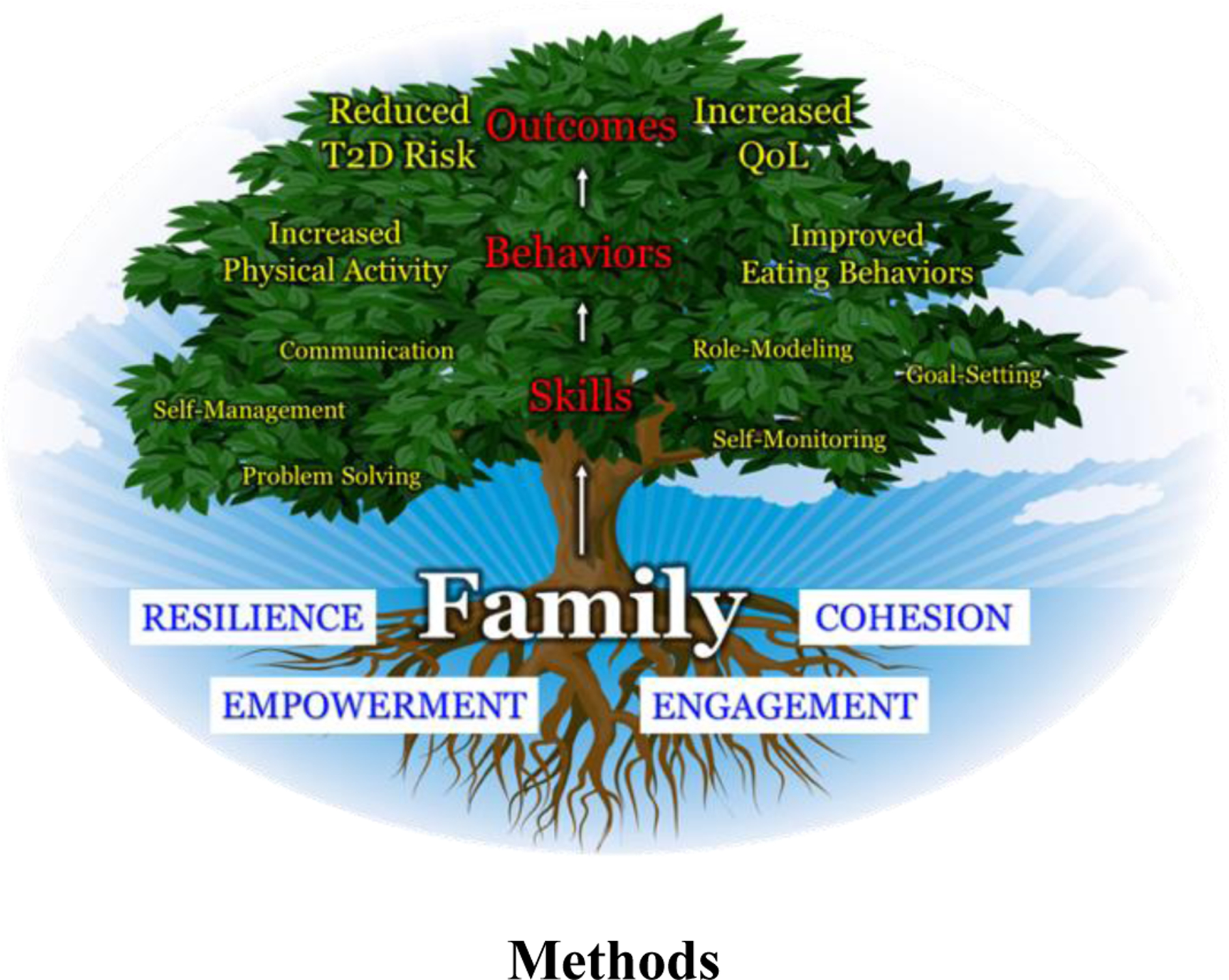

Among many Latino families, the construct of familismo (familism) is a traditional cultural orientation that emphasizes bonding and supportive familial relationships.10 Using this relevant cultural construct and in collaboration with our community partners, we developed a novel Family Diabetes Prevention Model to guide diabetes prevention efforts that is grounded in the family system (See Figure 1). The model is based upon the extant literature as well as our extensive experience working with Latino families in the local community to leverage family processes of engagement, empowerment, resilience, and cohesion to orient the family system towards health. For the purposes of this model we adapted and operationalized the following definitions to support diabetes prevention in high-risk families. Engagement -interacting as a family, with other families, health educators, and the environment to take actions to improve the health of the family system.11 Empowerment - acquiring knowledge, skills and capacity to identify and utilize resources to improve health and reduce diabetes risk.12 Resilience - leveraging strengths, relationships, cultural values, and assets in order to respond to the pathogenic forces underpinning T2D so that the family can flourish as a healthy system.13 Cohesion - strengthening bonds within families by decreasing conflict and prioritizing the health of the family system around a shared purpose and health goal.14 The model leverages these processes along with Familismo to anchor behavioral skills training aimed at promoting healthy behaviors to improve health outcomes. Grounding prevention efforts within the local cultural context can enhance relevancy, engagement, and efficacy among communities that experience health disparities.15

Figure 1.

Family Diabetes Prevention Model.

Methods

Trial Design

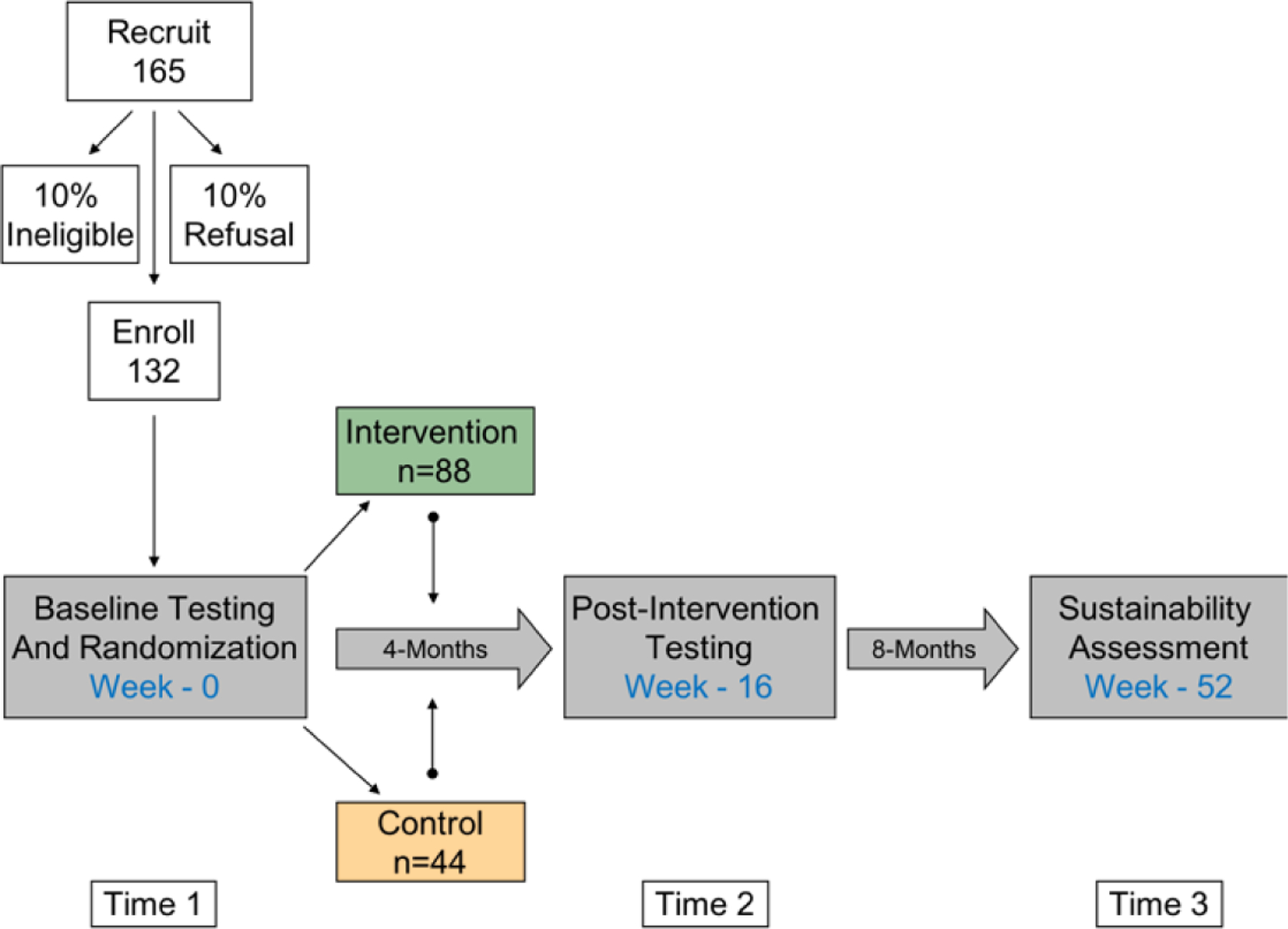

This randomized clinical trial will include 132 Latino families (children, parents/guardians, and additional household members). All enrolled families will undergo the data collection at baseline (T1), 4 months (T2 – Post-Intervention), and 12 months (T3 - Sustainability) to examine the impact of the intervention on primary and secondary outcomes over time (described below).

Objective

We will test the general hypothesis that a culturally-grounded, diabetes prevention intervention will significantly improve glucose tolerance and increase Quality of Life (QoL) among high-risk Latino families.

Participants

Families will be eligible to enroll if they have at least 1 child and at least 1 parent/guardian who meet the inclusion criteria. Children will be included in the study if they self-report as Latino, age 10–16, and have either a BMI ≥ 95th percentile for age and sex18 or if their BMI is ≥85th percentile and their baseline laboratory values indicate prediabetes according to American Diabetes Association criteria (fasting glucose ≥ 100 mg/dl, 2-hr glucose ≥ 140 mg/dl, or HbA1c ≥ 5.7%). This age range was selected based on the American Diabetes Association recommendation for screening prediabetes and T2D among children starting at age 10.19 Children will be excluded from the study if 1) they have diabetes (defined as fasting blood glucose ≥ 126 ml/dl, or 2-hour glucose ≥200 ml/dl, HbA1c ≥ 6.5%, physician diagnosis of diabetes, or diabetes treatment);20 2) they are taking medications for or are diagnosed with a condition that interferes with carbohydrate metabolism, physical activity, and/or cognition, or 3) they are currently enrolled in a formal weight loss program or have been within the last 12 months.

Adults are eligible to participate if they are a parent/guardian of a child who meets the above criteria. Parents/guardians will be excluded if they are currently enrolled in a formal weight loss program or have been within the last 12 months. There is no exclusion of adults based on their lab values; however, if adults are found to have diabetes during screening, whether this is a known condition or previously undiagnosed, they will be required to provide a medical clearance letter from a primary care provider in order to participate in the physical activity portion of the intervention.

An eligible family is defined as at least one child and one parent or guardian. To acknowledge the potential of multigenerational and extended family households, additional adults in the household regardless of relationship to the eligible child will be invited to participate in laboratory visits and if the family is randomized to the intervention arm of the trial, all members of the household will be encouraged to attend intervention sessions.

Recruitment Strategies

The research team has established a multi-pronged strategy for recruiting Latino children and families for research studies.21 Our research team also has ongoing relationships with several community clinics, agencies, and resources who assist in recruitment. This network includes local ambulatory care clinics, Latino- serving Federally Qualified Health Centers, and large health systems. In addition, our community partner, the Ivy Center for Family Wellness at the St. Vincent de Paul Medical and Dental Clinic is an established and trusted entity in the local Latino community that provides primary care and specialty services to Latino children and families. Other recruitment strategies include the use of culturally-appropriate media outlets as well as word of mouth recruitment from previous study participants. Flyers will be distributed to local schools, community centers, churches, Latino serving agencies, and healthcare organizations in the greater Phoenix area. To support enrollment, our team includes bilingual/bicultural research staff to assist with recruitment, consenting, enrollment, and data collection.

Randomization and Sample Size

A total of 132 Latino families (children, parents/guardians, and additional household members), who will be randomized (2:1) to intervention (N = 88) or control group (N = 44). Randomization is stratified by sex of the oldest eligible child using a random number generator by the study methodologist after eligibility has been determined. Study staff is blinded to group assignment until disclosed by the methodologist at which point families are informed. Sample size calculations are based on effects sizes (Cohen’s d) from our previous work with Latino youth (d=0.52–0.60) and a meta-analysis of adult lifestyle interventions (d=0.65)16 Sample size calculations were estimated using an effect size for changes in 2-hour glucose concentrations after an Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT) of d=0.52, α=0.05, power=0.80, the proportion of variance in post intervention glucose tolerance explained by baseline glucose tolerance r2=0.167, and a 12% allocation ratio increase for the 2:1 randomization schedule.17 A sample size of 126 families is required in order to achieve a minimum detectable intervention effect size d=0.52 in glucose tolerance. Effect sizes for QoL in our previous studies range from d=0.43–0.52 with a larger proportion of variance in post intervention QoL explained by baseline (r2=0.51). Therefore, using the proposed sample size of 126 families while assuming d=0.43, α=0.05, and r2=0.51, we will have 90% power to detect significant intervention effects in QoL. We will oversample to include N=132 families.

Lifestyle Intervention

The 16-week intervention curriculum was developed by our community partners and refined over the past 15 years and includes nutrition education, behavioral change skills training, and physical activity.22–25 The curriculum is informed by Social Cognitive Theory26 and applies key behavioral change strategies from the DPP such as goal-setting, monitoring, fostering social support, and enhancing self-efficacy to facilitate behavior change.27 The curriculum is grounded in the local Latino culture to enhance meaning within the Latino community.28 Cultural constructs include familismo (familism), confianza (trust), respeto (respect), and personalismo (personal interaction). The intervention along with the associated activities and exercises are designed to engage children as well as parents/guardians.

Home Visit

To enhance engagement of the entire household, a home visit will be conducted prior to beginning the formal lifestyle intervention. Families randomized to the intervention arm receive a home visit from the interventionists in order to build rapport, discuss program goals, and answer questions.

Nutrition and Wellness Education

The intervention group will participate in 16 weekly nutrition and wellness classes delivered by bilingual/bicultural Registered Dietitians and community health educators. The curriculum focuses on developing family skills to increase health behaviors including communication, goal-setting, self-management, problem-solving, role-modeling, and self-monitoring. Class topics include understanding diabetes, using the plate method, understanding nutrition labels, and understanding roles and responsibilities; see Table 2 for a complete list of classes and objectives. The intervention will be delivered at a local YMCA to families in groups. At the end of each class, families will work together to establish a weekly SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound) goal and then discuss these goals as a group at the following class.29 Each week, SMART goals will be reviewed and either modified or new goals will be set. The SMART goal format is used when setting a goal to allow for attainable and measurable outcomes.30

Table 2.

Nutrition and Wellness Classes’ Weekly Objectives.

| Class | Title | Objective |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Orientation | Meet the team and the other families Identify the purpose, goals, and expectations of the program Evaluate readiness to make healthy lifestyle changes |

| 2 | What is Diabetes? | Explore ways to describe foods to understand food and taste preferences Define prediabetes and identify 1–2 risk factors for developing T2D Develop SMART goals to achieve long-term health goals |

| 3 | Champions in Health | Identify 2–3 common lab values related to diabetes Recognize how to have positive weight-related conversations Identify benefits of going to the doctor and questions to ask |

| 4 | Champions in Eating | Identify the food groups and portion sizes in the Plate Method Categorize different food groups according to the Plate Method Practice creating 1 meal as a family using Plate Method as a guide |

| 5 | Roles and Responsibilities | Identify and compare roles and responsibilities of parents and children when it comes to eating and food Practice the roles and responsibilities through a role-playing activity |

| 6 | Sugars and Fats | List the different types of food that contain sugar and fat Identify the different types of sugars and fats found in food Identify the benefits of limiting added sugar and saturated fat Describe ways to limit added sugar and saturated fat |

| 7 | Nutrition Facts Label | Practice using the nutrition facts label to make nutritious choices Discuss strategies to cut down on the amount of added sugars in our foods and drinks using the nutrition label |

| 8 | Eating Together | Prepare a meal as a family Reflect on experiences with the division of responsibilities for parent(s) and children at the time of eating Share positive contributions about family members’ role in meal preparation |

| 9 | Shopping for Health | Practice roles and responsibilities for eating by the plate method Build one healthy meal on a budget Identify how meal planning and budgeting can support health goals |

| 10 | Building Self-Esteem | Define self-esteem Identify the steps needed to achieve a healthy self-esteem List ways to care for yourself through self-love Identify opinions, ideas, preferences, and traits that define each person |

| 11 | Managing Feelings | Become aware of the 4 feelings: Happy, Sad, Angry and Scared Identify how reactions to people, places, and things affect feelings Learn relaxation techniques to help stay grounded |

| 12 | Building Support | Reflect on communication skills and problem-solving as a family Discuss progress, challenges, and solutions to making lifestyle changes to prevent T2D Identify how to build support for making lifestyle changes to prevent T2D |

| 13 | Exploring my Environment | Recognize environmental barriers to making healthy lifestyle choices Identify resources and opportunities in the environment to support healthy lifestyle choices Discuss strategies to overcome barriers in the environment to eat healthily and be active |

| 14 | Family Dynamics | Illustrate how different personalities interact in family relationships Identify how different personalities influence building healthy relationships Recognize how individual personalities in the family play a role in developing a healthy lifestyle |

| 15 | Mindful Eating | Discuss ways to practice mindful eating Identify ways to build a healthy relationship with food Practice using the Hunger-Fullness Scale to identify hunger and fullness |

| 16 | Staying Strong | Identify ways to practice self-care and the benefits Understand what resilience is and habits that build resilience Acknowledge success during the program through affirmations |

Physical Activity

The activity component of the program includes 60 minutes of supervised physical activity two days/week and a third day of unsupervised physical activity. The supervised physical activity, delivered by YMCA trainers, is designed to increase physical fitness and improve daily physical functioning. Physical activity classes are delivered in groups and consist of aerobic and resistance exercises that progress over time. The moderate-to-vigorous physical activity sessions are designed to elicit an average heart rate of at least 150 beats per minute among children and a rate of perceived exertion (RPE) of 5–7 on a 10-point scale among adults. Families are ‘prescribed’ a third day of unsupervised physical activity, lasting at least 60-minutes, to be done on their own. This allows for flexibility in training and encourages social support, role-modeling, bonding, and sustainability among participants. This third day allows participants to choose what activity they want to do and encourages them to find activities they enjoy doing as a family, going beyond solely the options available at the YMCA. The dose of 180 minutes of physical activity per week is in line with the adult DPP7 and has been shown to improve cardiometabolic health in children with obesity.31

Family Comparison Control

Upon completion of the 4-month laboratory visit, families randomized to the comparison control group will meet with the study Physician and a Registered Dietitian to review lab results and receive lifestyle counseling via a virtual meeting platform or phone call. This visit will occur after the Time 2 laboratory testing is completed. Lifestyle counseling is designed to engage the family unit, both adults and children. Both the study Physician and a Registered Dietitian routinely work to engage families and children in their clinical work, and our previous work showed no issues with children being able to uptake messages. After completing the final laboratory visit at 12 months, families in the comparison group will be provided with a 6-month YMCA membership.

Laboratory Visits for All Participants, Regardless of Intervention Group

At all 3 timepoints (baseline, 4-months – Post-Intervention, 1-year - Sustainability), participants will arrive at the ASU Clinical Research Unit at ~8:00 a.m. after an overnight fast of at least 8 hours. At baseline (T1), family and medical history, including diabetes (of any type) and in utero exposure to diabetes (either gestational or pre-gestational), will be obtained. At 4-months (T2) and 1 year (T3), any changes to medical conditions or medication use is determined. At all 3 time points, investigators will also collect height, weight, and waist circumference, measured to the nearest 0.1 cm, 0.1 kg. 0.1 cm, respectively; BMI and BMI percentiles will be calculated.18 Seated blood pressure will be obtained, and temperature measured to rule out acute illness. If a participant has signs and symptoms of acute illness, the testing visit will be rescheduled. A fasting blood sample will be collected to determine cholesterol (Total, HDL, and estimated LDL), triglycerides, liver transaminases, and HbA1c.

Study Measures

Table 1 lists the measures assessed in this study, in whom and at what timepoint. The primary outcomes are changes in glucose tolerance, as measured by 2-hour glucose concentrations following an OGTT and changes in generic and Weight-Specific Quality of Life (QoL) as measured by validated questionnaires. Additional measures include body composition, physical activity, eating behaviors, anthropometrics, and selected fasting lab values. Potential mediators include family engagement, empowerment, cohesion, and resilience (See Table 1). Additional measures to be collected include family structure and history of diabetes, acculturation, socioeconomic status, and pubertal development (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Measures and Timepoints

| Measure | In Whom | T1 Baseline |

T2 Post-Intervention |

T3 Sustainability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Primary Outcomes • Glucose Tolerance |

Parent Child Additional Adults |

X |

X |

X |

| • Generic and weight-specific quality of life | Parent Child Additional Adults |

X |

X |

X |

|

Additional Measures • Total Body Composition (DEXA) |

Parent Child |

X |

X |

|

| • Physical Activity | Parent Child |

X | X | |

| • Dietary Behaviors | Parent Child |

X | X | X |

| • Fasting labs (cholesterol, triglycerides, liver transaminases, HbA1c) | Parent Child Additional Adult |

X | X | X |

| • Anthropometric measures (height, weight, waist circumference) | Parent Child Additional Adult |

X | X | X |

|

Potential Mediators • Family Engagement |

Intervention Families |

X |

||

| • Family Empowerment | Parent | X | X | X |

| • Family Cohesion | Parent | X | X | X |

| • Family Resilience | Parent | X | X | X |

Note. T1 measures baseline, T2 measures Post-Intervention (4 months), and T3 measures Sustainability (12 months). ‘Child’ refers specifically to children who meet inclusion criteria and participate in the study. Additional adults in the household regardless of relationship to the eligible child will be invited to participate in laboratory visits and complete selected measures as indicated. Participants with known diabetes may not complete an OGTT.

Assessments

Glucose Tolerance will be assessed using a 75-gram OGTT with changes from baseline in 2-hour glucose concentrations between groups used as an efficacy endpoint. A fasting blood sample will be collected via venipuncture prior to administration of 75 grams of glucose in solution (Glucola). A second blood sample will be collected 120 minutes post-consumption. Fasting and 120-minute samples will be utilized for assessment of plasma glucose and serum insulin concentrations. Children whose glucose concentrations suggest they may have diabetes will be referred for confirmation and follow-up care. If this occurs at the T1 visit, they will be ineligible to enroll in the trial.

Generic and Weight-Specific Quality of Life (QoL) will be measured using validated instruments in children and parents/guardians with changes from baseline in QoL scores between groups as an efficacy endpoint. In children, general and Weight-Specific QoL will be assessed using the Youth Quality of Life (YQOL) short form and weight-specific instrument.32 The YQOL was developed through semi-structured interviews with youth regarding positive and negative aspects of QoL.32 Both measures assess QoL across three domains: self (feelings about self), social relationship (friends and family), and environment (social and cultural milieu). In adults, general QoL will be assessed using the World Health Organization Brief Quality of Life Instrument which was designed using similar theoretical principles to the YQOL.33 Weight-specific QoL in adults will be assessed by the Obesity and Weight-Loss Quality of Life (OWLQOL) instrument.34

Changes in total body composition (total and percent fat, total muscle mass, and bone) will be evaluated by Dual-energy X-Ray Absorptiometry (DEXA) using the G.E. Lunar iDXA (G.E. Lunar, Madison, WI).35,36

Changes in physical activity (vigorous, moderate, and light) will be measured by wrist-worn accelerometers over a 7-day period. The accelerometer will capture minutes/day of light, moderate-to-vigorous and vigorous activity over 7 days with ≥4 days and ≥10 hours/day of recording determined as a valid asessment.37–39

Changes in eating behaviors will be assessed using the NCI Dietary Screener Questionnaire to estimate the frequency of intake of select food groups (e.g., fruit & vegetables, fiber, added sugars).40 The NCI Dietary Screener Questionnaire has been validated in Latinos.41

Potential Mediators

Family Engagement will be measured by the percentage of total household members that participate in study activities, along with participant attendance and retention rates.

Family Empowerment will be assessed using the Physical Activity, Diet, and Weight-Related Resource Empowerment scale. This validated scale measures parents’ self-efficacy to leverage resources to promote healthy lifestyle behaviors in their children.42

Family Cohesion will be evaluated using the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Scale IV Short Form is a validated measure in Latinos, and provides reliable measurement of adaptability, cohesion and satisfaction with the levels of flexibility and cohesion within the family unit members of the family.43

Family Resilience will be measured using the Walsh Family Resilience Questionnaire. This scale measures family resiliency through three domains: belief systems, organization patterns, and communication (e.g. problem-solving).13 This instrument has been demonstrated to have good inter-item reliability and construct validity.44

Additional Measures

Family Structure and History of Diabetes will be determined by documenting the number and relationship to the child participant of any family member living in the household as well as all family members up to the grandparents on both sides who have diabetes.

Acculturation will be assessed using linear (e.g., primary language spoken, country of origin, time in the U.S.) and multidimensional measures using the Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II (ARSMA-II). The ARSMA-II is a reliable multidimensional acculturation measure in Latino youth45 and adults.46,47

Socioeconomic Status of families will be evaluated by the adults’ level of education, employment status, household income relative to size, health insurance status, and use of public assistance programs.

Pubertal Development in children will be measured by the Pubertal Developmental Scale.48 This scale is a self-reported measure of physical development which identifies five stages of development based on growth in height, body hair, skin changes, and sex-specific questions. It has good reliability, has been shown to be correlated to measurement of pubertal development from physical examination.48

Ethics

Prior to study procedures, the research team will obtain written informed consent and child assent. Participants will be informed that involvement in the study is voluntary and that they are free to withdraw at any time. They will also be told that declining to participate will not affect their health services and their confidentiality will be maintained. All study-related material will be available in English and Spanish, and bilingual/bicultural research staff will be available to answer questions and administer consent/assent.

The study protocol and all study-related documents have been approved by the Institutional Review Board at Arizona State University. The study is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05228522).

Intervention Fidelity

Intervention fidelity will be supported through (1) having all health educators complete the Lifestyle Coach Training by the Association of Diabetes Care and Education Specialists, (2) employing a detailed manual for intervention delivery, (3) trained researchers observing 25% of the classes using the manual, class objectives, and checklists, (4) monitoring family attendance, (5) documenting exercise adherence by heart rate and RPE targets during exercise, (6) and monitoring completion of SMART goals. Our team will use weekly reminder calls and texts to support attendance. Families who need assistance with transportation are provided a ride via a transportation company to and from the classes and laboratory appointments at no cost to the participants. Participants are compensated for attending data collection visits, responding to retention calls/texts, and participating in class activities during the intervention. All families (regardless of study arm assignment) are offered a 6-month membership to the YMCA after study completion.

Statistical Models and Methods of Analysis

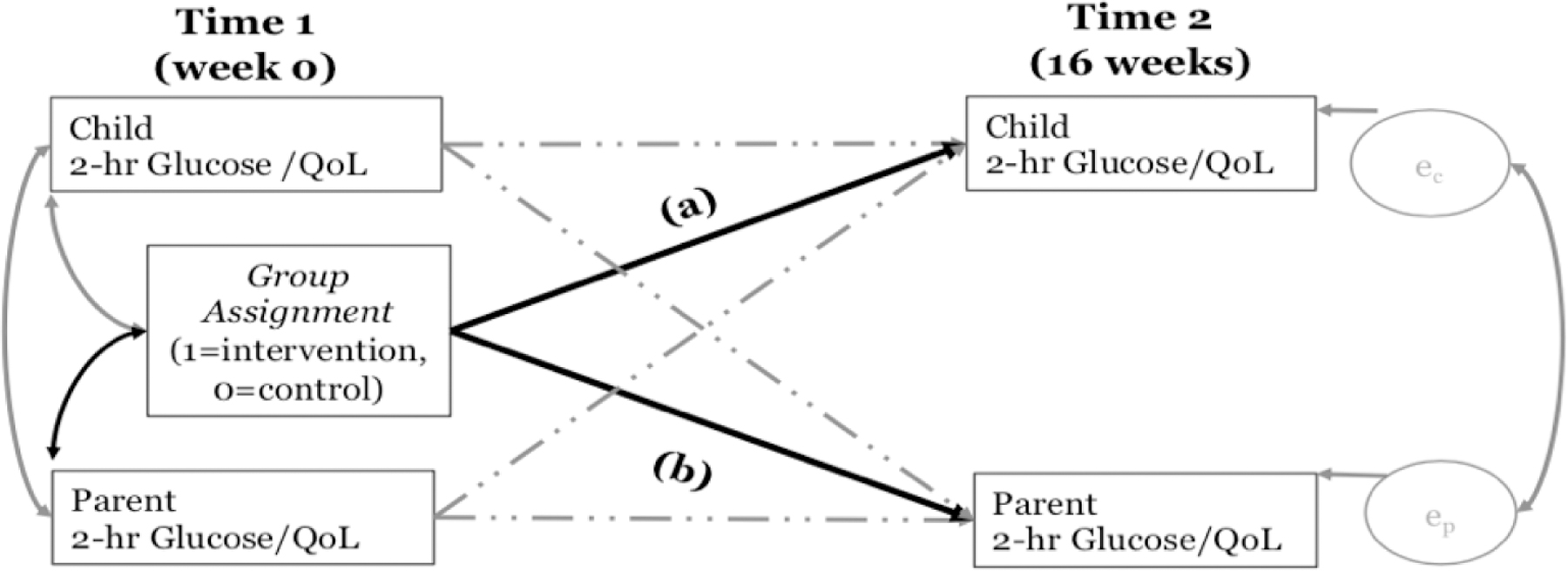

To test the efficacy of a family-focused diabetes prevention intervention for improving glucose tolerance and increasing QoL for both children and parents/guardians, we will use the actor−partner interdependence model (APIM)49 implemented within a structural equation modeling framework.50 Through auto-regressive cross-lagged paths, the APIM allows for a simultaneous examination of the efficacy in children and parents/guardians (See Figure 3). We will test the (a) direct effect of the intervention on child 2-hour glucose/QoL independent of the effect on change of parent 2-hour glucose/QoL and (b) the direct effect of the intervention on parent 2-hour glucose/QoL independent of the child’s effect. The APIM also accounts for the nonindependence of data between the parent and child within each dyad.51 In all models, both the child and adult primary and secondary outcomes will be simultaneously examined. The baseline and outcome variables will be correlated between parent and child to adjust for the nonindependence of the data.

Figure 3.

Note. ec to indicate efficacy in children; ep to indicate efficacy in parents/guardians. Path (a) captures the direct effect of the intervention on child 2-hour glucose/QoL independent of the effect on change of parent 2-hour glucose/QoL. Path (b) captures the direct effect of the intervention on parent 2-hour glucose/QoL independent of the child’s effect.

To explore the heterogeneity of intervention effects within and between families, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) will be calculated using repeated measure mixed models with condition by time effects.52 The ICC is a ratio of variances derived through partitioning the total variance within and between families. ICCs ≥0.75 indicate that individuals within a family are responding similarly (e.g., changes in 2-hour glucose/QoL are similar for parents/guardians and children from the same family), 0.4≤ICCs<0.75 indicate good to fair similarity in family response, and an ICC<0.4 indicates dissimilarity in family response.53

Sensitivity analyses will be conducted to assess if results are consistent with different actor/partner combinations.54 The sensitivity analyses will be conducted in only those families where more than one child or parent participated in data collection. The series of sensitivity analyses will test if the direction and magnitude of the results differ by: (1) replacing the parent in the main analyses with the other parent’s data; (2) replacing the child in the main analyses with another child’s data; and (3) replacing the dyad (parent-child) in the main analyses with data from the alternative dyad.55 To safeguard against biases in effect sizes, confidence intervals, and standard deviations, sensitivity analyses will only be conducted if there are >10 different actor/partner combinations per arm.56 Sensitivity analysis will be used to examine sex as a biological variable to test if the direction/magnitude of results differ based upon the sex of the child and/or parent. Sensitivity analyses will also include number of sessions attended to determine if there is an association between study outcomes and intervention dosage.

Analyses will be conducted within Mplus Version 8 using a maximum likelihood estimator that is robust to non-normality. Missingness will be evaluated to determine if it is related to randomization and any baseline or post- intervention variables. Analyses will retain all randomized participants (i.e., intent to treat). To adjust for missingness or attrition, we will use full information maximum likelihood estimation and will calculate bias-corrected bootstrapped standard errors and confidence intervals based on 1,000 draws.

Discussion

The Latino population is one of the fastest growing populations in the U.S.57 and experiences significant diabetes-related health disparities.58 Although the DPP lifestyle intervention was very effective in Latino adults,8 it has not yet been adapted for delivery to Latino families that include both youth and parents/guardians. To address the gap in the literature, our team developed a novel family diabetes prevention model in order to guide a culturally-grounded diabetes prevention program among high-risk Latino families.

Prioritizing the family unit and assessing family outcomes is a major innovation of this study. Previous diabetes prevention programs, such as the DPP,7 focus on individuals or parent-child dyads59 but considering the entire family as a system may amplify the efficacy and impact of such interventions. Interventions to improve children’s health and physical activity are most effective and sustainable when parents and families are involved in the intervention.60 Prevention efforts that prioritize the family as a reinforcing, supportive system have the potential for greater overall impact.

Another innovative aspect of this intervention is the inclusion of a robust psychosocial wellness component. The increased mental health burden among youth with obesity61 and the relationship between mental health and T2D risk in both adults62 and children63 suggests that diabetes prevention efforts can be strengthened by improving mental health. Therefore, the intervention curriculum provides families with skills training and techniques aimed at promoting mental health and wellbeing while considering the unique sociocultural dynamics of Latino families.

Community-engaged approaches can enhance the translation of research to practice and academic-community partnerships have been shown to lead to improved population health outcomes.64 Delivering the intervention in the context of the community through community agencies further enhances the translational potential of the research.65 To promote community-engaged research, our research team has maintained strategic partnerships with community organizations that serve the Latino population for over a decade, providing a unique position to serve the priority community. The curriculum was developed by our community partners and they have collaboratively adapted the intervention curriculum alongside the research team and refined it over time using the guiding principle that it be delivered in the community, by the community, and for the community.22–25 Participants are recruited through community-facing organizations and the intervention is delivered at a local YMCA. This creates an accessible platform for participants and provides a context for maintaining a healthy lifestyle after completing the research study. Further, partnering with established community organizations through programs that align with their mission leverages existing resources that can exist independent of external funding. For example, the YMCA Healthier Communities Initiative facilitates efforts that focus on making policy and environmental changes that support a healthy lifestyle in communities across the United States.66 Similarly, our partners at the Ivy Center for Family Wellness within the St. Vincent de Paul Medical and Dental Clinic provide medical and dental services as a safety net for low-income and uninsured and underserved adults and children in the local community.

Conclusion

There is a critical need for scalable T2D prevention interventions for underserved communities where diabetes is most prevalent. Focusing on diabetes prevention for families may be more efficacious and sustainable than individual-based interventions as social support and family cohesion can amplify the impact by engaging the family as a health-oriented system. The results of this study may have far reaching implications for health promotion and diabetes prevention research and practice.

Figure 2.

Study Design.

Note. Numbers refer to families, not individual persons.

Acknowledgments:

We would like to sincerely thank our community partners at St. Vincent de Paul Medical and Dental Clinic, the YMCA, and Phoenix Children’s Hospital for their collaboration in this work. This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIDDK (to Dr. Knowler).

Funding:

This study is funded through the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) through R01DK107579-07. Monica Diaz received support through an NIDDK Diversity Supplement (3R01DK107579-07S1). William C. Knowler is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIDDK. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CRediT Author Statement

https://www.elsevier.com/authors/policies-and-guidelines/credit-author-statement Morgan E. Braxton: Writing- Original Draft, Writing- Review & Editing, Visualization Eucharia Nwabichie: Writing- Original Draft, Writing- Review & Editing Monica Diaz: Methodology, Resources, Writing- Review & Editing Elvia Lish: Methodology, Resources, Writing- Review & Editing Stephanie L. Ayers: Methodology, Data Curation, Writing- Review & Editing Allison N. Williams: Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing- Review & Editing Mayra Tornel: Investigation, Data Curation, Writing- Review & Editing Paul McKim: Methodology, Resources, Writing- Review & Editing Jared Treichel: Methodology, Resources, Writing- Review & Editing William C. Knowler: Supervision, Writing- Review & Editing Micah L. Olson: Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing- Review & Editing Gabriel Q. Shaibi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing- Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition

Declaration of interests

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests. Dr Shaibi reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Phoenix Children’s Hospital (PCH) for research consultation, which has been disclosed to Arizona State University, outside the submitted work. PCH participated in the research resulting in this publication.

References

- 1.Lawrence JM, Divers J, Isom S, et al. Trends in Prevalence of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes in Children and Adolescents in the US, 2001–2017. JAMA 2021;326(8):717–727. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.11165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryan S, Afful J, Carroll M, et al. NHSR 158. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–March 2020 Pre-Pandemic Data Files National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.); 2021. doi: 10.15620/cdc:106273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Menke A, Casagrande S, Cowie CC. Prevalence of Diabetes in Adolescents Aged 12 to 19 Years in the United States, 2005–2014. JAMA 2016;316(3):344–345. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng YJ, Kanaya AM, Araneta MRG, et al. Prevalence of Diabetes by Race and Ethnicity in the United States, 2011–2016. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 2019;322(24):2389–2398. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.19365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Arizona; United States. Accessed July 12, 2022. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/AZ,US/PST045221 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murea M, Ma L, Freedman BI. Genetic and environmental factors associated with type 2 diabetes and diabetic vascular complications. Rev Diabet Stud 2012;9(1):6–22. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2012.9.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DPP Research Group. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): Description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care 2002;25(12):2165–2171. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.12.2165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tabak RG, Sinclair KA, Baumann AA, et al. A review of diabetes prevention program translations: use of cultural adaptation and implementation research. Transl Behav Med 2015;5(4):401–414. doi: 10.1007/s13142-015-0341-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corona K, Campos B, Chen C. Familism Is Associated With Psychological Well-Being and Physical Health: Main Effects and Stress-Buffering Effects. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 2017;39(1):46–65. doi: 10.1177/0739986316671297 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bamberger KT, Coatsworth JD, Fosco GM, Ram N. Change in Participant Engagement During a Family-Based Preventive Intervention: Ups and Downs with Time and Tension. J Fam Psychol 2014;28(6):811–820. doi: 10.1037/fam0000036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dietz WH, Solomon LS, Pronk N, et al. An Integrated Framework For The Prevention And Treatment Of Obesity And Its Related Chronic Diseases. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(9):1456–1463. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh F Strengthening Family Resilience Third Edition. The Guilford Press; 2016. Accessed July 28, 2022. https://web-p-ebscohost-com.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/ehost/ebookviewer/ebook?sid=c08da538-2723-4db2-b282-523af1736fec%40redis&vid=0&format=EB [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kulis SS, Ayers SL, Harthun ML, Jager J. Parenting in 2 Worlds: Effects of a Culturally Adapted Intervention for Urban American Indians on Parenting Skills and Family Functioning. Prev Sci 2016;17(6):721–731. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0657-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lauricella M, Valdez JK, Okamoto SK, Helm S, Zaremba C. Culturally Grounded Prevention for Minority Youth Populations: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Prim Prev 2016;37(1):11–32. doi: 10.1007/s10935-015-0414-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun Y, You W, Almeida F, Estabrooks P, Davy B. The Effectiveness and Cost of Lifestyle Interventions Including Nutrition Education for Diabetes Prevention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Acad Nutr Diet 2017;117(3):404–421.e36. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2016.11.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meinert CL. Clinical Trials : Design, Conduct, and Analysis; 1986.

- 18.CDC. BMI Calculator for Child and Teen Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published February 9, 2023. Accessed March 24, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/bmi/calculator.html [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Diabetes Association. 13. Children and Adolescents: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes−2020. Diabetes Care 2019;43(Supplement_1):S163–S182. doi: 10.2337/dc20-S013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2020. Diabetes care 2020;43(Suppl 1):S14–S31. doi: 10.2337/dc20-S002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vander Wyst KB, Olson ML, Hooker E, et al. Yields and costs of recruitment methods with participant phenotypic characteristics for a diabetes prevention research study in an underrepresented pediatric population. Trials 2020;21(1):716. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04658-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Armando Peña, Olson Micah L., Hooker Elva, et al. Effects of a Diabetes Prevention Program on Type 2 Diabetes Risk Factors and Quality of Life Among Latino Youths With Prediabetes A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Network Open, Pediatrics Published online 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Shaibi GQ, Greenwood-Ericksen MB, Chapman CR, Konopken Y, Ertl J. Development, Implementation, and Effects of Community-Based Diabetes Prevention Program for Obese Latino Youth. Journal of primary care & community health 2010;1(3):206–212. doi: 10.1177/2150131910377909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soltero EG, Konopken YP, Olson ML, et al. Preventing diabetes in obese Latino youth with prediabetes: a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC public health 2017;17(1):261–261. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4174-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soltero EG, Ramos C, Williams AN, et al. Viva Maryvale!: A Multilevel, Multisector Model to Community-Based Diabetes Prevention. American journal of preventive medicine 2019;56(1):58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.07.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bandura A Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual review of psychology 2001;52(1):1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baker MK, Simpson K, Lloyd B, Bauman AE, Singh MAF. Behavioral strategies in diabetes prevention programs: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes research and clinical practice 2010;91(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.06.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castro FG, Barrera M, Martinez CR. The cultural adaptation of prevention interventions: resolving tensions between fidelity and fit. Prev Sci 2004;5(1):41–45. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000013980.12412.cd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nguyen-Vaselaar H, Lappe JM. Goal-Setting Behavior for Physical Activity in Adults With Diabetes: A Pilot Project. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners 2021;17(10):1281–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2021.08.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weintraub J, Cassell D, DePatie TP. Nudging flow through ‘SMART’ goal setting to decrease stress, increase engagement, and increase performance at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 2021;94(2):230–258. doi: 10.1111/joop.12347 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Headid RJ III, Park SY. The impacts of exercise on pediatric obesity. Clin Exp Pediatr 2020;64(5):196–207. doi: 10.3345/cep.2020.00997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patrick DL, Edwards TC, Topolski TD. Adolescent quality of life, part II: initial validation of a new instrument. J Adolesc 2002;25(3):287–300. doi: 10.1006/jado.2002.0471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O’Connell KA. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF Quality of Life Assessment: Psychometric Properties and Results of the International Field Trial A Report from the WHOQOL Group. Quality of life research 2004;13(2):299–310. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018486.91360.00 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patrick DL, Bushnell DM, Rothman M. Performance of Two Self-Report Measures for Evaluating Obesity and Weight Loss. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 2004;12(1):48–57. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Helba M, Binkovitz LA. Pediatric body composition analysis with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Pediatric radiology 2009;39(7):647–656. doi: 10.1007/s00247-009-1247-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wells J, Haroun D, Williams JE, et al. Evaluation of DXA against the four-component model of body composition in obese children and adolescents aged 5–21 years. International Journal of Obesity 2010;34(4):649–655. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cain KL, Sallis JF, Conway TL, Van Dyck D, Calhoon L. Using Accelerometers in Youth Physical Activity Studies: A Review of Methods. Journal of Physical Activity & Health 2013;10(3):437–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trost SG, Pate RR, Freedson PS, Sallis JF, Taylor WC. Using objective physical activity measures with youth: How many days of monitoring are needed? Medicine and science in sports and exercise 2000;32(2):426–431. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200002000-00025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ward DS, Evenson KR, Vaughn A, Rodgers AB, Troiano RP. Accelerometer Use in Physical Activity: Best Practices and Research Recommendations. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 2005;37(11 Suppl):S582–S588. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000185292.71933.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yaroch AL, Tooze J, Thompson FE, et al. Evaluation of three short dietary instruments to assess fruit and vegetable intake: The National Cancer Institute’s Food Attitudes and Behaviors (FAB) Survey. J Acad Nutr Diet 2012;112(10):1570–1577. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Colón-Ramos U, Thompson FE, Yaroch AL, et al. Differences in fruit and vegetable intake among Hispanic subgroups in California: results from the 2005 California Health Interview Survey. J Am Diet Assoc 2009;109(11):1878–1885. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jurkowski JM, Lawson HA, Green Mills LL, Wilner PG, Davison KK. The Empowerment of Low-Income Parents Engaged in a Childhood Obesity Intervention. Family & community health 2014;37(2):104–118. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Priest JB, Parker EO, Hiefner A, Woods SB, Roberson PNE. The Development and Validation of the FACES‐IV‐SF. Journal of marital and family therapy 2020;46(4):674–686. doi: 10.1111/jmft.12423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duncan JM, Garrison ME, Killian TS. Measuring Family Resilience: Evaluating the Walsh Family Resilience Questionnaire. The Family Journal 2021;29(1):80–85. doi: 10.1177/1066480720956641 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bauman S The Reliability and Validity of the Brief Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II for Children and Adolescents. Hispanic journal of behavioral sciences 2005;27(4):426–441. doi: 10.1177/0739986305281423 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cuellar I, Arnold B, Maldonado R. Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II: A Revision of the Original ARSMA Scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 1995;17(3):275–304. doi: 10.1177/07399863950173001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jimenez DE, Gray HL, Cucciare M, Kumbhani S, Gallagher-Thompson D. Using the Revised Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans (ARSMA-II) with Older Adults. Hisp Health Care Int 2010;8(1):14–22. doi: 10.1891/1540-4153.8.1.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petersen AC, Crockett L, Richards M, Boxer A. A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. J Youth Adolesc 1988;17(2):117–133. doi: 10.1007/BF01537962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kenny D, Kashy D, Cook W, Evans D. Dyadic Data Analysis Vol 64.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gistelinck F, Loeys T. The Actor–Partner Interdependence Model for Longitudinal Dyadic Data: An Implementation in the SEM Framework. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 2019;26(3):329–347. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2018.1527223 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stas L, Kenny DA, Mayer A, Loeys T. Giving dyadic data analysis away: A user-friendly app for actor-partner interdependence models. Personal Relationships 2018;25:103–119. doi: 10.1111/pere.12230 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bell ML, Rabe BA. The mixed model for repeated measures for cluster randomized trials: a simulation study investigating bias and type I error with missing continuous data. Trials 2020;21(1):148. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-4114-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosner B Fundamentals of Biostatistics; 2000.

- 54.Thabane L, Mbuagbaw L, Zhang S, et al. A tutorial on sensitivity analyses in clinical trials: the what, why, when and how. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2013;13(1):92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Velentgas P, Dreyer NA, Nourjah P, Smith SR, Torchia MM. Developing a Protocol for Observational Comparative Effectiveness Research: A User’s Guide Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013. Accessed February 16, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK126190/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bell ML, Whitehead AL, Julious SA. Guidance for using pilot studies to inform the design of intervention trials with continuous outcomes. Clin Epidemiol 2018;10:153–157. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S146397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.U.S. Census Bureau. U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Arizona; United States. Published 2021. Accessed January 26, 2023. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/AZ,US# [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vidal TM, Williams CA, Ramoutar UD, Haffizulla F. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Latinx Populations in the United States: A Culturally Relevant Literature Review. Cureus 2022;14(3):e23173. doi: 10.7759/cureus.23173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Janicke DM, Lim CS, Perri MG, et al. The Extension Family Lifestyle Intervention Project (E-FLIP for Kids): design and methods. Contemp Clin Trials 2011;32(1):50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brown HE, Atkin AJ, Panter J, Wong G, Chinapaw MJM, van Sluijs EMF. Family-based interventions to increase physical activity in children: a systematic review, meta-analysis and realist synthesis. Obesity Reviews 2016;17(4):345–360. doi: 10.1111/obr.12362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kanellopoulou A, Antonogeorgos G, Douros K, Panagiotakos DB. The Association between Obesity and Depression among Children and the Role of Family: A Systematic Review. Children (Basel) 2022;9(8):1244. doi: 10.3390/children9081244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Alzoubi A, Abunaser R, Khassawneh A, Alfaqih M, Khasawneh A, Abdo N. The Bidirectional Relationship between Diabetes and Depression: A Literature Review. Korean J Fam Med 2018;39(3):137–146. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.2018.39.3.137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shomaker LB, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Stern EA, et al. Longitudinal Study of Depressive Symptoms and Progression of Insulin Resistance in Youth at Risk for Adult Obesity. Diabetes Care 2011;34(11):2458–2463. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Irby MB, Moore KR, Mann-Jackson L, et al. Community-Engaged Research: Common Themes and Needs Identified by Investigators and Research Teams at an Emerging Academic Learning Health System. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18(8):3893. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18083893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Viswanathan M, Kraschnewski JL, Nishikawa B, et al. Outcomes and costs of community health worker interventions: a systematic review. Med Care 2010;48(9):792–808. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e35b51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.YMCA. Healthier Communities Initiatives Published 2023. Accessed February 9, 2023. https://www.ymca.org/what-we-do/healthy-living/communities